This chapter starts Part III of the book, which is where we put the SCF to work, so to speak. Using its three perspectives and the models described in Part II, we discuss different ways in which both career and organization studies can benefit from the SCF, by facilitating conversation across disciplinary boundaries. When we speak of career studies, we mean all scientific efforts across the broad range of disciplines that we describe in Chapter 1 as falling within the proto-field of career studies (Figure 1.1). This comprises fields dealing with career (or an obvious synonym) as their primary object of study, even though scholars working within these fields may not necessarily think of themselves as working on a common project with scholars in other fields within the proto-field (or even agree that this proto-field exists). Examples of these fields include life-course research, migration research, vocational psychology, and studies on organization and management careers (OMC). As we note in Chapter 1, we devote most attention here to OMC studies.

In this chapter, we focus on the potential of the SCF for supporting conversations across different scientific boundaries within the proto-field of career studies. The SCF, in particular its three perspectives, constitutes a means for creating common ground in such conversations. By relating different types of empirical and theoretical work to the ontic, spatial, and temporal perspectives, we suggest, the SCF highlights typical characteristics of different kinds of career research and shows commonalities and differences between various streams of work.

We begin the chapter by outlining the importance of conversations between partially disconnected discourses and actors. We then demonstrate how the SCF supports conversations across different fields of career studies. Using ideal types in the Weberian sense, we show how different studies address the basic issues linked to the three SCF perspectives to differing degrees and how that provides possible starting points for conversations about similarities and differences between them. The final step in this chapter illustrates the potential of the SCF for facilitating a different type of conversation that touches the identity of the field of OMC studies. It traces the development of the OMC field – to be sure, one of many possible accounts – from its origins in sociological, vocational, and developmental literatures, which stretch back to the nineteenth century in some cases and to the classical period in others (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Gunz, Hall, Gunz and Peiperl2007), and focuses on developments since the 1950s. So using the SCF we reconstruct the history of the OMC field.

The Importance of Conversation

As we note in earlier chapters, prominent voices over a number of years have raised the issue of the lack of contact between different fields of career studies (e.g. Collin and Patton, Reference Collin and Patton2009; Arthur, Reference Arthur2008; Peiperl and Gunz, Reference Peiperl, Gunz, Gunz and Peiperl2007; Collin and Young, Reference Collin, Young, Collin and Young2000). Again as we note in Chapter 1, the field of OMC studies can be described as a fragmented adhocracy (Whitley, Reference Whitley1984), being highly differentiated internally with a large number of discourses, a complex set of conversations around a common theme that are, at best, mutually politely acknowledged and, at worst, only marginally aware of each other. Two questions follow from this: Does any of this matter, and if yes, what is to be done? We address these issues next.

Fragmentation and Its Consequences

Fragmentation is by no means unique to the field of OMC studies in particular or the proto-field of career studies in general. For decades, influential figures in the field of management studies have been regularly pointing out the state of disarray of the field. As early as 1962, Koontz, for example, writes that

the varied approaches to management theory have led to a kind of confused and destructive jungle warfare. Particularly in academic writings, the primary interests of many would-be cult leaders seem to be to carve out a distinct (and hence, original) approach to management. To defend this originality, and thereby gain a place in posterity (or at least to gain a publication which will justify academic status or promotion), these writers seem to have become overly concerned with downrating, and sometimes misrepresenting, what anyone else has said, or thought, or done.

By 1984 not much has changed:

We have recently argued … that the organizational sciences are severely fragmented, and that this fragmentation presents a serious obstacle to scientific growth of the field. For example, topics in introductory textbooks are so loosely interconnected that virtually any of them can be arbitrarily dropped without damaging the flow of the course … This is not the fault of the textbook writers but of the field itself: most research issues and themes develop, flourish, or die in essential isolation from one another. Each may speak to the very general concern of “behavior in organization,” but few have much to say to one another.

Pfeffer returns to the theme in Reference Pfeffer1993 in a paper setting out the benefits of paradigm development within a field, which he enumerates in considerable depth before turning to organization studies:

The study of organizations has numerous subspecialties, and these certainly vary in terms of the level of paradigm development. Nevertheless, it appears that, in general, the field of organizational studies is characterized by a fairly low level of paradigm development, particularly as compared to some adjacent social sciences such as psychology, economics, and even political science.

It does not stop there. Fast-forward twenty years to 2013, to find Shepherd and Challenger (Reference Shepherd and Challenger2013) writing about what they describe as the “paradigm wars” that still, they argue, sweep the field of management research. While observing that

[a]round the millennium, calls increased for the dissolution of the paradigm wars [that] … sought to bring discursive closure to two decades of debate surrounding the notion of paradigm(s) and incommensurability … [and] the paradigm wars have abated somewhat over the past 10 years, the concept of paradigm(s) remains in widespread use across a range of disciplines.

A tacit assumption of many of these laments is that, ultimately, fragmentation is detrimental to the development of the field. Rather, it should be organized around a common paradigm, albeit acknowledging that the term is used in many different ways, at least twenty-one of which come from Kuhn (Reference Kuhn1970; critically and with more emphasis on gradual change: Lakatos, Reference Lakatos1984), the spiritus rector of the idea of science as developing along different paradigms and their revolutionary change, himself (Masterman, Reference Masterman, Lakatos and Musgrave1970).

However, there is a contrary view to that notion. Perhaps Van Maanen’s response to Pfeffer’s plea for more paradigmatic consensus within organization and management studies puts it most succinctly:

In simple moral terms, the idea that we should somehow look toward paradigmatic consensus for our salvation is wrong. Even if such a world were possible (which it is not, see below), it would be a most uncomfortable place to reside. It would be a world with little emancipatory possibilities, a world with even tighter restrictions on who can be published, promoted, fired, celebrated, reviled than we have now. Sturm und Drang und Tenure.Footnote 1 The image of a large research community characterized by the kinds of traits Jeff [Pfeffer] associates with paradigm consensus is that of a clean California research park where nothing is out of place and all is governed by a corporate logic focused on productivity, competitive advantage and the good old bottom line. This is not scholarship. On normative grounds alone, paradigm consensus can be rejected.

That said, favoring a plurality of viewpoints does not preclude an emphasis on the importance of mutual exchange and conversations across boundaries. Van Maanen recognizes that “it is pernicious and beside the point to suggest we stick to our own claustrophobic ways with each of us camped by our own totem pole. We need ways of talking across research programs and theoretical commitments” (Reference Van Maanen1995: 691). This theme is echoed by Czarniawska:

After all, there are much more serious dangers in life than dissonance in organization theory. Crossing the street every day is one such instance. We may as well abandon this self-centered rhetoric and concentrate on a more practical issue: it seems that we would like to be able to talk to one another, and from time to time have an illusion of understanding what the Other is saying … What we need, I think, is not commensurability but plenty of translation. Not “translatability” as a property of a text, but “translation” as an action, in a meaning coined by Michel Serre and circulated by Michel Callon and Bruno Latour. Such translation has a meaning far beyond the linguistic one, as it concerns anything taken from one place and time, and put into another – an act which changes both the translator, and what is translated. There is no question of ‘faithfulness’: by definition, what has been translated is never the same again. Plenty of translation makes the field vibrant and lively, it energizes it, rather than putting it to a (commensurate) sleep.”

To sum up, in this chapter we are in territory that is familiar to anyone who has been following the progress of the field of management studies (and others; for a thoughtful analysis of similar issues in the field of management information systems, see Banville and Landry, Reference Banville and Landry1989). One set of voices points to the disorganization of the field and the harm that this does to scientific progress; another set argues that, even if it could be done, this would result in the field being put in a straitjacket with catastrophic loss of creativity. A third set of voices argues for an intermediate position between what Knudsen (Reference Knudsen2003) calls the “specialization” trap, in which all that happens is that researchers work unimaginatively on safe, established paradigms, and the “fragmentation” trap, in which new theories proliferate faster than anyone can evaluate or compare them. However, regardless of the position one takes in terms of the need or danger of a common paradigm, it seems to be a common denominator that conversation is needed between the fragmented parts of the field and beyond (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska1998). But what exactly is conversation, and how can it help?

