The time of hate in which we live dictates that we answer fully and collaboratively the challenges of all forms of violence, including racism, antisemitism, misogyny, transphobia and other types of bigotry. In a time when the classroom is subject to ‘new forms of subterfuge, secret recordings, and professor watch lists’,Footnote 1 it is all the more important to bring our academic work to build more equitable, sustainable communities, rather than exploiting trendy topics that service academic advancement and not students and community members. One of the core values of the humanities lies in understanding the human condition in different contexts, and Shakespeare’s oeuvre as a cluster of complex, transhistorical cultural texts provides fertile ground to build empathy and critical thinking. Developing ‘independent facility with complex texts’, as Ayanna Thompson and Laura Turchi’s research shows, enables ‘divergent paths to knowledge’, which promotes equity and diversity.Footnote 2 Indeed, as Timothy Francisco and Sharon O’Dair point out, the heuristic value of complex texts lies in their ability to expose ‘the oppression by a status hierarchy’ and encourage the formation of hypotheses and critiques.Footnote 3

In this article, we examine new theories and praxis of listening for silenced voices and of telling compelling stories that make us human. Elucidation of our Levinas-inspired theories of the Other is followed by a discussion of classroom practices for in-person and remote instruction that foster collaborative knowledge building and intersectional pedagogy. The moral agency that comes with the cultivation of ethical treatment of one another can lead to political advocacy. Special attention is given to race, gender and the exigencies of social justice and remote learning in the era of the global pandemic of COVID-19 (2019 novel coronavirus disease). The new normal in higher education, which is emerging at the time of writing, exposes inequities that were previously veiled by on-campus life and resources. Even as they are cause for grief and anxiety, the inequities exposed by COVID-19 can spur change for the better.

Levinas’s Radical Ethics and Shakespeare

Ethics is an essential, but often missed, term in discussions of Shakespeare, even though interpretations and performances lay ethical claims upon the canon. An ethics-first pedagogy promotes awareness of and compassion towards those most vulnerable to oppression and attacks from White supremacists. Ethics refers to mutually accepted guidelines on how human beings should act and treat one another, and, in particular, what constitutes a good action. Emmanuel Levinas posits that relations with the Other pre-exist any kind of being, thereby making ethics the most primary philosophy. In Levinas’s theory, the human being is constituted in, through, by and for the Other – in the face of the Other – first and foremost. Rather than assuming that the I or ego first exists via its own consciousness and then attempts to interact with others, Levinas argues that it is only through the Other that the I emerges at all; this interaction occurs pre-consciousness, pre-ego formation, pre- or ‘otherwise than’ being. For Levinas, then, ethics or moral behaviour is not a supplement or an add-on to an already fully formed subject; conversely, it is the basis upon which the subject is formed, the primary philosophy itself, the foundation of all.

Teaching Shakespeare offers opportunities to help students to cope with these difficult times, to examine their world critically, to learn how to respond respectfully and sensitively to others, and to sharpen their intellect. Drawing on Levinas’s philosophy, Alexa Alice Joubin and Elizabeth Rivlin have argued that literary criticism carries strong ethical implications. A crucial, ethical component of interacting with a literary text is one’s willingness to listen to and be subjected to the demands of others, creating moments of ‘self and mutual recognition’.Footnote 4 Seeing the others within oneself is the first step towards seeing oneself in others’ eyes. The act of literary criticism is founded upon the premise of one’s subjectivity, the subject who speaks, and the other’s voice that one is channelling, misrepresenting or appropriating.

Levinas employs Shakespeare’s plays as illustrative examples of his philosophical concepts, explaining that the plays render his ideas into a more tangible level or register. Consequently, Levinas sees Shakespeare and other writers such as Dostoyevsky not as conventional moralists who advocate poetic justice and decorous human behaviour but, rather, as writers concerned with ethical imperatives and questions of social justice. Within a framework where ethics are prioritized over knowledge production, students and educators are responsible for the preservation of the alterity of the Other, even as they make the obscure known by plucking it out of the abyss of unknowable otherness. The ethical creation of knowledge works against ‘the imperialism of the same’, an assertive move of acquisition that forces unfamiliar things to ‘conform to what we already know’.Footnote 5 Levinas’s principle of the Other can help us to hear the voices of the Other by avoiding the tendency to know something merely as our own ideological construct.

For Levinas, Shakespeare may be a means to engage with, rather than only consciously understand, an ethics-first philosophy. His comments concerning Shakespeare’s plays and Dostoyevsky’s novels indicate his commitment to radical ethics in the literary imagination. In his Humanism of the Other, Levinas sees Shakespeare dramatizing his ethics-first philosophy based on one’s moral obligation to the other before he himself conceptualized it in philosophical terms centuries later. Levinas uses King Lear to illustrate his notion of ‘substitution’, or ‘putting oneself in the other’s shoes’, as much as is possible, while still maintaining the alterity and respecting the differences of the other.Footnote 6 There is profound reciprocity between notions of self and the Other. The subordination of I to You constitutes a subjectivity that recognizes an alterity within. Levinas writes that ‘It is through the condition of being hostage that there can be in the world pity, compassion, pardon and proximity – even the little there is, even the simple “After you, sir”.’Footnote 7 The forcible subjection to the Other is the precondition for ethical action.

