The Neolithic Center of the Fertile Crescent

Western Asia was the first primary center of domestication of plants and animals, followed closely by China (Smith Reference Smith1998; Harlan Reference Harlan1998; Bellwood Reference Bellwood2005a).Footnote 1 The presence in the Fertile Crescent of vegetal and animal species that could be domesticated, along with the Crescent’s situation as hub, were factors favoring the emergence of what has been called the “Neolithic Revolution.” During the ninth millennium bce, cereals (emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, barley), pulses (pea, lentil, bitter vetch, chickpea), and a fiber crop (flax) were grown and then domesticated (Tanno and Willcox Reference Tanno and Willcox2006; Feldman and Kislev Reference Feldman and Kislev2007; Colledge and Conolly Reference Colledge and Conolly2007; Fu et al. Reference Fu, Diederichsen and Allaby2012). Animals (goats, sheep, cattle, and pigs) were domesticated at the same time or slightly later. Agriculture and livestock farming encouraged a process of sedentarization of communities, rendering them able to harvest and to store food that could feed larger populations, and enabling them also to produce textiles and work leather. A change in social organization and a transformation in belief systems accompanied this revolution (Cauvin Reference Cauvin1997). Cohabiting with domesticated animals brought in new diseases that would prove to be efficient weapons for the Neolithic centers in their relations with foreign countries (McNeill Reference McNeill1998b; Diamond Reference Diamond1997). From western Asia, cultivated plants and animals arrived in Turkmenistan and in the Indus valley (Mehrgarh) during the seventh millennium; these arrivals reveal terrestrial and perhaps maritime contacts. The diffusion of Asian species occurred as early as the eighth or seventh millennium in Egypt, Greece, and Crete. Even before the expansion of highly stratified societies, long-distance trade was noticeable; obsidian from Anatolia arrived in the Levant and in Mesopotamia, and shells were carried from the Persian Gulf to Mesopotamia, or from coastal Sind to Mehrgarh, during the fifth millennium. Lapis lazuli (originating in northern Afghanistan [Badakshan]), turquoise, and copper have been discovered at Mehrgarh and can be dated to the same period.Footnote 2 Lapis lazuli may have been traded as early as the sixth millennium.Footnote 3

When did the first maritime journeys in the Persian Gulf and along the coasts of South Asia occur? Probably very early on, if we consider the prehistory of the Mediterranean Sea (on Cyprus, the site of Aetokremnos, inhabited by hunter-gatherers, is dated to the tenth millennium bce). There is no reason to suppose that the (pre-)Neolithic Arab and Asian societies did not develop the same skills in navigation.

‘Ubaid, a Proto-State Phase

Favored by progress in irrigation, visible at Eridu, Larsa, and Choga Mami (marks left by the use of the ard have been discovered, dated to 4500 bce), demographic and economic growth, and increasing long-distance trade in Mesopotamia: all fueled a first expansionary process from the sixth millennium onward, in the ‘Ubaid period (c. 5300–4100 bce), at least during its phases 3 and 4. This expansion was also based on organizational innovations and a shared ideology, as shown in architecture, and in “seals with near-identical motifs at widely separated sites” (Stein 2009: 135). These changes led to competition between “households” as well as to hierarchies and growing social complexity (Lamberg-Karlovsky Reference Lamberg-Karlovsky, Hudson and Levine1999: 181), which in turn encouraged the populations to invest in new techniques. A monumental architecture developed with the first proto-urban centers. As Stein expresses it, sites such as Eridu, Uqair (Iraq), and Zeidan (Syria) were “ancient towns on the threshold of urban civilization” (2009: 136). The Late ‘Ubaid phases clearly “provide the prototype for the Mesopotamian city” (Oates Reference Oates, Renfrew and Bahn2014a: 1484). The successive “temples” at Eridu in particular – public buildings probably serving various functions – marked the emergence of a new type of social organization, overtaking kinship-based structures. Exhibiting niches and buttresses, erected on terraces (prefiguring the later ziggurat),Footnote 4 temples became larger during the ‘Ubaid 4 period, toward the end of the fifth millennium. It is likely that a private sector already coexisted with a public sector, with interactions and structuring of power relations among the rulers of family households (extended families and their dependants), temples, and councils representing territorial communities. Within the concurrent process of political centralization, control over the temples may have already been a crucial issue (Lamberg-Karlovsky Reference Lamberg-Karlovsky, Hudson and Levine1996: 82–84). The presence of fine ceramics and of stamp seals as well as evidence for a weaving industry in the “temples” of the urban center of EriduFootnote 5 reveal an economic role that goes well beyond that of “food banks” redistributing agricultural resources.Footnote 6 “A Late ‘Ubaid cemetery at Eridu, however, reveals little evidence of the social differentiation attested to in the architecture of either Eridu or sites like Zeidan and Uqair” (Oates 2014: 1481).

Agriculture and livestock farming progressed during this period. Culture of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) probably began during the sixth millennium (see below). The fifth millennium saw the development of the olive tree in the Levant, and of grapevine culture in Georgia, southern Turkey, Iran, and the Levant (McGovern Reference McGovern2003). The rise of tree fruit production went along with exchanges. This would become more apparent during the period of urbanization. Moreover, sheep farming developed in Iran and neighboring regions for the production of wool, thus laying the foundation for a textile industry.

The ‘Ubaid culture expanded in different directions during the ‘Ubaid 3 phase. The Mesopotamians acquired prestige goods and the raw materials they needed by building maritime and terrestrial networks, probably by exporting textiles, leather, and agricultural products. In the Persian Gulf, the Ubaidians practiced fishing and exchanged goods with coastal Arab communities. They brought in domesticated animals and plants, and allowed for the spread of shipbuilding techniques. ‘Ubaid pottery has been discovered at over sixty sites in eastern Saudi Arabia and Oman; it is mainly dated to the ‘Ubaid 2/3, ‘Ubaid 3 periods and to a lesser extent ‘Ubaid 4 (Carter Reference Carter2006).Footnote 7 Contacts stopped during the ‘Ubaid 5 period. Arab communities played an active role in exchanges, along the coasts and in the Arabian interior (Boivin and Fuller Reference Boivin and Fuller2009), where trade networks carried myrrh and incense from the Dhofar and the Hadramawt (Zarins Reference Zarins, Cleuziou, Tosi and Zarins2002). Large quantities of ‘Ubaid (3–4, c. 4500–4100) pottery have been found at Ain Qannas (al-Hufūf oasis), located inland, as well as some remains of cattle and goats (Potts Reference Potts1990: 44). Also traded were obsidian (from Yemen or Ethiopia?), shells, shell beads, dried fish, and stone vessels, through the oasis of Yabrin and al-Hasa.Footnote 8 Shells of the Cypraea type have been discovered in fifth-millennium levels at Chaga Bazar in northern Syria, imported from the Gulf.Footnote 9 An interesting result of the excavation on Dalma Island is the discovery of charred date pits (probably from cultivated date palms); these dates may have been brought there via trade exchanges, or perhaps they were cultivated on the island (they are dated to the end of the sixth/beginning of the fifth millennium). Remains of fruit have also been unearthed at as-Ṣabīya (Kuwait) dated to the second half of the sixth millennium (dates would have great importance in food and trade from the third millennium onward).Footnote 10 Recent genetic research tends to support a Mesopotamian origin for date-palm domestication (Rhouma et al. Reference Rhouma, Dakhlaoui-Dkhil, Ould Mohamed Salem, Zehdi-Azouzi, Rhouma, Marrakchi and Trifi2008). The presence of carnelian beads (a stone originating in Iran or the Indus) is noteworthy at Qatari sites, along with Mesopotamian pottery. Carnelian beads have also been discovered in Mesopotamia dating from the ‘Ubaid period (Inizan Reference Inizan and Caubet1999).

At that time, Arabia was undergoing a subpluvial phase (7000–4000 bce) marked by a strong summer monsoon; the Intertropical Convergence Zone was located 10° north of its modern position. Weaker monsoons and a southward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone were accompanied by growing aridization; this put an end to the use of the inland routes at the start of the third millennium (Zarins Reference Zarins, Cleuziou, Tosi and Zarins2002: 409ff.).Footnote 11

The first Mesopotamian explorations in what was known as the “Lower Sea” favored the diffusion of shipbuilding techniques. Excavations at as-Ṣabīya (Kuwait, ‘Ubaid 2/3 period) have unearthed bitumen which was used to caulk reed ships. The site yielded a terracotta model of these boats, which were of Mesopotamian design.Footnote 12 Probably carried on the inland routes of Arabia, obsidian which may have come from Yemen was discovered along with the remains of these boats. As-Ṣabīya yielded a painted disc featuring a boat with a sail supported by a bipod mast (Carter Reference Carter2006: 54–55 figs. 3 and 4). Clay boat models from the cemetery of Eridu also show the use of a sail at the end of the ‘Ubaid period;Footnote 13 these models appear to represent wooden ships, as does the model found in Syria at Tell Mashnaqa (Potts Reference Potts1997: 125). The role of the ‘Ubaidians should not obscure the existence of other networks, operated by Arab communities, along the coasts and in the interior of the Arabian peninsula (Cleuziou and Méry Reference Cleuziou, Méry, Cleuziou, Tosi and Zarins2002: 303; Boivin and Fuller Reference Boivin and Fuller2009: 126ff.). The location of the sites in the Gulf suggests that the ‘Ubaid pottery found beyond Bahrain was probably carried by local communities, who used seagoing ships,Footnote 14 as revealed by tuna fishing – tuna was eaten and prepared for export by Omani communities during the fourth millennium. This pottery was considered a luxury item: sites in outlying areas produced imitations of the ‘Ubaid pottery (Carter Reference Carter2006: 59).

The ‘Ubaid culture also extended eastward into Khuzistan, where Susa constituted a proto-urban center. It also extended north of Mesopotamia (especially during the Late ‘Ubaid phase), toward routes already linking Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the upper valleys of the Tigris and the Euphrates: one finds Ubaid pottery as far as the Transcaucasus region, and lapis lazuli from Afghanistan is present at Tell Arpachiyah and Nineveh, in northeast Iraq; Tepe Gawra yielded lapis lazuli, as well as carnelian from Iran, but the blue stone could be more recent at this site.Footnote 15 Pottery from Susa, dated to the late fifth millennium, has been found further east in Iran, in a region rich in copper. The quest for copper obviously played a crucial role in ‘Ubaid and ‘Ubaid-related expansion, as shown by the ‘Ubaid “colony” of Deǧirmentepe, which was located near substantial copper, lead, and silver sources (Oates and Oates Reference Oates and Postgate2004).Footnote 16 Trade in copper and exotic goods favored a process of social differentiation, not only at Gawra, which Oates (2014: 1481) considers as “a northern Ubaid settlement,” but also at Zeidan (12.5 ha), in northern Syria (Euphrates River valley), a site revealing monumental architecture.Footnote 17 Zeidan yielded evidence for copper metallurgy and administrative activity (a stamp seal has been found, dated to c. 4100 bce) (Stein 2009: 134). At Susa, a settlement founded around the end of the ‘Ubaid period rapidly grew to cover 10 ha. It included a high platform bearing a building (residence, warehouse). Seals and imprints have been discovered, with geometric and sometimes figurative designs (the motif of the “master of animals” is already present) (Pollock Reference Pollock1999: 90ff.).Footnote 18 During this period, Mesopotamia formed itself into a “central civilization” (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson and Sanderson1995a). This expansion was accompanied by new social complexity in different regions, with the probable emergence of servile labor regulated by family chiefs.Footnote 19 One notes the use of stamp seals in Khuzistan, Luristan and Fars,Footnote 20 as well as in areas north of Mesopotamia.

The homogeneity of the material ‘Ubaid culture implies active exchange networks, at the local level and between regions. Parallels established between the northern temple at Tepe Gawra XIII and buildings at Uruk (tripartite floor plan,Footnote 21 orientation, elaboration) reflect some cultural community and shared beliefs. Religion must have played an important role controlling communities and exchange networks. In 1936, 1952, and 1954, A. Hocart had already pointed out the possible religious origin of trade, and of social and state institutions. Moreover, ceramics made on the turnette (slow wheel) and the use of stamp seals can be observed throughout the ‘Ubaid area: the diffusion of these technologies contributed to the homogenization of this space (Nissen Reference Nissen and Rothman2001). A marked increase in the use of seals and mass-produced pottery (suggesting the distribution of rations) signal new social complexity. Seals and other devices reveal administrative activity. At Tell Abada, in east central Iraq, in ‘Ubaid buildings, tokens have been found in pottery vessels, probably reflecting the keeping of records (Oates 2014: 1482).

