Introduction

For many women around the world, pregnancy marks the beginning of a journey toward motherhood. Although pleasant for many, it can trigger the onset of perinatal anxiety and depression, causing distress and disability among pregnant and postpartum women. Although both disorders are recognized as separate clinical entities, they often occur together (Waqas et al., Reference Waqas, Raza, Lodhi, Muhammad, Jamal and Rehman2015) and are referred to as common mental disorders. These disorders pose a global health concern due to their high prevalence and adverse maternal and child consequences. According to Fisher and colleagues, perinatal common mental disorders have a prevalence in low- and middle-income settings of 15.6% [95% confidence interval (CI) 15.4–15.9] during the antenatal period and 19.8% (95% CI 19.5–20.0) in the postpartum period (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran, Holton and Holmes2012). In Pakistan, the prevalence of perinatal depression is suggested to be as high as 30% prenatally and 37% during the post-partum period (Atif et al., Reference Atif, Halaki, Raynes-Greenow and Chow2021). Despite a high burden of illness, less than 20% of women report their symptoms to healthcare providers due to stigma and poor help-seeking practices inherently associated with these disorders (Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Thelen and Rosenblum2011). Untreated postpartum depression and anxiety have been shown to affect both maternal and child health (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014; Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016; Waqas et al., Reference Waqas, Elhady, Surya Dila, Kaboub, Van Trinh, Nhien, Al-Husseini, Kamel, Elshafay, Nhi, Hirayama and Huy2018). In the USA alone, these disorders accounted for a societal loss of 14.2 billion USD in 2017 (Luca et al., Reference Luca, Margiotta, Staatz, Garlow, Christensen and Zivin2020).

Among pregnant women and mothers, symptoms of anxiety and depression are often associated with a higher risk of comorbid psychiatric conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidal behaviors and increased fear of childbirth and thoughts of harming the child (Dikmen-Yildiz et al., Reference Dikmen-Yildiz, Ayers and Phillips2017). These conditions can have a profound impact on the parent–child relationship which is the foundation of the future emotional, relational, and social development of the child (Dubber et al., Reference Dubber, Reck, Müller and Gawlik2014). Untreated perinatal depression and anxiety can put the infant at a higher risk of physical and behavioral ill-health such as preterm births, poor APGAR (appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration) scores at birth, delayed growth, emotional and behavioral problems, and neurodevelopmental delay (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014; Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016; Waqas et al., Reference Waqas, Elhady, Surya Dila, Kaboub, Van Trinh, Nhien, Al-Husseini, Kamel, Elshafay, Nhi, Hirayama and Huy2018). A child born to a mother with depression and/or anxiety lacks the essential ingredients of a nurturing environment, introducing a vicious cycle of inequity, disparity, and intergenerational trauma even before the child is born (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014; Zafar et al., Reference Zafar, Sikander, Haq, Hill, Lingam, Skordis-Worrall, Hafeez, Kirkwood and Rahman2014; Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016).

Due to the multilevel impact of perinatal depression and anxiety, it is important to develop and implement carefully designed interventions for their prevention. There is abundant literature demonstrating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for the treatment of these disorders (Dennis and Hodnett, Reference Dennis and Hodnett2007; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017). Based on the same theoretical principles, prevention of postpartum depression and anxiety is possible by targeting known biological, psychological, and socioeconomic risk factors, during pregnancy or the early postpartum period (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). Previous meta-analytic evidence has shown that psychosocial interventions are effective for the prevention of mental health problems during the postpartum period (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). In their recently published evidence statement, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended that counseling interventions provide a moderate net benefit in preventing perinatal depression (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). However, there is limited or mixed evidence in existing literature regarding the effectiveness of these counseling interventions beyond cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). It is also noteworthy that most of the clinical recommendations are limited to the scope of perinatal depression, and fewer evidence synthesis efforts have focused on perinatal anxiety (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). In addition, most of the clinical guidelines do not report the implementation procedures for these psychological and psychosocial interventions. Psychosocial intervention development requires an iterative and dynamic approach, that leverages theoretical frameworks which are then implemented after accounting for feedback from key stakeholders such as pregnant women, mental health professionals, midwives, and other auxiliary services (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005; Morrell et al., Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters, Paley and Brugha2009; Kaaya et al., Reference Kaaya, Blander, Antelman, Cyprian, Emmons, Matsumoto, Chopyak, Levine and Fawzi2013). Importantly, successful interventions are tailored to the needs of the population and their social, religious, and cultural norms that sometimes precipitate depression and anxiety (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran, Holton and Holmes2012). Therefore, a realist approach is usually required while mapping these psychological interventions, to collate evidence for their effectiveness in real-world settings (Morrell et al., Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters, Paley and Brugha2009).

This mixed-methods review aims to fill previous research gaps outlined above and expands the scope of previous guidelines which have been limited to high-income countries (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Megnin-Viggars, Symington and Pilling2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). Besides exploring the meta-analytical evidence base for the preventive interventions, we aim to explore their theoretical underpinnings using distillation and matching frameworks to delineate the active ingredients (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005). We also report the implementation characteristics of these interventions and explore qualitative evidence to understand their acceptability and feasibility in real-world settings.

Research questions

We asked the following question: For perinatal women, do non-pharmacological interventions to prevent perinatal anxiety and depression, compared with active control groups/usual care, improve maternal mental health and infant outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

This review was conducted as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations for systematic reviews. Its protocol was registered at PROSPERO International Register for systematic reviews a priori (Ahmed Waqas, Reference Ahmed Waqas, Zafar, Tariq and Meraj2020). Using a predefined search strategy (Table 1) adapted from a Cochrane review (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014), we searched PubMed, Web of Science (including MEDLINE), CINAHL, Scopus, PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Global Health Library, in December 2019. This database search was further supplemented by manual searching of bibliography of eligible interventions for their evaluation and implementation studies (irrespective of study design), Cochrane reviews and US Preventive Service Taskforce guideline documents, and the clinical guidelines by The National Institute for Health and Care Excellent in the UK (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). The search process was restricted from 2013 to 2019 to include the latest evidence that complements the previous Cochrane review (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014). Studies not available in English language were excluded because of a lack of resources.

Table 1. Search strategy

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants/population

• Studies on preventative psychosocial or psychological interventions among perinatal women were considered.

• Only those studies were included that reported maternal anxiety or depression as a primary outcome.

