The unexpected death of the dictator Sani Abacha in June 1998 ended a long reign of dictatorships that began on New Year’s Eve 1983, when then-General Muhammadu Buhari (now president) staged a coup that ended the short-lived Second Republic. It also set in motion the nation’s most successful transition, climaxing when Olusegun Obasanjo took the oath of office as an elected president in May 1999. The transition was remarkable not only for its successful transfer of power, but for its swiftness. Within a year, a Provisional Ruling Council (PRC) released dissidents from jail, removed state military administrators, oversaw the formation of new political parties, promulgated a constitution, and organized elections at the local, state, and federal levels. Nigerians had learned from past mistakes; the elaborate plans of Ibrahim Babangida’s dictatorship (1985–1993) to hand over power had amounted to no more than a theater of consultation. The process became known as a “transition without end” (Diamond, Oyediran, et al. Reference Diamond, Oyediran and Kirk-Greene1997). Abacha’s transition plans followed an even more dubious commitment to the transfer of power. When five political parties formed, they all endorsed him as their presidential candidate. “You can put up anybody you like. But the presidential candidate is me” he told one such party, the Coalition for National Consensus (Aminu Reference Aminu2010). “The pro-Abacha campaigners seem to be living in a world of illusion,” another party official recalled Abacha saying. “They have embarked on a massive propaganda campaign that implies that the transition programme is not a reality but a ploy to perpetuate the military in power” (Constitutional Rights Project 1998d, 22).

By definition, transitions involve a formal transfer of power from one regime to another, with “regime” referring to the rules of governance and not just the individuals occupying office (LeVan Reference LeVan2015a). There is a long debate over what causes transitions and a large literature on what makes them successful, with some recent research emphasizing that transitions do not necessarily mean a transfer of power to democracy. There is also a debate over whether change comes from below, through grassroots pressure, or from above through “pacts” resulting from elite negotiations over the terms of the transition. Such pacts bring together major stakeholders to establish new rules of governance and a route to get there by offering mutual guarantees (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter, O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986c; Colomer Reference Colomer1994). Civil society organizations and other actors often weigh in on these deals but “pacting” is an inherently undemocratic process (Karl Reference Karl1990). Our understanding about when transitions end is more limited, and it largely derives from research on democratic “consolidation” (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996), a term that remains common despite its association with optimistic assumptions about the linear direction of regime change and other flaws (Carothers Reference Carothers2002; Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Fukuyama, Horowitz and Plattner2014b).

In this chapter, I outline the key terms of Nigeria’s transition negotiated by elites. These deals provided members of the outgoing military junta a smooth exit, resolved the legacies of the aborted transition in 1993, and explicitly but informally established some criteria for competition among politicians. Nigeria’s pact facilitated a successful transfer of power to democracy and helped hold the ruling party together for sixteen years. I do not attempt to provide a comprehensive historical overview of political events during this period. Instead, I describe the declining political saliency of the transition’s pact from shocks that fractured the PDP and facilitated the country’s first party turnover with the defeat of an incumbent political party in 2015. I argue that this turnover formally ended the transition. But weakening the pact also generated new uncertainties about Nigeria’s political institutions; the conditions for successful democracy will differ in important ways from the terms of a successful transition. I highlight these problematic conditions later in the book.

First, I review existing literature that provides the analytical tools for assessing the political meaning of the PDP’s defeat in 2015 as a political juncture in relation to the military’s exit in 1999. This discussion places Nigeria’s transition within a comparative understanding of democratic struggles in Africa since the 1990s and in the Arab world since 2011. I also compare different thresholds for when transitions end, elaborate on the conceptual meaning of “pact,” and explain why we should consider 1999 Nigeria’s only successful transition.

Second, I detail the terms of the transition. With Abacha dead, the regime quickly picked someone to shepherd the process. Once liberal reformers successfully pushed the interim head of government to abandon core elements of Abacha’s transition plans, the PRC settled on several compromises with the military, including professional rewards that provided opportunities for career advancement, no consequences for looting government money, and impunity for human rights violations. Importantly, these exit guarantees in the PRC’s pact with the outgoing military regime overlapped with the founding principles of the PDP, which went on to win the presidency, control of the National Assembly, and most of the governorships in the transitional elections.

In the third section, I identify an informal agreement within the PDP to alternate the presidency between north and south known as “power shift,” rotate offices to different parts of the country through “zoning,” and an understanding that its first presidential candidate had to be a Yoruba, the dominant ethnic group in the southwest. Yorubas harbored lingering resentment from the annulled 1993 Election, and from a 1979 Presidential Election narrowly decided by the Supreme Court. Once in power, President Olusegun Obasanjo embarked on a wave of firings and forced retirements in the military. However, rather than holding the generals accountable for human rights violations or making public the truth of their many abuses, the PDP generated new career paths in the party and in the private sector for those who left the military. For those who stayed in the military, the party embraced a policy of “coup proofing” with a massive increase in military spending and a little-noticed wave of promotions at the end of Obasanjo’s first term. In sum, the outgoing military found itself with ample exit guarantees. And by adopting founding principles congruent with the PRC’s pact, the PDP extended and embraced the basis of the transition, ruling for the next sixteen years.

Fourth, I demonstrate how elite rivalry and grassroots democratic pressure weakened the pact, creating new political space for rise of the opposition All Progressives Congress. I provide evidence of a generational shift that put the PDP out of touch with an increasingly youthful nation. More importantly, I detail how principles of rotating power tore the ruling party apart. Power shift and zoning weakened links with voters, who were unable to reelect well-performing politicians rendered ineligible for office by virtue of their ethnicity. Power shift and zoning also suffocated ambitious politicians, whose annoyances with the party’s disciplinary measures led to mass defections to the APC in 2013, shortly after its formation. The conclusion mentions how the legacies of the transition affect contemporary politics. As a new generation looks beyond the milestone of electoral turnover in 2015, it must grapple with the ghosts of Nigeria’s transition and distinguish its elite pact from the vision of a vibrant democracy powered by participation and accountability.

Literature Review on Transitions

A seminal study by O’Donnell and Schmitter (Reference O’Donnell and Schmitter1986a) defines transitions as the interval between one political regime and another, where “regime” refers to a set of rules for deciding who governs, how to allocate resources, and how to limit state power. Transitions often emerge from liberalization reforms by an incumbent regime that extend civil and political rights, protecting groups and individuals from state abuses. In this conceptualization, democratization more broadly refers to a process whereby the incumbent regime loses its hold on power and a new regime takes shape. For O’Donnell and Schmitter, transitions are thus discrete political processes that outline the roadmap for changing the underlying rules of politics. Transitions fix the boundaries of debate during this period, often by placing certain issues off the table. They also define the actors eligible to participate in post-transition politics and specify their roles in the new system.