The expansion of the ‘Ubaid culture during the fifth millennium clearly shows the new dimension of the exchange networks, brought about principally by the rise of copper metallurgy. This technology appeared during the sixth millennium in Anatolia, and during the fifth millennium in Mesopotamia, Iran, Pakistan, and southeastern Europe.Footnote 22 It then spread to the north of the Black Sea (4400 bce), and on to the Middle Danube valley (4000 bce), to Sicily and the southern Iberian peninsula (3800 bce).Footnote 23 This progression provides clear evidence for the expansion of exchange networks. Metalworking reached the Asian steppes from southern Russia during the fourth millennium. It would later spread to northwestern Europe around 2500 bce. Copper and then bronze metallurgy required a supply of metal ore and an ability to transport it; thus new trade networks were set up on a larger scale, within social contexts that implied profound ideological and organizational changes. The ‘Ubaid civilization acted as a catalyst for societies further north and east of Mesopotamia, with long-distance trade now involving a large area.

The end of the ‘Ubaid phase c. 4100 bce seems to have coincided with a period of global cooling and aridization in the eastern Mediterranean region and the Levant (Staubwasser and Weiss Reference Staubwasser and Weiss2006). In Susiana, “even the Acropole of Susa was abandoned ca. 4000” (Wright Reference Wright and Petrie2013: 52). The ‘Ubaid period prefigures the flowering of the Sumerian civilization during the Urukian period.

The Urban Revolution and the Development of the State in Mesopotamia

The First Half of the Fourth Millennium bce

New progress in metallurgy was noteworthy during the fourth millennium. Anatolian sites operated mines (mainly in the region of Ergani) and practiced ore smelting (Çatal Hüyük, Tepeçik, Deǧirmentepe, Norşuntepe …). There are clues indicating copper metallurgy at Mehrgarh (Pakistan) before 4000 bce. A wheel-shaped amulet from Mehrgarh has recently been identified as the oldest known artifact made by lost-wax casting (it is dated to between 4500 and 3600 bce) (Thoury et al. Reference Thoury, Mille, Séverin-Fabiani, Robbiola, Réfrégiers, Jarrige and Bertrand2016). It had been thought that tin bronze was produced at Mundigak (Afghanistan) during the second half of the fourth millennium, but recent reanalyses show no evidence of tin bronze (Pigott Reference Pigott, Jett, McCarthy and Douglas2012a).Footnote 24 Feinan (Jordan) has been dated to between 3600 and 3100 bce for copper ore mining (Hauptmann Reference Hauptmann, Craddock and Lang2003: 91). This progress in metallurgy and the transportation of various goods (not only raw materials but also manufactured products) probably explains why active trade routes were established during this period. These routes would remain of importance throughout the ensuing two millennia. The first bronze tools appear at Beycesultan around 4000 bce, and at Aphrodisias around 4300 bce (southwestern Turkey) (Joukowsky Reference Joukowsky1996: 143). Beycesultan also yields silver items very early on.

After the ‘Ubaid period, eastern Anatolia took advantage of improved climate conditions and a fresh increase in exchanges. This region, along with northern Mesopotamia, saw the formation of proto-urban centers (Arslantepe, Hacınebi, Tepe Gawra, and most importantly, Khirbat al-Fakhar and Tell Brak)Footnote 25 (see Map i.1). Societies in Syria and Anatolia were already showing complex organizational characteristics during the first half of the fourth millennium, before “the documentation of regular contacts with the southern Uruk world” (Philip Reference Philip and Postgate2004: 209).Footnote 26 Public buildings were erected at Arslantepe during phase VII, before the period of contact with the Urukian world.Footnote 27 Godin (VI) was also expanding during the first half of the fourth millennium.Footnote 28 Hacınebi shows some social complexity during a phase dated 4100–3700 bce, with stone architecture, administrative activity (stamp seals,Footnote 29 also found at Gawra, Tell Brak, Arslantepe, Deǧirmentepe), and metallurgy. Hacınebi was involved in exchanges between the Mediterranean, the Euphrates and Tigris valleys, and regions further east; it yielded artifacts made from chlorite, a stone imported from a region located 300 km to the east, shells termed “cowries” (Mediterranean shells?), some bitumen (from Mesopotamia), copper items (the metal probably came from the region of Ergani and/or from the Caucasus), and even silver earrings.Footnote 30 In northeastern Iraq, Khirbat al-Fakhar was a much larger proto-urban settlement – of low density – covering 300 ha, whereas the total area of the Late Chalcolithic 2 (LC2) (4100–3800 bce) settlement at Brak reached at least 55 ha (Ur Reference Ur2010: 395). At this time, Rothman has reported the existence of specialized “temple” institutions at Tepe Gawra (Rothman Reference Rothman, Rothman and Fe2001b: 387–389), Tell Hammam et-Turkman, and Tell Brak (McMahon and Oates Reference McMahon and Oates2007: 148–155). “At Tell Brak, adjacent to a monumental building was a structure with abundant evidence for the manufacture of various craft items. The structure itself contained obsidian, spindle whorls, mother-of-pearl inlays, … ” (Ur Reference Ur2010: 394; see Oates et al. Reference Oates, McMahon, Karsgaard, Al Quntar and Ur2007). Mass-produced ceramics have been found, along with “a unique, obsidian and white marble ‘chalice’ ” (Oates et al. Reference Oates, McMahon, Karsgaard, Al Quntar and Ur2007: 591, 594), showing the existence of social differentiation and organized labor.

These (proto-)urban centers constituted nodes along east–west networks that extended further into Iran and Afghanistan, in one direction, and to the Syrian coast in the other. Lapis lazuli has been found at Iranian sites such as Tepe Sialk, Tepe Giyan (first half of the fourth millennium bce), Tepe Yahya (3750–3650 bce), and in northern Mesopotamia, at Tepe Gawra (3200 bce?), Nineveh, Arpachiyah (4500–3900 bce) (Casanova Reference Casanova2013: 27ff.). “There was extensive evidence for exploitation of lapis lazuli at Tepe Hissar during the 4th millennium BCE” (Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013a: 7). The presence of lapis lazuli reveals the existence of routes linking Central Asia, Iran, and northern Mesopotamia; it is rare, however, during the ‘Ubaid period and the first half of the fourth millennium. Moreover, trade networks formed with northern regions: obsidian came from central or eastern Anatolia, and “ceramics [from northern Mesopotamia] have been found in eastern Anatolia (Marro Reference Marro and Lyonnet2007) and in Azerbaijan (Akhundov Reference Akhundov and Lyonnet2007)” (Ur Reference Ur2010: 395). Interactions between the spheres of Anatolia–Levant and Mesopotamia took place during the flourishing of the ‘Ubaid culture; they continued after its demise. On the basis of glyptic art, H. Pittman notes “a shared symbolic ideology” during the Late ‘Ubaid–Early Uruk in Syria, northern Mesopotamia, and Khuzistan (2001b: 418).

During the LC2 period, the first proto-urban centers seem to have lacked internal political centralization. But from the LC3 period (3800–3600 bce), Tell Brak grew into a large urban center, becoming a dense settlement of 130 ha, “prior to the Uruk expansion” (Oates et al. Reference Oates, McMahon, Karsgaard, Al Quntar and Ur2007, Ur Reference Ur2010: 396).Footnote 31 Another major site was located at al-Hawa, 40 km east of Hamoukar; it may have been as large as 33–50 ha. Hamoukar (near Khirbat al-Fakhar) and Leilan were smaller settlements. According to Algaze, however, Hawa and Samsat – a city now submerged as a result of the construction of the Ataturk dam – truly developed “after the onset of contacts with the Uruk world” (Reference Algaze2008: 120).

Domestic structures in Tell Brak “show evidence of high-value items and exotic materials,” and of property-control mechanisms. “A cache from a pit included two stamp seals and 350 beads, mostly of carnelian but also silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and rock crystal (Emberling and McDonald, Reference Emberling and McDonald2003, p. 9)” (Ur Reference Ur2010: 396). Seals and sealings have also been discovered at Hamoukar (Reichel Reference Reichel2002).

Quoting Algaze (Reference Algaze2008: 118ff.), Ur notes that “Brak’s urban significance has been downplayed because, unlike the cities of southern Mesopotamia, it was a primate center without intermediate centers in a proper urban hierarchy” (Ur Reference Ur2010: 399).

The process of urbanization was accompanied by violence: traces of massacres have been discovered in Tell Brak, and structures were destroyed by fire at Hamoukar and Brak. Whether due to internal disorderFootnote 32 or attacks by southerners, the origin of this violence is still debated.Footnote 33 Also debated is the dating of the Eye Temple at Tell Brak. For Oates et al. (Reference Oates, McMahon, Karsgaard, Al Quntar and Ur2007: 596), it was built prior to the Uruk expansion, in the LC3 period (3800–3600 bce), but other archaeologists date the construction of the temple to 3500–3300 bce. The temple was decorated with clay cones, copper panels, and goldwork, in a style similar to contemporary temples of southern Mesopotamia. “Eye idols have also been found at Tell Hamoukar (Reichel Reference Reichel2002)” (Oates et al. Reference Oates, McMahon, Karsgaard, Al Quntar and Ur2007: 596).

The Urukian Expansion during the Second Half of the Fourth Millennium bce

Interactions with southern Mesopotamia can be seen from 3600 bce onward, when the latter region experienced major urban development accompanying the birth of the state. As Algaze makes clear, “polities in the north hardly equaled their southern counterparts” (Reference Algaze2008: 120). This southern urban development was based on agricultural progress generating demographic growth. Increased irrigation, the use of the ard drawn by oxen and the creation of date-palm plantations led to the creation of large estates; only estates of significant size were able to invest on a scale ensuring surpluses that supported urbanization.Footnote 34 Sherratt (Reference Sherratt, Pétrequin, Arbogast, Pétrequin, van Willigen and Bailly2006a) has shown convincingly that the ard was developed along with the urbanization process; it may have been first employed to make furrows for irrigation; it required a major investment, which in turn explains its symbolic link with political power. The use of sledges on rollers to remove seed husks heralded the invention of the wheel.

Urbanization was also based on the progress of various crafts, such as ceramics (the invention of the potter’s wheel made mass production possible, and this was linked to new social practices [the use of fermented beverages]Footnote 35 and organization [distribution of rations]), metal artifacts, and textiles made of flax or wool (see below). Growth in sheep populations is seen at several Urukian sites at the end of the fourth millennium (such as Tell Rubeidheh); this may have been spurred by the state leadership (Kohl Reference Kohl2007: 222).Footnote 36 Sheep production certainly represented one driver of the Uruk expansion.Footnote 37 Selected in Iran, wool-bearing sheep breeds spread rapidly westward: some of the first-known wool remains, dated to the late fourth millennium, come from El Omari, in Egypt (Good Reference Good and Mair1998: 658).

The production of new goods was connected to the building of hierarchized urban societies; not only did exported manufactured goods lay the groundwork for an asymmetric exchange with peripheral regions; they also fostered local developments (the social role of fermented beverages in Mesopotamia, for example, may have led to expansion in grapevine culture on the Mediterranean shores, as Sherratt has suggested).

The Urban Revolution benefited from increased long-distance trade, and helped further its development; commerce first involved textiles, slaves, and copper, which was used to produce weapons and tools. The development of copper and later, bronze metallurgy underlay the emergence of political power: “only elites could organize the long-distance procurements of costly copper and tin, as both were scarce,” and both proved necessary to social reproduction (Ratnagar Reference Ratnagar and Chakravarti2001a: 355). Bronze was initially an alloy of copper and arsenic,Footnote 38 then of copper and tin (the latter alloy being harder than the arsenical bronze).Footnote 39 Bronze metallurgy spread from the fourth millennium onward, through the trade routes, with a possible diffusion to China between 3000 and 2000 bce (Pernicka et al. Reference Pernicka, Eibner, Öztunall, Wagner, Wagner, Pernicka and Uerpmann2003). The production of bronze artifacts increased not only agricultural productivity,Footnote 40 but also military power: competition between cities was not always peaceful, and the extension of conflicts certainly played an important role in the building of the state.

