That’s love

Let’s forgive one another

Let’s talk together

Love these days makes it difficult for me to marry

It was a hot, quiet Sunday afternoon, and we sat together lazily in the lelwapa. Kelebogile, Oratile, and Tshepo were braiding Lorato’s hair. I sat with Mmapula and her granddaughter Boipelo on a blanket spread out in the shade of the stoep. Boipelo was nursing her infant child; the other children lay on the blanket with us, and then clambered over us, and then chased each other around the yard, their irrepressible energy in stark contrast to our lethargy. Kagiso tinkered with a car nearby; Dipuo sat mending a chair and half-heartedly waving off chickens.

We were joking about the possibility of Boipelo’s and Lorato’s marriages. Both girls were in their mid-twenties and were in relationships we all knew about but avoided discussing. Boipelo had a child. They were prime candidates. Tshepo, Boipelo’s younger sister, had asked in passing how much her grandmother Mmapula would expect for bogadi. ‘These days, I would insist on at least ten cows,’ Mmapula asserted. Her daughters and granddaughters all set up an instant clamouring disagreement. ‘Heela!’ exclaimed Kelebogile. ‘What man can offer that many cows?’ ‘No family can agree to that!’ added Oratile. The younger girls laughed and made noises of incredulity and dismay.

‘Listen, let me tell you,’ Mmapula rejoined sternly. She numbered the cattle off on her fingers: one for Mmapula’s younger brother, who was malome to the girls’ mothers; another for Dipuo’s older brother; two for the girls’ own mothers’ brothers (for Lorato, Modiri; for Boipelo, Kagiso); two for Dipuo himself; two for other relatives I couldn’t place; and two for the feast. The genealogies left us all baffled. But their bafflement didn’t stop the younger women from taking issue with these distributions, arguing all at once that nothing was owed to the old man’s brother, that one cow should be enough for their own bomalome – Kagiso protested half-heartedly from under the car bonnet – and that the cattle for the feast should properly come from the herd at home.

‘Now you see why none of us is married from this yard,’ Lorato observed archly, bracing herself as her hair was pulled and twisted. Tshepo, 17 years old and precocious, took a different tack. ‘Aaa-ee! Nna I am taking bogadi for myself!’ she insisted with comic vehemence, to general laughter. ‘How am I supposed to start my family if my husband has given away all his cattle? How will I look after my children?’ It was a position I had heard her rehearse almost word for word in past conversations; it was both satirical and serious, deliberately provocative.

‘You can’t take bogadi for yourself!’ her grandmother challenged, while her mother’s younger sisters laughed.

‘At least my mother should get it so she can build, then,’ Tshepo said. ‘But not my father! What has he done to raise me?’ Tshepo’s father had lived with Tshepo and her siblings their whole lives but had never taken any formal steps towards marrying their mother. He had had only intermittent work, squandered money on drink, and was generally considered a deadbeat, not least by Tshepo herself.

‘Heela,’ her grandfather intervened, quietly but sternly. ‘Your bogadi will come to me, both of you. Your fathers never paid bogadi for your mothers. You are my children.’

‘And I’m saying, ten cows,’ Mmapula added.

‘Ijo! Nna I’m not getting married then,’ exclaimed Tshepo. ‘Or I’ll tell my man to keep his cattle so we build a house,’ she mused, deftly exploiting the congruence of terms for ‘my man’ and ‘my husband’ (both are monna wa me).

‘O tla ipona!!’ rejoined her grandmother – you’ll see (lit. you’ll see yourself). ‘What happens when he leaves you like that with your children? As for us, we won’t know anything about it.’

‘These days women can even pay for their own bogadi,’ observed Lorato, generating another reproachful and incredulous clamour from the women. ‘I can’t,’ she clarified. ‘How can you marry yourself? And if the man can’t even pay bogadi then how do you know he will look after you? He can even leave. But some women who have money and their men don’t, it happens.’

‘Hei, even NGOs marry people these days!’ added Boipelo, to even greater collective surprise. ‘Didn’t you hear about that NGO in Mochudi? They take unmarried couples who have long been living together and already have children, and marry them! The NGO even finds the cattle for bogadi, and rings; they have the whole ceremony!’

‘Ee, when people like this old woman expect ten cows what else can we do?’ observed Oratile.

‘Ija! Ke kgang,’ Mmapula exclaimed, derisively. ‘Then when there are problems, who resolves things? Do the woman’s bomalome negotiate with themselves? Does the NGO look after their children? Do these NGOs think people have no parents?’ Everyone laughed at the series of incongruous scenarios.

‘Mm-mm,’ Dipuo commented, shaking his head in dismay. ‘Re bona dilo.’ We are seeing things.

The topic of bogadi, or brideprice – often also called lobola, as elsewhere in Southern Africa – came up frequently among the Legaes. It often triggered a subtler array of questions and concerns around marriage, pregnancy, and children, and about intimate relationships more generally. At the time I lived with them in 2012, six of Mmapula’s eight children, and one of her grandchildren, had had children of their own; but by the time I was on fieldwork, none of them had yet married, much to Mmapula’s chagrin. The situation was not unusual. At the time, marriage rates in Botswana, and across Southern Africa, had been in sharp decline for years (Pauli and van Dijk Reference Pauli and Dawids2017). While Mmapula was keen to see her children married, she was also very concerned that those marriages should be concluded in a specific way. Her preoccupation with how things should be done drew together many of her abiding worries, and her children’s abiding uncertainties: the success of their self-making, the care of their children, and the solvency, well-being, and reproduction of the extended family. Mmapula was not alone in her anxieties: deep ambiguities in the reproduction of Tswana kinship have preoccupied Batswana and anthropologists of Botswana for at least a century (Comaroff Reference Comaroff1980; Reference Comaroff, Comaroff and Krige1981; Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Livingston Reference Livingston2003b; Lye and Murray Reference Lye and Murray1980; Schapera Reference Schapera1933; Reference Schapera1940; Solway Reference Solway1990; Reference Solway2017a; Upton Reference Upton2001; van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010; Reference van Dijk, de Brujin and van Dijk2012a; Reference van Dijk2017) – and they have taken on new urgency in the context of one of the world’s worst AIDS epidemics.

Taking cues from the scene above, this part engages the fraught ways in which Tswana kinship is extended and reproduced through intimate relationships, as well as the legacies of this fraughtness for self-making. The loaded tropes around seeing, saying, and knowing that peppered our conversation – and that emerge frequently in such conversations – indicate ways in which conjugal relationshipsFootnote 2 transform and are transformed into kin relationships during pregnancy and marriage negotiations: in a gradual, carefully managed process of recognition. Both the tone of contestation in the family’s discussion and the wide range of problems and disagreements it anticipated also suggest that recognition is a fertile source of dikgang: ‘issues’, problems, conflict, or crisis. I show how it is in the acquisition of these dikgang, and the collective process of reflection and interpretation through which they are negotiated, that new kin relations are constituted, and self-making pursued. Finally, I extend these possibilities to conjugal relationships in a time of AIDS, and suggest that the risk of contracting the disease is of the same order as the risks of dikgang that Batswana routinely face in managing such relationships. I contend that it is the management of recognition as much as – or more than – the risk of illness and death that raises the stakes of HIV infection, while offering families a key means of addressing the crisis AIDS represents, and of living with the epidemic.

Recognition

‘Recognition’ is a concept elaborated by social scientists, but I use it to condense a range of emic terms and ideas: specifically, go bona (to see), go bua (to speak), go utlwa (to hear/feel), and go itse (to know). These terms appear regularly – often interchangeably – in Setswana conversation, as exclamations and challenges. O a bona (you see) is frequently appended to the end of sentences, as is o a itse (you know). O a utlwa (you hear) is affixed to instructions or requests. Such injunctions may indicate the clarification of ambiguity, an invitation to agree, an attempt to convince, or an implicit insistence on being heeded; responses cast in the same terms may mark either willingness or refusal. Recognition, in this sense, is perpetually sought but frequently evaded and contested. And it takes on special relevance in the context of both relationships and self-making. Among the Tswana, love, care, understanding, and so on involve not simply sentiment but action, demonstration, and performance, so that they can be seen, heard, and felt (Alverson Reference Alverson1978: 138; Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 6). In being seen, heard, and felt – in other words, recognised – these enacted sentiments create intersubjective effects: health, strengthened relationships, prosperity, and the capacity to give and evoke love and care. At the same time, refusals or misinterpretations of such demonstrations can produce jealousy and scorn, which also generate sentimental action, with potentially deleterious repercussions for the well-being of others – including illness and the threat of witchcraft (Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 4–5). In this sense, recognition is both a key dimension of sociality and a key source of social risk (Durham Reference Durham and Klaits2002a; Durham and Klaits Reference Durham and Klaits2002).

