On the morning of 14 December 1928, 688 hajj pilgrims lined up in Batavia’s port of Tanjung Priok waiting to board NSMO’s SS Melampus, which – over the course of two to three weeks depending on the weather – would transport them to Jeddah for the start of the 1928–29 hajj season.Footnote 2 At 9:00 am, shaykhs or pilgrim brokers who worked together with Kongsi Tiga’s agents toured the ship and marked out areas for pilgrims assigned to their care for the entirety of the voyage. Pilgrims were each given a number directing them to their assigned space below deck and received by their assigned shaykhs, who escorted them to the living quarters they would occupy for the coming weeks. Joining 105 others already onboard who had embarked in Surabaya and Semarang, the spaces below deck were quickly filled: each pilgrim was entitled to 1.5 square meters (16 square feet) in a space at least 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) in height.Footnote 3 After unpacking the few belongings deemed “essential” for the voyage – which could not exceed 0.3 square meters (3.2 square feet) of deck space per person – the remaining luggage was registered, labeled, and stowed away for the duration of the trip. By1:00 pm everyone was settled and medical inspection and document verification began.Footnote 4

Pilgrims were led to a room in groups of ten, where they were met by the ships’ doctors, Harbor Master (Havenmeester), NSMO’s shipping agent and staff, and a group of nurses. After being divided into men and women, the nurses rolled up the pilgrims’ sleeves and sanitized their upper arms. A male doctor in the case of the men and both a female and male doctor in the case of the women, administered inoculations against typhoid fever, cholera, and smallpox – obligatory precautions for all pilgrims embarking from colonial Indonesian ports after 1926. A vaccination official recorded the inoculation and stamped each pilgrim’s passport. The pilgrims were then led to a long bench, where the vaccinations were given time to soak in and dry; they sat under the watchful eyes of an inspector who ensured pilgrims did not rub or touch their upper arms. The pilgrims continued on to passport control, where each pilgrim was required to show their travel pass (reispas) obtained from local government authorities prior to the journey. One by one, tickets and passports were carefully reviewed and approved. The entire process was completed by 4:00pm, when the ship finally departed for Jeddah.Footnote 5

For many men, women, and children on SS Melampus this was their first time leaving Southeast Asia and they traveled on a ship filled with hundreds of fellow passengers, all sharing a confined space at sea. Hajjis’ intimate exposure to a varied population onboard, all nevertheless united in their religious duty to fulfill the fifth pillar of Islam, introduced them to new experiences, identities, and ideas. This exposure was further intensified upon their arrival in the Middle East, where thousands of hajjis from diverse geographic, ethnic, and economic backgrounds converged, including Muslims free from European colonial rule and others active in nationalist struggles against imperialism in other European colonies. In the eyes of the Dutch colonial authorities, the incorporation of Indonesians into such a concentrated and unpredictable group of Muslims was troubling.

Both the Dutch colonial administration and Kongsi Tiga assumed hajjis could not be trusted to withstand the influence of subversive people and ideas they might encounter while abroad and feared returning hajjis might contaminate colonial Indonesia by spreading subversive political ideas learned abroad. Hajjis were considered simultaneously vulnerable to and complicit in the spread of pan-Islamic, anticolonial, and nationalist ideologies, which the Dutch suspected were circulating freely across hajj maritime networks. Controlling hajj networks was, therefore, necessary not only for practical and economic reasons, but also to maintain Dutch political authority within colonial Indonesia and both the Dutch colonial government and Kongsi Tiga worked together to police hajj maritime networks. As the pilgrims on SS Melampus experienced even before leaving Tanjung Priok, hajj ships were highly regulated and policed spaces.Footnote 6 Kongsi Tiga safeguarded Dutch colonial hegemony across global maritime networks by regulating hajji behavior onboard, policing interactions between passengers, and managing onboard space according to imperial hierarchies of race, class, and gender. The transoceanic mobility of pilgrims during the interwar period was particularly threatening to Dutch authorities and controlling Kongsi Tiga ships, therefore, became a fundamental aspect of pilgrim transport.

The Hajj Pilgrim Ordinance of 1922

Throughout much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Dutch colonial authorities viewed Indonesian Muslims with suspicion and considered the hajj a possible threat to Dutch power.Footnote 7 Some in the Dutch administration – most notably professor of Arabic at Leiden University and government advisor Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje – became highly knowledgeable in Islamic language, society, and culture, promoting religious freedom for Indonesian Muslims and, if somewhat counterproductively, arguing against colonial control and interference with the hajj and the Indonesian or Jawa community living in Mecca. But for most in the administration, the hajj continued to be seen as a nuisance and its political undertones were questioned.Footnote 8 This distrust and underlying disapproval of Islam made the pilgrimage more difficult for hajjis and prohibitive travel regulations were established in 1825, 1831, and 1859.Footnote 9 The transition to steamshipping and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 proved these travel restrictions largely toothless as hundreds – and by the interwar period tens of thousands – of Indonesian pilgrims traveled by ship to the Middle East each year. Despite these growing numbers, Dutch shipowners were slow to make serious improvements on their pilgrim fleets. Beginning in the 1890s, the colonial administration’s attempts to increase regulations on safety and standards within pilgrim shipping – reflective of the Ethical Policy’s ideals – were not routinely followed or enforced and most substantial changes within hajj transport were only significantly codified after World War I.Footnote 10

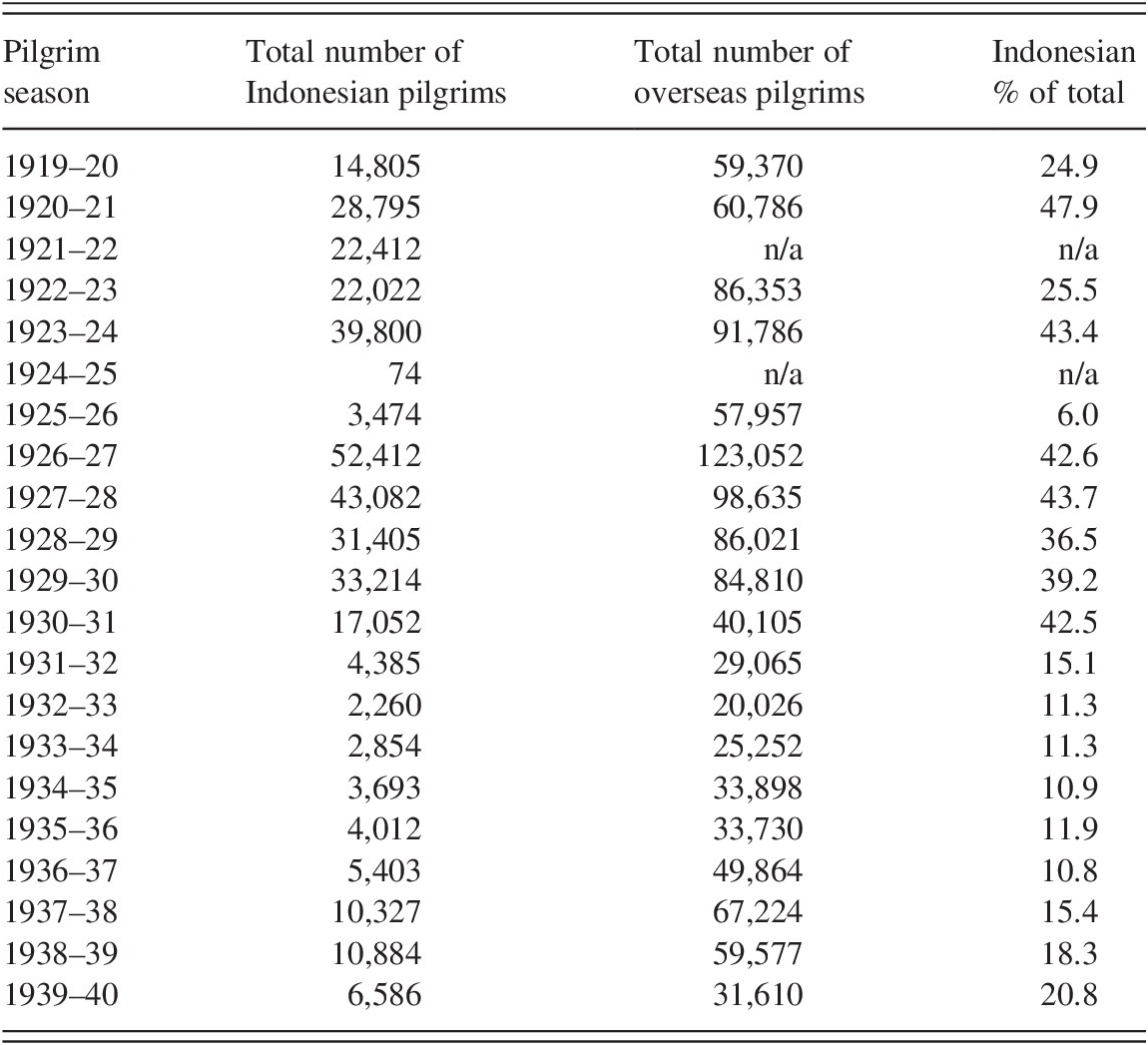

Table 1.1 shows that between 1919 and 1940, approximately 359,000 Indonesians made the hajj – comprising 31.5 percent of all overseas pilgrims arriving in the Hejaz – and the majority of these passengers traveled on Kongsi Tiga ships. SMN and RL ships departed from the ports of Makassar in Sulawesi, Surabaya and Tanjung Priok (Batavia) in Java, Emmahaven (today’s Teluk Bayur in Padang), Palembang and Belawan (Medan) in Sumatra, and Sabang off the tip of Aceh, with KPM connecting the additional ports of Semarang in Java, and Borneo’s Pontianak and Banjarmasin. On the return trip, pilgrims could only disembark at the ports of Tanjung Priok and Sabang and were responsible for arranging return transportation to their home ports.Footnote 11 NSMO ships, meanwhile, only departed from Emmahaven and Tanjung Priok before heading across the Indian Ocean towards the Red Sea and eventually on to Liverpool and Amsterdam.Footnote 12 Splitting this traffic equally, the three companies dominated Southeast Asian hajj shipping under the Kongsi Tiga flag.Footnote 13 Kongsi Tiga ships were not built specifically for pilgrim transport, but were used most of the year as regular cargo ships. With a few adjustments, they were adapted for pilgrim transport only during the hajj season, which changed each year according to the lunar calendar. The ability of the companies to make slight adjustments to already existing ships meant hajj transport was extremely lucrative for all three Kongsi Tiga companies, earning the pool around 90 million guilders in ticket sales between 1919 and 1940.Footnote 14

