Introduction

In 2020, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Global Network for Age-friendly Cities and Communities (GNAFCC) comprised over 1,000 cities and communities in 41 countries, with a combined population of over 240 million people (Age-friendly World, 2020). Because of its global reach, a critical question regarding the initiative concerns the degree to which its conceptualisation of age-friendliness is relevant in diverse geographical and cultural contexts. To date, this question has received limited attention in the growing body of research on age-friendly communities. Against this background, this article explores the application of the WHO age-friendly concept in the development of an age-friendly county (AFC) programme in Ireland. In 2019, Ireland became the first country in which all local government areas were recognised as members of GNAFCC.

Developing urban, and more recently, rural age-friendly communities has become a major issue for public policy making and research. The major drivers of this development are rapid global population ageing and the impact of accelerated urbanisation (WHO, 2007; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Angel and Setterson2011). Accompanying these global trends, environmental gerontology has provided comprehensive evidence of the impact of person–place relations on older people's quality of life (e.g. Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Smith, Reference Smith2009; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Angel and Setterson2011; Warburton et al., Reference Warburton, Scharf and Walsh2017), and there has been the parallel adoption of ‘ageing in place’ as a social policy goal in many countries (Lui et al., Reference Lui, Everingham, Warburton, Cuthill and Bartlett2009). Influenced by these demographic, policy and research developments, numerous initiatives have emerged aimed at enhancing the relationship between people and place to make them more ‘age-friendly’ (Lui et al., Reference Lui, Everingham, Warburton, Cuthill and Bartlett2009; Moulaert and Garon, Reference Moulaert and Garon2016). The most influential at global level is the WHO age-friendly cities and communities programme (WHO, 2007, 2015, 2018). Launched in 2006 as the WHO Global Age-friendly Cities project, this policy defines an age-friendly city as one that promotes and ‘encourages’ active ageing, defined in the WHO active ageing policy framework as ‘the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age’ (WHO, 2002: 12). The policy emphasises the role of local government in promoting active ageing, and presents planning guidelines for intervention across eight domains: outdoor spaces and buildings; housing; transportation; respect and inclusion; social participation; civic participation and employment; communication and information; and community supports and health services (WHO, 2007). In order to promote utilisation of the guidelines and support implementation of age-friendly programmes, the WHO established the GNAFCC in 2010.

Current research on age-friendly initiatives is extensive and falls into three main categories: research that focuses on programme implementation; research which interrogates age-friendly policy in the context of later-life social exclusion; and research that focuses on the relationship between age-friendly policy and macro-level issues such as economic austerity, globalisation and migration. The first of these strands is mainly descriptive and details implementation milestones and achievements, highlights implementation facilitators and challenges, and is concerned mainly with urban settings (e.g. Moulaert and Garon, Reference Moulaert and Garon2016; Stafford, Reference Stafford2019). It has identified a range of factors which can support and/or act as barriers to the development of age-friendly initiatives, including inter-agency collaboration (De La Torre and Neal, Reference De La Torre, Neal, Caro and Fitzgerald2016; Garon et al., Reference Garon, Paris, La Liberté, Veil, Beaulieu, Caro and Fitzgerald2016), political leadership and local programme co-ordination (Menec et al., Reference Menec, Novek, Veselyuk and McArthur2014; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Scharf, Walsh, Buffel, Handler and Phillipson2018), funding and resourcing (Shannon and O'Connor, Reference Shannon, O'Connor, Caro and Fitzgerald2016), public policy environments (Brasher and Winterton, Reference Brasher, Winterton, Moulaert and Garon2016), and programme monitoring and evaluation (Golant, Reference Golant2014). As a result, we now have a greater understanding of the relative importance of these factors, and the processes whereby they intersect and influence age-friendly policy implementation in diverse geographical contexts (Menec and Brown, Reference Menec and Brown2018). This strand of research has paid little attention to the theoretical and conceptual basis of the WHO approach, and the critical connections that may exist between these conceptual underpinnings and programme implementation.

The second research strand builds on long-standing research interest in neighbourhoods and later-life social exclusion (e.g. Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2003, Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Burns et al., Reference Burns, Lavoie and Rose2012). It has expanded on the nature of spatial and place-based features of exclusion, the role of urban and rural community contexts in mediating exclusionary outcomes, and the potential of age-friendly policy to bolster the protective role of place in these processes and combat exclusion directly stemming from dimensions of place (Walsh et al., Reference Walsh, O'Shea, Scharf and Shucksmith2014, Reference Walsh, Scharf and Keating2017; Walsh, Reference Walsh, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018; Urbaniak and Walsh, Reference Urbaniak and Walsh2019). Linked to this work, research has advanced a theoretical place-based model of exclusion to examine critically the conceptual basis of the WHO age-friendly policy (Moulaert et al., Reference Moulaert, Wanka and Drilling2017), and has identified benefits derived from connecting age-friendly policy to the goal of reducing social exclusion of older people (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Rémillard-Boilard, Walsh, McDonald, Smetcoren and De Donder2020). In addition, research with a spatial exclusion focus has highlighted issues critical to age-friendly policy development (Vidovićová and Tournier, Reference Vidovićová and Tournier2020), and examined how policy can inadvertently contribute to exclusion through displacement of scarce resources (Golant, Reference Golant2014). Much of the focus of this strand of research has been on disadvantaged urban communities.

