Why complete a formulation in CBT?

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is widely recognised in national treatment guidelines as being an effective form of psychotherapy. It shares with other evidence-based approaches a focus on problems relevant to the person, an underlying structure/model of making sense of experience, and builds on a relationship with the patient (Reference Kuyken, Padesky and DudleyKuyken 2011). It also provides a helpful personal framework for practitioners to reflect on their own reactions to patients, their team and the everyday challenges they face working in the NHS or in their personal life (Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites and HaarhoffBennett-Levy 2015).

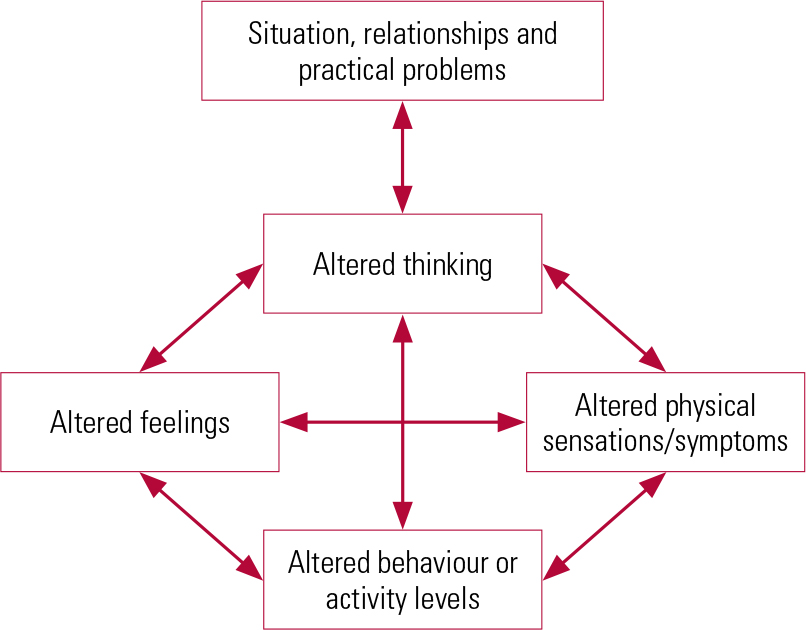

A CBT-based formulation, or clinical summary, is essentially a ‘vicious circle’ model. It argues that there are two-way relationships between what people think, how they feel emotionally and physically, and what they do (Fig. 1). Crucially, it also incorporates the supports (or not) around the person, together with the practical issues and challenges faced on a daily basis. Each area interacts with the others to affect the person’s overall experience. CBT aims to help patients identify and move towards more helpful styles of thinking, behaving or relating to others. Because of the nature of a vicious circle, interventions can be made at any point, and any intervention made can break or improve the overall vicious circle. The aim is also to build on current and past helpful/ adaptive responses and resources.

FIG 1 A CBT formulation using the five areas approach (Reproduced, with permission, from Reference WilliamsWilliams 2014).

Using the vicious circle with patients

Summarising a patient’s problems using their own words and sharing this openly and collaboratively empowers them, enabling them to add to or modify their summary of the impact of symptoms. This both provides a model of understanding and identifies clear targets for change. The summary is dynamic and responsive over time, reflecting the progress or worsening of symptoms over a course of treatment.

The formulation also incorporates the support from and problems caused by key people around the person and addresses issues such as isolation or loneliness. It can also include an understanding of our response to the patient and their reactions to us.

Using the approach in our teams and on ourselves

Whatever their background, all mental health workers assess the impact on the patient of that person’s thoughts, feelings, behaviour and relationships. This provides content that can be summarised in a CBT formulation. Thus, a CBT case summary provides a helpful and focused way of communicating key information between team members from different professional backgrounds. It can also be used to inform decision-making.

The CBT-based assessment is also helpful for self-reflection on clinical practice and team working. Critical events cause uncertainty and challenge team morale. Also, certain patients can be unpopular within teams, triggering strong reactions, sometimes including anxiety and anger. This can affect us as clinicians and also our colleagues. Examples might be people with personality disorders, multiple comorbid conditions, including drug and alcohol misuse, and those who do not improve with treatment. Unhelpful patterns of thinking and responses can lead to overly strong reactions between colleagues and between teams. Taking a step back to reflect on our own responses in difficult situations – and identifying unhelpful patterns of response – can minimise the potential for complaints and also help us to achieve clarity in personal and professional boundaries.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.