Introduction

Personal agency has come to be seen as an important concept that encompasses the broad range of activities through which people with severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia, take an active role in making meaning of their lives (Lysaker and Leonhardt, Reference Lysaker and Leonhardt2012). While there are numerous definitions of personal agency, recently in the mental health field, it has been briefly defined as ‘what people can do on their own (p. 157)’ (Bellack and Drapalski, Reference Bellack and Drapalski2012).

Of course, ‘agency’ itself is not a new concept. There are two main tracks that reflect how the concept has developed in the fields of social science and neuroscience, respectively. In social science, for example, agency is defined as ‘what a person is free to do and achieve in pursuit of whatever goals or values he or she regards as important (p. 203)’(Sen, Reference Sen1985), or ‘an actor's or group's ability to make purposeful choices (p. 3)’ (Samman and Santos, Reference Samman and Santos2009). Studies have also suggested relevant constructs of agency, including subjective freedom and ownership of one's own life, and have identified agency as being particularly proximate to empowerment and well-being (Sen, Reference Sen1985; Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Ibrahim and Alkire, Reference Ibrahim and Alkire2007; Samman and Santos, Reference Samman and Santos2009). Interestingly, these constructs, which were initially found in studies conducted in Western countries, have also been observed in Japan (Ito and Akimoto, Reference Ito and Akimoto2015).

On the other hand, cognitive neuroscience studies have approached the consciousness of oneself as an immediate subject of experience, which is referred to as the ‘minimal self’ (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2000). Following this track, the sense of agency is defined as ‘the sense that I am the initiator or source of the action (p. 16)’ (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2000). Researchers in this field often focus on voluntary motor actions, rather than the degree of freedom or goal achievement in one's life in the community or broader society. In fact, a theoretical account of the mechanism of the sense of agency incorporates a classic model of motor control. This model proposes that the sense of agency can emerge when a prediction of sensory consequence that is implicitly produced based on an efference copy of motor commands matches the actual sensory consequence (Frith et al., Reference Frith, Blakemore and Wolpert2000). Multiple studies have presented empirical evidence supporting the possibility that an abnormal predictive process underlies the disruption of the sense of agency in individuals with schizophrenia (Blakemore et al., Reference Blakemore, Smith, Steel, Johnstone and Frith2000; Ford et al., Reference Ford, Roach, Faustman and Mathalon2007; Voss et al., Reference Voss, Moore, Hauser, Gallinat, Heinz and Haggard2010).

While the cognitive neuroscience approach offers important implications for the mechanism of a deficit in the sense of agency in serious mental illness, the social science concept of (personal) agency appears to better fit the community mental health and personal recovery contexts (Lysaker and Leonhardt, Reference Lysaker and Leonhardt2012; Ciftci et al., Reference Ciftci, Yildirim, Sahin Altun and Avsar2015). Over the past half century, an increasing number of people with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, are living in the community as a result of deinstitutionalisation (Kunitoh, Reference Kunitoh2013). At the same time, the paradigm of personal recovery, which has been driven by service users and which refers to the process whereby people achieve a meaningful life, has become a worldwide movement (Deegan, Reference Deegan1996; Davidson and Roe, Reference Davidson and Roe2007). Systematic reviews have identified the core concepts of personal recovery, which include connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning, empowerment and person-centeredness (Leamy et al., Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade2011; Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Belanger, Niles, Evans and Bauer2018; van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019). These reviews also found that personal agency in the community life of people with serious mental illness is a key factor that contributes to the individual personal recovery process (Wood and Alsawy, Reference Wood and Alsawy2018; van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019). In this way, the importance of personal agency has recently re-emerged in connection with research into the components of personal recovery (Lysaker and Leonhardt, Reference Lysaker and Leonhardt2012). Indeed, both personal agency and personal recovery require that service users have subjective views of their own lives, even though these individuals have serious mental illness that may affect the objective agency involved in controlling one's actions (Deegan, Reference Deegan1996; Davidson and Roe, Reference Davidson and Roe2007; Leamy et al., Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade2011; Ellison et al., Reference Ellison, Belanger, Niles, Evans and Bauer2018; Wood and Alsawy, Reference Wood and Alsawy2018; van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019). In addition, subjective personal agency appears to be related to subjective ownership, where service users feel empowered and believe that they can recover (Wood and Alsawy, Reference Wood and Alsawy2018).

