Social media summary

Engaging with the SDGs and their ethical foundations from a broader perspective than Modernity.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the UN launched the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They had a long pedigree. After the devastation of World War II, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) put human dignity at the centre of development. Reports such as ‘Limits to Growth’ for the Club of Rome in 1971 alerted humanity to the finiteness of the planet. In the 1987 report ‘Our Common Future’ of the UN World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), the development aspirations were explored within what were then seen as environmental constraints. Agenda 21, an outcome of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Brazil in 1992, set guidelines for the transition to such a ‘sustainable development’ and already contained many SDG targets, as did the 2000 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Within science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and many other science-orientated initiatives by the UN and (inter)national organizations have made (environmental) sustainability and its links with development more prominent and specific. In recent years, contributors from the social sciences have been becoming more outspoken, connecting development, sustainability, governance and planetary boundaries (Biermann Reference Biermann2014; Rockstrom et al., Reference Rockstrom, Steffen, Noone, Persson, Chapin III, Lambin and Foley2009).Footnote i This reflects, first, a broader and more acute acknowledgement of the natural limitations to and feedbacks from human interventions, and, second, a more active interest within the social sciences and policy circles in human behaviour in relation to the (global) environment. A more explicit acknowledgement and elicitation of inputs from civil society – national and regional governments, cities, corporations and firms, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) – has been a concomitant move in this direction.Footnote ii

The objective of this paper is to present an evaluation of the SDGs from an ethical perspective. What is the underlying worldview? Are they ‘good’, and if so, why? And how can citizens promote their realization? Arguing that the SDGs represent the worldview of Modernity, I start with a description of Modernity and its opponents (Section 2). Subsequently, I introduce the worldview approach that has been developed and applied over the past decades in sustainability science (Section 3). Next, an overview of ethical theories and a positioning of these theories in the worldview framework is given (Section 4). This gives the necessary tools to assess the SDGs against a broader canvas of value and belief systems (Section 5). It is concluded that the ‘prison’ of Modernity has to be left if the SDGs are to be realized.

2. SDGs and the Modernity worldview

2.1. The SDGs as exponents of the Modernity worldview

The SDGs, the goals as well as the targets and indicators embody the worldview of Modernity.Footnote iii This statement begs the question: what is Modernity? Modernity denotes a series of developments that started in medieval Europe and led to what is called the Enlightenment on the waves of socio-political and religious changes and of scientific discoveries and technological applications in industrial capitalism. It spread from Europe, in parallel with colonialism, to its ‘offshoots’ and other parts of the world. It reached its apparent apogee in the second half of the twentieth century as the High Modernity of the post-war era, followed by Late Modernity and Post-Modernity since the 1980s.

Without any claim to completeness, I suggest at least four features of Modernity.Footnote iv The sequence of the list does not imply causality – it has clearly been a process of multiple interacting cause-and-effect events. First is the scientific method of empirical reductionism, with:

• The aim of generating context-independent statements and abstractions;

• The aim of eliminating religious superstition (Entzauberung) and distrust of personal knowledge; and

• A separation between object and subject, and between fact and value.

Founded on the belief in the universality of logic and reason and the evidence of sense observations, the scientific method has a preference for abstractions and an aspiration for universalism. Knowledge based on the personal and particular is judged as unreliable and often seen as superstitious; it is relegated to the altogether different realm of the inner and subjective, as against the outer and objective. Alongside this, the classical-medieval idea of an ordered universe and a telos orientated towards the whole was replaced by a new relationship between the community and the individual, and later on between personal freedom and state and corporate control. Modernity also meant a shift in the view of nature: from a God-created work of art, nature became a resource for technical exploitation and the construction of a human-created world. These changes have not been sudden or final: it was a slow and multifarious process with remnants of pre-Modernity still remaining.

A second feature of Modernity is a continuous process of rationalization, formalization and standardization in a quest for increased efficiency and productivity – the ‘ruthless logic of Modernity’.Footnote v It is directly and indirectly a driver of globalization and of increasing uniformity and concentration of knowledge and power.

A third aspect of Modernity is the emancipatory ideal of bringing progress and well-being to all people based on the imperatives of justice, equality and participation. This ideal, already visible in the Reformation with its emphasis on the worth and responsibility of the individual, voiced the desire to be liberated from inequality and repression and the conviction that the revolutionary forces of science and technology would free mankind from slavery and drudgery, as well as from religious and other superstitions. Liberalism, socialism and communism were the clearest political manifestations of this European ideal, and throughout the nineteenth century these were in conflict with reactionary forces of the feudal aristocracy and church (Evans, Reference Evans2017). The underlying strain between individualism and collectivism is still with us in the discourse on the role of market versus state (e.g., see Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2005; Sen, Reference Sen1999; van Bavel, Reference van Bavel2017).

Fourthly, and relatedly, the Modernity worldview has a belief – legitimated by science and technology – in the predictability, planning and control of societal processes by bureaucrat–manager–experts. The natural science methods crept into the non-natural sciences and gave rise to expectations of explanatory ‘laws’ governing men and society – notably in economic science. It also altered the political order: although royal and aristocratic elites were formally still in power, the sovereign nation-state and its government and bureaucracy became the preeminent political unit in an increasingly liberal-democratic setting. In twentieth-century socialism and capitalism, the administrative state and the multinational corporation have become the counterparts.Footnote vi

These features of (High and Late) Modernity are easily recognized in the SDGs and targets. The (European) welfare state is the model to be followed, with its emphasis on protection and provision for in some way disadvantaged persons.Footnote vii It is also noticeable in its emphasis on the targets of economic yardsticks and performance such as the poverty line, gross domestic product (GDP) growth, (increase in) productivity and efficiency and elimination of trade barriers, job provision and access to financial services. There is an enormous – though implicit – role for the state or government: universal access to food, water, energy and housing services; building up health, education and urban infrastructure; promotion of science and technology; reduction of pollution and waste generation; management of marine and terrestrial ecosystems; and international monitoring, regulation, law and negotiation. These goals and targets make up a set of lofty ambitions, for sure – but there is a bias in the direction of (Late) Modernity values, beliefs and concerns. This causes, on the one hand, a possibly dangerous neglect of forces that prohibit their realization, and, on the other, an incompleteness of what makes up ‘the good life’.Footnote viii

2.2. Modernity and its opponents

Modernity has been a source of tremendous change in the world, for better and for worse. Human quality of life has benefited enormously, satisfying and creating an ever broader spectrum of often basic needs and bringing to fruition broader notions of well-being, including law and justice, democratic accountability and human rights. It has brought great advances, such as a near doubling of average life expectancy, which no other civilization has achieved and are sometimes too easily dismissed.Footnote ix It is the promise of similar and more within the SDGs that makes them representative of the Modernity worldview.

However, Modernity in its appearance of industrial capitalism and socialism/communism has created large unintended, unforeseen and undesirable side-effects and feedbacks as a result of the exploitation of the human and natural world at unprecedented speed, scale and rigour. Less tangible side effects are the concentration of state, corporate and financial power, the loss of diversity in nature and culture, and several intractable long-term and global risks that are reminiscent of Goethe's Zauberlehrling. Many of the costs and risks were ignored, denied or externalized, and in many places they still are.Footnote x There have always been undercurrents of resistance, opposition and doubt. From the start, Modernity's claim to knowledge, rationality and power and the process of ‘development’ has been contested from diverse corners, as is manifested in numerous resistance and opposition movements often given the label ‘Romanticism’. Aristocratic elites bemoaned the tendency towards materialist lifestyles; workers opposed harsh working conditions and unfair distribution of rewards; religious persons and artists feared erosion of community and ethical guidelines; and nature lovers and consumer groups started to resist the destruction of natural areas and the pollution of air and water (Caradonna, Reference Caradonna2014; de Vries, Reference de Vries2013).