A Levinas-Inspired Pedagogy

Levinas’s radical ethics thus underscores the importance of teaching the humanities, particularly literature. Levinas’s philosophy can inform our approaches to teaching, our methods for engaging students and creating compassionate, ethical, intellectually stimulating learning environments – whether classes are face-to-face, online or in a hybrid format. This approach to teaching includes, in effect, a lesson in ethics, both internal and external to the assigned course materials and course subject matter. A Levinas-based pedagogy considers how instructors treat students and how students treat each other, countering the current trend to bully one’s opponent on social media. In today’s intensely heated political climate, it is more important than ever to ensure this fundamental, primary ethical principle is in place.

Teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple protests against injustice around the world, we as instructors have seen this need for care of others – and of the self – foregrounded. Writing pre-pandemic, Ayanna Thompson stresses the need for instructors to take care of themselves when opening up social justice issues, such as anti-racism, in the class discussions, noting the ‘emotional labor’ such teaching requires.Footnote 8 Since that time, this need for self-protection – and for instructors to make sure students show compassion and concern for themselves and each other – is even more pronounced. Although it may be challenging, and at times exhausting, working to ensure that students treat each other with respect and dignity in the classroom and in online discussions, where students and/or instructors may lapse into inconsiderate and/or abusive behaviours, it is crucial to establish and maintain a classroom truly committed to countering hate.

In face-to-face classrooms, we can emphasize collaborative learning and active student participation, focusing on Levinas’s operative concept of the saying (le dire) in fostering an ethics-first classroom. For Levinas, the importance in communication exists in the saying, or the signifying itself – one’s reaching out to the other. It is the communicating itself that matters. Levinas’s theory of communication – the saying underlying the said (le dit) – relies on the self’s one-sided obligation to the other, the concept of proximity between people and the face-to-face interpersonal connection between them. The said refers to the semantic content of an utterance and the ‘different modalities by which a subject masters the world by assimilating it to the measure of consciousness’, such as narratives, history and discourses. The said is an expression of contents. In contrast, the saying is ‘expression without content’ where the subjectivity emerges as exposition. The saying is an act of signifying that ‘I am for the other.’Footnote 9 In Otherwise than Being, Levinas writes:

In starting with sensibility interpreted not as a knowing but as proximity, in seeking in language contact and sensibility, behind the circulation of information it becomes, we have endeavored to describe subjectivity as irreducible to consciousness and thematization. Proximity appears as the relationship with the other, who cannot be resolved into ‘images’ or be exposed in a theme.Footnote 10

‘Proximity’ rather than ‘knowing’ allows for ‘language contact and sensibility’ (or ‘saying’) – the reaching out to another without attempting to reduce the other into thingness, an objectified ‘image’ or reductive ‘theme’ (or the ‘said’). Teaching for the ‘saying’ in the face-to-face classroom can help to create and maintain a compassionate learning environment.

These same principles apply to online teaching, but they should not be implemented in exactly the same way as they are in a face-to-face class. It is important to consider how best to establish a Levinas-inspired classroom that is designed specifically for remote delivery, rather than replicating a face-to-face one. Therefore, as instructors, we need to consider how to use technology carefully to enhance rather than impede the goal of a Levinas-inspired pedagogy. To do so, it may be helpful to think through issues concerning Levinas’s notions of ‘proximity’ in light of technology and communication in remote teaching environments.

Although Levinas does not speak directly to matters of online communication, as his work pre-dates the Internet, his ideas lend themselves to matters of technology, mediation and intersubjective communication, as Lisa S. Starks’s research has shown. Levinas’s theory provides a way into thinking about teaching online that opens up its transformational potential even while alerting us to its limitations, presenting them as productive challenges rather than obstacles to an ethics-first virtual literature classroom. Useful in mediated communication is Levinas’s term ‘proximity’. Although, in general usage, the word denotes physical closeness or lack of geographical distance, in Levinas’s theory it may suggest something quite different – a figurative rather than literal sense of ‘closeness’, with a moral imperative. Importantly, as Levinas explains, ‘The relationship of proximity cannot be reduced to any modality of distance or geometrical contiguity.’Footnote 11 Levinas’s notion of proximity has been applied to analyses of mediated communication and online and offline relationships. ‘Proximity’ entails an ethical obligation beyond remaining geographically close or being present physically. Richard Cohen cautions that ‘one can objectify’ the ‘other’s face, “reading” from it symptoms, ideologies’, for ‘The face can always become a mask.’Footnote 12 Objectification and reduction of the Other most certainly can and does occur in online relationships, including in online classroom environments – but the same can also be true for face-to-face relationships and traditional classrooms. Importantly, though, the ‘saying’ rather than the ‘said’, Levinas’s face-to-face encounter, may occur via mediated communication – be it via a letter sent by snail-mail, an email message, a student’s discussion post, or a virtual interaction, just as it may – or may not – occur in ‘physical’ face-to-face interactions.