The third category of research has examined a broad range of issues, including the role of older people in governance and policy implementation (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012; Scharlach and Lehning, Reference Scharlach and Lehning2016), and the level of community capacity required to accommodate the development of age-friendly programmes (Golant, Reference Golant2014). It has explored the impact of economic austerity measures on the implementation of policy (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, McGarry, Phillipson, De Donder, Dury, De Witte, Smetcoren and Verté2014; Walsh, Reference Walsh, Walsh, Carney and Ní Léime2015), and the need for age-friendly policies to be inclusive of more diverse experiences of ageing resulting from globalisation and increased international migration (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Scharf and Keating2012). Critically, this research has begun to examine the ability of the WHO policy to accommodate the heterogeneity of older people's experience of place (e.g. Eales et al., Reference Eales, Keefe, Keating and Keating2008; Peace et al., Reference Peace, Katz, Holland, Jones, Buffel, Handler and Phillipson2018), including the transferability of the policy to rural communities (Menec et al., Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011; Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales and Phillips2013). While this has extended the scope of enquiry beyond large urban contexts, little of this research has examined the application of age-friendly policy in smaller urban communities. This settlement type is particularly important in Ireland where almost 46 per cent of urban dwellers and 31 per cent of the total population live in towns rather than in larger urban or rural settings (Central Statistics Office, 2012).

Despite these advances in age-friendly research, there are still significant research gaps related to policy transfer and implementation. Much of the attention on older adults in age-friendly research and discourse has centred on the role of older people in programme development. However, while there has been extensive research on older adults’ experience of ageing and place in environmental gerontology, and some discussion on the implications of this for age-friendly programming, there has been little empirical investigation of the daily routines and person–place relations of older people living in planned ‘age-friendly’ communities, as a programme unfolds. As a result, there is limited critical assessment of how the WHO policy conceptual framework and associated action plans capture and reflect this experience. Consequently, this article aims to explore the extent to which the WHO age-friendly policy conceptualisation, and the strategy developed utilising this framework, reflect the experience of ageing and place of a group of older Irish adults living in two small urban communities that are satellite towns of Dublin city. The focus of the study is on an empirically rich exploration of these lived experiences within a specific locational context, rather than on ensuring any form of generalisability of findings to other settings. The towns are located in Fingal county, which has developed an AFC programme affiliated to the national age-friendly initiative.

Approach and methods

To explore how the WHO's conceptualisation of an age-friendly community reflects experiences of ageing in place for older adults in the study, the research adopted a qualitative case study design. This facilitated an in-depth exploration of a real-world phenomenon (i.e. older adults’ experience of living in small, planned age-friendly urban communities), where the contextual conditions were highly relevant (i.e. a local AFC strategy was developed and implemented as part of a national/international initiative), and multiple sources of evidence were available to provide a clear account of the case in question (Yin, Reference Yin2009; Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg, Denzin and Lincoln2011). In addition, Fingal's AFC programme suited a case study approach as it provided a defined unit of analysis, had identifiable geographic and administrative boundaries, and provided an appropriate context within which to explore our interest in the transferability of the WHO age-friendly policy (Punch, Reference Punch1998). Data for the case study were collected from multiple sources including documentary evidence, site observation (including three site visits accompanied by members of a Reference Panel of older adults established to support and advise on the research) and qualitative interviews: 14 initial interviews with older adults in 2014 and six follow-up interviews in 2016; and 16 interviews with programme development stakeholders involved at local, national and international levels (see Figure 1). Only data from the 20 older adult interviews are presented in this article. While stakeholder perspectives help to contextualise this analysis, and frame the relationship between older adults’ experience of ageing and the development of the age-friendly programme, they are described in detail elsewhere (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Scharf, Walsh, Buffel, Handler and Phillipson2018).

Figure 1. Phases of the fieldwork.

Study sites

Older adults in the study resided in two towns in Fingal – Swords and Skerries – selected because of their different spatial characteristics, population size and history of development (see Table 1). Fingal county is located on Ireland's east coast, north of Dublin city. It has a population of 296,214, and is the third most populous local authority area and the ‘youngest’ county in Ireland – 7 per cent of the county's population is aged 65 years or over compared to 13.4 per cent nationally (Central Statistics Office, 2017). Over 90 per cent of the population live in urban areas, varying in size from densely populated suburbs to the north-west of Dublin city, to county towns, such as Swords and Skerries. Fingal has a diverse and growing local economy due to its proximity to Dublin city, and has a well-developed road and rail infrastructure. Despite the impact of the global financial crisis of 2008, Fingal's unemployment rates are among the lowest in Ireland. The county also has a higher proportion than the state average of workers classified as professional, managerial and technical, and the second highest share of professionals among all counties nationwide (Fingal County Council, 2015).

Table 1. Case study locations

Fingal's AFC programme

Fingal's AFC programme, established in 2011, is typical of other Irish age-friendly initiatives. It was developed at a time of extreme economic austerity, and has a similar organisational structure, including an inter-agency oversight group (the Age-friendly Alliance) and a local Older People's Council which has representation on the Alliance. The programme made extensive use of the WHO age-friendly framework to develop its first five-year strategy (Fingal County Council, 2012) which proposed 58 actions across the eight WHO domains (Table 2). The strategy focused strongly on actions related to ‘respect, social inclusion and social participation’ (16 actions) and ‘civic participation and employment’ (ten actions), with the remaining actions spread evenly across the other six WHO domains. The programme can be considered progressive in terms of its governance capacity-building measures, formal external review of implementation and active leadership role in national age-friendly initiatives. In 2018, the county developed a second five-year age-friendly strategy (Fingal County Council, 2018).

Table 2. Summary of proposed actions from the Fingal Age-friendly County Strategy 2012–2017

Source: Fingal County Council (2012).

