We are accustomed to thinking of residential property as an asset or an arrangement of legal rights. Yet, property forms are also behavioral, with the property interests and incentives of housing forms enabling or supporting behaviors and commitments. By choosing a residential property form, such as owning or renting, we commit ourselves to a range of opportunities, behaviors, and built-in, ongoing incentives for those behaviors. Homeownership is attractive in significant part for its behavioral and consumption benefits – contrary to the expectations of most homeowners, inflation-adjusted asset appreciation is startlingly modest (Shiller Reference Shiller2015, 27–30). The benefits of homeownership include greater control and governance rights, opportunities for “forced” or automatic savings through mortgages, incentives to maintain and improve property, and stronger rights to stay put.

Viewing property as behavioral, while overbroad, suggests a different starting place for understanding and innovating property forms: focusing on the behaviors we wish to enable and how to produce them. One application is to the rather cramped residential leasehold form, with its shallow possessory rights, weak incentives for property improvement, and limited opportunities for asset building. Can we provide an interested subset of renters a measure of the rights, behaviors, or benefits of homeownership? One way to accomplish this, albeit sometimes coarsely, is to adjust homeownership. A number of proposals in the scholarly literature have sought to create variants of the homeownership form, with the intent of producing some of the behaviors and benefits of homeownership while increasing affordability or adjusting risk (Fennell Reference Fennell2008, 1070–77; Arruñada and Lehavi Reference Arruñada and Lehavi2011, 26–33). There has been less progress in creating alternative housing forms that don’t require equity investment, putting them in reach of lower-income renters.

A behavioral perspective suggests one possibility for innovating rental: the use of incentives and commitment strategies to support alternative property forms and certain ownership-like behaviors and effects. Yet, applying these psychological tools to rental seems an uneasy fit with residential property law, which has tended to rely on equity interests and legal rules to produce ownership effects (e.g., Fischel Reference Fischel2001). Is incentivizing such behaviors inevitably too costly, complex, and vulnerable to unintended motivational effects to be successful?

This chapter examines renter equity, an emerging and understudied intermediate form of housing between homeownership and traditional rental (Cornerstone Renter Equity 2016; Renting Partnerships 2016). This fledging property form, in operation at four affordable housing sites in Cincinnati, Ohio, puts into practice the kind of psychology-informed policy design and finer-grained division of property rights that have been of so much recent theoretical interest (e.g., Fennell Reference Fennell2008, 179–85; Thaler and Sunstein Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008, 3–44). The renter equity form monetizes and allocates to tenants a share of the financial value created by their upkeep and participation in the property – and frames that allocation as an incentive in order to support a range of homeownership-like behaviors and benefits. Specifically, the lease provides renters the right to earn savings credits for a constellation of property-enhancing behaviors (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 16–20; Renting Partnerships 2016). In turn, the reduced property management and vacancy costs fund the renter savings accounts.

Renter equity has sparked increasing interest and attention from investors, think tanks, and government (HUD 2011; Williams Reference Williams2012, 1–2). Andrea Levere, president of the Corporation for Economic Enterprise, has proposed using HUD funding, including Sustainable Communities Initiative funding, the Community Development Block Grant, and HOME investment partnership funds, to expand the renter equity model on a national scale (Williams Reference Williams2012, 2). The Cornerstone Corporation, which manages three renter equity sites, recently trademarked the name “renter equity,” presumably with an eye toward licensing or franchising it to other providers of low-income affordable housing services. Renting Partnerships, a newer and similar housing form, envisions expanding to a network of affiliates (Margery Spinney, pers. comm.).

In academic circles, renter equity has been a much quieter innovation, with no scholarship to my knowledge addressing this housing form. In this chapter, I examine renter equity as an emerging innovation and a model of the potential, and the pitfalls, of leveraging incentives and commitments to support alternative housing forms. The chapter proceeds in five parts. Part 1 highlights some of the key behavioral options and benefits that renters lack and suggests that one consequence of landlord-tenant reform has been to reduce the incentives and commitment strategies available to tenants. Part 2 describes renter equity and a newer, similar form called renting partnerships. I use the term renter equity throughout this chapter to refer to the core property configuration shared by both renter equity and renting partnerships. Part 3 identifies the conceptual underpinnings of renter equity as well as legal and policy gaps in its implementation. In Part 4, I address behavioral and social concerns about renter equity incentives. Part 5 concludes by briefly discussing renter equity’s potential as an alternative property form and the lessons of renter equity for incentive-based “behavioral leasing.”

8.1 Confines of the Rental Form

Splitting possession from residual ownership (i.e., renting) confers a number of valuable benefits on renters, including greater residential mobility, allocating property management and repair obligations to landlords, and avoiding the financial risks of equity ownership. In other ways, however, this division is binary and often crude from the standpoints of tenant preferences, landlords’ interests, and social and community needs (Fennell Reference Fennell2008, 188–90). Renters, particularly long-term renters, miss out on a number of behavioral options and corresponding benefits allocated to their homeowning counterparts. This section highlights some of the behavioral confines of the rental form.

First, the division of property rights in rental reduces incentives for tenants to maintain and improve the rental property and local neighborhood. Beyond the benefits to consumption, the rental form does not monetize or compensate tenants for their investments in upkeep, safety, or improvements that increase residential value or enhance their local communities (cf. Lerman and McKernan Reference Lerman and McKernan2007, 1–2). Indeed, there are explicit disincentives for such tenant efforts: the risk of increased rent and gentrification (2). In some cases, landlords may compensate tenants implicitly for upkeep and improvements through lower rent. However, the standard lease offers no formal mechanism of compensation on which renters can rely. Concededly, renters have lower consumption motivations for such behaviors because they can exit more cheaply to satisfy consumption elsewhere and have limited control over rental duration (Rohe and Stewart Reference Rohe and Stewart1996, 45). However, renters still engage in some property-benefiting behaviors and presumably would engage in more if they could capture the value of their actions.

Not only do renters lack incentives to invest in property, they typically lack legal rights to do so. Standard residential leases make tenants liable for damages and subject to eviction for altering their units (e.g., appliances, flooring, even wall color) or making repairs without landlord consent. Renters also lack rights to participate in governance and decision making affecting common areas and residential management (cf. Davis Reference Davis2009, 29–31). For some, offloading upkeep and improvement to landlords is an attraction of renting (Freddie Mac 2016, 6, 16). Others, however, desire more intensive participation – perhaps particularly renters who anticipate less attentive landlords or who lack future prospects for ownership. Paucity of control can frustrate tenant preferences, and, some research suggests, produce negative psychological states (Manturuk Reference Manturuk2012, 409–22) and impair control over “image presentation” (Downs Reference Downs1981, 466). It is not surprising, or objectionable, that landlords have strong interests in protecting their property from value dissipation. Yet, some reallocations of consumption-oriented rights to tenants may be possible (e.g., limited tenant decision making subject to standards and a budget or tenant voting within owner-approved choice sets).

Landlord tenant reforms, while salutary in some regards, have narrowed opportunities for tenants to invest and participate in property by creating a harder-edged boundary between possessory rights in rental and ownership interests. In the 1970s, post-industrialization changes in housing needs and failures of rental market competition prompted the “reform era” of landlord-tenant law (Kelley Reference Kelley1995, 1563–74). These reforms shifted the treatment of leaseholds from a conveyance of property to a hybrid of contract and property (Glendon Reference Glendon1982, 503–05; Merrill and Smith Reference Merrill and Smith2001, 820–31). The shift toward contract law enabled courts to impose common law contract doctrines such as unconscionability and the implied warranty of habitability (obligation of the landlord to ensure fit and habitable rental premises), with some of these protections later codified (Korngold Reference Korngold1998, 707–07; cf. Super Reference Super2011, 389–400). These reforms also made many tenant protections non-waivable (Geurts Reference Geurts2004, 356–60).

One consequence of landlord-tenant reform has been to limit tenants’ ability to rent premises more cheaply, improve or maintain them, and realize the value of below-market rent for their lease term. Landlord-tenant laws regulating and limiting escrows (e.g., security deposits) also constrain the ability of tenants to contract with landlords for tenant alterations by escrowing additional money as security against damage. In the face of a complex framework of tenant protections, landlords are leery of contracting for tenants to provide maintenance or repair, make alterations, or assume greater governance or management roles. Even if landlords are willing to engage in such contracting, certain protections, such as the landlord warranty of habitability, cannot be waived in many states (Rabin Reference Rabin2011, 80). In some cases, tenant “sweat equity” arrangements may occur informally. For example, sociologist Matthew Desmond’s ethnography of urban renters describes instances where landlords allowed tenants to make up back rent and avoid eviction by working on the property (Desmond Reference Desmond2016, 129). Landlords who countenance such arrangements risk running afoul of landlord-tenant and labor laws.

A second constraint of the rental form is that renters lack ongoing, long-term rights to stay put. The legal duration of a typical residential lease is one year or month-to-month; after the lease term expires, the landlord can opt not to renew or to increase rent. Unlike homeowners who lock in ongoing possessory rights and a purchase price (and often a mortgage interest rate), tenants face rent increases and the accompanying risk of dislocation (Sinai and Souleles Reference Sinai and Souleles2005, 785–86). The lack of control over housing costs and mobility is a significant drawback to renting that can frustrate tenant preferences, increase psychological stress, and undermine financial security (Desmond Reference Desmond2016). Limited control over residential duration also weakens incentives for tenants to invest in local communities.

