The Cold War divided the world into two implacable blocs and made the situation in Vietnam after 1954 a major expression of that implacability. Recognizing that fact, leaders of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) in Hanoi convinced themselves that success in their revolution could tip the worldwide balance of power in favor of the socialist bloc and national liberation movements throughout the decolonizing world. This conviction, combined with the fact that they had to conduct their struggle for national liberation and reunification from a position of relative military weakness, made those leaders accomplished practitioners of international politics. So, too, did the totality of their commitment to Marxism-Leninism and thus to anti-imperialism and anti-Americanism.

This chapter addresses Vietnamese communist internationalism in the period from 1954 to 1975. It considers Hanoi’s self-appointed mission to advance the causes of socialism, national liberation, and anti-imperialism worldwide as it struggled to reunify Vietnam under its aegis. It demonstrates that even at the height of the war against the United States, DRV leaders never thought strictly in terms of the national interest. Obsessed as they were with the liberation and reunification of their country, they were also committed to the wider causes of socialism, “world revolution,” and “tiers-mondisme” (Third Worldism). While Hanoi did not share the commitment to non-alignment that sometimes animated Third Worldism, it applauded and encouraged calls for unity among decolonized and decolonizing states, for both ideological and practical reasons (Figure 4.1). During the second half of the 1950s, it endorsed the peaceful “spirit of Bandung” promoted by the first generation of Third World states and leaders. The following decade, it fervently supported the second generation of states and leaders embracing a more radical, even militant, revolutionary vision inspired by the triumph of the Cuban and Algerian revolutions and the overseas travails of Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

Figure 4.1 A secondary theme of OSPAAAL imagery was the political value of solidarity. Rising identification with North Vietnam and revolutionary movements went hand in hand with hostility to US interventions in the Global South. OSPAAAL, Olivio Martinez, 1972. Offset, 54x33 cm.

To be sure, the Cold War, to say nothing of the Sino-Soviet dispute, created myriad challenges for Hanoi. But the contemporaneous process of decolonization in the Third World also created opportunities it sought to exploit to enhance its legitimacy and elevate its image worldwide, meet its core goals in Vietnam, and advance its vision of human progress.

The DRV and the International Community, 1954–63

Vietnamese communist leaders learned to appreciate the merits of actively engaging the international community during their war against France – the Indochina War (1946–54). During the Party’s Second Congress of February 1951, held after a crushing defeat suffered by Vietminh forces at Vinh Yen outside Hanoi, the leadership stressed the imperative to sustain the war against France until complete victory. To meet that end in light of the difficult situation confronting their forces, Party leaders mandated better mass organization and mobilization efforts at home, on the one hand, and resort to “people’s diplomacy” (ngoai giao nhan dan) – namely, exploitation and manipulation of anti-war and anti-colonial/imperialist sentiments – abroad, on the other. The DRV would henceforth endeavor to “maintain friendly relations with any government that respects the sovereignty of Vietnam” and “establish diplomatic relations with countries on the principle of freedom, equality and mutual benefit.”Footnote 1

Starting that year, the international community figured prominently in the strategic calculations of the leadership. The so-called diplomacy struggle became a cornerstone of the ideology and national liberation strategy espoused by Ho Chi Minh and the rest of the Party leadership. “International unity and cooperation are necessary conditions for the triumph of the national liberation revolution,” they surmised, contributing as it did to “development of the new regime, the socialist regime.”Footnote 2 In order to serve the goals of that struggle, Ho and the leadership publicly downplayed their embrace of Marxism-Leninism and links to Beijing and Moscow, professing instead a commitment to nationalism and patriotism, and to national liberation across the Third World. The approach was self-serving, to be sure. At the same time, there was a clear affinity between the struggle led by Vietnam’s communist party and that waged by revolutionary nationalist leaders across the colonial and semi-colonial world. Most obviously, both struggles accentuated anti-imperialism.

In July 1954, the DRV government entered into the Geneva accords with France. The accords provided for a ceasefire; the regrouping of Vietminh forces above the seventeenth parallel and of forces loyal to France below that demarcation line; the free movement of civilians between the two zones for a period of 300 days; the return of prisoners of war; guarantees against the introduction of new foreign forces in Vietnam; and a plebiscite on national reunification within two years. Until then, the northern zone would be under the authority of the DRV regime and the southern zone under the jurisdiction of France and its local clients.

Ho Chi Minh and the Party leadership accepted the Geneva accords because they thought they were the best they could get under the circumstances and that they might be workable. That is, they believed the accords would not only end the eight-year-long Indochina War but also might bring about the peaceful reunification of Vietnam under their governance. The accords were far from perfect. Their terms, Ho and other leaders felt, could have been more generous. Still, they were satisfied because at a minimum the accords guaranteed that the United States would not intervene militarily in Indochina – in the near future, at least. Earlier that year, the Party, now called the Vietnamese Workers’s Party (VWP), had decreed that the United States constituted the “foremost enemy” of the Vietnamese revolution. By its rationale, the French would never have managed to sustain their war in Indochina for as long as they did without American backing. Washington had enabled Paris since 1950, in the wake of the recognition of the DRV by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the rest of the socialist camp. American “imperialists” had not only supported French “colonialists” materially and politically from that moment onward but in fact manipulated Paris into staying the course in a war that served Washington’s interests more than France’s own. The Americans had essentially used the French as proxies to neutralize the Vietnamese revolution and contain the national liberation cause in Southeast Asia because it threatened their own designs and ambitions in the region.

When Paris decided to negotiate the terms of its extrication from Indochina with DRV representatives in Geneva beginning in May 1954, just as the Battle of Dien Bien Phu ended, Washington turned to a new proxy, as Hanoi saw it, to do American bidding: Ngo Dinh Diem. Thanks to US patronage, in June 1954 Diem became prime minister of the State of Vietnam, the “puppet” state set up by the French under Emperor Bao Dai in 1949 to enhance the legitimacy of their struggle against the DRV-led Vietminh. Though his authority was initially tenuous at best, Diem – a staunch anti-communist with respectable nationalist credentials – became in time a major impediment to the realization of communist objectives in Indochina.

No sooner had it signed the Geneva accords with France than Ho’s government recognized the difficulties it would face in trying to implement them. While Paris seemed prepared to honor their terms, Washington, and Diem in particular, would not even endorse the Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference confirming the accords’ legitimacy. With acquiescence in the Geneva formula from neither Washington nor Saigon, the chances that Vietnam would ever be peacefully reunified under communist governance were slim.

To improve its prospects in the face of a highly problematic situation, Ho’s government turned to diplomacy, as it had in 1951 to offset the consequences of the Vietminh defeat at Vinh Yen. It mounted a major propaganda campaign emphasizing the merits of its cause, the legitimacy of the DRV, as well as its commitment to the peaceful reunification of Vietnam, and denouncing the “crimes” and nefarious intentions of Washington and its local “reactionary” allies. The central purpose of this exercise in people’s diplomacy was to draw international attention to the situation in Vietnam and, most critically, prompt other governments and influential organizations to see circumstances there as Ho’s regime saw them. Winning over world opinion – gaining wider public sympathy – would not only help muster political and moral support for the DRV’s cause; it would also make it more difficult for Washington and Saigon to violate the letter and spirit of the Geneva accords. That is, diplomatic isolation would make the revolution’s enemies hesitate to further subvert peace in Indochina. At a minimum, it would make Washington think twice before intervening militarily, a prospect Ho himself feared to the extreme and hoped to preclude at all costs. Favorable, supportive world opinion would serve as a hedge against US intervention and improve DRV prospects for success in the new context. Ho’s government effectively used diplomacy to advance its own interests at the expense of its enemies.