Table 1.1 Hajj pilgrims from colonial Indonesia, 1919–40

| Pilgrim season | Total number of Indonesian pilgrims | Total number of overseas pilgrims | Indonesian % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1919–20 | 14,805 | 59,370 | 24.9 |

| 1920–21 | 28,795 | 60,786 | 47.9 |

| 1921–22 | 22,412 | n/a | n/a |

| 1922–23 | 22,022 | 86,353 | 25.5 |

| 1923–24 | 39,800 | 91,786 | 43.4 |

| 1924–25 | 74 | n/a | n/a |

| 1925–26 | 3,474 | 57,957 | 6.0 |

| 1926–27 | 52,412 | 123,052 | 42.6 |

| 1927–28 | 43,082 | 98,635 | 43.7 |

| 1928–29 | 31,405 | 86,021 | 36.5 |

| 1929–30 | 33,214 | 84,810 | 39.2 |

| 1930–31 | 17,052 | 40,105 | 42.5 |

| 1931–32 | 4,385 | 29,065 | 15.1 |

| 1932–33 | 2,260 | 20,026 | 11.3 |

| 1933–34 | 2,854 | 25,252 | 11.3 |

| 1934–35 | 3,693 | 33,898 | 10.9 |

| 1935–36 | 4,012 | 33,730 | 11.9 |

| 1936–37 | 5,403 | 49,864 | 10.8 |

| 1937–38 | 10,327 | 67,224 | 15.4 |

| 1938–39 | 10,884 | 59,577 | 18.3 |

| 1939–40 | 6,586 | 31,610 | 20.8 |

Following the difficulties of hajj travel during World War I, the early 1920s saw a surge in pilgrim traffic, largely consisting of members of the urban lower classes and elite members of the peasantry.Footnote 15 Each year between 1927 and 1940, 65–69 percent of pilgrims on Kongsi Tiga ships were men, 27–33 percent were women, and 2–8 percent were children under the age of twelve.Footnote 16 Many hajjis began their journey with limited funds and most had saved for long periods of their lives in order to make the journey. Others relied on the combined savings of entire communities to help finance their pilgrimages. In return, financial supporters in colonial Indonesia expected returning hajjis to contribute culturally, politically, and spiritually to their communities. Hajjis returned to Southeast Asia as respected religious figures – recognizable by their new titles and attire – and often became religious leaders and teachers within their local communities. Yet monetary reserves of pilgrims – often accrued over a lifetime – were quickly dissipated, sometimes even before arriving in Jeddah. Additionally, in 1922 the sale of one-way tickets was banned and all pilgrims were legally required to purchase round-trip tickets up-front and in cash. While the high cost of these return tickets put the hajj out of reach for some, the colonial administration argued the measure was needed to ensure the safe return of pilgrims who otherwise might run out of funds while on hajj and be forced into unfair work contracts or even slavery in order to pay their return fare to Southeast Asia.Footnote 17 This change in ticketing was criticized by many in colonial Indonesia who claimed that rather than ensuring the safe return of pilgrims as the administration and Kongsi Tiga claimed, the regulation primarily served the economic interests of Kongsi Tiga.Footnote 18

The ending of one-way tickets was part of a broader restructuring of pilgrim transport ratified in the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance (Pelgrims Ordonnantie). Recognizing the need for better regulations following high pilgrim mortality rates during the 1920–21 season, Kongsi Tiga helped the Dutch government draft the new Pilgrims Ordinance to regulate all aspects of hajj transport. The new regulations standardized food, health, space, safety, and hygiene on Dutch pilgrim ships, required all agents selling pilgrim fares for Kongsi Tiga to be licensed by the government, and granted the Trio a total monopoly over hajj transport to and from colonial Indonesia.Footnote 19 In addition to the spaces reserved for pilgrims below deck, the ship was now obligated to provide at least 0.56 square meters (1.8 square feet) per pilgrim on the upper deck, which was to remain free from any encumbrances to allow pilgrims respite from the stuffy and crowded conditions below deck. The upper deck also housed the ship’s temporary hospitals, shower baths, latrines, and lifesaving devices. Yet pilgrims were forced onto the upper deck each day while the lower decks were cleaned and passengers on the SS Melampus, for example, were hustled onto the bow of the ship every morning after breakfast. After the stern and holds were checked for any remaining sick pilgrims or others lagging behind, the holds were sanitized with a sprinkling of carbolic acid.Footnote 20 Onboard sanitation also adhered to international sanitary regulations including the 1912 (ratified in 1920) and 1926 International Sanitary Conventions agreed in Paris that sought to stop the global spread of diseases through increased port sanitation and quarantine requirements.Footnote 21

While the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance did much to standardize conditions on Dutch pilgrim ships, it also demanded that detailed administrative procedures be followed throughout the voyage. Each ship was required to travel with four documents; a pilgrims certificate, passenger list, pilgrims list, and ship journal. The pilgrims certificate contained detailed information: the name of the ship; owner of the ship; names of the captain and doctor onboard; the flag under which the ship sailed; identification of the rooms in which the steerage class passengers would be transported; the largest number of passengers each room could hold; the number of places available onboard for higher-class passengers; the amount of space available on deck for steerage passengers in square meters; the largest number of passengers that could be transported at the same time; a list of the life-saving devices onboard; and specifications of the ship’s lighting, ventilation, and store of provisions. Once the owner, captain, or ship’s agent recorded this information, it was presented to the Harbor Master at the port of departure at least three days before embarkation and a ƒ300 fee was paid to the harbor authorities. The ship’s captain and physician then inspected the vessel, verifying the submitted information’s accuracy, and the ship was granted a pilgrim certificate, assuring – in theory – the ship’s adherence to the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance in terms of space and onboard provisions.Footnote 22

The ship’s owner, captain, or agent also created a passenger list and pilgrims list including information on all passengers departing from colonial Indonesian ports and arriving anywhere in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, or Arabian Sea. The passenger list included the following information for each passenger: name, sex, ethnicity, class of accommodation onboard (either steerage or a cabin passenger), whether the passenger was a pilgrim making the hajj or another category of passenger, and their assigned hold space below deck. These lists were submitted in duplicate at least twenty-four hours in advance of departure to the Harbor Master, who inspected and approved them. Copies of the final passenger list and pilgrim certificate were left with the port authorities at the last embarkation port in colonial Indonesia, while additional copies were deposited at the Dutch Consulate in Jeddah upon the ship’s arrival. The ship’s journal recorded events onboard, including any disciplinary actions taken by the captain and the number of pilgrim who died en route.

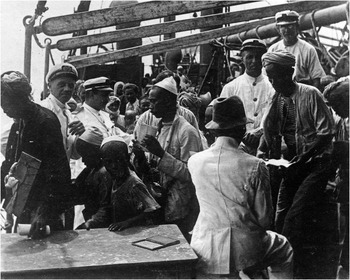

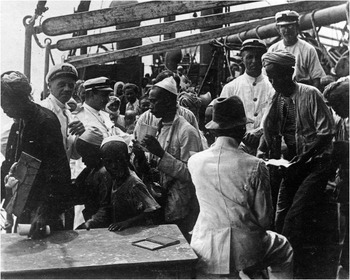

Additionally, pilgrims were required to obtain an increasing complex set of travel documents along with their tickets. As seen on the SS Melampus, and shown in Figure 1.1, each pilgrim was required to obtain a reispas from local authorities, which was stamped by the havenmeester prior to the pilgrim ship’s departure. The travel pass was stamped again by the Dutch Consulate after arrival in Jeddah, when a tearable strip with the traveler’s information was removed and kept in the consulate’s records. At the end of the pilgrimage, the travel pass was stamped a third time prior to the ship’s departure. Finally, preferably within seven days, but definitely not more than two months, of one’s arrival in colonial Indonesia, each pilgrim was required to hand in their stamped travel pass to the same local authority that issued it, to ensure those claiming hajji status had actually completed the pilgrimage. Failure to comply with these regulations could result in a ƒ100 fine. These records ensured adherence to the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance while also contributing to the colonial surveillance project, which escalated during this period.

Figure 1.1 Passport control on a Dutch pilgrim ship, c. 1910–40.

Dutch suspicions of hajjis increased dramatically after the communist uprisings of 1926–27. The Dutch government assumed that many communist agitators escaped incarceration by fleeing to Mecca under the guise of a hajji, which explained the large number of hajji passengers between 1926 and 1930.Footnote 23 In reality, Kongsi Tiga had suspended nearly all its pilgrim transport during the 1924–25 and 1925–26 hajj seasons due to the political unrest in Saudi Arabia. This caused a backlog of pilgrims eager to travel to the Middle East, which – combined with improving economic conditions in colonial Indonesia, safer pilgrimage conditions under Ibn Saud’s rule, and the fact 1927 was a hajj akbar, or greater hajj, that increased the pilgrimage’s merit – resulted in an enormous increase in pilgrims during the late 1920s.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, hajjis traveling to and from the Middle East became prime suspects in the transmission of subversive politics between pan-Islamic and anticolonial movements in the Middle East and political agitators and groups such as the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) in Southeast Asia.Footnote 25 In order to counteract the threat of further anticolonial unrest, the Dutch administration increased its surveillance over hajjis and enlisted the full support and cooperation of Kongsi Tiga.Footnote 26 As one official remarked, the colonial authorities needed to “hold the reigns tight, as punishment” after the uprisings.Footnote 27 In 1928, the administration urged local authorities collecting travel passes of returning hajjis to use it as an opportunity to keep control over returning hajjis, especially in regard to revolutionaries who might be among them.Footnote 28

The 1926–27 uprisings marked a turning point in Dutch colonial policing of the hajj, with close monitoring of the international movements of Muslim colonial subjects – especially those suspected of participating in subversive political activities, including hajjis importing pan-Islamic ideology from abroad. The hajj was an important site of state surveillance, reflected in the PID and ARD’s heightened concerns over the “Nationalist-Muslim Movement” above all other groups under surveillance.Footnote 29 Despite this escalation, in reality the interwar period saw little violence or resistance centered on Islam or pan-Islamic ideology within colonial Indonesia. Nevertheless, the voluminous records collected on each Kongsi Tiga ship helped inform this imperial securitization project. The amount of regulation on hajj ships reflected overlapping concerns of the Dutch colonial administration and Kongsi Tiga: maritime sanitation and the wellbeing of pilgrims elicited carefully recorded information about the ship and its passengers.