This tension between the risks and possibilities of intersubjectivity underpins the Setswana understanding of personhood and self-making as well. On the one hand, the risks of recognition ground an imperative to keep the self fragmented and concealed – never fully seen, known, or grasped – in order to protect it from danger, and especially from witchcraft (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001). On the other hand, recognition is a singular source of self-knowledge and moral personhood; as Richard Werbner notes from his work among Tswapong wisdom diviners in Botswana’s north-east, ‘[u]pon recognition by others depends the very dignity of the self’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2015: 2). It is only possible to know an intersubjective self ‘mirrored in the gaze of others’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2016: 83, echoing Laidlaw Reference Laidlaw2014: 502); making oneself involves inviting the ethical reflection of others on oneself. And doing so successfully – in ways that contain the risks of recognition already noted – requires the careful management of what others see, hear, and know. Not only does recognition therefore inevitably involve ‘ambivalence, conflict and contradiction’ (Werbner Reference Werbner2016: 82), it is sought, achieved, and ascribed through them – in other words, through dikgang.

The management of recognition, then, involves the management of selves and relationships; as such, it also structures power, hierarchy, and specifically gender. The licence to hear, know, and speak in the resolution of disputes, for example – whether at home or in the kgotla – is held customarily by older men and is instrumental in conveying their authority (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010: 290). In Werbner’s terms, it exposes them to reflection on the part of a wide range of others, and therefore to greater risk, but also to more far-reaching recognition and potentially greater dignity and political power. Women, too, hear, know, and speak in the management of dikgang and thereby gain recognition; but, as we have seen already and will see in the chapters of Part III, their repertoires are comparatively constrained, centred largely on the household and its relations. The reflection of others on women’s behaviour is tied to the appropriate observance of these constraints – which is one reason silence figures so strongly in women’s management of dikgang, and particularly dikgang involving men. As well as different repertoires of hearing, knowing, and speaking, different sources of dikgang are key to the recognition of men and women: pregnancy and its attendant crises prove most formative for women, and marriage and its attendant crises for men.

Framing conjugal relationships in terms of recognition, I suggest, avoids the limitations of considering them in terms of either exchange or love, as either collective processes of social reproduction or strictly personal projects – framings that have predominated in the anthropology of marriage and intimacy, especially in Africa (Smith Reference Smith, Cole and Thomas2009: 159). Recognition makes room for both affect and economy, mutuality and contract (Gudeman Reference Gudeman, Hart and Hann2009), sociality and self-making, capturing their mutual entanglements and the tensions between them while underscoring the social creativity of the conflicts that inevitably emerge. It creates space to draw filial and affinal relationships into the same analytical frame, marking a key point of articulation between the two. It draws together both the social processes and the events that mark contemporary Setswana marriage and pregnancyFootnote 3 and their shifting temporalities, their quickenings, foreshortenings, and inversions (Livingston Reference Livingston2003b; Solway Reference Solway2017a; Upton Reference Upton2001). And it makes room for ambiguity, partiality, and reversibility, incorporating – for example – practices of secrecy and concealment, where relationships may be known but not spoken (Hirsch et al. Reference Comaroff and Roberts2009). It accommodates the jural, processual, and ritual dimensions of conjugality; and it accommodates the equally crucial ethical practice of inviting and undertaking reflection on the self. In this sense, recognition captures both the historical sensibilities that inform Setswana conjugality and emergent practices that may be changing it (Comaroff Reference Comaroff1980; Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977; Solway Reference Solway2017a; van Dijk Reference Pauli and van Dijk2017).

These dynamics of recognition, of course, take on a new significance in a time of AIDS. The recognition of those living with HIV has alternately mediated or foreclosed access to treatment, precipitated alienation from community and kin, or granted ‘therapeutic citizenship’ (Henderson Reference Henderson2011: 24; LeMarcis Reference LeMarcis2012; Nguyen Reference Nguyen2010: 89–110). In Botswana, governmental and non-governmental responses to the epidemic have produced new, formalised modes of recognition, emphasising the need to know one’s status and speak about it with sexual partners, while promulgating ‘confessional technologies’ and ‘a market for testimonials’ seen elsewhere in the management of HIV and AIDS (Nguyen Reference Nguyen2010: 21, 35–60). Botswana’s nationwide voluntary HIV testing programme is even called Tebelopele, or ‘vision’. Secrecy, concealment, and silence, on the other hand, are linked to the spread of the virus – originally cast in Botswana, as elsewhere, as a dangerously ‘silent’ or ‘invisible’ epidemic (ibid.: 2) – and thereby pathologised. These shifting, heightened stakes around recognition suggest one possible link between the parallel ‘crises’ of AIDS and marriage, while the work that marriage does in the management of recognition suggests one reason why churches and other intervening agencies might present it as a panacea to the epidemic (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010: 287).

In the stories that follow, I describe courtship, pregnancy, and marriage – in that order, as they are most frequently experienced in the Tswana life course – as marking a continuum of recognition, negotiation, and risk. I explore the ways in which women and their relationships are made recognisable, largely through their bodies, in pregnancy, and the ways in which men and their relationships are made recognisable, largely through the marriage negotiations they undertake. I consider the concealments both allow and the dikgang both produce – including dikgang across generations, among siblings, between the conjugal partners themselves, and between their respective extended kin, as well as the unresolved dikgang of past pregnancies and marriage negotiations, which are brought into intergenerational recognition in turn. More than just a question of managing new economic constraints or producing new class distinctions (e.g. James Reference James2017; van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010; Reference Pauli and van Dijk2017), I suggest that pregnancy and marriage require engagement with fraught family relationships and histories, in anticipation of fraught futures. I further suggest that acquiring and successfully navigating these dikgang – which include the full range of dikgang that characterise kin relations – are crucial, gendered dimensions of self-making and underpin the potency of both pregnancy and marriage in reproducing and reorganising relationships among kin. These processes may reorient relationships between households, but they are also strikingly preoccupied with realigning relationships among existing kin – a long-standing orientation that indicates the persistence of ambiguity, even in times when certainty is sought (cf. van Dijk Reference van Dijk, de Brujin and van Dijk2010; Reference Pauli and van Dijk2017). And in these practices, unexpected means of absorbing and addressing the risks presented by HIV and AIDS emerge.

The dogs chase the last jackal.

When Boipelo’s pregnancy began showing, at about four months, her mother Khumo hastened halfway across the village to her own mother’s – Mmapula’s – home. Boipelo, not yet 20, was the eldest of Khumo’s six children. Khumo was a calm and pragmatic woman, extremely hard-working, independent, and reserved, sometimes recalcitrant. But on that day, her report to her mother was frustrated and despairing: ‘Who could the boy be, in this village? They’re useless! Unemployed, no money. How will we look after a baby?’ Khumo and her children lived in a cramped, two-room lean-to, and they struggled to make ends meet. Boipelo had just finished school, and her mother had hoped she would find work and help build a house. Instead, there was a baby on the way.

Lorato, Boipelo’s older cousin, fell pregnant at roughly the same time. Lorato knew about Boipelo’s pregnancy from the beginning, but she told no one at home about her own. Knowing that it would put enormous pressure on the family to have two babies at once, Lorato and her boyfriend considered crossing the border for an abortion in South Africa. But he had a good job and was building a house in the city – perhaps, she thought, they could manage to raise a baby on their own. They decided to keep the child.

