1. Introduction

Glossopteris was formally defined by Brongniart (Reference Brongniart1828), and the genus has been emended subsequently by several workers. This fossil-genus of tongue-shaped leaves with reticulate venation characterizes continental strata throughout the middle- to high-latitude regions of the Gondwanan Permian (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin2001, Reference McLoughlin2011). Indeed, the distribution of the genus was central to early arguments that the Southern Hemisphere continents were formerly united into a supercontinent (Gondwana) during late Palaeozoic time (du Toit, Reference du Toit1937). Glossopteris has so far been recorded throughout the core regions of Gondwana (India, Africa, Arabia, Madagascar, South America, Australia, Antarctica and New Zealand) with the notable exception of Sri Lanka (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin2001). In addition, a few leaves in peri-Gondwanan terranes, for example Thailand (Asama, Reference Asama1966), Turkey (Archangelsky & Wagner, Reference Archangelsky and Wagner1983), Laos (Bercovici et al. Reference Bercovici, Bourquin, Broutin, Steyer, Battail, Veran, Vacant, Khenthayong and Vongphamany2012) and in isolated parts of low-palaeolatitude Gondwana (e.g. Morrocco; Broutin et al. Reference Broutin, Aassoumi, El Wartiti, Freytet, Kerp, Quesada, Toutin-Morin, Crasquin-Soleau and Barrler1998) have been assigned to Glossopteris, but these records need thorough taxonomic re-appraisal. Leaves attributed to Glossopteris in areas remote from Gondwana, for example the Russian Far East (Zimina, Reference Zimina1967), together with examples from much younger strata, such as Triassic (Johnston, Reference Johnston1886) or Jurassic (Harris, Reference Harris1932; Delevoryas, Reference Delevoryas1969), undoubtedly belong to other plant groups that evolved morphologically similar leaves (Harris, Reference Harris1937; Delevoryas & Person, Reference Delevoryas and Person1975; Anderson & Anderson, Reference Anderson and Anderson2003).

Apart from its palaeobiogeographic importance, the Glossopteris flora contributed to the accumulation of vast economic coal resources across the Southern Hemisphere that are exploited and distributed globally for the generation of electricity, metal refining and other industrial purposes (Balme, Kershaw & Webb, Reference Balme, Kershaw, Webb, Ward, Harrington, Mallett and Beeston1995; Maher et al. Reference Maher, Bosio, Lindner, Brockway, Galligan, Moran, Peck, Walker, Bennett, Coxhead, Ward, Harrington, Mallett and Beeston1995; Rana & Al Humaidan, Reference Rana, Al Humaidan, Raisi and Gupta2016). Buried Permian plant remains (principally wood, spore/pollen and leaf material converted to type II and III kerogens) also constitute a major source of both conventional and coal-seam gas (McCarthy et al. Reference McCarthy, Rojas, Niemann, Palmowski, Peters and Stankiewicz2011), which are exploited widely in nations occupying the ancient Gondwanan landmass (Flores, Reference Flores2014).

Records of plant macrofossils from Sri Lanka are sparse. Previous studies have identified only Jurassic plants (Sitholey, Reference Sitholey1944; Edirisooriya & Dharmagunawardhane, Reference Edirisooriya and Dharmagunawardhane2013 a, Reference Edirisooriya and Dharmagunawardhane b ), and these have been recovered from outcrops in small isolated graben systems in the northwestern part of the island. No Permian fossils or strata have been reported from Sri Lanka so far, although Katupotha (Reference Katupotha2013) speculated that some topographic planation features and isolated erratic boulders might date back to an ancient glacial episode, the last of which affected this region during early Permian time (Fielding, Frank & Isbell, Reference Fielding, Frank, Isbell, Fielding, Frank and Isbell2008).

Here we describe the first assemblage of the Glossopteris flora from Sri Lanka derived from the first documented exposures of Permian strata in the Tabbowa Basin. In addition to Glossopteris, the flora contains the remains of ferns and sphenophytes that help constrain the age of the deposit. We also highlight the potential significance of this discovery for hydrocarbon source rocks in the adjacent (offshore) Mannar Basin.