Containing the “Arab” Threat at Sea

The collection of such detailed information helped Kongsi Tiga identify those onboard who did not fit the definition of “ordinary” pilgrim. The majority of “others” onboard consisted of “Arab” passengers – a blanket term used by the Trio to describe Hadramis traveling to and from the Middle East and Meccan shaykhs working as pilgrim brokers in colonial Indonesia. According to the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance, a pilgrim was any “Muslim passenger, regardless of sex or age, traveling to or from the Hedjaz [Hejaz] for pilgrimage.”Footnote 30 The Trio criticized Arab passengers, who were largely merchants and agents rather than pilgrims, accusing them of unjustly profiting from the special arrangements made specifically for pilgrims and thus traveling for “next to nothing.”Footnote 31 Further, Arabs were accused of manipulating and abusing the ticketing system by using the tickets of deceased pilgrims rather than purchasing their own fares.Footnote 32 For the Dutch shipping companies, both groups represented a toxic element to the peace and order (rust en orde) implemented at sea through Kongsi Tiga’s extensive rules and regulations onboard. They were viewed as undesirable influences, capable of swaying the attitudes and opinions of Indonesian pilgrims. To counteract their influence, Kongsi Tiga used segregation as a tool to prevent what they considered to be a dangerous mixing of people onboard.Footnote 33

Of greatest concern were Hadrami Arabs – whose political and religious influence was feared by Kongsi Tiga. Together with the physical segregation of these passengers away from ordinary pilgrims, Dutch captains and officers were tasked with monitoring suspicious Hadramis they believed held sway over pilgrims and behaved insolently towards European crewmembers. Segregation onboard reflected the racial segregation of Hadrami residents in colonial Indonesia, who were categorized as foreign Asians (vreemde Oosterlingen). Hadramis were forced to live in Arab villages (kampong Arab) until 1919. Only after 1914 were such residents allowed to leave these Arab villages without first obtaining permission from and being granted travel passes by government authorities.Footnote 34 Despite this segregation, Hadrami communities were the most established and sizable Arab population in colonial Indonesia during the interwar period and held considerable economic and religious status in cities across the colony. Regardless of their relatively small numbers – approximately 45,000 in 1920, 70,000 in 1930, and 80,000 by World War II – Hadrami quarters grew into active trading districts in cities like Batavia, Surabaya, Palembang, and Pekalongan, largely through the trade of textiles, clothes, building materials, and furniture.Footnote 35 Successful traders often invested their profits into additional businesses in real estate and money lending and, in cities such as Palembang and Pekalongan, the Hadrami influence on local politics and commercial activities rivaled that of powerful Chinese communities.Footnote 36 This influence was partly due to the marriages of Hadrami men and Indonesian women – Hadrami women in the Middle East were largely restricted from traveling – providing “a bridge” that eased their integration into local communities.Footnote 37

Besides marriage, Islam was an important connection between Indonesian Muslims and Hadrami communities, serving as a “powerful unifying force” that helped Hadramis gain financial, religious, and cultural status in colonial Indonesia.Footnote 38 Religion helped integrate Hadramis into Indonesian society and their successes in commercial trade were intricately connected to their esteemed religious positions among Indonesian Muslims.Footnote 39 Their command of the Arabic language and continuing close ties to the Middle East (largely due to circular migration and large remittances) suggested a close bond to the Islamic holy land and was revered by many Indonesian Muslims.Footnote 40 Therefore, although a small fraction of the population, Hadramis occupied a superior economic and legal position in colonial society, which helped inform their identities as Muslim cultural leaders within public religious life.Footnote 41

Yet reverence towards Hadramis subsided with the rise of Indonesian nationalism during the 1920s and 1930s. Although Muslims in colonial Indonesia often viewed differences between Arabs and Indonesians in a positive light, Indonesian nationalism focused on Arab “foreignness” as opposed to shared religion.Footnote 42 Despite our historical awareness of this increasing division, Dutch contemporaries continued to see Hadramis as powerful influences over Indonesian Muslims. Even Snouck Hurgronje felt Hadramis, in particular, were trying to spread Islam and expose Indonesians to the perceived exploitation and injustice perpetrated by the colonial government against them. He went as far as to recommend the wholesale refusal of Hadrami entry into the colony following the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, due to the detrimental moral influence they might have over Indonesians.Footnote 43 Additionally, Hadrami communities focused on “progress” within local communities through education: they built their own schools with curricula focused on Islamic religious teachings, as well as modern languages, mathematics, and geography.Footnote 44 Due to the elevated status of Hadramis within colonial Indonesia and the education available to them within these communities, the Dutch administration continued its attempts to diminish Arab power and prestige throughout the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 45 Part of this strategy was to regulate and police Hadrami movements on Kongsi Tiga ships to and from the Middle East.Footnote 46

Kongsi Tiga’s European officers and captains filed detailed reports about the “nuisance and opposition” experienced by Hadrami passengers who acted as “leaders” onboard and “corrupted the temperament of the pilgrims with their arrogant and insolent behavior.”Footnote 47 For example, the captain of RL’s SS Sitoebondo traveling from Jeddah to Tanjung Priok in the summer of 1930 complained about thirty Arab passengers whom he suspected of traveling with tickets belonging to deceased pilgrims. These passengers continuously disregarded Kongsi Tiga’s onboard regulations by disobeying the bans on smoking and the use of stove devices onboard. They also got into fights, cut the line in the dining hall, littered, and regularly “troubled the doctor with traces of sickness” while refusing all injections and other medical interventions. The captain noted they disturbed “the good usual routine” of the ship through their “uncongenial and impudent behavior.”Footnote 48

Other reports claimed “Arabs setting out for Netherlands India are troublesome passengers and often try to disturb the good order onboard” or accused these passengers of “bother[ing] the more rightful [Indonesian] passengers through their arrogant behavior.”Footnote 49 The Trio’s opinion was that “[i]n general, Arabs are disagreeable and harmful travel companions for Javanese. If they get the chance to snap up the best spots in the pilgrims quarters, they act the boss over their fellow Javanese passengers, they are ‘korang adat’ [asocial or impertinent] in relation to them.”Footnote 50 According to the Trio, Arabs were able to “unjustly take up more room” and get the best spots onboard due to their “bold nature” and “experience in traveling onboard ships.”Footnote 51 This “bold nature” also led to numerous reports suggesting that “in general many Arabs misbehave towards their fellow female passengers while traveling” and the assumption that Arab men acted sexually inappropriately onboard was also “fully shared by the local agents of the Kongsi Tiga.”Footnote 52 At stake in these reports was the most threatening and feared outcome of Hadrami influence: the contamination of Indonesian passengers’ “good spirit.” Arabs represented possible agitators who might turn pilgrims’ compliant behavior against Dutch authority.Footnote 53

In order to counteract this negative influence, Kongsi Tiga segregated Hadrami passengers from Indonesian pilgrims: “[a]s a general rule we consider it undesirable to book Arabs and pilgrims on the same ship … at all events [we try] to lodge Arabs and pilgrims separate from each other.”Footnote 54 Whenever possible, ships designated certain areas specifically for Hadrami passengers, either a “separate hatch” or, preferably, “a separate lockable room is made available, for example the space under the forecastle head.”Footnote 55 European crewmembers were also instructed to monitor Hadrami passengers and “keep an eye on them, especially at night.”Footnote 56 As the 1920s progressed, Hadramis were denied passage on ships that could be “fully booked with real pilgrims” and, if any pilgrims were onboard, they were forbidden from entering “any parts of the ships that pilgrims occupy.”Footnote 57 Instead, Hadramis had to wait until the “last few ships of the season,” which – Kongsi Tiga hoped – would have only a few or no pilgrims onboard.Footnote 58 Kongsi Tiga’s management discussed the wholesale denial of Hadrami passengers on its ships, but concluded such action would cause “difficulties with the Hedjaz government” and be “very troublesome.”Footnote 59 In order to avoid threats to colonial control posed by Hadrami passengers, Kongsi Tiga was willing to forgo profits earned from these fares.

The reports of Kongsi Tiga’s European captains and officers reflect underlying fears that better educated, wealthier, and more independent Arab passengers had the ability to “taint our good name and damage the good spirit of the pilgrims.”Footnote 60 To keep colonial authority intact, Kongsi Tiga’s administrative staff deemed the combination of Indonesian pilgrims and Arabs as “very undesirable” and by the late 1920s local Kongsi Tiga booking agents warned all captains and officers if any Arab passengers would be traveling onboard before the ship sailed.Footnote 61 Imperial prejudices and stereotypes around race played a role in the negative opinions of Hadramis, but, in reality, disruptions onboard were often caused by passengers from colonial Indonesia. For example, in 1926 Hajji Soedjak returned to colonial Indonesia on SS Ajax.Footnote 62 While acting as Chief Hajji (Kapala Hajji) – an onboard liaison between pilgrims and officers – the captain claimed Soedjak caused

much trouble: he held speeches onboard, where the pilgrims were urged towards various provocative actions, directly against the regulations of the ship and later against the quarantine regulations at Poelau Roebiah [Pulau Rubiah in Aceh] which he advised to sabotage as not in harmony with their religion. If not for the fact that the brother of our [Jeddah] Advisor Tadjoedin was on board, things could have been worse.Footnote 63

Rather than obedient submission to Dutch rules and regulations, Soedjak challenged colonial hierarchies by utilizing the sea’s transgressive possibilities and his own fluid mobility, precisely what Kongsi Tiga and Dutch authorities feared might happen to many pilgrims while abroad. Kongsi Tiga’s focus on the comingling of passengers reflected colonial beliefs that anticolonial ideology was imported into the colony from abroad.