Lorato’s pregnancy started showing shortly after Boipelo’s. When Mmapula noticed, she sent two of her daughters to call Lorato and confront her. Having had her suspicions confirmed, the old woman hastened down the street to confer with trusted neighbours (who were also relations). She was as frustrated and despairing as Khumo had been a few short weeks before.

The double pregnancy happened before I returned to Botswana for fieldwork, but I received a formal and somewhat disconsolate email from Kelebogile informing me of the situation – a rare occurrence in its own right. Lorato had recounted the events to me within days of my arriving back, and, over time, Oratile and Kelebogile filled in bits and pieces as well. For many of my friends in Botswana, as well as for Boipelo and Lorato, pregnancy marked a major watershed in relationships with lovers, in family relationships, and in life trajectories. In most cases, it preceded – but seldom precipitated – marriage (a long-standing trend; see Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977: 99; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Lye and Murray Reference Lye and Murray1980; Schapera Reference Schapera1933; Townsend Reference Townsend1997). Pregnancy was often, though not always, the point at which a courtship became unavoidably apparent. It brought sexual relationships, otherwise carefully kept secret, into the sphere of the seen and the spoken, the known and the negotiable. It subjected them to reflection, assessment, and interpretation; it made them recognisable. And this shift was part of what gave pregnancy an aspect of crisis, both for the soon-to-be parents and for their families. It was a risky shift: pregnancy rendered the existence of an intimate relationship recognisable, but not its critical details. There was no incontrovertible means of identifying the father, and no certainty that his partner would name him. He or his family might dispute or deny the claim, refusing to be recognised. If the father admitted paternity, but he and his family had few resources, the mother’s family had little hope of laying charges or claiming financial support for the coming child and might wish that he had remained hidden. On the other hand, if he was well off, charges might be laid (a colonial-era invention; see Schapera Reference Schapera1933: 84) but might not be honoured, which might undermine the relationship itself. The recognition of pregnancy was, in other words, a source of numerous potential dikgang, which required careful negotiation between couples and within and between their families. The success or failure of reproducing family lay in the success or failure of these negotiations as much or more than in the pregnancy itself. Success, in this context, meant leaving these dikgang at least partially unresolved. Such a suspension did not necessarily stabilise the relationship, but it left open the eventual possibility of marriage.

After her distraught visit to the neighbours, Mmapula gathered her resolve and set the mechanisms of pregnancy negotiation in motion on two fronts. She asked two of her sons – Moagi and Kagiso – to talk to the girls individually and to find out who the fathers of the children were. They learned that Lorato’s boyfriend was older, and employed, although he was from far away. This information gave Mmapula hope: if the negotiations were handled properly, he would be in a good position to support the child and might ultimately prove to be suitable marriage material. In the meantime, she could assert a claim for compensation. She dispatched her sons to summon him to the yard. Boipelo’s boyfriend, by contrast, was a former neighbour, young and sporadically employed, and his family was not well off. His family’s proximity meant that they could easily have been called or visited, but the matter was not pursued. In fact, the boy’s family was not officially notified about the pregnancy until after the child had been born, although he and Boipelo continued their relationship.

Moagi and Kagiso sought out Lorato’s boyfriend, but he evaded his summons. On a couple of occasions Lorato was visiting him when one of her uncles tried to call him, and she identified the callers. When he still refused to answer, she began to doubt his willingness to take responsibility for the child he had fathered. ‘He said, “I haven’t done anything wrong, why should I be called?”’ she explained, still hurt by the refusal. ‘I told him he couldn’t refuse to speak to my uncles. I asked him if he was refusing the child. He didn’t say anything.’ To her mind, his rejection of the summons suggested a rejection of the potential for kinship that her pregnancy had initiated.

Eventually, Mmapula herself acquired the telephone number of the man’s mother from Lorato and phoned her to report the pregnancy and assert a charge of P5,000 (roughly £425, enough for a couple of cows or a good bull) for ‘making our daughter’s breasts fall’ (for a description of the ‘fence-jumping’ fine, tlaga legora, see van Dijk Reference van Dijk2017: 32). She would have preferred to call the man’s family to her yard, but, given the distances involved and the apparent hesitance of the man to acknowledge the summons, she decided to hedge her bets. The man’s mother agreed to report the charge to her son, but promised little more. The matter was left there.

After that point, the man was sufficiently ‘known’ to Lorato’s family that they would ask after him, talk or joke about him as a potential husband, and allow Lorato to visit him for a few days at a time. Lorato’s mother’s brothers scolded her for laziness with the warning that, once she was married, they would not take her back, insisting that she should develop appropriate work habits now that she ‘had a man’. As the pregnancy progressed, the boyfriend supplied Lorato with ample food, clothes, lotions, magazines, and supplies for the child, reassuring her that he recognised the child as his own. But this mutual recognition remained tentative and tenuous; the man had refused his summons, had never officially visited the yard, and had yet to pay the fine levied on him. If he came to visit Lorato, he generally stayed in his car down the lane and avoided entering the lelwapa. When Lorato went off to see him, Mmapula occasionally asked, ‘And when is he coming to greet us? Tell him we are still waiting to see him. One of these days if something happens to you, we won’t even know where to look for you.’ Boipelo’s boyfriend was similarly circumspect, although he had been a frequent visitor to the yard before her pregnancy. He, too, was tentatively recognised as the father of Boipelo’s child, and Mmapula occasionally asked after him in private; but he was unable to cater to Boipelo’s needs as well as Lorato’s boyfriend, and there were few jokes about Boipelo marrying him.

While pregnancies signify the existence of serious relationships and make them formally known to the families of both partners, they don’t necessarily stabilise the relationship itself. A friend demonstrated this persistent uncertainty to me on the bus home one day. She had been fielding amorous text messages from an older man in the village. ‘Hei! The way this one was after me when I was pregnant!’ she commented offhand, much to my astonishment. She saw my shock and laughed. ‘You don’t know these men. They propose to us when we’re pregnant because they know they don’t have to worry about impregnating us! No chance to get caught!’ I asked what her boyfriend thought about it. ‘O! Why should I tell him? He was too worried to touch me the whole time I was pregnant. What should I do? And anyway he probably has his girls,’ she added with a note of bitterness, thumbing out a reply on her phone. While pregnancy and the fines and negotiations attendant upon it rendered some relationships recognisable, my friend seemed to indicate that it safely concealed others (compare Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001: 275).

The sorts of recognition conveyed by pregnancy, then, produce multiple dikgang, all of which are addressed in ways that perpetuate ambiguity rather than eliminating it. This ambiguity produces further dikgang in turn – but also leaves open the possibility of kin-making. Among the neighbouring Bangwaketse, Ørnulf Gulbrandsen (Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 22) noted a reluctance to take disputes around pregnancy fines to kgotla (customary court) for formal resolution, despite a tendency to favour the woman’s cause. He explains this paucity of prosecution in terms of guardians’ wariness about their daughters gaining reputations for being quick to sue (ibid.). However, something simpler may be at work: having failed to draw another family into mutual recognition, into the joint process of reflecting on the situation at hand and its implications for their relationships with each other that characterise the negotiation of dikgang, the would-be complainant’s family has already failed to make the would-be defendant’s family into kin. Drawing the family into formal negotiation at the kgotla may produce a final resolution – usually in the form of a payment awarded – but neither the formal process nor the final decision will produce a husband, nor the community of shared risk, ethical reflection and disposition, and continuous dikgang management that makes kin. Indeed, a formal, legal resolution ultimately forecloses those possibilities (a point we will return to in Chapter 12). Where fines and agreements are left ambiguous, processes of mutual reflection and recognition are suspended but can still be pursued – leaving the opportunity of kin acquisition as open as possible, on as many levels as possible, for as long as possible. This open-endedness creates a cycle of conflict and irresolution – potentially extending, as we will see, over the course of generations – and this cycle, I suggest, underpins the production and reproduction of Tswana kinship.Footnote 1

Afterbirth

Her grandmother and mother’s younger sister swaddled the baby boy and took him away before Lorato even knew of his death. At seven months, Lorato had gone into hospital, short of breath and with high blood pressure. The doctors performed an emergency caesarean, but the child’s lungs had begun to bleed, and by the time Lorato woke he was gone.