Given that personal agency is recognised as a factor that facilitates personal recovery (van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019), measuring agency is useful for both research and clinical practice. However, few tools have been developed to directly assess subjective personal agency in people with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia (Tapal et al., Reference Tapal, Oren, Dar and Eitam2017). In addition, existing scales for empowerment, which is conceptually related to personal agency, may not have been developed in collaboration with people with serious mental illness; these scales also often have a large number of response items, which can be a barrier to completion for the target population (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, Saidi and Priebe2007; Barr et al., Reference Barr, Scholl, Bravo, Faber, Elwyn and McAllister2015). These are major issues in the context of developing a patient-reported measure, given that service user involvement in research and the clinical usefulness of a brief scale have been internationally emphasised (Reininghaus and Priebe, Reference Reininghaus and Priebe2012; Staniszewska et al., Reference Staniszewska, Haywood, Brett and Tutton2012; Wykes, Reference Wykes2014; Wiering et al., Reference Wiering, de Boer and Delnoij2017). The present study therefore aimed to develop a new, brief, patient-reported measure of subjective personal agency, based on service users' views and through collaboration with people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Overall design

This study was conducted in two stages. The first stage consisted of focus group interviews with people with schizophrenia, in order to create initial scale items. The second stage was a cross-sectional survey of assertive community treatment (ACT) service users with schizophrenia to test the scale's psychometric properties.

Stage 1: focus group interviews and item development process

To create initial scale items, we conducted two 2 h focus group interviews. One group comprised six people with schizophrenia living in the community, while the other consisted of five people with schizophrenia working as peer-support workers. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (no. A2016-066). Participants were recruited from across Japan via the e-mail newsletter of a non-profit organisation, the Community Mental Health & Welfare Bonding Organization, which connects service users, service providers and researchers in collaborative facilities and recovery-oriented services, and develops user-led events. Each focus group interview featured group facilitators who were other peer-support workers with schizophrenia. Prior to the interviews, we developed an interview guide, which contained the time schedule/flow of the interviews, the aims of the study, a very brief definition of personal agency and a list of interview questions.

In the focus group interviews, we briefly explained personal recovery and personal agency, and asked when and how participants experienced subjective personal agency in their daily lives based on the interview guide. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Four authors (SY, AM, US, AT) qualitatively analysed interview data via the qualitative descriptive method (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2014). In the initial coding process, at least two authors independently extracted tentative codes from the transcribed interview data. After initial coding, the four authors jointly analysed and thoroughly discussed subcategory development, resulting in the classification of similar codes into 11 subcategories. This inductive coding was conducted over several iterations. Finally, the 11 subcategories were classified into five key categories of personal agency (Table 1). Based on the categories that were generated by the qualitative analysis, and after considering other relevant studies (Sen, Reference Sen1985; Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Ibrahim and Alkire, Reference Ibrahim and Alkire2007; Samman and Santos, Reference Samman and Santos2009; Ito and Akimoto, Reference Ito and Akimoto2015; Tapal et al., Reference Tapal, Oren, Dar and Eitam2017; Wood and Alsawy, Reference Wood and Alsawy2018; van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019), we developed an initial seven-item version of the Subjective Personal Agency scale (SPA).

Table 1. Item development and content analysis for group interviews on subjective personal agency in people with schizophrenia

After initial item development, all focus group participants verified the content of each category, and group facilitators confirmed the category distribution and fit of the seven items, as well as whether item wording was applicable and understandable to people with schizophrenia. In addition, we asked five ACT service users and five ACT staff members which type of scale (visual analogue or Likert-type) was preferable. Based on their input and discussion among the authors and the focus group interview facilitators, we decided to employ a five-point Likert scale for SPA which uses a range of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for each item (online Supplementary Table S1). Finally, nine service users from two ACT teams checked the wording of each item. They were also able to complete the scale in <5 min. It should be noted that the English version of the scale included here is a translation of the Japanese version that was actually used in this study. The English version was developed through extensive discussion and revision by project members familiar with both languages, as well as by back-translation, and it is believed to be essentially equivalent in meaning to the Japanese version.