Despite denouncing Meccan shaykhs or pilgrim brokers for many of the same reasons as Hadrami passengers, such passengers presented Kongsi Tiga with a different set of challenges. Unlike Hadramis, who could be physically segregated from pilgrims, Meccan shaykhs traveled together with hajjis and shared the same living quarters. Pilgrims generally used pilgrim brokers or shaykhs to arrange their food, accommodation, travel, and documentation for the trip from colonial Indonesia to Jeddah.Footnote 64 In colonial Indonesia, shaykhs had contact with local clerics (kijaji) at Muslim schools (pesantren), where they recruited and advised prospective pilgrims.Footnote 65 Once onboard, there existed “a serious battle to take each other’s customers” as brokers worked to recruit pilgrims for their head shaykh in Mecca, earning commissions on each pilgrim they recruited.Footnote 66 Shaykhs were responsible for pilgrims up until their arrival in Jeddah, when they were transferred to the responsibility of a local shaykh (mutawwif or dalil) or his representative (wakil), who accompanied them throughout their pilgrimage in the Hejaz, arranging all food, accommodation, and transport.Footnote 67 Like many Dutch administrators, even Snouck Hurgronje viewed pilgrim brokers as corrupt predators who took advantage of pilgrims’ dependence.Footnote 68

Like Hadrami passengers, Kongsi Tiga saw Arab shaykhs as “difficult passengers who quite often cause trouble or discontent on board”Footnote 69 and accused them of usurping “more space on board for themselves than they have a right to.”Footnote 70 They were vilified for persuading pilgrims to change from one shaykh to another during the outward voyage and blamed for advancing “part of [pilgrims’] expenses [before sailing], which, later on, the pilgrims can only repay with great difficulty.”Footnote 71 Unlike Hadrami passengers, shaykhs traveled together with pilgrims on the steerage decks and, according to Kongsi Tiga reports, had more ability to influence fellow passengers in negative ways.Footnote 72 One report noted the “tendency of Meccans to swear and pass the time by making unnecessary complaints” and feared these behaviors would be mimicked by Indonesians once “back in the Fatherland.”Footnote 73 Kongsi Tiga believed pilgrims needed protection against shaykhs because “[m]ost pilgrims lack the courage to complain at the right moment.”Footnote 74 SMN, RL, and NSMO instructed European captains and officers to protect anyone who “paid too little attention to himself,” for example if denied the rightful amount of space below deck due to a “greedy” shaykh taking up too much room.Footnote 75

Using rhetoric from the Ethical Policy, Kongsi Tiga similarly stressed the Trio’s responsibility to protect “innocent” pilgrims from the conniving ways of Meccan shaykhs. Although there may have been shaykhs who had questionable business practices, the Trio’s deeper concerns revolved around the powerful position held by shaykhs within the hajj trade and their ability to “prevent the smooth running of business.”Footnote 76 From canvassing passengers in colonial Indonesia, to maintaining order onboard, to controlling the movements of pilgrims after disembarking at Jeddah, shaykhs wielded an enormous amount of power and infringed on Dutch control over the entire hajj process. SMN, RL, and NSMO were, therefore, anxious to reform the use of shaykhs or, if possible, cut them out of the hajj pilgrimage entirely. The loyalty of shaykhs originating from the Hejaz to the Dutch regime could not be guaranteed. They were believed to take advantage of pilgrims onboard and in Mecca and were seen as troublemakers at sea. All three Kongsi Tiga companies agreed “it would be in the interest of the pilgrims if this [shaykh] traffic could be stopped.”Footnote 77

Shaykhs from colonial Indonesia, largely recruited from among Indonesian pilgrims who had previously worked or studied in Mecca for extended periods of time, were also present on most Kongsi Tiga ships, but the Trio assumed these Indonesian pilgrim brokers could be relied upon to uphold imperial order onboard and support the Dutch Empire more broadly.Footnote 78 While Arab pilgrim brokers were seen as untrustworthy and considered “more damaging than recruiters of [the pilgrims’] own nationality,”Footnote 79 Kongsi Tiga claimed it was of “the greatest importance to our companies to have a broker corps on which we can rely and from which we can expect support at times when we have to face competition.” The Trio believed it “logical that the bookings of the native pilgrims should be handled by people of their own race.” Broker loyalty was crucial to the Trio as challenges to Kongsi Tiga’s shipping monopoly increased during the 1920s and 1930s. Kongsi Tiga recognized they would “naturally be much stronger if we were backed by a reliable and loyal corps of brokers and if the influence of the Mecca shaykhs on the bookings were less than it is at present.” The influence of Meccan shaykhs depended on Arabs holding an elevated position within colonial Indonesia, which the Kongsi Tiga saw as based on “the fact that they come from the Hejaz and secondly owing to their having the disposal of more capital and their exercising a certain religious influence on the simple native.” Ultimately, Kongsi Tiga believed these pilgrim brokers could not be trusted or depended upon to support Dutch shipping because it was “a matter of indifference to a Mecca shaykh by which company the pilgrims travel, as his earnings are derived from the stay in the Hejaz” and the companies could, therefore, “never expect any loyal support from the Mecca shaykhs.”Footnote 80

The anxious reactions of Dutch shipowners towards Arab passengers suggest there were large numbers of such travelers onboard but company archives show just the opposite. Hadramis and shaykhs normally represented a very small percentage of those onboard Kongsi Tiga ships, with anywhere from thirty to a hundred Arabs traveling amongst the thousand-plus total passengers on each ship. For example, during the 1928–29 pilgrim season, only 614 Arab passengers were transported on Trio ships, a small number compared with the thousands of passengers who traveled on Kongsi Tiga ships that year.Footnote 81 These numbers suggest that suspicion of Dutch shipowners likely outweighed actual subversive activities happening onboard but, nevertheless, such suspicions continued to inform Kongsi Tiga’s maritime policies.

Kongsi Tiga repeatedly failed to find “a satisfactory solution to the problem” of counteracting the influence of Arab shaykhs.Footnote 82 As with Hadrami passengers, barring Arab shaykhs from entering the colony by refusing “to transport the shaykhs altogether” was entertained, as was a higher entry fee into the colony: “if the same [fee] could be [be enforced on ships running] to and from Singapore their [financial] outlay to travel to colonial Indonesia would be increased to such an extent that few would consider making the voyage.” These ideas were abandoned as they would cause “great trouble with the Saudi Arabian government, which must be avoided.”Footnote 83 Therefore, surveillance was the only option to “stop this nuisance” of shaykh influence and interference onboard. Through “daily control of the pilgrim transports” and “daily inspections of the pilgrim living quarters” Kongsi Tiga’s European crewmembers could “prevent this evil from taking on further dimensions.”Footnote 84 European captains and officers were instructed to “watch them and prohibit the use of Arabs onboard pilgrim ships as liaisons [Kapala Hajji] for the distribution of meat, etc. or for the conveyance or maintenance of regulations over order on board.”Footnote 85 By insisting Meccan shaykhs were never appointed Chief Hajji, Kongsi Tiga further eroded the special status of these passengers, whom they believed held a revered and, therefore, dangerous position amongst Indonesian pilgrims.Footnote 86

Meccan shaykhs were required to make themselves known to local agents when they were issued their tickets. While each ticket had the individual traveler’s name on it, there was a separate protocol for the handling of Indonesian pilgrim tickets and those of Meccan shaykhs. The Trio argued that since most pilgrims were illiterate and traveled together in groups, their tickets were unknowingly exchanged with others in the group on a regular basis. Kongsi Tiga would thus “NOT stick rigidly to the rule of the personal marks of their tickets.” Meccan shaykhs, on the other hand, were “experienced travelers, they can all read and write and they invariably retain their own ticket.” Local agents in Jeddah were familiar with the “long-held custom” of closely scrutinizing the individual tickets of Arab passengers, while the same requirement was overlooked for Indonesian pilgrims.Footnote 87 By closely monitoring the behavior of Meccan shaykhs onboard and keeping records of their identity through the issuance of personal tickets, Kongsi Tiga hoped to build cases against individual shaykhs it felt should be barred from traveling on its ships. If Kongsi Tiga’s agents could provide “concrete and well-founded cases of corruption or fraud, maltreatment of prospective pilgrims or misconduct in Java, visas to enter Java can be refused [in Jeddah] by the Dutch legation.” Although Kongsi Tiga recognized that “shaykhs being refused admittance in this way will of course be replaced by others” they hoped the replacement brokers would be “a better and less aggressive type of shaykh.”Footnote 88

Kongsi Tiga was also under scrutiny from Muslim communities in colonial Indonesia who questioned Dutch ability to ensure the safety and comfort of pilgrims in terms of their interactions with shaykhs. Indonesian publications – such as the Palembang periodical Pertja Selaten and the Pewarte Deli (Deli Herald) – published articles arguing that “the Dutch government and Her representatives must take ‘harder’ action against the pilgrim shaykhs, etc.” This action was only possible “while still respectful of not bringing [colonial Indonesia’s] neutral position in terms of religion [kenetralen pada sgama] into danger.” Very aware of the power of public opinion within colonial Indonesia, Dutch authorities responded vehemently to such articles: “in terms of our ‘hardness’ (refusal of visas, etc.), we cannot go any further than a definite limit. Overstepping these would lead the pro-Arabic magazines in the Indies, which claim to have the interests of pilgrims in mind, to propose these steps are meant as a hindrance to the pilgrimage.”Footnote 89 Public concerns over the power of pilgrim brokers made the issue all the more pressing and tricky for Kongsi Tiga, which acted “with an eye on the danger to their own popularity.”Footnote 90