A small grave was dug adjacent to the room in which Mmapula and most of the children slept, virtually in the short pathway that led into the lelwapa past the outdoor kitchen. It was sealed with cement. It was some time after I had returned in 2011 that I was told where the grave lay, and I was surprised when I heard: it was a space where old plant pots and dirty buckets were left, where large cooking pots were tipped up to dry, and where the children played freely, often running over the top of it as they came charging around the edge of the house. But it needn’t have surprised me. Kelebogile’s first child, lost at roughly two years old, lay under the grandmother’s room next to it, buried there before the addition had been built. ‘That way she’s close to her mother in case she needs anything,’ Lorato said, explaining her own child’s burial by way of her mother’s sister’s lost girl.

Boipelo had been delivered of a baby girl shortly afterwards. Lorato and Boipelo were both taken to be motsetse – a term for new mothers in confinement – and both stayed with the baby in a room they shared in Mmapula’s yard. Neither of them was meant to move out of the house or yard for a month. Neither was permitted male guests, and neither could visit her boyfriend nor receive him at home. There were no special constraints on the girls’ movement outside the village, but while they were in the village they were prohibited from setting foot beyond the gate. Lorato was uncertain about the reasoning for this edict, but she connected it loosely to the prevention of drought and harm to cattle, and to the avoidance of risk to people who might cross her path – as well as avoiding risks to herself, Boipelo, and the child with whom they were confined. It was also intended to protect against witchcraft and illness, which were especially marked risks given the loss of Lorato’s baby (see Lambek and Solway Reference Lambek and Solway2001 on dikgaba, illnesses that afflict children and are linked to jealousy and witchcraft among relatives; see also Schapera Reference Schapera1940: 233–4; and, on ritual avoidance more broadly, Douglas Reference Douglas2002 [1966]; Turner Reference Turner2017 [1969]).

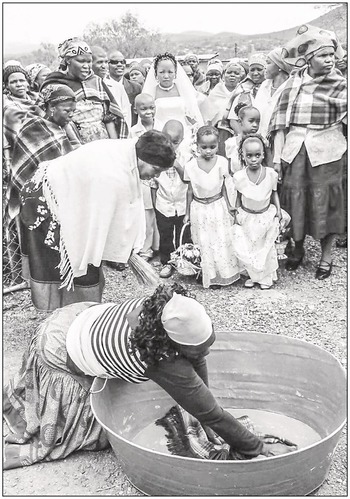

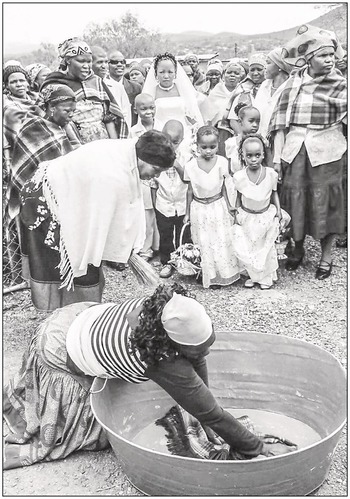

In this sense, a woman’s movement out of the yard and around the village after the birth – or loss – of a child presents a further and slightly different series of dangers, or dikgang, to be contained. And it is her natal family that has a special responsibility in containing them, especially where family-linked witchcraft is implicated. Confinement helps contain these risks in part by blocking and reversing the recognition that a woman’s pregnancy brings upon her and the relationship that produced it; it renders her and her child temporarily invisible, inaccessible, and their status unknown. Even old friends who had given birth while I was in the village suggested that I visit them at the clinic before they were sent home, ‘because you know how these elders are about witchcraft’.Footnote 2 The re-emergence of new mothers and babies into public spaces after their confinement is also a carefully managed, gradual process of controlling what can be seen, heard, spoken, or known, by whom and how. When Boipelo’s baby was first allowed out into the yard, her six-year-old brother Thabo remarked to the little girl, indulgently, ‘Ga re go itse, akere!’ – We don’t know you, do we? – as if to introduce himself, while distancing her from the risks that relational recognition might create. Parties are often held for children when they turn one year old, although only family and friends attend instead of the large public attendance expected at most other domestic celebrations. At the end of her confinement, Lorato’s maternal grandfather, Dipuo, instructed her to wash her feet, and then led her around the village silently, well before anyone was awake and might see them. He sprinkled her washing water before her, as if to contain the traces she might leave, enabling her emergence by concealing it. Containing recognition cannot eliminate dikgang, but it carefully circumscribes the relational sphere in which they may emerge.

Of course, the dikgang emerging from pregnancies are not confined to fraught dynamics of recognition around establishing paternity through fines or managing the dangers posed to and by postnatal women. They also emerge around the provision of care to the newborn child – specifically, the father’s recognition of responsibilities to contribute, and the recognition conveyed on him in turn. Lorato’s boyfriend had provided well for their baby’s needs and Lorato had a generous stockpile of clothes, nappies, toiletries, nutritional supplements, bathtubs, and other supplies stashed in her room before she lost the child. She spoke often and with deep fondness of the time she had visited her boyfriend and he had given her a sum of cash to buy whatever she needed for the baby from the shops. To hear Lorato tell it, pregnancy had been a time of plenty for her; she had had comparatively few responsibilities, had been accorded a degree of freedom to visit her boyfriend, and had been handsomely supplied with clothes, food, magazines, mobile phone units, and virtually anything else she desired – as well as everything that would be needed for the baby. She sometimes joked that it was the best job she had ever had – and, unlike other jobs, she hadn’t been expected to provide tokens of respect and support to her malome or grandmother, but could keep everything for herself.

While the gifts Lorato’s boyfriend had provided were not official gestures in the way that gifts presented in anticipation of marriage are (as we will see later), they did indicate a potential willingness and ability to provide for the care of Lorato and their child (compare Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 43) – a contribution to Lorato’s natal household that marked his acceptance of responsibility for her and a willingness to behave like kin, in keeping with his level of income. In many respects, the gifts were his one gesture towards recognisability; and they were a critical dimension in the family’s recognition of him, tentative as it was (compare similar allowances on the part of family in Schapera Reference Schapera1933: 80). At the same time, they did not stand in for a formal acknowledgement of the family’s claims on him, and – coming as they did through Lorato – they carefully evaded the sort of recognition those claims would establish over him and the ongoing cycle of negotiations they would precipitate. They were gifts given to Lorato, not debts paid or contributions made to her family; as such, they evaded dikgang. By comparison, Boipelo’s sporadically employed boyfriend had provided her with little or nothing prior to their child’s birth – which exacerbated his effacement at home.

‘Actually, that’s why I didn’t buy a stroller,’ Lorato added. I didn’t follow. She explained that her boyfriend had wanted them to buy a stroller – an expensive and uncommon item among families in the village. ‘He was insisting but I refused. How can I have a stroller, Boipelo having nothing?’ She explained that two of her mother’s younger sisters had faced a similar situation at the births of their own first children. ‘When Kelebogile was having her first child,’ she explained, ‘Oratile got pregnant about the same time. Kelebogile’s boyfriend was working and gave them everything. But Oratile was younger, the boyfriend was a bit useless, he wasn’t working or anything. So they were struggling at home. Kelebogile lost her first child when she was maybe a year or something. She gave everything, all the things the boyfriend had bought, to Oratile.’ The grudging, subtly bitter attitudes towards their mutual responsibilities, which often provoked squabbles between the two sisters (as we saw in Part II), suddenly took on a new dimension.

These legacies had re-emerged for scrutiny in Boipelo’s and Lorato’s situation, and Lorato was outlining yet more careful balances to be struck. On the one hand, she had to make clear her boyfriend’s willingness and ability to provide for her, allowing her family to recognise it (and him) without making a show; on the other, she had to conceal this support in order to minimise her continuing responsibilities to contribute to her natal household, and to keep demands on her partner reasonable, sustainable, and primarily oriented towards herself. But Lorato also had to demonstrate a reflexive awareness of how her newly acquired resources might have an impact on her relationship with Boipelo and Boipelo’s self-making trajectories, and of how her choices over what to do with those resources might echo and reflect upon the past dikgang of her mother’s sisters. After the loss of her own child, Lorato gave everything she had stockpiled to Boipelo, just as Kelebogile had to Oratile.

