Stereotypes have long been used by political administrations to motivate or raise support for policies regarding immigration or national security. Consider, for instance, Franklin D. Roosevelt's description of US Italian aliens after Fascist Italy declared war on the United States. Questioned on what to do with the hundreds of thousands of non-naturalised Italians living in America at the time, Roosevelt played down the threat that these immigrants could pose to national security by famously declaring: ‘I don't care so much about the Italians: they are a lot of opera singers.’Footnote 1

These notorious words, which Roosevelt uttered confidentially to Attorney General Francis B. Biddle, conjure a strange but persistent association between opera and Italians living in America. In the United States, opera had been a marker of Italian culture in the eyes and ears of middle-class Americans since this genre was first securely established in the country in the 1820s. I will argue in this article, however, that the depiction of Italian immigrants as opera singers and aficionados was of more recent vintage. It was, above all, the byproduct of mass advertising for home phonographs and gramophones in the early twentieth century. In those years, the availability of sound reproduction technology on the one hand, and the use of Italian opera as a promotional vessel on the part of the recording industry on the other, made Italian immigrants and their descendants newly visible and audible. And it was from this technological and media context of nascent sound reproduction technology, interwoven with the growth of mass advertising, that a distinctive Italian American musical culture would eventually emerge in the decades that followed.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Italian immigration to the USA had reached its peak, with 2.8 million new arrivals between 1890 and 1910.Footnote 2 In the face of mounting nativist hostility, the phonograph offered Italian political leaders and the Italian-language press new opportunities to improve the image of their immigrant compatriots.Footnote 3 One possible strategy to effect this change was to embrace the reputation of the phonograph as a scientific instrument, a label that was conferred upon the device thanks to its use in contemporary ethnographic research. In the United States as elsewhere, the use of the phonograph had become routine in projects of salvage ethnography, recording for posterity the languages and music of those peoples believed to be on the brink of extinction. As Brian Hochman has observed, ideas about racial and cultural difference helped to define new uses for the phonograph, whose authority as a scientific instrument increased alongside its capacity to confirm evolutionary racism in a self-reinforcing process.Footnote 4

In line with newspapers and music trade journals in English, the Italian-language press in America frequently commented upon the civilising mission that the phonograph was carrying out in the most remote areas of the planet. In the summer of 1901, for example, Il progresso italo-americano, the largest Italian newspaper in the New York area, reported on a recent expedition to Lake Victoria, Uganda, by the British ethnographer Harry Johnston, who had returned to London to deposit several phonographic cylinders and other exotic specimens in the British Museum. In recounting these distant events, Il progresso embellished the story, explaining that the cylinders documented the language of ‘strange’ tribes whose members ‘curiously resemble[d] baboons and le[d] a simian lifestyle’.Footnote 5 Such descriptions were ready-made. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the growing influence of Darwinism among sociologists and biological anthropologists on both sides of the Atlantic led to the definition of racial classifications that placed Black people on the lowest steps of the evolutionary scale. In 1871, for example, influential Italian criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso maintained that people of African origins were closer to monkeys than any other human race, and that because of their supposed evolutionary imperfections they were especially prone to criminal behaviour. Along with other anthropologists, including Giuseppe Sergi and Alfredo Niceforo, Lombroso postulated the existence of a racial difference between Southern Italians (believed to have African ancestry) and residents of Northern Italy. Far from being confined to Italy, the ideas of these scholars also circulated in the USA and were promptly adopted by anti-immigration advocates in the early twentieth century.Footnote 6

Given the deeply embedded racism of Jim Crow-era US society, it is little wonder that Italian-language newspapers attempted to distance Italian immigrants from African Americans by promoting a view of Italian culture and civilisation founded on the celebration of symbolically relevant events and periods of Italian history, including the Roman Empire, the Renaissance and the Risorgimento.Footnote 7 The growth of the recording industry made Italian opera more visible, which helped to corroborate this nationalistic narrative. In the early 1900s, major phonograph and record manufacturers began to invest in musical genres that were especially associated with notions of cultural refinement in order to make the phonograph appealing to the white middle class. Although symphonic music held a privileged position in the cultural hierarchies of the upper classes, opera proved a more effective choice for record companies. Because of the technological limitations of acoustic recording, some of the sound produced by performers was dispersed during the recording process, putting loud voices at an advantage over large and timbrally varied instrumental ensembles. Moreover, short arias or vocal ensembles could be contained more easily than longer symphonic works within the few minutes of recording time allowed by early cylinders and discs. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, and until the advent of electrical recording in 1925, record companies especially trafficked in the self-contained, melody-driven arias of bel canto and verismo Italian opera, performed by celebrated singers such as Enrico Caruso, Antonio Scotti, Giovanni Zenatello, Titta Ruffo, Marcella Sembrich, Nellie Melba and Luisa Tetrazzini.

While scholars have discussed the imperialistic thought underpinning the use of recording technology in ethnographic expeditions, the racial implications of the commercialisation of the phonograph as a form of domestic entertainment remain largely unexamined. Yet this marketing process was profoundly shaped by notions of racial and social difference. As Marsha Seifert, William Howland Kenney, Alexander Magoun, David Suisman and other historians of early recording technology have demonstrated, it took the recording industry both time and considerable financial resources to credibly present the new device as an in-home recreational medium for the American middle class.Footnote 8 In order to make the phonograph desirable, recording companies first had to sever easy associations with earlier devices often linked to socially and racially undesirable groups: namely, the barrel organs and barrel pianos employed by street musicians, and the coin-operated phonographs that had appeared in public places across the country since the early 1890s.

The increased commercial availability of the home phonograph, and the implementation of opera-centred promotional strategies on the part of major recording companies, had important consequences for American residents of Italian descent. First of all, the appearance of the phonograph in public spaces and private homes gradually eroded the social relevance of the street musician, a figure with which Italian immigrants had long been stereotypically associated in the contemporary press. Secondly, the prominent role that recording labels assigned to Italian opera ended up increasing the visibility of this genre, transforming it into a possible vessel for the social enfranchisement of Italian immigrants at a time when they still were targets for racism and discrimination.

In this article I focus on Italian immigrants to shed light on the racial and social repercussions of the historical process that led to the emergence of the home phonograph. At the beginning of this process, the mainstream press and its mostly middle-class readership associated Italians and African Americans with one another, by connecting the evolution of mechanical instruments such as the barrel organ into the phonograph with the evolutionary theories espoused by scientific racism. At a later stage, peddlers of modern techological sound devices worked hard to separate their products from the powerful racial undertones of mechanical music. To sell home phonographs, they had to break the chain of association that connected Italian street entertainers – who sometimes performed alongside monkeys, seen as evolutionarily inferior beings – to barrel organs and pianos, with their pinned cylinders and rolls, and to phonographic cylinder machines. If the recording technology of phonographs had simply been presented as a descendant of previous mechanical instruments, then the dubious social reputation of the street performers who had used them would also have risked rubbing off on this new device. Similarly, phonographs for in-home use could hardly be promoted as vessels of cultural refinement if they could only play the mostly popular repertoire that could be listened to for a few pennies in the coin-operated machines available in arcades, train stations and phonograph parlours.

In what follows, I argue that Italian immigrants and their descendants in the USA placed Italian opera at the core of a music-based project of social and political empowerment, in large part as a consequence of the promotional strategies adopted by recording companies to advertise the phonograph as a respectable musical instrument for the middle class at the beginning of the new century. At the same time, I inscribe Italian opera in a genealogy of stereotyping and self-representation involving Italian immigrants and their relationship with musical machines. As I show in the concluding section, while the spread of the home phonograph contributed to the decline of Italian organ grinders, it also helped to cement a connection between opera and Italian identity in the minds of both Italian immigrants and non-Italian observers. It is precisely this association that would lay the musical foundations for a distinctive Italian American identity in the 1920s.

In her recent analysis of the cultural significance of opera in 1920s Britain, Alexandra Wilson presented this genre as a ‘battleground’ in which attempts to democratise access to opera clashed with anxieties concerning opera's cultural legitimacy at a time when this music became increasingly accessible.Footnote 9 Similarly, in the early twentieth-century USA, as recording entrepreneurs were promoting Italian opera as a ‘middlebrow’ cultural product – one, that is, that was increasingly accessible to the masses while retaining the cultural legitimacy that had long been assigned to this repertoire – the cultural meaning of this music inevitably shifted. These shifts depended on the use to which Italian opera was put by different groups as each attempted to fulfil their desires or pursue their political agendas. While most phonograph owners took pleasure in partaking in the consumption of a genre that had long stayed out of their financial reach, critics of recording technology were sceptical of the recording labels’ use of opera as a Trojan horse to boost the sales of musical machines whose educational value had yet to be proved. In the meantime, Italian Americans, like other disenfranchised groups living at the time or in the future – from queer audiences and women to immigrants and listeners of colour – projected themselves on opera and its vocal stars, until their emotional attachment to this music came to be seen from the outside as an integral part of their own identity.Footnote 10

Italian street musicians and the racialisation of musical machines

Invented by Thomas A. Edison in 1877, the phonograph had to wait more than two decades before it could be widely advertised as a viable instrument for domestic entertainment. Developed as an aid for dictation and telegraph transmissions, the phonograph immediately stirred the curiosity of scientific journals and popular magazines. Already in 1879, however, interest in the machine was fading, and Edison himself redirected his efforts towards the creation of a new system of electrical lighting. Only at the end of the following decade did the commercialisation of the phonograph become possible, thanks to the introduction of two alternative recording formats: the wax cylinder, presented by Alexander Graham Bell and his Volta Laboratory in 1886, and the disc, patented by Emile Berliner the following year.Footnote 11