Stage 2: evaluating psychometric properties

Setting and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire survey with ACT teams across Japan to assess the factor structure, cross-validity, convergent validity, internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the new scale. We recruited 20 ACT teams that were registered in the Japan Assertive Community Treatment Network Association and that underwent regular fidelity assessments. A total of 18 ACT teams participated in the study (one declined to participate due to a lack of staff for research work, and another actually closed its ACT service agency). In each participating ACT team, trained staff members recruited a maximum of approximately 15 service users with schizophrenia between 1 January and 31 March 2018. Eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed with schizophrenia; (2) use of ACT services in December 2017; (3) aged 20 years or older; and (4) having the capacity to consent to participate in the study. Trained ACT staff members then visited individual service users' homes, explained the study to potential participants and obtained consent to participate. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (no. A2017-063).

Factor validity

We conducted both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to confirm the factor structure and cross-validity of the SPA. We selected the samples for EFA and CFA using random sampling with a ratio of 4:6 at the cluster level, as CFA requires a larger sample compared to EFA (DeCoster, Reference DeCoster1998), while factor analysis generally requires at least ten observations per item (Comrey and Lee, Reference Comrey and Lee1992). EFA with oblimin rotation was conducted and the number of factors was determined based on scree plots. Items were extracted when they loaded ⩾0.4 and showed significant loading on the factor. We then conducted CFA to test the fit of the model with the data, using the χ 2 statistic (CMIN), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis fit index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardised root mean squared residuals (SRMR). According to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines for systematic reviews (Prinsen et al., Reference Prinsen, Mokkink, Bouter, Alonso, Patrick, de Vet and Terwee2018), acceptable model fit values are as follows: CFI>0.95, TLI>0.95, RMSEA<0.06 or SRMR<0.08. Finally, we conducted a Monte Carlo simulation analysis with 5000 repetitions for the CFA sample to address sampling bias. The analysis computed probabilities for the number of simulated replication values for CMIN, RMSEA and SRMR that exceeded the original CFA values corresponding to each index (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). All analyses in this study were conducted using Stata version 15 and Mplus version 8.

Convergent and divergent validity

We used the Boston University Empowerment Scale (BUES) to assess convergent validity (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Chamberlin, Ellison and Crean1997). A Japanese version of the BUES exists, and its convergent validity, internal consistency and test–retest reliability have been confirmed (Hata et al., Reference Hata, Maeda, Tsujii, Asai, Akiyama and Kaneko2003). We also used the global assessment of functioning (GAF) to assess overall functioning in participants and examine divergent validity (APA, 1994). Each participant's case manager provided a GAF rating. Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed for convergent validity and divergent validity.

Reliability

Cronbach's α was calculated to determine internal consistency. Test–retest reliability was assessed using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC). For test–retest reliability, participants in two ACT teams (n = 23) completed the SPA a second time, 2 weeks after initial administration.

Results

Study participants

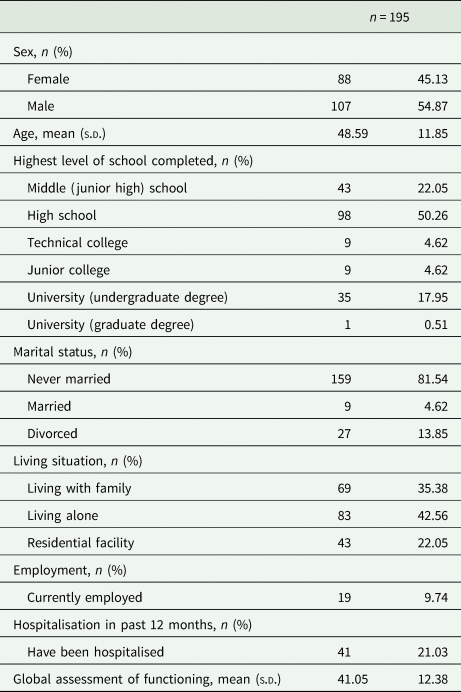

During the recruitment period, ACT staff members visited 280 eligible service users. Of these, 252 received an explanation of the study, and 197 voluntarily consented to participate. Two participants did not complete the questionnaire after initial consent, with the result that data from 195 participants were included in the analysis (online Supplementary Fig. S1). Table 2 lists the characteristics of the participants. Approximately 45% were female, and mean age was 48.59 (s.d. = 11.85). Half of the participants had graduated from high school. The mean GAF score was 41.05 (s.d. = 12.38).

