Introduction

Governance determines economic development and growth.Footnote 1 Starting from Kaufmann et al. (Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Zoido-Lobatón1999, Reference Kaufmann, Kraay, Lora and Pritchett2002), the importance of governance has been stressed for several development outcomes, such as poverty alleviation, income inequality, entrepreneurship, foreign direct investment, and national well-being.Footnote 2 Given the implications of governance for growth and development, it becomes important to investigate its determinants. Surprisingly, studies exploring determinants of governance were scanty until early 2000 (Al-Marhubi, Reference Al-Marhubi2004) and sporadic thereafter, calling for the need to explore additional determinants of governance.Footnote 3 We add to the literature on governance determinants by presenting political legitimacy as a potential determinant of governance.

World Governance Indicators define governance as ‘traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised’ (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Kraay and Mastruzzi2010).Footnote 4 These traditions and institutions consist of three components: the process via which governments are selected and accounted for, the capacity of the state to formulate and implement its policies, and citizens' adherence to such policies. Therefore, better governance requires that citizens endorse the political system.

Such ideas constitute the concept of political legitimacy, citizens providing political support based on their evaluations of the state. For example, Lombardo and Ricotta (Reference Lombardo and Ricotta2021) argues that citizens' belief about a social contract, to follow for the good of everyone, legitimizes the government's actions. Interestingly, despite the studies exploring the determinants of governance for nations, no study so far, to the best of our knowledge, has studied whether political legitimacy determines governance. Perhaps, Pavlik and Young (Reference Pavlik and Young2020) is the only closely related study that, in the context of rich economies, investigates the relationship between representative assembly experience in medieval and early modern times and current state capacity. Therefore, we add to the strand of literature that explores governance determinants by investigating if political legitimacy plays any potential role in determining governance across countries.

Gilley (Reference Gilley2006) defines political legitimacy as political support encompassing evaluations of the state by the populace. A state's political legitimacy is the extent to which individuals regard a political system rightful or valid based on their primary values (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959). Political legitimacy implies that citizens accept the state's right to rule and conform to rules and regulations set by the state. In addition, political legitimacy reflects cultural alliance and normative support (Scott, Reference Scott2013).

A state's political legitimacy determines the quality of governance. The idea that citizens support the state's policies and actions and feel comfortable abiding by those rules matters significantly for governance because of three reasons. First, if citizens have confidence in the state's right to hold and exercise political power, it creates a conducive environment for the state to formulate and execute its policies, enhancing the quality and effectiveness of such policies. Second, conformity to rules and regulations creates a better rule of law, a critical governance component. Third, citizens feel comfortable voicing their opinions in a politically legitimate state without engaging in politically motivated violence. All these factors improve the quality of governance.Footnote 5 Therefore, political legitimacy determines the quality of governance.

Our paper hypothesizes that legitimacy improves governance in a country by building a better political system. For a country's sustained development process, it is important to nurture the confidence of the masses in the political system. This confidence is shown by the citizens' support of the state's policies and actions. Therefore, legitimate governments enjoy broader citizen support, fostering political stability and reducing the likelihood of unrest, establishing a framework for accountable, transparent, and effective governance. Although state institutions can coerce citizens to obey, coercion-based social order is not sustainable (Lukes, Reference Lukes2021). Thus, political legitimacy builds a better political system that provides superior public goods, improving the governance of a country.

On the other hand, contrary to our hypothesis, legitimacy may deteriorate governance in a country. For example, Holcombe (Reference Holcombe2021), in the social contract theory context, argues that legitimatizing the social contract, which can be viewed as society's rules, enhances the government's coercive power that it can use against minority groups. Holcombe (Reference Holcombe2021) argues that democratic institutions create an illusion of legitimacy through inclusive political processes. However, a minority (elites) makes policies for the masses by using propaganda and patriotism to legitimize these policies. These policies favour the political elites at the cost of the masses. Thus, based on Holcombe (Reference Holcombe2021), legitimacy can worsen governance. Our paper empirically investigates both these views by exploring whether legitimacy has a favourable or unfavourable effect on governance.

Furthermore, legitimacy can also affect governance, causing endogeneity concerns because of the reverse causality; better governance may make a state more legitimate, and a more legitimate state may provide better governance. Better governance can enhance a state's legitimacy for several reasons. First, when citizens perceive a state as effective, transparent, and accountable, they tend to show more trust in it, supporting its policies and legitimizing its rule. Second, good governance often improves economic and social outcomes by providing better public goods. When citizens see tangible benefits from their government's actions, they are more likely to view the government as legitimate. Third, when citizens are convinced of the state's legitimacy, they provide necessary funds (e.g. by paying taxes) to increase the state's capacity to govern better (Grier et al., Reference Grier, Young and Grier2022). Finally, good governance lowers corruption and abuse of power, major threats to a government's legitimacy. When citizens see that their leaders uphold the rule of law, they are more likely to view the government as legitimate. Therefore, better governance fosters trust, accountability, and positive outcomes, all of which contribute to a government's legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens. Due to this reverse causality, we consider legitimacy and governance endogenous.

We address this endogeneity concern by employing an instrumental variable strategy. Our instrumental variable consists of foreign countries' average diplomatic representation in a country. Foreign diplomatic representation satisfies the relevance and exclusion restrictions of an instrumental variable. It is a relevant instrument as it strongly correlates with our endogenous variable, political legitimacy. Foreign diplomatic representation positively correlates with political legitimacy, i.e. more foreign diplomatic representation in a politically legitimate state. Furthermore, it satisfies the exclusion restrictions because the primary role of foreign diplomats is to safeguard the interests of their home country, engage in bilateral negotiations, and advocate for the policies of their home nation rather than influence the governance of their stationed state. Therefore, we use the average foreign diplomatic representation in 2005 as an instrumental variable. We discuss this instrumental variable and its construction method in section ‘Robustness test 1: the instrumental variable estimation’.

Our paper adds to the existing literature by providing an empirical macro analysis of the relationship between political legitimacy and various governance dimensions. Our empirical analysis is based on a cross-section sample of 66 countries. We use the rule of law variable, taken from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), and the quality of governance, taken from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), as our benchmark governance indicators. In addition, we test the robustness of our results by using other World Bank governance indicators.

