Introduction

Dementia is a condition affecting neurological functioning, which involves an acquired loss of cognitive abilities (Arvanitakis et al., Reference Arvanitakis, Shah and Bennett2019). Depression and anxiety are common amongst people with dementia (Kane and Terry, Reference Kane and Terry2015), and are linked to poorer outcomes, such as increased dependence, reduced quality of life, worsened cognition and mortality rates (e.g. Rozzini et al., Reference Rozzini, Chilovi, Peli, Conti, Rozzini, Trabucchi and Padovani2009; Rapp et al., Reference Rapp, Schnaider-Beeri, Wysocki, Guerrero-Berroa, Grossman, Heinz and Haroutnian2011). As there is currently no cure for dementia, providing non-pharmacological and individualised support is imperative (Aminzadeh et al., Reference Aminzadeh, Byszewski, Molnar and Eisner2007). Treatment of any symptoms of anxiety or depression should be seen as an essential component of dementia management (Azermai et al., Reference Azermai, Petrovic, Elseviers, Bourgeois, Van Bortel and Vander Stichele2012). Subsequently, depression and anxiety have been identified as specific targets for psycho-social interventions (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Sommerlad, Lyketsos and Livingston2015).

Most people with dementia are community-dwelling and receive care from a relative (Alzheimer's Research UK, 2014). While there are positive aspects of caring, care-givers for people with dementia often experience strain, psychological and physical illness (Safavi et al., Reference Safavi, Berry and Wearden2017), as well as negative impacts on their quality of life (Garre-Olmo et al., Reference Garre-Olmo, Vilalta-Franch, Calvo-Perxas, Turro-Garriga, Conde-Sala and Lopez-Pousa2016). These problems are often exacerbated as care-givers’ health needs are unmet, usually due to the demanding nature of care-giving (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, You and Tatangelo2016). Thus, supporting care-givers’ psychological health has been drawing increasing attention.

Counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions are one form of post-diagnostic support that can be offered to both people with dementia and their care-givers. This involves regular conversation between an individual and a counsellor/therapist, usually for a set number of sessions, and can impact on how individuals respond to their diagnosis and experience of dementia (Bryden, Reference Bryden2002). By understanding dementia as psycho-social, symptoms such as anxiety and depression are seen as responses to experiencing cognitive decline, which can be targeted through counselling and/or psychotherapy (Bryden, Reference Bryden2002).

Previous literature has reported that counselling and/or psychotherapeutic approaches can enhance the quality of life for both people with dementia and their care-givers (Olazaran et al., Reference Olazaran, Reisberg, Clare, Cruz, Pena-Casanova, Del Ser, Woods, Beck, Auer, Lai, Spector, Fazio, Bond, Kivipelto, Brodaty, Rojo, Collins, Teri, Mittelman, Orrell, Feldman and Muniz2010). Counselling interventions can support sense of ‘self’ and increase self-acceptance for people with dementia (Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall, Reference Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall2018), reduce depression and/or anxiety in dementia, and have the potential to improve wellbeing (Orgeta et al., Reference Orgeta, Qazi, Spector and Orrell2014; Cheston and Ivanecka, Reference Cheston and Ivanecka2017). Likewise, such interventions have demonstrated positive effects on physical health and depression for care-givers of people with dementia (Mittelman et al., Reference Mittelman, Roth, Clay and Haley2007; Mittelman and Bartels, Reference Mittelman and Bartels2014). However, to date, there has not been a broad review considering the effectiveness of counselling for people with dementia and/or their care-givers. Existing reviews have focused exclusively on family care-givers (e.g. Gallagher-Thompson and Coon, Reference Gallagher-Thompson and Coon2007) or people with dementia (Cheston and Ivanecka, Reference Cheston and Ivanecka2017). The present review updates, integrates and adds to the knowledge base by applying a specific focus on interventions that deliver counselling interventions to people with dementia and/or their care-givers (excluding group settings).

For the purpose of this review, counselling and psychotherapy refer to generally the same activity, defined as a ‘therapeutic encounter’ between two persons, adopting a person-centred approach (Rogers, Reference Rogers and Koch1959; Lago and Charura, Reference Lago and Charura2016). However, we do acknowledge that these two terms in the wider field of therapeutic practice are sometimes also used to mean different activities, as recognised by professional bodies. Considering the range of counselling and/or psychotherapeutic interventions, we have reported interventions in three categories: those delivered to people with dementia, to care-givers and to both. These are further separated by the type of counselling approach, as a number of systematic reviews have analysed the effects of counselling as a generic form of treatment and do not differentiate between psychological approach (Hill and Brettle, Reference Hill and Brettle2005).

Therefore, the present review examined the following research questions:

(1) Are counselling/psychotherapeutic interventions effective for people with dementia?

(2) Are counselling/psychotherapeutic interventions effective for care-givers of people with dementia?

(3) Which modes of delivery are most effective for people with dementia and care-givers of people with dementia?

Methods

The systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The protocol is registered with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42019126977).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that described or evaluated a therapeutic counselling intervention for people with dementia and/or their family care-givers were included. Studies were excluded if they: (a) were not primary research; (b) described a group-based counselling intervention only; (c) did not report participant outcomes; (d) did not provide sufficient description of the intervention; (e) described an intervention for formal care-givers only (i.e. health-care staff); or (f) were multicomponent interventions, including components other than counselling.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed), PsycINFO and CINAHL in March 2019. Keyword searches were employed with terms related to dementia, counselling and intervention outcomes (with terms relevant to family carers added in a secondary search) combined with Boolean operators to join related terms together (e.g. dementia OR Alzheimer's OR … AND counsel* OR psychotherapy OR … AND wellbeing OR …). The full search strategy is presented in Table 1. Search parameters were applied to limit papers from 2000 to 2019. Reference lists of included papers were manually searched to identify further studies.