Teaching Multiplicity through Radical Listening

A number of analogue and digital pedagogical tools could promote radical listening – proactive communication strategies to listen for the roots of stories that allow for ‘an egality between teller and listener that gives voice to the tale’.Footnote 13 Students learn to listen for motives behind stories, rather than the plot of the narrative. As a cluster of complex texts that sustains both past practices and contemporary interpretive conventions, Shakespeare provides fertile ground for training in radical listening.

Specifically, radical listening draws on the methodology of strategic presentism. Coined by Lynn Fendler, strategic presentism acknowledges the present position of the interpreters of the humanities and empowers them to make a difference by methodically using our contemporary issues to motivate historical studies.Footnote 14 By thinking critically ‘about the past in the present’Footnote 15 – as does the #BlackLivesMatter movement – students analyse performances and dramatic texts with an eye towards changing the present. By foregrounding the linkage between early modern English drama and contemporary ideologies in global contexts, we address ‘the ways the past is at work in the exigencies of the present [including] the long arc of ongoing processes of dispossession under capitalism.’Footnote 16 In this framework, the past is not an object of obfuscatory, irrelevant knowledge that is sealed off from our present moment of globalization, but rather one of many complex texts to enable us to rethink the present.

Since strategic presentism decentres the power structures that have historically excluded ‘many first-generation students, students of colour, and differently abled students’,Footnote 17 more students – especially underprivileged ones – are empowered to claim ownership of Shakespeare. The approach has also revealed Shakespeare to be a cluster of texts for critical analysis, rather than simply a ‘White’ canon with culturally predetermined meanings.

In pedagogical practice, this means fostering connections among seemingly isolated instances of political and artistic expressions. It is paramount, in a time of hate, to cultivate the ability to recognize multiple, potentially conflicting, versions of the same story. Unambiguous, clean and sanitized, singular narratives usually occur during a dark moment of history. Literary ambiguity, as Alexa Alice Joubin argues, ‘helps connect minds for global change’. The ambiguity is a welcome gift for the uninhibited mind, for ‘it has been an ally of oppressed peoples in the Soviet Union, Tibet, South Africa, and elsewhere. The ambiguity allowed them to express themselves under censorship.’Footnote 18 Our Levinas-inspired pedagogy of radical listening takes into account the ambiguities and evolving circumstances that affect interpretations of the texts. A singular, modern edition of Shakespeare’s plays is no longer the only object of study. Instead, it is one of multiple nodes that are available for search and re-assembly. Teaching Shakespeare through translated versions and performative possibilities draws attention to dramatic ambiguities and choices that directors must make. In dramaturgical terms, it helps students to discover ‘how the same speech can be used to perform … radically divergent speech acts’.Footnote 19 Instead of taking a secondary role by responding to assignment prompts, students examine the evidence as a group, annotate the text and video clips, and ask and share questions that will, at a later stage, converge into thesis statements. Students no longer encounter Shakespeare as a curated, editorialized, pre-processed narrative, but as a network of interpretive possibilities.

For example, directors filming King Lear must carve a path between theatrical elements (‘language of drama’) and discrete ‘cinematic … codes of communication’.Footnote 20 The significance of King Lear goes beyond the traditional binary of nihilism and redemption.Footnote 21 As students approached the tragedy, some of them invariably became hung up on the question of sympathy. While their interpretations often hinge on their ability to sympathize with Lear,Footnote 22 the collaborative exercises revealed that the question of redemption need not and should not be the sole focus of interpretive strategies. Lear can be both sympathetic and unsympathetic, both relatable and not relatable.

Further, it is productive to read Shakespeare in multilingual contexts. Consider, for example, these lines by Macbeth in response to the knocking on his gate shortly after he murders King Duncan: ‘This my hand will rather / The multitudinous seas incarnadine, / Making the green one red’ (2.2.59–61). The echo of ‘incarnadine’ and ‘red’ is serendipitous, but the deliberate alternation between the Anglo-Saxon / Germanic and the Latinate words suggests two pathways to consciousness and two perspectives on the world. As in the exercises about textual variants, students were called upon to translate into other languages and into modern English such instances of repetitions with a difference.

The inquiry-driven collaboration also turns speakers of other languages into an asset, particularly international students who are not native speakers of English. All too often they are seen as a liability, but their linguistic and cultural repertoire should be tapped to build a sustainable intellectual community. One way to excavate the different layers of meanings within the play and in performances is to compare stage and film versions from different parts of the world. Alexa Alice Joubin has encouraged her students to translate a key passage in a canonical English text into other languages (and to report back in English) to diversify the class’s interpretive approaches.Footnote 23 Students may be studying a foreign language, or they may speak a language other than English at home. Students are thus able to bring into the classroom new voices and new ways of seeing the world. This collaborative pedagogy reflects the need for racialized globalization to be understood within hybrid cultural and digital spaces. Team projects also encourage students’ ethical responsibility to each other as they grow from recipients of knowledge transfer to co-creators of knowledge.