Our main results show that if political legitimacy increases by one standard deviation (legitimacy improving from Mexico to Estonia), the rule of law increases by about one-third standard deviation, i.e. the level of governance improving from Jordan to that of Latvia or Poland. The impact is qualitatively similar for the alternative governance measures and the instrumental variable estimation. Moreover, our results hold after controlling for other covariates of governance. Finally, our results show that in the presence of greater trust, political legitimacy has an enhanced impact on governance.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: second section presents a brief literature review, third section provides data description, fourth section reports the empirical methodology and results, fifth section reports conditional effects, and sixth section concludes.

Literature review

Our paper overlaps with two strands of literature. First, it overlaps with a vast strand of literature that explores governance and its determinants. Second, it overlaps with a scarce strand of literature on political legitimacy.

Our paper expands the economic literature on the determinants of governance, a robust determinant of economic development (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Dam, Reference Dam2007; North, Reference North1991) and several other positive economic outcomes.Footnote 6 Furthermore, our paper intersects with the literature that utilizes economic freedom as a more extensive governance measure.Footnote 7 In doing so, our paper relates to Barro (Reference Barro1996, Reference Barro1997); La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999); Treisman (Reference Treisman2000); Mukherjee and Dutta (Reference Mukherjee and Dutta2018) who explore cross-country determinants of governance.

In addition, our paper relates to studies considering specific components of governance (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Fiess and MacDonald2010; Bonaglia et al., Reference Bonaglia, De Macedo and Bussolo2009). Similarly, Adkisson and McFerrin (Reference Adkisson and McFerrin2014) show culture as a significant determinant of governance. Honda (Reference Honda2008) finds that the IMF financial assistance affects the economic governance of developing countries. Rontos et al. (Reference Rontos, Syrmali and Vavouras2015) associate the role of political freedom in explaining governance across nations. Garcia-Sanchez et al. (Reference Garcia-Sanchez, Cuadrado-Ballesteros and Frias-Aceituno2013) relate education with government effectiveness. Other related literature includes Dawson (Reference Dawson2013), who summarizes the literature on the determinants of state capacity. This can constitute broad and direct taxation (Brautigam et al., Reference Brautigam, Fjeldstad and Moore2008; Moore, Reference Moore2004), democracy along with its competitiveness (Geddes, Reference Geddes1994; Hall and Jones, Reference Hall and Jones1999; Lake and Baum, Reference Lake and Baum2001), ethnic diversity (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Easterly and Levine, Reference Easterly and Levine1997; La Porta et al., Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999; Miguel and Gugerty, Reference Miguel and Gugerty2005) among others.

While other determinants of governance have been explored extensively in the literature, to our knowledge, economic literature neglects political legitimacy as a potential determinant of governance. Though not widely explored in the context of development or governance, the role of political legitimacy has been emphasized in recent decades. Studies have emphasized that a state's stability can be jeopardized in the absence of political legitimacy (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2008; Lake, Reference Lake2007; Rotberg, Reference Rotberg2010). On the other hand, state capacity that complements political legitimacy resolves violent disputes (Jensen and Ramey, Reference Jensen and Ramey2020). Similarly, Charron et al. (Reference Charron, Dahlström and Lapuente2012) show that the state formation process (legitimacy) affects governance across 31 OECD countries.

In the context of development policy, legitimacy has been shown to be key for state fragility (DFID, 2010). François and Sud (Reference François and Sud2006) state that many conflict-driven nations have not been able to (re)gain political legitimacy. World Bank thus has aptly described the significance of legitimacy by calling it the ‘strategic centre of gravity’ (Zoellick, Reference Zoellick2009). Some studies have explored specific aspects of legitimacy, focusing on certain countries or regions. For example, Useem and Useem (Reference Useem and Useem1979) suggest that political legitimacy is a pre-condition for political stability in capitalist democracies, and a lack of confidence in a political regime might call for dissidence and anti-state protests. Another strand of literature stresses the critical role of legitimacy in promoting legal compliance (Marien and Hooghe, Reference Marien and Hooghe2011; Tyler and Jackson, Reference Tyler and Jackson2014).

Perhaps, Pavlik and Young (Reference Pavlik and Young2020) is the closest related study that examines the relationship between the historical experiences of representative assemblies (legitimacy) and present-day state capacity in Europe. They find that greater assembly experience (legitimacy) is associated with higher tax revenues, reduced shadow economic activity, increased government control over violence, and lower military expenditures. However, to our knowledge, no study explores political legitimacy as a potential determinant of governance across countries. Our paper fills this gap by exploring whether the statistical association between political legitimacy and governance exists.

Data

Our paper uses cross-sectional data from 66 countries (N = 66) for this analysis.Footnote 8 This section briefly presents the key variables.

Dependent variable

Our main dependent variable is a measure of governance. Since the multi-dimensional notion of governance can be difficult to capture in a single variable (Bjørnskov, Reference Bjørnskov2010), we use a broad set of measures to make sure our results are not sensitive to particular variables. As part of our benchmark measures, we consider two sets of variables that capture different aspects of governance. The two considered measures are the rule of law from the WGI database and the indicator of the quality of government from the ICRG. The data provided by WGI are aggregated from several sources, including surveys of firms and households, non-governmental organizations as well as public sector organizations (Kaufmann and Kraay, Reference Kaufmann and Kraay2008; Kaufmann et al., Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2008; Thomas, Reference Thomas2010).

Our first governance indicator, the rule of law, captures citizens' perceptions in the context of having confidence in the rules of the society and abiding by them. Langbein and Knack (Reference Langbein and Knack2010) point out that the presence of an open, ‘white’, transparent market is captured in the rule of law where contracts are enforced collectively with accountability and not privately. The extent to which property rights are protected is also reflected in the rule of law. Similar to all other WGI governance measures, the variable ranges from −2.5 to 2.5, with higher numbers implying a better rule of law. The mean for our sample is about 0.4. This governance indicator is standardized to make interpretations easier.

