The funerary monument erected in memory of Mecia Dynata offers a rare and valuable snapshot of a family that was embedded firmly in Rome’s artisanal economy. The distinguishing feature of the monument is its lengthy (if highly abbreviated) inscription, consisting of two main clauses. The first informs the reader that the monument was commissioned on behalf of Dynata by the members of her natal family and in accordance with the terms of her will:

To the Sacred Shades. To Mecia Dynata, daughter of Lucius. In accordance with her will and because of a gift specified in one of its clauses [the following people dedicated the monument]: her father Lucius Ermagoras, son of Lucius; her mother Mecia Flora, a wool-comber; her brother Lucius Mecius Rusticus, son of Lucius, a wool-worker in the quarter [of the goddess] Fors Fortuna.

The second clause details several pieces of property that Dynata bequeathed to her parents and to her brother.Footnote 1

Dynata’s inscription is notable primarily because it illustrates the complexity of the household strategies that artisans and entrepreneurs at Rome were capable of crafting for themselves and for other members of their households. By providing information about the occupations pursued by Dynata’s family members, it suggests that members of artisan households in Rome could and did take advantage of a wide range of economic opportunities that presented themselves in the urban market. Dynata’s father unfortunately chose not to name his own occupation in the inscription, but her mother and brother both seem to have pursued careers of their own: her mother Flora worked as a wool-comber (possibly in a business based in the household itself), and her brother Rusticus not only identified himself as a wool worker but also laid claim to a shop address somewhere in the vicinity of the temple of Fors Fortuna – a detail implying that he was an independent artisan in his own right. Beyond providing insight into occupations of members of Dynata’s family, the inscription also demonstrates that members of households in this particular socioeconomic stratum were capable of using complex legal instruments to manage or even reconfigure their property rights and the formal relationships that bound them together, all while maintaining strong reciprocal ties. The key detail is that Dynata possessed substantial property of her own, which she distributed to her family members according to the terms of a relatively complex will. While her use of a will to allocate property is interesting in and of itself, more significant is the fact that she held property in her own right at all. Since her father was still alive at the time of her death, one would expect that she would have fallen under his potestas, in which case she would have possessed no property rights of her own; that she instead appears to have been legally independent (sui iuris) and capable of owning property therefore indicates that she had been freed from the potestas of her father. Her father may have transferred her formally into the power of a husband by arranging for her to marry in manu, and her husband may have subsequently died, leaving her legally independent. Alternatively, her father may have legally emancipated her so that she could benefit personally from the terms of a will – probably the will of a wealthy husband, who bequeathed to her the assets that are cataloged in the second clause of the inscription, and which she herself then distributed to the members of her own natal family.Footnote 2 Since marriage in manu was mostly obsolete by the late Republic, the latter possibility is more likely, and in that sense the inscription reveals a high degree of legal literacy and sophistication in Rome’s working population.Footnote 3

By offering clues about the occupations of Dynata’s family members and about the sophistication of the legal strategies they employed, Dynata’s inscription evokes questions concerning the nature of the relationships between work, the household, and the family in Rome’s artisan economy. It also evokes questions about the extent to which artisans manipulated those relationships in navigating the seasonal and uncertain demand characteristic of urban product markets in antiquity and, by extension, about the aggregate impact exerted by individual artisans’ household strategies on the Roman world’s urban economies. The information communicated by the inscription therefore intersects nicely with recent trends in the historiography of the Roman family, which has increasingly focused on the strategies implemented by the members of individual households and on how those strategies affected the performance of the Roman economy as a whole. In particular, recent contributors to this historiography have stressed two main points. First, they have noted that households in antiquity – which tended to be conceptualized by Romans themselves as “nuclear family plus” households consisting primarily of parents, their children, and their slaves, and which functioned primarily as units of coresidence and economic cooperation – could be adaptable structures and that their members could tailor their strategies of economic production and inheritance to meet the specific demographic and economic needs of the group.Footnote 4 Second, they have also stressed that the strategies of individuals, although highly adaptable, were nevertheless constrained by various asymmetries of authority and gender that structured their relationships with other household members and created strong expectations about their roles and behavior.Footnote 5

While this work has certainly not neglected the households of working people in the Roman world’s urban environments, much of it has tended to focus primarily on the strategies of individuals from elite or peasant households. Only recently have Roman historians begun to focus explicitly on the complicated question of how household members made decisions about allocating their time and labor in urban environments.Footnote 6 For that reason, and in spite of the current trends in the historiography, we are still in the early stages of exploring both the household strategies pursued by members of the Roman world’s urban population and the potential effects that those strategies wrought on the economy as a whole. To cite just the most obvious example, the inscription of Mecia Dynata strongly implies that her brother Rusticus ran a business of his own – a detail that runs counter to the common view that artisans often employed their sons personally (a problem to which I return in much more detail below). In this chapter, I therefore seek to refine our knowledge of household strategies among urban working populations by addressing these issues more explicitly. I do so by concentrating on the roles played within artisan households by two key members of the “nuclear family plus” model of the household: sons and wives. As we shall see, the roles assigned to sons in the family economy reflect artisans’ efforts to respond to the challenges created by the Roman world’s seasonal and uncertain product markets. Wives, on the other hand, found their roles shaped strongly by preferences rooted in strong ideologies of gender, which had profound implications for the Roman world’s ability to sustain intensive economic growth after the end of the late Republic.

Roman artisans and their sons

When Richard Wall proposed his model of the adaptive family economy, stressing simply that families could be expected to “attempt to maximize their economic well-being by diversifying the employments of family members,” he broke away from an earlier strand of scholarship that conceptualized the household not just as a unit of consumption and production but also as one in which household members devoted much of their labor to a single and dominant productive enterprise – whether the cultivation of a farm or the operation of a manufacturing or retail business.Footnote 7 According to this older “family economy” model of the household, the head of a household employed its other members directly whenever possible. The family enterprise therefore gave the household much of its coherence – so much so that if individual members could not be employed within the household, they tended to leave it.Footnote 8 As applied to urban households, this model systematized a long-held view that artisans and other urban entrepreneurs naturally relied heavily on the labor of family members, especially sons.Footnote 9

Following in Wall’s footsteps, other historians of early modern Europe have shown that it was not necessarily typical for artisans and businessmen to employ their own sons. Instead, fathers were more likely to establish their sons in careers outside of the household, whether in their own line of work or in a different trade. For sons, the typical career trajectory involved an apprenticeship in the workshop of one or more artisans, followed by a period in which they worked for wages as journeymen (often in multiple establishments), and finally by establishment as master artisans in their own right, often with the help of resources they inherited from their own families or acquired through marriage. Much of the evidence supporting this view is indirect but compelling. Several studies, for example, show that family continuity was often weak among the members of any given guild or trade corporation. In spite of the fact that the membership profiles of guilds and trade corporations differed tremendously from one geographical and chronological context to the next, sons of established masters in a given trade rarely constituted a majority of newly admitted members; in most cases, they were outnumbered by the sons of artisans who belonged to other corporations. Other historians emphasize that artisans were much more likely to rely on the labor of apprentices and journeymen recruited from outside the household itself than on the labor of their own family members, even when their sons were trained in the same trade they practiced themselves.Footnote 10

These revised views of artisan households in the early modern period have not yet been taken up in detail by ancient historians, who remain influenced by the older “family economy” approach. The work of Roger Bagnall and Bruce Frier is a case in point. In their groundbreaking study of the census returns from Roman Egypt, Bagnall and Frier drew a parallel between the economic structure of the households recorded in their evidence and the structure of households based on the “family economy” model by observing that “‘inherited’ professions are not uncommon in premodern societies; the household is conceived as a single economic unit, with sons succeeding to their fathers.”Footnote 11

As Bagnall and Frier noted, however, the Egyptian census records do not necessarily support the view that sons in Roman Egypt typically worked alongside and succeeded to their fathers. There are a number of census documents recording households in which co-resident adult males (typically fathers and sons) shared the same occupation, but these must be read alongside other documents showing that adult sons could just as easily remain in their natal households even though they did not practice the same trades as their fathers. Bagnall and Frier ultimately concluded that their sample was too small to permit easy generalizations about which kind of household organization was more common than the other.Footnote 12 Additionally, there is no guarantee that co-resident males worked alongside one another even when they worked in the same trade, since one can easily imagine that sons in such households spent some or even much of their time working for wages in the shops of other artisans (and perhaps even engaging in seasonal migration to do so).