I noted several changes in Lorato after the loss of her child and her confinement. Most notable was her attitude towards her younger cousins. She had always been friendly, playful, and at ease with them, like siblings; but now she scolded them and spoke sharply, gruffly sending them on errands or putting them to work. Indeed, her mother’s brothers and sisters, and her grandparents, now chastised her when she was too familiar with them. When I mentioned it, she replied with conviction: ‘Ke motsadi [I am a parent]; I can’t just play with children any more.’ Boipelo, too, took on a new tone of authority; she was preoccupied with finding paid work and left her sister with most of the childcare responsibilities. Both women spoke, dressed, and behaved differently, and they related differently to those with whom they had been most familiar. They had come to be recognised as parents, and as women.Footnote 3

Thus, while pregnancy and birth may leave considerable ambiguity in relationships between new parents, and between their families, in one respect they are unambiguous: they reorganise a woman’s relationship to her natal family. This reorganisation begins in pregnancy negotiations but is perhaps most marked in the management of dikgang after birth. Neither the father nor his family has any formal part to play in taking on or ameliorating these dikgang, and there is little negotiation involved. If anything, he and his kin are explicitly excluded. This is the case even for married couples: with their first child, women will generally return to their natal homestead for confinement after the birth (which is increasingly conducted in a clinic or hospital). I suggest that this unilateral responsibility for the risks of birth and their containment works primarily to produce and reproduce kinship between the woman, her child (if there is one), and her natal family, who will be important figures in her child’s life whether she has married and moved away from them or not – her brothers especially, but also her sisters and parents.

Pregnancy also makes a significant difference to women’s personhood, marking a key success in making-for-themselves. Even if the woman cannot carry the child to term, she nevertheless becomes motsadi (parent) and mosadi (woman) by virtue of her pregnancy. In Setswana, the verb for being pregnant is go ithwala: the verb go rwala, to carry or bear, cast in the reflexive – so that it is something one does to oneself. To conceive or be pregnant, in other words, is to carry oneself or to bear oneself, as well as one’s child – a description that alludes richly to its importance in a woman’s self-making. This new status, of course, is perfected gradually and entails a long learning curve: Lorato had to learn to distance herself from the other children of the yard, to treat and speak to them differently. While both she and Boipelo stumbled and fell over some of these new expectations, they did not cease to be women and parents as a result; pregnancy conferred that role on them, irreversibly. Their pregnancies were incontrovertibly recognisable in the women’s bodies, which publicly marked their sexuality, fertility, and new responsibilities of care. And the dikgang generated by this recognisability – from questions of how to care for the child to claims against boyfriends and the containment of risks posed by postnatal bodies – were all managed within and by their natal family.

Notably, the Legaes spoke of neither Boipelo’s nor Lorato’s boyfriend as motsadi (parent) or monna (man) due to his having fathered offspring. Only Lorato’s boyfriend was identified as monna (man), with explicit reference to his potential marriageability. Rather than pregnancy – in which men are only indeterminately recognisable, and from the dikgang of which they are excluded (and may exclude themselves) – it is marriage that seems to confer on men the recognition that enables them to reproduce and realign kin relations. But reproducing kinship through marriage is also a fraught and uncertain process – as Kagiso’s attempt to marry showed, which I turn to next.

Relationship-in-law does not decay.

‘Ah, it’s not going to work out,’ Kagiso admitted with resignation and a slow smile as he stood under the backyard acacia, absent-mindedly pulling leaves from one of its thorny branches.

It had been two months since Kagiso, his parents, and representatives from his father’s family had formally visited his girlfriend’s house with the hope of asking for her in marriage. They left without ceremony one Saturday afternoon, no one having made any mention of it beforehand. I only heard about it later, when I found Dipuo’s sister’s son drinking tea in the lelwapa and chatting deferentially with his malome Dipuo.

The foray had not gone well. To their collective astonishment and dismay, the girl’s father had refused even to receive the delegation. Much of the men’s chat over tea circled around how strange the father’s reaction had been. When I spoke to Kagiso on his return, he was disappointed and angry, but already strategising for workable alternatives. His parents were less hopeful. Dipuo had reserved comment, simply shaken his head and left for the lands promptly after taking tea. Mmapula, uncharacteristically, spent the whole of the following day lying on the stoep, alternately sleeping, pondering, and talking through the previous day’s disappointment with her daughters. It was perhaps the only time I had seen her stop her incessant work and movement for so long – as if resolution of the impasse lay in her stillness, or as if she were healing a familial wound the way an invalid contains and heals from illness, by staying home.

After his original determination, Kagiso’s resignation came as a surprise to me. ‘Are you just going to give up, then?’ I asked, realising suddenly that there may have been a reason for the family’s silence on the issue in the intervening months. ‘What can I do?’ he countered, smiling again, in his tranquil, reconciled way. ‘You know, he refused even to come out to greet us,’ he said, describing his girlfriend’s father’s odd recalcitrance. ‘He just hid in the house. The wife [his girlfriend’s stepmother] kept telling us he was coming, but he didn’t come.’

Kagiso had been seeing the young woman for two years by then, and he was keen to marry. He had been working assiduously for years to set aside the money needed to pay bogadi, and had since become a respected preacher in a local church; he knew he was a good catch.

But Kagiso had had an inkling for some time that his girlfriend’s father would prove evasive. The man avoided him and refused to greet him when they passed each other in the street. After some ‘research’, as he called it, Kagiso concluded that there was an unresolved conflict with the girl’s mother’s family – likely related to the custody of the girl herself. ‘Maybe he took the child when he wasn’t supposed to, and they are still disputing it,’ he ventured. ‘That would explain why he refuses her to visit her mother’s family in the city.’ Whether the girl’s parents had been married was unclear, and her mother had met a strange and untimely death (which, like the death of Lorato’s baby, rendered it subject to the suspicion of witchcraft). ‘Who can say?’ he concluded, alluding to unsavoury possibilities. ‘But he knows I know something is wrong – that’s why he can’t look at me or greet me.’ I asked whether the young woman had told him anything. ‘Even she doesn’t know the whole story,’ he noted, ‘but there are things she’s not willing to say, even to me. Some other things she has come close to telling me, but in the end she keeps quiet.’

‘He could have come out at least to reject us,’ Kagiso mused, after a pause. ‘He refused because he knew he had no right. Her cousins on the mother’s side told her that man has no say in your marriage. Why is that? The stepmother even said, “You know him – this thing, you have to do for yourself.”’

‘How do you get married by yourself?’ I asked, perplexed.

Kagiso shrugged. ‘Gakeitse!’ he answered – I don’t know. ‘Without the parents? I don’t know. I don’t think there is a way.’

‘Getting married is a problem,’ I observed.

‘I’ll keep trying,’ said Kagiso, flashing his confident smile. It wasn’t clear whether he meant to keep trying with the girl’s family, or just to keep trying to get married – with another girl if necessary. The ambiguity seemed deliberate.

While some of the details around Kagiso’s failed proposal initially struck me as exceptional, the failure itself was common enough. And, on reflection, his apparently singular misfortune had more in common with other failed attempts than I expected. His older brother Moagi, for example, had embarked on marriage negotiations with his then partner and the mother of his son a couple of years previously, while I had still been away. The build-up had been extended. Roughly two years before the negotiations had even begun, he had undertaken construction of a two-and-a-half-room house in the yard of his parents. His parents had insisted on it as a prerequisite to undertaking negotiations on his behalf. When – well over a year later – it was completed and they had made the long journey to the woman’s home village, the woman’s family had been particularly demanding in their bogadi requests (in contrast to the colonial-era expectation Schapera described for the Bakgatla, that whatever the man offered would have to be accepted; Schapera Reference Schapera1940: 87). ‘They wanted a house built for them, so many cows, a nice suit for the old man and dresses for the old woman, money, blankets, everything!’ Lorato recounted. Moagi’s delegation replied that they had heard the request, and then returned home, nonplussed.

