1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. This paper has been written partly in response to the challenge from the Pensions Regulator (TPR) to introduce an Integrated Risk Management (IRM) framework for the funding of Defined Benefit (DB) pension schemes in the United Kingdom. Partly too, it has been written in response to recent criticism of pension funding approaches adopted by actuaries.

1.1.2. Such criticism of pension funding has sometimes seemed to come from two opposing views: There are those who think that actuaries and trustees are being too prudent in their assumptions and as a result pension scheme liabilities are overstated. Others have warned that actuaries and trustees are being imprudent by not demanding that pension schemes be better funded – pointing to recent high-profile cases such as BHS which failed leaving a pension scheme deficit and members facing cuts to their benefits. This tension has even been evident in the national press with stories published and press releases issued, presenting very different views of the state of pension funding in the United Kingdom.Footnote 1

1.1.3. This tension is not new. Thornton & Wilson (Reference Thornton and Wilson1992) published a paper “A Realistic Approach to Pension Funding” advocating the need for realistic bases and an objective approach to determining “best estimate” assumptions. They suggested that “typical funding bases often contain hidden and undesirable margins”. Nor is the issue of security new. McLeish & Stewart (Reference McLeish and Stewart1987) stated “the prime purpose of funding an occupational pension scheme must be to secure the accrued benefits, whatever they might be, in the event of the employer being unable or unwilling to continue to pay at some time in the future”.

1.1.4. This paper suggests that there are a number of problems with the current scheme specific funding approach adopted by UK pension schemes. In particular:

– There is little evidence that prudence in actuarial funding assumptions is being linked to the strength of the employer covenant, despite this being a key principle of scheme specific funding and promoted at length by TPR.

– There is evidence that many pension schemes are carrying levels of investment risk which appear to be greater than the employer’s balance sheet can easily manage, with some companies (even within the FTSE100) carrying more equity exposure in their pension scheme than equity on their own balance sheet.

– There is often little linkage of funding and investment strategies. For example, the use of separate discount rates for valuing liabilities pre- and post-retirement is rarely linked to an investment strategy aimed at switching into bonds as pension scheme members retire.

1.1.5. Given that these are the areas and links that are specifically addressed in TPR’s IRM framework, this paper suggests that it is time for change. Specifically this paper aims to present an approach to funding pension schemes which meets TPR’s principles and at the same time gives a transparent response to those who have criticised pension funding methodology, either for being too prudent or not prudent enough.

1.1.6. Earlier this year, sadly, the distinguished actuary and Past President of the Institute of Actuaries, Jeremy Goford died. He was a great champion of the need for actuaries to be transparent and focussed on customer needs. In his 2002 Presidential Address he spoke on the “presumption of trust in financial transactions being replaced by a demand for openness, transparency and accountability, coupled with the demonstration of benefit to the customer”. This paper tries to live up to Jeremy’s challenge by promoting an approach to the funding of pension schemes which is open, transparent, accountable and focussed on meeting customer needs.

1.2. What is This Paper Trying To Achieve?

1.2.1. The funding of a pension scheme is simultaneously trying to achieve two objectives which are not always aligned:

– Financing a long-term obligation – funding benefits as they fall due.

– Providing security for members’ benefits.

These are two distinct objectives which potentially require a different approach to setting assumptions, particularly the discount rate. In particular it is the challenge of these two sometimes conflicting objectives which lies at the heart of some of the criticism of pension funding methodology mentioned above. A pension funding plan agreed at an actuarial valuation can simultaneously represent an expectation that funds will be more than sufficient to meet benefits as they fall due (i.e. representing a “surplus”) and, at the same time, be insufficient to ensure that members’ benefits are secure (i.e. representing a “deficit”).

1.2.2. This conflict was recognised by a research project on discount rates carried out in 2010–2012 by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA). This project identified two main types of actuarial calculations and, correspondingly, two approaches to setting discount rates. The IFoA’s discount rate project is revisited in this paper which then considers how the framework proposed in that project can be used to meet the challenges of scheme specific funding and IRM.

1.2.3. In order to meet TPR’s challenge of IRM, this paper will propose a methodology which will directly link funding, investment and the strength of the employer covenant. The proposed methodology will also improve transparency on the security of members’ benefits and, at the same time, help all parties to the pension scheme understand realistic outcomes for the future financing of the long-term obligations of the pension scheme.

1.2.4. This paper is set out as follows:

∙ chapters 2 and 3 look at the recent history of the regulatory framework for funding DB pension schemes in the United Kingdom;

∙ chapters 4, 5 and 6 then explore the economic theory behind pension scheme funding and look at how different regulatory frameworks have evolved around the world;

∙ chapter 7 defines in more detail the question this paper is trying to answer;

∙ chapters 8 and 9 look in more detail at developing the funding objective and the funding framework and how the links are drawn between funding, investment and employer covenant;

∙ chapter 10 explores some of the challenges of modelling investment returns in the proposed framework;

∙ chapter 11 presents a short summary of the proposed new approach to funding; and

∙ chapter 12 presents conclusions and recommendations.

1.2.5. For some readers, chapters 2 and 3 may seem detailed background reading which is already familiar. Such readers may therefore choose to jump straight to chapter 4. Indeed those readers who wish to go straight to the proposed funding approach outlined in this paper can jump straight to chapter 7. However these extra chapters are included here as they set important context for what is to follow. In particular, two key questions are closely addressed:

∙ What is the purpose of minimum funding legislation?

∙ Does a formulaic approach to minimum funding, requiring limited actuarial input, result in better or worse outcomes than a flexible approach based on scheme-specific actuarial advice?

It is also interesting and instructive to note some of the lessons that can be learned by looking at the historical development of UK funding policy (as well as the development of funding policies overseas), in particular the attitude towards pension deficits and the time period over which they should be cleared. When the Minimum Funding Requirement (MFR) was introduced many actuaries thought 5 years was too long a period over which to clear a deficit. Today many actuaries have experience of setting recovery periods which are in excess of 20 years.

2. Development of Pension Scheme Funding Over the Last 15 Years

2.1. Introduction

This paper starts by reviewing the development of pension scheme funding in the United Kingdom over the last 15 years which importantly includes the transition period from the previous funding regime (the MFR) to the current funding regime (scheme specific funding). This paper considers how the current funding regime has evolved since its introduction in 2005 and alongside this how the Pension Regulator’s thinking has developed.

2.2. A Look Back at the MFR

2.2.1. The MFR was established under the Pensions Act 1995 and came into effect on 6 April 1997. It applied to most funded, DB, private sector pension schemes.

2.2.2. The Pensions Act 1995 itself arose in the main in response to public concerns following the Maxwell scandal of the early 1990s, and the subsequent Goode Committee’s report which recommended a “minimum solvency requirement to secure the pension rights of members”. Up until 1997 there were minimal UK legislative requirements about the level of assets an on-going scheme needed to hold. Other than meeting contracting-out requirements, the minimum level of funding required, if any, was solely dictated by the scheme trust deed and rules and therefore, trust law and expectations placed on trustees.

2.2.3. The MFR was originally designed, in the event of a company going insolvent, to keep pensions in payment whilst also providing non-pensioner members with a cash equivalent transfer value that would, following investment, provide an “even chance” of receiving a pension equivalent to that which would have been provided by the relevant scheme. It was not designed, contrary to some public perception, to require pension schemes to hold sufficient assets to ensure that all members’ benefits could be fully secured if the scheme were to be wound up. This was highlighted in the IFoA report to the Secretary of State for Social Security (May 2000. Review of the Minimum Funding Requirement) which noted: “The point at which members’ security becomes of vital importance is when the scheme is wound up, particularly if this event is caused by the insolvency of the employer. It is our contention that there may be a widespread misplaced public perception that a scheme which is 100% funded on the MFR test would provide full security for members’ benefits.”