One realm of resistance stems from colonialism. Although it often went with the blessings of Christian schools, transfer of technical skills and abolition of cruel customs and practices, colonialism and its sequel in neo-colonialism have tainted Modernism in many parts of the world and inspired opposition and resistance in a variety of social movements up to the present day (e.g., see Appadurai, Reference Appadurai2005; Castells, Reference Castells1997; Easterly, Reference Easterly2006; Sachs et al., Reference Sachs2010; Shiva, Reference Shiva1989). In reaction to a global consumer culture and worldwide environmental destruction, some choose protection by exclusion, as in ethnic and religious fundamentalism; others aim towards the construction of identities that bridge the local and the global, as in the environmental and feminist movements.Footnote xi Simultaneously, the legitimizing identity of the nation-state and its institutions has been eroded by globally operating corporations on the one hand and by citizen and revolutionary movements on the other, both reinforced by the advances in information and communication technology.Footnote xii

Modernity has also been under siege from developments within science. Newton's mechanical laws broke apart in the very small and the very large, and in physics, even subject (as observer) and object (as observed) are connected. Advances in mathematics in combination with more and faster computing power made it clear how extreme the simplification of the real world is in the mechanistic worldview of early Modernity (de Vries, Reference de Vries2010, Reference de Vries2013). Within philosophy and sociology of science, the insight that scientific knowledge is a time-, value-, interest- and culture-determined social construct gained ground (e.g., see Tarnas, Reference Tarnas1991; Toulmin, Reference Toulmin1990). Postmodern thinking had arrived.

A variety of societal forces has thus been at work for the last four or five decades in a transformation process away from the still dominant worldview of Modernity. Inconsistencies, controversies and paradoxes abound in the resulting patchwork of objections and refutations made in the name of subjective truth, religious revelations, animal sensibilities and other ‘irrationalities’. It is a rebalancing act in which the subjective and the immaterial are regaining legitimacy and the relation between individual and collective is reorientating itself. It is a world of several, often competing and conflicting master narratives (Appadurai, Reference Appadurai1996). It justifies the question of whether Modernity as a worldview, and thus the SDGs, can still give humanity the necessary guidance. Before addressing this question with respect to ethical aspects, I introduce the worldview approach as a way of framing it.

3. The worldview approach

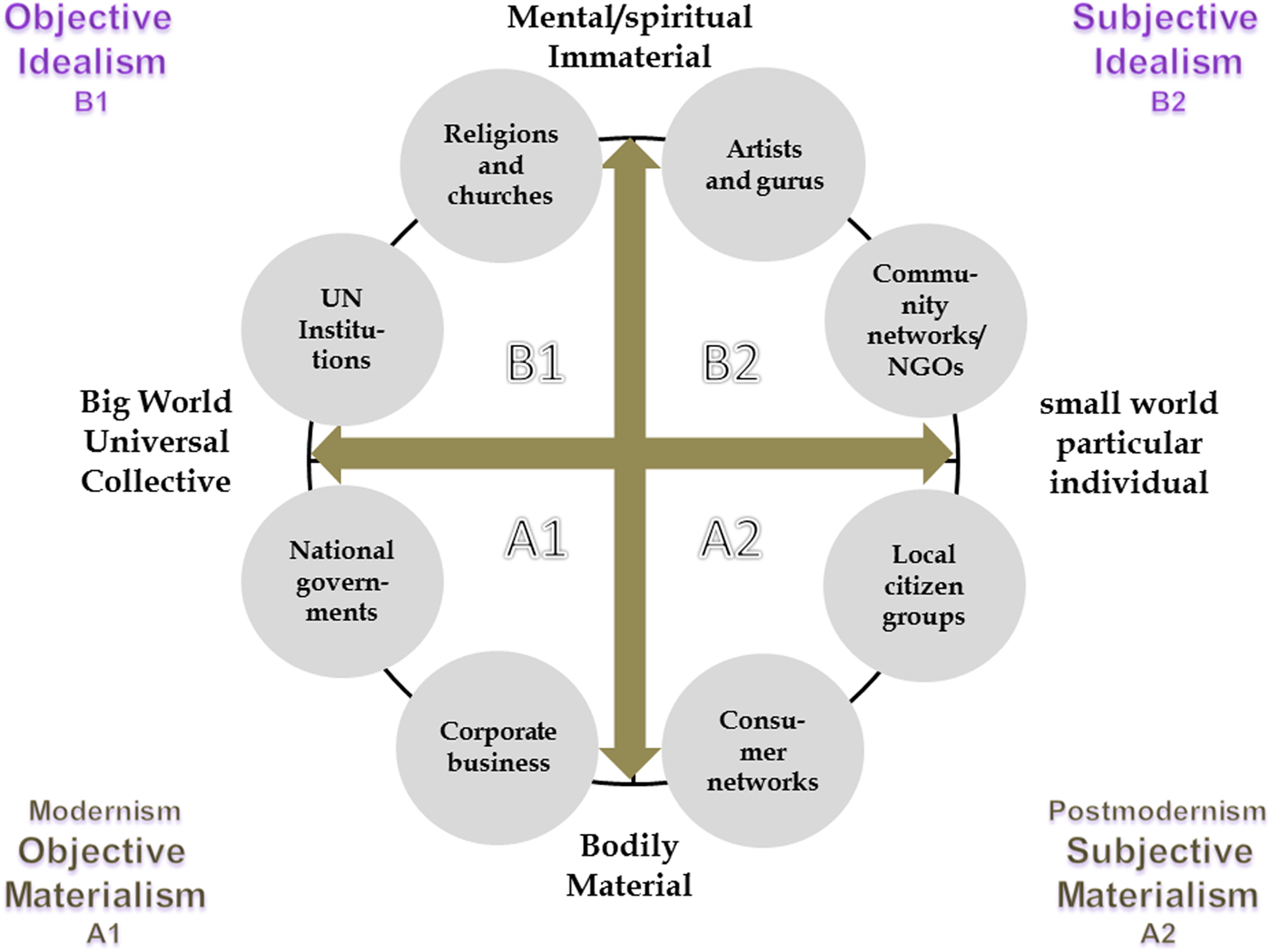

I propose a formal framework to investigate the role of values and beliefs in sustainable development discourses and practices: the worldview approach. A worldview is defined as a combination of a person's value orientation and a person's beliefs about how the world functions.Footnote xiii Two dimensions or axes are distinguished that make up the worldview space as shown in Figure 1. They represent polarities and, as such, create tensions in (human) lives, rather than sharp dichotomies or rigid distinctions. The first, horizontal axis represents (the tension between) individual and group or collective. The individual is primarily the biologically separate member of the group (family, tribe), and only later in human evolution did the individual gain significant content and meaning beyond immediate sense experiences and actions (Fukuyama, Reference Fukuyama2015; Siedentop, Reference Siedentop2014). Epistemologically, this axis depicts the contrast between particularism and universalism. It is recognized in Hegel's opposition between the subject(ive) and the object(ive) and in Weber's positioning of the individual against the collective.Footnote xiv In (neoclassical) economic discourse, it appears as individualism versus collectivism, with the market presented as a universal mechanism of exchange connecting the two. In a religious context, the horizontal relationship between individual and community was an essential part of the triad with God and at the core of medieval ethics and its Greek ancestry. It is prominent in the work of theologians like Buber and Levinas and a crucial aspect of Mahayana Buddhism. In a more secular setting, it permeated Western psychology in the search for the ‘laws’ of the psyche and its archetypes. This dimension thus represents the notion that, on the one extreme, individuals live and act in a ‘subjective’ and particular world in which locality and contingency determine life, whereas on the other extreme, (perhaps the same) individuals are living and acting in a world believed to follow an order experienced as ‘objective’ and universal.

