Some tokens carry specific chants connected to Roman festivals, while others carry imagery that evoke particular spectacles, processions or celebratory events. It is highly likely that some of the Roman tokens that survive were utilised within particular festivals; this chapter explores what these artefacts can reveal about the emotions and experiences of these occasions. Festival motifs may also have been placed on tokens to evoke particular emotions and memories before or after an event. Representations of objects associated with celebrations provide a rare source base for a better understanding of the paraphernalia associated with individual Roman festivities. We need to bear in mind, however, that the ‘festive’ imagery used to decorate many tokens is also found on everyday objects across the Roman world: on frescoes, mosaics, coinage, lamps and other artefacts. The imagery on these pieces is thus part of a broader cultural practice that used singular events as a basis for an iconography that evoked good fortune, abundance and a joie de vivre within daily life. The imagery of singular celebrations regularly transcended its immediate context in the Roman world to become part of the everyday lived experience. Tokens were designed within this broader cultural phenomenon.

Tokens from other regions reveal that the connection of these objects to festivals was not isolated to Italy. Several tokens from Athens seem to portray items carried in festival processions. Figure 4.1 is the first of these, a Hellenistic token that portrays a ship’s mast (stylis) on wheels being drawn by two horses. The wagon shown was likely used for a Dionysiac festival procession; although Crosby suggested the Anthesteria as a possible occasion, recent work suggests the City Dionysia is a more likely context.Footnote 1 A second Hellenistic token type shows Dionysus seated in a cart being drawn by a horse; Crosby also connects this image to a Dionysiac procession.Footnote 2 A token dated to the Roman imperial period from Athens showing the bust of Athena on a ship has been connected to the Panathenaic festival by Gkikaki; during this festival Athena’s peplos was suspended on the mast of a ship and brought to the foot of the Acropolis.Footnote 3

Figure 4.1 Pb token, Athens, 18 mm, 4.72 g, Hellenistic period. A ship’s stylis on a cart (the ‘cart of Dionysus’) being drawn by two horses right; prow above. Reference GkikakiGkikaki, 2020: cat. no. 21.

Tantalising connections between tokens and festivals can also be found elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean. Bronze tokens naming Melqart in Tyre from the second and first centuries BC carry dates that almost all correlate to the quinquennial games of Hercules in the city: one imagines they are probably connected with this festival in some way.Footnote 4 Hoover has suggested the Hellenistic lead pieces from Nabatea were also likely issued on the occasion of triumphs or religious festivals.Footnote 5 Lead tokens from Chersonesus on the Black Sea have been connected to festival distributions of grain, oil and wine, largely on the basis of their imagery.Footnote 6 The issuing of tokens by named individuals holding public office in other cities (e.g. in Ephesus and Dobrogea) means these objects have been connected to particular public events: tickets to festivals or distributions.Footnote 7

Previous scholarship on tokens in Italy has also acknowledged the role these pieces may have played in festivals.Footnote 8 Indeed, the connection of tokens from Rome and Ostia to various events (e.g. triumph, celebrations of dies imperii) has already been noted in the previous chapters. Here we delve deeper into this theme, exploring the full potential of tokens as a source to gain a better understanding of the imagery, emotions and experience of festivals. The chapter begins with a detailed discussion of two particular festival contexts: those connected to Egyptian cults (particularly Isis), and the Saturnalia held in December. This is followed by a broader discussion of what the imagery of tokens reveals about festival culture in Rome and its port town.

Egyptian Cults in Rome and Ostia

The Isidis Navigium was a festival of Isis held on the 5th March each year; the celebrations involved the launching of a votive ship to mark the beginning of the sailing season.Footnote 9 One of the most detailed texts connected to the festival is provided by Apuleius in the Metamorphoses: this fictional account is set in Corinth, and includes the dedication of the ship, a detailed description of the festival procession and its participants, as well as the vows made for the emperor and various sectors of the Roman population.Footnote 10

It has long been thought that a series of bronze tokens, as well as associated coin fractions, were produced in conjunction with this festival in late antiquity (Figure 4.2).Footnote 11 It is not only the late date that separates these particular tokens from those that form the focus of this volume. These late antique pieces were issued officially by the mint (not by private individuals) and are extremely similar to the official small change produced at this time. Some tokens of this category carried obverse imagery of deities, while others possessed obverses that carried portraits and legends naming Roman emperors. In the latter case, the same obverse dies used for official currency were utilised, confirming the hypothesis that these were produced at the mint of Rome.Footnote 12 In spite of the similarities to coinage, however, Ramskold’s study of the Constantinian issues noted that none of the specimens were known from hoards, suggesting that users of these objects understood they were not considered official money.Footnote 13 Alföldi initially thought these issues, which carry the legend VOTA PVBLICA, indicated that the Isidis Navigium had been moved to coincide with the vows taken for the wellbeing of the emperor on the 3rd January each year. But he later rethought this idea, and further evidence suggests that the festival remained in March.Footnote 14

Figure 4.2 Bronze token, 19 mm, 12 h, 2.38 g, AD 317. Laureate bust of Constantine I right, IMP CONSTANTINVS P F AVG / Isis Pharia standing on a ship left, VOTA PVBLICA. Reference RamskoldRamskold 2016: no. 33, pl. 1.

Apuleius does suggest that the festival was connected with vows for the emperor, the senate, the equestrian order and all the Roman people, as well as for the sailors and ships in the empire – this may be the VOTA PVBLICA referred to in the late antique token legends.Footnote 15 Ramskold’s study of the Constantinian tokens suggest they were issued when the emperor was in Rome, and many issues correlate with major events of Constantine’s reign: significant anniversaries (e.g. his decennalia) and the introduction of Constantine’s heirs.Footnote 16 As well as Isis on a ship, the tokens display Isis standing, as well as imagery of Anubis, Sarapis, the Nile and other Egyptian motifs.Footnote 17 Alföldi suggested these objects were distributed as small change during the festival (i.e. they were a form of sparsiones).Footnote 18 Bricault has observed that the messages communicated by these Egyptian deities correlated well with the messages associated with the Roman New Year: health, peace, nourishment, prosperity and birth.Footnote 19 The purpose of the objects remains enigmatic for now.

What is rarely realised is that many of the images found on these late antique bronze tokens are also found on the earlier lead tokens of Rome and Ostia. Several lead tokens explicitly connect Isis with ships. One token issue shows Isis (or a worshipper or priestess of Isis) on one side and a ship sailing right on the other.Footnote 20 Another shows Isis standing on a ship with the legend TI|LA on the other side; the legend suggests an issuer for this series other than the emperor (Figure 4.3).Footnote 21 It is impossible to know whether these particular tokens were used during the Isidis Navigium or not, but they provide further evidence of Isis’ connection to sea faring.Footnote 22

Figure 4.3 Pb token, 18 mm, 12 h, 3.21 g. TI|LA / Isis standing left on a ship with oars holding sistrum in raised right hand and situla in left.

A third token type perhaps refers to the votive ship of the Isidis Navigium. On one side stands a figure identified by Rostovtzeff as Anubis holding a caduceus and a long palm branch, while on the other Isis reportedly stands in a small ship woven or entwined with twigs, holding a rudder in her right hand and a sistrum in her left.Footnote 23 The token is very small (11 mm) and can no longer be found, so we are reliant on Rostovtzeff’s report and the drawing included in his catalogue. The drawing itself shows a ship with vertical lines, which may represent twigs, or may simply be an embellishment or style of the engraver. If we are to interpret these lines as twigs, however, they are suggestive of a votive offering or context.Footnote 24 The representation of Anubis is also strikingly close to the description provided by Apuleius of the priest who dressed as Anubis during the Isidis Navigium: the priest wore a black and gold Anubis mask and carried a caduceus and a green palm branch.Footnote 25 It may be that this token, and others reported by Rostovtzeff showing Anubis, may depict participants in the cult, the anubophoroi or anubiaci who wore a mask of Anubis on particular cultic occasions.