2.2.4. Legislation (sections 56–61 of the Pensions Act 1995) set out the broad requirements of the MFR. The details implementing the MFR were summarised in Occupational Pension Schemes (MFR and Actuarial Valuation) Regulations (1996), notably:

(i) Section 57 required trustees to obtain a valuation from an actuary on the MFR, generally on a triennial basis;

(ii) Section 58 required trustees to prepare, and an actuary to certify, a schedule of contributions payable over a 5-year period which ensured that schemes remained 100% funded throughout or, for those schemes that were at least 90% funded, reached 100% funding by the end of the 5-year period;

(iii) Section 60 required the majority of schemes below 90% funded to reach the 90% level within 12 months, unless serious under-provision was identified. In the event of serious under-provision, the scheme had 6 years to reach 100% funded status.

2.2.5. The details of the methods and assumptions to be used, however, were set out in GN27: Retirement Benefit Scheme – MFR which was issued and monitored by the IFoA.

2.3. What Would the MFR Look Like Today?

2.3.1. As mentioned in 2.2.3 above, the funding objective of the MFR was for a scheme to hold assets to meet its liabilities, as set out below:

(i) All active and deferred members can receive a cash equivalent transfer value to be invested in a personal pension arrangement which has a reasonable expectation of providing their accrued deferred benefits;

(ii) Pensioner liabilities can be externally secured via annuities purchased with an insurance company;

(iii) And finally any expenses can be met.

2.3.2. It is difficult to consider how the MFR would have evolved through time, in particular noting the point made in paragraph 2.4.1 below where it is clear that the IFoA’s recommendations for updates were not always accepted. In particular, it would have been challenging to agree an approach to deriving Market Value Adjustments given the variety and volatility of market conditions experienced, both in the United Kingdom and worldwide, over the last 15 years.

2.3.3. However, by applying the core principles described in 2.3.1, it is possible to consider what funding positions would look like today if pension schemes applied this particular funding objective.

2.3.4. As the MFR targeted full funding on an annuity buy-out basis for pensioners, it is clear that for more mature schemes the funding target would be higher than it is today (for schemes that are funding on an ongoing basis rather than currently targeting buyout).

2.3.5. For non-pensioners, it is interesting to consider how the guidelines surrounding the principle of provision of a cash equivalent transfer value to allow members to replicate their benefits has changed over the last 15 years. Actuaries who have advised Trustees and sponsoring employers on bulk transfer value exercises will recognise the principle in relation to “critical yield” transfer values. Following rules set by the Financial Conduct Authority a financial advisor will consider the merits of a transfer value for a member of a DB pension scheme by establishing the “critical yield” on the transfer value. The critical yield is the estimated growth rate required on the transfer value to allow the member to match the benefits due from the DB scheme using an alternative personal pension. In practice the investment return assumption achievable before retirement will reflect the individual’s attitude to risk and expected investment choices, and the assumptions post retirement reflect individual annuity costs at retirement.

2.3.6. Therefore, it is likely today that the MFR-funding objective (if it had continued in existence) for non-pensioners would reflect best estimate returns before retirement, and individual annuity buy-out costs after retirement.

2.3.7. The MFR target was not affected by employer covenant strength, or the expected long-term investment strategy of the pension scheme.

2.3.8. Simple analysis of the core principles behind the MFR suggests that the MFR would produce a higher funding target than scheme specific funding in the majority of cases, with the exception of:

(i) immature schemes with a much lower than average age; and

(ii) scheme specific funding examples where full funding on a buyout basis is already being targeted.

2.3.9. An important feature of the MFR was that, where a deficit was identified, it required full funding to be reached over a prescribed and relatively short time horizon. The average recovery plan today is not far short of 10 years (and rising). This compares to the 5-year recovery plans required under the MFR with just 1 year to get to 90% funding.

2.3.10. The strict recovery plan requirements alongside ever maturing pension schemes would likely push most schemes towards a matching investment strategy to reduce the potential for significant cash contributions being required over a short time horizon. Demand for UK government bonds by UK pension schemes could well have been even higher than it is today had the MFR been retained.

2.3.11. While perceived distortions in investment strategy were a key criticism of the MFR, it is likely that retaining the MFR would have resulted in many pension schemes moving towards a matched position more quickly. The changes that have occurred over the last 5 years, with a significant move towards matching assets, may have happened sooner. Therefore pension scheme funding levels might have been better protected from the significant falls in yields seen since the start of 2011.

2.3.12. The structure of the MFR required the use of dual pre- and post-retirement discount rates. It is interesting to consider the influence of this structure on actuaries recommending assumptions as part of the transition to scheme specific funding. An analysis of The Pensions Regulator’s Annex to its 2017 Scheme funding statistics implies that around two-thirds of schemes still use a dual discount rate. A more prudent post retirement discount rate does mean that the funding objective becomes gradually more prudent overall as the pension scheme matures and it may also be reflective of the developing investment strategy. However, it seems more likely that the prevalence of dual pre- and post-retirement discount rates in scheme specific funding valuations is simply a hangover from the MFR.

2.4. The Transition to Scheme Specific Funding

2.4.1. During the MFR’s period of existence the IFoA made four recommendations to the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) to amend the MFR basis – on two occasions to strengthen and on two occasions to weaken the funding basis. It is notable that only the two recommendations to weaken the MFR basis were implemented, in 1998 and 2002.

(i) June 1998 – changes to the MFR formula reduced MFR liabilities by up to 19%

(ii) March 2002 – changes to the MFR formula reduced MFR liabilities by up to 8%

2.4.2. The MFR had only been effective for 2 years when the Government announced a review and in 2000, alongside the Department of Social Security (DSS) consultation, the IFoA raised their own concerns on the MFR methodology, notably,

(i) the focus by trustees and employers on short-term market conditions rather than long-term pension funding and investment strategies;

(ii) the depression of yields created by the additional demand for long-term gilts;

(iii) the rigid and mechanical rules for setting minimum contribution rates; and

(iv) the gap between the security actually provided by the MFR test and the public’s perception of what the MFR would deliver.

2.4.3. This paper considers later the extent to which the scheme specific funding regime has resolved these concerns.

2.4.4. Over the following years, and as part of the DSS consultation, the criticism of the MFR continued from numerous industry bodies:

(i) “There is a large and worrying gap between the level of security which the MFR test actually delivers and the public’s perception of what it will deliver” (Source: The Faculty of Actuaries and Institute of Actuaries, Review of the Minimum Funding Requirement, May 2000).

(ii) “The MFR was a flawed approach. It distorted investment decisions for some schemes and it increased regulation and costs for sponsoring employers, without delivering the level of security which many people expected” (Source: DWP, Simplicity, security and choice: working and saving for retirement: action on occupational pensions, June 2003).

2.4.5. In their May 2000 report on the Review of the MFR, the IFoA outlined their vision for revised MFR proposals alongside a new additional test which would “indicate the level of cover achieved against a stronger test, designed to give all members a very high chance of receiving their accrued benefits on winding up”. It was proposed that this valuation method would be based solely on bond yields with an explicit risk based addition.

2.4.6. Alongside the commentary from the pensions industry and the Government, Paul Myners also stated in November 2000 that the MFR was a source of distortions in investment decision-making and should be replaced:

“Providing security for members of defined benefit pension schemes is an essential objective for any responsibly run pensions system. While I am sure that the overwhelming majority of pension funds are run both properly and effectively, it is essential to have effective safeguards to ensure that members of defined benefit pension schemes can have confidence in the system. I do not believe that the MFR is such a safeguard. An effective alternative is needed. It is also a source of distortions in investment decision-making” (Source: Letter from Paul Myners to the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Secretary of State for Social Security, 8 November 2000).