Fig. 1. The two dimensions or axes in the worldview approach, with an indication of agency (van Egmond & de Vries, Reference van Egmond and de Vries2011). The labels A1, A2, B1 and B2 are from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Emission Scenarios (Nakicenovic & Swart, Reference Nakicenovic and Swart2000). NGO = non-governmental organization.

The second, vertical axis represents (the tension between) material and immaterial and between body and mind (or spirit or soul). It manifests as a gradual unfolding of human beings into interiority and is at the root of religious awareness and philosophical inquiry. Plato distinguished senses and ideas. Aristotle put participation in the polis and metaphysical contemplation above the exigencies of material and family life. Hegel distinguished the materialistic and idealistic. It is quintessential in the Eastern dharma and in the Abrahamic religions, as well as in ‘New Age’ philosophy (Malhotra, Reference Malhotra2011; Naess, Reference Naess1989; Schumacher, Reference Schumacher1977/2011; Wilber, Reference Wilber1997). In Western psychology, it is fundamental in the prominent theories and explicitly hierarchical in the humanistic psychology of Maslow. Most traditions and authors consider the ‘higher’ to be levels superior in various ways and assume that individuals have different talents and propensities in expressing themselves along this axis.

The worldview space offers a framework for understanding societal dynamics in terms of the construction and maintenance of collective narratives that restrain or inspire the legitimacy of moral rules and power relations.Footnote xv The lower-right corner of Figure 1 is given the name of subjective materialism (A2). It is the world of everyday agency: birth, sex and death; food and water procurement; and shelter and other basic material needs and skills. It is the place of pleasure and pain, of enjoyment and suffering. Organization at village and tribal levels and into higher, often hierarchical structures (tribes, communities) leads to a variety of forms of political order – the lower-left corner of Figure 1, representing objective materialism (A1). It is the blunt power of kings, dictators, warlords and merchants, imposing worldly order, offering legitimizing myths and appropriating the labour and skills of individuals for their benefit via forced labour, taxes and so on, as well as appropriating nature's resources. In Modernity, villages become (mega)cities and communities or (nation-)states; kings and feudal lords become governments and bureaucrats in state institutions; and warriors and merchants mutate into the military and business elites.

Simultaneously, individual people develop more differentiated and reflexive emotional, mental and spiritual states – a move towards the upper-right corner of Figure 1, representing subjective idealism (B2). This is a well of creativity in which individual artists, writers, musicians, gurus and prophets create and express novel experiences and insights, individual conscience and spiritual revelations. Through dissemination of shared views, this can develop into movements that replace the dominant religious and cultural order, as shown by the upper-left corner of Figure 1, representing objective idealism (B1). In Modernity, the high priests are the representatives in organized churches and the royal and aristocratic families become (global) religious, political and corporate elites.

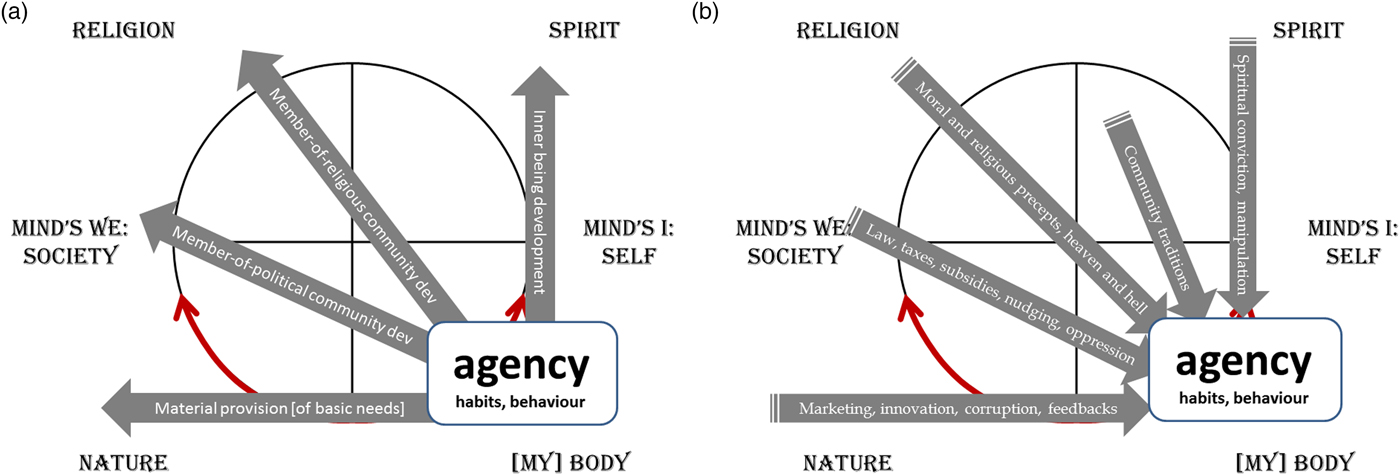

I propose using the worldviews as a tool to assess the SDGs in an inherently plural world. The agency of individuals in their everyday lives is the material manifestation of outward developments and inward influences and is at the core of the SDGs, although their top-down formulation tends to disguise this (Figure 2). Upon maturing, the individual human being will reach out into the physical world for resources to fulfil his or her needs. He or she will also develop membership of the political and religious communities to which he or she belongs, and he or she will develop an inner awareness and being. At the same time, outside forces start to influence him or her: resource supplies may change; marketing will create new needs; laws and regulations will constrain individual freedom in the name of common interests; religious precepts and rituals will exert moral control on individual actions and, similarly, community traditions and customs restrain individual freedom; and spiritual convictions can reorientate individual behaviour. Personal agency is a dynamic process of development within the creative tensions of the individual–collective and the material–immaterial, and it is embedded in a historical, biogeographical and socio-cultural context. Although dichotomies such as those proposed here are simplifications, they are helpful as a heuristic framework to identify the diversity in values, beliefs, ideals and interests with respect to the (ethical aspects of the) SDGs (de Vries, Reference de Vries2013). For a correct interpretation, it is important to appreciate the difference between what is experienced subjectively and what can be described objectively.Footnote xvi

Fig. 2. Unfolding development of the (a) individual and (b) outside forces working upon the individual. The lower right corner represents the ‘pool’ of individuals with different characteristics (genetic, psychological, socio-cultural and environmental). dev = development.

