INTRODUCTION

There has been a long history in economics of writing about capitalism but this has not been the case in strategic management, which is perplexing since strategic management draws heavily on economic principles to understand differential firm performance (Wernerfelt, Reference Wernefelt1984; Lockett & Thompson, Reference Lucas2001; Lippman & Rumelt, Reference Loasby2003; Mahoney & Pandian, Reference Mahoney and Pandian2006). Put another way, even though capitalism involves three interdependent, overarching ‘institutional clusters’, that is, ‘A. [a] monetary system for producing bank-credit money; B. marketFootnote 1 exchange; and C. private enterpriseFootnote 2 production of commodities’ (Ingham, Reference Jacobides, Winter and Kassberger2008: 53), relatively little has been done in strategic management to understand how all three clusters interact in system terms. In other words, the role managerial strategic decision-making affects the functioning of capitalist economies has been little explored.

Notwithstanding and more specifically, strategic management scholars have indeed exerted much effort to study C. in relation to B. For instance, they have extensively examined how transaction costs affect the make or buy decision, risk mitigation and governance under conditions of uncertainty (Coase, Reference Coase1937; Williamson, Reference Williamson1985, Reference Williamson1991a, Reference Williamson1991b; Conner & Prahalad, Reference Conner and Prahalad1996; Mahoney, 2001, Reference Mandle2005). Likewise, research continues to proliferate on the determinants of various kinds of investment and structuring patterns in different institutional systems, such as when there is a stakeholder or coalitional or social focus as opposed to a shareholder focus (Oliver, Reference O’Shannassy1997; Thomas & Waring, Reference Tirole1999; Williamson, Reference Williamson2000), pressure to conform (DiMaggio & Powell, Reference Doz and Kosonen1983; Brown & Deegan, Reference Brown and Deegan1998; Campbell, Reference Campbell2007; Peng, Sun, Pinkham, & Chen, Reference Peteraf2009), when there are stage of economic development concerns (Garcia-Pont & Nohria, Reference Garrouste and Saussier2002; Goerzen & Beamish, Reference Grant2005; Garcia-Canal & Guillen, Reference Garcia-Pont and Nohria2008; Capron & Guillen, Reference Capron and Guillen2009; Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin, & Shepherd, Reference Foss2009), and inconsistent regulatory or other protections present (Wholey & Sanchez, Reference Wiggins and Ruefli1991; Kim & Prescott, Reference King and Levine2005; Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik, & Peng, Reference Miller, Michalski and Stevens2009).

This paper argues the relative lack of a research agenda in strategic management which considers capitalism in system terms represents a lost opportunity that must be addressed for three reasons. First, capitalism rightly or wrongly has become firmly entrenched globally as the dominant economic system (Stiglitz, Reference Swedberg2012). Second, there is no such thing as ‘a single business model that is the most efficient for all sectors and countries’ even if this was once true (Whitley, Reference Wholey and Sanchez2009: 18). Indeed, firms are increasingly experimenting with new business models (Baden-Fuller & Morgan, Reference Baden-Fuller and Morgan2010; Chesbrough, Reference Chesbrough2010; Teece, Reference Thomas and Waring2010). There is also the question of whether the highly financializedFootnote 3 , ultraflexible US model should be emulated by other countries, since it does not always lead to capital flowing to those who can use it the most efficiently (Dore, Reference Durand, Grant and Madsen2008; Lehrer & Delaunay, Reference Lippman and Rumelt2009). The same goes for whether markets should always be the default system when making products and services available to consumers (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Winter2002). According to Langlois (Reference Lee and Makhija2003: 353, 378), managers are also now less relevant since organizations are increasingly outsourcing; Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ and then ‘the visible’ hand, as Chandler (Reference Chandler1990) termed it, is now best thought of as the ‘vanishing hand’. The implication is that individual managerial input has much less relevance than a few decades ago. There has been a notable shift towards multiple ‘actor-oriented architectural schemes’ (Fjeldstad, Snow, Miles, & Lettl, Reference Foss, Knudsen and Montgomery2012: 734).

Third, the global financial crisis (GFC) suggests the world’s economies are experiencing a ‘structural break from the past’, which in econometrics refers to ‘the moment in time-series data when trends and the patterns of associations among variables change’ (Rumelt, Reference Scherpereel2009: 35–36). Specific manifestations that have occurred in the last two decades and brought into high relief by the GFC include the shift from hierarchical models of organization and mass production methods to more complex knowledge-based, highly networked and technology-underpinned models of organization and production (Miller, Michalski, & Stevens, Reference Mintzberg, Simons and Basu1998), increasing inequality between those in the top 10% of populations as opposed to those in the bottom 10%, particularly as a result of disparities in income (Piketty, Reference Prahalad and Hammond2015), a marked reduction in total factor productivity (labour to capital) across the world, especially evident after the GFC (Castro, Reference Castro2013) and lower rates of world trade growth as a result of global supply chains expanding at a lower rate (Costantinescu, Mattoo, & Ruta, Reference Cyert, Kumar and Williams2015).