It is important to note that the UK Debt Management Office disagreed with this view, noting in its Gilt Review (July 1999) that: “However, there are several factors that have contributed to the fall in yields. These include low levels of primary issuance, the effects of funds maturing, the need to reduce the volatility of pension fund assets and ‘limited price indexation’.”

2.4.7. In March 2001 the concept of scheme specific funding was introduced, alongside the abolition of the MFR:

(i) “The review recommends that the MFR should be replaced by a scheme-specific long-term approach based on transparency and disclosure, under which pension funds would report publicly on the current financial state of the fund and on future funding plans. This would make clear where funds’ ability to pay future pensions was based on reckless or unsuitable assumptions about investment returns, level of contribution, life expectancy and so on” (Source: HM Treasury, Institutional investment in the UK: a review, March 2001).

(ii) “The Government will legislate to replace the MFR with a long term scheme-specific funding standard, with additional protective measures, including a statutory duty of care for the scheme actuary, stricter rules on voluntary wind-up and extension of compensation for fraud” (Source: HM Treasury, Budget 2001 – investing for the long-term future: building opportunity and prosperity for all, March 2001).

2.4.8. Over the next few years the Government set out a number of proposals including the December 2002 Pensions Green Paper and the June 2003 White Paper on occupational pensions (simplicity, security and choice: working and saving for retirement) but it was not until the Pensions Act 2004 that the MFR was formally abolished and a new scheme specific funding regime was finalised and became law on 18 November 2004. Additionally, on 11 June 2003, the Government changed the debt on the employer regulations so that they became based on full solvency (Section 75) liabilities rather than MFR liabilities. Overnight, this changed the balance of the focus on security in DB pension schemes.

2.4.9. The Pensions Act 2004 introduced a number of key changes to the UK pension environment, not least the introduction of scheme specific funding requirements. This included the establishment of TPR, the Pension Protection Fund (PPF), changes to employer debt requirements, changes to minimum annual pension increases and the introduction of Trustee Knowledge and Understanding requirements. These are discussed further in the following sections.

2.5. Scheme Specific Funding Requirements

2.5.1. Pension schemes must comply with the scheme funding requirements under Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004. Part 3 provides the statutory framework for how the trustees must assess their scheme liabilities and determine the pace and period over which these liabilities must be funded. Many aspects of the Pensions Act 2004 were informed by the EU’s 2003 IORP Directive.

2.5.2. The Pensions Act 2004 describes the statutory funding objective:

(i) Every scheme is subject to a requirement (“the statutory funding objective”) that it must have sufficient and appropriate assets to cover its technical provisions.

(ii) A scheme’s “technical provisions” means the amount required, on an actuarial calculation, to make provision for the scheme’s liabilities.

2.5.3. Further detail is provided by The Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Funding) Regulations 2005. Some key excerpts:

(i) “it is for the trustees or managers of a scheme to determine which method and assumptions are to be used in calculating the scheme’s technical provisions”;

(ii) “the economic and actuarial assumptions must be chosen prudently, taking account, if applicable, of an appropriate margin for adverse deviation”;

(iii) “the rates of interest used to discount future payments of benefits must be chosen prudently, taking into account either or both:

∙ the yield on assets held by the scheme to fund future benefits and the anticipated future investment returns, and

∙ the market redemption yields on government or other high-quality bonds”;

(iv) “the mortality tables used and the demographic assumptions made must be based on prudent principles, having regard to the main characteristics of the members as a group and expected changes in the risks to the scheme”.

2.5.4. There was also a subtle change introduced in the impact on the security of members’ benefits. None of these legislative references refer to the ability of the scheme to pay benefits as they fall due. A review of the legislation confirms that there is no longer any explicit reference in current UK pension legislation to paying benefits as they fall due. This point is explored further in 2.7 below.

2.6. TPR

2.6.1. The Pensions Act 2004 called for the introduction of an independent body to regulate work based pension schemes in the United Kingdom. TPR was created as the regulator of work-based pension schemes in the United Kingdom. TPR’s statutory objectives are:

(i) to protect members’ benefits;

(ii) to reduce the risk of calls on the PPF;

(iii) to promote, and to improve understanding of, the good administration of work-based pension schemes;

(iv) to maximise employer compliance with automatic enrolment duties;

(v) to minimise any adverse impact on the sustainable growth of an employer (in relation to the exercise of the regulator’s functions under Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004 only).

The first three objectives are set out in the Pensions Act 2004 with the four and fifth objectives introduced later as part of the Pensions Act 2008 and Pensions Act 2014, respectively.

2.6.2. In October 2005 TPR launched a consultation on the approach it would take to regulating scheme funding requirements. In the consultation TPR identified a number of underlying regulatory principles and used these to guide the development of the approach:

1. “protecting members – we will support trustees and employers working to maximise protection of the benefits that the employer promised to pay and that members are expecting.

2. scheme specific – it is not our role, nor is it consistent with government policy, to set a funding standard, because each scheme needs to take account of its particular circumstances.

3. risk-based – regulatory intervention should be focused on the schemes that pose the greatest risk to their members or the PPF. While it is never possible to eliminate all risk, those in a position to do so should seek to mitigate those risks wherever it is reasonable to do so.

4. proportionate – trustees are required to correct any shortfall as quickly as the employer can reasonably afford. We intend to distinguish between those schemes where rapid elimination of the shortfall would have a serious impact on the employer and those where employers could potentially afford to pay off the shortfall more quickly.

5. preventive – we need where possible to act before risks materialise.

6. practicable – we need an approach that can be operated within the constraints of the information and resources available to us.

7. referee not player – the responsibility for ensuring that schemes are fully funded rests with trustees and employers with the help of their advisers – the regulator will not interfere with this responsibility where it is discharged consistently with their own duties.”

(Source: Consultation document – How the Pensions Regulator will regulate the funding of defined benefits, October 2005).

2.6.3. As part of the 2005 consultation, TPR clarified that it would use “triggers” to help it identify which schemes it should engage with. These triggers were of two types

(i) A technical provisions trigger. This compared the scheme’s technical provisions with two different liability values – the s179 value and the accounting (FRS 17 or IAS 19) value and aimed to take into account the maturity of a scheme and the strength of the employer’s covenant when deciding whether triggers were breached.

(ii) A Recovery Plan trigger. Where recovery plans were longer than 10 years, contributions are weighted towards the end of the Recovery Plan (back-end loading) or where assumptions in the recovery plan are inappropriate.

2.6.4. Detailed guidance was published in February 2006 in TPR’s Code of Practice 03 – Funding DBs. This code of practice remained in place until it was revised in 2014.

2.6.5. TPR’s approach has evolved over the last 10 years as it has had to react to changes in market conditions and changes in the behaviour of trustees and employers in relation to pension schemes.

2.6.6. An excellent example of this relates to the triggers that TPR initially proposed to use. A clear consequence of using a recovery plan trigger of 10 years was that it indeed encouraged schemes to set recovery plans that were less than 10 years. But possibly encouraged by the view that up to 10 years was acceptable, many recovery plans were set at the 10 year limit – a considerable increase on the MFR recovery plans that had applied previously. For the first three years where data is available, TPR’s scheme funding analysis highlighted that 25% of schemes established recovery plans longer than 10 years, and there was a significant proportion that adopted a recovery plan length just shorter than 10 years. For valuations carried out between 2005 and 2008, 50% of pension schemes had a recovery plan length of between 5 and 10 years. 25% of schemes had a recovery plan length of between 8 and 10 years (Source: TPR Scheme Funding Statistics June 2016). The triggers were clearly influencing behaviour.