Sampling and recruitment of participants

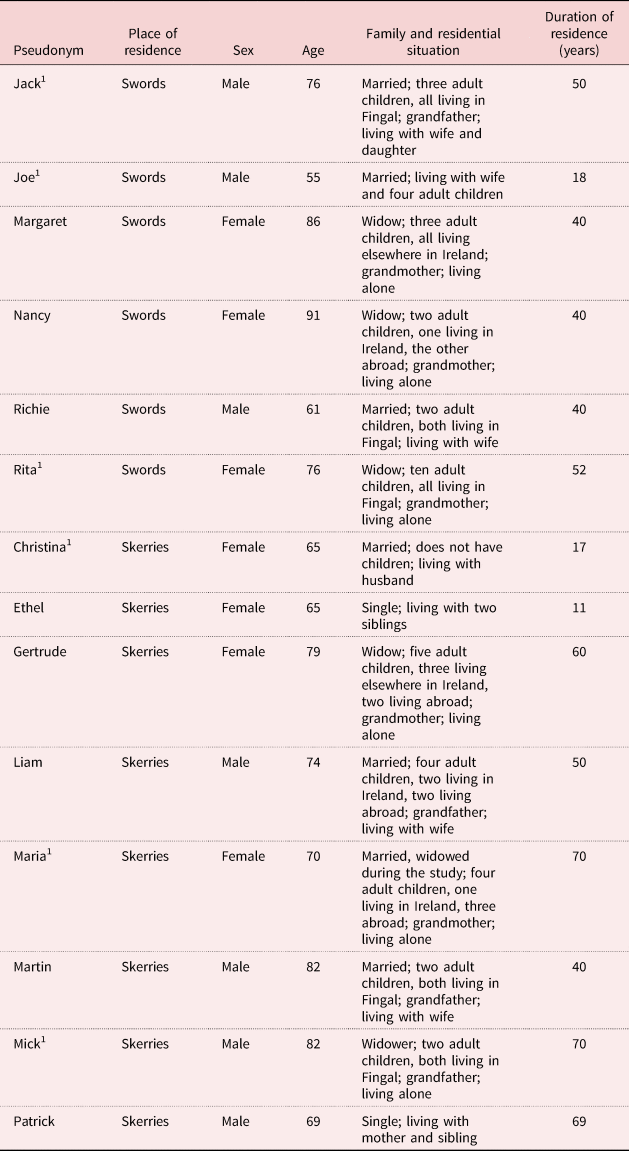

Purposive sampling was used to identify a sufficiently diverse population of older adults for the study, with theoretical sampling used to identify participants from the initial sample for follow-up interview. Recruitment considerations included: place of residence, sex, age, living arrangements and duration of residency (Table 3). The sample comprised seven men and seven women aged 55–91 years (mean age 74 years), with four aged 80 and over. Seven participants were married, five widowed and two were single. Six lived alone, and 11 had migrated into these communities, including two foreign nationals. Recruitment was conducted with assistance from members of the Reference Panel and a range of community gatekeepers. The selection of participants for follow-up interview was based on significant thematic areas identified during analysis of the initial interviews. This follow-up sample reflected a mix of men and women, participants from both towns, and native and non-native residents.

Table 3. Participant characteristics

Note: 1. Participated in follow-up interviews.

Older adult interviews

Intensive interviews were conducted in 2014–2015 with the 14 participants to explore their daily lived experience in the two towns, beginning three years following the establishment of the AFC programme. Interviews allowed for an in-depth exploration of implicit views and assumptions, meanings and perceptions, as well as accounts of actions (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, Reference Charmaz2014; Conlon et al., Reference Conlon, Carney, Timonen and Scharf2015; Timonen et al., Reference Timonen, Foley and Conlon2018). Areas explored in the interviews, informed by previous research in environmental gerontology, included: person–place relations and the physical and social environment; community supports and service provision; belonging and identity; and knowledge and awareness of the Fingal AFC programme. Interview duration varied from 54 to 98 minutes, with a mean length of 79 minutes.

Six of the initial interviews were walking interviews. These help contextualise understanding of local knowledge, provide insight into the physical and social context of the lives of participants in a particular place, and facilitate exploration of the ways in which people engage with their environment (Kusenbach, Reference Kusenbach2003). They also harness the experience of place as a trigger to prompt knowledge production, and elicit information that might not be available through conventional interview (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Eisenberg, Frerich, Lechner and Lust2009). The interview schedule was informed by the topic areas covered in the intensive interviews but was led much more by the participant than the researcher. This allowed participants to introduce topics, memories, perceptions, reflections and experiences as these occurred to them, sometimes prompted by aspects of the physical and social environment experienced on the walk. All walking interviews commenced and ended at the participant's home. Interview duration varied from 60 to 80 minutes, with a mean length of 66 minutes.

The interview schedule for the follow-up interviews in 2016 was tailored for each of the six participants, based on the significance in their lives of six key categories identified through analysis of initial interviews: attachment, belonging and identity; social relations; creative activities and pursuits; health and wellbeing; civic engagement; and using and shaping the physical environment (including safety). Situational change since the initial interview was also elicited. Most follow-up interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, with interview length varying from 35 to 65 minutes, and a mean interview length of 55 minutes.

Other forms of data collection

To construct site and age-friendly programme profiles, the research drew on supplementary material including local government and health and social service reports, census material, age-friendly strategies and review reports, local community websites, minutes of age-friendly oversight committee meetings and archive material. Data also included field notes arising from site visits with members of the Reference Panel and walking interviews with participants, photographs taken by the lead researcher and charting of community space in both towns.

Data analysis and ethics

A constructivist grounded theory approach was used to analyse interview data (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, Reference Charmaz2014). All interviews were conducted in English, recorded and transcribed. From an initial reading of transcripts, inductive codes were identified. Categories were developed through clustering of codes and ongoing memo writing and research team discussion. New data from the follow-up interviews were used to further inform categories and their properties, and Reference Panel members assisted in refining emerging categories. Data analysis facilitated the development of a framework of distinct but intersecting categories which helped capture the complexity of study participants’ lived experience. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the research team's institution.

Findings

Data analysis identified four major dimensions of later-life person–place relations particularly relevant to the application of the WHO concept of age-friendliness in programme development: place attachment; social relations; social participation and civic engagement; and use of the physical–spatial and service environment. In addition, the research assessed participants’ awareness of and interest in the local AFC programme. This section examines each of these dimensions and participants’ perspective on the programme, and explores how they are reflected in Fingal's age-friendly strategy.