Table 1. Search strategy used for databases

Note: BPSD: behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

Study selection

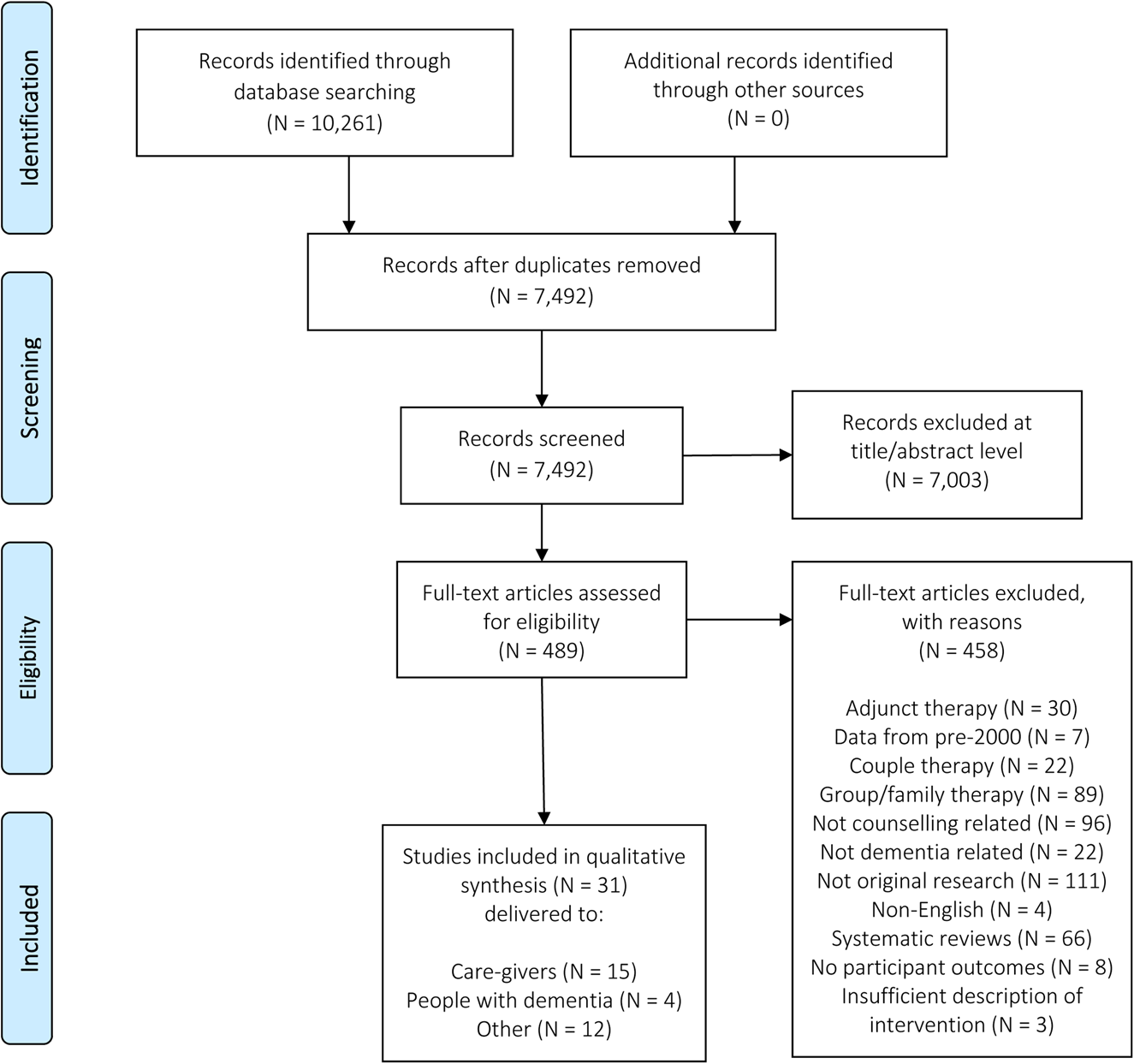

All database hits (N = 10,261) were downloaded into reference management software EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters), and duplicate entries were removed (for the PRISMA flow diagram, see Figure 1). Titles and abstracts of all articles were reviewed by two authors to identify potentially eligible articles for inclusion. Papers excluded at this stage were independently reviewed by a third author to ensure consensus. Two authors then completed a full-text review of all remaining articles, and those failing to meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Included papers were then reviewed by all authors to ensure consensus was reached. Included studies are summarised in Tables 2–4, grouped by those delivered to people with dementia, care-givers and both.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of paper selection process.

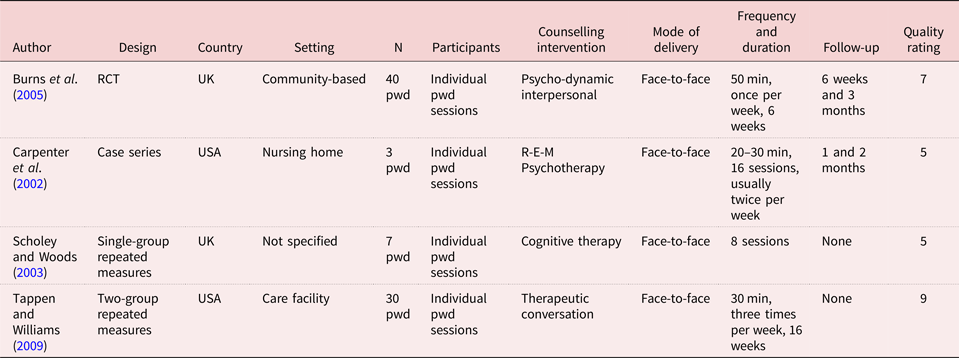

Table 2. Individual study characteristics for interventions delivered to people with dementia

Notes: RCT: randomised controlled trial. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America. pwd: people with dementia. R-E-M Psychotherapy: Restore–Empower–Mobilise Psychotherapy. min: minutes.

Table 3. Individual study characteristics for interventions delivered to care-givers of people with dementia

Notes: RCT: randomised controlled trial. UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America. pwd: people with dementia. min: minutes.

Table 4. Individual study characteristics for interventions delivered to both people with dementia and care-givers of people with dementia

Notes: RCT: randomised controlled trial. USA: United States of America. cg: care-givers. pwd: people with dementia. min: minutes.

Quality assessment

All included papers were subject to a quality review using criteria developed by Caldwell et al. (Reference Caldwell, Henshaw and Taylor2005) and the Critical Skills Appraisal Programme (2014), adapted by Surr et al. (Reference Surr, Gates, Irving, Oyebode, Smith, Parveen, Drury and Dennison2017). This quality review considers whether: (a) the research aims are clearly stated; (b) ethical issues are addressed (i.e. informed consent, confidentiality, withdrawal); (c) the methodology/study design is appropriate and justified; (d) the sample size, selection and description are appropriate; (e) the methods of data collection are appropriate, reliable and valid; (f) the methods of data analysis are reliable and valid, and (g) the findings and discussions are clearly stated and appropriate. This provided a description of the quality of the available evidence base, as part of the analytic process. Each individual paper was assessed, with a maximum possible quality score of 14. Papers with an overall rating of ‘high’ scored 11–14 and met all/majority of the criteria to an adequate level. Papers with a rating of ‘low’ scored ⩽ 5, suggesting the authors met few of the research quality criteria. [ES and CS] independently assessed and rated the included studies and compared scores to ensure agreement. Itemised quality scores for each paper are presented in Tables 2–4.