2. Geological setting

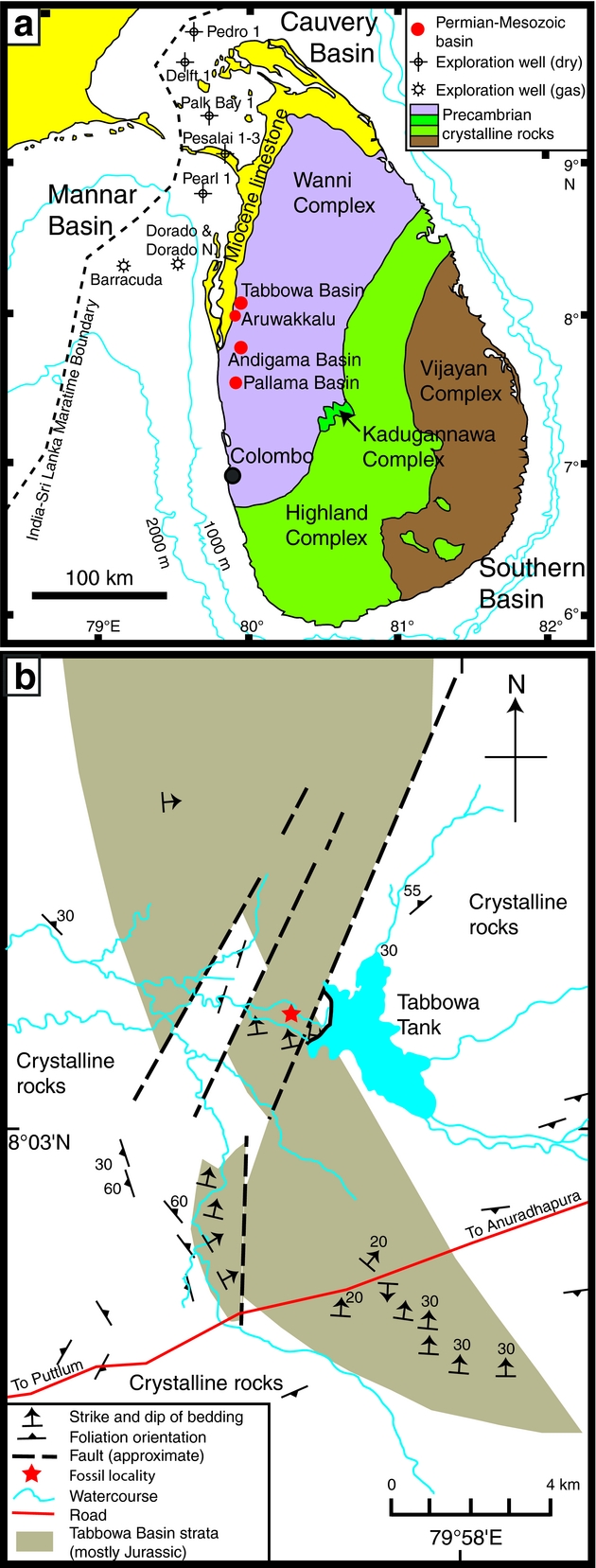

Around 90% of the bedrock in Sri Lanka consists of Precambrian crystalline rocks. Jurassic, Miocene and Quaternary strata are largely confined to a thin belt of exposures in the north and northwest of the island (Herath, Reference Herath1986; Fig. 1a). The fossiliferous strata sampled in this study are exposed close to the spillway of an irrigation reservoir – the Tabbowa Tank (8°04ʹ21ʺN, 79°56ʹE) – within the Tabbowa Basin (Fig. 1a, b). The Tabbowa Basin is a small graben previously considered to host only Jurassic strata. The basin extends over an area of only a few square kilometres in the Northwestern Province of Sri Lanka (Wayland, Reference Wayland1925; Cooray, Reference Cooray1984) and has a surface topography of slightly elevated but flat terrain. The graben developed in a crystalline basement terrane and hosts nearly 1000 m of strata consisting mostly of grey to reddish shales, mudstones, siltstones and arkosic sandstones (Cooray, Reference Cooray1984). A similar succession is developed 30 km to the south of Tabbowa in the Andigama–Pallama Basin, which hosts at least 350 m of strata (Herath, Reference Herath1986). The surrounding Precambrian basement rocks comprise mainly granitic gneisses with extensive jointing and faulting (Wayland, Reference Wayland1925; Cooray, Reference Cooray1984). Many of these structural features are parallel or orthogonal to the local graben systems and may have developed in association with Permian–Triassic extension and Mesozoic break-up of Gondwana (Cooray, Reference Cooray1984).

Figure. 1. Maps showing: (a) the major geological provinces of Sri Lanka and (b) the sample location (indicated by a star) adjacent to Tabbowa Tank (modified after Wayland, Reference Wayland1925 and Ratnayake & Sampei, Reference Ratnayake and Sampei2015).

In the offshore region between northwestern Sri Lanka and southern India (Tamil Nadu) lies the Mannar Basin (Fig. 1a), covering an area of about 45000 km2. This basin contains >6000 m of strata and is covered by water to depths generally greater than 1000 m (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2013). The sedimentary development of this basin is poorly understood since there have been relatively few seismic surveys and no hydrocarbon exploration wells have penetrated the full stratigraphic succession. To date, the succession has been subdivided into four informally defined allostratigraphic megasequences. The oldest, ‘megasequence IV’, has been assumed to represent mostly continental strata of Late Jurassic – early Albian age (Baillie et al. Reference Baillie, Barber, Deighton, Gilleran, Jinadasa and Shaw2004), based mainly on a model of basin initiation during middle Mesozoic continental break-up and by correlation with Jurassic strata in the onshore grabens of northwestern Sri Lanka (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2016). Significantly, Cairn Lanka Private Limited drilled several exploration wells in the Mannar Basin in 2011; two of these, CLPL-Dorado-91H/1z (Dorado) and CLPL-Barracuda-1G/1 (Barracuda), were the first to yield hydrocarbons (mostly gas) in Sri Lankan territory (Fig. 1a). The hydrocarbons were trapped in Campanian–Maastrichtian sandstones that are underlain by a substantial stratigraphic section of uncertain age, since no well in the basin has yet penetrated below Lower Cretaceous strata (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2013).

3. Materials and methods

More than 20 rock slabs bearing numerous Glossopteris leaves were recovered during this study from an outcrop c. 1 km west of Tabbowa Tank spillway (8°04ʹ22.59ʺN, 79°56ʹ29.32ʺE; Fig. 1b). Exposures in the area are poor and discontinuous due to deep weathering and soil cover; the sampled strata therefore cannot be placed in a continuous stratigraphic section. Several specimens of Sphenophyllum, sphenophyte ribbed axes and fertile fern foliage are co-preserved on the studied slabs. The plant macrofossils are preserved predominantly as impressions within grey shale. The fossils are typically a slightly darker shade of grey or are pinkish compared with the matrix, due to minor mineral staining or clay coatings. Some shales are strongly ferruginous with leaf impressions stained by iron oxides. No organic matter is preserved in the fossils, but venation details are well defined. Plant mesofossils, pollen and spores could not be extracted from these sediments due to deep weathering of the strata.