• The populations studied were pregnant women and postpartum mothers, including those with no known risk and those identified as at-risk of developing perinatal depression (pregnant adolescents, women with prodromal symptoms of depression and anxiety, new adolescent mothers, pregnant women in humanitarian settings, single pregnant women, etc.)

• Studies that provided an intervention during the antenatal and postpartum periods were included.

• Trials where more than 20% of participants fulfilled the clinical criteria for depressive disorder at trial entry were excluded; to avoid inclusion of treatment interventions.

• Interventions conducted among perinatal women with medical comorbidities such as hypertension or gestational diabetes mellitus were excluded.

Interventions

• Studies that assessed the effectiveness of non-pharmacological (psychosocial and psychological) interventions were included. These included psycho-educational strategies, CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, non-directive counseling, supportive interactions, non-specialist mediated therapies, and group therapies.

• Multi-dimensional and multicomponent interventions involving psychotherapeutic elements were included.

Study design

• Quantitative evidence: for quantitative evidence of preventative interventions, we only considered randomized or cluster randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

• Qualitative evidence and process outcomes: any evaluation studies (irrespective of study design) of the eligible RCTs exploring our PICO questions were included to understand the implementation processes, acceptability, and feasibility of the interventions.

• Short formats of publications such as brief reports, letters to editors, conference papers, and abstracts were excluded.

Outcomes

In line with our primary aim of delineating the effectiveness of interventions in the prevention of perinatal anxiety and depressive disorders, the following primary outcomes were considered:

• Severity of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms assessed with psychometric screening scales.

• Rate of perinatal depressive and anxiety disorders according to Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) or International Criteria for Diagnoses (ICD) (World Health Organization, 1992; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

In addition, we considered several secondary outcomes to assess the effectiveness of the interventions in improving the overall biopsychosocial health of postpartum women and their children. For this purpose, the following outcomes were considered:

• Maternal physical health parameters included rates of maternal mortality and rates of short-term maternal morbidity (anemia, back pain, breast complications, fatigue/tiredness/exhaustion, sleep deprivation, and weight retention).

• Maternal psychological status assessed using validated psychometric scales for assessment of wellbeing, self-esteem, stress, intimate partner violence, suicide, and self-harm.

• Indicators of maternal functioning measured using validated psychometric scales for assessment of emotional attachment, self-efficacy, competence, autonomy, confidence, self-care, and coping skills.

• Pattern of health services use measured as readmission to hospital, length of stay, unscheduled use of health services, and need of medication.

• Infant care measured using psychometric scales for constructs including mother–child interactions and postpartum attachment.

• Post-intervention rates of exclusive and continuous breastfeeding.

• Scores on psychometric measures of daily functioning and perceived social support.

• Quality of life measured using validated scales such as the WHO Quality of Life scale.

• Child health outcomes included post-intervention rates of neonatal mortality, rates of poor health indicators such as infectious illnesses, jaundice, disability, allergy, surgery, injury, and immunization status.

• Parameters of child growth such as height, weight, and head circumference.

• Motor development, developmental milestones, speech, and language development assessed using validated scales such as the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development.

• Implementation processes: acceptability, evaluation, cost-effectiveness, and uptake assessed using qualitative interviews of intervention recipients and delivery agents.

• Cost: out-of-pocket expenditures and cost-effectiveness

Data extraction (selection and coding)

Two reviewers (SWZ, HM, SN, and MT) working independently from one another scrutinized titles and abstracts as per pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. This phase was aided by the use of Rayyan software (Ouzzani et al., Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid2016). Any differences in decisions of these two reviewers were resolved by a senior author (AW). This phase was followed by scrutinizing full texts of studies found eligible in the previous phase. The two reviewers were then trained in the data extraction procedure, where their inter-rater reliability was assessed on 10% of included studies. After establishing good inter-rater reliability, data extraction was performed for the rest of the studies against several matrices including characteristics of publications and study population: theoretical underpinnings and implementation characteristics of interventions.

Characteristics of populations included the age range of mothers and children and criteria for inclusion in trials. Publication characteristics included country and region of study and primary outcomes. Implementation characteristics of these interventions included the setting of intervention, delivery agents, methods for rating competency, and fidelity for intervention delivery. Thereafter, interventions were grouped according to their theoretical underpinnings such as CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, mindfulness, music therapy, or social support interventions. The therapeutic elements in these interventions were further scrutinized at a granular level using the framework of distillation and matching which propounds those different psychological interventions may have similarities across the range of therapeutic elements it comprises (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005), despite following a different taxonomy. Taxonomy for these elements was adapted from a previous systematic review (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017). Qualitative evaluation outcomes of interest were perspectives of patients, researchers, and stakeholders on acceptability and feasibility of these interventions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta-analysis Software (Version 3, New Jersey, USA). For quantitative outcomes, data for both the primary and secondary outcomes were recorded as post-intervention mean (s.d.) and sample size of intervention and control groups. For dichotomous outcomes, we considered the number of events and sample sizes of intervention and control conditions (Higgins, Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019). Study-wise weighted effect sizes and pooled effects sizes for all outcomes were presented as a forest plot. Data pertaining to specific outcomes were pooled using random-effects (DerSimonian and Laird method), because of expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity across the studies (Higgins, Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019). Heterogeneity was considered significant at >40%. Sensitivity analyses using the single-study knockout approach were used to assess the contribution of single studies to specific outcomes. Publication bias was assessed using Begg's funnel plot and Egger's regression statistic (significant at p < 0.10), for each outcome reported in 10 or more studies. In case of significant publication bias, the trim and fill method proposed by Duval and Tweedie was to improve the symmetry of the funnel plot, thus, adjusting the pooled effects size for publication bias. Subgroup analyses were run for theoretical orientation of psychological interventions, type of delivery agent, and type of population (general v. at risk). A series of meta-regression analyses were conducted to assess the association of dose density of therapy assessed using the number of sessions, duration of each session, and duration of the overall intervention program. Meta-regression was only run when each covariate was reported in more than 10 studies (Borenstein, Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2021). Data on the cost-effectiveness of reviewed interventions could not be meta-analyzed due to heterogeneity in reporting of outcomes across these trials.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment and quality of evidence

The risk of bias among RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane tool for risk of bias assessments (version 1) across five domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias (Higgins, Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019). The risk of bias across these domains was categorized as low, high, and unclear. These domains were classified as being unclear when methodological details provided by the authors were either missing or insufficient. Thereafter, GRADE evidence criteria were used to grade the quality of evidence for these interventions for critical outcomes. The quality of evidence was graded from very low to high based on several criteria including study design, risk of bias, indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency, publication bias, and dose–response relationship (Guyatt, Reference Guyatt, Akl, Kunz, Vist, Brozek, Norris, Falck-Ytter, Glasziou, DeBeer and Jaeschke2011).

