Introduction

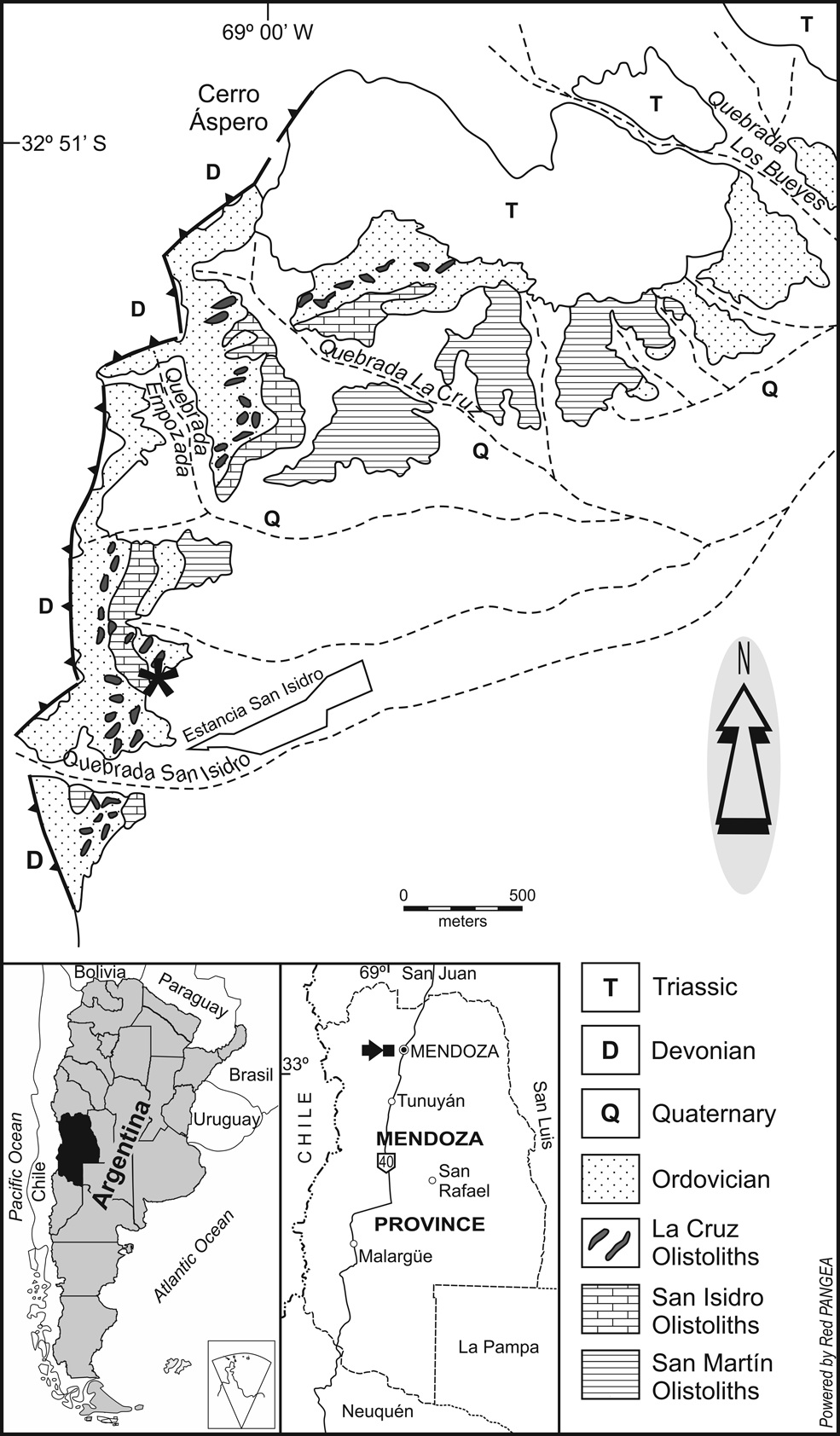

During the 1940s and 1950s, the naturalist Carlos Rusconi described large numbers of Cambrian trilobites from the southern Precordillera of Mendoza, western Argentina (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1956a and references therein; Cerdeño, Reference Cerdeño2005). Many of these fossils were collected from the San Isidro area (Fig. 1), where early Miaolingian to late Furongian exotic limestone blocks (San Isidro, San Martín, and La Cruz olistoliths) occur within Middle and Upper Ordovician shales (Bordonaro et al., Reference Bordonaro, Beresi and Keller1993; Keller, Reference Keller1999). It is now recognized that Cambrian trilobites from the Argentinian Precordillera have clear Laurentian affinities. Recent systematic revisions of the Rusconi collections provided updated information on several standard North American trilobite zones such as the Glossopleura walcotti, Ehmaniella, Lejopyge laevigata, Elvinia and Saukia zones (Tortello and Bordonaro, Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997; Bordonaro, Reference Bordonaro2003, Reference Bordonaro2014; Bordonaro and Fojo, Reference Bordonaro and Fojo2011; Pratt and Bordonaro, Reference Pratt and Bordonaro2014; Tortello, Reference Tortello2018, Reference Tortello2020, Reference Tortello2022).

Figure 1. Map of the San Isidro area, Mendoza Province, Argentina (after Bordonaro et al., Reference Bordonaro, Beresi and Keller1993 and Tortello, Reference Tortello2022). The 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro locality is indicated by an asterisk.

In addition, the Rusconi collections include numerous specimens from the Cedaria/Crepicephalus Zone (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954; Borrello, Reference Borrello1965, Reference Borrello and Holland1971) that have yet to be revised. These specimens come from 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro (Fig. 1) and were partially described by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954, p. 47, pl. 4, figs. 1–14), who pointed out the presence of the key genera Cedaria Walcott, Reference Walcott1924 and Tricrepicephalus Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935. Although Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) erected several local species from this assemblage, Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) synonymized some of them with Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861), a taxon that is known from the Cedaria and Crepicephalus zones of many regions of North America. Furthermore, Robison (Reference Robison1988) and Tortello and Bordonaro (Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997) reported, with some reservation, the agnostoid Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884) from this locality.

Aside from the specimens described by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954), many supplementary sclerites collected by Rusconi from 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro are available for study in the Museo de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas “Juan Cornelio Moyano” of Mendoza City. A comprehensive systematic revision of this material is presented here. Along with Tricrepicephalus, Coosia Walcott, Reference Walcott1911, and Coosella Lochman, Reference Lochman1936, the genera Meteoraspis Resser, Reference Resser1935 and Nasocephalus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954 are reported confidently from South America for the first time. In addition, specimens of Cedaria are of considerable biostratigraphic value and reinforce the Laurentian affinity of the fauna. Most of the genera and species identified were previously described exclusively from North America, a fact that provides new support for an allochthonous origin of the Argentine Precordillera (Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Jordan, Allmendinger, Mpodozis, Kay, Cortés and Palma1986; Astini et al., Reference Astini, Benedetto and Vaccari1995; Keller, Reference Keller1999; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Collins and Spencer2020 and references therein).