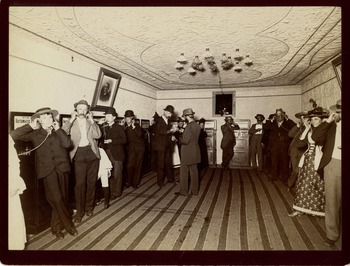

Coin-operated machines represented the first commercial outlet for the new medium. In November 1889, Louis T. Glass, the manager of the Pacific Phonograph Company, installed the first two automatic phonographs in San Francisco's Palace Royale Saloon. Each machine consisted of a phonograph that could hold only one cylinder at a time, equipped with special listening tubes. Glass's devices proved extremely profitable: in fewer than six months, each of the two machines generated more than $1,000 in nickels. The success of the machine would soon bring more investors into the business. In the early 1890s, coin-operated phonographs began to appear in busy public places across the country, including saloons, train stations, hotels, circuses, shopping districts and amusement parks.Footnote 12 By 1906, according to The Talking Machine World, no café, hotel, park or skating rink would be considered ‘complete’ without automatic phonographs.Footnote 13 Encouraged by the popularity of ‘coin-ops’, entrepreneurs in numerous cities also opened special ‘phonograph parlours’ such as the one shown in Figure 1, where patrons could move between different machines to listen to the musical selections available.

Figure 1. A phonograph parlour, probably 1895. Thomas Edison National Historical Park, West Orange, New Jersey.

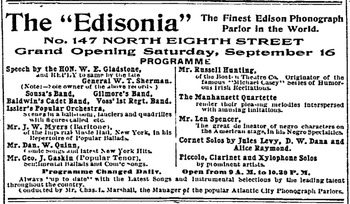

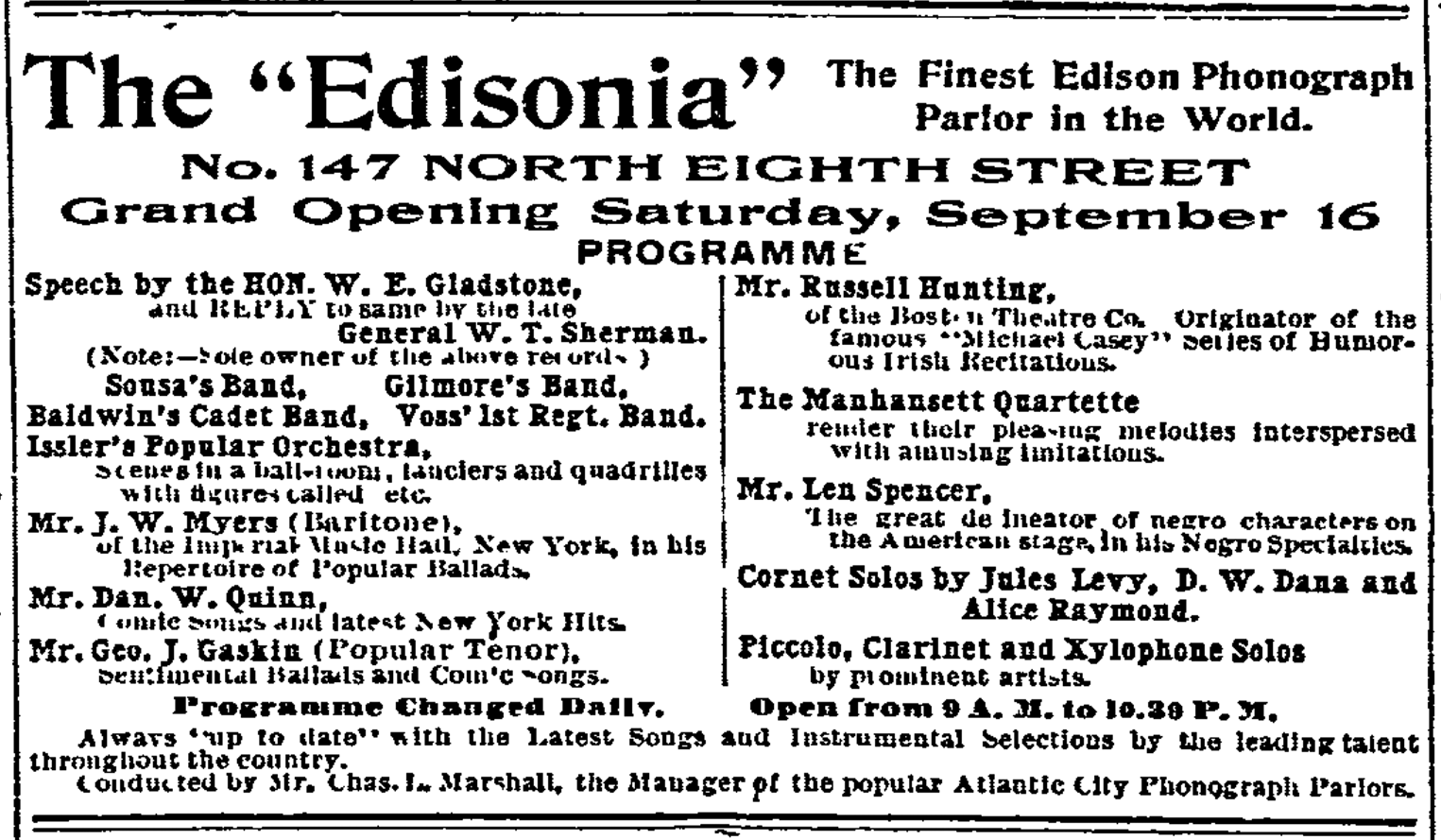

An advertisement from Philadelphia offers a glimpse into the musical repertoire available in phonograph parlours. Opened in the city's commercial district by Charles L. Marshall, manager of the Atlantic City Phonograph Parlor, the ‘Edisonia’ offered a rotating selection of band music, popular songs, instrumental music and political speeches. The programme for the opening day in September 1893, for example, included recordings of Patrick Gilmore's and John Philip Sousa's bands; songs performed by the well-known singers John W. Myers, Dan W. Quinn and George J. Gaskin; comic and minstrel numbers performed by Len Spencer; speeches by General William T. Sherman and British prime minister William E. Gladstone; and cornet, piccolo, clarinet and xylophone solos (Figure 2). Sherman's and Gladstone's speeches were probably meant to demonstrate the capacity of the new medium to capture the voice of historical figures both alive and dead (Sherman had passed away in 1891). The musical selections reflected the taste of the time, but they were also influenced by the technical limitations of acoustic recording, which, as we have noted, privileged loud instruments and voices over softer ones, and poorly served instruments such as the piano and violin. This was the same musical repertoire that contemporary labels such as Columbia – established in 1887 – began to market to private phonograph owners in the early 1890s.Footnote 14

Figure 2. The musical programme for the opening day of the ‘Edisonia’ phonograph parlour in Philadelphia (The Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 September 1893). ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Philadelphia Inquirer.

In these years, phonograph manufacturers, including Edison himself, became increasingly convinced of the potential that the new medium had for in-home reproductions of ‘all that is best in oratory and music’.Footnote 15 Some obstacles, however, complicated the marketing of the phonograph for these purposes. First of all, the mostly popular repertoire chosen for early records could not live up to the quality and educational standards necessary to make the phonograph a credible vessel of cultural refinement for the middle class. As David Suisman has observed, many contemporary reviewers saw popular songs as ephemeral products with limited musical value, especially in comparison with opera and symphonic music.Footnote 16 The popularity of coin-operated phonographs, and the lowly venues in which they were located, aroused suspicions about the respectability of the new machine.Footnote 17 More generally, at a time in which the commercial and artistic possibilities of phonographs still had to be explored, these machines did not look too dissimilar – at least, to the eyes of some middle-class observers – from other automatic attractions that had been presented in dime museums during the previous decades.Footnote 18

As musical devices employing a revolving reproducing mechanism, early phonographs, as well as piano players, were seen as part of a genealogy of musical machines stemming from another instrument that was strongly associated with the working class: the barrel organ.Footnote 19 In 1898, an article from The Music Trade Review fully described this lineage of musical machines. Its author explained that whereas until a few years earlier ‘the domain of those who earned a living by employing their arms to turn some mechanical box of whistles was chiefly confined to the low class of Italian’, the hand organ had recently seen an ‘evolution into higher forms’. The question remained, however, whether the lowly social connotation of the barrel organ would jeopardise the acceptance of its technological descendants in upper-class homes. As the article's author put it:

We possess pianos to play our studies for us; machines to give us the latest song sung by the most favored artists; organs guaranteed to do quite as well as the finest living organists, and instruments to play for our sole delectation what the finest orchestra is just playing at such an immense cost to crowds. Many of these automatic musical instruments are finding a ready introduction into our homes – the legitimate cradle for our future race of art-lovers – and their status cannot be readily shelved. What is going to be the result of these interlopers on the musical future? Will their alien origin encourage or will it stultify the growth of the natural plant? … Are these visitors at the houses of the rich to be regarded as friends or foes?Footnote 20

The article starkly presented the cultural and racial anxieties that phonograph and mechanical piano manufacturers had to overcome in order to create a market among the upper classes. If these machines were to be welcomed into the houses of wealthy ‘art-lovers’, not only must their reputation as cheap forms of musical entertainment be disproved, but the historical connection with their ‘alien’ progenitors – to wit, foreign-born street musicians – needed to be erased.