Fossils were photographed with an Optika vision Pro dissecting microscope and camera attachment under low-angle incident light from the upper left. Line drawings were produced by tracing venation details from images imported into Adobe Illustrator CS5. Leaf shape terminology follows that of Dilcher (Reference Dilcher1974), venation angle measurements follow the convention of McLoughlin (Reference McLoughlin1994a ) and leaf size categories are those of Webb (Reference Webb1959). All fossiliferous rock slabs are housed at the National Museum, Colombo, Sri Lanka and have been assigned registration numbers of that institution (CNM SA.1–SA.20); individual specimens on those slabs are designated with letter suffixes (a, b, c, etc.).

4. Systematic palaeobotany

Order Equisetales Dumortier, Reference Dumortier1829

Family uncertain

Genus Paracalamites Zalessky, Reference Zalessky1932

Type species. Paracalamites striatus (Schmalhausen) Zalessky, Reference Zalessky1927; by subsequent designation of Boureau (Reference Boureau1964); Jurassic, Russia.

Paracalamites australis Rigby, Reference Rigby1966 (Fig. 2m)

Material. Seven axes on CNM SA.7 and SA.8 (illustrated specimen: CNM SA.7b).

Description. Articulate ribbed stems preserved as external impressions in grey and reddish shales and siltstones (Fig. 2m). Fragmentary, longitudinally ribbed, linear axes, exceeding 80 mm long, 21 to >79 mm wide, with indistinct nodes. Ribs straight to flexuous, each with a central slender groove; ribs and intervening troughs smooth or with fine longitudinal striae. Ribs opposite at nodes or alternate only where new ribs are added. Ribs commonly bear fine longitudinal striae. There are 15–20 ribs visible across the stem. Ribs 0.5–5 mm apart depending on size of axis; density higher in small compared with large axes.

Figure 2. Permian plant fossils from the Tabbowa Basin. (a, b) Sphenophyllum churulianum Srivastava & Rigby, Reference Srivastava and Rigby1983, slender axes with leaf whorls (Reg. numbers CNM SA.7a and CNM SA.9a respectively). (c, d, g) Dichotomopteris lindleyi (Royle) Maithy, Reference Maithy1974; (c) enlargement of fertile pinna (CNM SA.8a); (d) rachis with attached subsidiary pinnae (CNM SA.8a); and (g) pinna showing variation of fertile and sterile pinnules (CNM SA.3a). (e, i–l) Glossopteris raniganjensis Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979, details of (e) leaf apex (CNM SA.9b); (j) base (CNM SA.5a); (k) mid-region (CNM SA.2a); and (i, l) venation CNM SA.2b and SA.5a, respectively. (f) Vertebraria australis (McCoy, Reference McCoy1847) emend Schopf, Reference Schopf1982, segmented glossopterid root (CNM SA.3b). (h) Samaropsis sp., winged seed (CNM SA.4a). (m) Paracalamites australis Rigby, Reference Rigby1966, ribbed axes (CNM SA.7b). Scale bars: (a–f, i–m) 10 mm and (g, h) 5 mm.

Remarks. None of the several fragmentary axes available retains attached foliage or fructifications. Moreover, the axes are too large to have accommodated co-preserved Sphenophyllum leaf whorls. They might have borne some other type of equisetalean foliage, such as Phyllotheca, which is common in Permian floras elsewhere in Gondwanan and typically co-preserved with Paracalamites axes (Prevec et al. Reference Prevec, Labandeira, Neveling, Gastaldo, Looy and Bamford2009), but such foliage has not yet been recorded from Tabbowa. The studied axes can be readily accommodated within Paracalamites australis based on their dimensions and coarse ribbing (Rigby, Reference Rigby1966; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1992a , Reference McLoughlin and Drinnan b ).

Order Sphenophyllales Campbell, Reference Campbell1905

Family Sphenophyllaceae Potonié, Reference Potonié1893

Genus Sphenophyllum Koenig, Reference Koenig1825

Type species. Sphenophyllum emarginatum (Brongniart) Koenig, Reference Koenig1825; ?Carboniferous, Gotha, Thuringia, Germany.

Sphenophyllum churulianum Srivastava & Rigby, Reference Srivastava and Rigby1983 (Fig. 2a, b)

Material. More than 10 leaf whorls on rock slabs CNM SA.2, SA.7 and SA.9 (illustrated specimens: CNM SA.7a and SA.9a).

Description. Slender, striate, segmented axes 1–1.5 mm wide, expanded slightly near nodes, bearing radially arranged whorls of six leaves at nodes (Fig. 2a, b); internodes 25–28 mm long. Leaves not forming a basal sheath, generally equal in size, but varying in degree of apical dissection. A few whorls appear to have leaves of variable size (Fig. 2b), but this may be a consequence of oblique compression. Leaves wide obovate to narrow obovate or oblanceolate, 25–27 mm long, up to 18 mm wide, base cuneate, apex gently to moderately dissected by one or more notches up to c. 5 mm deep, rarely entire. Single vein enters the leaf and bifurcates regularly to maintain vein concentrations of 7–8 per centimetre. Veins straight to gently arched and mostly terminating at apical margin.

Remarks. The more-or-less equal-sized and symmetrically arranged leaves of this taxon favour its assignment to Sphenophyllum rather than the superficially similar but bilaterally symmetrical Trizygia within the Sphenophyllales. Sphenophyllum has a long range through the Permian of Gondwana, whereas Trizygia is more typical of Upper Permian assemblages (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1992a ; Goswami, Das & Guru, Reference Goswami, Das and Guru2006). McLoughlin (Reference McLoughlin1992b , table 1) summarized the general morphological characters of Permian Gondwanan Sphenophyllum leaves. Most taxa can be differentiated using a combination of characters related to leaf shape, size and the degree of apical dissection. The Sri Lankan forms are similar to Sphenophyllum archangelskii Srivastava & Rigby, Reference Srivastava and Rigby1983 from the Laguna Polina Member, La Golondrina Formation (Guadalupian) of Argentina in leaf dimensions and their depth of dissection, but the latter have more numerous apical incisions. Although Srivastava & Rigby (Reference Srivastava and Rigby1983) described Sphenophyllum churulianum (from the Guadalupian Barakar Formation of India) as being entire, most of the apices on the holotype are damaged, and specimens attributed to this species subsequently (Srivastava & Tewari, Reference Srivastava and Tewari1996) have a subtle central apical notch a few millimetres deep. The species has also been reported from the Kamthi Formation (Lopingian) of India (Goswami, Das & Guru, Reference Goswami, Das and Guru2006), indicating a long stratigraphic range in that region. We tentatively ascribe the Sri Lankan specimens to S. churulianum with the qualification that cuticles and fructifications of this taxon, which would enhance confidence in identification, remain unknown from India or Sri Lanka.