Third, tenants have less ability than homeowners to use housing as a commitment device to bind their future selves to certain actions or decisions. Commitment strategies address bounds on willpower and self-control by removing a future temptation or option entirely or raising the costs of exercising that option. The illiquidity of the owned home (i.e., the expense and difficulty of asset transfer) acts as a commitment strategy for longer residential duration and the social, personal, and financial effects that entails. Homeownership also enables buyers to commit at the time of purchase to a hedging strategy against housing cost inflation. Compared to renters, owners pay higher upfront costs to purchase, but face lower risk of housing cost escalation over time (Sinai and Souleles Reference Sinai and Souleles2005, 785–86).

One of the most important “commitment benefits” of homeownership is lodged not in the property form, but in its financing: forced saving. Much of the financial value of homeownership derives not from appreciation, but from long-term homeowners who pay down the principal each month on traditional, self-amortizing mortgages (the most common mortgage choice) (Shiller Reference Shiller2015, 27-30; U.S. Census Bureau 2013, table 1016). The mortgage is a powerful commitment device that makes the consequences of not paying one’s mortgage costly, disruptive, and humiliating. Homeowners accumulate far greater lifetime savings than similarly-situated renters, as a result of the forced saving component of traditional mortgages, homeownership’s relative illiquidity, and its tax subsidy.

Self-amortizing mortgages, which fuse the monthly principal and interest payment into one amount due, create automatic asset-building – an important point in light of the behavioral law and economics research showing marked improvements in saving when contributions are made automatic and set as the default (Benartzi and Thaler Reference Benartzi and Thaler2004, S166-85; Thaler and Sunstein Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008 103–17; cf. Moulton et al. Reference Moulton, Samek, Loibl and Collins2015, 55–74). Of course, lenders can deter or unravel home-based savings with products such as interest-only and negatively amortizing loans, cash-out refinancing, and home equity lines of credit. Saving through homeownership is suboptimal due to these escape hatches and the undiversified nature of the home investment. However, this form of savings has nonetheless proven financially meaningful, as well as culturally resonant and highly attractive to Americans – in large part due to its advantages as a psychological commitment strategy. The dearth of comparable supports for renter asset-building recently prompted Josh Barros to propose that renters self-fund a savings portion, automatically paid on top of their rent, which would be directed monthly to federal MyRA accounts (Barro Reference Barro2014).1

For their part, landlords contend with renters who are, as Julie Roin and Lee Fennell term it, “understaked” to their residential property and the community (Fennell and Roin Reference Fennell and Roin2010, 16–18). The lack of an equity interest and, in some cases, a strong social stake increases delinquent rent, property damage, and turnover. To date, many of the legal tools available to landlords to address these harms are unpopular with tenants (e.g., fees for late rent), expensive and adversarial (e.g., legal process for eviction), or limited to ex-post compensation rather than prevention (e.g., deducting repair costs from the security deposit). In addition, some state statutes limit the penalties that landlords can impose for delinquent rent and other violations (e.g., Cal. Civ. Code § 1671 (d)).

The shortcomings of the rental form have not only frustrated the preferences of a large subset of renters, but have motivated premature and unstable moves to homeownership (Reid Reference Reid2013, 152–54). Some tenants prefer to rent, particularly at earlier and later life stages; however, most report a preference to own (MacArthur Foundation 2014; Pew Research Center 2011). While abundant survey research establishes the strong inclination toward ownership (MacArthur Foundation 2014, 30; Pew Research Center 2011), it is harder to tease from this data relative preferences for different aspects of homeownership.2 The preference to own is likely due in part to government subsidy of ownership, a benefit I do not focus on in this chapter (e.g., Poterba and Sinai Reference Poterba and Sinai2008, 84–89). The desire to stay in place for a longer period of time appears to be an important trigger for homebuying (Sinai and Souleles Reference Sinai and Souleles2005, 785). There is also evidence that renters’ thin control over rental property and inability to build assets through housing drive preferences for homeownership (Rohe and Lindblad Reference Rohe and Lindblad2013, 7–18).

8.2 Producing Ownership Effects through Incentive-Based Leases

Can any of the benefits and behaviors of homeownership be produced for renters, particularly low-income renters without prospects for ownership? A variety of proposals have sought to create more particularized divisions of residential property rights that redistribute the archetypic benefits of renting and homeowning. Lee Anne Fennell has conceptualized this process as “unbundling” property forms to enable valuable divisions of risk and consumption values and proposed a “homeownership 2.0” form to accomplish this (Fennell Reference Fennell2008, 1070–77). Other approaches, such as limited equity cooperatives, focus on increasing homeownership affordability by limiting equity stake to small shares and restricting rights to appreciation on resale (Davis Reference Davis2009, 29–30; Diamond Reference Diamond2009, 88–109). There have also been a number of proposals to redistribute property risks through alternative financing of homeownership. Most prominently, Andrew Caplin has proposed a residential shared appreciation mortgage where a lender contributes a percentage of the total equity needed by the homebuyer in exchange for rights to a percentage of appreciation upon resale (Caplin et al. Reference Caplin, Cunningham, Engler and Pollock2008, 5–11; see also Arruñada and Lehavi Reference Arruñada and Lehavi2011, 26–33).

There has been decidedly less excitement about alternative property forms based in rental. Municipal rent control has collapsed in discredit, with economic evidence of its ultimate harm to tenants (Green and Malpezzi Reference Green and Malpezzi2003, 126). Subsidized housing alternatives such as rental mutual housing, which gives tenants permanent lease rights at subsidized rates, have mixed records (Krinsky and Hovde Reference Krinsky and Hovde1996, 148–49). Lease-purchase contracts (rent-to-own) show some promise, but have suffered from predatory practices. These contracts often target renters with poor credit, particularly African Americans, who purchase expensive, nonrefundable options only to find later that they cannot qualify for mortgage financing (Way Reference Way2009, 132, 147).

In this chapter, I explore renter equity, an emerging housing paradigm that uses lease-based incentives and commitments to support an alternative rental form.

8.2.A Renter Equity

Renter equity began with the vision of creating an intermediate property form for low-income renters interested in greater commitment, participation, and opportunities for life improvement through housing. In 2000, the nonprofit Cornerstone corporation opened the first of three renter equity apartment complexes in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood of Cincinnati. Cornerstone’s mission is to “help residents of affordable housing reap the potential financial and social rewards of homeownership” (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 9). Renter equity allows renters to earn monthly renter equity credits (i.e., savings credits) in exchange for three behaviors: paying their rent on time, participating in a resident community association and attending its monthly meetings, and completing their assigned property upkeep task in common areas (for ease of monitoring, the typical work assignments require tenants to maintain specified physical spaces in the building or its grounds). The upkeep task takes each tenant approximately one to two hours per week.

The Renter Equity Agreement, which is part of the lease, gives renters rights to earn up to $10,000 in savings credits over 10 years. The monthly savings credit amount increases over time (reminiscent of the principal in a self-amortizing mortgage) (19). Once the resident earns the credit, it automatically deposits into a savings account (Cornerstone Renter Equity 2016). Tenants do not have the ability to access the savings for five years. This provides a measure of homeownership’s behavioral benefits of “forced savings” since the credits must accumulate untouched for at least five years and up to 10 years. If tenants depart prior to the saving credits vesting in year five, they lose their savings credits. Renter equity leases do not specify what happens to the savings credits in the event a tenant is evicted before vesting. It seems the evicted tenant would lose his or her savings credits – a rule that creates incentives for strategic landlord behavior.

High occupancy, reduced turnover, and lower maintenance costs fund the renter credits (i.e., no additional subsidy is required for asset building). Management costs range from 4–12 percent according to industry reports (Muela Reference Muela2017). Estimates peg the cost of apartment turnover at a minimum of $1,000 per unit, with turnover rates of more than 25 percent for subsidized tenants (Barker Reference Barker2003, 3; Lee Reference Lee2013, 67). A recent evaluation of Cornerstone reported a 95 percent occupancy rate (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 38). A comparison of one Cornerstone site (St. Anthony’s) with three comparable federally subsidized low-income housing properties in the same neighborhood found that Cornerstone had similar operating expenses even after funding the savings credits and at least 75 percent less “bad debt” from delinquent rent payment (43).

Another key element of renter equity is the Resident Association Agreement, which establishes the resident association and describes tenants’ obligations and rights of shared governance. The resident association is reminiscent of the legal cooperative or “co-op” form of common interest ownership. In renter equity housing, the resident association works in concert with management and the board to manage certain aspects of the property. The association’s duties include reporting maintenance issues, recommending improvements, coordinating measures to increase safety, and conflict resolution (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 17–18). Resident participation and limited self-governance mark renter equity as a property form rather than an incentive contract. However, this balance between property and contract may be shifting with Cornerstone’s recent changes to management and trademarking of renter equity as an operations model.

Compared to homeownership and traditional renting, renter equity offers a middle ground for residential stability. The renter equity form supports and incentivizes medium-term residential stability through a five-year vesting rule and a 10-year maximum schedule for earning (increasingly larger) savings credits. Renter equity leases do not require tenants to move at the 10-year mark. However, they cannot earn further credits and are unlikely to continue property upkeep and participation – a problematic situation. Unlike homeownership, renter equity does not provide tenants with legal rights to stay put or lock in housing costs long-term. In practice, affordable housing protections and nonprofit involvement provide renter equity tenants greater de facto control over exit and rent costs than traditional renters, but still less than owners. A form similar to renter equity, renting partnerships, has proposed restructuring within land trusts to offer tenants full stability of tenure (Spinney, pers. comm.).