Analysis

The heterogeneity of intervention strategies and treatment outcomes prohibited use of meta-analysis. Data were extracted from the papers using an extraction table. Comparable information included research methodology, counselling approach/philosophy, mode of delivery, frequency and duration, and outcomes of the intervention. A narrative synthesis was used to categorise studies by recipient, and further by intervention type. Consistent with Gallagher-Thompson and Coon (Reference Gallagher-Thompson and Coon2007), studies were identified that fell within one of two categories: psycho-educational skill-building or psychotherapy/counselling. To be included in the psycho-educational skill-building category, the intervention was required to increase knowledge of dementia and explore coping skills. To be included in the psychotherapy/counselling category, the intervention was required to have an emphasis on the therapeutic alliance rather than psycho-educational skill-building. Within this category, we distinguish between psychological approaches. Inductive analysis was conducted, with [ES] reflecting on the key findings and their implications for practice and research, which was then drawn together to develop a narrative around the effectiveness of counselling interventions, considering both the process and the outcomes.

Results

Study characteristics

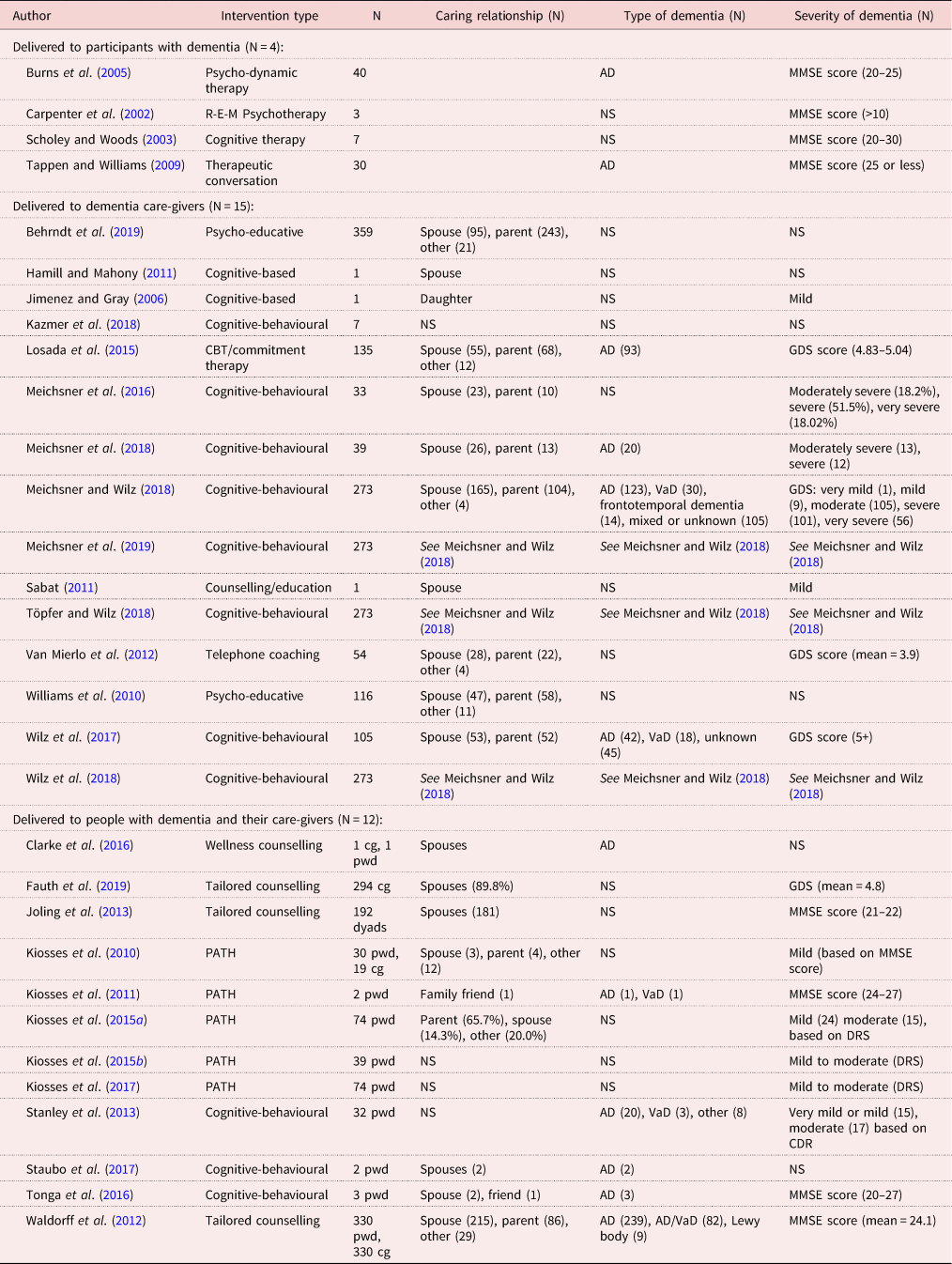

Thirty-one papers were included in the review (for study characteristics, see Tables 2–4). Table 5 reports the demographics of participants, grouped by delivery to people with dementia, to care-givers of people with dementia or to both.

Table 5. Demographics of participants, grouped by delivery to people with dementia, to dementia care-givers or to both

Notes: R-E-M Psychotherapy: Restore–Empower–Mobilise Psychotherapy. CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy. PATH: problem adaptation therapy. pwd: people with dementia. cg: care-givers. NS: not stated. AD: Alzheimer's disease. VaD: vascular dementia. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination. GDS: Global Deterioration Scale. DRS: Dementia Rating Scale. CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating.

Counselling interventions for people with dementia

All of the interventions delivered to people with dementia were included in the psychotherapy/counselling category. Those undertaking the interventions utilised a variety of psychological approaches, including cognitive (Scholey and Woods, Reference Scholey and Woods2003); psycho-dynamic (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Guthrie, Marino-Francis, Busby, Morris, Russell, Margison, Lennon and Byrne2005) and person-centred (Tappen and Williams, Reference Tappen and Williams2009). Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Ruckdeschel, Ruckdeschel and Van Haitsma2002) delivered R-E-M (Restore–Empower–Mobilise) Psychotherapy, which combines psychological approaches, including cognitive-behavioural, humanistic, psycho-dynamic and interpersonal perspectives.