When I asked after the situation on my return, nobody was clear about what had happened or where things stood. The process had faded back into a certain inscrutability – much as it had with Kagiso after the initial attempted negotiation. Moagi’s sought-after bride occasionally called to check on her son, who lived with the Legaes; she even came to stay once, for a couple of days. However, the woman now called Moagi’s younger sisters to ask them to send her son to visit, rather than calling Moagi himself, causing everyone discomfort and some consternation. Whether this reflected some breakdown that had happened before the marriage negotiations took place and had railroaded them, or whether it had been caused by the mysterious suspension of the negotiations – or whether, indeed, there had been no breakdown at all – no one could say. ‘Maybe she didn’t want to get married to him, and told her parents to make it impossible,’ Lorato surmised. ‘Or maybe the parents didn’t like him and made it impossible by themselves. Gareitse,’ she concluded, as she often did – we don’t know. The relationship had receded into opacity.

Marriage stands at the heart of the unique structural ambiguities and flexibilities of Tswana kinship. Historically, Tswana marriage preferences were an anomaly among Southern African kinship systems: they accommodated marriages between cross-cousins, the children of siblings of the opposite sex (e.g. a man’s son with his sister’s daughter), and parallel cousins, or the children of siblings of the same sex (e.g. a man’s daughter with his brother’s son; Kuper Reference Kuper2016; Radcliffe-Brown Reference Radcliffe-Brown, Forde and Radcliffe-Brown1950; Schapera Reference Schapera, Forde and Radcliffe-Brown1950).Footnote 1 Over time, these preferences created an overlapping and indeterminate field of kin relations, in which any given kin tie might be ‘at once agnatic, matrilateral, and affinal’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1991: 138, emphasis in the original) – meaning that, in practice, kin relationships were susceptible to constant contestation and renegotiation, oriented around relative wealth, power, and so on (ibid.; see also Comaroff Reference Comaroff, Comaroff and Krige1981). While it was more often nobles who married kin than commoners (Schapera Reference Schapera1957), parallel cousin marriage – and the principles of ambiguity, flexibility, and pragmatic responsiveness to social variables it generated – remained one ideal form of union (an ideal that appears to persist in other areas of Botswana; see Solway Reference Solway2017a: 317 on ‘Formula One’ marriages among the Bakgalagadi). What I want to emphasise here is that these ideals were markedly insular: rather than simply prioritising the extension of kinship to other, unrelated households, marriage was in many ways preoccupied with containing, reproducing, and reorganising existing kin relationships (perhaps especially following the decline of polygyny; see Solway Reference Solway1990).

Tswana marriage has long been characterised as a drawn-out, indeterminate, often incomplete, and potentially reversible process – rather than a definitive event or state of being – which reproduces and compounds the structural ambiguities described above (Comaroff Reference Comaroff1980; Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977). By contrast, contemporary anthropological accounts suggest that marriage is increasingly geared towards foreclosing indeterminacy. Where the stages of marriage once unfolded over years, they are now concluded rapidly and all at once, with bogadi paid, vows made, and spectacular celebrations happening in one extended event (Solway Reference Solway2017a; van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010; Reference van Dijk2017). Government has taken a more prominent role, formally registering marriages and overseeing mass ceremonies that generally precede the ceremonies and celebrations organised by kin. Where marriage was once an explicitly intergenerational undertaking – a father paid bogadi for his son’s bride; a sister’s bridewealth enabled her brother’s marriage and established her claim on his daughter in marriage for her son (Kuper Reference Kuper2016: 274) – intergenerational kin involvement now seems to be waning (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Solway Reference Solway2017a).

At the same time, marriage itself has been in sharp decline, since at least the advent of labour migration in the region (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Pauli and van Dijk Reference Pauli and van Dijk2017; Townsend Reference Townsend1997). Explanations for this trend have surmised that, in an era of waged work, both men and women are less reliant on one another’s labour and resources, and less willing to put up with the constraints of married life; and that men’s natal families in particular have greater reason to want to retain their contributions at home (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Townsend Reference Townsend1997). Links have also been made to growing inequalities, with the lavish displays of conspicuous consumption that now characterise weddings increasingly a privilege of the elite (Pauli and Dawids Reference Pauli and Dawids2017) or bound up with emerging loan industries and the acquisition of substantial personal debt (James Reference James2017; van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010; Reference van Dijk2017). And yet – as the conversation at the beginning of Part III suggests – marriage remains a highly desirable goal for men and women, if an elusive ideal. Approaching marriage in terms of recognition and the dikgang that accompany it, I suggest, shows that this elusiveness is not only a question of political economy but also remains linked to ambiguity. Rather than being eliminated, ambiguity seems to have been relocated from marriage as such to the pre-wedding phase – and, beyond that, into familial histories. Aside from the question of financial strategies and resources, the failure to marry may also be a question of the costs of seeking definitive clarity in intergenerational relationships, which rely on a degree of ambiguity for their continuity. In this sense, I suggest that contemporary Tswana marriage remains preoccupied with the management of existing kin links – showing an uncanny resonance with pregnancy and its reorganisation of women’s natal kin relationships.Footnote 2

Ideally, marriage negotiations involve a step-by-step process of seeking formal recognition for a conjugal relationship. At every stage, acts of seeing/showing, speaking, hearing, and knowing are explicitly foregrounded, requiring other acts of recognition in turn. Each of these acts explicitly makes the previously hidden seen (Werbner Reference Werbner2015), to wider and wider groups of people. The potential interpretations of what is newly grasped must be carefully managed, especially given the historical tendency towards indeterminacy and dispute (Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977).

After conducting the relationship itself with great secrecy, Kagiso had to tell his parents of his intentions, disclose his financial status to them sufficiently to demonstrate his ability to pay bogadi, and ask them to call ‘the uncles’ (as he described them) to speak to his potential in-laws. His parents, having heard his request, had to identify, call, and speak to appropriate kin (Dipuo chose his younger sister’s son and the son’s wife); demonstrate the viability of his proposal to them; and then ask them to assist in repeating the process of speaking, making known, and asking with Kagiso’s potential in-laws. The cycle continues right through wedding-related rituals: as Solway (Reference Solway2017a: 316) notes, ‘seeing’ and showing bogadi cattle have long been crucial aspects of conferring recognition on a marriage and on the networks of relationships that enable the achievement of a wedding, which the cattle make evident – although they, too, are subject to multiple interpretations (ibid.; see also Comaroff Reference Comaroff, Comaroff and Krige1981: 172). Today, showy white weddings, photographs and videos, and social media posts with customised hashtags seek similar recognition in novel ways, extending the recognisability of the couple’s success, and that of their kin, in time and space (Solway Reference Solway2017a: 313; see also Pauli and Dawids Reference Pauli and Dawids2017: 23).

But at each stage, these processes face an increasing risk of disagreement, refusal, failure, or jealousy, among an ever expanding group of people – dikgang that may adversely affect the relationship of the partners and of the negotiating kin, whose contributions to the process remain key. Even where couples seek to avoid these difficulties by ‘marrying themselves’, as van Dijk (Reference Pauli and van Dijk2017: 36) notes, potentially fraught disclosures of the marrying couple’s resources to their respective kin run comparable risks of inviting jealousy or refusals to assist. When Kagiso’s would-be father-in-law refused to see the delegation or hear their request for his daughter’s hand, he not only refused to recognise the relationship but also showed Kagiso’s parents and negotiators that refusal, refusing them in turn. The refusal undermined Kagiso’s hopes for marriage and his claims to adulthood; like Lorato’s failed house, Kagiso’s failed proposal frustrated and stalled his ability to make-for-himself. But the repercussions were greater, in proportion to the number of people concerned and the degree of exposure involved: it was not only Kagiso whose ability to manage people, relationships, and dikgang was called into doubt, but also the ability of those who had gone to negotiate for him. The failure cast doubt on his family’s ability to secure marriage for him, and on their status relative to that of their potential in-laws as well.