It is for these reasons this paper reviews the writings of three influential economists on the topic of capitalism, that is, SchumpeterFootnote 4 , FriedmanFootnote 5 and StiglitzFootnote 6 , Footnote 7 . The paper seeks to clarify how economists have traditionally approached capitalism and where scope exists for strategic management scholars to adjudicate on key points of contention and/or provide new insights. Though to a lesser extent, the paper also seeks to contribute to our understanding of the history and evolution of strategic management, particularly its possible future since by better understanding strategic decision-making we can better understand how firms can contribute to the betterment of society (O’Shannassy, Reference Ostrom2015). The reality is strategic management is a field where despite having a history of well over 50 years its key constructs are still being defined (Nag, Hambrick, & Chen, Reference Nelson2007; Ronda-Pupo & Guerras-Martin, Reference Rumelt2012); the nature of its evolution, including the pros and cons, are still being debated (Nerur, Rasheed, & Natarajan, Reference Nerur, Rasheed and Pandey2008; Nerur, Rasheed, & Pandey, Reference Nickerson and Zenger2016), to what extent strategic management problems are cross-sectional or longitudinal, such as when one attempts to examine the historical differences between the resource-based view and its successor the dynamic capabilities view (Hoskisson, Hitt, Wan, & Yiu, Reference Ingham1999; Galvin, Rice, & Liao, Reference Cwik2014; Arndt & Norbert, Reference Arndt and Norbert2015) and the boundaries of it as a disciplinary domain allowing for the fact that though less fragmented in terms of theoretical integration than it was before strategic management research still lacks consistency of measurement (Durand, Grant, & Madsen, Reference Fjeldstad, Snow, Miles and Lettle2017). Likewise, the origins of its dominant theory, the resource-based view, is still being debated, particularly the relevance and influence of Penrose and her work on the growth of the firm, as well as its implications on public policy as it pertains to patterns of firm growth and their greater effects (Blundel, 2013; Jacobsen, Reference Kim and Prescott2013). In the first section of this paper, Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz’s theories on the sources of economic growth under capitalism and the future of capitalism are discussed. In the second section, the differences between these economists are reduced to three questions and their potential implications for strategic management. The paper concludes that strategic management scholars are well placed to develop their own organization-centric discourse on the subject.

THE DRIVERS, BOOM AND BUSTS, CAPITALISM’S FUTURE, AND FIRMS

In his writings, Schumpeter argued savings, capital investment, money markets, entrepreneurship and business cycles enable capitalism (Swedberg, Reference Tan and Peng1991), that is, they make possible ‘new combinations of factors of production’ (Schumpeter, Reference Simon1991[1936]: 313). Entrepreneurs trigger off the change process by engaging in acts of creative destruction (Schumpeter, 1947a, 1947Reference Schumpeterb, Reference Schumpeter1961[1911]); and though booms and busts should be considered normal they instead create ‘abnormal’ panic (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1927: 307). Supernormal profits are unsustainable because they disrupt prevailing investment patterns (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1928, Reference Schumpeter1935, 1947a, Reference Schumpeter1961, Reference Simon2000) and, thus, require the ‘proper management of credit’ (Swedberg, Reference Tan and Peng1991)Footnote 8 .

In the second phase of his career, Schumpeter (Reference Shleifer and Vishny1979[1943]) argued the future of capitalism was dependent on how the credit system evolved. Using Marxian methodsFootnote 9 , he concluded that though capitalism’s future looked bright for now, it was inherently unstable because it was a social system that evolved organically; it was not the product of careful engineering (Swedberg, Reference Tan and Peng1991). The credit system was particularly unstable for these same reasons (Ingham, Reference Jacobides, Winter and Kassberger2008). Thus, it was inevitable socialism would replace capitalism in the same way capitalism had replaced feudalism. The transformation would occur in two phases. In the first, managers would usurp entrepreneurs. In the second, central authorities would replace managers because managers would put their own interests above those of shareholders (Schumpeter, Reference Shleifer and Vishny1979[1943])Footnote 10 .

In contrast to economists such as Friedman, Schumpeter did not view socialism as an anathema because democracy was not dependent on a particular economic system though it was dependent on the economic system, and visionary politicians would appreciate thisFootnote 11 . Neither did Schumpeter accept Marx’s thesis that capitalism’s demise would be the result of class warfare. He believed Marx’s theory of exploitation had ignored the fact that in competitive environments exploitation gains usually lead to an expansion of production that benefited workers too. Indeed, all classes in society benefitted. He believed monopolists were important for they could stabilize the economy after a period of disruption, creating templates for the efficient use of society’s resources that central authorities would use once socialism replaced capitalismFootnote 12 . Although difficult to predict when the latter would occur, it was likely to occur around the time share ownership became excessively diluted, taking ‘the life out of the idea of property’, which includes the instinctual urge to monitor one’s stake in a business (Schumpeter, Reference Shleifer and Vishny1979[1943]: 142).

Though a recipient of a Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on consumption (Friedman, Reference Gambardella and McGahan1976), Friedman is best known for his nontechnical work where he promoted his belief that capitalism works only if markets are free and unfettered by regulation and excessive taxes (Stiglitz, Reference Swedberg2012)Footnote 13 . Friedman is also well known for his belief that although government is sometimes needed to ensure a functional economy, government was best kept small (Rayack, Reference Ring, Bigley, D’Aunno and Khanna1987). He repeatedly argued government should be limited to the preservation of law and order, national defence, the enforcement of property rights, the maintenance of an efficient (competitive) market system and the investment in public goods and infrastructure. He also argued there is an ‘intimate connection between economics and politics’, that people’s buying patterns reflected what they wanted from the economy and politicians. This meant people were ill-advised to vote for politicians who wanted to redistribute wealth to promote equality since the market system could elevate the marginalized much more efficiently (Friedman, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao1962: 4, 7–8).

Friedman argued innovation was an important driver of capitalism. However, his take was different to that of Schumpeter: ‘In a capitalist society, it is only necessary to convince a few wealthy people to get funds to launch any idea, however strange, and there are many such persons’, the implication being wealthy investors were responsible for America’s wealth, not entrepreneurs, and governments are too constrained by political forces to contribute without creating ‘neighbourhood effects’ or forcing markets to homogenize (Friedman, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao1962: 17, 27).

Friedman believed socialism was incompatible with democracy because the market system always self-corrected and could reallocate society’s collective wealth efficiently. He was convinced the Government had in the 1930s prolonged the Great Depression by its mishandling of monetary policy and it was not caused by markets failingFootnote 14 . Consequently, he was against money supply decisions being left to individuals at the Federal Reserve (Friedman, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao1962: 48)Footnote 15 .