Sharing their linguistic skills, students also looked up historical translations of the plays. Caliban’s word, ‘language’, is translated variously in different languages. For example, Christoph Martin Wieland translates the word in German as redden, or ‘speech’. In Japanese, it is rendered as ‘human language’, as opposed to languages of the animal or computer language. Take another word from The Tempest, for example. Prospero announces in Act 4, Scene 1, that ‘our revels now are ended’ (148). The word ‘revels’ in the Elizabethan context refers to royal festivities and stage entertainments, but it carries different diagnostic significance in translation. Christoph Martin Wieland uses Spiele (‘plays’) and Schauspieler (‘performer’) to refer to Prospero’s masque and actors (‘Unsre Spiele sind nun zu Ende’ in German). Sometimes, translators working in the same language have different interpretations. Liang Shiqiu translated it as ‘games’ in Mandarin Chinese in 1964, alluding to the manipulative Prospero’s ‘games’ on the island, but Zhu Shenghao preferred ‘carnivals’ (1954), highlighting the festive nature of the wedding celebration.

While textual variations and ambiguities can seem irrelevant to students, they are central to our understanding of a play and of our world. For example, is the opening division-of-the-kingdom scene in King Lear a psychological game to avoid ‘true’ love,Footnote 24 a contest of expressions of love, a political act or a classic case of a delusional ailing old father? Using open-access tools, such as Perusall.com, that incentivize and support the collaborative annotation of texts and video clips by opening up any PDF text or webpage for annotation, Alexa Alice Joubin establishes a social space where students learn from each other through the creation and circulation of free-form responses to cultural texts. In self-selected groups, some students explore historical meanings of ‘cannibal’, while others launch a comparative analysis of racialized representations of Caliban in Julie Taymor’s 2010 film and Greg Doran’s 2016 stage versions of The Tempest. There are multiple activation points for knowledge economies. Learning is rhizomatic and nonlinear in nature. As a result, students’ experiences in class are enriched by their differentiated, individualized and yet connected explorations.

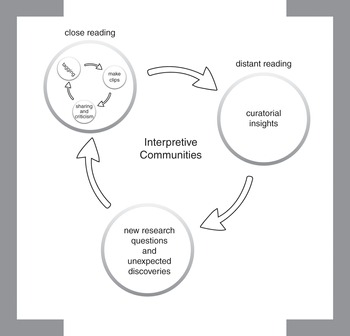

Perusall and similar computer-mediated scholarly communication platforms have been shown to enhance the quality of collaboration and promote effective learning interactions between students.Footnote 25 Annotations are gathered under thematic clusters as distinct ‘conversations’, as Perusall calls them, for analysis. For each assigned text, the class would read, annotate and comment on a shared document, engaging in close reading and a critical framework of literary interpretation (see Figure 1). The interactive nature makes reading a more engaging, communal experience, because readers become members of a community.

1 Close and distant reading.

Writing and circulating rationale for editorial and interpretive choices led to increased awareness of one’s own decision-making process, known as ‘meta-cognition’ in educational psychology.Footnote 26 With collaborative close reading, students claim the language, in recognition of the speech act, rather than just the character in the sense of whether a character is ‘relatable’. For instance, King Lear has opened up new avenues for linking contemporary cultural life and early modern conceptions of ageing. In one course, Alexa Alice Joubin’s students connected what they perceived to be Lear’s most eccentric moments (the division-of-the-kingdom scene and the first scene at Goneril’s castle) to the generational gap crystallized by the catchphrase ‘OK boomer’, which went viral after being used as a pejorative retort in 2019 by Chlöe Swarbrick, a member of the New Zealand Parliament, in response to heckling from another member. The goal of the class was not to determine whether Lear shares characteristics of entitled ‘boomers’ but, rather, to use fictional situations to launch cultural criticism with room for both intellectual and emotional responses to the play. The peer-to-peer collaboration excavates layered meanings of key words in a play text that tend to be glossed over by students if they read the text by themselves.

By creating knowledge collaboratively, students and educators lay claim to the ethics and ownership of that knowledge, an act that is particularly urgent and meaningful in the era of COVID-19, when students, more than ever, long to be connected to others, even under quarantine and in a remote learning environment.

Teaching Against AntiSemitism

The same principle of radical listening can be applied to teaching ‘one-issue’ plays, such as Othello (race) and The Merchant of Venice (antisemitism). Radical listening activates student engagement, while ensuring that, for example, the antisemitic rhetoric isn’t replicated by students in their discussions and assignments, and that Jewish students and faculty are cared for in the process.

