1. Introduction

An intriguing observation when one looks across developed health systems is that East Asian systems (except for Japan) spend substantially lower gross domestic product (GDP) percentages on health care than do nearly all Western European systems. Equally noticeable is that, despite these lower expenditures, medical outcomes and health status in these developed Asian health systems are broadly equal to or better than those found in their more expensive Western European counterparts.

This counter-intuitive relationship – substantially higher Western European health expenditures yet equivalent East Asian clinical and epidemiological outcomes – can be clearly seen in standardly available international data.

As Table 1 indicates, total expenditure in the four developed Asian health systems (all figures are purchase power parity adjusted) ranged from 4.4% of GDP (2017) in Singapore (5.6 million population) to 6.3% (2016) in Taiwan (23.8 million population) and 8.1% (2018) in South Korea (51 million population) to 10.9% (2018) in Japan (126.8 million population). In comparison, the equivalent 2018 numbers for key western European health systems show consistently higher figures, from 9.8% for the UK and 11.0% for Sweden (for tax-funded health systems) to 9.9% for The Netherlands and 11.2% for Germany (for social-health-insurance funded health systems) (OECD, 2017; Yoong et al., Reference Yoong, Lim, Lin, Legido-Quigley and Asgari-Jirhandeh2018).

Table 1. Percentages of total health expenditure in GDP and epidemiological outcomes in Developed Asian and European health systems

Source: https://stats.oecd.org/, https://data.worldbank.org/, and Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (12).

Yet, Table 1 also shows clinical outcomes and epidemiologic data for developed East Asian health systems that are broadly equivalent to those for Western European countries. Life expectancy figures range from age 80 to 84 in the Asian systems, compared with 81.1 to 83 in the European ones. Five year survival rates for cancer care – a sentinel outcome both clinically and politically – are slightly better in East Asia (except for Taiwan) for colorectal cancer (60.3 to 69.5% as compared with 59.7 to 66.3%) and roughly equal (including Taiwan) for breast cancer (80.3 to 88.9% as compared with 85.6 to 88.8%).

These observed differences in health sector expenditure and performance between East Asian systems such as Singapore, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, in comparison with tax-funded European systems such as Sweden and England, and also social-health-insurance-funded systems such as the Netherlands and Germany, reflect inter-related political, cultural and institutional as well as economic and financial factors (Oliver and Mossialos, Reference Oliver and Mossialos2005; Saltman, Reference Saltman, Jameson, Fauci, Kasper, Hauser, Longo and Loscalzo2018). The impact of these factors was compounded in much of Western Europe by the recessionary post-2008 fiscal crisis environment, placing health systems under heavy financial pressure at the same time that they needed to meet rapidly developing international standards for new technology and effective treatment of major life-threatening conditions such as cancers and heart disease (Donnelly, Reference Donnelly2019; Saltman, Reference Saltman2019).

In this complicated policymaking context, the two above-detailed data-based comparisons between developed Asian and Western European health systems suggest a series of core institutional questions. A central underlying issue is whether developed Asian systems have put in place mechanisms for financing and operating contemporary health care systems that are more clinically efficient and more policy effective than those currently in use particularly in tax-funded Western European countries.

Funding strategies for developed country health systems have received extensive academic attention since the 1990s (Glaser, Reference Glaser1991; Saltman and Figueras, Reference Saltman and Figueras1997; Mossialos et al., Reference Mossialos, Dixon, Figueras and Kutzin2002). Recent years have seen increasing concern about the need for additional funding for Western European health systems, particularly for predominantly tax-funded systems similar to that in Sweden (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Figueras, Evetovits, Jowett, Mladovsky, Maresso and Kluge2015; Saltman, Reference Saltman2015a, Reference Saltman2019). In 2019, the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies in Brussels published two policy analyses on aging societies, calling for more diverse funding sources for European health systems (Cylus et al., Reference Cylus, Figueras and Normand2019a, Reference Cylus, Roubal, Ong and Barber2019b). Direct calls for higher taxes and more public funds have also been made by other prominent European public health figures (Modi et al., Reference Modi, Clarke and McKee2018).

Interest in more efficient management of publicly owned hospitals and of the public hospital sector has been prominent since the early 1990s in both developed country (Culyer et al., Reference Culyer, Maynard and Posnett1990; Hood, Reference Hood1991; Saltman and von Otter, Reference Saltman and von Otter1992) and also developing country (Preker and Harding, Reference Preker and Harding2003) settings. Subsequent research has suggested that semi-autonomous management strategies can improve financial efficiency as well as patient satisfaction in publicly owned hospitals (Saltman et al., Reference Saltman, Duran and Dubois2011). Simultaneously, however, opposition to adopting private sector style management tools for public hospitals has grown in some tax-funded health systems, in particular Sweden (Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2014), which also has seen national government efforts to constrain the role of privately capitalized elderly care facilities (Winblad et al., Reference Winblad, Blomquist and Karlsson2017).

Over the past decade, better clinical coordination between primary and hospital care, on the one hand, and hospital and social/long-term care, on the other, has become a major topic of health sector as well as academic concern (Genet et al., Reference Genet, Boerma, Kroneman, Hutchinson and Saltman2012). Integrated and/or coordinated care is seen as an effective strategy to reduce rapidly growing publicly funded costs for caring for multiple chronically ill elderly (Busse et al., Reference Busse, Blumel, Scheller-Kreinsen and Zentner2010). These financial concerns have intensified as the number of elderly in developed countries has grown.

2. Comparing health systems of Singapore and Sweden

This paper contributes to the long-running health system debate described above about improving health system funding and delivery by providing a detailed case study of two high-income, small-population countries: one Asian – Singapore; and the other Western European – Sweden. It compares the two countries differing mechanisms of health sector funding, the implications for more efficient use and management of health provider resources, and the potential to free up existing health-related funding for use by elderly citizens for both pensions and long-term care. In so doing, the case study also considers the formative role that national culture plays in shaping each citizenry's policy expectations and patient behavior.