Place attachment

The findings provided insight into the complex, multi-dimensional nature of place attachment in smaller urban communities. Place attachment is defined by Rowles (Reference Rowles1978, Reference Rowles1983) as a range of subjective processes operating when people form emotional, social and behavioural bonds with their environment, and become attached to place. Participants reported a dynamic and diverse range of experience of place attachment. Some had strong, positive attachment bonds with the towns, which were sometimes linked to their native connections to these areas:

I was born in a house called [house name] in Skerries another 100 yards down the road. So I was actually born in Skerries; I didn't have to go to the hospital or anything … I was born in the house, so I reckon I'm a true Skerries person. (Patrick, 69 years)

Others demonstrated a more neutral, uncommitted form of attachment:

I wouldn't be attached to anything you know. I wouldn't be attached to [my place of origin] either, just that all my family came from [there] … No. Both of them [my place of origin and this town] are ok. I wouldn't, I really don't have to think about it. It's natural for me just to live here. (Martin, 82 years)

A small number of participants expressed extremely negative feelings of dislocation and alienation from place. One recently bereaved participant, who reported feeling severely lonely and overwhelmed by the pace of change in the town, commented:

Older people are treated as ‘non-persons’ … ten years ago I identified with this town … now I no longer belong here … it means nothing to me now. (Margaret, 86 years)

Such comments echo previous research on place attachment in rural and urban locations. This found that place attachment was dynamic, varied among participants, and was influenced by the intersection of multiple factors including major lifecourse transitions and events (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2005; Keating, Reference Keating and Keating2008; Smith, Reference Smith2009).

For many study participants, place attachment was important for self-identity. For the three native participants, place attachment often had strong temporal and intergenerational dimensions, interwoven with a rich web of associations and memories of lifecourse events and experiences that often went back to childhood. Many non-native participants’ attachment to place was significantly shaped by the experience of having lived elsewhere. This gave these participants a comparative framework that could lead to feelings of multiple place attachment. For example, two participants, one originally from Dublin city and the other from Galway, still identified themselves as being ‘a city girl’ and ‘a west of Ireland man’ despite living in Fingal for 52 and 44 years, respectively. A Canadian living in Ireland for 17 years referenced the need to ‘juggle’ two place-based identities:

It's hard to believe, it is so hard to believe you know that the years have gone by … I live here in Ireland, I'm from Ireland … yeah I'm, it is home. But for me where you were born will always be ‘home home’. (Christina, 65 years)

Research has shown that place attachment is important in the development of self-identity, as older adults integrate personal and social meaning, and personal history, with geographical location to achieve feelings of being ‘in place’ rather than ‘out of place’ (Rowles, Reference Rowles1983, Reference Rowles, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018; Peace et al., Reference Peace, Holland and Kellaher2006). Research has also shown that first-generation migrants often express emotional attachments to their place of origin as well as to their immediate neighbourhood (Gardner, Reference Gardner2006; Buffel, Reference Buffel2017), as in the current study, and international migrants can often successfully negotiate multiple place attachments (Gustafson, Reference Gustafson2001).

When expressing experiences of place attachment, some participants focused on the social environment, while others stressed elements of the physical–spatial and service environment. However, for many it was a blend of both that accounted for the bond with place:

I think it's a combination of the sea and the way the town is laid out … it's kind of like a little circle. And the people are very nice, and there's really lots that goes on in this town for activities if you want [to be involved] … So, there's badminton, there's tennis, there's film societies, there's bridge, anything you want. (Christina, 65 years)

Place attachment also played a central role in relocation decision-making. Participants contemplating relocation had all strong positive feelings of attachment to place, and restricted relocation options to alternative neighbourhoods and estates within their current town of residence.

Many of the proposed actions in the age-friendly strategy have the potential to impact positively on place attachment, although place attachment is not addressed explicitly in any action, other than in one that recognises older people as place ‘experts’/‘cognoscenti of place’. Significantly, migrants’ experience of place is not reflected in any action, and place attachment is not addressed in any of the actions related to housing. This is despite evidence in this study, and in a substantial body of research literature, that place attachment can play a significant role in relocation decision-making (e.g. Löfqvist et al., Reference Löfqvist, Granbom, Himmelsbach, Iwarsson, Oswald and Haak2013).

Social relations

There is evidence in the current study that specific place dimensions impacted on participants’ development of key social relations with family members and neighbours. These could be significant for the development of age-friendly communities. For example, the study confirms the influence of geographical proximity on opportunities for interaction with family members, including intergenerational contact:

Ah yeah [I have family living locally]. That's, that's a big plus. I think if you hadn't got family, well if you hadn't got family, I wouldn't be here. I'd be off, I'd be away foreign somewhere. (Mick, 82 years)

The study also illustrates how spatial proximity influenced the support and care-giving dimensions of family relations, an issue seldom focused on in previous age-friendly research. Participants reported receiving emotional support from adult children, particularly at critical times such as bereavement and serious illness, and this type of support was not necessarily contingent on proximity. However, practical support with household tasks was heavily dependent on close proximity, and this instrumental support enhanced participants’ capacity for independence and ageing in place. Participants also reported providing emotional and practical support to spouses, surviving parents, siblings and adult children, including caring for grandchildren. Living in proximity to family members was an important factor in facilitating care-giving, and in some cases influenced whether participants provided support on a part-time or full-time basis.

The findings also support previous research which demonstrates that residential stability can lead to a strong sense of belonging to neighbourhood, and that resultant neighbourhood relationships are an important community resource for older adults (Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Bernard, Phillips and Ogg1999; Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson and Smith2003). The relative stability of the neighbourhoods in which participants resided supported continuity in relations with neighbours:

Now we are [lucky] because you know they're there if you need them. And they know you're here if they need you. So, like everyone, everyone looks out for one another. So, it's good … a good relationship. (Rita, 76 years)

The sense of continuity in these relationships may be related to the length of time participants have lived in the two towns, often in the same estate. The mean length of residence for participants was 45 years, and almost half the participants lived in the same house for the full length of time they had resided in the towns. In the current study, instrumental support from neighbours was particularly important for older adults living alone without proximate family support. Relations with neighbours can also evolve into friendship relations which give rise to more extensive social networks, strengthen place attachment, and contribute to a sense of wellbeing and belonging (Young et al., Reference Young, Russell and Powers2004; Walker and Hiller, Reference Walker and Hiller2007).