4. Ethical theories

4.1. Roots of moral behaviour

The SDGs represent ideals and ambitions for the world and point at a path towards a collectively desirable state of the world. Ethical statements are about alternatives for future action and the choice between them on the basis of values, motives and outcomes.Footnote xvii As such, the SDGs are or imply ethical statements that concern both dimensions of worldview space.Footnote xviii An early ethics might be called hero morality, although one could also speak of survival morality. Leading warriors, excelling and competing in the ‘virtue’ of battle, became part of shared stories and myths, with courage, honour and loyalty as the main virtues. Physical and social as well as military, strategic and psychological preponderance mattered most – the ‘right of the strongest’ (lower-left corner of Figure 1). Priestly hierarchies complemented the hero morality with a religious ethic, consisting of rules and commandments in connection with an imagined supernatural world of gods and demons and the natural environment (upper-left corner of Figure 1). The proclaimed virtues were centred around non-worldliness, purity and compassion.

Within the worldly and religious order, there was a taboo morality among the population at large – farmers, merchants, craftsmen – with obedience as an important virtue (lower-right corner of Figure 1). Their instincts and passions had to be channelled and constrained in the form of strictly prescribed social roles embedded in traditions and institutions. These mostly concerned matters of common interest, such as practices and beliefs about food and diseases, taboos around birth, gender, pregnancy and death, rules about ownership and trade and ways to settle conflicts and enforce obedience. It served the purposes of safety, cooperation and conflict resolution within the group and it constrained the brute force of the powerful. Fear of punishment and retribution will have been among the motives for ‘good’ behaviour.

In the course of history, individuals have attempted to escape social hierarchies with their prescribed roles, rules and practices and develop individual ‘selves’ with personal desires, emotions and beliefs (upper-right corner of Figure 1).Footnote xix Ethics appears in the sense of personal awareness and conscience – a spiritual ethic. It is an important aspect of medieval mysticism and the Protestant ethic. In the Eastern dharma traditions, it involves the orientation on individual self-realization and on practical methods to reach it. Spiritual authority resides in living masters, not only in scriptures, and there is a large diversity in gods, rituals and practices without a claim to universality (Malhotra, Reference Malhotra2011). It should be noted that, in all religions, the everyday reality can often differ significantly from the avowed ideals, as with the secular ideals of chivalry and justice. The important thing is that many people still live in a premodern world in which traditional morality and ethics prevail and are not to be overlooked in the implementation of the SDGs. In the following subsections, I take a closer look at the ethical schools and theories in Modernity.

4.2. Industrial Era ethics: libertarianism and utilitarianism

Ethics and morality in the agrarian societies of early medieval Europe evolved from a variety of tribal systems into rather widely shared values and beliefs that were founded on Judaeo-Christian traditions and classical Greek philosophy, notably Aristotle. From the sixteenth century onwards, it gradually changed into what I call Industrial Era and Enlightenment ethics. The former had two main streams: libertarianism, which reflects the growing desire for freedom from oppressive worldly and clerical elites; and utilitarianism, which represents the growing focus on material wealth among the bourgeois class.

Libertarianism Footnote xx emphasizes the rights and freedom of choice of the individual in matters of religion, opinion and lifestyle and protects individual autonomy against collectivizing tendencies on behalf of king, state or church. Justice is interpreted in terms of equality with respect to (legal) entitlements. Freedom is about individual freedom, with the political implication of deregulating business and reducing the role of government. With the disappearance of social virtues such as trust, acceptance, restraint and sense of obligation – sustained by, for instance, Christianity and socialism – there is no longer an incentive to practice civic duty or cooperate for the collective: “In the modern liberal view, the socioeconomic system is seen as amoral … in an individualistic society, morality is for the most part an individual matter” (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch1977, p. 119).

Utilitarianism evaluates the actions of an individual on the basis of their consequences in terms of utility.Footnote xxi Attraction to pleasure and aversion to pain are considered the only motives for human agency. Its ethics are relative and consequentialist: which action should be taken? Calculus is the method employed, evaluation is in terms of outcomes and the practical ethical rule involves maximizing the difference between pleasure and pain. In a business/corporate setting, the same calculus is used to maximize efficiency or profit. In an attempt to extend this into the public domain, the concept of aggregated social utility has been postulated, which then should be maximized: the greatest happiness of the greatest number.Footnote xxii

Can Industrial Era ethics provide guidelines for the implementation of the SDGs? Both utilitarian and libertarian ethics are practices of the rational and emancipated individual in Modernity. Libertarians and (neo)liberals are natural protagonists of the SDGs, such as the anti-discrimination and anti-abuse (#5, #16) targets, but without a legal framework and a state to enforce them, these goals remain ineffective. Being indifferent to the outcomes in terms of income (in)equality, they will not engage with many of the SDGs. Indeed, by advocating a minimal public domain and by promoting and justifying privatization and monetization of the (natural) commons, a (neo)liberal ethic tends to be detrimental to several SDGs.

Utilitarianism in its narrow form accepts consumer behaviour as the optimal outcome of rational choice on the basis of a coherent set of preferences. The basic assumptions are that (access to) markets exist, that everything can be expressed in prices and that prices settle issues of justice and (in)equity.Footnote xxiii The emphasis in the SDGs on market access, taxes and subsidies, consumer protection and regulatory measures in relation to food distribution (#2), water (#6) and energy (#7) targets as prime policy tools reflects the importance of utilitarian ethics in their formulation. In practice, arguing about complex issues such as the costs and benefits of genetically modified organisms in agriculture (#2) on the basis of risk–benefit calculus upholds an illusion of rational decision-making by a collective of people about incommensurable items.Footnote xxiv To make matters even more complex, the psychology and ethics of (social) utilitarianism have potentially serious political implications, such as sacrificing the (basic) individual rights of minorities that run counter to libertarian values (Sen, Reference Sen2010; van Asperen, Reference van Asperen1993).

4.3. Enlightenment ethics: the transcendental institutionalism of Kant and RawlsFootnote xxv

With the rise of the Renaissance and humanism, philosophers increasingly sought to anchor morality and ethics in objective truth and logic in an attempt to construct a universal theory about what constitutes good and bad conduct. A major attempt was undertaken by Kant, who considered reason to be the basis for ethical principles and put human dignity and rights at the centre of ethics. His conception of reason is that it commands the will and legitimizes an action as a good in itself, regardless of circumstances or consequences. To the question, ‘What should I do?’, Kant offered a universal principle: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can and, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law” (Sandel, Reference Sandel2010, p. 120). Kant's ethic is absolute and deontological (duty based), not relative and outcome orientated as in utilitarianism (van Tongeren, Reference van Tongeren, van Melle and van Zilfhout2008, personal communication 2018).Footnote xxvi

The Kantian position has been elaborated 200 years later by Rawls in his book, A Theory of Justice. A thought experiment led him to postulate equal basic liberties and social and economic equality of opportunity as principles of justice, the first one in rejection of (social) utilitarianism and the second one in rejection of free market-based libertarianism. For various reasons, corrections for social and historical contingencies and the natural distribution in abilities and talents are needed. Rawls therefore proposed the ‘difference principle’, which takes the needs of members of the community as the kernel of distributive justice.Footnote xxvii This position is incommensurable with the entitlement approach in libertarianism, but not necessarily with a basic needs-orientated social utilitarianism.