Qualitative data synthesis

For studies reporting the acceptability and feasibility of psychosocial interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety, we adopted a narrative synthesis approach. In this phase, two reviewers working independently from one another rigorously reviewed these studies and extracted relevant quantitative or qualitative (interviews) data. One senior reviewer utilized an open-coding approach to label and categorize the quantitative and qualitative data into broad themes. The number of studies reporting broader themes was quantified and meaningful relationships and inferences were drawn from them.

Results

The database search process yielded a total of 2659 bibliographic records and 11 articles were added using the manual search method outlined above. After excluding 2098 studies during the title and abstract screening process, we included 294 studies that were further scrutinized during the full-text screening phase (Fig. 1). In the full-text screening process, we excluded 267 studies that were treatment interventions (n = 80) or other types of publications such as protocols, studies in languages other than English, and those missing full texts (n = 100). After the screening process, a total of 27 studies were included: RCTs (n = 21); studies reporting acceptability/feasibility of interventions (n = 6); and cost-effectiveness (n = 2).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart exhibiting study selection process.

Description of studies and participants

Data from a total of 21 studies were collated to inform the meta-analytic evidence for preventive interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety. Out of these 21 studies, there were 12 powered RCTs, six pilot RCTs, two quasi-experimental studies, and one cluster RCT. Only two of the trials aimed to test effectiveness of psychological interventions in a pragmatic real-world setting (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016), while the rest were conducted in research settings. Most of these trials were conducted in high-income countries including the USA (n = 8), the UK (n = 4), and one each in Spain and France, Portugal, Denmark, and Australia. Among middle-income countries, these interventions were only tested in Iran (n = 3) and China (n = 1). One of the interventions was conducted using an online platform among Spanish and English-speaking pregnant mothers residing in multiple countries (Chile, Spain, Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, and the USA) (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wickham and Muñoz2015). Only 12 of these studies had cited a priori registration of study protocols.

The mean age of intervention recipients across studies ranged from 21 to 40 years. Only one of the studies reported findings among adolescent mothers in the USA (aged 13–18 years) (Phipps et al., Reference Phipps, Raker, Ware and Zlotnick2013). Geographically, six of these trials were conducted in urban settings, online (n = 5) (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wickham and Muñoz2015; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018; Krusche et al., Reference Krusche, Dymond, Murphy and Crane2018; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019; Fonseca et al., Reference Fonseca, Monteiro, Alves, Gorayeb and Canavarro2019), multiple settings (n = 2) (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016), and rural (n = 1) (Jesse et al., Reference Jesse, Gaynes, Feldhousen, Newton, Bunch and Hollon2015). All of the interventions included in this trial were preventative; with either a universal focus (n = 10) (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Bodnar-Deren, Balbierz, Loudon, Mora, Zlotnick, Wang and Leventhal2014; Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wickham and Muñoz2015; Fathi-Ashtiani et al., Reference Fathi-Ashtiani, Ahmadi, Ghobari-Bonab, Azizi and Saheb-Alzamani2015; Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Krusche et al., Reference Krusche, Dymond, Murphy and Crane2018; Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018) or a targeted/at-risk focus (n = 11) (Zlotnick et al., Reference Zlotnick, Miller, Pearlstein, Howard and Sweeney2006; Phipps et al., Reference Phipps, Raker, Ware and Zlotnick2013; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, De Pascalis, Woolgar, Romaniuk and Murray2015; Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Bodnar-Deren, Balbierz, Loudon, Mora, Zlotnick, Wang and Leventhal2014; Ortiz Collado et al., Reference Ortiz Collado, Saez, Favrod and Hatem2014; Maimburg and Væth, Reference Maimburg and Væth2015; Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019; Fonseca et al., Reference Fonseca, Monteiro, Alves, Gorayeb and Canavarro2019). Interventions with a target focus provided prevention therapies for women on public assistance (n = 1), primiparous mothers (n = 2), and adolescent mothers (n = 1). A majority of interventions targeted postpartum depression (n = 18); three trials focused on both anxiety and depression (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Krusche et al., Reference Krusche, Dymond, Murphy and Crane2018; Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018) and one only on anxiety (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013). Detailed characteristics of the studies are presented in online Supplementary Table S1.