Aspects of place can also lead to challenges in developing social relations. For example, a foreign-born participant encountered what she perceived to be different cultural norms of relationship formation:

In my country, on the whole, people are much more open [than Irish people] about themselves right from the start … Irish people will say: ‘hello, how are you?’… they invited you for coffee, you met everybody which was very lovely. But if you want a deeper relationship, it takes a long time. That was my experience. (Christina, 65 years)

The findings also suggested that lifecourse transitions can have a profound effect on the social relationships of participants and their relationship with place. This is particularly significant in the case of bereavement, but is also important with regard to other major lifecourse experiences and patterns, including marriage, parenthood and grandparenthood, working lives that involved shift work and weekend commitments, retirement and changing patterns of family care-giving.

The social relations dimension of older adults’ lives is given little or no recognition in the AFC strategy. The significance of family relations, and especially the care-giving aspect of these relations, is not addressed in the proposed actions, and the importance of ongoing relations with neighbours is framed minimally, and limited to providing support in times of ‘bad weather’.

Social participation and civic engagement

The findings highlighted the importance of social participation and civic engagement in the formulation of person–place relations. Participants engaged in the social life of the two towns through daily activities while out-and-about, and the pursuit of personal interests and hobbies through various local organised group activities. Many of these everyday activities provided opportunities for social interaction:

But eh as I was telling you earlier, I like going down to the Pavilions [shopping centre] and walking around and browsing and that, you know … just strolling around, and looking, and meeting maybe someone and having a chat and all this you know. (Jack, 76 years old)

There were some differences in the pattern of activity between male and female participants related to the use of space. While both men and women went shopping and for walks, female participants were more likely to go walking with friends and male participants were more likely to take the dog for a walk. Participants belonged to a wide range of organised groups and clubs in the two towns. Most of the activities that participants engaged in were locally based, particularly those of a group nature. However, a number of participants travelled to other towns in the county or to Dublin city for specific cultural and recreational activities. This was often because facilities were not available locally – e.g. one town does not have a cinema and neither town has a theatre – or to access major exhibitions and performances that are only available in the city. Participants also used Dublin city as a convenient venue for meeting friends:

…myself and the wife go in [to Dublin city] quite a lot. I actually, I've a friend that comes home from England and we meet maybe once every three months in town for a few drinks … He stays in the city when he comes home and we meet half way like, and we go for a few jars and things like that. (Richie, 61 years)

The level of activity among participants varied greatly. For a few people shopping now provided the main opportunity for regular social participation outside the home. At the other extreme, one participant described a daily routine with high levels of social interaction across a broad range of public spaces:

Well, a typical day would, now I'm not religious, but I go to 10 o'clock Mass. And then I probably go swimming and then it's usually, well some days it's Active Retirement. And some days it used to be [caring for] my grandson. And the other day I'd do a day trip on my free travel pass. (Maria, 70 years)

Many participants engaged actively in cultural and creative activities, such as music-making, painting, craftwork, dance, drama and creative writing, some of which had a social dimension. One participant explained the importance of these activities:

I'm an artist and I write poetry and I'm involved in crafts as well … and I knit … oh absolutely [these activities are important to me]. I mean I wouldn't want to get out of bed in the morning but for those sorts of things. (Margaret, 86 years)

This involvement provided opportunities for enjoyment, self-expression, learning and social interaction. Some participants’ sense of self-identity and their place-making and relationships with the social and physical environment were significantly influenced by their creative abilities. Involvement in creative activities enabled several participants to negotiate and mark different identities which were related to place, and also to critique the place in which they lived and their relationship with place. This place-related aspect of social participation is important from an age-friendly perspective. Previous research has shown that where creative activities have a community focus, they can create opportunities for social interaction and help construct a sense of identity and belonging (Murray and Crummett, Reference Murray and Crummett2010).

Many participants were also involved in volunteering and civic engagement activities. The forms of civic engagement varied greatly, were mainly locally based, and ranged from volunteering on an ongoing basis in local charity, church and community groups, to fundraising for specific purposes, or one-off campaigning for new cultural initiatives in the community. One participant described his commitment as a volunteer driver with a local Meals-on-Wheel's service:

I do Meals-on-Wheels, and that's a couple of times a week … The average route takes about an hour … and then with the to-ing and fro-ing and all you're back, you're back and all finished and all wrapped up say in about an hour and a half to two max. (Joe, 55 years)

Some participants reported that engagement in the civic life of the town had allowed them to participate actively in community projects in their neighbourhoods, and develop skills relevant to place-making and community development:

I was involved there on the estate committee in earlier years. We won the Tidy District Awards for Fingal County Council on seven occasions for the smallest estate. I was involved on the committee there; I was secretary and treasurer, chairperson through the years. (Richie, 61 years)

Several participants reported that involvement in civic engagement activities had helped them integrate into the local community and develop a sense of being ‘in place’. Civic engagement could also sensitise participants to the politics of community development, and inter-group competition related to the allocation of public resources and the determination of spheres of interest:

And we try to help where we can. We do have [a home visitation programme] of sorts from the parish itself yeah … Well, we try, we try not to get involved, well we try not to [take] over – what's the word I'm using here? … I wouldn't say there are problems, but you just have to be mindful of, sensitive, sensitive [to the work of other initiatives]. (Ethel, mid-sixties)

Health and mobility problems could have a significant adverse impact on participants’ involvement in civic engagement activities:

Well, I'm not so connected now because I'm not active … I think it's because I can't move around. Like you know … I'm waiting on an operation on my back. (Gertrude, 79 years)

The age-friendly strategy has a number of proposed actions which could potentially improve the social participation and civic engagement of older people in the study. The strategy also proposes to develop a best practice model to improve older people's participation in democratic processes at local level, and capacity-building measures to encourage increased volunteering. However, while the strategy has a strong focus on the cultural aspects of participation, most of the proposed actions assume a mainly consumption model of cultural participation, and fail to capture and support the important active and identity-related aspects of cultural activity identified in the study.