Many SDGs reflect these humanist ideals with their emphasis on reason and human rights and an egalitarian ethic of justice as fairness. This has important ethical implications. For instance, if you expand Kant's maxims to non-human nature, animals and plants have to be respected for their intrinsic value (SDGs #14 and #15). Taking Rawls’ difference principle seriously asks for far-reaching actions with respect to the SDGs, such as on poverty (#1) and reducing inequality (#10). Framing ethics in terms of a social contract also emphasizes the importance of governance and institutions (#16). The twentieth-century American New Deal and post-war European welfare state have probably come closest to these ideals, but their foundations – individualism, rationality and secularity – are no longer considered as naturally universal. Mainstream ethical schools have been criticized for their emphasis on the individual, the overrating of reason and the dismissal of religion.Footnote xxviii Old and new strands of thought have (re)appeared, which is the topic of the next subsection.

4.4. Development and eco-spiritual ethics

The economist Sen (Reference Sen1999, Reference Sen2010) has criticized Industrial Era and Enlightenment ethics for not considering the real-world heterogeneity of people's circumstances, motivations and valuation of ‘the good life’. Utilitarianism neglects the distribution of outcomes and reduces well-being to utility; libertarianism is indifferent to the loss of substantive freedoms; institutional transcendentalism has too much emphasis on universals.Footnote xxix Sen argues for a broader notion of quality of life, with more attention given to the qualitative aspects and diversity of well-being and for dialogue on public–private (im)balances. He reformulates development as the freedom of individuals ‘to do things one has reason to value’, a more positive form of liberty, and he introduces capabilities (the options available to people) and functioning (the actual choices facing people to operationalize them).Footnote xxx The SDGs incorporate Sen's approach to some extent in their recognition of public goods (e.g., #3, #4 and #13–16).

Another area of critique and a new strand of thought has been the attitude towards non-human nature. Nature has always been seen and used as a resource, satisfying basic as well as luxury desires, and (access to) resources plays a huge role in human lives. But the impacts of humans on the environment and their relationships with other living beings were not or were only indirectly part of ethical reflection, mostly as a natural consequence of war or the price of progress (de Vries & Goudsblom, Reference de Vries and Goudsblom2001; McNeill, Reference McNeill2000).

The reasons for the emergence of such an eco-spiritual ethics are at least threefold.Footnote xxxi First, and in its most visible and direct form, it started when the side effects of industrialism began to affect (the expectation of) ever-growing well-being among the populations of the West. It manifested as pollution of lakes and rivers and of air and soils, as urban sprawl and huge landfills and as the disappearance of forests and destruction of landscapes. Environmental science and technology-based policies appear to resolve most of the local and short-term impacts, or at least offer the prospect of doing so. Second, the long-term and global-scale dynamics of exponential growth of people and activity indicated the possibility of long-term negative feedback upon humans themselves in the form of, notably, the accumulation of persistent pollutants, climate change and the loss of biodiversity (de Vries, Reference de Vries2013; Meadows et al., Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens III1972; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockstrom, Conrnell, Fetzer, Bennett and Sorlin2015).Footnote xxxii The underlying systems view of ‘planetary change’ leads to new branches of science and to new ethical questions (Latour, Reference Latour2017; Jamieson, Reference Jamieson2014). Third, the depth and scale in space and time of the changes resulting from human interventions in ‘the Anthropocene’ did and do induce a (re)discovery of other perspectives on (the place of humans in) nature, beyond the confines of Modernity (Convery & Davis, Reference Convery and Davis2016; Pojman, Reference Pojman1994).Footnote xxxiii As science reveals the amazing intricacies of the web of life, a new spiritual ethic is evolving – as expressed in deep ecology, Eco-Buddhism, among others – and mixes with a renewed appreciation of traditional cultures and non-human life and with anti-Modernity undercurrents such as ecofeminism (cf. Section 2.2; Castells, Reference Castells1997; Singer, Reference Singer1975).Footnote xxxiv It is visible in the SDGs on (inter)national nature protection and preservation (#14, #15). These critical developments in Late Modernity are partly reflected in the SDGs. SDGs #11–15 connect ecological concerns with poverty and (in)equity and lead to novel notions such as inclusive wealth, green growth and green technology, nature-friendly agriculture, ecosystem services, etc. However, no mention is made of the tensions and trade-offs between economic growth and sustainability, although the very changes that threaten ecosystems and biodiversity (i.e., the expected increase in extensive and intensive use of land, water and air sources and sinks [#13, #14]) clash with several of the development-orientated goals (#1–4, #6 and #7). This leaves many value and ethical issues undiscussed and creates a sense of unrealism.

4.5. Virtue ethics

Another critique draws on ancient Greek and medieval philosophy, with MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre1981/2011) as an important exponent of this. He rejects utility, human rights and efficiency as moral fictions or pseudo-concepts and offers another ideal of ‘the good life’.Footnote xxxv Virtues are embedded in practice, narrative and tradition. Performing practices yields goods that are externally and contingently attached to the practice; they are usually individually owned and therefore objects of competition. It also yields goods that are internal to the practice; these cannot be detached from the practice, and participating in the practice is an essential experiential part.Footnote xxxvi Second in MacIntyre's conceptualization of the virtues is the notion of a narrative: a human life should be understood as a unity. It has intentions, beliefs and history – it is a narrative without which there is no intelligibility and accountability and therefore no personal identity. The quest for this unity is the good life for man and is always an education.Footnote xxxvii Third is the embedding of practices and narratives in a socio-cultural tradition. Exercise is crucial in sustaining the relevant virtues, but the internal goods and individual narrative have to be part of a larger tradition that provides practices and individuals with the necessary historical context.

Virtues are thus conceived as inherently social, defining our relationships to others performing the practice. This view, which also exists in traditional cultures, cannot be reconciled with a libertarian or utilitarian ethic because they acknowledge neither the distinction between internal and external goods nor the existence of a personal telos in a community context. Moreover, virtue in public life is a matter of law and calculus in liberalism and (social) utilitarianism (i.e., of institutions). But the prime concerns of institutions are external goods such as money, status and power, which are often in conflict with practicing virtue ethics.Footnote xxxviii For instance, the intrinsic motivations of a medical doctor or teacher, such as self-direction and benevolence, are crucial in health and education (#3, #4), and yet will be overlooked or dismissed in a libertarian–utilitarian approach.