Our second governance indicator, the quality of government, is constructed using the average of the three individual measures, i.e. law and order, bureaucratic quality, and corruption. While the law component of law and order assesses the strength and neutrality of the legal system, order measures the extent to which the populace observes the law. In the case of bureaucratic quality, higher points are assigned to countries where bureaucracy functions without significant interruptions. Finally, corruption assesses all forms of corruption, from nepotism, job reservation, unhealthy ties between business and politics to financial corruption faced by firms. The constructed measure, quality of government, is standardized.

As part of robustness analysis, apart from using the above two benchmark measures, we consider the following governance measures from WGI: control of corruption, voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, and regulatory quality. We talk about these measures and describe the results in fifth section.

Main explanatory variable

Our main explanatory variable, political legitimacy, shows the extent to which the citizens believe that the state rightfully holds and exercises political power. Gilley (Reference Gilley2006) defines, ‘a state is more legitimate the more that it is treated by its citizens as rightfully holding and exercising political power’. In other words, political legitimacy captures the extent to which the citizen believes that the state rightfully holds and exercises political power abiding by rules and laws according to shared principles, ideas, and beliefs. The data of political legitimacy come from Gilley (Reference Gilley2012), who collects data on political legitimacy scores of 72 states.Footnote 9 These states comprise 83% of the world's population. In our sample, the mean value of political legitimacy is 5.12, with a standard deviation of 1.31 (Table 1). Denmark has the highest legitimacy score of 7.62, while Pakistan has the lowest score of 2.41 in this dataset.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Political legitimacy is shown by three indicators: views on legality, views on justification, and acts of consent.Footnote 10 Views on legality consist of two questions from the World Value Survey (WVS) – perceived respect for human rights and confidence in the justice system. The questions are considered from the 2004–2008 wave, and responses include ‘some’ or ‘a lot’. Three factors are included in views on justification. Two questions are taken from WVS. These include the extent of confidence in civil service and how democratically the country is being governed. The responses for confidence consist of ‘some’ or ‘a lot’. The democracy variable ranges from 1 to 10. The third factor comes from the Center for Systemic Peace. It is the sum of security legitimacy (repression) and political legitimacy (exclusion) scores. Finally, consent consists of two factors taken from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA). The data of these three indicators comprise nine indicators that are transformed into a 0–10 scale score. We standardize the variable for our analysis.

Control variables

We fall back on existing literature and choose several control variables correlated with governance. First, we control for the level of democracy. Democracy captures the effect of civic participation through an electoral process which puts a constraint on the government, improving the quality of government. Second, we include trade openness that is essential for governance, especially in the context of corruption. Ades and Di Tella (Reference Ades and Di Tella1999) and Treisman (Reference Treisman2000) suggest that with greater openness, competition is enhanced, lowering the incentives to engage in corruption since rent share goes down. Third, we control for trust. Bjørnskov (Reference Bjørnskov2012) shows the importance of trust for accountability and governance. In the context of institutional trust, studies have shown that it can effectively enhance legitimacy (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Dassonneville and Marien2015; Mishler and Rose, Reference Mishler and Rose2005). Moreover, Kaasa and Andriani (Reference Kaasa and Andriani2022) find that trust is lower in regions with larger power distance.

Fourth, Mauro (Reference Mauro1995); Easterly and Levine (Reference Easterly and Levine1997); La Porta et al. (Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1999); Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999); Treisman (Reference Treisman2000) show that legal tradition and ethnolinguistic fractionalization determine governance across countries. Fifth, we control for the population growth rate. Sixth, we include primary school enrolment that has been used as proxy of economic development (Al-Marhubi, Reference Al-Marhubi2004; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Rueschemeyer and Stephens1993).

Moreover, distance from the equator shows the strength of past Western European influences, which has been shown to affect governance (Al-Marhubi, Reference Al-Marhubi2004). Following Hall and Jones (Reference Hall and Jones1999) and Al-Marhubi (Reference Al-Marhubi2004), we control for latitude as a proxy for distance from the equator. Further, religion also affects governance (Al-Marhubi, Reference Al-Marhubi2004; Landes, Reference Landes1998). In particular, the literature shows that Protestantism leads to better governance because they have a more egalitarian, less hierarchical, and more individualistic outlook than other religions. Therefore, we control for the percentage of protestants in our specifications.

Finally, richer countries can foster good governance since social and cultural changes are brought about via greater economic development that, in turn, increase the premium on better governance (Huber et al., Reference Huber, Rueschemeyer and Stephens1993; Leonardi et al., Reference Leonardi, Nanetti and Putnam2001; Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Rosenberg and Le, Reference Rosenberg and Le2008; Thrainn, Reference Thrainn1990). Therefore, we include the income per capita in our specifications.

Empirical analysis

Model specification

Employing a sample of 66 countries, we test the relationship between political legitimacy and governance. Following Bjørnskov (Reference Bjørnskov2010), we estimate the below specification.

Here, Gov represents a specific governance indicator for country i. Legitimacy shows the political legitimacy score for country i. X contains the matrix of benchmark controls. We standardized both the dependent and our main explanatory variables to get beta coefficients, showing the standard deviation change in the dependent variable due to a one-standard deviation change in legitimacy. We employ OLS regression as a benchmark and instrumental variables regression as a robustness test.

Hypothesis

We test the following hypothesis based on the above discussion and econometric specification.

Hypothesis: Political legitimacy enhances governance across nations, i.e.