The rise in exchanges was partly linked to the birth of a new ideology of political control as well as to institutional innovations. The state played a crucial role, organizing production and exchanges, as well as redistributing wealth.

In conjunction with the rise in exchanges and processes of internal development, southern Mesopotamia experienced a radical new flourishing. Already inhabited c. 4600 bce, the site of Uruk (Warka) grew from 3600 bce (Middle Uruk) and covered 250 ha c. 3100 bce – which may have represented a population of 20,000 to 40,000 – and 600 ha c. 2900 bce at the end of the Jemdet Nasr period (according to Morris [Reference Morris2013: 153], Uruk had 45,000–50,000 inhabitants by the late fourth millennium). During the Early Uruk period, the city of Warka grew “at the expense of the Nippur-Adab and Eridu-Ur areas” and of Upper Mesopotamia (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 108, 110; Kouchoukos and Wilkinson Reference Kouchoukos, Wilkinson and Stone2007): the population of the northern Jazirah decreased, especially from 3500 to 3300 bce; the same held true for the Fars Plain; northern cities (Tell Brak, Hamoukar) grew smaller, leading Algaze to speak here of an “aborted urbanism” (Reference Algaze2008: 117, 121). Other southern cities probably expanded during the late fourth millennium, absorbing rural populations: Nippur, Adab, Kish, Girsu, Ur, Umma, Tell al-Hayyad. None of these cities, however, are comparable to Uruk.Footnote 41 Algaze rightly emphasizes that “large settlement agglomerations were almost certainly unable to demographically reproduce themselves without a constant stream of new population” (Reference Algaze2008: 29). (McNeill [Reference McNeill, Denemark, Friedman, Gills and Modelski2000: 204] “pointed out intensified mortality as a result of crowding, with the appearance of a variety of diseases.”)

Various authors have stressed the importance of the ideological and organizational changes occurring during the birth of the state.Footnote 42 The Mesopotamian agglomerations probably meet the criteria proposed by Wengrow for defining a city: “the existence of a class or classes of individuals not directly involved in agrarian production, a high density of permanent residents, access to ports and trade routes, centralized bureaucracy,Footnote 43 a concentration of knowledge and specialised crafts, political and/or economic control over a rural hinterland, the existence of institutions that embody civic identity,” and the monumentality of some of its buildings (Wengrow Reference Wengrow2006: 76–77). These towns or cities constituted – at one and the same time – political, economic, and religious centers. It is possible that chiefs were primarily religious chiefs. Political power may have emerged as the result of the internal dynamics of the royal system: “It was only when the [various] ritual functions of the [chief] were separated from one another that political power and state organization emerged and developed” (Scubla Reference 742Scubla2003; Hocart Reference Hocart1970). L. de Heusch also writes: “It is the symbolic construction elaborated on the figure of a magician-chief that allows the genesis of the state, wherever a hierarchy of status or social classes develops” (Reference Heusch1997: 230).

Not only was there intensification of labor through biological, technological, and organizational innovations; there was also a more efficient mobilization of the labor force itself. Southern Mesopotamian cities proved better able “to amass and control information, labor and surpluses vis-à-vis those of their immediate neighbors” (Algaze Reference Algaze and Rothman2001: 70). This efficiency was seen in both economic and political-religious organization. Community lands held by extended families came under the management of “institutional households.” The temples, which owned land, craft workshops and herds, were organized as “profit centers” (Hudson Reference Hudson, Hudson and Levine1996: 37). The growing importance of the temple complexFootnote 44 paralleled the emergence of a ruling class that was organized as an assembly of community leaders, who managed most of the production and long-distance trade.Footnote 45 According to Pollock, the Uruk rulers probably extracted tribute to feed the city. Uruk was the religious capital of Sumer (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 114), and may also have been the political capital of a Sumerian state (Yoffee Reference Yoffee and Sasson1995b; Westenholz Reference Westenholz and Hansen2002; Matthews Reference Matthews2003).Footnote 46 Various elements, however, do suggest the existence of a league of Sumerian cities around 3100 bce (rather than a single state), a league perhaps headed – as later in the third millennium – by a LUGAL (“great man”), “ceremonial head of the assembly [UNKEN] of city rulers.”Footnote 47 For Glassner, there was no king yet at the head of the state: an assembly of community leaders was “managing the affairs of the city.”Footnote 48 Twenty cities are thus mentioned on a seal, from Urum (Tell Uqair) in the north to Ur in the south. Remains of temples and “palaces” have been discovered; they show decorations of niches and pilasters as well as characteristic facade ornamentation using colored “nails” forming geometrical patterns.Footnote 49 Algaze (Reference Algaze2008: 190), however, believes that kingship was already instituted. The “Titles and professions list” during the Jemdet Nast period starts with a man called NAM2+ESDA, a term translated as “king” during the second half of the 3rd millennium. Moreover, Algaze emphasizes an “iconographic continuity between the 4th and the 3rd millennia for the ‘priest-king/city ruler’” (Reference Algaze2008: 190, 153). The true nature of the Urukian institutions, in fact, remains unknown.

Some ceramic objects – beveled-rim bowls – were mass-produced and standardized, probably reflecting the distribution of “rations,”Footnote 50 in “a system of mass labor” clearly made visible through the size of public buildings;Footnote 51 these rations may also have been linked to workshops producing goods for the state such as textiles. “Many of the Archaic texts record disbursement of textiles and grain to individuals. [They may represent] rations given to some sort of fully or partly dependent workers” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 130). In S. Pollock’s view, during the third millennium, the economy moved from a tributary system (tributes were extracted from the rural sector) to a system of “households” employing their own labor forces, servile or not; these “houses” were not only temples and palaces, but also estates belonging to high-level officials or the rulers of extended families.Footnote 52 As early as the Urukian period, the archives of the institutional estates evoke the management of land, of herds, and of the labor force (Glassner Reference Glassner2000a: 238ff.), probably with economic viability in mind: here we are outside the context of a simple tributary system.

The emergence of the state and the rise of exchanges brought about the use of new techniques that spread widely, allowing for growing control over the movement of goods, information, and individuals. Calculi and seals on clay bullae containing these calculi represent systems noting quantities that reveal accounting management. They can be found in a vast zone going from Iran to Mesopotamia and Syria: all of western Asia was involved.Footnote 53 At Uruk, then at Susa, around 3500 bce (or slightly later?),Footnote 54 cylinder seals appeared (only stamp seals had been used in earlier times) to seal merchandise (bales or jars) and doors.Footnote 55 Numerical tablets, each one sealed by the imprint of a cylinder seal, have been unearthed in levels belonging to this period.Footnote 56 With the development of cylinder seals, a new iconography flourished that legitimated the power of the elite: it often figures a hero – perhaps already a “priest-king” or deity? (see above) – who is a master of wild beasts, a war leader, a feeder of domestic animals and “a fountain of agricultural wealth” (the hero holds a vase with flowing streams, a symbol of abundance and a possible reference to the role of the state in irrigation systems); he is alternately portrayed as an officiator in religious ceremonies (according to Glassner [Reference Glassner2000a], however, versus Algaze [Reference Algaze2008], the seals and cultic objects feature different characters, not just one). We can observe this iconography from early periods in Iran and Egypt. For Pittman, in fact, “the characteristic Uruk imagery was first developed and found its richest expression in Susiana” (Reference Pittman and Petrie2013: 295). At Susa and Choga Mish, east of Susa, cylinder seal impressions show temples on high platforms (Oates Reference Oates, Renfrew and Bahn2014a: 1491; Amiet Reference Amiet1980: 695).

The Susiana Plain was “part of the Uruk world between 3800 and 3150 bc” (Wright Reference Wright and Petrie2013: 63); it is likely, however, that during the Early and Middle Uruk periods, “an independent state based at Susa developed in Susiana” (Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013b: 388). For her part, Pittman (Reference Pittman and Petrie2013) “queries the primacy of southern Mesopotamia in the development of the administrative innovations that took place in the 4th millennium” (Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013b: 391). For Pittman (Reference Pittman and Petrie2013: 321), Susa was the source of many of the “Mesopotamian” innovations. One notes the appearance “of bevel-rim bowls and other Uruk forms at Ghabristan, Sialk, Tal-e Kureh and possibly Tal-e Iblis” (Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013b: 13): the question remains to know whether we observe a process of colonization, trade, or emulation/coevolutionFootnote 57 (at Susa for example, and from Susa) (Rothman Reference Rothman, Rothman and Fe2001b: 21).

Copper metallurgy developed in Iran during the fourth millennium bce, using crucible-based smelting technology, for example at Tal-e Iblis (periods III and IV), Tepe Sialk (III and IV), Tepe Hissar (II), Tepe Ghabristan (II), Arisman, Godin Tepe (VI.1), and Susa (Weeks Reference Weeks and Petrie2013). We do not have evidence of ancient mining at Anarak, but local mineral sources must have been used. Iran exported copper and copper artifacts.

The juridical power of the state was constituted at this time. We know from Nissen that “group size and amount and level of conflicts are systematically and inseparably interconnected”; the dimension of Uruk implies the setting up of a system of laws and sanctions, as well as an organization that is able to implement them (Nissen Reference Nissen and Postgate2004: 14).

Among the crucial innovations of the Urban Revolution figure techniques of power and new forms of organization. Bullae, calculi, and cylinder seals have already been mentioned. The first signs of writing appeared around 3300 bce at Uruk (the exact period is not known), in response to the growing complexity of commercial transactions and social organization, and to the building of a system of relations between the Sumerian city-states, interacting with a periphery of pastoralist or sedentary populations.Footnote 58 The development of writing laid the groundwork for the state’s ideology, with the creation of a body of scribes whose apprenticeship must have also been an “indoctrination” (Pollock Reference Pollock1999: 169). Writing quickly acquired a sacred dimension: along with iconography, it brought about contact with the world of the gods. In the economic field, most of the ancient documents contain lists of goods that were received, sent, or stored, such as grains, milk products, wool, textiles, metals … Some of these documents show attempts at economic planning. They have usually been found in the vicinity of public buildings.Footnote 59 A vast majority of tablets thus reflect the existence of a centralized and hierarchized administration. Archaic texts from Uruk refer to social differentiation and the organization of various professions.Footnote 60 They reveal the existence of slaves of local or foreign origin. “A larger pool of dependent labor available gave a comparative advantage” to southern Mesopotamia (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 81). Slaves probably worked on irrigation systems and constructions. As Algaze rightly points out (Reference Algaze2008: 146–147), “innovations in communication [writing, accounting systems], [transportation] and labor control were fundamental for the Sumerian takeoff.” The city of Uruk was crisscrossed by canals used for transport and irrigation.