To meet the ends of this latest diplomatic campaign, DRV leaders and pertinent organs attuned themselves to international affairs and made concerted efforts to engage other governments, particularly nationalist regimes in the Third World and “progressive” movements and organizations in the First. Consistent with the decree endorsed during the 1951 Party Congress, they legitimated their state’s existence above the seventeenth parallel after July 1954 by seeking formal diplomatic recognition from other governments and promptly recognizing newly independent countries when suitable. As previously noted, in 1950 the DRV had obtained recognition from the PRC, the Soviet Union, Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Albania, Romania, and North Korea. In 1954, Mongolia followed suit. That same year India, a vanguard of the Non-Aligned Movement, became the first noncommunist country to open a diplomatic mission in North Vietnam, and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited the DRV in October. France, the United Kingdom, and Canada each had diplomatic representation in the North by then, but largely to meet their various obligations under the terms of the Geneva accords.Footnote 3

A socialist state and avowed member of that camp after 1954, the DRV publicly downplayed its ties to communism and sought to insinuate itself into other circles to gain wider legitimacy and support for its agenda. To the same end, it tried to keep under wraps the transformation of the North Vietnamese economy and society along socialist lines, in full swing at the time. Instead, it leveraged its status as a semi-colonial state and victim of French and now American imperialism to gain political and moral support from revolutionary leaders, movements, and government across the Third World, otherwise wary of strict communism with its emphasis on class struggle at the expense of national unity. To such strategic aims, labor, student, and women’s unions from the DRV regularly participated in international conventions. Those forums provided “an indispensable format for enabling successful diplomacy” while providing opportunities to network with other states and affirm DRV sovereignty.Footnote 4 Representatives from the DRV attended meetings of the World Peace Council (WPC), Moscow’s answer to what Soviet leaders perceived was a United Nations Organization stacked against them. Formed in 1950, the WPC acquired a measure of international legitimacy over time through its promotion of peaceful coexistence, sovereignty, nuclear disarmament, and decolonization. Unlike the United Nations, its members were not states but progressive individuals and action groups, including associations and unions representing women, students, writers, journalists, and scientists. Jean-Paul Sartre participated in the WPC’s congress of 1952. Other notable individuals who attended WPC-sponsored meetings or otherwise supported its activities included Pablo Picasso, W. E. B. DuBois, Paul Robeson, Louis Aragon, Diego Rivera, and Pablo Neruda.Footnote 5 That made the WPC an ideal target for the DRV’s people’s diplomacy.

In 1955, Ho’s government participated in the Asian-African Conference in Bandung. This international conference offered DRV representatives a unique opportunity to meet, discuss, and fraternize with leaders and diplomats from dozens of countries outside the socialist camp sharing experiences of colonialism and embracing, to varying degrees, independent Third World nationalism. Bandung facilitated the forging of ties with other Third World governments, culminating in the exchange of diplomatic missions, among other undertakings. Indonesia, the host country, established formal diplomatic relations with the DRV immediately after the conference. Burma opened a diplomatic mission in Hanoi, as had India, as previously noted. Essentially, Bandung allowed the DRV to build networks with other Third World governments while affirming its legitimacy and Vietnam’s sovereignty. Beyond that, the conference, spurred in large part by mounting Cold War tensions in Southeast Asia and in Indochina specifically, provided a stage for mustering political and moral support for Hanoi’s national liberation and reunification struggle. For years thereafter, that is, until Vietnamese communist leaders shifted to a more militant approach to address the situation in South Vietnam, Hanoi promoted and extolled the virtues of the “Bandung Spirit” because it served the goals of its diplomatic struggle and remained consistent with its own domestic imperatives.

Bandung played a seminal role in bringing about the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO), created in Cairo in 1957; the Non-Aligned Movement, formally established in Belgrade in 1961; and the Afro-Asian Latin American People’s Solidarity Organization, formed in Havana in 1966. Individually and collectively, these organizations promoted “a political consciousness against Western norms and power” that persisted and grew as more countries in Asia and Africa secured independence.Footnote 6 As increasing numbers of Third World states joined the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement in particular came to “have a great voice on the world stage, making great changes on the international chessboard, becoming a force that both socialist and imperialist countries wished to fight for,” according to a semi-official Vietnamese account.Footnote 7 The DRV’s involvement in that and other such movements supported the aims of its public diplomacy as well as its efforts to shame the United States into curbing its interference in Vietnamese affairs. It also suggested that the DRV regime was more nationalist than it was communist, beholden more to the Third World than to Moscow or Beijing. Hanoi’s Third World activism enhanced its image across the noncommunist world and invested the Party with a degree of autonomy without alienating its socialist allies.

DRV authorities, ensconced in Hanoi after completion of the French withdrawal from the city in October 1954, gradually became loud and recognizable voices advocating on behalf of “oppressed” masses everywhere. At first, the latter meant those suffering under the yoke of colonialism and neo-imperialism in the Third World. In time, it also included victims of capitalist greed generally defined, including the poor and marginalized communities in the First World. Audiences worldwide were receptive to the authorities’ message. The Indochina War, and especially the DRV victory at Dien Bien Phu, had sounded the death knell for France’s overseas empire. Events in Vietnam galvanized revolutionaries in Algeria and across the rest of the Third World including, in time, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America.Footnote 8 Thus, the more the DRV publicized others’ causes and developed ties to them, the more those others felt sympathy for its efforts to complete the “liberation” of Vietnam. The DRV’s backing of Algerian independence, sub-Saharan African decolonization, and the African National Congress (ANC)’s anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa were especially important in that respect.Footnote 9 Identifying with national liberation movements solidified the bond between the DRV and other Third World governments supportive of causes championing self-determination and anti-imperialism.Footnote 10

Hanoi’s diplomacy facilitated manipulation of public perceptions of its purposes and policies and enabled communist policymakers to cultivate a favorable, broad-based, global political awareness and understanding of their aspirations. In 1958, VWP theoretician Truong Chinh elaborated on the DRV’s international obligations even as it endeavored to build socialism above the seventeenth parallel and bring about “liberation” in the South. Hanoi, he observed, must oppose “all war kindling schemes of the imperialist aggressors and their agents,” strengthen “friendly solidarity and the fraternal cooperation with the USSR, China, and [other] people’s democracies,” and “support national liberation movements in the world” and the ongoing one in Algeria in particular.Footnote 11 A year later, the VWP Central Committee noted that “the problem of achieving the unification of our country, the achievement of independence and democracy in all of our country” was not only “the problem of the struggle between our nation against the American imperialists and their puppets,” but also “the problem of the struggle” between the progressive camp and the imperialist camp. The “victory of the Vietnamese Revolution,” the Committee concluded, would have “an enthusiastic effect” not only on the rest of the communist world but also “on the movement of popular liberation in Asia, Africa, [and] Latin America” to the point of precipitating “the disintegration of colonialism throughout the world.” Fundamentally, the Vietnamese revolution was “part of the world revolution.”Footnote 12 The triumph of the Cuban revolution in January that same year marked, in the eyes of Vietnamese communist leaders, “the expansion of the scope of socialism on three continents” as well as a major defeat for imperialism and solidified their commitment to internationalism.Footnote 13

Through 1959 and the early 1960s, the DRV quietly asserted itself as a member of the socialist camp as it expanded its ties to the non-aligned and national liberation movements. Following the onset of the Sino-Soviet dispute in the late 1950s, Hanoi played a leading role in the effort to reconcile the two communist giants. Though that effort failed to end the dispute, the Vietnamese gained a great deal of respect from both Moscow and Beijing as well as from the rest of the socialist camp for attempting to mitigate the dispute despite being one of that camp’s youngest – and smallest – members and embroiled at the time in a serious conflict of its own. All the while, the DRV sustained its engagement with the Third World, effectively seeking to define itself as a postcolonial state, aggressively advocating for the end of colonial rule in Africa and promptly recognizing states on that continent after they gained independence. It established diplomatic relations with Guinea (1958), Mali (1960), Morocco (1961), the Democratic Republic of Congo (1961), Egypt (1963), the Republic of Congo (1964), Tanzania (1965), Mauritania (1965), and Ghana (1965). The DRV was among the first governments to recognize the new Algerian state in 1962, a logical move considering Hanoi had extended material, political, and moral support to revolutionaries there during their war against France.Footnote 14 “Despite the fact that the country was divided and invaded by the United States,” historian Vu Duong Ninh has written, “Vietnam remained trusted by many countries in the struggle against colonialism and imperialism,” and could thus “contribute significantly to national liberation movements across the world.”Footnote 15 As an act of policy, each year on the day marking the anniversary of the independence of a Third World country, Ho Chi Minh sent the head of that state a telegram wishing continued peace and prosperity on behalf of “the people of Vietnam and the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.” The gesture was effortless, to be sure, but did not go unnoticed and unappreciated by the recipients of those telegrams.Footnote 16