The general pattern of lower costs but similar demographic and clinical outcomes in developed East Asia is particularly apparent when one looks at what is the lowest spending developed health system in Asia, which is Singapore. Recent interest in Singapore's health sector arrangements has however been rather sparse: a 2001 article with three short commentaries (Barr, Reference Barr2001; Ham, Reference Ham2001; Hsiao, Reference Hsiao2001; Pauly, Reference Pauly2001), a 2003 chapter in a World Bank volume (Phua, Reference Phua, Preker and Harding2003); more recently a 2013 review of the Singapore health system (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013), followed by a short, dismissive editorial (McKee and Busse, Reference McKee and Busse2013).

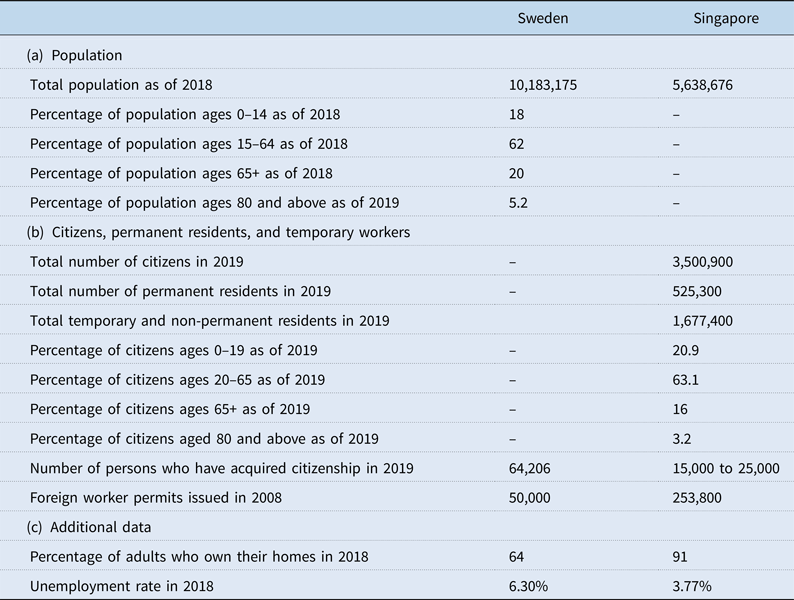

Both Singapore and Sweden have relatively small, homogeneous populations – Singapore has 5.6 million population, of which 74.3% are ethnic Chinese (DOS, 2018), while Sweden has nearly 10.2 million people, of whom 80% are ethnic Swedes. However, Table 2 reveals a complex set of demographic statistics that suggest Sweden's substantially higher health care costs may be only partially related to its number of older inhabitants. Singaporean citizens (e.g. those who fully participate in Singapore's medical savings account system) make up approximately the same percentage of younger age groups (20.9% are under age 20 to Sweden's 18% under age 15, with 63.1% under age 66 compared with Sweden's 62% under age 65). Sweden does have a small but significantly higher number of more elderly inhabitants – 20% over age 65 and 5.2% over age 80 – in comparison with older Singaporean citizens with 16% over age 65 and 3.2% over age 80.

Table 2. Selected statistics for Sweden and Singapore, 2018 and 2019 data

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/country/sweden; https://www.statista.com/statistics/378643/unemployment-rate-in-singapore/; https://www.mom.gov.sg/documents-and-publications#/?page=1&q=&facet=category&category=Statistics; https://www.thelocal.se/20200109/heres-a-look-at-who-got-a-work-permit-in-sweden-last-year; https://www.statista.com/statistics/664518/home-ownership-rate-singapore/; https://tradingeconomics.com/sweden/home-ownership-rate; https://www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/population/population-composition/population-statistics/; https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/files/media-centre/publications/population-in-brief-2019.pdf; https://sweden.se/society/elderly-care-in-sweden/; https://www.statista.com/statistics/624913/singapore-population-by-age-group/.

Regarding numbers of non-citizens (who in Singapore have differing relationships to the health financing system, as detailed in the next section), Singapore issues many more foreign work permits than does Sweden however Sweden's foreign workers (whether manual and professional) often come from elsewhere in the European Union, do not require work permits, and do not show up in permitting statistics. Additionally, a (non-EU) work permit in Sweden continues to be difficult to obtain and difficult to keep (The Local, 2018).

Finally, regarding refugees, Sweden, a geographically expansive – and in its interior, sparsely populated – country, has taken in several hundred thousand refugees coming from Latin America in the 1980s, Bosnia in the 1990s, as well as more recently from various Middle Eastern countries. Quite differently, Singapore – a geographically tiny country located in a politically volatile part of the world – generally does not accept refugees.

Both countries have had periods in which they were seen internationally as role model health systems for other countries' governments to study – Sweden in the 1980s; Singapore more recently. In a symbolic turn of events, in 2018 the Swedish government's Department of Innovation (Vinnova) sent a high-level delegation of Swedes to visit Singapore, with the express purpose of better understanding how technology that has been introduced in the Singaporean health system might be utilized in the Swedish system (Eriksson et al., Reference Eriksson, Isaksson and Jovic2019).

A key observation that underlies this case study is that Singapore has become a source for new health policy ideas adopted by other countries seeking more effective and efficient health care systems. One of the more attractive international concepts for funding health care services in a fiscally constrained financial future is that of medical savings accounts. As discussed below, a rapidly developing Singapore in 1984 was the first country to implement such a system on a nationwide basis (Barr, Reference Barr2001). Subsequently, this Singaporean funding concept has become increasingly central in two of the world's largest health care systems. In 1998, People's Republic of China structured its new health insurance program for urban workers on a variation of the Singaporean medical savings account model (PRC, 2012). In 2003, the United States' federal government introduced an optional variation on Singapore's medical savings account system of paying for health care services in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, replacing a previous medical saving account system with a new tax-free system of Health Savings Accounts (H.R.1).