Table 2. Characteristics of participants

Factor analysis

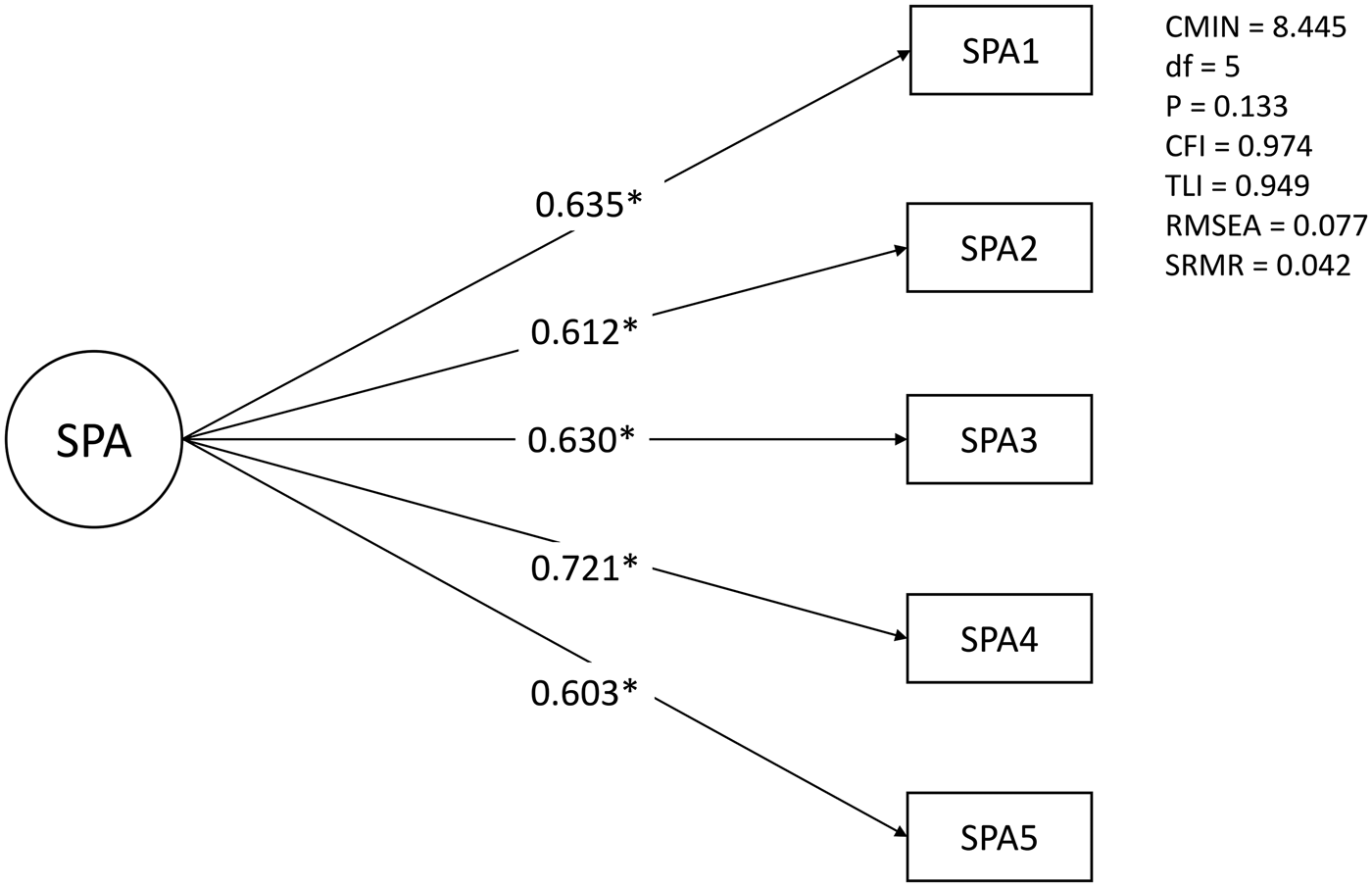

Random sampling was used to select 78 participants from eight ACT teams for EFA (Table 3). The resulting scree plot indicated a borderline two-factor v. one-factor model for the SPA (online Supplementary Fig. S2). In the two-factor model, all items loaded at more than 0.4. However, the second factor consisted of only two items (nos. 6 and 7). When a factor has only two items, a high correlation (r > 0.6) between the items is needed (Gie Yong and Pearce, Reference Gie Yong and Pearce2013). Since the correlation coefficient (r) between these items was 0.518, we rejected the two-factor model. The one-factor model also excluded items 6 and 7 due to low factor loading (<0.4), and included the five items (nos. 1–5) which achieved significant factor loading (>0.4). We used this one-factor model consisting of these five items to create the SPA-5. CFA for the SPA-5 was conducted with 117 participants from ten ACT teams. The resulting analysis was as follows: CMIN = 8.445, df = 5 (CMIN/df = 1.689), p = 0.133, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.077 and SRMR = 0.042 (Fig. 1). Monte Carlo simulation analysis indicated that the replication means for CMIN (5.148, s.d. = 3.295), RMSEA (0.028, s.d. = 0.038) and SRMR (0.027, s.d. = 0.009) were less than the original CFA values (online Supplementary Table S2). In this analysis, 10–20% of simulated replication values for CMIN exceeded the original CFA value. Less than 10% of simulated replication values for CMIN/df were under 2, and around 1% of simulated replication values for CMIN/df were <3. In addition, approximately 10% of simulated replication values for RMSEA, and only approximately 5% of simulated replication values for SRMR, exceeded the corresponding original CFA values.