This tendency to associate with and engage international and transnational movements became a hallmark of DRV diplomacy and a defining aspect of its revolutionary strategy and ideology. In May 1963, for example, a meeting of African states in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa concluded with the formation of the Organization of African Unity, joined by thirty-two governments. According to an editorial in Nhan dan, the VWP mouthpiece, the conference “highlighted the humiliating defeat of and the end of the road for colonialism,” on the one hand, and “the great victory of the national liberation revolution,” on the other. “Our southern [Vietnamese] compatriots involved in a difficult and heroic struggle against the US- Diem clique are very excited about the outcome of this conference, and see the success of the African people as their own success,” the editorial concluded.Footnote 17 There was a logic to such support. Pan-Africanism, Pan-Asianism, and communist internationalism, among other movements, shared a common ideological aversion to neo-imperialism and Western capitalism. Each also sought to empower historically marginalized constituencies, to give a voice to the voiceless, and to emancipate the oppressed. More practically, these movements allowed states such as the DRV to “place their political aspirations in identity-based communities that extended beyond the formal boundaries of nation-states,” historian Christopher Lee has noted. That achievement facilitated the pursuit of their most fundamental political goals. “Frequently guided by an ambitious intellectual leadership,” Lee writes, “these transnational endeavors sought to collect and stand for the hopes of broadly defined social groups that faced political restrictions locally and globally.”Footnote 18

Vietnamese Communist Internationalism, 1964–75

Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, Hanoi regularly asserted publicly its commitment to the “world revolutionary process”; however, its words were slow to translate into direct action. It provided troop and material support to the nascent insurgency in South Vietnam but in cautious, deniable ways. Ho was adamant about avoiding the resumption of “big war” in Indochina and thus giving Washington no pretext to intervene militarily in Vietnam. During this early period, the DRV leadership felt it was best to wait on events in the South and focus on building the socialist economy in the North.

That all changed in 1963–64. Convinced by the domestic and international situation that imperialism and capitalism were on the defensive worldwide, increasing numbers of VWP members, including members of the Politburo, demanded that Hanoi seize this “opportune moment” and adopt a more “forward” strategy in the South. If the DRV was ever to become a “vanguard” for national liberation movements across the Third World, these galvanized Party members believed, then it had to get over its fear of provoking US intervention and act decisively in the South.

That attitude was both cause and consequence of the growing influence in Hanoi of a hard-line, radical clique obsessed with moving to direct action to confront imperialism and reactionary capitalism in Indochina. Emboldened by circumstances, members of that clique proceeded to seize the reins of power from Ho and other moderates in a bloodless palace coup during the Ninth Plenum of the VWP Central Committee of December 1963. Whereas Ho and his associates had conducted their foreign policy largely based on pragmatic considerations, seeking to avoid confrontation with the United States, the men who controlled decision-making in the aftermath of the Plenum were committed ideologues with strong internationalist proclivities who were hell-bent on leaving their mark on the world. The interests of the wider socialist world and of “oppressed masses” in the rest of Asia, Africa, and Latin America were as important to them as the liberation and reunification of their own nation.Footnote 19

Le Duan, the brains behind the coup who replaced Ho as paramount leader, personified this new consensus. From the moment Ho acquiesced in the Geneva accords, Le Duan maintained that was a mistake, that Saigon and especially Washington would never honor the terms of those accords, and that only war could solve the Party’s predicaments in Indochina. Vindicated by circumstances, Le Duan would shape DRV foreign policy on the basis of rigid ideological considerations starting in 1964. As he and his chief lieutenants were fond of Chinese revolutionary prescriptions, they became strong proponents of revolutionary militancy in South Vietnam for the sake of socialist solidarity and in the name of proletarian internationalism. Those lieutenants included VWP Organization Committee head Le Duc Tho, PAVN General Nguyen Chi Thanh, and DRV Deputy Prime Minister Pham Hung. All were members of the Politburo. As southern veterans of the Indochina War and hardened revolutionaries, they firmly believed in the merits of Marxism-Leninism – its Maoist Chinese variant to be specific – as a blueprint for revolutionary success. Inspired by the Russian, Chinese, and Cuban examples, they sought nothing less than total victory over their enemies to augur a new era in their nation’s – and the world’s – history.Footnote 20

For Hanoi’s new sheriffs, the Vietnamese revolution constituted more than a component in a global movement opposing the United States and capitalist imperialism: it was a potential model for all others similarly engaged in national liberation struggles, much as their allies in Moscow, Beijing, and Havana were for them. The VWP, according to Le Duc Tho, was a “vanguard unit of the working class and capable of leading the revolution throughout the country to complete victory, thereby making worthwhile contributions to the revolutionary cause of the working class and the laboring people throughout the world.”Footnote 21 Tho, like Le Duan, believed that defeating the Americans and their lackeys was necessary not only to achieve Vietnamese liberation and reunification, but also to protect and advance the cause of all “peace-loving” peoples. Hanoi’s war against the United States and its reactionary allies in Saigon was “a part of the world revolution,” waged in “the cause of revolutionary forces worldwide.”Footnote 22 Under Le Duan’s regime, the diplomatic campaign initiated in 1954 to enlist foreign support for the DRV and the Vietnamese revolution developed into an ideologically driven mission to spearhead the struggle against imperialism and reactionary tendencies across the globe.

Though they remained devoted Marxist-Leninists at heart, Le Duan and his chief lieutenants publicly proffered their commitment to nationalism and anti-imperialism because it suited their purposes, especially as they concerned the DRV’s diplomatic endeavors. Relative to the previous regime under Ho, Le Duan’s was significantly more dogmatic and doctrinaire. Unlike Ho, whose hard-line comrades within the Party always questioned his commitment to Marxism-Leninism and deemed him too much of a nationalist, Le Duan’s communist and internationalist credentials were impeccable.Footnote 23 That is, whereas Ho had had a nasty habit of prioritizing national unity over class struggle, Le Duan always knew to subsume the former under the latter. Here was a true believer in the infallibility of communism and the purposive nature of History. Here was also an individual who considered nationalism a mere tool, a means, to the achievement of national liberation under the Party’s own brand of governance, and not an actual motive force of or genuine raison d’être for the Vietnamese revolution.