Thus the core concept of Singapore's health system payment approach has served as a model for two countries that have populations of 320 million (United States) and 1.3 billion (China), that have the world's no. 1 and no. 2 largest economies by GDP, and that had two of the world's fastest growing economies in the decade prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a notable accomplishment for a small island nation of 5.6 million people, suggesting that the core funding concept it developed has broader applicability and can be expected to support strong economic growth.

Equally important – and potentially equally attractive for policymaking purposes in tax-funded Western European countries – the Singapore model of health savings accounts directly links incentives to reduce spending in the health sector to increased savings for retirement pensions. Combined with the ElderShield program that provides individually-paid long-term care insurance (see below), Singapore's health funding model also takes a major step in reducing public sector revenues needed to pay for elderly care services.

Singapore further pioneered two additional provider-side concepts that have become important in other developed country health systems. In 1987, Singapore combined its 15 publicly owned and operated hospitals, which provide 80% of all hospital beds in the country, into a single independent public corporation, the Hospital Corporation of Singapore, which is independently managed – e.g. free of direct political interference – but remains publicly accountable for its results both fiscally and in clinical outcome terms (Ramesh, Reference Ramesh2008). Similar semi-autonomous private-style management strategies for what remained publicly owned hospitals have since been implemented in a number of European health systems, starting with the UK in 1991, and spreading in various forms and degrees through other developed European systems during the 1990s and early 2000s including Italy, Spain, Norway, Estonia and Czech Republic (Saltman et al., Reference Saltman, Duran and Dubois2011).

The second hospital management mechanism pioneered in Singapore that has subsequently been adopted elsewhere was the concept of transparent pricing for hospital services. The Transparency Reform of 2003 required all hospitals (public and private) to update their pricing structure for services online every month, with the expectation that this would enable patients to make better decisions about how to commit funds from their health savings accounts (MOH, 2007). The logic was that of the private market: posted pricing would encourage hospitals to worry about their competitive position vs other institutions, and act as a damper on price increases (Kessler and McClellan, Reference Kessler and McClellan2000; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Craig, Gaynor and Van Reenan2019). Similarly, the holder of a medical savings account could become more of an informed purchaser, and less likely to demand overly expensive or medically unnecessary services (Buntin et al., Reference Buntin, Damburg, Haviland, Kapur, Lurie, McDevitt and Marquis2006; Dody, Reference Dody2014).

This concept of requiring hospitals to post prices for their services has now been adopted in the United States in June 2019, with an executive order requiring a similar set of hospital pricing notifications in all hospitals. This is intended to improve patient choice decisions – primarily for elective and outpatient procedures – especially for individuals with high-deductible health insurance plans under the 2010 Affordable Care Act as well as those privately insured with (what have been renamed in the United States) Health Savings Accounts.

Thus three important characteristics of the Singaporean health system have since been adapted for use in other developed countries: medical savings accounts, semi-autonomous operating structures for public hospitals and mandatory posted pricing for hospital services. Taking advantage of the uniqueness of the Singaporean health system, this paper explores core underlying policy implications that emerge from comparative analysis of Sweden and Singapore, focusing on funding arrangements, the delivery model in hospital governance and the different cultural roots and social expectations in which these two health systems are embedded.

A caveat here is that reflecting space limitations this paper focuses only on financing, access to and delivery of curative clinical services. As such it does not assess the scale, scope or implications of these two countries' preventive policies and measures regarding health or social care services.

3. Comparing the two health systems

3.1 Differing forms of risk-sharing

A central distinction between the Swedish and the Singaporean health systems is their differing notions and applications of the concept of solidarity. Solidarity has traditionally been understood in Western European health systems as an equal sharing of financial risk among all the participant members of the solidarity community (Houtepen and ter Meulen, Reference Houtepen and ter Meulen2000; Saltman and Dubois, Reference Saltman, Dubois, Saltman, Busse and Figueras2004; Yeh, Reference Yeh2019). In practical terms in developed countries, solidarity has multiple sources, and may be strengthened or weakened depending on the economic capacity of its specific guarantors (Saltman, Reference Saltman2015b).

3.2 Institutional solidarity in Swedish health system

In the Swedish case, currently, solidarity in the sharing of risk for funding publicly provided health and social services is predominantly provided through three separate levels of publicly levied taxes (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012):

(a) Regional: A flat-rate tax assessed by each of 20 county or regional councils – typically 14% of all earned income above a small deductible funds approximately 80% of total costs of public hospital and primary care, chronic care and alcohol-related services.

(b) Municipal: A flat-rate tax assessed by each of 295 municipal governments – typically 17% of all earned income above a small deductible, to pay for multiple municipal services including a substantial portion (minus mandatory co-payments) of nursing home and home care services.

(c) National: A scaled income tax of up to 50% on all earned and a sliding portion of investment income. In addition, the Swedish government levies a 25% value-added tax (VAT) on all purchases and services across the entire economy, including food and clothing. Although most health and social care costs are paid for from county and municipal taxes, the national government contributes additional funds for cross-constituency equity balancing and certain prioritized medical programs.

In aggregate, the three levels of Swedish government together provide public tax-based funding – flat-rate (regional and municipal) and size-of-income-scaled as well as value-added and property taxes (national) – of 84% of total Swedish health expenditures (Data, Reference Data2019).

In addition, Sweden has three privately paid sources of what is also risk-sharing for health funding and thus what is also practically speaking a functional form of solidarity among insurance participants:

(d) Occupational: National-government-mandated company provision (including public sector agencies) of specified workplace-related services, including primary care services, for full- and half-time employees, paid for by the business, provided either at the worksite by private providers or at contractually paid county-council-run primary health centers.

