Introduction

In 1960, mentally disturbed people over about sixty years of age were widely assumed to have irreversible senility. Little attention was paid to Martin Roth’s research which showed conclusively that mentally unwell older people were not all senile but suffered from a range of disorders. In the nomenclature of the time, those were affective psychosis, late paraphrenia, acute confusion and arteriosclerotic and senile dementia.1 Only two hospitals in the UK routinely offered older people thorough psychiatric assessment and treatment. One was a ward at the Bethlem Royal Hospital led by Felix Post, primarily for people suffering from ‘functional’ illnesses, mainly depression, schizophrenia and other psychoses. The other was a comprehensive old age psychiatry service, including day hospital, outpatient and domiciliary services, plus assessment, infirmary and long-stay wards, which Sam (Ronald) Robinson established at Crichton Royal Hospital, Dumfries.

This chapter aims to explain how Roth’s, Post’s and Robinson’s ideas gradually influenced clinical practice and service provision across the UK, shifting from typical custodial inactivity and neglect of patients assumed to be irreversibly senile to the creation of proactive ‘psychiatry of old age’ (POA) services. The chapter comprises two sections: 1960–1989 and 1989–2010. The first focuses on the development of the specialty until it was formally recognised by the Department of Health in 1989. It was the subject of my PhD thesis.2 Regarding the second section, I started as a senior house officer in POA in 1989. For this section, I have also drawn extensively on the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCPsych) Old Age Faculty commemorative newsletter ‘21 years of old age psychiatry’ published in 2011.3 Although the essence of much National Health Service (NHS) policy is UK-wide, specific details and implementation plans may relate to one or more of the constituent countries. Given the brevity of this chapter, I have focused mainly on developments in England.

1960–1989

Liberal ideas about personal autonomy, choice and independence emerged internationally in the 1960s. New legislation in the UK on suicide, race relations, homosexuality and abortion reflected this. Changing agendas permitted younger people to make choices, even if risky, but older people were perceived as inevitably vulnerable and, despite their experience of life, their wishes were frequently ignored. According to Pat Thane, retirement was a mid-twentieth-century change which ‘increasingly defined old people as a distinct social group defined by marginalisation and dependency’.4 Alongside negative public perceptions, retirement was associated with a marked fall in personal income and reliance on the state pension.5 With poverty came disadvantageous health inequalities.6

In the early 1960s, more than a third of psychiatric hospital beds were occupied by people aged over sixty-five. The social scientist Peter Townsend identified many older people in long-stay accommodation who ‘possess capacities and skills which are held in check or even stultified. Staff sometimes do not recognise their patients’ abilities, though more commonly they do not have time to cater for them.’7 The sheer size of wards with up to seventy beds made providing satisfactory standards of nursing care almost impossible. These wards compared unfavourably with hotbeds of activity on those for younger people which used state-of-the-art medications, psychosocial, rehabilitative and therapeutic community approaches, and planned for discharge. After the Mental Health Act 1959 (MHA), with steps taken to begin to close the psychiatric hospitals and develop alternative services in the community and in district general hospitals (DGHs), younger people were discharged leaving older people behind.

For older people, clinically and scientifically, things edged on, albeit slowly. In 1961, Russell Barton and Tony Whitehead at Severalls Hospital, Essex, established a service based on Robinson’s at Crichton Royal. In 1962, Nick Corsellis demonstrated that senile dementia had the same pathology as Alzheimer’s disease: senility was therefore not just a worn-out ageing brain but a disease process requiring further research, aiming for prevention and cure. The same year, Post published an optimistic follow-up study of 100 older patients treated for depression.8 In 1965, his textbook of old age psychiatry,9 the first of its kind, was published, and the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) hosted an international symposium in London, Psychiatric Disorders in the Aged.10 These developments provide insights into clinical, epidemiological and neuroscience achievements at the time and indicate mounting interest in older people’s mental well-being. Neuropathology was discussed in terms of air encephalograms, post-mortems and electron microscopy. There were no validated brief cognitive assessment tools, and antidepressants consisted of tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy. The WPA event included remarkable and charismatic leaders such as Post, Roth and Robinson, Tom Lambo (a Nigerian psychiatrist) and V. A. Kral of ‘mild cognitive impairment’ fame (who had survived incarceration in Theresienstadt Nazi concentration camp). Among the delegates were junior doctors Tom Arie, Klaus Bergmann, Garry Blessed and Raymond Levy, all inspired by the people they met and by the academic content.