Use of the physical–spatial environment and service infrastructure

For most participants, the experience of the physical–spatial environment and service infrastructure was positive. Different aspects of the environment contributed in each town. Participants in Skerries highlighted the seaside location and the promenade, and recent environmental and retail developments in the town centre which they reported had maintained and enhanced services and amenities. In Swords, participants reported that the recent development of a new shopping mall and the availability of local public parks added to the quality of daily living. In both towns, participants referenced proximity and ease of access to Dublin city and other local towns, and architectural and heritage features as important dimensions of place. Research has shown how local facilities such as those available in these towns become embedded in older people's routines (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2008; Burns et al., Reference Burns, Lavoie and Rose2012). Previous research also confirms the ‘therapeutic’ effect of green and blue environments, and their positive impact on older people's sense of wellbeing, quality of life and health-related behaviours such as walking (Peace et al., Reference Peace, Holland and Kellaher2006; Handler, Reference Handler2014; van Dijk et al., Reference van Dijk, Cramm, van Exel and Nieboer2015).

Participants reported that both towns are serviced by good transportation systems which facilitate access to services, including those located in nearby towns and in Dublin city. The availability of affordable and accessible transportation is a critical attribute of place for older people. It can enable access to essential facilities and services, facilitate community participation, help maintain independence, and support social inclusion and connections with family and friends (Peace et al., Reference Peace, Wahl, Mollenkopf, Oswald, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007; Handler, Reference Handler2014). Access to both private and public transport is associated with higher quality of life (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Hamilton, O'Neil, Gow, Webster and Pike2002), and usage of public transport depends on location and the quality of the service (Peace et al., Reference Peace, Wahl, Mollenkopf, Oswald, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007). Many participants reported using the free travel card to go shopping, to meet friends and to attend cultural events. Research has shown that concessionary travel on public transport systems enables older people to engage in a wide range of pursuits that enhance wellbeing (Hirst and Harrop, Reference Hirst and Harrop2011).

The physical–spatial environment presented significant challenges for some participants who lacked access to a car, particularly those currently experiencing health problems which impaired mobility. In addition, uneven footpaths, the hilly topography and increased traffic volumes intensified these difficulties for several participants:

I find here now that I am old, I find it very out of the way really … it's a chore to get to the shops and particularly I don't drive and I've lost my husband, you know so I find that very difficult … Walking to the village is a chore because of the hill … also the narrow footpath and the volume of traffic. (Margaret, 86 years)

Not surprisingly, as demonstrated in previous research (Wennberg et al., Reference Wennberg, Ståhl and Hydén2009; Handler, Reference Handler2014), physical barriers such as kerbside height or degree of clutter on footpaths impacted more adversely on the oldest old, and older participants who had functional limitations or who used mobility devices.

Concerns about personal safety restricted the use of physical–spatial environment and service infrastructure in both towns, but participants reported that these challenges were manageable and they had taken what they viewed as reasonable measures to deal with them. These included restricting their use of public space in terms of location and time:

I feel I wouldn't feel safe anywhere [in Swords] at night. There's no use saying one thing and thinking another. I don't go out [at night], I'm brought out. If I go down to play bridge, I'm brought down. (Nancy, 91 years)

Previous research has shown that neighbourhood usability is influenced by older people's perceptions of ‘orderliness-related issues’, and in particular by perceptions regarding neighbourhood security (Peace et al., Reference Peace, Wahl, Mollenkopf, Oswald, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007; Wennberg et al., Reference Wennberg, Ståhl and Hydén2009; van Dijk et al., Reference van Dijk, Cramm, van Exel and Nieboer2015). The experience of crime or the fear of being a victim of crime can inhibit use of public space, and older people may be less likely to leave their homes after dark, or indeed be afraid to visit certain parts of neighbourhoods, such as parks and cemeteries, during daylight hours (Scharf et al., Reference Scharf, Phillipson, Smith and Kingston2002; Smith, Reference Smith2009; Phillipson, Reference Phillipson, Angel and Setterson2011).

Most participants reported using local primary health-care services and, in the main, were positive about the quality and availability of services provided by general practitioners, pharmacists and dentists in the two towns. A number of participants had also utilised various community health and social care services, and reported that these can make the difference between continuing to live in the community or moving to live in supported residential settings. However, not all participants had positive experiences of these services:

I was cut an hour. I had her [the home help] for three, three days a week and they've cut us down in the past year … It seems to be very slow between the, the nurses in the town … if you want to get them to come up and visit … they're very slow to respond. (Gertrude, 79 years)

A number of participants believed that national financial austerity measures have caused this deterioration in community health and social care service provision:

Yeah, and it's [the Health Centre] a fine building and doing well and you know. I think funds is always a problem … Cut this and cut that and everything you know, and I mean there's not really anything the staff can do. That's depending on this old government of ours. (Joe, 55 years)

On balance, participants in Skerries were more positive about developments in the physical–spatial environment than those in Swords. This may be related to the different scale of development in the two towns. There is limited evidence in the study that participants in either town feel they have played a significant role in the decision-making processes that have led to these major environmental developments. This may account in part for the concerns and regrets expressed by many participants concerning a loss of perceived ‘community spirit’ in both towns.

The age-friendly strategy has many proposed actions related to outdoor space and the built environment. These are diverse in type and scale, and are integrated across a number of strategy domains. They range from the provision of improved street furniture and age-friendly signage, to a county-wide audit of transportation, and the establishment of an age-friendly town project in Skerries. In addition, a number of proposed actions address personal security and safety, including road safety. However, actions related to health and wellbeing focus primarily on health promotion measures rather than on improving the provision of existing health and social care services.