These mask-wearers are mentioned several times within ancient texts, and would have been present at numerous celebrations within Egyptian cults: in addition to the Isidis Navigium there was the Lychnapsia (a festival of lamps), the Pelusia held in honour of Isis and Harpocrates, the Serapia in honour of Sarapis and the Inventio Osiridis, which re-enacted Osiris’ mythical death and subsequent rebirth.Footnote 26 Other evidence also attests to existence of these priests throughout the Roman Empire. A priest wearing the mask of Anubis is shown in a fresco from the Iseum in Pompeii.Footnote 27 A mask-wearing priest is also probably shown on the El Djem mosaic in Tunisia as part of the imagery accompanying the month of November – a probable reference to the Isia that took place from 28 October to 3 November.Footnote 28 A three-handled jug decorated with a terracotta medallion, in all likelihood manufactured in the Rhône valley, shows a procession of Isis with the goddess being pulled by worshippers with a priest wearing the mask of Anubis standing towards the front of the procession (Figure 4.15 below).Footnote 29 A clay mask of Anubis, complete with slits for shoulders and eye-holes, has been found in Egypt, dating to between the 26th and 30th dynasties (the sixth–fourth centuries BC).Footnote 30 An epitaph for one Lepidus Rufus from Vienna reveals that he was an anubophorus or ‘Anubis carrier’.Footnote 31

Several lead tokens from Rome and Ostia carry the representation of a male figure with the dog-shaped head of Anubis holding a caduceus and long palm branch (Figure 4.4).Footnote 32 An Anubis figure also appears on the vota publica tokens of late antiquity; Ramskold argues that when Anubis appears on these pieces in military dress holding a branch, the god himself is represented, while the presence of a palm branch and drapery indicates the depiction of an anubophorus.Footnote 33 By this reasoning, the Anubis shown on the earlier lead tokens is the depiction of a priest, since the figure always appears with a long palm branch. But there did not seem to be such a distinctive iconographic division between Anubis and the anubophoroi in the earlier Roman period: representations of what is believed to be Anubis himself on various media show the god holding a long palm branch.Footnote 34 Thus the representations on the tokens remain ambiguous: the figure may be the god Anubis, or a priest wearing the mask of Anubis during a particular festival.

Figure 4.4 Pb token, 19 mm, 12 h, 3.05 g. Anubis (or priest of Anubis) draped from the waist down, holding branch in left hand and caduceus in right / Isis (or priestess of Isis) standing right holding sistrum in upraised left hand and situla in right, ACICI along on the left.

The users of these pieces may have known what particular representation was intended. But perhaps not: the ambiguity here between the priest and the god would have been similar to the experience of a cultic procession. In Apuleius’ procession of the Isidis Navigium the anubophorus is described as the god himself ‘deigning to walk with human feet’.Footnote 35 Indeed, Apuleius details how participants in the festival dressed up in costume: as a soldier, a gladiator, a woman and even a bear dressed as a Roman matron.Footnote 36 Of course, there is literary purpose here: this particular occasion, where people could transform into someone or something else via clothing, becomes the perfect backdrop for the physical transformation of Lucius, the main character of Apuleius’ tale, from an ass back into a human being and worshipper of Isis. This slippage between worshipper and the divine is also found elsewhere in Isiac cult. Inscriptions within sanctuaries carry first person references to the goddess (‘I am Isis’); the reading aloud of such texts by priests (perhaps dressed as Isis) or initiates would have served to blur the boundaries between the cult participant and the deity being worshipped.Footnote 37 A shared ceremony would have resulted in a shared emotional experience that served to bond the cultic community together; Apuleius’ text also captures such emotions.Footnote 38

The tokens with Egyptian motifs may thus have served to capture and evoke the sense of transformation that occurred during the Isidis Navigium and other Egyptian festivals. Indeed, just as the case for the anubophoroi, the figure on the other side of these tokens may be the goddess Isis or a worshipper of Isis. Both the goddess and her worshippers carried a sistrum and situla (sacred bucket).Footnote 39 The funerary altar of Cantinea Procla found on the via Ostiense in Rome, for example, shows her as a priestess of Isis, veiled and holding what was probably a sistrum in her raised hand and a situla at her side, just as on Figure 4.4.Footnote 40 The statue of Isis found at Hadrian’s villa shows the goddess with the exact same attributes, held in the same way: the sistrum in a raised hand, the situla at her side.Footnote 41 Coins of Claudius Gothicus invoking the wellbeing of the emperor (an interesting forerunner of the late antique tokens) also show Isis holding a sistrum and situla, accompanied by the legends SALVS AVG or CONSER AVG.Footnote 42 Thus the cults of both Anubis and Isis encompassed a slippage between the iconography associated with the god and the iconography associated with the worshipper; a slippage also found in the experience of the cult itself. The imagery selected for the lead tokens may therefore have been intentionally ambiguous, capturing the idea that a worshipper might appear as a deity. Like the tokens from Nemi discussed in the Chapter 3, the imagery perhaps allowed participants in a cult to identify themselves in the image: both male and female participants in this particular instance.

Particular paraphernalia connected to Egyptian cults are also shown on lead tokens. Figure 4.5 appears to show the physical mask of Anubis worn by the anubophoroi; the sistrum carried by worshippers of Isis is shown on the other side. Rostovtzeff believed Figure 4.6 was connected to the Isidis Navigium, noting that Apuleius reported among the attributes of the gods carried in the procession was a ‘deformed left hand with palm extended’, which was a symbol of justice.Footnote 43 There is not any reason to connect the representation of a left hand with the cult of Isis, however. As with Figure 3.8, the hand may symbolise something else, for example a particular numeral.

Figure 4.5 Pb token, 18 mm. Mask of Anubis right / Sistrum on left, next to patera on right.

Figure 4.6 Pb token, 18 mm, 12 h, 2.14 g. Cat (?) crouching right / Left hand, ABR (retrograde) around.

The imagery selected from the broader repertoire of Egyptian cults for use on tokens in Rome and Ostia is surely significant: the iconography is predominantly associated with festival processions or worshippers. Several representations of Isis found on Roman imperial coinage are absent on tokens: the goddess holding a sistrum and sceptre seated on a dog leaping right (the image most closely connected with the temple of Isis in Rome), for example, and Isis suckling Horus (connected with the fecundity of the empresses on coinage).Footnote 44 This may be because the tokens were utilised within a particular cultic community (or communities); imagery was chosen to reflect the experiences of the members rather than broader ideology. It is also worth mentioning that the imagery chosen for these tokens also differs significantly from the imagery on tokens within the province of Egypt itself: here deities of local and regional significance dominate, with the river god Nilus particularly popular.Footnote 45

Sarapis also appears on tokens in Rome and Ostia, almost always in the form of a bearded head wearing a modius.Footnote 46 Figure 4.7 shows one such example; the type was catalogued by Rostovtzeff and Prou in their publication of the tokens of the BnF, but it was then overlooked in TURS. On this specimen the head of Sarapis is combined with the representation of a river deity reclining on an urn holding a long reed: the representation may be of the Tiber, or perhaps the Nile.

Figure 4.7 Pb token, 17 mm, 12 h, 3.64 g. Head of Sarapis wearing modius right / River deity reclining left, leaning on urn from which water flows with left arm and holding long reed in right.

Harpocrates also appears on lead tokens, as do Osiris, Jupiter Ammon and other Egyptian imagery including an ibis, an Egyptian-style headdress, a baboon and the eagle form of the god Horus.Footnote 47 One of the more peculiar representations is reproduced here as Figure 4.8. This token shows Isis or a worshipper of Isis on one side and on the other side two figures on a rectangular object. What scene the image is meant to capture remains unknown. Egyptian imagery is also paired with other iconography: Mercury, for example, Fortuna, or a dolphin.Footnote 48 Each occurrence of Egyptian iconography thus cannot necessarily be connected to a particular Egyptian cult or festival; Sarapis, for instance, might have been used on tokens for other contexts.

Figure 4.8 Pb token, 17 mm, 12 h, 3.25 g. Isis or worshipper of Isis standing left holding sistrum in raised right hand and situla in left / Two figures on a rectangular object.

