37 results

A history of high-power laser research and development in the United Kingdom

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- High Power Laser Science and Engineering / Volume 9 / 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 April 2021, e18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Newman’s Irish University

- from Part II - Ireland and the Liberal Arts and Sciences

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition, 1830–1880

- Published online:

- 29 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 92-107

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Australia

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 281-402

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 1-21

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Canada

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 204-280

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 483-515

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - New Zealand

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 403-466

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The United States

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 22-76

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - South Africa

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 151-203

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 516-566

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - India

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 113-150

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 467-482

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp xiv-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Newfoundland

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp 77-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgements

-

- Book:

- Ireland's Empire

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020, pp viii-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

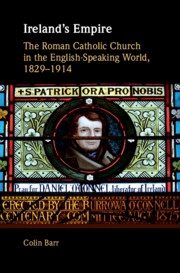

Ireland's Empire

- The Roman Catholic Church in the English-Speaking World, 1829–1914

-

- Published online:

- 20 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 16 January 2020

11 - The Re-energising of Catholicism, 1790–1880

- from Part III - Religion

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Ireland

- Published online:

- 20 April 2018

- Print publication:

- 26 April 2018, pp 280-304

-

- Chapter

- Export citation