Inscriptions from the Latin West present comparable problems of interpretation. The inscriptions of professional associations point to a degree of family continuity in particular trades, since fathers and sons sometimes appear together in membership lists, and honorific inscriptions permit historians to trace the careers of multiple members of the same family who became magistrates of individual collegia.Footnote 13 Family continuity in a given trade, however, is not the same thing as family continuity in a business, and since most members of professional associations were likely men who ran their own enterprises, those fathers and sons who held contemporaneous memberships in the same association were arguably proprietors of separate workshops rather than co-workers.Footnote 14 Moreover, some funerary inscriptions either demonstrate or strongly imply that sons did not find employment in the business or workshops of their fathers. While the funerary monument dedicated to Mecia Flora offers one example, the inscription commissioned by the freedman Lucius Maelius Thamyrus is more explicit: it demonstrates that although Thamyrus himself earned his living as an artisan who manufactured metal tableware (a vascularius), his son pursued a career as a scribe in the offices of the curule aediles and quaestors.Footnote 15

When read against recent work on fathers and sons in early modern Europe, these ambiguities in our evidence encourage us to revisit the question of whether or not artisans in the Roman world regularly employed their own sons, especially if the answer has relevance for our understanding of the Roman economy’s structure. In what follows, I begin by exploring two lines of evidence that bear indirectly on this question. The first consists of the many references to apprenticeship that appear in our legal, literary, and epigraphic sources and the second of Roman funerary inscriptions commissioned by or on behalf of artisans. Together, these lines of evidence indicate that artisans and retailers in the Roman world employed their own sons infrequently, and that they generally sought instead to establish those sons in careers of their own. I then consider the factors responsible for this pattern, as well as its implications for our understanding of the Roman economy more broadly. Here, I show that the rarity with which fathers employed their own sons can be understood primarily as a product of the seasonal and uncertain demand typical in urban product markets. Unless fathers possessed especially valuable business-related capital that gave them an incentive to transmit their enterprises to their sons, seasonal and uncertain demand tended to limit their own need for regular and permanent help and to encourage them to diversify their households’ sources of income. Finally, I suggest that this pattern builds upon some of the conclusions advanced in previous chapters about market integration in the Roman Empire, namely by confirming that product and labor markets remained thin relative to those of early modern Europe even if artisans clearly did have an interest in ensuring that their sons were productively employed.

Artisans, sons, and apprenticeship

Embedded in our ancient sources is a considerable amount of information on the importance of apprenticeship as a means for transmitting craft skills from one generation to the next. By itself, this information cannot tell us whether or not it was more common for fathers to arrange apprenticeships for their sons in other workshops than to train them personally, particularly since our sources say little about sons who were trained at home. That said, this information remains significant because the early modern evidence suggests that apprenticeship can serve as a proxy indicator for the willingness of artisans and other entrepreneurs to establish sons in careers of their own. Artisans in the early modern period apprenticed their sons to other craftsmen with some frequency, whether to men who practiced different trades or to those who specialized in the same craft as they did themselves. Those who apprenticed their sons to craftsmen in different trades did so in the expectation of launching their sons on independent careers. Likewise, although some fathers who apprenticed their sons to craftsmen in their own trades undoubtedly intended to employ those sons personally once their training was complete, these seem to have been in the minority; instead, even fathers who apprenticed their sons to other artisans in the same trade often hoped that those sons would establish themselves as independent entrepreneurs or wage earners in their own right.Footnote 16 As I suggest in the following paragraphs, the ancient evidence for apprenticeship, though far from comprehensive, is at least consistent with the early modern pattern. Not only was apprenticeship widespread, it was also used to secure training for sons by fathers who operated their own enterprises, and who therefore could have trained their sons personally – perhaps as the first step in preparing those sons for careers of their own.

The strongest indication that apprenticeship was a familiar institution in the Roman world is the mention of apprentices or apprenticeship in several different categories of evidence.Footnote 17 A handful of opinions preserved in the Digest indicates that apprenticeship was common enough to attract attention from the Roman jurists, who were interested in the legal problems that arose when apprentices were mistreated or represented their instructors in transactions with clients.Footnote 18 Some of these opinions clearly reflect cases in which slaveholders contracted with artisans to have slaves instructed in a particular craft, but others just as clearly refer to freeborn apprentices. The most famous of these is Julian’s discussion of the remedies available to a father whose son had been blinded in one eye when the shoemaker to whom he had been apprenticed punished him by striking him with a last,Footnote 19 but Ulpian too may have had freeborn apprentices in mind when discussing a (possibly hypothetical) case in which a fuller left his business in the hands of several apprentices while he himself went abroad.Footnote 20

Periodic references to apprenticeship also exist in the texts of literary authors from the first two centuries CE, who – like the Roman jurists – appear to take for granted the notion that both slaves and freeborn boys were often apprenticed to artisans. Cicero mentions several apprentices who worked alongside the building contractor Cillo, whom he had hired to work on his brother’s estate near Arpinum, albeit in a context which suggests that they were slaves.Footnote 21 Vitruvius, on the other hand, believed that freeborn Romans regularly learned architecture (if poorly) as apprentices in the Augustan period; such, at any rate, seems to be the thrust of his complaint that architects no longer followed the example of the ancients, who transmitted their knowledge only to their sons or other close relatives.Footnote 22 Apprenticeship also appears in works of fiction or satire: in Petronius’ Satyricon, the freedman Echion, an artisan specializing in woolen textiles (a centonarius), contemplates having his son trained as a lawyer, an auctioneer, or a barber, and Lucian of Samosata based a significant part of one of his satires on his own brief career as a stonemason’s apprentice in his uncle’s workshop.Footnote 23

Finally, several dozen pieces of documentary evidence also refer directly to apprentices or apprenticeship. Some funerary inscriptions from the Latin West were commissioned by or on behalf of young men who had served apprenticeships in the workshops of artisans and entrepreneurs; some died before completing their training, while others outlived and then memorialized their instructors.Footnote 24 More interesting are the apprenticeship documents from Roman Egypt. About forty documents produced between the first and third centuries CE survive; they include not only notices of apprenticeship filed with municipal authorities for tax purposes but also actual apprenticeship agreements.Footnote 25 As Christel Freu has pointed out, the sheer number of surviving apprenticeship documents is itself impressive: by comparison, only about a hundred marriage contracts survive from the same period.Footnote 26 While this could simply be an accident of preservation, it may just as easily indicate that young men (and the occasional young woman) who learned craft skills normally did so as apprentices, and not in their parents’ workshops.