2.6.7. In October 2008 TPR published its first ‘reactive’ statement in response to the 2007/2008 financial crisis. Following that a number of further statements were published including:

1. Statement to employers sponsoring DB schemes (February 2009)

2. Alerts to risks in the economic downturn (April 2009)

3. Scheme funding and the employer covenant (June 2009)

4. Understanding employer support for DB schemes (June 2010)

2.6.8. In 2012 TPR started publishing its annual DB funding statements. These statements aim to highlight key issues for schemes undertaking valuations in the relevant year and provide guidance on TPR’s latest thinking.

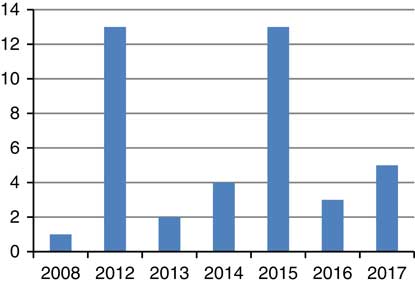

2.6.9. It is interesting to compare the language used in the original 2008 statement and the 2012–2017 annual statements to examine how this changes over time. The use of key words can provide a guide.

2.6.10. As can be seen from Figure 1–6, there are common themes throughout the period. “integrated” and “covenant” are both referred to throughout, with “risk” becoming an ever increasing focus over time. A focus on “gilt” and “bond” yields also coincides with a focus on “deficits”. Whilst “triggers” were key in the original 2008 statement, it is interesting to see that they are only referenced again in 2013 when TPR announced that it was no longer going to refer to them.

Figure 1 “Gilt/bond” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

Figure 2 “Deficit” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

Figure 3 “Risk” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

Figure 4 “Covenant” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

Figure 5 “Integrated” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

Figure 6 “Trigger” word count in each annual the Pensions Regulator (TPR) statement (Source: TPR annual defined benefit funding statements 2008 and 2012–2017)

2.6.11. Analysis of TPR statements suggests that apart from specific changes in approach (e.g. the removal of triggers), changes in TPR’s message to schemes represents an “evolution” of views rather than a “revolution”. The core of TPR’s message has remained the same and reflects their original views; however, the way in which TPR has presented these views to stakeholders has changed, and improved, over time.

2.7. Interaction of Scheme Specific Funding with Trustee Duties

2.7.1. Trustees are required to act within the framework of the law. The general law of trusts applies, alongside specific UK law applying to pension schemes, including Acts of Parliament and regulations. The law is supported by codes of practice and guidance issued by TPR.

2.7.2. Pension scheme trustees have the following duties under trust law:

(i) to act in line with the trust deed and rules;

(ii) to act in the best interests of the scheme beneficiaries;

(iii) to act impartially; and

(iv) to act prudently, responsibly and honestly.

(Source: TPR guidance on trustee roles and responsibilities http://www.thepensionsregulator.gov.uk/trustees/role-trustee.aspx)

2.7.3. The fundamental duty of trustees is to pay benefits in accordance with the provisions of the trust and any overriding legislation. When considering pension scheme funding this fundamental duty is often interpreted as requiring Trustees to fund the scheme in such a way as to ensure that benefits can be paid as they fall due.

2.7.4. The Pensions Act 2004 makes no reference to the ability of the scheme to pay benefits as they fall due and indeed there is little or no explicit reference to paying benefits as they fall due in current UK pension legislation.

2.7.5. The last time legislation required reference to funding for benefits as they fall due was under the MFR, which required actuaries to certify that “In my opinion, the resources of the scheme are likely in the normal course of events to meet in full the liabilities of the scheme as they fall due” (Source: Section 56–61, Pensions Act 1995).

2.7.6. Despite this, TPR’s definition of Technical Provisions is “Technical Provisions – They measure the extent of the liabilities to pay pension benefits in relation to past service as they fall due” (Source: TPR Glossary http://www.thepensionsregulator.gov.uk/glossary.aspx). Paying benefits as they fall due is referred to frequently throughout TPR guidance.

2.7.7. There is a subtle difference between “the amount required, on an actuarial calculation, to make provision for the scheme’s liabilities” under the Pensions Act 2004 and “the liabilities to pay pension benefits in relation to past service as they fall due” under TPR guidance. The first definition is a subset of the second definition. It is possible for a pension scheme to have enough assets today to match an actuarial calculation of its liabilities, but for the asset base to be completely depleted at a particular point in the future before all benefits have been paid as they fall due.

2.7.8. In the original European Directive (June 2003) Technical Provisions are not defined explicitly. However, some guidelines are set out in the Directive on how the calculation is to be done: “The minimum amount of technical provisions must be calculated by a sufficiently prudent actuarial valuation and must be sufficient both for pensions and benefits already in payment to continue to be paid and reflect commitments arising from members’ accrued rights” (Source: Article 15.4(a), European Directive, June 2003). There is therefore a stronger reference to paying benefits as they fall due in the original European Directive wording than there is in UK legislation, which TPR has embraced.

2.7.9. TPR’s definition is arguably more appropriate as it encourages schemes to consider cash flow and liquidity issues when considering scheme funding, which could in theory be ignored if a strict interpretation of the Pensions Act 2004 legislation was adopted.

2.8. PPF

2.8.1. The PPF was one of the measures set up by the Pensions Act 2004 in response to a series of high-profile cases in which pension schemes had wound up with insufficient assets to meet their pension commitments. The PPF commenced operations on 6 April 2005 and applies to schemes that started winding up after that date. The PPF was established to pay compensation to members of DB and hybrid occupational pension schemes where an employer has become insolvent, and where there are insufficient assets in the pension scheme to cover PPF levels of compensation. It is funded from the assets of schemes transferred to the PPF, investment returns and by annual levies paid by eligible schemes. Eligible schemes include most DB and hybrid occupational pension schemes, but some pension schemes are exempt, for example, unfunded public service schemes and public sector schemes providing pensions to local government employees.

2.8.2. The PPF provides compensation for scheme members at two levels

(i) 100% to people that have reached their scheme normal pension age or are in receipt of an ill-health or survivors’ pension at the time the scheme enters the PPF assessment period.

(ii) In other cases, 90% of their benefits subject to a compensation cap.

2.8.3. PPF compensation also provides for a standard level of revaluation, pension increases and survivors’ benefits.

2.8.4. Not paying 100% of original scheme benefits to non-pensioner members was a deliberate decision, taking into account the cost of the PPF (through levy payments) and moral hazard issues.

2.8.5. There continue to be moral hazard issues to take into account and it is interesting to consider whether schemes would take less risk in their funding strategy if the PPF did not exist. The November 2009 High Court case Independent Trustee Services Ltd v Hope determined that Trustees are not permitted to take into account the existence of the PPF when making certain decisions. However, despite this ruling, it is clearly impossible for Trustees to discount the existence of the PPF completely in their deliberations.

2.8.6. The existence of the PPF can create conflicting situations for Trustees and employers. For example, consider the case of a very poorly funded pension scheme (i.e. funded at levels significantly less than those required to cover PPF levels of compensation), with a sponsoring employer where the covenant strength is deteriorating. It may be in the interests of the PPF for the Trustees to wind up the pension scheme immediately, securing any remaining assets to help fund the deficit, before the scheme enters the PPF. However, it may be in the interests of the members for the Trustees to try to keep the scheme going for as long as possible, so that more members pass normal pension age and so receive higher levels of compensation. In addition, any pension increases received in excess of PPF levels in the interim will also increase members’ initial pensions from the PPF. How should Trustees act in this situation given their core duties?

2.8.7. The first schemes entered the PPF in November 2006 and as of 31 March 2017 the PPF was responsible for around 890 schemes, over 230,000 members and over £25 billion of assets. In addition, around 200 schemes entered into an assessment period with the PPF but did not transfer to the PPF. This is usually because the scheme has been rescued (i.e. additional funds recovered on insolvency or provided by another party were sufficient to allow the scheme to secure benefits above PPF levels), or the scheme is sufficiently funded on a PPF basis to pay benefits above PPF compensation levels (Source: Pension Protection Fund Annual Report & Accounts 2016/2017).

