Chilpapalotl kept playing the words through her head: thank the gods, offer incense, work hard at household tasks, eat and drink well, don’t chew chicle, don’t get angered or frightened, don’t look at anything red, don’t eat earth or chalk, don’t lift heavy things, don’t overdo the sweat bath (but what a temptation!). Her parents, her grandparents, everyone, had been repeating these words to her for months. And more recently, the midwife. She knew it was well-intended and that they loved her, but enough is enough! By now she knew all of this by heart.

Can’t they see how exhausted she is, with her precious jewel getting bigger and bigger and more active day by day? Her belly was so big now that she could no longer bend over the metate to grind the morning maize, and weaving was a bit of a stretch. She found herself going less and less to market, and got out of breath just walking around the house. And the heartburn! She could still spin thread, though – that was almost therapeutic. But she couldn’t sit still for long, especially for those lectures.

She looked forward to the visits from her midwife Cuicatototl, because that meant that she could retreat into the temazcalli, the sweat bath, which was so relaxing. Cuicatototl got the sweat bath temperature just right and massaged her belly, which made her feel so much better! Soon, if all went well, her precious jewel, her precious feather would become the newest member of the family. Soon.

Even though Chilpapalotl quietly complained, remembering all of the lectures and admonishments of her elders by heart was, in fact, the point. Even though Chilpapalotl was supremely uncomfortable, with only about one Aztec month (twenty days) to go, she managed to discipline herself and sit through the endless talking. It was all part of the necessary and scripted narrative that preceded the birth of an Aztec child.

Anticipations

Children were highly valued in Aztec society, so it comes as no surprise that great care and precautions were taken to ensure full-term pregnancies and successful births. Established procedures were followed to assure the health of both the mother and the baby, along with the favor of the gods. These procedures hit high points at four major moments: when the pregnancy first became known, during the seventh or eighth month, at the time of birth, and four days following the birth.

There is need for one small caveat here: most of our information on these procedures comes from the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who compiled his accounts some fifty years after the Spanish conquest. Although his Historia was written in Nahuatl and illustrated by native scribes, much Spanish ideology and culture crept into the account. In this case, which calendar is being followed? The Christian calendar contained twelve months, the Aztec calendar was composed of eighteen. So was the seventh or eighth month in the third trimester (in the Christian count), or less than halfway there (in the Aztec calendar)? Our guess is that the Christian calendar is the referent here, given the activities of the midwife at this stage. Similarly, the details of the bathing of the newborn child should be looked at as perhaps infiltrated by motions and narratives associated with Christian baptism.

When a pregnancy became known, there was great rejoicing and the relatives of the parents-to-be assembled to celebrate in cozcatl, in quetzalli (“the precious necklace, the precious feather,” i.e., the baby). Feasting and lectures were highlighted. Feasting at this early rally would have differed in abundance and sumptuousness from household to household, depending on the householders’ economic wherewithal. Food and drink were prepared, if possible augmented with flowers and tobacco tubes. Eloquent speeches were first presented by the older relatives, “the white-haired ones, the white-headed ones” (in tzoniztaque, in quaiztaque; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 135), who opened the orations with exhortations about the importance of the moment and the need for prayer and reverence to the omnipotent gods who have given this precious gift to the woman. There was quite a bit of talk about all the things that could go wrong, and the possibility that the gods who had generously given this life can as readily take it away – much of this perhaps comes across as rather dismal and depressing to a modern reader, but it probably was well-taken by an Aztec listener who deeply believed in the power of the gods and the omniscience of fate.

Following the eloquent words spoken by an older relative, the father-to-be’s parents addressed their daughter-in-law, reminding her that the gods have favored her, exhorting her to thank them, admonishing her to not become proud, and advising her to take special care to not abort this tender gift from the gods. At this point, apparently it was fine for the pregnant woman to still be “diligent in the sweeping, the cleaning, the arranging of things, the cutting (of wood), the fanning (of the fire), and the offering of incense” but she should not lift heavy objects, view anything frightening, or overdo sweat bath sessions (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 141–143; Figure 7.1a, b). At the same time, her husband was admonished to limit his romantic advances, as these may cause the baby to be born weak and lame, or even be stuck in the womb. The old men and women then took over the monologue with loving and caring words. This was all quite lengthy and repetitive, but it was not over yet. Another relative took up the artfully crafted narrative, followed by eloquent words of the pregnant woman’s parents, and finally a humble response by the pregnant woman herself. This was a signal life-cycle event, and it appears that several important relatives in attendance were allowed to speak, offer advice and moral support, and respond to others. They all, repeatedly, underscored the primacy of the gods and the fragility of life, tossing in bits of practical advice here and there. It is possible that the in-laws were a bit “on stage” vis-à-vis one another at this event.

Figure 7.1. Sweat baths, ancient and modern. (a) An Aztec sweat bath. Codex Magliabechiano (1903: f. 77r). (b) A present-day Nahua sweat bath.

It was convenient that, as the woman’s pregnancy progressed and her belly grew, she had no real need of special maternity fashions. The traditional female attire of tunic or cape and skirt were conveniently constructed to fit women at whatever stage of life – the tunic and cape were loose and draped in any event, and the skirt was worn by gathering up the material around the waist and could be expanded or contracted as needed.