Fig. 1. Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3. Results of exploratory factor analysis

Bold indicates the items with factor loadings of 0.4 or higher.

a Items #6 and #7 are reverse-scored.

Convergent validity and divergent validity

Table 4 shows the results of Pearson's correlation analysis between SPA-5 and other measures. Two participants did not complete the BUES, so the analysis was performed on data from 193 participants. SPA-5 score was significantly and positively correlated with total BUES score (r = 0.526, p < 0.001), as well as with the subscales ‘Self-esteem-self-efficacy’ (r = 0.538, p < 0.001), ‘Community activism and autonomy’ (r = 0.373, p < 0.001) and ‘Optimism and control over the future’ (r = 0.336, p < 0.001). We found a weak but significant negative correlation between the SPA-5 and the subscale ‘Righteous anger’ (r = −0.149, p = 0.038). There was no significant correlation between the SPA-5 and the BUES subscale ‘Power-powerlessness’. SPA-5 score was also not correlated with GAF score.

Table 4. Results of convergent validity and divergent validity

a Boston University Empowerment Scale.

Reliability

In terms of SPA-5 internal consistency, Cronbach's α was 0.79. In addition, ICC for test–retest reliability was 0.70.

Discussion

The present study aimed to develop a brief scale for subjective personal agency that can be completed by people with serious mental illness (online Supplementary file, the final version of the SPA-5). We created the SPA-5 through collaboration with people with schizophrenia and testing of various psychometric properties with ACT service users with schizophrenia.