Scholey and Woods (Reference Scholey and Woods2003) delivered cognitive therapy interventions for seven individuals with dementia (diagnosis not specified) and depression. Therapy sessions were structured based upon the model by Beck (Reference Beck1979), with some modifications for adults with cognitive impairment (e.g. the therapist regularly summarised materials). Statistically significant changes in depression were found post-intervention. Although these changes were modest, and the quality of this study is low, these findings provide an indication that cognitive therapy may be beneficial for people with dementia.

Burns et al. (Reference Burns, Guthrie, Marino-Francis, Busby, Morris, Russell, Margison, Lennon and Byrne2005) assessed whether psycho-dynamic interpersonal therapy could benefit cognitive function, mood and global wellbeing compared to usual care for 40 individuals with mild Alzheimer's disease. No improvements on outcome measures were reported, which may be attributable to the ‘low dose’ of treatment, offering only six sessions to the participants (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Guthrie, Marino-Francis, Busby, Morris, Russell, Margison, Lennon and Byrne2005). However, other studies identified in this review offered an alternative approach to counselling for six sessions and indicated positive results (e.g. Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Jackson, Walberg, Lee, Easom, Alston, Ramos, Felten, LaRue and Mittelman2019), suggesting the findings may be attributable to the approach adopted.

Tappen and Williams (Reference Tappen and Williams2009: 270) described their intervention as Therapeutic Conversation, which ‘provides the opportunity to share feelings and concerns with a skilled listener who can understand their attempts to communicate’. While the authors found improvements in affect and depression when compared to the control group, the study had a series of methodological limitations, including a small sample size and relatively poor standard of reporting. However, the levels of cognitive impairment ranged from mild to severe, suggesting the approach is appropriate across various severities of dementia. Despite this, data were not stratified by severity of dementia, therefore it is not possible to know whether this was comparably effective regardless of severity.

Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Ruckdeschel, Ruckdeschel and Van Haitsma2002) delivered R-E-M Psychotherapy to three individuals with mild to moderate dementia (diagnoses not specified). The scores in depression decreased for participants and were at their lowest point at therapy termination. However, this study was rated as low quality, and included a small sample size which cannot be generalised. The intervention remains untested with those with severe dementia and, therefore, it is unclear whether the approach would be successful for those individuals.

Overall, four studies offered counselling interventions exclusively to people with dementia. All four interventions were delivered face-to-face, but the intervention content varied between studies. However, all of the interventions had a primary focus on the ‘present’ for the participant, helping individuals to cope with negative life circumstances and related emotions. Despite the benefits reported, these studies were rated as low to moderate quality. They consistently had small sample sizes (ranging from three to 40 people with dementia), and the lack of participant demographics presented reduced our ability to generalise these findings or understand whether these findings are likely to be replicated on a larger scale. The majority of interventions remain untested for those with severe dementia, with current evidence relying heavily on those with mild dementia. The lack of research into these counselling approaches which are frequently used in practice indicates the need for further investigation of these interventions.

Counselling interventions for care-givers of people with dementia

Psychotherapy/counselling interventions delivered to care-givers of people with dementia all adopted a cognitive-behavioural/cognitive-analytic approach (N = 11). Four studies delivered interventions that were included in the psycho-educational skill-building category.

Psychotherapy/counselling studies

Within the 11 studies that adopted a cognitive-behavioural/cognitive-analytic approach, only three studies delivered the intervention face-to-face (Jimenez and Gray, Reference Jimenez and Gray2006; Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015; Kazmer et al., Reference Kazmer, Glueckauf, Schettini, Ma and Silva2018), to a range of sample sizes (N = 1, 7 and 135 respectively).

Six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) compared a telephone-based, cognitive-behavioural intervention for care-givers compared to a control group. Two of these delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to support grieving care-givers (Meichsner and Wilz, Reference Meichsner and Wilz2018; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016) and the remaining four delivered an intervention called Tele.TAnDem, CBT sessions specifically adapted for family care-givers (Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Meichsner and Soellner2017, Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018; Töpfer and Wilz, Reference Töpfer and Wilz2018; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Töpfer, Reder, Soellner and Wilz2019). One RCT adapted this cognitive-behavioural intervention for delivery via an internet platform (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Theurer and Wilz2018). The majority of these remote-based cognitive-behavioural interventions (N = 6) all reported positive outcomes, including higher quality of life (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Töpfer, Reder, Soellner and Wilz2019) and increased ability to cope (Meichsner and Wilz, Reference Meichsner and Wilz2018; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016, Reference Meichsner, Theurer and Wilz2018; Töpfer and Wilz, Reference Töpfer and Wilz2018; Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018). However, five of the six studies did not report information on whether the study was blinded, and one stated the study was non-blinded for both participants and researchers (Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018), thus increasing the likelihood of biased self-reporting and interviewer-induced bias. Conversely, Wilz et al. (Reference Wilz, Meichsner and Soellner2017) did report blinded assessment and reported long-term intervention effects were found for a higher quality of life, but not for depressive symptoms.

Although the rigorous methodology and high-quality scores suggest that telephone or internet-based cognitive-behavioural interventions are beneficial for care-givers on outcomes such as quality of life and coping, it is possible that a face-to-face approach is advantageous for decreasing depressive scores. This may be attributable to the absence of significant results reported by Wilz et al. (Reference Wilz, Meichsner and Soellner2017). For example, one high-quality study (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015) indicated that both face-to-face counselling interventions (CBT and commitment therapy) were superior in reducing depressive symptoms compared to the control group (a two-hour dementia psycho-educational workshop and booklet termed ‘minimal support’) post-intervention. Similarly, a high-quality study (Kazmer et al., Reference Kazmer, Glueckauf, Schettini, Ma and Silva2018) indicated cognitive-behavioural counselling can improve care-giver depression. Furthermore, two case studies delivered cognitive-based counselling interventions face-to-face to care-givers (Jimenez and Gray, Reference Jimenez and Gray2006; Hamill and Mahony, Reference Hamill and Mahony2011), and reported that depression and anxiety scores were reduced.

Although the quality of these studies are low, these findings may suggest that a face-to-face approach is important for identifying indirect or masked depression that may not be identifiable over telephone- or internet-based communication. This is plausible as Meichsner et al. (Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016) acknowledged that certain nuances pointing to indirect grief may not be noticeable during telephone-based communications. Only verbal aspects of the communication between care-giver and therapist are available, while non-verbal aspects that can provide valuable insight into emotional reactions are not conveyed.