(e) Private-company-provided, private health insurance policies: A number of private companies purchase private commercial health insurance for curative primary and elective care for their employees. Although these policies are also purchased by some large well-capitalized businesses, past research starting in the 1980s (Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal1986) demonstrated that often these policies are purchased by smaller companies seeking to insure that senior executives critical to the company's survival would, if they became ill, be able to jump the long queues for elective public hospital procedures and get back to work as soon as possible (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012).

(f) Private individually purchased health insurance policies: These are individual citizens choosing to buying separate (supplemental) private health insurance policies, for example for cancer care which has had long queues for many years in Sweden.

The combined total for private insurance coverage of (e) and (f) is currently estimated at over 600,000 policies in a country of 10 million citizens (Barkman, Reference Barkman2017), up from 382,000 in 2010 (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012). The Swedish government has actively discouraged the purchase of additional private cover since 1988 when it removed the income tax deductibility of privately purchase health insurance policies (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012).

3.3 Institutional solidarity in Singaporean health system

In the Singaporean case, currently, there are two forms of mandatory public solidarity:

(a) MediSave: This is a national system of medical savings accounts, imposed by law, funded by mandatory pre-tax deductions from an employed persons' salary (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013) (additional voluntary contributions are not pre-tax). These accounts are administered by the same national government agency, the Central Provident Fund Board (CPFB) that administers the national pension system (CPFB, 2018). In 2017, each employed individual whose monthly wage was $750 (about $550 in USD) or more was required to automatically contribute, depending on age, 1% (if above age 65) to 23% (if age 35 or below) of earnings (CPFB, 2019). These funds are automatically placed in that individual's personal account, maintained by the national (pension agency), and paid a specified level (by law) of interest for funds that are not withdrawn or otherwise invested in approved assets such as conservative stock funds (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013).

The amount automatically deducted from salary rises as an individual's salary rises. Once the total balance in an individual's medical savings account reaches a specified level for that person's age (currently 57,000 Singapore dollars, about 41,000 USD, for an individual who reaches age 65 in 2019), then all further deposits (which continue as long as the person is employed), or investment earnings, are – again automatically – transferred to that person's (also mandatory) nationally administered individual retirement account (which each individual also owns and can leave to heirs) which can be invested in approved assets once the total reaches an age-specified amount (Singapore CPF website).

Funds can be withdrawn from these accounts to pay for listed medical costs (hospital, primary care and home care), not only for the account holder, but also for any member of the account holder's direct family. Funds beyond an age-tied balance also can be used toward buying a home, which is seen as ‘vital for political and social stability’ (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013, p. 4). Table 2 shows that 91% of Singaporean citizens own their own homes, in contrast to 64% of Swedes.

An essential aspect of the attractiveness to citizens of these mandatory publicly-collected and managed accounts, and of their impact on health care utilization, costs and prices, is that all funds that remain un-used in an individual's medical savings account when that person dies (exactly as in their mandatory individual retirement account) are automatically inherited by that person's heirs, and – crucially – on a tax-free basis (Barr, Reference Barr2001; Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013). Thus there are strong incentives built into the medical savings account system for each working adult to be careful with how he utilizes services provided by the Singapore health care system, and to try to treat minor and less-serious events in the least expensive manner.

(b) MediFund: This is a wholly publicly funded safety net for low-income individuals who do not have sufficient medical savings account balances to pay for necessary services. Individuals must send their applications to an independent MediFund Committee at each provider institution in order to have their care paid by this fund. Clinical services provided by this public fund are of the same standard as for self-paying individuals, however hotel services are provided only on a non-air-conditioned 12-bed ward basis (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013).

The above two public mandatory systems of risk-sharing for health care costs in Singapore are supplemented by one public and two private, voluntary, risk-sharing insurance-based arrangements:

(c) MediShield: This is a publicly offered but optional medical insurance plan to help pay for prolonged illnesses that may require long-term treatment, such as kidney dialysis or some cancer treatments. Individuals are automatically enrolled unless they opt out – less than 10% of the population chose not to be covered – and enrollment must take place before age 75. Annual premiums are relatively low, increasing with age and can be paid from the individual's MediSave account. There is an annual deductible, and outpatient services have a fixed 20% co-payment before benefits apply (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013).

The Singaporean government has proposed to replace the voluntary MediShield framework in 2020 with a comprehensive, mandatory program of long-term care coverage called CareShield Life, which all citizens over age 21 will be required to hold and pay.

(d) ElderShield: This is voluntary private insurance for long-term disability, established by the national government in 2002 to help individuals cover the costs of nursing homes and long-term care. All individuals are enrolled at age 40, paying annual premiums until they reach age 65. Individuals are enrolled in one of the three different private insurance company plans as selected by the Ministry of Health (MOH, 2018b). Although formally voluntary in the sense that individuals can choose to opt out, some 80% of Singaporean citizens aged above 40 choose to pay the premiums to carry this coverage (MOH, 2018d; DOS, 2019). Premiums can be paid with MediSave or with private funds (MOH, 2018a). Individuals can also buy supplements that have higher payouts (MOH, 2018c).

(e) Private commercial insurance: Many Singaporean citizens also choose to purchase individual private health insurance called Integrated Shield Plans, which can be paid by savings in their MediSave account. Although these insurance plans are offered by private companies, the benefits are all identical, regulated by the government. These plans cover costly services that are not payable through MediSave (CPFB). In addition to the Integrated Shield Plans, Singaporean citizens can also purchase other private health insurance policies.

Beyond this framework of individual contribution-based framework, the Singaporean government directly injects substantial public subsidies into essential and/or expensive hospital, medical and pharmaceutical services, with higher subsidies provided to lower income citizens (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013). These public revenues – collected primarily through income and sales taxes – amounted to 48.2% of total health expenditures in 2017 (World Bank, Reference World Bank2020).