2.8.8. The PPF already ranks in the top 10 list of UK pension schemes by asset value, but is currently less than half the size of the very largest schemes (Source: Pension Funds Online, 31 October 2016 and the Pension Protection Fund Annual Report and Accounts 2016/17). It will therefore be a number of years before the PPF becomes the largest pension scheme in the United Kingdom, unless of course one or more of the largest schemes themselves enter the PPF.

2.8.9. Since its inception, around 90 schemes a year on average have entered the PPF (Source: http://www.pensionprotectionfund.org.uk/TransferredSchemes/Pages/AllTransferredSchemes.aspx). If the entry of schemes to the PPF continues at the current rate with a similar average size of schemes, the PPF might be expected to manage around 2,000 schemes and £60 bn of assets by 2030. This would make it the largest pension scheme in the United Kingdom. If the number of DB schemes in the United Kingdom continues to fall at the same rate as currently then there will be around 3,000 eligible schemes left by 2030. These 3,000 schemes would be responsible for supporting the ever growing PPF through levy payments. There is therefore a concern that this burden could lead to further strains on the remaining sponsoring employers. It is also important to note that this analysis is based on averages. If one or more of the very large pension schemes (i.e. £20 bn+ assets) were to fall into the PPF, this could create a significant strain on the fund.

2.8.10. The PPF aims to be fully funded on a best estimate basis by 2030. At this point, the PPF is expected to have “no exposure to interest rate, inflation and market risks and with a risk margin against the risk of longevity improvements and future claims in excess of best estimate” (Source: PPF Long-Term Funding Strategy paper, August 2010). The risk margin was calculated to be 10% and was chosen such that in 2030 it would be sufficient in 90% of modelled scenarios to cover both the uncertainty in longevity and claims risk in excess of levy.

2.8.11. Article 8 of the EU Insolvency Directive requires that Member States ensure that “necessary measures” are taken to protect the interests of employees and former employees “in respect of rights conferring on them immediate or prospective entitlement to old-age benefits, including survivors’ benefits, under supplementary company or inter-company pension schemes outside the national statutory social security schemes”. The UK Government believed that provisions in section 124 of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 providing for unpaid pension scheme contributions to be met from the National Insurance Fund in the event of an insolvency adequately implemented this requirement in UK legislation (Source: House of Commons Library, Pension Protection Fund 1993–2003). However, two trade unions acting on behalf of the ASW pension scheme members were taking the Government to Court, alleging failure to apply the EU Insolvency Directive properly and this case had been raised in the House of Commons on several occasions. In one debate, Kevin Brennan, MP for Cardiff West, commenting on the impact this had had on ASW workers in his constituency said:

“The state has not exercised a proper duty of care on behalf of those people. The state did not insist on a proper health warning on occupational pensions—on the contrary, it encouraged workers to enter those schemes. The result has been a real injustice for a few who understandably feel bitterness, bewilderment and betrayal, and uncertainty for the many who, on hearing of the plight of the few, lose confidence in the whole occupational pensions system, when even the most rock solid ‘guaranteed’ form of pension fund turns out not to be worth the paper on which it is written, for thousands of people.

That is an injustice, not just a misfortune. Those people feel that they have been duped, and they have been.”

2.8.12. Many commentators at the time argued that the United Kingdom may have been in breach of the insolvency directive for years and following the ASW legal challenge, the Financial Assistance Scheme was introduced. The PPF was not created directly in response to the insolvency directive but it did of course significantly extend the protection available.

2.8.13. Grenville Holden Hampshire v the Board of the Pension Protection Fund (2016) EWCA Civ 786 (28 July 2016) covers a challenge to the level of compensation available from the PPF following the insolvency of an employer. The case contends that the PPF guarantee could not be considered to fall within the definition of the word “protect” used in Article 8. In the opinion of the Court of Appeal, several issues of EU law need clarification. The Court of Appeal has therefore decided to refer certain questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). It is likely that it will then take some time for the CJEU to undertake its consideration of the case.

3. Where are DB Pensions in the UK Today?

3.1. Introduction

This paper now considers the current environment for UK DB Pensions, including consideration of the trends observed since the introduction of scheme specific funding in 2005. In particular it considers how TPR’s views on IRM and employer covenant have been incorporated into the pensions landscape.

3.2. Pension Scheme Experience

3.2.1. Over the last decade the number of DB pension schemes in existence has fallen dramatically (see Figure 7). Ninety schemes a year are entering the PPF each year on average. There were 7751 schemes in total in 2006 and 5794 schemes in 2016 (an attrition rate of around 200 each year). The PPF has therefore become responsible for just under half of the 200 schemes a year that cease to exit. The remaining schemes will have been secured with an insurer (although not necessarily at full benefits for members) or will have been subject to mergers.

Figure 7 Scheme specific distribution of annualised investment return above gilts over the next 15 years

3.2.2. Over the same period, buyout deficits (i.e. estimated solvency deficits on wind-up) have increased significantly, as shown in Figure 8. This is the case despite £130 bn of contributions being made to these schemes (Source: How do we get out of this pensions ‘black hole’?, JLT Employee Benefits, 2016) and a quarter of the schemes no longer being in existence. The average deficit per scheme has more than doubled over the period.

Figure 8 Scheme specific distribution of annualised investment return above gilts over the next 5 years.

3.2.3. Over the same period (2006–2016) the average pension scheme’s investment strategy has changed dramatically with the proportion of assets allocated to equities falling from 61% to 30% and the proportion of assets allocated to fixed interest (bond) investments increasing from 28% to 51% (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Asset allocation for UK DB pension schemes (Source: The Purple Book: DB Pensions Universe Risk Profile 2016, The Pension Protection Fund)

3.3. IRM

3.3.1. As discussed in chapter 2, TPR is constantly reviewing and developing their views on pension scheme funding. In December 2015, TPR published its guidance on IRM. This guidance highlighted the importance of bringing together the three key risks, Funding, Employer Covenant and Investment Risk, that may impact the success or failure of a pension scheme. The IRM framework, “helps trustees identify and manage the factors that affect the prospects of meeting the scheme objective” (Source: Integrated risk management, The Pensions Regulator, December 2015).

3.3.2. It is important to note that TPR’s approach in this guidance is not entirely new. The guidance is simply a formalisation of much of the advice and guidance previously issued and builds on comments contained within TPR’s annual statements. As discussed in chapter 2, TPR’s annual funding statements have been building up to this for 10 years, with key words such as “risk” and “integrated” being continually referenced. Throughout this period, TPR have also included statements which would not look out of place in the IRM framework. In the 2012 annual funding statement, TPR encourages trustees to consider “funding, investment and covenant strands together”. In 2013, TPR stated that trustees should take “an integrated approach to addressing covenant, investment and funding risk”. And finally the year before the guidance was published TPR noted that they wished trustees to take a “proportionate application of an integrated approach to risk management”.

3.4. Employer Covenant

3.4.1. Employer covenant is the extent of the employer’s legal obligation and financial ability to support the scheme both now and in the future. When reviewing the employer covenant TPR expects trustees to consider the strength of the employer covenant both now and in the future, and what impact any potential changes in strength may mean for the long-term future of the pension scheme.

3.4.2. Within their latest guidance, TPR comment that employer covenant assessments should consider three key aspects – legal, scheme related and financial impact. Each of these impacts are discussed separately below. It is important to note, that whilst TPR recognises that pension schemes should adopt a proportionate approach, the trustees must ensure that they have documented their assessment.