The onset of the American War in spring 1965 solidified the resolve of Le Duan and other DRV leaders to make their revolution a vanguard for Third World liberation movements. As their country became a crucible and violent expression of the global Cold War, the Vietnamese revolution gained widespread notoriety. According to political scientist Tuong Vu, DRV leaders embraced their situation because it “vindicated their beliefs about the fundamental cleavage in international politics between capitalism and communism, between revolutionaries and counterrevolutionaries.” Beyond that, it “allowed them to proudly display their revolutionary credentials” as well as to work on “realizing their radical ambitions.”Footnote 24 As an expression of the Cold War, the American War was welcomed by radical leaders of the Vietnamese communist movement and Le Duan in particular. By one account, following the onset of the American War, Le Duan became “intoxicated” with the prospect of “winning everything” on every front.Footnote 25

DRV leaders marketed their “anti-American resistance” as a “just struggle” and manifestation of the global fight against imperialism for “peace and justice.” On one side of the struggle, as Le Duan put it in a characteristic formulation, was “the most stubborn aggressive imperialism with the most powerful economic and military potential”; on the other were “the forces of national independence, democracy and socialism of which the Vietnamese people are the shock force in the region.”Footnote 26 Sustaining the fight against the United States was the “moral obligation” of the Vietnamese on behalf of the national liberation movement and of oppressed masses everywhere, Hanoi stressed in both its domestic and foreign propaganda. Bringing about Vietnamese reunification under communist aegis was, for its part, the DRV’s and the VWP’s duty on behalf of “the international Communist movement” and in “the spirit of proletarian internationalism.”Footnote 27

Devout Marxist-Leninists as they were, Le Duan and other Vietnamese communist leaders cleverly downplayed ideology and their communist credentials in propaganda and other forms of engagement targeting nonsocialist states. Their travails against the United States and its southern “puppets” were, they affirmed, purely nationalist endeavors. The Vietnamese were heirs to a long, glorious, and heroic tradition of resistance to foreign aggression, their propaganda claimed, and the fight against the United States was but a continuation of that tradition.Footnote 28 The Vietnamese resistance maintained close ties with the Soviet Union and China, Hanoi acknowledged, but that was only because circumstances warranted such ties. Everyone engaged in the struggle against American “imperialists,” from top decision maker to common foot soldier, was a nationalist at heart whose sole aspiration was to live to see the day when the nation was fully “liberated” from the clutches of foreign “invaders” and their “reactionary,” treacherous local clients. All else was inconsequential.

In repeating that line and marketing their war against the United States on such terms, Le Duan’s regime sought not only to win over world opinion but also to encourage other “oppressed masses” to take up arms and fight, to demonstrate that seemingly minor actors could play important roles in the Cold War and contribute to the world revolution and the demise of imperialism. Its conscious effort to inspire others to fight imperialism even as it attempted to rally them in support of its cause bore dividends. Its “determined stance in the face of American technological might,” historian Michael Latham has written, “became an appealing symbol of determined resistance and the power of popular revolutionary war.”Footnote 29

Following American intervention, Hanoi developed intimate ties with numerous foreign governments and movements, in the socialist world and beyond, which provided much-needed political, moral, and material support. China, the Soviet Union, and other communist states supplied indispensable military hardware and other aid. Limited in their ability to provide such assistance, Third World governments aided Hanoi by heralding its troops and southern insurgents belonging to the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong, in Western parlance) as heroes fighting for the cause of national liberation worldwide. Such rhetorical and moral support proved instrumental in publicizing the “just struggle” of the Vietnamese and increasing the pressure on American policymakers to desist in Indochina. Even as the United States subjected the North to sustained bombings, foreign delegations – including many from the United States – visited the DRV and, while there or upon their return home, publicly expressed their support and admiration for the resistance of the “brave” Vietnamese. They also widely and openly condemned the American military intervention and the bombing of “innocent civilians” in the North, fueling anti-war sentiment across the world and in the United States.Footnote 30

The importance of Vietnam to this global revolutionary movement was impossible to miss in January 1966, when Fidel Castro hosted the Tricontinental Conference in Havana to promote national liberation and communism in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Some 600 participants representing more than eighty sovereign governments, national liberation movements, and other organizations attended the thirteen-day event, but Vietnam and its struggle against American militarism occupied a prominent place in deliberations. In a stirring “message to the Tricontinental,” Che Guevara, an architect of the Cuban revolution and world’s most famous itinerant revolutionary, noted that “every people that liberates itself is a step in the battle for the liberation of one’s own people.” Vietnam, he said, “teaches us this with its permanent lesson in heroism, its tragic daily lesson of struggle and death in order to gain the final victory.” In that country, “the soldiers of imperialism encounter the discomforts of those who, accustomed to the standard of living that the United States boasts, have to confront a hostile land; the insecurity of those who cannot move without feeling that they are stepping on enemy territory; death for those who go outside of fortified compounds; the permanent hostility of the entire population.” “How close and bright would the future appear,” Che famously concluded, “if two, three, many Vietnams flowered on the face of the globe, with their quota of death and their immense tragedies, with their daily heroism, with their repeated blows against imperialism, forcing it to disperse its forces under the lash of the growing hatred of the peoples of the world!”Footnote 31

The meeting in Havana spawned the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (commonly known by its Spanish acronym OSPAAAL), which staunchly supported Hanoi and the NLF’s anti-American war. Che’s message, published a year later under the title “Create Two, Three … Many Vietnams, That Is the Watchword,” became a rallying cry for revolutionary organizations and movements all around the world, increasing Vietnam’s international profile and the notoriety of its anti-American resistance. Even French President Charles de Gaulle jumped on that bandwagon through a much-publicized speech in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, in September 1966. Attempting to curry favor with former French colonies largely sympathetic to Hanoi, he condemned US military intervention in Southeast Asia and called for Washington to end the war at once. In doing so, de Gaulle also reaffirmed his intent to distance his government from the United States, a desire most blatantly expressed through his decision to dramatically curtail French involvement in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) earlier that year.Footnote 32

Through propaganda and manipulation of foreign journalists, dignitaries, and other personalities, the DRV molded world opinion to suit the interests of its armed struggle. Thanks to Hanoi’s own fastidiousness and to the loud voices of its allies and friends, media outlets from across the world closely followed the situation in Vietnam, paying particular attention to the activities and behavior of American forces. The International War Crimes Tribunal, also known as the Russell Tribunal after its founder – the philosopher and delegate to the Tricontinental Conference, Bertrand Russell – proved meaningful in that respect. Its ideologically motivated investigation into the nature of the American war in Indochina found the United States guilty of genocide against the region’s peoples. For good measure, Hanoi created a special government agency, the American War Crimes Investigative Commission, tasked with compiling numbers and producing detailed, though quite exaggerated, reports on “illegal,” “immoral,” and “criminal” American activities in Vietnam. As developments in Vietnam or related to the war there regularly made front-page news everywhere, audiences around the world became captivated by the conflict. DRV authorities made sure those reports found their way into the hands of anti-war activists and leaders, including members of the Russell Tribunal.

This ostensible globalization of the Vietnamese revolution dramatically increased Hanoi’s stakes in the Vietnam War. Just as success stood to rouse others struggling against reactionary enemies, defeat might spell the doom of the world revolution and deject national liberation fighters across the Third World. But Le Duan and his chief lieutenants would not be deterred. That is, the small size of their country, its low level of economic development, and the daunting political challenges it faced did not preclude them from accomplishing remarkable feats and meeting their obligations to the international community. Egypt, Yugoslavia, Albania, Algeria, and, most notably, Cuba had each demonstrated that small states were capable of impacting the world, influencing the international system, and transcending or otherwise challenging Cold War bipolarity.Footnote 33

Hanoi’s stubborn refusal to abandon its goals following the onset of the American War, its resilience, and even the mere fact that it and the NLF were not losing badly challenged conventional thinking on American military might and the merits of guerrilla warfare. Despite their technological superiority and abundant wealth, the Americans were incapable of defeating Vietnam’s “peasant armies” and halting their march to independence. The Vietminh and Algeria’s own NLF deserved praise and respect for defeating the French in their respective anti-colonial struggles after World War II; but Hanoi’s willingness to take on the United States in the Vietnam War and its successes were nothing short of remarkable.