In Latin America and Southern Europe during the 1970s and 1980s, change came “from above” as elites divided over questions of political liberalization resolved their differences. In these classic models, transitions resulted from compromises between “hardliners” who support the old regime or “softliners” who favor democratization (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter, O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986c), while their allies outside the regime are “radicals” and “reformers,” respectively (Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991). When these various forces see the costs of democratization as lower than the costs of the status quo, they seek mutual reassurances through a pact. For example, in Chile, supporters and opponents of democratic reforms within the military junta formalized an agreement that gave the exiting dictator and his supporters a guaranteed presence in the Senate, while at the same time embarking on multiparty electoral competition and launching a truth commission (Barros Reference Barros2002). Brazil attempted a similar “controlled” and gradual democratic opening negotiated by elites, including the military retaining control of its own military promotions (Huntington Reference Huntington1991). Spain’s elites exercised less control over the transition but conservatives still protected their interests, and the former authoritarian regime continued to enjoy sympathy after its exit (Colomer Reference Colomer1994). An alternative conceptualization of pacts suggests that they are not necessarily the distinct and delimited historical moments. Higley and Gunter define a pact as “less sudden than an elite settlement, this process is a series of deliberate, tactical decisions by rival elites that have the cumulative effect, over perhaps a generation, of creating elite consensual unity” (Higley and Gunther Reference Higley and Gunther1992, xi). Thus, rather than arriving at a mutually beneficial understanding about how to govern in a single stroke, elite agreements in their view emerge from an iterative process, opening up the possibility – or necessity – to renegotiate the terms of governance.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 ushered in a vast expansion of electoral democracy around the world that seemed to render pacts less relevant. The post-Cold War transitions differed from the patterns and generalizations in at least four ways. First, proponents of modernization theory had long argued since the 1950s that certain preconditions were necessary for democratization. One variant claimed that democracy required a shift in cultural mindset (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963), and that this is difficult in countries that have not reached certain socio-economic thresholds (Lipset Reference Lipset1959). By the 1990s was it clear that poor countries could successfully transition to democracy, even if they had trouble staying democratic (Przeworski et al. Reference Przeworski, Alvarez, Cheibub and Limongi2000). Second, transitions from Africa and the former Soviet Union provided compelling evidence that grassroots pressure “from below,” rather than pacting “from above,” led to democratization. Popular protest, labor movements, and mass-based guerrilla organizations fought for democracy (Bratton and Van de Walle Reference Bratton1997; Bunce Reference Bunce2003; Wood Reference Wood2000). Third, Huntington and others, hung up on modernization theory’s assumptions about a unidirectional march toward Western-style democracy (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama1992), assumed that few “intermediate” regimes would emerge (Huntington Reference Huntington1991). By the early 2000s though, democratic “backsliding” made clear that many regime transitions were not transitions to democracy. Many were in fact transitions from democracy to authoritarianism, or from one type of authoritarian regime to another (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009). Many regimes were not merely temporary setbacks in a hopeful democratization process; they constituted “electoral authoritarian” (Schedler Reference Schedler2006), semi-authoritarian (Ottaway Reference Ottaway2003), or hybrid (Tripp Reference Tripp2010) regimes that proved resourceful and resilient.

The pacting model has retained relevance, even if it originally possessed a crude over-determinism. In Africa, different modalities of multiparty competition in some two-dozen countries today have roots in elite deals struck in the early moments of their respective transitions as exiting autocrats sought reassurance (Riedl Reference Riedl2014). In the Middle East, evidence from the Arab Spring suggests that the democratic revolutions initiated by popular protest arguably failed in every country except Tunisia (Brownlee et al. Reference Brownlee, Masoud and Reynolds2015; Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Fukuyama, Horowitz and Plattner2014a). Across the region, new “ruling bargains” have preserved elite deals and limited political reforms (Kamrava Reference Kamrava2014). Finally, pacting has been utilized as a tool for analyzing phenomena other than democratization, such as constitutional reform processes (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017). Comparative research often seeks to interact the structure of politics with the elite agency implied by pacts, for example, demonstrating that many transitions are trigged by distributive gaps rather than mere levels of development suggested by modernization theory (Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard2016).

The term transition has retained its relevance too, even as the large number of countries at the turn of the century to which it was applied (arguably up to 100) highlights the concept’s fuzziness. Not only did many countries deviate from the theorized sequence of political opening (liberalization), democratic “breakthrough” and then consolidation (Carothers Reference Carothers2002), where democratic roots did take hold, identifying the end of a transition remained murky. One solution is to establish minimum conditions, such as a successful “founding election” organized by the transitional government or simply the successful transfer of power from one regime to the next (Bratton Reference Bratton, Diamond and Plattner1999). A slightly higher threshold is one where the new regime successfully organizes its first free and fair election. This task entails implementation of the new regime’s institutions (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell, Diamond, Plattner, Chu and Tien1997).

Most analyses adopt a higher threshold whereby free and fair elections are a necessary but insufficient condition for ending a transition; the government in question must also, for example, exercise both de jure and de facto powers over policy-making (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz, Stepan, Diamond, Plattner, Chu and Tien1997). “A democratic transition is completed only when the freely elected government has full authority to generate new policies,” writes Larry Diamond, “and thus when the executive, legislative and judicial powers generated by the new democracy are not constrained or compelled by law to share power with other actors, such as the military” (Diamond Reference Diamond, Diamond, Plattner, Chu and Tien1997, xix). This constituted a corrective for important cases where pacts protected old regime elites, and generally allowed for very limited civilian control over the military. As already noted, the military in Chile retained significant control over policy throughout the 1980s. Burma’s constitution, promulgated during the transition, enshrines significant protections and policy authority for the military; this pact enabled the transition but is now holding back democracy (Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Fukuyama, Horowitz and Plattner2014a). In Ecuador, the military stipulated the transition would take no less than three years. While on its way out, the generals secured obtuse candidacy requirements, including one that eliminated the previous incumbent. And in Peru, the military controlled ministerial appointments concerning military affairs. In general, in Latin America’s transitions from the 1960s through the 1980s, the military “endeavored, to the best of their ability, to fix the subsequent rules of the game” and seek “a permanent right to supervise ensuing political decisions” (Rouquie Reference Rouquie, O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986, 121).

This literature on transitions, pacting, and exit guarantees relates to this book’s analysis of Nigeria in several ways. For starters, Nigeria has experienced at least three political processes that qualify as a transition. Decolonization could count as the first transition. After World War II, Nigeria followed a calculated process gradually expanding the franchise, legislative powers, and indigenous control over economic resources (Suberu Reference Suberu2001). Once the nationalists won the day, federal elections in 1959 led up to independence in 1960, and then graduation to status as a full republic in 1963. Tragically, over the next three years the new nation witnessed ethnic pogroms, electoral violence, a declaration of a State of Emergency, and finally its first coup d’etat in 1966 (Diamond Reference Diamond1988). By June 1967, the country had descended into a full-scale civil war that killed over a million people. The second transition began in 1975 with Murtala Muhammed’s coup, overthrowing the military regime of Yakubu Gowon. Gowon had abandoned his transition plans in 1974, alarming moderates in the regime and infuriating politicians from the First Republic who planned to contest. From Gowon’s perspective, elites (notably Obafemi Awolowo) “started really doing things that were a repeat of the first crisis we had in 1965,” by stoking the kind of paranoia that led to the first coup (Gowon Reference Gowon2010). The transition process carried out by Muhammed and his successor entailed drafting a new constitution, which included a delicate compromise on Islamic law and the formation of new parties, and culminated with elections that swore in Shehu Shagari as president in October 1979 (Laitin Reference Laitin1982). But that democratic regime also fell prey to a coup after suffering a violent Islamic rebellion in the north, the collapse of a fragile coalition government, and elections in 1983 that degenerated into riots (Falola and Ihonvbere Reference Falola and Ihonvbere1985; Diamond Reference Diamond1984).

The establishment of both the First (1960–1966) and Second (1979–1983) Republics involved liberalization, the formation of new parties, and the promulgation of a new constitution (Odinkalu Reference Odinkalu, Amuwo, Bach and Lebeau2001). But beyond the organization of a founding election, neither of them satisfied the criteria for a complete transition according to the literature. The 1998/1999 process could therefore be viewed as Nigeria’s only completed transition. The pact between the Provisional Ruling Council, which oversaw the transition, reduced the military’s fear of exit and shaped political competition. “Although the country did succeed in shifting peacefully from military to civilian rule, this was the result of a pact among leaders seeking to maintain their power and privileges inside an ostensibly democratic structure. The broader society was hardly involved,” says one analysis (Coleman and Lawson-Remer Reference Coleman, Lawson-Remer, Coleman and Lawson-Remer2013, 9). “The elites – not a middle class or the poor – orchestrated the 1998–99 transition from military to civilian rule and were the beneficiaries of the new regime, as they had been of the previous one,” says a study by the former US Ambassador to Nigeria (Campbell Reference Campbell, Coleman and Lawson-Remer2013b, 210). The 1999 pact is also important because rather than evolving, as Higly and Gunter anticipate, it decayed.

In the next section, I outline the broader political circumstances following the death of the dictator Sani Abacha, and dive into detail about the terms of the pact. Nigeria’s military lacked the sort of veto authority obtained by the generals in some of the cases mentioned above. But they did enjoy an unofficial immunity and continued to exercise considerable influence over politics through a visible presence in the People’s Democratic Party. Keeping the military content imposed both economic and political costs on the new democracy. It was not until the PDP’s ability to uphold this pact began wavering that the elite basis of the transition’s successful transfer of power became evident. Thus, rather than ending in 1999 with the founding elections, or in 2003 with the first elections organized by the new regime, I pinpoint the end of the transition later than the literature would suggest: in 2015 with the electoral defeat of the ruling PDP.