The item development process and the explanatory factor analysis identified five items for the final SPA. These items appear to encompass the fundamental components of subjective agency as they relate to personal decisions, personal values and individual styles of self-expression, which have been noted in numerous previous studies (Sen, Reference Sen1985; Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Ibrahim and Alkire, Reference Ibrahim and Alkire2007; Samman and Santos, Reference Samman and Santos2009; Ito and Akimoto, Reference Ito and Akimoto2015; Tapal et al., Reference Tapal, Oren, Dar and Eitam2017; Wood and Alsawy, Reference Wood and Alsawy2018; van Weeghel et al., Reference van Weeghel, van Zelst, Boertien and Hasson-Ohayon2019). Compared to a related scale, the Sense of Agency Scale, in which items tend to focus on one's behaviours and ownership of one's actions (Tapal et al., Reference Tapal, Oren, Dar and Eitam2017), the SPA-5 has a greater focus on the service user's intrapersonal perceptions of their life. The fact that each item statement begins with ‘I’ highlights the subjective focus and nature of the scale. Such item features have been observed in other recent user-led scale development studies, such as the Recovering Quality of Life Scale (Connell et al., Reference Connell, Carlton, Grundy, Taylor Buck, Keetharuth, Ricketts, Barkham, Robotham, Rose and Brazier2018; Keetharuth et al., Reference Keetharuth, Brazier, Connell, Bjorner, Carlton, Taylor Buck, Ricketts, McKendrick, Browne, Croudace and Barkham2018).

In terms of factor analyses, the two items excluded after EFA were statements related to decision making in a context affected by the individual's health or their circumstances (including their own or others' assumptions). When measuring subjective agency, it may ultimately be suitable to ask about respondents themselves, without regard for the influence of internal or external events. The SPA-5 demonstrated good model fit through CFA (CMIN/df = 1.689, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.077), according to the COSMIN guidelines for systematic reviews (CFI>0.95, TLI>0.95, RMSEA<0.06 or SRMR<0.08) (Prinsen et al., Reference Prinsen, Mokkink, Bouter, Alonso, Patrick, de Vet and Terwee2018). Even when using more conservative criteria for CFA (good model fit: CMIN/df<2, CFI>0.97, TLI>0.97 and RMSEA<0.05; acceptable model fit: CMIN/df<3, CFI>0.95, TLI>0.95 and RMSEA<0.08) (Schermelleh-Engel et al., Reference Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger and Muller2003), the model fit values for the SPA-5 were very close to acceptable. Although the study is based on a relatively small sample, the Monte Carlo simulation analysis found that most simulated replications for CMIN/df, RMSEA and SRMR did not exceed the original CFA values or acceptable criteria values. This suggests that there is a low probability that original CFA values were produced by chance, and appears to confirm the factor validity of the SPA-5.

In terms of convergent validity, overall SPA-5 score was significantly correlated with total BUES score, as well as scores on the subscales ‘Self-esteem-self-efficacy’, ‘Community activism and autonomy’ and ‘Optimism and control over the future’, which are theoretically related to personal agency (Sen, Reference Sen1985; Alkire, Reference Alkire2005; Ibrahim and Alkire, Reference Ibrahim and Alkire2007; Samman and Santos, Reference Samman and Santos2009). At the same time, there was a significant negative correlation between SPA-5 and the subscale ‘Righteous anger’, and no significant correlation between SPA-5 and the subscale ‘Power-powerlessness’. A previous study found that the items in ‘Righteous anger’ and ‘Power-powerlessness’ did not fit well with the Japanese cultural context, in that expressing anger is usually not seen to be the same as expressing oneself (Yamada and Suzuki, Reference Yamada and Suzuki2007). In other words, our results may properly indicate convergent validity of SPA-5 in a Japanese setting, but replication studies are needed in other countries.

In addition, SPA-5 score was not significantly correlated with GAF score. Few studies have directly compared self-rated personal agency and other-rated functioning in people with schizophrenia. In terms of an association between personal recovery and daily functioning, while one meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between self-rated personal recovery scales and GAF in a sample of people with schizophrenia, the correlation was still small (r = 0.21) (Van Eck et al., Reference Van Eck, Burger, Vellinga, Schirmbeck and de Haan2018). If the results from this meta-analysis can be taken to apply to the relationship between personal agency and functioning in the context of schizophrenia, the fact that no significant correlation between these variables was found in this study may be an indication of the divergent validity of SPA-5. This study also assumed only a relatively small variance in functioning in participants. While the study targeted ACT service users, ACT service agencies generally focus primarily on service users with lower levels of functioning and more severe symptoms than individuals using other outpatient services (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jeong, Kim, Kim, Seo and Hong2015). Although one meta-analysis found a robust association between schizophrenia symptoms and subjective quality of life among outpatients who are likely to have diverse levels of symptoms (Eack and Newhill, Reference Eack and Newhill2007), this meta-analysis and the present study examined different aspects (symptoms v. overall functioning) and different outcomes (quality of life v. personal agency), and therefore direct comparison is not possible. However, it is possible to say that the characteristics of ACT service users in our sample may have had an impact on the fact that we found no significant correlation between GAF and SPA-5 scores.