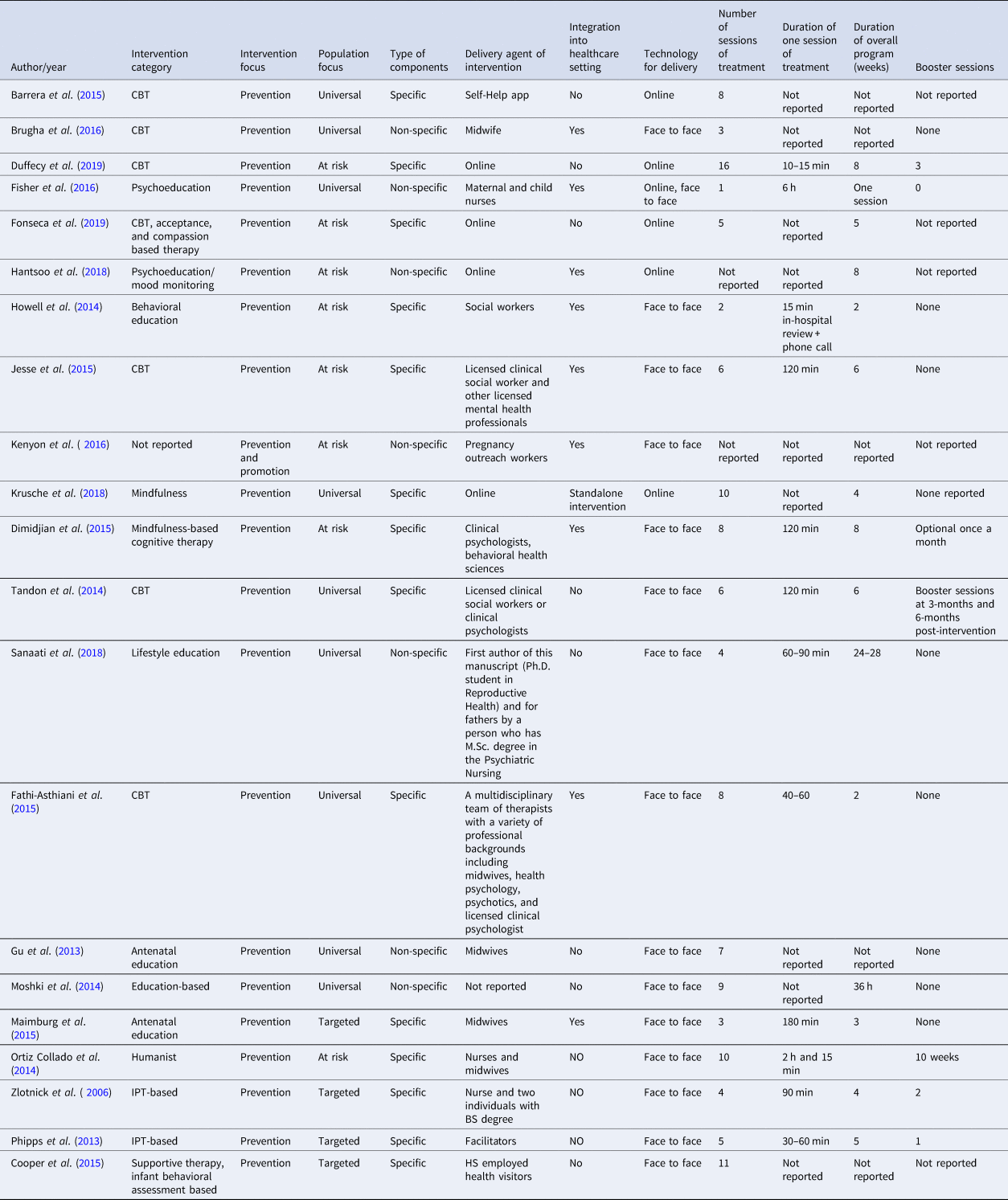

Characteristics of interventions

A total of 15 interventions comprised of elements specific to the psychological or psychosocial domain while six interventions comprised of elements commonly used as in-session techniques (Fig. 2) (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013; Moshki et al., Reference Moshki, Baloochi Beydokhti and Cheravi2014; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018; Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018). The latter group of interventions comprised primarily of psychoeducational modules; however, some of these also provided lay social support (Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016), mood tracking and alert through software (Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018), and midwives run antenatal clinical support (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013). The interventions were delivered either by mental health professionals or lay professionals. Interventions mediated by lay professionals included midwives (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013; Maimburg and Væth, Reference Maimburg and Væth2015; Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016); health visitors (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, De Pascalis, Woolgar, Romaniuk and Murray2015); facilitators (Phipps et al., Reference Phipps, Raker, Ware and Zlotnick2013); pregnancy outreach workers (Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016), and multidisciplinary teams of nurses, midwives, and graduates (Zlotnick et al., Reference Zlotnick, Miller, Pearlstein, Howard and Sweeney2006; Ortiz Collado et al., Reference Ortiz Collado, Saez, Favrod and Hatem2014). Professionals with mental health background delivering these interventions were social workers (Howell et al., Reference Howell, Bodnar-Deren, Balbierz, Loudon, Mora, Zlotnick, Wang and Leventhal2014; Jesse et al., Reference Jesse, Gaynes, Feldhousen, Newton, Bunch and Hollon2015); clinical psychologists (Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015); mental health nurses (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016); mental health researchers (Moshki et al., Reference Moshki, Baloochi Beydokhti and Cheravi2014); multidisciplinary teams of reproductive health and mental health nurses (Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018), and licensed social workers, clinical and health psychologists (Fathi-Ashtiani et al., Reference Fathi-Ashtiani, Ahmadi, Ghobari-Bonab, Azizi and Saheb-Alzamani2015). Five of the interventions were delivered through self-help apps or online media (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Wickham and Muñoz2015; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018; Krusche et al., Reference Krusche, Dymond, Murphy and Crane2018; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019; Fonseca et al., Reference Fonseca, Monteiro, Alves, Gorayeb and Canavarro2019). A total of nine interventions were integrated into healthcare settings (Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015; Howell et al., Reference Howell, Bodnar-Deren, Balbierz, Loudon, Mora, Zlotnick, Wang and Leventhal2014; Fathi-Ashtiani et al., Reference Fathi-Ashtiani, Ahmadi, Ghobari-Bonab, Azizi and Saheb-Alzamani2015; Jesse et al., Reference Jesse, Gaynes, Feldhousen, Newton, Bunch and Hollon2015; Maimburg and Væth, Reference Maimburg and Væth2015; Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018). Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in online Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Fig. 2. Non-specific elements of interventions.

Therapeutic ingredients of interventions

Based on their theoretical orientations, these interventions were described by authors as cognitive-behavioral (n = 7); psychoeducational (n = 6); mindfulness (n = 2); social support (n = 1); interpersonal psychotherapy (n = 2); and multicomponent interventions with predominant non-specific therapeutic elements (n = 3). Only a few of these interventions were formally manualized, which was a major barrier in identifying the active therapeutic elements based on the distillation and matching model (Chorpita et al., Reference Chorpita, Daleiden and Weisz2005). Using the taxonomy proposed by Singla et al. (Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017), an overlap in therapeutic elements (online Supplementary Table S2; Table 2) across different interventions was identified (Figs 3 and 2).

Fig. 3. Specific therapeutic elements of interventions.

Table 2. Delivery agent and duration of interventions

Overall, the most frequently employed non-specific elements were eliciting social support (n = 11), spousal support (n = 6), collaboration in care (n = 6), involvement of family (n = 4), case management (n = 3), normalization (n = 3), and active listening (n = 2) (online Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). The most frequently employed specific elements (online Supplementary Fig. S2) belonged to interpersonal skill categories such as training in assertiveness (n = 10) and communication skills (n = 7); identifying affect (n = 7) and assessment of relationships (n = 6) and cognitive skills such as identifying thoughts (n = 10), mood monitoring (n = 7), self-awareness (n = 6), and cognitive restructuring (n = 6). Most common behavioral therapeutic elements were relaxation (n = 6), emotional regulation (n = 6), stress management (n = 5), and self-monitoring (n = 4). Parenting skills included parent–child interaction (n = 5) and parental coping (n = 5). Psychoeducational interventions frequently focused on birth procedures (n = 8) and breastfeeding, nutrition, and sexual behaviors (each n = 3). While specific delivery techniques included assigning homework (n = 9), reviewing homework (n = 3), and goal setting (n = 3).