5. Realizing the SDGs: going beyond Modernity

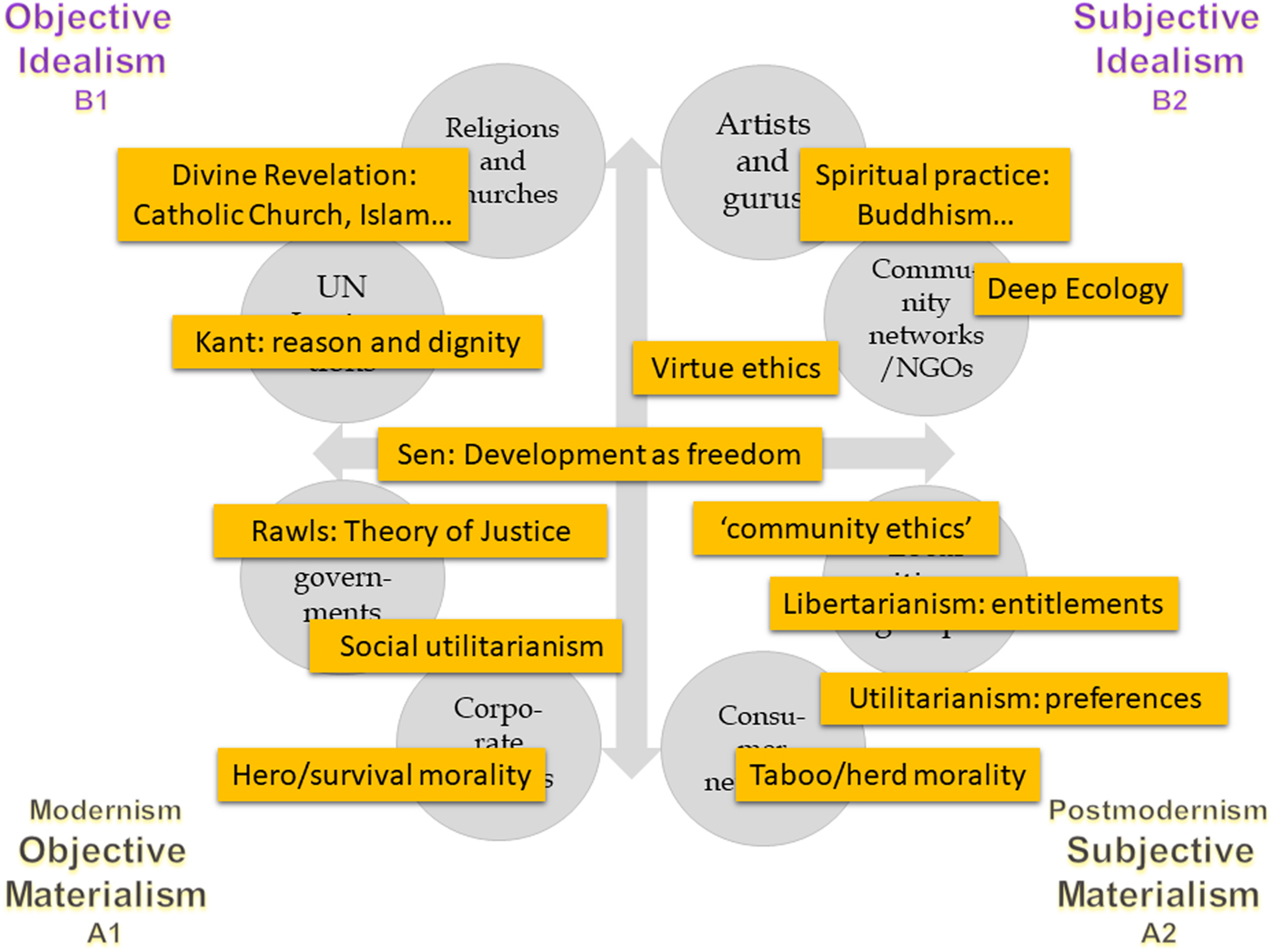

5.1. Ethics in worldview space

From the previous discussion of Modernity, worldviews and ethics, I argue that the SDGs represent the worldview of Modernity and are therefore partial and one-sided, with ‘the good life’ formulated as an abstract Enlightenment ideal and targets formulated in a libertarian–utilitarian setting. This can be illustrated with an associative positioning of the various ethical schools in worldview space in Figure 3. The utilitarian ethic is in the lower-right corner, from where utility-based consumer decisions are connected with corporate and state bureaucracies and competitive (global) markets in the lower-left corner, with pockets of hero and survival morality in oppressive political–military hierarchies. This is the economic, military and sports arena. Higher up the vertical axis, the right side is the locus of the hugely diverse, contextual ethics in personal traditions, customs, beliefs and values, including spiritual convictions, artistic expressions and power and love. These are linked to the collective through civic society's (local and global) laws and forms of governance and the moral rules in religious scriptures and institutions in the mid-left and upper-left corner. This is the political, cultural and religious arena.

Fig. 3. Ethics in a worldview framework: an associative positioning of ethical schools within the dimensions particular–universal and material–immaterial. NGO = non-governmental organization.

The dominant narrative that goes with the SDGs is that the world should and will, in the name of universal human rights and the desirability of a modern lifestyle, follow a path of continuous material prosperity (measured as GDP per capita). It is a transition from community-based and traditional rules and practices towards a welfare state. The rich get their novel technologies and adventures, the poor get their basic needs satisfied, and in due course everyone will benefit.Footnote xxxix People are primarily seen as behaving and do behave as consumers, and ‘the good life’ is about personal health, wealth and beauty, sensual pleasures and joy and individual achievement, adventure and competition in sports and business. Open markets and unhindered (‘free’) trade in combination with scientific–technological innovation and capitalist entrepreneurship are the drivers.Footnote xl

This narrative is considered unrealistic and misleading from a different perspective because it contains several dystopian tendencies in the areas of governance and environment. For decades, the authority and power of national governments and the UN has been eroded by multinational and financial corporations, helped by the dissolution of the former USSR and intensified by globalizing information and communication technology and media (cf. Section 2.2). The change since the global optimism in ‘Our Common Future’ (1987) by the UN WCED and ‘Our Global Neighbourhood’ (1995) by the Commission on Global Governance is clear from a recent (2017) statement within the US government: “The world is not a global community, but an arena in which nations, organizations and companies compete with each other in order to make progress.” The focus on competitive markets and libertarian–utilitarian values impedes investment in public infrastructure (hospitals, schools, transport), protection of the commons (forest, water, air) and social inclusiveness policies – important targets in the SDGs. It coincides with growing inequality within and between countries and it is, ethically, a move towards hero/survival morality in the public domain.Footnote xli Another dystopian trend in (Late) Modernity, largely countered with technological optimism, is the degradation of resources and the environment, in combination with a further growth in population and economic activity.

Progress in material life conditions, as promised in the SDGs, may for many turn out to be an illusion. If populist leaders encourage nationalism and ethnicity instead of international negotiation and cooperation, as the social dilemma character of these issues demands, perennial conflict and mass migration are among the foreseeable outcomes. The wealthy and privileged are served well by a libertarian–utilitarian ethic in the appropriation of land and resources. A new feudalism arises with substantial inequity not only in material possessions, but also in lifestyles and expectations, and there is also immanent conflict. Thus, the Modernity narrative is eroded, challenged and complemented from various sides. Are there counter-narratives from other worldviews?

5.2. Other worldviews: counter-narratives

The worldview space has been presented as a dynamic process (Section 3). When a particular worldview becomes (too) dominant, opposing forces will start to work and engage with different values and beliefs. This is the background for interesting counter-narratives. First, the many religious institutions and movements emphasize – sometimes quite strongly – different perspectives on ‘the good life’ (upper-left in Figure 3). Listen, for instance, to Pope Francis in the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si, who criticizes “the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose” and gives a reinterpreted Christian view of nature, in which “genuine care for our own lives and our relationships with nature is inseparable from fraternity, justice and faithfulness to others.” The leaders and practitioners of other organized religions and spiritual traditions offer critique and alternative ethical guidance too (e.g., Dalai Lama, Reference Lama1999/2014). Often, particularly in Eastern traditions, the emphasis is on personal spiritual experience and discipline (upper-right in Figure 3).Footnote xlii It corresponds with a different perspective on the human–environment relationship: “From a traditional Buddhist point of view … an explicit ecological ethics, based on imparting value to nature, is superfluous, because a behaviour that keeps nature intact is the spontaneous automatic outflow of the moral and spiritual self-perfection to be accomplished by every person individually” (Eckel & Schmithausen, quoted in Payne, Reference Payne2010). Of course, it should not be forgotten that religious institutions and individuals did and do associate themselves with worldly affairs in less lofty ways.