Geologic setting

The Estancia San Isidro locality (Fig. 1) was discovered by Carlos Rusconi and Manuel Tellechea (Museo J. C. Moyano) in the 1950s (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, Reference Rusconi1957) and was subsequently referred to by Borrello (Reference Borrello1965) as an isolated section cropping out in a “complex geologic setting.” Fossils occur together in a limestone that is now regarded as part of La Cruz Olistoliths (=La Cruz Limestones sensu Keller, Reference Keller1999), which are represented by a few centimeters to several meters thick carbonate blocks containing late Miaolingian and Furongian open-marine faunas, emplaced in Middle and Upper Ordovician shales of the Estancia San Isidro and Empozada formations. Full information on the geology of the San Isidro area was provided by Bordonaro et al. (Reference Bordonaro, Beresi and Keller1993), Heredia (Reference Heredia1995), Bordonaro and Banchig (Reference Bordonaro and Banchig1996), Keller (Reference Keller1999), Bordonaro (Reference Bordonaro2003), Heredia and Beresi (Reference Heredia and Beresi2004), and Ortega et al. (Reference Ortega, Albanesi, Heredia and Beresi2007).

Biostratigraphy

The most representative trilobites from the Estancia San Isidro locality were originally described by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) as Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, T. nahuelus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, T.? serranus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, Coosella convexa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, and Cedaria puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954. Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) first regarded this assemblage as latest middle Cambrian or earliest late Cambrian in age, and then Borrello (Reference Borrello1965, Reference Borrello and Holland1971, p. 407, tables 1, 2) assigned it to the North American Crepicephalus Zone (Guzhangian) pointing out the occurrence of T. anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 (see also Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1956b, Reference Rusconi1962, Reference Rusconi1967; Wilson, Reference Wilson1957, fig. 2; Furque and Cuerda, Reference Furque and Cuerda1979, p. 461). Later, Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) considered T. anarusconii, T. nahuelus and T.? serranus as junior synonyms of T. texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861).

The assemblage from San Isidro as revised here comprises Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884), Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924, C. puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861), Meteoraspis metra (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890), Coosia conicephala (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954), Coosella texana? Resser, Reference Resser1942, Nasocephalus cf. N. nasutus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, and Olenoides proa (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954).

Olenoides has limited value in biostratigraphy because of its exceptionally long stratigraphic range. Apart from its rare records from Central Asia, China, and Antarctica, this genus is well known from Wuliuan, Drumian, and Guzhangian strata of North America, from the Albertella Zone to the Cedaria/Crepicephalus Zone. In the Guzhangian of Quebec and Tennessee, it was recorded in association with Kormagnostus seclusus (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, Reference Rasetti1965).

Kormagnostus seclusus is a common species of the Cedaria and Crepicephalus faunas of North America, occurring in different lithofacies (e.g., Palmer, Reference Palmer1954a, b; Robison, Reference Robison1988 and references therein; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 and references therein; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000). In shallow, unrestricted neritic deposits, it is commonly the only agnostoid of the assemblages (Robison, Reference Robison1988). Kormagnostus seclusus has a stratigraphic range from at least the lower Lejopyge laevigata Zone to the Glyptagnostus stolidotus Zone. In addition to North America, it was described from Sakhayan and Nganasanian horizons of Siberia (Rosova, Reference Rosova1964), the Kormagnostus simplex (=K. seclusus) Zone of Kazakhstan (Ergaliev, Reference Ergaliev1980), and the Lejopyge laevigata Zone of the Precordillera of San Juan and the northern Precordillera of Mendoza, Argentina (Poulsen, Reference Poulsen1960; Robison, Reference Robison1988; Bordonaro and Liñán, Reference Bordonaro and Liñán1994; Tortello, Reference Tortello2011).

As stated by Palmer (Reference Palmer1954b), Tricrepicephalus texanus is a recurrent constituent of the Coosella Zone and its equivalents in Laurentian North America. As revised by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), this species is present in assemblages from the upper Cedaria and Crepicephalus zones at numerous localities in the United States, Canada, and Sonora (Mexico) (e.g., Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b; Sundberg and Cuen-Romero, Reference Sundberg and Cuen-Romero2021). In the Rabbitkettle Formation of northwestern Canada, T. texanus was documented throughout the uppermost Cedaria minor, C. selwyni, C. prolifica, and C. brevifrons zones (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992).

In addition, Coosella texana is known from the C. selwyni Zone of the Rabbitkettle Formation (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992) and from the Crepicephalus Zone of the Warrior Formation, Pennsylvania (Tasch, Reference Tasch1951), in both cases in association with Tricrepicephalus texanus. Likewise, Meteoraspis metra occurs in the Coosella Zone from the Riley Formation of Texas (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890; Lochman, Reference Lochman1938a; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b) and in the lower Crepicephalus Zone from the lower Deadwood Formation of South Dakota (Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000).

Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924 is the most abundant species in the fauna studied and provides precise age information as it is known from the eponymous zone of northwest Canada, as well as from the partially equivalent Crepicephalus Zone of British Columbia, Alabama, and Tennessee (Resser, Reference Resser1938; Palmer, Reference Palmer1962; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992). On the basis of the preceding discussion, the assemblage is assigned to the C. prolifica Zone, which correlates with the lower Crepicephalus Zone of the traditional North American genus-based zonation (e.g., Lochman-Balk and Wilson, Reference Lochman-Balk and Wilson1958; Robison, Reference Robison1964a; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, text-fig. 19; Westrop et al., Reference Westrop, Ludvigsen and Kindle1996, fig. 6).

An additional reference to the Crepicephalus Zone in Argentina was provided by Vaccari (Reference Vaccari1996), who reported Crepicephalus Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935, Coosella Lochman, Reference Lochman1936, Pemphigaspis Hall, Reference Hall1863, and Madarocephalus Resser, Reference Resser1938 from La Flecha Formation of the Precordillera of La Rioja and San Juan (see also Benedetto et al., Reference Benedetto, Vaccari, Waisfeld, Sánchez and Foglia2009).

Materials and methods

Materials and preservation

The collection studied consists of disarticulated specimens that are preserved mostly as testate or partly exfoliated sclerites. Before photography, the material was coated with magnesium oxide smoke from burning magnesium ribbon. To give a full picture of the morphology of the exoskeleton, some specimens are illustrated in dorsal, lateral, and frontal views.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

The specimens examined in this study are housed in the Museo de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas “Juan Cornelio Moyano” (Mendoza City, Argentina) with the prefix MCNAM.

Systematic paleontology

Terminology

The morphological terms used in the following have been defined mostly by Whittington and Kelly (Reference Whittington, Kelly and Kaesler1997), with additional terminology from Shergold et al. (Reference Shergold, Laurie and Sun1990) for the agnostoid trilobites. The following abbreviations are used: sag., sagittally; exsag., exsagittally; long., longitudinally; tr., transversally.