By design, enter equity grafts onto small to mid-size Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) housing and nonprofit affordable housing developments. More than 2 million housing units have been created by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program since 1995, most of which have remained low-income housing past the required 15-year time span (HUD 2012, 49). Government subsidies tend to reward bricks-and-mortar units constructed, as opposed to housing innovation or services. For this reason, private developers of affordable housing have limited incentives to adopt innovations like renter equity; they make sufficient profits without it. This may be beginning to change. Some states now set aside percentages of their LIHTC funds for “innovation rounds” to consider development projects with innovative features (Kimura Reference Kimura2014).

The empirical evidence supporting renter equity is limited, with only one study to date. In 2013, the Ohio Housing Finance Agency and the Corporation for Enterprise Development completed an evaluation of Cornerstone based on surveys and interviews of residents and a review of the renter equity records. The study found that of residents who stayed more than five years, approximately two-thirds earned a median equity amount of $2,600 (26). More than 50 percent of tenants earn credits each month. Most residents used their savings to pay debts or medical expenses. Notably, renter equity has produced median savings comparable to state Individual Development Accounts that provide matched savings to low-income Americans (Miller Reference Miller2007, 26). On measures of housing satisfaction, a high majority of renter equity residents (85–95 percent depending on the specific measure) reported they were satisfied with the unit, the building, and the management (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 93–98).

These findings, while promising, should be interpreted conservatively. This was a single study, sought by Cornerstone. The study design does not rule out selection effects (i.e., the characteristics of tenants attracted to renter equity and able to complete its rigorous application process may have produced these outcomes). In future research, it would be interesting to explore how different aspects of tenant self-selection drive outcomes. For example, would renters who opt for renter equity’s locked-up savings credit have different outcomes than a group that selected a version of renter equity with cash rebates or unrestricted savings? What if tenants were randomized?

Beyond outcomes for renter equity tenants, important and unanswered questions remain about the displacement effects of renter equity on other forms of housing. If renter equity proves successful at providing a share of the benefits of homeownership, might the form attract would-be homebuyers? Renter equity may appeal to scrappy and debt-burdened millennials or working-class retirees who might otherwise purchase homes. It is possible that renter equity could reduce unstable or unsustainable home purchase and help renters to save for down payments. At the same time, renter equity produces less wealth accumulation than homeownership, does not convey the same level of tax benefits, and provides limited liquidity (renter equity tenants have access to a small emergency loan fund). On balance, the magnitude of these displacement effects is likely small. Renter equity’s displacement of homeownership should be modest or minimal under renter equity’s current structure. On the demand side, the upkeep tasks in renter equity are unattractive to many middle- and upper-income individuals, as are the lack of tax benefits and stay-put rights. Supply-side, renter equity would not interest private landlords who have low turnover costs and can exploit opportunities for increasing rent with new tenants (Barker Reference Barker2003, 10).

Renter equity also raises issues of tenant sorting and selection and price discrimination. Households use a variety of means to sort themselves into communities that share similar tastes, goals, and, sometimes, less legitimate factors (cf. Strahilevitz Reference Strahilevitz2011, 16–19). Low-income renters have a similar set of concerns about resident composition, but reduced capacity to differentiate among their fellow tenants in affordable housing. Moreover, low-income tenants typically have greater exposure to negative spillovers given the density of rental housing and its disproportionate siting in urban or low-income areas. Renter equity facilitates tenant sorting into more fine-grained and like-minded groups. The renters who apply to renter equity programs report that they are highly concerned about safety, desire a stronger commitment to their residence and sense of community, and want to build savings (Spinney, pers. comm.). The application process also exerts pressure on selection: tenants must complete three in-person orientation sessions to secure an apartment.

Because tenants self-select into renter equity, the form reveals information about applicants’ preferences for savings, financial aspirations, anticipated residential stability, tastes for cooperation, and inclination toward upkeep. If there is a draw to renter equity for private landlords, it is in its ability to attract high-quality tenants that are less likely to cause property damage and disturbances. More concerning, renter equity could also be a way for landlords to indirectly draw a certain demographic of tenant. For example, the Cornerstone study found that residents in renter equity were more likely to be female, older, and better educated than the median renter at a similar income level (Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 50).

Renter equity facilitates price discrimination by offering higher-quality tenants better housing at a lower rate – it uses a specific system of renter equity savings credits to deliver differentiated pricing. To some extent, price discrimination occurs informally in traditional rental housing as higher-quality tenants negotiate better housing deals or lower rent increases over time. However, the less precise and efficient price discrimination mechanisms in traditional renting often mean that high-quality tenants pay a share of the costs of lower-quality tenants in the form of higher rents. By the same token, one consequence of renter equity’s superior ex ante sorting and ex post pricing differentiation (via savings credits) may be to leave lower-quality, and more vulnerable, renters worse off in terms of rental access and affordability. This poses a normative and distributional question of whether it is socially desirable for higher-quality tenants to subsidize lower-quality ones.

8.2.B Renting Partnerships

In 2014, the creator of the renter equity model, Margery Spinney, departed from Cornerstone to launch a housing form called renting partnerships and launch its first apartment site. Renting partnerships uses the same incentive and leasing structure as renter equity: renter equity savings credits for on-time rent, participation, and upkeep jobs, credit vesting after five years, a tenants’ association, and resident access to an emergency loan fund (Renting Partnerships 2016). Unlike Cornerstone renter equity, renting partnerships makes extensive rights of participation and sense of community the fundamental elements of the property form. In the founder’s view, the incentives function more as a measure of residential participation and personal development rather than as a motivation for it (Spinney, pers. comm.). Accordingly, there is a stronger emphasis on ensuring that renters have input into policies affecting their rentals, including the use of trained facilitators to oversee the tenant association meetings and ensure meaningful participation (McKenzie Reference McKenzie1994, 16–19; Resident Association Membership Agreement 2016, 1).

The legal structure of renting partnerships reflects these priorities. Renting partnerships leases the property from the owner and subleases to the tenants. The Renter Equity Agreement (savings credits) and the Resident Association Agreement run between renting partnerships and the tenants (Renting Partnerships Legal Structure 2016). Renting partnerships chose this legal structure so that it could extend strong and well-enforced tenant rights of participation and make the renting partnership directly accountable to tenants. However, interposing the renting partnership as a lessee of the owner increases costs compared to renter equity, which operates as a manager under contract with the owner.

8.2.C Federal Lease-Based Incentives: The Family Self-Sufficiency Program

The closest analog to the renter equity model, and another example of the recent interest in behavioral leasing, comes from the federal HUD Family Self-Sufficiency Program (FSS) enacted in 1990. FSS aims to motivate tenants to increase their earnings through lease-based incentives in the form of savings credits. Typically, low-income residents receiving HUD assistance must pay higher levels of rent as their income increases. In the FSS program, HUD deposits the increment of rent attributable to higher income in a savings account for the tenant. Tenants can withdraw the savings once they fulfill their Contract of Participation. This typically occurs in five years and requires that the family head be employed full-time and no other family members receive welfare. FSS is available to residents of HUD public housing as well as to Housing Choice Voucher recipients dispersed in private rentals. Housing Choice Voucher recipients pay 30 percent of their monthly adjusted gross income to rent apartments in the private market, with a voucher from their local housing authority covering the balance (24 C.F.R. §982.1(a)(3) (2016)).

A 2011 study that tracked 191 FSS participants found that at year four of five in the FSS program, 24 percent had met program requirements and graduated with an average escrow account of $5,300, 37 percent left the program before graduating, and 39 percent were still enrolled and accumulating savings (HUD FSS Evaluation 2011, 32–33).3 It is possible that FSS has stronger effects on asset building than on employment. Interim results from a study of New York City participants report effective asset building, but only show positive employment effects for the subgroup of residents who were not employed at all when they entered FSS (Nuñez et al. Reference Nuñez, Nandita and Yang2015, 26, 140–41).

8.3 Lease-Based Incentives as Surrogates for Equity

Far from an elegant model, renter equity is a veritable patchwork of property rules, institutions, and incentives. Into this jumble, it mixes psychological elements of commitment strategies and framing, the theme of life improvement via housing, a savings credit schedule reminiscent of mortgage principal accumulation, and the ability to use housing for liquidity (the resident emergency loan fund). The core innovation of the renter equity approach is to allocate to tenants the right to some of the value of their property-benefiting behaviors – and then to explicitly frame and market that right as an illiquid incentive payment in order to support a range of behaviors. This form offers a model of how psychology, in the form of behavioral incentives and commitment devices, can produce certain ownership effects – a model that raises intriguing possibilities as well as legal and policy concerns.

8.3.A Creating Rights to the Value of Property-Benefiting Behaviors

The renter equity agreement creates a limited right for tenants to a share of the value of their property-benefiting behaviors. This is an innovation that simultaneously lessens two key shortcomings of rental: disincentives for tenants to maintain and improve property and lack of asset-building opportunities. It also capitalizes on certain efficiencies of possession for maintenance and management. By virtue of being on site daily, tenants often possess a great deal of information relevant to upkeep, maintenance, and aspects of management. In typical rentals, tenants cannot capture the investment or management value of their property-benefiting actions, only the consumption value. As a result, tenants typically engage in less upkeep, improvement, and beautification of rental property than comparable owners (Rohe and Stewart Reference Rohe and Stewart1996, 48), though not necessarily less local volunteering or civic engagement (DiPasquale and Glaeser Reference DiPasquale and Glaeser1999, 382–84; Stern Reference Stern2011, 102–04).