Slaves also worked in workshops. “The second most frequently mentioned commodity in Archaic texts [after barley] is female slaves” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 129). A tablet from Uruk refers to 211 women slaves, who produced textiles for the temple.Footnote 61 Many Uruk texts deal with wool and textiles (woven woolen cloth),Footnote 62 which probably represented the first exports of the Mesopotamian cities, in addition to leather, agricultural products, perfumed oils, and metal artifacts. During the third millennium, “iconography from cylinder seals and sealings depict various stages of textile production” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 81). Archaic texts “attest to the existence of temple/state-controlled sheep herds” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 87).Footnote 63 It is likely, also, that raw wool imports contributed to the growth of the textile industry in the southern Mesopotamian cities. Wool, notes Algaze (Reference Algaze2008: 79), was more easily dyed than linen, and “economies of scale were achievable by using wool as opposed to flax.” “The mass production of textiles” financed by elites was clearly “an urban phenomenon” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 84). “The earliest economic records and lexical lists also include numerous references to metals” (Reference Algaze2008: 93) (see below). In sum, the flourishing of different crafts linked to institutions can be observed. Southern Mesopotamia had at least two other crucial advantages over the north: a higher density of population and efficient water transport, facilitating trade.Footnote 64 The Mesopotamian elites ensured the supply of necessary raw materials: metals, stone, and wood. There is little doubt that the state was involved in long-distance trade.Footnote 65 During the second half of the fourth millennium, exchanges benefited from innovations in transportation: waterway development, clearly visible at Uruk; improvements in shipbuilding; domestication of the donkey (both in Egypt and in western Asia) and the use of the wheel. A written sign reflects the presence of donkeys during the Uruk period. Recent genetic research shows that donkey domestication first took place in Egypt, from a Nubian subspecies, Equus asinus africanus (the first remains of domesticated donkeys were discovered in a Predynastic tomb, at Ma’adi, dated c. 4500 bce). A second domestication occurred from another subspecies related to Equus asinus somaliense, but another breed – today extinct – may have lived between Yemen and the Levant; it may have been the ancestor of this second domesticated set (Beja-Pereira et al. Reference Beja-Pereira, England, Ferrand, Jordan, Bakhiet, Abdalla, Mashkour, Jordana, Taberlet and Luikart2004; Vila et al. Reference Vilà, Leonard, Beija-Pereira, Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006). Wild donkeys may have been domesticated in Mesopotamia (Uerpmann Reference Uerpmann and Pearsall2008: 441), where remains are dated to the Middle Uruk period at Tell Rubeidheh, in the Diyala valley. As already mentioned, the wheel was probably developed in northern Mesopotamia, Syria, or eastern Anatolia at the time of the Urukian expansion (Sherratt Reference Sherratt, Pétrequin, Arbogast, Pétrequin, van Willigen and Bailly2006a).Footnote 66 From Anatolia, use of the wheel and the wagon spread along the Danube and the Black Sea. Their arrival went along with the dislocation of the large villages of the Cucuteni-Tripol’ye culture (located between the Dnieper and the Danube) around 3600/3500 bce, during an ecological crisis brought about by a climatic aridification and a degradation of the environment linked to anthropogenic activities.Footnote 67 We cannot exclude a diffusion of wheel and cart through the Caucasus. The remains of a wagon found in a kurgan at Starokorsunskaja (Maykop culture) have been dated to c. 3500 bce (Trifonov Reference Trifonov, Fansa and Burmeister2004; Primas Reference Primas2007). Clay models of wheels have also been excavated from the earliest levels at the site of Velikent (same period) (northeastern Caucasus) (Kohl Reference Kohl2007: 85). The ard and the wheel spread together and rapidly across Europe along pre-existing trade routes, following the Danube valley and other large rivers, such as the Oder, around the middle of the fourth millennium, probably at the same time as innovations such as wool sheep breeding, the preparation of fermented beverages and the use of bivalve molds for casting metal objects.Footnote 68 The adoption of more intensive agricultural practices provided a means of facing the crisis linked to the combination of population surge and climatic deterioration during this period. These diffusions were accompanied by major social transformations. “The use of draught power appears to have been linked to an élite able to mobilize resources; it implied concentration of power and control on herds and therefore on men” (Sherratt Reference Sherratt, Pétrequin, Arbogast, Pétrequin, van Willigen and Bailly2006a: 345).

The crucial aspect of the invention of bronze has already been emphasized. It allowed for the growing production of weapons: besides trade, war played a major role in forming a dominant political elite and in building the state. Texts from Ur, dated to the end of the Urukian period / beginning of the Early Dynastic, refer to hierarchized military organization.Footnote 69 Interestingly, “male slaves [in Archaic texts] are often qualified as being of foreign origin” (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 129).

The need to maintain an adequate flow of imports to ensure the stability and growth of a type of production destined both for the southern Mesopotamian social space and for export partially explains the Uruk expansion to the north and east: it was a complex phenomenon, variable in both space and time (Rothman Reference Rothman and Postgate2004: 57). Not only did the city of Uruk take part in this expansion, but so did Nippur, Kish, Ur, and probably other cities, as suggested by the presence of the gods Enlil and Ninhursag at Mari, and of Ningal at Ugarit during the third millennium.Footnote 70 Mesopotamia needed to import metals, wood, stone, and luxury goods – as these were indispensable for affirming the power of its elites.Footnote 71 Whereas the city had no copper, arsenic, or tin, it managed to develop an elaborate copper and later a bronze industry. The earliest economic tablets already contain a pictogram for a smith (Algaze Reference Algaze2008: 77), and the remains of a foundry showing division of labor have been unearthed at Uruk (Nissen Reference Nissen and Postgate2004: 10). Two types of bronze were used in western Asia: arsenical bronze, found mainly along a north–south axis: the Caucasus;Footnote 72 eastern Anatolia; Palestine; southern Mesopotamia;Footnote 73 and a type of tin bronze appearing in the early third millennium, along an east–west axis: Afghanistan; Anatolia; northern Syria; Cilicia. Imported into southern Mesopotamia prior to the middle of the fourth millennium, copper came from the Iranian plateau, northern Iraq (Tiyari mountains), or eastern Anatolia. Already known in Palestine, the lost-wax casting technique developed both in Mesopotamia and at Susa.Footnote 74 The cupellation process used to separate lead and silver – from galena, a lead ore containing silver – was attested c. 3300 bce at Habuba Kabira, and mid-fourth millennium at Arisman, in the vicinity of the Anarak copper source.Footnote 75

In addition to needs and economic opportunities, ideology probably underpinned both the Urukian expansion and the emergence of ruling elites. Here, as is still the case, religion played several roles: it had an integrative function within a multiethnic population; it represented a kind of sanctification through which leaders could claim legitimacy; and it allowed for the regulation of economic activities when both cooperation and forced labor became necessary.Footnote 76 We must take into account not only religion itself, but a system of thought and practices, along with changes in clothing and food consumption accompanying social hierarchization in Urukian society. The role of religious networks in the Urukian world may explain why cultural signs were maintained, differentiating the southern Mesopotamians and their hosts for several centuries, at sites such as Hacınebi (Anatolia), but the “ideological Sumerian capital” also influenced many societies: the spread of “Urukian” potteries may have been linked to the consumption of fermented beverages embedded in new social relations (Sherratt Reference 744Sherratt, Feinman and Nicolas2004).

The Urukian expansion favored an evolution that had begun earlier in Anatolia and Syria, and built upon it: interactions between the Anatolia–Levant and Mesopotamian spheres took place during the flowering of the ‘Ubaid culture, and continued after the end of the ‘Ubaid period. “Societies from Syria and Anatolia already exhibit complex organisational characteristics in the first part of the 4th millennium, prior to the rise of regular contacts with the Uruk world” (Philip Reference Philip and Postgate2004: 209)Footnote 77 (see above). At the junction of various roads, Tell Brak exhibits links with southern Mesopotamia already during the Middle Uruk period or even earlier.Footnote 78 Tepe Gawra and Arslantepe, though smaller settlements, were craft centers and nodes on exchange networks. Gawra produced textiles. The discovery of annular rimmed vessels which resemble primitive stills implies that perfumes were already being produced in the middle of the fourth millennium (Needham et al. 1980: 82). As Algaze points out (Reference Algaze and Rothman2001: 66ff.), however, the complexity of the northern settlements and their techniques of management and communication of information cannot be compared with those of Uruk and the cities of southern Mesopotamia.Footnote 79 Lapis lazuli is present at sites in Iran such as Tepe Sialk (Middle Uruk/Late Uruk), Tepe Giyan (already in the first half of the fourth millennium bce), Tepe Yahya (3750–3650 bce), and Tepe Hissar (phase 3600–3300, then 3300–3000), where it appears along with silver (perhaps originating in Anatolia, though this origin remains uncertain) (Mark Reference Mark1998: 37). Lapis has been found in northern Mesopotamia, at Arpachiyah, Nineveh (already during the ‘Ubaid period), Tell Brak, Tepe Gawra (Late Uruk?), and Jebel Aruda (before 3200), revealing the existence of trade routes linking Central Asia, Iran, and northern Mesopotamia.Footnote 80 This blue stone was also present in the main southern Mesopotamian cities, during the second half of the fourth millennium: Uruk, Ur, Nippur, Khafajeh, and Telloh – but it remained a rarity prior to the Jemdet Nasr period c. 3100 bce. Moreover, “the intrusion [in Pre-Maykop settlements] of northern Mesopotamian cultural elements or peoples (?) predating the subsequent southern Mesopotamian Uruk expansion” signals exchanges with regions beyond the Caucasus (Kohl Reference Kohl2007: 70).

The Urukian expansion from 3600 bce onward led to a growing connection of the southern Mesopotamian networks with those of northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and the Caucasus (see Map i.2). Trading was active along the Euphrates, a river that played a crucial role in Urukian development. A Mesopotamian influence was felt in the plains of southwestern Iran (Susa II, 3500–3150) and in northern Mesopotamia (Brak, Hacınebi). From c. 3500, Uruk – and probably other rival Mesopotamian citiesFootnote 81 – created “colonies” (built by the state or by small groups independent of the state; this question remains debated): Qraya, Tiladir Tepe, Sheikh Hassan, and later Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda.Footnote 82 The clear purpose of these colonies was to control access to regions of Anatolia and Iran that were rich in metal ores; to utilize pasture resources (for wool); and to interconnect the southern Mesopotamians with established trade centers and networks in Syria, between Anatolia and the Levant, and on routes crossing Iran. The importance of “outposts” such as Habuba Kabira implies active involvement by the public sector (palace, temple) in the process of creation.Footnote 83 Urban planning and the building of its fortifications required a strong community, and therefore state-level organization. The “Urukians” also settled in centers located either at network nodes or near coveted resources. Sites such as Hacınebi (as early as the Middle Uruk period) and Hassek HüyükFootnote 84 thus hosted Mesopotamian enclaves. In the sites where Urukians were present, they usually brought their own administrative techniques (bullae, seals, tablets, weights), ceramics, bitumen, and building techniques. When Hacınebi hosted an Urukian enclave, two administrative systems – Anatolian and Urukian – seem to have coexisted. In an attempt to refute the possible formation of a world-system centered on Uruk and other Mesopotamian cities, Stein alleges – while providing no evidence for it – that exchanges between the Anatolian and Urukian communities were symmetrical; in fact, we do not know what was really exchanged; textiles and slaves, for example, left no trace in the archaeological deposits. In any case, it seems that the Urukian demand stimulated copper production in Anatolia. Stein recognizes that we have little information to go on for understanding the context surrounding the Anatolian elite during Urukian phase B2. He also puts forward the unlikely idea that there were few interactions between the Anatolian and Urukian communities during their two or three hundred years of coexistence (Reference Stein1999: 166)! Moreover, contrary to Stein’s assertion, a core’s power over a region did not necessarily diminish with distance, nor did exchanges become increasingly “symmetric” when the distance increased – I will come back to this point. Chains of exchanges were formed, along which inequalities could be transmitted and strengthened. While distance and the existence of groups positioned as intermediaries could lead to lower profits for the agents of the core, they did not reduce exploitation of the system’s geographic or social peripheries. The fact that the Urukians sought alliances with the local elites does not imply equality in the situation of the two communities within the world-system. Moreover, the Urukians were settled on the highest part of the site, a fact Stein did not take into account. Lastly, Hacınebi was not a “periphery” as Stein terms it, but a semi-periphery: the level of social complexity, development of crafts, and density of its regional population show this clearly. The elites of northern semi-peripheries benefited from exchanges with the Urukians within a process of coevolution, but beneficial exchanges are not equivalent to symmetrical relations (Rothman [Reference Rothman, Rothman and Fe2001b] commits the same error as Stein when he refutes Algaze’s model, arguing that “northern societies must have seen advantages to an exchange relation with Southerners”: these advantages recognized by the north did not imply the absence of dominance and exploitation by the southern Mesopotamians).

Other Anatolian sites, such as Tepecik, exhibit Mesopotamian influences without revealing an Urukian presence. This is also the case at Godin (level VI) (Iran) for the Middle Uruk period. The Euphrates River played a pivotal role because it offered access to the metal resources of the Ergani area, the Taurus forests, and the products of the Mediterranean region (the location of the colony of Habuba Kabira is enlightening in this respect).Footnote 85 In Syria, the site of El-Kowm, which shows influences from Sheik Hassan from the thirty-fourth century bce onward, forms the western boundary of the Urukian sphere. Algaze has defined the ensemble formed by the southern Mesopotamian core and the network of Urukian enclaves as an “informal empire” or a “world-system,” whose activity and survival depended primarily upon alliance networks with local chiefs.Footnote 86

Moreover, Mesopotamian merchants and artisans may have been present at more isolated sites, located along trade routes (thus Godin Tepe [VI.1],Footnote 87 Sialk [III], in Iran, close to copper resources of Anarak).Footnote 88 For this “Urukian expansion,” we should probably consider the existence of merchant communities operating within indigenous societies.Footnote 89 The regional configuration of established Urukian settlements shows dendritic forms that suggest the functioning of a monopolistic system (Algaze Reference Algaze and Rothman2001: 49) or at least some kind of cooperation.