Conversation as a Way Forward

We subscribe to the notion that scientific progress requires the free exchange of ideas, talking to each other across disciplinary, theoretical, methodical, methodological, epistemological, geographical, and ideological boundaries. Fragmentation is an obstacle to this, regardless of whether the ultimate goal is a unified paradigm or a field where a thousand flowers bloom. But is conversation, put forward by major voices (e.g. Arthur, Reference Arthur2008) as an important way of communicating across boundaries, a suitable candidate for this? We now address this question.

Conversation is a specific kind of communication. Three of its major characteristics important here (for a more general discussion on features of conversations, see, e.g. Thornbury and Slade, Reference Thornbury and Slade2006; Warren, Reference Warren2006) are (1) the need for establishing common ground, (2) the absence of predefined goals other than reaching understanding and strengthening social ties, and (3) the equal status of participants.

1 Need for Establishing Common Ground

There are some basic requirements for achieving common ground when conversations are to unfold, none of them necessarily easy to achieve, such as a common language, the availability of time resources, or the willingness and capability of individuals to participate in a conversation (sometimes called an art in itself; see Miller, Reference Miller2008). Beyond that, a crucial and arguably basic requirement for having a conversation about an object is the existence of “a temporary agreement about how they [the speakers] and their addressees are to conceptualize that object” (Brennan and Clark, Reference Brennan and Clark1996: 1491). Called a conceptual pact, this helps the partners in a conversation to reach a basic understanding about what they are talking about. In addition, situation models, i.e. “multi-dimensional representations containing information about space, time, causality, intentionality and currently relevant individuals” (Garrod and Pickering, Reference Garrod and Pickering2004: 8; see also Zwaan and Radvansky, Reference Zwaan and Radvansky1998), help to structure the situation and advise participants in the conversation about relevant dimensions and elements. In so doing, the participants potentially aim for different forms of coordination, in particular semantic coordination in terms of the mental models employed by the participants in the conversation; lexical coordination with regard to the expressions they use to refer to entities in their models; and syntactic coordination, which refers to the grammatical form during a conversation. Note that by no means do the coordination efforts have to be intentional. “It is important to stress that such convergence in behavior may be implicit; it need not involve any conscious or deliberate intent on the part of participants” (Branigan, Pickering, and Cleland, Reference Branigan, Pickering and Cleland2000: B14). Yet, as Conversation Theory puts it, to have an “agreement of an understanding” (Pask, Reference Pask1984: 13) is crucial in order to understand each other.

2 Absence of Predefined Goals Other Than Reaching Understanding and Strengthening Social Ties

Conversations have little, if any, transactional function for reaching predefined goals but are open for different types of outcome, which often emerge in the course of the conversation. Two implicitly important results, though, are understanding and strengthening social ties. Regarding the former, conversation builds strongly on communicative action, with reaching understanding located at its center. As Habermas (Reference Habermas1981) puts it: “Verständigung wohnt als Telos der menschlichen Sprache inne [Reaching understanding is the inherent telos (aim) of human speech]” (387; for the English version: Habermas, Reference Habermas1984: 287). This is a substantial difference from, for example, strategic action where achieving individual goals that actors bring to the situation is most important. Of course, this does not preclude the possibility that conversations between career scholars from different areas of the field can later turn into a discourse (Howarth, Reference Howarth2010), i.e. “processes of argumentation and dialogue in which the claims implicit in the speech act are tested for their rational justifiability as true, correct or authentic” (Bohman and Rehg, Reference Bohman, Rehg and Zalta2014), where “right/wrong” rather than “understand/not understand” is the guiding difference. Yet in essence “[c]onversations have no pre-defined goal(s) and the negotiation of topical coherence is shared between participants” (Warren, Reference Warren2006: 13). The interpersonal function of conversation crucially involves establishing and maintaining social ties rather than achieving individual goals for one’s own benefit (Thornbury and Slade, Reference Thornbury and Slade2006). Having a conversation with others mutually acknowledges that one regards the other as a person worthy of devoting time and energy to and, for better or worse, that the conversation can lead to new insights about the conversation partner. This strengthens the relationship as it provides a basis for future exchange, even in the case that at an emotional level bonding has not been strengthened.

3 Equal Status of Participants

A symmetrical relationship between participating interlocutors, i.e. actors taking part in the exchange, is a further constitutive characteristic of a conversation (Thornbury and Slade, Reference Thornbury and Slade2006). In contrast to other communicative situations such as bureaucratic encounters, nurse–patient consultations, or court hearings where hierarchical, asymmetrical relationships are an integral part of the situation, conversations have little or no structurally prescribed asymmetries. Of course, there will be power differentials emerging from inevitable differences in knowledge about a subject, conversational skills, interpersonal attraction, or physical appearance. However, these differentials are more ad hoc and fluid and not an essential characteristic. Basically, the status of the participants in a conversation is perceived to be equal, and they share responsibility for successful outcomes and progress (Warren, Reference Warren2006).

These three important characteristics of conversations – conceptual pacts, strengthening social ties, and a symmetrical relationship – make this form of exchange well suited for communicating in a fragmented field. Putting interlocutors on an equal footing, detecting conceptual pacts, and jointly defining situation models are all about discovering common ground. This view of conversation is of an exchange among equals and not a parochial endeavor in which the major agenda is discrediting deviant ways and conquering theoretical and empirical territory. In addition, the emphasis on building and sustaining social ties rather than achieving an interest-related outcome makes a fruitful exchange of ideas more likely.

Because conversations typically take place in complex situations and because the situations in which conversations take place across scientific boundaries are especially complex, it is helpful for a conversation to happen in such a situation to have some kind of simplifications that are accepted by both interlocutors. Ideal types are widely used to provide this kind of simplification, and we turn to them next.

Ideal Types Facilitating Conversation

One of the benefits of examining the field of career studies through the SCF is that, as we show later in this chapter, it allows us to construct a number of ideal types of single career studies. These ideal types help career researchers see where the foci of studies are by simplifying their complexity. Ideal types experienced their breakthrough in the social sciences through the work of German sociologist Max Weber (Reference Weber1968 [Original 1922]: 190 ff.). The term is used in a variety of senses, but the one we use here is an idealized representation of a concept, of a kind that does not exist in the real world but that helps us make sense of that real world. It can be used to denote an abstraction of something that is empirically observable. So, for example, Barley (Reference Barley1996) describes how new models of work and of the relations of production allow us to construct new ideal-typical occupations:

An ideal-typical occupation is an abstraction that captures key attributes of a cluster of occupations. As Weber noted, ideal types are useful not because they are descriptively accurate – actual instances rarely evince all of the attributes of an ideal type – but because they serve as models that assist in thinking about social phenomena.

More commonly, however, ideal types are used in connection with taxonomies of social constructs. Van de Ven, Ganco, and Hinings (Reference Van de Ven, Ganco and Hinings2013) list a number of ideal types from the literature, including March and Simon’s (Reference March and Simon1958) and Thompson’s (Reference Thompson1967) types of programs for organizing, Burns and Stalker’s (Reference Burns and Stalker1961) distinction between organic and mechanistic structures, Mintzberg’s (Reference Mintzberg1979) five organizational designs, and Miles and Snow’s (Reference Miles and Snow1978) types of organizational design (prospector, analyzer, defender, reactor). Nelson and Nielsen (Reference Nelson and Nielsen2000) describe three ideal types of inside counsel (lawyers employed by commercial operations, the types being cops, counsels, entrepreneurs); Swanson (Reference Swanson1999) distinguishes between two ideal types of corporate social interactions, value neglect and value attunement. Arguably, the rational decision-making model is another ideal type, one that has provided a useful straw person for decision theorists for many years.

Ideal types have been widely used in the career literature, too, to denote various kinds of career taxonomies. For example, Nicholson (Reference Nicholson1996) describes traditional and new paradigms of career as being ideal types because they have a

mythical and unreal quality … The traditional model was only rarely found in a fully articulated form. AT&T’s elaborate career system is a much quoted example. Yet even in such classic cases there were always people who would find the model did not apply–for example, specialist professionals, plateaued managers, and many women.