The renter equity savings credit is not a prototypical property right. It is not an equity share with rights to property appreciation, and there is only a rough correspondence between the behaviors sought by renter equity and the savings credits. Appreciation is difficult to measure in advance of sale, particularly for rent-restricted affordable housing, which does not appreciate in a typical fashion (HUD 2012, 24). Instead, renter equity uses a predetermined schedule of credits based, presumably conservatively, on a tenant’s anticipated share of the savings from reduced maintenance and turnover (e.g., $60 in month 1, $62 in month 2, etc.). Calculating credits based on a share of annual operating savings might be more efficient or motivating, but would decrease certainty, breed resentment if payouts fall short of expectations, and potentially mute the incentive’s salience by using a share rather than a concrete dollar amount.

Because the money for the savings credits comes from management savings and reduced turnover, renter equity solves a common problem of incentives: the need for a costly stream of subsidy (cf. Galle Reference Galle2012, 814–16).4 At the same time, renter equity adds a unique, asset-building component to rental. Despite increasing national attention and funding for asset building for low-income Americans, effective savings programs for this cash-constrained group are rare (Schreiner and Sherraden Reference Schreiner and Sherraden2007). Renters have dramatically lower levels of savings and multiple barriers to asset building (Joint Center for Housing Studies 2013, 13). The lack of renter assets is particularly concerning because renter households are increasing at a rate not seen in the past half century and the percentage of middle-aged renter households is rising (1–3).

Renter equity has proven effective at building a modest level of assets for tenants by creating rights to the value of their property-benefiting behaviors (i.e., the savings credits). However, it has failed to articulate its goals for savings (e.g., pay debts, develop emergency fund, or long-term savings), which leaves the form vulnerable to the criticism of “savings for savings’ sake.” It is also not clear that housing, particularly rental housing, is the optimal vehicle for savings. Renter equity savings is undiversified and has less legal protection than retirement accounts, securities, or home equity. As I will discuss in Section 8.3.C, illiquid savings accounts can also be problematic.

In attempting more fine-grained allocations, renter equity exposes shared or overlapping interests between tenants and owners and the difficulty of teasing apart respective rights and obligations. Owners are justifiably concerned that renters will create costly misallocations or negative externalities that the owner will bear the cost of correcting (cf. Fennell 2009, 16). Also landlords may worry about violating landlord-tenant laws and habitability provisions (though liability seems unlikely since landlords retain responsibility for major maintenance and repairs). In practice, the renter equity lease has only partially resolved these issues by vesting responsibility for major alterations, major maintenance, and residual upkeep (i.e., what the tenants do not accomplish) in the landlord, while tenants participate in the annual operating budget, upkeep and minor maintenance, house rules, and decorating. If private landlords are to adopt renter equity in any number, they will require additional assurances against damage and greater ex ante clarification of their rights to intervene if tenant action dissipates value.

Renter equity’s reallocation of property rights and responsibilities also raises concerns about unregulated labor and labor efficiency. Do we want unregulated tenant labor to displace regulated labor in renter equity apartments? Renter equity is likely not subject to labor and wage standards because the tenants have management duties and serve on managerial committees (cf. Simpson v. Ernst & Young, 1996, 434–44). There is also an efficiency issue of whether residents are the best providers of maintenance and upkeep. Would it be more efficient for tenants or landlords to hire out upkeep tasks? Renter equity does not allow such substitution, in part because of the emphasis on building community. In practice, the constraints of affordable housing may mitigate these concerns. At affordable housing sites, it is not a simple choice between regulated and unregulated labor. Absent resident participation via renter equity, some of the upkeep would not occur at all.

8.3.B Framing Incentives to Produce Ownership Behaviors and Benefits

The renter equity model frames the value of residential contributions as an incentive for tenant participation and adherence to the property form. Indeed, the savings incentive might inspire less action, or more conflict, if renters thought of the credits as property rights that should have been recognized previously. The savings credits accrue monthly, which provides what psychologists refer to as periodic reinforcement, rather than a less motivating schedule such as annual accounting. Even the term renter equity is compelling, suggesting both financial accumulation and personal stake. This is not to claim that incentives, however artfully defined and marketed, will persuade highly resistant renters. Instead, the incentives support ownership-like behaviors in concert with preexisting tenant motivations (selection), legal rules and expectations for the required renter equity behaviors, and the development of norms of resident participation (cf. Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 34).

Psychologically, incentives have a number of advantages for altering behavior. First, incentives increase the salience of certain behaviors. They communicate what is important to the entity providing the incentive, draw attention to those behaviors, and serve as ongoing reminders over time (Karlan et al., Reference Karlan, McConnell, Mullainathan and Zinman2016, 2, 16). Second, incentives provide positive reinforcement of the desired behavior that increases its frequency (and may eventually create habits). Incentives can also help maintain the renter equity system against free riding and other collective action problems. Third, there is some evidence that incentives maintain good relations between parties by cultivating positive associations with the people connected to the incentive (Tyler and Blader Reference Tyler and Blader2000, 41). It is possible that penalties, taken from residents’ existing assets, may be more effective than incentives at producing desired behaviors due to loss aversion (Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1990, 1325–48; Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979, 263–74). However, for behaviors that are not part of traditional lease obligations, such as upkeep, penalties seem misplaced (cf. Galle Reference Galle2012, 834) and likely illegal under some tenant protection laws. Moreover, penalties are costly to enforce and often impossible to collect against judgment-proof tenants.

Residential leases have strengths as instruments of behavior change. They enable access to tenants and typically operate based on monthly rent, which can demarcate or deliver incentives. There is often preexisting rental management in place that can lower the incremental cost of administering incentives. Of course, incentives need not, and often should not, be tied to property. However, we might structure incentives within the property form in certain instances, such as when the target behaviors are residential or associated with property, the incentive is more efficiently monitored or administered on site, or the incentive payment is the housing itself.

In renter equity, the savings incentive supports behaviors that track homeownership, albeit in smaller magnitude and altered form. These behaviors include upkeep obligations, participation rights and limited self-governance, longer durations of residence, asset building, and a more “ownership-like” relationship to one’s residence. The incentives directly reward three behaviors (upkeep, the monthly resident meeting, and paying rent on time). The resident association and the vesting rules for renter equity then sweep into the incentives’ ambit a host of other behaviors, including participation in social events, creating and enforcing the house rules, and residential longevity.

Notably, renter equity frames the incentive not as a bald payment, but rather as an “equity-like” savings credit that represents opportunities for life improvement (evocative of homeownership). By emphasizing these positive connotations, the form likely produces stronger behavioral effects than it would otherwise. An immediate cash payment or shopping gift card is also motivating, but would undermine renter equity’s attraction to lower-income tenants as an alternative to traditional renting and an asset-building vehicle.

The flip side of the psychological power of incentives is their vulnerability to abuse. If incentive-based behavioral leasing proliferates, the legal system may need to address misleading or deceptive incentives as landlords attempt to capture the value created from tenant contributions. For example, less scrupulous landlords may mislead tenants about incentives or offer incentives in complex forms that are difficult to understand. These practices have occurred with other consumer incentives, such as loyalty points programs (Dougherty Reference Dougherty2013).

8.3.C Renter Equity as a Commitment Device

Renter equity employs what psychologists refer to as commitment strategies to shield tenants’ savings from later willpower failings and time-inconsistent preferences (Ayres Reference Ayres2010, 45–47; Kurth-Nelson and Redish Reference Kurth-Nelson and Redish2012, 1–2). A large body of research in psychology, law, and economics converges on the finding that commitment strategies are an important tool to mitigate bounds on willpower and address present bias and hyperbolic discounting (Ayres Reference Ayres2010, 20–55). For example, making a visible public commitment to exercise, agreeing to pay a penalty for not exercising, and selling your car so you must walk to work all reduce the likelihood of yielding to sedentary temptations.

As David Laibson recognized two decades ago, illiquid investments, including housing, offer a mechanism for commitment (Reference Laibson1997, 444). He refers to such illiquid instruments as “golden eggs” that increase savings (and that can be undermined by financial products that enable instant borrowing against the illiquid asset) (445, 465). Housing illiquidity offers one strategy for insulating people’s “future selves” from the temptation to spend, as well as to relocate. For example, research by Thomas Davidoff suggests that homeowners use housing illiquidity to save for long-term care rather than purchasing long-term care insurance (Reference Davidoff2008, 15–22).

Renter equity offers a potent commitment device for ensuring tenants save: it makes the savings illiquid for five years. This is similar, though not identical, to the illiquidity of home equity (at least prior to the advent of cash-out refinancing and reverse mortgages). Of course, illiquidity can also have undesirable effects, particularly for low-income renters. When new situations or economic shocks arise, it may make sense for tenants to access savings. In the face of a liquidity crisis, tenants may accept punishing interest on payday loans or defer needed health care, for example, because they cannot access their renter equity funds. Renter equity only partially addresses this problem through a resident loan fund for residents who need short-term loans for emergencies and move-in expenses.

Renter equity may not appeal to the renters who need commitment devices for savings the most. A significant subset of the population misestimates how time and flagging willpower will affect their future decisions (i.e., they don’t believe they will have self-control problems). Non-mandatory or opt-in commitment devices are often not effective for this subset, who choose not to adopt them. Ted O’Donoghue and Matthew Rabin suggest an interesting solution. They describe a hypothetical policy where people opt into a combined potato chip tax and carrot subsidy. People who recognize that they have imperfect control will opt in to this commitment device. However, so will “naifs” who don’t realize their limited self-control and view the policy as a gratis subsidy (they believe they will only consume carrots) (O’Donoghue and Rabin Reference O’Donoghue and Rabin2003, 186–90). Renter equity or other renter savings programs might experiment with this approach. For example, they could offer a savings account that tenants may withdraw from at any time and then an opt-in policy. The opt-in would impose a tax on early withdrawal and a bonus (subsidy) for allowing the money to accumulate for a certain period of time or periodic subsidies for each year the money remains untouched. Individuals who want to build savings and realize they have self-control problems will opt into the program, but so will those who are unaware of their self-control problems. Of course, if the costs of illiquidity are too high relative to its benefits, tenants either won’t opt in or may opt in to their detriment because they also misestimate their liquidity needs or are overoptimistic about the perceived subsidy.