Partial correlations

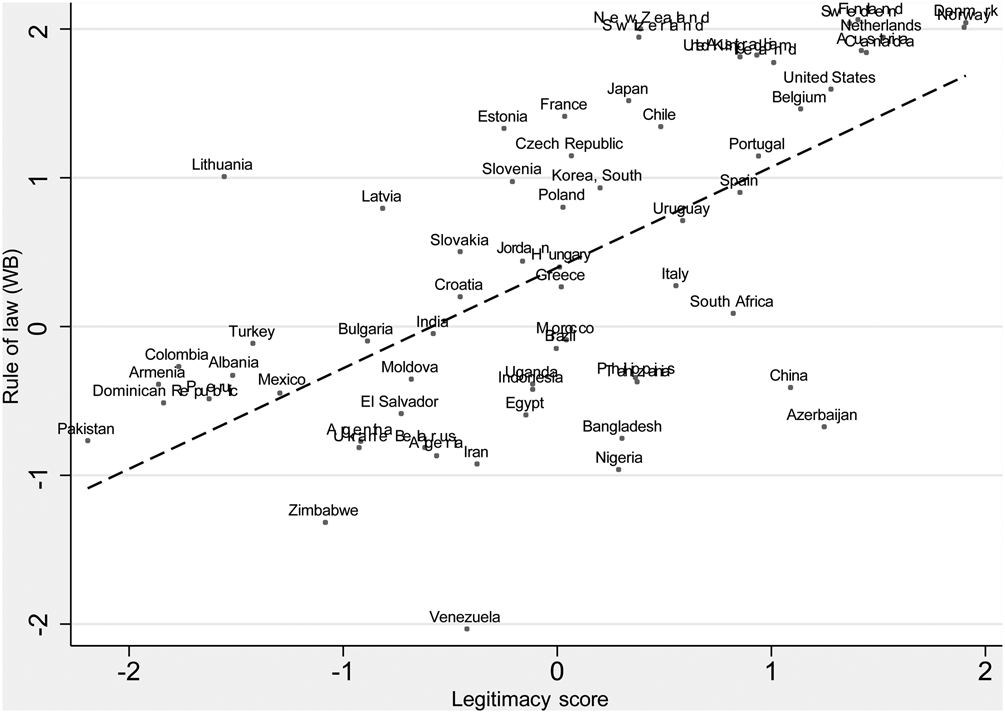

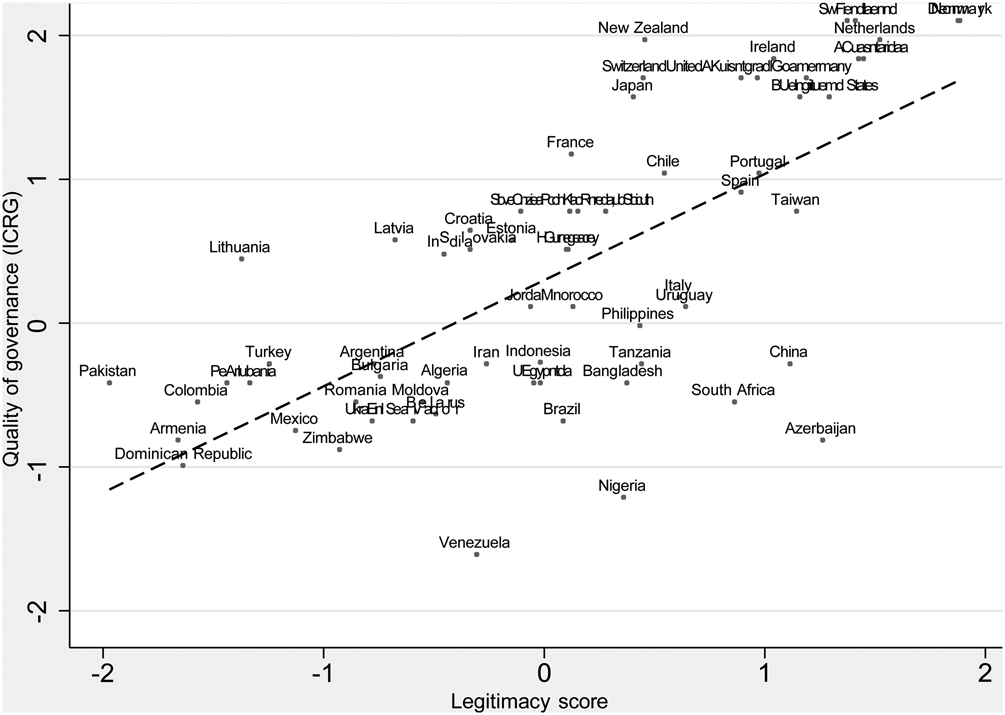

We start our empirical evidence with exploratory analysis and partial correlations between key variables. First, we present the relationship between governance and political legitimacy via scatter plots. Figure 1 presents the scatter plot for the rule of law (WB) measure with political legitimacy. Figure 2 considers the quality of government (ICRG) measure. Both governance indicators show a clear positive relationship with political legitimacy in both Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Legitimacy and the rule of law (WB).

Figure 2. Legitimacy and the quality of governance (ICRG).

Second, we look at the relationship between governance and political legitimacy via correlation coefficients. Table 2 reveals that our benchmark governance indicators, the rule of law and quality of government, are significantly correlated with political legitimacy, shown by the correlation coefficient values between 0.64 and 0.69. This table also shows the partial correlation coefficients of about 0.60 between several other governance indicators and political legitimacy. The rest of the paper provides statistical tests to explore this relationship further.

Table 2. Correlation matrix

∗ P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Main results

The previous section shows that there may be a positive relationship between governance and political legitimacy. In this section, we explore this relationship in the regression modelling framework.