A Dictator’s Demise and a Swift Transition

Nigeria’s last dictatorship began when Sani Abacha took the reins of government in August 1993, after three tumultuous months of unrest precipitated by Ibrahim Babangida’s annulment of the June 12 election. Unofficial results showed Moshood Abiola, a Yoruba from the southwest, had won (Omoruyi Reference Omoruyi1999; Suberu Reference Suberu, Diamond, Kirk-Greene and Oyediran1997). This victory worried northern elites and military officers who had dominated politics since 1960 (Osaghae Reference Osaghae1998); his substantial wealth also provided him with a measure of independence from this ruling coalition (Okoye Reference Okoye, Daniel, Southall and Szeftel1999). Abacha’s initial government included a broad cross-section of political elites, including some impacted by the annulled election. At the same time, he also dismissed Babangida’s allies, known as the “IBB Boys,” from the cabinet and he later systematically purged them from government (Amuwo Reference Amuwo, Amuwo, Bach and Lebeau2001; LeVan Reference LeVan2015a). Babangida’s decision to “step aside” thus bore close resemblance to a bloodless coup.

Abacha’s coalition government did little to ease tensions within the regime regarding how to handle the aborted transition, the blame for which stood on the shoulders of Babangida and hardliners in his government suspicious of handing over power to a Yoruba. “We were selfish and without foresight,” recalls a National Republican Convention (NRC) member of the National Assembly at the time. Like others, he aligned with the military out of fear of a southern president (Wada Reference Wada2004). Another NRC party leader put it this way: “The north dominated the military and they were afraid he [Abiola] was going to clean out the army. The army is their compensation for the 1966 coup” (Ebri Reference Ebri2010). Abiola fled abroad and declared himself the winner; upon his return to Nigeria he immediately found himself in prison. This further complicated the basic issues at stake in any transition. Not only did Abacha’s government need to chart a course for political reform after discarding Babangida’s elaborate program, it needed to decide whether it would honor the 1993 election results. Divisions within the pro-democracy movement worked in favor of a transition by procrastination. Civil society organizations such as the National Democratic Coalition, the Campaign for Democracy, and the Nigeria Labour Congress broadly united around opposition to the military. But they disagreed about the role of external assistance, protest tactics, and most importantly whether a transition plan should honor the June 12 election results or call for new elections (Edozie Reference Edozie2002; Akinterinwa Reference Akinterinwa, Diamond, Oyediran and Kirk-Greene1997; LeVan Reference LeVan2011b).

In 1997, Abacha’s tight grip on power weakened as several factors worked in favor of the pro-democracy movement and moderates within the military. In particular, his decision to run for president openly clashed with the expectation that he would not participate in elections he was responsible for organizing. His ambitions seemed to receive a blessing from President Bill Clinton though. During a visit to South Africa, Clinton said of Abacha, “If he stands for election, we hope he will stand as a civilian. There are many military leaders who have taken over chaotic situations in African countries, but have moved toward democracy. And that can happen in Nigeria; that is, purely and simply, what we want to happen” (Clinton Reference Clinton1998). Abacha bragged to his cabinet, “All these pro-democracy activists run to America to save them. But the US president is himself calling me ‘sir.’ He is scared of me” (Cohen Reference Cohen2009).

The pro-democracy movement felt deeply betrayed by Clinton’s comments, and the media continued to skewer Abacha for his “self-succession” bid (Amuwo Reference Amuwo, Amuwo, Bach and Lebeau2001; Constitutional Rights Project 1998d). But more importantly, the self-succession campaign forever cast Abacha’s commitment to a transition in a dubious light. Barely a month after President Clinton’s comments, the US State Department in April 1998 changed course, declaring, “The current transition process appears to be gravely flawed and failing. We do not see how the process, as it is now unfolding, will lead to a democratic government” (Constitutional Rights Project 1998b, 8). Pope John Paul II, during a visit to Abuja in March, called for the release of all political prisoners. “The world was becoming increasingly impatient with military administrations in developing countries, especially in Africa,” recalls a state governor (Ikpeazu Reference Ikpeazu2017). Domestic opposition also mounted as thirty-four prominent politicians, led by the Second Republic’s vice president, known as G34 (or the “Group of Patriotic Nigerian Citizens”) condemned the five parties’ endorsement of Abacha (Badejo Reference Badejo, Diamond, Kirk-Greene and Oyediran1997; Constitutional Rights Project 1998b). “It had to be cloak and dagger,” explained a member; “you would send your driver to an intermediary who would tell you where to go, and who could therefore alert the others if the military showed up” (Aminu Reference Aminu2010). In effect, Abacha’s refusal to exit contributed to the opposition’s unity, enabling it to focus on obtaining a transition to civilian rule rather than resolving the June 12 question.

Abacha also seemed to overreach with a crackdown on an alleged coup plot in December 1997. A Special Investigation Board interrogated 144 persons, more than half of whom were detained in connection with the investigation. The arrests included Lieutenant-General Oladipo Diya, a prominent Yoruba moderate within the regime sympathetic to the June 12 cause. But the Chief of Army Staff, Major-General Ishaya Bamaiyi, who had supposedly proposed the coup to Diya, was absent. Pro-democracy organizations and others saw this as compelling circumstantial evidence of a set-up by Abacha to eliminate critics of his self-succession plans (Constitutional Rights Project 1998a). Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, who was Obasanjo’s second-in-command during the 1970s (and brother of the president elected in 2007), died in prison that same month. Activists maintained that he had been denied medical care because Abacha had wanted to get rid of him ever since he had warned the constitutional conveners in 1994 that the regime did not intend to carry through with the transition (French Reference French1998). Amuwo (Reference Amuwo, Amuwo, Bach and Lebeau2001) cites a secret memo calling for his elimination due to Yar’Adua’s opposition to the self-succession plan.

The Provisional Ruling Council dealt with the question of succession immediately following Abacha’s death, most likely by assassination. Lieutenant-General Jerry Useni, a minister with Abacha at the time of his death, emerged as one possible successor. He claims the PRC did not pick him due to protocol (Abdallah and Machika Reference Abdallah and Machika2009). This makes little sense, though, since he was next in command. Other information points to Abacha’s widow quickly intervening to oppose Useni. She brought Babangida to the presidential villa to weigh in and deployed Hamza Al-Mustapha, Abacha’s notorious security chief, to physically block Useni, who was known as a hardliner. Useni had also previously shown interest in joining party politics, which could lead to a repeat of the self-sucession problem – a dictator seeking to transform himself into a civilian politician through elections (Niboro Reference Niboro1998).

After a brief meeting in Kano, the PRC quickly settled on General Abdulsalam Abubakar. Muddling his fresh start, his opening speech declared “we remain fully committed to the socio-political transition programme of General Sani Abacha’s administration and will do everything to ensure its full and successful implementation” (Abubakar Reference Abubakar1998a, 14). Like other civil society groups, the Constitutional Rights Project (CRP) immediately criticized the interim administration’s commitment to Abacha’s transition program. “Clearly, what is needed at this time is for all the political parties to be dissolved, the sham elections conducted so far, set aside, new and independent parties allowed to form” (Constitutional Rights Project 1998c, 5). The National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), the G34, and various elites called for a government of national unity (GNU). But even this was difficult to envision since the existing five parties had thoroughly discredited themselves by previously endorsing Abacha (Niboro Reference Niboro1998). Picking a successor to Abacha who could lead the transition settled a big question. But the status of the parties, the possibility of a GNU, and what to do about the annulled June 12 election were even thornier. The sudden death of Abiola (the election’s apparent winner) while still in prison softened this difficult dilemma. Up until then, Abubakar’s position was by no means clear; he had met with foreign officials to urge them to abandon the international community’s insistence on honoring the June 12 election results (Olowolabi Reference Olowolabi1998b).Footnote 1

Abubakar quickly advanced a comprehensive vision for the transition that jettisoned his initial commitment to Abacha’s plan and that took a step toward resolving June 12 and Abiola’s future. In a speech entitled “The Way Forward,” he declared that “cancellation of the flawed transition programme which we inherited is necessary to ensure that we have a true and lasting democracy as demanded by the majority of our people” (Abubakar Reference Abubakar1998b, 13). He promised to release all political detainees and withdraw pending political charges. He dissolved the political parties and said, “every Nigerian citizen has equal opportunity to form or join any political party,” in line with guidelines to be determined by a new, civilian electoral commission. This eliminated the idea of a GNU whose “composition could only be through selection that would be undemocratic,” he explained in reference to the Abacha parties. “We will not substitute one undemocratic institution for another” (Abubakar Reference Abubakar1998b, 14).