Meta-analysis for maternal outcomes

Forest plots presenting the effectiveness of eligible interventions for a variety of outcomes have been provided as online Supplementary Figs S1–S6.

Severity of depression symptoms

This outcome was reported in 12 studies (14 data points) among 1864 study participants, where most of the studies employed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for measurement of perinatal depressive symptoms (n = 10), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (n = 2), and other (n = 2). There was evidence for substantial heterogeneity (I 2 = 92.30%; Q = 168.83; p < 0.001). These interventions yielded moderate to strong effect size in reducing the severity of depressive symptoms [standardized mean difference (SMD) = −0.59; 95% CI −0.95 to −0.23]. There was no evidence of publication bias in reporting of this outcome on visualization of funnel plot (Egger's regression p = 0.30, online Supplementary Fig. S9). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effect sizes after the removal of individual studies from the pooled analyses.

Subgroup analyses (Table 3) revealed that general populations showed a greater reduction in severity of depressive symptoms (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI −1.29 to −0.06) followed by at-risk populations (SMD = − 0.50, 95% CI −0.89 to −0.10). These differences were statistically non-significant (Q = 0.23, p = 0.63). Interventions delivered by specialists yielded stronger effect sizes than non-specialists, online apps, or multidisciplinary teams (Q = 9.48, p = 0.02). Albeit statistically insignificant, CBT-based therapies yielded highest effect sizes (SMD = −0.86, 95% CI −1.56 to −0.17) followed by psychoeducational interventions (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI −1.41 to 0.07). No significant differences in effect sizes were observed among studies employing specific or non-specific intervention elements; or integrated/non-integrated interventions; and mode of delivery or booster dose. Complete information regarding dosage density of interventions was reported in only seven studies. Meta-regression analysis did not reveal any association of number of sessions (R 2 = 0.06, p = 0.62), their duration (R 2 = 0.06, p = 0.59), and duration of overall programs (R 2 = 0.28, p = 0.20) (online Supplementary Figs S7 and S8).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis to identify moderators of preventive interventions for perinatal depressive symptoms

Rates of depressive disorder

This was reported in six studies (seven trials), conducted among 1003 participants. A higher proportion of these studies employed the SCID-based interviews (n = 3). There was some evidence of heterogeneity in reporting of this outcome (49.90%, p = 0.08). It revealed a non-significant reduction in rates of depression among intervention recipients (R 2 = 0.86, 95% CI 0.65–1.32). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were conducted for this outcome since few studies reported it.

Severity of anxiety symptoms

This outcome was reported in only three studies conducted among 432 participants. All of these studies utilized State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. There was substantial evidence of heterogeneity in reporting of this outcome (I 2 = 92.51%, Q = 25.48, p < 0.001). Overall, these interventions were associated with a significant reduction in the severity of symptoms of anxiety (SMD = −1.43, 95% CI −2.22 to −0.65). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Rates of generalized anxiety disorder

This outcome was reported in only two studies among 499 participants, using GAD-7 and Beck Anxiety Inventory. There was significant evidence of heterogeneity (I 2 = 50.51%, Q = 2.02, p = 0.12), with no improvement in GAD symptoms [odds ratio (OR) 1.22, 95% CI 0.74–2.01]. Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Marital problems

This outcome was reported in four studies (six data points) among 1285 participants using varying instruments and subjective questions. There was significant evidence of heterogeneity in the reporting of this outcome (I 2 = 61.21%, Q = 12.89, p = 0.02). It showed a small effect size in the improvement of marital problems (SMD: −0.23, 95% CI −0.42 to −0.03). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Treatment seeking practices

This outcome was reported in only two studies among 980 participants (Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016; Hantsoo et al., Reference Hantsoo, Criniti, Khan, Moseley, Kincler, Faherty, Epperson and Bennett2018). There was no evidence of heterogeneity in reporting of these outcomes. These interventions did not reveal any benefits toward the intervention group in improving treatment seeking practices. Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Self-esteem

Only two studies reported this outcome among 282 participants. There was substantial heterogeneity in reporting of this outcome (I 2 = 77.55%, Q = 4.54, p = 0.04). These interventions did not reveal any improvement in self-esteem among intervention recipients (SMD = −0.01, 95% CI −0.50 to 0.49). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Satisfaction with treatment

Only two studies reported this outcome among 317 participants. There was substantial heterogeneity in reporting of this outcome (I 2 = 90.72%, Q = 10.77, p = 0.001). These interventions did not reveal any improvement in satisfaction among intervention recipients (SMD = 0.26, 95% CI −0.66 to 1.88). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Maternal morbidity

Only two studies reported the outcome of postpartum hemorrhage among 1339 participants. There was substantial heterogeneity in reporting of this outcome (I 2 = 0%, Q = 0.04, p = 0.8). These interventions did not reveal any improvement in postpartum hemorrhage among intervention recipients (SMD = −0.15, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.22). Similarly, no significant improvement was noted in maternal use of treatment services (SMD = −0.21, 95% CI −0.89 to 0.48, I 2 = 76.55%). Other outcomes in this domain were reported in only one study each. Maternal admission to intensive care unit did not achieve statistical significance (SMD = −0.07, 95% CI −0.40 to 0.26, n = 1205). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal any significant changes in effects size for this outcome. No subgroup analyses were run for this outcome due to few studies reporting this outcome.

Breastfeeding practices

Initiation of breastfeeding was reported in only two studies, with no improvement estimated during pooled analyses (SMD = 0.05, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.46, I 2 = 0%, n = 1574). Similar non-significance was also observed in exclusive breastfeeding practices (SMD = 0.01, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.13, I 2 = 31.51%, n = 2438).

Meta-analysis for child outcomes

A variety of child outcomes were reported in a total of six studies. Infant engagement was reported in one study (two trials), yielding non-significant effect sizes (SMD = 0.13, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.66, I 2 = 0%, n = 302). Behavioral problems among infants were reported in two studies and did not show improvement among intervention recipients (SMD = 0.87, 95% CI 0.37–2.05, I 2 = 0%). Outcome pertaining to APGAR score was reported in two studies, showing non-significance (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50–1.21, I 2 = 0%). Similarly no improvement was observed in risk of low birth weight (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.31–1.36, I 2 = 78.45%, n = 2438); preterm birth (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.01–6.34, I 2 = 78.45%, n = 2438); perinatal mortality (OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.51–8.24, I 2 = 0%, n = 2438); and missed immunizations (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.50–1.21, I 2 = 0%).

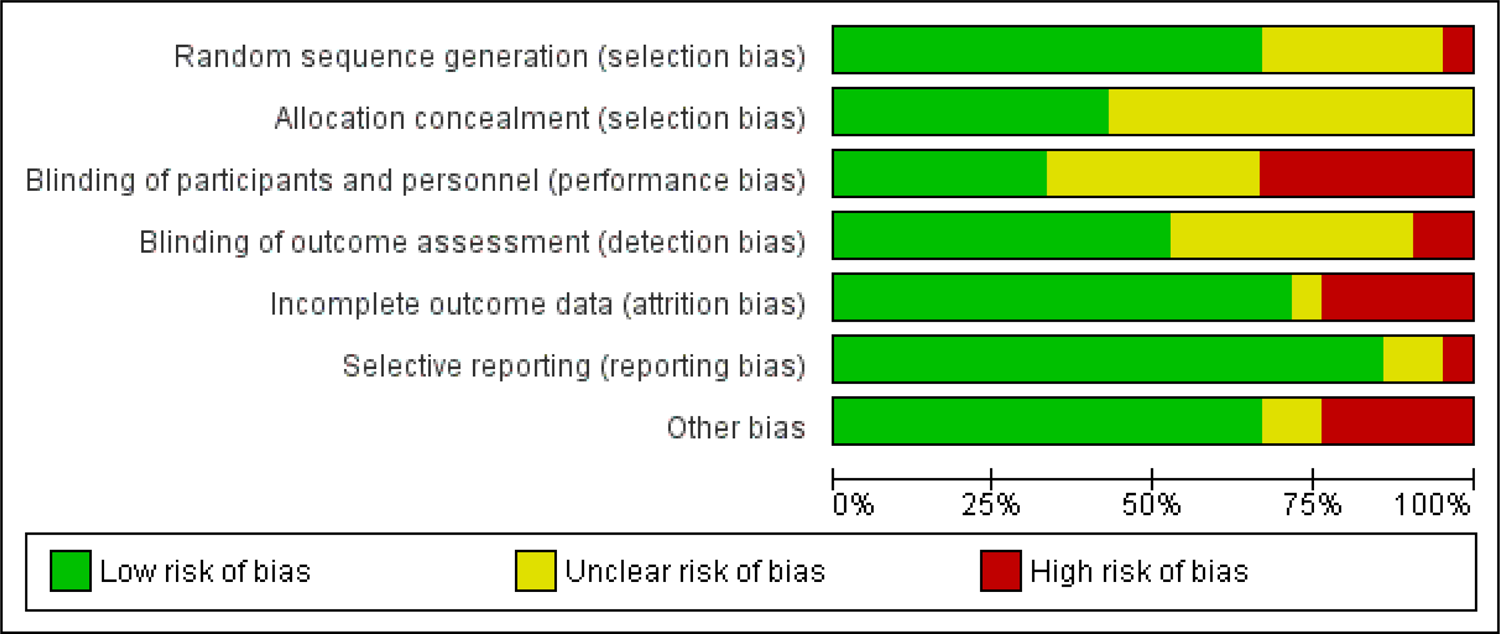

Risk of bias

A slightly higher proportion of studies (13 out of 21) presented with an overall higher risk of bias, with more than three matrices rated as high risk. Allocation concealment (n = 12) and blinding of participants and personnel (n = 14) and outcome assessors (n = 10) presented the highest risk of bias in included studies. These studies presented with the lowest risk in the domain of reporting bias (n = 3) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Risk of bias graph showing proportion of studies according to their risk of bias as per Cochrane tool.

Acceptability and feasibility

Data about the acceptability and feasibility of these interventions were reported in six studies (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, De Pascalis, Woolgar, Romaniuk and Murray2015; Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015; Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Greve et al., Reference Greve, Braarud, Skotheim and Slinning2018; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019). Overall, both the delivery agents and intervention recipients reported favorable attitudes toward these interventions. All these interventions were delivered by non-specialists except one which was delivered using online media (Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019). All of these studies were conducted in high-income countries in the UK (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016), the USA (Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019), Australia (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016), and Norway (Greve et al., Reference Greve, Braarud, Skotheim and Slinning2018). These studies had varying designs including cluster RCTs (n = 3) and feasibility or pilot RCTs (n = 3). The component of acceptability and feasibility of these studies was assessed using varying designs such as Likert scale type questionnaires (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, De Pascalis, Woolgar, Romaniuk and Murray2015; Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Greve et al., Reference Greve, Braarud, Skotheim and Slinning2018; Duffecy et al., Reference Duffecy, Grekin, Hinkel, Gallivan, Nelson and O'Hara2019), and qualitative interviews (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016). In these studies, acceptability and feasibility were assessed among both the intervention providers and recipients. Intervention recipients mainly reported positive attitudes toward these interventions as evident by high compliance rates, positive attitudes toward delivery agents, and perceived usefulness and satisfaction toward the intervention.

Attitude toward interventions

Cooper et al. assessed women's perceptions toward their intervention aimed at preventing postpartum depression by improving mother–infant relationship, using a Likert scale questionnaire (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, De Pascalis, Woolgar, Romaniuk and Murray2015). Women were enrolled in two intervention arms delivered either by lay health visitors or trained NHS health visitors. Both types of interventions accrued positive responses by intervention recipients who felt better supported both emotionally and practically and helped facilitate fostering of a good mother–infant bond. In a similar vein, Fisher et al.'s intervention garnered positive reviews from intervention recipients where over 85% of the mothers and their partners reported that the psychoeducational intervention was useful and enjoyable and helped them develop infant caring skills and sharing work with their partners fairly (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016). High compliance rates were also reported by Greve et al., where completion rates of a psychotherapeutic intervention exceeded 95% (Greve et al., Reference Greve, Braarud, Skotheim and Slinning2018).