The recognitions involved in marriage negotiations demand other disclosures and recognitions in turn, and so such refusals may also be explicit concealments: not only of relative resources, but also, as Kagiso speculated with regard to his partner’s father, of the unresolved – or unresolvable – dikgang of the past. By Kagiso’s assessment, the would-be father-in-law’s refusal to receive Kagiso’s kin was most likely a question of keeping the fraught, ambiguous history of his relationships with his child, his (deceased) partner, and her family hidden, removed from further reflection or interpretation. In part, Kagiso’s speculation was an effort to cast the failed proposal in a specific light: as a kgang that was irreconcilable because it was oriented around his partner and her family, rather than him and the Legaes. While this framing didn’t change the outcome for Kagiso, as an explanation circulated among family it served to shelter them from any further intransigent conflicts around an issue that was out of their hands, to sustain Kagiso’s own capacity to self-make, and to mark an insuperable distinction between kin and non-kin (a point to which we will return). But Kagiso’s speculation also indicates an expectation that marriage negotiations routinely risk forcing long-standing, unresolved familial issues out of suspension and back into play – whether between a potential spouse’s own parents or between the parents’ respective siblings and extended kin, the full range of whom will be called on in various ways for the marriage to succeed. It taps into an assumption that marriage negotiations risk rendering the ambiguities of those relationships recognisable, often uncomfortably so, to a generation among whom they were previously unknown and for whom they might pose further problems. Marriage negotiations also offer a rare means of resolving such long-standing dikgang – but, in practice, they often exacerbate them.

Thus, for example, were Boipelo to get married – as Dipuo reminded her at the beginning of this part – the payment of bogadi from her marriage would go to Dipuo, her mother’s father, unless her own father managed to pay bogadi for her mother first. The impending marriage of daughters was often a major reason given by men I knew in their forties and fifties, having set up households with their wives and children long before, for finally wanting to pay bogadi (see also White Reference White2017). Knowing that bogadi would soon be received for marrying daughters meant that they could finance their own bogadi with greater confidence. Children’s marriages, then – daughters’ marriages in particular – enable the formalisation of their parents’ marriages, resolving any suspended questions of their status, their respective responsibilities, inheritances, and so on (a development that suggests that marriage remains an intergenerational matter, but in inverted terms). Ideally, the distribution of bogadi from Boipelo’s father among Dipuo’s family, and then from Boipelo’s would-be husband among her parents’ family, would strengthen and reinforce their relationships to one another, reconcile past misunderstandings, and provide a new framework of relating. Both Boipelo and her partner, and her parents, would also achieve a certain degree of recognised independence, as households and as individuals. (The Tswana term kgaoganya – both ‘sharing’ and ‘separating’ – also connotes ‘resolving’.) At the same time, should delays or disputes about the payment of that bogadi emerge between Boipelo’s future husband’s family and her parents, or between her parents and her mother’s parents, the confusion of stakeholders and proliferation of claims – and the questions raised about what those delays or disputes suggested about the people and relationships involved – could well destabilise relationships even further and derail either marriage altogether. Certainly, the inability of Boipelo’s father and his kin to successfully negotiate the dikgang of his own ‘marriage’ without the help of his daughter’s marriage would also render his capacity to cope with dikgang suspect, thereby further undermining his position.

Similarly, had Kagiso insisted on negotiating his marriage with his girlfriend’s maternal kin, the causes of animosity between her maternal and paternal kin would have had to be articulated and addressed. However, if – as seems likely – the issues at the heart of Kagiso’s would-be father-in-law’s evasiveness were deeply insoluble, pushing his case could have risked irreparable ruptures in the young woman’s family, and might have foreclosed the possibility of marriage. In the end, her father having refused to recognise Kagiso’s overtures, Kagiso’s girlfriend moved north to visit her maternal kin. Her relationship with Kagiso faded into obscurity not long afterwards. Having failed to negotiate the dikgang of recognition, Kagiso found himself back at square one, his role and relationships within his own family unchanged.

Beyond the often cited pressures of expense – whether for bogadi or weddings – it is perhaps the difficulty of addressing long-standing, suspended dikgang within families, as well as managing the dikgang that emerge between families, that introduces ‘new forms of slowness’ (Solway Reference Solway2017a: 218) in the negotiating stage, making marriage so difficult to achieve in contemporary Botswana. Even more than pregnancy, marriage is a deeply fraught but critical means of reorganising and reproducing families. And this fraught creativity affects not only prospective spouses and their children, but also the generations that precede them. The tension I have described attaches not simply to questions of exchange or love, affinity or procreation, but to the dikgang generated by recognition. At the same time, marriage is one of the few processes that offers the structural possibility of resolving the suspended dikgang of the past, while enabling the reproduction of kinship into the future – leaving Tswana families, and particularly their men, in something of a quandary.

As Gulbrandsen noted for the Bangwaketse, ‘no bachelor can ever be fully recognised as a man’ (Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 12; pace Lafontaine Reference La Fontaine1985: 162). At stake for Kagiso was not only a ‘form of adulthood’ (van Dijk Reference van Dijk, Dekker and van Dijk2010: 290) but also a new role in the family, in which he could ‘tak[e] decisions in family affairs, inheritance and the ownership of property’ as well as negotiating the marriages and disputes of others (ibid.; see also Durham Reference Durham2004; Townsend Reference Townsend1997). In Setswana, a man marries (o a nyala) whereas a woman is married (o a nyalwa); in asserting that relative agency, an important measure of social and political personhood is conferred that goes beyond the man’s ability to accumulate or provide resources (cf. Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 15). I suggest that such recognition emerges as a result of a man’s proven willingness and ability to make the hidden seen, by drawing both his relationship and his capacity to marry to the awareness of a wide range of kin and non-kin, and by successfully navigating the risks that emerge with that awareness. In other words, his recognition is first achieved, and then continuously reproduced, in the acquisition and management of pronounced, perpetual – one might even say chronic – dikgang. The ability to tackle dikgang successfully with a vast range of kin and affines, which a man demonstrates by securing his marriage, and the continued responsibility for further negotiations he will bear as a married man, establish his suitability to participate in other public forms of negotiation – whether they be additional marriage arrangements or the hearing of cases at kgotla.

Marriage is not the only, or final, marker of a man’s adulthood, of course. Setting up a household for a wife and children (Townsend Reference Townsend1997: 409), his father’s death, and his own record of participation in decision making (Durham Reference Durham2004: 596) all mark further projects of self-making in which a man’s adulthood, and his personhood, grows. But like marriage, these projects involve new forms of exposure and recognition, as well as the acquisition of other dikgang that require reflection and negotiation, of the sort explored throughout this book. His success in handling the dikgang of recognition leading to marriage both creates opportunity for and forecasts his potential in addressing these additional dikgang. In this sense, while marriage may seem to have become irrelevant to a man’s rank and status since the advent of waged labour (Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 15), it nonetheless remains a key aspect of his self-making and his aspirations to ethical personhood.

Kagiso was ultimately successful in negotiating a marriage several months after I left the field – perhaps a year and a half after his previous attempt. He had met his wife-to-be at the local home-based care NGO where they both worked. I had met her a few times when she was spending time with Kagiso at his shop, although usually she stayed in his car and was at pains to avoid anything but the most basic greeting. After Kagiso’s initial negotiations with her family, she still lived in her own rented house in the village, but I heard that she had become warm and friendly with the family at home, regularly visiting in the afternoons and often coming to stay with Kagiso at night. All that remained in Kagiso’s marriage trajectory were the ceremonies: at the district commissioner’s hall, at the church, and at the two families’ natal homes. The expense and logistics involved in the ceremonies meant that they would be some time in coming; dates a year and longer after the initial negotiation were being considered. However, the two families’ successful management of the initial marriage negotiations laid the groundwork for equally successful joint responses to future issues – the critical factor in maintaining flexible and creative kinship bonds in the context of inevitable dikgang. It is this proven capacity to share and jointly negotiate dikgang that gives affinal kinship sufficient persistence that – as the proverb which opened this chapter suggests – it does not decay, even if the married spouses themselves part.