Friedman was very optimistic about the future of capitalism. He argued capitalism would thrive provided Government did not interfere in markets, labour accepted lower wages during bad times and firms focussed on maximizing shareholder wealth. He disagreed with Schumpeter that monopolies have an upside, arguing governments had an obligation to curtail anticompetitive practices, including those of unions and corporations. Friedman also had no doubt capitalism would continue to be subject to crises but did not believe the state of affairs could ever get so bad the people would seriously contemplate replacing capitalism with socialism (Friedman, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao1962).

Stiglitz is also a recipient of the Nobel Prize. He is mostly known for his work on information economics, models of competition and his criticism of economists who used scant evidence to promote neoliberal views (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz1991, Reference Stiglitz2001). Though proregulation, he is a strong advocate of capitalism. He believes capitalism works best when it rewards people equally for working hard, taking risks and innovating. He argued the GFC was caused by inequities creeping into the system and because financial deregulation had encouraged risky practices. This led to the recent implosion of the global economic system and the corporate bail-outs, tax monies not being invested in people, infrastructure and technology as it should have been (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2010).

Just as Schumpeter had done, Stiglitz rejects the perfect competitive markets assumption, including Friedman’s arguments that people are almost always better off when equilibrium is reestablished after a downturn, though he agrees with Friedman that Schumpeter was wrong to say that monopolies have an upside (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2010). This is not to say that Stiglitz agrees with Schumpeter that socialism will eventually replace capitalism and profit maximization makes capitalism work efficiently. The GFC has shown that capitalism malfunctions if it is based on ‘trickle down’ economics, including policies based on the assumption that labour markets must be ultraflexible because shareholders should never be expected to sometimes accept lower profits:

Giving more to the rich leads to a larger pie … I wish that were so, but it’s not. In fact, it’s the opposite … the slice given to most Americans has been diminishing (Stiglitz, Reference Swedberg2012: 7).

On the subject of capitalism’s future, Stiglitz is certain it will prevail but he is adamant the present system needs fixing: ‘Any economic system has to have rules and regulations … inequality gets reflected in every important decision that we make as a nation’ (Stiglitz, Reference Swedberg2012: xix–xx). He believes global accords are more necessary than ever and scope exists to drastically improve how organizations are financed, governed and designed, confirming that a ‘modern theory of the firm in turn rests on three pillars, the theory of corporate finance, the theory of corporate governance, and the theory of organizational design’ (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2001: 508).

HOW CAN MANAGEMENT SCHOLARS CONTRIBUTE TO THE DISCOURSE?

The preceding draws attention to the fact that Schumpeter and Stiglitz disagree with Friedman in regard to one critical point. They do not agree markets are always efficient and governments should never intervene in them. Thus, Schumpeter and Stiglitz believe perfectly competitive markets are the exception and not the rule, and that free markets through the notion of the consumer’s right to choose are not easily linked to the notion of democracy or freedom. However, only Schumpeter believes capitalism will eventually evolve into socialism.

The three themes these economists explore in common are (1) capitalism’s most essential institutional drivers during the different stages of the economic cycle; (2) the future of capitalism; and (3) the role firms play in capitalist societies. If strategic management scholars are to contribute to the discourse on the topic of capitalism, including what is good and what is bad about capitalism, how it should and will most likely evolve, they will need to (1) identify the kind of research questions strategic management scholars are equipped to answer, and (2) what are the best methodologies to use to study them. This is within the context that to date strategic management scholars have not had a lot to say about capitalism despite drawing heavily on concepts first developed by economics, such as uncertainty, information asymmetries, bounded rationality, opportunity, asset specificity and various theories of the firm (Rumelt et al., 1991: 14). Thus, it makes sense to discuss what three prominent economists have had to say about capitalism, as this paper has done, and use some of their more interesting insights on the topic of capitalism as a starting point for discussion. There are certainly at least six issues that Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz raised when writing about capitalism strategic management scholars are well equipped to provide more granular insights.

The drivers of growth

This paper highlighted the fact that, although overlapping at times, Schumpeter, Friedman and Stigltiz explained what predominantly drives growth differently. Schumpeter attributed growth to the fact entrepreneurs innovate and this leads to increased business activity. Friedman attributed growth to the fact that competition gives people choice. When people are free to start businesses and markets become more pluralistic, diverse, this leads to even greater levels of opportunity, which leads to more business activity. Stiglitz believes growth is driven by all these things but is adamant economic growth and sustained levels of growth would not be possible without the support of an effective capital market system. If strategic management could adjudicate to some extent here how can it do so?

First, scholars would have to find ways to define firm growth as the result of innovation, pluralism in markets, ready access to capital or some combination of these things. Second, they would then have to find effective proxies or measures of these phenomena. Third, they would need to identify suitable units of analysis, for instance, certain groups of firms or industries. Fourth, they would need to determine if one of the abovementioned drivers tends to explain firm growth more than others. Fifth, if there is a dominant driver, they would need to determine if the group’s growth performance reflects economic growth generally. Sixth, if there is a correlation, then they need to find a way to validate it. Seven, if validated, scholars would then be required to demonstrate under which circumstances the findings hold true over time.

This is just one set of suggestions for how strategic management scholars might be able to provide more insight into the question of what drives growth. No doubt there are potentially many more. The important point is that if capitalism is in question and economists cannot even agree on something as fundamental as what sets of mechanisms drives growth then they are going to be hard pressed to proffer solutions for how capitalism should be evolved, that is, turned into something that everyone benefits from and that is not so characterized by boom and bust periods.

Boom and bust periods

As Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz all highlighted, capitalism is characterized by boom and bust periods. However, in regard to the causes of these peaks and troughs, this is another area where these three economists do not agree. Schumpeter believes peaks and troughs are the result of the process of creative destruction. Friedman believes the economy would work smoothly if governments just stopped behaving in ways that interfered with it. Stiglitz believes boom and bust periods are primarily caused by imperfections in capital markets, although it is not limited to this.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to go into detail, strategic management could provide more insight into what is involved here. For instance, they could learn more about what influences managers’ investment decisions prior to and during a boom, and during bust periods, and as the economy recovers. For instance, do managers predominantly rely on different sources of information or market signals at different times? Is it possible ‘good’ investment decisions or, as the case may be, ‘bad’ investment decisions could be attributed more so to the process of creative destruction, government policy or effective capital markets, then it may be possible to understand in what ways potentially extremely harmful bust periods can be avoided in the future.