3.4.3. Legal

In carrying out a legal review of employer covenant, the trustees must consider any legal documentation tying the employer to the scheme and what type of support the employer is legally obliged to give. The trustees are encouraged to review provisions within the scheme’s trust deed and rules; for example, how a scheme is positioned with the employer in the event of a Section 75 debt, how would the scheme be treated in the event of an insolvent employer and would they be entitled to enter the Pensions Protection Fund. TPR is keen that a scheme does not place reliance on informal support offered. Indeed, it is noticeable that there are an increasing number of pension schemes who hold contingent assets – possibly amongst those schemes with a perceived weaker employer covenant.

3.4.4. Scheme related

The trustees must consider how the characteristics of the pension scheme itself impact the employer covenant. In particular; how does the maturity of the scheme and the size of the scheme compare to the size of the employer supporting it. A large scheme which is supported by a small employer may be perceived to have a weaker covenant due to the potential for volatile future cash funding demands which may be placed on the employer.

3.4.5. Financial impact

The scheme should consider how the employer’s plans in the medium to long term will affect the scheme. The trustees should also consider the wider implications of the market the employer is operating in, and potential risks that they might face, which may impact on their ability to fund the scheme.

3.4.6. TPR assesses employer covenant within 4 covenant grades (CGs). These are detailed in TPR’s “Defined benefit funding regulatory and enforcement policy” issued June 2014.

∙ CG1 – Strong

“Very strong trading, cash generation and asset position relative to the size of the scheme and the scheme’s deficits. The employer has a strong market presence (or is a market leader) with good growth prospects for the employer and the market. The scheme has good access to trading and value if the employer is part of a wider group. Overall low risk of the employer not being able to support the scheme to the extent required in the short/medium-term.”

∙ CG2 – Tending to Strong

“Good trading, cash generation and asset position relative to the size of the scheme and deficits. Operates in a market with a reasonably positive outlook and the employer has a stable market share. Outlook is generally positive but medium-term risk of employer not being able to support the scheme and manage its risks.”

∙ CG3 – Tending to Weak

“Concerns over employer strength relative to the size of the scheme and deficit and/or signs of significant decline, weak profitability or balance sheet concerns and/or high vulnerability to economic cycle. No immediate concerns over insolvency but potential risk of decline.”

∙ CG4 – Weak

“Employer is weak, to the degree that there are concerns over potential insolvency, or where the scheme is so large that, without fundamental change to the strength of the employer, it is unlikely ever to be in a position to adequately support the scheme.”

(Source: DB funding regulatory and enforcement policy, The Pensions Regulator, June 2014)

3.4.7. While these categories are useful as a reference it is important to highlight that no two employer covenants are the same and categorisation is a difficult process. It is quite possible to have an employer with strong cash flows but a weak balance sheet and vice versa. Despite this, it is clear that, at least at the extremes of the grading system, a scheme with a strong sponsoring employer is in a very different position to a scheme with a weak sponsoring employer.

3.5. Does Practice Reflect the Theory?

3.5.1. Given the scheme specific funding regime and TPR’s emphasis on employer covenant and IRM, it might be expected that it should be possible to observe the influence of these factors in the approach taken for pension scheme funding across the United Kingdom. This paper therefore considers the latest available statistics published within “The Pensions Regulator – Scheme Funding Statistics (2017)”, considering the most recent valuation tranches 7 to 10. These valuations have taken place since 30 September 2011, and should take into account the continued formalisation of TPR’s guidance on employer covenant.

3.5.2. In particular, this paper considers some key indicators, which might be expected to show a link with the strength of the employer covenant:

∙ Key assumptions used in the liability calculations, in particular the discount rate

∙ Ratio of technical provisions to buyout liabilities

∙ Investment strategy

∙ Length of recovery plan

3.5.3. These have been examined in turn, in order to establish whether there is or appears to be a link between the employer covenant and funding and investment strategies.

3.5.4. It might be expected that the weaker an employer covenant is (or is perceived to be), the higher the level of prudence might be found within the assumptions used to determine the pension scheme’s technical provisions. TPR outlined in their June 2009 annual statement, if an employer is considered to have a weak covenant then trustees should target funding on a self sufficiency basis.

3.5.5. Discount rate assumptions

The discount rate is the key assumption used in determining a pension scheme’s technical provisions. Pension schemes with a stronger employer covenant might be expected to adopt a higher discount rate than those with a weaker covenant. Additionally, under the scheme specific funding requirements, it might be expected that strong employer covenants could be associated with pension schemes taking on more investment risk, which in turn would be reflected in into their choice of discount rate assumptions. Evidence from tranche 7, that is (valuations dates 22 September 2011 to 21 September 2012), would suggest that stronger covenants are associated with pension schemes using a higher discount rate than those with weaker covenants. However, the difference between these averages is only 0.2% per annum. For valuations occurring three years later (i.e. those in tranche 10) this gap narrows to less than 0.1% per annum. This would suggest that the strength of employer covenant is not influencing the choice of discount rate, as much as might be expected (Tables 1–4).

Table 1 Nominal Single Equivalent Discount Rate by Covenant

CG, covenant grades.

Source: Scheme Funding Statistics 2012–2017, The Pensions Regulator.

Table 2 Weighted Average Ratio of Technical Provisions to Buyout Liabilities (Schemes in Surplus and Deficit)

CG, covenant grades.

Source: Scheme Funding Statistics 2012–2017, The Pensions Regulator.

Table 3 Distribution of Return Seeking Assets Held by Covenant Grade (CG)

Source: Scheme Funding Statistics 2012–2017, The Pensions Regulator.

Table 4 Average Recovery Plan Length (Years) by Covenant

CG, covenant grades.

Source: Scheme Funding Statistics 2012–2017, The Pensions Regulator.

3.5.6. Ratio of technical provisions to buyout liabilities

This ratio gives an indication of the prudence incorporated into the technical provisions and takes into account the scheme specific characteristics. It can be seen that there is little difference between the covenant groups, again indicating that there is little allowance for employer covenant strength in the assumptions used.

3.5.7. Investment strategy

The distribution of return seeking assets held by CG is shown below. It might be expected that notwithstanding other factors, the stronger the employer covenant, the higher might be the level of return seeking assets held. It may be the case that strong employers have been in a better position to de-risk than weaker employers. But again, it can be seen that there is no material difference in the investment strategy between the different covenant bands.

3.5.8. Length of recovery plan

It might be expected that weaker employer covenants might be associated with longer recovery plans. An employer with a weaker covenant is unlikely to have unallocated funds to be paid on demand into the pension scheme. They are likely to require any spare funds for reinvestment in order to develop their business further, thus, hopefully, strengthening the employer covenant in the long run. TPR has recognised and supports this, and in their April 2009 statement highlighted that the best support for a pension scheme is a viable employer. By deferring the payment of contributions to the scheme, whilst still continuing to keep trustees informed of their longer-term plans, the pension scheme can benefit from a stronger employer covenant in the future. Evidence from tranche 7 (i.e. valuation dates 22 September 2011 to 21 September 2012), would suggest that weaker covenants are, on average, associated with longer recovery plans (10.9 years compared to those with stronger covenants at 6.4 years). However, for later valuations in subsequent tranches, this difference reduces.

3.5.9. This analysis is necessarily based on grouped data and there are many pension schemes across the United Kingdom that are making specific allowance for covenant and investment strategy (and the interaction between the two) when setting their funding strategy. However, the evidence from across the UK DB universe shows that the link between employer covenant, funding and investment, is not as strong as might be expected. In particular, it would appear that, overall, the differences between a very weak and very strong employer covenant are not so distinct and maybe scheme specific funding in many cases is not very scheme specific.

4. Basic Financial Economic Principles

4.1. Development of Financial Economics

4.1.1. Since the middle of the 20th century financial economics has developed and influenced all areas of finance. Although the work was not developed with pensions specifically in mind the approaches and insights are directly applicable to pensions. Many papers have shown how to apply these ideas to pensions, and some of the ideas have become common within the actuarial profession. However, it is debateable the degree to which many commonly accepted tenets of finance are followed in the running of DB pension schemes.