At the turn of the century, phonograph and mechanical piano makers responded to these concerns by crafting special promotional campaigns aiming to elevate the cultural status of their products. As I will show in the next section of this article, this strategy benefited from the increased availability of opera and instrumental selections: once customers could buy recordings of celebrated opera singers or rolls of favourite symphonic works reduced for the piano, the educational potential of the new musical machines became harder to question. As the cultural legitimacy of phonographs and player pianos grew, music trade journals began to portray street musicians as struggling to keep up with the expectations of increasingly sophisticated audiences. By 1905, according to The Talking Machine World, the appearance of the player piano, and later of the phonograph, had so much improved audiences’ musical taste that the old hand organ had been relegated to the status of mere ‘curiosity’.Footnote 21 Some organ grinders tried to retain their thinning clientele by adding short circus or acrobatic numbers to their musical performances.Footnote 22 Others installed portable phonographs on pushcarts. In January 1906, describing one of these strolling phonographs that would begin operating in Chicago, The Music Trade Review explained that it would take ‘two Italians to operate this instrument, one to extend the open palm and the other to adjust the records’.Footnote 23

Italians were not the only ethnic group that found employment in the street music trade. In 1893, for example, The Philadelphia Inquirer mentioned Irish fiddle players, German street bands and African American accordionists among the three to four thousand street musicians working in the city.Footnote 24 Italians, however, were especially associated with the profession in the contemporary press, not only because of their number – according to the Inquirer article mentioned above, they were the most represented nationality – but also as a consequence of the decades-long presence of Italian organ grinders, harp players, accordionists and violinists in both urban and rural areas of the country. While some street musicians belonged to well-established musical traditions handed down along family lines – such as, for instance, the harp players from the Viggiano area, in what is the modern-day region of Basilicata – many Italians entered the profession after their arrival in the USA.Footnote 25 In 1882, Henry Taylor, a hand-organ maker of German descent operating in the Bowery neighbourhood in New York, revealed to the press that his factory mostly did business with local intermediaries in the Italian quarter of the city, who in turn sold their instruments to newly arrived immigrants in exchange for a share of their profits over several years of work.Footnote 26

As was the case of street musicians working in other countries in the same years, Italian organ grinders in the United States did not enjoy a good reputation.Footnote 27 At least since the 1850s, Italian travelling artists in several cities had been routinely involved in or accused of multiple crimes, including illegal voting during local elections, child trafficking and close links with the Mafia.Footnote 28 Over the second half of the century, the increasing presence of Italian street musicians in crime news lent itself to stereotyping practices, and Italian organ grinders became a common presence in comedies and minstrel shows.Footnote 29 Organ grinders occasionally appeared also in offensive cartoons caricaturing Italians and their political leaders. In April 1891, for example, a Philadelphia newspaper depicted King Umberto I of Italy, Italian prime minister Antonio Starabba di Rudinì, and Italian ambassador to the USA Saverio Fava as peanut vendor, organ grinder and monkey, respectively, after US Secretary of State James G. Blaine rejected the Italian government's request for reparations to the families of the Italian victims of a mass lynching that had occurred in New Orleans the previous month (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Italian prime minister Antonio Starabba, Marchese di Rudinì, the Italian Ambassador Saverio Fava and King Umberto I as caricatured in The Philadelphia Inquirer, 12 April 1891. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Street musicians, however, also played an important social function, as they offered working-class audiences – who usually only had a chance to hear music at parades and other public ceremonies where bands played – the opportunity to hear music on a daily basis. In the 1880s and 1890s, while several city administrations proposed to limit the presence of street musicians on the grounds of their contribution to noise pollution, many protested that the new laws would deprive many of music.Footnote 30 For example, in 1890, the Philadelphia newspaper The North American launched a public campaign against a recent ban on street musicians, on the grounds that ‘a swarthy son of Italy, with or without a monkey’, was for thousands of citizens the only way to be exposed to the music usually played in opera houses and concert halls.Footnote 31

The adjective ‘swarthy’ was frequently employed in the English-language press with reference to darker-skinned immigrants from the south of Italy, and it clearly worked as a marker of racial difference at a time when Italian immigrants from different regions were beginning to be classified in different racial categories in official censuses.Footnote 32 When applied to Italian street musicians, however, similar expressions took on additional meanings, as they reminded the mostly middle-class readers of mainstream papers of the social, racial and cultural distance that existed between them and the intended audience of organ grinders. Such impressions were further reinforced by the reference to monkeys, which implicitly put organ grinders, their musical instruments and their working-class clientele on a lower level of the evolutionary scale. By the early 1890s, depictions of racial difference between street musicians and the middle class were commonplace in the mainstream press. As early as 1872, the popular New York magazine Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper published a racist cartoon captioned ‘The Darwinian Theory Illustrated – A Case of Natural Selection’. The picture depicted the monkey accompanying an organ grinder attacking an African American child, while other bystanders watched the scene (Figure 4).

Figure 4. This cartoon appeared on the first page of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 27 April 1872. The full caption at the bottom of the image reads: ‘Virginia – A scene in the streets of Richmond – The Darwinian theory illustrated – A case of natural selection – From a sketch of W. L. Sheppard.’ William Ludwill Sheppard (1833–1912) was a popular painter and illustrator from Richmond, Virginia.

Aware that they were incapable of escaping the racial, cultural and social categories fabricated by their host society, political leaders active in Italian communities adopted different strategies to deal with the issue of the Italian street musicians. Until the 1880s, when the criminalisation of street musicians was most evident in the press, Italian prominenti (prominent leaders) in many American cities explicitly condemned street musicians and organ grinders, in some cases even calling for a ban on the profession.Footnote 33 Beginning in the late 1880s, however, the gradual replacement of street organs with the more sophisticated mechanical pianos (which allowed for richer harmonies and more stable tuning) led to a reversal of this position, as Italian leaders strove to protect the interests of their many fellow countrymen in the street music trade.Footnote 34 In some cases, street musicians also attempted to rehabilitate their image by intervening on the selections that they played. In 1904, for example, the Italian organ grinders of Philadelphia constituted the ‘United and Amalgamated Order of Street Organ and Hurdy-Gurdy Players of Philadelphia, Camden, Norristown and Vicinity’ with the explicit purpose of improving the quality of organ grinders’ musical selections. The official censor of the organisation, Antonio Amodei, was a linguistic interpreter in the city courts and a respected member of the local Italian community. In an effort to develop a ‘taste for good music’ in all social classes, Amodei prepared a blacklist including many popular songs and genres, including ‘Little Annie Rooney’, ‘After the Ball’, ‘The Bowery’ and the whole ragtime repertoire, all of which he thought should be substituted with ‘grand opera and classical pieces’.Footnote 35

Amodei explained that some of these songs were excluded because of their outdatedness: although evergreens such as ‘The Sidewalks of New York’ or ‘The Old Oaken Bucket’ remained popular with working-class audiences, the censor believed that such songs were contributing to ‘keeping the children ten years behind the times’. Ragtime, on the contrary, was in its heyday at the time, but Amodei still found it to be ‘horrible’, in line with white, mainstream opinion on this genre. Inevitably, the most effective way to demonstrate the educational value of Italian street musicians was to bar from their repertoire what the contemporary English- and Italian-language press regularly presented as the opposite of Western art music. In fact, as Karen Ahlquist has recently observed, ragtime was the genre most often excluded from the educational programmes of musical progressives in turn-of-the-century schools, settlement houses and community organisations, both because of the music's origins in African American culture and because of its association with the popular music industry.Footnote 36

Making opera visible

Amodei's attempt to elevate the cultural status of organ grinders was consistent with the marketing strategies developed by phonograph manufacturers in those same years. While the recording industry continued to market popular music at the beginning of the new century, it capitalised on Western art music, specifically opera, to advertise the device as a respectable musical machine for domestic use. Because advertisements systematically associated the phonograph with Italian opera, the phonograph offered Italian immigrants a unique opportunity to elevate themselves from a marginalised status towards a higher degree of social acceptance. At the same time, opera supported the efforts of recording entrepreneurs to break any possible link with previous musical machines and their racial and social connotations. In 1906, for instance, The Talking Machine World recommended that record dealers remind their customers of the educational value of the phonograph, which should be advertised as ‘a wholly different instrument’ from the ‘scientific novelties’ of the early days. The main merit of the phonograph, according to the journal, was to have ‘acquaint[ed] thousands of people with the works of great composers’ – which, given the limited presence of symphonic music in contemporary record catalogues, meant first of all opera composers.Footnote 37

In order to fully appreciate the political significance that Italian opera came to acquire in Italian communities in the early twentieth century, it is worth examining how pervasive home phonographs (that is, the medium that was especially responsible for reviving the interest in Italian opera) became in American popular culture thanks to the marketing campaigns devised by recording companies’ advertising departments in those years. As I show in this section, not only did recording entrepreneurs distance their products from barrel organs and other musical devices available in the streets; they also drew upon advertising strategies that in previous decades had been successfully applied to musical instruments and forms of entertainment (such as mechanical pianos and stage drama) specifically catering to middle-class audiences.