The perfect market assumption

Schumpeter and Stiglitz have argued that perfect markets are more the exception than the norm, which means they are not always self-righting, while Friedman believed markets are efficient, and they will clear and establish/reestablish equilibrium in time; thus, other than discouraging anticompetitive behaviour, governments were best advised not to interfere in their running by doing such things as regulating them. It follows if economists have different views on this matter, managers could be similarly divided. Among other things, this would suggest that strategic management scholars could provide some very useful insights here by learning about the ways in which managers apply the perfect market assumption and how they perceive the government, identifying the firm-level and economy-level effects of same.

On government stimulus and bail-outs

Schumpeter and Stiglitz have very similar views on whether governments have a role to play in ensuring the smooth running of the economy. They both argued that when the economy is in recession it is appropriate for the government to intervene. This includes providing support to banks if they need help. In contrast, Friedman believed governments should as a rule let markets sort themselves out. Strategic management scholars could again provide some of the answers here by doing such things as conducting detailed and/or longitudinal case studies of how firms are affected by stimulus programmes and bail-outs, including in what ways they were able to build new or improved capabilities or not, or solve or pre-empt serious agency problems, and what institutions affected them most.

Systemic risk and risk capital

It is clear that Schumpeter and Friedman have not been as articulate on the topic of risk as has been Stiglitz, although they certainly did understand and highlighted the fact that risk is an important part of the capitalist experience, very much tied to the rewards that capitalism can bring forth. They also appreciated that if the banks got into trouble, it could be at times appropriate for the Government to provide capital injections. It follows, strategic management scholars could provide more insight into how risk is conceptualized and handled by firms and, thus, across the economy by identifying how decision-making can be affected by one’s perception of risk, particularly systemic risk and how it can be mitigated by the accumulation of risk capital. Such studies should not be limited to the financial sector and should examine how these risk concepts are treated at firms from all industries and sectors. The reality is that very little is known about how systematic risk and risk capital are considered as part of firms’ strategies, and their flow-on effect on the economy and society.

Firms and the social fabric

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, since capitalism is under question on all variety of fronts it is interesting to consider why Schumpeter was so sure capitalism would evolve into socialism, Friedman so sure that people could not prosper or live freely without it and Stiglitz adamant that there is enough evidence to demonstrate that capitalism can work but not if its institutions are hijacked by vested interests and society becomes more unequal as a result. This is over and above considering the major events of their times.

Traditionally, strategic management has not had much to say about how firms affect the social fabric, lead to peoples living better or worse lives as a result of the business activities of firms. But the reality is society is influenced by the economic reality (Schumpeter, Reference Shleifer and Vishny1979[1943]) and firms are very much a part of the economic reality. This would suggest that strategic management scholars need to expend much more effort in the future to understand how firms positively and negatively impact people’s lives. In fact, one could argue that they should be a little more like Schumpeter who believed history, society’s institutions and the social aspects of economics should be of great interest. Thus, it could be that some of the traditional tools of the historian and sociologist need to be adopted by strategic management scholars.

The above suggests strategic management could contribute to the discourse on capitalism by addressing the following three overarching questions, each providing a frame by which to articulate specific research propositions as they relate to individual firm performances and, in turn, play a part in growing or contracting the economy as part of a capitalist system:

1. What investment decisions do entrepreneurs, managers, owners and directors make during different stages of the economic cycle?

2. How are the different institutions of capitalism affected by organizations taking actions to respond to periods of market instability or markets radically changing?

3. Can strategic management ‘modernize’ the theory of the firm by integrating and applying corporate finance, corporate governance and organizational design theory to this end?

Firms in the chain of causality for growing, contracting and transforming

Schumpeter believed economic growth within capitalism is the result of entrepreneurs innovating and changing investment patternsFootnote 16 ; Friedman believed growth occurs because markets are competitive and diverse, and can self-correct; and Stiglitz believes though innovation and competition are necessary, economies cannot operate efficiently or grow without an institutional environment that promotes the right behaviours. Though the differences between these economists seem slight, the implications for strategic decision-making are potentially enormous, that is, depending on which economist’s argument has the most applicability at the time. This suggests strategic management could adjudicate by learning more about the strategies adopted by organizations at different stages of the economic cycle, the long-term effects of downturns on organizations, and how organizational decision-makers are addressing the inequities and impacts that their decisions are creating.

Generally speaking, few studies examine the strategies adopted by organizations during different stages of the economic cycle. One of these found that liquidating assets to improve the firm’s cash-based prospects is easier said than done, as some assets cannot easily be separated from others due to ‘specificity, complementarity and substitutability’ factors (Cwik, Reference Cyert and March2008: 67). Another found that at the height of the GFC, some firms actually increased innovation spending because they had slackFootnote 17 , their boards were committed to innovation and CEOs had a good track record of successfully innovating (Zona, Reference Zubac, Hubbard and Johnson2012). Likewise, Lee and Makhija (Reference Lehrer and Delaunay2009), found internationalized firms were able to respond flexibly to the GFC because they had positive past internationalization experiences and could draw on the option value associated with those past investments.