Order Agnostida Salter, Reference Salter1864

Family Ammagnostidae Öpik, Reference Öpik1967

Genus Kormagnostus Resser, Reference Resser1938

Type species

Agnostus seclusus Walcott, Reference Walcott1884 from the Guzhangian of Tennessee (by synonymy with Kormagnostus simplex Resser, Reference Resser1938; see Robison, Reference Robison1988).

Remarks

Palmer (Reference Palmer1954a), Robison (Reference Robison1988), Shergold et al. (Reference Shergold, Laurie and Sun1990), Peng and Robison (Reference Peng and Robison2000), and Westrop and Adrain (Reference Westrop and Adrain2013) discussed in detail the scope of Kormagnostus Resser, Reference Resser1938. This genus is characterized mainly by having an effaced anteroglabella, a well-defined to partially effaced pygidial axial furrow, a wide (tr.), elongate, parallel-sided or posteriorly expanded pygidial axis reaching posterior border furrow, weak to effaced transaxial furrows, and broad cephalic and pygidial marginal furrows. As stated by Westrop and Adrain (Reference Westrop and Adrain2013), the closely related genus Kormagnostella Romanenko in Romanenko and Romanenko, Reference Romanenko and Romanenko1967 is distinguished by showing an extremely effaced pygidium, a narrower, well-incised pygidial border furrow, and a broad and convex pygidial border and by lacking posterolateral spines throughout holaspid ontogeny.

Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884)

Figure 2.1, 2.2

- Reference Walcott1884

Agnostus seclusus Walcott, p. 25, pl. 9, fig. 14.

- Reference Rusconi1954

Kormagnostus cuchillensis Rusconi, p. 48, text-fig. 25.

- Reference Robison1988

Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott); Robison, p. 45, fig. 11.5–11.15 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Pratt1992

Kormagnostus seclusus; Pratt, p. 31, pl. 3, figs. 1–3, 14–29 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997

Kormagnostus seclusus; Tortello and Bordonaro, p. 78, fig. 3.12–3.17 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000

Kormagnostus seclusus; Stitt and Perfetta, p. 203, fig. 6.1–6.4.

- Reference Tortello2011

Kormagnostus seclusus; Tortello, p. 118, fig. 2C, D, G.

Figure 2. (1, 2) Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884): (1) mostly exfoliated cephalon, MCNAM 17795; (2) testate pygidium, MCNAM 17369, Kormagnostus cuchillensis Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype (not illustrated previously). (3–16) Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924: (3, 8) mostly exfoliated cranidium in dorsal (3) and oblique (8) views, MCNAM 17374, Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 4); (4) partially exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17440; (5) partially testate pygidium, MCNAM 17425, Cedaria puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 10); (6) partially exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17397 (previously assigned to Cedaria puelchana by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, p. 52); (7) mostly exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17429; (9) latex cast of partially testate pygidium, MCNAM 18794; (10) latex cast of mostly exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17426; (11) latex cast of mostly exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17932; (12) testate pygidium, MCNAM 17439; (13, 16) mostly testate pygidium (top) and two fragmentary cranidia (bottom) in dorsal (13) and lateral (16) views, MCNAM 17769; (14) partially exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17441; (15) mostly exfoliated pygidium, MCNA 17428. Cedaria prolifica Zone of San Isidro, Mendoza. (1, 2) Scale bars = 1 mm; (3–16) scale bars = 2 mm.

Holotype

Cephalon (U.S. National Museum 24586) from the Hamburg Limestone, Eureka District, Nevada (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884, pl. 9, fig. 14; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954a, pl. 13, fig. 1).

Occurrence

Widespread in the Guzhangian of the United States (e.g., Nevada, Utah, Texas, Missouri, Tennessee, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana), northwest and eastern Canada, Greenland, western Argentina, Kazakhstan, and Siberia (e.g., Palmer, Reference Palmer1954a, b; Rosova, Reference Rosova1964; Ergaliev, Reference Ergaliev1980; Robison, Reference Robison1988 and references therein; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 and references therein; Tortello and Bordonaro, Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997 and references therein; Peng and Robison, Reference Peng and Robison2000, p. 35; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000; Tortello, Reference Tortello2011).

Remarks

Robison (Reference Robison1988) was the first to suggest the occurrence of Kormagnostus seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884) at the Estancia San Isidro locality, regarding it as a possible senior synonym of Kormagnostus cuchillensis Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, which was later endorsed by Tortello and Bordonaro (Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997). Unfortunately, the holotype of K. cuchillensis is an incomplete pygidium (Tortello and Bordonaro, Reference Tortello and Bordonaro1997, fig. 3.17). In addition, a paratype pygidium (not figured previously) and a supplementary cephalon are illustrated herein. These sclerites are characterized by an effaced anteroglabella; a median glabellar node centered on the posteroglabella; a rounded glabellar culmination; smooth, anteriorly confluent genae; a broad, subparallel-sided pygidial axis surrounded by faint axial furrows; a small axial tubercle; and a slightly constricted pygidial acrolobe. Although the pygidial border is imperfectly preserved and thus it is not possible to determine the presence or absence of posterolateral spines, the morphology of the specimens conforms well with K. seclusus (Walcott, Reference Walcott1884), a highly variable species that is known from the Guzhangian of various regions of Laurentia, in addition to Kazakhstan and Siberia. Palmer (Reference Palmer1954a, b), Robison (Reference Robison1988), Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), and Peng and Robison (Reference Peng and Robison2000) discussed in detail the synonymy and scope of K. seclusus. As in the case of some exfoliated cephala described from North America (e.g., Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b, pl. 76, fig. 8; Lochman and Hu, Reference Lochman and Hu1960, pl. 99, figs. 9, 17; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, text-fig. 26A; Westrop et al., Reference Westrop, Ludvigsen and Kindle1996, fig. 13.15; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000, fig. 6.1, 6.2), the material from San Isidro shows slight indications of a subtriangular anterior glabellar lobe.

As stated by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), Kormagnostus seclusus differs from K. robisoni Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 from the Cedaria selwyni Zone of the Rabbitkettle Formation, northwest Canada (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, pl. 3, figs. 30–36, text-fig. 26C), because the latter has an elongate pygidium that is subtrapezoidal in outline, a bulb-shaped posteroaxis, and a markedly constricted pygidial acrolobe. Kormagnostus flati Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 from the Cedaria brevifrons Zone of the Rabbitkettle Formation, northwest Canada, and the Crepicephalus Zone of the Pilgrim Formation, Montana (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 5, figs. 15, 16; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, pl. 2, figs. 27–33, text-fig. 26B), is slightly differentiated from K. seclusus in the more anterior location of the median glabellar node, the wider (tr.) pygidial axis, and the unconstricted pygidial acrolobe.

Order Ptychopariida Swinnerton, Reference Swinnerton1915

Family Cedariidae Raymond, Reference Raymond1937

Genus Cedaria Walcott, Reference Walcott1924

Type species

Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924, from the upper Guzhangian of Alabama, by original designation.