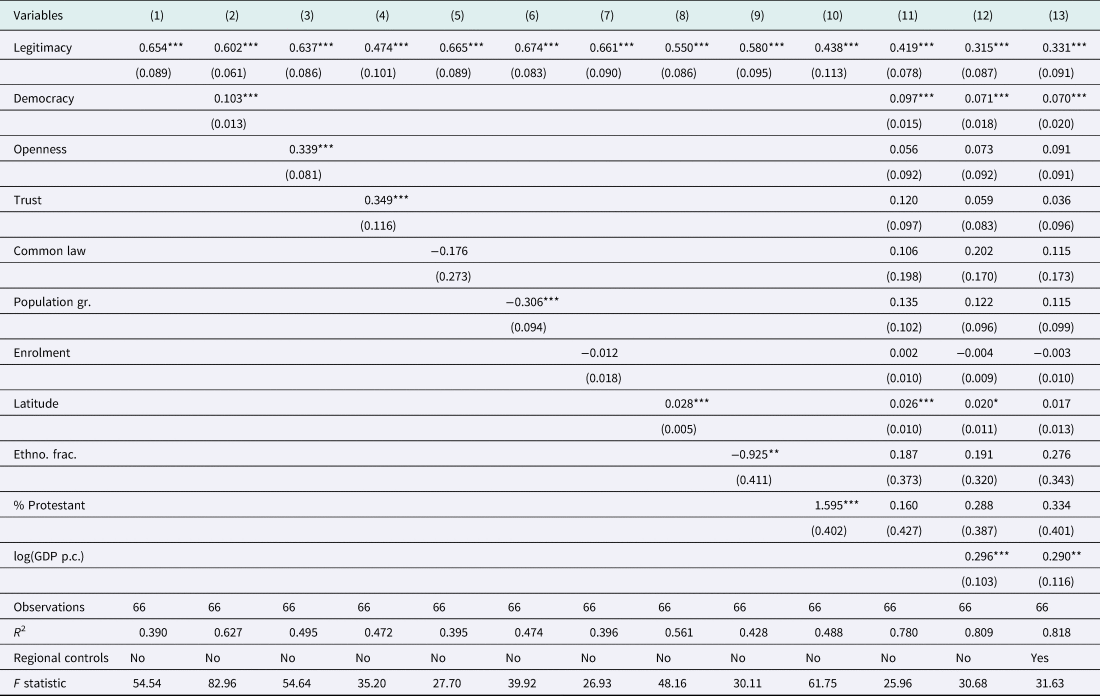

In Table 3, we present our first set of benchmark results. Here, we use the rule of law variable from the WB to measure governance. We present the bivariate relationship in column (1) and then add controls in subsequent columns. Since the controls can be potentially correlated with one another, we include them one at a time along with political legitimacy before adding them all in subsequent columns.

Table 3. Main results: legitimacy and the rule of law (WB)

Notes: ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Column (1) results suggest that political legitimacy explains about 39% of the variation in governance across nations. A standard deviation rise in political legitimacy is associated with a little more than half standard deviation rise in the rule of law. In subsequent columns, we add the controls for democracy, trade openness, trust, common law, population growth, primary school enrolment, latitude, ethnolinguistic fractionalization, and per cent of protestants – one by one, respectively. The impact remains similar to column (1) – a standard deviation rise in political legitimacy is associated with more than half or half standard deviation rise in the rule of law. The impact is less in columns (4) and (10). In column (11), we add all the controls together. Finally, in column (12), we add GDP per capita (log) along with all the controls.

Since income is likely to correlate with most explanatory variables and political legitimacy, we include this at the very end. This column shows that one standard deviation (1.31) increase in political legitimacy improves governance by one-third standard deviation. Quantitatively, this means that an increase in political legitimacy equivalent to moving from Mexico to Estonia corresponds to an improvement in governance from the level of Jordan (0.43) to that of Latvia (0.79) or Poland (0.80).Footnote 11

We find that political legitimacy and all controls, including GDP per capita, can explain 80% of the variation in the rule of law across nations. Despite all controls, regional characteristics can affect governance differently, and political legitimacy might be capturing some of that effect. To make sure we solely capture political legitimacy's impact on the rule of law, we control for regional dummies in column (13). The results remain robust.

In Table 4, we re-run the specifications employing the alternate measure of governance – the quality of government from ICRG. Table 4 format is similar to that of Table 3. However, Table 4 contains only 64 countries instead of 66 because of data availability. Without controls, political legitimacy explains about 46% of the variation in the quality of government. In terms of impact, a standard deviation rise in political legitimacy enhances the quality of government by about one-third standard deviation. The impact remains approximately identical with the controls in the subsequent columns. When all controls are added along with GDP per capita, the rise in quality of government for a standard deviation rise in political legitimacy is about one-fourteenth standard deviation. The impact is similar when regional dummies are added.

Table 4. Legitimacy and quality of governance (ICRG)

Notes: ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

We hypothesize that political legitimacy enhances the governance of nations. Our benchmark results show robust evidence of an association between governance and political legitimacy even after controlling for an array of variables shown to be important governance determinants.

Robustness tests

This section further reinforces our main findings in the previous section by presenting two robustness tests. Our first robustness test considers instrumental variables strategy to deal with any potential endogeneity concern. Our second robustness test consists of using several alternative governance indicators.Footnote 12

Robustness test 1: the instrumental variable estimation

As discussed in the introduction, endogeneity may be a potential issue in our model. Governance and legitimacy might mutually influence each other. Moreover, other unknown factors may simultaneously affect both. We use an instrumental variable approach to address this issue, treating legitimacy as endogenous.Footnote 13

Our instrumental variable consists of foreign countries' average diplomatic representation in a country. Foreign diplomatic representation positively correlates with the legitimacy of a state; we may observe more foreign diplomatic representation in a legitimate state. However, in the modern democratic world, foreign diplomatic representation cannot directly affect the governance of a country because the key function of foreign diplomats is to protect the sending countries' interests in their posted state. They can facilitate strategic agreements that promote commerce and friendly relations but cannot influence governance in their assigned country.

Even if we assume that foreign diplomats directly engage in shaping the governance of their assigned state, the outcomes may be uncertain or even detrimental. There are numerous examples of well-intentioned endeavours falling short in their pursuit to establish Western-style modern democracies in foreign countries, as seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, among others. If these extensively funded initiatives encountered substantial challenges, setbacks, and, ultimately, failures, it raises questions about the extent of influence diplomats truly have in impacting the governance of their designated states. Additionally, considering that we are using average diplomatic representation data of all 65 countries in our sample, it becomes difficult to imagine that every one of these nations is interested in enhancing the governance of a foreign state.

Therefore, we use the average diplomatic representation of all diplomats in 2005 as an instrumental variable in the first stage. This variable is taken from Bayer (Reference Bayer2006). Diplomatic representation variable shows the average foreign countries' level of diplomatic representation in a country. In our sample, it takes four possible values: 0 = no evidence of diplomatic exchange, 1 = charg´e d'affaires, 2 = minister, and 3 = ambassador.

The ‘average diplomatic representation’ variable is constructed by collapsing the original bilateral data set into cross-sectional data. For each country, the collapsed variable indicates the average level of diplomatic representation it received from all other 65 countries in the sample. For example, if a country has diplomatic representation levels of 0, 1, 2, and 3 from four other countries, the average diplomatic representation it received would be (0 + 1 + 2 + 3)/4 = 1.5. This process is repeated for all countries in the data set, resulting in a single variable reflecting the average level of diplomatic representation each country receives from other 65 countries in the sample. The US receives the highest level of diplomatic representation (2.74), and Moldova receives the lowest (0.20), indicating a high level (ambassador level) of diplomatic representation in the US and a low level (more than no but less than charg´e d'affaires level) of representation in Moldova. The average ‘average diplomatic representation’ across countries is about 1, indicating the average diplomatic representation at the charg´e d'affaires level.