Research investigating the potential upside to downturns is also limited. Studies so far have sought to understand the implications of managers having a short-term as opposed to a long-term performance orientation, and how these orientations manifest, such as in family business which require high levels of commitment even during bad times while maintaining market discipline (Barton, Reference Barton2011). Similarly, although research on business models has proliferated (Baden-Fuller & Morgan, Reference Baden-Fuller and Morgan2010; Chesbrough, Reference Chesbrough2010; Demil & Lecocq, Reference DiMaggio and Powell2010; Doz & Kosonen, Reference Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin and Shepherd2010; Gambardella & McGahan, Reference Garcia-Canal and Guillen2010; Teece, Reference Thomas and Waring2010), very little has been done to understand in what way new models were stimulated by a downturn or other economic cycle factors and this presents strategic management with numerous opportunities (Chau, Thomas, Clegg, & Leung, Reference Chau, Thomas, Clegg and Leung2012).

The same applies to the question of how organizations use society’s collective resources, that is, how strategies are developed to address institutional diversity, particularly ‘the commons’, recognizing that there is ‘immense diversity of regularized social interactions in markets, hierarchies, families, sports, legislatures, elections, and other situations to identify universal building blocks used in crafting such structured situations’ (Ostrom, Reference Pack2005: 5) As Fjeldstad et al. observed, the managers of firms continue to experiment with new organization designs as the institutional matrix within which their firms continue to evolve and diversify:

[Many of] these new designs are based on an actor-oriented architectural scheme composed of three main elements: (1) actors who have the capabilities and values to self-organize; (2) commons where the actors accumulate and share resources; and (3) protocols, processes, and infrastructure that enable multi-actor collaboration (Fjeldstad et al., Reference Foss, Knudsen and Montgomery2012: 734, 745).

It begs the question, particularly post-GFC, whether there should be a fourth design element, that is, critical public goods. If firms are becoming less hierarchical and increasingly encourage self-organization, and some firms are capable of impacting whole systems by their actions (e.g., the financial system), logic suggests it will become necessary to learn more about the interplay between decision-making from the focal firm’s view only and from the view that the firm is part of a system and required to work in concert with other institutions to achieve common objectives (such as, stability in the system of banking). For instance, rather than viewing the causes of the GFC primarily through an agency lens, its causes could be explored by considering whether there were failures to define the ‘boundary conditions’ of the economic system. It could also be useful to apply harvest decisions logic, since the financial system is a common resource much like fisheries, forests and roadways, which require the imposition of incentive schemes that promote the right values while acknowledging individualistic, competitive, cooperative and altruistic attitudes (Hine, Gifford, Heath, Cooksey, & Quain, Reference Holburn and Vanden Bergh2009).

It is also well established that the economic system will be changed by the political system if it does not lead to people becoming better off (Schumpeter, 1947a; Friedman, Reference Galvin, Rice and Liao1962; Stiglitz, Reference Swedberg2012). This has not escaped those studying organizations, with many studying how organizations are creating and appropriating value while taking the needs of all stakeholders into account (Prahalad & Hammond, Reference Rayack2002; Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, Reference Aguilera, Rupp, Williams and Ganapathi2007; Bies, Bartunek, Fort, & Zald, Reference Bies, Bartunek, Fort and Zald2007; Campbell, Reference Campbell2007; Bruton, Reference Bruton2010). The challenge for strategic management is to find ways to understand how firms contribute to or redress inequality by pursuing equality-related strategies or not (Mintzberg, Simons, & Basu, Reference Nag, Hambrick and Chen2002; Barton, Reference Barton2011). By the same token, as identified in the growing varieties of capitalism literature, there is no one kind of capitalism and this has very important consequences for organizations everywhere (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Acemoglu & Johnson, Reference Acemoglu and Johnson2005; Holburn & Vanden Bergh, Reference Hoskisson, Hitt, Wan and Yiu2008; Hall Reference Hankcke2009; Hankcke, Reference Heertje2009). Thus, scope yet exists to shed ‘new light on how strategic thinking and practice might differ for large multinational firms in a dynamic market context’ (Witcher & Chau, Reference Zingales2012: S70).

The evolution of capitalism from an organization view

Schumpeter and Stiglitz argue perfectly competitive markets are more the exception than the rule while Friedman believes markets always self-correct and become more efficient over time. Notwithstanding, they all agree that capitalism’s evolution depends on how markets change or, more precisely, what happens when markets begin to address society’s production, consumption and wealth requirements much differentlyFootnote 18 .

This raises two questions for scholars bearing in mind strategic management has already rejected the notion that managers have perfect knowledge (Simon, Reference Simon1955, Reference Solow1979, Reference Solow1993; Cyert & March, Reference D’Aveni1965; Cyert, Kumar, & Williams, Reference D’Aveni, Dagnino and Smith1993; Conner & Prahalad, Reference Conner and Prahalad1996; Grant, Reference Grossman and Hart1996; Hoskisson et al., Reference Ingham1999), contracts can be complete (Coase, Reference Coase1937; Williamson, Reference Williamson1985), and an economy is only good for firms when markets are in equilibrium (Nelson & Winter, Reference Nelson1975, Reference Nelson1982a, Reference Nelson and Winter1982b; Schumpeter, Reference Shleifer1989[Reference Schumpeter1937]; Barney, Reference Barney1991; Robins, Reference Romer1992; Amit & Schoemaker, Reference Amit and Schoemaker1993; Peteraf, Reference Piketty1994; Lockett & Thompson, Reference Lucas2001). First, how do organizations cope with market frictions and, second, how is hypercompetition affecting firm evolution?

Mahoney and Qian (Reference Mahoney and Qian2013) recently published a paper that examined the potential importance of market frictions to management scholarship. Taking the view that cost minimization and value creation are substitutes for each other, and value capture complements value creation, they suggest since markets-based decisions are normally made under conditions of uncertainty, theories could be developed using market frictions as the unit of analysis and, in fact, different combination of market frictions may be appropriate to focus on and studyFootnote 19 . Likewise, real options logic implies a market friction perspective.

The real options perspective … contributes to designing operational solutions to market frictions (e.g., dealing with spillover effects that would otherwise be improperly priced) for the purpose of value creation and value capture. Specifically, calculating the option value to defer addresses the market friction of uncertainty in investment decisions, calculating the abandonment option addresses the market friction of the level of (in)flexibility in strategic choice, and calculating growth options addresses interproject and intertemporal spillovers in the presence of market frictions (Mahoney & Qian, Reference Mahoney and Qian2013: 6).