Cognitive-behavioural/cognitive-analytical was the only reported approach in the psychotherapy/counselling studies for care-givers of people with dementia, and thus is supported by the greatest weight of evidence compared to the other therapeutic approaches. Overall, the findings suggest that this approach is effective for depression in care-givers of people with dementia, and there is also evidence of the effectiveness of this approach in enhancing coping abilities within the caring role. However, it is important for future research to evaluate the perceived participant satisfaction of various modes of delivery to ensure varying strategies can be successfully integrated into counselling/psychotherapeutic interventions.

Psycho-educational skill-building studies

Van Mierlo et al. (Reference Van Mierlo, Meiland and Dröes2012) conducted a pre/post-test design with three groups of informal care-givers. Two intervention groups received telephone coaching alone or in combination with respite care, compared to usual care. Care-givers who received telephone coaching in combination with respite care reported significantly less burden compared to those who received telecoaching only, and experienced significantly fewer mental health problems than those who received day care only. Another high-quality study (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Bishop-Fitzpatrick, Lane, Gwyther, Ballard, Vendittelli, Hutchins and Williams2010) compared video-based coping skills training with telephone coaching to a wait-list control condition and investigated the effect of psycho-social and biological markers of care-giver distress. Compared to the control group, intervention participants showed significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety and perceived stress, and average blood pressure was maintained over the six-month follow-up period. Moreover, the high quality of these studies provide confidence for the validity of their results, suggesting telephone- and internet-based interventions for care-givers may be beneficial for care-giver burden and coping mechanisms, as suggested in the above category (Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016, Reference Meichsner, Theurer and Wilz2018; Töpfer and Wilz, Reference Töpfer and Wilz2018; Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018).

Likewise, Sabat (Reference Sabat2011) offered frequent email communication to one care-giver, providing education, counselling and psycho-social support. The care-giver initially experienced feelings of helplessness, low self-esteem and stress. During the intervention, Sabat (Reference Sabat2011) reported that the participant experienced a ‘flourishing of the self’ and developed effective communication strategies and understanding of the care recipient. However, the methodological approach to collecting and reporting data was unspecified, with low-quality evidence, so it is unclear how reliable these findings are, and whether this approach would be beneficial for others.

Conversely, Behrndt et al. (Reference Behrndt, Straubmeier, Seidl, Vetter, Luttenberger and Graessel2019) compared a psycho-educative telephone intervention to control within a large sample of care-givers (N = 359). The intervention focused on stress reduction, development of self-management strategies and coping with challenging behaviours. The telephone-based intervention did not significantly reduce care-givers’ subjective burden. Although care-givers frequently agreed that the intervention had helped them to cope better, this intervention was specifically aimed at those caring for people with mild dementia, although no information was provided about the individuals for whom the participants cared. Furthermore, the lack of significant findings may be attributable to the primarily educative approach. This differs from the flexible coaching (e.g. Williams et al., Reference Williams, Bishop-Fitzpatrick, Lane, Gwyther, Ballard, Vendittelli, Hutchins and Williams2010; Van Mierlo et al., Reference Van Mierlo, Meiland and Dröes2012) that may have been more responsive to the participant's individual needs.

In summary, there is substantially more evidence for the benefits of counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions for care-givers of people with dementia than for people with dementia themselves. However, the findings suggest that counselling interventions have an important role to play for care-givers, particularly for enhancing coping ability within the caring role. More generally, the potential value of all of the identified interventions for care-givers is underlined by the fact that when the different categories are evaluated against each other within this population, the outcomes are not vastly different. Whilst this indicates an absence of superiority of a particular intervention, it does appear important that the content is tailored to individual need. Future research should incorporate longer follow-up periods to determine whether these benefits are maintained in the longer term.

Counselling interventions for people with dementia and care-givers

When interventions were offered to both people with dementia and their care-givers, there was large variation regarding who attended the sessions and the availability of individual, dyadic or family sessions (see Table 4). All of the interventions delivered to people with dementia were included in the psychotherapy/counselling category. Those undertaking the interventions utilised cognitive-behavioural approaches (N = 3), problem adaptation therapy (PATH; N = 5), person-centred approaches (N = 3) or wellness-based counselling (N = 1).

Three high-quality studies delivered person-centred, tailored counselling interventions, where participant needs determined the content (Waldorff et al., Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding, Rishøj, Siersma, Sorensen, Sorensen, Vogel and Waldemar2012; Joling et al., Reference Joling, Bosmans, van Marwijk, van der Horst, Scheltens, MacNeil Vroomen and van Hout2013; Fauth et al., Reference Fauth, Jackson, Walberg, Lee, Easom, Alston, Ramos, Felten, LaRue and Mittelman2019). Fauth et al. (Reference Fauth, Jackson, Walberg, Lee, Easom, Alston, Ramos, Felten, LaRue and Mittelman2019) reported that quality of life scores and social support satisfaction increased while family conflict decreased between baseline and follow-up. Due to the lack of control group, it is difficult to ascertain whether the positive impacts were detected as a result of the intervention. There was also a high attrition rate (49%). Conversely, the remaining studies (Waldorff et al., Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding, Rishøj, Siersma, Sorensen, Sorensen, Vogel and Waldemar2012; Joling et al., Reference Joling, Bosmans, van Marwijk, van der Horst, Scheltens, MacNeil Vroomen and van Hout2013) compared a tailored counselling intervention to usual care, and reported no significant differences in quality of life or depression for either the person with dementia, the care-givers or the dyads collectively. These findings conflict those outlined above that support the benefit of tailoring content to individual need. It is plausible to suggest that tailored content requires an element of problem-solving or enhancement of coping skills in order to lead to positive outcomes, which were not incorporated into the current interventions. Rather, the overarching goals were to improve care-giving ability and delay institutionalisation for individuals with dementia. Moreover, Waldorff et al. (Reference Waldorff, Buss, Eckermann, Rasmussen, Keiding, Rishøj, Siersma, Sorensen, Sorensen, Vogel and Waldemar2012) delivered up to seven sessions across 8–12 months. This frequency should consider ongoing changes in participants’ cognitive abilities, and the changing nature of dyadic relationships, two factors that were not accounted for within this study.