The demographic realities of urban living ensured that many freeborn young men would have needed to acquire craft skills through apprenticeship if they acquired them at all, for the simple reason that approximately one-third of freeborn boys in the Roman world may not have had living fathers by the time they became old enough to start learning a trade in earnest.Footnote 27 A number of the Egyptian documents drive that point home by demonstrating that a young man’s mother or guardian was often compelled to arrange his apprenticeship, presumably because his father had died.Footnote 28 That said, several pieces of evidence imply that fathers consciously chose to place their sons as apprentices in the workshops of others, even though they may have been capable of training them personally. Petronius’ characterization of the fictional Echion is an obvious example, but Julian’s discussion of the apprentice blinded by his instructor possibly fits this pattern too: at the very least, it is clear that the boy’s father arranged the apprenticeship,Footnote 29 perhaps hoping to establish his son in an independent career. Lucian’s account of his own brief apprenticeship is equally illuminating. The story is so heavily layered with sophisticated literary allusions that it is impossible to disentangle fiction or embellishment from genuine autobiographical details, but Lucian seems to have been interested in constructing a plausible depiction of family life in an artisanal or entrepreneurial household. For that reason, his portrayal of his father’s approach to the question of Lucian’s own career speaks to an outlook that was probably common among households of this type.Footnote 30 Two aspects of that portrayal deserve emphasis. First, Lucian depicts his father’s deliberations not as something exceptional, but rather as a typical family event, which featured considerable discussion between his father and various family members and friends about what occupation would be most suitable for his son. Second, Lucian attributes to his father a clear belief that apprenticeship was an important first step toward establishing Lucian in an independent career that would provide the household as a whole with additional income.Footnote 31

Unfortunately, neither Julian nor Lucian specifies whether the fathers who feature in their accounts operated their own enterprises. It is therefore not clear that we can read these anecdotes as reflections of strategies that were typical among artisans or entrepreneurs who had the option to train and employ their sons personally. Other pieces of evidence can partially dispel that ambiguity by demonstrating that artisans too may have placed their sons as apprentices in other workshops with some regularity. Echion’s deliberations about his son’s future are especially interesting, since they imply that it was not unusual for a successful artisan to consider having his son trained by another and in a different profession.Footnote 32 No less valuable are several Egyptian apprenticeship documents reflecting the arrangements made by three weavers in Oxyrhynchus on behalf of their sons or other relatives. As we saw in Chapter 2, the weaver Pausiris had at least three sons, all of whom he apprenticed to fellow weavers in Oxyrhynchus during the first century CE; he also accepted the nephew of one of these weavers as an apprentice of his own.Footnote 33 Likewise, Pausiris’ contemporary Tryphon son of Dionysios helped his mother arrange an apprenticeship for his younger brother in another weaver’s workshop, in 36 CE, and secured apprenticeships for his own two sons in the enterprises of colleagues some years later, in 54 CE and in 66 CE.Footnote 34 Although these documents say little about the intentions of these men, it is not unreasonable to believe that they, just like Lucian’s father and the fictional Echion, saw apprenticeship as a necessary step in their efforts to secure employment for young men in their charge outside of their own households.Footnote 35

The Roman occupational inscriptions and patterns of inheritance in artisan households

Although the qualitative evidence for apprenticeship in the Roman world shows that artisan fathers certainly did not feel compelled to train or employ their sons personally, on its own it cannot reveal whether it was more typical for sons to strike out in independent careers or to remain in the family workshop (or even to return to the family workshop after serving an apprenticeship elsewhere). Only quantitative evidence can be used to address these issues satisfactorily, and ultimately only the funerary inscriptions from Rome offer a sizeable-enough body of data to permit quantification, in spite of the limitations of the inscriptions as sources of evidence.

The surviving funerary inscriptions from Rome can provide a crude sense of the familial and household strategies typical among Roman artisans, albeit in a roundabout way – by generating insight into patterns of succession and inheritance in urban households. Broadly speaking, Romans not only expected that a deceased’s formal heirs would assume the primary obligation for performing the sacra or funerary rites on his or her behalf but also conceptualized the act of commemoration both as an opportunity to display their own pietas and as an important element of the sacra themselves. For that reason, even though the individuals who commissioned the tens of thousands of funerary inscriptions found within Rome itself did so for a complex cluster of reasons in which sentiment and affection obviously mattered,Footnote 36 they were often motivated just as strongly by cultural and legal expectations concerning succession. Several scholars have accordingly concluded that we can reconstruct approximate patterns of succession in Roman households by analyzing the patterns of commemoration visible in these inscriptions – that is, by assessing how frequently the deceased were commemorated by individuals belonging to one of several different categories of kin and non-kin relations.Footnote 37

Because the decisions household heads made about succession were influenced by numerous individual factors – legal, cultural, economic, and personal – those decisions need not always have been closely linked with other decisions they made about their sons’ careers. On the other hand, since it is difficult to imagine factors that would have prompted men who employed their sons in their own enterprises to name individuals other than those sons as primary heirs, we can anticipate that there was a correlation between the household strategies they pursued during their lifetimes and the dispositions they made in their final testaments. In the following pages, I explore that correlation by analyzing patterns of commemoration in those Roman funerary inscriptions in which at least one individual is identified by his or her occupation. As I demonstrate, these inscriptions provide indirect evidence that Roman entrepreneurs – particularly artisans and retailers – generally chose to establish their sons in independent careers rather than to employ them in their own businesses. They do so primarily by demonstrating that artisans and retailers were unlikely to appoint their sons as their heirs. This is true even if the freeborn are underrepresented in the inscriptions relative to freed slaves, who were perhaps more likely to subscribe to the “epigraphic habit” and to commission inscriptions than the freeborn, but less likely to leave behind grown sons when they died. As a group, the artisans in the sample were commemorated by their sons so infrequently that the patterns in the inscriptions can be explained more convincingly as the product of conscious strategies of succession than as the result of the uneven representation of freeborn and freed artisans or of demographic factors affecting the lives of freedmen. Those strategies can in turn be interpreted as an indication that artisans and retailers normally did not employ their sons personally and that they consequently had some incentive to appoint others – chiefly wives or former slaves – as their primary heirs.

Although more than 200,000 funerary inscriptions have survived from Rome of the late Republic and early Empire, only about 1,200 are inscriptions in which individuals identified either themselves or those whom they commemorated by citing specific occupational titles.Footnote 38 Furthermore, of these so-called occupational inscriptions, only a minority provides information about the social networks of independent entrepreneurs or artisans (whether freeborn or freed). Many refer instead to slaves or freedmen who remained associated with large aristocratic households and who were ultimately laid to rest within columbaria maintained by their owners or patrons.Footnote 39 These inscriptions were often commissioned by other members of the slave familiae to which the men and women they commemorate belonged, and while they therefore offer valuable information about social relationships in large, slaveholding households, they say little about social conditions in other sub-elite strata of the urban population: the rhythms of patronage and manumission in large households produced patterns of family life among their slave and freed members that differed significantly from those experienced both by the freeborn and by slaves and freedmen attached to small artisan households.Footnote 40 At the same time, few occupational inscriptions reveal more than the briefest details about the social relationships of the deceased even when they do refer to freeborn entrepreneurs or former slaves who had established businesses of their own. Some, for example, record only the deceased’s name and occupation, without revealing any information about the identity of his or her commemorators, while others list the names of two or more individuals, but neither distinguish between commemorator and deceased nor provide concrete information about the nature of the social relationships tying those individuals together.