In March 1903, the Victor Talking Machine Company issued its first catalogue of Red Seals, a new line of opera records featuring some of the famous singers of the day.Footnote 38 Initially pressed from matrices imported from Europe, the Red Seals were recorded in the USA beginning in 1904, first in New York and then in the new Victor plant erected in Camden, New Jersey. Victor was not the only company to invest in opera records in these years. Also in 1903, within weeks of Victor's announcement of their Red Seals, Columbia announced its Grand Opera Records series, also bearing red labels. Edison Records, which had been releasing opera records since the late 1890s, launched its own Grand Opera line at the end of 1905. European companies such as Pathé also imported opera cylinders at the beginning of the century, although these records had a limited circulation in comparison with those produced by US-based manufacturers.Footnote 39

Among all of these companies, however, Victor emerged as the leading producer of opera records. Victor's success can be explained by a combination of the technology it used and its adoption of bold promotional strategies. While Victor recorded on disc, other companies, including Edison and Pathé, opted for the cylinder, a format that allowed for an even shorter recording time, and which forced manufacturers to make aesthetic choices – such as the abridgement of opera arias, or the adoption of faster tempi – that negatively affected the final quality of the product. On the other hand, at a time when companies such as Edison advertised the sound quality of their products rather than the prestige of their artists, Victor launched an aggressive marketing campaign leveraging the names and images of its opera stars to improve the cultural status of its phonograph and records.

By 1906, opera stars such as Enrico Caruso, Adelina Patti, Nellie Melba, Marcella Sembrich, Pol Plançon and Antonio Scotti recorded for Victor on an exclusive basis.Footnote 40 Victor sold its Red Seals at a higher price than the other records in its catalogues. In 1909, the price of a regular 10- or 12-inch Victor ‘Black Seal’ record ranged from $0.60 to $1.25, depending on its size and on whether it was single- or double-sided. On the other hand, Red Seals – always printed on just one side – sold for a price ranging from $1 to $7. The most expensive record was the sextet ‘Chi mi frena in tal momento?’ from Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor. First released in 1908 in a version starring Sembrich, Caruso, Scotti, Gina Severina, Marcel Journet and Francesco Daddi, the prestigious ‘Seven-Dollar Sextet’, as it was soon nicknamed, was sold at a price that was equivalent to about $240 in 2021.Footnote 41

Victor's price policy helped the company by creating an aura of prestige around its Red Seals – and, indirectly, opera singers and (to lesser extent) composers. As David Suisman has observed, while Victor managers claimed that the higher retail price of the Red Seals was determined by the expensive recording fees required by famous opera artists, this price was artificially inflated by the company to increase the cultural capital associated with these records in the eyes of the upper-class clientele who could afford them. Eldridge Johnson, the founder of Victor, was convinced that once his phonographs entered into the homes of the American middle class, the social and cultural prestige accorded to the machine would boost sales among every social class.Footnote 42 If, as Karen Henson as shown, technology – from mass printing to telegraphy and photography – had played a crucial part in the marketing of music and the construction of operatic stardom since the Industrial Revolution, Johnson reversed the terms of the equation and leveraged the celebrity of the ‘message’ (the contemporary opera stars) to assert the legitimacy of the new medium (the phonograph and recorded music).Footnote 43

Victor's advertising strategy proved effective. By marketing phonographs as a respectable ‘musical instrument’ that could legitimately find its place in the homes of respectable Americans, the company managed to improve the cultural status of the technology.Footnote 44 Not only did this translate to the commercial success of Red Seal records, but it also increased sales for the popular repertoire marketed under the regular ‘Black Seal’ section of the catalogue. While Victor's advertisements rarely mentioned the cheaper and more numerous non-operatic records pressed by the company, these records still indirectly benefited from the prestige that opera – and its mostly middle-class listeners – bestowed upon the phonographic medium.Footnote 45

The limited presence of non-operatic records in Victor's advertisements reflected the company's ambition to craft marketing campaigns that lived up to the cultural capital of the Red Seals. Of course, Victor's first goal was to make its products visible to every social class: they bought advertising space in a wide range of rural and urban papers, distributed promotional cards in street cars, and mounted gigantic versions of its iconic Nipper logo on billboards and even on specially installed stained glass windows decorating the tower of the company's plant in Camden and visible from Philadelphia on the other side of the Delaware River.Footnote 46 In the same years, Victor, like other recording companies, also sought to sell its products to public schools to be used in music appreciation classes or for purposes of cultural assimilation for immigrant students. But beyond sheer visibility, what ultimately mattered for the success of Victor's ‘high class advertising scheme’ – as William Barry Owen, president of the Gramophone Company, once described it – was the discernibility of the cultural hierarchy that underpinned it.Footnote 47

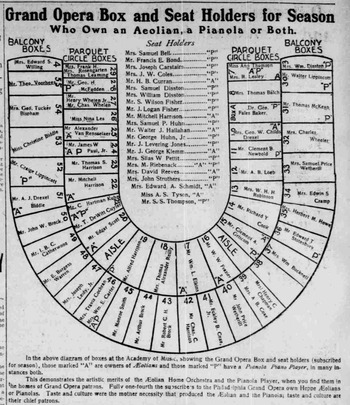

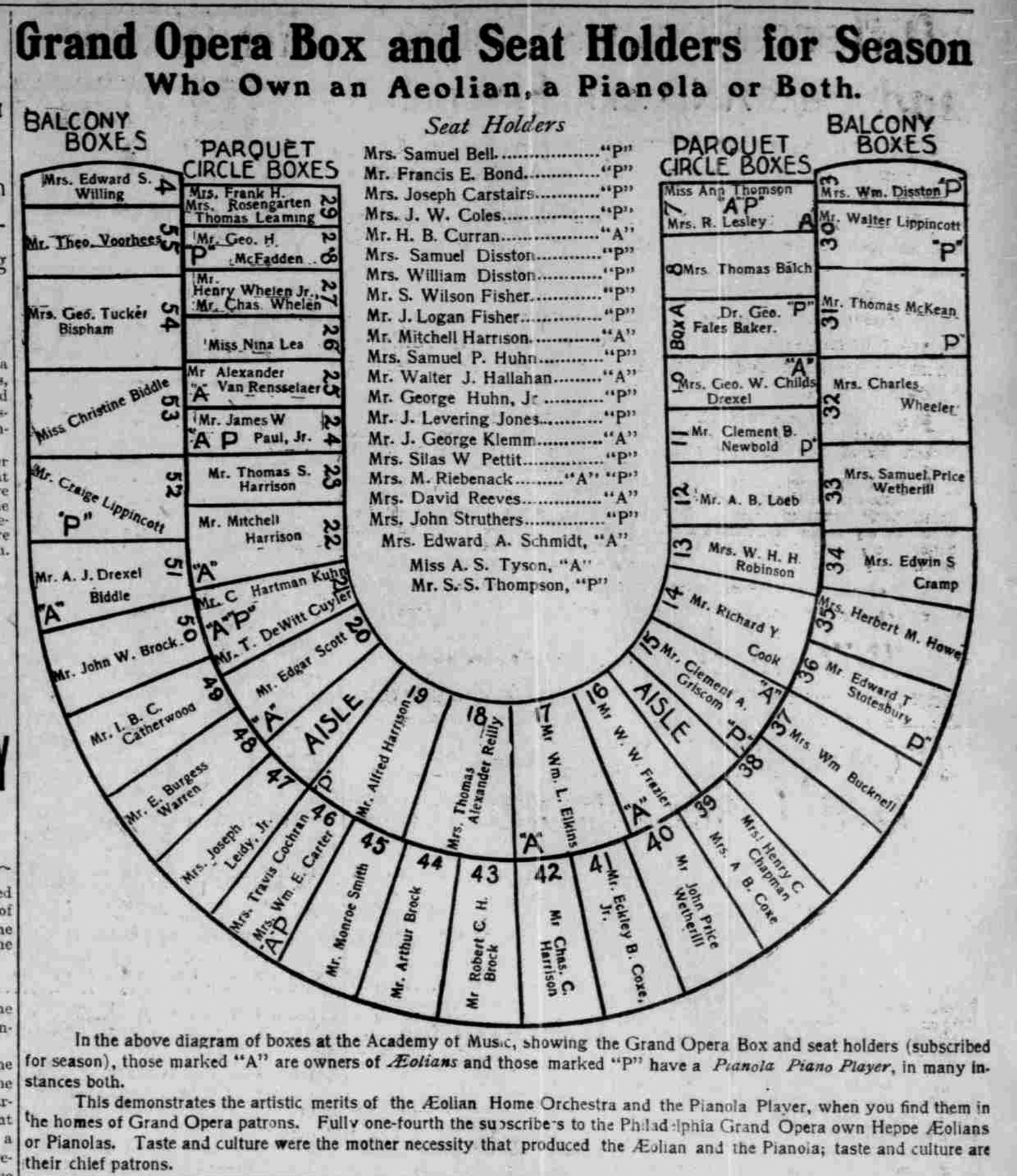

Victor crafted its middle-class oriented marketing campaign in line with a long tradition of advertisement of musical instruments. In the 1890s, the piano industry was among the largest spenders of advertising money in the USA. For decades, piano and organ manufacturers had increased the prestige of their instruments by routinely associating them with European celebrity performers and sponsoring American tours of pianists such as Arthur Rubinstein and Hans von Bülow. At the turn of the twentieth century, new musical instruments such as the autoharp and the piano players were still praised in advertisements for their capacity to allow performers to play classical music on them.Footnote 48 Advertising firms made sure that anybody reading newspapers was informed when those new instruments became fashionable among the upper classes. In 1902, for example, C.J. Heppe & Son, exclusive distributor for the Aeolian organ company in Philadelphia, caused a sensation with the bold style of one of its advertisements (Figure 5). In its top portion, the advertisement reproduced the box seat chart of the Philadelphia Academy of Music, complete with the names of the seat holders for that season. Next to some of these names, special letters indicated the model of piano players that they had purchased. A caption proclaimed that ‘Fully one-fourth the subscribers to the Philadelphia Grand Opera own Heppe Aeolians or Pianolas’, and that if ‘taste and culture’ made possible the very existence of the instrument, then it was only natural that the sophisticated audiences of the Academy were the piano player's main patrons. The implicit message was, of course, that simply owning the instrument would suffice for consumers to have access to the same degree of cultural refinement.