Indeed, as the authors suggest, strategic management could benefit immensely if different organizational economic theories were joined and then analysed but also different market frictions joined and then analysed to discover new theories altogether. Put another way, when there is evidence that the ability to trade or make products/services available is not seamless, it is important to understand which combination of transaction costs and other such factors play a role and to what extent they make it possible to benefit or not from disequilibrium, and different theoretical lenses should be used to understand the effect on performance, such as the lens of the resource-based view or agency theory. A corollary is that one could also gain insight into the forces that lead firms to move towards or away from a position approaching equilibrium, such as the bargaining process, and, in turn, gain insight into the microfoundations of resource accumulation (Wernefelt, Reference Whitley2013).

In regard to hypercompetition, it seems Schumpeter was prescient – competitive advantages are extremely difficult to sustain when new technologies are constantly introduced (D’Aveni, Reference Demil and Lecocq1994; Wiggins & Ruefli, Reference Williamson2005; Chen, Lin, & Michel, Reference Chen, Lin and Michel2010; D’Aveni, Dagnino, & Smith, Reference Davis, Diekmann and Tinsley2010; Jacobides, Winter, & Kassberger, Reference Jacobsen2012; Nelson, Reference Nerur, Rasheed and Natarajan2012). Hypercompetition is an issue for organizations and, in turn, capitalism because it means managers must consider (1) the sequence of advantages to pursue over time, (2) how such advantages might be pursued by other industry players (competitors), (3) how temporary advantages should be conceptualized to achieve sustained advantages in core competency or new business model terms (Wiggins & Ruefli, Reference Williamson2005) and (4) competitor dynamics in the pursuit of firm-specific objectives (Chen & Miller, Reference Chen and Miller2015). Indeed, the way in which a sector evolves may be more important in the long-run than how firms sustain advantages through capabilities and out-manoeuvring the competition (Chen, Lin, & Michel, Reference Chen, Lin and Michel2010; Jacobides, Winter, & Kassberger, Reference Jacobsen2012).

Importantly, hypercompetition as Schumpeter first conceptualized it, though useful, did not reflect an appreciation of ‘the complex intertwining of modern technology and science, or the rich and variegated set of institutions involved’. The reality is that most capitalist economies are mixed market and institutionally thick, that is, ‘much more “socialized” than Schumpeter envisioned’ and scope exists to tinker with the engine along these lines, particularly to eliminate the waste that can be associated with industry evolution (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Winter1990: 62–63, 67). The challenge for strategic management is to better understand how market weaknesses are being compensated for by different business, economic, social and political policies, and different actors, including governments, banks, labour organizations, educators and technology transfer systems (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Winter1990, Reference Nerur, Rasheed and Natarajan2012; Mahmood & Rufin, Reference Mahoney2005; Ring, Bigley, D’Aunno, & Khanna, Reference Robins2005).

Towards a ‘modern’ theory of the firm

The preceding sections suggest that there is a basis for arguing organizations (1) do not operate in frictionless markets under capitalism, and (2) they are an integral part of the ‘engine’ of growth. This has not escaped Stiglitz who argued the ‘modern theory of the firm … rests on three pillars, the theory of corporate finance, the theory of corporate governance, and the theory of organizational design’ (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2001: 508). Stiglitz was not just saying theory of the firm research could be improved but that by better understanding firms within capitalism, capitalism could be made to work as it should, efficiently and equitably, and the risk of it catastrophically failing could be much reduced.

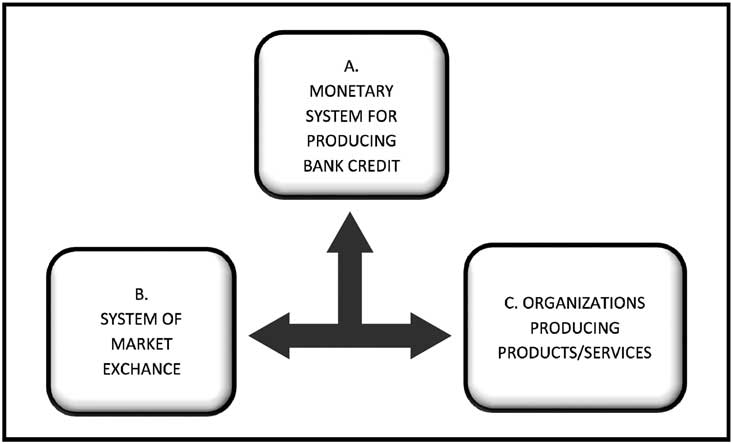

This has important implications for strategic management if we consider capitalism as involving three ‘institutional clusters’, that is, ‘A. [a] monetary system for producing bank-credit money; B. market exchange; and C. private enterprise production of commodities’ (Ingham, Reference Jacobides, Winter and Kassberger2008: 53), as described in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The three overarching institutions of capitalism