With the GNU off the table, the question of June 12 still lingered, even with Abiola’s death. Opposition to honoring the June 12 mandate with a Yoruba presidency was not limited to conservative northerners such as the Sultan of Sokoto. Many Igbos, including Abacha’s Secretary for Education, Ben Nwabueze, and Secretary for Information, Uche Chukwumerije, wanted to neutralize the influence of the Yoruba (Omoruyi Reference Omoruyi1999). One of Abacha’s military governors pointed out that some Igbos in the east also shared resentment for Yorubas not enabling the eastern secession attempt through the civil war from 1967 to 1970 (Nmodu Reference Nmodu1998). Abubakar said of the annulment and massive protests, “we cannot pretend that they did not happen,” but he also urged the country to not dwell in the past (Abubakar Reference Abubakar1998b). This announcement committed Abubakar to a punctual transition schedule that increased his credibility with the pro-democracy movement.

Abubakar also delivered on the promise of a new constitution, though it had virtually no public participation (Eisenstadt et al. Reference Eisenstadt, Carl LeVan and Maboudi2017). In November 1998, he introduced a drafting committee. By the following month it had submitted its report, which supposedly reflected ideas from 405 memoranda (Ojo Reference Ojo, Agbaje, Diamond and Onwudiwe2004). However, the PRC could not prevent the security services from repeatedly injecting themselves into the constitution-making process. For example, according to a former governor, they screened political candidates (Ebri Reference Ebri2010). Even more poignantly, the PDP’s Secretary General later said in an interview that the military vetoed constitutional provisions – supported by Abubakar – to limit the president to one term and rotate the office among six geopolitical zones (Nwodo Reference Nwodo2010). The promulgation of the constitution just a few weeks before the handover of power on May 29, 1999 kept the transition on track. But it offered few illusions of public input despite long, hard popular struggles for democracy.

The transition elections also proceeded as promised, but they clearly reinforce the interpretation of the transition as orchestrated from above by beneficiaries of the pact. The first set of elections took place across Nigeria’s 774 local governments in December 1998, which was intended to help the new parties build up a grassroots base and also to qualify parties for higher-level elections.Footnote 2 Gubernatorial and State Assembly elections took place in January 1999, followed by National Assembly elections on February 20 and the Presidential Election on February 27. These processes whittled down the playing field from nine parties competing in the local elections to three parties at the state and federal level. The PDP’s candidate, former dictator Obasanjo, prevailed over Olu Falae, a joint candidate of the southwest-based Alliance for Democracy (AD) and the All Peoples Party (APP) by a margin of 18 million to 11 million votes. When Chief Falae immediately called the entire process “a farce” and announced his intention to appeal, an international election observation mission led by the former US President Jimmy Carter revised its previous statement characterizing the electoral process as flawed but acceptable. After additional analysis from field observers, Carter now castigated the “wide disparity between the number of voters observed at the polling stations and the final results that have been reported from several states. Regrettably, therefore, it is not possible for us to make an accurate judgment about the outcome of the presidential election” (Carter Center and National Democratic Institute for International Affairs 1999, 11–12). After convincing Falae to take his appeals to the courts, the final joint report with the Washington-based National Democratic Institute concluded that the low quality of the elections cast doubt upon the integrity of the process overall and therefore the legitimacy of those elected. The report praised Abubakar for his role but also downplayed his influence, noting “from the onset, a compressed timetable and top-down structure controlled by the very military officials it intended to replace affected the process” (Carter Center and National Democratic Institute for International Affairs 1999, 32). Reinforcing the profoundly undemocratic features of the transition, one human rights group complained that the military decrees governing the process were nowhere to be found – even after the elections (Legal Defence Centre 2000).

The transition also proved largely beyond Abubakar’s control when it came to delivering on his promises to release pro-democracy activists or to rein in hardliners such as Jerry UseniFootnote 3 and Abacha’s Chief Security Officer, Hamza Al-Mustapha. More than three months after the “Way Forward” speech, Abubakar had yet to release most of the 291 political prisoners, including moderates such as General Diya. The Constitutional Rights Project (CRP) asserted that Abubakar “may in fact, not really be in control of the government” (Constitutional Rights Project 1998e). “If there’s one thing Abubakar still has to do, it is to quash the proceedings of the trial of Obasanjo, Diya and co. Declare them a nullity” said a former military governor (Nmodu Reference Nmodu1998, 35). At a press conference in Lagos, Abubakar repeated many of his promises. But since he had not yet delivered on them, the press greeted the statements with cynicism (Olowolabi Reference Olowolabi1998a). Abubakar did not pardon Obasanjo until September 30 (Godwin Reference Godwin2013) and Diya remained in prison until 1999.Footnote 4

Bargaining for Democracy: Civilian Concessions and Military Demands

The peaceful transition of power from military generals to civilian elites on May 29, 1999 came at the cost of transparency, accountability, and legitimacy from a public largely cut out of the process. This was by design, often despite Abubakar’s best efforts. He put in place provisions that prevented members of the security services (as well as traditional rulers) from belonging to a political party. However, the military did obtain commitments to ease the generals’ departure and pave the way for lasting influence after the handover to civilians. Retired military generals argued their case for such guarantees at a meeting with Abubakar in October 1998. The meeting included former heads of state Yakubu Gowon and Ibrahim Babangida, as well as Theophilus Danjuma and Murtala Nyako, wealthy retirees who became major power players in the PDP. Obasanjo did not attend, mostly likely because he had by then signaled his interest in running for president (Adekanye Reference Adekanye1999).

Three essential compromises emerged from the military’s meeting with Abubakar that would form the basis of an elite pact. One involved the promotion of prominent (and controversial) Abacha loyalists. The transitional government promoted Zakari Biu, who as Assistant Police Commissioner led a security unit that tortured Abacha’s opponents; he became chair of the lucrative Federal Petroleum Monitoring Unit (Adeyemo Reference Adeyemo1999). He was forcibly retired after the transition, then reinstated and fired twice (including once for an incident where he was accused of assisting a Boko Haram escapee) before being reinstated for an honorary retirement in September 2015 (Obi Reference Obi2015). In the early weeks of the transition, in 1998, CRP complained about the “juicy military appointments” of General Bamaiyi, who had allegedly entrapped Diya, as well as other hardliners such as Abacha’s Chief Security Officer, Al Mustapha, and Major General Patrick Aziza (Constitutional Rights Project 1998e). Another human rights group also complained about the promotions, adding that forty-three “obnoxious” military decrees remained on the books, including one (Decree No. 2) that gave the PRC the power to jail opponents, though Abubakar may have retained it in order to check the hardliners (Adeyemo Reference Adeyemo1999).

Abubakar’s reluctance to intercept or expose money stolen by Abacha and his family amounted to a second compromise with the exiting military. By January 1999, the transitional PRC had recovered over 60 billion naira (approximately US$690 million) from the former dictator. But when investigators interrogated Abacha’s powerful National Security Adviser, Ismaila Gwarzo, they released him; Abubakar said he should not be held liable for taking orders from his boss. Then Abacha’s finance minister, trying to position himself for electoral politics, attempted to take credit for informing on Gwarzo (Adeyemo Reference Adeyemo1999). The disclosures of stolen money infuriated ethnic Ijaws just as they were starting to drift toward militancy in the Niger Delta (Umanah Reference Umanah1999). Much of “Abacha’s loot” is still in the process of being discovered and recovered. In 2014 for example, the US Department of Justice announced a forfeiture of US$480 million from banks around the world where Abacha stashed his money (US Department of Justice 2014).