Dutch opinion believed the combination of incendiary factors experienced both onboard hajj ships and within the Middle East (discussed in Chapter 4) provided seditious influences while pilgrims were spatially removed from the colonial order in Indonesia. The journey was meant to dampen any seditious ideas entertained while abroad, before pilgrims returned to colonial Indonesia. In this way, policies onboard served to reeducate pilgrims who may have forgotten their place in the colonial order while on hajj. Kongsi Tiga worried that if potentially subversive Arab passengers held an elevated status at sea, then “pilgrims would listen to these [passengers] more than the captain of the ship” and Kongsi Tiga decried “surely we must remain boss on our own ships!”Footnote 91

Race, Class, Consumer Power, and Competition

Like the segregation of steerage passengers, Kongsi Tiga’s policies regarding the transport of passengers in higher-class accommodation were also informed by colonial Indonesia’s racialized class hierarchies. Upper-class passengers, or cabin passengers, were divided into five categories within three classes of accommodation. Class A cabins were reserved for European and high-ranking Indonesians and were the most exclusive and expensive accommodation onboard: servants were assigned to wait on Class A passengers in their cabins, each with its own private bathroom and toilet, and ate their meals in the salon together with the European captain and officers. Class B cabins were available to Indonesian civil servants and other non-European private passengers. Class B passengers also had servants to care for their cabins and were provided better food than ordinary pilgrims, but were not guaranteed use of a private bathroom or toilet and were prohibited from using the salon. Class C passengers paid ƒ150 extra for private cabin accommodation, but were otherwise treated as ordinary pilgrims without special food, servants, or lavatories. On the return journey from Jeddah, all upper-class passengers were permitted to return on any ship – provided a cabin was available – and, therefore, did not have to wait their turn for the next available ship like those in steerage.Footnote 92 It was mandatory that all Indonesian cabin passengers were “natives of better standing such as regents, merchants, etc. who are traveling for [their] own account and who can be relied on to behave decently.”Footnote 93

Despite these policies, Indonesian pilgrims of “better standing” were often discouraged from travelling in Class A cabins in the Trio’s attempt to retain the most exclusive spaces onboard solely for European use. For example, during the 1937 hajj season pilgrims Mr. and Mrs. Gelar Soeis Soetann Pengeran disembarked from RL’s SS Buitenzorg after a three-week journey from Tanjung Priok to Jeddah, where they immediately visited the Dutch Consulate to lodge a complaint about their sea voyage. Kongsi Tiga’s agents in Medan and Batavia had dissuaded the couple from traveling in Class A accommodation and instead assigned them to a Class B cabin for which they paid ƒ400 each.Footnote 94 Although the couple found both the cabin and service to their liking, they were denied use of the toilet and bathroom adjacent to their cabin, despite promised access by Kongsi Tiga’s ticketing agents in Batavia.Footnote 95 Additionally, the couple was prohibited from eating in the salon with Class A passengers and European crewmembers. Instead, they were served the same food as steerage passengers on the decks below. Only after several complaints did the captain supply them with bread, cheese, and eggs for breakfast and supplemental sweets and puddings with their other meals, but they were still prohibited from entering the salon for the duration of the trip.Footnote 96

As a result of this complaint, the three Kongsi Tiga firms debated whether or not they should continue accommodating pilgrims in upper-class cabins. Kongsi Tiga’s management feared that allowing Indonesians access to higher-class accommodation would give them a sense of entitlement and result in more requests for special treatment and expanded privileges onboard. SMN and RL questioned if the British-owned NSMO was trying to make a “political statement” by accommodating so many Indonesian passengers in Class A and B cabins and allowing “prominent natives to, more or less, travel like Europeans.” NSMO reassured the other firms that passengers only occupied these spaces when there were “no other European passengers onboard” and access to the salon was only given when “there was no separate deck.”Footnote 97 Additionally, SMN and RL worried about granting access to the salon, which they saw as a European space off-limits to Indonesian pilgrims, no matter what their social standing in colonial Indonesia.

Besides Indonesian pilgrims, many Hadramis had the financial means to purchase Class A, B, and C tickets, but were prevented from doing so, as the Trio doubted their ability to “behave decently.” In theory, allowing Hadramis to travel in higher-class cabins would keep them separate from Indonesian pilgrims for the duration of the voyage, but this was not in line with Kongsi Tiga’s policies denying Hadramis an elevated status onboard. Throughout the 1930s, Lallajee and Company, Kongsi Tiga’s agent in Al Mukalla, received “letters from many places in Hadramout asking us to arrange for them second and even first-class passages for Singapore.” While the agents were prepared to sell these tickets “[p]rovided accommodation for the class is available on board the steamers,” they received little information from Kongsi Tiga’s management about how to proceed: “[o]wing to absence of sufficient information about the fares, we experience great inconvenience as to charges, and have to wait until the arrival of steamers to ask the captains. We shall be obliged, if you will furnish us with full particulars about it.”Footnote 98 Kongsi Tiga remained vague with local agents about such fares due to internal conflicts over whether or not the Trio should allow Arab passengers higher-class accommodation.

SMN, RL, and NSMO did not always agree on policies regarding cabin passengers and the three companies struggled over the balance between financial profits and maintaining colonial hierarchies onboard. NSMO, the only non-Dutch company in the pool, was “quite prepared to accept Arabs in first class accommodation in any of our vessels fixed to call at Makallah [sic], provided they were able to pay their passage money.”Footnote 99 RL disagreed and felt that despite NSMO’s determination “to rent first class cabins to Arabs … This does not change our position, that we do not want the accommodation for European passengers made available for Arabs.”Footnote 100 SMN took an even tougher stance against offering cabin accommodation to Hadramis, concluding “we must not transport any Arabs in cabins that are also used by Europeans.”Footnote 101 Both SMN and RL felt “the cabins intended for European passengers must in no case be made available for the transport of Arabs.”Footnote 102 Ultimately, the Trio decided on a compromise to “look case by case if reserved accommodation, which also would be rented to C category pilgrims, can be made available for Arab steerage passengers.”Footnote 103 For the Dutch companies, profits were secondary to concerns over racial and class contamination onboard, while NSMO was less concerned. Ultimately, all three companies agreed that “[a]t the most, we can consider [providing] clerks cabins on ships where no pilgrims are traveling.”Footnote 104

Within the strictly regulated spatiality onboard Kongsi Tiga ships, foreign Asians traveling in steerage held a position of power onboard and presented a danger to Dutch colonial authority by subverting the colonial hierarchies implemented by Kongsi Tiga. Indonesians of “better standing” were also present within colonial Indonesia’s social hierarchies and therefore did not transgress colonial norms or threaten colonial stability in quite the same way as Hadramis traveling in the higher classes. Along with anxieties over contamination of European spaces, the SMN and RL were worried about the example higher-class Arab passengers would set for Indonesian pilgrims, many of whom had never left the colony and were traveling across global maritime networks for the first time. Kongsi Tiga wanted to ensure these experiences did not include encouragement to question Dutch colonial authority. The transoceanic mobility of passengers refracted racial hierarchies present in colonial Indonesia, ultimately producing a hierarchical structure onboard unique to Kongsi Tiga ships.

By the 1920s, hajj shipping in Asia was monopolized by a small number of European shipping companies that dominated pilgrim transport to and from colonial Indonesia, colonial India, and the Straits Settlements. Despite viewing each other as competitors, these European companies cooperated with each other through shipping conferences. Yet intense competition for passengers meant European companies constantly adjusted their ticket prices to match or undercut European competitors.Footnote 105 Despite ongoing rate wars, conferences primarily accepted the right of each European nation served by the conference’s ships to act as a participating member and the “legitimacy of each member’s existence was usually mutually recognized.”Footnote 106 Unlike the “horizontal integration” of European shipping conferences, Indonesian, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese hajj transport competitors were excluded from cooperation with the Kongsi Tiga. While this may be partially due to a “technological hierarchy” favoring larger and faster European ships, shipping was also structured around racial discrimination informed by conventions in colonial Indonesia.Footnote 107

Due to both the economic and political repercussions of losing hajjis to competing firms, Kongsi Tiga saw the loss of passengers as a serious issue and commissioned numerous inquiries to learn why passengers chose competing firms. Even after their record-breaking hajj season of 1926–27, Kongsi Tiga sent employees to ask hajjis in person why some opted for foreign ships, especially vessels leaving from Singapore. The answers were more complicated than simply inadequate food onboard or wishing to bypass required vaccinations in colonial Indonesian ports.Footnote 108 Pilgrims found the lower prices onboard Singapore ships “enticing” and believed ships leaving from Singapore were more concerned with passenger comfort. Those interviewed praised the fact that Singapore ships accommodated “much more baggage in their quarters than did the Java boats.”Footnote 109

Despite many regulations in the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance stipulating required provisions onboard Dutch pilgrim ships, a lack of oversight and lackadaisical inspections left enforcement of correct procedures largely up to each individual ship. For example, pilgrims could be transported, according to one report, in “gunpowder rooms, that often lie in the mid-ship, [having] no portholes so that the ventilation is never as good as in the other pilgrim quarters. Moreover, the room is darker because the daylight cannot shine in.” Yet, according to the Pilgrims Ordinance, transport in these rooms was “permissible, provided certain requirements are met.”Footnote 110 Even in the designated pilgrim quarters, the large open rooms below deck were crowded with people and largely devoid of comfort save for items brought by the pilgrims themselves. The Pilgrims Ordinance only required one saltwater shower and two latrines for every hundred passengers onboard.Footnote 111 Within these crowded and stifling conditions, the Trio was confused over why pilgrims spent relatively little time on the upper decks: “[I]t is a remarkable fact that most pilgrims gladly stay all day in the pilgrim holds amid the hanging mosquito nets, (wet) sarongs etc., etc., … It is as if they shun the fresh sea air.” The Trio assumed pilgrims stayed below deck due to weather conditions: “our pilgrims on board are generally not dressed warmly enough. In the Red Sea in particular it can be very cold during the first months of the season.”Footnote 112