Teaching Merchant can be a way to raise the awareness necessary to fight antisemitism. Students need to have some basic knowledge about antisemitism, including the Holocaust, to cope with this kind of hate and its current proliferation around the world, and Shakespeare can be one concrete case study for educating students about it. Holocaust awareness is disturbingly low, and Holocaust denial conspiracy theories currently abound. In a recent survey, the Claims Conference found that 63 per cent of adults under 40 in the United States had no idea that 6 million Jewish people were killed in the Holocaust. In a 2019 poll of eighteen European countries, the ADL (Anti-Defamation League) found that around ‘one in four Europeans polled harbor pernicious and pervasive attitudes toward Jews’;Footnote 27 and, overall, antisemitic hate crimes have increased. In 2019, antisemitic offences reached an unprecedented high number in the United States alone.Footnote 28 Given the frightening increase in hate crimes that are buttressed by widespread, global antisemitism that circulates continuously through various kinds of media, especially social media, and is supported by many right- and left-wing political figures, it is crucial that the play be taught from an informed and sensitive perspective, which a Levinas-based pedagogy can help us to navigate.

A Levinas-based approach to teaching Merchant emphasizes treating others with compassion, as it strengthens the students’ understanding of and active engagement with Shakespeare’s play and language. Through the exploration of The Merchant of Venice, we can provide students with the awareness necessary to become actively engaged in fighting the proliferation of misinformation, antisemitic rhetoric and propaganda, and working to end the violence in its name. This kind of social justice education is desperately needed, along with anti-racist teaching, in our classrooms. Significantly, this effort to teach the play with social justice as a goal furthers rather than lessens students’ intellectual engagement and learning. As Ayanna Thompson puts it, ‘while Shakespeare can be a secret weapon used to get to social justice issues, social justice lenses provide deeper, more sophisticated, and potentially more complex understandings of Shakespeare. Shakespeare needs social justice pedagogies as much as social justice pedagogies benefit from Shakespeare.’Footnote 29 Teaching with the goal of social justice strengthens, rather than weakens, students’ full engagement with Shakespeare’s texts, for, in Hillary Eklund and Wendy Beth Hyman’s words, ‘we can teach Shakespeare and Renaissance literature in ways that are vital to the pursuit of justice, while also doing literary texts themselves justice’.Footnote 30 Indeed, teaching with social justice as an aim motivates students to engage even more fully with Shakespeare’s texts, as well as various interpretations of them.

Although students’ attitudes vary greatly depending on region and other variables, it is safe to assume that they could benefit from an overview, even if it is a brief one, of the historical contexts of antisemitism, especially in light of the surveys noted above. This overview might consist of collected visual and written texts that introduce students to the medieval treatment of Jews and antisemitic tropes that set the stage for early modern representations like Shakespeare’s; modern antisemitism, pogroms and the Holocaust; the resurgence of antisemitic hate today. An overview of the historical background of antisemitism may be coupled with dramatic and theatrical history, such as the development of the Jew on stage, the Jewish moneylender and Jewish father/daughter plots, treatments of Shylock and Jessica on stage and in film. This background gives students the necessary tools to examine antisemitism in Shakespeare’s early modern text and provides contexts for assessing how and why later productions on stage and screen interpret the antisemitism in the play in the way they do.

Using a Levinas-based pedagogy, students not only examine the play in both early modern and contemporary contexts, learning to think about it and the issues it raises in new ways, but also think about how to respond to the suffering of the Other with compassion. A pedagogy based in Levinas’s ethics underscores the importance of recognizing the Other’s alterity while feeling compassion for their pain. For Levinas, the relationship between the self and other is asymmetrical, characterized by alterity, not sameness, which Levinas calls ‘non (in)difference’. In other words, the aim is not to fuse or become one with the Other – not to incorporate, consume, or colonize the Other – but rather to reach out to the Other while acknowledging, respecting and maintaining the Other’s difference.Footnote 31

Through this work on Merchant, students would learn that, although they feel grief for those who experienced the Holocaust, they should not assume that they can articulate or approximate victims’ suffering. The effort of substitution, the attempt to put oneself in the other’s shoes, must be mitigated with this awareness of alterity. This concept of non (in)difference may also be factored into analyses of performances on stage and screen, as well as in the students’ own performance activities and discussion in class.

Once students have a grounding in the historical and present-day contexts and have examined the play and select adaptations of it, they can engage in a creative activity that sharpens critical skills, increases an awareness of dramaturgy, and gives students a chance to apply what they have learned – to experience the power of Shakespeare adaptations to ‘talk back’ to hate.