Remarks

Palmer (Reference Palmer1962) and Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) discussed in detail the morphology of Cedaria Walcott, Reference Walcott1924, which is followed here. As pointed out by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), it is a genus of Cedariidae with an anteriorly rounded subrectangular glabella, a moderately long (sag.) anterior border, divergent anterior facial sutures, palpebral lobes located at glabellar midlength, and a semicircular to transversely semielliptical pygidium.

Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924

Figures 2.3–2.16, 3.1–3.3

- Reference Walcott1924

Cedaria prolifica Walcott, p. 55, pl. 10, fig. 6.

- Reference Walcott1925

Cedaria prolifica; Walcott, p. 79, pl. 17, figs. 18–21.

- Reference Resser1938

Cedaria prolifica; Resser, p. 67, pl. 11, figs. 1, 2, 6, 7.

- Reference Rusconi1954

Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi (part), p. 49, pl. 4, fig. 4 (only; figs. 2, 3, Tricrepicephalus texanus).

- Reference Rusconi1954

Cedaria puelchana Rusconi (part), p. 52, pl. 4, fig. 10 (only).

- Reference Palmer1962

Cedaria prolifica; Palmer, p. 26, pl. 3, figs. 9, 10, 14–16, 20, pl. 6, fig. 14.

- Reference Pratt1992

Cedaria prolifica; Pratt, p. 80, pl. 30, figs. 1–4 (see for further synonymy).

Figure 3. (1–3) Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924: (1) small, exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17778; (2) partially exfoliated pygidium (top) (see also Fig. 2.14) and pygidial external mold (bottom), MCNAM 17441; (3) exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17791. (4–14) Cedaria puelchana Rusconi,Reference Rusconi1954: (4) cranidial and pygidial fragments, MCNAM 18780; (5) exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17424, Cedaria puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 9); (6, 7) partially testate cranidium and pygidial fragment in dorsal (6) and lateral (7) views, MCNAM 17457; (8) partially exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17790; (9, 12, 13) mostly exfoliated cranidium in dorsal (9), lateral (12), and anterior (13) views, MCNAM 18781; (10) exfoliated cranidium and fragmentary pygidium, MCNAM 17774; (11) mostly exfoliated hypostome (in association with a helcionelloid mollusk, top), MCNAM 17794; (14), partially testate pygidium, MCNAM 17770. Cedaria prolifica Zone of San Isidro, Mendoza. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Lectotype

Complete exoskeleton (U.S. National Museum 70266) from the Conasauga Formation, Cedar Bluff, Cherokee County, Alabama (Walcott, Reference Walcott1925, pl. 17, fig. 28; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, p. 80).

Occurrence

Alabama, Conasauga Formation; Tennessee, Nolichucky Formation; British Columbia, northern Rocky Mountains; Northwest Canada, Rabbitkettle Formation (Walcott, Reference Walcott1925; Resser, Reference Resser1938; Palmer, Reference Palmer1962; Fritz, Reference Fritz1970; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992). 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Remarks

These specimens represent a species of Cedaria with a strongly divergent anterior facial suture; a moderately convex anterior border; a distinct anterior border furrow constituted by a row of medium-sized pits; a preglabellar field subequal in length (sag.) to longer than cranidial border, with variably expressed caecate prosopon; a semicircular pygidium with axis bearing five to six axial ring furrows; pleural fields showing a deep anterior border furrow and four pairs of distinctive, widely spaced pleural furrows; and a moderately broad pygidial border. Following the diagnoses of Palmer (Reference Palmer1962) and Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), the material can be confidently assigned to Cedaria prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924. Although there are only a few fragmentary cranidia available for study, they show strongly divergent anterior branches of the facial suture, which is one of the most characteristic features of the species. Variations in the sagittal length of the preglabellar field and the degree of expression of the caecate prosopon were also documented by Palmer (Reference Palmer1962) and Resser (Reference Resser1938), respectively. As in other species of Cedaria, the relative length of the preglabellar field seems to increase during holaspid ontogeny.

One of the cranidia examined (MCNAM 17374, Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype; Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 4) (Fig. 2.3, 2.8) was referred questionably to Cedaria selwyni Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992; and later discussions in Bordonaro and Banchig, Reference Bordonaro and Banchig1996; Bordonaro, Reference Bordonaro2003; Sundberg, Reference Sundberg2018); however, its anterior facial suture seems to be strongly divergent, and therefore a reassignment to C. prolifica is preferred herein. Likewise, a C. puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype pygidium (MCNAM 17425, Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 10) and one cranidium questionably referred to C. puelchana by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954, p. 52) are reillustrated here (Fig. 2.5, 2.6) and reassigned to C. prolifica.

Cedaria prolifica and C. minor (Walcott, Reference Walcott1916), from the upper Guzhangian of Utah, northwestern Canada, and Greenland (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 and references therein), exhibit similar pygidia, but the latter species is distinguished by having less-divergent anterior sections of the facial suture, a flat anterior cranidial border, and a shallower anterior border furrow in which pits are absent or faint (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992).

Cedaria gaspensis Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, from the Crepicephalus fauna of Gaspé, Quebec (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, pl. 67, figs. 26–29), differs from C. prolifica mainly by bearing a larger number of pygidial axial rings and pleural furrows. Cedaria selwyni Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, from the eponymous zone of Northwest Canada and Nevada (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, pl. 31, figs. 9–16, text-fig. 31B; Sundberg, Reference Sundberg2018, fig. 18.1–18.7), is differentiated by its effaced pygidium.

Cedaria puelchana Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954

Figure 3.4–3.14

- Reference Rusconi1954

Cedaria puelchana Rusconi, p. 52, pl. 4, fig. 9 (only; fig. 10, Cedaria prolifica).

Holotype

Pygidium (MCNAM 17424) from La Cruz Olistoliths, 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro, Mendoza (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 9; Fig. 3.5).

Diagnosis

A species of Cedaria with a large exoskeleton; noticeable lateral glabellar furrows; strongly divergent anterior branches of the facial suture; a well-developed preglabellar field that is much longer (sag.) than cranidial border; elevated palpebral lobes lacking palpebral furrows; and a semicircular pygidium with a narrow (tr.), long pygidial axis composed of 7–8 rings, five pairs of distinct pleural furrows, and a slender border.

Occurrence

Two hundred meters northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza; La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Description

Cranidium slightly convex, with broadly curved anterior margin and somewhat downsloping preglabellar field, maximum width between palpebral lobes ~70% (estimated) of total cranidial length; glabella of moderate size, subrectangular in outline, longer than wide, little elevated above genal region, occupying about three-quarters of total cranidial length (sag.) and 55% of cranidial width (tr.) at level of abaxial tip of S2, slightly constricted at L3, rounded to weakly pointed anteriorly, delimited by narrow axial and preglabellar furrows; maximum glabellar width at L1; L0 smooth or with faint indications of a delicate occipital node, broadly rounded posteriorly, representing ~13% of total glabellar length; S0 transglabellar, deeper, and fairly sinuous at sides and shallow and straight on midline; L1 much longer (exsag.) than L0, occupying ~22–25% of total glabellar length; lateral glabellar furrows S1–S4 faint but distinct, oblique backward, disconnected at middle; S2 and S4 weaker than S1 and S3; a supplementary furrow is sagittally extended from S1 to S2; anterior cranidial border narrow (sag.), weakly convex, of nearly constant breadth (sag., exsag.), bounded by a shallow border furrow that contains closely spaced pits; preglabellar field well developed, much longer (sag.) than anterior border, slightly downsloping, crossed by radiating prosopon ridges; anterior facial suture strongly divergent; ocular ridge delicate, oblique backward; palpebral area of the fixigena narrow (tr.); palpebral lobe arcuate, elevated, situated slightly behind cranidial midpoint, lacking palpebral furrow, extended from the level of S1 to the level of S3, occupying ~20% of the total cranidial length (sag.); posterior fixigena broadened outward, with shallow posterior border furrow and slightly convex, narrow (exsag.) posterior border; external surface of cuticle smooth or delicately granulated. Largest observed cranidium 22 mm long (sag.).

A relatively large hypostome is tentatively assigned to this species. It is suboval in outline, longer than wide, with subtriangular anterior wings, a gently convex median body, a short (sag.) and posteriorly rounded posterior lobe, and a moderately wide, depressed marginal border of uniform width, which exhibits subparallel terrace lines.

Pygidium semicircular in outline, somewhat convex transversely and longitudinally, wider than long, with entire margin; axis long and narrow, hardly tapered backward, scarcely elevated above level of pleural fields, surrounded by narrow axial furrows, with marked anterior three rings and faint or indistinct posterior four or five rings, ending in blunt terminal piece reaching marginal border; articulating half-ring narrow (sag.), crescentic; anterior border furrow deep, delimiting a narrow (exsag.) anterior border; pleural fields wide (tr.), weakly convex, crossed by five straight to slightly curved, oblique pleural furrows ending at level of marginal border; lateral and posterior border narrow, scarcely convex, bounded by a weak border furrow; in largest specimens, the border furrow is hardly represented by a change in slope of exoskeleton. Largest observed pygidium 21 mm long (sag.).

Remarks

Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) described Cedaria puelchana on the basis of one holotype pygidium (MCNAM 17424) (Fig. 3.5), one paratype pygidium (MCNAM 17425) (Fig. 2.5), and one cranidium (MCNAM 17397) (Fig. 2.6). The latter two sclerites are reassigned in the preceding to C. prolifica, and a new set of cranidia is described herein for C. puelchana.

Cedaria puelchana has a certain resemblance to Proceratopyge Wallerius, Reference Wallerius1895 in glabellar shape, appearance of the glabellar furrows, and position of the eyes, but the latter clearly differs by possessing a spinose pygidium. The cranidium of Cedaria puelchana compares most closely with that of specimens of Cedaria showing indications of arcuate lateral glabellar furrows (e.g., Lochman and Hu, Reference Lochman and Hu1962, pl. 2, figs. 1, 13; Robison, Reference Robison1988, fig. 14.9), although it is differentiated by its more-divergent anterior facial suture.

Cedaria puelchana also resembles C. prolifica Walcott, Reference Walcott1924, but the latter is distinguished mainly by its effaced glabella and its more transverse, less semicircular pygidium. In addition, C. gaspensis Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, from the upper Guzhangian of Quebec (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, pl. 67, figs. 26–29), further differs by having a larger number of pygidial pleural furrows.

A fragmentary pygidium from the Cedaria selwyni Zone of Nevada (Sundberg, Reference Sundberg2018, fig. 18.13) has similitude with C. puelchana, but it exhibits a narrower (tr.) pleural field.

Family Tricrepicephalidae Palmer, Reference Palmer1954

Remarks

Palmer (Reference Palmer1954b) provided diagnoses of the Guzhangian genera Tricrepicephalus Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935 and Meteoraspis Resser, Reference Resser1935 (see also Lochman, Reference Lochman1938b) and included them in the family Tricrepicephalidae, concepts that are followed here.

Genus Tricrepicephalus Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Type species

Arionellus (Bathyurus) texanus Shumard, Reference Shumard1861 from the upper Guzhangian of the United States, by original designation.

Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861)

Figure 4

- Reference Shumard1861

Arionellus (Bathyurus) texanus Shumard, p. 218.

- Reference Palmer1954b

Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard); Palmer, p. 755, pl. 81, fig. 9 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Rusconi1954

Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi (part), p. 49, pl. 4, figs. 2, 3 (only; fig. 4, Cedaria prolifica).

- Reference Rusconi1954

Tricrepicephalus nahuelus Rusconi, p. 50, pl. 4, fig. 5.

- Reference Rusconi1954

Tricrepicephalus? serranus Rusconi, p. 51, pl. 4, fig. 6.

- Reference Rusconi1954

Coosella convexa Rusconi, p. 51, pl. 4, figs. 7, 8.

- Reference Castellaro1963

Tricrepicephalus anarusconii; Castellaro, p. 34, text-fig. (pygidium only).

- Reference Pratt1992

Tricrepicephalus texanus; Pratt, p. 62, pl. 21, figs. 1–7 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Sundberg and Cuen-Romero2021

Tricrepicephalus texanus; Sundberg and Cuen-Romero, p. 7, fig. 5a–g (see for further synonymy).

Figure 4. Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861): (1, 2, 5, 6) exfoliated cranidium in dorsal (1), lateral (2, 5), and anterior (6) views, MCNAM 17393, Coosella convexa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 7); (3) incomplete exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17392, Coosella convexa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 paratype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 8); (4) mostly exfoliated librigenal fragment, MCNAM 17362; (7) exfoliated cranidial fragment, MCNAM 17377; (8) exfoliated fragmentary cranidium, MCNAM 17376; (9) exfoliated fragmentary cranidium, MCNAM 17452; (10) mostly exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17454; (11) mostly exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17504; (12) exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17583; (13) mostly exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 18784; (14) exfoliated hypostome, MCNAM 17557; (15) exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17380, Tricrepicephalus nahuelus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 5); (16) exfoliated fragmentary pygidium, MCNAM 17756; (17) poorly preserved cranidium, MCNAM 17388, Tricrepicephalus serranus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 6); (18) mostly exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17382; (19, 20) mostly exfoliated pygidium in dorsal (19) and lateral (20) views, MCNAM 17379, Tricrepicephalus anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously by Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, pl. 4, fig. 2). Cedaria prolifica Zone of San Isidro, Mendoza. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Neotype

Cranidium (U.S. National Museum 91865) from Potatotop Hill, seven miles northwest of Burnet, Burnet County, Texas (U.S.N.M. loc. 67-a) (Lochman, Reference Lochman1936, pl. 9, fig. 27).

Occurrence

Southern Mackenzie Mountains, Northwest Canada, Cedaria minor Zone to Cedaria brevifrons Zone (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992). Western Newfoundland, eastern Canada, Crepicephalus Zone (Kindle, Reference Kindle1982). Widespread in United States (South Dakota, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, Texas, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Alabama), Cedaria and Crepicephalus zones (e.g., Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b and references therein; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992 and references therein); Sonora, Mexico, Crepicephalus Zone (Sundberg and Cuen-Romero, Reference Sundberg and Cuen-Romero2021 and references therein); San Isidro area, western Argentina, Cedaria prolifica Zone (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992; this paper).

Remarks

Tricrepicephalus texanus (Shumard, Reference Shumard1861) is a species with a high range of morphological variability involving mainly cranidial surface granulation and length and shape of the anterior border. Palmer (Reference Palmer1954b) and Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) discussed in detail the scope of this taxon. According to the broad species concept of Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) and Sundberg and Cuen-Romero (Reference Sundberg and Cuen-Romero2021), T. texanus exhibits variably developed granules on the cranidium, and its extended synonymy includes, among others, T. coria (Walcott, Reference Walcott1916).

As stated in the preceding, T. anarusconii Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 (Fig. 4.19, 4.20, holotype), T. nahuelus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 (Fig. 4.15, holotype), and T.? serranus Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 (Fig. 4.17, holotype) from 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro were synonymized with T. texanus by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992). Likewise, several additional specimens from the Rusconi collection, including cranidia with thickly granulated (e.g., Fig. 4.1–4.3, 4.5, 4.6), slightly granulated (Fig. 4.12), or smooth (e.g., Fig. 4.11) glabellae, are herein referred to T. texanus. Among these specimens, two cranidia (holotype and paratype) and one librigenal fragment (Fig. 4.1–4.6) were originally described as Coosella convexa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 by Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954, p. 51, pl. 4, figs. 7, 8) (see preceding synonymy). Intraspecific variation in the material studied also involves the convexity of the anterior border, which is slightly convex (Fig. 4.11) or flat (Fig. 4.7, 4.13), the degree of expression of the pits in the marginal furrow (e.g., compare Fig. 4.1 with Fig. 4.11), and the general outline of the glabella.

The hypostome of T. texanus is seldom illustrated in the literature. As previously shown by Lochman in Lochman and Duncan (Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 5, fig. 3), it is characterized by having a convex, granulated median body (Fig. 4.14). This sclerite is suboval in outline, with a rounded anterior margin and a narrow, concave lateral border of uniform width, which is clearly delimited by a distinct border furrow. Maculae are well impressed, running backward with an angle of ~45°. Posterior lobe and border lack granulation.

Tricrepicephalus texanus differs from T. tripunctatus (Whitfield, Reference Whitfield1876) because the latter bears a conspicuous occipital spine (e.g., Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000).

Genus Meteoraspis Resser, Reference Resser1935

Type species

Ptychoparia? metra Walcott, Reference Walcott1890 from the upper Guzhangian of Texas, by original designation.

Meteoraspis metra (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890)

Figure 5.1–5.15

- Reference Walcott1890

Ptychoparia? metra Walcott, p. 273, pl. 21, fig. 7.

- Reference Resser1935

Meteoraspis metra (Walcott); Resser, p. 41.

- Reference Lochman1938a

Meteoraspis metra; Lochman, pl. 17, fig. 1–3.

- Reference Palmer1954b

Meteoraspis metra; Palmer, p. 753, pl. 82, figs. 2, 4 (see for further synonymy).

- Reference Rusconi1954

Meteoraspis tinguirensis Rusconi, p. 55.

- Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000

Meteoraspis metra; Stitt and Perfetta, p. 212, fig. 9.16–9.19.

Figure 5. (1–15) Meteoraspis metra (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890): (1, 8, 9, 11) mostly testate cranidium in dorsal (1), oblique (8, 11), and anterior (9) views, MCNAM 17463; (2, 13, 14) testate cranidium in dorsal (2), anterior (13), and oblique (14) views, MCNAM 17618; (3, 15) testate cranidium in dorsal (3) and anterior (15) views, MCNAM 17339; (4, 10) partially exfoliated pygidium in dorsal (4) and posterior (10) views, MCNAM 17510, Meteoraspis tinguirensis Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (not illustrated previously); (5, 6) testate cranidium in lateral (5) and anterior (6) views, MCNAM 17335; (7, 12) partially testate cranidium in dorsal (7) and oblique (12) views, MCNAM 17609. (16, 20, 21) Coosia conicephala (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954): (16) exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17525; (20) testate cranidium, MCNAM 17612; (21) small, mostly testate cranidium, MCNAM 17448, Querandinia conicephala Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously with a sketch, Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 29). (17, 18, 22) Coosella texana? Resser, Reference Resser1942: (17) partially exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 18782; (18, 22) partially exfoliated cranidium in dorsal (18) and lateral (22) views, MCNAM 18037. (19) Nasocephalus cf. N. nasutus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, mostly exfoliated cranidium, MCNAM 17675. (23–25) Olenoides proa (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954): (23, 24) partially exfoliated cranidium in dorsal (23) and lateral (24) views, MCNAM 17445, Cancapolia proa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 holotype (illustrated previously with a sketch, Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 28); (25) partially exfoliated pygidium, MCNAM 17765. Cedaria prolifica Zone of San Isidro, Mendoza. (1–20, 22–25) Scale bars = 2 mm; (21) scale bar = 1 mm.

Holotype

Cranidium (U.S. National Museum 23858) from Potatotop Hill, six miles northwest of Burnet, Burnet County, Texas (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890, pl. 21, fig. 7; Lochman, Reference Lochman1938a, pl. 17, figs. 1–3).

Occurrence

Burnet County, Central Texas, Riley Formation, Coosella Zone (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890; Lochman, Reference Lochman1938a; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b); Black Hills, South Dakota, lower Deadwood Formation, lower Crepicephalus Zone (Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000); 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, upper Guzhangian, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Remarks

Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954, p. 55) first reported Meteoraspis Resser, Reference Resser1935 from the Estancia San Isidro as M. tinguirensis Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, which was based on one isolated pygidium (holotype MCNAM 17510). This specimen is illustrated herein for the first time (Fig. 5.4, 5.10), together with several cranidia that are regarded here as conspecific (Fig. 5.1–5.3, 5.5–5.9, 5.11–5.15).

These cranidia show well-developed dorsal, marginal, and occipital furrows; a long, unfurrowed, slightly tapered glabella that is well elevated above level of fixigenae; a convex, arched anterior border; a minute, downsloping preglabellar field; very narrow (tr.) and upsloping palpebral areas of fixigenae; and palpebral lobes located at a level slightly behind the center of the glabella. For its part, the pygidium has a large, subparallel-sided pygidial axis composed of three rings and a rounded terminal piece; pleural fields showing faint indications of wide, shallow pleural furrows; a broadly rounded posterior margin; and a pair of posteriorly directed spines, preserving only their bases and proximal parts, extending from the posterolateral corners of the marginal border. The surface of the exoskeleton lacks granulation. Among the numerous species of Meteoraspis, the presence of a smooth test, an elongate and tumid glabella, very narrow (tr.) palpebral area of fixigenae, and a proportionately large pygidial axis is diagnostic of M. metra (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890) from the Coosella Zone of Central Texas and the lower Crepicephalus Zone of South Dakota (Walcott, Reference Walcott1890, pl. 21, fig. 7; Lochman, Reference Lochman1938a, pl. 17, figs. 1–8; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b, p. 753, pl. 82, figs. 2, 4; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000, fig. 9.16–9.19). Meteoraspis tinguirensis Rusconi is therefore regarded as a junior synonym of M. metra.