A related, more secular and activist critique stems from a large and diverse array of people who resist top-down, imposed uniformity and surveillance and work in their own ways on alternative, small-scale pathways with an emphasis on community, diversity and spirituality.Footnote xliii Respecting traditional knowledge and practices among indigenous people, developing new attitudes and relationships with animals and experimenting with altered states of consciousness all belong to this rich palette. There is already a wealth of initiatives, projects and communities from this corner of worldview space: “Not only is another world possible, it is already being born in small pockets the world over … their successes can be applied to existing social structures, from the local to the global scale, providing sustainable ways of living for generations to come” (www.ecovillagebook.org). The actors are often members of NGOs and CSOs that engage with many diverse issues. Naturally, the values and beliefs on the human–nature relationship, on justice and fairness and on technology differ – and sometimes widely – because they reflect the inherent particularity and contingency in the world and its perception.

Within a Modernity worldview, these movements are often dismissed as romantic and idealistic, populist and nationalist-ethnic or simply rebellious and radical (cf. Section 2.2). They resonate with the ethical positions in the mid- and upper-right parts of worldview space (Figure 3). Here, a person's reflections and actions with respect to the abstract ideals of human (and animal) rights, basic needs (food, health, education) and ecosystem integrity are necessarily contextual, bridging the gap between objective and subjective by defining objectivity as “neither a state of the world nor a state of the mind; it is the result of a well-maintained public life” (Latour, Reference Latour2017, p. 47) and connecting to virtue and dharma ethics (cf. Sections 4.4 and 4.5).

Thus, it is seen that the SDGs and their associated targets are not only interpreted differently, but also dismissed or rejected by significant fractions of population(s) because of conflicting interests, divergent values and beliefs, ignorance and distrust. The underlying counter-narratives reflect other values and preferences: cooperation over competition, harmony and justice over achievement and wealth, and so on. This is why I propose to enrich the one-sidedness of the SDGs and targets with values, beliefs, ethics and narratives from other worldviews, in order to engage people in their exploration and implementation efforts and to foster dialogue and decision-making at the appropriate levels. This is not easy. It requires openness and respect for other persons’ views, identification and recognition of conflicting values and interests and an expansion of people's time–space horizon. We also need real-world experiments in ecovillages, urban restoration projects, transition towns and the like. In such a broadened perspective, people would decide in their own community and region based on their local traditions and circumstances, within the logic of subsidiarity and negotiable external constraints.

Moreover, there is a trade-off. Universal standards and goals and top-down control are ingrained in the Modernity worldview; relaxing them goes against the quest for universals in earth system governance and against an ethic for the Anthropocene (Biermann, Reference Biermann2014; Jamieson, Reference Jamieson2014).Footnote xliv It also runs counter to a further increase in the scale and globalization of markets in the name of efficiency, innovation and economic growth (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2011; van Norren, Reference van Norren2017). It is antithetical to intensified state and/or corporate surveillance, but also to enlightened human rights universalism. It is a change towards the particularities and contingencies of the right-hand side of worldview space (Figure 3) – which is the lived reality of individual persons and communities. When the SDG targets and policies are considered in such a more contextualized setting, it will reveal new problem perceptions and solutions, but it will also inevitably cause conflicts of identity and increased uncertainty in the planning and realization of targets (de Vries, Reference de Vries, Costanza, Graumlich and Steffen2006; Huntington, Reference Huntington1993). It is glocalism and rurbanism, with more emphasis on socio-political and cultural diversity and more local support and creativity.

5.3. Operationalization: the middle road

The SDGs can only be successfully realized by acknowledging the diversity in values and beliefs and, from there, appreciating why they are perceived as good or bad, meaningful or hypocrite, relevant or abstract, consistent or mutually exclusive. The core objectives of human dignity and sustainability are then to be realized in a synthesis across the various worldviews, meeting in the middle where there is balance and harmony. A focus on the middle road is a well-known precept in ancient religions and philosophies and is perhaps best represented in the development as freedom and capability approach and in Aristotelian and religious conceptions of virtue and ‘the good life’.Footnote xlv It is about finding a balance between one's own responsibility and community/state care, new technological options and traditional knowledge, old customs and new habits, instrumental use and intrinsic value. It is here that there is the call for responsible behaviour as consumer and citizen, for personal maturing and empathy with suffering sentient beings, for decent and effective government and business and for mutual responsibility towards nature to come together.

Within the worldview framework, this can be given the interpretation that the individual person matures in travelling throughout worldview space towards the middle. Extreme manifestations of a worldview, in a process of radicalization and polarization around identity, tend to shut off and disrespect other values and beliefs and encourage moral complacency (van Egmond, Reference van Egmond2014; van Egmond & de Vries, Reference van Egmond and de Vries2011). Examples are religious fundamentalism and sectarianism (upper part of Figure 3), state terrorism and fascism (mid-left part of Figure 3), dictatorship and forms of corporatism (lower-left part of Figure 3) and extreme consumerism and materialism (lower-right part of Figure 3). In is in that sense that they are evil.Footnote xlvi What constitutes ‘the good life’ may also change as the point of reference in the middle ground evolves – it is contextual and never unambiguously clear in its actual manifestations.Footnote xlvii

What does applying the worldview approach to the SDGs mean in practice? There surely is not a single answer or recipe, but I venture the following elements:

• It supports designing and experimenting with the middle ground through dialogue and the search for robust solutions.

• It facilitates the search for new institutions for public good and common pool (resource) management and stakeholder involvement.

• It helps to identify and encourage coalitions and alliances based on shared interests, values and beliefs.

As to the first two points, new insights on the role of trust and cooperation as compared to (market) anonymity, competition and efficiency, notably in managing the (global) commons, are highly relevant (Bowles, Reference Bowles2016; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990, Reference Ostrom2000, Reference Ostrom2009; Rothstein, Reference Rothstein2015). Regarding the last point, international treaties are prime examples, with their successes and failures. Small-scale examples are the associations between science and innovating business in small-scale projects such as water purification, efficient stoves and solar lighting, and business–consumer group alliances around appliance standards, green labels and certificates and fair trade. Cooperatives and buy-local activities also belong in this category. Another civic society association and dialogue is between religious leaders and institutions on the one hand and citizens with humanitarian concerns on the other. Of course, none of these endeavours is without struggle and conflict. Vested economic systems, interests and cultural identities will resist the middle ground in a process of media-enhanced polarization and radicalization. Some controversies will remain unresolved. To illustrate the middle road, I end with a discussion of a few specific SDG targets that are crucial for sustainability and development: health, education and protecting the natural commons.

5.4. A worldview-based assessment of SDGs: examples

SDG Target 3.7: Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services

This target reflects an ‘enlightened’ perspective on the health of women and children, in connection with other SDGs (such as #2 and #5). For the women involved, there is great variety in their situation and motivation: sex and birth have health (disease, survival), emotional and moral (joy, pride, respectability), economic (affordability, security) and social and religious (freedom of choice, tradition) aspects. Governments tend to see this SDG in the context of concerns about the growth and ageing of populations and can respond with top-down programmes for contraceptives, abortion or child allowances in a social-utilitarian mode (efficiency and cost). In response, businesses will see market opportunities and emphasize innovation. Priests may call for moral restraint in the name of human dignity and/or as part of obedience to the scriptures and respect for religious institutions. Fieldworkers make a case for community healthcare with appreciation of local values and traditions and empowerment of local people.