The findspots of tokens carrying Egyptian imagery in Rome and Ostia only provide limited information, but this does suggest these objects were used in multiple locations. A token with an image of Isis or worshipper of Isis on one side and a semi-nude figure facing right on other was uncovered in the baths of the swimmer (Terme del Nuotatore) in Ostia. The token came from a stratum associated with the levelling of sections E, F and G of the complex during the Antonine period (AD 160–180/90).Footnote 49 Several other tokens were found elsewhere in these baths, which evidently manufactured them on site (discussed in Chapter 5). Whether this particular token was manufactured for use in the baths, or was lost by an owner whilst in the complex, cannot be known.Footnote 50 A token mould half, designed to produce 11 mm circular tokens showing the head of Sarapis, was uncovered in January 1915 in the area of the via di Diana in Ostia.Footnote 51 The area has no known connection with Egyptian cults; the mould, broken in the right hand corner, might have been thrown away as rubbish. The area housed shops and was close to a crossroads shrine (compitum). During the third century AD a mithraeum was located for a period of time in room 24 of the House of Diana.Footnote 52 Any of these venues, or another, might have produced tokens showing Sarapis, either in connection with a particular festival or simply because he was a popular deity.

Unfortunately the other known find locations of tokens carrying Egyptian imagery are not so precise. A further fragment of a token mould half designed to produce 20 mm tokens showing the head of Sarapis was found in Ostia, but has no further find information.Footnote 53 The assemblage of tokens now housed in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Palestrina also contains several specimens that carry Egyptian imagery (as well as some Egyptian tokens), but no find information for these are known.Footnote 54 Amongst the tokens coming from the Tiber in Rome, two contained Egyptian imagery: one with ‘head of Sarapis / Isis or worshipper of Isis’ (TURS 3151) and the other showing Osiris on one side and a palm branch accompanied by the legend CA N on the other (TURS 3186).Footnote 55 How tokens, coins and other artefacts ended up in the Tiber is the subject of debate, but one suggestion is that at least some of these artefacts were offered as votives.Footnote 56

The discussion of the via di Diana in Ostia reveals that it is unhelpful to try and distinguish between ‘profane’ and ‘cultic’ space in the Roman world, since shrines and places of cultic significance were located amongst domestic housing, shops and other establishments. But it is worth noting that tokens are also found in dedicated temple and sanctuary spaces. Cultic groups may have created tokens for use in particular events, for example the token series carrying the legend MAG(istri)·MINERVALES·M·N·.Footnote 57 Tokens may also have acquired a secondary use as cheap and convenient votive offerings that looked like coinage. In Roman Gaul tokens have been uncovered on numerous temple sites, and there are a handful of contexts from Roman Italy as well.Footnote 58 The tokens found in the well in the sanctuary of Hercules at Alba Fucens have already been discussed in Chapter 2.Footnote 59 A token mould half was found during excavations of the ‘Syrian sanctuary’ on the Janiculum in Rome: the mould produced tokens showing two nude pankratiasts with raised fists, an amphora between them and leaves blossoming around them.Footnote 60 A further mould half, which produced circular tokens possibly showing an altar, was found in the area of the Sabazeum in Ostia.Footnote 61 Unfortunately finer contextual detail is lacking from these early finds, but they do suggest some cultic groups may have manufactured tokens.

One can imagine that the lead tokens with imagery pertaining to Egyptian cults and festivals were used within a variety of contexts. Like the imagery connected to the pompa circensis discussed in Chapter 2, particular token types bore imagery that evoked particular processions. In the case of the references to Anubis and Isis, the imagery created a slippage between the gods and their worshippers that was also part of the cultic experience. Other tokens with Egyptian imagery may have been used within more quotidian contexts. Regardless of the particular use context, the designs on these tokens would have evoked particular Egyptian cults, shaping experience and memory, and forming part of the religious backdrop to daily life.

The Saturnalia

Several tokens carry a clear connection with the Saturnalia, held each year in late December in honour of Saturn.Footnote 62 The festival inverted or suspended many Roman social norms. Masters served their slaves, gifts were given and households participated in feasting that might last several days. Gambling was allowed, and individuals participated in drinking and games, as well as (according to our surviving literature) learned discussions.Footnote 63 Catullus described it as the ‘best of days’.Footnote 64 Of course, the inversion of social customs in this way would have worked to cement and reinforce those same norms and social hierarchies.Footnote 65

Several lead tokens from Rome and Ostia carry an abbreviated form of the chant io Saturnalia!Footnote 66 One group carries the legend IO SAT IO accompanied by a palm branch, with a wreath displayed on the other side.Footnote 67 Remarkably, the bottom of the palm branch ends in four different designs: a dot, a curve, a cross that Rostovtzeff interpreted as a denarius sign (![]() ) (TURS Pl. IV, 23) and a retrograde F (Figure 4.9), which Rostovtzeff suggested communicated the phrase feliciter. The very similar style of these tokens, and the consistent placement of their legend and imagery, suggest that they were probably part of a single series. The engraver of the mould may have playfully embellished the end of each palm branch, or else the slight variations might have acted as a code to represent information (e.g. particular items, gifts or benefactions). If the latter is true, then the users of this series must have had to study the imagery on the pieces extremely closely. The sense of playfulness and fun that permeated the festival is also found on the festival tokens.

) (TURS Pl. IV, 23) and a retrograde F (Figure 4.9), which Rostovtzeff suggested communicated the phrase feliciter. The very similar style of these tokens, and the consistent placement of their legend and imagery, suggest that they were probably part of a single series. The engraver of the mould may have playfully embellished the end of each palm branch, or else the slight variations might have acted as a code to represent information (e.g. particular items, gifts or benefactions). If the latter is true, then the users of this series must have had to study the imagery on the pieces extremely closely. The sense of playfulness and fun that permeated the festival is also found on the festival tokens.

Figure 4.9 Pb token, 17 mm, 12 h, 4.32 g. Palm branch ending in a retrograde F, IO on left, SAT | IO on right / Wreath.

In a poem set during the Saturnalia, Martial describes the lavish nomismata, the coins or coin-like objects.Footnote 68 The same word is used by Martial to describe objects specifically exchanged for goods in the context of a spectacle, discussed in detail in Chapter 2. We possess evidence that coins were exchanged during the Saturnalia, so nomismata may not necessarily mean ‘tokens’ in each instance: Tiberius reportedly gave Claudius aurei during one Saturnalia, and among the gifts distributed by Augustus were ‘coins (nummi) of every device, including old pieces of the kings and foreign money’.Footnote 69 Nonetheless, given the existence of tokens carrying specific reference to the Saturnalia, one imagines these may also have formed part of the broader gift giving, perhaps representing a particular gift or gifted experience.

As with the triumphal tokens carrying the chant io triumphe discussed in Chapter 2, these tokens were designed to evoke a response from their users. The tokens ‘spoke’ to their audience, encouraging them to speak in turn. The Saturnalian cry is found on several other token designs. One issue carries the veiled and bearded head of Saturn accompanied by the legend SATVR; the other side of the token is decorated with the image of a palm branch with I on the left and O on the right, all within a wreath.Footnote 70 The legend on both sides of the token comes together to read Satur(nalia) io! Two specimens of this type are known; the second is very worn on the wreath side and bears a rectangular countermark with the legend I·VE.Footnote 71 Rostovtzeff wondered whether the countermark referred to the emperor Vespasian (I(mperator) Ve(spasianus)), an idea that can only remain a hypothesis. The token was perhaps countermarked since the wreath side was worn or poorly cast; countermarking on lead tokens from Rome and Ostia is rare when compared to other areas, most notably Athens.Footnote 72 The existence of the countermark here does suggest a form of quality control or administrative process, which in turn hints at something more than play objects or joke gifts.

The chant io Saturnalia is also referenced on a token now in the British Museum: one side of the piece carries the legend IO | SA, while the other side bears the number IIII.Footnote 73 The number I is found on another Saturnalian token, this time accompanied by the legend VAL | SATVR|NALIA on the other side.Footnote 74 The VAL here may be understood as val(eas) or val(e), a message of good wishes and health given to the user in addition to whatever benefaction the token itself conferred. Other tokens carry simply the legend SAT or IO; Rostovtzeff’s connection of the latter with the Saturnalia is hypothetical, since the chant io might also be used during other occasions.Footnote 75

A final lead token type connected to the Saturnalia displays Victory on one side and four wreaths on the other (Figure 4.10).Footnote 76 The depiction of four wreaths in this manner is also known on a Republican coin issue struck to commemorate Pompey in 56 BC (Figure 4.11): the three smaller wreaths are thought to represent Pompey’s three triumphs, while the larger wreath at the top of the coin is the corona aurea.Footnote 77 One wonders if this earlier coin issue served as inspiration for the design of the token, which most probably dates from the imperial period. Republican coins did circulate well into the principate. In Trajan’s reign, for example, Republican coins seem to have been melted down at the Roman mint and also served as models for new issues of restored coins.Footnote 78 It is thus possible that this earlier coin served as inspiration for the design of the token, although the layout of the wreaths differs (it is also worth noting in this context that some ‘restorations’ of Republican coins under Trajan did not slavishly imitate each aspect of the original, but displayed some creativity).Footnote 79 Indeed, the rather orderly presentation here also recalls the representation of prize wreaths in reliefs. But the image may have been playfully adapted from the coin type.Footnote 80 During a festival that gave licence to satire, the official currency of the Roman government might have been subjected to playful comment.