A second feast rallied the relatives again and took place when the pregnancy was around seven to eight months along. At this time there was more eating and drinking and eloquent speaking, and also discussion as to the selection of an appropriate midwife. A recurring theme of these and the earlier speeches was the new baby as the “thorn, the maguey” (inhuitz, inmeuh) of the great-grandfathers that is now metaphorically sprouting (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 142). That is, the lectures emphasized, again and again, that the pregnant woman and her baby were carrying on the bloodline and the traditions (in tzontli, in iztitl: the hair, the fingernail) of the revered ancestors from a distant but continuous past – a daunting social responsibility. These speeches also reiterated the supremacy and benevolence of the gods and the tenuousness of life.

On that same occasion, or perhaps shortly after, the midwife was selected. Once chosen by the assembled relatives, the midwife took center stage – the pregnant woman was now placed in the hands of this skilled practitioner.

The Midwife (Ticitl, Temixiuitiani)

Midwives were female medical specialists who assisted women in pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum situations. They shared the name ticitl with male and female physicians who performed services such as setting broken bones, lancing and stitching wounds, and treating eye and other ailments (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 10: 30, 53). The seventeenth-century Spanish priest Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón mentions, with some Spanish editorializing, that the name ticitl is “accepted among the natives as meaning sage, doctor, seer, and sorcerer, or, perhaps, one who has a pact with the Devil’” (Andrews and Hassig Reference Andrews and Hassig1984: 157). He adds that midwives were also called tepalehuiani (“helper”) and temixiuitiani (“midwife”; also in Molina Reference Molina1970: 97v). Like other physicians, midwives called on supernatural intervention as well as natural aids and remedies.

A midwife had weighty duties and responsibilities before, during, and after a birth. A skilled midwife was experienced in the practical side of facilitating successful pregnancies and childbirths. This included emphasizing many important dos and don’ts for the expectant mother. As an advisor, the midwife was equipped with a vast armory of practical advice, each rule coupled with its own scary consequence. For instance, a nap during the day would result in a child with “abnormally large eyelids”; chewing chicle resulted in a child with abnormal lips and therefore unable to suckle; eating earth or chalk meant a sickly child would be born; lolling in a too-hot sweat bath caused the baby to roast and be stuck; and if the mother fasted, the child would starve (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 156–157). If the mother did not take precautions during a lunar eclipse by placing an obsidian knife in her mouth or near her breast, her child would be turned into a mouse or born without lips or a nose, cross-eyed, or otherwise imperfect (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 7: 8–9). The midwife was well aware of the expectant mother’s uncomfortable condition and she recognized the pressure on her charge’s lower back, her need to change positions, her difficulties in getting up and down, and her overall discomfort. So some of her advice was more positive: the expectant mother was admonished to eat well, to take on only light household tasks, and to avoid being startled or frightened. All of this was heard by the mother’s immediate relatives, and the advice was certainly aimed as much at them as at her.