Three additional funding points further flesh out Singapore's health sector funding approach. The first two concern the treatment of immigrants. Permanent residents are required to participate in the MediSave system, with the proviso that, if they leave the country permanently, they can take their account balances with them. Thus these immigrants contribute directly to the solvency of the overall MediSave program. The only difference is that permanent residents receive only 50% of the direct public subsidy for essential hospital, medical, and pharmaceutical services (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013).

The second point is that temporary residents with work permits must have private health insurance bought for them by their employers, purchasing strictly regulated policies that must provide Singapore $15,000 of medical coverage (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013). This privately paid insurance providing access to high-quality medical care, coupled with relatively high pay levels and an individual monthly government ‘assistance’ payment of Singapore $750 for living costs (Li, Reference Li2020), makes working in Singapore very attractive compared with most workers' home countries.

A third point concerns foreign patients who travel to Singapore for a specific procedure. Singapore's combination of high quality and relatively low medical costs attracted an estimated 500,000 international patients in 2018, paying full charges, resulting in about 4% of total hospital income (Medical Tourism Singapore, 2020). This ‘medical tourism’ thus provides a small but noticeable degree of external cross-subsidization for infrastructure operating costs in the Singapore hospital system.

In solidarity terms, therefore, the Singaporean model represents a mixed system of individual and collective forms of financial responsibility, in which a bit more than half of all funding is private (although predominantly mandatory) funds, while a little less than half is public tax funding (World Bank, Reference World Bank2020). Within this global framework, a notable second characteristic is that Singapore's funding system applies four different levels of public sector subsidy payments to help defray charges for individual medical services: full subsidy level for citizens; half subsidy level for permanent residents; 0% subsidy level for foreign patients and a separate, substantially higher subsidy level for low-income individuals (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013).

As Table 3 demonstrates, this privately sourced funding figure of 51.8% of total health expenditure in Singapore is nearly triple that of Sweden's privately sourced health funding percentage of 16.3%. Conversely, in 2017, in purchasing power parity adjusted figures, the government of Singapore spent 2058 USD of public tax funding per inhabitant for health services, while the government of Sweden spent more than double that amount of public funds, or 4770 USD, with both countries achieving quite similar clinical and epidemiological outcomes.

Table 3. 2017 health expenditures Sweden and Singapore

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/.

All USD adjusted for PPP.

4. Policy implications

Two main policy-related distinctions can be drawn from the two-country comparison above. Although these observations apply first and foremost to the countries involved, they also serve to raise larger issues for health systems development generally, and potentially for the near and medium-term future across fiscally-straitened tax-funded health systems in Western Europe (Alesina and Giavazzi, Reference Alesina and Giavazzi2008; Saltman and Cahn, Reference Saltman and Cahn2013; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Figueras, Evetovits, Jowett, Mladovsky, Maresso and Kluge2015).

First: Differences in the practical structure of responsibility and solidarity for payment of health care services in these two countries, reflecting differing cultural roots and social expectations.

Singapore: In Singapore, the concept of responsibility begins directly with the individual him- or herself. Beyond that personal level of responsibility lies, as the second layer of protection, the concept of solidarity, but solidarity that begins at the family level, between immediate family members and then also among more extended brothers/sisters/aunts/uncles. In this sense, solidarity merges with the level of individual private and personal responsibility. Although this private family solidarity is supplemented – for varying services and in varying degrees – by a range of government-generated public subsidies, the public sector plays a secondary rather than a primary role in the construction of practical day-to-day social support.

The fundamental focus of health policymaking for financing health care services in Singapore is to generate individual and family-based, private-sector (or civil society) levels of financing and accountability. The core policy expectation here is that, by placing first and foremost emphasis on each individual's personal and family responsibility, it will be easier and more efficient for society and/or the government to meet the necessary core requirements (e.g. public funding for certain hospital services) as well as additional needs of lower income citizens. Equally important, the large role for publically mandated but privately controlled funding creates incentives to not spend money unnecessarily, whether that might mean more expensive and/or unnecessarily long hospital stays, duplicative medical services and procedures, brand-name rather than generic pharmaceuticals (both inpatient and outpatient) and numerous other examples of discretionary medical decision-making that are unlikely to affect clinical outcomes but which can have substantial effects on the total cost of care.

Lee Kuan Yew, the former long-serving Prime Minister of Singapore, explained this approach to health policymaking by suggesting it is consistent with two fundamental characteristics of moral culture in Far East Asian societies generally: Confucian ethics and family responsibility (Zakaria and Lee, Reference Zakaria and Lee1994). Lee repeated the traditional Confucian political thought that later became a folk-wisdom phrase and which lies behind Singapore's approach to structuring social programs (originated from the Confucian classic Great Learning or Daxue, 大學) (Zakaria and Lee, Reference Zakaria and Lee1994: 113–114):

Xiushen – First, look after yourself, make yourself useful

Qijia – Second, look after the family

Zhiguo – Third, look after your country

Pingtianxia – Fourth, all is peaceful under heaven

Thus in Singapore's system of health care financing, the individual and then the family take pre-eminence – indeed are required to take pre-eminence under the State-enforced structure of medical savings accounts (McKee and Busse, Reference McKee and Busse2013). Subsequently, there are further ‘fall-back’ lines of, first, volitional self-selected private insurance risk pools (e.g. MediShield), followed by additional private commercial insurance policies, and, as a last resort, if needed, public tax-funded welfare state funds (MediFund). Focusing on the family as the building block for social programs also is consistent with the deep-seated traditional economic framework in much of Asia, where family-based farm operations were at the heart of the economy. Overall, most decisions about paying for health care services, up to the level of catastrophic hospital care, are made for most Singaporeans by themselves and/or a member of their immediate family, rather than by a level or agency of government. Looking at risk-based pooling (as against individual out-of-pocket expenses), then, one can conclude that in Singapore there are four different levels of practical financial solidarity, in which only the fourth, last form – MediFund – is fully public sector tax-payer funded.

Sweden: The conceptual approach to solidarity in Sweden has been quite different, following along on traditional lines of social democratic welfare-state principles (Korpi, Reference Korpi1983). In Sweden, these principles were consolidated under the general principles of ‘Folkhemmet’, introduced after the Social Democrats were first elected to national power in 1932. In this view, solidarity is a strictly public sector concept, uniting each separate individual with the agencies and instruments of government (municipal, regional and national), by assuring all individuals that the public sector will provide the necessary funding and, in the case of the tax-funded health systems of Northern Europe such as Sweden, the required publicly operated health services, to meet all legitimate medical needs of every Swede. In this view, solidarity in health care is the same – indeed an integral part of – solidarity in social and home services, disability coverage, occupational services, housing allowances, child care services, monthly cash child stipends, university tuition, university living costs and a wide range of additional State-mandated and State or local-government funded services (Korpi, Reference Korpi1983; Saltman and von Otter, Reference Saltman and von Otter1992).

This concept of ‘folkhem’ was conceived as a ‘halfway’ measure between socialism and capitalism, encompassing not just health care but all welfare state services as well as education, arts and culture, reflecting standard Socialist rhetoric about the political importance of controlling the content of education and culture (Lindbom, Reference Lindbom2001). In this traditional Socialist view of the world, there was little perceived role for family responsibility (Landsorganization, 1990). Indeed, the Swedish Social Democratic Party saw itself as providing at least some of the personal development that traditionally had been the responsibility of the nuclear family, a perspective that continues to be carried out both in party organizations and youth groups as well as in core public sector institutions and services such as Dagis (day care centers for all infants and pre-elementary age children) and the programs and centers of Fritidsgard (secondary student free-time centers).

Thus, in Sweden's system of health care financing, there is little role for individual responsibility, beyond small annual co-payments for primary care and outpatient prescriptions, both of which are limited by Parliamentary decision to a total of 3350 SEK or about 335 USD per 12 month period (Sweden.se, 2018).

Instead, preponderant financial responsibility is lodged with public sector tax funds, with decision-making about the expenditure of those funds being made by a mix of politically elected and administratively appointed public sector officials.

The concept of equality that undergirds this public role has both strengths and weaknesses. The strengths revolve around the sense of security – trygghet, in Swedish – that lies at the core of the Folkhem concept. No Swede worries that they will not be able to afford to pay for the medical services they need.

Conversely, however, this public guarantee comes with reservations and conditions. Sweden has had, since the late 1980s, growing funding problems for publicly provided health care at the county council level (which provides all hospital and – until 2007 all, now still 50% – of primary care services). Sufficient cancer care services have been a particular problem. Although additional national funds have recently been committed to expanding cancer care services, there remain difficulties in access to timely care, as well as to new cancer-fighting biologic pharmaceuticals. More broadly, in the post-2008-fiscal-crisis, information-revolution-driven world, Swedish county councils have had increasing difficulty keeping up with the rapidly changing international standard of medical treatment (Saltman, Reference Saltman2019).

Second: Considerable difference in the relative balance of public as against private sector responsibilities for owning, operating and managing these two countries' respective hospitals.

A key observation is that in Singapore, the substantial majority of hospital operating and capital decisions, exactly like overall health care payment decisions, are not made by politically elected officials and/or permanently employed, politically hired, public sector bureaucrats. Instead, these provider operating decisions are made either by private sector individuals or by employees of a public sector corporation working under quasi-independent private sector accountability, in both cases in accordance with private sector decision-making criteria (albeit in both cases under state regulatory supervision).

Importantly, given the post-1987 Health Corporation of Singapore structure for all public hospitals, this absence of direct political decision-making in day-to-day operations takes place in public as well as private provider institutions (Phua, Reference Phua, Preker and Harding2003).

Singapore: A central characteristic of the hospital system in Singapore is the major role of private ownership and management. To be sure, political authorities are responsible for steering a range of public financing subsidies [amounting as noted earlier to 53% of total operating revenues in 2016 (WHO, 2019)] to both public and private hospitals, as well as funding any operating shortfalls – after Singaporean citizens pay their share of hospitalization costs in these public hospitals with their medical savings accounts – in the overall income of the 15 public hospitals that make up the Hospital Corporation of Singapore. The government also sets care guidelines as well as strict policies on the use of budget surpluses (Haseltine, Reference Haseltine2013). There is a clear distribution of differing clinical responsibilities among Singapore hospitals, with public institutions making up the major tertiary care and university teaching institutions, providing 80% of total hospital beds (Data.gov.sg, 2017).

Since both public and private sector hospitals operate under private-law-based, non-political management, they are able to develop their own business plans and to raise their own investment capital (from internal or external, e.g. investment sources), allowing them to make managerially and market-motivated decisions on investments in new capital equipment, new services and new employees (Phua, Reference Phua, Preker and Harding2003). This gives both public and private hospitals considerable flexibility to innovate to meet the rapidly changing clinical standards of care and outcomes that accompany the current period of technological development.

Thus, although struggles over institutional decision-making between medical professionals and hospital administrators have a long history in all health systems, making them appear almost as inevitable (Young and Saltman, Reference Young and Saltman1985), the added difficulty of negotiating directly with elected politicians over each budget item is not part of the annual funding or delivery process in either public or private hospitals in Singapore.