Figure 5. A portion of an advertisement card published in 1902 by the Philadelphia piano store C.J. Heppe & Son. The advertisement shows a diagram of the box seats at the Philadelphia Academy of Music, including the names of the subscribers for the opera season. The letters ‘P’ and ‘A’, located next to some of these names, refer to the model owned by each subscriber. ‘P’ stands for Pianola, a detachable push-up player piano that could activate the keys of a regular piano through special felt-covered fingers. ‘A’ indicates the Aeolian Home Orchestra, a piano reed organ that could imitate the timbre of different instruments through special ‘stops’ placed on the front of the instrument. From The Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 December 1902. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Philadelphia Inquirer.

The commercial placement of the gramophone – the disc phonograph patented by Emile Berliner that would later be improved and sold by Victor – followed the same trajectory towards cultural legitimacy. In the early 1890s, when disc phonographs were still operated by hand, they were regarded as not much more than a technological curiosity with an uncertain future.Footnote 49 Things begin to change in 1896, when Eldridge Johnson, then an engineer who owned a repair shop in Camden, developed a spring motor to be used in Berliner's phonographs. The new motor allowed for a better-sounding machine, which in turn encouraged new recordings. Convinced of the ‘desirability of making good music available on records’, as Victor company historian Benjamin L. Aldridge wrote in the 1950s, Berliner and his collaborators secured the performances of celebrated opera singers of the day, including Spanish American bass Emilio De Gogorza and Ferruccio Giannini, an Italian tenor who had recently relocated to Philadelphia.Footnote 50

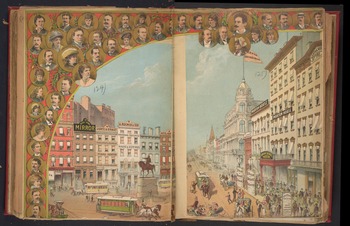

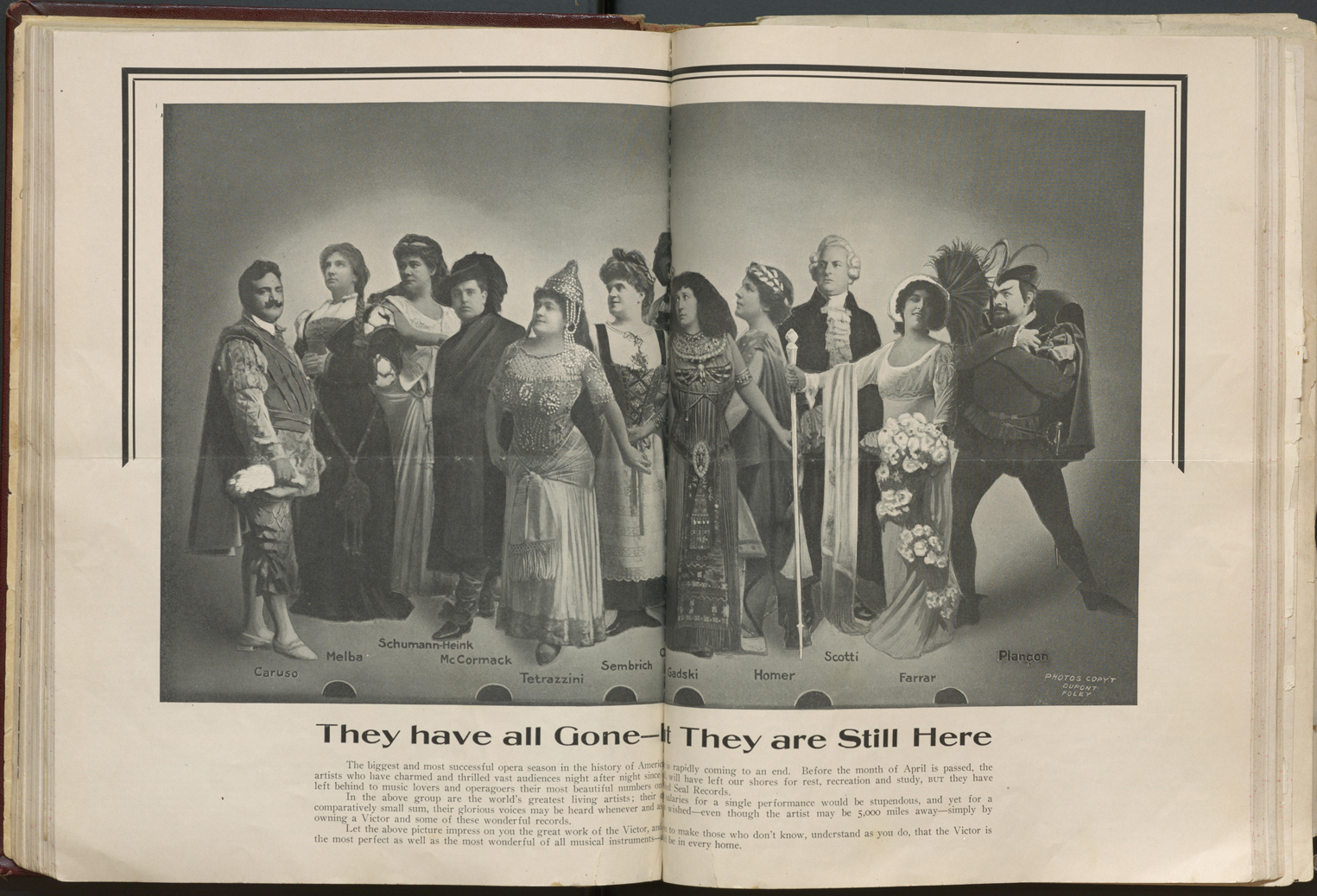

In 1900, Johnson bought the rights to Berliner's patents, and in October of the following year the Victor Talking Machine Company was formally organised. With the appearance of the Red Seals on the American market in 1903, Victor began to consistently feature in its advertisements portraits of the famous singers recording for the company. As Richard Leppert has observed, these advertisements – which monopolised the promotional materials produced by Victor in these years – were carefully tailored along class and gender lines, and unfailingly assumed that their audience was made up of opera lovers.Footnote 51 Regardless of their cultural and social background, those who encountered these advertisements were presented with a visual iconography that was borrowed from late nineteenth-century theatrical magazines and ephemera primarily catering to the American middle class, and freely adapted to the new medium. A clear example of this can be seen in Figures 6 and 7. In the poster advertising the Cincinnati Dramatic Festival of 1883 shown in Figure 6, some celebrated theatre performers of the day are depicted in costume as they impersonate their most popular stage characters. An almost identical layout can be found in Figure 7, which shows a Victor advertisement from 1910 featuring Enrico Caruso, Nellie Melba, Ernestine Schumann-Heink, Luisa Tetrazzini, Marcella Sembrich and many other opera stars in the company's roster. While reverting to established visual styles helped to dissolve possible suspicions about the new mechanical medium, Victor's advertisement also conveyed a different kind of message: although only a few could afford to see famous opera singers performing live on stage, the phonograph democratised access not only to the artistry of those singers but also to the cultural and social capital associated with what they sang (that is, opera).

Figure 6. A poster advertising Cincinnati's Dramatic Festival of 1883. From vol. 2 of the ‘Theatricals in Philadephia’ scrapbooks, 1838–1936, Ms. Coll. 1384, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 7. A Victor advertisement from The Voice of the Victor, March–April 1910. National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, Library of Congress.

Record stores were perhaps the most effective supporters of Victor's promotional efforts. At the turn of the twentieth century, music stores in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and other large US cities began to introduce the so-called ‘talking machines’ alongside pianos and other musical instruments. In music stores such as Heppe's in Philadelphia or Sol Bloom's in New York, visitors could listen to the records of their choice, carefully selected and handled by knowledgeable staff members, while sitting in luxury armchairs surrounded by ferns and phonographs on display. In 1910, Heppe's even built special rooms on the fourth floor of the store, to be used ‘for the accommodation of male visitors who desire to hear records and enjoy a smoke at the same time’.Footnote 52 The general clientele, including the many female purchasers of records and phonographs, could listen to records in the luxurious (and non-smoking) talking machine rooms located on the store's first floor.Footnote 53

In the same years, department stores launched a series of activities to boost the sales of their talking machines. The most active of these was Wanamaker's. In 1909, the department store began to circulate a new journal, Opera News, to its customers, a publication which provided the cast details and plots of the main productions included in the current opera seasons in New York and Philadelphia, accompanied by a list of the corresponding Victor records that could be bought in the store.Footnote 54 Wanamaker's also invited notable musicologists, including Henry Edward Krehbiel, the long-time critic of the New York Tribune, to give public lectures on opera.

The most remarkable among the musical promotion initiatives organised by Wanamaker's in its stores, however, was represented by the grandiose phonographic concerts that the firm launched in 1908. These concerts took place on a daily basis in large, opulent halls specifically designed to attach a sense of prestige and respectability to the music.Footnote 55 A live orchestra regularly accompanied the recorded voices of the great singers of the day. Not only did this aspect of the concert help to partially dissolve the alienating effect that listening to an empty stage may have had on audiences, but it also elevated the phonographic medium to the same level of cultural legitimacy and social respectability granted to live performances of the same recording artists in contemporary opera houses.

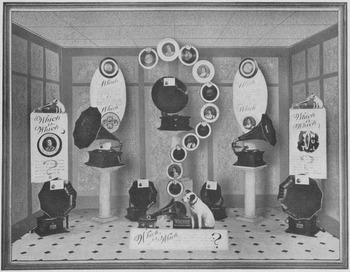

Even for those who did not dare to venture into luxurious music shops and department stores, it was nearly impossible to escape the fascinating window displays showing the latest records and phonographic equipment. Recording companies were aware of the importance that opera seasons had in stimulating record sales, and they instructed local dealers on how to capitalise on this by arranging their windows around the main artists or titles featured in the local theatres.Footnote 56 In 1908, in an attempt to achieve greater control over the window displays exhibited across the country, Victor hired Ellis Hansen, a talented window dresser from San Francisco, and put him in charge of a new department dedicated to the production of ready-made displays.Footnote 57 At a time when phonographs were sold as a sideline in many smaller general stores, the idea proved immensely successful, as it allowed dealers with little financial resources to nevertheless set up captivating displays for their clientele.

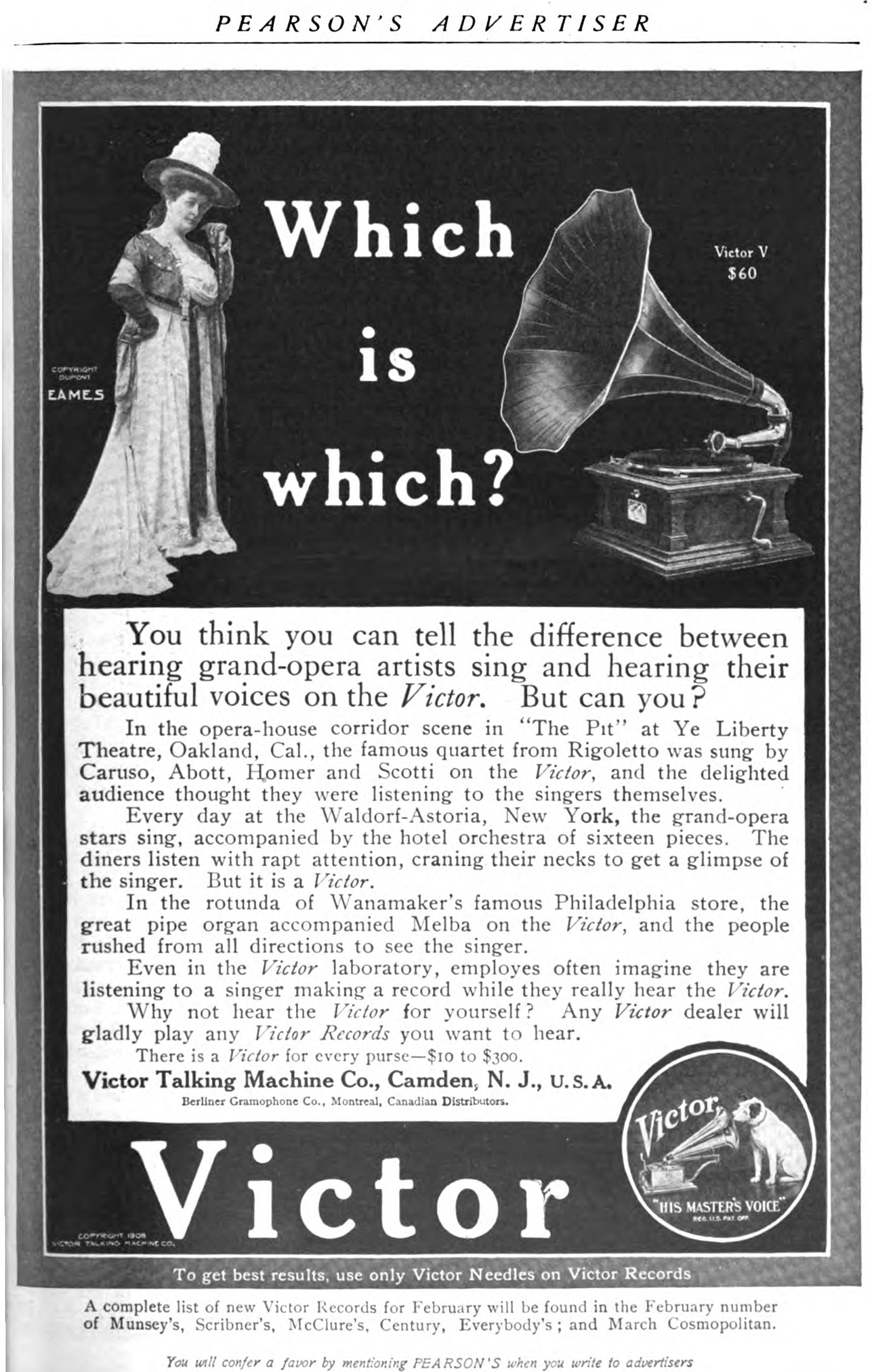

Not only was the sparse visual organisation of Victor's ready-made displays instrumental in capturing the attention of urban passers-by – an advertising strategy informed by what J. Martin Vest has recently called an ‘aesthetic of arrest’ – at a time when they were bombarded by a relentless whirlwind of sonically and visually mobile information, but those displays made the prestige associated with recorded opera transferrable to the most disparate social settings, and visible as a symbol of cultural legitimacy.Footnote 58 Once more, the aesthetic of ready-made displays clearly derived from late nineteenth-century models. A closer look at one of the window displays prepared by Victor in 1909 illustrates the thin line between continuity and change on which the company built its advertising strategy (Figure 8). The display was modelled on the popular Victor motto ‘Which is Which?’ used in many contemporary Victor advertisements to invite its customers to tell the difference between the live and the recorded voice of a given artist (Figure 9). In the display, a large question mark made up of records and circular portraits of opera stars was placed at the centre of the window, surrounded by banners with the ‘Which is Which’ slogan and the unavoidable reproduction of Victor's dog Nipper. Similar compositions of circular portraits were commonly found in theatrical advertisement from the turn of the century, where pictures of famous actors and singers decorate programmes or images of the performing venue. Figure 10, for example, shows a poster printed by the New York Union Square Theatre in the 1880s. In the poster, a large image depicting the bustling street facing the theatre is surrounded by dozens of portraits of actresses and actors who performed on that stage. By building its window displays and its other promotional material on pre-existing visual aesthetics, Victor appropriated the ideal of cultural legitimacy associated with contemporary theatre and claimed cultural and symbolic equivalence between the old medium (live stage performance) and the new one (opera records). The presence of Victor's imagery in newspaper advertisements, street car cards, road signs and window displays made the cultural capital of recorded opera visible, and thus potentially appealing, to anyone who came across the message.

Figure 8. A ready-made window display inspired by Victor's popular slogan ‘Which is Which?’ From The Voice of the Victor, September 1909. The New York Public Library, retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/4f8dcf10-37f5-0139-1f6e-0242ac110003.

Figure 9. Victor advertisement featuring American soprano Emma Eames and the ‘Which is Which?’ slogan. From Pearson's Magazine, February 1909. Original from Princeton University.

Figure 10. A poster advertising the Union Square Theatre (New York City), possibly early 1880s. From vol. 1 of the ‘Theatricals in Philadephia’ scrapbooks, 1838–1936, Ms. Coll. 1384, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania.

Caruso, the Italian star

The use of Italian opera stars in record advertisements had important consequences for both the commercialisation of home phonographs and the reputation of Italian immigrants and their descendants in the USA. Enrico Caruso, Luisa Tetrazzini, Francesco Tamagno, Antonio Scotti, Adelina Patti and many other Italian and non-Italian singers appearing in Victor advertisements gave immediate prestige to both hardware (the phonograph) and software (the records), and implied equivalence between live and recorded voice.Footnote 59 But it was Enrico Caruso with whom the company most assiduously chose to associate its name. Caruso's name and image were so often used in Victor's advertisements that it almost became shorthand for the company in the minds of its customers. The company's management encouraged this association and pushed local dealers to keep using the name of Caruso to increase their sales.Footnote 60

Caruso himself hugely benefited from his association with recording technology. As Alan Sutton has observed, Caruso was relatively unknown in America until his 1902 debut in Rigoletto at Covent Garden.Footnote 61 As soon as it became known that Heinrich Conried, the manager of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, had secured Caruso's performances for the 1903–4 season, record dealers across the country began to promote his records. In June 1903, for example, an advertisement from the Philadelphia Wanamaker's invited its customers to ‘hear Italy's greatest tenor, Sig. Cav. Enrico Caruso, even before he makes his first tour to this country’.Footnote 62 In February 1904, fewer than three months after his successful Metropolitan Opera debut, Caruso recorded for Victor favourite arias from most of the operas – including Aida, Rigoletto, Tosca, Cavalleria Rusticana, Pagliacci and L'elisir d'amore – in which he performed during that season, and until his death his operatic records continued to match his Met repertoire.Footnote 63 During those years, the adoption of Caruso's name for the promotion of Italian opera was incredibly effective not only for recording companies but for opera managers as well. Verdi's Rigoletto, which had only been staged 37 times between the opening of the Met in 1883 and Caruso's debut at that theatre, would be performed 60 more times between 1903 and 1920 (more than half of which featured Caruso in the cast); Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, Caruso's most-often performed opera at the Met (more than 110 appearances) and undoubtedly the work with which the Italian singer was most famously associated in contemporary popular culture, was staged more than 160 times during his tenure at the theatre; and Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, which debuted at the Met in November 1903 with Caruso in the cast, would be programmed on 40 more occasions (all of which starred the Italian singer) by the end of 1920.Footnote 64