Le Duan sought to deal the United States a coup de grâce with the Tet Offensive of January 1968. Consisting of surprise, concerted attacks on all major southern cities and towns, the campaign aimed to precipitate a general uprising of the southern masses demanding the withdrawal of American forces and abdication of the regime in Saigon. Le Duan had long hoped for such an uprising in the South, which he thought would leave Washington no choice but to abandon Vietnam unconditionally.Footnote 34 As it turned out, internationalist concerns also figured prominently in his calculations. Le Duan confided in his Chinese counterparts that his regime accepted the possibility of “enormous bloodletting” to achieve total victory over the Saigon regime and the Americans because that would not only contain American neo-imperialism in Indochina but inspire other peoples in Asia, Africa, and Latin America to free themselves from the oppression induced by Western capitalism.Footnote 35 “We have to establish a world front that will be built first by some core countries and later enlarged to include African and Latin American countries,” Le Duan told Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai.Footnote 36

The Tet Offensive and follow-up campaigns produced none of the results expected by Hanoi leaders. They were, in fact, a complete disaster, costing the lives of more than 40,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong combatants.Footnote 37 However, support for the war in the United States had begun to fray, and images of American forces seemingly on the defensive only served to encourage emerging doubts. By March, events in Vietnam led Lyndon Johnson to withdraw from the presidential election and set in motion a series of highly public protests that would divide the United States and further erode popular will to continue the war in Southeast Asia. Hanoi snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. That is, what looked to be a severe setback for its cause became a major triumph. That triumph was a testament to the effectiveness of Hanoi’s diplomatic struggle, a fruit of its longstanding commitment to cultivating harmonious relations with noncommunist state and nonstate actors and exploiting anti-war sentiment in the West, including the United States.

In the aftermath of the offensive, in April, Hanoi opened peace talks with Washington. Despite what the gesture suggested, Vietnamese communist policymakers did not intend to negotiate seriously. Committed as ever to military victory, they used the talks merely to pander to world opinion, as well as to probe the intentions of American decision makers. Losses suffered by communist forces in the Tet campaign had been heavy, Le Duan recognized, but achieving unmitigated triumph over the United States remained essential to win “everything” in Vietnam, on the one hand, and contribute to the eradication of capitalism around the world, on the other. As long as capitalism existed, Hanoi’s thinking went, peace in Vietnam and elsewhere would be threatened and “peace-loving” peoples would never be truly safe. Just as the Soviet Union’s victory in the “Great Patriotic War against Fascist Aggression” had contributed to the demise of fascism as a viable political ideology, Vietnam’s victory over the United States would herald the demise of capitalism.Footnote 38 By official VWP account, American policymakers were “neo-fascists” bent since 1954 on depriving the Vietnamese people of peace and freedom by keeping the country divided.Footnote 39 In defeating the United States, Hanoi would discredit the ideology Washington held so dear. It would also by extension demonstrate the superiority of socialism and of socialist modernity over the capitalist, bourgeois reactionary system.

Moreover, sustaining the war effort until the United States was defeated would vindicate the forward strategy embraced by the VWP leadership since 1964 and, more broadly, the policy of active, aggressive struggle favored by orthodox Marxist-Leninists. Most overtly championed by Mao and other “radicals” in Beijing, that policy had run contrary to the policy of peaceful coexistence and peaceful resolution of East-West disputes sanctioned by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1956. American actions during the Chinese Civil War and then the Korean War reinforced Beijing’s view that defiance was the only realistic way of dealing with the United States. “War is the highest form of struggle for resolving contradictions,” Mao said, and starting in 1962 Beijing actively encouraged Hanoi to stand firm against American provocations, prepare to fight, and forego a diplomatic solution, as Moscow advocated.Footnote 40 By continuing the war effort, the Vietnamese could demonstrate their commitment to national liberation and avoid the mistakes made by their foreign comrades over Korea in 1953, when Pyongyang and Beijing had accepted a ceasefire and consented to the continued, permanent division of the peninsula. Victory in Vietnam could show the Third World that complete liberation by force of arms was not impossible and that it could be achieved even when the Americans themselves stood in the way. Besides, a determined stance against American imperialism in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive would restore revolutionary momentum and facilitate continued mobilization of public opinion at home and abroad.

Le Duan and other core leaders made no secret of their contempt for the Soviet “revisionist” line advocating negotiated solutions to East-West conflicts, and of their partiality to Chinese revolutionary prescriptions. Moscow resented Hanoi’s insubordination, its assertion of an independent and defiant policy more in line with China’s own stance in the global Cold War, affirmed by its decision to forego a diplomatic solution and rely on armed struggle to bring about national reunification. Soviet leaders inferred from that decision that Hanoi had aligned itself with Beijing in the Sino-Soviet dispute then wreaking havoc in the socialist camp. Though they refused to take a public stance in the Sino-Soviet split, DRV decision makers subscribed to Chinese revolutionary theses because they genuinely believed they constituted the best way of meeting core strategic objectives, domestically and internationally. Besides, the Vietnamese had their own ideas on the merits of revolutionary violence. “Only through the use of revolutionary violence of the masses to break the counter-revolutionary violence of the exploitative governing classes is it possible to conquer power for the people and to build a new society,” VWP theoretician Truong Chinh advised.Footnote 41 Violent revolution was the “only just path” to victory, just as using violence against class enemies represented a “universal law.”Footnote 42 In continuing to pursue final triumph over the United States, Hanoi demonstrated that violent struggle was most suitable given its own circumstances at the time and silenced detractors of its strategy.

Thus, through the post-1968 period, Hanoi steadfastly adhered to its revolutionary strategy predicated on armed struggle and defeat of the American “imperialists” despite what its participation in peace talks suggested. Over the next seven years, Le Duan and his regime met the bulk of their objectives, domestically and internationally. They defeated the United States and its allies and reunified Vietnam under their governance. That success roused Third World revolutionaries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. The culmination of wars for national liberation in Angola and Mozambique in the mid-1970s – just as Saigon fell to communist-led armies – and the support proffered to rebels there by the Soviet Union and Cuba, among others, were to no insignificant degree prompted by the triumph of the Vietnamese revolution and attendant American retrenchment from the Third World. In Latin America, leftist insurgents emboldened by events in Indochina and benefiting from Vietnamese moral and – in at least one instance – material support found new life and made meaningful gains in their struggles against right-wing dictatorships beholden to Washington.Footnote 43 The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) drew both lessons and strength from the experiences of the Vietnamese, and in fact came to see itself as closely intertwined with them in a common struggle against Western imperialism.Footnote 44

Hanoi’s anti-American resistance even had major ramifications in the West, where it produced great tumult. It contributed to a growing malaise there, variously dividing populations, driving a wedge between people and their governments, exacerbating socioeconomic tensions. It prompted mass protest movements from Paris to Chicago and facilitated the advent of anti-establishment radical organizations from West Germany to Canada. Most notably, the Vietnam War contributed to the emergence of a vigorous and raucous countercultural movement that seriously challenged and contested traditional sources of authority and, in some countries, brought about the collapse of governments or, at a minimum, a reassessment of the parameters governing executive power. According to historian Jeremi Suri, the countercultural movement was so disruptive in the West that it encouraged constructive engagement of the Eastern bloc by its leaders. Détente between the Soviet Union and the United States, rapprochement between Beijing and Washington, and Ostpolitik in Europe were each to varying degrees prompted by domestic challenges facing Western governments. Ultimately, East-West détente did not just reduce Cold War tensions; it indirectly helped build momentum in the Third World for national liberation causes.Footnote 45

In the eyes of its most ardent critics, the American war in Vietnam epitomized all that was wrong with the West: the disconnect between rulers and ruled, the disregard for the rights of others, the greed of capitalist entrepreneurs, and the abuse of power by government leaders. How else to account for the decision of American and other leaders to send so many young men halfway around the world to contain a “peasant insurgency,” to stand in the way of “good” and “valiant” “freedom fighters” merely seeking their country’s reunification and independence? To many critics, the refusal of Western leaders to do more to curtail the war in Vietnam was symptomatic of a growing generational gap, of the widely contrasting values of young people with those who had authority over them, the “over 30” generation. Opposing the war was for estranged youths a way to manifest their frustration with the status quo. It served as a vehicle to articulate myriad grievances and show that the existing system was not working, at least for them and other “oppressed” demographics at home and abroad. In time, opposition to the war, to the governments that abetted it, and to Western sources of authority broadly defined served as a rallying point for activists supporting a broad range of reformist and radical causes. It even facilitated the creation of transnational terrorist networks that brought together French-Canadian separatists, African American extremists, German radicals, Italian paramilitaries, Japanese communist militants, and Palestinian nationalists. While the Vietnam War was not the main reason these elements came together, it galvanized them like no other outside event.