Similarly, King, Burke and Pemberton (Reference King, Burke and Pemberton2005: 982) talk about traditional and boundaryless careers as ideal types in the sense that “neither adequately captures the complex interaction between individual agency and structural constraints that circumscribes a person’s career”; Mayrhofer (Reference Mayrhofer2001) describes four ideal type organizational international career logics; Inkson et al. (Reference Inkson, Gunz, Ganesh and Roper2012) also consider describing the boundaryless career as an ideal type but dismiss the idea because the construct’s boundaries are too fuzzy.

It is important for present purposes to emphasize that the “ideal” in the term “ideal type” does not mean to imply desirability, as Weber himself wryly remarked in a letter to a colleague:

That you have linguistic doubts about the “ideal type” distresses me in my paternal vanity. But my view is that, if we speak of Bismarck not as the “ideal” among Germans but as the “ideal type” of [being] German, we do not mean anything “exemplary” as such but are saying that he possessed certain German, essentially indifferent and perhaps even unpleasant qualities …

So the ideal types we list here do not describe specific forms of career scholarship as ideals against which all real career scholarship will emerge wanting and inadequate. Because the SCF talks in broad terms about condition, social space, and time, it is easy to draw the erroneous inference that an ideal type career research project would examine all aspects of the condition of the career actor, within a global and multifaceted social space, against a background of historic time approached in any way that time can be conceived of in a social setting. It would also be easy to draw the, again erroneous, inference that any career research that fails to address each of these in its fullness is inadequate. Of course, for practical reasons no single study can do that. Every researcher must make choices about what to focus on and what to leave out; otherwise nobody would ever get anything done. The ideal types serve here a different purpose, namely to help identify distinctions between different types of career scholarship in order, as we note previously, to facilitate conversation within and between them.

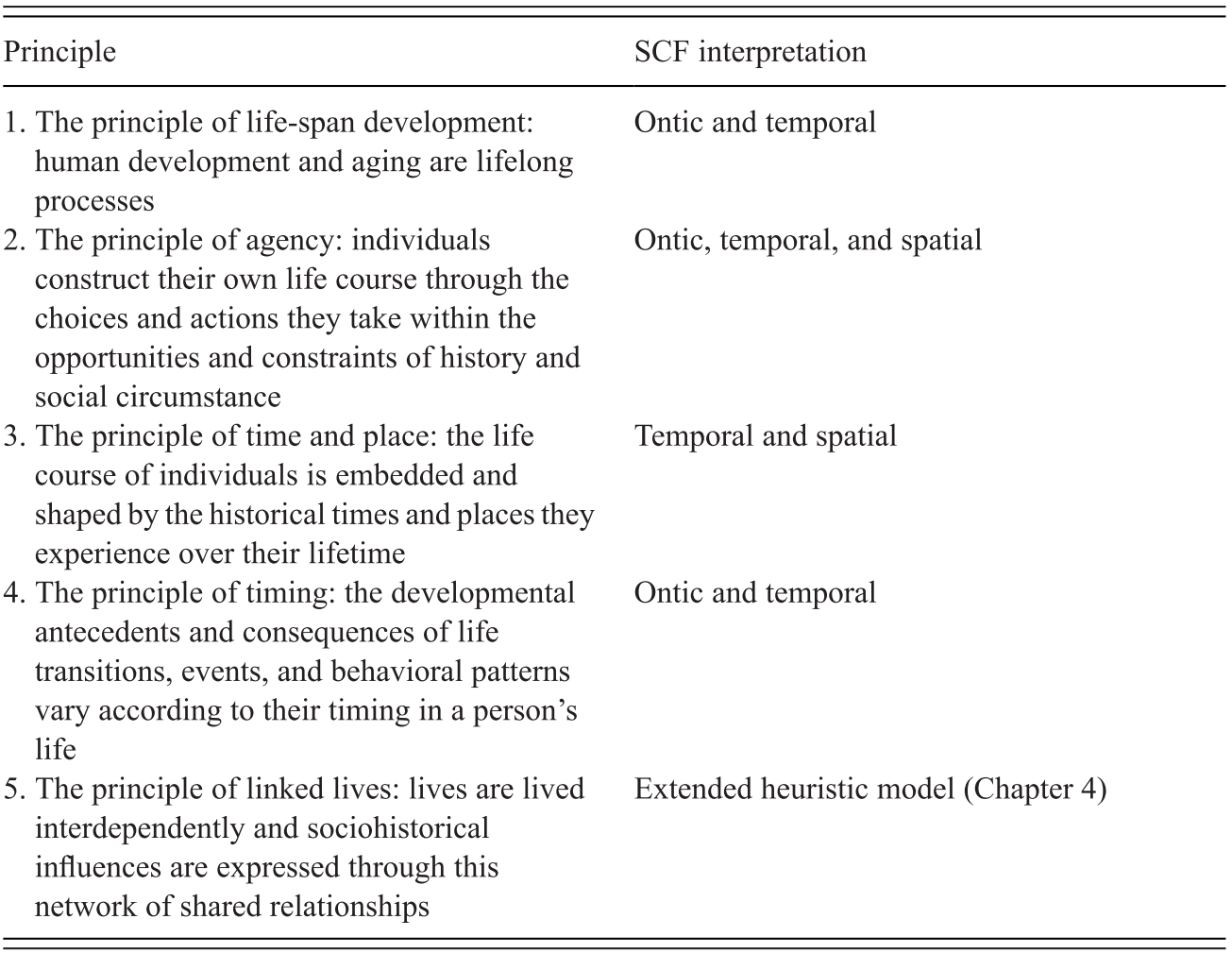

The ideal types we derive from the SCF emerge from the observation that although, as we argue, career scholarship involves the application of all three perspectives, not all such scholarship necessarily places equal emphasis on all three. Depending on the focus of any given topic area, studies within it are likely to place greater emphasis on only one or two of the perspectives. That is not to say that the other perspectives are ignored, but simply that they play a more background role. In rather the same way that Mintzberg (Reference Mintzberg1979) constructs a set of ideal types of organization based on the varying degree of emphasis the different types place on elements of his basic model of organization, we distinguish between three ideal typical forms of career research that we call focused, bivalent, and balanced. While in the following we will illustrate these ideal types with examples of single studies, they also can apply to larger discourses such as fields within career studies.

Focused

Focused career research concentrates primarily on one perspective of the SCF while placing lesser emphasis on the other two dimensions. Two examples at the level of individual studies may suffice. Career studies focusing on the link between personality and different types of career success are examples of focused career research emphasizing the ontic aspect of careers. While they vary in the importance they give to factors located in the social space and to the dimension of time in which careers are embedded, their primary interest lies in personality and/or factors closely linked with the person.

A well-cited piece by Seibert and Kraimer (Reference Seibert and Kraimer2001) examines the relationship between the Big Five personality dimensions and extrinsic as well as intrinsic career success, measured as promotion and salary, and career satisfaction, respectively. Their focus clearly is on the effects of the Big Five on career success. However, in controlling for what they call “other career related variables,” they acknowledge the importance of the other perspectives for their research interest. Indeed, they find, among other things, that the negative effect of agreeableness on salary was moderated by occupation, in SCF terms an element of the social space.

Arguably, the analysis by Hesketh (Reference Hesketh2000) looking at time-discounting principles in career-related choices and focusing on the temporal perspective also reflects this ideal type of focused career research. It speaks to the discussion about job choices and their anticipated future consequences, how individuals discount the value of a delayed outcome, and the role that time and probability information plays in career-related decisions. The two experimental studies in the paper look at choices related to student union fees and scholarships and at the differences in time discounting between career counseling novices and experts when giving advice about job options. Clearly, the interest is the temporal dimension, using the concrete issues – partly ontic, partly spatial – only as a vehicle.

Bivalent

Bivalent career research gives roughly equal weight to two perspectives and lesser emphasis to the third. A good example of putting a dual emphasis on the spatial and temporal aspects can be found in studies of career timetables (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence1984), examining the rate (temporal) at which people move through hierarchical levels within organizations or professions (spatial). This points to various forms of intra-organizational mobility analysis focusing on structural characteristics of the organization and career trajectories, a classical topic of career research.