Order ?Osmundales Link, Reference Link1833

Genus Dichotomopteris Maithy, Reference Maithy1974

Type species. Dichotomopteris major (Feistmantel) Maithy, Reference Maithy1974; Raniganj Formation (Late Permian), Damuda Group, Raniganj Coalfield, India.

Dichotomopteris lindleyi (Royle) Maithy, Reference Maithy1974 (Fig. 2c, d, g)

Material. Around 20 frond fragments on rock slabs CNM SA.3, SA.7 and SA.8 (illustrated specimens: CNM SA.3a, SA.8a).

Description. Fronds tripinnate. Rachis longitudinally striate, reaching 25.0 mm wide (Fig. 2d). Primary pinnae robust, alternate, orientated at 30–90° to rachis, longitudinally striate, up to 8.0 mm wide. Secondary pinnae linear to lanceolate, alternate; inserted on primary pinna rachilla at c. 90° proximally, c. 45° distally; apex with terminal rounded pinnule; rachilla 1 mm wide. Sterile ultimate pinnules oblong, entire, alternate, up to 8 mm long and 5 mm wide, inserted at 60–90° to parent rachilla (Fig. 2g). Pinnules appear to have full basal attachment and a decurrent basiscopic margin; apices rounded. Midvein prominent; lateral veins undivided or once-forked, typically at around 60° to midvein. Fertile pinnules with entire to slightly undulate margins, bearing circular sori, c. 1 mm in diameter, aligned through the mid-lamina region along each side of the midvein (Fig. 2c, g).

Remarks. These specimens match the characters of Dichotomopteris lindleyi Maithy, Reference Maithy1974, originally described from India, but widely reported across eastern Gondwana (Royle, Reference Royle1833–Reference Royle1840; Maithy, Reference Maithy1975; Rigby, Reference Rigby and Skwarko1993; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1993). This species differs from the other widely reported eastern Gondwanan ferns attributed to Neomariopteris species by their oblong, generally entire-margined pinnules and prominent row of mid-lamina sori. This type of foliage is considered to have probable osmundacean affinities based on the presence of Osmundacidites-like in situ spores in fertile specimens, and its occurrence in association with Palaeosmunda axes elsewhere in Gondwana (Gould, Reference Gould1970; Maithy, Reference Maithy1974; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1992a ). Based on the >20 mm width of the rachis in some specimens, these fronds derive from a fern of substantial size; it may have attained an erect (tree-fern) habit.

Order Glossopteridales sensu Pant (Reference Pant1982)

Genus Glossopteris Brongniart, Reference Brongniart1828 ex Brongniart, Reference Brongniart1831

Type species. Glossopteris browniana Brongniart, Reference Brongniart1828, by subsequent designation of Brongniart (Reference Brongniart1831); ?Newcastle or Tomago Coal Measures (Guadalupian or Lopingian), Sydney Basin, Australia.

Glossopteris raniganjensis Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979 (Figs 2e, i, j–l; 3; 4a–i)

Material. More than 85 leaves on rock slabs CNM SA.1–SA.20 (illustrated leaves: CNM SA.2a, SA.2b, SA.2c, SA.2d, SA.2e, SA.2f, SA.2g, SA.5a, SA.9b, SA.9c, SA.9d, SA10a, SA.10b, SA.10c).

Description. All leaves are incomplete, 55 to >150 mm long, 10–46 mm wide (notophyll–mesophyll), narrowly elliptical, narrowly obovate, oblanceolate or narrowly oblanceolate. Base cuneate-acute (Fig. 2j, k); apex generally pointed acute (Fig. 2e), in a few cases obtuse. Position of the widest point at one-half to four-fifths lamina length. Margin entire. Midrib 0.5–1.5 mm wide at base of lamina, tapering distally but persisting to apex. Secondary veins emerge from midrib at c. 5–20°, arch moderately to sharply near midrib, then pass with gentle curvature across the lamina to intersect the margin at typically 60–80°; degree of arching c. 10–20° (Figs 2i, l; 3). Secondary veins dichotomize and anastomose 2–7 times across the lamina generating short triangular, semicircular and rhombic areolae near the midrib, becoming elongate polygonal, narrowly linear and falcate towards the margin (Fig. 3). Vein density near the midrib is typically 6–10 per centimetre, increasing to 15–30 per centimetre near the margin.

Figure 3. Line drawing of venation details of Glossopteris raniganjensis Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979 (CNM SA.2c). Scale bar: 10 mm.

Remarks. Although there is modest variation in the size, venation angles and degree of anastomoses among Glossopteris leaves in the Tabbowa assemblage, the continuum in preserved forms suggests that these all belong to a single natural species. Over 100 species of Glossopteris have been established since the genus was defined by Brongniart (Reference Brongniart1828), and many species names have been applied in a broad sense to encompass diverse leaf morphotypes. We favour the more restrictive definitions of species applied by Chandra & Surange (Reference Chandra and Surange1979) in their review of the Indian species of the genus, since that scheme employs more rigorous morphological criteria and has biostratigraphic utility.