Given these limitations, I have chosen to analyze patterns of commemoration and succession among Roman entrepreneurs by concentrating on a sample of 208 inscriptions.Footnote 41 Each of these inscriptions provides a straightforward (if selective) snapshot of the social world in which at least one individual identified by his or her occupation was embedded. Some of these inscriptions present evidence for more than a single dyadic social relationship. These include ante-mortem inscriptions, which individuals typically commissioned not just for themselves but also for other family members and for dependents entitled to share their tombs. They also include inscriptions commissioned by more than one commemorator, like the inscription dedicated to Caius Fufius Zmaragdus:

To Caius Fufius Zmaragdus, pearl-seller on the Sacred Way. [Erected under] the guidance of Fufia Galla, his wife, and of Atimetus and Abascantus, his freedmen. [They also dedicated this monument] to their freedmen and freedwomen and to their posterity.Footnote 42

Most, however, are very simple inscriptions in which the commemorator stated his or her own name along with the name of the person being memorialized and either claimed an occupational title personally or assigned one to the deceased. The inscription commissioned by Marcus Sergius Eutychus for his patron is a true outlier in the sense that Eutychus paid to have both his own occupation and that of his patron engraved on the stone: “Marcus Sergius Eutychus the wheelwright, freedman of Marcus, [set this monument up] for himself and for his patron, Marcus Sergius Philocalus the wheelwright, freedman of Marcus.”Footnote 43

I have followed the procedure employed by Richard Saller and Brent Shaw in their analysis of Roman family relations during the early Empire. Saller and Shaw approached several large samples of funerary inscriptions by tabulating the various kinds of interpersonal relationships memorialized in each inscription.Footnote 44 The inscription commissioned by Marcus Sergius Eutychus, for instance, would yield a single entry in the “freedman-to-patron” column in their table when subjected to this methodology, whereas the one commissioned jointly by Fufia Galla, Atimetus, and Abascantus would produce both a “wife-to-husband” and a “freedman-to-patron” entry. Although there are weaknesses in this approach – among other things, it can distort our view of family structure by overemphasizing selected dyadic relationships in any given household at the expense of extended family structures – the main advantage it offers is the ability to compare the commemorative pattern produced by the occupational inscriptions with the patterns Saller and Shaw extracted from their own samples.Footnote 45

In Table 4.1, I present the preliminary results of this analysis. The first panel displays the commemorative pattern produced by the occupational inscriptions. For comparative purposes, the other panels display the patterns produced by the inscriptions belonging to two of the samples studied by Saller and Shaw: those produced by members of the lower orders at Rome and those produced by members of the senatorial and equestrian orders.Footnote 46 As this table indicates, commemorations from sons to fathers are no more common in the occupational inscriptions than in the inscriptions of the Roman lower orders in general. More importantly, they are decidedly less common within the occupational inscriptions than they are in the inscriptions of the senatorial and equestrian orders. This point is significant, since if we can legitimately assume that members of the senatorial and equestrian orders tried to ensure that sons in particular would have had access to the wealth and connections necessary to maintain their social status, we would expect to see sons serving often as heirs within this particular social group.Footnote 47 Their inscriptions therefore offer a good baseline value for the frequency of son-to-father commemorations we might expect to see in a social group in which son-to-father succession was important. The comparative rarity of these kinds of commemorations in the occupational inscriptions thus offers preliminary grounds for believing that household heads in the social group from which these inscriptions originated were not often succeeded directly by their sons.

Table 4.1 Commemorative patterns

| Dedication | Occupational inscriptions | Rome: senators & equites | Rome: lower orders | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Husband | Wife | 66 | 23 | (36) | 10 | 12 | (16) | 48 | 20 | (26) | |

| Wife | Husband | 45 | 16 | (25) | 5 | 6 | (8) | 31 | 13 | (17) | |

| Total: conjugal family | 111 | 39 | (61) | 15 | 18 | (24) | 79 | 33 | (42) | ||

| Parents | Son | 4 | 1 | (2) | 6 | 7 | (10) | 24 | 10 | (13) | |

| Parents | Daughter | 0 | 0 | (0) | 1 | 1 | (2) | 6 | 3 | (3) | |

| Father | Son | 14 | 5 | (8) | 7 | 9 | (11) | 9 | 4 | (5) | |

| Father | Daughter | 10 | 3 | (5) | 3 | 4 | (5) | 6 | 3 | (3) | |

| Mother | Son | 1 | 0 | (1) | 6 | 7 | (10) | 11 | 5 | (6) | |

| Mother | Daughter | 2 | 1 | (1) | 0 | 0 | (0) | 6 | 3 | (3) | |

| Total: descending nuclear family | 31 | 11 | (17) | 23 | 28 | (37) | 62 | 26 | (33) | ||

| Son | Father | 10 | 3 | (5) | 7 | 9 | (11) | 6 | 3 | (3) | |

| Son | Mother | 4 | 1 | (2) | 2 | 2 | (3) | 13 | 5 | (7) | |

| Daughter | Father | 6 | 2 | (3) | 11 | 13 | (17) | 2 | 1 | (1) | |

| Daughter | Mother | 3 | 1 | (2) | 2 | 2 | (3) | 5 | 2 | (3) | |

| Total: ascending nuclear family | 23 | 8 | (13) | 22 | 27 | (35) | 26 | 11 | (14) | ||

| Brother | Brother | 13 | 5 | (7) | 1 | 1 | (2) | 12 | 5 | (6) | |

| Brother | Sister | 3 | 1 | (2) | 0 | 0 | (0) | 1 | 0 | (1) | |

| Sister | Brother | 2 | 1 | (1) | 2 | 2 | (3) | 3 | 1 | (2) | |

| Sister | Sister | 0 | 0 | (0) | 0 | 0 | (0) | 3 | 1 | (2) | |

| Total: siblings | 18 | 6 | (10) | 3 | 4 | (5) | 19 | 8 | (10) | ||

| Total: nuclear family | 183 | 64 | (100) | 63 | 77 | (100) | 186 | 78 | (100) | ||

| Extended family | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 11 | 5 | |||||

| Heredes | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Amici | 35 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Patron | Freedman | 21 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | ||||

| Master | Slave | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Freedman | Patron | 40 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 25 | 11 | ||||

| Slave | Master | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total: servile | 64 | 22 | 3 | 4 | 34 | 14 | |||||

| Total: relationships | 288 | 82 | 237 | ||||||||

Notes:

(a) The data for the panels labeled “Rome: senators and equites” and “Rome: lower orders” are taken from Saller and Shaw Reference Saller and Shaw1984.

(b) The figures without parentheses in the percentile columns are the proportions of all relationships in the panel represented by a particular category of relationship; those enclosed in parentheses are the proportions of nuclear family relationships represented by each particular category.

Yet even though fathers do not seem to have been succeeded by their sons in this social group as often as in senatorial and equestrian families, the social and economic factors that produced this pattern are far from self-evident. While it is tempting to suggest that artisan fathers rarely appointed sons as their heirs simply because they rarely employed them in their own businesses, two considerations raise the possibility that the small number of son-to-father commemorations in this sample was instead the product of demographic factors rooted in slavery and manumission, which may have exerted an undue influence on the epigraphic record. First, most Roman historians believe that freed slaves subscribed more heavily to the “epigraphic habit” than the freeborn and are therefore overrepresented in Rome’s funerary epigraphy. Advocates of this position generally stress that the kind of funerary display responsible for most of our inscriptions was fashionable among the freeborn only briefly during the late Republic and early Empire and chiefly among the municipal elite, but that freed slaves – who saw commemoration as a way to celebrate both their freedom and their ability to form families of their own – adopted the practice on a much larger scale. In this view, roughly 75 percent of the individuals known to us from Roman funerary inscriptions are likely to have been former slaves, even though freed slaves almost certainly made up a much smaller proportion of the city’s actual population than this figure implies.Footnote 48 Second, freed slaves as a group may have been less likely than the freeborn to form stable families and thus less likely to produce freeborn children while they were still young enough to survive until those children reached an age at which they could commemorate their parents. This was particularly true after the creation of the lex Aelia Sentia in 4 CE. Among other things, this legislation restricted the ability of slaveholders to manumit their slaves formally unless both master and slave met certain conditions, one of which stipulated that the slave was to be at least thirty years of age; to the extent that this provision encouraged slaveholders to keep slaves in bondage longer than they may have in other cases, it meant that former slaves may have started families of their own at a later age than was typical among the freeborn. Together, these factors could explain many of the characteristics of the commemorative pattern visible in the occupational inscriptions.