A more informed explanation of these conditions was written by public health inspector W. G. de Vogel in a 1927 report. De Vogel’s report highlights how ships themselves were to blame for pilgrims avoiding the upper decks. The report exclaimed that “not a square inch of space [is] left on the upper deck to which passengers from the between-decks can go for air or change of scene.” Additionally, it was nearly impossible to move the pilgrims’ baggage below deck and, therefore, difficult to clean the ship throughout the trip: “even in the best regulated ships, conditions below grow worse and worse as the voyage proceeds.”Footnote 113 The onboard experiences of R. A. A. Muharam Wiranatakusumah, the Regent of Bandung, reflect the difficult conditions experienced by steerage passengers on RL’s SS Soerakarta. The decks below were crowded, dark, and stuffy and after a few days “the heat in the holds was unbearable.”Footnote 114 The passengers suffered from sea-sickness and the “rolling of the ship was always evident in the depths of the hold … [and] seen clearly on the faces of passengers who, with their upset stomachs, craved more space.”Footnote 115 SMN and RL hoped the introduction of new ships such as RL’s MS Kota Radja and MS Kota Inten would improve conditions onboard, but by 1936 RL was still noting that quarantine authorities rarely enforced the 1926 International Sanitary Convention’s regulations and then only to the extent that each vessel “must have a suitable tween-deck space available, have part of the upper deck sheltered by an awning, and have a doctor on board.” For the rest – wooden upper deck, life-saving appliances, hospital, permanent kitchens, latrines, etc. – the company noted that inspection authorities “do not bother” and they had “no reason to believe that they will change this system.”Footnote 116

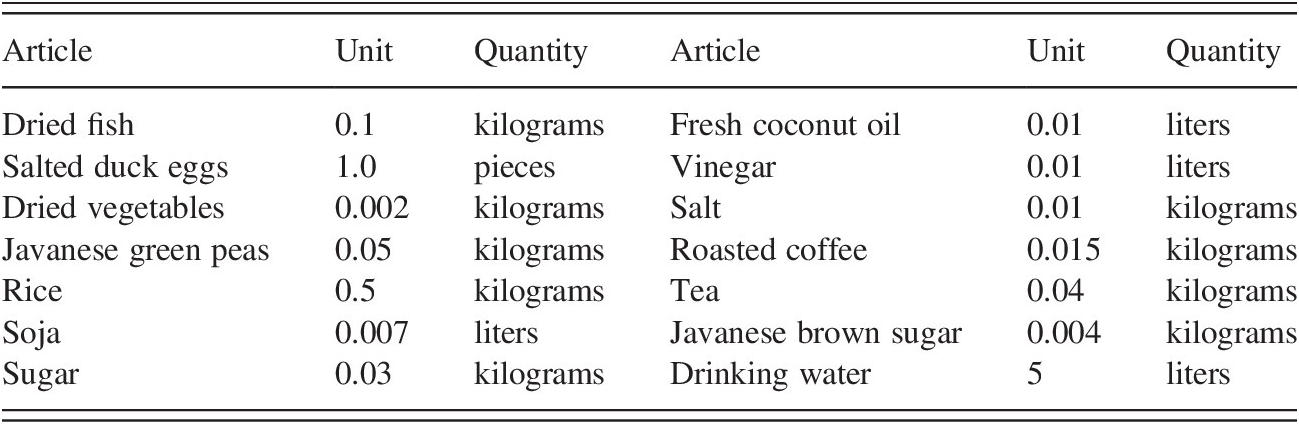

The Trio’s food rationing policies were also investigated to determine possible room for improvement (Table 1.2). Unlike Kongsi Tiga ships where food was included in the ticket price, Singapore ships provided only firewood and water and it was up to passengers to bring their own food onboard and prepare it themselves. Kongsi Tiga’s report claimed most pilgrims “found the food provisions agreeable” and “were appreciative of the rice, dried fish, salted eggs and other provisions given to them” onboard Dutch ships.Footnote 117 Commenting on RL’s steerage rations, Regent Wiranatakusumah noted that the “food was good” and was pleased with the amount of water provided and the salted fish and eggs that helped comprise the ship’s three daily meals for the majority of passengers.Footnote 118 As a high-class cabin passenger, however, Wiranatakusumah himself would have enjoyed more sophisticated food throughout the trip, although his memoir does not address this distinction. While Kongsi Tiga saw these provisions as a positive selling point for its ships, British shipowners in Singapore generally believed pilgrims preferred Singapore ships precisely because they did not offer food to pilgrims. One British report highlighted this negative attitude: “Netherlands East Indies pilgrims are given rations and are forbidden from bringing any other foodstuffs on board aside from those provided and preparing their own food is forbidden.” Kongsi Tiga countered this criticism by stressing that “if there are parts of his usual diet [not included in the rations] that he cannot go without, no one will deny him the fact he can prepare his own meal to his own taste.”Footnote 119 Wiranatakusumah experienced this on SS Soerakarta: those pilgrims “used to a little good eating, cook for themselves and others bring with them conserved meat, cans of sardines, etc.”Footnote 120 While food was a contested issue between British and Dutch shipowners, Kongsi Tiga saw it as a major advantage over its Singapore-based competitors.

Table 1.2 Daily rations per steerage pilgrim per the 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance

| Article | Unit | Quantity | Article | Unit | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried fish | 0.1 | kilograms | Fresh coconut oil | 0.01 | liters |

| Salted duck eggs | 1.0 | pieces | Vinegar | 0.01 | liters |

| Dried vegetables | 0.002 | kilograms | Salt | 0.01 | kilograms |

| Javanese green peas | 0.05 | kilograms | Roasted coffee | 0.015 | kilograms |

| Rice | 0.5 | kilograms | Tea | 0.04 | kilograms |

| Soja | 0.007 | liters | Javanese brown sugar | 0.004 | kilograms |

| Sugar | 0.03 | kilograms | Drinking water | 5 | liters |

Note: Two persons under ten years of age to count as one adult, children under two years are not entitled to rations. The daily quantity of drinking water shall be supplied to each person in full, irrespective of age.

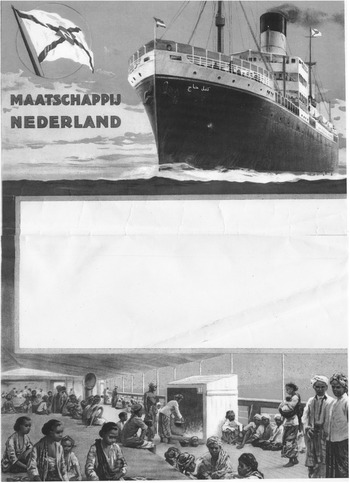

As shipping competition increased, not only provisions, but also additional onboard comforts became points of contention allowing pilgrims an oppositional voice within the restrictive maritime environment of Dutch hajj transport. Even among the three Kongsi Tiga firms, pilgrims developed strong preferences based on the treatment accorded them by each firm. All three companies kept tabs on their share of pilgrim revenue and SMN and RL, despite the tranquil images portrayed in advertisements like that shown in Figure 1.2, consistently trailed far behind NSMO in terms of popularity among pilgrims. From 1920 to 1937, NSMO transported approximately 49.3 percent of pilgrims, while SMN and RL together averaged 50.7 percent of all 342,779 passengers.Footnote 121 SMN and RL were concerned over this disparity and commissioned detailed investigations to discover the reasons behind it.

SMN and RL’s investigations found four main reasons why pilgrims had a strong preference for NSMO ships. First, while SMN and RL ships doubled as freighters outside of the hajj season, NSMO had a few newer ships devoted exclusively to hajj transport, each with permanent pilgrim accommodation onboard. Second, NSMO’s use of the center castles in addition to the upper steerage decks provided more room for pilgrims than the upper deck space, bathrooms, and WCs on SMN and RL ships. This extended onboard space resulted in smaller numbers of pilgrims per square foot and therefore more space per pilgrim. Third, roomier accommodation along with the installation of bigger airshafts meant NSMO ships were better ventilated below deck than SMN and RL vessels, making the voyage more comfortable for pilgrims. Finally, NSMO ships were faster and the travel times shorter due to the fact they bypassed many colonial Indonesian ports frequented by SMN and RL and instead sailed directly between Padang’s Emmahaven, Batavia’s Tanjung Priok, and Jeddah.Footnote 122 While it is reasonable to question whether some passengers were aware of NSMO’s British ownership – perhaps providing an additional reason to choose the company over SMN and RL – the archives provide no evidence of this. Considering NSMO ships were run from Amsterdam, sailed under the Dutch flag, and employed Dutch captains and officers onboard, it is unlikely that British ownership would have been readily apparent to most pilgrims.