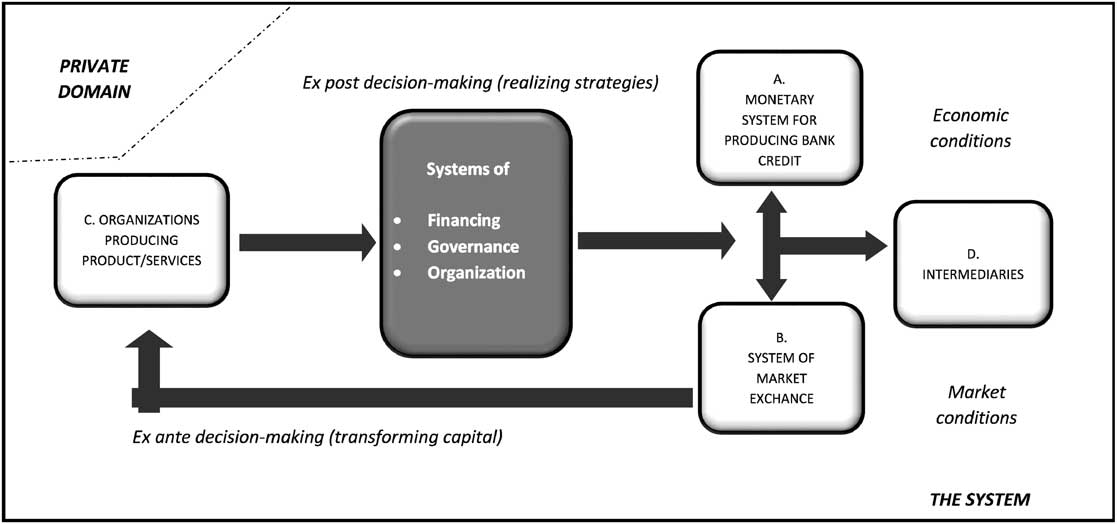

Though tempting to treat these clusters as ‘black boxes’ they are not, and involve subinstitutions that contribute to growth (Lucas, Reference Madhok1988). These are dependent on organizations’ systems of financing, governance and organization, which are concerned, respectively, with the way firms are financed (Zingales, Reference Zona2000; Tirole, Reference Vaara and Durand2006), how those who provide finance are assured of a return and stakeholders satisfied (Shleifer & Vishny, Reference Schumpeter1997; Tirole, Reference Tirole2001; Williamson, Reference Williamson2007), and how finance is translated into specific value creating and value appropriating resources, including projects, operations and decision-making structures (Robins, Reference Romer1992; Davis, Diekmann, & Tinsley, Reference Dierickx and Cool1994; Wang, He, & Mahoney, Reference Weigelt and Miller2009; Williamson, Reference Witcher and Chau2010; Waddell, Cummings, & Worley, Reference Wang, He and Mahoney2011; Foss, Lyngsie, & Zahra, Reference Friedman2013; Weigelt & Miller, Reference Wernerfelt2013). In other words, the three institutional clusters are able to interact because within them are distinct models of investing which are self-perpetuating and an integral part of the circular investment process, as first discussed by Schumpeter (1947a) and, more recently, the endogenous growth theorists in economics (Solow, Reference Schumpeter1956, Reference Stiglitz1994; Arrow, Reference Arrow1962; Lucas, Reference Madhok1988; Romer, Reference Ronda-Pupo and Guerras-Martin1990; King & Levine, Reference Krugman1993; Pack, Reference Peng, Sun, Pinkham and Chen1994; Agarwal, Audretsch, & Sarkar, Reference Agarwal, Audretsch and Sarkar2007), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Firms (organizations) within a ‘modern’ capitalist system

Moving from left to right across Figure 2, it is logically inferred organizations come into existence to make available products and/or services, and because the products and/or services cannot be viably produced within the private domain by individuals due to the level of complexity and scale involved, including the assets, capabilities and contracts required. The implication is that an organization is not an entity in any real conceptual sense until financing, governance and organization decisions are made and implemented (ex post) of formationFootnote 20 . Such decisions must be realizable so that the organization can justifiably transact with other organizations (or in markets). However, as shown in Figure 2, these decisions cannot be divorced from the decisions that must be made (ex ante) by managers/entrepreneurs and the providers of capital about how capital invested in the firm is to be transformed, since these decisions must be made, in an essential sense, simultaneously or close enough to it. This will be the case even if the organization is very small and the entrepreneur has only time and no money to invest, and bank credit (finance) is not in the first instance being sought. The reality is that an organization cannot form and then become a going concern (survive) unless it shows some promise of achieving its performance objectives, in effect playing its part in perpetuating the system of market exchange and the system of credit (investing) by representing value and the potential to increase in value. This set of inherently circular codependent relationships is the essence of capitalism. Importantly, law makers and organizational intermediaries, such as banks have evolved to complement this process (Ingham, Reference Jacobides, Winter and Kassberger2008).

The implication is that when conceptualized as such, strategic management research could be advanced in two ways, that is, by shedding light on how (1) theories of the firm already used in strategic management could be enhanced or better integrated to explain firms as part of the whole system of capitalism, and not just in relation to markets; and (2) entirely new theories of the firm could be developed that are specifically focussed on explaining firm existence and capitalism’s self-perpetuating cycles of growth over time. In both cases, systems of corporate finance, corporate governance and organization are critical to consider.

In regard to the first proposed research agenda, this represents a much-needed opportunity to integrate core assumptions from the various theories of the firm (Foss, Knudsen, & Montgomery, Reference Foss, Lyngsie and Zahra1995; Foss, Reference Friedman2003) and definitively explain firm existence and limits to scope (Garrouste & Saussier, Reference Goerzen and Beamish2008). For instance, although transaction cost economics is an economic foundation of strategy (Mahoney, Reference Mandle2005) and has been used to explain resourcing and contracting decisions, particularly the make or buy decision, rendering transaction cost theory essentially a theory of market failure and organizational hierarchy (Coase, Reference Coase1937; Williamson, Reference Williamson1975, Reference Williamson2002; Conner & Prahalad, Reference Conner and Prahalad1996; Nickerson & Zenger, Reference Oliver2008), much scope still exists to understand transactions and the contracts they stimulate when dealing with assets in environments of high risk and uncertainty (Argyres, Reference Argyres1996; Brahm & Tarzijan, Reference Brahm and Tarzijan2014), that is, to combine transaction cost economics and resource-based logic (Madhok, Reference Mahmood and Rufin2002; Mahoney & Pandian, Reference Mahoney and Pandian2006; Mayer & Salomon, Reference Mayer and Salomon2006). Towards this end, one would need to examine the typologies (or configurations) of corporate financing, corporate governance and organization firms adopt to be able to gain access to capital, transform themselves and, at the same time, satisfy a range of stakeholders when contracts are incomplete, including implicit contracts are in place (Tirole, Reference Tirole2001; Williamson, Reference Williamson2007; Teece, Reference Thomas and Waring2010).