A highly influential contribution by White (Reference White1970) looks at promotions from within and ponders the consequences of an internal promotion. He argues that the subsequent set of transitions is not a set of vacancies, but, in effect, is one single vacancy, triggered by the original job move, propagating through the organization. Developing mathematical models to analyze mobility within organizations and to measure vacancy chains, understood as chains of contingent events, he empirically demonstrates the relevance of his considerations by using data from three churches as organizational settings.

Focusing on the temporal and ontic aspect, a classic study by Staw et al. (Reference Staw, Bell and Clausen1986) argues for a more dispositional approach, explicitly countering calls for greater situationalism in organizational research. The study uses three waves of a longitudinal sample (Guidance Study, Berkeley Growth Study, Oakland Growth Study) coming from the Intergenerational Studies effort following individuals over a span of fifty years with five time periods under scrutiny (early adolescence, twelve to fourteen years; late adolescence, fifteen to eighteen years; and three adult periods more or less evenly distributed between thirty and fifty years of age). The study shows that dispositional measures predicted job attitudes over a span of fifty years and is an excellent example of a temporal/ontic study.

Balanced

Balanced career research gives roughly equal weight to all three perspectives of the SCF. While there might be – and often is – a primary focus, the other perspectives are prominently present and do play a major role in the design of studies and in explaining the findings. Again, two illustrations may suffice.

The widely cited study by Rosenbaum (Reference Rosenbaum1979b) analyzes intra-organizational mobility patterns in a large corporation. Covering a thirteen-year time span, this study builds two conflicting conceptual viewpoints: a basically ahistorical path independence model with contest and sponsored mobility and a tournament model that takes into account the historical, i.e. developments over time where careers are seen as a sequence of competition, with each competition having consequences for the next round, usually putting the winners and losers on different tracks from then on. From a spatial perspective, the organization and the various tournament rules provide the social context; the temporal perspective emphasizes the historical, path dependent quality – or the lack of it – of career trajectories; the ontic perspective emphasizes status, the prestige assigned to people based on their position and operationalized as level category that shows the linkages between the spatial and the ontic perspective.

Going beyond organization, Higgins (Reference Higgins2005) looks at the effects that career imprints have on the careers of these individuals. Imprints are the cumulative outcome of strategy, structure, and culture of employers for their executives’ connections, capabilities, cognition, and confidence. These career imprints, an ontic element, travel with the individuals across different contexts such as other firms or industries (spatial) and not only affect the career trajectories of the individuals over time (temporal) but can also have effects on other organizations or even whole industries, e.g. by transferring certain views or practices from one context to another.

Graphically, one can depict these ideal types as follows. The inner circle indicates that in all career studies, the three perspectives are present at least as a nucleus. The outer circle indicates where the actual emphasis lies (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Ideal types of career research

In principle, we could have specified seven rather than three ideal types: three focused ideal types, one for each perspective; three bivalent, one for each possible pairing of perspectives; and one balanced. However, loosely applying one version of Ockham’s razor – enough but not too much or, more precisely, numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate (plurality is never to be posited without necessity; Ockam, Reference Ockam1962: Book 1, page 391, column A, line 42 [Original 1495: Book 1, Dist. 27, Qu. 2, K]) – leads us to the three basic ideal types that serve best for our purpose, facilitating conversation in a fragmented field.

Up to now in this chapter we have identified the need for exchange across various boundaries of fragmented fields such as career studies. We have proposed that conversation with some of its major requirements and characteristics – establishing common ground, emphasis on mutual understanding and strengthening social ties rather than reaching predefined goals, and equal status of participants – is a suitable candidate for such an exchange and have outlined three ideal types of career research following from the SCF. We now show how the SCF supports different kinds of conversations. We start with conversations between interlocutors pursuing different research interests, using examples from the OMC field.

Conversations between Career Fields

Conversation between fragmented areas boxed in by specific boundaries is facilitated by a framework that allows researchers from different traditions and fields to talk to each other and frame their ideas in ways that make it easier for others to understand (Newman, Reference Newman2006). The SCF offers such a common language and framework that can serve as a crystallizing point for shared conceptual pacts and situation models and the starting point for an exchange on an equal footing. As such, it rattles the cage of fragmentation. The SCF is specific enough to allow researchers from different fields with different interests and approaches to find common ground. At the same time, it is generic enough that it does minimal preformation in terms of theoretical perspective and epistemological, methodological, and methodical assumptions, and it emphasizes the symmetrical relationships between different members in the field.

The SCF acknowledges that insight into careers, in the broadest sense in which we use the term, is distributed between many pockets of research across a large number of disciplines, fields, and discourses as well as the regulative, cognitive, and cultural achievements that disciplines and fields provide. As with a discipline, it instils those using it “with what the sociologists [sic] Johan Asplund calls ‘aspect vision,’ which allows them to see certain dimensions of a phenomenon [and] offers its members a particular set of lenses, which enables them to see the issue more sharply” (Buanes and Jentoft, Reference Buanes and Jentoft2009: 450). As a tool of “interactional expertise” (Collins and Evans, Reference Collins and Evans2007), the SCF opens up the road for not putting too narrow a limit on issues such as the subject focus, assumptions about the issues one studies, models and methods used, and the audience addressed (Lélé and Norgaard, Reference Lélé and Norgaard2005: 972).

Of course, very different types of conversation can and will come up. Imagine conversations between researchers working broadly within the same ideal type using the same perspectives. If we are both doing bivalent work, with an interest primarily in the ontic and spatial perspectives, then we are likely to share some basic definitions about the kinds of things we are interested in. The main problems we are likely to face are, first, that we are interested in different aspects of each perspective and, second, that we may have different words for them – we speak different sociolects.

Conversations between scholars working with different sets of perspectives, or different ideal types, introduce additional complications. Beyond the problems just mentioned to do with being interested in different aspects of a perspective and different sociolects, the interlocutors here face the difficulty that one or both will regard as fundamental something that simply does not figure in the other’s thinking.

Facilitating conversation across fields is not the universal remedy or even the most important enabler for exchange across various kinds of boundaries. “Institutional impediments related to incentives, funding, and priorities given disciplinary versus interdisciplinary work [and p]rofessional impediments related to hiring, promotion, status, and recognition” (Brewer, Reference Brewer1999: 335; see also Youngblood, Reference Youngblood2007) remain largely untouched. Likewise, while the SCF tries to avoid any kind of conceptual imperialism, the issue of power is always present since “[t]he search for ‘the perfect language’ or a ‘meta-orientation system’ is a search for power rather than comprehension” (Czarniawska, Reference Czarniawska1998: 273). Yet we argue that the SCF helps; it does not reveal things that would otherwise be invisible, but it makes them easier to see.

Following up on this general argument, we now illustrate the potential of the SCF with regard to establishing and supporting conversation in more detail.

Establishing Common Ground

The three perspectives and the ideal types offer a conceptually founded view of seemingly very different activities, allowing participants to detect a new kind of order and common ground at a more abstract level beyond discussing research questions and objects, theories, and methods. Researchers getting into such a conversation can easily identify their relative emphases and basic interests and detect commonalities despite profound differences with regard to constructs, theories, and methods used. This can lead to a shared conceptual pact and situational model that provides the basis for exchange.

