48 results

From John Spence's Postdoc Time in Oxford to my Research on GaN and Graphene

-

- Journal:

- Microscopy and Microanalysis / Volume 28 / Issue S1 / August 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 July 2022, pp. 2736-2737

- Print publication:

- August 2022

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Interpersonal violence and mental health outcomes following disaster

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Open / Volume 6 / Issue 1 / January 2020

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 December 2019, e1

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Atomic Resolution Imaging of Dislocations in AlGaN and the Efficiency of UV LEDs

-

- Journal:

- Microscopy and Microanalysis / Volume 24 / Issue S1 / August 2018

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 August 2018, pp. 4-5

- Print publication:

- August 2018

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

How Cutting-Edge Atomic Resolution Microscopy Can Help to Solve Some of the World's Energy Problems

-

- Journal:

- Microscopy and Microanalysis / Volume 20 / Issue S3 / August 2014

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 August 2014, pp. xcvii-c

- Print publication:

- August 2014

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

How Cutting-Edge Atomic Resolution Microscopy Can Help to Solve Some of the World’s Energy Problems

-

- Journal:

- Microscopy and Microanalysis / Volume 20 / Issue S2 / August 2014

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 29 July 2014, pp. 11-14

- Print publication:

- August 2014

-

- Article

- Export citation

Coincident Electron Channeling and Cathodoluminescence Studies of Threading Dislocations in GaN

-

- Journal:

- Microscopy and Microanalysis / Volume 20 / Issue 1 / February 2014

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 November 2013, pp. 55-60

- Print publication:

- February 2014

-

- Article

- Export citation

35 - Lighting

- from Part 5 - Energy efficiency

-

-

- Book:

- Fundamentals of Materials for Energy and Environmental Sustainability

- Published online:

- 05 June 2012

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2011, pp 474-490

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

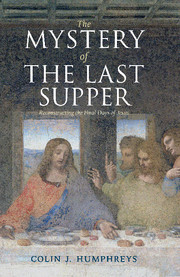

13 - A new reconstruction of the final days of Jesus

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 191-196

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Four mysteries of the last week of Jesus

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 1-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp v-v

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus

-

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011

7 - Did Jesus use the solar calendar of Qumran for his last supper Passover?

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 95-109

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Discovering the lost calendar of ancient Israel

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 121-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - The date of the last supper: the hidden clues in the gospels

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 151-168

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Dating the crucifixion – the first clues

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 14-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Does ancient Egypt hold a key to unlocking the problem of the last supper?

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 110-120

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 227-233

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - From the last supper to the crucifixion: a new analysis of the gospel accounts

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 169-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The moon will be turned to blood

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp 80-94

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- The Mystery of the Last Supper

- Published online:

- 03 May 2011

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2011, pp xii-xiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation