Introduction

The international community promotes three durable solutions to refugee situations: integration of refugees into host countries, resettlement to third countries, and voluntary repatriation to countries of origin. While all three may be viable under certain circumstances, voluntary repatriation has long been promoted by the office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as the preferred solution (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Hammerstad Reference Hammerstad2000). Accordingly, voluntary repatriation programs have been attempted in the wake of post-Cold War conflicts in Rwanda, Bosnia, Croatia, and Sudan. However, there are negative consequences to promoting repatriation including increasing levels of violations of non-refoulement Footnote 1 and growing numbers of refugees returning home before conditions are safe for them to do so (McKernan Reference McKernan2019; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2019).

Those debating repatriation focus on the obligations and actions of host states and seemingly assume refugees hold uniform or unimportant opinions regarding if, and when, to return to their countries of origin. We contend the preferences and abilities of refugees should not be overlooked. We focus attention on understanding conditions under which refugees would prefer to return to their countries of origin. In comparison to the voluminous literature on the causes of forced displacement, little research explores the conditions under which refugees repatriate. To contribute evidence on refugee preferences for return, we develop a theoretical framework, adapting literature from psychology, in which we argue refugees vary in terms of how anchored they feel to either their country of origin or their current host country. We claim this variation depends, in part, upon the nature of their lived experiences, both in their country of origin prior to displacement and subsequently in the host country.

We begin by exploring two features of refugees’ predisplacement exposure to violence. First, we note that individuals more deeply anchored to their origin locations were more likely to stay at those locations for a longer duration before being displaced and, thus, were more likely to be exposed to violence. Second, their exposure to violence imbued them with an appreciation of their tolerance to unstable conditions. Through this exposure, individuals develop “expertise” in assessing risks associated with violence. That is, they develop efficacy in surviving insecurity. By contrast, refugees not directly exposed to violence before fleeing are unsure of the level of threat associated with returning and unwilling to accept the risk of doing so. Both the underlying anchoring and the newly developed understanding of risk make refugees who stayed at home longer and were exposed to violence more likely to desire a return to their countries of origin.

What anchors refugees to locations does not end when they flee their homes. We contend an individual’s desire as to whether or not to return home will also be affected by the extent to which they have developed ties and dependencies in their new host state. Individuals who have developed social anchors in the host state should, naturally, be less likely to desire a return to their country of origin.

We test these theoretical arguments using an original survey, carried out in Summer 2018 among nearly 2,000 Syrian refugees hosted in Lebanon. We use the survey to identify the influence of conflict exposure and anchoring (or attachment) to both Syria and Lebanon on refugees’ preferences for the future. We employ both observational and experimental elements from the survey for this purpose. We find those who have been exposed to violence prior to their departure and left when most of their hometown had fled are most likely to prefer returning to Syria. Refugees who discussed the matter of fleeing as well as those who find it easy to cross the Lebanese/Syrian border are more likely to prefer remaining in Lebanon.

This paper contributes to scholarship on refugee movement in two important ways. First, most research on refugee repatriation takes the perspective of nation-states, exploring their obligations to and violations of international refugee law. We examine the agency and preferences of refugees themselves. Second, we develop a novel theory of refugee repatriation that accounts for both individuals’ past exposure to violence and their sense of attachment to both their country of origin and their current host country.

Repatriation as the Preferred Solution

As the number of refugees globally has increased, the traditional solutions promoted by the UNHCR have become collectively insufficient in alleviating refugee hardship. In 2016, “only 2.5% of refugees (552,000) were able to return to their home countries … and even fewer, 0.8% (or 189,300), were resettled through formal settlement programs. An even smaller percent age (0.001%, or 23,000) were naturalized as citizens” in host countries (Ferris Reference Ferris2018).

While collectively insufficient, these numbers suggest repatriation—or return to the country of origin—is the most frequently observed “solution.” These rates speak to a flaw in the durable solutions model: public prioritization of repatriation gives current and potential host states an excuse to discount and, thus, shirk their contributions to integration and resettlement alternatives. Since repatriation is considered the preferred solution, local integration has morphed into underresourced, temporary hosting, while resettlement quota numbers have receded dramatically (Salehyan Reference Salehyan2018). More than eight of every ten refugees are hosted by states neighboring their countries of origin. These are typically developing countries requiring more assistance than is available to meet the demands associated with hosting refugees (Bradley Reference Bradley2013). There are several domestic challenges associated with refugee hosting and integration. Refugees are often challenged by inadequate language skills and culture shocks (Akar and Erdoğdu Reference Akar and Erdoğdu2019). At the same time, citizen populations in host countries often struggle to accept refugee populations, especially given the large numbers in protracted scenarios (Ghosn, Braithwaite, and Chu Reference Ghosn, Braithwaite and Chu2019).

Given that developing host states are stretched thin and developed states lack political will to open their doors, it makes sense that repatriation is identified as the preferred solution for refugee crises (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Hammerstad Reference Hammerstad2000). International law dictates four preconditions for the initiation of large scale repatriation programs: (1) there is a fundamental change of circumstances in the country of origin that would reduce the risk associated with return; (2) the decision to return is voluntary in nature; (3) a tripartite agreement is signed between the origin state, host country, and the UNHCR; and (4) the return process happens in safety and dignity. In practice, all conditions are rarely met, especially when host governments pressure both the UNHCR and refugees themselves to return. The lack of accountability toward upholding these conditions leads to commentary questioning whether observed returns of refugees are truly voluntary (Black and Gent Reference Black and Gent2006).

Repatriation as a solution is not without its detractors. Critics argue such a strong focus upon repatriation encourages overburdened host states to violate norms of non-refoulement (Barnett Reference Barnett2001). Repatriation is considered to be a way for host states to release themselves from their duty of hosting refugees, thus eroding the human right to asylum (Adelman and Barkan Reference Adelman and Barkan2011). In response to the growing economic and social burden they face, governments often frame hosting as a temporary solution, with many of them pushing for refugees to leave as soon as possible (Orchard Reference Orchard2014). This trend has resulted in growing numbers of refugees returning to states lacking the capacity to absorb them. This includes hundreds of thousands of Syrians who have been encouraged to voluntarily sign repatriation paperwork and depart Turkey even while the civil war at home rages on (McKernan Reference McKernan2019). Similarly, more than 80,000 Somali refugees have returned home from Kenya since a repatriation program was agreed between UNHCR, Kenya, and Somalia in 2013, with almost 3,000 of these individuals having again since been displaced from Somalia (Loughran and Aden Reference Loughran and Aden2019).

While repatriation as a program is clearly problematic, refugees in many situations do appear to hold strong preferences to return home, even while violence continues in their country of origin (Chu Reference Chu2019; Stein and Cuny Reference Stein and Cuny1994). How might we explain this incongruity between public commentary and refugee preferences? Academic scholarship often views decisions regarding return through the same “push and pull” framework used to explain their initial displacement (Davenport, Moore, and Poe Reference Davenport, Moore and Poe2003; Moore and Shellman Reference Moore and Shellman2007; Schmeidl Reference Schmeidl1997). Return is deemed most likely when circumstances at home are better than conditions in exile (Koser Reference Koser1997).

Under this framework, refugees returning during conflict may at first blush appear somewhat puzzling. However, refugee return under continued duress in the country of origin may not be so surprising given the dwindling opportunities for resettlement in third countries and the worsening conditions on the ground in temporary host countries. For example, Syrian refugees who have returned while their civil war is ongoing have commonly cited limited opportunities in the host state and a shift in aid resources to areas in Syria as reasons for their return (Al-Khateeb and Toumeh Reference Al-Khateeb and Toumeh2017). In addition, evidence suggests host state restrictions on movement, economic opportunities, and access to welfare provisions such as medical care to refugees, also make it difficult to sustain livelihoods abroad, in turn increasing the likelihood of return (Parkinson and Behrouzan Reference Parkinson and Behrouzan2015). In some instances, ultimatums by host states may motivate return migration. For example, Sudanese refugees in Israel must choose between repatriation with a stipend or the threat of detention (Gerver Reference Gerver2014).

Existing scholarship on refugee return has not fully addressed several issues. Many studies homogenize refugees’ experiences and the effect these have on their preferences.Footnote 2 Such studies assume refugees are displaced by violence and thus deterred from returning to their home countries until the conflict has ended. However, there is variation in refugees’ exposure to violence, the factors motivating their decisions to flee, and the preferences they hold regarding returning home. Accordingly, many struggle to explain why a majority of surveyed Syrian refugees want to return home (Alsharabati and Nammour Reference Alsharabati and Nammour2017; Berlin Social Science Center Reference Center2015). Even these survey-based studies neglect to address questions regarding the timing of potential repatriation. Thus, as refugees are observed returning while violence continues in their country of origin, a more comprehensive understanding of why this is happening is required.

Understanding Refugees’ Movement Preferences

Little research explores conditions under which refugees are likely to repatriate, and even less examines how refugees’ preferences affect this process or how these compare with preferences to remain in the host state. In this section, we derive a set of testable hypotheses from a logic based upon notions of exposure to violence and attachment to place.

Adapting Kuhlman’s (Reference Kuhlman1990) framework of refugee integration in host countries, we suggest refugee decision making is affected by four categories of factors, as summarized in Table 1. While we acknowledge the factors across these different categories are interrelated, for the sake of simplicity we consider each category separately.

Table 1. Framework for Refugee Decision Making about Future Movements

Several demographic characteristics of the refugee’s preflight life likely affected their initial decision to flee and could influence whether they later wish to return home. Women and children are often early movers in displacement and, as a consequence, are a high proportion of the global refugee population—76% of Syrian refugees are women and/or children.Footnote 3 Wealthier individuals have more resources to flee early (Schon Reference Schon2019) and can afford to stay longer in exile in a host country. Individuals maintaining gainful employment in their hometowns may be more reluctant to flee than unemployed individuals who might be expected to depart sooner to seek out opportunities elsewhere (Adhikari Reference Adhikari2012). Finally, individuals with social ties to kin abroad may be more likely to travel to join them once conflict breaks out. These logics also suggest women and children, wealthy individuals, those without job prospects at home, and those with stronger ties to displaced individuals are less likely to want to return home.

Flight factors refer to changing conditions and contexts influencing an individual’s decision to flee or stay in their country of origin. Such decisions are driven in the aggregate by root causes of flight. The outbreak of war destroys infrastructure and inhibits economic opportunities, making an individual feel as if they have no choice but to leave (Adhikari Reference Adhikari2012; Moore and Shellman Reference Moore and Shellman2006; Steele Reference Steele2009). Individual decisions are also affected by interpersonal relationships and whether or not members of their familial and social networks have chosen to flee or stay. Decisions regarding whether to return likely involve a reassessment of these flight factors and perceptions of safety or harm associated with returning to origin locations.

We also believe host-related factors or aspects of the refugee’s situation in the host country influence decisions about future journeys. Such conditions likely include the availability of economic opportunities such as housing, employment, and access to social services provided by the state or nongovernmental organizations. Moreover, refugees exposed to verbal or physical assault by government agents or native populations likely feel less safe in the host country and are more likely to consider returning home.

Decisions are also affected by the portfolio of policies across multiple domains that support refugee populations or define their rights. In the host country, this includes laws affecting the ability to work, freedom of movement, and any rights to pursue naturalization. In the home country, policies include rules around forced conscription and whether the incumbent government would grant minority and opposition groups amnesty upon return. Finally, international policies might influence the ability of relief organizations to provide aid, the openness of transit routes, and the availability of resettlement opportunities.

This pretheoretical framework presents factors influencing refugee decisions about the future. However, refugees may be swayed by any or all factors, making it difficult to tease out which will influence individual refugees. Therefore, we develop a theoretical argument to prioritize factors.

Refugees and the Anchoring Effects of Attachment to Place

In developing a theoretical account for variation in refugee preferences regarding returning to their countries of origin, we apply the concept of anchoring. We suggest individuals are inclined to return home if they feel attachment to their country of origin and disinclined if not or if they enjoy attachments to their new host country.

We assume individual decision making is subject to bounded rationality via limits on capacity (Simon Reference Simon1972) and cognitive heuristics serve to reduce the complexity of assessments and calculations, enabling individuals to make difficult decisions more efficiently (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974) but also more strategically (Johnson Reference Johnson2020). Refugee decision making is surely subject to these efficiencies and strategic adaptations. We suggest two ways this theoretical approach is valuable for understanding refugee decision making. First, displaced individuals are challenged by limited information, uncertain levels of risk, and constraints on their ability to act independently in the future. As such, anchoring effects are critical to refugees’ decision-making processes,Footnote 4 informing which factors have the greatest bearing upon their preferred course of action.

Second, anchor biases affect judgements of self-efficacy and predictions of future performance. Existing explanations of refugee decision making speak to the shaping role of local context, yet they often erroneously homogenize refugee experiences such as exposure to violence and decisions to flee. Our anchor-based logic suggests individuals are exposed to different degrees of anchoring depending upon variation in these kinds of lived experiences. This anchoring bias refers to a process in which an individual’s initial decision (e.g., whether to flee) is anchored to a specific starting point. It is assumed individuals’ decisions will be biased toward this starting point when making subsequent choices, especially when faced with complexity and uncertainty (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974). However, as additional information becomes available, individuals will adjust their anchor and attachment to their anchor accordingly (Slovic Reference Slovic1972).

Broader research on decision making demonstrates individual judgements of self-efficacy have a strong bearing on adjustments to subsequent decision making and behavior. Cervone and Peake (Reference Cervone and Peake1986) demonstrate this in a generic setting, presenting study participants with random initial values of high or low levels of performance and then asking them to judge their own capabilities for the problem-solving task before them. High-anchor participants regarded themselves with higher levels of self-efficacy than did low-anchor participants. These judgments corresponded to subsequent task performance, with participants who judged themselves at higher levels of self-efficacy demonstrating greater task persistence. Switzer and Sniezek (Reference Switzer and Sniezek1991) subsequently examined the anchoring effect on predictions of future performance. While they were unable to draw any conclusive findings on the effect of the anchors on actual performance, they did find a notable relationship between anchors and individual self-judgment on likely future effort and performance.

What does this tell us about refugee decision making specifically? We argue an important first effect of anchoring is an individual’s exposure to violence.Footnote 5 Individuals are forced to flee from their homes as conflict closes in upon them, when they are stripped of civil liberties and rights, and when they are targeted by repressive government actions (Davenport, Moore, and Poe Reference Davenport, Moore and Poe2003; Moore and Shellman Reference Moore and Shellman2007; Neumayer Reference Neumayer2004; Schmeidl Reference Schmeidl1997). An individual’s decision to flee is informed by their perception of risk. Individuals from areas of conflict or disaster alter their risk preferences based on prior exposure to similar events (Eckel, El-Gamal, and Wilson Reference Eckel, El-Gamal and Wilson2009; Voors et al. Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and Van Soest2012). For example, victims of violence display strong preferences for high degrees of certainty regarding future decisions (Callen et al. Reference Callen, Isaqzadeh, Long and Sprenger2014), and victims of natural disasters subsequently display higher risk aversion in anticipation of future events (Cameron and Shah Reference Cameron and Shah2015). Exposure to violence can also result in heightened anxiety, depression, perceived insecurity, vulnerability, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A prominent feature of PTSD is an avoidance of stimuli associated with a traumatic event (Fleurkens, Rinck, and Van Minnen Reference Fleurkens, Rinck and Van Minnen2014).

These logics suggest refugees exposed to violence prior to fleeing their country of origin are less likely to desire to return while conflict is ongoing. Prior exposure to violence provides useful heuristics for refugees who prefer avoiding reexposure and likely prefer to return when conflict ends, if at all. Thus, refugees who have been exposed to violence likely feel anchored to their new host state and wish to avoid future risk of trauma. This suggests a conventional understanding of the effects of violence on decision making:

H1: Refugees exposed to violence before they were displaced are less likely to want to return to their country of origin.

Anchoring is also central to our understanding of individual attachments to meaningful locations. Place attachment can augment the anchoring heuristic by serving as a reference point for future decision making.Footnote 6 Such attachments enhance self-esteem and self-efficacy and can provide a bridge for one’s identity between prior experiences and future actions (Scannell and Gifford Reference Scannell and Gifford2010). So, when do people attach or detach from a particular place? Simply stated, place attachments are formed from judgements of satisfaction, expectations of stability, and feelings of positive affect (Shumaker and Taylor Reference Shumaker and Taylor1983). When an individual’s aggregate assessment of a location is positive, they are attached and unlikely to detach. When their assessment is negative, they may become detached. Crucial to understanding (in)voluntary relocation, is the idea that an individual’s place attachment is neither monolithic nor permanent. Some individuals may have attachments to multiple places simultaneously (Gustafson Reference Gustafson2009), and the intensity of attachments between locations likely varies depending on updated cost-benefit analyses (Giuliani Reference Giuliani, Bonnes, Lee and Bonaiuto2003).

In migrant decision making, place attachments may constrain the decision to leave home, prompt a decision to leave when losses are intolerable, influence choice of potential destinations, and affect migrants’ postmigration experiences (Dandy et al. Reference Dandy, Horwitz, Campbell, Drake and Leviston2019). Individuals with stronger place attachments are less willing to leave those places. For example, residents exposed to high flood risk have been shown to be less willing to evacuate or relocate if they demonstrated high place attachment (De Dominicis et al. Reference De Dominicis, Fornara, Cancellieri, Twigger-Ross and Bonaiuto2015). This is shown with Javanese communities remaining in or returning to high risk disaster areas (Lavigne et al. Reference Lavigne, De Coster, Juvin, François, Gaillard, Texier and Morin2008), Norwegian residents’ unwillingness to relocate in the case of an oil spill (Kaltenborn Reference Kaltenborn1998), and Australian residents having weaker intentions to leave in the face of a brushfire outbreak (Paton, Burgelt, and Prior Reference Paton, Burgelt and Prior2008). Place attachment might also motivate decisions to return following displacement, even in the face of danger. For instance, rural residents displaced by the Bhakra Nangal Dam Project in the Himalayas continued to search for ways to return to their habitats despite knowing these habitats were at high risk of future flooding (Pirta, Chandel, and Pirta Reference Pirta, Chandel and Pirta2014).

Various case studies suggest that exposure to adversity heightens individuals’ perception of future risks in conflict settings (Callen et al. Reference Callen, Isaqzadeh, Long and Sprenger2014; Voors et al. Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and Van Soest2012). Exposure can also prompt them to develop adaptive skills to identify threats, find ways to manage them (Brück, d’Errico, and Pietrelli Reference Brück, d’Errico and Pietrelli2018; Hernández-Carretero and Carling Reference Hernández-Carretero and Carling2012), and increase their perceived competence to tackle similar situations in the future. Several studies even find individuals become more risk acceptant (Voors et al. Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and Van Soest2012) or less risk averse (Bocquého et al. Reference Bocquého, Deschamps, Helstroffer, Jacob and Joxhe2018) after being exposed to violence. In the context of refugee decision making, this suggests that refugees exposed to violence prior to their displacement may be more likely to want to return to the locus of violence than are individuals without such prior exposure.

To explain, we assume individuals manage risk and uncertainty associated with new and potential future experiences by relying, in part, on prior experience (Zinn Reference Zinn2008). The underlying logic behind these strategies of risk management “is not one of cause and effect but one of analogy, a situation or event is like a previously experienced situation and therefore the decisions, action, and feelings from the previous situation are pertinent to the current situation” (Zinn Reference Zinn2008, 446). When exposed to violence, individuals develop several skills that enable them to identify threats and minimize risks. For example, Kirschenbaum’s (Reference Kirschenbaum2006, 22) study of terrorism and risk perceptions finds that “one important reason for the marginal impact of terror in Israel has been that individuals, families and larger social groups have adapted their preparedness behaviors so as to minimize its impact.” Similarly, when deciding to return to conflict, individuals can draw on their past experiences to assess and manage risks en route or at home.

Anchoring to place can help explain why this might be the case. Individuals attached to their homes may wait until the last minute to make the decision to migrate elsewhere. During that period of waiting, they develop tools to assess the risks they face. For example, individuals exposed to military shelling learn to gauge the distance of shells from the various sounds they make. Recognizing these sounds can help them evaluate when to take cover. If this simple strategy matches reality, individuals will be able to make quick, adaptive decisions to protect themselves against potential harm. This explanation does not homogenize exposure to violence. Rather, each form of violence may be associated with the development of unique adaptive strategies that protect them during similar future events. Furthermore, individuals need not be the direct victims of violence to develop expertise; they may also learn through “vicarious reinforcement”—by witnessing the actions of others and their consequences (Bandura Reference Bandura1971).

By adapting to and overcoming obstacles, individuals will enjoy higher self-efficacy and perception of control over adverse events (Bandura Reference Bandura1977). Self-efficacious individuals will tend to tackle threats head-on.Footnote 7 In the context of refugee situations, the ability to identify threats enables individuals to bet on a return to their country of origin even while the threat of violence persists.

The more familiar an event is and the more knowledgeable the individual experiencing it, the less likely they are to fear similar events in the future. A series of studies of responses to terrorist violence and natural disasters illustrate why this might be the case. Societies experiencing rare large-scale terrorist events are more likely to have higher stress and anxiety levels due to the uncertainty shock of the event (Galea et al. Reference Galea, Ahern, Resnick, Kilpatrick, Bucuvalas, Gold and Vlahov2002; Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Brewin, Greenberg, Simpson and Wessely2005). However, those experiencing “chronic” terrorism are considerably less likely to exhibit fear and uncertainty regarding future violent events (Spilerman and Stecklov Reference Spilerman and Stecklov2009). This may be why risk assessment differs between experts and the public on a wide variety of issues (Slovic Reference Slovic1987). For example, “repeated bombing- related media exposure [after the Boston Marathon bombings] was associated with higher acute stress than was direct exposure” (Holman, Garfin, and Silver Reference Holman, Garfin and Silver2014). Other research shows residents who refused to evacuate, despite impending warnings of a natural disaster, were those who had successfully overcome similar previous disasters (Strang Reference Strang2014). Furthermore, individuals who were surveyed about hypothetical disasters exhibited exaggerated concerns if they had not previously lived through an event of the same type (Reinhardt Reference Reinhardt2017).

Taken together, these logics imply individuals with stronger attachment to their homelands may have been more likely to be exposed to violence prior to fleeing and, thus, may also prefer to return when possible. Additionally, their prior exposure and “expert” status helps to ensure they can better assess and tolerate risk associated with the potential for future exposure. By contrast, refugees who fled their homes prior to direct exposure to violence may have done so because of less attachment to that location and are likely to feel greater uncertainty regarding future potential exposures and, thus, be unwilling to accept the risk. Their skepticism and anxiety about the situation make them less willing to return to their country of origin. Accordingly, this leads to the following pair of hypotheses that contradict hypothesis 1:

H2a: Refugees exposed to violence before displacement are more likely to want to return to their country of origin.

H2b: Refugees with a stronger attachment to their homelands are more likely to want to return to their country of origin.

Finally, social anchor theory posits individuals’ social networks in informal and formal social settings serve to anchor them within a community (Clopton and Finch Reference Clopton and Finch2011). Social anchors foster a sense of collective identity by contextualizing and rooting personal relationships. Linking identity, security, and integration in migration processes, Grzymala-Kazlowska (Reference Grzymala-Kazlowska2016, 1131) identifies social anchoring as “the process of finding significant reference: grounded points which allow migrants to restore their socio-psychological stability in new life settings. The anchors people use allow them to locate their place in their world, give form to their own sense of being and provide them with a base for psychological and social functioning.”

Social anchors take on various forms, including “legal and institutional (e.g., personal documents, legal status, access to formal institutions), economic (economic resources, consumed goods, types of economic activity), spatial and environmental (such as place of birth, place of residence)… social and professional (e.g., family roles, occupation, being an immigrant), a position in social structure and group belonging (real or imagined)” (Grzymala-Kazlowska Reference Grzymala-Kazlowska2016, 1131). Anchoring can, thus, be understood as what allows individuals to connect or disconnect from various social and spatial places.

With respect to refugee situations, just as they have previously detached from their home locations, refugees can become anchored to host communities to varying degrees. They may, for example, have familial networks, economic stability through a job, or access to education for their children. Refugees with these social anchors are likely to feel more rooted and secure in the host nation and may perceive returning to their countries of origin to be too risky. Accordingly, this leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Refugees socially anchored to the host state are less likely to want to return to their country of origin.

Research Design

To test our hypotheses, we draw upon an original survey of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. We do so by pursuing two complementary modeling strategies, using observational and experimental elements of our survey. Our observational survey analysis examines our full set of theoretical expectations. We complement these analyses with a conjoint experiment. As our theory suggests, place attachment and prior exposure to violence are likely to vary together: individuals most attached to their hometown are those most likely to have been pushed out as violence was closing in on them. The goal of the conjoint experiment is to disentangle these two mechanisms in order to examine whether individuals’ prior exposure to violence is likely to affect their risk calculations upon return.

It is important to highlight some key traits of this research design. First, Syrian refugees are the largest single-country share of the global refugee population, and Lebanon hosts the largest per capita population of refugees globally. Accordingly, investigation of this population of Syrian refugees in Lebanon provides a great opportunity to focus upon combinations of preflight characteristics and flight-related factors that appear to influence decision making.Footnote 8 Second, our data collection benefits refugee communities by providing a platform for their preferences in ongoing debates on repatriation. Third, our survey team’s priority was doing no harm (Fujii Reference Fujii2012; The Belmont Report 1978; Wood Reference Wood2006).Footnote 9

Survey Sample

We surveyed nearly 2,000 Syrian refugees throughout Lebanon during June and July 2018.Footnote 10 According to the official statistics of the UNHCR, over 1,000,000 Syrians are living in Lebanon. They are distributed throughout the country, with 70% living in residential buildings and 30% in unofficial settlements and camps. Our goal was to try to ensure the distribution of survey responses reflected the geographic distribution of the refugee population. To do so, we first grouped the eight governorates in Lebanon into four contiguous governorate pairs (regions) and used the known distribution of refugees in these regions to determine a proportionally representative survey distribution per region.Footnote 11

Second, we further distributed the governorate-pair survey quota across the 24 districts of the country, such that the number of responses per district would be proportional to the size of the refugee population in each district, as determined by the UNHCR at the time of fielding.Footnote 12 We then selected towns or settlements within each district such that their probability of being selected was proportional to the size of the refugee population in each town or settlement. Because all refugees must register with municipalities, we were able to obtain a household listing of Syrian refugees for each town. Typically, Syrian refugee households were clustered within a town. Within each town, we used systematic sampling to select households from this listing: the starting household in each town or settlement was randomly selected from the list until an adult respondent who was willing to participate was found (only one individual per household was selected). The enumerator team then skipped three houses to go to the fifth house on the list to request their next participant. This process continued until options in a specific town were exhausted or the required number of surveys were completed. The same method was applied in unofficial settlements: after the first tent was chosen enumerators skipped the next three to choose the fifth.

Observational Analyses

We focus first on our observational analyses. For our dependent variable, we rely upon a question assessing respondents’ feelings about the possibility of returning to Syria. The question asked, “How much do you disagree/agree with the following statement: I would NOT return to Syria under any circumstances.” Respondents answered on a seven-point scale ranging from strongly agree (meaning they would NEVER return to Syria) to strongly disagree (meaning they WOULD return to Syria). From the responses, we generate our primary dependent variable, never return ordinal. Given the structure of these data, we run analyses using a series of ordered logistic regressions.

We group our primary independent variables based upon our three hypotheses. Experienced violence is a dichotomous indicator coded 1 if the refugee personally experienced violence in Syria before departing their hometown and 0 otherwise. Each respondent was asked whether they experienced the following: physical assault/beaten, physical and mental torture, abduction, sexual violence, forced labor, wage theft, shot at, or shelling. If the respondent answered that they experienced at least one of these types of violence, the variable is coded as 1. We use this variable to test the competing hypotheses 1 and 2a.

We then code four variables to test hypothesis 2b, which refers to hometown attachment. The first, proportion of hometown that fled, is a categorical variable differentiating individuals who fled when almost none/a small proportion (baseline), half, or most/all of their hometown had already fled. The second, discussed fleeing, is a binary variable, coded 1 if, prior to their displacement, the individual talked about fleeing with their household, neighbors, family, community leaders, local authorities, or on online forums and 0 otherwise. These two variables are closely associated. Both capture whether migration intentions were being formed prior to flight or whether the individual was, instead, pushed out by violence. We expect that, if an individual is attached to their homeland, they are less likely to flee unless they are being pushed out by violence. As such, hypothesis 2b would be confirmed by a positive relationship between the proportion of hometown that fled and willingness to return to Syria and a negative relationship between discussed fleeing and willingness to return to Syria.Footnote 13

We also include two additional variables to capture an attachment to the homeland, all dichotomous. The first indicates whether the individuals resides in a Syrian neighborhood in Lebanon. Networks of individuals with a shared community origin provide certain positive externalities that are specific to the location where contacts reside, which include reducing the “psychic costs” of leaving a familiar environment (Barrett and Mosca Reference Barrett and Mosca2013; Faini and Venturini Reference Faini, Venturini, Epstein and Gang2010; Massey et al. Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouaouci, Pellegrino and Taylor1993; Sjaastad Reference Sjaastad1962). Living in a location surrounded by individuals with shared community origin helps individuals maintain the familiar connection to their homeland through the maintenance of shared customs and traditions. The second indicates whether the refugee was employed before the outbreak of the war, which would have constituted an important anchor to the homeland.

Finally, to test hypothesis 3, we create eight binary variables capturing social attachment to Lebanon. Recall that our theory considers social anchors to be any institution—be it social, economic, physical, political, legal—which may be a source of sociopsychological stability for refugees (Clopton and Finch Reference Clopton and Finch2011; Grzymala-Kazlowska Reference Grzymala-Kazlowska2016). Whether an individual has close family in Lebanon who are employed at the time of the survey, whether they think the situation in Lebanon has gotten worse since their arrival, whether they live in a camp, whether they are comfortable reporting crimes, and whether they are registered with the United Nations are all indicators of anchoring and stability.Footnote 14 We also include whether they believe it is easy to cross the Lebanese/Syrian border. Ease of border crossing facilitates attachment to the host country because it allows individuals to make short trips back to Syria, while keeping their family in Lebanon. Finally, we include whether their household is larger than five individuals. As migration is often considered a household decision, that the family has managed to reunite may signal the end of a sequential migration process (Haug Reference Haug2008).

Our control variables include the length of time, in years, the individual has been displaced from Syria as well as variables measuring individuals’ demographic characteristics and their prewar situations. This includes their gender, age, whether they have children, and their prewar income and education. We also include Syrian district fixed effects to account for unobserved heterogeneity based on their hometown locations in their country of origin.Footnote 15

At first glance, the controls lack some intuitively important factors. While the literature on refugee repatriation highlights a lack of economic opportunities in the host state and social networks at home as drivers for return, our survey sample shows no variation in responses on these questions. Almost all respondents say Lebanon has few economic opportunities for refugees. Similarly, almost all refugees still have family and connections remaining in Syria. Additionally, all respondents reported being Sunni Muslim. Thus, we have no variation in identity to leverage. However, this is representative of the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon and not a limitation of our study. While these factors may affect individuals’ likelihoods of returning, we are unable to test this given the homogeneity in responses. If anything, this allows us to capture dynamics of the individual’s context of flight more clearly.

Results

To capture a preliminary understanding of our variables of interest, we provide descriptive cross-tabulations in Table 3 in Appendix D. These show that, on average, most refugees disagree with the statement that they would never return to Syria, which provides initial support for a place attachment to the homeland, as proposed in hypothesis 2. At the same time, some variables capturing an attachment to Lebanon or detachment from Syria show respondents wanting to stay in their host state. For instance, refugees who believe the situation in Lebanon is about the same as before and those who discussed fleeing are more likely to agree with the statement that they would not return to their country of origin.Footnote 16

Next, Table 2 presents the results of our ordered logistic regression assessing whether respondents agreed with the statement that they would never return to Syria. Column (1) displays the results of experiencing violence. Column (2) adds circumstances related to connections to the homeland. Column (3) presents results examining social attachment to the host country. Our final ordered logistic regression in Column (4) includes all variables in one model.

Table 2. Decision to Flee on Desire to Return to Syria at Some Time

Note: Syrian hometown fixed effects omitted. † p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Our theory suggests refugee decision making is influenced by anchoring effects whereby prior exposure to violence affects future decision making. Our primary independent variable of interest, experienced violence, is positive and significant in all model specifications. Our results reflect that refugees who experienced violence are more likely to disagree with the statement that they would never return to Syria under any circumstances, which supports hypothesis 2a.Footnote 17 Individuals are more willing to return to Syria at some point even if they experienced violence before being displaced from their hometowns. This is consistent with the idea that they might have developed adaptive strategies to identify threats and find ways to manage them and, thus, be more willing to risk exposure to violence upon return than individuals who have not previously been exposed to violence. Further on this point, we refer the reader to a discussion of existing evidence and descriptive statistics on gender and violence in Appendix F. Additional regressions and conjoint analyses show that gender does not appear to significantly condition the relationship between experience with violence and willingness to return, nor does it appear to condition risk calculations. The finding that experiences with violence affect both men and women’s willingness to return is striking because acts encountered across genders are very distinct (see Table F.2 in Appendix F). This finding may suggest further support for our hypothesis that refugees exposed to violence in Syria are more likely to have developed adaptive strategies to identify and manage the threats they are likely to encounter upon return—and these threats are likely to be very different depending on whether the refugee identifies as a man or a woman. We also find that men are, in general, less willing to return. This may be due to the prospect of forced conscription (European Institute of Peace 2019).

Our anchoring logic suggests a secondary mechanism, which is intrinsically tied to lived experiences: place attachment. Individuals with greater attachment to their hometown are expected to be most likely to wait until the last minute to flee. This appears to be empirically validated by the observation that the higher the proportion of individuals who had already fled the respondent’s hometown the more likely that individual would return to Syria at some stage.

Similarly, if the individual currently resides in a Syrian neighborhood in Lebanon, they also appear to prefer to return to Syria at some stage. However, if individuals discussed fleeing with others before doing so, they are less willing to return to Syria under any circumstance. This suggests that those who had a conversation about the decision to flee did so because they found it easier to detach from their home location in the first instance. These individuals are contrasted with refugees who may not have had the time to discuss migration plans and became displaced against their intention. Employment before the outbreak of the civil war does not seem to influence return intentions.

As per our theoretical framework, evidence for hypothesis 2a and hypothesis 2b jointly support the presence of anchoring to the country of origin. However, we are more confident in our ability to observe our place-attachment mechanisms. Examining when an individual fled in relation to others in their hometown who were at similar risk of encountering violence is a relatively clear measure of place attachment. However, we can only assess individuals’ perceived self-efficacy and ability to assess risks indirectly by observing the relationship between lived experiences and return intentions. Our second set of analyses will complement these results by allowing us to examine this mechanism more directly.Footnote 18

Next, we identify variables signifying an attachment to the host state. Refugees who believe that the situation in Lebanon is worse than when they arrived are more likely to prefer return. Also, those who believe it is easy to cross the Lebanese/Syrian border are less likely to desire return, yet this could be explained by the fact it is easy for them to go back and forth informally, meaning there is no need to return formally to war-torn Syria. However, those with close family in Lebanon, a job, and registration with the UN are all more likely to prefer returning to Syria. In other words, we find limited support for hypothesis three on social anchors in the partial Model 3. Nonetheless, these effects appear more muted in the comprehensive Model 4. It is possible that, while close family, jobs, and legal documentation serve as a social anchors in normal circumstances, Syrian refugees are more likely to have precarious jobs and face a great deal of legal obstacles, even if they are registered with the UNHCR (Nassar and Stel Reference Nassar and Stel2019), and may wish to return to Syria with their close family.

Figure 1 displays the average marginal effect of factors leading up to displacement, using results from comprehensive Model 4. The first panel demonstrates that 71.7% of refugees who experienced violence disagree with the statement that they would never return to Syria. This goes against common assumptions that refugees who experienced violence would never desire to return to their country of origin (hypothesis 1) and offers compelling evidence in support of hypothesis 2a.

Figure 1. Average Marginal Effect of Displacement Factors on Never Returning to Syria

The rest of the panels presented in Figure 1 also reflect some rather stark trends; 36.6% of individuals who discussed fleeing (prior to doing so) agree that they would never return to Syria under any circumstances, compared with 27.4% that did not have such discussions. Additionally, 37.6% of refugees who were among the first to flee their hometown disagree that they would never return to Syria, compared with 66.4% and 68.2% of those where half or most of their hometown had fled, respectively. Each of these findings offer support for hypothesis 2b.

Figure 2 displays the average marginal effects of respondent’s perceptions of conditions in the host state. These findings illustrate some evidence for hypothesis 3. The left panel shows that refugees who feel it is easy to cross the Lebanese/Syrian border are more likely to prefer never returning. However, respondents who believe the situation in Lebanon continues to worsen are more likely to prefer returning than those who believe the situation in Lebanon is about the same as before. The middle panel shows that 68.8% of refugees who live in predominantly Syrian neighborhoods in Lebanon want to return at some point, signaling an attachment to home rather than host.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Effect of Host Factors on Never Returning to Syria

Conjoint Analyses

In the above analyses, we find individuals that experienced harm before fleeing are more likely to consider returning when conflict is ongoing. In this section, we probe this further. In hypothesis 2a, we posited refugees directly exposed to violence in Syria are more likely to have developed adaptive strategies to identify threats and manage them. This means they are more likely to risk exposure to violence upon return than individuals not previously exposed to violence. However, individuals exposed to violence are also likely to be those with greater place attachment, who waited until the last minute to flee. As we posit in hypothesis 2b, place attachment is likely to drive return decisions in its own right.

Because place attachment and prior exposure to violence are likely correlated, it is difficult to disentangle these explanations using standard survey items. We use a conjoint experiment to isolate the effects of prior exposure to harm on risk assessment upon return to Syria (hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2a). That is, we seek to examine risk assessment independently from confounding variables such as hometown attachment.

In the conjoint setup, respondents are given two hypothetical destinations in Syria to which to consider returning. These destinations vary in terms of key attributes, including probability of violence en route. Because the attributes of the choice are varied randomly across return options and across a series of choice tasks, we are able to examine the effects of a respondent’s prior exposure to harm on return risk calculations independent of hometown attachment or other confounding variables. Our theoretical framework suggests that individuals’ heterogeneous lived experiences will affect assessments on return to their hometown—a setting where they encountered these experiences. In the conjoint analyses, we expect individuals to factor their actual prior experiences into their conception of what harm could look like en route to a hypothetical destination.

A random sample of 406 respondents from our survey sample were each presented with five return tasks consisting of a choice between two location profiles, each consisting of four attributes. Of interest here is the attribute “chance of harm en route to that location.” However, we also included the chance of a peaceful situation lasting at least a year there, the number of people the hypothetical migrant would know there, and the ease of finding work. These tasks prompted individuals to consider a hypothetical migrant like themselves: “I would like you to imagine a person, like yourself, but this person is considering a return to Syria. I would like you to consider the following two places in Syria, where there is currently no fighting taking place, and I would like you to tell me which place in Syria you think this person should go to.” Respondents were then asked to state their preferred choice from two hypothetical alternatives in Syria generically labeled “Place A” and “Place B.” Respondents were asked to choose between one of these two location alternatives or skip the task if they did not know or did not want to answer. On average, each respondent completed 4.9 tasks. The values for each attribute were independently and randomly varied as per the levels shown in Table 3. An example of a choice task is shown in Table 4.

Table 3. Attributes and Possible Levels for the Conjoint Experiment

Table 4. Example of Choices from the Conjoint Experiment

In our analysis, we follow the statistical approach for conjoint analysis developed in Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Specifically, we estimate the average causal effect of an attribute level relative to a baseline level, or the average marginal component effect (AMCE). The AMCEs are akin to treatment effects in a standard survey experiment, where the treatment is compared with a particular control condition (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins, Yamamoto, Druckman and Green2021, 15; Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). This is possible due to the randomization of the attribute levels whereby the effect of a level on the probability of choice is estimated by taking the probability that alternatives with that level, across all sampled levels of all the other attributes, are chosen compared with alternatives with a different level of that attribute.

In our conjoint, the assignment of levels to profiles is fully random such that each respondent has an equal chance of viewing any given attribute–level combination (out of all possible combinations) within a profile. As such, the sets of profiles involving each level should be balanced (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). This can be investigated by looking at the omnibus tests of the fits of regression models of any of the respondent characteristics against the attribute levels. As shown in Appendix G, we find no evidence of imbalance (all p > 0.05) with respect to any of our variables.

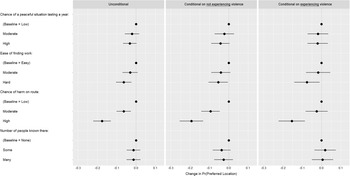

Figure 3 shows the causal effect of the change in the attribute level from the reference level of the conjoint experiment. The left panel displays all observations, the middle panel shows estimates from those who did not experience violence, and the right panel displays effects of respondents who experienced violence prior to their displacement. The unconditional results show that refugees prefer to return to locations in Syria where there is a smaller chance of experiencing harm on the journey there. This effect is similar when examining refugees who did not experience violence firsthand before fleeing. On the other hand, of refugees who experienced violence, there is no statistically significant difference between moderate and low levels of harm en route. This supports our argument that refugees who lived through violence likely perceive that they are well placed to manage the potential for harm on a future journey. The only other attribute with a statistically significant effect was ease of finding work: refugees who believed it would be hard for them to find employment were less likely to choose that location. This seems intuitive and aligns with expectations from the existing literature.

Figure 3. Estimated Effects of Attributes of Return Locations in Syria

Conclusion

There are now 26 million refugees globally: the largest such number since the end of World War II. Existing policies dealing with refugee crises neither ease the disproportionate burden on neighboring countries serving as hosts nor strengthen temporary protections until repatriation is deemed feasible. This pushes attention toward the possibility of voluntary repatriation as a solution to protracted refugee situations. However, even though we have witnessed a slight uptick in levels of repatriation in recent years, this still benefits no more than 5% of the total global refugee population and is often critiqued as being forced rather than voluntary. Nonetheless, refugees wish to return to their homes. It is important, therefore, to understand these preferences before knowing whether to recommend pushing an agenda for more comprehensive repatriation. Indeed, states need to protect the right to return safely and in dignity of refugees who wish to repatriate. This is necessary to both uphold their human rights and recognize their agency as they renegotiate their relationship with their nation state, as citizens (Bradley Reference Bradley2013).

This paper addresses this gap by asking what factors inform refugees’ preferences regarding the potential to return home. To answer this question, we deployed an original survey of nearly 2,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Both observational and experimental analyses demonstrate those who were exposed to violence prior to their displacement to Lebanon wish to return to Syria. We argue these refugees harbor a stronger attachment to Syria, while also better understanding their tolerance of violence, because they are “experts” and are more capable of assessing risk. In contrast, refugees who were not directly exposed to violence before fleeing are more unsure of the threats associated with returning and are unwilling to accept the risk of doing so.

We also find that individuals who endured the difficulties of the Syrian Civil War longer than most of their hometown’s fellow residents are more likely to desire to return to Syria. The same is true of those who settled in predominantly Syrian neighborhoods in Lebanon. We argue that these effects are also observed effects of anchoring to their homeland.

At the same time, some refugees develop a sense of attachment to their host country. While socioeconomic indicators such as employment or living with family do not anchor our sample of refugees to their host state, other conditions, such as the situation in Lebanon and ease of crossing the border, influence preferences to return. These findings suggest that refugees can develop different preferences regarding returning home and that this may depend upon relative attachment to home and host countries.

Asylum rights globally are being eroded, particularly since developed states refuse to contribute to providing safe haven to refugees. As developing states continue to take on most of the physical responsibility for accommodating refugees, we offer tentative policy recommendations. More attention needs to be paid to the conditions on the ground in these overburdened neighboring states. Only by enhancing refugee experiences in the host country can we expect to encourage more refugees to want to remain in the relatively safe conditions of the host state. Beyond this, it is necessary to work to better accommodate refugees who hold strong preferences to return. This presumably means finding ways of ensuring safe passage for refugees to complete voluntary repatriation while also working to protect against coerced repatriation.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000344.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UGI0MH.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

Previous drafts of this manuscript were presented at the annual meetings of the 2019 American Political Science Association and 2020 Southern Political Science Association, and we would like to thank all participants for their comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank Laura Bakkensen, Christopher Blair, Kanisha Bond, Rana Khoury, Milli Lake, Sarah Parkinson, Justin Schon, Stephanie Schwartz, Jim Walsh, Beth Wellman, and Beth Whitaker, as well as the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on the project.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The research was funded in part by award W911-NF-17-1-0030 from the Department of Defense and U.S. Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory under the Minerva Research Initiative. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Department of Defense or the Army Research Office/Army Research Laboratory.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was deemed exempt from review by the University of Arizona. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research. The authors have disclosed ethical issues related to this research in Appendix B.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.