Sweden: The structure of hospital ownership, operation and management in Sweden is nearly entirely public sector in structure. There are only two small 40-bed private hospitals, and even these institutions sometimes rely on off-hours public sector specialists for their medical capacities (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012). Recently, faced with high capital costs for new hospital construction, there have been several public–private partnerships (PPPs) developed around either expansions or new builds, which has included setting up a new private company (with partial public sector ownership) to operate and manage these new institutions. Although the New Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm is the largest of these PPP models, there also has been a new Children's Hospital in Goteborg (Queen Silvia's Hospital for Children, opening in stages 2018–2020), and an expansion of the central hospital in Angelholm in Skane County which opened in 2018. Beyond these examples, however, with the exception of one privately contracted public hospital in Stockholm County (Sct. Gorans), and despite an initial, now rescinded (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012), increase in institutional self-management in some hospitals in some counties such as Stockholm (e.g. Danderyd and Huddinge hospitals), secondary and tertiary hospital capacity in Sweden continues to be owned and directly operated by elected county level politicians and their managerial appointees (Anell et al., Reference Anell, Glenngard and Merkur2012).

This mostly public structure of hospital ownership, management and operation carries several implications for the efficiency and effectiveness of hospital services in Sweden. Proponents of the public sector view it being less expensive and more efficient than the private market (Dahlgren, Reference Dahlgren2014) contending that public ownership is more financially efficient [see also the planned market/public competition argument in Saltman and von Otter (Reference Saltman and von Otter1992)]. These proponents further contend that public sector operation creates a transparent structure for policy decisions about health care services, with public budgeting debates and a direct link between service delivery decisions in county council providers and the income-tied tax rate that citizens have deducted from their paychecks. Indeed, Swedish commentators and outside observers alike regularly note the advantages of the direct democracy aspects of how the Swedish health system is configured (Saltman, Reference Saltman2015a).

Conversely, others (and sometimes the same commentators following the fiscal austerity after the 2008 financial crisis) point out dilemmas at the operational and decision-making levels in politically run health systems. These critics point toward the inherent sluggishness and rigidity in service decision-making, especially regarding new procedures, technology and equipment, that appear to also be characteristics of wholly publicly administered health systems (Busse et al., Reference Busse, van der Grinten, Svensson, Saltman, Busse and Mossialos2002; Stubbs, Reference Stubbs2016; Edwards and Saltman, Reference Edwards and Saltman2017; Tjerbo and Hagen, Reference Tjerbo and Hagen2018; Saltman, Reference Saltman2019). They worry about the high fixed costs of bureaucratically administered institutions and the sluggish time-consuming process of getting political decisions at either the institutional managerial or capital investment level (Kittelsen et al., Reference Kittelsen, Magnussen, Anthun, Häkkinen, Linna, Medin, Olsen and Rehnberg2008; Eijkenaar, Reference Eijkenaar2012; Rehnberg, Reference Rehnberg2019). In a time of rapidly changing international standards for care provision, driven by the information revolution which impacts all organizational and clinical dimensions of health care provision, cumbersome political processes raise questions about the timeliness and quality of provider services in a politically operated health system similar to that of Sweden.

5. Further observations

As the above discussion highlights, the structural differences between a tax-funded European system similar to Sweden and the Medical Savings Account (MSA)-based Singapore model are substantial. Beyond financing differences of MSA-based frameworks noted, traditional tax-funded systems also have fundamentally different cultural and political as well as health sector organizational arrangements. To draw on the case study above, Sweden's ‘folkhem’ model, with its broad emphasis on governmental responsibility and a wide-ranging equality (jamlikhet) of position, situation and outcome of all individuals in society, is structurally quite different from the individual-tied, family-based framework of responsibility embodied in Confucian ethics.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Swedish experiments with semi-autonomous public hospitals [similar to those put in place in Singapore in the mid-1980s (Ramesh, Reference Ramesh2008), which were introduced in several hospitals in Stockholm County in the early 1990s (Bruce and Jonsson, Reference Bruce and Jonsson1996)], were relatively quickly eroded by the lack of fit between semi-autonomous hospital decision-making and powerful county-politician-based policy and budgetary controls (Saltman, Reference Saltman2015a). Furthermore, politically, despite substantial health sector financial pressures, in 2014 the two key national political parties involved in setting up the then-incoming minority Social-Democratic-led national government agreed a four-page memo of understanding that called for the flat prohibition of any health sector actor earning surplus revenue – e.g. ‘profit’ – or introducing any system of New Public Management in publicly operated hospitals. The national government's Reepalu Report in 2016 codified this anti-profit perspective (SOU, 2016: 78).

This clear contrast between the institutional and operational health sector realities in Singapore as against those in contemporary Sweden suggests that efforts to transcend the structural and cultural boundaries that separate two such dissimilar countries would be difficult at best. Traditional path dependency theory as applied to health systems further reinforces this concern (Oliver and Mossialos, Reference Oliver and Mossialos2005). However health sector history also suggests that similarly major leaps in health system structure can in fact occur. Denmark shifted its health sector funding in 1970 from social health insurance to a tax-funded model, as did Portugal in 1979, Italy in 1978 and Spain in 1986, as well as UK in 1948. Conversely, many Central European countries moved from state-funded to a hybrid state-run form of social insurance, or in the case of Czech Republic, to regulated private insurance, in the early 1990s. As the recent, unsuccessful effort of Ireland in 2011 to shift from tax-funded to social health insurance – following on the similarly short-lived policy discussion in the UK in the late 1980s – suggests, this type of fundamental structural transition is difficult to engineer and implement.

One frequently noted caution in comparing Sweden's health care costs with those of other countries is that Sweden has proportionately both more elderly and more immigrants. Both groups are considered to be more resource-intensive than younger and/or domestic populations. As Table 3 indicates, Singapore does have a somewhat more favorable demographic profile for elderly, however immigration statistics – as noted earlier – are more difficult to compare. Moreover multiple factors go into elderly care expenses, making cost implications harder to determine. In Sweden, for example, (free) informal caregivers (typically family members) were estimated in 1997 to care for 70% of all home care patients (although carers did receive some indirect government benefits such as pension points) (Johansson, Reference Johansson1997).