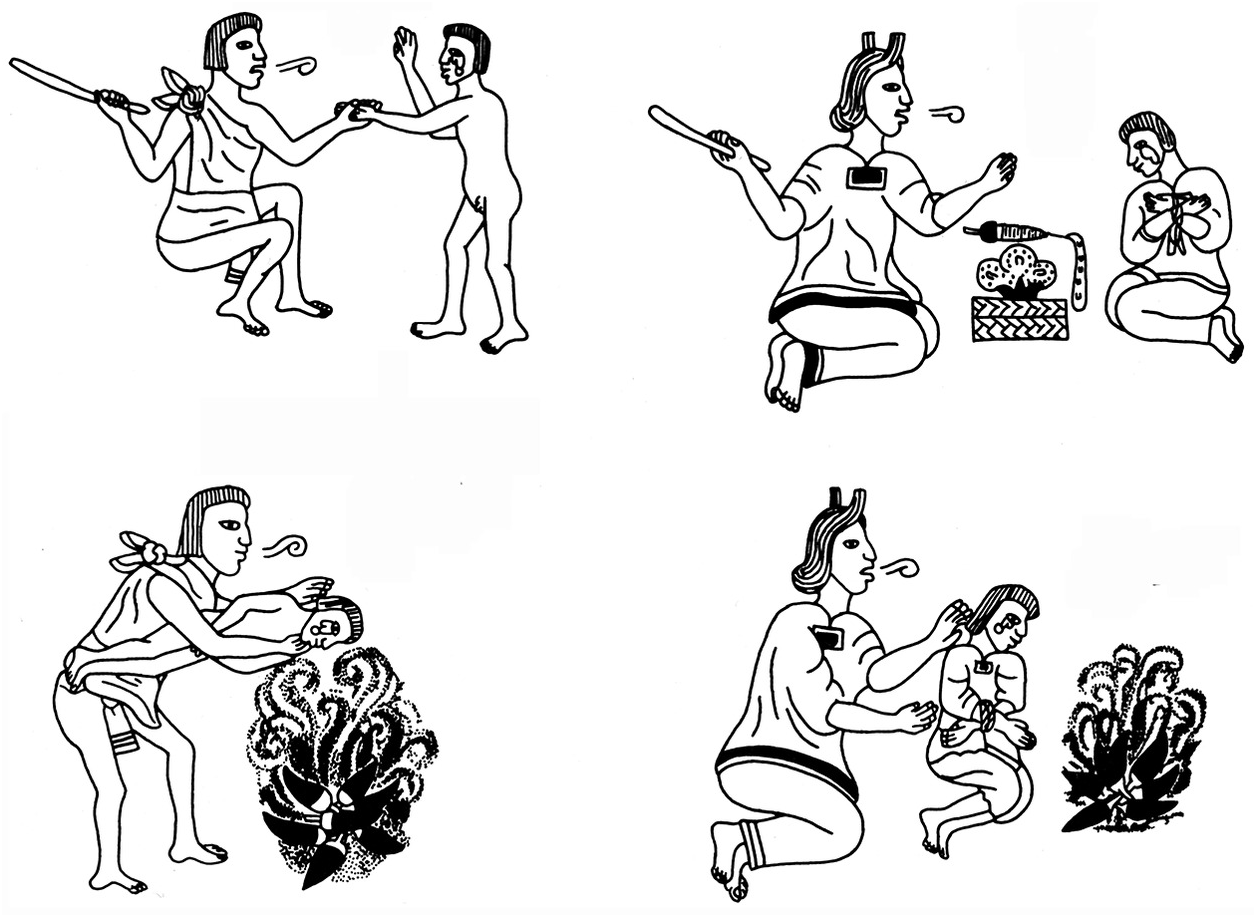

The midwife’s practical work also included proper use (and temperature) of the sweat bath and positioning the fetus by aggressively massaging the mother’s belly (Figure 7.2). The midwife also commanded specialized knowledge of herbal and other medical aids, especially the herb cihuapatli (“woman’s medicine”) and the careful and strategic use of pulverized opossum tail – both helpful in alleviating difficult births. She was expected to be capable, knowledgeable, and effective in facilitating births, managing postpartum procedures, and introducing the baby to its new world. She also must be adept in handling stressful childbirth emergencies that may crop up.

On another plane, it was also necessary that the midwife be well-versed in the roles and efficacy of the goddesses that could help or harm her work and her charges. Particularly important were Yohualticitl, grandmother of the sweat bath; Quilaztli, a warrior version of the mother goddess Cihuacoatl (“Woman Serpent,” and, along with a related goddess Toci, a patroness of the midwives); and Chalchiuhtlicue (“Jade Her Skirt,” a water deity called on during a baby’s bathing ceremony) (Berdan Reference Berdan2014: 232). In scripted dialogues with the midwife, the expectant mother’s elderly female relatives recognized that the midwife was “the skilled one, the artisan of our lord,” but that her duty was to “Aid our lord; help him.” They charged her to “Take up thy charge … Aid Ciuapilli, Quilaztli” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 152, 155). The midwife was a helper, of both the pregnant mother and the gods.

Failure, resulting in the death of mother or child or both, was a very real and recognized possibility. Midwifery had its share of risks and dangers, which even worked their way into metaphoric speech: “of a midwife, when she would cure [the child], if it just died in her care, it was said: ‘Thou hast shattered it; thou hast broken it’” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 249). Still, whether she succeeds or fails is not entirely hers to determine – it is in the hands of the gods. Much familial and midwifery dialogue stresses, over and over again, that the gods may not will this child to live or the mother to survive her ordeal. Still, midwives were practical, active players and not just instruments of the gods: they associated with one another and surely must have talked about difficult or unusual cases.

In addition to information sharing, they may have taken some comfort in mutual camaraderie. They shared a patron deity and celebrated annual ceremonies as a group; notably, during the month of Ochpaniztli they were major celebrants in highly scripted dances and other roles – all requiring a good deal of group practice and coordination. In specific cases, noble women could expect to have more than one midwife at their service, the “head midwife” assisted by others (who were perhaps neophytes still undergoing their training). We do not know what midwives charged for their services, but it would be expected that wealthier families could afford more experienced and extensive care. This may also have resulted in higher survivability of both mother and child among the elite, although we also do not know this for sure.

Back at the house of the mother-to-be, the chosen midwife was asked to join in a feast and dialogues with the relatives of both anticipating parents. Elderly kin spoke in turn, entreating the midwife to take the pregnant woman into her wise and capable care. The midwife responded in self-deprecating tones, elaborating on her responsibilities and expectations as a midwife, and proceeding to take over the process. At this time, admonitions and actions were both ideological and practical. After reiterating her reliance on the gods, the midwife fired up the sweat bath or temazcalli, called xochicaltzin (“revered flower house”) in this context. Within this toasty environment, the midwife massaged the woman’s extended belly, positioning the baby for birth. She apparently continued the sweat bath and massage treatments until birth was imminent.