Awareness of the Fingal age-friendly programme

Surprisingly, many participants were unaware of Fingal's AFC programme. Eight participants had no knowledge of the programme; five had some limited knowledge of particular elements of the programme; and just one had actively participated in the age-friendly town project in Skerries. Although the programme was in early development stage, this raises serious concerns about communications and the effectiveness of the structures developed to involve older adults in its development. This is especially so in light of previous research regarding the critical role older people can play in age-friendly initiatives (e.g. Lui et al., Reference Lui, Everingham, Warburton, Cuthill and Bartlett2009; Buffel, Reference Buffel2015, Reference Buffel2018). Despite the proposed actions in the strategy related to communications, awareness levels about the programme among participants did not improve over the two-year period of the study.

Despite this low level of awareness, most participants expressed an interest in the programme and had definite views about where its focus should lie. These views were sometimes framed as relating to perceived future needs, or to the needs of participants’ acquaintances. Some issues that were raised, such as formal homecare provision, had already emerged in the course of exploring participants’ experience of daily life in the town. A number of participants raised the issue of personal safety and made suggestions for improvements:

…and feeling safe [is important]. Maybe good policing or community policing services [would help] … it [the Garda station] is manned from time to time now, but I'm not quite sure to what [extent] … But I think they [the Garda] are there, to feel safe, to have, to make, for people to feel safe. [That is one of] the areas to work on. (Ethel, 65 years)

Other issues raised in discussing the programme were new. One participant questioned the provision of suitable housing for older adults in Skerries, and the rising costs for those moving into residential care settings. Another participant, who volunteered in a Senior Citizens’ Centre, was concerned by the impact of new property and water charges:

Yeah, if they're on the state pension like, you can't [pay for services] because now you have the property tax and you have all these things and, like it's very hard … the water rates as well … a lot of them are going to really feel the pinch now, you know. (Rita, 76 years)

Participants were also interested in some general community development issues, including parking facilities at the local train station, and youth employment opportunities:

Yes, I mean in Skerries there are no jobs for young people. That's about the size of it. You know if they want any kind of career job they have to go to Dublin or they have to emigrate you know, or something like that. (Martin, 82 years)

Most of the issues raised by participants in discussing the programme, including personal safety and housing, were actioned in the age-friendly strategy. Although community development issues, such as youth employment, were not dealt with, they were addressed elsewhere in the county development plan. However, two issues, the introduction of new taxes and charges, and the provision of residential care services, although obviously relevant to older people's quality of life, were not addressed in the strategy. Both had economic dimensions, and were adversely impacted by national policy which had imposed cutbacks in public services and the introduction of new taxes in response to the economic crisis of 2008.

Discussion

Drawing upon empirically rich qualitative data collected over a two-year period, the current study echoes previous research and provides strong evidence of the way in which particular places promote wellbeing and place attachment, and impact in significant ways on the activities, social interactions and personal identity of older adults (e.g. Peace et al., Reference Peace, Holland and Kellaher2006, Reference Peace, Wahl, Mollenkopf, Oswald, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007). In addition, the current research, in identifying areas of possible intervention for age-friendly programming, helps us appraise how adequately the WHO age-friendly conceptual framework generates development programmes for small urban communities.

The research identifies many positive aspects of the existing person–place experience of older adults in the study, including: strong place attachment, positive place-based relations with family and neighbours; formal and informal opportunities to participate in the life of the community; extensive place-related intergenerational contact; local opportunities for creative and artistic involvement; and amenities and service infrastructure that, in the main, meet older adults’ preferences and needs. The findings also suggest environment-related challenges that impact negatively on the experience of ageing in place: some non-native participants found it difficult to integrate into smaller communities; informal caring roles could limit opportunities for social participation; inadequate local service provision can impact adversely on the capacity to lead an independent life; lack of involvement in major community planning decisions can lead to feelings of powerlessness and denial of agency in place-making; and bereavement and deteriorating health impact negatively on how older adults experience and use everyday public space.

The findings also provide insight into how various influences operate at different environmental levels to shape person–place relations. For some older adults, personal, micro-level lifecourse fractures and transitions, such as bereavement and ill-health, predominate. For others, meso-environmental dimensions, such as geographical proximity of family and neighbours, the physical–spatial characteristics of the neighbourhood and town, or the adequacy of local facilities and service infrastructure, are significant. For all participants, macro-environmental national public policy led to local service retrenchment and increased residential property charges. These multi-level factors are dynamic in their impact, and intersect and play out differently in the lives of different individuals. This leads to an experience of ageing in place that is diverse, complex and fluid over time.

In reporting these findings, it is also necessary to consider two key limitations of the study. First, as a case study, some of our findings may not be easily generalisable to other age-friendly town settings. There are aspects of ageing in place in Fingal which are unique to the locational context, including proximity to Dublin city and its associated amenities and services. The extent to which the dimensions of ageing in place identified in the study are applicable to other age-friendly sites in Ireland is unclear. Similarly, while the Fingal AFC programme can be considered ‘typical’ in an Irish context in terms of its development and implementation, the unique set of conditions under which the programme was developed (McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Scharf, Walsh, Buffel, Handler and Phillipson2018) also calls into question the extent to which the findings regarding programme development are generalisable to other Irish, and indeed non-Irish, settings.

A second limitation concerns the relatively small number of participants in the study. While the study aimed to present an in-depth account of the lived experiences of older people, and succeeded in including a diverse range of older adults in terms of age, sex, marital status and place of origin, despite extensive attempts to do so, it proved impossible to recruit native participants in one town, or non-native residents who had recently set up home in either of the two towns. The inclusion of these perspectives may have further enriched the analysis of person–place relations presented in the findings. It must also be acknowledged that even though it was valuable to include a diverse range of older adults in the sample, we are not claiming that the findings from these participants are sufficient to represent the views and experiences of these groups within the towns. They do, however, provide insights that can be explored further in future studies.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the research succeeds in explicating the utilisation of the WHO age-friendly conceptual framework in a particular national and local context. In doing so, it raises a number of issues for age-friendly programme policy and practice, and suggests that small urban contexts, in a similar way to disadvantaged urban and remote rural communities, present a number of challenges when applying the WHO framework to develop age-friendly communities. At least three of these require further consideration: first, the ability of the WHO conceptual framework to accommodate diversity of place; second, the implications of the dynamic nature of person–place relations for age-friendly planning; and third, the interplay between age-friendly policy and other public policy which impacts on ageing in place.