In fact, certain features of the occupational inscriptions can initially be interpreted as evidence that freed slaves who suffered from limitations on their ability to form families are more heavily represented in this sample than they are in the inscriptions of the Roman lower orders in general. In their original analysis of the Roman funerary inscriptions, Saller and Shaw invoked both the prevalence of former slaves in the urban population and the impact of manumission on their ability to form families as potential explanations for the relative scarcity of commemorations among specific members of the nuclear family in the epigraphy of the Roman lower orders: between children and parents, between parents and children, and between siblings.Footnote 49 With the exception of commemorations from sons to fathers – which occur with roughly the same frequency in both samples – commemorations among members of the nuclear family in each of these categories are less common in the occupational inscriptions than they are in the inscriptions of the lower orders. These differences would hardly be surprising had the population responsible for the occupational inscriptions skewed more heavily in favor of freedmen than did the populations responsible for other samples, or had freedmen in the sample been especially unlikely to leave behind grown children when they died.

Ultimately, however, it is difficult to assess these different hypotheses in any direct way, because it is often impossible to differentiate precisely between former slaves and the freeborn in any given sample of inscriptions reflecting Rome’s non-elite population. As a result, while we can generate crude estimates concerning the proportion of freed slaves in any epigraphically attested population, those estimates remain too provisional to permit us to detect all but the most obvious variations across different samples. Only a minority of those who commissioned inscriptions either employed formal indications of freed or freeborn status in their nomenclature or signaled clearly in other ways that they were freed slaves – by, for example, making explicit references to their former masters or to their fellow freedmen.Footnote 50 Moreover, although historians have argued that certain features of personal nomenclature are more likely than not to indicate that an individual was a former slave rather than a freeborn citizen, those features are at best only suggestive, not determinative. It is often thought, for instance, that most individuals who bore Greek rather than Latin cognomina were former slaves.Footnote 51 Yet, while it seems indisputable that Greek cognomina are more common than Latin cognomina among securely identified freedmen in several epigraphic samples, parents did continue to give freeborn children Greek names, sometimes in significant numbers. For that very reason, Greek cognomina may not be as reliable as indicators of freed status as is sometimes maintained.Footnote 52 Likewise, when presented with cases in which spouses shared the same nomen, historians have often concluded that both were former slaves who had been freed by the same master. This is certainly one way of explaining why spouses shared the same nomen, but it is not at all apparent that this should be the preferred explanation in any given case, since in the sample drawn from the occupational inscriptions alone, almost all of the few men who can be identified securely as freeborn Roman citizens were married to women who bore the same nomen as they did themselves. The inscription commissioned on behalf of Mecia Dynata provides a convenient example: not only did Dynata’s parents share the same nomen (Mecius / Mecia), her father was also freeborn and indicated as much in the inscription.Footnote 53 One can imagine a number of different scenarios capable of producing this kind of homonymy, including both simple coincidence or a tendency on the part of men to marry relatives, but one that deserves emphasis is the possibility that men in this particular social stratum often manumitted and married their own slaves, who necessarily would have assumed their husbands’ names when they were freed. The framers of the lex Aelia Sentia clearly believed that men regularly chose to marry their slaves, since they specifically exempted slaveholders who freed slaves in order to marry them from some of the provisions of the law that otherwise would have constrained their ability to manumit slaves formally.Footnote 54 That belief clearly reflected social realities to some extent, since several of the occupational inscriptions explicitly identify couples in which the wife had been manumitted by her husband.Footnote 55

Although these uncertainties prevent us from accurately assessing how slavery and manumission affected the commemorative patterns in the occupational inscriptions, those patterns – far from simply reflecting the potential demographic challenges encountered by freed slaves – can provide evidence that many Roman entrepreneurs consciously chose not to appoint their sons as their heirs. First, although it is true that commemorations among certain members of the nuclear family are unusually rare in the occupational inscriptions, there are grounds for concluding that this feature of the commemorative pattern exists not so much because these inscriptions skew heavily in favor of former slaves, but rather because they skew heavily in favor of adult men. Men, for instance, were much more likely than women to claim an occupational title, or to be assigned one by others, especially in those inscriptions that do not refer to slaves or former slaves who remained attached to large, aristocratic households.Footnote 56 Likewise, boys who died in or before their early teens were less likely to be given an occupational title by those who commemorated them than were those who died later in life. Although some boys in their early teens certainly do appear in our inscriptions as trained artisans, most would not have completed their apprenticeships until they were a few years older.Footnote 57 For these reasons, the occupational inscriptions inevitably fail to report certain kinds of commemorative relationships that are more prominent in the inscriptions of other social groups – those between mothers and daughters, those between parents and young children of both sexes, those between sisters – and skew instead in favor of relationships featuring adult men identified in terms of their occupation, both as commemorators and as the recipients of dedications.

Table 4.2 presents the data in a way designed to compensate for these biases, and in so doing it confirms that the demographic profile of the population represented by the occupational inscriptions does not necessarily differ dramatically from the profile of the population represented in the inscriptions of the lower orders analyzed by Saller and Shaw. In this table, I have included only those commemorative links documented in occupational inscriptions which commemorate men to whom the dedicators assigned an occupational title. It therefore emphasizes those relationships that are most likely to reflect instances in which the commemorator(s) succeeded to the estates of individual entrepreneurs. Alongside those figures, I also present corresponding subsets of the data gathered by Saller and Shaw, representing both the inscriptions of the lower orders and the senatorial and equestrian inscriptions. It is important to note here that there is only an approximate correspondence in this table between the data drawn from the occupational inscriptions and the data excerpted from the analysis of Saller and Shaw, because the tables provided by Saller and Shaw do not break down commemorative links outside the nuclear family by gender. As a result, their data for these categories undoubtedly includes commemorations that were dedicated to women rather than to men. Even with that caveat, however, Table 4.2 shows that the commemorative patterns generated by the occupational inscriptions and by the inscriptions of the lower orders do not differ from one another as dramatically as initially seemed to be the case. In particular, although differences between the two patterns remain when the data are configured in this way, commemorations from children to their fathers now appear to have been somewhat more common in the occupational inscriptions than they are in the inscriptions of the lower orders. This would hardly be the case had the population represented by the occupational inscriptions been dominated more heavily than other populations by former slaves, who may have been less likely than were the freeborn to be survived by adult children.

