Humans need myths, not only to identify themselves with their local group, but also with humanity at large (Campbell and Moyers, Reference Campbell and Moyers2001). Jung formulated the idea of the phylogenetic layer in the psyche of a man, which consists of archetypes whose contents, mainly images, fill this ‘collective a priori beneath the personal psyche’ (Paraschivescu, Reference Paraschivescu2011). It is known that the origin of a myth can be only explained by understanding them as collections of constant experiences of humanity (Jung, Reference Jung1966). Therefore, as humans, individuals with autism could relate to similar myths, or create their own, to share their inner world, allowing them to relate with each other's individual experiences (Sharmacharja, Reference Sharmacharja2016). Is it possible that there is a collective unconscious among people with intellectual disability, in this case, autism?

The collective unconscious may consist of mythological motifs or primordial images, thus the myths of all nations are their real exponents (Jung, Reference Jung, Harris and Woolfson2015). The primordial image presents an archaic character that strikes concerning mythological motifs, also known as an archetype (Jung, Reference Jung, Harris and Woolfson2015). Every artistic representation has its part of the essence and ideology of an artist by itself, and a certain type of archetypal representations (Sharmacharja, Reference Sharmacharja2016). Similar concepts, such as perennial philosophy, also suggest the existence of a universal set of truths and values common to all peoples and cultures (Almendro, Reference Almendro2007), including those with difficulties or disabilities. This paper looks over the work of four artists with autism to understand their inner worlds and mythologies.

The artists considered in this paper are individuals who tend to represent existent myths, thematics and characters as well as artists that are inclined to create their mythologies. The selected artwork varies from groups or individual activities provided by an artist, art activities, non-artist led and self-initiated art activities.

The Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale (FEATS) was used to analyse drawing elements, as it is considered reliable in the field (Gantt and Tabone, Reference Gantt and Tabone1998). Some other aesthetic elements were observed in the artwork made by individuals with autism, from researchers such as Colin Rhodes, Graciela García and Roger Cardinal. Drawings from George Weidener, Gregory Blackstock, Sinichi Sawada and Fatima Calderon were analysed. The drawings were obtained from the public collection ABCD Art Brut and from the data collection realised at the Day Center of La Puebla de Cazalla, Spain. Ethical approval has been obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee before this analysis.

Artwork made by people with autism is constantly fascinating because of their particular intimate content and the devotion to their work. One can identify a psychic confinement characteristic of the autistic condition (Cardinal, Reference Cardinal2009). Back in the days, ‘autism’ was a symptom of schizophrenia, it was an inclination to divorce oneself from reality (Bleuler, Reference Bleuler1950). Nowadays, the autism condition is still considered a disadvantage, although it is no longer a psychotic condition. However, this rich neurodiversity could be the origin of the production of these inner worlds and mythologies.

The productions made by people with autism have been ignored and marginalised, similarly to the art by other neurodiverse populations. Most of the time, when they are recognised, their condition tends to be eclipsed or simply analysed from the diagnosis perspective. The perception of their art has constantly included assumptions about autism, which generates a limitation to its analysis, and misleads the spectators about the experiences of individuals with autism (Barber-Stetson, Reference Barber-Stetson2017). A better approach to this would be to celebrate their art, appreciating neurodiversity.

The mental path of individuals with autism can be interpreted using a scale. According to the DSM-5, the autistic spectrum disorder can be defined as restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This characteristic can be observed in different parts of the life of people with autism, including the art they produce.

Individuals under autistic spectrum disorder tend to have an excessive adherence to their routines and may also have a restricted pattern of behaviour that manifests a resistance to change (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Their artwork reflects this by sticking to the same topics and techniques. Moreover, these repetitive routines and behaviours may represent a way of making a ritual, as they tend to ritualise patterns of verbal and nonverbal behaviour (García, Reference García2012).