A second comparative point is the contention that, although Sweden's health system is operated by elected local-based democratic councils, Singapore, whereas formally democratic with a representative parliament, is virtually a one-party state and thus ‘not a democracy’. A discussion of the range of institutional options in structuring a democratic national government is more of a political science than a health policy topic. In this case, however, it is Singapore that makes available to its citizens more control and authority over how their health care money is spent, that allows them the freedom to retain those funds for present and future use, and whose health system structure enables patients increased choice over where and from whom they receive their medical services. Thus if a key measure of democratic government is the freedom of individuals to make decisions about important dimensions of their own life, in the health sector Singapore would seem to qualify.

6. Conclusions and limitations

By comparing two small-population national health systems – those of Singapore and Sweden – this paper highlights several key elements of health system structure in developed countries of East Asia as against those found in tax-funded health systems in western Europe. Notable in this Asian–European comparison are substantial differences between Singapore and Sweden in (a) the percentage of health system funding that is privately as against publicly raised, and (b) the amount of public tax money per inhabitant spent in each health system. This second tax-funded figure – 2058 USD for Singapore as compared with 4770 USD for Sweden – represents a striking difference, and reflects a fundamentally different policy and cultural balance between collective public as against individual private responsibility for funding health care services.

Overall, the paper examines four linked policymaking dimensions of Singapore's health sector structure, each of which take on increased importance in the current period of persistent public sector funding shortages in Western Europe's tax-funded health systems, particularly in coping with these countries' increasing numbers of chronically ill elderly and elderly retirees:

(1) Singapore's predominantly individual-based funding framework costs half as much public money as does Sweden's approach for largely similar clinical services and outcomes (2058 USD as against 4770 USD)

(2) Singapore's health funding strategy deals affordably with the costs of long-term care services for the elderly, a major concern going forward for every Western European health system: 80% of Singaporeans carry their own privately paid (but government regulated and priced) long-term care insurance, and many purchase additional long-term care supplements; typically with these insurance premiums paid from the individual's mandatory health and retirement savings accounts.

(3) Surplus health care funds that accumulate in individual medical savings accounts in Singapore automatically roll over to those individuals' personal pension accounts (also publicly mandated and maintained), where the funds help pay for those individuals' retirement living expenses thus reducing public sector pension and elderly housing costs.

(4) Amounts remaining at death in both an individual's medical savings and personal pension accounts in Singapore are inherited tax-free by a member of the individual's family, and can be invested in the Singapore economy – what welfare state theorists have termed the ‘productivist’ model which has been a central element in East Asian economic development (Peng and Wong, Reference Peng, Wong, Castles, Liebfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010).

Given the weak economic prognosis for European economies in the post-COVID-19 period, the attraction of a potential Singapore-style re-allocation of funding between public and private sectors, and between health and long-term care and pensions, as well as potential efficiency gains in hospital management, suggest that Singapore's health sector policies could become increasingly interesting in the Swedish as well as in other Western European tax-funded health systems.

Longer term, European economic projections forecast continued economic weakness for several years beyond 2020 – reflecting the cumulative damage of COVID-19 coming in addition to economic weakness remaining from the financial crisis of 2008 (Giles, Reference Giles2020). Since lower economic activity reduces public sector VAT and income tax totals, health sector funding implications for tax-funded systems will likely be considerable. Indeed, figures from quarter 2 for 2020 show the Swedish economy contracting by 8.6% (Rees, Reference Rees2020), and the quarter 2 drop in overall Eurozone GDP of 12.1% makes this same point for other tax-funded countries in Western and Central Europe (Strauss et al., Reference Strauss, Cocco and Bruce-Lockhart2020). With a number of European governments facing pressure to assess their COVID-19-related performance, the hard reality of reduced public revenues will likely make more mixed health financing and service delivery solutions look increasingly attractive.

To be sure, the extent to which Singapore or other developed East Asian health systems might serve as potential models for Sweden or other Western European tax-funded health systems is a politically, economically, as well as culturally fraught question. Path dependency in health care systems – maintaining existing institutions and allocations has been shown to be particularly difficult to alter (Oliver and Mossialos, Reference Oliver and Mossialos2005; Saltman, Reference Saltman2015a).

Further research may help explicate complicated calculations for government policymakers regarding a range of issues including overall approaches to achieving demographic, geographic and socio-economic equity; the potential impact of private sector management tools inside publicly operated provider institutions; the potential links between private payment and demand suppression; as well as the precise impact of differing population distributions (old and young; also immigrant) on overall health sector costs and efficiency. Additional analysis may help develop differing governance models that can serve to support existing health sector provider configurations (Duran et al., Reference Duran, DuBois, Saltman, Saltman, Duran and DuBois2011).

These and similar questions will involve complex data compilation and assessment which go beyond the capabilities of one article. As an example, analyzing the potential implications of elderly differences in immigration and population mix on overall health and social care costs in Singapore compared with Sweden will require additional economic and financial data about the current mix of collectively and/or medical savings account funded (formal) as against unfunded, informal caregiver provided long-term care provision in each country, particularly since informal caregiver provided home care is partly publicly subsidized in Sweden through several different municipal and national tax-generated accounts.

As this case comparison of Singapore and Sweden has demonstrated, the structural, political, economic and cultural dimensions of other East Asian and European countries would need to be unwound to effectively consider advantages and disadvantages of different structural alternatives to what continue to be common health sector dilemmas. Each tax-funded European country's situation will be unique, and the potential usefulness of an East Asian counterpoint will differ considerably.

Despite these and other comparative concerns, the confluence of lower total health system and much lower public sector health care costs combined with broadly equivalent clinical and health status outcomes in Singapore as compared with Sweden would appear to raise important questions that deserve careful further policy consideration in tax-funded European health systems generally.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the journal's reviewers for their helpful comments.