Dimidjian et al. reported compliance rates, engagement, and satisfaction toward mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral intervention program (Dimidjian et al., Reference Dimidjian, Goodman, Felder, Gallop, Brown and Beck2015). They reported high compliance rates (88%) among postpartum women and a high degree of satisfaction using a questionnaire. Around 83% of women enrolled in their intervention program reported an improvement in their coping skills toward intense emotions and an improved ability to recognize triggers and warnings (72%) and respond to them by engaging in positive activities (89%). Women at risk of postpartum depression receiving home visit interventions to improve mother–child relationships reported a high satisfaction toward the intervention. They found it particularly helpful in improving their understanding of infant behavioral cues and acknowledged ways in which their partners could support them in child-rearing. However, one of the mothers in this intervention felt that maternal and child health-related questions asked during intervention delivery were not age-appropriate. Positive sentiments toward the use of EPDS were evident in Brugha et al. for an intervention where women reported that its use improved their self-awareness toward depressive symptoms, and being offered help, goal setting, and homework set them on the right path in preventing postpartum depression (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016).

Attitude toward delivery agents

Fisher et al. used a Likert scale type questionnaire to assess the recipients' perceptions of the intervention (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016). Over 90% of intervention recipients and their partners agreed that facilitators were knowledgeable, well prepared, understood their needs, and were respectful toward their culture. Greve et al. reported that their intervention recipients found their delivery agents performing home visits to be trustworthy and easy to communicate with (Greve et al., Reference Greve, Braarud, Skotheim and Slinning2018). Intervention recipients enrolled in Brugha et al., midwife-led cognitive-behavioral approaches were appreciative of the emotional care and reassurance provided to them (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016). Several women in this program cited the need for dedicated time for these listening visits- and felt rushed many times.

Perceptions of delivery agents

Brugha et al., in their midwife-led intervention program, was the only study reporting perspectives of delivery agents toward these interventions (Brugha et al., Reference Brugha, Smith, Austin, Bankart, Patterson, Lovett, Morgan, Morrell and Slade2016). The midwives in this program particularly appreciated the focus on identifying depression, albeit concerned with the idea that time had to be allocated toward the assessment of postpartum depression and delivery of intervention. In addition, the slow process of the delivery of psychological therapies, and achieving remission was another critical aspect, which was found to be different in routine midwifery practices. Therefore, they felt the need to be allotted dedicated work hours for this, which was not usually the case even after assurances made by their managers.

Cost-effectiveness

Dukhovny et al. presented a cost-effectiveness analysis for a volunteer-based program for the prevention of postpartum depression among high-risk Canadian women (Dukhovny et al., Reference Dukhovny, Hodnett, Weston, Stewart, Mao, Zupancic and Dennis2013). They reported that the mean cost per woman was $4497 in the peer support group and $3380 in the usual care group (difference of $1117, p < 0.0001). There was a 95% probability that the program would cost less than $20 196 per case of postpartum depression averted. Although this is a volunteer-based program, it resulted in a net cost to the health care system and society. However, this cost is within the range of other accepted interventions for this population. In another economic evaluation of a psychoeducational intervention, What Were We Thinking (WWWT) program in Australia, no differences in costs were revealed between the intervention recipients and their control counterparts (Ride et al., Reference Ride, Rowe, Wynter, Fisher and Lorgelly2014). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were $A36 451 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained and $A152 per percentage point reduction in the 30-day prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders. The estimate lies under the unofficial cost-effectiveness threshold of $A55 000 per QALY; however, there was considerable variability surrounding the results, with a 55% probability that WWWT would be considered cost-effective at that threshold.

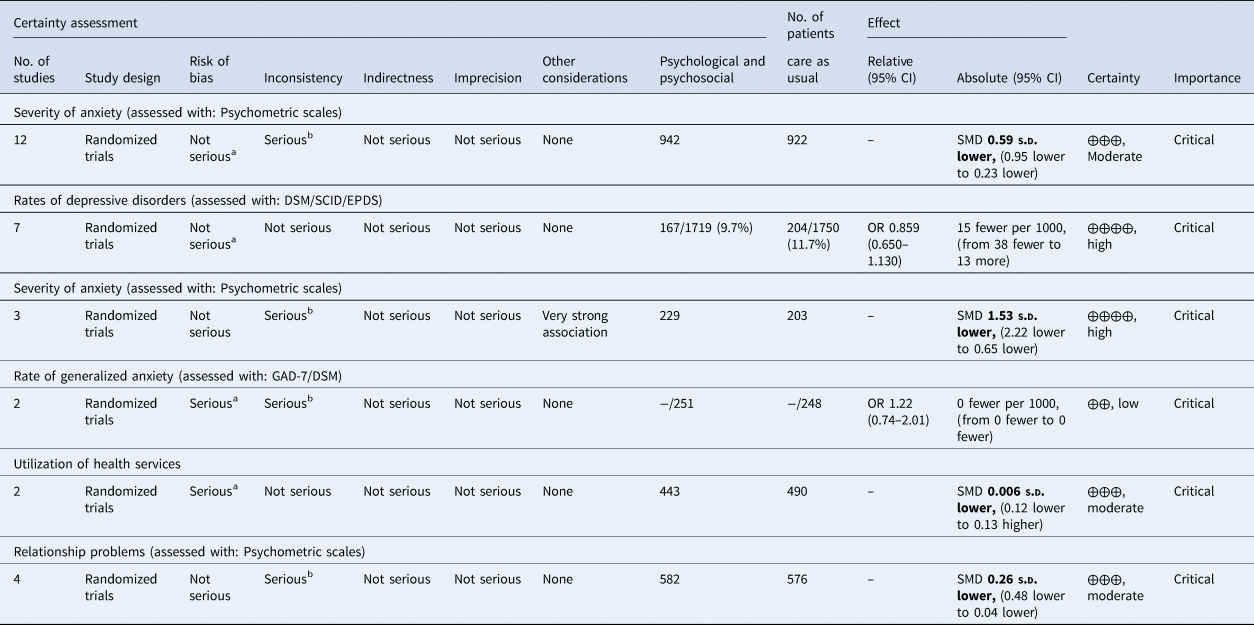

Quality of the evidence

Using the GRADE evidence guidelines (Guyatt, Reference Guyatt, Akl, Kunz, Vist, Brozek, Norris, Falck-Ytter, Glasziou, DeBeer and Jaeschke2011), we chose six critical outcomes for quality assessment (Table 4). Overall, the quality of evidence across these outcomes ranged from low to high. The quality of evidence for the severity of depressive symptoms outcome was stepped down to moderate due to significant heterogeneity in reporting of these outcomes. Interventions aimed at perinatal depression significantly reduced the severity of perinatal depressive symptoms but no significant changes were observed in the reduction of rates of depressive disorders as per diagnostic criteria of DSM/ICD. However, for the severity of anxiety symptoms, there was high-quality evidence that these interventions yielded high effect sizes in favor of intervention recipients. For the outcome of rates of depression using SCID, DSM, or EPDS, the quality of evidence was high while for rates of generalized anxiety, it was judged to be low due to issues with inconsistency and risk of bias among studies. The evidence for relationship problems was judged to be moderate after stepping it down by one degree due to evidence of heterogeneity.