Figure 4.10 Pb token, 12 mm, 12 h, 1.88 g. Victory standing right with wreath in outstretched hand and palm branch over left shoulder; SAT in field left / Four wreaths.

Figure 4.11 AR denarius, c. 19 mm, 5 h, 3.71 g. Faustus Cornelius Sulla moneyer, 56 BC. Head of Hercules right, wearing lion-skin, S C and monogram behind. Dotted border / Globe surrounded by three small wreaths and one large wreath; below on left, aplustre; below on right, corn-ear.

The message communicated by the four wreaths on Figure 4.10 is unknown; surviving material culture that can be connected to the Saturnalian festival is relatively rare and thus there is very little comparative evidence. More generally, however, we might say that wreaths are connected to festivals and sacrifice.Footnote 81 Many of the tokens carrying a direct reference to the Saturnalia carry a palm branch and wreath; we might then deduce that this imagery was associated with the festival, as it was with other celebrations in the Roman calendar. The four wreaths might have been meant to indicate the number four, but this is pure speculation.Footnote 82 Apart from the token said to be found in Aquileia (n. 75 above), the only other reported findspots for Saturnalia tokens are in Rome. In addition to the possible Saturnalian token carrying the representation of three Fortunae (discussed in Chapter 3), the other specimen was acquired by Rostovtzeff in Rome before being donated to the BnF. The token was of the IO SAT IO type with palm branch and wreath.Footnote 83 With such tiny find numbers little can be deduced from this data.

The imagery on these tokens would have contributed to the overall experience of a particular festival. Other imagery on tokens communicates a sense of fun and festivity, although the tokens themselves carry no indication of which, if any, festival they might be connected with. It is to these tokens that this work now turns – although these objects cannot be connected to a particular occasion, they nonetheless shed light on the emotions and experiences of Roman festivals, and the transformation of festival imagery into the iconography of the everyday.

Festivals, Emotions and Roman Daily Life

Many tokens from Rome and Ostia carry scenes of fun, spectacle and entertainment, themes connected to the celebration of festivals in the Roman world. Many of these images, particularly gladiatorial combat and animal fights, were also popular themes on other small-scale domestic media: terracotta figurines, lamps and glassware, for example.Footnote 84 The imagery and emotions captured in these scenes transcended any individual event; they formed an iconographic backdrop to Roman daily life. Imagery placed on tokens, then, might have been representative of a particular festival (whether city-wide or localised within a small community), or it may have been chosen to evoke a particular emotion in the user: a sense of benefaction, of fun, or of joy. Indeed, when studying tokens one cannot escape the conclusion that many of the designs were selected to make users smile. A small figure swinging from a building crane is one example of this, as is the representation of two youths on a swing or the ‘monkey-triumph’ taking place on the back of a camel (Figure 4.12).Footnote 85 The obvious satire of an official Roman ceremony here might also be found on a token (spintria) with a sexual scene in which one of the sexual participants carries a rod – this might be an allusion to, and hence satire of, a freedom ceremony.Footnote 86

Figure 4.12 Orichalcum token, 19 mm, 9 h, 4.54 g. A togate figure in a triumphal quadriga right holding a sceptre in left hand and with right hand outstretched, being crowned by a monkey who stands behind; all on a camel / XIX within dotted border within wreath.

Satire, of course, was a feature of some Roman festivals, particularly the Saturnalia, as was gambling. Gambling was popular in the Roman world, although it was frequently regulated and confined only to particular festival days.Footnote 87 The calendar of AD 354 illustrated December with a figure throwing dice, a reference to the Saturnalia, when such activity was allowed.Footnote 88 Several tokens refer to games and/or gambling, which no doubt served to evoke anticipation or remembrance of a particular moment of leisure time. Figure 4.13 is one such example. It shows four knucklebones (astragali) used in games of chance on the reverse, accompanied by the legend qui ludit arram det quod satis sit, a statement that invites those who would play in the game to place a sufficient arra or pledge.Footnote 89 The phrase det, quod satis sit, is known from legal contexts and testimonies.Footnote 90 Arra (or arrha) is connected to the Greek arrhabṓn (ἀρραβών), which communicated the idea of a pledge or earnest money, deposited by the purchaser and then forfeited if the transaction was not completed. The term is discussed by Gellius in Attic Nights: he describes the pledge (arrabo) the Romans had given to the Samnites (here referring to 600 hostages), before going on to note that ‘nowadays arrabo is beginning to be numbered among vulgar words, and arra seems even more so, although the early writers often used arra, and Laberius has it several times’.Footnote 91

Figure 4.13 AE token, 25 mm, 7 h, 8.64 g. Female bust right, with hair tied in a bun behind her head. C on left side, S on right. Dotted border / Four knucklebones, two on top of the other. QVI LVDIT above, ARRAM | DET QVOD in the middle between the knucklebones, SATIS SIT below.

Figure 4.13 was originally published by Cohen in the nineteenth century. The same design was also reported on a lead token said to be found around Autun in France in the nineteenth century, which belonged to the collection of M. Alphonse Renaud.Footnote 92 The lead specimen is now lost to time, but the image included in the publication shows that the obverse filled the flan completely, whereas on the specimen shown here the die is much smaller than the flan. There may then truly have been a second example of the type, made of lead rather than bronze alloy. The female depicted on the obverse was interpreted by Mowat as the goddess who presides over games of chance – C(aput) S(ortis) – but this remains speculation.Footnote 93 A further lead token may also refer to knucklebones: TURS 1381 carries the legend ASTRAGALVS around in a circle on one side and a palm branch and club on the other; Rostovtzeff, however, suggested that this legend be understood as a name.

The action and excitement of gaming (and the gambling that inevitably accompanied it) is also evident on Figure 4.14, a brass token that is die linked to the so-called spintria series and associated tokens carrying the portraits of the Julio-Claudian imperial family (see Chapter 1). We might thus conclude it was made at the same workshop around the same period: the first half of the first century AD.Footnote 94 On this particular token series (which is issued with a variety of numerals on the reverse, as well as the legend AVG), two men (or boys) are shown playing a board game that appears to be ludus latrunculorum. The figure on the right has his right hand raised and is evidently shouting mora (‘wait!’).Footnote 95 The scene is reminiscent of the painting from the bar of Salvius in Pompeii where two men are depicted playing dice with their speech written above them – one declares ‘I’ve won’ while the other replies ‘Its not a three, it’s a two’. Further paintings in the bar show the quarrel escalating, with the landlord eventually throwing the two individuals out of the establishment. Clarke notes that these and other paintings in the bar demonstrate a loss of control, a world turned upside down, inviting laughter from the viewer.Footnote 96 The representation on Figure 4.14 doesn’t seem to carry the same sense of humour, and is perhaps closer in intent to the more straightforward representation of dice playing in the fresco of another bar, that on the Street of Mercury in Pompeii.Footnote 97 The frescos and the token possess imagery that invites an emotional response from the viewer, designed to evoke a particular atmosphere of fun, diversion and leisure. Depending on when the token imagery was seen, the viewer might anticipate leisure immediately ahead of them, or be prompted to reminisce about previous gaming experiences.

Figure 4.14 Orichalcum token, 21 mm, 5.04 g. Two boys or men seated facing each other, a tablet on their knees, playing a game. The figure on the right has a raised right hand. At the left a cupboard or doorway (?); MORA above / XIII within dotted border within wreath. BnF AF 17088.