A good example of this is a stream of research examining the topic of personality and career success from the perspective of I/O psychology (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, Reference Judge, Kammeyer-Mueller, Gunz and Peiperl2007) and another one looking at occupational choice from the perspective of vocational psychology (Savickas, Reference Savickas, Gunz and Peiperl2007). Although the latter field is much broader than the former, in the sense that it also deals with the decision-making process that the individual goes through in making an occupational choice and the counseling interventions that can help this choice process, it is still fundamentally concerned with the same thing as the personality and career success field. Each attempts to predict career success on the basis of the career actor’s personality. Yet the way they conceptualize career success is markedly different. The OMC topic area linking personality and career success takes a clearly ontic perspective and uses dependent variables such as income or career satisfaction. In contrast, the vocational discussion emphasizes crossing spatial boundaries, in particular into specific vocations, and the individual–job fit. Consequently, they represent different ideal types, the OMC approach being ontic focused and the vocational ontic-spatial bivalent. The temporal does play a role, in the sense that career success is always subsequent to personality measurements, but it does not emerge as an issue of primary importance to either.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, out of the 147 unique references in total cited by the two chapters listed previously that appear in the same handbook (Gunz and Peiperl, Reference Gunz and Peiperl2007a), only one is common to both. In the face of this evidence, there does not seem to be much conversation between the two. A more detailed analysis using the SCF leads to a structured and analytically detached diagnosis suggesting why this might be the case, as we see next.

Leaving aside for the moment the different role that the spatial perspective plays in the two approaches, the ontic perspective provides the most obvious points of contrast between them. To oversimplify in order to make the point, conversation between these two is complicated by superficially similar but actually different applications of the ontic perspective. They are superficially similar in the sense that they are both interested in predicting career success from a knowledge of the actor’s personality. But the two literatures differ strikingly in the constructs that they use to examine the condition of career actors, i.e. how they conceptualize personality and career success.

Targeting personality, the personality/career success literature typically works with personality variables such as the five-factor model (FFM: Judge, Heller, and Mount, Reference Judge, Heller and Mount2002), proactive personality, agentic and communal orientation, and core self-evaluations such as locus of control, self-esteem, and self-confidence (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, Reference Judge, Kammeyer-Mueller, Gunz and Peiperl2007). The vocational literature employs a large variety of instruments based on varying approaches to establishing person–environment fit (Savickas, Reference Savickas, Gunz and Peiperl2007). Some assess the qualifications of the person for a particular job (complementary fit), while others assess their similarity to people who are doing the job (supplementary fit). Examples of these instruments include the Campbell Interest and Skills Survey, the Strong Interest Inventory, and the Kuder Occupational Interest Inventory (Savickas and Taber, Reference Savickas and Taber2006). Holland’s (Reference Holland1959) RIASEC model has become extremely influential in assessing both personality and positions in the vocational literature, and the instruments in common use now typically use its framework.

Turning to career success, the personality/career success literature normally uses standard constructs for viewing objective and subjective success (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, Reference Judge, Kammeyer-Mueller, Gunz and Peiperl2007). The most commonly used objective career success criteria are income, number of promotions, and occupational status, while subjective success is most often measured in terms of the actor’s satisfaction with their career (ibid.). The vocational literature, by contrast, as noted earlier, looks for person–environment fit: how well the person fits either with the requirements of the job or with other people doing it (Savickas, Reference Savickas, Gunz and Peiperl2007). In a 2013 review of the vocational field, for example, career success does not figure prominently in the topics of interest to vocational scholars and not at all in practice articles (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Hou, Kronholz, Dozier, McClain, Buzzetta, Pawley, Finklea, Peterson, Lenz, Reardon, Osborn, Hayden, Colvin and Kennelly2014).

To summarize, then, the SCF allows us to identify with some precision basic characteristics of a conversation between members of the topic area/field. On the one hand, the two we have been discussing here do indeed have a great deal in common. For each, their real interest lies in the ontic. In addition, their use of the ontic reflects the aims of the respective topic area/field. The conceptual pact, then, involves agreeing that each is interested broadly in personality and career success, and the conversation can then proceed by examining why each views these constructs as it does.

On the other hand, the SCF also helps us understand why such a conversation might be difficult. While they are both interested in the link between personality and different forms of career success, applying the SCF reveals that their operationalization of two features of the ontic perspective is incommensurable, that the words and concepts each topic area/field uses have different meanings, and that there is very little connection between them in this regard. By being able to see familiar “facts” in a new light through the SCF, it supplies additional grounds for the conceptual pact between interlocutors from the two areas/fields. Rather than asking the bland question of why is it that two sets of researchers working on similar aspects of careers have so little in common, the SCF provides a conceptual framework that leads the interlocutors to focus in a nonthreatening way on where they are different and what they have in common.

In a similar vein, the SCF can also help establish common ground in cases of more segregated fields of research. While the break between the personality/career success and vocational literatures is one of the more remarkable within career studies, that between OMC and life-course studies is, if anything, an even more remarkable example of a lack of conversation. Until recently, work on the life course went to considerable lengths to avoid the use of the term “career,” and when it did so it did it in a way that made it clear that life-course researchers regarded the career as a subset of the life course. For example, Volume I of the authoritative Handbook of the Life Course (Mortimer and Shanahan, Reference Mortimer and Shanahan2003a) has just one reference to “career” in its index, in which career is defined as “an individual’s sequence of jobs held across the socioeconomic life cycle” (Pallas, Reference Pallas, Mortimer and Shanahan2003: 167). Volume II (Shanahan, Mortimer, and Kirkpatrick Johnson, Reference Shanahan, Mortimer and Kirkpatrick Johnson2016) has many references to the term “career” throughout but almost no reference to the OMC literature. The life course, by contrast, is “the age-graded, socially-embedded sequence of roles that connect the phases of life” (Mortimer and Shanahan, Reference Mortimer, Shanahan, Mortimer and Shanahan2003b: xi). The two concepts are distinguished by the comparatively restricted sense in which life-course scholars appear to think of career:

The concept of “career” was another way of linking roles across the life course. These careers are based on role histories in education, work, or family. Though readily applicable to multiple domains of life, these models most often focused on a single domain, oversimplifying to a great extent the lives of people who were in reality dealing with multiple roles simultaneously. Moreover, much like the family cycle, the concept of career did not locate individuals in historical context or identify their temporal location within the life span. In other words, the available models of social pathways lacked mechanisms connecting lives with biographical and historical time, and the changes in social life that spanned this time.

Perhaps as a result, not only do life-course researchers hardly ever refer to the OMC literature (and many to the term “career”), but career researchers return the compliment by being, on the whole, oblivious of the life-course literature. For example, two major handbooks of career theory/studies (Gunz and Peiperl, Reference Gunz and Peiperl2007a; Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Hall and Lawrence1989b) identify the life course solely with life-course psychologists such as Levinson et al. (Reference Levinson, Darrow, Klein, Levinson and McKee1978), who examined the stages of lives of men in the USA, or the developmental models of writers such as Alderfer (Reference Alderfer1972) or Vaillant (Reference Vaillant1977).

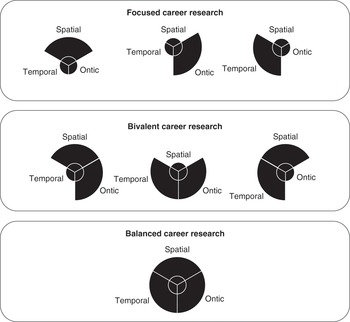

Yet a strong case could be made for the life-course field to be an excellent example of what we call here balanced career research. Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe (Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003: 10ff.) identify five “paradigmatic principles in life-course theory,” which map on to the SCF remarkably well (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Life-course theory paradigmatic principles (from Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe, Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003: 11–13) and the SCF

| Principle | SCF interpretation |

|---|---|

| 1. The principle of life-span development: human development and aging are lifelong processes | Ontic and temporal |

| 2. The principle of agency: individuals construct their own life course through the choices and actions they take within the opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstance | Ontic, temporal, and spatial |

| 3. The principle of time and place: the life course of individuals is embedded and shaped by the historical times and places they experience over their lifetime | Temporal and spatial |

| 4. The principle of timing: the developmental antecedents and consequences of life transitions, events, and behavioral patterns vary according to their timing in a person’s life | Ontic and temporal |

| 5. The principle of linked lives: lives are lived interdependently and sociohistorical influences are expressed through this network of shared relationships | Extended heuristic model (Chapter 4) |

Indeed the life course as defined in the life-course literature resembles at its core the career as we define it in Chapter 3: quite simply, its canvas is the actor’s entire lifetime to date and all of the social and geographic space occupied by the actor during that time. So, to follow the logic of our argument in that chapter, “career” as typically conceived of particularly in the OMC literature is pretty much exactly as it is seen by life-course theorists: a subset of the life course, over a limited time (the time span where one is part of the workforce) and involving only that part of the social space occupied by the actor’s work roles, possibly extended to those (e.g. home life) that interfere with work roles.