The reliability of the SPA-5 was confirmed in our study. COSMIN guidelines for systematic reviews suggest the criteria of Cronbach's α of >0.70 for internal consistency, and ICC of >0.70 for test–retest reliability (Prinsen et al., Reference Prinsen, Mokkink, Bouter, Alonso, Patrick, de Vet and Terwee2018). The SPA-5 met these criteria, and appears to have an acceptable level of reliability.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that the SPA-5 was developed through collaborative work with people with schizophrenia. As co-production between researchers and service users increases value in the field of health research (Durose et al., Reference Durose, Liz and Perry2018; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Schroter, Price and Godlee2018), it is essential to involve patients in creating patient-reported outcome measures (Staniszewska et al., Reference Staniszewska, Haywood, Brett and Tutton2012; Wiering et al., Reference Wiering, de Boer and Delnoij2017). The present study included this essential step. In addition, study participants were ACT service users who experience severe symptoms and low levels of functioning in the community. The fact that the SPA-5 can be completed by people with more severe symptoms, and was validated with this population, potentially increases its applicability and usefulness.

Limitations of our study include the sample size, which was the minimum needed for factor analysis, and not relatively large. It is particularly important to note that we used a small subsample when assessing test–retest reliability. A replication study with a larger sample should be performed to confirm our results. In addition, our study did not assess participants' symptoms and cognition. Past meta-analyses have shown that general psychopathology and cognitive function are negatively associated with subjective quality of life in people with schizophrenia (Eack and Newhill, Reference Eack and Newhill2007; Tolman and Kurtz, Reference Tolman and Kurtz2012). Subjective perceptions, including subjective feelings of personal agency, may also be influenced by these variables, although our study did not find a relationship between subjective personal agency and overall functioning. A comparison between SPA-5 scores and other objective and subjective measures (e.g. symptoms, cognition and other subjective patient-reported outcome measures, such as quality of life) could produce further evidence of scale validity, and might also contribute to bridging the gap between subjective perceptions and the underlying neuroscience.

While this study has several limitations, the SPA-5 is brief and easy to answer for people with schizophrenia, resulting in a practical patient-reported outcome measure which can be used in research at multiple assessment time points (e.g., cohort study and intervention study), or studies that focus on people with severe mental illness (Yamaguchi et al., Reference Yamaguchi, Ojio, Koike, Matsunaga, Ogawa, Tachimori, Kikuchi, Kimura, Inagaki, Watanabe, Kishi, Yoshida, Hirooka, Oishi, Matsuda and Fujii2019). In addition, the variables related to subjective personal agency remain unclear in people with severe mental illness, since no validated tools for subjective personal agency in this population had previously existed. SPA-5 can therefore also be used in studies that seek to define and explain the relationships between these variables.

Conclusion

This study developed a new five-item scale to measure subjective personal agency (the SPA-5) in people with serious mental illness. Factor structure, cross-validity, convergent validity, divergent validity, internal consistency and test–retest reliability were confirmed. Further studies with larger sample sizes, as well as studies outside Japan, should be conducted to confirm these findings and to allow for comparison between the SPA-5 and other relevant objective or subjective variables.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000256.

Data

Not all the data are freely accessible because no informed consent was given by the participants for open data sharing, but we can provide the data used in this study to researchers who want to use them, following approval by the ethics committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant number. 16dk0307059h0001 to S.Y.) and the Intramural Research Grant for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders (grant number. 3-1 to C.F.). We are very grateful for the assistance and advice of the facilitators of the focus group interviews conducted when developing initial scale items. We also wish to thank Dr Akiko Kikuchi, Fumie Hisanaga and Saori Aida for assistance with English translation and back-translation of the SPA-5.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.