Five studies from the same research group compared face-to-face PATH to face-to-face Supportive Therapy (ST) (Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Areán, Teri and Alexopoulous2010, Reference Kiosses, Teri, Velligan and Alexopoulos2011, Reference Kiosses, Ravdin, Gross, Raue, Kotbi and Alexopoulous2015a, Reference Kiosses, Rosenberg, McGovern, Fonzetti, Zaydens and Alexopoulous2015b, Reference Kiosses, Alexopoulous, Gross, Banerjee, Duberstein and Putrino2017). PATH aims to reduce depression and disability by facilitating problem solving and adaptive functioning, utilising tools to circumvent the behavioural and functional limitations exacerbated by cognitive impairment (e.g. calendars, checklists and notebooks). ST was used as an attention control condition, and focused on non-specific therapeutic factors, such as facilitating expression of affect and conveying empathy. PATH was frequently reported to be more efficacious than ST in reducing depression and disability at 12 weeks (Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Areán, Teri and Alexopoulous2010, Reference Kiosses, Teri, Velligan and Alexopoulos2011, Reference Kiosses, Ravdin, Gross, Raue, Kotbi and Alexopoulous2015a, Reference Kiosses, Rosenberg, McGovern, Fonzetti, Zaydens and Alexopoulous2015b, Reference Kiosses, Alexopoulous, Gross, Banerjee, Duberstein and Putrino2017), and was suggested to be suitable for depressed participants with varying degrees of disability and cognitive impairment. These studies were subjected to well-controlled trials, compared well-validated, manualised and distinct psychotherapies with monitoring of fidelity to intervention, and utilised standardised measures. The rigorous designs and high-quality scores provide confidence for the validity of results, suggesting PATH is beneficial for people with dementia. This aligns with the findings reported by Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Ruckdeschel, Ruckdeschel and Van Haitsma2002), who also utilised a problem-solving approach which led to a reduction in depression scores for participants with dementia.

Two high-quality studies and one medium-quality utilised a cognitive-behavioural approach (CBT) for both people with dementia and their care-givers (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Calleo, Bush, Wilson, Snow, Kraus-Schuman, Paukert, Petersen, Brenes, Schulz, Williams and Kunik2013; Tonga et al., Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016; Staubo et al., Reference Staubo, Misvær, Tonga J, Kvigne and Ulstein2017). Stanley et al. (Reference Stanley, Calleo, Bush, Wilson, Snow, Kraus-Schuman, Paukert, Petersen, Brenes, Schulz, Williams and Kunik2013) compared a face-to-face, CBT-based intervention to usual care. At three months, participants with dementia rated themselves as having higher quality of life, and care-givers reported less distress. However, from baseline to six months, there were no group differences on any self-report outcomes. Staubo et al. (Reference Staubo, Misvær, Tonga J, Kvigne and Ulstein2017) reported that a cognitive-behavioural-based intervention improved depression and quality of life slightly for one care-giver, but no changes were found for the second care-giver post-intervention. Tonga et al. (Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016) delivered cognitive-rehabilitation and cognitive-behavioural treatment for early dementia. Utilising both qualitative and quantitative data, depression and anxiety scores decreased post-intervention for both people with dementia and their care-givers. However, no statistical analysis was provided. Qualitative data suggested two of three participants with dementia reported satisfaction with the intervention (Tonga et al., Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016). All three interventions delivered 11 (Tonga et al., Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016; Staubo et al., Reference Staubo, Misvær, Tonga J, Kvigne and Ulstein2017) or 12 (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Calleo, Bush, Wilson, Snow, Kraus-Schuman, Paukert, Petersen, Brenes, Schulz, Williams and Kunik2013) weekly sessions. A cognitive-behavioural approach may require a longer interval of time to facilitate increased learning and practice, to result in sustainable post-intervention changes. Additionally, Tonga et al. (Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016) emphasised the need to adjust the intervention to people with dementia, tailoring the manual to each individual's background, functioning and previous experience.

Lastly, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Adams, Wilkerson and Shaw2016) delivered wellness-based counselling, based on intentional choices to maximise one's health across multiple domains. Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Adams, Wilkerson and Shaw2016) presented a case study of wellness-based counselling delivered to a participant with Alzheimer's disease and their spouse. Increases were reported in the care-giver's overall wellness, reductions in their stress levels from social support. However, the breadth of the model and its abstract nature may have confused participants.

In summary, mixed evidence has been found for interventions delivered to people with dementia and their care-givers with varying levels of flexibility. Tailored counselling, where the participants set the content, was anticipated to improve outcomes, however only one study demonstrated any outcome change. Problem Adaptation Therapy has shown consistent improvements for depression, although all these studies are from a single research group. Weaker evidence has been demonstrated for other CBT interventions and wellness-based counselling, with reliance on case studies in this area. Several modalities of counselling have been delivered and evaluated for people living with dementia and their care-givers, and rather than techniques of the modality itself, the therapeutic relationship between a professional and the client(s) is thought to be the most important component (Lambert, Reference Lambert and Lambert2013; Paul and Charura, Reference Paul and Charura2014). This is in line with the evidence reviewed here, where limited studies have been conducted across various modalities, with inconsistent results in relation to benefits for clients by modality.

Mode of delivery

Face-to-face approaches reported significant changes in outcomes for people with dementia, across modalities including cognitive-behavioural (Scholey and Woods, Reference Scholey and Woods2003), therapeutic conversation (Tappen and Williams, Reference Tappen and Williams2009) and problem-solving (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Ruckdeschel, Ruckdeschel and Van Haitsma2002). For people with dementia and their care-givers, benefits from face-to-face approaches were found (e.g. Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Areán, Teri and Alexopoulous2010); whilst both face-to-face (e.g. Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015) and telephone and internet-based interventions also led to positive outcomes for care-givers (e.g. Meichsner and Wilz, Reference Meichsner and Wilz2018; Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016, Reference Meichsner, Töpfer, Reder, Soellner and Wilz2019). Despite this, there was a lack of detailed information regarding the mode of delivery. Thus, it was challenging to separate the nature and extent of the impact of mode of delivery within interventions for both participant groups. Research exploring and evaluating the impact that the mode of delivery has on process and outcome is required. Future research could be strengthened by comparing groups that implement interventions using face-to-face delivery or remote alternatives, in order to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding how the intervention is best received.

Discussion

There was large variation in the counselling/psychotherapeutic approaches and modes of delivery identified within this review. Most of the interventions adopted either a problem-solving or CBT approach, which was effective in reducing depressive symptoms among people with dementia (e.g. Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Areán, Teri and Alexopoulous2010, Reference Kiosses, Ravdin, Gross, Raue, Kotbi and Alexopoulous2015a). The results also suggested that these approaches are effective for care-givers (e.g. Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015; Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018), with effects that are maintained over time (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015). However, some important considerations emerged. Studies explicitly discussed the need to use modifications, such as simplifying the materials and shifting focus to behavioural components, to accommodate the cognitive needs of a person with dementia (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Calleo, Bush, Wilson, Snow, Kraus-Schuman, Paukert, Petersen, Brenes, Schulz, Williams and Kunik2013; Tonga et al., Reference Tonga, Karlsoeen, Arenvik, Werheid, Korsnes and Ulstein2016). Each person with dementia may need customised modifications based on their cognitive abilities and needs (Tay et al., Reference Tay, Subramaniam and Oei2019), and increased care-giver participation depending on the level of impairment (Spector et al., Reference Spector, Charlesworth, King, Lattimer, Sadek, Marston, Rehill, Hoe, Qazi, Knapp and Orrell2015). Future research should consider these modifications to develop a standardised form of CBT for people with dementia, specifically considering issues around an individual's ability to apply and generalise the strategies learned to their daily life (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015).