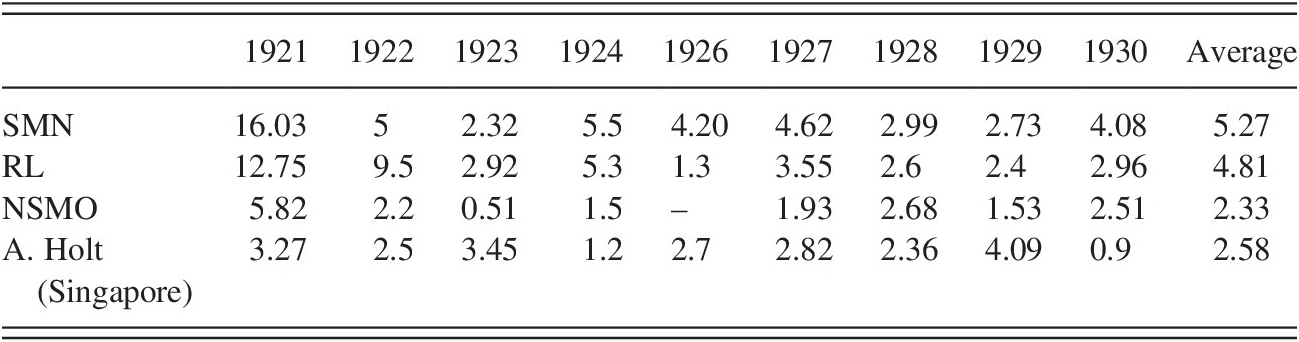

Rather, due to the shorter travel time, more space onboard, better accommodation, and improved hygiene and health facilities, NSMO ships were generally more comfortable than those of RL and SMN and NSMO ships experienced lower mortality rates amongst the passengers. Official shipping data made these differences clear to all three firms. For example, during the 1927–28 hajj season the SMN journey from Tanjung Priok to Jeddah took twenty-two days, RL twenty-one days, and NSMO ships only eighteen days.Footnote 123 As Table 1.3 shows, during the return voyages that season, SMN’s fleet experienced 170 pilgrim deaths, RL’s had 169, and NSMO’s fleet suffered the lowest mortality rate of the three with 148 deaths onboard.Footnote 124 For all these reasons, NSMO took the lead in the number of bookings every year and only after its ships were fully booked did SMN and RL see their ships begin to fill up.Footnote 125

Table 1.3 Percentage of deceased pilgrims on Kongsi Tiga, 1921–30

| 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMN | 16.03 | 5 | 2.32 | 5.5 | 4.20 | 4.62 | 2.99 | 2.73 | 4.08 | 5.27 |

| RL | 12.75 | 9.5 | 2.92 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 3.55 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.96 | 4.81 |

| NSMO | 5.82 | 2.2 | 0.51 | 1.5 | – | 1.93 | 2.68 | 1.53 | 2.51 | 2.33 |

| A. Holt (Singapore) | 3.27 | 2.5 | 3.45 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 2.82 | 2.36 | 4.09 | 0.9 | 2.58 |

SMN and RL scrambled to make up for this disparity by taking the preferences of pilgrims into account and changed their businesses practices to accommodate pilgrim demands. RL added new motor ships to its pilgrim fleet in a bid to attract passengers. SMN expanded the space available to pilgrims on its upper steerage decks. Although these changes took considerable effort, SMN and RL understood that more space and increased comfort onboard were major reasons why pilgrims preferred NSMO ships.Footnote 126 Unfortunately, simply adding more space was not enough to turn the tide of hajj preferences and SMN lamented pilgrims’ continued preference for NSMO ships: it is “as if our Company was being boycotted. This boycott is especially noticeable in the Batavia area, comprising the largest pilgrim center.” One report from SMN even claimed the disparity in passengers was not merely due to slower and older ships in their fleet, but to the “the Eastern mentality of the parties involved.”Footnote 127 This patronizing explanation may reflect the frustration felt by SMN administrators, who were at the mercy of pilgrim demands. Through their consumer power, pilgrims held SMN in a financial stronghold and the company was forced to ask its local agents for suggestions and advice about how it might sway public opinion and attract more customers.

Local agents suggested two main reasons behind NSMO’s primacy in the market, both concerning the treatment of pilgrims and respect shown to them as paying customers with a right to certain comforts onboard. First, the agents argued that pilgrims on NSMO ships were shown more respect by the company’s crewmembers. Unlike NSMO, SMN’s onboard regulations focused on maintaining order and – in the company’s own words – saw “tidiness reign” above all else. SMN’s local agents pointed out to management in Batavia that the company saw it as

necessary that the pilgrims are repeatedly sent out of the room to the deck above and also again and again are driven away off the deck. The people find it simply dreadful, because they couldn’t recognize the reasons why it happened. It follows that during the round-trip season of 1927 in certain instances the chasing away of people in a less tactful way appears to have taken place, with the result that the specific ship and therefore Company involved received a very bad name in the villages [dessas].Footnote 128

SMN’s onboard regulations for keeping ships clean managed to alienate passengers and make their voyages extremely uncomfortable. This treatment was interpreted by many as a lack of respect and appreciation on the part of SMN towards its paying customers, who, in return, took their business elsewhere.

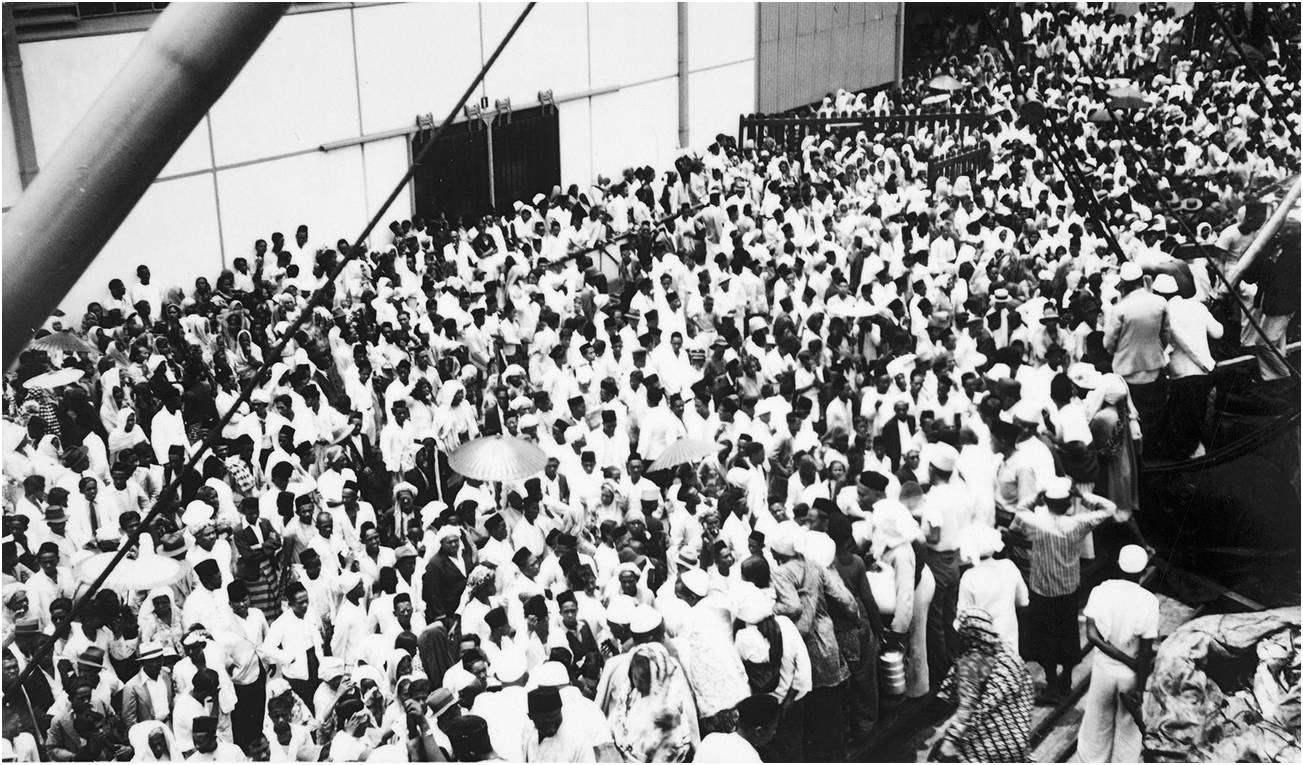

Second, local agents pointed out that passengers preferred the liberties shown them by NSMO prior to departure. While SMN’s regulations were “very good from a European standpoint (the embarkation always ran orderly and calmly),” the pilgrims preferred NSMO’s manner of pushing off to sea. All well-wishers who traveled with the aspirant hajjis to port were welcomed onboard NSMO ships prior to departure in order to see their loved ones off. These friends and family, who sometimes traveled long distances together with the departing hajji in order to say farewell, could “behold with their own eyes how the relative will be accommodated on the pilgrim ship.” Agents stressed that these same friends and family members might eventually wish to go on hajj. Allowing them onboard to “appreciate the facilities” would encourage patronage of NSMO in the future and “when they are ready to depart they will choose the Company they had previously visited.”Footnote 129

After hearing the reasons why pilgrims were unsatisfied with its service from local agents, SMN immediately changed its embarkation procedure to mimic the NSMO model. Further, SMN’s captains “received instructions that the ship management must adapt more to the pilgrims’ wishes” and ensure crewmembers would not chase pilgrims from one space to another in a harsh manner.Footnote 130 Similar concessions were made to pilgrims’ desires to bring folding cots and deck chairs for use onboard. Although these items were “more and more in fashion” on both Dutch and British pilgrim ships, SMN and RL saw them as unnecessary luxury items that upset order onboard.Footnote 131 The 1922 Pilgrims Ordinance ambiguously stated that no cargo could “unfavorably affect the health or safety of the passengers” and pilgrims were only legally provided with one-third of a cubic meter of deck space per person. Therefore, most baggage was stored in the hold for the duration of the voyage.Footnote 132 Kongsi Tiga argued that with cots and chairs in use on deck, “[l]ittle room remains in the pilgrim quarters and on deck in which to move, while it becomes very difficult to keep these areas clean.”Footnote 133

While the discussion over cots and chairs referred to adequate amounts of space and maintaining proper hygiene in pilgrim living quarters, SMN and RL also feared the inequity such items might promote among steerage passengers and were adamant about diminishing class distinctions between such passengers. Kongsi Tiga believed owners of folding cots and deck chairs “unfairly furnish themselves at the cost of the legroom and deck space of their fellow passengers” and if the use of such comfort items were to continue, “people must little by little change over to the establishment of classes within pilgrim transport.”Footnote 134 The Trio was unwilling to make such a change and remained adamantly against creating a more expansive class system amongst steerage passengers, concluding “[f]or the sake of the mass, it is actually better to forbid the use of deck chairs onboard pilgrim ships all together.”Footnote 135 Ultimately, due to increasing competition, Kongsi Tiga was forced to amend its policy on such “luxuries” if it wished to retain passengers from Singapore-based competitors who were more lenient with baggage allowances.Footnote 136 Kongsi Tiga conceded to pilgrim demands by allowing the use of folding cots and deck chairs at the cost of ƒ10 extra per chair or cot.Footnote 137 For some, ten guilders was a tenable price to pay for making onboard living more comfortable, but for the Dutch shipowners these material comforts were a threat to order and class hierarchies, which they feared might be eroded through the use of “luxuries” in the steerage class.