The Birth and Four Days After

The Baby’s Arrival

As the time for giving birth approached, the pregnant woman’s family summoned the midwife so she was on hand for the highly anticipated (and in some ways highly dreaded) event. If the family was noble or wealthy, the midwife might arrive at the household four or five days early; poorer families probably could only afford to call on the midwife at the onset of labor pains. In either event, the mother was bathed in the sweat bath and given a drink prepared with the cihuapatli herb, a known expellant. If that failed to hasten the birth, an infusion of ground-up opossum tail (with water) was given to the woman to drink (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 159). The usual birthing position was squatting, with gravity assisting. But if the baby was stubborn, the midwife would help gravity along; she “suspended the woman (by the head); she proceeded to shake her, to kick her in the back” all the while entreating the woman to “exert thyself” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 160).

These aids and strategies to speed up the birth were standard in Aztec life. The herb cihuapatli, “woman’s medicine,” is described in the Badianus herbal as one of several concoctions used to ease parturition (Gates Reference Gates2000: 106; Figure 7.3). Sahagún mentions it as a drink, but the Badianus herbal also suggests that its leaves could be ground up with tomato root and opossum tail, used to wet the womb. This herbal of 1552 also mentions other remedies: one is a drink from the bark of the quauhalahuac tree. Another was an anointing concoction of animal hairs, bones, gall (of cock and hare), deerskins, eagle wings, and onions all burned together, to which was added salt, pulque, and prickly pear cactus fruit. A greenstone and a “bright green pearl” could be “bound on her back” (Gates Reference Gates2000: 106). Some of the ingredients of these remedies, such as the greenstone, pearl, and eagle’s wing, might only be within the purview of wealthy nobles. Others were probably more widely available, but still seem to have involved something of a treasure hunt. Among these was the most intense expellant, the tail of an opossum. This was so powerful it was used only in the most dire circumstances.

Chilpapalotl was exhausted. She remembered, remembered well (!) the labor pains that engulfed her very being, over and over again. She vaguely recalled the midwife leading her to the sweat bath and giving her something to drink. After she drank it, the contractions came faster and harder, and it wasn’t long (or so she thought, she really had no sense of time) before the baby emerged. Through all of that, the soothing and sonorous words of the midwife helped calm her down. Her parents had insisted on this midwife – her name, Cuicatototl, meaning “Singing Bird,” said it all. Through all the pain, Chilpapalotl somehow felt as though she was in a room full of birds! Still, she had just wanted out of that room and onto her familiar petate (mat). Then suddenly she had heard the bold, unbelievably loud war cries from Singing Bird’s mouth. Yes! She knew that soon she would be holding her baby, her precious jewel, her brilliant quetzal feather. She had won her battle, just as everyone had hoped. Still, she knew she must thank the gods who held the fates of everyone, including her new one, a little boy, in their hands.

Chilpapalotl’s drink was surely cihuapatli leaves (most likely Montanoa tomentosa) mixed with water. It was a well-known and widely used herbal relief, sometimes used in difficult births to induce and/or shorten labor (Ortiz de Montellano Reference Ortiz de Montellano1990: 185; Pomar Reference Pomar and Garibay1964: 215; Santamaría Reference Santamaría1978: 242). There apparently were several species of this useful plant – Francisco Hernández, traveling in New Spain in the 1570s, describes twenty-three different plants called cihuapatli, many of them named after their location, which could be lowlands, highlands, or household gardens (Reference Hernández1959, vol. 1: 293–299). So it was widely available. He reinforces the accepted wisdom that these plants aided women in childbirth and other womanly medical matters, hence their name (cihua = woman). The midwife may also have rubbed Chilpapalotl’s stomach with crushed tobacco, and added aromatics such as copal incense and yauhtli (a marigold) flowers to the sweat bath (Andrews and Hassig Reference Andrews and Hassig1984: 159). All of this helped to relax her, along with Cuicatototl’s calming voice.

The midwife’s war cries signaled that the baby had been successfully born and that the mother “had fought a good battle, had become a brave warrior, had taken a captive, had captured a baby.” The midwife continued honoring the fatigued woman, calling her an eagle warrior, a jaguar warrior, a warrior who has returned “exhausted from battle” – all putting her on an equal plane to her male warrior counterparts (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 167, 179). But then the midwife changed her tone, warning the woman to not be proud, presumptuous, or a braggart, for the baby was considered the property and creation of the gods and they could still take away her precious little jewel. As the woman rested, her older relatives and the midwife engaged in rather lengthy and apparently scripted dialogues, in every speech being humble, deferential, and grateful to the gods who could will either good or evil to this newborn child. They reminded one another of the omniscience of the gods and the tenuousness of life here on earth.

Upon birth, the baby was welcomed into this world with lengthy, prepared (memorized) lectures, spoken by the midwife (lectures began early in this culture!). Whether boy or girl, the midwife warned the baby that he or she had arrived in a world of fatigue, torment, misery, and travail, but perhaps gaining some merit by the favor of the gods. The midwife introduced the infant to its grandparents (and certainly other relatives). After additional (less than cheerful) words to the child and its relatives, the midwife removed the afterbirth and buried it in a corner of the house (it is not known if the afterbirths of subsequent children were buried in the same or different corners). She then cut the umbilical cord.