Table 5 reports instrumental variable estimates. Column (1) shows the estimates of the rule of law indicator, and column (4) reports the ICRG quality of governance variable as dependent variables. Our main explanatory variable, legitimacy, remains statistically significant with point estimates relatively stable and comparable to earlier results in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 5. Robustness tests with the IV estimation

Notes: ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Robust standard errors in parentheses. This table reports estimates for the WB rule of law and ICRG quality of governance variables using two methods. First, columns 1 and 4 report the instrumental variable estimates for these variables. Second, columns 2–3 present the Lewbel IV estimates (Lewbel, Reference Lewbel2012) for the WB rule of law variable, with and without external IV. Similarly, columns 4–5 present the Lewbel IV estimates for the ICRG quality of governance variable, with and without external IV, respectively. To calculate the Lewbel method, we used average diplomatic representation as an external IV in columns 3 and 6.

In addition, the first-stage tests reveal that our instrumental variable is adequately correlated with the endogenous variable, legitimacy, shown by the positive and statistically significant coefficient values of our instrumental variable. In addition, Figure 3 shows that these two variables are positively correlated. Moreover, the first-stage F-test values are greater than the benchmark value of 10 in both cases. Staiger and Stock (Reference Staiger and Stock1997) argue that the first-stage F-test value less than 10 indicates weak instruments. We find a high F-test value of 31.43 for the IV regression if we exclude other control variables from the equation, suggesting a strong link between legitimacy and diplomatic representation.

Figure 3. Legitimacy and diplomatic representation.

However, instrumental variables methodology faces challenges, such as weak instruments, exclusion restriction violation, relevance, measurement error, and endogeneity. Finding suitable instruments is crucial to tackling these problems. Two tests, the first-stage F-test and Hansen J-test are used to test the relevance and validity of the instruments. Since our model is just-identified with only one endogenous variable and one instrument, the validity of the instruments cannot be checked. Therefore, we supplement these OLS instrumental variables results with Lewbel's instrumental variables estimator (Lewbel, Reference Lewbel2012; Rigobon, Reference Rigobon2003) to reinforce our main findings. This method, introduced by Lewbel (Reference Lewbel2012) and Rigobon (Reference Rigobon2003), allows for identification when traditional instruments are weak, or exclusion restrictions are questionable.Footnote 14 Instead of relying on traditional exclusion restrictions, Lewbel's method utilizes heteroscedasticity in the endogenous explanatory variables to create instrumental variables.

We test the heteroscedasticity in our regression model using the Breusch–Pagan test. This test shows the value of χ 2 = 5.07, and P-value = 0.024, suggesting the presence of heteroscedasticity in the model that could be used to build the instrumental variables. Next, we test the validity of our instrumental variable using the Hansen J statistic. In all cases, the P-value of this test is large enough to conclude that the instruments are valid.

In Table 5, columns 2–3 present Lewbel's instrumental variable estimates for the rule of law variable. Column 2 utilizes heteroscedasticity to construct the instruments, while column 3 adds an external instrument, diplomatic representation. The coefficient values for our main variable, legitimacy, remain stable in both columns, but the standard errors are reduced by over 50% using Lewbel's method. Finally, columns 5–6 show Lewbel's instrumental variable approach for the quality of governance variable, with and without external instruments. Again, the coefficient values remain robust, and the standard errors are smaller using Lewbel's method.

To address endogeneity concerns, we use the instrumental variable strategy with the average level of foreign diplomatic representation in a country as the instrumental variable. The instrumental variable estimates indicate that the primary explanatory variable, legitimacy, remains statistically significant. In addition, we also use Lewbel's instrumental variables estimator to strengthen our findings when traditional instruments are weak, or exclusion restrictions are questionable. These robustness tests confirm the association between governance and political legitimacy. In conclusion, our study establishes that political legitimacy is a statistically significant determinant of governance across nations.