Conclusion

Historian Huynh Kim Khanh maintained in an influential work that from its onset the Vietnamese revolution was both “a national liberation movement, governed by traditional Vietnamese patriotism” and “an affiliate of the international Communist movement, profoundly affected by the vicissitudes of the Comintern.”Footnote 46 To be sure, the Vietnamese revolution was never just a movement for national emancipation conducted under the auspices of dedicated rebels who were nationalists, first and foremost. Whether of moderate or hard-line persuasion, those rebels and particularly their leaders proved to be devout Marxist-Leninists and dedicated internationalists committed to class struggle and world revolution, just as they were to national liberation.

The internationalism espoused by Hanoi’s communist leaders was imbued with a clear ideological hue emphasizing the necessity of a socialist revolution to successfully resist and overcome American capitalist imperialism. In hindsight, a syncretic adaptation of Marxism-Leninism conditioned the thinking and behavior of Hanoi decision makers in the period 1954–75. That adaptation mixed a concern, an obsession really, with national liberation and Vietnamese reunification under communist aegis, on the one hand, with an aspiration to inspire and act as a vanguard for revolutionary movements across the Third World, on the other. According to Tuong Vu, the struggle waged by Hanoi after 1954 was “at heart, a communist revolution.” Leaders there were internationalists “no less than their comrades in the Soviet Union and China.” For Le Duan and his acolytes, “a successful proletarian revolution in Vietnam was a step forward for world revolution, which was to occur country by country, region by region.”Footnote 47

Hanoi’s leaders behaved as patriotic internationalists during the period from 1954 to 1975. They were not communists in the classical sense; nor were they mere nationalists, as is often assumed by American historians of the Vietnam War. They sought to co-opt all ethnic groups, not just ethnic Vietnamese, for the sake of freeing and reunifying their country. That made them patriots. They also cared deeply about the fate of revolutionary and other progressive movements elsewhere. In fact, they considered it their duty to contribute to the global revolutionary process, to the final triumph of communism, by rousing opponents of capitalism, imperialism, and neocolonialism everywhere. And that made them internationalists. Thus, as Vietnamese communist authorities committed themselves to defeating their enemies in Vietnam to preserve their country’s territorial integrity and secure its complete sovereignty, they sought to contribute to the worldwide struggle against imperialism and capitalism with a view to becoming a model, an exemplar, of the possibilities of national liberation and socialist as well as Third World solidarity. National liberation was for them, and for Le Duan in particular, a means to even greater, nobler ends: liberation of all oppressed masses, social advancement of the underprivileged, and the demise of imperialism and global capitalism. And in that respect, Vietnam’s revolutionary struggle shared an affinity with the Third World and the ideology of tiers-mondisme informing the decision-making of its more prominent leaders.

The pursuit of class struggle, a hallmark of committed Marxist-Leninist parties, was as central in Hanoi’s strategic thinking as southern liberation itself. However, the DRV knew better than to publicly mention or discuss that aspect of their revolutionary agenda because they understood it would alienate actual and potential supporters of their struggle outside the socialist camp, and in the Third and Western worlds, especially. In the immediate aftermath of the Geneva accords and partition of the country into two distinct regrouping zones, Vietnamese communist leaders set out to complete the land reform program they had initiated during the last year of the war against France and, shortly thereafter, nationalized industry and collectivized agriculture. Class struggle mattered to them, as it did to devout communists everywhere. And it is that commitment to class struggle, reaffirmed after the fall of Saigon through efforts to transform southern society and its economy along socialist lines, that set the DRV apart from non-aligned Third World states and faithful adherents to tiers-mondisme. While one could argue that the synthesis of Marxism-Leninism with tiers-mondisme effectively constituted Maoism (stressing anti-imperialism, the centrality of peasants in revolutionary processes, small-scale industry, rural collectivization, and permanent revolution), the syncretic ideology espoused by the Vietnamese in the post-1954 period proved far more complex. Most notably, that ideology comprised a diplomatic, internationalist component entirely absent from Maoism.

Noncommunist Third World states and sympathetic Western constituencies proved useful if not indispensable allies in Hanoi’s fight against a common enemy (imperialism) in pursuit of a common goal (liberation) to a singular end (communism). Le Duan believed that his people, having gained international notoriety for their contributions to decolonization through their war against France and their dramatic triumph at Dien Bien Phu, were in an ideal position to lead the charge against American imperialism, and inspire others to do the same. It was arguably Le Duan’s greatest aspiration to make all of this culminate on his watch.

In hindsight, DRV leaders supported the Third Worldist project only to the extent that it served their own purposes and its adherents supported their war effort against the United States. Between 1954 and 1975 they variously identified publicly as nationalists, non-aligned, supporters of national liberation, members of the Afro-Asian bloc, and neutralists. Ultimately, they only consistently and genuinely embraced Marxism-Leninism as they understood and defined that ideology. They respected other Third World regimes and movements, to be sure, but not to the extent they did those similarly committed to socialist transformation and unity, such as Cuba. In Hanoi’s own understanding, “true” Third World states, that is, genuine believers in the merits and full potential of tiers-mondisme, were those that looked to Marxism-Leninism as a blueprint for achieving complete liberation, economic development, political stability, and social harmony. As a militantly anti-imperial and avowedly Marxist state, the DRV positioned itself perfectly to shape and inspire the Tricontinental movement.

DRV leaders deserve credit for meeting their goals at home and abroad. They succeeded not only in reunifying their country under their own governance, but also in inspiring and emboldening “progressive” movements and individuals elsewhere. Their war against the United States profoundly impacted the Cold War system and left an indelible mark on the world. It did not herald the end of capitalism, but it did electrify national liberation fighters in the Third World. Clearly, that all came at a cost, an exorbitant cost, which the Vietnamese masses, not the men in Hanoi, assumed.

A near cloudless morning greeted Abdulrahim Farah as he stepped onto the tarmac of the Lusaka International airport on August 17, 1969. The fifty-year-old Somali diplomat was only months into his tenure as the chairman of the UN Special Committee on Apartheid. He had left New York in the midst of an intense summer heat wave and the city behind him – like most of America in 1969 – was simmering with tension. Surrounded now by an entourage of UN diplomats, Farah probably relished the change of scenery. Zambian soil must have been a welcome reprieve from his life as an expatriate in urban America.Footnote 1

However, turmoil was hard to escape in 1969. The Apartheid Committee Farah presided over had been established at the height of the so-called postcolonial moment, shorthand for the period when decolonization changed Africa’s political map between 1957 and 1963. The Committee had been the centerpiece of a set of initiatives that sought to use the United Nations to end white supremacy in Southern Africa, but those heady days were gone. Farah had journeyed to Zambia because he hoped to reach out to the liberation movements living there, many of which questioned the UN’s usefulness in the anti-apartheid fight, and to repair the bonds that once linked African people through Pan-Africanism.

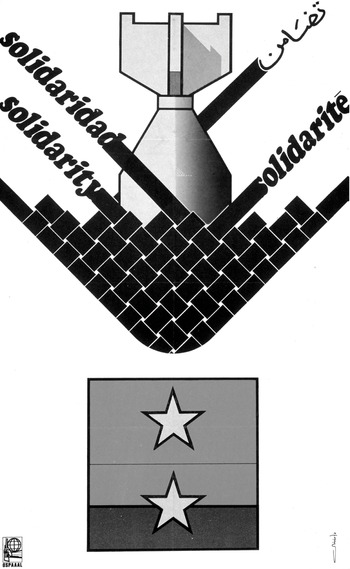

Figure 5.1 Tricontinental movements won support by combining political and social revolution, which often promoted the liberation of women alongside national independence. This image also attests to the global movement of iconography via Tricontinental networks. The Cuban artist Lazaro Abreu adapted this poster from an Emory Douglas illustration in The Black Panther depicting African revolutions. The combination of woman, gun, and baby appeared in Asian and African revolutionary imagery, which proved popular with young leftists in Europe and the United States. Lazaro Abreu after original by Emory Douglas, 1968. Screen print, 52x33 cm.