The cutting and disposing of the umbilical cord was no small thing. If the baby was a boy, the cord was dried, attached to a small shield with four little arrows, this assemblage later given to distinguished warriors to bury on a battlefield (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 4: 3). If the baby was a girl, the cord was buried in the home by the hearth and grinding stone. In both cases, these acts presaged the futures of adult Aztec men and women: men would become warriors and women would work in the home. Like all the prior activities, this occasion was highly ritualized and again the midwife addressed the infant in what resembles a carefully crafted performance. If a boy, the baby was dedicated to a life of war; if a girl, she was expected to live her life in the home, at the hearth. The boy will become an eagle, a jaguar, a roseate spoonbill who will leave his nest; the girl will stay at home preparing food and drink, grinding maize, spinning, and weaving. To ritually assure these complementary futures, the boy’s umbilical cord ended up on a field of battle (symbolically drawing him outward, to war), the girl’s was buried by the hearth by the midwife, cementing her life at home. At this time, and in the next few days, the child was placed in the care (and at the whims) of the gods and dedicated to his or her future. Important stuff.

What If …?

Everything did not always go according to plan. No matter how skilled or clever the midwife, and how careful and diligent the mother, things could go awry. If the baby died in the womb, the skilled midwife dismembered and removed it with an obsidian knife, thereby saving the mother.