Reports of scandalously low standards of care on long-stay wards in geriatric and psychiatric institutions reached the headlines in 1967 when Barbara Robb published Sans Everything: A Case to Answer (see also Chapter 7).11 Arie, dual trained in social medicine and psychiatry, and shocked by the Sans Everything revelations, applied for a consultant psychiatrist post to work with older people at Goodmayes Hospital, Essex (‘an unposh place … Most people thought I had taken leave of my senses!’).12 Arie’s team had a low hierarchical structure and high morale, able staff were eager to join it and patients began to get better.13 Arie wrote in 1971: ‘I have never before been in a professional setting where intellectual and emotional satisfaction go more closely hand in hand.’14

Arie and a few other newly appointed POA consultants, including Bergmann, Blessed, Whitehead and Brice Pitt – a ‘happy band of pilgrims’ as Pitt called them – began to meet as a ‘coffee house’ group. The group was in the right place at the right time: in the wake of Sans Everything, the government was taking more interest in the mental well-being of older people. Through Arie’s social medicine links, including being personally acquainted with the chief medical officer, the group ‘heavily influenced’ a Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) blueprint, Services for Mental Illness Related to Old Age (1972).15 For the growing number of old age psychiatrists, this declaration of intentions became a bargaining tool to use with the DHSS or local NHS authorities when they failed to respond to identified needs.

Since, in most hospitals, younger people were discharged and older people were not, by 1973 almost 50 per cent of psychiatric hospital patients were over sixty-five,16 far in excess of the 14 per cent in the general population. Almost two decades after Roth’s research, undiagnosed but potentially treatable conditions contributed to this, particularly depression. This was also a personal tragedy, as Whitehead explained in the Guardian:

Old people may spend their last years in dreadful misery because severe depression has been wrongly diagnosed as senile decay … If you are anxious and depressed, and more and more people start treating you as if you were a difficult child, and you are finally incarcerated in a ward full of other elderly people who are being treated in the same way, it is likely that in time you will give up and take on the role of not just a child, but a baby.17

Two events in 1973 were central to the development of POA services: the coffee house group became the RCPsych Group for the Psychiatry of Old Age (GPOA; which in 1978 became the Section for the Psychiatry of Old Age (SPOA); later the Faculty) and the international economy took a turn for the worse with the oil crisis, the stock market crash and curbs on public sector expenditure. Promises of new services for an undervalued sector of the community were particularly vulnerable to political and economic fluctuations. Reduced public spending generated competition for resources rather than collaboration. For older mentally ill people, this was further complicated by ambiguities about who should take responsibility for their care – geriatricians, general psychiatrists or old age psychiatrists. Responsibility for the care of patients with long-standing severe mental illness who had grown old in hospital was a bone of contention between old age and general psychiatrists who were ‘dead keen to get us to take their old schizophrenics’, recollected Pitt many years later. Both general psychiatrists and geriatricians were happy when old age psychiatrists took mentally disturbed older patients off their hands. Categories of ‘dementia horizontalis’ and ‘dementia verticalis’ (i.e. more mobile, restless and often disturbing to other patients, requiring much POA nursing expertise) were one way of determining who should manage which patients, but the British Geriatrics Society and RCPsych jointly created more robust guidelines for collaborative working.18

Despite liaising closely with the DHSS, POA was not officially recognised as a NHS specialty. As a result, relevant age-based mental health data were not collected because ‘sub-specialty’ statistics were ‘ignored … coded under the appropriate main specialty’.19 This resulted in excluding POA from plans, such as for training psychiatrists and appointing staff. In 1978, for example, the DHSS recommended five consultants in ‘adult’ psychiatry and one in child psychiatry for a district of 200,000 people, with no mention of POA.20 Building projects for DGH psychiatric units also overlooked older people’s needs and innovative architectural designs to promote their independence.21 Sometimes, the DHSS admitted to only including older people when it feared that not doing so would leave them ‘wide open to severe criticism’.22 A different sort of data predicament arose when statistics derived from death certificates were used as a proxy for morbidity and health needs and underpinned NHS resource distribution; ‘dementia’ was generally subsumed under ‘old age’ making it invisible.