Recording technology was responsible for the earliest and most evident instance of what Gavin Williams has recently termed ‘the reproduction of Caruso’, that is, the process through which different media made possible the replication of the singer's voice and his body and their circulation through various means.Footnote 65 During Caruso's career, Williams argues, this same process was also enabled by film – in particular, the silent film My Cousin (1918), in which Caruso played the parts of both the protagonist, an opera star, and his look-alike cousin – and by Caruso's well-known work as an amateur caricaturist and sculptor. Intriguingly, Williams shows that the replication process enabled by these media was responsible for a racially connotated split between Caruso's voice and his physical appearance, whereby the former indexed the fashionable, cosmopolitan opera star, and the latter the lowly Italian newcomers to whom Caruso was tied by ‘biological relation’.Footnote 66

And yet, in the eyes of some contemporary writers, both Caruso's art as a singer and his personal story could prove the desirability of working-class Italian immigrants. Writing in 1906, for instance, author Herbert N. Casson burnished the old image of Italy as the cradle of the arts and as the homeland of artistically gifted people in a sympathetic article about ‘The Italians in America’ that appeared in the New York-based Munsey's Magazine.Footnote 67 In Casson's opinion, ‘it is when we come to music and art that we find the fire of Italian genius burning most brightly’. To prove his argument, Casson listed a few musical figures known to his readers, including Pietro Mascagni, singers Antonio Scotti and Giuseppe Campanari, and conductors Giuseppe Creatore and Francesco Fanciulli. Casson's main example, however, was Caruso, defined as ‘the most brilliant among the stars of grand opera’.Footnote 68

Far from representing an obstacle to Casson's narrative, Caruso's ability to achieve international success despite his modest social origins only contributed to the author's positive view of the singer (and, indirectly, of Italian immigrants themselves).Footnote 69 Simona Frasca has recently observed that Caruso's experience as a ‘self-made man’ was a convenient counterexample to common stereotypes, functioning as proof of Italians’ will to improve their social status.Footnote 70 Indeed, Casson argued in his article that Caruso's rags-to-riches story was ‘typically American’, as was the ‘spirit of enterprise’ of Italian immigrants who ‘left the land of their fathers’, despite their emotional attachment to it.Footnote 71 In Casson's reasoning, this proactive attitude undermined old stereotypes often used against Italians: that they had no interest in assimilating into American culture, and that they caused an economic drain by sending their US earnings abroad.

Italian-language newspapers across the USA were quick to pick up on the symbolic importance of Caruso, and they regularly reported his triumphs and the generous compensation that he received for his performances and recordings. By October 1904, less than a year after his American debut, the San Francisco paper L'Italia hailed Caruso as ‘the greatest tenor in the world’ – a flattering title that glorified the name of the singer in the eyes of his compatriots, and which also coincided with the definition of Caruso proposed by contemporary Victor advertisements.Footnote 72 Caruso's debut at the Metropolitan Opera as the Duke of Mantua in Rigoletto also saw the appearance of other celebrated Italian artists such as Scotti and conductor Arturo Vigna, and the production appeared in several Italian papers as the beginning of a revaluation of Italian music in the United States. In February 1904, for example, the New York paper Bollettino della sera praised Caruso and the Metropolitan Opera impresario Heinrich Conried for having resurrected Italian opera after the predominance of German opera in previous years had cast out the ‘divine melodies’ of Verdi, Rossini and Donizetti as pieces of ‘junk’ (ferravecchi).Footnote 73 Four years later, the Metropolitan Opera appointed two Italians, Giulio Gatti-Casazza and Arturo Toscanini, to powerful positions in the company, the former as the new general manager and the latter as the conductor responsible for the Italian and French repertoire. This further stirred displays of national pride in the Italian-language press. Indeed, as Davide Ceriani has observed, the presence of Italian artists and managers in prominent operatic institutions, and the popularity of Caruso and other Italian singers with opera-goers and record listeners alike, recast Italian opera as a powerful political tool in the hands of the Italian-language press and the Italian political leaders in New York.Footnote 74

While Italians’ strategic adoption of opera for political purposes became especially evident at the beginning of the new century, it is worth examining why Italian immigrants and their descendants had not also apparently assigned Italian opera the same political role during the previous decades. After all, the genre had long circulated within Italian communities. Overtures or instrumental arrangements of favourite operatic numbers by composers such as Verdi, Donizetti, Rossini, Bellini, Ponchielli and later Mascagni were part of the repertoire of Italian bandmasters such as Carlo Alberto Cappa, Luciano Conterno and others, who provided music to the balls, concerts and picnics that New York Italian fraternal and mutual aid organisations offered to their members on an almost daily basis.Footnote 75 Important New York Italian-language papers such as Il progresso italo-americano and L'eco d'Italia regularly covered the Italian opera seasons of the Metropolitan Opera House, the Academy of Music and other local venues, and reviewed Italian opera productions in other cities as well. These papers also reprinted Italian opera reviews from Italian, European and South American journals, and directly sold to its subscribers libretti of recent operas – such as Verdi's Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893) – as well as of older works by more or less well-known Italian composers such as Donizetti, Bellini, Mercadante and Cimarosa.Footnote 76

At a time when Italian intellectuals considered settlements of Italian emigrants as colonie (‘colonies’) expanding Italy's political and cultural influence abroad, Italian-language papers, most of which were directly owned and operated by the Italian American financial elite, also celebrated Italian opera and music as a marker of Italy's cultural respectability.Footnote 77 Italian reporters rarely commented upon any musical genre other than Italian opera and Neapolitan songs (especially during the annual Piedigrotta song festival organised in Naples at the end of the summer) and lambasted the critics writing for the mainstream press in English when they favoured non-Italian artists and operatic repertoires over Italian singers and operas.Footnote 78 Italian-language papers also advertised Italian opera performances to their readers and occasionally commented on the Italian audiences attending the show. In November 1894, during a Metropolitan Opera House production of Aida starring the famous Italian tenor Francesco Tamagno, such was the fervour of the Italians in attendance that the critic of Il progresso had to invite the paper's readers to limit their enthusiasm when applauding music or artists from their own country, lest they be seen as ‘a claque as patriotic as in poor taste’ by the non-Italian press.Footnote 79

As popular as Italian opera may have been with the mostly middle- and upper-class Italian American readership of the Italian-language papers, however, there is little evidence that this repertoire circulated as widely among the hundreds of thousands of impoverished immigrants from rural Southern Italian regions that represented the majority of the newcomers from Italy at the end of the nineteenth century. Although historians of Italian immigration have often maintained that Italian opera has always been popular among Italian immigrants regardless of their social condition and region of origin in the motherland, it should be observed that all of the historical sources on which they build this argument date from the beginning of the twentieth century onward.Footnote 80 Furthermore, as ethnomusicologist Roberto Leydi has observed in his study of the circulation of opera in post-Unification Italy, Italian opera only had a marginal role in the cultural life of rural areas in the South of the country, and in those rare cases in which opera excerpts did circulate, they were subject to modifications – such as the simplification of melodic lines and the removal of modulations – that further disconnected this music from the cultural context for which it was originally composed.Footnote 81 Consistent with Leydi's argument, Nicholas E. Tawa observed a direct correspondence between the size of the city or village of origin of Italian immigrants in the USA and their degree of familiarity with opera, and concluded that since ‘a large number of Italians did not come here [the USA] from cities, whatever knowledge and love for opera they had came mainly after they settled in America’.Footnote 82 Yet it is unclear how much leisure time and money might have belonged to the many unskilled Italian labourers who, in the late nineteenth century, worked up to 60 hours per week and often returned to their homeland after just a few years in the USA.Footnote 83 Indeed, a careful reading of the surviving issues of the daily newspaper Il progresso italo-americano for the years 1880–1900 produces no evidence supporting the supposed operatic inclinations of working-class Italian immigrants in the last decades of the century. Similarly, no music other than the tunes played by organ grinders is mentioned in the reports about the working-class Italian communities published in mainstream papers and magazines in English in those decades.Footnote 84

Regardless of the symbolic significance of this genre among Italians, the efficacy of Italian opera as a tool for the social legitimisation for Italian immigrants necessarily rested not on its popularity within the Italian community, but rather on the success that Italian opera artists and composers enjoyed in US society at large. In this sense, by the end of the nineteenth century, the star of Italian opera had been fading for several decades. As Katherine Preston has recently shown, the financial crisis faced by important Italian opera companies following the Panic of 1873, combined with the passing of most of the representatives of the bel canto tradition – with the sole exception of Verdi – and the consequent stagnation of the repertoire, had led to a temporary decline in popularity of Italian opera among middle-class Americans.Footnote 85 Not even the emergence of the Giovine Scuola composers towards the end of the century seemed to mark an improvement. Not only did the new works by Mascagni, Leoncavallo and Puccini fail to threaten the predominance of older Italian operas in the repertoire of major opera houses, but mainstream press critics lamented the presumed crisis of the Italian compositional school as a whole. As late as 1897, The Musical Courier offered a rather desolate picture of the state of Italian opera: ‘Mascagni … has done nothing since Cavalleria rusticana. [Umberto Giordano's] Andrea Chenier … is mediocre … Of Puccini we know nothing except by hearsay … The cold fact in the matter is that with the exception of Verdi Italy has no real, first-class musical genius.’Footnote 86