Table 4.2 Commemorations to adult males

| Occupational inscriptions | Rome: senators & equites | Rome: lower orders | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commemorator | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Wife | 41 | 35 | (63) | 5 | 11 | (19) | 31 | 30 | (57) |

| Son | 9 | 8 | (14) | 7 | 16 | (27) | 6 | 6 | (11) |

| Daughter | 6 | 5 | (9) | 11 | 24 | (42) | 2 | 2 | (4) |

| Brother | 7 | 6 | (11) | 1 | 2 | (4) | 12 | 11 | (22) |

| Sister | 2 | 2 | (3) | 2 | 4 | (8) | 3 | 3 | (6) |

| Total nuclear | 65 | (100) | 26 | (100) | 54 | (100) | |||

| Extended | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 10 | |||

| Heredes | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Amici | 18 | 15 | 8 | 18 | 5 | 5 | |||

| Patron | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Master | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Freedman | 26 | 23 | 3 | 7 | 25 | 24 | |||

| Total relationships | 117 | 45 | 105 | ||||||

Notes:

(a) The data for the panels labeled “Rome: senators and equites” and “Rome: lower orders” are taken from Saller and Shaw Reference Saller and Shaw1984.

(b) The figures without parentheses in the percentile columns are the proportions of all relationships in the panel represented by a particular category of relationship; those enclosed in parentheses are the proportions of nuclear family relationships represented by each particular category.

Second, a closer look at the occupational inscriptions reveals that men practicing certain occupations were far more likely than others to be commemorated by their own children. As we shall see, this pattern seems difficult to explain on demographic grounds alone, and it therefore suggests that household heads belonging to the social group reflected in these inscriptions made conscious choices about which family members would succeed to their estates. Although our data are too sparse to yield meaningful patterns of commemoration when broken down by individual occupations, they can be partially disaggregated to reflect patterns of commemoration in broad occupational categories. In Table 4.3, I summarize those inscriptions in which children both commemorated their fathers and assigned them occupational titles and group them into three principal categories on the basis of economic conditions common to individual trades or professions. The first category includes artisans and retailers. Men practicing these occupations did not necessarily possess trade-specific capital assets of high value but did often hold a substantial amount of their assets in the form of credit that they had extended to clients; they also frequently carried substantial liabilities in the form of debts that they had incurred to their own suppliers. The second includes men who provided skilled or professional services; while they too extended considerable credit to their clients, they were much less likely than artisans and retailers to be heavily indebted to suppliers. In the third category are bankers, merchants, and wholesalers. Even though many of these were no less reliant on debt and credit than were artisans and retailers, on average they may have been more wealthy than men in the latter category and therefore better able to bequeath estates of considerable value to their heirs.Footnote 58 As Table 4.3 reveals, most of the fathers commemorated by their children practiced occupations belonging to the second and third of these three categories. Of the nine fathers who were commemorated by their sons, four were merchants or wholesalers,Footnote 59 four provided professional services (two were educators, one was a professional philosopher, and the fourth a doctor),Footnote 60 and only one – an armorer or weaponsmith (armamentarius) – worked as an artisan.Footnote 61 Moreover, although inscriptions in which daughters commemorated their fathers are fewer in number, these too conform to the same general pattern: while one father commemorated by his daughter operated what was probably a retail business devoted to the sale of papyrus or writing tablets,Footnote 62 the rest worked in occupations that fell into the second and third categories enumerated above.Footnote 63

Table 4.3 Commemorations to adult males in the occupational inscriptions, by occupational category

| Artisans and retailers | Skilled and professional services | Bankers, merchants, wholesalers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commemorator | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Wife | 24 | 40 | (80) | 9 | 27 | (53) | 8 | 31 | (44) |

| Son | 1 | 2 | (3) | 4 | 12 | (24) | 4 | 15 | (22) |

| Daughter | 1 | 2 | (3) | 1 | 3 | (6) | 4 | 15 | (22) |

| Brother | 2 | 3 | (7) | 3 | 9 | (18) | 2 | 8 | (11) |

| Sister | 2 | 3 | (7) | 0 | 0 | (0) | 0 | 0 | (0) |

| Total nuclear | (100) | (100) | (100) | ||||||

| Extended | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Heredes | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Amici | 11 | 19 | 7 | 21 | 2 | 8 | |||

| Patron | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Master | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Freedman | 14 | 23 | 7 | 21 | 5 | 19 | |||

| Total relationships | 60 | 33 | 26 | ||||||

Notes:

(a) The figures without parentheses in the percentile columns are the proportions of all relationships in the panel represented by a particular category of relationship; those enclosed in parentheses are the proportions of nuclear family relationships represented by each particular category.

Since it is difficult to identify the formal legal status of most individuals in the occupational inscriptions, we cannot exclude the possibility that men who worked as artisans and retailers were simply more likely to have been freed slaves than those in other occupations. On this view, the pattern displayed in Table 4.3 would reflect nothing more than the impact exerted by slavery and manumission on their ability to leave behind adult children when they died. Yet, at the same time, it is important to stress that the limited information we possess about the legal statuses of the individuals in this sample does not provide much support for this interpretation because it does not reveal any kind of direct relationship between legal status and occupation that could have produced dramatic differences in family formation among men who worked in different kinds of professions. Table 4.4 makes this point by tabulating the legal status of adult men in the sample who were assigned occupational titles by their commemorators. As should be clear from the table itself, our data, when organized in this way, provide no real grounds for believing that former slaves were more numerous among artisans and retailers than in the other occupational groups. In fact, men who can be securely identified as freeborn represent a slightly larger proportion of the individuals in this group than is the case in the other two occupational categories, while the proportion who can be identified as former slaves is lower among artisans and retailers than it is among bankers, merchants, and wholesalers (although it is somewhat higher among artisans and retailers than it is among practitioners of skilled or professional services).

Table 4.4 Juridical status of males commemorated with occupational title, by occupational category

| Artisans and retailers | Skilled and professional services | Bankers, merchants, wholesalers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Juridical status | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Freeborn (ingenuus) | 4 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Freed slave (libertus) | 13 | 24 | 7 | 35 | 6 | 22 |

| Free, status otherwise unknown (incertus) | 36 | 68 | 12 | 60 | 20 | 74 |

| Totals | 53 | 20 | 27 | |||

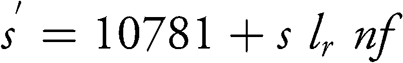

More importantly, by differentiating between occupational categories in this way, Table 4.3 emphasizes that artisans and retailers were commemorated by their sons so infrequently that this pattern is difficult to explain by invoking demographic factors alone. Tables 4.5 and 4.6 reinforce that point by modeling the proportion of freeborn fathers belonging to Rome’s upper and lower orders that would have been survived by sons old enough to serve as their heirs and commemorators when they died. These tables are based on Richard Saller’s simulation of the kinship networks in which individuals were embedded at different moments during their life courses; together, they show that men belonging to the senatorial and equestrian orders were only about 25 percent more likely to leave behind sons over the age of fourteen than were freeborn men in other social strataFootnote 64 – a difference largely attributable to the fact that men from senatorial and equestrian families both enjoyed slightly better life expectancies than average and also tended to marry for the first time at younger ages than men in other social groups.Footnote 65 By contrast, when read in conjunction with Table 4.2, Table 4.3 shows that men in the “artisans and retailers” group were far less likely to be commemorated by their sons than were those belonging to the senatorial and equestrian orders: whereas commemorations from sons to their fathers represent 27 percent of commemorations to men from members of their nuclear families in the latter group, they represent only 3 percent of commemorations to men from members of their nuclear families in the former (a ninefold variance). Demographic factors arising from slavery and manumission can only account for this variance if we make two critical and highly pessimistic assumptions: first, that more than 85 percent of the men in the “artisans and retailers” category were freedmen; second, that virtually none of these freedmen was able to produce children old enough to commemorate him when he died. If either of these assumptions were relaxed, then these factors would only account for at most two-thirds of the actual variance visible in the inscriptions. Moreover, under what could plausibly be characterized as a more realistic set of assumptions – that roughly 75 percent of the artisans and retailers commemorated in the inscriptions were former slaves and that perhaps a quarter of these were able to marry at a young-enough age to produce freeborn and legitimate children at roughly the same rate as freeborn entrepreneurs – demographic factors would only account for about a third of the observed variance.Footnote 66