Several established species, especially G. indica Schimper, Reference Schimper1869, G. communis Feistmantel, Reference Feistmantel1879, G. decipiens Feistmantel, Reference Feistmantel1879, G. arberi Srivastava, Reference Srivastava1956, G. spatulata Pant & Singh, Reference Pant and Singh1971, G. tenuinervis Pant & Gupta, Reference Pant and Gupta1971, G. nimishea Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979 and G. raniganjensis Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979, bear marked similarities in size, shape, vein density and narrow areolae to the Glossopteris leaves described here. Of these, G. arberi and G. communis differ from the Tabbowa specimens by having an obtuse apex and relatively few secondary vein anastomoses. Glossopteris decipiens, G. indica, G. nimishea and G. spatulata have less strongly arched veins in either the inner or outer portions of the lamina and consequently tend to have lesser marginal venation angles than the Tabbowa specimens. Glossopteris tenuinervis has generally straighter secondary veins and a greater marginal venation angle. Glossopteris raniganjensis was one of several species that Chandra & Surange (Reference Chandra and Surange1979) segregated from the broadly defined ‘G. communis-type’ complex of leaves. The similarities between G. raniganjensis specimens from the Kamthi Formation of India and the Tabbowa specimens is especially notable in their dimensions, acute apices, vein density and secondary veins that are inserted at low angles to the midrib in the inner lamina but pass outwards in sweeping arcs to the margin. We, therefore, confidently assign the Sri Lankan specimens to that species.

Genus Samaropsis Goeppert, Reference Goeppert1864

Type species. Samaropsis ulmiformis Goeppert, Reference Goeppert1864. Permian, Braunau, Bohemia.

Samaropsis sp. (Fig. 2h)

Material. Two poorly preserved small seeds are available on sample CNB SA.4 of which one (CNB SA.4a) is illustrated (Fig. 2h).

Description. The seeds are roughly circular, c. 1–2 mm in diameter with a longitudinally elliptical inner body flanked by a pair of <0.5 mm wings. A short micropylar extension is present but the details are ill-defined.

Remarks. Similar small winged seeds have been recorded extensively from Permian strata across Gondwana (Maithy, Reference Maithy1965; Millan, Reference Millan1981; Anderson & Anderson, Reference Anderson and Anderson1985; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1992a ; Bordy & Prevec, Reference Bordy and Prevec2008). When preserved as impressions they offer few characters for consistent taxonomic differentiation or affiliation. Only when attached to fructifications (e.g. Pant & Nautiyal, Reference Pant and Nautiyal1984; Anderson & Anderson, Reference Anderson and Anderson1985; Prevec, Reference Prevec2011, Reference Prevec2014) or preserved as permineralizations with pollen in the micropyle (Gould & Delevoryas, Reference Gould and Delevoryas1977; Ryberg, Reference Ryberg2010) can such seeds be confidently affiliated with glossopterids. Nevertheless, the absence of any gymnosperm foliage other than Glossopteris in the Tabbowa Basin macrofossil assemblage makes a strong case for the studied seeds having affinities to G. raniganjensis.

Genus Vertebraria Royle ex McCoy, Reference McCoy1847 emend. Schopf, Reference Schopf1982

Type species. Vertebraria australis (McCoy, Reference McCoy1847) emend Schopf, Reference Schopf1982; Raniganj Formation (upper Permian), Ranigani Coalfield, India.

Vertebraria australis (McCoy, Reference McCoy1847) emend Schopf, Reference Schopf1982 (Fig. 2f)

Material. Two roots on sample CNM SA.3, of which one (CNM SA.3b) is illustrated (Fig. 2f).

Description. These roots are preserved as impressions along bedding planes hosting fern foliage and sphenophyte axes (Fig. 2f). The roots exceed 100 mm long but are less than 10 mm wide and bear irregular longitudinal and transverse creases.

Remarks. Schopf (Reference Schopf1982), Doweld (Reference Doweld2012), Joshi et al. (Reference Joshi, Tewari, Agnihotri, Pillai and Jain2015) and Herendeen (Reference Herendeen2015) have discussed at length the complex nomenclatural history of glossopterid root fossils attributed to Vertebraria. Here we follow the recent decision of the Nomenclature Committee on Fossil Plants (Herendeen, Reference Herendeen2015) in retaining Vertebraria australis (McCoy, Reference McCoy1847) emend Schopf, Reference Schopf1982 as the type of this genus. Moreover, since there are no meaningful morphological or anatomical differences between V. australis (originally described from Australia) and V. indica (Unger) Feistmantel, Reference Feistmantel1876 (originally described from India), we apply the former name to the Sri Lankan Permian roots.

The Sri Lankan specimens are irregularly segmented roots typical of V. australis, the root form universally linked to glossopterids (Gould, Reference Gould and Campbell1975; McLoughlin, Larsson & Lindström, Reference McLoughlin, Larsson and Lindström2005; Decombeix, Taylor & Taylor, Reference Decombeix, Taylor and Taylor2009). The Tabbowa Basin specimens are small and probably represent distal rootlets with few internal compartments. They approach the size and morphology of terminal rootlets that Pant (Reference Pant1958) assigned to Lithozhiza tenuirama but possess some segmentation. No additional characters are available from the studied specimens that add to the extensive descriptions of V. australis from other parts of Gondwana.