Using the language of the SCF, we tend to see more clearly why life-course scholars show little interest in the careers literature: they seem to see it as unduly constrained in its application of the three perspectives. It also explains why career scholars apparently show little interest in the life-course literature. The life-course literature talks about things – early childhood, disadvantaged or unemployed people – who are outside the temporal zone or social space defined by the conventional (post-Chicago) careers literature (see later in this chapter for a fuller account of what we mean by post-Chicago). Yet the temporal zone of interest to careers scholars is creeping forward in time, now encompassing, for example, retirement (Sargent, Lee, Martin, and Zikic, Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2013) or interest in work-life balance (Williams, Berdahl, and Vandello, Reference Williams, Berdahl and Vandello2016). So the intellectual boundaries that career scholars work with are becoming more permeable than previously, suggesting that they may well find conversation with life-course scholars profitable. If only, that is, the conversation could be established.

For this to happen, a conceptual pact needs to be established, and the SCF-based analysis we have just conducted makes it obvious what that pact should be. By framing both fields in terms of the three perspectives, the interlocutors establish conceptual agreement about what it is that they do: each applies the three perspectives to the study of people, but one (life course) has a broader definition than the other (career) of the social space and time that are of interest. So the life-course scholar may help the career scholar by suggesting additional constructs that might be of use in understanding what is going on, while the career scholar might help the life-course scholar by providing more detail about the constructs that the life-course scholar is trying to apply, particularly those to do with organizations.

Overall, the theme connecting our examples with regard to the role of the SCF in establishing common ground can be summarized as follows. In order to establish conversation between career scholars working in different fields of a fragmented proto-field (Chapter 1) or between scholars working in ostensibly different fields that have a great deal in common, it is necessary to establish a conceptual pact between interlocutors. The SCF provides an approach to doing this by offering a way of moving to a more abstract level so that the particularities of each topic area or field’s discourse cease to be an obstacle to communication. That is not to say that everyone needs to abandon their normal way of describing the concepts and constructs with which they work. But by mapping the concepts and constructs on to the SCF perspectives, they can establish the common ground – the conceptual pact – that helps connect their conceptual framework with that of their interlocutor.

Emphasizing Understanding, Evenhandedness, and Social Ties

Beyond establishing common ground, the SCF also pushes conversations between researchers with an interest in various ideal types of career research toward understanding the ideas of others. As a broad heuristic framework, the SCF neither requires nor allows one to judge specific studies to be better or worse than others. Rather, it helps participants in such a conversation to establish a common frame for description and clarification of what they do, thus generating the possibility of mutual understanding. This explicitly discourages the standard academic game of deploring other research only because it either emphasizes different perspectives or uses different constructs and operationalizations within the same perspective or ideal types. Rather, it provides generic categories for mutual, descriptive exchange. There is not per se a right/wrong or better/worse way of exploring the relative emphases of the three perspectives. The joint search concentrates on descriptive information and, hopefully, mutual understanding of what the other does and deems important.

Take the example of two researchers with a clearly bivalent career research interest. Let us assume one is a member of the Cross-Cultural Collaboration on Contemporary Careers (5C; www.5C.careers) looking at the role of various contextual settings differentiated by cultural and institutional characteristics for careers and pointing toward a qualitative eleven-country study (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Demel, Unite, Briscoe, Hall, Chudzikowski, Mayrhofer, Abdul-Ghani, Bogicevic Milikic, Colorado, Fei, Las Heras, Ogliastri, Pazy, Poon, Shefer, Taniguchi and Zikic2015a) that shows how different contexts bring forth differences in what individuals view as career success and how this relates to organizational HRM policies and practices. Its emphasis, then, is clearly ontic-spatial. The other belongs to a group investigating the relationship between general mental ability (GMA), human capital, and career success. She admires a study that draws on data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, covers a time span of twenty-eight years, follows the development of individuals based on yearly (1979–1994) or biannual (from 1995 onward) interviews, and proposes a crucial role for GMA in the form of more intelligent individuals not only reaching higher levels of extrinsic career success by getting earlier promotions but also achieving steeper career success trajectories that, in turn, constitute the basis for a self-reinforcing cycle where skills are amplified and contribute to greater career success (Judge et al., Reference Judge, Klinger and Simon2010). The emphasis of this work is evidently ontic-temporal.

In such a situation, it is not uncommon for academic conversations to head toward a contagious self-enhancing exchange bordering on boasting and openly or tacitly leading to an evaluative, implicitly or explicitly judgmental comparison along the lines of academic superiority and astuteness. Sample sizes, sophistication of methods of analysis, publication channels, and reputation of coauthors fuel a debate that, sooner or later, is likely to end in an implicit “winner-loser” division between the participants in the exchange. This is clearly less likely to happen within the realm of the SCF. As a framework, it does not qualify very well for a conversational turn toward “winning-losing.” Within the SCF, it is hard to imagine building a credible claim that “ontic-spatial,” as is the case with 5C, is a better form of bivalent research than the “ontic-temporal” emphasis of the study on general mental ability. The SCF also does not imply that one of these bivalent approaches or even balanced studies constitute the “ultimate coronation” of career research. Sure enough, these claims can be made. But they have to come from outside the SCF and require additional arguments, assumptions and – often implicit – value judgments. At its core, the SCF invites systematically guided inquiry to better understand what the other does, to dig deeper and to get a better map about the respective efforts with regard to condition, boundary, and time on different levels of social complexity.

Focusing on understanding rather than proving one’s own superiority and being relaxed about various kinds of outcomes of the conversation also shifts the focus toward the personal relationship. Not only are such an exchange and its tacit evenhandedness compatible with the rhetoric of science being a joint effort of equals. They also at least implicitly convey the basic notions of esteem and acceptance. “Here we are, two professionals interested in partly similar, partly different aspects of careers, having an informed conversation detecting commonalities and differences while referring to a framework that constitutes a starting point for common ground, generic enough to capture our views and classify our emphases while not in itself promoting better/worse or right/wrong judgments” – this or a similar inner image of individuals participating in such a conversation has the potential to strengthen social ties by providing commonalities and strengthening self-esteem.

Identity-Related Conversations: A Narrative of the OMC Field’s History

“Who are we and where do we come from?” – this is a topic not only of melancholic late-night bar conversations dealing with the mysteries of personal life but also of ongoing debates in scientific fields. Attributing roles, causality, and influence to scholars deemed important in the field, schools of thought, and publications are but a few ways of making sense of what has happened in the past and what that means for today’s scientific endeavors. Of course, there is no objective truth to be reached. History is always in the making, told as a result of various narratives offering different interpretations, and usually overtly or subtly driven by a political agenda or by personal or scientific interest.

In this section, we provide a narrative of the OMC field that informs these kinds of conversations. Using the SCF and the related ideal types, we invoke the notion of a present-day careers researcher reading earlier work, trying to connect with it through the medium of an imaginary conversation with the authors of that work, and making sense of what has happened in the past. Given obvious space limits as well as the fact that we are part of the field, this narrative is a very partial account. Our purpose is simply to show how the SCF and, related to it, the ideal types provide a useful analytical tool when constructing a narrative about the OMC field.