In spite of the regulations imposed on Kongsi Tiga ships, competition within hajj shipping increasingly became an avenue for pilgrims to sidestep the Trio’s monopoly over pilgrim transport. Pilgrims used their consumer power to express dissatisfaction with Dutch treatment of pilgrims and increasingly purchased fares from companies they felt were most amenable to their wellbeing. Opting for foreign shipping companies, as well as exercising preference between the three Kongsi Tiga firms, provided hajjis an opportunity to voice their demands for increased respect as paying customers and accessibility to more material comforts onboard. By exercising their economic power as consumers of maritime transport, pilgrims forced Kongsi Tiga to actively address their concerns and occasionally even alter their rules and regulations.

Shipping in Muslim Hands: Penoeloeng Hadji

In the context of rising anti-colonialism during the late 1920s and 1930s, some Islamic groups in colonial Indonesia felt that simply choosing one Kongsi Tiga firm over another failed to make a powerful statement against Dutch monopolization of hajj transport. Increasing demands in colonial Indonesia to “make use of a Muslim [owned shipping] opportunity” alarmed Kongsi Tiga’s management. Muslims wanted to control their own transport to and from one of the most important religious experiences of their lives and some Indonesians hoped an entire hajj shipping firm would be established in the near future, ensuring hajj pilgrimage remained completely “in the hands of Muslims.”Footnote 138 Religious objections to the Dutch hajj shipping monopoly, based around larger nationalist and anticolonial struggles, were the most threatening form of competition in the eyes of both Dutch shipowners and the colonial administration.

The reformist Islamic organization Muhammadiyah made one of the most promising attempts at an Indonesian-owned hajj shipping company during the interwar period. First founded in Yogyakarta in 1912 by Hajji Ahmad Dahlan, Muhammadiyah embraced modernization and promoted religious, educational, and cultural reforms.Footnote 139 The organization was cultural and religious rather than political per se and established schools, boarding houses, and cooperatives for peasants and traders.Footnote 140 Along with promoting education and maintaining local mosques, prayer houses, orphanages, and clinics, the organization also published a vast amount of printed material promoting Islamic reforms incorporating modern thought into religious doctrine.Footnote 141 If any indigenous group were to receive Dutch support, it would likely have been Muhammadiyah, which, like the colonial authorities, “launched a direct attack on the power and prestige” of local clerics (kijajis), along with the “religious education they were providing the masses.”Footnote 142 In theory, the Dutch could have viewed this organization as an ally in their quest to rid colonial Indonesia of subversive religious ideas and people within local Muslim schools (pesantran).Footnote 143 However, in reality, Dutch suspicions around the political underpinnings of Islam during the 1920s and 1930s informed the ways Kongsi Tiga and the Dutch colonial administration handled Muhammadiyah’s attempt at hajj shipping. The group’s Islamic affiliation turned it into yet another enemy of Dutch colonial authority.

In 1930, Muhammadiyah made plans to charter two ships under the name Penoeloeng Hadji (Hajji Helper or PH) to carry pilgrims to Jeddah during the upcoming hajj season. The organization argued that by patronizing Kongsi Tiga and traveling with non-Muslims to the Middle East, pilgrims were not truly completing the fifth tenet of Islam. Unlike Dutch companies, PH promised their ships would put the religious concerns of pilgrims above all else: PH ships would provide separate prayer areas for men and women and run educational courses onboard instructing hajjis about the rites to be performed on the pilgrimage. PH would also improve material comforts by adding a restaurant and library, providing passengers access to a radio, and employing a full medical staff including a doctor and both male and female nurses.Footnote 144 Further, firewood and water would be included in the ticket price of ƒ250, exactly the same fare as charged by Kongsi Tiga that year. Unlike the Dutch shipping monopoly, PH was a nonprofit endeavor aimed at eventually decreasing travel costs for hajjis in the hopes of making the pilgrimage accessible to larger numbers of Indonesian pilgrims.Footnote 145

As much as it was an Islamic endeavor, PH was also an act of nationalist autonomy. Muhammadiyah insisted that indigenous-owned ships would correct Kongsi Tiga’s attitude that “hajj-transport exists under their power.” Many critics of Kongsi Tiga agreed that “[p]eople naturally prefer to depart with a ship that is dispatched through people of their own nation, unless they intentionally want to stuff another man’s pocket.”Footnote 146 Others questioned why the situation of Indonesian pilgrims remained inferior “while other nations, Egyptians, and British Indians for example, were respected while undertaking the pilgrimage.” Still others blamed the lack of an Indonesian-owned shipping company on the racist nature of colonial education. According to one Indonesian journalist, this inferior education resulted in a grave lack of indigenous confidence: “[o]ur nation has put very little trust in our own power and attaches little value to it; the cause of which can be found in the fact that we are raised to be weaklings, without any sense of responsibility for taking care of our own affairs.” Control over pilgrim transport meant Islamic communities in colonial Indonesia wouldn’t need to “stay forever dependent on the help of foreigners.”Footnote 147 Such arguments promoted indigenous shipping lines as a step towards nationalist autonomy and the eventual creation of an independent Indonesian nation.

Nationalist undertones were evident in Penoeloeng Hadji’s criticisms of Kongsi Tiga. Public notices posted by local travel bureaus such as Batavia’s Penoeloeng Hadji Hinda Timoer promoted PH’s ships by promising the vastly improved conditions onboard. Official PH propaganda highlighted the negative aspects of Kongsi Tiga’s policies, while simultaneously promoting the special accommodation its ships would provide. PH ships would be

satisfactorily big, good, and fast. On board will be a special room in which to pray and a place to get a breath of fresh air; in short, the conditions on board are exactly as those on shore. The service on board is performed through Muslims themselves, which undoubtedly will please each passenger. The provisions and all the work generally will follow Muslim law, while all regulations on board will strike all as contributing to the overall pleasure of all passengers … all Muslim brothers know our duties as Muslims towards people who have a pure purpose.Footnote 148

Many local Islamic newspapers were more outspoken in their criticisms of Kongsi Tiga, which, they argued, created inhospitable living conditions for Muslim passengers. Kongsi Tiga was accused of packing pilgrims onto ships like “herrings in a tin” and of treating pilgrims exactly the same as contract coolies – it was only due to the insistence of their shaykhs that hajjis and coolies were “no longer mixed together under one roof.”Footnote 149 Additionally, men and women occupied the same spaces on Kongsi Tiga’s ships, as “proscribed by Islamic religion.”Footnote 150 Kongsi Tiga also forbade pilgrims to transport livestock for ritual slaughter in the Hejaz and were accused of denying this to pilgrims because the companies found it “bothersome for the fellow passengers” and claimed it was “within their rights to forbid such transport.”Footnote 151

The most damning accusations against Kongsi Tiga targeted Dutch capitalist greed and the economic profits achieved through the exploitation of Indonesian Muslims. While Muhammadiyah attempted to raise ƒ500,000 in capital to charter its pilgrim ships, Kongsi Tiga earned millions of guilders in profits every year (Figure 1.3) and was accused of only being concerned with “raking in the money.” Nationalism played into perceptions of hajji suffering at the hands of greedy Dutch shipowners:

[T]housands roll from our pockets into those of another nation. Most [hajjis] are people from the farming class, who almost every year give their cash to the “money box” of a foreign nation. People save their cents and guilders until eventually they reach an amount sufficient to cover the costs of hajj. The saved money, that men have struggled to earn, is now deposited in another man’s pocket … This is a shame, not because the money is given away … but that it winds up in the hands of others.Footnote 152

One of the major goals of Penoeloeng Hadji was to gain control of hajj transport profits in order to reinvest this money into Islamic communities and causes in colonial Indonesia. Making the hajj easier on pilgrims in terms of comfort, spiritual fulfillment, and economic accessibility, PH hoped indigenous shipping would alleviate many pilgrim hardships, including the large number of hajjis who “brought money with them [on hajj] and returned with debts.”Footnote 153

Kongsi Tiga initially believed Muhammadiyah’s attempts would dissolve by themselves without interference by Dutch authorities and expected “not much would come of it.”Footnote 154 Despite Kongsi Tiga’s assumption that PH’s plans would have “little success,” it could not “altogether ignore them, as there is a possibility that by chartering ships of foreign companies the native organizations might succeed in offering a competing transport opportunity.”Footnote 155 What swayed the Trio’s attitude was the loss of fares at the beginning of the 1931–32 hajj season. Internal memos noted “a number of pilgrims have adopted a wait and see attitude” about the outcome of PH’s endeavor and were, therefore, not purchasing pilgrim fares on Kongsi Tiga ships. Loss of revenue gave the Kongsi Tiga cause to consider to “what extent this competing business was driven by idealism among the natives.” Kongsi Tiga predicted this idealism would eventually leave pilgrims with nothing and that Penoeloeng Hadji would

inevitably cause all kinds of inaccurate messages to be sent into the world, with the result that the prospective pilgrims, through false illusions, would at first hope for the arrival of a ship that will fulfill all religious demands and be much cheaper than the Kongsi Tiga. In short, that people shall instantaneously travel perfectly. In the meantime, the first ships of the bona-fide Companies would leave empty, or partially occupied, while the pilgrims continue to wait until it grieves them and they meanwhile become greatly duped.Footnote 156