On the first point, the WHO conceptual framework (WHO, 2007), because of its multi-domain focus, is a comprehensive planning tool. Its utilisation by the Fingal AFC programme has meant that significant dimensions of older adults’ lived experience that impact on quality of life have been identified. This resulted in the inclusion in the age-friendly strategy of actions which address many significant issues, including interventions that target social participation, transportation, access to services, and the promotion of walking and recreational activities (Fingal County Council, 2012, 2018). However, the current study demonstrates that the WHO framework also has significant conceptual shortcomings, and fails to capture important dimensions of person–place relations in small urban communities. These include the centrality of place attachment, place-based relations with family and neighbours, and active participation in creative activities. Each of these impacts significantly on person–place relations in the current study, and potentially on the capacity to age actively. This conceptual weakness has contributed to a failure to develop interventions in the age-friendly strategy which could have addressed these aspects of older adults’ lives. As such, the current study supports previous research which identified the impact of contextual factors on what it means for a place to be considered age-friendly (Menec et al., Reference Menec, Means, Keating, Parkhurst and Eales2011; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Scharf, Bartlam, Bernard and Sim2014; Menec and Nowicki, Reference Menec and Nowicki2014). It adds to the case for a cautious use of the WHO framework as an age-friendly planning tool in different cultural and geographic settings, and points to the need for a revision of the framework in order to reflect the complex social, cultural and contextual factors which are associated with place diversity.

Second, the current research highlights the dynamic nature of person–place relations, and the ongoing intersection of changing lifecourse and environmental factors which impact on a community's age-friendliness. This interplay means that what makes a place age-friendly for an individual, and for groups of individuals, is continuously evolving and changing. This finding reflects developments in environmental gerontology theory, such as Cutchin's (Reference Cutchin2003, Reference Cutchin2004, Reference Cutchin, Rowles and Bernard2013, Reference Cutchin, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018) concept of ‘place integration’, which emphasises continuous change and the relational unity of person and place. The dynamism inherent in person–place relations has fundamental implications for age-friendly planning, and supports critiques in the age-friendly literature which have raised concerns about the ability of the WHO conceptual framework to capture these relationships (Eales et al., Reference Eales, Keefe, Keating and Keating2008; Smith, Reference Smith2009; Mayhmood and Keating, Reference Mayhmood, Keating, Scharf and Keating2012). Criticism on this issue often focuses on the framework's use of a checklist of ‘static’ age-friendly features. Although this checklist was not used in Fingal, or indeed in other Irish age-friendly sites, the nature of person–place relations which is evident in the current research suggests that the WHO framework will find it difficult to accommodate ongoing change, including change in small urban settings. This has implications for the ways in which older people are involved in age-friendly programming, and indicates, at a minimum, the need for ongoing research and analysis of the needs and lived experience of older adults as an integral part of programme development. One-off consultations are not sufficient to capture the nuances, complexities and evolving nature of older adults’ person–place relations, even in small urban communities. Greater integration of older people in planning age-friendly programmes has become even more urgent as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, because of its impact on person–place relations. Future age-friendly policy will need to prioritise interventions which focus on and strengthen older people's evolving sense of place, belonging and connectedness. This has been affected, and in some cases compromised, by the measures introduced to manage the pandemic.

Third, there is direct evidence in the research of how the transfer of different international policies can impact on the lives of older people in significant ways at local level. National, austerity-driven public policy, introduced in Ireland in response to the 2008 global financial crisis, led to local cutbacks in health and social services for older people. This impacted negatively on the ability to age in place. At the same time, local government age-friendly policy, initiated and promoted by the WHO, aimed to improve the local social, physical and service environment. This led to conflictual policy implementation. For example, while the age-friendly programme initiated a project in Skerries to enhance the walkability of the town, nation-wide health service cutbacks led to lengthening waiting times for community and hospital orthopaedic services. This impacted severely on older adults with mobility problems, and compromised the ability to age in place. This type of policy conflict demonstrates one of the weaknesses of the WHO age-friendly approach, namely its primary focus on micro- and meso-environmental change sponsored and supported by local government. The impact of local programmes can be overridden by more powerful national and international policy measures, and this lack of alignment between different levels of policy can compromise the integrity and credibility of age-friendly initiatives. This points to the need for a more co-ordinated approach at national level to the formulation of policy related to older people, including a comprehensive assessment of the likely impact of new policy initiatives on the implementation of existing policy at local level.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research critically analysed an AFC programme in Ireland which was strongly influenced by the WHO age-friendly approach. The research found that the programme had many positive attributes, and interventions were developed that addressed important and relevant aspects of older people's lives. However, the study also revealed some of the limitations inherent in the WHO approach. The major concern relates to an uncritical transfer and application of the WHO age-friendly conceptual framework as an age-friendly planning tool. This can mean that important dimensions of older adults’ lives, including of those who live in small towns, may be neglected for programme intervention. With the exponential growth in the WHO global network of age-friendly cities and communities since 2010, this is likely to be the case in other cultural and geographic contexts. Given these shortcomings, and in light of the commitment from the WHO that developing age-friendly communities is a priority in its healthy ageing strategy for the next decade (WHO, 2019), research into the factors that impact on the transferability of the WHO age-friendly policy has become ever-more relevant and urgent. Closer collaboration between critical gerontology research and age-friendly policy making and practice could unlock the full potential of age-friendly programmes, and enable them have more significant impact on the lives of older people.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the 14 older people who participated in the study for the generous contribution of their time, and their willingness to share their experience of living in Fingal, which made the study possible. A special thanks to the members of the Reference Panel who supported and advised on the project over a four-year period.

Author contributions

All authors have substantially contributed to the development of this article and have agreed to the authorship order.

Ethical standards

The study upon which this article is based received ethical approval from National University of Ireland Galway Ethics Committee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.