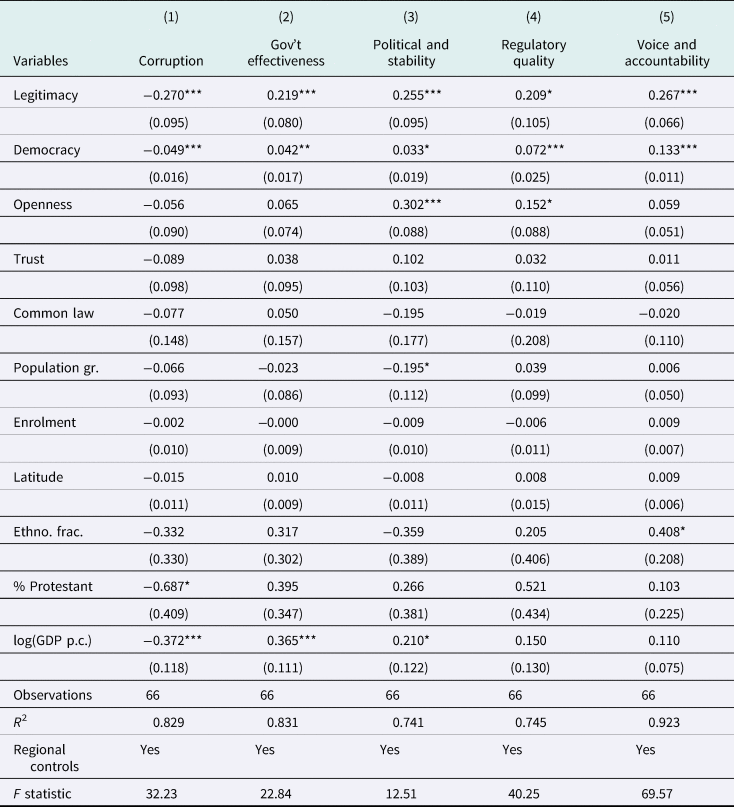

Robustness test 2: alternative measures of governance

We start the robustness of our benchmark results by using several alternative governance measures. Here, we consider five governance indicators from WGI: (1) control of corruption, (2) government effectiveness, (3) political stability and absence of violence, (4) regulatory quality, and (5) voice and accountability. The control of corruption variable measures the perceptions about how public power is exploited for private gain. Along with capturing ‘capture’ of the state by elites, it also incorporates petty and grand forms of corruption. The government effectiveness indicator measures the ability of a government to deliver public as well as civil services. In addition, this index measures the extent of independence of the bureaucracy from political influence. The political stability and the absence of violence variable captures the orderliness based on established rules that should be present during political transitions (Langbein and Knack, Reference Langbein and Knack2010). The lack of that order might call for overthrowing of the government and associated violence. The regulations, both formal and informal, define the relationship between the public and private sectors. Regulatory quality measures the extent to which such regulations promote growth and development rather than just being burdensome. Finally, the voice and accountability variable captures the extent to which citizens can hold politicians accountable and can voice their opinions through the media and associations. The mean values of government effectiveness, regulatory quality, and voice and accountability are similar to our benchmark measure, the rule of law (see Table 1). The mean value of political stability is almost close to zero, and corruption has the lowest mean value (−0.31) among these variables.

We present the results in Table 6. We remind our readers that corruption measure from WGI has been rescaled to make interpretations easier. Higher numbers denote greater corruption. The coefficient of legitimacy for the alternative measures of governance is significant in all the specifications. As expected, the sign is positive for all the specifications except in the case of corruption, for which it is negative. In terms of economic significance, the impact of legitimacy looks similar across the specifications. A standard deviation rise in political legitimacy enhances governance (be it in terms of government effectiveness, political stability, regulatory quality, or voice and accountability) by about one-fourth standard deviation. In the case of corruption, the effect is similar; a similar rise in political legitimacy reduces corruption by about one-fourth standard deviation. Based on these results, we conclude that political legitimacy is a statistically significant determinant of governance, and this effect is robust across several dimensions of governance indicators.

Table 6. Robustness tests with alternative governance indicators

Notes: ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

We established a statistically significant association between political legitimacy and governance in the preceding section. This section reinforces those findings by applying an instrumental variable approach, Lewbel's instrumental method, and examining various alternative governance indicators. Our results confirm that political legitimacy is a strong and statistically significant factor affecting governance across different nations. Therefore, we conclude that political legitimacy is a robust and statistically significant determinant of governance.

The moderating effect of trust

Next, we proceed to check if trust mediates the positive relationship between political legitimacy and governance. In recent decades, the role of trust has been emphasized to be indispensable for economic development (Beugelsdijk et al., Reference Beugelsdijk, De Groot and Van Schaik2004; Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2000; Zak and Knack, Reference Zak and Knack2001). Social scientists have explored the role of trust in facilitating cooperation and collective action among individuals (Durante, Reference Durante2009), in skill formation and education attainment (Bjørnskov, Reference Bjørnskov2009; Dearmon and Grier, Reference Dearmon and Grier2011; Özcan and Bjørnskov, Reference Özcan and Bjørnskov2011), in enhancing accountability and governance (Bjørnskov, Reference Bjørnskov2012), in boosting total factor productivity (Bjørnskov and Méon, Reference Bjørnskov and Méon2015; Dearmon and Grier, Reference Dearmon and Grier2011) in promoting international trade (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2009) and in pacifying gendered attitudes along with individualism (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Giddings and Sobel2022).

Political Science studies find that efficient and inclusive institutions, a critical component that shapes political legitimacy, enhance social and institutional trust (Freitag and Bühlmann, Reference Freitag and Bühlmann2009; Kumlin and Rothstein, Reference Kumlin and Rothstein2005; Lombardo and Ricotta, Reference Lombardo and Ricotta2021; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2001). Thus, we control for trust in our specifications to ensure that we are not capturing the same effect. Moreover, Bowles and Gintis (Reference Bowles and Gintis2002) argue that social capital (another term for trust used in the literature) and governance go hand in hand. Similarly, Uslaner (Reference Uslaner2003) argues that generalized trust leads to a populace satisfied with government performance and better governance. In other words, trust increases political legitimacy and governance. It implies that trust can affect governance indirectly through political legitimacy as well. Therefore, we check for the interaction effect of trust and political legitimacy on governance.

We test this interaction effect by including an interaction term between legitimacy and trust in our benchmark specification. This interaction term shows the marginal effect of legitimacy on governance conditioned upon the level of trust in a country, enabling us to understand at what levels of trust legitimacy has a positive effect on governance. We estimate the following regression equation:

Table 7 reports the results for the above model. Column (1) reports the results for the WB rule of law as a dependent variable, and column (2) presents ICRG quality of governance. The total effect of legitimacy conditioned on the average trust is positive and statistically significant in both columns. These total effects indicate that, on average, if legitimacy increases, conditioned on the mean value of trust, governance increases.

Table 7. Legitimacy and trust: an interaction effect

Notes: ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

However, the interpretation of a model with an interaction term is complicated because the estimated effects do not represent the unconditional marginal effects. Moreover, the standard errors and the statistical significance of individual estimated effects are irrelevant. Instead, we calculate conditional marginal effects and new standard errors to construct confidence intervals around these marginal effects.Footnote 15 First, we obtain conditional full marginal effects by taking the cross-partial derivative of equation (2) with respect to legitimacy as follows:

Second, we recalculate the standard errors of the marginal effects in equation (3) as:

A negative covariance term implies that β 1 + β 3Trust is statistically significance even if all other coefficient values are statistically insignificant (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Golder and Milton2012; Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006; Braumoeller, Reference Braumoeller2004). This implies that the full marginal effects are statistically significant if both the upper and lower bounds of confidence intervals are either above or below the zero line (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006).