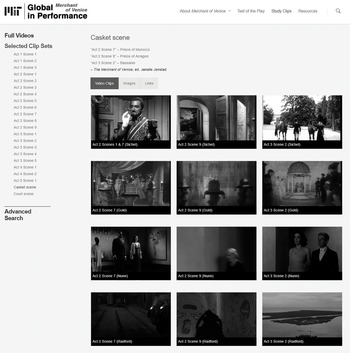

Hatred as a political tool and emotional response to difference emerges at the intersection of wilful ignorance and knowledgeable ignorance – the privileging of one singular ideology over others. The works of Shakespeare, as a canonical author, tend to inspire pursuits for singularity. One way to ‘talk back’ to hate is to engage with a large number of performance versions. We can raise students’ awareness of multiple performative interpretations of the same scenes in The Merchant of Venice and encourage students to offer their readings. Students have in their own hands the power to destabilize received interpretations and expand the repertoire of meanings. The outbreak of the global pandemic of COVID-19 in early 2020 closed live theatre events and cinemas worldwide, but the crisis has led to a proliferation of born-digital and digitized archival videos of Shakespeare in Western Europe, Canada, the UK and the US. In her teaching, Alexa Alice Joubin has used one of the self-contained online learning modules (shakespeareproject.mit.edu/explore) as part of the MIT Global Shakespeares (globalshakespeares.mit.edu), which she cofounded with Peter S. Donaldson. Vetted, crowd-sourced film clips with permalinks have been prearranged in clusters of pivotal scenes. While it is feasible to teach in-depth only one or two films of Merchant in a given class, instructors can expand students’ horizons by guiding them to close-read multiple, competing interpretations of a scene, comparing side by side the portrayals of Shylock in the court scene and of Portia in the casket scene in John Sichel’s 1973, Jack Gold’s 1980, Trevor Nunn’s 2001, and Michael Radford’s 2004 film versions in a module edited by Diana Henderson (see Figure 2). While the part cannot stand in for the whole, there are unique advantages to distracted concentration as an intellectual exercise.

2 Clusters of video clips of pivotal scenes in a learning module, led by Diana Henderson, of the MIT Global Shakespeares. Students can launch comparative analyses of contrasting performances of the same scenes in John Sichel’s 1973, Jack Gold’s 1980, Trevor Nunn’s 2001, and Michael Radford’s 2004 film versions of The Merchant of Venice; studyshax.mit.edu/merchantofvenice.

In an exercise designed by Lisa S. Starks, students consider how they would rewrite the play with a purpose, how they would adapt it to respond to and counter rising antisemitism today, keeping in mind Levinas’s notions of substitution and non (in)difference, as well as the importance of respect for each other during collaborative work. Similarly, Alexa Alice Joubin has encouraged students to work in teams to adapt the play to film, articulating their rationale for such important elements as casting, setting and costumes. Their rewrites must address, grapple with and seek to redress the antisemitism of the play for a contemporary audience. In groups, they would first discuss several questions concerning their adaptations, writing a narrative description of their story arc, aims of the production, role of characters, and so on. There are many options for students to choose, such as the following: what if Shylock does change his mind in the trial scene while he has the chance? Would he be treated fairly, anyway? What if Jessica decides to leave Lorenzo mid-play and return to her father’s home? What if Bassanio failed the casket test?

After completing this written portion of the exercise, students would then craft one full scene or trailer for their adaptation, which should include some language from the play as well as their own, submitting their scripts to the instructor for feedback and revision. Once all script revisions have been made, groups of students would perform their scenes – or, if the course is taught remotely, record their scenes to be posted online – accompanied by a cast ‘talk back’, in which students discuss their scene in light of the full adaptation that they mapped out. In a final reflection piece, students would discuss how and to what extent their adaptations fulfilled the goals of the assignment and what they learned in the process.

Teaching Against Transphobia

In addition to racialized discourses, gender is a key vector in literary and cultural criticism in a time of hate. In particular, we need to be informed about transgender studies and committed to countering transphobia and transmisogyny in our classrooms and communities. Whether we identify as trans ourselves or are trans allies, we can learn how to engage better and more sensitively with students, and model how they need to treat one another, how to respect individual gender identities on and off campus. The field of transgender studies enables us to see gender and its relationship to sex from positive, non-judgemental points of view, realizing that these differences are, indeed, authentic. It challenges the ways in which the medical field and some religious groups have condemned trans people, either by diagnosing them as pathological or declaring them to be sinful abominations of God’s laws. Transgender studies compels instructors and students to pose ethical questions concerning gender and the treatment of others, and to encourage political action to promote social justice and fight against violence perpetrated against trans communities.

Transphobia arises out of anger, fear and outrage that transgendered people disrupt gender norms and destabilize boundaries, and it often results in violent hate crimes. Sadly, this violence has been on the rise in recent years. In the United States under the Trump administration, for instance, there were disproportionately more hostile anti-transgender rhetoric, policy, social media attacks and negative media portrayals, and frequent sexual violence against, and murders of, transgender individuals, in particular transwomen of colour, evidencing the prevalence of transmisogyny, as well as transphobia, in our world today. The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) reports that at least forty transgender and gender-nonconforming people have been murdered in the year ending 9 December 2020. According to the HRC, these numbers surpass any years since it began compiling these figures in 2013.Footnote 32 In the United Kingdom, transphobic hate crimes have increased dramatically, quadrupling in the last five years and increasing in the last couple of years by 25 per cent. The BBC reports that many victims of these hate crimes do not feel supported by law enforcement and have nowhere to turn for assistance.Footnote 33 These are two among numerous examples globally that indicate the violent effects of transphobia and transmisogyny, and the dire need for activism to educate and fight for the rights and dignity of the trans community. Transfeminism is deeply committed to activism on these fronts.