In Iran, tablets impressed by cylinder seals and bearing numerical notations have been found at Susa, Chogha Mish (Khuzistan), Tal-i Ghazir (between Khuzistan and Fars), and Godin Tepe (in Luristan). According to Potts (Reference Potts1999: 60), the numerical tablets from Godin are similar to tablets from northern Mesopotamia (Tell Brak, Mari, Jabal Aruda), “whereas those from Susiana are most like examples from Uruk”; for Dahl et al. (Reference Dahl, Petrie, Potts and Petrie2013: 354), however, “the Godin Tepe tablets are all Uruk-style tablets.” “A single tablet (T295) has been classed as numero-ideographic, it bears a pictographic Uruk IV sign” (Matthews Reference Matthews and Petrie2013: 347). Sialk (IV 1) yielded numerical tablets, prior to the appearance of Proto-Elamite documents.Footnote 90 Proto-literate tablets have also been found in northeastern Iran, at Tepe Hissar. At Uruk, proto-cuneiform signs and numerical systems were present together on tablets, but at Susa, it was only at Level III that pictograms appeared, after Susa II and the numerical tablets (Potts Reference Potts1999: 63). Only “three of the thirteen numerical systems attested at Uruk [Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods] were introduced to Susa [Susa II]” (Potts Reference Potts1999: 65). But the Proto-Elamite includes a “decimal counting system that is not attested at Uruk (Dahl et al.)” (Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013b: 393). Potts emphasizes that although Mesopotamian scribes probably settled at Susa, it is difficult to view Susa as an Urukian colony. In fact, it is possible that a state centered on Susa maintained its autonomy, and influenced the Iranian plateau (see Petrie Reference Petrie and Petrie2013b: 399).

The Urukian expansion fostered new development in Anatolia and Syria, where local elites took advantage of the exchanges and adopted some southern Mesopotamian practices such as the use of cylinder seals.Footnote 91 They established themselves as intermediaries along the roads of coveted products and organized their own craft production. Arslantepe, where a vast public palace-like structure was built starting in 3500 bce, appears to have been a minor power center, controlling local or regional production. Many seals have been excavated, that were used in accounting operations. The site shows connections with southern Mesopotamians, but also with Syria and the Maykop culture.Footnote 92 As already pointed out, ideology – and ideational technologies – certainly played an important role in the southern Mesopotamian expansion; ideology clearly influenced the northern chiefdoms or proto-states and contributed to their configuration into semi-peripheries of the Urukian world-system.Footnote 93 The culture of Maykop, in the northwestern Caucasus, clearly reflects Mesopotamian influences, first from northern Mesopotamia,Footnote 94 with the borrowing of the slow wheel, and later from southern Mesopotamia, as revealed by the discovery of a cylinder seal and a toggle-pin with a triangular-shaped head known at Arslantepe during the Late Uruk period (Kohl Reference Kohl2007: 75; Kohl and Trifonov Reference Kohl, Trifonov, Renfrew and Bahn2014: 1578). Brought through Iran and the region of Nineveh, lapis lazuli has been unearthed at no fewer than three sites (Maykop, Novosvobodnaya, Staromysatov) (Primas Reference Primas2007: fig. 9). Carnelian and cotton from India have also been found, as well as turquoise from Tajikistan (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2015: 93). The extension of exchange networks can also be seen in the northeastern Caucasus, where the site of Velikent, which appeared around 3500 bce, yielded arsenical bronze from its earliest levels.Footnote 95 In the Urals, copper at the site of Kargaly was mined as early as the second half of the fourth millennium (Chernykh Reference Chernykh2002: 94), and the “royal” kurgans exhibit extraordinary wealth in metals, including gold and silver objects (Kohl and Trifonov Reference Kohl, Trifonov, Renfrew and Bahn2014: 1579). These interactions would lead to the emergence of new institutions in the Eurasian steppes (Kristiansen Reference Kristiansen, Hornborg and Crumley2007: 160). South of the Caucasus, in Transcaucasia, the Kura-Araxes formations expanded from 3500 bce onward.Footnote 96 Some tin-bronze ornaments have also been discovered in the tombs of Velikent; these bronzes would become more abundant during the first half of the third millennium in kurgans south of the Caucasus, and then further west, at Troy II and at Aegean sites and as far as the Adriatic (Velika Gruda). The tin may have come from Central Asia (Afghanistan, Samarkand, or regions further east?).

It would be inaccurate to view the seven hundred years of the Middle and Late Uruk periods as a continuum of growth in space and time: several phases of growth and decline are apparent. A first phase of expansion occurred around 3600/3500 bce, and another one a few centuries later (Habuba Kabira would come under this second phase). Rothman (Reference Rothman and Postgate2004: 57) discerns three phases of expansion, the first at the start of the Middle Uruk period, the second later during the same period, and the third during the Late Uruk.

Moreover, as already mentioned, authors such as Ur tend to emphasize continuity with preceding centuries rather than “revolution.” Ur notes the presence of tripartite houses that were already known during the ‘Ubaid period: so-called “palaces” or “temples” retained the same structure. Ur rejects the idea that urbanism results from extending trade and growing tribute demands; he does not believe in the formation of social classes going along with the creation of true bureaucracies. “Urban society in the Uruk period was a dynamic network of nested households,” writes Ur (Reference Ur2014: 15). Here, however, he does not discuss the implications of the development of writing and of the impressive division of labor revealed by later lists of professions. For him, “broad social change is more likely to stem from the creative transformation of an existing structuring principle – in this case, the household – than from the revolutionary replacement of an existing structure with a completely new one.” He notes that “the term for ‘palace,’ e2-gal, literally meant ‘great house’.” However, this may be just a metaphor; and the fact that a city or a temple could remain under the rule of a particular household should not lead us to preclude the idea of new types of political or religious elites. Ur himself notes that some large tripartite houses built on high terraces must indeed be temples; their construction implies a large labor investment. Surely these “households” were not just common households. It is true, however, that when we consider ancient societies, “categories such as ‘urban’ and ‘state’ must be able to subsume a great deal of variability” (Ur Reference Ur2014: 20), and the birth of the state does not imply the disappearance of kinship.

Most of the exchanges between southern Mesopotamians and northern populations are thought to have occurred within peaceful contexts. Military power must have played a role, however, especially when strong political entities emerged in the semi-peripheries of the Urukian area. During the Late Uruk period, settlements such as Habuba Kabira and Abu Salabikh were fortified: this appears to reflect growing conflicts.Footnote 97 At Hamoukar, a conquest by southern Mesopotamians has been suggested. “Urukians” also took over Brak – after a period of interactionFootnote 98 – and possibly Nineveh. Moreover, slaves may have been exchanged with the northern proto-states and then led to the cities of southern Mesopotamia.Footnote 99

The Urukian expansion extended toward Egypt, via northern Syria. The existence of an Anatolia–Levant sphere of interaction is shown in the participation of Hama and sites of the Amuq in “a Syro-Anatolian glyptic tradition distinct from Mesopotamia,” the diffusion of the technology of the “Cananean blades,” the use of the pottery wheel, the presence of silver items at Byblos, in the southern Levant and in Egypt, and the relative abundance of copper at Byblos, with silver and copper coming from Anatolia (Philip Reference Philip and Postgate2004: 218, 220). This sphere of interaction was already in place at the start of the fourth millennium.

In the Persian Gulf, in contrast to what can be observed in Upper Mesopotamia and Iran, the Urukian presence seems to have been limited, perhaps because the organizational level of Arab societies did not allow for an efficient utilization of resources. It is unlikely that the Mesopotamian influences observed in the Nile delta and in Upper Egypt resulted from the presence of Urukians who sailed around the Arab coasts.Footnote 100 Exchanges did occur, however, during the fourth millennium, between Mesopotamia, Iran, and the eastern Arab coast. A clay bulla has been found at Dharan (end fourth millennium); Mesopotamian-type jars with tubular spouts discovered at Umm an-Nussi in the Yabrin oasis and at Umm ar-Ramadh in the al-Hufūf oasis may date to this period.Footnote 101 Around 3400 bce, at Ra’s al-Hamra (Masqat), grey ceramic from southeast Iran was used to heat bitumen imported from Mesopotamia (Cleuziou and Tosi Reference Cleuziou, Tosi, Frifelt and Sorensen1989: 30). The name of Dilmun (which, during this period, refers to the Arabian coast in the region of Tarut-Dharan, and not yet to Bahrain) appears in a text from the Uruk IV phase: we hear of a “Dilmun tax-collector,” which means that Sumerians were involved in trade with Dilmun, and a text from Uruk III refers to a “Dilmun axe” (Potts Reference Potts1990: 86). Archaic texts from Uruk also mention copper from Dilmun, which may have originated in Oman. It could be that during the final years of the fourth millennium, barley and wheat were taken to Arabia. The term ŠIM, which seems to mean “aromatic essence, incense,” already appears in texts of the Uruk IV period. Archaic texts from Uruk mention “an aromatic product for the use of the priests”: aromatics certainly reached Dilmun at this time via a route linking Dhofar to Yabrin and al-Hasa (Zarins Reference Zarins and Avanzini1997, Reference Zarins, Cleuziou, Tosi and Zarins2002). Moreover, the discovery of bowls of Urukian (or Proto-Elamite) type in Baluchistan renewed speculation on the possible role played by contacts with Susa and Mesopotamia in the emergence of the Harappan culture (Benseval Reference Benseval, Parpolla and Koskikallio1994, Joffe Reference Joffe2000). Pottery of Urukian style unearthed at Tepe Yahya reflects southeastern Iranian links with Susa. The discovery of cotton fibers on fragments of plaster in a camp at Dhuweila (Jordan) (between 4450 and 3000 bce) reveals the importation of cotton fabrics, possibly from the Indus region.Footnote 102

Around 3200/3100 bce, the Urukian “colonies” were suddenly abandoned; we observe a reorganization of the exchange networks as well as social transformations – not yet well understood – in southern Mesopotamia. Various reasons have been advanced. The decline observed in some “colonies” before their abandonment may have had its origin in the core of the system itself. A salinization of the lands – a consequence of faulty irrigation – may have led to weaker agricultural productivity and, therefore, to an increase in conflicts between city-states as well as to internal social problems: one notes “the abandonment of many of the public structures at the very core of Uruk itself.”Footnote 103 Climate data for the end of the fourth millennium show a decline in oak woodland at Lakes Van and Zeribar, and low water volumes for the Tigris and the Euphrates, reflecting a drier climate.Footnote 104 An aridization of southern Mesopotamia may have begun in the middle of the fourth millennium.Footnote 105 In addition, one observes a weakening of the summer monsoon system of the Indian Ocean, especially around 3200 bce.Footnote 106 The pressure exerted by cities on their physical surroundings (deforestation …) and the human environment (tributes, corvées, urban migration) may also have been destabilizing factors. It is likely that the activity of the outposts depended in part on products such as textiles delivered from urban centers of the south. The profitability of these outposts could not be ensured within a climate of economic and political deterioration.