In addition to savings, the five-year vesting period also provides a commitment strategy for residential stability. The commitment structure allows renters, like owners, to embed ex ante preferences for residential stability into their housing by choosing a form (renter equity) that increases the costs of exit. Lodging the value of tenants’ property-benefiting behaviors in late-vesting savings accounts provides incentives to stay put and, by design, distorts exit decisions. This undermines some of the virtues of rental: mobility and low costs of exit that enable tenants to respond to changed preferences and new opportunities. On the other hand, duration tends to increase both social ties and social contribution, which are important to the renter equity model. As a practical matter, a substantial percentage of renter equity residents are disabled or chronically ill; for these groups, geographic mobility tends to be lower anyway (Spinney pers. comm.).

There may be ways to lessen stability distortions in renter equity. Renter equity might integrate elements of the Family Self-Sufficiency Program by allowing residents to withdraw their savings early without penalty, and possibly an additional financial bonus, for achieving income that disqualifies them from subsidized housing. If renter equity were to proliferate, presumably via government or nonprofit support, a transfer system could evolve to allow tenants to move between different (possibly subsidized versus unsubsidized) rental equity sites. Renter equity could also shorten the time period for vesting. This would decrease asset accumulation for tenants as well as the amount of renter equity the landlord could provide, as turnover would increase. Another option would be to keep a five-year vesting rule but allow immediate, partial vesting if tenants leave their rental or if the building is sold. Either a shorter vesting period or an escape hatch approach would enable greater mobility and discipline against landlords’ temptations to lessen services or otherwise exploit tenants’ desire to stay in place for the five-year vesting window. These options also lessen renter equity’s downsides for marketability: landlords want flexibility to sell their buildings without narrowing their market to those willing to manage the building with renter equity (tenant buy-out provisions may also address marketability, albeit at a cost to landlords).

8.4 Psychological Pitfalls of Renter Equity and Mitigating Effects

Renter equity leverages psychology to structure and support its alternative housing form. Like any policy tool, psychology can fail. This section considers the potential for psychology to unravel or have unintended consequences in practice. Specifically, I examine the risk that incentives will crowd out intrinsic motivation and voluntary behavior and the potential harms from renter equity’s behavioral control of tenants.

8.4.A Crowding Out Motivation and Behavior

In some circumstances, incentives may reduce or “crowd out” the target behavior (Frey and Jegen Reference Frey and Jegen2001, 591–96). When this happens, people put forth less effort and produce less behavior than they would have in the absence of any incentive. Crowding out happens most commonly in the long run after an incentive is removed, but it can also occur when the incentive is still in place (Gneezy, Meier, and Rey-Biel Reference Gneezy, Meier and Rey-Biel2011, 193). The research literature offers several explanations for crowding out: a loss of intrinsic motivation in the face of external rewards (Deci Reference Deci1971, 105–10), the inference from payment that the task is unpleasant (Bénabou and Tirole Reference Bénabou and Tirole2003, 479–89), and compromise of one’s image when prosocial behavior follows from payment (Ariely et al. Reference Ariely, Bracha and Meier2009, 544–55). Incentives appear particularly vulnerable to crowding out when the incentive is visible to others and the behavior is “noble” or prosocial (Kamenica Reference Kamenica2012, 13:18). This suggests a reason for not offering explicit incentives for residential activities such as volunteering in the community.

Why didn’t the renter equity incentives produce the calamitous effects predicted by the research on crowding out? Based on the limited evidence available, the data from the Cornerstone study and my interviews with renting partnerships, the savings credit incentive supported on-time rent, created more attractive and better-maintained housing, and increased residential participation, satisfaction, and sense of community. These results may be due to attributes of the residents themselves, who self-select into the program following an extensive orientation process. Perhaps more to the point given the inevitable issue of selection bias, what factors might we expect would make incentives less at-risk for poor behavioral outcomes in renter equity or other forms of behavioral leasing?

First, the long-term nature of incentives in the renter equity form is a major protective factor against declining effort and reduced behavior output. Behavior can dwindle while incentives are in effect. But this is much less common and appears to occur when the incentive is not large enough, communicates a message of low social regard, or is so oversized as to induce anxiety and “choking” (Gneezy and Rustichini Reference Gneezy and Rustichini2000, 791–98; Heyman and Ariely Reference Heyman and Ariely2004, 787–90). The self-funding nature of the renter equity incentive enables an ongoing stream of incentive payments (renter equity keeps money in the operating reserves so that if cost savings are not realized for a discrete period, the incentive will still be paid). We might expect problems when the 10-year period for renter equity ends and residents stop collecting credits, which is just beginning to occur at Cornerstone. In that case, it seems unlikely tenants will continue to engage in upkeep or participate as frequently in tenant meetings. Renting partnerships does not place an expiration date on earning savings credits for this reason (Renting Partnerships 2016).

Second, the structure of renter equity may buffer against motivational harms. Homeownership offers a paradigm of embedding incentives and cloaking them with positive social meaning. Similarly, renter equity affords tenants more control and decision-making power and has connotations with ownership – a desirable social status. These positive meanings may reframe the incentive in a more personally and socially admirable light. The form of the incentive may reduce crowding out as well. There is evidence that crowding out occurs most commonly for monetary payments. In renter equity, the incentives take the form of a monthly savings “credit” that goes into an account for five years rather than an immediate cash payment. Of course, not all aspects of the savings credit are desirable or empowering. Renter equity tenants receive their savings credits on the judgment of a third-party administrator who monitors the defined spaces that each tenant maintains. This may suggest low trust, signal negative perceptions of residents, or alter the nature of relations from social to monetized or hierarchical. This point suggests a symbolic importance to renter equity’s participatory structures. Some amount of resident governance (though perhaps less than the full amount envisioned by renter equity and especially renting partnerships) seems necessary to prevent renter equity from taking on the paternalistic flavor of an allowance for chores or becoming a labor contract.

Last, practically speaking, concerns about crowding out are often overblown for the simple reason that many behaviors subject to financial incentives would not have occurred but for the incentive. For example, low-income renters have a negative savings rate and are very unlikely to save voluntarily. Even among middle-income households, the savings rate is startlingly low (Guidolin and La Jeunesse Reference Guidolin and La Jeunesse2007, 491–94, 512). With respect to upkeep and residential participation, the motivational picture is more complex. For example, a tenant may voluntarily pick up litter when he passes it or plan a resident gathering, but he would not voluntarily engage in the one to two hours of weekly upkeep of common areas that renter equity requires. Paying rent on time is perhaps the behavior most vulnerable to crowding out. However, this behavior is subject to a stick (the lease obligation to pay rent and remedies such as eviction) as well as a carrot (the savings credit).

Beyond specific behaviors, could savings credits crowd out one’s civic or altruistic orientation toward residential living or stymie the more “owner-like” personal dispositions that renter equity seeks to cultivate? The psychology and economics research on incentives is less illuminating here because it has focused on measurable behaviors, with less attention to dispositions or attitudes. Even if we assume that a crystallized, prosocial orientation toward residential living exists, it is not clear whether incentives linked to renter equity support or undermine it given renter equity’s positive connotations with savings, life improvement, and a social “equity stake” in housing.

8.4.B Controlling Personal and Social Behaviors

Linking scarce housing to financial incentives for upkeep tasks and participation in resident meetings could be seen as classist or coercive – or a possible gateway to leases that attempt to incentivize more personal behaviors and choices. Renter equity exercises a substantial amount of social control over tenant behaviors and interactions. Residents must join and participate in the tenant association to earn renter equity credits as well as consent to extensive house rules that include obligations to escort guests out the door, report safety concerns, forego long-term houseguests, and engage in peer mediation of conflicts (House Rules 2016, 1–2). Incentivizing or requiring certain behaviors as part of one’s lease is an uneasy fit with notions of autonomy and liberty, as well as theories of property’s particular role in securing liberty (cf. Ely Reference Ely2008, 43). Homeownership incentives, in contrast, are intrinsic, less direct and visibly controlling, and the product of a choice to buy. It may feel and mean something different to perceive that your behavior is influenced by ownership of your property versus a rental incentive payment.

Another criticism might be that the renter equity model imposes a class-based notion that low-income residents need only adopt a better work ethic or habits of participation to improve their lot in life and become more productive citizens. To some, the upkeep tasks may seem insulting. As a practical matter, however, low-income tenants often receive barebones property upkeep services and may prefer to have an option to coordinate with other tenants to provide a higher level of service.

The pivotal issue for tenant liberty and dignity interests may be whether residents have a meaningful choice to opt into renter equity, with its mandated social structures and “sweat equity” component. The lack of affordable housing for low-income renters is severe, with only 32 housing units available for every 100 very low-income renters (Furman Center 2012, 3). Should renter equity expand, it is not clear whether residents competing over a severe undersupply of affordable units can choose whether or not to enter into a behavioral lease – indeed, this may be a new twist on the concerns of “unequal bargaining power” that animated landmark landlord-tenant cases (e.g., Javins v. First Natl. Realty Corp (D.C. Cir. 1970)). Yet, discarding forms such as renter equity and renting partnerships based on concerns about choice would foreclose housing options from tenants, a result that seems both undesirable and ironic.