In the context of the AIDS epidemic, however, the recognition of relationships has taken on new risks, and associated dikgang threaten to take on new forms while continuing to work in ways familiar from the discussion above. It is to the dynamics of recognition in the epidemic, and the dikgang that result, that I turn next.

‘And … she’s pregnant.’ Lesedi and I sat in shock for a few moments. It had taken some time to eke this information out of her; she had refused to tell me anything on the phone, other than that her cousin Tumi was in hospital.Footnote 1 She had called home, asking to use the Legaes’ postal address to access a good hospital that would be less crowded than those in the city, but she would explain no further. Gradually, as we sat on the long benches lining the small courtyard of the maternity ward, the story emerged.

Lesedi had found Tumi in the middle of the night, collapsed in the hallway of the house they shared with two other maternal cousins and Lesedi’s daughter in the capital, Gaborone. Tumi had been weak and sick for some time, and had lost weight. She had had episodes when she talked nonsensically. The signs were straightforward enough and saved articulating the painfully obvious: apparently Tumi herself had known for some time that she was HIV-positive, although it was only the routine test at the hospital that had brought the fact to the attention of her cousin. The pregnancy was an added surprise to everyone, Tumi included.

The last time I had seen Tumi had been at a family wedding some months before. Even then I hadn’t seen her much; she had come home with a new boyfriend and was reluctant to bring him into the yard. A long-term relationship with another man had ended dramatically not long before, upon her discovery of photograph albums stashed under his bed recording his marriage to another woman in his home village. By all accounts Tumi was smitten and enthusiastic, and the new relationship was happy and hopeful.

Now, on the hard hospital benches, Lesedi began to tell a different story. Tumi had met the new man at the clinic where she worked, and where he was a regular client. They had begun seeing each other. He talked of the untimely loss of his first wife and about his desire to remarry. And then the clinic doctor sent Tumi’s workmate a text message, asking her to warn Tumi that she was getting involved with a man who was HIV-positive. But, by that point, Tumi was too much in love to care. ‘Or maybe the workmate didn’t tell her right away?’ I suggested. ‘People can be jealous.’ Lesedi shrugged. ‘Gareitse,’ she said. ‘It’s possible. I think she just loved the idea of getting married. You know, what girl doesn’t want that?’

Around us, women in advanced stages of pregnancy lounged about in bathrobes, their hair wrapped in scarves, chatting with visiting family members. Lesedi took in the scene with a flat expression, the usual glint of mischief and knowing irony gone from her eyes. She explained that the doctor had disclosed more than his patient’s status – which Tumi, working at the clinic’s registration desk, would probably have been able to glean from his file in any case. He had explained that the man’s first wife had died of AIDS and that the man himself had nearly died as well. The doctor surmised that the man carried a particularly virulent strain of HIV, and said as much in his text to Tumi’s colleague. It was an astonishing breach of confidentiality, if not unprecedented; from early on in the epidemic, the relative ethical merits of patient privacy versus potential risk to loved ones had been hotly debated. For Lesedi, the question of confidentiality mattered less than the danger her cousin was now in.

Three months later, Tumi had discovered that she, too, was HIV-positive. She mentioned it to no one but her new boyfriend, who quickly began to withdraw. Lesedi felt that the stress of the situation was what had begun to take its toll on Tumi, making it impossible for her to cope with the combined effects of the virus and – as was now apparent – a pregnancy.

‘Where is this guy now?’ I asked. The situation angered me: the man’s apparent capriciousness, Tumi’s willingness to trust him, her illness, the baby, the shockwaves sent through everyone else’s lives, his convenient absence, the impotence of anyone to do anything about any of it. Lesedi shrugged again. She wasn’t sure if Tumi was still in touch with him but suspected she was. He hadn’t shown his face. Besides Lesedi, the only other regular visitor Tumi had was the married man she had been with before. She explained that I couldn’t go in to see Tumi myself – she was being treated for tuberculosis and was limited to two regular visitors.

We sat in silence for a while, punctuated only by the occasional ‘Mxm!’, a sharp teeth-sucking sound of annoyance and derision. We watched the round, bath-robed women basking in the sun. Two soldiers walked by in camouflage and high, polished boots, entirely out of place. Our disgruntlement latched onto them as they passed. ‘Ah! Men are useless,’ said Lesedi. ‘Imagine. What kind of person can do that?’ We fell quiet, each thinking of the number of men we knew who had abandoned women to their pregnancies; and the number of women we knew whose pregnancies had helped them secure some relationships and end others. It didn’t always involve life-threatening illness, but we both knew plenty of people, men and women, who could do similar things in similar circumstances. That didn’t diminish the ethical imperative of Lesedi’s question, though: what kind of person does these things? And what does it mean for them, for those embroiled in the situation, for the networks of their relationships, and for us?

Lesedi and Tumi were both from the far north-east corner of the country, a day’s drive away. Their mothers were sisters and they had grown up together. They stayed with Lesedi’s seven-year-old daughter and two other maternal cousins in a spacious, three-room house in one of the new neighbourhoods springing up around the capital, spanned by rutted, unpaved roads and convenient to a profusion of shopping malls. They went home infrequently, but always for major holidays and events. The grandmother who had raised them was diabetic and increasingly frail. Lesedi had built a roomy house in their natal yard, but both women felt that there was little left for them there and that the obligations of life at home were too consuming.

With an expression of surprised guilt, Lesedi admitted that she had been thinking about asking Tumi to move out. She felt that Tumi had not been contributing enough at home, and Lesedi was overwhelmed with the demands of her own university schooling and caring for her child. Of course, she could not ask such a thing now, but awareness of her responsibility for the additional care Tumi would require in the coming weeks and months showed in the strain on her face. I asked her whether she planned to tell her grandmother at least – knowing that, in such a situation, the elderly woman would be certain to come down to help. Lesedi hung her head and shook it slowly. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said. ‘Kana she’s old, it can kill her. I’ll just tell them about the pregnancy – it’s bad enough.’

Tumi’s tale resonated with many others I heard. Whenever I became naïvely exasperated with friends for putting themselves in danger of contracting HIV, I was met with similar explanations: a shrug and an assertion that love, the promise of marriage, or the desire for a child made sense of the risk (see the description of AIDS as a problem of love in Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 3; see also Hunter Reference Hunter2010). The dikgang that surround the goals of pregnancy or marriage in usual circumstances, with far-reaching consequences of their own, put this reaction in context. HIV is rendered one of many risks to be borne in the project of making the family and the self, one of many potential crises to be faced in that process. It is a risk people are willing to take in order to build conjugal relationships, which open up opportunities to self-make and to refigure kin relations. In this sense, it is a risk of the same order as others I have described above, many of which also present the threat of illness or death. Indeed, Batswana actively absorb HIV and AIDS into the range of dikgang associated with conjugal intimacy as a crucial means of living with the epidemic.

Even practices that seem to offer little more than an egregious danger of infection – like having multiple partners, as Batswana often do – might be understood to ameliorate the other risks inherent in intimate relationships. Before antiretroviral (ARV) treatment was made widely available, Klaits notes that men in the Apostolic church he studied kept multiple partners ‘in order to “protect themselves” (go itshireletsa), ironically the same phrase used in health campaigns to promote condoms’ (Reference Klaits2010: 131). Klaits links this ‘protection’ to a distribution of love that ensures emotional well-being and the improved chance of return on one’s investments in others. Such protection is no less necessary in a time of widespread ARV treatment. Indeed, the imperative to keep a relational self fragmented and concealed, in order to protect oneself and others against witchcraft, predates and outstrips the particularities of the pandemic (see Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001). It is a sort of protection decisively linked to managing and containing recognisability, to controlling who can see, speak about, or know a person, on what terms, and to what extent. And it suggests that this protection against relational indeterminacies and risks is as important as – or more important than – protection against the virus (Hirsch et al. Reference Comaroff and Roberts2009: 19).