Table 4. GRADE evidence table showing certainty of evidence for six critical outcomes

CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference; OR, odds ratio.

a A high proportion of studies reporting this outcome had a higher risk of bias.

b Substantial heterogeneity.

Discussion

There is good quality evidence that psychological and psychosocial interventions delivered during the antenatal period prevent perinatal anxiety and depression. These interventions are found to be feasible and acceptable in different settings and cultures. In addition to preventing perinatal anxiety and depression, these also improve treatment-seeking attitudes and psychosocial functioning. However, the evidence for the cost-effectiveness of these interventions is sparse.

Our findings are corroborated by previous evidence on the effectiveness of preventive interventions (Dennis and Dowswell, Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014; Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). Dennis and Dowswell (Reference Dennis and Dowswell2014) reported a weak to moderate strength effect size for the reduction in symptoms and clinical diagnosis for postpartum depression. The review by the US Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF), reported similar findings for interventions conducted in primary care settings in high-income countries (Curry et al., Reference Curry, Krist, Owens, Barry, Caughey, Davidson, Doubeni, Epling, Grossman, Kemper, Kubik, Landefeld, Mangione, Silverstein, Simon, Tseng and Wong2019). Based on their review, the USPSTF recommended clinicians provide or refer pregnant and postpartum persons who are at an increased risk of perinatal depression to counseling interventions. The present analyses thus, build on the aforementioned reports by providing the latest evidence published globally.

For perinatal anxiety, however, the evidence must be interpreted with caution. Although these interventions show a good effect size in the reduction of symptoms of anxiety, the three studies reporting this outcome used the self-reported Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Thus, this evidence may not be based on DSM and ICD criteria of diagnoses. Only three of the studies included in this evidence base targeted symptoms of anxiety as a primary outcome, however, these interventions did not employ therapeutic strategies specific to any psychological domain such as CBT or IPT. These were based on either psychoeducational principles or midwife-led care (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Wu, Ding, Zhu and Zhang2013; Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018).

The effectiveness of psychological and psychosocial interventions varies according to the timing of delivery of the intervention. As per our subgroup analyses, interventions should ideally be started in the antenatal period. The recent trials with interventions either delivered partly or wholly during the postpartum period were not found to be effective. However, it was observed that these interventions were based on varying theoretical backgrounds, principles, and content. And importantly, most of the trials in the latter set of studies tested psychosocial interventions only.

From the perspective of health systems, we found that these interventions do work when integrated with routine healthcare settings (Kenyon et al., Reference Kenyon, Jolly, Hemming, Hope, Blissett, Dann, Lilford and MacArthur2016). Therefore, it is recommended that the core packages of mental health services (from prevention to management) are integrated into routine antenatal and postnatal care. For countries with developing economies, however, this may not be economically feasible. For such settings, inspiration could be taken from the World Health Organization's Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) (World Health Organization, 2022). This could include the implementation of innovative strategies such as task-sharing by health workers or peers, training programs delivered electronically, or use of health applications, as well as establishment of effective referral mechanisms (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008; Atif et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters, Hagaman, Sikander, Maselko and Rahman2019). The Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression is a task-shifting, clinically and cost-effective intervention for perinatal depression, however, it has not yet been tested for prevention of either perinatal anxiety or depression (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Malik, Sikander, Roberts and Creed2008).

Strengths and limitations

The included evidence base lacked information about the implementation of these interventions. We could not find large-scale evaluation or feasibility studies reporting important implementation indicators such as training, supervision, and compensation of delivery agents. In addition, there was a lack of effort in developing standardized manuals of these interventions. These gaps in evidence severely impede efforts for their large-scale implementation in health systems. These also impede efforts for reproducibility and cross-cultural adaptation. Future studies should address the important implementation aspects of integration of these interventions into maternal and child health services, as well as planning for financial aspects; training and supervision; monitoring, and evaluation.

We found several gaps in prevention research for perinatal anxiety and depression. Evidence from low- and middle-income countries and rural settings was lacking in this systematic review. Most of the research has been conducted in the context of high-income countries. None of the interventions reported their effectiveness among refugees, migrants, and internally displaced perinatal women. There was only one intervention program designed for teen pregnancies which are prevalent in many traditional cultures. Future interventions should consider patient involvement in the development or tailoring of the interventions to local needs. Only two of the interventions (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Rowe, Wynter, Tran, Lorgelly, Amir, Proimos, Ranasinha, Hiscock, Bayer and Cann2016; Sanaati et al., Reference Sanaati, Charandabi, Eslamlo and Mirghafourvand2018) ensured participation by new fathers in these interventions. This is important to target relevant risk factors of maternal and child health (e.g. intimate partner violence and involvement of the father in parental care). None of the studies reported longer-term follow-ups. A lack of research was noted in the outcomes related to infant health, morbidity and mortality, and early childhood development, with only six studies reporting these outcomes. Therefore, more research is recommended to report the effectiveness of these interventions in improving child health. There was substantial heterogeneity in the quality of the studies included in the review, therefore, the results of this meta-analysis should be generalized with caution.

Conclusion

Interventions aimed at the prevention of anxiety and depression significantly reduced the severity of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms. These interventions were also found to be acceptable and feasible in many settings. We found several gaps in prevention research for perinatal anxiety and depression, especially in the context of implementation research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.17.

Data

All data associated with this manuscript have been provided in the main text.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the guideline development group at the World Health Organization for their feedback on the manuscript.

Author contributions

NC, TD, BF, and AW conceptualized the study. AW, MT, SN, SWZ, and HM conducted the database searches, screened the studies for inclusion and extracted data for the systematic review. AW analyzed the data and interpreted the results. AW, NC, and AR wrote the main manuscript text. TD, BF, and NC reviewed the manuscript critically. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interests to report. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. This systematic review informed the guideline development group of the World Health Organization (Geneva, Switzerland) for development of guidelines on screening for postpartum depression and anxiety.

Ethical standards

This is a systematic review and therefore, did not require any ethical approval or consent procedures.