In addition, the destruction of the “palace” of Arslantepe by a fire c. 3000 bce leads us to suspect other destabilizing factors which were not solely linked to climate change, but were also the indirect consequences of the Uruk expansion itself.Footnote 107 Transcaucasian populations belonging to the Kura-Araxes formations entered the plain of Malatya; they had probably been displaced by the arrival of groups coming from the steppes and the northern Caucasus. These Transcaucasians occupied Arslantepe from 3000 to 2900 bce.Footnote 108 North of the Caucasus, the Maykop culture disappeared around the end of the fourth millennium (Kohl and Trifonov Reference Kohl, Trifonov, Renfrew and Bahn2014: 1581–1582). We observe a reduction in number and size of the settlements in Anatolia following the collapse of the Urukian colonies, as well as a regional fragmentation.Footnote 109 Pontic and Transcaucasian influences are also seen in northwestern Iran during the late fourth and early third millennium, for example at Yaniktepe. At Godin, from 3100 to 2900, the Urukian/Susian influence diminished while at the same time, Transcaucasian pottery came into use (this pottery would become the most commonly used during phase IV).Footnote 110 Godin shows evidence of a fire, as does Sialk III, which was destroyed c. 3000 bce. The Kura-Araxes populations also migrated to the southwest, entering the Amuq plain (Syria) then northern Palestine, around 2800–2700 bce (Kohl Reference Kohl2007). In northern Mesopotamia, the lower town at Brak was abandoned, trade networks faded away, and “the use of tokens and sealed bullae as administrative technology disappeared, and mass production of pottery, on a large scale in the mid- to late-fourth millennium (e.g. Oates and Oates Reference Oates and Oates1993: 181–182), all but disappeared at the end of the Uruk period” (Ur Reference Ur2010: 401).Footnote 111 The Urukian networks obviously could not survive in a politically hostile environment. Trade relations between Egypt and Mesopotamia practically stopped around 3100/3000. Upheavals in the north of the Urukian sphere of interaction affected not only the north–south relations, but also east–west routes. The abandonment of the northern colonies corresponds to a shift in Mesopotamian trade southwards toward the Persian Gulf, where copper in Oman began to be utilized in a significant way, within a more fragmented political and cultural context.Footnote 112

Mesopotamia. Tablet of accounts, probably account of bread distributed to four persons (J.-J. Glasssner, p.c.). The circles represent figures. Uruk, late fourth millennium, Louvre, A029560. © RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

(a–d) Egypt. Bone or ivory inscribed labels. Tomb U-j, Abydos, tomb of King “Scorpio,” c. 3200 bce. © German Archaeological Institute, Cairo

Illustration i The beginnings of writing

(a) Mesopotamia. Cylinder seal of Ishma-Ilum, Prince of Kisik, featuring a naked hero mastering two lions; made of lapis lazuli, a stone imported from Afghanistan; c. 2500 bce. H.: 3 cm, Musée du Louvre, AO 22299. © RMN-Grand Palais. Christian Larrieu

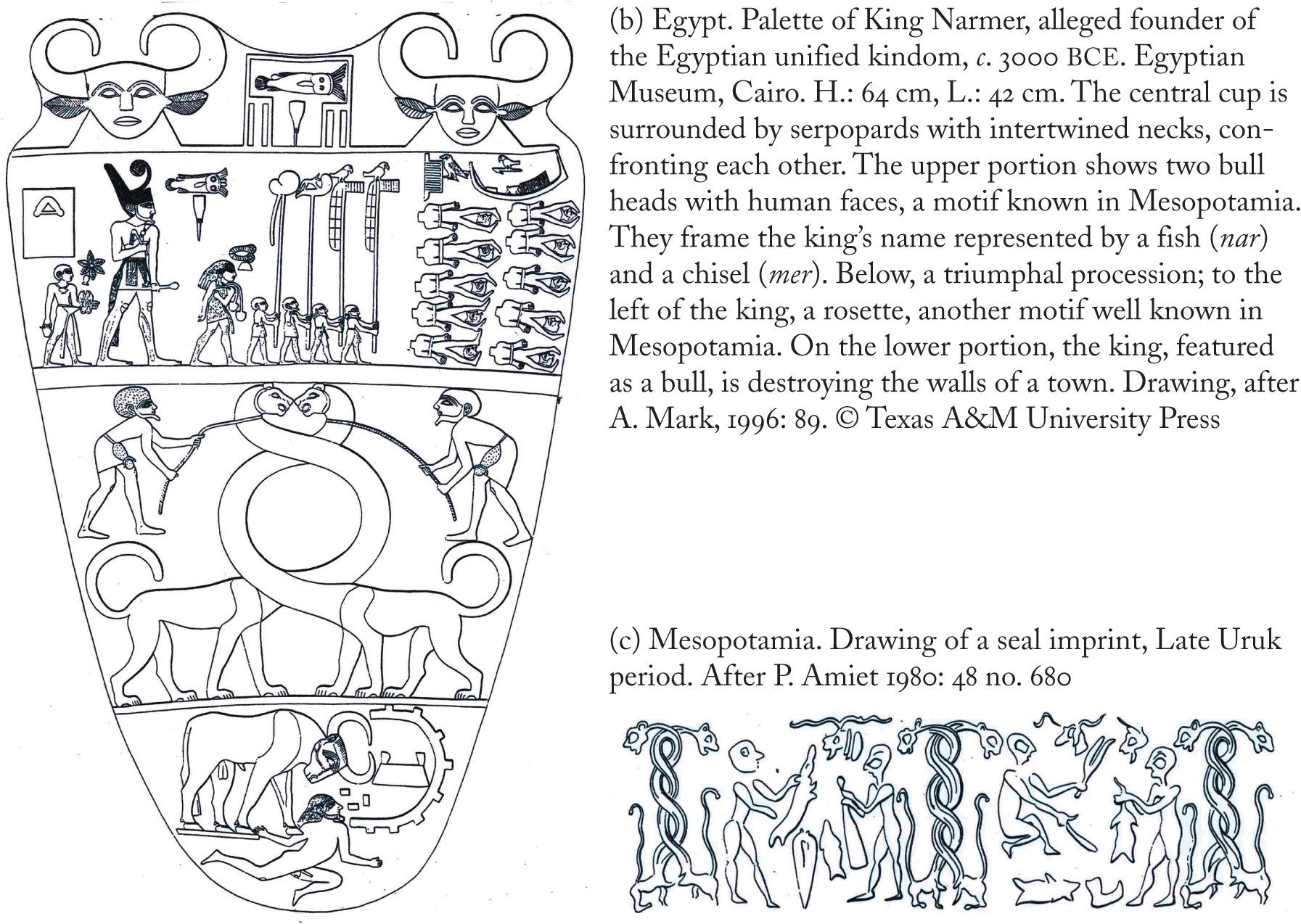

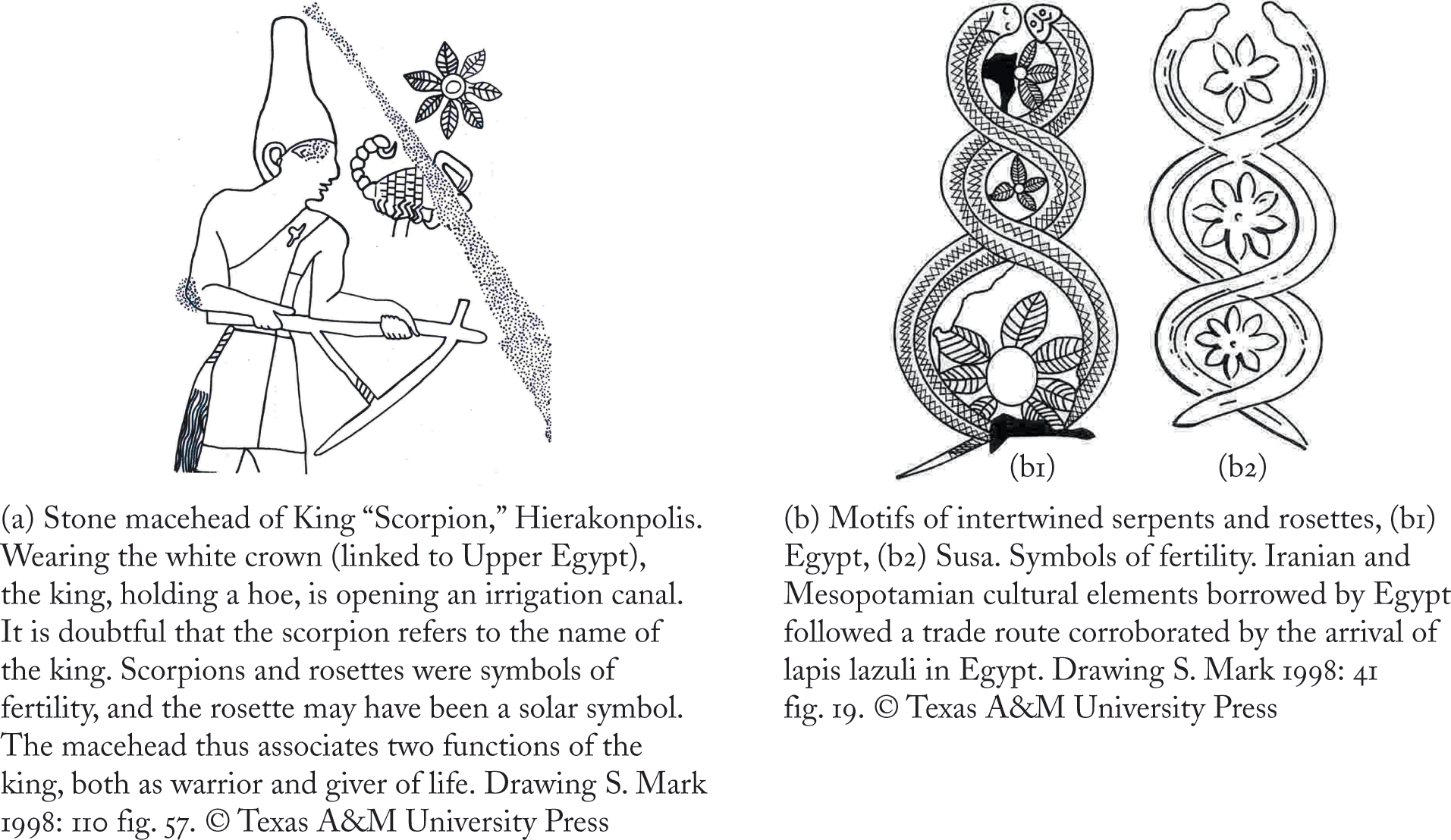

Illustration ii The influence of Mesopotamian themes and techniques in Predynastic Egypt: the “master of animals,” long-necked mythical animals, rosettes, and the use of the cylinder seal (1)

(a) Mesopotamia. Cylinder seal showing animals with intertwined necks. Uruk period, 3500-3100 bce. Louvre, MNB 1167. © RMN-Grand Palais. Cliché Hervé Lewandowski

Illustration iii The influence of Mesopotamian themes and techniques in Predynastic Egypt: the “master of animals,” long-necked mythical animals, rosettes, and the use of the cylinder seal (2)

(c) Egypt. Statuette of a naked woman in lapis lazuli (a stone imported from Afghanistan). Hierakonpolis, c. 2900 bce. H.: 8.9 cm, Ashmolean Museum, E1057. © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

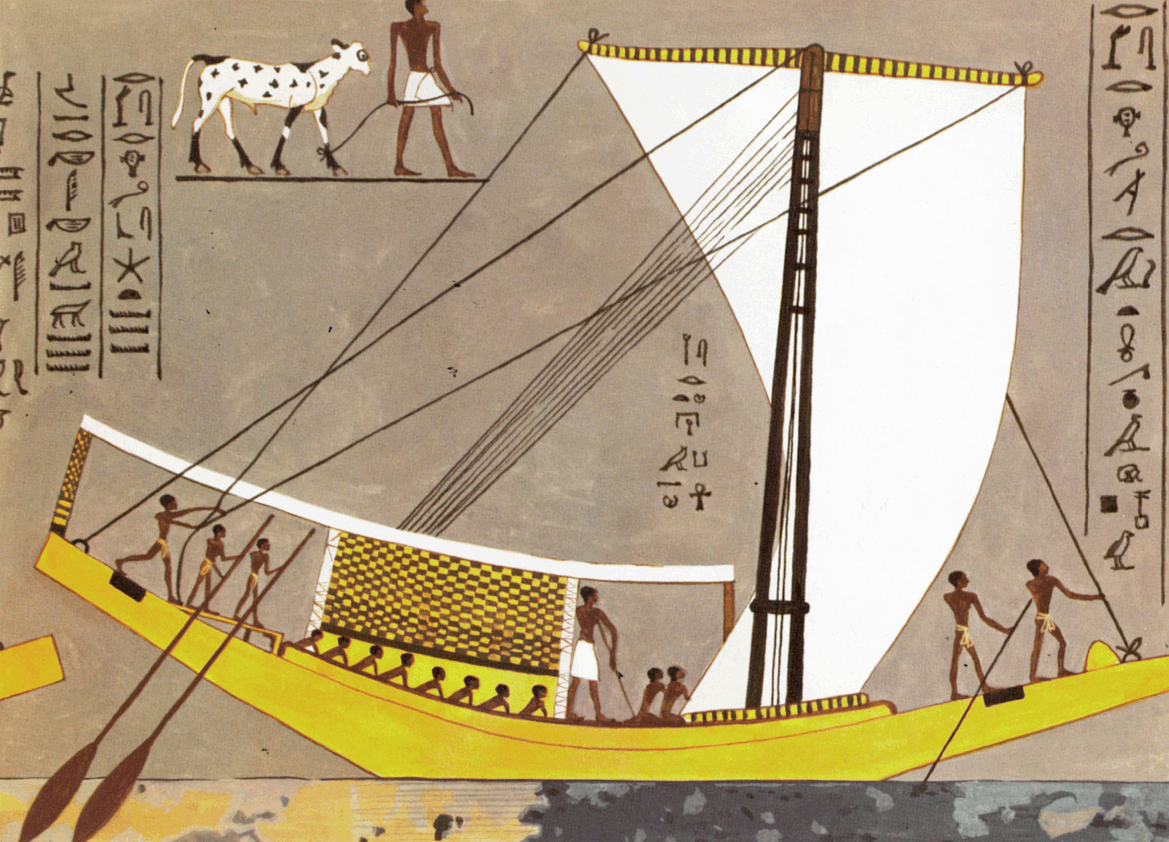

(d) Ship of the Fourth Dynasty, tomb of Kaem’onkh, Gizeh. After B. Landström 1970: 40 fig. 104