Beyond renter equity, there is a broader question of whether we are starting down a “path of behaviorism” in leasing that may lead to other, more objectionable attempts to control the personal behaviors and choices of tenants. This is a deeper question, beyond the scope of this chapter. For now, I note that while fair housing acts provide some safeguards against overreaching, there may be a danger to acclimating ourselves to behavioral leases that regulate or incentivize personal behaviors.

8.5 Conclusion

Renter equity fills a gap between traditional rental and homeownership – but, in certain respects, rests uneasily within it. The form offers a number of innovations. It enables asset building for renters through their rental interests. Renter equity also offers relief from the stranglehold of traditional renting by allowing tenants greater control and governance. Focus group research by Cornerstone has found substantial interest among low-income renters for renter equity (asset building), greater participation in their residence, and safer housing (Spinney, pers. comm.). With respect to neighborhoods, while the renter equity sites have not deconcentrated poverty, they may deconcentrate dysfunction by drawing more responsible, motivated, and educated low-income residents to distressed neighborhoods (Dawkins Reference Dawkins2011, 35–37; Drever et al. Reference Drever, Brumfield, Decker, Sims, Passty and Wilson2013, 35–36).

To expand, renter equity will need to resolve a number of legal and policy issues. These questions include how the form will address stay-put rights, incentives for residential stability, disbursals of savings credits upon eviction, and landlord abuse or fraud with respect to the tenants’ savings credits. Until recently, Cornerstone renter equity was content to limit the program to three carefully tended sites (Spinney, pers. comm.). As a result, there has been limited development of or experimentation with the renter equity form. For example, it is not clear if all of the many moving parts of renter equity are necessary to sustain the form. Less elaborate structures of participation and community building would make the renter equity form more “scalable” to other sites, but could undermine the program’s success.

Perhaps renter equity’s most important contribution is as a model of innovation of an intermediate housing form for renters, supported by lease incentives. Traditionally, the residential lease divided the respective property rights and obligations of the landlord and tenant along the standard dimensions of possession and residual ownership. This division was cast at the time of lease signing and frozen into place for the term of the lease. Neither the historical property-bound view of leases nor the post-1970s contractual paradigm contemplated explicit, ongoing incentives in residential leases. Renter equity, and other behavioral leases, represent a novel iteration of the rental form – one that increases the continuum of housing options and raises new issues for property law.

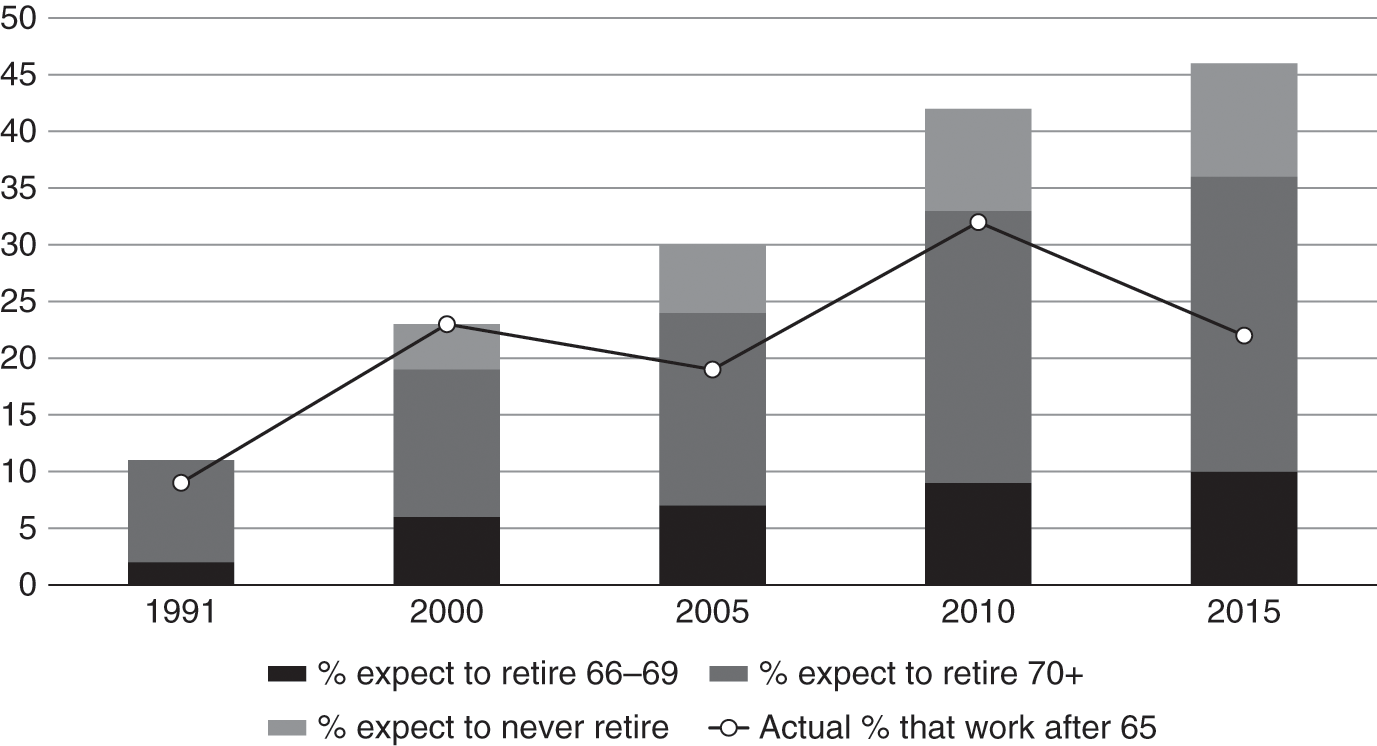

Many policy makers and business experts have expressed concern about the deteriorating savings and retirement readiness of older Americans. The Federal Reserve 2015 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking states that “Thirty-one percent of non-retired respondents report that they have no retirement savings, including 27 percent of non-retired respondents age 60 or older.” Measurements from the Boston College National Retirement Risk Index show “52 percent of households are ‘at risk’ of not having enough to maintain their living standards in retirement.”1 Fidelity Investments notes that “More than half of Americans [are] at risk of not covering essential expenses in Retirement.”2

Several factors may be contributing to the growing financial challenges facing older Americans, including reduced pensions, increasing debt, and low savings. In previous generations, retirees relied on defined benefit plans offered by larger employers and Social Security to cover retirement expenses. Yet today “only half of American workers have access to an employer-based retirement plan.”3 As well, Social Security is facing its own financial challenges, and many experts are proposing an increase in the retirement age.4

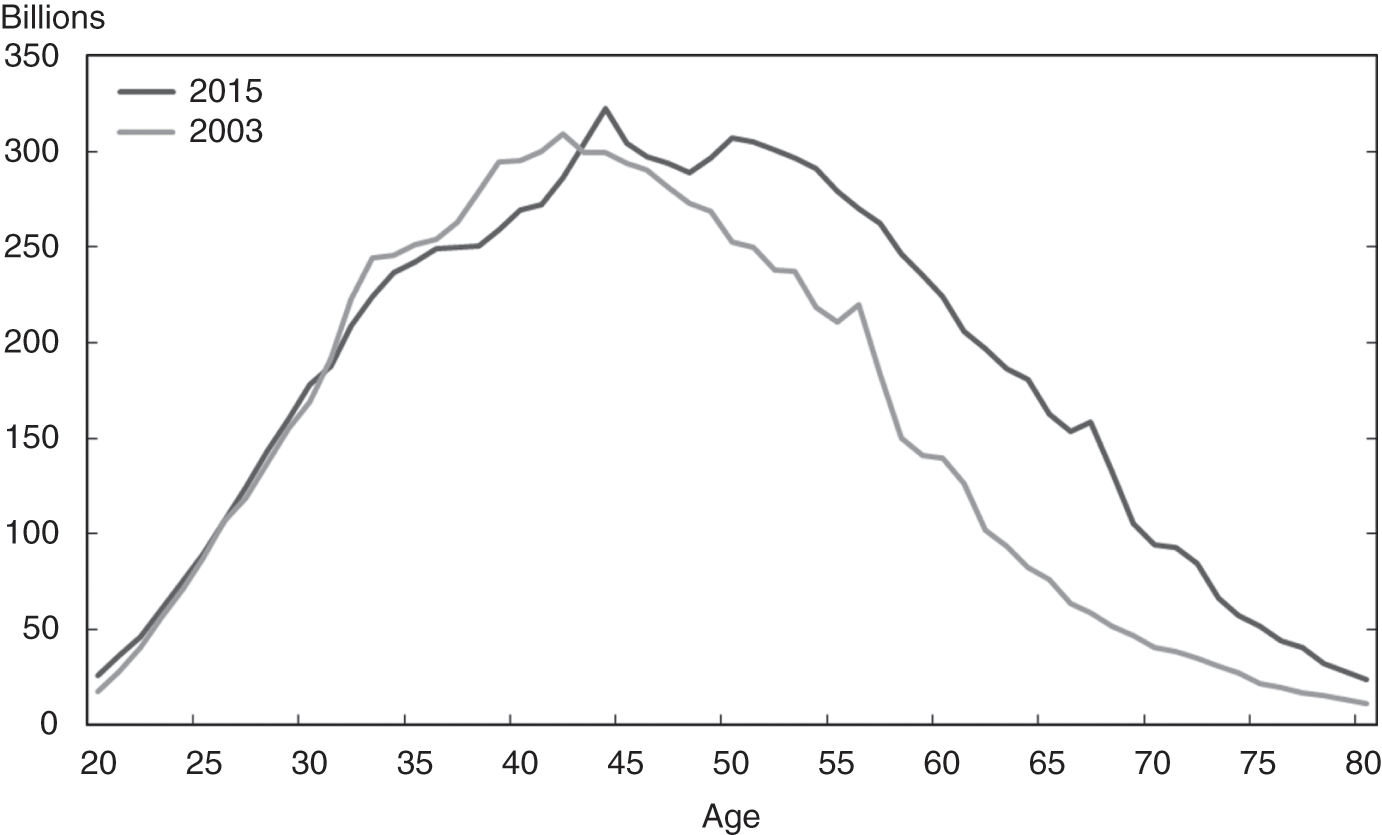

At the same time that the coverage of pension plans is shrinking, debt among the elderly and near elderly is growing. According to researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York,5 “Debt held by borrowers between the ages of 50 and 80 … increased by roughly 60 percent (between 2003 and 2015).” See Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Total Debt Balance by Age of Borrower

The predominant factor driving increased debt was mortgages taken out in the 2000s; credit card debt actually fell over the same period for older households.6 This result is not surprising. After all, Greenspan and Kennedy (Reference Greenspan and Kennedy2005) pointed out that homeowners extracted $564 billion of home equity per year from 2001 to 2005.