The government’s discussion paper A Happier Old Age (1978) acknowledged that services were ‘often less than satisfactory, making effective treatment or care difficult’ and that older people should be more involved in decision-making related to their health and social care.23 The Royal Commission on the NHS (1979) recommended additional resources for older people, but these were couched negatively in terms of ‘the immense burden these demands would impose’, a reiterated defeatist sentiment likely to discourage provision. In 1979, the new Conservative government was committed to controlling inflation, reviving the economy and holding back on public spending;24 and two years later, the DHSS’s Care in the Community was subtitled A Consultative Document on Moving Resources for Care, its real objective. The emphasis was on the role of the community, self-help and families to ‘look after their own’. This was unrealistic. The challenges for carers of people with dementia were well known,25 central to the origins of the Alzheimer’s (Disease) Society (founded 1979) and reflected in the title of the book The 36-Hour Day.26

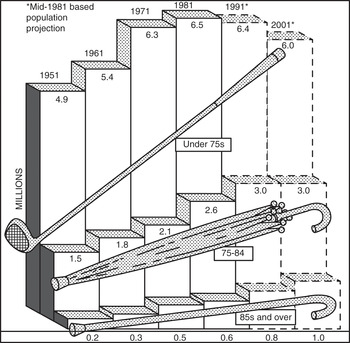

Establishing POA services was entwined with policy, politics, public opinion and stereotypes (Figure 22.1), and its leaders had to fight for every penny. Economic analyses of NHS provision tended to blame the difficulties on more older people living longer, ignoring other factors, such as rising costs of staff salaries, drugs, health technology and the cost of high dependency and palliative care at any age. They ignored increasing longevity which allowed older people to be active for more years, often contributing to the economy despite not being formally employed. The government, however, attributed rising costs of health care to remediable inefficiency within the NHS,27 which required administrative reorganisation.28 Sir Roy Griffiths, managing director of Sainsbury’s supermarkets, led a NHS management inquiry and introduced solutions from the commercial sector, particularly ‘general management’ with professional managers responsible for planning, implementation and control of performance (see also Chapter 12).29 This was particularly abhorrent to POA which had evolved almost entirely through clinical leadership. The restructuring, like NHS reforms before and since, offered rhetoric about providing for older people rather than the means to do so.

Figure 22.1 Official ageist stereotyping: ‘numbers of the elderly by broad age groups’, 1951–2001.

Amid the gloom, the ever enthusiastic and determined POA leadership found beacons of light. In neuroscience, the acetylcholine hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease emerged and the Alzheimer’s Society helped push dementia higher in public awareness and onto national policy and research agendas. Clinical POA became more multidisciplinary, adding strength to services and to previously medically led arguments on the need for them.30 The British Psychological Society established their old age special interest group in 1980. Geriatricians established the first memory clinic in 1983 at University College Hospital, London.31 Old age psychiatry was putting down academic roots, with four professors by 1986: Arie in Nottingham and Levy, Pitt and Elaine Murphy in London. Murphy became editor of the first dedicated POA academic journal, the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, from 1986. Some hospitals established joint geriatric-psychiatric units, based on the model Arie devised and used in his professorial unit. However, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) recommended that geriatric medicine should integrate more closely with general medicine, partly because of recruitment difficulties, and this took precedence over a holistic approach to older people’s health care.32 In 1987, older people’s mental disorders were still not routinely included in nurse training, neither were they discussed in the Royal College of General Practitioners’ Preventive Care of the Elderly. Older people were also excluded from much medical research, hazardous in the context of them being likely beneficiaries of that research.33

Each step forward had to be fought for. With the DHSS reluctant to create old age services, and with responsibility delegated to professional managers, undervalued specialties were easy to neglect. Inadequate data, ambiguities over responsibility for health care in old age, the DHSS and the main body of psychiatrists prioritising younger people before older, as well as the tendency for the NHS to prioritise physical over mental illness, ensured, intentionally or otherwise, that psychogeriatric services lagged behind. Nevertheless, the specialty grew, from a handful of old age psychiatrists in 1970, to 120 in 1980 and 280 in 1989. Old age psychiatrist Professor John Wattis, by his spurious use of statistics, commented humorously: ‘You could draw a graph which showed that the number of old age psychiatrists was increasing exponentially and by the year 2000 there would be no doctors who were not old age psychiatrists!’34 Inspiring teachers and a charismatic leadership – such as Arie, Wattis, David Jolley and Nori Graham – demonstrated POA’s truly holistic approach to health and social care and the rewarding nature of the work and drew keen recruits into it. The SPOA wanted their specialty to be recognised by the DHSS to ensure dedicated data collection, training schemes and allocation of resources but the DHSS argued against it. One reason was their fear of recruitment difficulties for an ‘unpopular’ specialty but that was incompatible with evidence of more POA consultants leading more services.