Remarkably, given its popularity, dice playing does not seem to be represented on tokens. Several decades ago a lead token said to be found at Ostia was sold at auction showing two figures seated facing each other; the catalogue suggested they may have been playing a finger game (micare digitis or morra), but the token itself is too small (16 mm) to come to any firm conclusions.Footnote 98 Overall very few surviving tokens from Roman Italy reference gaming or gambling. The motif was not as popular as others; representations of deities, references to Fortuna and depictions of spectacles seem to have been far more popular choices.

The same sense of festivity might be communicated via more banal imagery, for example the wreaths and palm branches that are to be found on numerous tokens. Both the wreath and palm branch were attributes of Victory, who was connected not only to military victories, but also to victories in the circus, the theatre or other contests. Indeed, the presence of palms and wreaths on drinking vessels illustrates that the ideology of victory also entered dining and symposium contexts.Footnote 99 These images, in fact, were quite widespread – also found on Roman lamps, and even incorporated into a potter’s stamp.Footnote 100 The imagery of Roman festivals, including associated games and spectacles, was a popular decorative motif for everyday items in the Roman world. Although we may not be able to connect a particular festive token motif to a particular festival, tokens, alongside other everyday objects, served to keep the culture and spirit of festivals fresh in people’s minds.

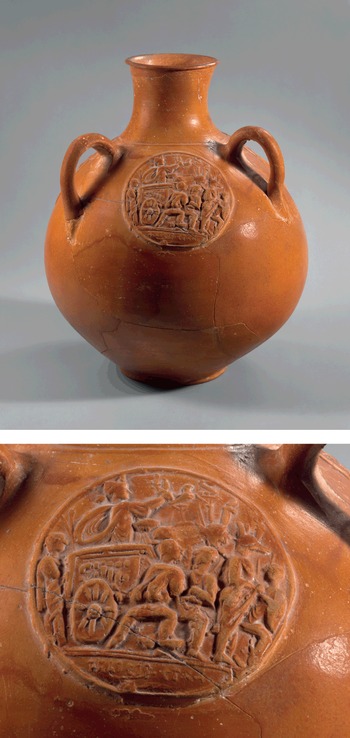

The Rhône valley beakers (terracotta vessels decorated with round medallions, largely produced in the second and third centuries AD) offer a fruitful parallel to the lead tokens of Roman Italy.Footnote 101 Like the lead tokens, the exact use context of these objects is debated; Alföldi believed that they formed New Year gifts based on a terracotta medallion showing Isis and Sarapis and resolving a fragmentary inscription as (annum novu)m lucro accipio. There is, however, little evidence to link these objects to New Year celebrations, and accepting this idea based on a restored inscription is problematic.Footnote 102 Like Roman tokens, these vases show deities, emperors and festival processions: triumphs, for example, and a procession associated with the festival of Isis. The latter shows one participant wearing the mask of Anubis, Isis in a chariot, as well as religious standards that included Horus depicted as an eagle (Figure 4.15).Footnote 103 A sense of satire is also found on these artefacts: one terracotta medallion, for example, shows the Navigium Veneris, a parody on the Navigium Isidis, that shows a nude female figure in a boat (Venus?) being penetrated from behind by a bearded, nude male figure (Mars?).Footnote 104 Although the parallels between the erotic representations on tokens and on the Rhône valley beakers has already been noted by Jabobelli, the wider iconographic parallels between the two categories of object – which both show deities, gladiatorial scenes, scenes from the circus, and carry the wish feliciter – has had little discussion.Footnote 105 Unlike tokens, however, the medallions on the beakers carry specific reference to particular dramatic performances.Footnote 106

Figure 4.15 Three-handled jug from the Rhône valley, decorated with a medallion showing an Isiac procession (also shown enlarged in the image). A medallion on the other side (not pictured) shows Atalanta and Hippomenes. Said to be from Arausio (modern Orange, Southern France), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.194.1980, public domain.

One imagines that these beakers, high quality products, would have been used for some period of time. In this way they form a compelling example of the way in which objects in the Roman world created an iconographic backdrop to daily life that frequently referenced festival culture. Importantly, the beakers were artefacts manufactured and used outside of Rome – Popkin observes that some of these items may have acted as ‘souvenirs’ for events that the owners of the artefact had never experienced (e.g. gladiatorial combat, circus racing in the Circus Maximus); in this case the artefacts enabled users to imagine themselves at various spectacles and hence feel a belonging to the Roman Empire and its culture.Footnote 107

Apart from those tokens that may have been converted into mementoes (by being pierced, for example), tokens likely remained objects of a particular moment. In this sense they differ from the Rhône beakers, but possess parallels with the objects made from the so-called ‘cake moulds’ found throughout the Roman Empire. The round moulds found along the Danube have been discussed in Chapter 2. Three-dimensional moulds have also been found in number, particularly in Ostia. The largest and best-known find is that of the Caseggiato dei Doli, a building containing some thirty-five dolia for wine and oil, as well as c. 400 terracotta moulds.Footnote 108 These moulds can be divided into roughly thirty designs, depicting scenes from the theatre, the circus (victorious charioteers), venationes, mythological scenes, erotic scenes, and scenes with sea life (e.g. fish). Nothing produced from these moulds has ever been found, suggesting that they were used to create items that were perishable and/or edible: suggestions have ranged from cakes to wax figurines, which perhaps served as a form of missilia, objects thrown to a crowd.Footnote 109 Whatever these moulds produced, they carried reference to the entertainments that accompanied religious festivals, in the theatre, circus or amphitheatre. It is thought the products of these moulds were distributed during particular festival occasions – like tokens, they would have enhanced the experience of the participant, evoking the spectacles and sights that one might anticipate seeing, or recalling an event already experienced. Like the souvenirs discussed by Popkin, if these objects were given to individuals who did not have the opportunity to experience spectacles first hand, they offered the opportunity to vicariously access this particular aspect of Roman culture. In the case of Ostia, which appears to have not had an amphitheatre or circus of its own, the moulds used in the Caseggiato dei Doli likely evoked some experiences that one had to travel to Rome for, or which took place in a temporarily erected structure.Footnote 110

These moulds, like the tokens, at times seem to have taken inspiration from coinage. A mould fragment found in the harbor at Marseille shows a ship with a spina; an intact mould with the same design is now on display at the Herakleion Archaeological Museum on Crete, and reveals that the ship has animals bounding beneath it.Footnote 111 As Salomonson observed, the design recalls the coinage of Septimius Severus showing a ship surrounded by animals and the legend LAETITIA TEMPORVM, which in turn recalls Dio’s description of a boat collapsing to release wild animals in the amphitheatre, a spectacle that likely took place as part of Severus’ saecular games.Footnote 112 The presence of moulds carrying the same imagery in geographically distant parts of the empire (and this is not the only occurrence), reveals how the celebration of a particular festival might lead to the sharing of similar imagery across the Empire: not only through imperial coinage, which circulated widely, but through the manufacture and distribution of moulds such as these by particular workshops.Footnote 113 Further work on these items needs to be performed, but they form a fruitful comparative source from which to better understand tokens and the imagery they carry.

The finds from the Caseggiato dei Doli were likely used within this building, which stored wine or olive oil; the resulting products were thus not given out in the amphitheatre or the theatre, but rather evoked these arenas and their spectacles for recipients. It is likely that a similar phenomenon occurred with lead tokens from Rome and Ostia. Although tokens have been found in the theatre in Ostia (discussed more fully in Chapter 5), one imagines that not all of the tokens carrying reference to particular spectacles were issued in conjunction with a particular event; like lamps and other everyday objects, the imagery of gladiators, animal fights and horse racing might be used in a variety of contexts. The study of this particular imagery on tokens thus remains difficult. Nonetheless, the imagery itself contributes to our understanding of Roman cultural attitudes towards the spectacles and entertainments associated with festivals, and their almost ubiquitous iconographic presence in Roman society. The images chosen on tokens and other objects shaped the perception of what these spectacles entailed, and contributed to feelings of excitement and belonging, since the use of this imagery on rather modest artefacts offered individuals the opportunity to vicariously participate in particularly Roman cultural events.Footnote 114 For token issuers, the designs of tokens offered the opportunity to present themselves to others as individuals with connection to this particular aspect of Roman culture.

The Imagery of Spectacles, Performances and Races

Roman festivals were frequently accompanied by spectacles of different types (gladiatorial or animal fights, for example, or chariot racing). Unsurprisingly given the popularity of these motifs in Roman material culture, we find imagery associated with spectacles on tokens. This includes the representation of spectators. Similar to the images of Isis and Anubis discussed above, and the tokens carrying female worshippers discussed in Chapter 3, the representation of the audience of an event allowed the user to self-identity with the image.

More specifically, the spectators shown on tokens are depicted applauding. The image perhaps evoked the sound of applause in the minds of the users, and subtly acted upon them to contribute applause in turn at a future moment in time. Indeed, if presented in advance of an event, the representation of applause promised a spectacle worthy of such a response. A series of tokens carry the image of two spectators applauding, accompanied by various legends (presumably referring to different individuals, although on one occasion the legend is the number II). The spectators are always two in number, and are consistently shown seated via the use of horizontal lines. The image is not, to the author’s knowledge, otherwise known from surviving Roman material culture, and the tokens of this type may all have been cast from moulds coming from the same workshop.

Shown on the other side of these tokens are the imagery of gladiators (Figure 4.16), an eight-horse chariot (octoiugus), a ship with a statue of Victory (?), palm branches, as well as representations of Ceres (standing holding a sceptre and corn-ears) and the head of Juno Sospita wearing a goat-skin.Footnote 115 One wonders whether the octoiugus type is part of the same series as the token carrying a representation of Nero on one side and an octoiugus on the other (TURS 31), but unfortunately the surviving specimens are not well preserved enough to judge whether they might be the products of the same workshop. The token carrying representations of spectators and a ship (perhaps a reference to a naumachia?) survives as a single specimen now preserved in the British Museum; it bears a rectangular countermark beneath the spectators that reads IMP – a reference to the emperor (who would have been one of the few individuals with the resources to stage such a spectacle).Footnote 116

Figure 4.16 Pb token, 17 mm, 12 h, 1.32 g. Two spectators applauding right / Gladiator standing left with shield in left hand and sword in right.

One imagines that the representation of spectators was intended to generate a sense of anticipation, and to serve as a prompt to audiences, much like the tokens carrying acclamations discussed in Chapter 2. The representation of the audience also highlights the importance given to the crowd in situations of this kind: these public gatherings were arenas in which the Roman population might voice its approval or disapproval of particular emperors, and this was a potential source of tension and anxiety; indeed often Roman writers focused more on the actions of spectators than the spectacles themselves.Footnote 117 The chanting and involvement of the crowd were a key characteristic of spectacles; acclamations from the audience are even recorded on mosaics that commemorate such events.Footnote 118 As Fagan has explored, spectacles formed moments in which people were placed into temporary groups and developed a particular social identity echoed by the collective vocalisations and actions; the depiction of an audience on tokens may also have served to make such temporary identities salient.Footnote 119

Participants in spectacles may also be represented on a series of tokens showing a woman with a cloth held in an arc over her head (Figure 4.17).Footnote 120 The representation is similar to velificatio (an artistic style where a deity is shown with cloth billowing around their head) but the figure on the token seems to be holding a piece of cloth entirely above their head with no material falling behind her. A variation on this type carries the legend P E C around the female figure.Footnote 121 Rostovtzeff wondered if the figure was Diana Lucifera, but the figure lacks the torch that is almost always represented with this particular form of the goddess. Indeed, a closer iconographic parallel can be found in late antiquity. On reliefs from this period (on the column of Porphyrius, the so-called ‘Kugelspiel’ now in the Bode Museum in Berlin, and the obelisk of Theodosius) we find representations of supporters of circus factions partaking in ceremonial dances; the participants are shown as figures holding a banner over their heads.Footnote 122 These dances took place at the conclusion of a race, with individuals waving banners that were the colour of the victorious team. Many (although by no means all) of these dancers, however, are men, and if the token carries a representation of such a dancer here, it is the only one known from the earlier imperial period. It is thus difficult to come to a firm conclusion, and the figure may also represent a Maenad or a different type of female dancer involved in an event. A bronze token type is decorated with three female musicians dancing; such performers contributed to the overall experience of an event and are often represented on other media as part of a scene of spectacle or entertainment.Footnote 123

Figure 4.17 Pb token, 15 mm, 12 h, 2.19 g. Woman standing left holding cloth over her head in an arch / Lion springing right.

That tokens were used during particular spectacles is evident from the specimens that specifically mention particular games or days. The best example of this is Figure 4.18, which specifically mentions dies venat(ionis), days during which animal fights would take place. Other tokens carry a specific number in connection with a day: DIE I, for example (combined with the legend SPES on the other side), or the legend DIIII, which Rostovtzeff interpreted as a reference to the fourth day (d(ies) quartus) (Apollo is shown on the other side).Footnote 124 One imagines that tokens like these were used on one particular day during a longer celebration. Another token type carries the image of a female figure standing between two standing male figures who both wear tunics; the other side of the token carries the phrase LVD and a palm branch, a reference to ludi.Footnote 125 The identification of the three figures standing facing right is uncertain – the type might reference the public procession that took place before the games, which is referenced on other token types (see the discussion in Chapter 2).

Figure 4.18 Pb token, 16 mm, 2.46 g (die axis not provided). DIES VENAT around / palm branch.

The spectacles themselves are also shown on tokens, although the imagery of animal fights, gladiators and chariot racing was so popular in the Roman world we cannot know if these representations refer to specific events. References to venationes occurred via the representation of animals, frequently with a single animal shown on one side of a token, at times accompanied by a second animal on the other side, as on Figure 2.13. A bestiarius, an individual who fought animals in the arena, might also appear on one side of a token with an animal on the other; bestiarii are also very occasionally shown in the act of attacking an animal.Footnote 126 Different types of gladiator are also depicted, either alone or in combat.Footnote 127 On one type a gladiator carrying a clipeus (oblong shield) and a gladius (sword), possibly a Murmillo, stands on one side; on the other side of the token we find a helmeted Thraex (?) wearing greaves and carrying a small shield and curved sword. The legend reads CVR on one side and M on the other, which Rostovtzeff resolved as cur(ator) m(uneris), a reference to an individual responsible for organising gladiatorial games.Footnote 128 Animal hunts were traditionally held in the morning, followed by executions at noon, and gladiatorial combats in the afternoon.Footnote 129 This programme of events, with different spectacles taking place throughout the day, is suggested by TURS 576, which shows two gladiators in combat on one side and an uncertain animal, poorly carved in the mould, on the other.Footnote 130 The two images combine to suggest a full day’s entertainment.

Rostovtzeff believed this category of tokens constituted tickets to the spectacles shown.Footnote 131 But these pieces largely lack any information about dates or seating arrangements, so it is more likely they were used during a festival for distributions, or in another context.Footnote 132 Only three tokens featuring gladiators have recorded findspots, and these are all from the Tiber in the nineteenth century.Footnote 133 This is also the only recorded findspot to date of tokens carrying imagery of bestiarii.Footnote 134 The numbers are very small, but the absence of imagery of gladiators or bestiarii on tokens found in Ostia may be telling: as mentioned above, those living in Ostia may have had to travel to Rome for more extravagant displays.Footnote 135 Tokens showing animals, however, have been found in Ostia, although we cannot know if they were issued in the context of an animal fight. A token showing a lion walking right was found during excavations of a sewer that ran towards the Tiber (the other side of the token was illegible), and another specimen decorated with the image of a bull on one side and elephant on the other (TURS 623) was found near the theatre during cleaning works.Footnote 136 A token showing a horse with a rider (with CCC on the other side) was also found in Ostia along the via di Diana; the piece was later moved to the Museo Nazionale in Rome and now cannot be found.Footnote 137 Rostovtzeff and Vaglieri also reported a token decorated with a rhinoceros standing right on one side and modius on the other as found in Ostia, but no further information is known.Footnote 138 In time, specimens showing gladiators or bestiarii may eventually come to light in Ostia.

Scenes from the circus also feature on tokens, with many images similar to that found on Roman lamps.Footnote 139 The representation of the pompa circensis, the procession that took place before spectacles in the circus, has already been discussed in Chapter 2. Tokens also carry imagery of quadrigae and bigae driven by charioteers or Victory, as well as representations of victorious horses and charioteers (Figure 4.19).Footnote 140 One lead token carries the image of a desultor on one side and a charioteer in a biga on the other.Footnote 141 A charioteer in a biga also appears on tokens of bronze alloy.Footnote 142 Several tokens may name particular horses: a legend reading EYC, for example, has been interpreted as the name Eustolos or ‘Ready’; a horse is shown standing accompanied by a palm branch on the other side of the token. SACRATVS (‘Holy’) also appears on a token accompanied by the representation of a horse, as does RUSTIVC(us) (‘Peasant’).Footnote 143

Figure 4.19 Pb token, 16 mm, 3.4 g, 6 h. Charioteer (auriga) standing left holding wreath in right hand and long palm branch in his left / Horse galloping right holding palm branch in its mouth.

Rostovtzeff suggested that the inclusion of particular names gave the tokens a programme style character, advertising the horses that would make an appearance. But the names of horses are also placed on other objects in the Roman world: late antique contorniates (which have numerous parallels with earlier lead tokens), for example, as well as gems and mosaics.Footnote 144 Circus races and charioteers are one of the most popular motifs in Roman art. The scenes on these tokens may have had a programmatic character, perhaps advertising forthcoming events during distributions or in other contexts.Footnote 145 But the victorious charioteer was also representative of success in life, as well as the victory of Rome and its rulers.Footnote 146 This is embodied in Figure 4.20, previously unpublished, which combines the image of a victorious horse with that of Victory inscribing a shield set upon a column, an image that repeatedly occurs on Roman coinage to communicate imperial military success. We cannot rule out the idea that the imagery of the circus may have been selected by token issuers in order to communicate success, in the same way an issuer might select a phallus, Fortuna or other imagery with positive connotations.

Figure 4.20 Pb token, 22 mm, 12 h, 7.88 g. Victory standing right inscribing shield that rests on a column / Horse standing right with palm branch in its mouth.

Several of the tokens that carry imagery associated with racing display the bust of Sol on one side. There was a temple to Sol and Luna at the Circus Maximus, and the representation of the deity on tokens no doubt reflects his strong connection to the circus and the events that took place within it.Footnote 147 More definitive references to the architecture of the circus are also found; this is unsurprising since, as Dunbabin has observed, most representations of the circus include details of circus architecture.Footnote 148 One token type represents the dolphin markers that were used to count the laps of the racers, with a lion standing beneath the structure.Footnote 149 The turning posts (metae) of the circus also appear, combined with a variety of imagery on the other side of the respective tokens: the head of a victorious charioteer, clasped hands, the legend CAL, the statue of Victory atop a column that stood in the Circus Maximus, and the obelisk that stood in the centre of the track.Footnote 150 The Victory atop a column is repeatedly shown in reliefs portraying scenes from the circus. The image is also placed on a previously unpublished quadrangular lead token now in Berlin, where the image is combined with a figure placed within a distyle temple on the other side; unfortunately the token is now too worn to discern whether the structure represents a temple from the area of the circus itself.Footnote 151 One type, illustrated only through a line drawing, appears to show the erection of an obelisk via ropes; although Rostovtzeff included this among the tokens showing imagery connected to the Circus Maximus, there is not necessarily any reason that the obelisk shown was that in the hippodrome in Rome.Footnote 152

A fragment of a token mould half that recently appeared on the market carries on it a design to produce circular tokens with the image of a chariot racer in a biga; unfortunately no find information is associated with this piece.Footnote 153 A further mould half from Rome (without more precise information) carries the image of a horse; the image may not necessarily be connected to the circus.Footnote 154 Two tokens carrying the imagery of a biga on one side and Victory on the other (TURS 726) have a provenance of Rome, as does one specimen carrying the image of the circus metae on one side and a depiction of clasped hands on the other (TURS 708).Footnote 155 A token with a charioteer in a quadriga on one side and three corn-ears on the other was found in Ostia, but is lacking detailed information.Footnote 156 The find information associated with this type of imagery is thus scanty; not much can be said beyond the observation that this type of imagery is found on tokens in both Rome and Ostia.

Tokens carrying a reference to the theatre – whether drama, comedy, pantomime or mime – appear to be far less frequent than those referencing spectacles. They do exist though: one issue carries the image of a gladiator on one side and on the other a double-facing mask consisting of the bearded head of Silenus and a satyr; the two images might have been chosen to communicate a particular event that involved both theatre and spectacle.Footnote 157 A similar message was communicated by another token, which carried a satyr/Silenus mask on one side accompanied by a legend in Greek (ΑΞΙ), with an animal of some kind (quadruped) on the other.Footnote 158 A further possible reference to the theatre might be found on a token now in the British Museum, which shows a crude facing head on one side and a male figure on the other; the facing head may have been intended to represent a mask but we cannot be certain.Footnote 159 Rostovtzeff recorded another token showing a theatre mask on one side and clasped hands on the other; the location of the token is now unknown and so the description cannot be verified.Footnote 160 Although an enormous achievement for the time, Rostovtzeff’s original catalogue does contain some errors and verification of the descriptions provided remains important. Indeed, this is illustrated by another token series recorded by Rostovtzeff as carrying the image of a comic mask on either side (TURS 563); in fact the token is decorated on one side with the image of a ring from which a flask (aryballos) and two strigils are suspended and the other side of the token displays an uncertain image (a long oval shaped object decorated with five pellets) (Figure 5.10).Footnote 161 Representations of dramatic performances in Roman material culture (e.g. on mosaics) often also include musicians and so the bronze token mentioned above carrying representations of female musicians might be relevant to the discussion here, although one imagines that the focus in a dramatic context would likely be on theatrical masks or actors.

In addition to theatrical and musical displays, Greek festivals also frequently involved athletic events.Footnote 162 Representations of athletes are difficult to spot on tokens, which often carry crude representations that are little more than ‘stick men’. Several tokens carry a male portrait wearing what might be a band or ribbon; Rostovtzeff identified these as the heads of male athletes, but this must remain only a suggestion.Footnote 163 Indeed, in some cases it is impossible to identify whether the portrait has a band or wreath, or whether the representation is of an athlete or a male youth more generally.Footnote 164 Full figure representations of athletes also remain difficult to identify: without an identifiable pose or attributes it is difficult to know whether the representation of a nude male represents an athlete, a Genius or some other heroic figure. The rounded hands of some figures do suggest boxers, however. Figure 4.21 is one such example: Victory crowns a nude male figure, whose hands seem to indicate that he is a boxer. The other side of the token shows a goddess holding a cornucopia and clasping hands with a smaller figure. The seated goddess may be raising a kneeling figure from the ground, or perhaps giving the figure something; the stark difference in the size of the figures recalls the numismatic representations of imperial alimenta given to children.Footnote 165 The combination of imagery is certainly unusual. Another token of this type was found during the works along the Tiber in the nineteenth century.Footnote 166

Figure 4.21 Pb token, 21.5 mm, 6.29 g, 12 h. Victory, standing right, crowning a nude male figure (boxer?) with a wreath, who stands right before her / Female figure seated left with cornucopia in left arm, clasping hands with a smaller figure standing before her.

Another possible boxer (a nude male with a clenched fist) appears on TURS 917, with an erect phallus shown on the other side.Footnote 167 Further victorious athletes may be shown on TURS 566–7, which show a nude male figure carrying a wreath and palm branch. TURS 579 is described as showing two figures in tunics wrestling, with a bestiarius on the other side. A palombino mould half, designed to produce six circular tokens showing two pankratiasts facing each other with raised fists, with an amphora between them and leaves blossoming around them, was found during the 1908 excavations of the ‘Syrian Sanctuary’ on the Janiculum hill in Rome.Footnote 168 Unfortunately no image of the find was provided and its current whereabouts are unknown. No known token matches this description.

There may be one further, as yet unnoticed, reference to Greek festival culture on the tokens of Rome and Ostia. Among the types recorded by Rostovtzeff were three that he described as being decorated with the image of an amphora, from which two or three ears of grain emerged (Figure 4.22).Footnote 169 The imagery is better interpreted as an amphora from which palm fronds emerge; this image is found on scenes showing prize tables from the Roman world.Footnote 170 Grain ears more normally emerge from a modius (see Figure 4.24 below); moreover, as Figure 4.22 demonstrates, the placement of the palm fronds is at each lip of the opening of the amphora, in keeping with the representation of prizes. Although some representations of prize tables referenced specific games, often this imagery was employed more generically to convey prestige, civic pride or acts of euergetism.Footnote 171 If these images are to be interpreted as an amphora with palms, the image may have been chosen as a prestige symbol to enhance a particular event or act.