Things did not go well. During the Committee’s initial round of discussions, the African National Congress (ANC) requested that Farah and his associates stop seeking publicity for themselves and “humbly suggest[ed]” that these self-serving vacations had outlived their utility. “In our view it would be less expensive … if the United Nations invited, at its expense, delegations from genuine liberation movements to attend meetings … and assist in discussions and decisions.” Heralded once as the anvil that would destroy apartheid, the United Nations – and specifically the Apartheid Committee – was now portrayed as useless. In another meeting, an activist argued that “concrete evidence” proved that the United Nations was “a tool of the imperialist powers, particularly the United States,” while a third freedom fighter said that the “time for the verbal, the constitutional, was passed.” The only way forward now “was to face the enemy with a gun.”Footnote 2

Members of Farah’s party were taken aback. They saw themselves at the vanguard of the revolution against racial discrimination, and they were being told they were part of the problem. A few UN delegates accused the activists of being ignorant about “the workings of the United Nations.” However, Farah responded to the criticism directly. If the ANC wanted violence, it had to recognize that “nobody would pay any attention” until its members were “killed and maimed.” Ultimately, repudiating the Apartheid Committee was an act of self-isolation. Unless there “were more Sharpevilles” – a reference to a massacre outside Johannesburg in 1960 – “there would be indifference.”Footnote 3

What explains the hostility Farah faced in 1969? Arguably, the anti-apartheid movement was the most prominent social cause of the twentieth century; it lasted decades and drew support from people in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Australia, and Africa. But Farah’s experience reminds us that apartheid’s critics quarreled often and with considerable fervor. The anti-apartheid movement’s resilience, and eventually its ubiquity, stemmed from this fractiousness. Farah and the ANC disagreed about tactics, specifically the utility of special committees, and they articulated opposing conclusions about the United Nations’ usefulness in the worldwide decolonization movement. But both sides wanted legitimacy, and their boisterous fight, while not a zero-sum contest, made the apartheid issue harder to ignore during the second half of the twentieth century. Even as apartheid’s critics unanimously blasted the vagaries of white minority rule, they maneuvered among the subtle differences between solidarity and self-interest.

Historians of South Africa have largely ignored this tension. Astute monographs by Gail Gerhart and Tom Lodge consider rifts among anti-apartheid activists, but their books focus on black power and racial pluralism.Footnote 4 Although Stephen Ellis and Paul Landau offer an alternative framework, their work overdramatizes Moscow’s control of the ANC.Footnote 5 Hilda Berstein, Hugh Macmillan, and Scott Couper provide soberer accounts, lingering on the disagreements between the ANC’s various headquarters and the generational differences among its leaders, and Arianna Lissoni and Saul Dubow illuminate the way multiracialism and non-racialism contributed to the ANC’s factionalism.Footnote 6 Rob Skinner and Simon Stevens have even considered the ANC’s relationship with international anti-apartheid organizations.Footnote 7 But the national project of South Africa has framed all of this literature, and most of these authors have probed the liberation struggle in order to historicize the country’s turmoil in the twenty-first century.Footnote 8

Farah’s journey provides a different sort of starting point. While past scholars have tended to attribute splits within the liberation struggle to South Africa’s internal divisions, this chapter flips that approach inside-out, arguing that external events shaped the organization’s self-understanding. At the heart of the chapter is an obvious yet underexplored paradox. Forced into exile in 1960, the ANC’s underground paramilitary wing, uMkhonto weSizwe, was defeated in 1963. This defeat effectively ended the organization’s footprint within South Africa until the 1990s. Although ANC leaders continued to present themselves as spokesmen for an authentic, anti-racist South African nation – and stayed informed about events at home – the ANC existed primarily as a diasporic entity after the mid-1960s and many of its established truths lost the power to motivate the masses in these years. How could an organization that suffered so many setbacks maintain its place at the forefront of the anti-apartheid movement?

This chapter’s argument is straightforward: analogies matter. It studies the ANC’s road to and from the 1966 Tricontinental Conference and draws upon research from the ANC’s Liberation Archive to suggest that external comparisons – not internal divisions – determined how the ANC explained what it stood for and what it wanted after the Sharpeville Massacre. Critically, these analogies changed over time. During the early 1960s, the ANC equated itself to the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), which historian Jeffrey James Byrne critiques in Chapter 6. Initially, ANC leaders believed they could leverage diplomatic victories to defy minority white rule in South Africa. When the Algerian analogy faltered in the mid-1960s, the Cuban revolution became an alternative model for South Africa’s future. Fidel Castro’s apparent strength contrasted with the fate of Algeria’s Ben Bella (and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah), suggesting that real freedom required guerrilla warfare, not UN General Assembly resolutions. However, the ANC’s embrace of Che Guevara’s ideas set off a regional crisis that upended the organization in 1967, leading to the chapter’s final section on Vietnam. Divided internally by the late 1960s, the ANC responded to the Vietnam War by probing the logic and purpose of Third World solidarity, which offers a useful window to explore the relationship between revolutionary talk and revolutionary action after the Tricontinental Conference.

These shifting analogies served the ANC well. They helped the organization establish alliances with foreigners who never experienced apartheid, and they assuaged ANC expatriates who feared that Europeans would always rule South Africa. But most importantly, for the purposes of this book, the ANC’s efforts provide a microcosm to consider how the Tricontinental Revolution changed the Third World project. By studying the context around Farah’s rancorous encounter with the ANC in 1969, we can explain the tension between solidarity and revolution. After all, solidarity is what Farah was looking for in Lusaka. Yet he failed to obtain it because he was not a revolutionary. This chapter scratches at this tension while exploring how ANC leaders tangled with one of this volume’s organizing questions: Was Tricontinental solidarity an end in itself or was it a means to foment violent change in the decolonized world?

Exceptionalism

As late as 1960, ANC leaders refused to compare themselves to foreigners. Because apartheid differed from European imperialism, the argument went, the ANC’s struggle for majority rule had to be explained in the context of South Africa’s past. The ANC’s exceptionalism rested on a particular interpretation of history. An earlier rebellion against colonialism, fought in the late nineteenth century, pitted Dutch and British settlers against each other, and the forced migration of South Asians to the region significantly complicated the machinations of colonialism there. South Africa fit no mold, the argument went, and apartheid, which took shape after Afrikaner nationalists won power in 1948, elaborated British racism by repudiating Anglo-American liberalism, putting the country at odds with the rest of the English-speaking world after World War II. While apartheid’s critics took inspiration from Indian independence in 1947, the ANC’s 1952 Defiance Campaign, which imported Gandhian methods of civil disobedience to South Africa, neither changed government policy nor united the country’s various ethnic groups under a common banner. By the mid-1950s, it appeared that South Africa was sui generis.Footnote 9

This mindset created a distinct framework for political dissent. In South Asia, Jawaharlal Nehru spoke of a coherent Indian personality, channeled through the Indian National Congress. In South Africa, by contrast, the Congress Alliance, established after the Defiance Campaign’s defeat, argued that heterogeneity had to be the wellspring of anti-apartheid politics.Footnote 10 Within the Congress Alliance, the African National Congress spoke for indigenous Africans, while the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Trade Unions, the Coloured People’s Congress, and the Congress of Democrats represented other anti-apartheid groups. The birth of this alliance went hand in hand with a Freedom Charter in 1955 that framed South Africa as a place that “belonged to all who live in it, black and white,” accentuating the premise that South Africa would not follow the same path as India after 1947.Footnote 11 Rather than creating a racially homogeneous anti-colonial nation-state, the ANC would forge a politically plural and ethnically diverse democracy. If the Freedom Charter had an audience outside the country, it was probably the United Nations, a heterogenous organization invented to combat fascism, which had authored similar statements about politics after 1945. The Freedom Charter equated apartheid with fascism while dramatizing the difference between South Africa’s near future and South Asia’s recent past.