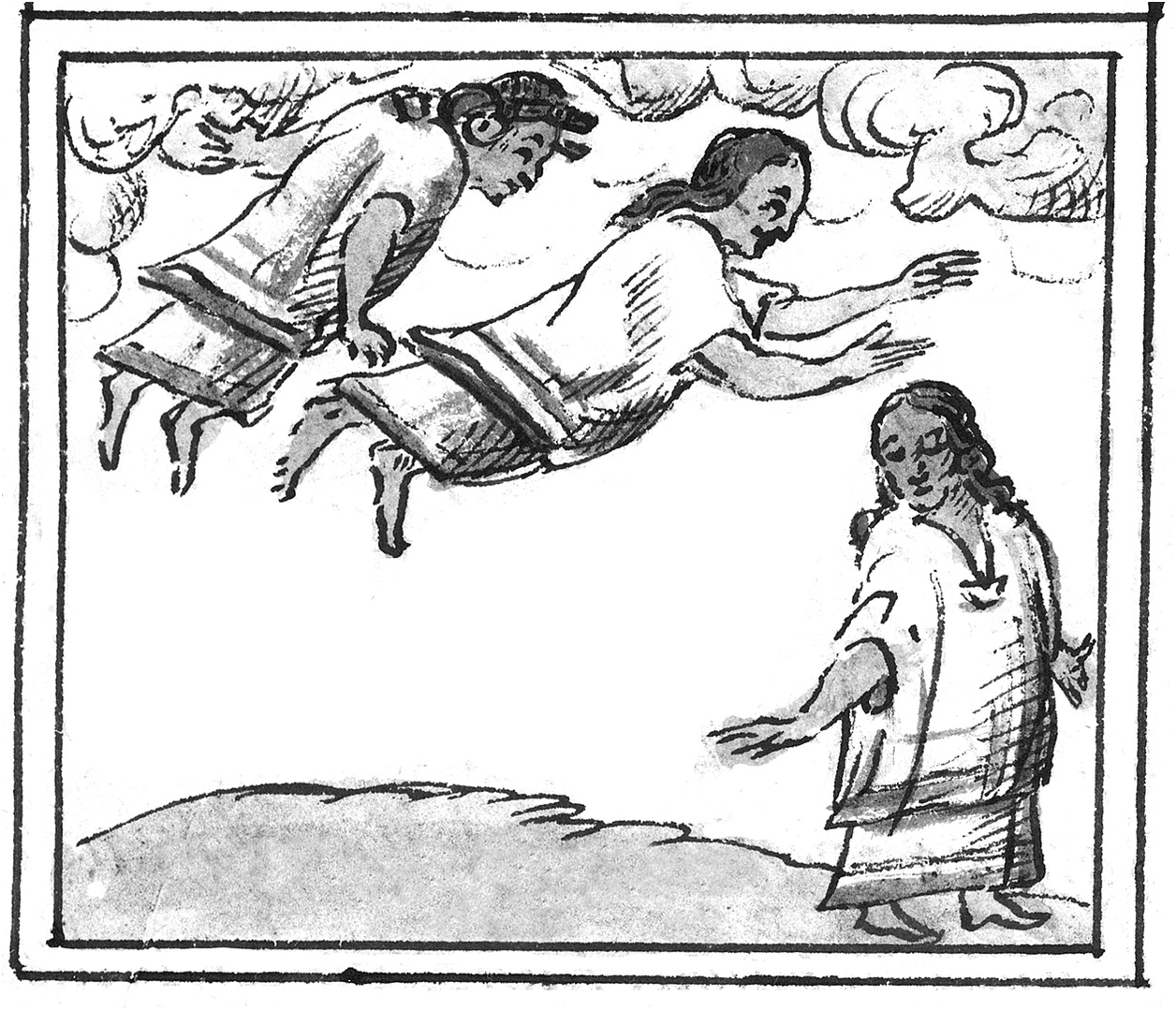

Women died in childbirth, although we do not know how frequently. These women, called mocihuaquetzque, were highly revered and honored. They had fought a fierce and exhausting battle, but lost. Like their male counterparts who died in battle or were sacrificed, these women were granted exceptional afterlives. The souls of men who died on the battlefield accompanied the sun on its journey from its rising in the east to the zenith. There, the souls of women who died in childbirth, armed as for war, took up that burden (honor, actually), carrying the sun on a litter of glorious quetzal feathers on its afternoon journey to its setting in the west. At that point, on certain days (or perhaps all of them) these rather testy women (as cihuateteo, “women goddesses”) hopped off and roamed about the earth, often causing grief to whatever humans they might encounter (Figure 7.4). A woman’s transformation into a cihuateotl “elevated the deceased woman’s spirit to godly status” (Dodds Pennock Reference Dodds Pennock, Nichols and Rodríguez-Alegría2017: 395). The days One House, One Monkey, One Rain, One Deer, and One Eagle were considered particularly ominous (Miller and Taube Reference Miller and Taube1993: 62), and on One House at least, midwives made offerings in their own homes to these goddesses. The cihuateteo were greatly feared by everyone, and a very good reason to not wander about at night.

But what about the woman herself, she who had fought such a valiant battle but lost in the end? Such a woman, in death, carried a great deal of reverence and, indeed, magical qualities. Her body was bathed and dressed in new clothing. There was great weeping at her death, but also rejoicing that she would be with the sun. Her husband carried her on his back to her burial place; it is worth noting that she was buried, not cremated (Sullivan Reference Sullivan and Sullivan1966: 87–89). Midwives accompanied this emotional retinue – “They bore their shields; they went shouting, howling, yelling. It is said they went crying, they gave war cries” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 161). Along the way they skirmished with youths who tried to seize the deceased woman. While this might appear as a mock battle, Sahagún’s informants insist that they fought in earnest. This behavior is grounded in Aztec beliefs, for if a warrior could cut off a finger or a lock of hair from a woman who died in childbirth, he would insert these relics in his shield: it was believed that these relics “furnished spirit; it was said they paralyzed the feet of their foes” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 6: 162). Such a belief would have emboldened the warrior in deadly hand-to-hand encounters on the battlefield.

Not just warriors, but also thieves greatly desired to get ahold of the mocihuaquetzqui. Their target was the woman’s left forearm, which they believed embodied the magical ability to stun and incapacitate people. Thieves (notably those born on the day One Wind) would carry this appendage with them on their nefarious outings, banging it on a house’s courtyard, doorway, lintel, and hearth, thereby stupefying the householders into a deep sleep and deftly relieving them of all their belongings (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 4: 101–102). It is easy to see why the mocihuaquetzqui was diligently protected from theft by family and midwives, before and after burial, for four nights (perhaps the efficacy of her body parts waned after that time). Clearly the midwife’s duties continued even if the mother died in childbirth. Her obligations also extended with successful births, notably with bathing and naming ceremonies.

The Bathing Ceremony

The midwife was responsible for ceremonially bathing the baby, calling on the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, a water deity (Figure 7.5). According to the Codex Mendoza, this ritual bathing took place four days following birth, although Durán (Reference Durán, Horcasitas and Heyden1971: 264) claims that newborn babies were washed four days in a row (current wisdom suggests delaying bathing of newborns for up to two days). Whatever the bathing habits, the most significant day, ritually, was the fourth. Early in the morning the midwife ritually cleansed the baby from any inherited badness by touching the baby’s mouth, chest, and head with water, placing it in the care of this powerful goddess. She then more comprehensively bathed the infant and swaddled it. The midwife spoke constantly through all of this; she modulated her voice from a whisper to a shout in addressing both the baby and the newly delivered mother. It must have been a captivating performance.

Figure 7.5. The goddess Chalchiuhtlicue.

The bathing ceremony required specialized objects and actors. The Codex Mendoza (Berdan and Anawalt Reference Berdan and Anawalt1992: vol. 4: f. 57r) clearly depicts and identifies the ritual props: a reed mat with a large earthen basin atop and tiny implements representing the infant’s anticipated life path. If a boy was to be bathed, he was accompanied by a wee object symbolizing his father’s profession: the Codex Mendoza illustrates tools of a carpenter, featherworker, scribe, and goldsmith, but there were certainly others. The ubiquitous shield with arrows is also present. If the baby was a girl, she was given a tiny distaff with its spindle and attached cotton, a reed basket for holding her spinning and weaving equipment, and a broom – all symbols of her lifelong work around the house. As with so many things, nobles could be quite extravagant, in this case with basins made specifically for this ceremony, while those less wealthy and fortunate merely bathed their infants in springs or streams (Durán Reference Durán, Horcasitas and Heyden1971: 264).

The principal actors in the bathing ceremony were the midwife, the baby, and young boys who were offered a meal of toasted maize with beans. Their primary duty came at the end of the ceremony, when the infant’s name was made known by the midwife: the boys ran off to shout this name, officially announcing the identity of the new little person to one and all. The parents and other relatives were apparently quiet observers to all this. But more was to come: for the next ten or twenty days they would receive visitors who would formally greet the baby, its mother, and its family. If the baby was of royal or noble lineage, it was particularly important that nobles and representatives of other rulers pay their respects and verbally recognize the continuation of a legitimate rule or noble lineage. This was accentuated in their lengthy and respectful greetings and back-and-forth formal dialogues between the visitors and the baby’s family. Gifts of fine clothing were also offered by the visitors. If the child was from a commoner family, visitors admired the child and addressed the baby and its mother, elderly relatives, and finally the baby’s father, but less elaborately since no great political relations were at stake. Gifts were less costly and consisted of food and drink, including pulque. Whether wealthy or poor household, one imagines a bit of a party (Figure 7.6).