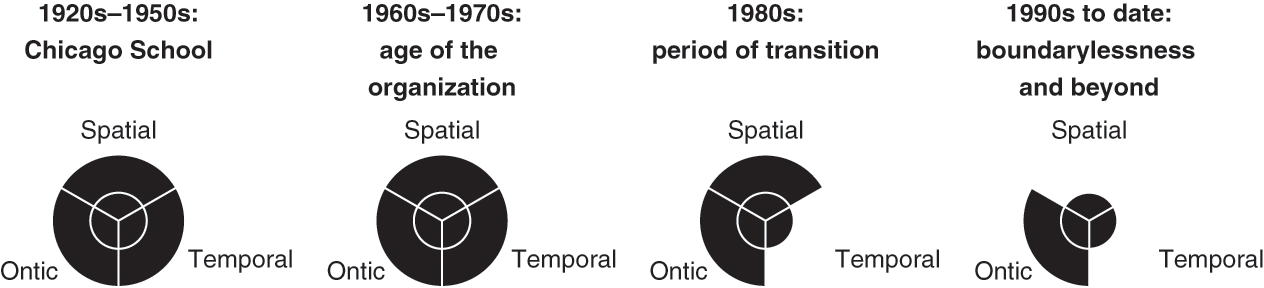

The Chicago School

It has been suggested that the current field of career studies has its roots in three intellectual traditions coming from, respectively, sociology, vocational psychology, and developmental psychology (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Gunz, Hall, Gunz and Peiperl2007). These differing traditions have left their mark on the field, most notably in what is sometimes described as the almost unbridged gulf between organizational and vocational career studies to which we refer in Chapter 1 (Collin and Patton, Reference Collin and Patton2009). The story we shall be telling here, which we acknowledge is a partial one leaving out a lot of interesting threads, focuses on the seminal role of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) school in the 1970s. It ignores career research happening elsewhere in the USA, most notably at Cornell (Vardi, Reference Vardi2006; Dyer, Reference Dyer1976), and outside North America (for one national example, Germany, see, e.g. Domsch and Gerpott, Reference Domsch and Gerpott1986; Gerpott, Domsch, and Keller, Reference Gerpott, Domsch and Keller1986; Berthel and Koch, Reference Berthel and Koch1985; Eckardstein, Reference Eckardstein1971). In order to do so, we need to take one further step back in time to examine another school of thought, coming from the Chicago Department of Sociology, that plays a key role in the way that the MIT group’s ideas developed (Barley, Reference Barley, Arthur, Hall and Lawrence1989).

The 1930s were a difficult time in both Europe and North America, both economically and politically. They also saw the rise of large industrial bureaucracies on both sides of the Atlantic and, with that trend, an increase in the number of people making their careers in these bureaucracies (Hughes, Reference Hughes1937). The sociologist Everett C. Hughes returned to his PhD alma mater, the Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago, in 1938, where there was a tradition of producing “ethnographies of deviant subcultures based on the life histories of people who partook of the subculture. Notable among these were Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1923) study of hobo life, Cressey’s (Reference Cressey1932) description of taxi-dance halls, and Sutherland’s (Reference Sutherland1937) work on professional thieves” (Barley, Reference Barley, Arthur, Hall and Lawrence1989: 43). Hughes, as a student of his mentor, Robert E. Park (whom he quoted “all the time” to his students; Becker, Reference Becker1999: 7), developed his interest in the effect on the person of moving through and between what he termed “institutional offices” (Hughes, Reference Hughes1937). The so-called “Chicago school,” a term much criticized by one of its members, Howard S. Becker, who tells the story (Becker, Reference Becker1999) of a typical academic department in which colleagues are at loggerheads about their various theoretical and methodological approaches, produced a long stream of research on careers, where the career is seen as encompassing the person’s entire life (as we note in Chapter 3).

In SCF terms, it is a classic example of balanced research. The ethnography is rich, describing the people, their contexts, and the stages through which their careers progress. As we see in Chapter 2, Hughes views careers both subjectively and objectively. Subjectively and from an ontic perspective, the Chicago sociologists are interested in the meanings that the people they study attribute to their careers (Barley, Reference Barley, Arthur, Hall and Lawrence1989). Objectively and spatially, they are interested in the institutional forms in which their subjects make their careers and how they move through these forms. And temporally, they are fascinated by the stages through which their subjects pass as their careers progress (perhaps the best-known of these studies being Roth, Reference Roth1963); the concept of status passage (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1971) is central to their thinking.

1960s and 1970s: The Age of the Organization

Societal and Economic Developments

Both the 1960s and the 1970s were turbulent times in the Western industrialized world, which, at least at that time, dominated the societal and economic developments across the globe. At the societal level, many countries of the Western industrialized world in the 1960s still felt the aftermath of World War II, which had raged until 1945. However, new developments were starting to develop in the early 1960s and were seeing full daylight at the end of this decade. Most notably, three developments have to be mentioned. First, the 1968 movement emerged. Self-realization and self-development, the importance of the individual as part of a more communitarian society, the so-called sexual revolution including the emergence of the birth control pill, and skepticism of the establishment and the long-standing order emphasizing well-established hierarchies are but major cornerstones of a societal movement that laid the groundwork for many developments in later years. Second, and linked to the developments just mentioned, the civil rights movement gained momentum. Rosa Parks and her “transgression” when refusing to be seated in the colored section of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, on December 1, 1955, ignited a freedom movement in the USA that lasted well into the 1960s. Third, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and its satellite states and the Western democratic world, in particular the USA – more broadly between a communist and a capitalist view of the world – was in full swing in the 1960s. Major occurrences such as the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962 and the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the armies of the Warsaw Pact in 1968 are two primary examples. In addition, the Vietnam war, which continued until the fall of Saigon in April 1975, testifies to this basic tension. In the 1970s, the women’s movement gained great momentum, paving the way for various waves of feminism still having large effects on society today.

Economically, the 1960s and ’70s were the heyday of large multinational companies impacting business around the globe. Industry icons such as Unilever, IBM, General Motors, and British Petroleum were global players. Basically, optimism regarding postwar growth and economic prosperity dominated. However, the first signs of skepticism emerged. Most notably, these included first doubts about the positive aspects of growth voiced in a widely acclaimed report of the Club of Rome conjuring up the new concept of limits of growth (Meadows, Meadows, Randers, and Behrens, Reference Meadows, Meadows, Randers and Behrens1972) and the oil shock in 1973. The latter also introduced renewed doubts about Keynesian politics and offered an inroad for neoliberal economic theory and politics due to fears of stagflation.

Two themes from these macro-developments are relevant for understanding what happened in the career discourse. First, organizations, in particular large organizations, were a major element of the economies. Spreading across national and cultural boundaries, they seemed to be the role model for a new and bright future. Second, the individual and their development, often linked to self-realization and agentic determination of one’s life course as opposed to being organization men and, increasingly, women, received new attention in the societal discourse. As we shall argue later on, these themes were instrumental for the focus on organizations and on time in much of the career discourse of this period.

Social Science Discourse

The period of the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s was not only a time of substantial change in the societal and economic fabric of the Western industrialized world. It was also a time when major theoretical breakthroughs of the 1950s bore fruit and new seminal works emerged on organizations, individuals, and their relationship, influential far beyond the decade. These include “radical” new ways of theorizing organizations, the role of the social/individual in organizations, and individual behavior. Many of these insights were theoretical cornerstones of current work and serve as benchmarks until today. It is hardly pure coincidence that both the Carnegie Foundation’s report on university-college programs in business administration (Pierson, Reference Pierson1959) and the Gordon and Howell report (Gordon and Howell, Reference Gordon and Howell1959) on higher education for business point out a number of substantial weaknesses in the contemporary educational system in the USA. Among other things, they recommend a stronger anchoring of organization studies in social science and mathematics. Although not causal, these calls are at least partly reflected in the major theoretical steps within the scientific discourse that follow.

In a nutshell, the major works in this area get rid of an overly simplistic, machinelike model of individual actors and organizations. They emphasize the social element, at least partially questioning an unbroken belief in objective insight and truth, and underscore the manifold individual and social filters when constructing reality. From a management theory perspective, the relationship between the individual and the organization and the organization-individual-(mis)fit are prominent themes. While space prohibits a full account, a few examples may suffice.