Meteoraspis robusta Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, from the Cedaria Zone of Montana, South Dakota, and Texas (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 9, figs. 11–17; Palmer Reference Palmer1954b, pl. 82, fig. 3; Stitt, Reference Stitt1998, fig. 7.26), differs from M. metra by having a shorter (sag.) and less-tumid glabella, wider (tr.) palpebral areas of the fixigenae, and more anteriorly located palpebral lobes.

As stated by Rasetti (Reference Rasetti1965), M. brevispinosa Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1965, from the Crepicephalus Zone of Tennessee (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1965, pl. 6, figs. 9–12), is differentiated from M. metra mainly by having a straighter posterior pygidial margin and extremely short marginal spines. Meteoraspis spinosa Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, from the Cedaria Fauna of Montana (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 9, figs. 18–24), is easily distinguished by bearing noticeable axial spines on the pygidium.

Some species of Meteoraspis are only partially known by their cranidia or their pygidia. The cranidia of both M. elongata Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, from the Cedaria Fauna of Montana (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 9, figs. 4–7), and M. banffensis Resser, Reference Resser1942, from the Sullivan Formation of Alberta (Resser, Reference Resser1942, pl. 13, figs. 5–8), differ from that of M. metra mainly by showing a longer (sag.) preglabellar field. For its part, the pygidium of M. loisi Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, from Texas and Montana (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 5, figs. 24–26; Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b, pl. 82, fig. 1), has a longer postaxial area and a granulate rather than smooth exoskeleton (cf. Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000, p. 212). Other granulate species of Meteoraspis include M. keeganensis Lochman in Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944 from Montana (Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 9, figs. 1–3, 29), M. borealis Lochman, Reference Lochman1938b from Montana and Newfoundland (Lochman, Reference Lochman1938b, pl. 56, figs. 1–5; Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 9, fig. 10; Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, pl. 70, figs. 3, 4), and M. delia Lochman, Reference Lochman1940 from Missouri (Lochman, Reference Lochman1940, pl. 3, figs. 14–20).

Family Crepicephalidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Remarks

Palmer (Reference Palmer1954b, Reference Palmer1962) and Pratt (Reference Pratt1992) discussed the diagnosis and scope of the family Crepicephalidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935 (=Coosellidae Palmer, Reference Palmer1954b), pointing out the similarities shared by the genera Crepicephalus Owen, Reference Owen1852, Coosia Walcott, Reference Walcott1911, Coosella Lochman, Reference Lochman1936, Coosina Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1956, and Syspacheilus Resser, Reference Resser1938.

Genus Coosia Walcott, Reference Walcott1911

Type species

Coosia superba Walcott, Reference Walcott1911 from the upper Guzhangian of Alabama and Tennessee, by original designation.

Coosia conicephala (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954) new combination

Figure 5.16, 5.20, 5.21

- Reference Rusconi1954

Querandinia conicephala Rusconi, p. 55, text-fig. 29.

Holotype

Small cranidium (MCNAM 17448) from La Cruz Olistoliths, 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro, Mendoza (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 29; Fig. 5.21).

Occurrence

Two hundred meters northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, upper Guzhangian, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Remarks

Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) erected Querandinia Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 and Q. conicephala Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 on the basis of only a tiny cranidium (holotype) that was originally illustrated with a line drawing (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 29). After its original description, the affinities of this specimen remained doubtful (Lochman in Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Henningsmoen, Howell, Jaanusson, Lochman and Moore1959, p. 525; Jell and Adrain, Reference Jell and Adrain2003). It shows a broad (sag., exsag.) and flat anterior border, a shallow anterior border furrow, a tapering, anteriorly rounded glabella, effaced glabellar lateral furrows, an almost straight occipital furrow, indications of backwardly oblique eye ridges, and moderately sized palpebral lobes located opposite the middle third of the glabella. Following the diagnosis of Palmer (Reference Palmer1954b, p. 730), this specimen is reinterpreted here as an early holaspid of Coosia Walcott, Reference Walcott1911, and Querandinia is suppressed as a junior synonym of that genus. Two additional, larger cranidia from the Rusconi collection (Fig. 5.16, 5.20) slightly differ from the holotype by showing more clearly curved anterior border furrows.

The variable species Coosia alethes (Walcott, Reference Walcott1911), from the Crepicephalus Zone of Montana, South Dakota, and Tennessee, includes some cranidia (e.g., Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1965, pl. 7, fig. 9; Lochman and Duncan, Reference Lochman and Duncan1944, pl. 6, fig. 2; Stitt and Perfetta, Reference Stitt and Perfetta2000, fig. 7.21) that have a certain similarity to C. conicephala, although the marginal border of the former, like that of many other species of Coosia, is less strongly curved forward. In this regard, “Coosella” sp. from the Cedarina dakotaensis Zone of South Dakota (Stitt, Reference Stitt1998, fig. 8.1) resembles, at first glance, the material from San Isidro but differs in having more anteriorly located palpebral lobes.

Genus Coosella Lochman, Reference Lochman1936

Type species

Coosella prolifica Lochman, Reference Lochman1936, from the upper Guzhangian of Missouri, by original designation.

Coosella texana? Resser, Reference Resser1942

Figure 5.17, 5.18, 5.22

Occurrence

Two hundred meters northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, upper Guzhangian, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Remarks

Some crepicephalid cranidia from the Rusconi collection exhibit a poorly convex, elongate, tapered, subconical glabella that is slightly constricted opposite palpebral lobes and rounded anteriorly, occupying more than three-quarters of the total cranidial length; faint indications of three pairs of lateral furrows; a distinct, flat occipital ring representing ~17% of the total glabellar length, lacking node or spine; an equally divided frontal area; a long (sag.), shallow anterior border furrow defining a slightly raised anterior border; a proportionately short (sag.) preglabellar field; and oblique, moderately developed palpebral lobes located slightly anterior to glabellar midlength. These features are characteristic of Coosella texana Resser, Reference Resser1942 as revised by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992, p. 65), from the Riley Formation of Texas (Resser, Reference Resser1942, pl. 13, figs. 21–24, pl. 14, figs. 2–5), the Warrior Formation of Pennsylvania (Tasch, Reference Tasch1951, pl. 46, figs. 13, 14), and the Rabbitkettle Formation of northwest Canada (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, pl. 22, figs. 17–20). As in the type cranidia from Texas (Resser, Reference Resser1942, pl. 13, fig. 23, 24, pl. 14, figs. 2, 3), the Argentinian material shows faint glabellar muscle scars that partly mask the lateral furrows and faint traces of radiating prosopon ridges on the preglabellar field. Still, there are no pygidia associated with this material, and it is cautiously classified in open nomenclature.