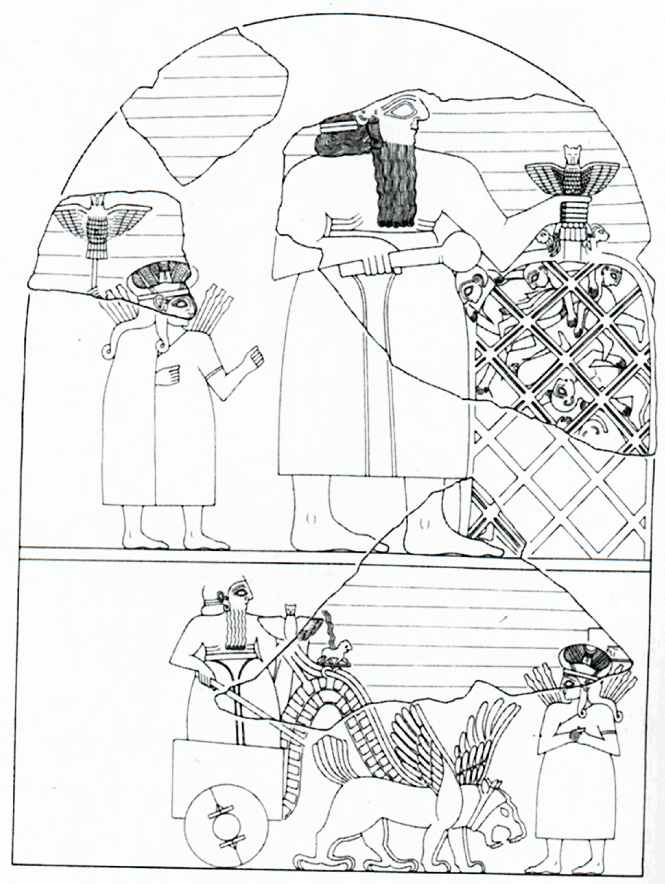

Illustration iv Statebuilding and long-distance exchanges

(a) Mesopotamia. “Standard” of Ur, “Royal” tomb PG 779, panel of war. Shell, lapis lazuli, red limestone, bitumen. Top register: the king, of higher stature, stands in the middle. Middle register: foot soldiers; on the right: naked prisoners. Lower register: chariots drawn by donkey-onager hybrids, c. 2400 bce. H.: 20.3 cm, L.: 47 cm. British Museum, London, BM 121201. © The Trustees of the British Museum

(b) Lion-headed eagle pendant: gold, lapis lazuli, bitumen, and copper. Palace of Mari, c. 2400 bce. H.: 12.8 cm; L.: 11.9 cm. This god appears on a seal of the Late Uruk period. National Museum, Damascus. © Philippe Maillard/AKG Images

(c) “Stela of the vultures,” erected at Tello c. 2450 bce by King Eannatum (Lagash) after his victory over Umma. The god Ningirsu holds the lion-headed eagle, which strangles two lions above a large basket in which prisoners are stacked. The lower register shows the chariot of the god Ningirsu drawn by a griffin. A. Benoit 2003: 226, drawing by E. Simpson, after J. Winter 1985: 13 fig. 3

Illustration v Images of power

(a) String of carnelian and lapis lazuli beads, with quadruple-spiral gold pendant. Ur, c. 2400 bce. This quadruple-spiral motif has been found from Troy to the Persian Gulf and Turkmenistan, as well as other decorative themes such as flat-disk gold beads with raised mid-ribs (see Aruz 2003: 240, 241). The carnelian stone came from Iran or the Indus, and the lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. © University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia B17650

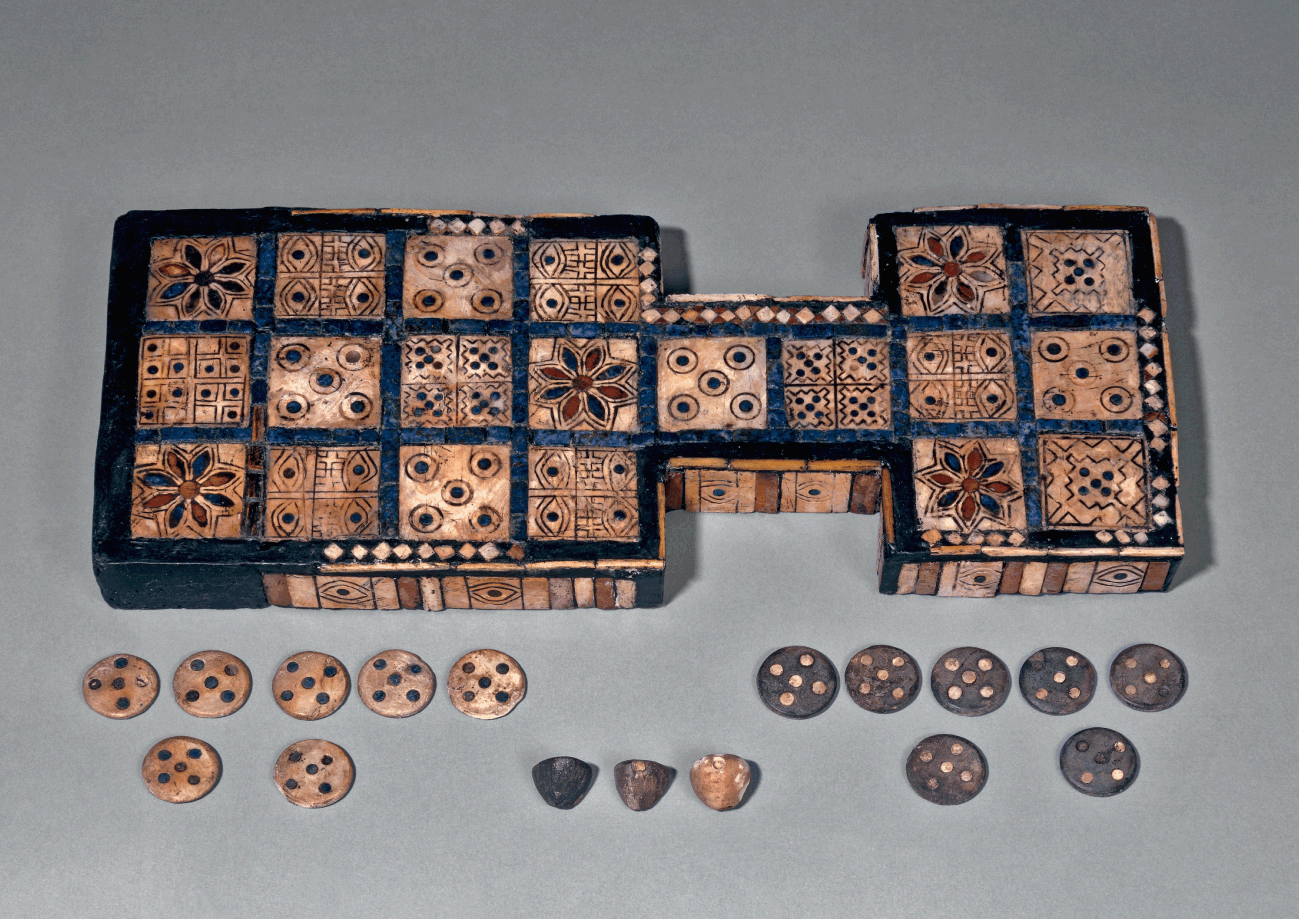

(b) Game board of twenty squares, made of shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli. From the Royal Cemetery at Ur. PG 513. L.: 30.1 cm, W.: 11 cm. British Museum, London, BM 120834. Known since 3000 bce, this game spread to Egypt, the Aegean world, and India over the centuries. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Illustration vi Long-distance exchanges in the Mesopotamia–Indus world-system

Illustration vii Intercultural theme of horned animals feeding from the tree of life

(c) Cylinder seal of a scribe of King Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad, c. 2183-2159 bce, made of serpentine. Theme of heroes watering horned animals – here buffaloes imported from the Indus valley – with overflowing vases, a motif known in other regions, such as Jiroft. Inscription in Old Akkadian. H.: 3.9 cm, Diam.: 2.6 cm. Musée du Louvre, 10 22303. © RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