In this context, Italian elites could hardly weaponise the fame of Italian singers and the symbolic prestige attached to Italian opera against racial stereotyping. Not that they did not try: in December 1889, for example, on the occasion of Francesco Tamagno's American debut in Rossini's Guillaume Tell (performed in Italian) at the inauguration of the Auditorium Building in Chicago, Il progresso's critic dared the ‘ignorant mob’ labelling Italians as ‘dagoes’ to attend the performance and learn ‘to know and respect’ the Italian community.Footnote 87 But given the apathy of the non-Italian upper classes towards any production that did not feature in its cast the most celebrated stars of the day, Italian American elites were aware that leveraging Italian opera for political purposes would be ineffective. In February 1892, when a new Italian company promised to offer productions of operas by Italian composers at popular prices in New York, Il progresso expressed some doubt that such an initiative, as ‘commendable’ as it was, would meet the favour not only of the American middle class but of the local Italian community as well.Footnote 88

At the beginning of the new decade, the central role that the recording industry assigned to Caruso and the other Italian opera stars in the marketing of home phonographs stimulated a renewal of the interest in this genre on the part of the American middle class. As a consequence, expressing enthusiastic support for Italian singers became a viable tactic employed by Italian opera-goers to remark on their cultural identity in front of external observers and indirectly to reinforce their own position in American society.Footnote 89 For those years, there is substantial evidence of Italians of all social classes attending the opera, almost always to hear performances by their famous compatriots. For example, reporting on the opening night of the 1905–6 season at the Met, L'araldo italiano observed that screaming Italian audience members seated in the galleries welcomed Caruso back ‘in all of Italy's dialects’.Footnote 90 Italians were regularly seen at the opera in other cities, too. In March 1908, the Philadelphia press reported that Italian opera enthusiasts lined up in front of the Academy of Music beginning the night before Luisa Tetrazzini's debut in Lucia di Lammermoor.Footnote 91 On the night of the show, the paper continued, three Italians were ‘knocked down and trampled upon’ by the crowd when sales for gallery tickets began, and many others ‘became disheveled in their intense fervor’ after Tetrazzini impeccably performed the high F capping the duet ‘Se tradirmi tu potrai’.Footnote 92 So evident was Italians’ support for their compatriot singers that when Caruso injured his vocal chords in 1909, The Philadelphia Inquirer blamed ‘those more impressed by loudness than by anything else’, and especially Caruso's ‘Italian admirers’ for having forced their idol into harmful displays of lungpower.Footnote 93

American critics soon realised the political implications of Italian audiences’ behaviour at the theatre. At the end of 1909, for example, the editor of Musical America, John C. Freund, expressed his frustration about the conduct of ‘Italians at the Opera’. Freund lamented that Italian audiences cared only about vocal prowess, to the point that ‘they [would] deliberately force a singer … to respond to their plaudits with encores whether he want[ed] or not’. The critic interpreted the enthusiasm of Italian audiences as a matter of chauvinism: ‘the Italians know only one kind of music, that which is composed and sung by their own people … their point seems to be to assert a certain nationality in music, to identify music with Italy’.Footnote 94

The Italian-language press also encouraged the patriotism of Italian opera-goers. Already in 1902, Il progresso argued that since ‘here in America … whether we are rich or poor, naturalised or not, they will only consider us eternally Italian’, the only available option to improve the image of the community was to become ‘most Italian’ (italianissimi) by cultivating an interest in those cultural products, including opera, that were commonly associated with Italy and best demonstrated to americani ‘the superiority of [Italian] intellect’.Footnote 95

Over the first two decades of the century, Italians in several US cities showed their enthusiasm for opera on multiple occasions. Not only did they cheer on fellow Italian singers at the opera house, but they also regularly patronised the many record stores specialising in Italian opera records that were opening in those same years in urban Italian neighbourhoods.Footnote 96 In the first decade of the century, music dealers from different cities reported high sales of opera records, including the prestigious Victor Red Seals, among Italian labourers.Footnote 97 It should be noted, though, that it was not necessary to buy the most expensive records to listen to opera. In fact, the catalogues of Edison, Columbia and Victor regularly offered more affordable versions of favourite operatic numbers performed by less prestigious singers.Footnote 98

Italian Americans, however, were far from listening exclusively to opera. In the same years, regional folk music and Neapolitan popular music were also very popular (if not more popular than opera) within Italian communities.Footnote 99 Since the early 1900s, in response to the Italian demand for this music, companies such as Columbia and Victor began to advertise and distribute to their dealers special ‘ethnic’ record catalogues including Neapolitan popular songs, folk songs from different Italian regions, patriotic songs such as the Italian national anthem or the Inno di Garibaldi, dances, and comic scenes delivered in different dialects.Footnote 100 In the 1910s, several independent labels dealing in Italian regional songs operated in New York, while a network of Neapolitan song artists developed in several Italian communities across the USA.Footnote 101 Whether through opera or via the regional songs circulated by major recording companies and independent labels, the phonograph and other recording devices such as the player piano strengthened Italian Americans’ perceived cultural ties with Italy or with their specific region of origin in the motherland, while also encouraging them to become enthusiastic consumers of American-made cultural goods.Footnote 102

Not much of the non-operatic repertoire was known outside the Italian community, however. Leaving aside a few Neapolitan hits such as ‘O sole mio’, ‘Core ’ngrato’ or ‘Santa Lucia’, interpreted by famous opera singers such as Caruso, Tetrazzini and Zenatello, mentions of non-operatic Italian music were scarce in the catalogues and music publications catering to the record companies’ general clientele. Soon, the indifference towards Italian regional repertoires outside Italian communities, combined with the emphasis placed on opera by recording companies, the Italian-language press and non-Italian critics, helped to promote a simplified image of Italians’ musical interests, serving to clear the path for the emergence of new stereotypes.

* * *

Italian immigrants and their descendants strove to take advantage of the new visibility – and, crucially, the newly performer-centred audibility – granted to Italian opera by the recording industry. Victor and other recording companies used opera to break previous associations between the phonograph and earlier mechanical music instruments such as coin-operated proto-jukeboxes and the barrel organ, with all of their racial and social baggage. But what was a merely commercial strategy in the eyes of recording entrepreneurs opened new possibilities for Italian papers, political leaders, audiences and record purchasers, who now saw opera, both performed and recorded, as a political tool to improve the perception of Italian immigrants in American society. From this perspective, to borrow from Jacques Rancière, the cultural prominence assigned to opera produced a new ‘distribution of the sensible’ – a novel perception of Italian immigrants and the extent to which they could partake in highbrow cultural practices from which they had previously been excluded.Footnote 103

And yet, this novel distribution of the sensible created ambivalent possibilities for representation. Although references to Italian organ grinders in the press and in Tin Pan Alley songs would not completely disappear for many decades to come, the increasing availability of home phonographs contributed to a declining relevance of street musicians in the sonic landscape of early twentieth-century American cities.Footnote 104 The last New York hand organ factory closed in 1917, and by the mid-1920s, according to the Times, organ grinders had almost become ‘extinct’.Footnote 105 Some street musicians, including many from the Viggiano area, began to work as music teachers or bandleaders, or joined prestigious orchestras in New York, Chicago, Seattle and other American cities.Footnote 106

But as the presence of Italian organ grinders was slowly fading out of the contemporary press, middle-class Americans’ perception of the support of opera on the part of Italian press and audiences breathed life into new monsters. As Larry Hamberlin has shown, a number of opera-loving Italian barbers, fruit peddlers and farmers – that is, the professions most typically associated with working-class Italians in contemporary vaudeville – appeared in Tin Pan Alley songs beginning in the early 1900s.Footnote 107 And yet, the Italian opera they sing is not ‘Italian opera’. Instead, their appeal to opera undermines them, especially through linguistic means. Despite their familiarity with opera, Italian immigrants are presented in these songs as fundamentally uncultivated and incapable of expressing themselves in any language other than their ‘dialect’ (in reality, no more than a phonetic transcription of Italian-accented English). What is more, such a representation of Italian ethnicity usually took place within a ragtime-inspired musical setting – that is, precisely the kind of popular, African American repertoire against which the Italian prominenti were attempting to define their lofty ideal of Italian national culture.Footnote 108

The nationalistic support of opera on the part of Italian immigrants brought with it a new wave of denigrating representations in the popular music industry and the American press. However, because of the prominent role assigned to Italian opera in the marketing of home phonographs, Italian newspapers, listeners and political leaders had the opportunity to participate in the fabrication of the stereotype, and thus exert a limited degree of control over the narrative of immigration. To an extent, their intervention led to an improvement. Essentialist as it was, the definition of Italian immigrants as opera lovers would be useful in the following decades to divert the attention of US citizens from the much less flattering representations of Italian Americans that had been promoted by American literature, press and cinema, from Al Capone to The Godfather. At the same time, the emphasis placed on opera in the definition of Italian identity also had repercussions within Italian communities in the United States. After World War I, as Americanisation efforts in schools, churches and settlement houses gradually removed Italian children from the culture and language of their parents, second-generation Italian Americans began to reject the folk and regional repertoires that for several decades had so enriched the music landscape of Italian immigrants. However, they did not distance themselves from opera – at least until the rise of Frank Sinatra, the first Italian American music star – which now became the only musical genre available to express their ethnic origins within the boundaries of their Americanised status.Footnote 109 A new Italian American musical identity was born.