Over the past decades, prominent films and theatre works have fostered new public conversations about gender politics in Shakespeare around the world. Shakespeare’s plays appeal to diverse audiences even though they were initially performed by all-male casts. Many modern adaptations on stage and on screen reimagine those plays as expressions of gender nonconformity. Stage Beauty (dir. Richard Eyre, Lions Gate Films, 2004) dramatizes the Restoration-era adult-boy actor Ned Kynaston’s trans feminine identities. Specializing in playing female roles such as Desdemona, Kynaston presents as female in his romantic life as well, until he is forced to play Othello. On stage, Drag King Richard III (dir. Roz Hopkinson, Edinburgh Fringe, 2004) told the story of a trans masculine character by repurposing Richard’s discourse of his deficiency, his status of being ‘deformed, unfinished … half made up’ (1.1.20–21). A film about theatre making, The King and the Clown (Wan-ui namja, dir. Lee Joon-ik, Eagle Pictures, 2005) chronicles the life of a trans woman in fifteenth-century Korea who shares a trajectory similar to that of Ophelia. Transgender Shakespeare reached a milestone in 2015 when the Transgender Shakespeare Company was founded in London, ‘the world’s first company run entirely by transgender artists’.Footnote 34 When actors embody a role, their own gendered bodies – with perceived or self-claimed identities – enrich the meanings of the performance.

Beyond explicitly trans-inclusive performances, Shakespeare’s plays lend themselves to analyses through a trans studies lens. Gender variance is more than just an early modern dramatic device or theatre practice. It is the core of some characters’ self-expression and trajectories. Our understanding of the comedies and romance plays would change dramatically if some characters are interpreted as transgender, such as Viola in Twelfth Night, Falstaff dressed up as the Witch of Brainford to escape Ford’s house in The Merry Wives of Windsor, Rosalind as Ganymede in As You Like It, and Imogen disguised as the boy Fidele in Cymbeline.

The classroom environment is an ideal place to begin this work against hate because transfeminism calls into question the transphobia and transmisogyny that, unfortunately, often surfaces in our institutions of higher learning in particular, as well as in our culture in general. Susan Stryker and Talia M. Bettcher have defined transfeminism – a term first coined in 1992 by US activists Diana Courvant and Emi Koyama, and further developed by Anne Enke in Perspectives in and Beyond Transgender and Gender Studies in 2013 – as a ‘“third wave” feminist sensibility that focuses on the personal empowerment of women and girls, embraced in an expansive way that includes trans women and girls’.Footnote 35 Transfeminism works to save and improve the lives of transwomen and to confront violence against trans communities around the world. Transfeminism intersects productively with critical race studies, disability studies and other social justice fields that fight antisemitism, xenophobia and other forms of hate and discrimination.

Employing a Levinas-based pedagogy and informed by transfeminism, we encourage students to acknowledge and respect the alterity of each other and the diversity of gender identifications. In an open, compassionate learning environment, students then can discuss the questions, insights and practices of trans studies. This approach can enrich the way we teach literature in general, and Shakespeare or early modern drama in particular. Students examine gender and other intersecting matters that have shaped how the plays have been performed and received in early modern, modern and contemporary contexts. For instance, work in early modern trans studies on the boy actor can help students to navigate the early modern territory. In studying Shakespearian performance and adaptation in modern and contemporary contexts, classroom readings and assignments might focus on trans issues to enable students to weigh in on decisions made by artistic directors, production companies, directors and actors, and to decide for themselves what effects these choices have on spectators, as well as their communities.

One exercise might focus on representations of trans people in both popular culture and Shakespearian performances on stage and screen. Television shows, films, documentaries and other media often foreground scenes or photos with news stories that feature trans individuals dressing and undressing, as well as rehearsing their walk, talk and gestures to appear as their ‘new’ gender, as if they are putting on an artificial gender with their costumes, accessories and mimed behaviour. Julia Serano points out that these scenes attempt to frame transgender people as if they simply portray a gender that they are not in reality. In this sense, media and pop culture portrayals ‘reinforce cissexual “realness” and transsexual “fakeness”’.Footnote 36 These kinds of scenes are standard in the productions and film adaptations of Shakespeare’s comedies, which include cross-dressed characters like Viola and Rosalind, whose trans experiences are often framed as liberatory, in contrast to those of male characters cross-dressed as women, such as Falstaff in Merry Wives of Windsor. Rather than liberatory, his – and other instances of transfeminine experience – are often rendered as shameful, typically the brunt of a joke for other characters within the play and sometimes also the audience outside of it, at least in productions in which scenes like Act 5, Scene 5 of Merry Wives are staged for laughs.Footnote 37 Representations of transwomen in contemporary media and popular culture also foreground these scenes of dressing/undressing, but they amplify them even more, so that transwomen appear as hyperfeminine and hypersexed, presented in images that exaggerate traditional female traits and characteristics to which the transwoman is seen to aspire, and often reduce the transwoman into fetishized body parts.Footnote 38