Ethical issues abound. Is having children a universal right? Is forced sterilization ethically an option? How are we to handle a wish for abortion? How much medication should there be for children who grow up experiencing hunger and violence? An enlightenment ethic will emphasize the universality of the services offered, including the capability to understand and access them – which implies an important role for an effective government. Framed in a liberal ethic, there is a trade-off between individual freedom and (inter)national control strategies. In a utilitarian ethic, actions are legitimated in cost–benefit analyses of existing and new practices – which means assumptions on the ‘price’ of present and future human and other life. The development as freedom approach and virtue ethics will emphasize the personal situation and the embedding in community practice. This usually implies a conflict with higher-level planning purposes or intrusive forces, which may in itself be the major contribution of those who convey this ethic.

SDG Target 4.1: Ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education

This target reflects the ‘enlightened’ belief that education is a human right and promotes personal quality of life and happiness, in relation to other SDGs (such as #5, #8–12 and #16). People will, in the first instance, judge the organization and content of education as an extension of the local family and community – although communication technology is rapidly broadening this horizon. Teachers, schoolchildren and students come from diverse backgrounds and with various motivations: a source of income and knowledge or the prospect of emancipation, a job and/or no longer working at home, to mention a few. As with healthcare, implementing this target will occur in hugely different circumstances regarding government presence and effectiveness, available resources (teachers, schools), secular and religious background and local biogeography. Governments consider it a necessity for economic growth and employment (#8, #9), as do most entrepreneurs. Religious institutions stimulate study of the scriptures and the growth of a community and spiritual teachers facilitate studying the local and the inner world.

Seen from an enlightenment ethics perspective, having access to education is yet another human right. It should be available to everyone, and those with talents should contribute to the education of the less talented in accordance with Rawls’ difference principle. Sen's development as freedom approach complements this largely meritocratic ethic with embeddedness in heterogeneous social rules and relations. Both imply an important role for the (local) government. In a libertarian ethic, education is a private good, to be supplied on the market in response to demand. The state or community has a limited role or no role to play, and so there is no need for this SDG from this perspective. This position is defended by the wealthy (middle) classes when the demand for education in growing populations with many young people overwhelms the supply capacity of (local) government. It is at odds with other SDGs. From a (social) utilitarian perspective, a slightly different position is taken: education is a marketable good that should be available to those who desire it and can afford it, but, being a public good, the cost for individuals has to be weighed against the benefits to society. Hence, the state should offer educational services to the extent that they increase societal utility.

Sometimes diametrically opposed are a large variety of views on education that are rooted in humanistic psychology and spirituality. For them, personal growth, autonomy and the acquisition of aesthetic and ethical capabilities (‘wisdom’) besides practical skills and knowledge are essential. Again, the middle ground is covered by virtue ethics and the capability approach: teaching children is a practice with internal goods – such as the joy of a teacher and pupil in learning – and what is taught is embedded in community life. The school is its institutional form and should be protected against invasion by the search for external goods.

SDG Targets 14.2 and 15.2: Sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems to avoid significant adverse impacts

One of the great challenges for humanity in the Anthropocene is to develop a decent quality of life for all while maintaining the diversity and integrity of water and terrestrial ecosystems (#14, #15). Provision of food (#2), water (#6) and energy services (#7) causes increasing stress on land and water resources from overexploitation, pollution and climate change, and universal access to these services is linked to complex issues such as those of access to and ownership of resources and land (#1, #2, #6 and #7). At the same time, (unmanaged) nature is increasingly valued for recreation, and there is greater willingness to do justice by the rights of the inhabitants of forests and coastal areas – who depend on them for their livelihoods – and to take steps against further loss of biodiversity. There are large differences in people's values, beliefs and interests regarding (the use of) nature, reflecting local biogeography, cultural traditions and techno-economic conditions. The delicate balance between human needs and the protection of marine and coastal ecosystems is a matter of local–regional activities and policies, although (growth in) global trade makes them more connected and interdependent.

There is a variety of ethical positions and guidelines in the concretization of these targets. Governments focus on development needs, knowing that the majority of voters have short-term priorities, notably as consumers and jobseekers. Decisions on de/reforestation, wildlife preserves and biodiversity, water pollution, waste management and other threats to ecosystem integrity are then taken in a ‘least cost’ fashion. Nature's ecosystem services are to be monetized, an instrumentalist approach that is also applied to species survival, (agri)cultural diversity and traditional practices. The representatives of science and business usually join with technological solutions within the frame of economic prosperity for all. Hydropower dams and the use of pesticides are among the well-known battlegrounds. More culturally and religiously inspired people point to the necessity to consider land and water again as sacred and to use them with respect and restraint. They bring personal value, conscience and lifestyle issues to the table, as in the advocacy for ‘meat-free days’.Footnote xlviii

An interesting ethical case is the use of genetically modified organisms. This use is advocated by big business as a solution to ‘the world food problem’ and is related to several SDGs.Footnote xlix Besides safety issues from an ecosystem and human health perspective, this raises the issue of intellectual property rights. Within a social-utilitarian ethic as applied in modern welfare states, genetic resources are a common good and should be used to the maximum benefit of society, with an appropriate reward for the ‘owners’. The state intermediates in settling entitlements and risks of use. Rawls and Sen go one step further: those who benefit from the use of genetic resources (on the market) because they were the first to discover or appropriate them should reward the community. This should be regulated in the ownership rights and patentability of genetic resources in state-organized negotiations. This is fiercely resisted by libertarians, who consider knowledge from scientific research (on genetic resources) as intellectual property of which the ownership is contractually arranged.Footnote l A more spiritual stance on the matter is that nature simply cannot and should not be commodified or privatized. In all of these situations, the only way out is dialogue, resembling perhaps the meetings of the elders in traditional villages that proceed until unanimous agreement is reached.Footnote li

6. Concluding remarks

The worldview behind the SDGs is characterized by Modernity. This no longer offers satisfactory principles and rules for the relationships of human beings with each other and with the natural world in the Anthropocene. The SDGs and their associated targets and indicators represent ideals and ambitions for the world and point to a path towards a collectively desirable state of the world. Ethics is about the choice between alternatives for future action, and as such the SDGs are ethical. In this paper, I offer the worldview framework as a heuristic tool to explore various ethical positions regarding the content and attainment of the SDGs. This permits a systematic identification of different worldviews and associated ethical positions along the dimensions of particular–universal and material–spiritual. I propose that the realization of truly sustainable development in the sense of (human) dignity and justice, ‘the good life’ and staying within ‘planetary boundaries’ is found in the middle for both individual and society. It is a rebalancing act in which the subjective and the immaterial are regaining legitimacy and the relation between individual and collective is reorientating itself. An explicit and systematic assessment of stakeholders and associated worldviews and narratives is a helpful tool in this venture, as are civic society experiments with novel concepts, rules and institutions and setting up dialogue, coalitions and alliances.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful for comments on a draft of this manuscript by Paul van Tongeren and Jan Boersema and for discussions with Klaas van Egmond. I also thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research and article complied with Global Sustainability's publishing ethics guidelines.