What’s in a Name?

Preliminary to the bathing ritual, a name was determined for the infant. Ideally, the parents consulted a tonalpouhque, or reader of the book of days, the tonalamatl (Figure 7.7). This soothsayer was an expert in reading and interpreting the days of the Aztec’s divinatory calendar. The calendar consisted of 260 unique days (twenty day names multiplied by the numbers 1–13), each day embodying good, bad, and neutral qualities. Now, summoned to a house at a fairly high price – they fed him well and sent him on his way with turkeys and a load of food – the job of the soothsayer was to identify the day on which the child was born and to assess its meaning for the child’s fated future. Suppose the child was born on the day One Flint Knife. If a boy, he would be “valiant, a chieftain; he would gain honor and riches.” If a girl, she likewise would be “of merit, gifted, and deserving.”

On the other hand, suppose the child, male or female, had the misfortune to be born on the day Two Rabbit: they were destined to be hopeless drunkards (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 4: 11, 79). The day Two Deer foretold a future of cowardice and timidity to its bearer, that of One Rain carried with it a life of sorcery and misery, the days Five Monkey and One Flower anticipated an entertaining and amusing person, and so on for each of the 260 days. Technically, the child would be named for the day of its birth, good or bad, yielding names such as Yey Ehecatl (Three Wind), Macuilli Cuetzpalin (Five Lizard), or Ce Atl (One Water). But what if the day portended nothing but misfortune and sorrow? All was not lost if the baby was born on such an unfortunate day – the surrounding days might mute its potentially calamitous effect and open the door for a positive life. But even more importantly, the soothsayer could look ahead in his manual and find another, more propitious day to name the child. This new day name would foretell a more fortunate future for the child. Such was the power of the soothsayer.

Sahagún (Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 4: 113) suggests that poorer families may not have been able to afford the services of these learned specialists, and therefore saddled their children with ill-omened day names, and hence ill-fated futures. More wealthy nobles, however, had the luxury of consulting soothsayers and naming their children on auspicious days. In the very significant Aztec perception of the impact of fate, class played a part. Apparently, noble babies enjoyed exaggerated opportunities here as well as in the practicalities of inherited wealth and position.

While it appears that any person, regardless of social standing, was associated with the day of his or her birth, another name (or names) may also be given. These names might be martial, poetic, physically descriptive, or even degrading: Yaotl (War) was popular for men, Miauaxihuitl (Turquoise Maize Flower) or Tonallaxochiatl (Flowery Water of Summer) were sonorous choices for a woman, Huitzilcoatl (Hummingbird Serpent) was a fairly poetic name for a man, Tzonen (Hairy) described a man with particular physical characteristics, and Tomiquia (The Death of Us) was perhaps acquired through knowing this woman over time. A man might earn a name such as Tequani (Fierce Beast) or Ocelopan (Jaguar Banner) through his personal exploits, especially on the battlefield. It was said that the ruler Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (Our Angry Lord the Younger) was given that name since he scowled at his naming ceremony. We might surmise that Cuicatototl (Singing Bird), although fictional, acquired her name from her particularly melodious and calming voice. Some such names may have been acquired early in life, some later; whichever, it is not known how many names a person might carry simultaneously.

With its name bestowed, the infant entered the world of Aztec life, which was more than often characterized as a life of torment, of misery, of suffering; but if care was taken, the gods were honored, and fate was on your side, there could be hope for a life well lived.

Looking Back, Looking Ahead

As Chilpapalotl watched him, she also secretly worried about him. All the time. His name was Yaotl, a popular name for boys because it meant “War,” and what boy didn’t want to go to war? But she worried because she knew she had given birth to him seven years ago on the day Eight Reed. Although he had been bathed and named on a later, more auspicious day (Ten Eagle), she still couldn’t forget that Eight Reed carried with it great misery and bad fortune. Even though Ten Eagle declared him to be courageous and fearless, perhaps if he went to war he wouldn’t return. Surely he would go, for it seemed that the wars were more and more frequent. There was no escaping it. At least she also now had her little daughter Centzonxihuitl, who would stay here at home until she married. And now she was pregnant again, and only the gods knew what this little gift would be. She had lost one child to a fever, at only three months old – the gods had not willed it to live, and she hoped they would look favorably on this one. She would burn incense tonight and pray for the beneficence of the gods. There was so much to do – her husband Coyochimalli was off somewhere, in some faraway land fighting for their new king Motecuhzoma. She would burn incense for Coyochimalli tonight too. But now she must tend to her hearth, making sure that her food doesn’t stick to her cooking pot –otherwise his arrows would miss their mark.