4.1.2. This chapter provides a brief overview of some of the key aspects of financial economics. It is not intended as a comprehensive overview of the subject. Many of these areas have been covered in more depth in previous papers (e.g. Bader & Gold, 2003; Bader, Reference Bader2004; Black, Reference Black1980; Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Gordon and Speed2001; Coronado & Sharpe, Reference Coronado and Sharpe2003; Cowling et al., Reference Cowling, Gordon and Speed2004; Exley & Armitage, Reference Exley and Armitage1997; Exley et al., 1997; Speed et al., Reference Speed2003; Tepper, Reference Tepper1981). Each idea is then applied to the provision of DB pensions. A good supplement is the “Pensions actuary’s guide to FE” (American Actuarial Society).

4.1.3. To some, the models that lead to these insights are supported by elegant mathematics, others have argued that these are over-elaborate constructions resting on unrealistic assumptions about human and market behaviour. Whatever your view, many of the basic principles can be demonstrated by simple thought experiments (such as those described in paragraphs 4.4.2 and 4.4.3 or at the end of paragraph 4.6.3). These insights continue to be relevant to the actuarial profession.

4.1.4. Care is needed in recognising that these are just models. They provide a framework and rationale for an approach. In the event that circumstances differ from the underlying assumptions there may be justification in amending the conclusions, but this paper advocates that actuaries (and other professionals) use these insights as a starting point and are prepared to justify reasons for adopting different approaches.

4.1.5. The key ideas covered below are:

○ The law of one price; arbitrage pricing

○ Modigliani Miller (MM) and the irrelevance of capital structure

○ MM allowing for tax

○ Risk and time horizons

○ Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and diversification

○ Agency theory

4.2. Financial Transactions and Value

4.2.1. Before considering these ideas it is helpful to consider the impact of a financial transaction. A priori, a financial transaction does not create value. A sale (or purchase) of a financial instrument transfers entitlements (and responsibilities) from one party to another for a given price, there is no value created.

4.2.2. This paper does not dispute that the buying party may be able to more effectively bear the risks associated with the instrument and this may lead to a better allocation of capital that in time is economically beneficial; however, the actual transaction is not value creative, it reallocates cash flows between parties.

4.2.3. There may also be transaction costs involved so third parties may share in the wealth reallocation.

4.2.4. Depending on the price and subsequent events, one party may be perceived to have been a winner from the transaction and the other a loser, but this is a result of subsequent events and the realisation of risk.

4.2.5. Why is this relevant to pensions? Many transactions involving pensions are financial: the benefits granted, the contributions paid, the allocation of the assets, the payment of transfer values or commutation lump sums, the payment of fees to assets managers and advisors. All these represent financial transactions that do not create value but reallocate value between different stakeholders involved in pensions.

4.2.6. When carrying out actuarial valuations and agreeing contributions, it may be useful to consider that the decisions made allocate value between the stakeholders (for more on this approach see Chapman, Gordon and Speed – Pensions funding and risk).

4.3. The Law of One Price; Arbitrage Pricing

4.3.1. Consider a share that trades on more than one exchange. There is an expectation that the shares on the different exchanges trade at the same price at the same time after allowing for any currency effects. This is effectively the law of one price.

4.3.2. It is also referred to as arbitrage pricing; if there was a difference between the prices then it would be possible to simultaneously buy the cheaper share and sell the more expensive share and make a risk-less profit. This would be an arbitrage opportunity.

4.3.3. The act of buying (additional demand for the cheaper share) on one exchange creates upward pressure on the price, while the sale (additional supply of the more expensive share) creates downward price pressure this leads to the arbitrage opportunity being eliminated net of transaction costs. This simple but powerful process of arbitrage pricing underpins many significant results in financial economics.

4.3.4. And why is this relevant to pensions? The approach can be generalised to consider streams of cash flows that are equivalent. If two sets of cash flows are the same, in that they provide the same amounts at the same time with the same risks then, by the law of one price, they will have the same value. This leads directly to the conclusion that a portfolio of assets that replicates projected pension payments has the same value as the said pension promises.

4.3.5. It is important to note that DB promises in the United Kingdom were issued without caveats of default risk. This suggests that a gilt replicating portfolio provides the base value of a DB pension. This also provides the corollary that the value of the pension promise, assuming that it is to be delivered in full, is unaffected by the backing assets.

4.4. MM and the Irrelevance of Capital Structure

4.4.1. In a seminal paper in 1958 (Modigliani & Miller, Reference Modigliani and Miller1958) MM showed that the capital structure is irrelevant to the value of an enterprise. This is referred to as the MM irrelevance proposition.

4.4.2. Consider a company that is 100% owned by a shareholder and has no debt. The company issues a bond which is financed by the shareholder and buys back some of the equity. The shareholder now holds 100% of the equity and the debt. In other words the shareholder still owns all the cash flows generated by the firm, this is the same position as they were in previously and so the debt equity split has not affected the value of the company.

4.4.3. The MM irrelevance proposition tells us that the financing of a liability does not affect its value. This can be applied directly to pensions. Consider two identical pension schemes where one holds all assets in gilts and the other holds all assets in equities. The assets are just collateral for the pension benefits. Unless the different investment strategies lead to different benefits being paid, this leads to the conclusion that the asset allocation within a DB pension scheme does not impact the value of the liabilities.

4.4.4. MM is highly relevant in today’s pension regulatory framework with the focus on IRM, in particular linking the employer’s covenant to the risk of the pension scheme. Since 2003 the debt on the employer is the full cost of securing the buy-out liabilities. This unequivocally makes pension promises a debt on the employer, and reinforces the notion that pensions should be considered as part of the capital structure of the sponsor.

4.4.5. This leads to the observation that issuing pension-debt and holding matching bonds is neutral on the capital structure of a company, but issuing pension-debt and funding (or part funding) with equities or non-matching assets adds to the leverage and risk of the company. This in turn suggests that IRM should explicitly consider the leverage impact of the pension scheme on the sponsor. This idea is far from new, for example, see the augmented balance sheet introduced by Treynor (1972).

4.4.6. In the event a pension scheme is not matched, the ultimate shareholder of the company is then exposed to additional leverage. This is not value enhancing as the shareholders could gain leverage themselves. Presumably the shareholder invests in the company to get exposure to the business and the cash-flows it generates rather than generic equity market exposure. There is also the issue of agency costs (see 4.8 below) that will detract value from the shareholder.

4.4.7. As with any model there are underlying assumptions, and a key one regarding tax will be considered in the next section, but for a non-tax paying entity (e.g. a charity) the MM model provides a strong rationale to fully fund a pension with matching assets.

4.5. MM Allowing for Tax

4.5.1. The MM model can be extended to allow for tax. As before issuing pension-debt creates additional leverage and hence risk unless the risk is fully hedged, for example, with bonds to cover the pension payments.

4.5.2. However, there is now the situation where the company is subject to tax. Interest payments are now tax deductible for the company therefore there is a tax advantage to issuing debt by the firm. The basic MM irrelevance proposition is amended as debt is a tax efficient way to finance the company (note wealth is not created but the value is distributed differently between the stakeholders including the tax authorities). However, there are limits to the amount of debt that a company can assume and therefore any leverage in the pension fund, holding risk assets to cover pension-debt, reduces the debt the company can issue directly.

4.5.3. Making the model more realistic in this way, by adding in tax, strengthens the argument for holding matching bonds in the pension scheme. The value loss from adopting tax inefficient arrangements can be easily calculated (see e.g. Ralfe et al., Reference Ralfe, Speed and Palin2004). Note that the gain is a certain annual gain and not dependent on a particular market outcome.