An implication is that if transaction cost theory is a theory of market failure then it is incomplete and needs to be complemented by a theory of market perpetuity of some kind, bearing in mind that buyers and sellers (markets) are constituted by firms or close approximations to firms. Similar principles apply to other theories of the firm, such as Nelson and Winter’s (Reference Nelson1975, Reference Nelson1982a, Reference Nelson and Winter1982b) evolutionary theory and Cyert and March’s (Reference D’Aveni1965) behavioural theory of the firm. These theories could be rendered more complete too if considered from a corporate finance, corporate governance and organization within capitalism typological overlay.

In regard to the second proposed research agenda, new theories of the firm continue to emerge and these could have the ability to explain how firms cope with market failures and justify their existence by perpetuating the market system. For instance, firms can also be conceptualized as an ‘option-creating institution’ (Scherpereel, Reference Schumpeter2008: 455). Not only do they pursue opportunities while balancing risk, they attempt to unravel and benefit from discovering and exploiting uncertainty’s upside by implementing certain strategies and governance structures.

In another nascent theory of the firm, firms are defined in resource-investment terms with an emphasis on the role of managers and owners (investors). It argues firms exist ‘to satisfy the payment demands of owners’ (Zubac, Hubbard, & Johnson, Reference Costantinescu, Mattoo and Ruta2012: 1885). Thus, when firms are used instead of/or in preference to markets it is because they are deemed to have more capacity to satisfy capital owners’ payment demands. Likewise, since firms are dependent on a circular investment process that engages both managers and the owners of capital, firm scope is thereby ‘limited by the ability to attract and retain capital, and the related ability [of the firm] to perform’. The advantage of this theory of the firm is that it allows one to study how firms of all kinds and at all stages grow and evolve their resource base but also how markets evolve, including how they changed, dissolved and/or morphed into something else altogether over time.

CONCLUSION

This paper argues that considerable scope exists for management scholars to contribute to the discourse on capitalism – that the topic of capitalism and its future is not just the domain of economists and other social scientists. This is because (1) capitalism is now the dominant economic system, (2) firms continue to exhibit a propensity to adopt radically new modes of organizing and governance and (3) the recent GFC has led to a great many people to seriously question whether capitalism should exist in certain forms at all. To this end, this paper specifically identifies areas where management scholars could contribute and in what ways they could begin the process of developing a coherent theory (or theories) of capitalism, including a theory (or theories) which management scholars and managers more generally could find useful.

The first half of the paper describes the views Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz had on the topic of capitalism and its future, as expressed through some of their more well-known publications. The objective of summarizing these works was to identify where points of contention exist between these economists as it pertains to their contributions to discourse on capitalism but also to identify where management scholars could provide clarity. Two sets of questions were identified as being important to these economists: (1) what are the most important driver(s) of growth in a capitalist system; and (2) the future of capitalism.

The paper explained these three economists all agree that major events in history and powerful institutions not only made capitalism possible but have shaped its evolution and will in all likelihood continue to shape its evolution. However, it identified that Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz differ in regard to whether or not markets should be kept as free and as unregulated as possible, and the economic system as unmixed as possible, with Friedman being the main advocate for markets being left alone by governments and markets established as the default governance system when it comes to making decisions about how best to allocate society’s collective resources. Underlying Friedman’s logic was the belief markets have an uncanny ability to self-correct after a downturn and, in fact, often operating even more efficiently after a downturn. Schumpeter and Stiglitz, on the other hand, did not believe this and both were advocates of governments intervening in the market system when it was necessary.

As a result of Friedman believing that perfect market principles are inherently correct, Friedman had no doubt capitalism had a bright future provided governments did not interfere in the market system. However, Schumpeter and Stiglitz were much more circumspect. Schumpeter was more extreme and argued economic and political crises would ultimately lead to capitalism evolving into socialism (though still democratic) while Stiglitz argues there is evidence enough that capitalism worked provided it was inherently fair. This means governments sometimes need to intervene in the system and it is most likely capitalism will evolve to be heavily mixed market.

Thus, this paper identifies the three fundamental questions that underpin the writings of Schumpeter, Friedman and Stiglitz, and which management scholars could further research. As to the first question, the paper argues considerable scope exists to learn more about firms and their strategies during different stages of the business cycle; the effects of booms and busts; whether people and firms in particular are better off after a downturn; whether commons logic, as Fjeldstad et al. (Reference Foss, Knudsen and Montgomery2012) described it, can be applied to certain systems, such as the financial system; and the problem of increasing inequality from a firm perspective. As to the second question, considerable scope exists for management scholars to learn more about the relevance of the perfect market model assumption, including the reality of market frictions (Mahoney & Qian, Reference Mahoney and Qian2013); the consequences of markets everywhere becoming hypercompetitive and/or firms pursuing temporary competitive advantages; and firms within a mixed market and organizational diverse economic system. As to the third question, considerable scope exists for management scholars to learn more about how the three pillars of a modern theory of the firm could advance theory of the firm research, including lead to the development of new theories of the firm and market perpetuation, the latter complementing theories of market failure.

In summary, allowing for the fact that economics still relies heavily on the analysis of aggregated data using regression techniques and econometric modelling, and that even economists cannot agree on some very fundamental questions – what is the root growth in the chain of causality, to what extent is the perfect market assumption still relevant and what a modern theory of the firm should describe exactly – there can be no doubt that management scholars are extremely well placed now to contribute to the discourse. Importantly, management scholarship has advanced enough that it may even be possible for management scholars to develop their own theory (or theories) of capitalism, answering calls ‘to connect strategy research to the issues that matter’, among other things (Vaara & Durand, Reference Waddell, Cummings and Worley2012).

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Dr. Timothy O’Shannassy and Dr. Tui McKeown, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.