5. Arthropod–plant interactions

Various forms of damage are evident on the Glossopteris leaves from Tabbowa. Some represent physical attrition features, but others were evidently produced by arthropod herbivory or egg-laying habits based on their distinctive shapes, distributions, necrotic rims or similarity to modern forms of insect/mite-induced damage. Five moderately common types of arthropod-induced damage on Glossopteris leaves identified in the Tabbowa assemblage are outlined in the following sections. This diversity is consistent with the range of feeding strategies registered previously for Gondwanan glossopterids (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1990, Reference McLoughlin2011; Adami-Rodriguez, Iannuzzi & Pinto, Reference Adami-Rodrigues, Iannuzzi and Pinto2004; Beattie, Reference Beattie2007; Prevec et al. Reference Prevec, Labandeira, Neveling, Gastaldo, Looy and Bamford2009, Reference Prevec, Gastaldo, Neveling, Reid and Looy2010; Srivastava & Agnihotri, Reference Srivastava and Agnihotri2011; Cariglino & Gutiérrez, Reference Cariglino and Gutiérrez2011; Slater, McLoughlin & Hilton, Reference Slater, McLoughlin and Hilton2012). No unequivocal arthropod damage was detected on any of the non-glossopterid elements of the flora.

5.a. Hole feeding

Several leaves have large elliptical to linear incisions in the middle to outer parts of the lamina that broadly follow the course of the veins (Fig. 4a, c). Each incision removes tissue spanning several secondary veins and interveinal areas. The margins of the damaged areas vary from smooth to somewhat irregular and are surrounded by a very narrow reaction rim.

Figure 4. Arthropod (a–h) interactions and (i) physical attrition on Glossopteris raniganjensis Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979 leaves. (a, c) Elliptical hole feeding traces with slender reaction rims (arrowed) (CNM SA10a and CNM SA.2d, respectively). (b) Deep, U-shaped, margin-feeding damage (arrowed) (CNM SA.2e). (d) Oviposition scars flanking and overlying the leaf midrib (arrowed) (CNM SA.2f). (e) Possible skeletonization damage through a portion of the lamina (CNM SA.10b). (f) Possible early-stage margin feeding damage represented by tapering clefts (arrowed) on either side of the lamina in the apical half of the leaf (CNM SA.2g). (g, h) Possible piercing-and-sucking scars situated over secondary veins (Reg. numbers CNM SA.9c and CNM SA.10c respectively). (i) Lamina tearing along secondary veins (CNM SA.9d). All scale bars: 10 mm.

Similar hole-feeding damage has been recorded on Permian Glossopteris leaves from India (Srivastava & Agnihotri, Reference Srivastava and Agnihotri2011, fig. 2f) and in similar-aged gigantopterid foliage from China (Glasspool et al. Reference Glasspool, Hilton, Collinson and Wang2003). Such external foliage feeding might have been produced by protorthopteroids or coleopterans (Labandeira, Reference Labandeira2006) during Permian time, but a specific causal agent cannot be identified in this instance.

5.b. Margin feeding

At least one clear example of margin feeding is represented in the small assemblage of leaves from Tabbowa (Fig. 4b). It is expressed by a deep (6 mm long, 2.5 mm wide) U-shaped incision in the margin of the mid-region of a Glossopteris leaf. The scallop terminus is rounded and the margin is relatively smooth with a minimally developed reaction rim. A second specimen bears tapering clefts on either side of the lamina in the apical half of the leaf (Fig. 4f). The clefts penetrate about half the width of the lamina.

Similar U-shaped margin-feeding damage has been reported on Glossopteris leaves from Australia (Beattie, Reference Beattie2007), South Africa (Prevec et al. Reference Prevec, Labandeira, Neveling, Gastaldo, Looy and Bamford2009), Brazil (Adami-Rodriguez, Iannuzzi & Pinto, Reference Adami-Rodrigues, Iannuzzi and Pinto2004) and India (Srivastava & Agnihotri, Reference Srivastava and Agnihotri2011). This U-shaped damage may have been caused by the feeding habits of protorthopteroids or coleopterans.

Based on their rounded shoulders, the clefts in specimen CNM SA.2g (Fig. 4f) also appear to represent faunal rather than abiological (e.g. wind) damage. They may represent examples of margin feeding during the early stages of leaf development before the lamina had fully expanded. Examples of Glossopteris retusa (Maheshwari, Reference Maheshwari1965) and Glossopteris major (Pant & Singh, Reference Pant and Singh1971) from India, and Glossopteris truncata (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1994b ) from Australia bear similar notched margins in the apical half of the leaves that may derive from an equivalent process.

Other leaves in the Tabbowa assemblage have sharp clefts (lacking rounded shoulders) that penetrate all the way to the midrib following the course of the secondary venation (Fig. 4i). These are more likely to represent physical attrition features (simple tears along secondary veins) through wind or aqueous transport rather than arthropod feeding damage.

5.c. Oviposition scars

A single Glossopteris leaf in the assemblage bears two possible arthropod oviposition scars (Fig. 4d). Two elliptical scars of similar dimensions (1×2 mm) and with depressed margins are positioned along the flank and on top of the leaf midrib.

These traces are considered probable insect (odonatan?) oviposition scars based on their similarity in size, shape and position against the midrib to several previous examples noted on Glossopteris leaves from Australia (McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1990, Reference McLoughlin2011), South Africa (Prevec et al. Reference Prevec, Labandeira, Neveling, Gastaldo, Looy and Bamford2009, Reference Prevec, Gastaldo, Neveling, Reid and Looy2010), South America (Adami-Rodriguez, Iannuzzi & Pinto, Reference Adami-Rodrigues, Iannuzzi and Pinto2004; Cariglino & Gutiérrez, Reference Cariglino and Gutiérrez2011) and India (Srivastava & Agnihotri, Reference Srivastava and Agnihotri2011).

5.d. Skeletonization

A single example of possible partial leaf skeletonization is present in the assemblage (Fig. 4e). A significant segment of the mid-portion of this Glossopteris raniganjensis leaf has inter-secondary vein degradation. This zone tracks the orientation of the secondary veins and the leaf shows no differential staining in this area, so the damage does not appear to be an effect of weathering.