This impression of a never-ending ritual relates to a process that always needs to be completed, it reminds of what Carl Jung described as the creative impulse (Domenici, Reference Domenici2019). The artist feels the impulse to complete the world, which he perceives as incomplete; and the spectator perceives this world as full (Valdivia, Reference Valdivia2016). This characteristic could be linked to archetypal behaviours in the art-making process, which could be more constant in individuals presenting autism, as it is already a characteristic of this mental condition.

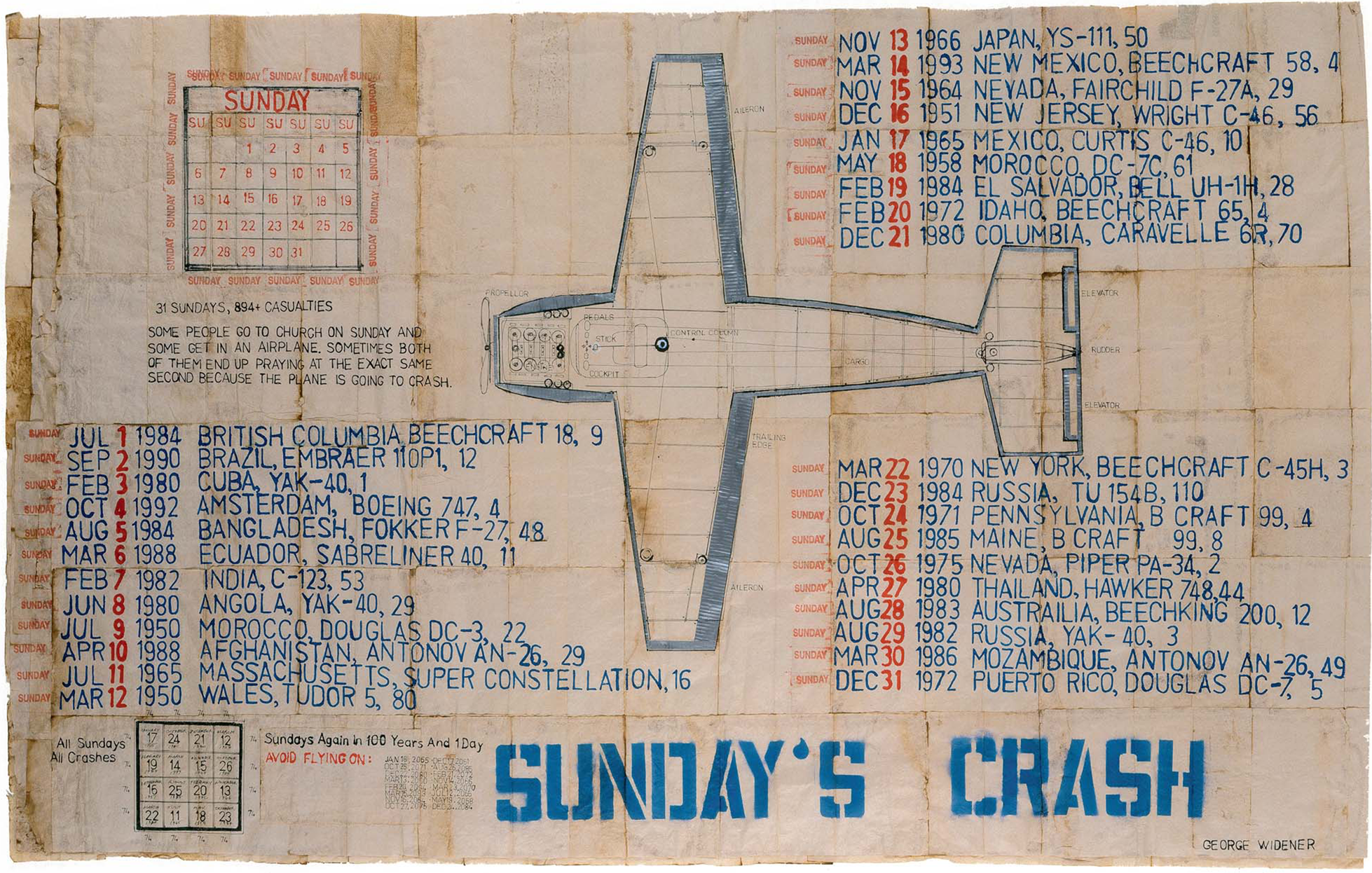

The artwork of George Weidener (1962) is an example of the repetition of recurrent thematics related to his inner world. He was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, which was described in 1943 by Hans Asperger as a mild typology of autism that is usually accompanied by an exceptional development of the memory. In 2013, the DSM-5 replaced autistic and Asperger's disorder with the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

People presenting autism, unlike schizophrenics who cannot stop interpreting their environment, live in a highly visual world but don't assign symbolism to it (Sacks, Reference Sacks1990). Their work tends to be produced with a certain type of automatism, and it can show skills related to determination, memory and calculation (Barber-Stetson, Reference Barber-Stetson2017). Among other topics, he has a particular fascination with the ship ‘Titanic’, and he can retain all kinds of data related to it. He became more fascinated with the story of Titanic when he discovered that one of the passengers had the same name as himself (García, Reference García2012).

He combines his drawings with handwritten typography, where the content is as important as the aesthetics. He likes the way letters and numbers are mixed in his work because they seem to him to behave as cities, buildings and ships. In his work, writing is a distinguished element that complements certain types of lists. The topics on these lists have different thematics, especially the concept of the calendar where days, months and special dates regarding the topic are represented, as well as explanatory paragraphs. Figure below depicts a list of airplanes that have crashed on a Sunday:

‘Some people go to church on Sunday and some get in an airplane. Sometimes both of them end up praying at the exact same second because the plane is going to crash’.

Art has a connection with the outside world, and it sometimes is the only connection with reality that people with autism conserve (Sacks, Reference Sacks1990). Weidener has different themes and interests in his artwork that can lead to these connections. He has a system of Magic Squares that allows him to establish links between events in the past and predict the future (García, Reference García2012).

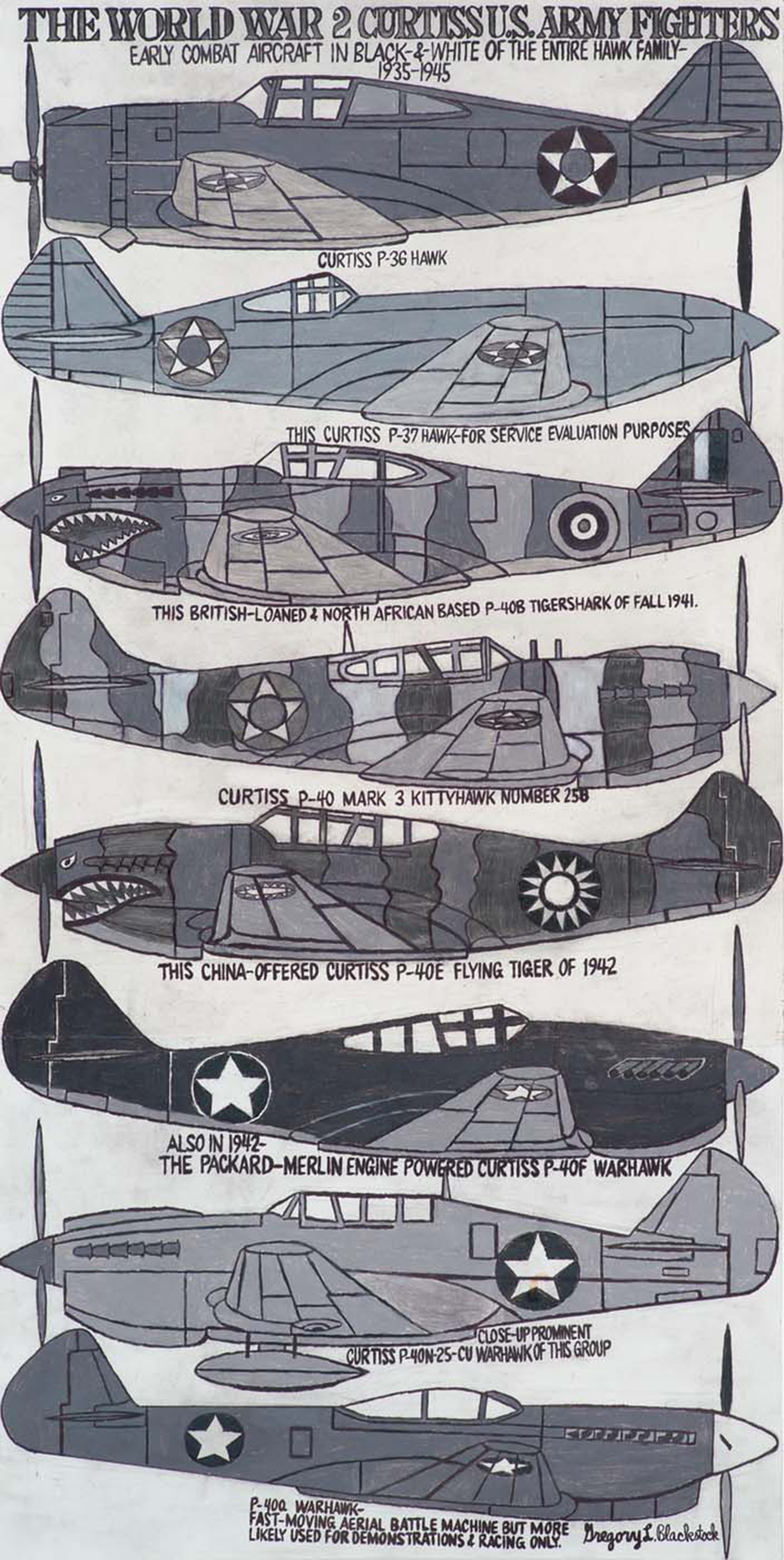

Another prominent artist diagnosed with autism is Gregory Blackstock. He was born in 1946 in Seattle, Washington (USA). He was initially diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia; when it was later determined that he had autism, he started being perceived as a more functional individual, and considered an autistic savant. During his youth, he was employed as a mail carrier and started living independently since then. He has practiced diverse activities to spend his free time, such as bowling and drawing. Drawing soon became his preferred activity, and he started focusing on it after his 40s (Blackstock et al., Reference Blackstock, Treffert and Light-Pina2006).

Fig. 1. Sunday's Crash, George Weidener from ABCD Art Brut Collection.

After Gregory retired from being a pot scrubber for an athletic club for 25 years, he started to focus more on his art, making it part of his everyday life. The subjects of his artwork are varied: animals, shoes, insects and other objects. His compositions are organised and tend to have titles on the top with a brief description of the work. Titles such as ‘The great world hornbills complete- common the earth's huge tropical far -&- Middle East birds spectaculars, only found in Africa -& - Asia’ are common to read on his artwork.

Fig. 2. The World War II cortissus army fighters, Gregory Blackstock from ABCD Art Brut Collection.

His work is an example of how individuals with autism have a tendency to classify things and repeat patterns, even in their artwork. The repetition could be observed on the subjects he depicts, but also his compositions, the use of colour, and the elements of his drawings. It could suggest that artwork made by this population can ease the development of their particular signature.

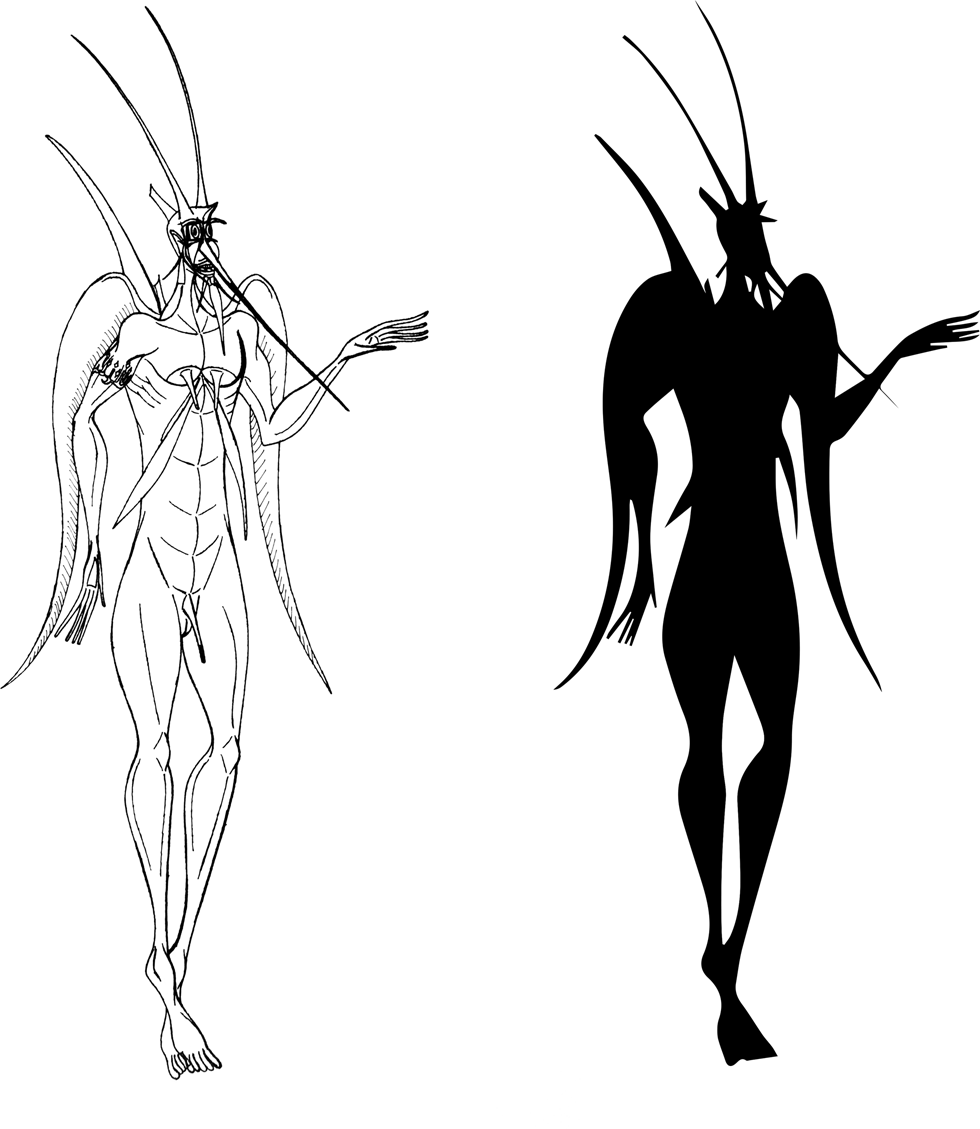

Fatima Calderon started drawing when she was around 15 years old. Her artwork is self-initiated, and for years she has been supported by artists and facilitators in the day centre that she has been attending for several years in La Puebla de Cazalla, Sevilla, Spain.

Fig. 3. Marco Polo Hernamz (MariuMZMarckus).

Fig. 4. Sinichi Sawada sculptures from ABCD Art Brut Collection.

All her characters have ‘Marco’ as their first name; she describes them all with a cobalt blue and black appearance. The way she represents the structure of her creations is crucial for understanding the complexity of the aesthetics of her drawings. She tends to fill the whole body with black colour, which makes it difficult to appreciate the complex anatomy of the character apparent before she takes this step (see above figure). Additionally, the characters represented by Fatima not only show an aesthetic approach, but also have a particular story behind them, like ‘Marco Polo Hernamz (MariuMZMarckus)’:

‘His pseudonym is very long and his name is MariuMZMarckus. He is Marck's older brother and they live in the city of Granada, mainly in the Generalife palace next to the Alambra, he works crafts related to the Muslim and Islamic world. MariuMZMarkus also goes with his brother Marck to the nudist beach of La Herradura to enjoy a few days of rest and they have a great time, they love each other’.

The characters created by Fatima are related, and are classified by different first and last names. Her creations remind of mythological stories and characters because of how she describes them and how they relate with others. There is a misconception associated with autism, generally perceived as characterised by rigid thinking and restricted interests. This can lead to the idea that people with autism normally are attached to what is in their environment and lack creativity. Fatima's work refutes this, offering a prominent example of these inner mythologies with her vast creativity.

Sinichi Sawada's work is a never-ending cycle full of constant repetitions. Mantras and tribal percussion enable individuals to meditate or reach the trance state (García, Reference García2012). For Jung, repetition was an association with a primitive pattern through which we come into contact with the collective unconscious (Jung, Reference Jung1966). Repetition is a recurrent element observed on artwork from outsider artists, permeating through the materials they use, the elements, thematics and compositions in their work.

He was born in 1987 in Shiga, Japan; Sawada is diagnosed with autism and rarely speaks. He creates fantastical clay beings such as daemons, reptilian beasts and ocean creatures (Sharmacharja, Reference Sharmacharja2016). Repetition is observed in his work in the creation of very similar creatures, using his technique of filling all of them with spikes. The shapes of the creatures and compositions have a particular signature.

The work of Sawada is an example of people creating from the inner creative impulse and his own mythologies, which don't have a direct style or thematic relation with Japanese culture. His artwork resembles the roots of the meaning of the magical relation between man and clay, where it is known that clay was used to insufflate life (Amiran, Reference Amiran1962). Despite his congenital handicap and his speaking difficulties, his work is loaded with energy and can communicate his inner world completely. His mythology is not only part of his thoughts, but also he metaphorically insufflated life into them through clay. This is reminiscent of the way ancient cultures used to give form to their beliefs (Kakar, Reference Kakar1982).

The artists explored in this paper have shown their inner world through art; there are plenty of other cases where people with autism share their creativity by plastering it with different techniques. These archetypal practices could be linked to therapeutic purposes, but could also have deeper connections with routes of ancient ways of thinking, by channelling the inner impulses of creative manifestations (Jung, Reference Jung, Harris and Woolfson2015).

Art has the particularity of making us perceive social conditions, through the eyes of a particular individual's experience (Potash et al., Reference Potash, Ho and Ho2018). This generates a relation with the motivations and instincts that have moved humanity and have taken different forms in different nations. If humans recourse to myths and stories to understand each other and their reality, it could be possible that people with autism, for whom it's difficult to connect with the outside world, could more frequently make use of such creative resources.

About the authors

Ana Karen Gonzalez Barajas is a PhD student at the Department of Social Work and Social Administration at the University of Hong Kong. She has been researching on Outsider Art, principally in Mexico. She is part of the directive committee of the Outsider Art magazine Bric-à-Brac. She conducts social inclusion art-based workshops for women and children in rural communities and people with behavioural, developmental, psychological and cognitive disorders.

Prof. Rainbow Tin Hung Ho, PhD, BCDMT, AThR, REAT, RSMT, CGP, CPA, is Professor of the Department of Social Work and Social Administration, Director of the Centre on Behavioural Health and the Master of Expressive Arts Therapy programme at the University of Hong Kong. She has been working as a researcher, professor, creative arts therapist, dance teacher and performer for many years. She has published extensively in refereed journals, scholarly books and encyclopaedia, and has been the principal investigator of many research projects related to creative and expressive arts therapy, mind-body medicine, psychophysiology, spirituality and physical activity for healthy and clinical populations.

Carole Tansella, Section Editor