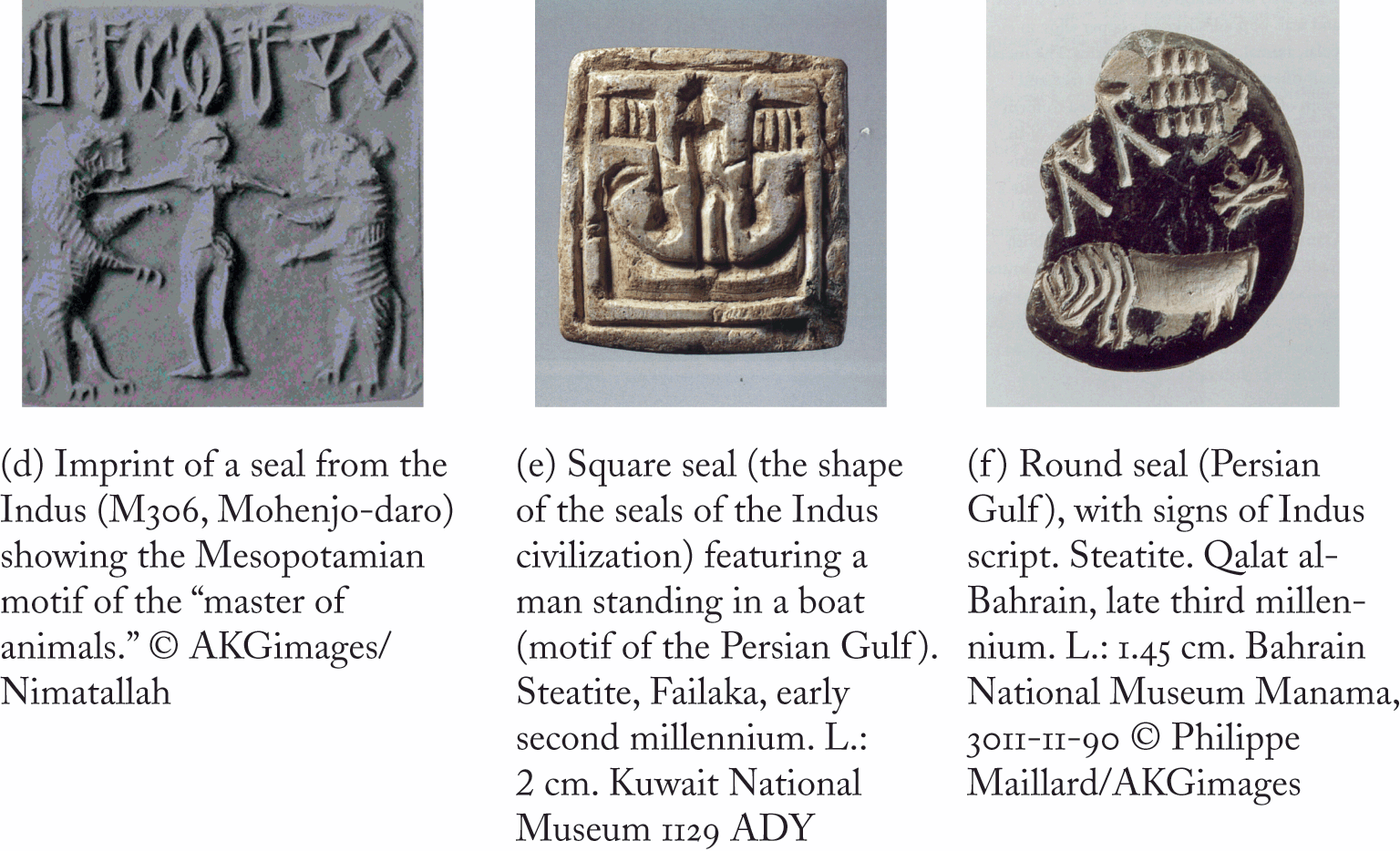

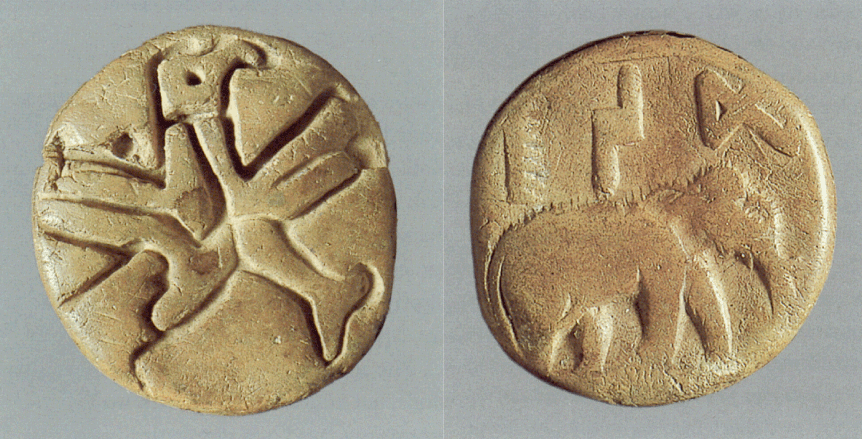

Illustration viii Intercultural style and hybrid seals

(c) “Priest,” wearing a cloak with trefoil motifs. Limestone. Mohenjo-daro, twentieth century bce. H.: 17.8 cm. National Museum of Pakistan. © DEA / A. Dagli Orti/AKG/De Ago The trefoil motif is also known in Central Asia. A. Parpola (1985) has compared the cloak to the tarpya garment of the Vedic ritual (this comparison remains contested).

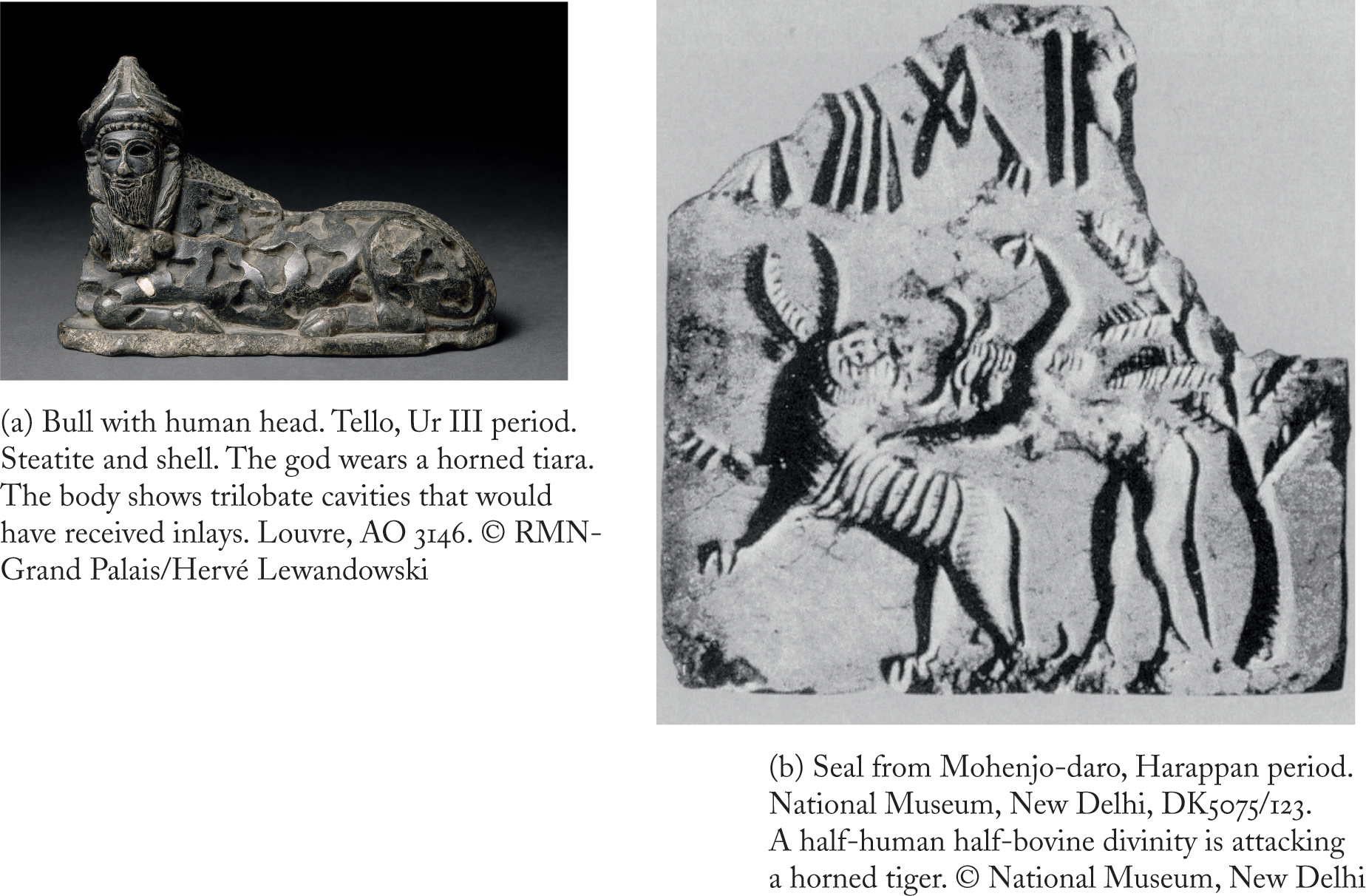

Illustration ix Mutual influences between Mesopotamia and the Indus

(c) Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty (1550-1295 bce). Anthropomorphic mirrors appeared in Egypt and in Asia at the beginning of the second millennium. Louvre, E 3745. H.: 31 cm. © RMN-Grand Palais, Les frères Chuzeville

(d) Bactria–Margiana. Copper mirror with anthropomorphic handle. Early second millennium bce. Louvre, AO 28539. © RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

Illustration x Objects from Bactria–Margiana showing foreign borrowings

(a) Ceremonial axe. The blade protrudes from the mouth of a horned dragon (this motif would later be found in eastern Asia). Luristan, early second millennium bce. Well known in the Bactria–Margiana culture, these ceremonial axes have been found in Iran and Mesopotamia. Louvre, 22933. L.: 6.7 cm. © RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

(b) Tell Abraq, United Arab Emirates, c. 2000 bce. Comb decorated with an incised tulip motif imported from Bactria or Margiana. Sharjah Archaeological Museum, TA 1649. © Sharjah Archaeological Museum

(c) Indus, Mohenjo-daro. Bulla or clay amulet with imprints of a Harappan seal on one side, and of a seal of the Bactria–Margiana type on the other (eagle motif). Department of Archaeology and Museums, Pakistan, NMP 50402

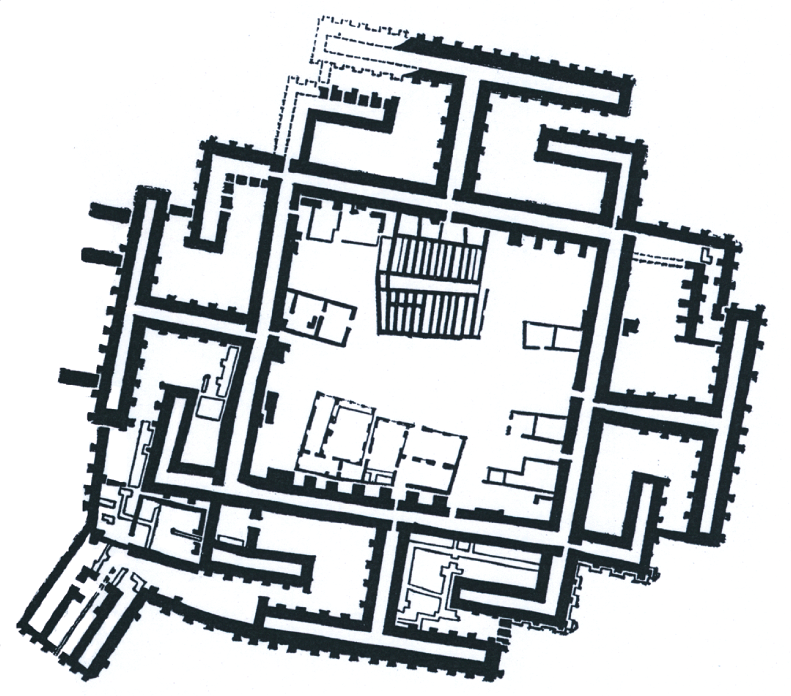

(d) Plan of the “palace” of Dashly 3 (Bactria), c. 2000 bce. After V. Sarianidi 1986: 53

(e) Compartmented seals found in Bactria–Margiana, as well as in Iran and in the Indus valley. After A. Parpola 2002

Parpola (2002) has suggested a relationship between the plans of fortresses such as Dashly, cruciate seals, and mandalas and the Chinese mirrors termed “TLV” from the Han period.

Illustration xi Cultural interactions and expansion of the Bactria–Margiana Complex (late third – early second millennium)

(a) Reverse of the envelope of a debt obligation. Kanesh, Anatolia. Debt of one silver mina owed by Shakdunua, son of Sharpa (an Anatolian), to Ashur-taklaku (an Assyrian). The interest amounts to 15 shekels of silver, 5 bags of wheat, and 5 bags of barley. The contract is dated for week, month (II) and year (c. 1863 bce). The envelope bears the imprint of the cylinder seals of the debtor and of three witnesses. It features scenes mixing Mesopotamian, Anatolian, and Syrian styles. Text Kt 93/k 550, Museum of the Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

Translation and photograph C. Michel

(b) Babylon. Stela, “code” of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 bce) (texts of law). Diorite. H.: 2.25 m. L.: 55 cm. Found at Susa, where it had been brought by the Elamite king Shutruk-Nahhunte (c. 1185-1160). The upper register shows Hammurabi before the solar god Shamash. The text, written in Akkadian, is meant to be read from top to bottom, in columns. It was written “to demonstrate justice within the land …, to stop the mighty exploiting the poor” (Benoit 2002: 289). A “code of laws” had been promulgated by King Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1838-1828). © RMN-Grand Palais, Christian Larrieu

Illustration xii Possible emergence of the individual during the Middle Bronze Age

(c) Silver cup, in the Töd “treasure.” This treasure includes objects of various origins, in silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and other stones. The silver items bear witness to Aegean and Cretan connections. Silver was obtained through the Mediterranean trade. Diam.: 10.5 cm. H.: 7 cm, Louvre E 15153. © RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

(d) Byblos, Royal Necropolis, Tomb III, gold pectoral. Decoration influenced by Egypt, featuring the falcon Horus. Eighteenth century bce. H.: 12 cm, W.: 20.5 cm. Louvre, AO 9093. The pectoral reveals Egyptian expansion as well as privileged connections between Egypt and Byblos. © RMN-Grand Palais, Hervé Lewandowski

Illustration xiii Interactions in the world-system of the Middle Bronze Age