The Aztecs viewed life as a gift from the gods, and the gods were omniscient and could be unpredictable, even capricious. Recognizing that life was tenuous, and in the hands of divine fate, people did what they could to improve their children’s life chances. The sixteenth-century Spanish judge Alonso de Zorita emphasized that “Lords, principales, and commoners alike showed much vigilance and zeal in rearing, instructing, and punishing their children” (Reference Zorita and Keen1994: 135). In painfully long (and seemingly tedious) lectures parents exhorted their children to be hard-working, honest, obedient, respectful, humble before the gods, and moderate in all things. They must be diligent and engage in careful and conscientious work. Following this advice would probably have helped keep the child out of trouble as he or she grew into adulthood. Early instruction, in both morals and practical matters, took place in the home with fathers teaching sons and mothers teaching girls (Figure 7.8), responsibilities and expectations increasing with age. Punishments likewise were meted out by parents (Figure 7.9). Instruction and enforcement were not subtle among the Aztecs.

Figure 7.8. Children receiving instruction, ages five and six.

Figure 7.9. Children being punished, ages ten and eleven. The eleven-year-olds are held over a fire of chili peppers until they cry.

Yaotl, at age seven, was becoming adept at his future work, still being instructed by his father or other adult male, and perhaps beginning out-of-home education. At the same age, Spartan boys left their homes and began military training, and noble boys in Medieval England likewise left their natal homes and were sent to work and learn in another elite household. Whether among the Aztecs or other historic cultures, age seven may have signaled a moment when boys (and possibly girls) began to take on more independent responsibilities and when expectations were more keenly enforced; it is perhaps notable that beginning at age eight, the Codex Mendoza shifts its life cycle story from learning to punishments.

At variably recorded ages (ranging from five to fifteen), at least part of the education of boys and girls was transferred to more formal and community institutions (Berdan Reference Berdan2014: 203, 307). Noble boys typically now attended a calmecac, or school run by priests – the curriculum here revolved around esoteric topics such as history, philosophy, calendrics, writing, orations, and songs as well as military training – boys exposed to this education were expected to pursue occupations especially in government or the priesthood (see Chapter 2). Other boys, commoners, received military training in a telpochcalli school, a fixture in each calpolli. Boys attending both schools were given some direct military experience, being taken to a war under the care of established warriors in a sort of internship: “they taught him well and made him see how he might take a captive” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 8: 72). Girls received less formal education, but some could be dedicated as infants to religious service at a temple where they served for a limited time later on, probably in their early teen years, then leaving the temple to marry and raise families.

Both boys and girls between the ages of twelve and fifteen attended a local cuicacalli, or “house of song,” where they learned the songs and dances needed for proper participation in the endlessly cycling religious ceremonies. While learning to dance, sing, and play musical instruments they also assimilated the myths, lore, beliefs, and philosophies embedded in these arts. This included such weighty matters as sorting out and praising the many gods; recounting creation stories of people, nature, and the very universe; and understanding the meaning and cycles of life and death. All of this training was extremely important to the successful performance of every ceremony, as these individuals participated in the perpetual round of public and household rituals throughout their lives.

Children and youths themselves frequently took center stage in public ceremonies. During one monthly ceremony, Atl Caualo, children were ritually sacrificed to the rain god Tlaloc to ensure rain, this at a time immediately preceding the highly anticipated rainy season. Children were also sacrificed during four other monthly ceremonies. And there was more: young girls played prominent roles in processions during the month of Huey Toçoztli, while small children, young boys, and youths suffered knife cuts on their arms, stomachs, and chests during Toxcatl. Children were especially featured during the final month of the year, Izcalli. At that time, small children were essentially initiated into Aztec ritual life by having their earlobes pierced and their necks stretched to stimulate their growth; they were also held over a fire and offered tiny sips of pulque in tiny drinking vessels – all the while their parents and other adults enjoyed boisterous eating, drinking, singing, and dancing (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 10: 61–65, 76, 165–166).

Responsible child care also included protecting children from diseases, illnesses, and other dangers. Infants, whether nobles or commoners, may have been breast-fed for up to four years (Zorita Reference Zorita and Keen1994: 135). Mothers, while nursing, could keep their infants healthy by avoiding eating avocados. While four years may have been an acceptable nursing tenure, there were pressures to shorten that time as it was believed that stammering and lisping in children could be avoided by early weaning. Illnesses most commonly threatening the lives of children were dysentery and diarrhea, either of which could be treated with an atole drink made with chia, or a drink with a specific herb or the bark of a “white tree” mixed with chocolate. That was said to do the trick (but we do not advise trying this at home) (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 10: 158). Some children also seem to have suffered from iron-deficiency anemia caused by intestinal parasites or dietary deficiencies (perhaps as a result of diarrhea). Malnutrition and infections also led to dental pathologies (Berdan Reference Berdan2014: 250–251; Ortiz de Montellano Reference Ortiz de Montellano, Evans and Webster2001; Roman Berrelleza Reference Román Berrelleza, Brumfiel and Feinman2008; Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982: book 10). The Aztecs countered these infirmities and maladies with a selection of natural remedies, appeals to sorcerers, and rituals appeasing the gods. Perhaps a friend or neighbor could recommend a good doctor or sorcerer. Or the ailing child’s parent could head to the marketplace and consult with a knowledgeable herbalist.