Table 4.5 Deceased fathers with surviving sons, freeborn lower orders

| Father’s age | Q(x) | L(x) | Proportion with living sons | Son’s mean age | Fathers deceased, no son older than 14 | Fathers deceased, sons older than 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.08565 | 42,231 | 3,617 | |||

| 30 | 0.09654 | 38,614 | 0.16 | 0.9 | 3,728 | |

| 35 | 0.10541 | 34,886 | 0.51 | 2.7 | 3,677 | |

| 40 | 0.11227 | 31,208 | 0.65 | 5.4 | 3,503 | |

| 45 | 0.11967 | 27,705 | 0.67 | 8.8 | 3,316 | |

| 50 | 0.15285 | 24,389 | 0.69 | 12.4 | 3,728 | |

| 55 | 0.19116 | 20,661 | 0.69 | 16 | 1,224 | 2,725 |

| 60 | 0.27149 | 16,712 | 0.68 | 19.5 | 1,452 | 3,085 |

| 65 | 0.34835 | 12,175 | 0.65 | 23.7 | 1,588 | 2,653 |

| 70 | 0.47131 | 7,934 | 0.62 | 28.4 | 1,421 | 2,318 |

| Totals: | 27,254 | 10,781 | ||||

| (28.34%) |

Notes:

Q(x) represents an individual’s probability of dying before reaching the next age bracket;

L(x) represents the notional number of individuals from a putative birth cohort of 100,000 people still alive at a given age x.

Table 4.6 Deceased fathers with surviving sons, senatorial and equestrian orders

| Father’s age | Q(x) | L(x) | Proportion with living sons | Son’s mean age | Fathers deceased, no son older than 14 | Fathers deceased, son older than 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0.06551 | 53,037 | 0.15 | 1 | 3,474 | |

| 30 | 0.07393 | 49,563 | 0.49 | 3.1 | 3,664 | |

| 35 | 0.08112 | 45,899 | 0.58 | 6.2 | 3,724 | |

| 40 | 0.08725 | 42,175 | 0.59 | 10.3 | 3,679 | |

| 45 | 0.09462 | 38,496 | 0.58 | 14.9 | 1,530 | 2,113 |

| 50 | 0.12200 | 34,853 | 0.57 | 19.8 | 1,828 | 2,424 |

| 55 | 0.15472 | 30,601 | 0.55 | 24.7 | 2,130 | 2,604 |

| 60 | 0.22153 | 25,867 | 0.52 | 29.7 | 2,750 | 2,980 |

| 65 | 0.29119 | 20,137 | 0.5 | 34.6 | 2,932 | 2,932 |

| 70 | 0.40306 | 14,273 | 0.47 | 39.5 | 3,049 | 2,704 |

| Totals: | 28,760 | 15,757 | ||||

| (35.40%) |

Notes:

Q(x) represents an individual’s probability of dying before reaching the next age bracket;

L(x) represents the notional number of individuals from a putative birth cohort of 100,000 people still alive at a given age x.

Succession in artisan households

As rough as these figures are, they suggest that artisans and retailers intentionally passed over their sons as heirs, particularly when the rate at which artisans were commemorated by their sons is compared to the rates at which other men in Rome’s working population or men in Rome’s senatorial and equestrian orders were commemorated by theirs. Yet although the occupational inscriptions provide convincing evidence that Roman artisans and retailers did not normally name their sons as heirs, they unfortunately offer no direct insight into why this was the case. Nor, for that matter, do any of the other kinds of evidence that occasionally offer information about the business and family strategies of Roman entrepreneurs. For that reason, any explanation for this pattern will necessarily be speculative.

That said, because a father’s occupation seems to have strongly affected whether or not he chose to name his son as his heir, there are good reasons to suspect that Roman entrepreneurs based their decisions about succession and inheritance on the degree to which they did or did not integrate those sons into their own businesses. In the remainder of this section, I pursue this possibility in more detail by arguing that the rarity of son-to-father commemorations in the inscriptions of artisans and retailers can be read as indirect evidence that entrepreneurs in these trades were unlikely to employ their sons in their own businesses. More specifically, I suggest that because artisans and retailers were particularly likely to find themselves deeply embedded in networks of credit, on which the viability of their businesses often depended, they had strong incentives to appoint as legal heirs individuals who were capable of sustaining both their enterprises and their credit networks, even if in practice they distributed much of their assets to other beneficiaries in the form of legacies. The fact that they rarely appointed their sons as their heirs may therefore indicate that they tended to establish those sons in independent careers rather than to employ them personally and that their sons were typically not as capable of assuming control of their businesses as were other potential heirs. Those other potential heirs included freedmen and also wives, who could certainly manage a business on their own if they also retained access to the labor of skilled slaves or freedmen.

I begin by noting that historians of both the ancient and early modern worlds sometimes suggest that sons born to fathers with few material and financial assets were especially likely to leave their natal households, and often the communities in which they were raised. According to this argument, because sons in such households had only limited prospects for receiving a substantial inheritance, they often chose to pursue better opportunities elsewhere, and in many cases severed connections with their natal households in the process.Footnote 67 Since artisans and retailers in antiquity – like those in the early modern period – may have accumulated less wealth, on average, than men who pursued other occupations, it is tempting to invoke family fragmentation generated by this kind of process to explain why the rate of son-to-father succession among retailers and artisans in Rome was so much lower than it was among men belonging to other occupational categories.Footnote 68 Yet there are reasons to doubt that this model offers a convincing explanation of the commemorative pattern we see in the inscriptions of Roman artisans and retailers. For one thing, many of the artisans and retailers commemorated in the occupational inscriptions owned one or more slaves; that fact alone implies that most of the men named in these inscriptions belonged to the wealthier strata of the working population and that they were consequently capable of transmitting inheritances of at least some substance to potential heirs.Footnote 69 Additionally, even poorer households in Rome itself were probably less likely than those in smaller regional centers to fragment in ways that would have prompted sons to move away from their home towns, because the metropolis offered more economic opportunities than did other cities and towns in Italy and in the Mediterranean more broadly.Footnote 70 For both of these reasons, even sons who established households of their own in Rome were more likely than not to maintain close contact with their families and to remain available to serve as heirs. Together, these observations suggest that we should look for an explanation for the scarcity of son-to-father commemorations among artisans and retailers by identifying factors specific to these kinds of businesses that were capable of prompting men in these trades to name individuals other than their sons as heirs.