For the exercise, students would examine popular-culture examples of the representations described above, paired with comparable scenes from Shakespeare film or filmed stage productions. Showing popular-culture examples first can help students to enter into the discussion more freely and openly, without the stress of responding appropriately to the Shakespeare text. When they then view the Shakespeare examples, they can see that many of the same decisions, options and demands exist for these productions as for the others. After the viewings, students could then engage in an active discussion about both, making connections between them and their readings on trans theory and Shakespeare. Following this discussion, they could engage in an activity through which they apply what they have learned by creating their own version of a scene they viewed and compared, or another relevant scene. In this activity, students would have to decide what actors, set, staging or filming choices they would use and why. They would also need to consider how their choices would affect their entire imagined production, and how it would be received by audiences. Sawyer Kemp has argued that teaching Shakespeare’s cross-dressed characters as if they are examples of trans people is misguided because of the gaping disparity between the trans experiences of these characters and the lives of and challenges faced by actual trans people in our contemporary moment. To counter this problem, Kemp advocates pairing these texts with readings by and about trans people and assigning students questions that help students to navigate the terrain of these differences; or teaching a character like Hamlet, rather than a cross-dressed one, as exhibiting trans elements.Footnote 39 Our exercise offers yet another option. Although it does focus on Shakespeare’s cross-dressing characters, it requires that students examine how these characters are represented as characters, with an eye towards how that representation – as well as those in film, television and other media – shapes cultural perceptions and attitudes towards trans people.

This exercise may be modified for whatever delivery mode is used – face-to-face or online. With a face-to-face format, students could work in small groups and determine collaboratively how they would stage the scene, and then perform it for the class; with an online format, students could write an outline and/or make a short video that summarizes and demonstrates how they would do the scene, and how that scene would fit in the larger imagined production. Whether face-to-face or online, students would be engaged in the decision-making process of production, so they would need to deliberate and consider how their productions might affect spectators and surrounding communities. And, by using a Levinas-based pedagogy, informed by trans theory, we can continue to focus not just on what material is read or digested, but how students learn actively through a compassionate awareness of others within the class and those beyond, improving the lives of trans individuals inside and outside of academe.

Conclusion: Reparative Pedagogy

The silver lining of teaching in a time of hate is that the social justice turn in the arts has rekindled reparative interpretations of the classics. Since 2009, the Social Justice Film Institute in Seattle has supported activist filmmakers through its Social Justice Film Festivals. The Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen Center for Thought and Culture in New York has sponsored the Justice Film Festivals since 2015 to ‘inspire justice seekers by presenting films of unexpected courage and redemption’.Footnote 40 Marin Shakespeare Company in San Rafael, California, offers drama therapy and ‘Shakespeare for social justice’ programmes for inmates and at-risk youths. The group use Shakespeare to ‘practice being human together’, because Shakespeare offers ‘deep thinking about the human condition’.Footnote 41

There is a long tradition of using literature as coping strategy.Footnote 42 Works such as Malcolm X (dir. Spike Lee, 1992) have played key roles in American civil rights movements and current struggles for racial equality, and Tony Kushner’s play Angels in America has been an iconic text in the gay movement. Likewise, adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Little Mermaid’ are a constant point of reference among young trans girls in mainstream media. Renowned for their all-female productions, London’s Donmar Warehouse (led by Phyllida Lloyd) aims to ‘create a more … functional … society [and] inspir[e] empathy’, because they ‘believe that representation matters; diversity of identity, of perspective, of lived experience enriches our work and our lives’. Literature gives language to victims of psychological trauma who lose speech. The popularity of reparative readings of literature lies in the duality of a simultaneously distant and personal relationship to the words.Footnote 43

In closing, we would like to note that diversity in higher education is distinct from advocacy journalism, which means we have to work actively against any ineffectual default to political correctness. When implemented unilaterally as a one-size-fits-all imposition, some gestures of inclusion risk becoming empty rituals. For example, having students self-identify their personal pronouns can be counterproductive; some feel uncomfortable with public confessions, while others may change their pronouns depending on context or over time. Education is only reparative when it is designed from the ground up to be truly inclusive, rather than being a mindless replica of evolving political correctness. Independent facility with complex cultural texts enables everyone to pierce the dense, euphemistic cloud of diversity categories that tokenize individuals and fictional characters based on any given identity marker.

We propose that we employ literature for socially reparative purposes to reclaim Shakespeare from ideologies associated with colonial and patriarchal practices. As these narratives connect students to other racialized communities, times and places, the students engage with multiple, sometimes conflicting, versions of the same story. Our Levinas-inspired, intersectional pedagogy serves well a diverse student body with different learning needs.