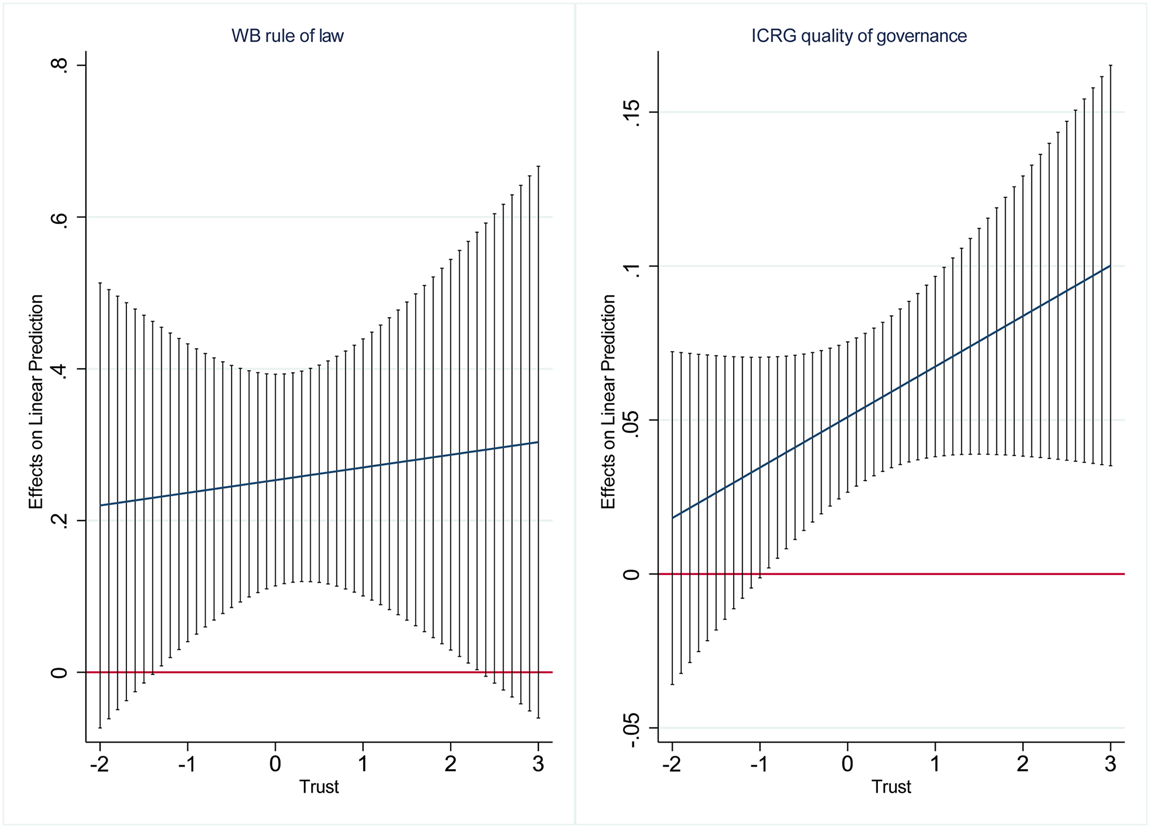

Figure 4 shows the marginal effects of legitimacy conditioned on trust levels. Both rule of law and quality of governance variables show that the marginal effect of legitimacy is positive and statistically significant. However, the results differ across rule of law and quality of governance variables. For the rule of law, the marginal effect of legitimacy on governance is statistically significant only when −1 < Trust < 2, indicating that legitimacy increases governance only when a country has some trust level to complement it. At a lower level of trust, Trust < −1, legitimacy has no statistically significant conditional effect on governance. After a certain threshold, i.e. Trust > −1, trust level becomes vital in increasing the governance if legitimacy level improves.

Figure 4. Interaction effect of trust and legitimacy on governance.

Our intuition behind these findings is based on the idea that trust in government along with confidence in institutions moulds legitimacy (Hutchison, Reference Hutchison2011). Thus, some level of trust is needed to affect political legitimacy, which enhances governance. Conversely, a low level of trust (social capital) may fail to enhance political legitimacy and improve superior government services (Myeong and Seo, Reference Myeong and Seo2016). However, this effect becomes statistically insignificant at a higher level of trust again. At a high level of trust, political legitimacy loses its positive effect on governance. Our intuition behind this insignificant effect is that at a high level of trust the gain from political legitimacy diminishes. At a high level of trust society has already exhausted the positive effect of political legitimacy.

For the quality of governance, the marginal effect of legitimacy on governance is statistically significant after Trust > −1, indicating that legitimacy increases governance only when a country has some trust level to complement it. At a lower level of trust, Trust < −1, legitimacy has no statistically significant conditional effect on governance. After a certain threshold, i.e. Trust > −1, trust level becomes vital in increasing the governance if legitimacy level improves.

We hypothesize that political legitimacy positively affects governance across countries. Our benchmark results and robustness tests support this hypothesis. Furthermore, our findings reveal that trust plays a mediating role between political legitimacy and governance. Therefore, we conclude that political legitimacy has a positive and statistically significant effect on governance, and trust mediates this effect.

Conclusion

This paper argues that a lack of political legitimacy affects a state's ability to govern efficiently. In sharp contrast to Holcombe (Reference Holcombe2021) contractarian theory arguing the negative effect of legitimacy on governance, we hypothesize the positive and statistically significant effect of legitimacy on governance. We use cross-sectional data from 66 countries to investigate the link between legitimacy and governance empirically. We employ OLS, instrumental variables and Lewbel's instrumental variable methods to examine this relationship. The results indicate that political legitimacy, indeed, has a positive and statistically significant effect on governance. Moreover, we provide evidence of an interaction effect between trust and political legitimacy on governance.

Although we are the first to establish a statistical relationship between political legitimacy and governance, our study has limitations and room for expansion. First, it may be challenging to improve political legitimacy. Therefore, improving legitimacy and, consequently, improving governance may be complex. Second, we used cross-sectional data to investigate the relationship between legitimacy and governance, restricting our ability to establish causality adequately or track changes over time. We opted for a cross-sectional analysis due to the availability of legitimacy data, which is only available across countries and not over time. Future studies may benefit from using panel data analysis to control for unobserved country-level differences and monitor changes in legitimacy over time. Third, future studies may find it worthwhile to apply other alternative methods, such as modern matching and synthetic control techniques, to offer robust causal insights. Fourth, the data for political legitimacy are available only for 72 countries; a broader sample size may capture more variation in the data. Fifth, future research could link governance to political legitimacy based on the stages of economic development. Finally, the impact of legitimacy on governance may depend on factors such as financial inclusion, media freedom, and human rights across countries. We leave these crucial questions for future researchers to address.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137423000334.