As stated by Pratt (Reference Pratt1992), C. texana differs from other species of Coosella mainly by having an elongate glabella.

Family Marjumiidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Genus Nasocephalus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954

Type species

Nasocephalus nasutus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954 from Cambrian clasts in Woods Hollow Shale (Middle Ordovician), Texas, by original designation.

Remarks

This genus is known from Cambrian boulders of the Woods Hollow Shale of Texas as well as from the Cedaria selwyni Zone of the Rabbitkettle Formation of the southern Mackenzie Mountains (Wilson, Reference Wilson1954; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992). One of its most characteristic features is an anterior cranidial border that is extended into a pointed snout having concave sides. Although such a feature is also present in Dokimocephalus Walcott, Reference Walcott1924 from the lower Jiangshanian Elvinia Zone and correlatives of Nevada, Utah, Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, Wyoming, and Pennsylvania (Walcott, Reference Walcott1924, Reference Walcott1925; Frederickson, Reference Frederickson1948; Palmer, Reference Palmer1960, Reference Palmer1965; Westrop et al., Reference Westrop, Poole and Adrain2010), Nasocephalus is easily differentiated by its poorly convex glabella, weaker lateral glabellar furrow S1, and molds lacking granular sculpture.

Nasocephalus cf. N. nasutus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954

Figure 5.19

Occurrence

Two hundred meters northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Description

A mostly exfoliated cranidium from the Rusconi collection exhibits a low, broadly tapering and anteriorly rounded glabella; dorsal furrows well defined, shallowing anteriorly; lateral glabellar furrows S1, S2, and S3 faint, slightly curved backward, disconnected at middle; preglabellar field short (sag.); anterior border furrow shallow and gently curved forward; anterior border extended into a partially preserved frontal spine; fixigenae moderately narrow (tr.), rising above the glabella; ocular ridges faint, narrow, oblique backward; palpebral lobes arcuate, inflated, elevated above ocular ridges, extended from the level of midpoint of L1 to the level of glabellar furrow S2. The dorsal surface is smooth, while a fragment of test retained on the anterior cranidial border is finely granulated.

Remarks

This morphology coincides to a large extent with that of Nasocephalus nasutus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, which has been originally described from only two cranidia and one librigena from an upper Guzhangian clast in Woods Hollow Shale (Middle Ordovician) of Texas (Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, pl. 24, figs. 14, 18, 19, 21; Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, p. 89). The Argentinian cranidium differs only slightly by having strongly arcuate rather than semicircular palpebral lobes.

Nasocephalus cf. N. nasutus is distinguished from N. flabellatus Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, from the Marathon Uplift of Texas (Wilson, Reference Wilson1954, pl. 24, figs. 3, 22) and the Cedaria selwyni Zone of the Rabbitkettle Formation, northwestern Canada (Pratt, Reference Pratt1992, pl. 18, figs. 11–20, text-fig. 34), mainly because the latter shows a more subrectangular glabella and longer (exsag.), slightly curved palpebral lobes.

Order Corynexochida Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Family Dorypygidae Kobayashi, Reference Kobayashi1935

Genus Olenoides Meek, Reference Meek1877

Type species

Paradoxides? nevadensis Meek, Reference Meek1870 from the Miaolingian of Utah, by original designation.

Remarks

Palmer (Reference Palmer1954a), Robison (Reference Robison1964b), and Sundberg (Reference Sundberg1994) discussed in detail the diagnosis of Olenoides, a well-known dorypygid genus that is widespread in the middle Cambrian of North America.

Olenoides proa (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954) new combination

Figure 5.23–5.25

- Reference Rusconi1954

Cancapolia proa Rusconi, p. 54, text-fig. 28.

Holotype

Cranidium (MCNAM 17445) from La Cruz Olistoliths, 200 m northwest of Estancia San Isidro, Mendoza (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 28; Fig. 5.23, 5.24).

Diagnosis

A species of Olenoides with a protruding anterior cranidial margin, a broad-based occipital spine, three pairs of distinctly marked pygidial pleural and interpleural furrows that are straight to slightly curved and become deeper and wider distally, and marginal spines of different sizes.

Occurrence

Two hundred meters northwest of Estancia San Isidro, San Isidro area, Mendoza, upper Guzhangian, La Cruz Olistoliths, Cedaria prolifica Zone.

Description

Cranidium showing a protruding anterior margin, a long, subrectangular, slightly expanding glabella reaching anterior border, effaced glabellar lateral furrows, and indications of a broad-based occipital spine. Glabella anteriorly fused with a large, concave, tongue-shaped frontal area of cranidium. Fixigenae moderately wide (tr.) and downsloping. Palpebral lobes medium in size and located opposite middle third of glabella.

Pygidium with a long (sag.) and slightly tapered axis, which displays four preserved rings and a broadly rounded terminal piece; axial rings lacking axial nodes; three pairs of distinctly marked pleural and interpleural furrows that are straight to slightly curved and become deeper and wider distally; a weakly defined pygidial border; and a partly preserved margin with at least three pairs of marginal spines having bases of different widths. Pleural fields have anterior pleural bands that expand (exsag.) laterally and posterior pleural bands that are uniform in width.

Remarks

Rusconi (Reference Rusconi1954) erected Cancapolia Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 and C. proa Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954 on the basis of only a dorypygid cranidium (holotype) that was originally illustrated with a sketch (Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, text-fig. 28). This specimen is redescribed in the preceding (emended from Rusconi, Reference Rusconi1954, p. 55) (Fig. 5.23, 5.24), together with a pygidium (Fig. 5.25) that is regarded here as conspecific. The general aspect of the cranidium as well as the pattern of pygidial pleural furrows and pleural bands (see Sundberg, Reference Sundberg1994) are compatible with the middle Cambrian genus Olenoides Meek, Reference Meek1877, so Cancapolia is suppressed as a junior synonym of it.

Olenoides is well represented in the Wuliuan, whereas it is rarer in upper Guzhangian strata. Two fragmentary pygidia of Olenoides sp. undet., from the Cedaria/Crepicephalus Zone of Tennessee (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1965, pl. 5, figs. 12, 13), differ from the material from San Isidro mainly by having more curved pleural and interpleural furrows. Olenoides? trispinus Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946 was based on two pygidia from upper Guzhangian conglomerate boulders from the Gaspé Peninsula in Quebec (Rasetti, Reference Rasetti1946, pl. 70, fig. 16) that are distinguished from O. proa by their much shallower pleural furrows.

Acknowledgments

G. Campos, E. Aranguez, and M. Parral (Museo de Ciencias Naturales y Antropológicas “Juan Cornelio Moyano,” Mendoza) are thanked for their technical assistance and for making the material available for study. F. Sundberg, S. Westrop, and an anonymous reviewer greatly helped to improve the manuscript. Financial support was provided by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas and the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina.

Declaration of competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.