This approach began to buckle in the late 1950s. While the Congress Alliance struggled to gain traction within South Africa, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah used Nehru’s vision to spearhead the first successful anti-colonial movement in Sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote 12 After winning independence from Britain in 1957, Nkrumah called an All-African People’s Conference in 1958, proclaiming the need for a continent-wide “African Personality based on the philosophy of Pan-African Socialism.” Convinced that such a move would end the Congress Alliance, the ANC responded defensively. To comprehend “our aims and objectives,” ANC representatives informed Nkrumah and his supporters, outsiders needed to recognize South Africa’s “political, economic, and social development,” especially the fact that it was “the only country in Africa with a very large settled White population.” Because of “this history,” the statement continued, “our philosophy of struggle is ‘a democratic South Africa’ embracing all, regardless of colour or race who pay undivided allegiance to South Africa and mother Africa.” Although the ANC “support[ed] the cause of National Liberation,” it pointedly refused to adopt Nkrumah’s political vocabulary. The ANC faced a problem called “national oppression” – not foreign imperialism – and the remedy was not decolonization but “universal adult suffrage” within a democracy based on the Freedom Charter.Footnote 13 This argument not only undercut Nkrumah’s call for an all-encompassing African nationalism – modeled on Nehru’s Indian nationalism – but also reified the premise that South Africa was in but not of the African continent.

The ANC’s exceptionalism crumbled spectacularly after the All-African People’s Conference. Just a few months later, Robert Sobukwe, a former ANC Youth League leader who left the organization in the late 1950s, answered Nkrumah’s clarion call by organizing a new group called the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).Footnote 14 The organization announced its existence in 1959 and immediately attacked the ANC’s multiracialism as a “method of safeguarding white interests.” The ANC conceptualized South Africa’s future on Europe’s terms, Sobukwe argued, and failed to recognize the continuities between settler colonialism in South Africa and imperialism everywhere else. Part of the problem, in his mind, was the ANC’s relationship with the South African Communist Party (SACP), whose members seemed to take inspiration from European communists.Footnote 15 Because “South Africa [was] an integral part of the indivisible whole that is Afrika,” Sobukwe wrote in 1959, it followed that political power had to be “of the Africans, by the Africans, for the Africans.”Footnote 16 As the PAC cast the Freedom Charter aside, it attacked the presupposition that universal suffrage would end national oppression, proclaiming that a truly independent South Africa would have to belong to the “Africanist Socialist democratic order” that would soon stretch from Cape Town to Cairo. Decolonization was not only in South Africa’s future; it would arrive before 1963, Sobukwe declared in 1960. That was Nkrumah’s target date for African liberation and Pan-African unification.Footnote 17

The ANC lost control of events in early 1960. When British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan visited South Africa in February, he too attacked South African exceptionalism, albeit to critique apartheid’s architects for failing to acknowledge the “national consciousness” of non-Europeans.Footnote 18 Intended to sting Afrikaners who opposed the “winds of change,” Macmillan’s barb also challenged the ANC’s beleaguered worldview by conflating anti-apartheid activism with the movement that had recently ended British rule in Ghana. The Sharpeville Massacre, which featured so prominently in Farah’s commentary ten years later, unfolded weeks after Macmillan’s speech and culminated in the murder of almost seventy black South Africans. By April, no one on any side of the color line still believed that South Africa was sui generis. South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd insisted that the crisis had “to be seen against the backdrop … of similar occurrences in the whole of Africa,” and Nelson Mandela, who was emerging as a dynamic leader in the ANC, admitted, “In just one day, [the PAC] moved to the front lines of the struggle.”Footnote 19 Neither Verwoerd nor Mandela knew what would happen next, but they interpreted Sharpeville as tacit confirmation of Sobukwe’s worldview.

Liberation

In the aftermath of Sharpeville, the ANC took steps to reinvent itself. Verwoerd’s government declared a State of Emergency in May 1960, arresting ANC and PAC leaders and forcing both organizations underground. However, the ANC’s Deputy-President Oliver Tambo had already gone abroad, where he would prove a pivotal conduit to the outside world that year. Initially, Tambo found common ground with the ANC’s rivals, forming a United Front (UF) that included the PAC.Footnote 20 Undergirding this fragile alliance was the shared assumption that the United Nations would confront apartheid because sixteen African countries joined the General Assembly that year. For the first time since 1946, sanctions seemed to be a possibility. African diplomats appeared to hold sway over the UN General Assembly’s agenda, and the All-African People’s Conference had inspired an impressive boycott of South African consumer goods in Britain and the Caribbean.Footnote 21 “[A] solution could only come from the outside,” Tambo quipped in May 1960. Theoretically, a General Assembly resolution, labeling apartheid a clear threat to peace and security, would force the UN Security Council to punish South Africa, since the 1950 Uniting for Peace resolution had ostensibly vested the General Assembly with the power to supersede an obstructionist Security Council veto. Military intervention was an unrealistic goal. Yet economic sanctions seemed feasible, and the UF saw the United Nations as a tool to destabilize the apartheid system.Footnote 22 ANC President Albert Luthuli explained the situation succinctly in 1960: “I feel that … when South African markets are affected, the people … might feel that they would be better off with another form of Government.”Footnote 23

Obvious problems came into focus immediately. On the one hand, Verwoerd’s government outmaneuvered the United Front abroad.Footnote 24 On the other hand, the PAC and ANC struggled to overcome their underlying differences. Sobukwe, whom Verwoerd imprisoned in May, hoped sanctions would destroy white rule, so South Africa could follow in Ghana’s footsteps. Luthuli, also imprisoned that year (and awarded a Nobel Peace Prize), still clung to the ANC’s vision of pluralist democracy, believing that sanctions would split European sentiment in South Africa.Footnote 25 That mindset dwindled outside Oslo as the year progressed, and the SACP did not pull its punches when Luthuli’s underlings asked for feedback in the autumn. Most foreigners, the group explained, saw the ANC’s multiracial rhetoric as a front that “concealed a form of white leadership of the African national movement.”Footnote 26 African countries in particular were suspicious of the ANC and frequently nudged Tambo to accept the PAC’s supremacy in South Africa’s anti-colonial struggle. So, the ANC could either repudiate the SACP altogether – and tacitly acknowledge the validity of the PAC’s criticism – or find a new way to frame its relationship to Pan-Africanism. Change was necessary.

Algeria offered one way forward. That country, Mandela explained in 1961, was “the closest model to our own in that the rebels faced a large white settler community that ruled the indigenous majority.”Footnote 27 With help from the SACP, Mandela won support to create a paramilitary group called uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) that year and then spent most of 1962 in North Africa – his visit coincided with Algerian decolonization – where he received training from the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN).Footnote 28 In Mandela’s mind, the juxtaposition between Ghana and Algeria could not have been clearer. Whereas Nkrumah had won sovereignty by mobilizing Africans within Ghana, the FLN had organized at home and abroad, waging a guerrilla campaign on the ground while turning French colonialism into a cause célèbre at the United Nations. The combination was important. In Mandela’s private diary, he explained:

Your tactics will not only be confined to military operations but they will also cover such things as the political consciousness of the masses of the people [and] the mobilisation of allies in the international field. Your aim should be to destroy the legality of the Government and to institute that of the people. There must be parallel authority in the administration of justice.Footnote 29