Figure 4.22 Pb token, 15 mm, 2.09 g, 12 h. Amphora with two palm branches / Amphora with two palm branches.

The selection of boxers and pankratiasts for the handful of tokens referencing athletic events, with an apparent omission of other athletic activities, reflects broader iconographic preferences in the west of the Empire.Footnote 172 As with the other spectacles discussed in this section, the representation of athletes, or amphorae with palm branches, need not reference a particular festival; such images were popular motifs in bath decoration, for example, and in mosaics and paintings.Footnote 173 The depiction of a successful athlete on a token may have been intended to evoke a feeling of leisure, success or physical attainment.

While some motifs were more popular than others, the imagery of animal and gladiatorial fights, races within the circus, as well as athletic events, transcended a particular moment in time and appeared on Roman objects, floors, walls and streets. The imagery might serve to immortalise a particular benefactor’s actions (and hence status), build anticipation of future experience or connect the viewer to the broader Roman spectacle-going community. These images, however, also acquired numerous other associations connected to leisure, success and victory. The regular occurrence of festivals (it is estimated that at least 135 days of the year were dedicated to games in Rome by the second century AD) and their imagery shaped Roman daily life, providing a framework within which to create and consolidate experiences, identities and communities.Footnote 174 Tokens and their imagery contribute a further perspective to this broader picture.

Festivals, Feasts and Distributions

Large festivals and smaller events also frequently featured banquets or food distributions. As discussed above, the Saturnalia involved banqueting as part of the celebrations, and collegia also had particular festival days that involved feasting: an ordo corporatorum in Ostia, for example, held an annual banquet on 27 November, likely in connection with the birthday of Antinous.Footnote 175 The collegium of the cultores Dianae et Antinoi in Lanuvium held six banquets a year: on the birthday of the father of L. Caesennius Rufus (a patron of the association) on the 8 March, as well as on the birthdays of Rufus’ brother (20 August), his mother (12 September), Rufus’ own birthday (14 December), and on the birthday of Antinous (27 November) and of Diana (13 August). Food was provided by the annually elected magistri, who were responsible for the provision of sardines, loaves of bread, hot water and good wine. Another official (quinquennalis) of the collegium was responsible for providing members with oil in the public baths on the festival days of Antinous and Diana, as well as an amphora of good wine for the banquets.Footnote 176 Beyond these associations, magistrates or members of the elite might also provide public feasts to enhance their prestige: an inscription found at Portus and now lost recorded that one P. Lucilius Gamala sponsored a feast that was 217 triclinia in size; a feast (epulum) or a distribution of honeyed cakes and sweet wine (crustulum et mulsum) are attested in numerous other inscriptions.Footnote 177

The act of communal dining serves to strengthen social bonds and social hierarchies.Footnote 178 Most banquets in the Roman world would have been limited to invited diners, whether members of a particular magisterial or priestly group, a particular collegium, or another social grouping. ‘Invite only’ events contributed to a sense of group cohesion: those holding an invite grouped against those not invited.Footnote 179 Who was served when, and what they were served, also reinforced hierarchies: the collegium of Asclepius and Hygeia, for example, explicitly details the differing amount of food and money given to individuals of different rank.Footnote 180 The sponsor of the feast would also have had their prestige enhanced by the occasion; the public recording of such events, like the feast held by Gamala mentioned above, demonstrate that the sponsoring of acts of commensality were an integral part of a public career.

The connection between tokens, prestige, community and banquets in the Roman world is best illustrated by the tokens of Palmyra (frequently called Palmyrene tesserae). Uniquely in the Roman world, Palmyrene tokens overwhelmingly portray and name priests in the city, who are frequently represented on the tokens reclining on a kline as during a banquet. Palmyrene tokens are found in large quantity around the banqueting hall of the main temple of Bel, where they were obviously disposed of after use.Footnote 181 The legends on these tokens may carry the name of the person or group offering the banquet, the names of the deities involved, the date of the event or even the measures of food or drink to be given to each attendee. The unique focus of Palmyrene token iconography reflects Palmyrene society; as Raja has noted, priestly representations constitute 25 per cent of all male funerary representations from Palmyra – becoming a priest, and all this involved, was clearly an important symbol of status.Footnote 182 Religious banquets cemented group cohesion, but also acted as a (unofficial) celebration of the sponsor.Footnote 183

Can we find a similar role for tokens outside Palmyra? In Hellenistic Athens, tokens carrying the legend ΑΓ or ΑΓΟΡ have traditionally been connected with the agorastikon, a market tax collected by the agoranomoi from merchants; the tokens were seen as a proof of payment. More recently, however, Bubelis has pointed to the use of the word agorastikon in connection with the act of animal sacrifice: the word seems to indicate something that had to be purchased, with the resulting money funding the sacrifice; those who purchased the agorastikon had access to the sacrifice, or at the very least the feast that followed it.Footnote 184 Tokens from Tyre and Dobrogea have also been connected with possible feasts or distributions, but there is no conclusive evidence they were used in this manner.Footnote 185

In Roman Italy, tokens do not overtly refer to banquets as on the issues of Palmyra. Direct references to priesthoods, via legend or imagery, remain relatively rare. But this is unsurprising. The study of tokens across the Roman Empire reveals their extremely local nature; the issues of Roman Italy were created by different types of individuals, who used a different language of prestige, and who operated within a different tradition of token making than those in Palmyra. The evidence from Rome and Ostia in particular suggests that tokens were made by a variety of different social classes. As explored in the previous chapters of this volume, many Roman tokens appear to have been issued by those with the position of curator or magister and many seem to have preferred to have a token carry their portrait without the addition of other symbols. The specific use context of tokens in Roman Italy is rarely, if ever, spelt out in the legend.

Although Roman tokens do not show reclining banquet participants, tokens do portray an array of food and drink, which must have evoked feasting and distributions even if the tokens themselves were not actually used in these contexts. Figure 4.23, reportedly found in Rome, is one such example. Erroneously identified by Rostovtzeff as showing a rose, closer inspection of the image suggests that what is depicted is a loaf of bread seen from above, accompanied on the other side by a vessel with a handle.Footnote 186 The combined imagery evokes the idea of the distribution and/or consumption of bread and wine. Overbeck also wondered if many of the ‘rosettes’ recorded by Rostovtzeff were actually representations of bread; his discussion centred on TURS 1023, which shows a ‘rosette’ or loaf of bread on one side and a fish on the other, a combination that recalls the sardines and bread mentioned above.Footnote 187

Figure 4.23 Pb token, 23 mm, 12 h, 6.21 g. Vessel with handle / Loaf of bread seen from above.

The same idea is captured on tokens that carry variations of a cantharus and modius, or other vessels that contained grain, wine or oil. An orichalcum issue is known that contains a cantharus on one side and a modius on the other (Figure 5.15), and a lead issue is decorated with a modius on one side and a dolium on the other.Footnote 188 Other issues carry imagery of various amphorae or dolia or have more creative representations – one issue, for example, carries a modius on one side accompanied by the legend FR and a nut or olive tree flanked by corn-ears on the other.Footnote 189 A lead token, now in Berlin, displays a bunch of grapes on one side with a measurement, CONGIVS, written on the other – presumably a reference to a specific amount of wine.Footnote 190 To reiterate, these tokens need not have been used as invitations for banquets in the same way as the Palmyrene tesserae; the imagery may simply have been used to evoke leisure and abundance – the presence of several tokens carrying dolia or amphorae in the baths of the Cisiarii in Ostia demonstrate this (discussed in Chapter 3). Modii were also a popular design for Roman coinage, which may have inspired their adoption on other monetiform objects.Footnote 191

The imagery of grain, bread and wine is also associated with particular individuals on tokens in Rome and Ostia, although nowhere near as frequently as in Palmyra. Figure 4.24 is one such example, showing a portrait of an individual on one side and a modius on the other; presumably the recipients of the token would have recognised the identity of the individual and the token would have served to further heighten the connection of the benefactor with the benefaction received. Another issue carries an Antonine period portrait on one side, with two corn-ears and the legend MOD on the other, very probably a reference to a modius.Footnote 192 One issue combines the image of the modius with the legend GPRF on the other side, a reference to the Genius of the Roman people, and another issue combines a modius with the image of a rhinoceros.Footnote 193