The extent to which artisans and retailers relied on credit offers just such an explanation, since entrepreneurs in these trades depended heavily on credit as both debtors and creditors, and thus had strong incentives to ensure that their heirs were capable of sustaining their credit networks. Credit was a ubiquitous feature of the Roman urban economy, and artisans and retailers in particular were probably embedded deeply in complicated networks of obligations. By way of comparison, in the early modern period artisans and retailers not only extended substantial amounts of credit to clients but also depended heavily themselves on credit advanced to them by their suppliers and subcontractors. Broadly speaking, many early modern artisans and retailers tended to carry trade-specific liabilities amounting to roughly one-quarter of the value of their gross assets at any given time, and likewise held one-third or more of their own assets in the form of credit that they had extended to their own clients.Footnote 71 Although our evidence does not permit us to assess the portfolios of typical Roman artisans and retailers in a comparable amount of detail, there is no reason to believe that they were any less dependent than their early modern counterparts on relationships of credit. As I have noted in other chapters, there are indications in our sources that artisans and retailers in antiquity relied heavily on credit and that the magnitude of both their trade-related debts and their accounts receivable did not differ dramatically in magnitude from what was typical in later periods. This is certainly the implication of the jurists’ commentary on the actio tributoria, which provided a remedy to creditors of businesses operated by slaves by allowing them to demand that a slave’s owner liquidate the peculium of a slave who became insolvent.Footnote 72 Part of what set the actio tributoria apart from the actio de peculio was the fact that a successful claimant who sued under the former procedure was required to guarantee that if other creditors launched similar lawsuits against the slave (whose peculium may have been entirely depleted by the initial action), he would grant them pro rata payments from his own settlement.Footnote 73 In that sense, it reflects an awareness on the part of the praetor who framed it that a slave-run business was likely to have multiple creditors and leaves little doubt that slaves who operated businesses regularly incurred substantial trade-related debts to numerous different parties. Ulpian’s commentary also indicates that slaves often held equally substantial assets in the form of credit that they had extended to regular customers: Ulpian notes that sums owed to a slave by his customers were to be counted among his assets (and credited to his peculium by his owner) if his creditors pressed for liquidation.Footnote 74 A case discussed by the jurist Papinian complements Ulpian’s observations by showing that both the debts and credits generated by such a business could easily be substantial enough to become the focus of a legal dispute among the heirs and other beneficiaries of an estate: Papinian seems to have been asked to deliver a ruling on whether or not a legacy consisting of a purple-seller’s shop and its slave managers included not just the capital set aside to buy additional stock but also the outstanding debts and the accounts receivable associated with the operation of the business.Footnote 75 Finally, it is worth noting that although much of the legal evidence pertains to slave-run businesses, free artisans were no less likely to depend on credit, and snippets of evidence do refer to them as providers of shop credit and as consumers of credit provided to them by their own suppliers.Footnote 76

Just as importantly, because the Romans practiced a system of universal succession, artisans and retailers had distinct incentives to appoint heirs capable of carrying on their enterprises, even if in doing so they found it necessary to disinherit their sons formally (which did not, of course, preclude them from awarding those sons generous legacies). The principle of universal succession meant that an individual’s legal heirs acquired not only his or her assets but also his or her liabilities. As a result, the heirs of an artisan or retailer effectively succeeded to a complex cluster of obligations and claims linking them to the former clients and suppliers of the testator, both of whom potentially numbered in the dozens.Footnote 77 In these circumstances, heirs who could sustain the businesses of the deceased were not just more likely than those who could not to preserve the estate’s full value, they were also less likely to perceive succession to the estate and its liabilities as a burden that they might reject. First, heirs who could keep an enterprise viable would have been better equipped than others to manage the difficult process of both honoring the testator’s business obligations and realizing the full value of the assets held as accounts receivable. They could secure flexible terms of payment from the testator’s creditors, who might have been more interested in maintaining an ongoing business relationship with a testator’s successors than in pressing for an immediate settlement of their outstanding claims. They also arguably enjoyed better prospects for calling in debts of their own than did heirs who could not maintain the business, simply because they could threaten to withdraw further shop credit from clients who did not make regular payments against their accounts. Second, heirs capable of sustaining a business were likely to see the need to manage the testator’s credit network not as a burden but as an opportunity to appropriate that network for their own purposes. After all, those who succeeded in doing so could greatly enhance their own businesses’ prospects, particularly if they had not yet been able to build extensive networks of their own. This would have been true especially in the case of heirs who had not yet been able to gain entry into a professional collegium, in which members cultivated reputation-based relationships not only with suppliers and subcontractors but also with potential clients seeking to let out work of their own. Testators could therefore feel confident that heirs capable of carrying on the business would be satisfied with portions of the inheritance that ultimately may not have consisted of much more than claims to outstanding accounts receivable once an estate’s debts were cleared.Footnote 78

For artisans and retailers who chose not to appoint sons as their primary heirs, wives and freed slaves were the most obvious alternatives. Both had at least some of the skills necessary to maintain an artisan’s or retailer’s business, and both potentially had their own incentives for accepting inheritances that may have been burdened not just by outstanding accounts payable and receivable but also by legacies allocated to other beneficiaries (such as the testator’s children). As far as the skills necessary to sustain a business were concerned, slaves and freedmen often found themselves in a strong position, because many had been acquired and trained by masters intent on employing them directly in their enterprises;Footnote 79 they were therefore well qualified to step into new roles as proprietors of ongoing concerns, provided they were given access to the necessary capital. Wives were somewhat disadvantaged in this respect, since – as I argue in more detail in Chapter 4– they often had few opportunities to acquire technical skills pertaining to the production side of artisanal businesses. Nonetheless, in practical terms, many women did help manage their husbands’ businesses and could keep an inherited concern viable if their husbands assigned them either ownership of skilled slaves or control over the outstanding labor services (operae) of skilled freedmen.Footnote 80 Wives and freedmen in this position were also especially likely to see the opportunity to gain access to a testator’s credit networks as a net benefit, even if they were required to pay out substantial legacies in addition to discharging the testator’s debts. This was so because both women and freed slaves could otherwise find it difficult to create networks of their own. Freed slaves were not always able to expand their own businesses quickly, especially when they had been required to discharge operae on behalf of their patrons for several years after their manumission. Women, on the other hand, found it difficult to secure membership in professional associations, and thus access to the networking opportunities such membership conferred; any links with clients and suppliers they inherited from their husbands therefore would have been particularly valuable.Footnote 81

From this perspective, it is significant that the low incidence of son-to-father commemorations in inscriptions dedicated to artisans and retailers is complemented by relatively high numbers of commemorations from wives to husbands and from freedmen to patrons. This pattern is most noticeable in the case of wife-to-husband commemorations, which are particularly prominent among dedications to male artisans and retailers – they constitute 40 percent of this sample but no more than 30 percent in the samples drawn from the epigraphy of other occupational groups listed in Table 4.3. Freedmen too are more visible as commemorators in inscriptions dedicated to artisans and retailers than they are in other inscriptions. At 23 percent, the rate at which freedmen commemorated male patrons who were artisans or retailers is at least two to three percentage points higher than the rate at which freedmen commemorated patrons who pursued other occupations, and it would probably be higher than the rate at which they commemorated patrons in the lower orders in general (Table 4.2) if we could fully compensate for gender and age biases in the data provided by Saller and Shaw. These figures suggest that when artisans and retailers chose to pass over sons as formal heirs, they did in fact turn to wives and freedmen. This is readily comprehensible if we conclude not only that wives and freedmen were capable of sustaining businesses that they inherited from entrepreneurs in these trades but also that artisans and retailers typically chose to establish their sons in independent careers rather than to employ them in their own enterprises.

Urban demand and artisans’ familial strategies

Although the occupational inscriptions show that artisans and retailers in the Roman world rarely employed their own sons, they offer little to no direct evidence about the considerations motivating this behavior, nor about how those considerations were influenced by the broader economic environment in which artisans and retailers were embedded. In the following paragraphs, I explore these issues in more detail. As I show, there are reasons to believe that the decisions artisans and retailers made about their sons were driven primarily by the seasonal and uncertain demand characteristic of urban product markets in the Roman world. Because the nature of that demand ensured that their own requirements for regular and permanent help were often limited, most artisans could not keep sons productively employed in their own enterprises and saw advantages in diversifying their household income streams by encouraging their sons to work outside of the home – whether by working for wages or (ideally) by establishing themselves in workshops of their own.