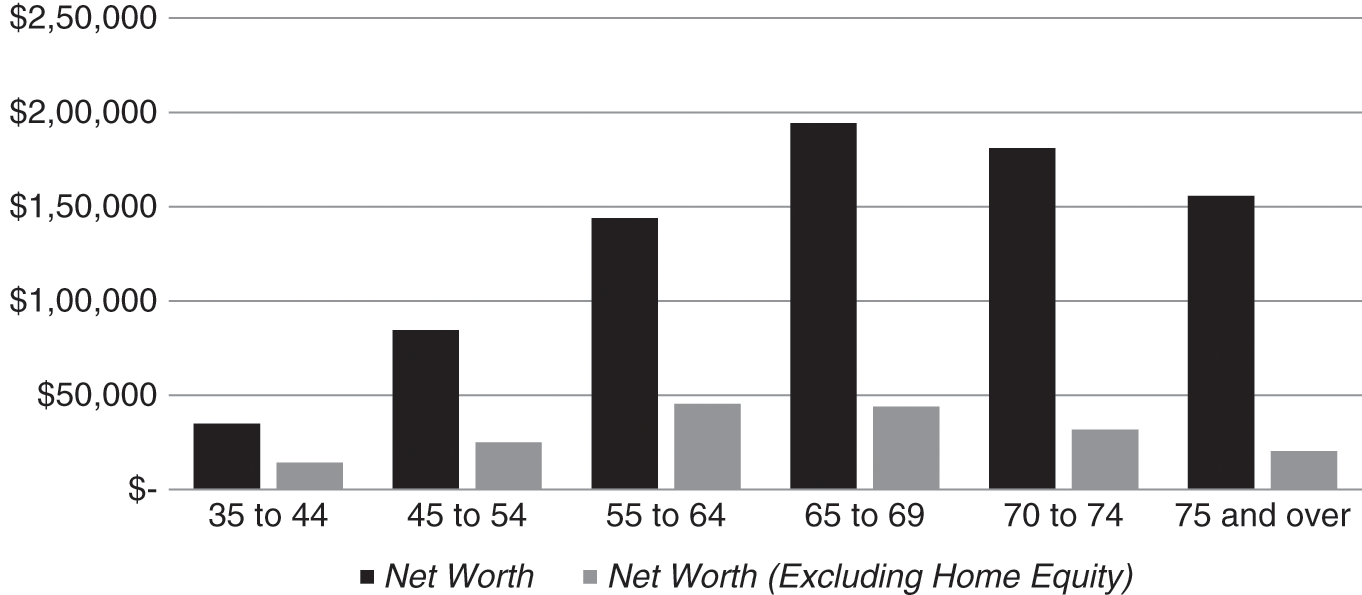

Unfortunately, as debt is rising, most Americans of retirement age still have low balances of financial assets. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, median net worth excluding home equity in 2011 for the elderly aged 65 to 69 was only $43,921 (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Median Net Worth in 2011

Thus it is not surprising that Poterba and colleagues (Reference Poterba, Venti and Wise2011) show that “Even if households used all of their financial assets … to purchase a life annuity, only 47 percent of households between the ages of 65 and 69 in 2008 could increase their life-contingent income by more than $5,000 per year.” Savings are not large enough at this point to address the growing needs of the elderly.

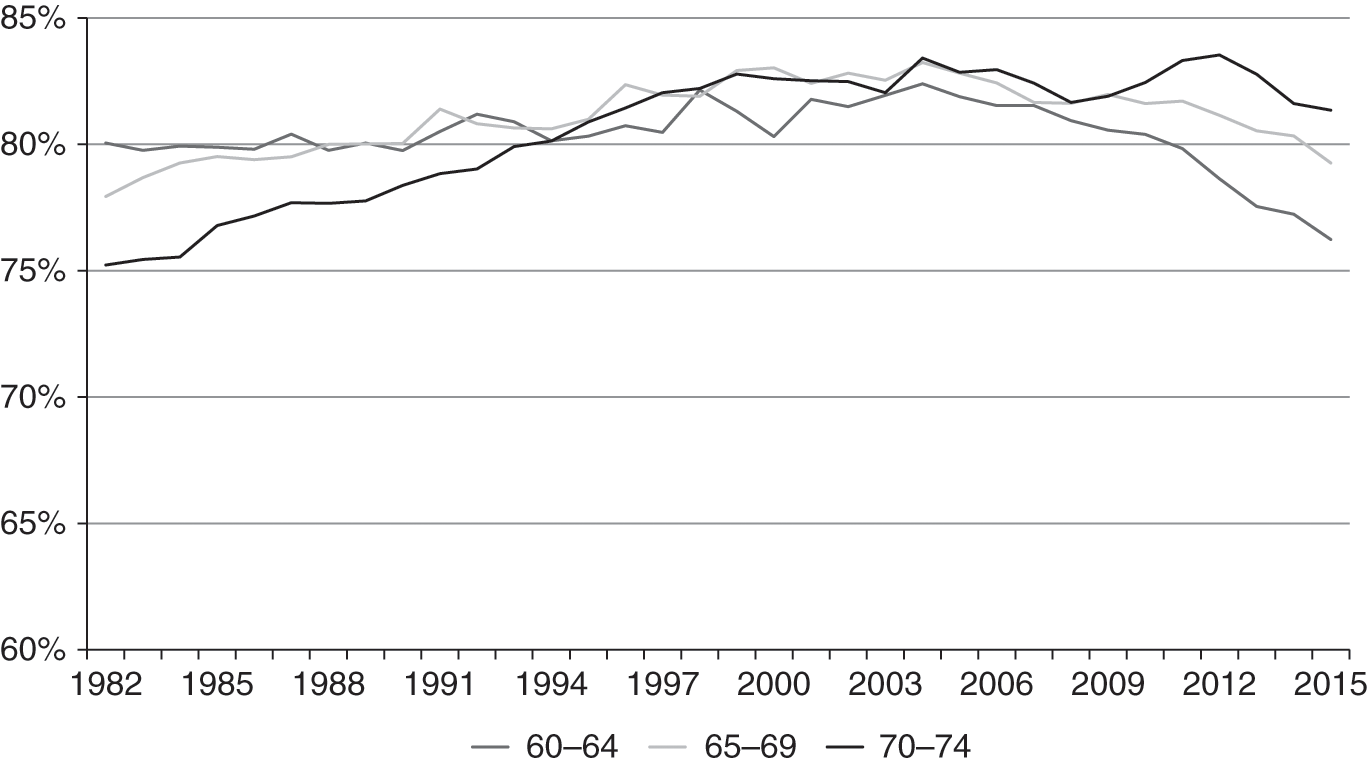

For older households struggling to finance retirement, owning a home may explain how many retirees are able to successfully get by.7 As shown in Figure 9.3, the share of elderly households owning their home increased by about five percentage points from 1982 to 2012 to a peak of nearly 84 percent of those aged 70 to 74. Since that time, the rate has fallen a bit (to 81 percent), but the vast majority of the elderly own their primary residence today. Owning a home can substantially reduce expenses and risk associated with retirement (Sinai and Souleles Reference Sinai and Souleles2005).

Figure 9.3 Homeownership Rate for Elderly Households, 60–74 Years Old

Homeowners appear more prepared for retirement than renters in almost every way. Census data show that median net worth including home equity is considerably larger than without (Figure 9.2) – almost $195,000 for households aged 65 to 69 in 2011. Poterba and colleagues (Reference Poterba, Venti and Wise2011) show that housing and real estate wealth exceeds the total of financial assets and personal retirement accounts for households of the same age. Even more striking, the authors show that real estate represents almost 80 percent of the present value of Social Security income.

In what follows, I examine the growth in mortgage debt and home equity for the elderly using the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) and consider how retirees are able to manage debt and utilize home equity in retirement with data from the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS). Previous academic research often examines home equity as a share of net worth without considering the amount of mortgage debt.8 Indebtedness is important to consider in its own right given the way many households now pay for their costs in retirement, predominantly financing expenditures from cash flow rather than spending down their stock of assets. As Poterba and colleagues (Reference Poterba, Venti and Wise2011) point out, the typical household appears to treat home equity and non-annuitized wealth like precautionary savings, which they spend only very late in life.