Examples of skeletonization in Glossopteris leaves are scarce and equivocal, although Adami-Rodriguez, Iannuzzi & Pinto (Reference Adami-Rodrigues, Iannuzzi and Pinto2004, fig. 6E, F) illustrated one putative example from Permian strata of Brazil that is similar to the example documented here. A causal agent cannot be ascertained.

5.e. Piercing-and-sucking damage

Several leaves bear small (<1 mm diameter) circular scars over the midrib (Fig. 4g) or secondary veins (Fig. 4h). These are similar to piercing-and-sucking damage on a broad range of leaves in the Mesozoic (McLoughlin, Martin & Beattie, Reference McLoughlin, Martin and Beattie2015). Labandeira (Reference Labandeira2006) noted that piercing-and-sucking damage was already widely developed on fern and gymnosperm leaves by late Palaeozoic time and might have been produced by various groups, such as palaeodictyopteroid or early hemipteroid insects (Labandeira & Phillips, Reference Labandeira and Phillips1996).

6. Discussion and conclusions

6.a. Plant taphonomy

The plant fossils are generally well preserved and variably orientated. The assemblage is dominated by Glossopteris leaves and associated organs, with lesser proportions (<5% each) of Sphenophyllum leaf whorls, large longitudinally ribbed Paracalamites (sphenophyte) axes and Dichotomopteris (fern) fronds. No complete plants or foliage-bearing woody axes were identified. The dominant leaves in the assemblage fall into the notophyll–mesophyll size range of Webb (Reference Webb1959). A few leaves are partially torn along the venation (Fig. 4i), and many are dissected by fracturing of the bedding planes. The leaves are otherwise relatively complete which, together with the fine-grained, fissile lithology, suggests deposition within relatively quiet-water (lacustrine) settings. Their dense association is consistent with preservation as an autumnal leaf accumulation, a taphonomic feature typical of glossopterid foliar fossil assemblages (Plumstead, Reference Plumstead1969; McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1993; McLoughlin, Larsson & Lindström, Reference McLoughlin, Larsson and Lindström2005; Slater, McLoughlin & Hilton, Reference Slater, McLoughlin and Hilton2015).

6.b. Age of the fossil assemblage

Deep Cenozoic weathering has eliminated any opportunity to undertake palynostratigraphic analysis of the exposed strata at Tabbowa, although coring of deep subsurface strata may yield spore-pollen assemblages in the future. Currently, plant macrofossils provide the only means of dating these strata. Most of the plant genera recorded in the new fossil assemblage (i.e. Paracalamites, Sphenophyllum, Glossopteris, Vertebraria and Samaropsis) have long ranges in the Permian strata of Gondwana. However, Dichotomopteris lindleyi, and indeed other members of this genus, are most common in Lopingian strata (Raniganj Formation and equivalents) in the rift basins of Peninsula India (Chandra, Reference Chandra, Surange, Lakhanpal and Bharadwaj1974; Maithy, Reference Maithy1975; Pant & Misra, Reference Pant and Misra1977; Goswami, Das & Guru, Reference Goswami, Das and Guru2006) and the foreland basins of eastern Australia (Burngrove Formation and equivalents: McLoughlin, Reference McLoughlin1992a ). Similarly, Glossopteris raniganjensis is most common in the Lopingian Raniganj and Kamthi formations of eastern India, although a few examples from the underlying Barakar and Kulti formations (Guadalupian–Lopingian) have also been attributed to this species (Chandra & Surange, Reference Chandra and Surange1979). Sphenophyllum churulianum, initially described from the Barakar Formation of India (Srivastava & Rigby, Reference Srivastava and Rigby1983) and tentatively dated as Guadalupian on the basis of palynostratigraphic correlations proposed by Veevers & Tewari (Reference Veevers and Tewari1995) and revised dating of those palynozones by Nicoll et al. (Reference Nicoll, McKellar, Areeba Ayaz, Laurie, Esterle, Crowley, Wood, Bodorkos and Beeston2015), has subsequently been identified in Lopingian strata in India (Goswami, Das & Guru, Reference Goswami, Das and Guru2006). Although high-resolution biostratigraphic indices are lacking, the limited macrofloral data outlined above broadly favour a Lopingian (late Permian) age for the Glossopteris-bearing beds near Tabbowa Tank.

6.c. Significance for hydrocarbon exploration

Sri Lanka currently imports all of its hydrocarbon requirements, imposing considerable constraints on the national economy (Singh, Reference Singh and Lall2009). The recent discovery of natural gas reservoirs in the offshore Mannar Basin has led to some hope of developing a domestic hydrocarbon energy source (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2016). Nevertheless, the source(s) and generation history of gas in the Mannar Basin remain poorly resolved. Current models have tied the evolution of the basin to mid-Mesozoic continental rifting associated with the break-up of Gondwana, but we hypothesize that the basin may have initiated during late Palaeozoic time with intra-rift continental sedimentation, and only later accumulated a thick blanket of Jurassic–Cretaceous strata linked to continental separation.