A third compromise with the military concerned the transition government’s approach to human rights violations under previous military regimes. Around March 1999, as the handover neared, Abubakar was being squeezed on one side by softliners such as Mike Okhai Akhigbe, Chief of General Staff, who insisted that transition proceed, and on the other side by hardliners such as Bamaiyi who thought the incoming civilian administration should make the decision about Diya’s fate. As Abubakar managed these two factions, regime softliners possibly contemplated a palace coup against Abubakar in order to keep the transition on track (Ayonote Reference Ayonote1999). They also wanted the transitional government to get credit for doing right by Diya. The softliner argument won out and politicians from president-elect Obasanjo’s party, who were meeting at an Abuja hotel, greeted Diya’s release with “jubilation” (Agekameh Reference Agekameh1999). Around the same time, the top candidate for spearheading a human rights panel died. Tunde Idiagbon, the feared deputy of Muhammadu Buhari during the short-lived dictatorship (1984–1985), had stayed out of politics since 1985. Abubakar’s National Security Adviser, who was from the same town, summoned him to Abuja. He died immediately after returning home of suspicious symptoms, precipitating theories that hawks in the junta had dispatched him to prevent a powerful military figure from overseeing any investigations into human rights violations by the military (Mumuni Reference Mumuni1999; Semenitari Reference Semenitari1999).Footnote 5 In the final weeks before the handover, the regime also decided not to move forward with prosecution of the dreaded security chief Al-Mustapha, in military detention, leaving such a tough choice for the incoming civilians.Footnote 6 The reformers were released from prison, while Abacha’s hardliners eventually got off the hook.

The People’s Democratic Party unfolds a “Big Umbrella”

The exit guarantees regarding career advancement, tepid anti-corruption measures, and impunity for human rights violations constituted the core features of the pact agreed upon by Abubakar and the military. In this context, a new generation of elites joined what was left of the old-guard democrats (after all, nearly seventeen years had passed since the end of the Second Republic) to form new parties. The INEC ban on members of the military or security services from joining parties meant that many officers, who had seen the military as a route to politics for at least a generation, now had to resign in order to follow such a path. The PDP’s umbrella logo offered an apt metaphor for the moment, welcoming many former military officers. The idea, says a PDP governor, was to “conglomerate ideas and politicians in one boat so that they were able to present a front that was capable of receiving power from the military administration” (Ikpeazu Reference Ikpeazu2017). For PDP elites, inclusion thus meant not just the usual ideas of ethnic representation but also a military that could be happy in the barracks. “Unless you convince the military that it is a credible arrangement,” recalls a PDP founder, “they might not go” (Aminu Reference Aminu2010). The principles that brought the party together shared a congruence with the Abubakar’s compromises, thus extending and operationalizing the transition’s pact.

The PDP struck on three founding principles. First, party elites settled on a Yoruba presidential candidate. “Who would represent the dominant class better than a retired General Obasanjo who had engineered the 1979 handover of power to a bourgeois party, the NPN [National Party of Nigeria]?” (Braji Reference Braji2014, 103). Importantly, many Yorubas did not trust Obasanjo for precisely that reason; the presidential contest in 1979 was so close that the Supreme Court decided in favor of the NPN’s presidential candidate from the north, and Obasanjo let it stand (Akinterinwa, Reference Akinterinwa, Diamond, Oyediran and Kirk-Greene1997). Thus, with the nullification of the 1993 election, many Yoruba felt that they had been denied the presidency twice – in 1979 and again in 1993 – generating a “Yoruba debt” (LeVan Reference LeVan2015a). Ironically, this history contributed to northern trust in Obasanjo. Babangida, the former dictator, became influential in the PDP during this period, forming a “military wing” of the party composed of retired officers (Mosadomi Reference Mosadomi2017). This influential voting bloc within the PDP offered decisive support for Obasanjo’s candidacy (Agbaje Reference Agbaje and Adejumobi2010). A politician from the rival All Nigeria People’s Party (ANPP) recalled the military’s insistence on a southwestern candidate went beyond mere meddling. “Politicians had no choice. They had no input. They were formed or sponsored by the military,” says Umar Lamido, later a member of the Gombe State Assembly. “Nobody was going to be given any chance. Except the southwest” (Lamido Reference Lamido2016). Naturally, this meant that primaries mattered little – a flaw in the party that came back to haunt it, as we shall see in the analysis of the elections in Chapter 3 and also with the Igbo secessionist revival explored in Chapter 6.

The party settled on Obasanjo, but only after shoving aside Alex Ekweume, a seasoned Igbo politician who served as Vice President during the Second Republic. One reason appears to be that the military simply did not trust him, according news accounts and PDP leaders who were present (Nnaji Reference Nnaji2017). Demands for “military restructuring” had ranked high on civil society’s agenda once Abacha was gone. Ekueme’s campaign provocatively took out advertisements portraying him as the candidate for “truly civilian rule,” in contrast to Obasanjo, who was merely a “civilianized general” or “the military in babanriga,” meaning civilian robes rather than military uniform (Adekanye Reference Adekanye1999, 196). A founding member of the PDP from the north says that few in the north trusted him (Aminu Reference Aminu2010). The feelings were mutual; several Igbo participants at the PDP convention, which took place in Jos, recall Hausa politicians brazenly telling them to stop campaigning for Ekwueme because the north would never trust him (Emeana et al. Reference Emeana, Chuma and Agbim2017). Even today, Igbos across eastern Nigeria remain widely committed to the perception that northerners in the PDP railroaded their candidate. “Alex Ekueume, who was clearly the frontrunner, suddenly lost his followership on the basis of an agreement to bring Obasanjo back,” says John Nnia Nwodo, President-General of Ohanaeze Ndigbo, the pan-Igbo organization. “The basis for it was a necessity to contain the dismemberment of Nigeria on account of Western Nigeria’s dissatisfaction with the handling of Abiola’s election annulment.” Ekueme became “easy prey to sacrifice” (Nwodo Reference Nwodo2017).

A second founding principle of the PDP was an agreement known as “power shift.” In order to reassure northern elites, the party agreed to alternate the presidency between the north and south every eight years, after two presidential terms. This was necessary in light of the broad agreement that the 1999 presidential candidate should come from the south. But as a governing principle, it has roots in Nigeria’s underlying geopolitical bargain that emerged from the colonial amalgamation of the north and south in 1914. By the 1950s, as the country prepared for “self-rule,” ensuring a balance of power between north and south became a reality of representative governance (Paden Reference Paden, Beckett and Young1997). Quotas and efforts to ensure representation of other major geographical differences then became important following the Civil War, when, after the Igbos’ failed war of secession, the dictatorship of Yakubu Gowon initiated policies to reintegrate them back into the military and the civil service (Ekeh Reference Ekeh, Ekeh and Osaghae1989; Afigbo Reference Afigbo, Ekeh and Osaghae1989). This practice of “federal character” is enshrined in the constitution and guarantees some ethnoregional balancing within the cabinet and the civil service – though it has hardly insulated any administration from charges of ethnic bias.Footnote 7

An important difference between ethnic balancing as envisioned through federal character and as practised through zoning (or power shift) is that the latter involves taking turns at power, rather than dividing authority into smaller pieces shared at any given moment of time (Ayoade Reference Ayoade, Ayoade and Akinsanya2013). Zoning emerged from proposals for a rotational presidency during a failed constitutional reform conference in 1995 (Nwala Reference Nwala1997; Akinola Reference Akinola1996). One complication with rotation is that dividing the country into north and south is inadequate if various segments within each region are to have a shot. This led to the idea of six geopolitical “zones” (Sklar et al. Reference Sklar, Onwudiwe and Kew2006). Conceptualizing rotation across six zones rather than two regions meant that if the presidency was limited to one six-year tenure, each zone would have to wait thirty years for its chance to rule. Moreover, a single deviation due to death in office or any variety of reasons would inspire deep mistrust and uncertainty.

Neither the single-term limit nor the division of the country into zones made it into the 1999 Constitution. According to one PDP leader from the north, “What we did is because the constitutional conference of Abacha which accepted the idea of rotation.” Speaking in a 2010 interview, he said “After 2015 or even from 2011, it could be decided by the whole country that we will not be zoning anymore,” but the important thing at the moment is to honor the agreement that exists, even if it alienates many politicians who are “rotated out” of office (Aminu Reference Aminu2010). Rotation causes the same problem at the state level, where the governorship and legislative leadership offices rotate among the constituencies defined by the three senatorial districts. A reduction in the number of units (i.e., from six national zones to three senatorial districts in each state) and hence the time to wait for office does seem to reduce the sense of frustration. And at the local government level, evidence suggests inter-ethnic and inter-religious trust are higher and violence is lower where power-sharing principles are practised, compared to places where they are not (Vinson Reference Vinson2017). All of these practices serve to institutionalize an informal institution and invest political communities at different levels in principles of power shift, power-sharing, and leadership rotation.