Conceptualizing Organizations

In the footsteps of earlier landmark publications summarizing, critiquing, and synthesizing the respective state of affairs in previous decades (in particular Barnard, Reference Barnard1971 [Original 1938]; Simon, Reference Simon1957 [Original 1947]), March and Simon (Reference March and Simon1958) published their seminal work on organizations. They go beyond the view that hierarchy is simply a chain of command and emphasize its information processing function as well as point toward the limits of rationality (“bounded rationality”) when it comes to decision making. Other early works published in Anglo-Saxon countries address the difference between mechanistic and organic organizations (Burns and Stalker, Reference Burns and Stalker1961); pick up the issues of charisma, power, and compliance (Etzioni, Reference Etzioni1961); or discuss the tensions between hierarchy and competence or authority and ability/specialization (Thompson, Reference Thompson1961). Works like these pave the way for a stream of ideas about theorizing organizations in the 1960s and the 1970s. By means of example rather than completeness, these include the role of structure (Blau and Schoenherr, Reference Blau and Schoenherr1962) and formal organization (Blau and Scott, Reference Blau and Scott1962); rethinking organizational decision making and moving it further away from the realm of pure rationality toward uncertainty avoidance, quasi-resolution of conflicts, and organizational learning (Cyert and March, Reference Cyert and March1963) or comparing it to a garbage can with retrospective rationality applied in organized anarchies (March and Olsen, Reference March and Olsen1976); the limits of classical management principles along Tayloristic lines and the role of production technology for explaining structure and leadership (Woodward, Reference Woodward1965); discarding the concept of organization as a solid block and favoring organizing as a dynamic process along the lines of evolutionary theory with a focus on the double interact between Person and Other (Weick, Reference Weick1969); viewing hierarchy or internal organization as the superior mode of allocation under conditions of market failure and where trust is required for exchange to occur (Williamson, Reference Williamson1975); focusing on how organizations, viewed as open systems operating under the dictum of rationality and needing determinedness and certainty, reduce uncertainty coming from their environment and the technology they use (Thompson, Reference Thompson1967); diving into the peculiarities of an open system view and trying to connect sociological and psychological views of organizations (Katz and Kahn, Reference Katz and Kahn1966); understanding organizations and their relationship to employees and customers in times of concern and conflict through the three basic options of exit, voice, and loyalty (Hirschman, Reference Hirschman1970); and pointing out the importance of power relations and the dependence of the organization on the external environment and important stakeholders (Pfeffer and Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978).

Works like these have turned out to be classics and triggered numerous streams of research and publications. Among others, they have also influenced more regional scientific debates about how to conceptualize organizations. For example, in the German language area, the 1970s were characterized by a sometimes furious debate about what organizations, in particular companies, “really are” and how they can be theorized. Departing from the classical views linked to production factors (Gutenberg, Reference Gutenberg1958) or techno-economic views (Kosiol, Reference Kosiol1972), new approaches emphasized decisions in organizations (Heinen, Reference Heinen1972), the systems-quality of organizations (Ulrich, Reference Ulrich1970), behavioral aspects of organizations (Schanz, Reference Schanz1977) or the importance of social aspects when managing organizations (Staehle, Reference Staehle1980).

Overall, there is a clearly discernible undercurrent linking these works and their ideas. Organizations and the individuals working in them are a far cry from machinelike entities. Rather, they teem with life and power. Conflicts and contradictions, uncertainties, decisions, and the like play an important role alongside formal structures and processes. As such, they are a social universe in their own right with specific characteristics, in particular formalized internal structures and processes and the embeddedness in their broader environment with special ties to the economic and legal sphere.

Behavior and Organizations

As with the major new developments in theorizing organizations in general, the 1960s and ’70s witnessed substantial works focusing on organizational behavior at the collective level as well as individual behavior in general and behavior in organizations in particular. Again a few, highly selective examples must suffice. Various views of organizational behavior were put forward (e.g. Schein, Reference Schein1965; Argyris, Reference Argyris1960); theorizing on motivation in general included dissonance theory (Festinger, Reference Festinger1957), need hierarchy (Maslow, Reference Maslow1962) and the structure of human needs (Alderfer, Reference Alderfer1972), achievement motivation (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson1966; McClelland, Atkinson, Clark, and Lowell, Reference McClelland, Atkinson, Clark and Lowell1953), or intrinsic motivation (Deci, Reference Deci1975); theoretical considerations about motivation at work comprise, e.g. theory X/Y (McGregor, Reference McGregor1960), the interplay between satisfiers and hygiene-factors (Herzberg, Reference Herzberg1966), or the role of expectancy (Vroom, Reference Vroom1964). Later on and with a clearly different starting point and line of argumentation, the economic calculus turned more prominently to the analysis of human behavior (Becker, Reference Becker1976).

Again, a common thread runs through these viewpoints. No longer is “economic man” the only legitimate point of reference whose behavior is guided by rational decisions linked to materialistic preferences. Other issues such as basic motives and needs, a broad array of goals from different areas of life, and economic considerations constitute a unique mix for understanding what drives individuals and how they deal with their immediate and long-term concerns in life in general and work life in particular. As such, taking a broad, multidisciplinary view of individuals becomes essential for every thorough analysis looking at behavior and organizations.

Learning and Development

Both at the individual and the organizational level, development and learning became an area where new concepts emerged. They addressed important issues, offered a solid theoretical background, and became the basis for much subsequent research. A few examples can illustrate this. At the individual level, the importance of model learning going beyond relying solely on the feedback of one’s own action (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977b) greatly added to the existing views on learning and built on the notion that individuals are cognitive beings and active processors of information. At the organizational level, an elaborate view of types of learning differentiated between single- and double-loop learning, the latter questioning the given frameworks and learning systems of the status quo, which also made clear that organizations as a whole can learn (Argyris and Schön, Reference Argyris and Schön1978). Looking at various transitions across different areas and stages of life, a model with universally applicable dimensions of transitions – reversibility, temporality, shape, desirability, circumstantiality, and multiple status passages – emerged (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1971).

What holds these approaches together is a strong awareness of and emphasis on the dynamic quality of life in general and work life in particular. The developmental aspect underscores the importance of taking a long-term view and being sensitive to different stages or phases of life with their respective idiosyncrasies. Learning focuses on the relationship between the entity of interest, e.g. an individual or an organization, and its environment and the continuously ongoing and required processes of reaction and adaption to the environment and its changes.

Career Studies

Against the backdrop of these developments at the societal and scientific level, it is little wonder that career studies during the 1960s and 1970s addressed a number of themes matching the scholarly zeitgeist. A first theme addressed organizations as an important element of social space when looking at careers. While this stream of research does not necessarily assume that careers are only taking place within organizations, organizations were a central point of reference. A number of well-known works from this area dealt with various facets of careers in organizations (e.g. Van Maanen and Schein, Reference Van Maanen, Schein, Hackman and Suttle1977; Hall, Reference Hall1976), their theoretical underpinnings (e.g. Glaser, Reference Glaser1968), the relationship between individual and organization when it comes to careers (e.g. Schein, Reference Schein1978; Dyer, Reference Dyer1976), the types of persons found in organizations (e.g. Maccoby, Reference Maccoby1978), or the specifics of moving in the organizational hierarchy (e.g. Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum1979b; Jennings, Reference Jennings1971; White, Reference White1970).

A second theme partly zoomed in on organizations and, at the same time, went across organizations and revolved around careers of specific groups, professions, and occupations (e.g. Sarason, Reference Sarason1977; Strauss, Reference Strauss1975; Slocum, Reference Slocum1966). Examples include scientists (Glaser, Reference Glaser1964), scientists and technical engineers (Zaleznik, Dalton, Barnes, and Laurin, Reference Zaleznik, Dalton, Barnes and Laurin1970), managers (e.g. Guerrier and Philpot, Reference Guerrier and Philpot1978; Bray, Campbell, and Grant, Reference Bray, Campbell and Grant1974; Lorsch and Barnes, Reference Lorsch and Barnes1972; Eckardstein, Reference Eckardstein1971), technical specialists (e.g. Sofer, Reference Sofer1970), school superintendents (e.g. Carlson, Reference Carlson1972), minorities (Picou and Campbell, Reference Picou and Campbell1975), or medical students (e.g. Becker, Geer, Hughes, and Strauss, Reference Becker, Geer, Hughes and Strauss1961). Here the underlying assumption is that the specifics of these groups, i.e. the individuals attracted by and selected through the respective field as well as the characteristics of the field, provide “standardized,” “universal” insights related to careers.