Few studies identified a tailored approach, despite person-centredness being endorsed as good practice, encompassing a holistic and personalised ethos (Johnston and Narayanasamy, Reference Johnston and Narayanasamy2016; Oyebode and Parveen, Reference Oyebode and Parveen2019). Those that did identify a tailored approach operated through identifying situations that led to negative emotions, such as memory problems and social isolation, and targeting these (e.g. PATH; Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Rosenberg, McGovern, Fonzetti, Zaydens and Alexopoulous2015). However, several high-quality studies that delivered a tailored intervention were excluded due to analysing data collected from pre-2000 (e.g. Mittelman et al., Reference Mittelman, Roth, Coon and Haley2004a, Reference Mittelman, Roth, Haley and Zarit2004b, Reference Mittelman, Roth, Clay and Haley2007). These studies reported significant improvements in self-rated physical health, depression and care-givers’ reaction to the care recipient compared to those in the control group (Mittelman et al., Reference Mittelman, Roth, Coon and Haley2004a, Reference Mittelman, Roth, Haley and Zarit2004b, Reference Mittelman, Roth, Clay and Haley2007). This may be attributable to the tailored, personalised nature of the intervention and the opportunity to learn skills or develop psycho-social coping resources for use within the care-giving role.

Psycho-dynamic interventions with individuals with dementia remain virtually untested through controlled clinical trials. Support for the utility of this approach tends to be drawn from anecdotal evidence and authors acknowledge that the approach has not been validated with this population (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Guthrie, Marino-Francis, Busby, Morris, Russell, Margison, Lennon and Byrne2005). Future research is required to establish attitudes towards and address the efficacy of psycho-dynamic interventions for people with dementia and/or their care-givers, and additional clinical evidence should be presented before this approach is adopted more widely.

Face-to-face approaches appeared to have a bigger impact on outcomes such as depression and anxiety for both the person with dementia and their care-givers, across modalities. When delivering an intervention face-to-face, certain nuances indicating masked or indirect depression/anxiety may be more identifiable. Additionally, to date, telephone and internet-based interventions remain untested with people with dementia and it remains unclear whether this mode of delivery would be beneficial for those with dementia, who are likely to have communication difficulties (Burgio et al., Reference Burgio, Allen-Burge, Stevens, Davis, Marson, Clair and Allman2000). Moreover, novel technology-driven interventions did not appear to adopt a holistic view of the health of family care-givers and their care recipient, but rather focused on psycho-education and developing or improving care-giver coping strategies (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Roberts, Wu, Ford and Doyle2016). While there is evidence that telephone- or internet-based counselling can reduce depressive symptoms for care-givers of people with dementia (Lins et al., Reference Lins, Hayder-Beichel, Rucker, Motschall, Antes, Meyer and Langer2014), this needs to be further validated by evaluating efficacy through robust RCTs. However, it is currently difficult to ascertain the nature and extent of the impact of mode of delivery and future research should compare these different modes of delivery (Elvish et al., Reference Elvish, Keady, Lever, Johnstone and Cawley2013).

In addition to providing support, care-givers were often present to gain psycho-education about dementia and to assist the participant to practise the skills learned in the session (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Calleo, Bush, Wilson, Snow, Kraus-Schuman, Paukert, Petersen, Brenes, Schulz, Williams and Kunik2013; Spector et al., Reference Spector, Charlesworth, King, Lattimer, Sadek, Marston, Rehill, Hoe, Qazi, Knapp and Orrell2015). Offering increased quality and quantity of homework for people with dementia and their care-givers may increase the likelihood of treatment-related benefits (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Marquez-Gonzalez, Romero-Moreno, Mausbach, Lopez, Fernandez-Fernandez and Nogales-Gonzalez2015), particularly for those struggling with short-term memory problems associated with dementia. Understanding these dyadic relationships, in order to provide support for both partners, is essential to offering effective interventions, and guidance for practitioners is needed.

People with dementia have highlighted three specific target areas that should be focused on within psychotherapeutic interventions (Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall, Reference Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall2018). Loss of both abilities and a sense of identity are common amongst people with dementia. Previous evidence has demonstrated that identity is able to be reclaimed for people with dementia (Gillies and Johnston, Reference Gillies and Johnston2004). Although, a focus on incorporating a new identity as a person with dementia, restructuring cognitions to normalise the condition, may help individuals to adjust (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). Individuals who are unable to accommodate this are more likely to experience distress (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). The second target area, coping mechanisms, is known to be crucial when adjusting to living with dementia (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). Psychotherapeutic interventions can improve everyday functioning by targeting unhelpful and maladaptive thinking patterns and helping individuals to develop coping behaviours (Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Oude Voshaar, Keijsers, Hoogduin and van Balkom2008). Strategies such as behavioural activation could be used, which encourages clients to engage in situations and activities with specific goals that lead to positive reinforcement (Cully and Teten, Reference Cully and Teten2008). This would help individuals to break a cycle of maladaptive coping strategies and develop individualised coping mechanisms (Cully and Teten, Reference Cully and Teten2008), which may need to be practical as well as emotional (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). Within dementia, this is particularly prominent, as both people living with the condition and their family members tend to compare and ruminate on life pre-diagnosis and may need support to accept the diagnosis (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). The third target area, support, incorporated the need for inclusion, reduction of perceptions of loneliness and developing cognitions of hope (Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall, Reference Birtwell and Dubrow-Marshall2018). Counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions offer the opportunity to explore these areas, helping individuals to understand their condition and address any support-related fears (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Roen and Thornton2014). However, within the current research, there is limited consistency in the outcomes targeted by interventions and detail provided to establish whether these areas highlighted by people with dementia are consistently being considered or included within therapeutic interventions. For the research area to develop, an understanding of the feasibility of such interventions, appropriate outcomes and expected levels of change needs to be developed.

However, despite these promising findings for the benefits of counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions for people with dementia, the majority remain untested for those with more severe dementia. Interventions for those with severe dementia were consistently delivered exclusively to care-givers rather than the individual themselves (i.e. Meichsner et al., Reference Meichsner, Schinköthe and Wilz2016). We recommend a person-centred approach is taken, when designing future research studies, which does not exclude those with more severe dementia based on diagnosis, but instead seeks to understand whether psychological interventions are appropriate for this population. This may include exploring attitudes towards such interventions, the ability of individuals to develop and maintain a therapeutic relationship, and identifying appropriate outcomes for managing change.

Inconsistencies were also demonstrated in whether follow-up data were collected and, if so, the frequency and length of follow-up. Of the 31 studies included in this review, 15 did not report any follow-up period. The remaining studies reported follow-up periods ranging from six weeks to two years. Inconsistences were also found for whether any changes reported at the end of the intervention were maintained by follow-up, particularly if data were collected at more than one follow-up period. Further work should be conducted to develop an in-depth understanding of how outcomes changed for individuals over time within the existing literature, to identify the most appropriate follow-up period for establishing meaningful change.

This review builds on a small number of existing reviews that have considered psychotherapeutic interventions for people with dementia and/or care-givers. In line with these reviews, reductions in outcomes associated with negative mood, such as depression, were found for people living with dementia (Orgeta et al., Reference Orgeta, Qazi, Spector and Orrell2014; Cheston and Ivanecka, Reference Cheston and Ivanecka2017). Whilst some existing reviews have examined psycho-social interventions more broadly, where counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions may form a number of these (e.g. Gallagher-Thompson and Coon, Reference Gallagher-Thompson and Coon2007), our review has greater specificity, particularly when considering modality, which arguably offers more utility for practice.

Limitations

For many studies identified in this review, there was an inadequate clarification of study design and intervention description, indicating that future research is warranted to improve the evidence base, ensuring high-quality research is conducted. The lack of quality in many of the studies identified in this review indicated the absence of essential information for replicability, and very few reported robust findings for people living with dementia. This limited the depth of the research questions we could have asked, e.g. the appropriateness and effectiveness of interventions for those affected by increasing severity of cognitive impairment. Due to the large variation in intervention approach, outcome measures and sample sizes, it was challenging to draw comparisons between studies and did not permit meta-analysis to be conducted, which would have helped guide both research and practice. Furthermore, there was a lack of clarity around the type and severity of dementia in each study. For some studies, participant diagnoses were also not reported, resulting in difficulties describing the samples and drawing comparisons between them. Specifically, to establish the effectiveness of counselling across the lifespan of dementia, greater understanding of the cognitive impairment that participants experience, and how this affected delivery of the intervention, is required, which was not considered in any study within the present review. Aspects of difference should be considered in every therapeutic relationship, and we identified limitations in the studies presented in this review as they did not address the potential impact of client differences (such as culture, gender, ethnicity, comorbidities and class). This is particularly important as the maintenance of a therapeutic relationship is key to effective counselling (Paul and Haugh, Reference Paul and Haugh2008), and how dementia affects this is currently unknown. To date, this information has not been regularly provided, meaning that replication is not possible.

Recommendations for research and practice

Working with professional bodies to fund and disseminate research findings for both practice-based and evidence-based practice will enhance awareness of this important yet underacknowledged and underresearched area. Additionally, generic, core and specialist competencies should be developed to ensure that therapists are appropriately qualified to deliver interventions to people living with dementia (see Roth et al., Reference Roth, Hill and Pilling2009). These should be developed with people with dementia and their families, to ensure that the voice of those with lived experience is reflected. For example, working with those who may have cognitive difficulties, as well as fluctuation in cognitive abilities and capacity, can provide challenges to therapists. These challenges are not addressed even in the generic or core competencies for therapeutic work. For example, one of the interventions reported in the present review required only attendance at an eight-hour training session before qualified cognitive-behavioural therapists could deliver this (Wilz et al., Reference Wilz, Reder, Meichsner and Soellner2018).

When evaluating psychotherapeutic interventions for with people with dementia, authors should report as a minimum their specific diagnosis and severity of dementia and, where possible, provide evidence of performance on cognitive assessments. This is particularly important as some evidence has demonstrated that therapy is not without contraindications, e.g. individuals may deteriorate as a result of therapy (Cooper, Reference Cooper2008). Additionally, for care-givers, their relationship with the individual should be specified in order to understand how this may vary based on proximity to the person with dementia.

Currently, the evidence base includes studies with small sample sizes, including N = 1. Whilst limited robust conclusions about effectiveness can be drawn from these studies, they are able to offer a unique and in-depth insight into the lived experience of people with dementia. Thus, they contribute towards the development of knowledge, providing a foundation for larger and more robust studies to be conducted. Future research should now test the effectiveness of counselling and psychotherapeutic interventions on a larger scale, using robust methods, such as RCTs, to provide more definitive evidence for the effects of these interventions for people with dementia. Specifically, RCTs should be conducted that compare modalities and modes of delivery, to establish the most effective and cost-effective mode and modality, for people with dementia and their care-givers. It is important to acknowledge that this may not be consistent across these groups, and even within sub-groups, e.g. differential diagnoses of dementia or those living alone, or in rural compared to urban areas. These studies should incorporate a process evaluation to consider intervention context, implementation, mechanisms of impact and outcomes for participants (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey, Barker, Bond, Bonell, Hardeman, Moore, O'Cathain, Tinati, Wight and Baird2015). In the more immediate timeframe, qualitative work should be conducted to establish attitudes towards these interventions amongst people with dementia and their families, to understand how acceptable these interventions and their expected outcomes are.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review has identified a range of therapeutic modalities that have been delivered to people with dementia and their care-givers. Although grouped under ‘counselling and psychotherapy’ in this paper, these are varied and include generic counselling, specific models (i.e. CBT) as well as more tailored approaches. We found that this range of psychotherapeutic interventions can lead to meaningful change for people with dementia and their care-givers on a range of outcomes, including depression, anxiety and quality of life. However, the evidence is inconsistent in terms of outcomes measured and whether change was achieved. Progress in this research area is limited by the lack of information provided in studies to allow replicability and understand how participants are affected by dementia (i.e. their level of cognitive impairment). Furthermore, language use is inconsistent, and clarity of therapeutic modality-specific interventions is needed, e.g. clarifying the similarities and differences between counselling, psychotherapy and tailored approaches. A greater understanding of what meaningful change looks like within this population is needed before the appropriateness and effectiveness of counselling for people with dementia is confirmed. Therapists must ensure that interventions are targeted to the experiences, level of cognitive impairment and background of participants. Whilst there are limited pharmacological interventions for people with dementia, psychotherapeutic interventions can offer ongoing support for those living with the condition.