4.5.4. The argument can be extended to consider the tax rates applied to individuals but this serves to reinforce the argument as personal tax arrangements usually favour equities so it is more efficient for individuals to hold equities and for the company to optimise its capital position using debt.

4.6. Risk and Time Horizons

4.6.1. Markets set prices at which securities trade. However, implicitly pension work assumes that market prices are incorrect. This is often in the context of considering long time horizons and believing that equities are “better value” over the long term. These beliefs are often supported by Asset–Liability Modelling (ALM), for example, “funnel of doubt” graphs that show over time the higher expected return and small probabilities of under-performance.

4.6.2. There appears to be some confusion between the equity risk premium, which is well recognised and documented, and the implication this has for risk over time. To quote from Ralfe “Why hold equities in the pension fund”:

“The truism that equities are expected to outperform bonds in the long run supports the proposition that the longer the time horizon, the more likely that equities will outperform bonds. This is then often mis-interpreted as ‘the risk of holding equities versus bonds decreases the longer the time horizon’. Pension funds can apparently be rewarded versus other investors for their ability to take a long term view. This argument is fatally flawed; there is not a free lunch for those with a long time horizon.”

4.6.3. The risk of an equity portfolio relative to a bond portfolio does not decrease over time even if it’s expected return increases – indeed it is because of this. Again, a simple thought experiment, backed up by market data, can show this. The question can be asked “what is the cost of insuring against a portfolio of equities underperforming a government bond portfolio”? If the risk really does decrease then the cost of the insurance should decrease over time. However the reverse is true. Options markets show that the cost increases the longer the time horizon. Below are closing prices on 30 August 2017 for listed options on the S&P500 index (ref price 2458) with a 2,450 strike, showing increasing value for both puts and calls as maturity increases.

Whilst the above table shows only two years of data, the same pattern continues, however, long the table is extended (albeit there is limited market liquidity for long dated options). This is logical from considering the returns from a portfolio of equities combined with put options giving downside protection, versus a holding of cash combined with call options giving the upside of equity performance. After allowing for yield differences it is clear that these two portfolios must give the same return and therefore have the same value. So, if call options are going to increase with duration then so must put options. Clearly market pricing does not show that equity risk decreases over time. Claiming that this is the case is an example of market inconsistency (see Bodie, 1995).

4.6.4. It would be possible to argue that the equity protected portfolio still has the upside outperformance potential and so the cost of insuring the downside may lead to a better outcome. Selling the equity upside could be considered – if both the equity upside and downside are sold then this results in a risk free return, the same as the original bond portfolio. This is just a statement that markets price risk. All parties involved with pensions should appreciate that expected out-performance from assets, is market compensation for risk. An approach which is counter to this effectively claims that £100 of risky assets (equities) is worth more than £100 of bonds.

4.6.5. This is far from a theoretical argument. Total return swaps are commonly traded where the total return on equities can be exchanged for the cash accumulation on the same initial notional amount. The economist Paul Samuelson went further stating it was a “blunder if not a crime” for a fiduciary trustee to believe that equities’ risk decreases over time.

4.7. CAPM and Diversification

4.7.1. The CAPM is a standard model widely taught. Indeed many ALM models use ideas from CAPM. As always it is important to recognise this as a model and not a statement of how markets actually work, although CAPM often provides useful input in constructing a portfolio.

4.7.2. The key insight from CAPM is that risk can be divided into systemic and non-systemic (or stock specific) risk. Non-systemic risk can be diversified away and it is only systemic risk that is rewarded. This provides the rationale for diversification of portfolios; systemic risk is the determinant of expected returns (Sharpe, Reference Sharpe1964; Markowitz, Reference Markowitz1952).

4.7.3. Many generalisations of CAPM, including Arbitrage Pricing Theory have been developed; these are arguably refinements and in subsequent models the key aspects of diversifiable risk, and rewarded risk remain.

4.7.4. What is the application of CAPM and other market pricing models in pensions? Currently these models are often applied in asset allocation decisions within the pension scheme which is a highly scheme centric approach. A broader application would be to consider the end shareholder of the sponsor. If the sponsor is, for example, a cheese producer then it is reasonable to assume that the investors hold the shares to get access to the competitive advantage the company has in cheese production. A pension scheme that is not fully matched represents a geared position (short pension-debt and long equities) which is not value enhancing to the shareholder as they already have access to these investments. From a CAPM point of view the pension scheme is effectively trying to guess what the end shareholder’s risk/return preferences are which it does not have sufficient information to do. From the shareholder’s viewpoint this is value destructive as agency costs are incurred (see below).

4.8. Agency Theory

4.8.1. Agency theory describes how principals (e.g. shareholders) employ agents (e.g. corporate managers) to act on their behalf (see agency costs model of Jensen & Meckling, Reference Jensen and Meckling1976). While in theory the agents act solely on behalf of the principals, the agents may have their own goals and incentives that may be in conflict to the principals. There are also costs associated with employing and monitoring the agents.

4.8.2. Within pensions there are numerous areas where there is potential for principal-agent conflicts: the members/beneficiaries are principals in this terminology, trustees are appointed to act on their behalf, who in turn appoint advisors and asset managers, at each link in the chain there is potential for conflicting priorities and incentives.

4.8.3. From a corporate point of view the shareholders are principals, they have company management acting as their agents and again there is potential conflict. In particular, the metrics which corporate management are measured on may not be aligned to the most efficient running of the pension scheme. For example, if corporate management are rewarded according to performance against accounting metrics, then they can be encouraged to take sub-optimal risk within a pension scheme which results in a beneficial accounting outcome. Shareholders then suffer the double pain of over-rewarding corporate management as well as suffering sub-optimal risk.

4.8.4. If the agent-principal issue is put together with the realisation that any transactions involving a pension scheme involve a reallocation of resources it is then possible to identify significant potential conflicts.

4.8.5. Past pension practice has resulted in a curious situation where DB promises are being granted (where schemes are not closed) which are being undervalued and understated to the beneficiaries (imagine telling an employee their wage was £400 and then paying them £500). It is interesting to consider the different motivations and structural impediments as to why this is the case.

4.9. Are Pensions Different?

4.9.1. While all the above should not come as a surprise there is still often heard the refrain that pensions are different. While accepting that pensions have their own peculiarities, this does not invalidate what has been covered in this chapter. Rather, it is for actuaries and others who work in pensions to work out whether there are special circumstances, and how these amend the conclusions above.

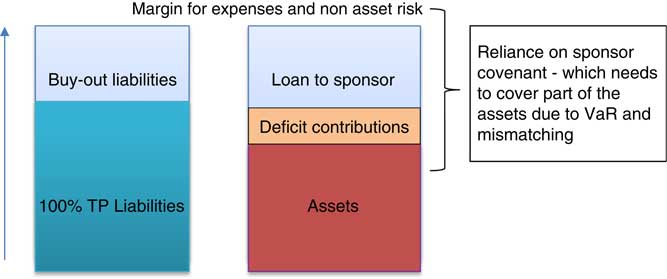

4.9.2. In many cases, rather than being different, pensions have provided good examples of how finance theory can work in practice. Examples include the valuation of guarantees, the hedging of LPI benefits and simple illustrations of whether cash equivalents offer value by asking how much would it cost to replicate the benefit forgone (i.e. how much should someone have to pay for an annuity that replicates the pension benefit foregone). One possible framework for thinking about DB pensions is illustrated Figure 10.

Figure 10 Possible framework for considering DB pensions.

4.9.3. This aims to demonstrate that a pension deficit is an unsecured loan to the sponsor (see Meulbroek, Reference Meulbroek2000). Parties engaged with pensions schemes should challenge themselves when taking decisions (or maintaining the status quo) to answer which stakeholder the arrangement benefits and whether suitable compensation for risk borne is being offered.

4.10. In Conclusion