Finally, the PDP sought to weaken the military’s appetite and institutional capacity for politics. According to Senator Joseph Waku, the Vice Chair of Arewa Consultative Forum, an organization of northern elites, “both the conservatives and the progressives all agreed to team up for the purposes of assuring the military exit from governance … let’s form a formidable political party that the military will find out is strong, it pulls people together” (Waku Reference Waku2010). Although northerners feared losing control of the military for the first time since Obasanjo’s tenure in the late 1970s, public opinion was on the PDP’s side. A survey found that 62 percent of the nation expressed deep mistrust in the military, concluding that “protracted army rule and the repression and corruption under recent dictatorships has tarnished the image of the military” (Okafor Reference Okafor2000).

The new party began with the imprisonment of hardliner Bamaiyi, breaking with the transitional government’s reluctance to reign him in. He stayed there throughout Obasanjo’s two terms (1999–2007) during an investigation and (ultimately unsuccessful) prosecution for his role in the assassination of a prominent newspaper publisher, Alex Ibru (Sahara Reporters 2008). This seeming progress came at a cost to the pro-democracy movement since his replacement as Army Chief of Staff was Victor Malu, now promoted to Lieutenant-General. The promotion angered the human rights community since Malu had chaired the military tribunal that condemned Diya (the softliner) to death (Agekameh Reference Agekameh2001). Obasanjo’s next steps were more encouraging for pro-democracy activists. Within a month, the government identified more than 100 officers who had served at least six months in any previous military government, and immediately retired them (Siollun Reference Siollun2008). This provided some continuity with the decision by the Independent National Electoral Commission during the transition under Abubakar to ban military participation in politics. Formulating a clear policy with a bright line helped reduce anxiety in the military.

Next came a thinning of the bloated ranks. The swift military growth during the civil war from 10,000 in 1967 to 200,000 in 1970 brought in thousands of unqualified and under-trained soldiers who had few options after the war (Adebanjo Reference Adebanjo2001). Murtala Mohammed and Olusegun Obasanjo made significant cuts from 1975 to 1979 (Gboyega Reference Gboyega, Ekeh and Osaghae1989). “They destroyed the civil service and the military as well as the police,” said their predecessor, General Yakubu Gowon, in retrospect (Gowon Reference Gowon2010). But the military remained large, in part because it had become a route to professional advancement and other careers (Africa Research Bulletin 2000). At the time of the 1999 transition, the armed forces still included at least 80,000 soldiers and officers.

In January 2000, Obasanjo retired 150 air force officers, prompting several northern emirs to urge the National Assembly to intervene to keep their kinsmen in the ranks (Okolo Reference Okolo2000). “The first thing he [Obasanjo] did was fire all the military officers who had held political office,” says a PDP state leader. “He then weakened the power of the north so the military would not belong to any one section of the country” (Olotolo Reference Olotolo2017). Yet, northerners remained palpably nervous throughout Obasanjo’s first tenure. Hausa-Fulani had dominated the military for decades and were nervous about losing it as a lever of power under Obasanjo, a born-again Christian from the southwest (Agekameh Reference Agekameh2002). The purging thus added a strong ethnoregional element to the precarious civilian hold on the military. When Obasanjo met with northern governors in 2000 shortly after twelve states had passed Sharia law, the administration allegedly became concerned that Sharia was really a potential pretext for a coup led by northerners (Agekameh Reference Agekameh2000).

When Obasanjo’s Chief of Air Staff retired thirty-seven more officers in September, ten were singled out for “over ambition” and “plotting to change the present social order” (Okafor Reference Okafor2000, 30). To be effective, Obasanjo had to consider ethnicity, military service, and rank; many officers had acquired influence beyond their rank by accumulating wealth in political positions under previous dictatorships. It was these officers who feared they had the most to lose as civilian government cut off their traditional routes to wealth and status, and who were retired for “over ambition” in January 2001 (Agekameh Reference Agekameh2001). A high-level wave of retirements hit in April when Obasanjo dismissed all three service chiefs. The last straw for Lieutenant-General Malu, after his declaration of faith to the previous military regime, was his public criticism of new bilateral ties between the military and the United States (Africa Research Bulletin 2001).

As it took office, the PDP faced a dilemma between alienating officers who had signaled a willingness to give civilian government another chance and, on the other hand, undermining the credibility of the ongoing transition by angering voters, human rights groups, and the international community. Under President Obasanjo, a hero of the 1967–1970 Civil War, the party resolved this dilemma by adopting a dual strategy, complementing the purges with a series of less-visible measures that reassured the exiting military that the PDP’s “umbrella” (its logo) would be big enough for them too.

The PDP’s Dual Policy: Impunity, Promotions, and Pathways to the Private Sector

The PDP took four steps to reduce the military’s anxieties, which demonstrate how it adapted and implemented the transition’s pact to a post-military regime. First, it established a truth commission that enabled victims of the nation’s dictatorships to vent grievances, but this generated few confessions by perpetrators and no successful prosecutions. The terms of reference for the newly minted Human Rights Violations Investigations Commission charged Justice Chukwudifu Oputa with investing human rights abuses dating back to the coup that ended the Second Republic on New Year’s Eve of 1983. President Obasanjo further tasked the Commission to identify individual or organizational perpetrators, ascertain state culpability, and make recommendations for redress (Constitutional Rights Project 2002). Despite hopeful comparisons of Oputa to Desmond Tutu in South Africa, the government never released the “Oputa Panel’s” findings nor successfully prosecuted the major culprits of abuses under Abacha (1993–1998), Babangida (1985–1993), or Buhari (1984–1985). The newly appointed Chief of Army Staff Malu appeared on television before the Panel to insist Diya actually had been plotting a coup. Malu also repeatedly proclaimed his own loyalty to Abacha: “I feel proud wearing the badge of Abacha. I will wear it again, if I am given any,” exclaimed Malu (Agekameh Reference Agekameh2001, 31). The following year Obasanjo fired him, but he also received numerous commendations; he later told a group of northern elites that he regretted not staging a coup against Obasanjo (Mamah and Ajayi Reference Mamah and Ajayi2006).

Civil society’s miscalculations, or shifting organizational self-interests, may have midwifed this miscarriage of justice with Oputa. Immediately after the transition, frontline human rights groups such as the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO) announced that it had to change apace with the times. It participated in activities such as election monitoring but “it failed to act against the executive lawlessness of the state actors” (Mohammed Reference Mohammed, Ibrahim and Ya’u2010, 133). “We thought that the major problem would be driving the military out. We found that we should have organized much, much better after the handover from the military” recall activists involved with the Transition Monitoring Group. “Because we did not organize, civil society became broken into parts” (Ndigwe Reference Ndigwe2017). Donors compounded these problems of fragmentation amidst shifting priorities at this critical moment during the transition. Competition over new grants and contracts undermined efforts to agree on shared reform agenda groups. It also created incentives for groups to reorganize more hierarchically so that leadership could cultivate relationships with big funders; this naturally weakened ties to their respective grassroots bases (Kew Reference Kew2016, 333). In the end, Nigerians obtained neither truth nor accountability.

A second source of reassurance for exiting military officers was that they had ample opportunities for new careers. Many joined the ranks of the PDP. For example, four senior retired military officers embraced their civilian status and won seats in the new National Assembly: Major-General Nwachukwu, Brigadier Jonathan Tunde Ogbeha, Brigadier David Mark (who went on to become Senate President), and Nuhu Aliyu. According to one study, retired generals such as Major-General Ali Mohammed Gusau and Lieutenant-General Danjuma constituted the backbone of the PDP’s fundraising apparatus. During previous, failed transitions, military involvement was seen as an “aberration.” But, by 1998, officers were more comfortable with politics, and many had resigned themselves to the role of “big money” in politics. Most importantly, Adekanye documents the expansive involvement of the military in the economy over the previous two decades; this in effect gave many officers a more concrete stake in stability and the external legitimacy (i.e., for attracting foreign investment) that a civilian government would offer (Adekanye Reference Adekanye1999, 184). “Since 1999, the retired generals have dominated political activities,” writes Braji in a similar study. “The ruling PDP has become subservient to the dictates of the retired generals” who have successfully reduced the influence of the original G34 leaders who formed the party (Braji Reference Braji2014, 179).

Many former military officers moved into the private sector, typically building on contacts and investments they had already established during active duty under the military regimes. For example, those who went into agriculture, including President Obasanjo himself, had already acquired land during their previous forays into politics during military rule. Abubakar transformed his small family farm into a massive operation, with over 300 laborers during harvests. The ex-military also had more access to capital due to policy changes engrained within the transition. Just days before the handover to civilians, Abubakar issued a decree outlining the procedures and policies for privatization, thus saving the incoming civilian regime from getting stuck with a contentious issue – and generating new opportunities for newly unemployed generals. “President Obasanjo’s policy on the recapitalization of banking and insurance sectors gave the retired military officers the opportunity to appropriate weak private and state-owned financial institutions” (Braji Reference Braji2014, 161). In the transportation sector, Abacha-era power brokers such as Brigadier General Yakubu Muazu moved into the airline business (thriving because the roads are so bad and the oil boom expanded the middle class) immediately after Obasanjo retired him. Ibrahim Babangida, the former dictator, purchased Nation House Press and several other media outlets. A long list of former generals, including T.Y. Danjuma, went into manufacturing or the oil sectors, while others capitalized on the construction boom with engineering ventures. Importantly though, the ex-generals in each of these sectors cultivated close ties to politics, since they needed access to government spending for capital and government power to avoid regulatory roadblocks (Braji Reference Braji2014). Obasanjo’s revocation, early in his term, of oil block rights held by many military officers underscored the importance of maintaining ties to politics. After the transition, senior civilian bureaucrats moved into directorship positions within multinational subsidiaries, though few had capital on the scale of Ahmed Joda, a former Federal Permanent Secretary.

Third, President Obasanjo and the PDP reassured soldiers who opted to stay in the military by increasing the military’s resources and benefits. In a comparative study of civilian control over militaries, Powell (Reference Powell2012) characterizes such decisions to “spoil” the military as “coup-proofing.” While public estimates are probably understated, available data show that Nigeria’s military budget increased from US$793 million in 1998 as the transition began, to over US$2.2 billion (in constant 2015 US dollars) by 2002 (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute 2016). These trends are illustrated in Figure 2.1. This was a substantial sum of money for a military that had shrunk after the 1999 transition and that faced no serious external or internal threats.

Figure 2.1 Military spending, 1998–2015 (in constant USD).

The ranks slowly grew to about 100,000 in 2010 after various peacekeeping deployments. There was some resentment within the military for these deployments. But they facilitated what Huntington identifies as a critical step for depoliticizing militaries by keeping them focused on military missions rather than developmental or domestic policing operations. Similarly, he suggests moving the troops away from the capital to “relatively distant unpopulated places.” Finally, Huntington advises spending on militaries as insurance against a praetorian uprising. “Your military officers think that they are badly paid, badly housed, and badly provided for – and they are probably right” (Huntington Reference Huntington1991, 252). Civil society observers and the National Assembly alike acknowledged such frustrations in the military after the 1999 handover (Fayemi Reference Fayemi2002). An American contractor reported that 75 percent of the army’s equipment was damaged or unusable, fewer than ten of the navy’s fifty-two vessels were seaworthy, and only a handful of helicopters and planes in the air force were combat-ready (Africa Research Bulletin 2000). The spending also gave Nigerian military hardware a needed boost.

Fourth, the PDP government approved a massive wave of 879 military promotionsFootnote 8 a mere two weeks before Obasanjo was sworn in for his second term in 2003. These promotions by rank, illustrated in Figure 2.2, have received far less attention than the dismissals and forced retirements discussed earlier. They provide further evidence of the PDP’s dual policy toward the military, pointing to “coup-proofing” strategies in order to avoid the sort of military frustrations that Huntington warns about.

Figure 2.2 Military promotions announced in May 2003.

Note: Figures include at least twenty-five executive commissions converted to promotions.

In sum, the PDP’s founders agreed upon an understanding that their presidential candidate needed to be Yoruba in order to bury the lingering resentment over the annulled 1993 election once and for all. The party also borrowed from ideas of power rotation discussed during the failed 1995 constitutional convention and consistent with the federal government’s policy of federal character, in place since the postwar years. “Power shift” would alternate power between north and south, while “zoning” would rotate offices across six geographical areas at the national level, across three senatorial districts within each state, and typically across different neighborhoods within each of the 774 local governments. In settling on Obasanjo and marginalizing Ekueme in its primaries, though, the PDP established lingering resentments among eastern Igbos – a hazardous legacy I return to in Chapter 6.

Most importantly, the PDP squarely confronted the dilemma of civilian control of the military through its dual policy. President Obasanjo purged the ranks of officers who had played a role in politics, linking such efforts to a broader policy of professionalization that colored the dismissals as reform rather than retribution. This reflects the advice of one study at the time: “civilian control should not be seen as a set of technical and administrative arrangements that automatically flow from every post-military transition, but, rather, as part of overall national re-structuring” (Fayemi Reference Fayemi2002, 119). The PDP also reduced military anxiety by increasing military spending, limiting the Oputa Panel’s terms of reference and depriving it of prosecutorial powers, and promoting nearly 900 officers in the final days of Obasanjo’s first term. Finally, the party generated career opportunities for retired military officers. A new post-transition generation of retired officers rose within the PDP after 2003, including ex-military elites who had not previously been involved in forming the PDP or forcibly retired as part of the transition. Their absorption into the PDP means that the party had institutionalized the military’s influence, and that the transition’s pact with the military had survived those initial years of transition. “This attests to the political ingenuity of the military retirees who are able to conspire and take control of such an influential party” (Braji Reference Braji2014, 180).

Eroding the Transition’s Pact and Defeating the PDP

The vast research on pacting and democratization discussed in the literature review has little to say about why pacts collapse. In their massive volume, O’Donnell and Schmitter only briefly list factors such as secularization, social mobility, and market vulnerability, which make it difficult for elites to control their followers – the pact beneficiaries. Voters eventually become more “free floating in their preferences,” and parties without a history within the pact may form. In much the same vein, associations may demand more autonomy from partisan or other controls on behavior. “Under these circumstances, it will become increasingly difficult to hold the elite cartel together” (O’Donnell and Schmitter Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter, O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986c, 42). They also note that cartels easily rot from within over time. Guaranteeing elites a seat for political participation, a share of the economic spoils, and protection from outside competition makes them lazy, undermines their accountability to voters, and eventually leads to corruption.

This section explores how such factors undermined the transition’s pact. Elected politicians who looked less and less like the youthful population, ambitions frustrated by zoning and power shift, and an expanding middle class (described in the next chapter) with “free-floating” preferences all contributed to the PDP’s electoral defeat. “The incumbent PDP president did not understand the danger signs,” explains one PDP governor. By 2015, “the binding factors that held the PDP [together] began to fall apart, and the people started moving across lines without his noticing it” (Ikpeazu Reference Ikpeazu2017).

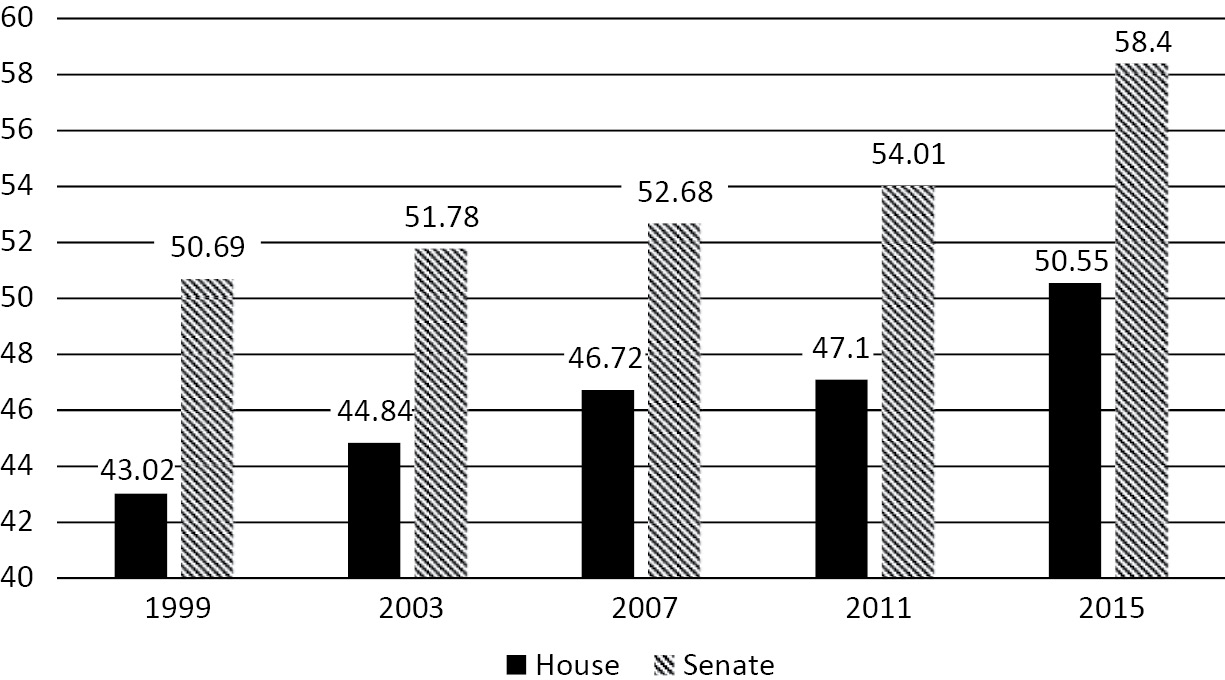

One source of change in the PDP concerned subtle shifts in its composition. By 2011, the party had more candidates and officers coming from non-military backgrounds. For a party rooted in the transition’s pact with the military, these social and demographic trends impacted the coherence of its founding principles. As the years went by, there were simply fewer and fewer who had lived through or fought for the transition. Heading into the 2015 elections, PDP elites faced a striking demographic dissonance. On the one hand, the country’s mean age declined with rapid population growth. With an overall population growth rate of between 2.5 and 2.6, Nigeria is one of the fastest-growing populations in the world. According to the World Bank’s estimates, in 2013 about 44.1 percent of the population was under the age of fifteen, a figure that had steadily increased since 2000. On the other hand, the average age of politicians elected to the House and Senate increased over the same period. The 1999 transition elections produced nine senators under the age of forty; the 2011 elections yielded none. The House had 132 members under forty in 1999, and only 34 members in 2011. As the country was getting younger, PDP politicians were getting older (LeVan Reference LeVan2015b). Figure 2.3 illustrates this latter trend.

A second, larger problem in the PDP concerned the party’s internal rules to rotate power and limit eligibility for positions based on one’s ethnographic background. The PDP had implemented “zoning” of political offices at national, state, and local political levels. As the transition progressed, the informality of rotational principles left the nation unprepared for unexpected contingencies. The resulting deviations gradually undermined the pact’s relevance.

An example of the confusion generated by the informality of zoning arose when Obasanjo ran for his second term in 2003. Igbos, led by Governor Orji Uzor Kalu of Abia State, pushed back, insisted that the presidency had been zoned to the southeast for 2003–2007. Naturally, Obasanjo used the PDP machinery to punish Kalu later by removing his party allies in the state (Obianyo Reference Obianyo, Ayoade and Akinsanya2013). This reflected a minority interpretation of power shift, but it also would have been consistent with its guiding assumptions, since the presidency would remain in the south (the east being a part of the south in Nigerian geography) for the period of two presidential terms. It would also mean that the PDP would have opted to not run a relatively successful incumbent. The collective interests of the party prevailed, in part because few party leaders seemed to share Kalu’s understanding of how power shift relates to internal party zoning; he was apparently still interpreting power shift through the eyes of the 1995 constitutional convention (which envisioned a single term).

The informality of power shift presented an even more explicit challenge to the PDP’s hegemony when it contradicted the constitutional provisions for presidential succession, further eroding the pact under Obasanjo’s successor. In November 2009, President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua fell ill and disappeared from public view for over five months. His inner circle of advisers, his wife, and his security detail refused access to various emissaries, including members of his cabinet who had constitutional authority to determine his competence to govern. With Yar’Adua in office barely two-and-a-half years before falling ill, northerners were concerned that formally handing over power to Vice President Goodluck Jonathan would abbreviate the north’s “turn” to rule. A bizarre court decision in January 2010, celebrated by Yar’Adua’s allies, complicated constitutional matters by declaring that the vice president was already carrying out such duties, thus obviating the need for an explicit transfer of power. Members of the House and Senate took to the floor to call for a transfer of power to the vice president. Obasanjo, who had handpicked Yar’Adua as his successor, told a meeting of the PDP’s Board of Trustees that the court’s judgment was plainly inconsistent with the Constitution. More urgently, he said “there is no commander in chief and the vice president has no power. Some people cannot see the danger, so let me make it very clear by asking: what if there is a military coup?” (Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2011, 204). For the final three months before Yar’Adua’s death, Jonathan served as acting president, authorized by the National Assembly on February 9, 2010 under the controversial “Doctrine of Necessity” (Campbell Reference Campbell2013c). The Senate President, David Mark, said the situation had not been contemplated by the Constitution (Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2011). Obasanjo’s coup fears seemed entirely real when Yar’Adua finally did return from treatment in Saudi Arabia and a large military detail met his plane in the dark of the night without informing the top defense officials (LeVan Reference LeVan2015a).Footnote 9

The nation survived the constitutional crisis but then the party faced a new dilemma with the 2011 Presidential Election around the corner: should Jonathan run with all the advantages of incumbency, or should the PDP honor power shift? The PDP sent mixed messages, sometimes suggesting that Jonathan would run and other times implying he would step down, thus giving northerners hope that the party would uphold (Kendhammer Reference Kendhammer and Obadare2014). When the PDP’s Board of Trustees met after Yar’Adua’s death on May 5, 2010, northerners, led by Governor Babangida Aliyu of Niger State, argued that the party should respect rotation or renegotiate it. Some northerners seemed to belittle Obasanjo’s 1999 candidacy, saying they he became the candidate “to put June 12 behind us,” referring to the Yoruba frustration with the annulled 1993 election (cited in Ayoade Reference Ayoade, Ayoade and Akinsanya2013, 36). Others, under the banner of the Northern Political Leaders Forum (NPLF) took a harder line, declaring, “Northerners have all it takes to win free and fair elections without special arrangements” (ibid). These elites argued that Jonathan violated power shift, and if he wanted to run in 2011, he would have to leave the party. Former Vice President Atiku Ababakar of Adamawa State emerged from a NPLF pool of northern contenders that included former dictator Ibrahim Babangida, Jonathan’s National Security Adviser Aliyu Gusau, and Kwara State Governor Bukola Saraki. In the end, “incumbency was a critical factor in favour of Dr. Jonathan,” argues a study of PDP’s internal dynamics at the time, though fear of a rise in Niger Delta violence also played a role should the first president from the region be denied the chance to run (Ayoade Reference Ayoade, Ayoade and Akinsanya2013, 38).

With rotation of power no longer a sacrosanct principle, politicians further chipped away at it inside the National Assembly. In 2011, the PDP had zoned the position of Speaker of the House to a member from the southwest and the Deputy speaker to the northeast. But then Emeke Ihedioha, a powerful Igbo politician from the southeast, built a large enough voting bloc to support his election to the Deputy Speakership in return for supporting Aminu Waziri Tambuwal, a politician from the northeast, for Speaker. Both positions thus violated the party’s internal rules of power shift, with predictable consequences; when Ihedioha vied for the Imo State governship in 2015, party leaders said he “should not be given ticket to return or go for higher position” of governorship (Afolabi Reference Afolabi2014). Tambuwal, seeing his ambition similarly blocked by the rules of power shift, eventually left the PDP and went on to win the governorship of Sokoto State under APC’s banner. As the PDP repeatedly turned to traditional mechanisms of party discipline by suspending members, it frustrated the ambition or more and more politicians.