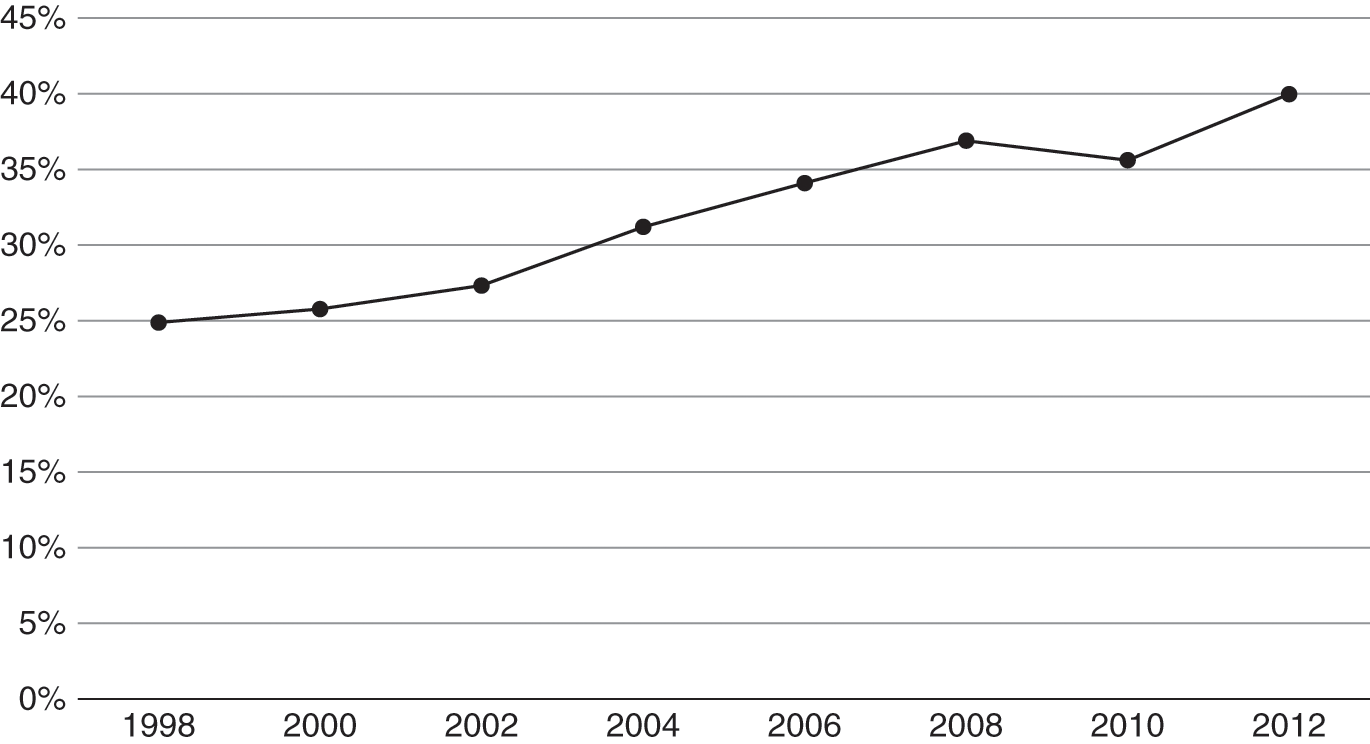

The data show a striking increase in mortgage debt at or near retirement age since 1992. For example, about 40 percent of households age 66–71 have a mortgage in 2013, up from 25 percent two decades earlier. At the same time, the average amount of mortgage debt (in 2013$) has almost tripled from less than $20,000 to more than $55,000. By contrast, real home equity in 2013 is at about the same level as it was almost 15 years earlier for most older homeowners. These data make clear that the growth of housing debt in the boom prior to the Great Recession remains on the balance sheets of many older households today.

Next I consider the evolution of mortgage debt versus financial assets over time. Debt is not necessarily a problem if homeowners have more assets to pay back the debt. Unfortunately, not only has debt increased as a share of home values, it has also increased relative to financial assets. About 40 percent of homeowners with a mortgage aged 65–69 had more mortgage debt than the sum total of all of their financial assets in 2012, up from about 28 percent in 1992.

Having established the growth in housing debt, I examine data from previous cohorts of older homeowners to examine how these households have historically managed mortgage debt and spent down home equity and financial assets over time. This analysis builds on a pair of papers by Poterba and colleagues (Reference Poterba, Venti, Wise and Wise2012, Reference Poterba, Venti and Wise2015) that examine the net worth of the elderly in the year just prior to death as well as examining the evolution of assets from retirement age to just before death.9

The evidence shows that few homeowners spend down home equity until very late in life. For a sample of borrowers first observed at age 53–63 in 1994 and who die within 18 years, the share without home equity increased slightly from 31 percent to 34 percent. For elderly first observed over age 70 in 1992 and who die within 15 years, the share without home equity doubled from 22 percent to 44 percent.10 Even for the oldest households in the sample, however, the majority own a home in the year prior to death.

Next I examine the link between home equity and financial assets. Poterba and colleagues (Reference Poterba, Venti and Wise2015) show that for households entering retirement with assets, most of those assets remain unspent unless the household has a disruption in family composition or a member with an important medical event. I expand on their analysis by separating assets into home equity and financial assets. The results show that most older households only spend down home equity in the years just prior to death when they enter assisted living. By contrast, households spend down 30 percent to 40 percent of financial assets. Homeowners with larger amounts of financial assets are slightly less likely to reduce home equity, potentially because they have the resources to age in place in their home rather than selling the home and moving to assisted living.

Putting these results together, my findings suggest that the prognosis for financial stability in retirement is getting worse because more households are entering retirement age with greater amounts of debt. This trend is likely to continue as younger cohorts are nearing retirement age with more debt than previous cohorts, whether measured in real dollars or as a share of home value (loan-to-value ratios are also rising). While many elderly have large amounts of home equity (which often exceeds other financial assets, including retirement accounts), most do not use that home equity to fund retirement.

This chapter has two empirical sections. The first examines the Survey of Consumer Finances to determine changes in household balance sheets and borrowing when heading into retirement. The second examines data from the Health and Retirement Survey to study how households spend down home equity and financial assets. This chapter concludes with ideas about a future policy and research agenda.

Housing Debt in Retirement

To begin, I examine data from the Survey of Consumer Finances to track homeownership and borrowing by families at or near retirement age. The analysis is conducted by age as well as by following cohorts of borrowers in six-year age intervals from 1992 to 2013. The six-year age intervals were designed to allow the reader to compare housing behavior of some cohorts.

Data Description

The Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) is sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board in cooperation with the Department of Treasury. It is a cross-sectional survey of families in the United States that has taken place every three years since 1983. I start with the 1992 survey, which was the first date that the SCF was built to provide a nationally representative sample, using waves in 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, and the latest published wave in 2013. The survey collects information on assets, liabilities, pensions, income, and demographics. About 6,500 families participate in each wave of the survey, which means that it can be difficult to separate into smaller groups of elderly without some sampling error. The yearly survey data were downloaded directly from the Federal Reserve website. Dollar-denominated variables are reported in 2013($) to allow comparisons across years. The primary variables used are X14 (age), X805 (balance still owed on first mortgage), X808 (mortgage payment), X701 (homeownership), X809 (payment frequency), X5729 (income), and X507 (value of primary residence). Sample weights (X4200) were applied throughout the data.

The term “family” is defined in the SCF by examining a household unit and dividing into a primary economic unit (PEU) – the family – and everyone else in the household (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2014). The PEU is intended to be the economically dominant single person or couple (whether married or living together as partners) and all other persons in the household who are financially interdependent with that economically dominant person or couple. In this regard, the definition of families in the SCF is more comparable to the definition of households in other government surveys.

The data are analyzed in four six-year age groups beginning in 1992 and based on the age of the head of the family: 54–59, 60–65, 66–71, and 72–77-year-olds. The cohorts were then aged every six years, the same intervals that align with years that cohorts are observed in the SCF. While the SCF takes place every three years, the data are aggregated into six-year age intervals to ensure a large enough sample for appropriate inferences. In the last year of study, the oldest cohort went from being 42–47 in 1992 to 72–77 years in 2013.

Analysis

To start, I examine changes in housing debt, homeownership, and home equity by age. Table 9.1 reports the share of families without a mortgage in the various age groups. Families with a mortgage in retirement may be at greater risk of losing their homes without working or obtaining additional income above and beyond Social Security.

Table 9.1: Percent of Households with No Mortgage by Age

| 1992 | 1995 | 1998 | 2001 | 2004 | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54–59 | 41% | 42% | 42% | 42% | 41% | 35% | 37% | 39% |

| 60–65 | 56% | 53% | 55% | 57% | 54% | 47% | 46% | 48% |

| 66–71 | 75% | 72% | 70% | 68% | 69% | 61% | 59% | 59% |

| 72–77 | 90% | 82% | 83% | 83% | 80% | 76% | 67% | 70% |

The data show a consistent downward trend in the share of homeowners with a paid-off home entering retirement age. For families whose head was over age 65 (in this case, age 66–71), the share without a mortgage fell from a high of 75 percent in 1992 to 69 percent in 2004, just prior to the financial crisis. By 2007, the percentage without a mortgage had fallen to 61 percent and remained around 59 percent in 2010 and 2013. Families with a head aged 72–77 years old exhibit a similar large decline in the share of borrowers without mortgages. Older borrowers appear to have strongly contributed to the growth in borrowing during the mid-2000s. By contrast, the share of borrowers aged 54 to 59 without a mortgage has remained relatively stable at between 35 percent and 42 percent. Thus the increase in debt appears to be a result of borrowers not paying off their mortgage as they approach and enter retirement age.