There was little movement within the RCPsych to support official recognition of POA. However, the RCP was disgruntled about older, mentally unwell people on medical wards. Sir Raymond Hoffenberg, its president, established a working party about POA services. The outcome: a recommendation by the RCP and RCPsych for specialty recognition to facilitate service developments, education, training and research. The DHSS could hardly ignore the joint recommendation.

1989–2010

In 1990, the NHS and Community Care Act enshrined the NHS purchaser/provider split and the role of social services in assessing need while delegating care to the expanding private sector (see also Chapter 10). Instead of unifying old age services, it fragmented them, especially tricky for older patients who required coordinated multidisciplinary, cross-agency care. Despite ongoing challenges, old age psychiatry services multiplied across the country but many organisational goals and individuals’ needs were still unmet. Greater provision was required.35 By 1995, more than 400 POA consultants in the UK worked mainly in comprehensive catchment area and domiciliary-based services, a tried, tested and successful model of care.

The model of service provision began to change after the first acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease, donepezil, was licensed in 1997. It was expensive, around £1,000 per patient per year. Dementia was prevalent, the population ageing, the potential demand excessive and the NHS required it to be rationed. In 2001, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)) ensured this happened by recommending that donepezil be ‘initiated’ by a specialist. This was widely interpreted to mean making the diagnosis and prescribing the medication in secondary care. Memory clinics multiplied. From being mostly research-based in a few university centres, they became local diagnostic and treatment services countrywide. More technology and ‘real medicine’ may have helped to reduce stigma and encourage public discussion. However, memory clinics also had drawbacks. These included transferring people with uncomplicated dementia into secondary care rather than developing skills in primary care as for other common disorders such as depression, diabetes and hypertension. They also diminished time available for expert staff to provide the mainstay of psychosocial interventions required by patients with the most complex and distressing dementias. More resources from a finite pot going into dementia services also detracted from providing services for older people with functional mental illnesses. This was worrying when dementia affected 5 per cent of people over sixty-five at any one time, while depression alone among the functional disorders affected more than 20 per cent.36

The pattern of officialdom allowing older people’s mental health service provision to lag behind that for younger adults persisted. The National Service Framework for Mental Health (1999) was for ‘working-age’ adults. Substantial extra funding accompanied it. The National Service Framework for Older People arrived eighteen months later. It was comprehensive, including functional disorders and dementia, but without the money attached to facilitate implementation. Observing improvements made in services for younger patients caused much frustration among old age psychiatrists.

The POA leadership had to advocate persistently for older people to receive appropriate levels and ranges of care equitable with those provided for younger adults. In 2005, the RCPsych Faculty of Old Age Psychiatry pointed out that ‘liaison psychiatry’ (psychiatric services for physically unwell patients in general hospitals) for working-age adults had ninety-three dedicated consultant posts in the British Isles but, for older people, consultant liaison input was additional to their general catchment area responsibilities.37 In 2006, a joint RCPsych and RCP report stated: ‘Ageist neglect of older people with mental illness must stop.’38 It did not stop and more inequity of provision followed, such as the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme (2008). IAPT was based on the premise that improved treatment of anxiety and depression for working-age adults would reduce their unemployment rates and thus pay for itself, or even generate notional surplus. IAPT excluded people over the age of sixty-five, even though they could benefit from the treatments offered. There was no acknowledgement that alleviating their mental symptoms could enable them to contribute more to society, such as in voluntary roles, and enhance independence, thus reducing the need for statutory support services, all of which could benefit the economy.

Other changes affected care for mentally unwell older people. The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 came into force in 2007. It provided a statutory framework to empower and protect vulnerable people who were unable to make their own decisions. Although idealistic and important for older people, implementing it, particularly the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards, brought new layers of bureaucracy at great financial expense, removing resources from direct care.

The financial crisis of 2008 preceded another much-needed and well-intentioned initiative, the National Dementia Strategy,39 and probably hampered its outcome. The Strategy aimed to help people ‘live well with dementia’, by encouraging early diagnosis; improving education and research; and attending to the needs of people with dementia and their carers in the community, care homes and general hospitals. It had money attached: £150 million over two years to support implementation. This was very welcome. However, in the context of direct costs of health and social care for dementia of around £8.2 billion annually, it was a drop in the ocean. Early problems with the Strategy included a baffling range of organisations – statutory, private, not-for-profit, health and social care – and a flurry of vaguely titled new job roles such as ‘advisors’, ‘navigators’ and ‘co-ordinators’, hardly straightforward for people with dementia and their carers to negotiate. The POA activists Professors Susan Benbow and Paul Kingston observed this and commented:

sexy new solutions implemented by managers can have the opposite effect to that intended. We need to stop our headlong rush into implementation and look at the evidence for these new roles, to consider what added value they bring, and how they can be governanced and supported. Only then will we do justice to the people and families living with a dementia.40

In the wake of the Strategy, NHS England appointed Professor Alistair Burns as National Clinical Director for Dementia. Potentially beneficial, this added to the worries of many in the field of POA: should dementia be syphoned off as a separate entity, and what about the rest of old age psychiatry? Depression and psychosis in old age, key concerns for POA, were barely talked about outside specialist circles. The Strategy’s protagonists had hoped that the issue of dementia would spearhead developments to benefit older people’s mental health, well-being and dignity more broadly. The sentiments were admirable but the outcomes complex, multifaceted and mainly after 2010, so outside the scope of this chapter.

The Equality Act 2010 proved to be a hindrance as well as a help for POA: it could not abolish deep-rooted societal ageist attitudes. These contributed to (mis)interpreting the Act in ways which affected service provision, such as by depriving older people with non-dementia mental illnesses of specialist facilities and treatment and placing them instead in ‘all-age’ or ‘ageless’ services. This failed to take into account their needs which differed from those of younger people, including frailty; multiple comorbidities; risks from drug side effects and polypharmacy; different presentations of the same disorders; and different psychosocial, cultural and financial contexts.

Conclusion

Major drivers of change included dictates of fashion, supposed economy and non-validated theoretical perspectives, often imposed from a top-down template. Policies and implementation patterns derived from managerial rather than POA clinical leadership demonstrated ageist perspectives. National directives advocating uniformity of service provision could be good, ensuring access to an agreed range of services at acceptable standards and avoiding a postcode lottery. However, uniformity ignored the need for variation to fulfil local needs and undermined innovative service delivery responses. It also destroyed morale, particularly when it led to the dismantling of trusted service components which fostered expertise and humane practice, such as joint geriatric-psychiatric units, services for ethnic minority populations and long-stay NHS units for people with the most difficult to manage mental disorders. Some dismantled services required painful reconstruction when policy changed.

By 2010, there was unease about the future of the specialty. Baroness Elaine Murphy commented that some social care services, essential in POA, were in ‘meltdown’,41 and Professor Robin Jacoby wrote an article on POA called ‘Of pioneers and progress, but prognosis guarded’.42 Ageism, despite the Equality Act, plus fiercer NHS business models of health care and seeking to maintain a corporate image, contributed to the difficulties. Despite the challenges, the rewards of making the lives of older people and their families more hopeful, dignified and fulfilling, by combining individual care and aiming to improve service delivery and linked to new frontiers of neuroscience research, exemplified the interactions between Mind, State and Society and continued to attract dedicated clinicians.

In 2018, a RCPsych report was entitled, Suffering in Silence: Age Inequality in Older People’s Mental Health Care.43 In 2020, NHS England’s website stated ambiguously that older people’s mental health ‘is embedded as a “silver thread” across all of the “adult” mental health Long Term Plan ambitions.’44 Both Suffering in Silence and the ‘silver thread’ blow an icy wind of ongoing ageism and under-resourcing, failing to allow older people to have the most humane treatment and failing to learn from history.

Key Summary Points

Liberal ideas about personal autonomy, choice and independence emerged internationally in the 1960s. Changing agendas permitted younger people to make choices, even if risky, but older people were perceived as inevitably vulnerable and, despite their experience of life, their wishes were frequently ignored.

For older people, clinically and scientifically, things edged on, albeit slowly.

Promises of new services for an undervalued sector of the community were particularly vulnerable to political and economic fluctuations.

The POA leadership had to advocate persistently for older people to receive appropriate levels and ranges of care equitable with those provided for younger adults.

Ongoing and ageist themes over the fifty years have included prioritising services for younger patients; the double whammy of stigma of mental illness plus old age; and policy decisions based on short-term economic calculations rather than likely health and well-being outcomes.