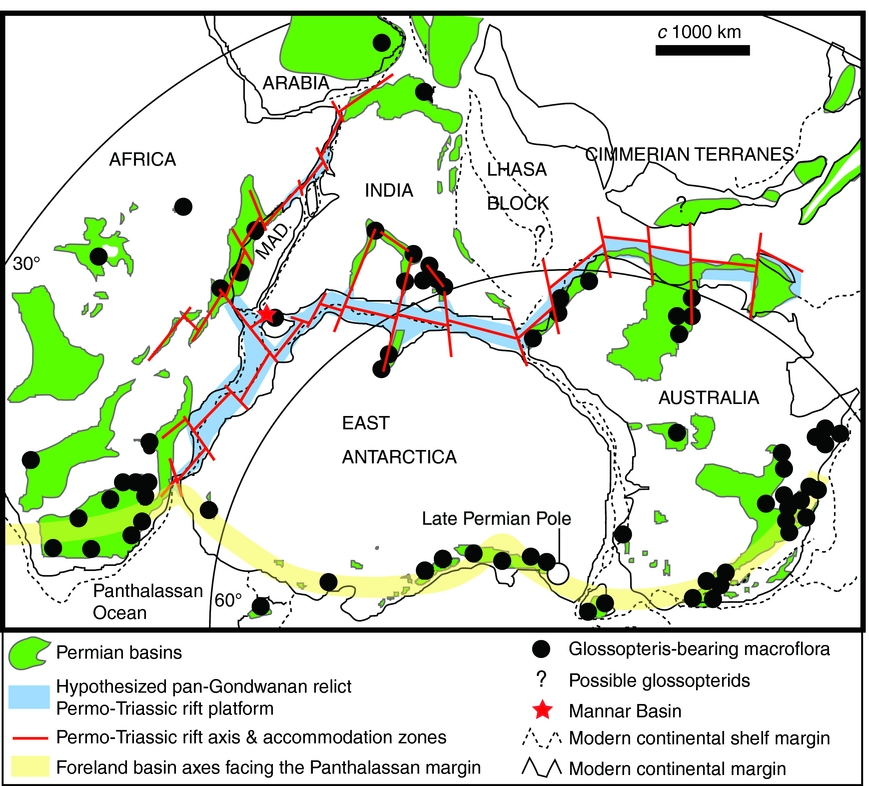

Seismic profiles through the offshore Mannar Basin reveal a thick sedimentary succession transected by normal faulting below the mid-Cretaceous–Cenozoic interval (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2016, fig. 4). Hydrocarbon exploration wells have so far penetrated the succession only down to strata of mid-Cretaceous age. Past geological modelling has generally inferred a Jurassic – Early Cretaceous age for the basin's lowermost (unexplored) strata (Baillie et al. Reference Baillie, Barber, Deighton, Gilleran, Jinadasa and Shaw2004; Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2013). However, prominent and laterally continuous seismic reflectors within the lower part of this succession (Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2016, fig. 4) may represent Permian coals or organic-rich lacustrine mudrocks. Such strata are known to have developed extensively within the Permian–Triassic pan-Gondwanan rift system prior to continental break-up, which developed along the same structural domain during middle Mesozoic time (Boast & Nairn, Reference Boast, Nairn, Nairn and Stehli1982; Casshyap & Tewari, Reference Casshyap, Tewari, Rahmani and Flores1984; Kreuser, Reference Kreuser1987; Cockbain, Reference Cockbain and Trendall1990; Smith, Reference Smith1990; McLoughlin & Drinnan, Reference McLoughlin and Drinnan1997a , b; Delvaux, Reference Delvaux and Weiss2001; Holdgate et al. Reference Holdgate, McLoughlin, Drinnan, Finkelman, Willett and Chiehowsky2005; Harrowfield et al. Reference Harrowfield, Holdgate, Wilson and McLoughlin2005). Notably, Permian strata are also present in the subsurface of the Indian sector of the Cauvery Basin (Basavaraju & Govindan, Reference Basavaraju and Govindan1997), which represents a northerly extension of the Mannar Basin failed rift system (Premarathne, Reference Premarathne2015). The discovery of strata hosting a glossopterid-dominated macroflora in the parallel onshore Tabbowa Basin now lends support to the development of Permian subsidence and sedimentation within the whole northwestern Sri Lankan sector as part of the late Palaeozoic pan-Gondwanan rifting event (Harrowfield et al. Reference Harrowfield, Holdgate, Wilson and McLoughlin2005). We hypothesize that this event may have left remnants of a Permo-Triassic, predominantly continental, stratigraphic succession not only in the Mannar Basin, but throughout the pan-Gondwanan rift corridor. This intra-rift succession constitutes a potentially important hydrocarbon (especially gas) target for future exploration (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Map of central Gondwana at the end of Palaeozoic time showing the distribution of Permian basins, deposits hosting Glossopteris macrofloras, the location of the Mannar Basin, and the hypothesized relict pan-Gondwanan Permo-Triassic rift-fill system (modified from Harrowfield et al. Reference Harrowfield, Holdgate, Wilson and McLoughlin2005).

Permian continental strata, particularly those rich in coals (dominated by type II and III kerogens), represent important natural gas source rocks in various sectors of the pan-Gondwanan rift corridor (Kantsler & Cook, Reference Kantsler and Cook1979; Kreuser, Schramedei & Rullkotter, Reference Kreuser, Schramedei and Rullkotter1988; Clark, Reference Clark1998; Raza Khan et al. Reference Raza Khan, Sharma, Sahota and Mathur2000; Ghori, Mory & Iasky, Reference Ghori, Mory and Iasky2005; L. Dresy, unpubl. MSc thesis, University of Stavanger, 2009; Farhaduzzamana, Abdullaha & Islam, Reference Farhaduzzamana, Abdullaha and Islam2012). Should the basal strata of the Mannar Basin be confirmed to host Permian plant-rich sediments, as in the adjacent Tabbowa Basin, this will enhance the hydrocarbon prospectivity of the region. This is especially the case since the basal succession of the Mannar Basin has been modelled to lie within the oil- to gas-generating windows (Ratnayake & Sampei, Reference Ratnayake and Sampei2015; Premarathne et al. Reference Premarathne, Suzuki, Ratnayake and Kularathne2016).

Acknowledgements

Financial support to SM from the Swedish Research Council (VR grant 2014–5234) and National Science Foundation (project #1636625) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the Director of the National Museum, Colombo, Sri Lanka and her staff for the loan of the museum samples. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript.