Introduction

Vaccines have continued to play a crucial global role in preventing infectious diseases in the twenty first century.Footnote 1 The Covid-19 pandemic has underlined their importance, with vaccines seen as the best way to protect the public from coronavirus.Footnote 2

A longstanding problem of governments has been the extent to which they should assume responsibility for the compensation of those injured by vaccines. This paper provides a timely reappraisal of the vaccine damage schemes currently available in the US and UK in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic. While the US and UK have different legal systems, there are of course many similarities in their Anglo-American tort law heritage, as well as in their shared experiences of the controversies concerning the pertussis and the Measles Mumps Rubella (MMR) vaccines.Footnote 3 It seeks to argue that any improvements to both the US and UK schemes should be included in a revised national vaccine policy which takes into consideration their respective long-term national vaccine strategies to prepare for future pandemics.

Part 1 explores development of the US National Childhood Vaccine Injury Compensation Act of 1986 (NCVIA), and the establishment of the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Programme (VICP), in the light of increased litigation costs, the rise in prices of vaccines and the instability and unpredictability of the childhood vaccine market subsequent to the Swine Flu Act 1976. While acknowledging criticisms of the NCVIA, it considers that there is much to be said for the success of the VICP. It examines the role of the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act of 2005 (PREP), which offers ‘targeted liability protection’Footnote 4 to the manufacturers of drugs, vaccines and medical devices used in declared public health emergencies. This Act is controversial in that, through broad immunity and limitations on compensation, recourse for victims is extremely limited. The issuance of a Covid-19 Declaration has triggered the broad immunity provisions of the PREP Act and has provided that a ‘Covered Countermeasure Process Fund’ will cover serious injuries or death as a direct result of Covid-19 vaccines.Footnote 5

Part 2 examines the UK Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979, which was enacted to provide an ex gratia payment for vaccine-damaged persons for death or severe disablementFootnote 6 proved on a balance of probabilities to have been causedFootnote 7 by vaccination. The determination of causation continues to be a major source of difficulty in Tribunal appeals and the paper explores concerns about determining the causation issue in favour of applicants using biologically plausible theories, despite the absence of independent scientific evidence supporting a causal association. The decision to extend the 1979 Act to those vaccinated against the Covid-19 virus, as opposed to the creation of a bespoke Covid-19 vaccines compensation system in the UK, is appraised.

Part 3 argues that any improvements to the US and UK schemes should be included in a revised national vaccine policy which takes into consideration the countries’ respective long-term national vaccine strategies to prepare for future pandemics. This policy must promote public health by incentivising innovation in the design of new vaccines, whilst encouraging public confidence in vaccines through transparent and fair decision-making that is soundly based on scientific evidence.

This paper supports the adoption of a UK-wide National Vaccine Injury Compensation Programme to be administered by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, similar to that in existence in the US. Learning from previous controversies over the determination of causation, a new programme must define the criteria used to determine causation, giving sufficient weight to scientific evidence. To balance the need for rigorous criteria to determine causation with the need for fairness, the programme should adopt the US practice of allowing negotiated settlements between the parties where there are close calls concerning causation.

1. Vaccine compensation schemes in the US

(a) Swine Flu Act of 1976

In February 1976, isolates of virus taken from two recruits at Fort Dix, New Jersey, who had influenza-like illnesses, included a new strain – A/New Jersey/76 (Hsw1n1) (H1N1) – similar to the virus believed to be the cause of the 1918 pandemic, known as ‘swine flu’. These findings were reviewed by the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices of the US Public Health Service (ACIP), who recommended the launch of an immunization programme to prevent the effects of a potential pandemic.Footnote 8 The National Influenza Immunization Program (NIIP) was then initiated.Footnote 9 Due to concern over vaccine manufacturers’ liability when insurers declared they would end coverage for vaccine manufacturers,Footnote 10 the Swine Flu Act 1976 was passed, transferring the manufacturer's liability for injuries to the US Government.Footnote 11 By virtue of its ‘unique role in the initiation, planning and administration of the swine flu program’,Footnote 12 an exclusive remedy was provided against the US government ‘for personal injury or death arising out of the administration of swine flu vaccine under the swine flu program and based upon the act or omission of a program participant’.Footnote 13 The programme adopted a no fault approach to the provision of compensation, requiring a determination as to whether the plaintiff's injuries were in fact caused by the vaccine's administration.Footnote 14 The results of a Center for Disease Control (CDC) study suspended the programme after establishing an apparent temporal association between the onset of Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) within 10 weeks of vaccination and the vaccination itself, which was sufficient to presume causation.Footnote 15 The government limited its liability under the 1976 Act to cases where a causal link could be shown between GBS and the vaccination. This was a heavy burden of proof to overcome since there was at the time (and there remains to this day) no understood causal path between the vaccination and the syndrome.Footnote 16 A ‘vast field’Footnote 17 of litigation commenced, with experts attributing many injuries to the vaccine. Cases in which GBS occurred within 10 weeks of the vaccination were all deemed compensable,Footnote 18 and virtually all other cases where GBS occurred outside the 10-week period were deemed uncompensable.Footnote 19 However, it is apparent that the uncertainty in respect of proof of causation in specific cases resulted in several courts providing compensation irrespective of causal link.Footnote 20 By 1985, $90 million had been paid out by the government to those who developed GBS and this led to increasing governmental reluctance to assume such financial risks with vaccination programmes in the absence of scientific evidence.Footnote 21

(b) National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986

(i) Background

Extending the scope of strict liability and litigation costs,Footnote 22 the rise in prices of vaccinesFootnote 23 and the instability and unpredictability of the childhood vaccine market,Footnote 24 together with increasing concern over the uncertainties of obtaining compensation for injuries due to vaccines, all led to Congress passing the NCVIA in 1986.Footnote 25 The central achievement of the Act was the establishment of the National VICP, under which compensation may be paid for a vaccine related injury or death.Footnote 26 It is administered by the US Claims CourtFootnote 27 and claims for compensation for a vaccine-related injury or death are initiated by a petition.Footnote 28

(ii) Limitations on awards

The increasing governmental reluctance to accept financial risks with vaccine programmes resulted in the NCVIA capping certain types of awards.Footnote 29 Thus the petitioner can recover actual unreimbursable expenses and reasonable projected unreimbursable expenses which are for diagnosis and medical care or for rehabilitation,Footnote 30 but ‘actual and projected pain and suffering, and emotional distress’ is limited to $250,000.Footnote 31 Awards for a vaccine-related death are capped at $250,000.Footnote 32 For those injured by a vaccine after attaining the age of 18, compensation for loss of earnings is limited to ‘actual and anticipated loss of earnings determined in accordance with generally recognized actuarial principles and projections’.Footnote 33 In addition, compensation awarded under the NCVIA – unlike under the Swine Flu Act – is secondary to any payment made under any state compensation programme, under an insurance policy or under any Federal or state health benefits programme, or by an entity providing health services on a prepaid basis.Footnote 34 Importantly, in awarding compensation the NCVIA authorises payment of reasonable attorney fees and other costs incurred in any proceeding.Footnote 35

(iii) Criticisms

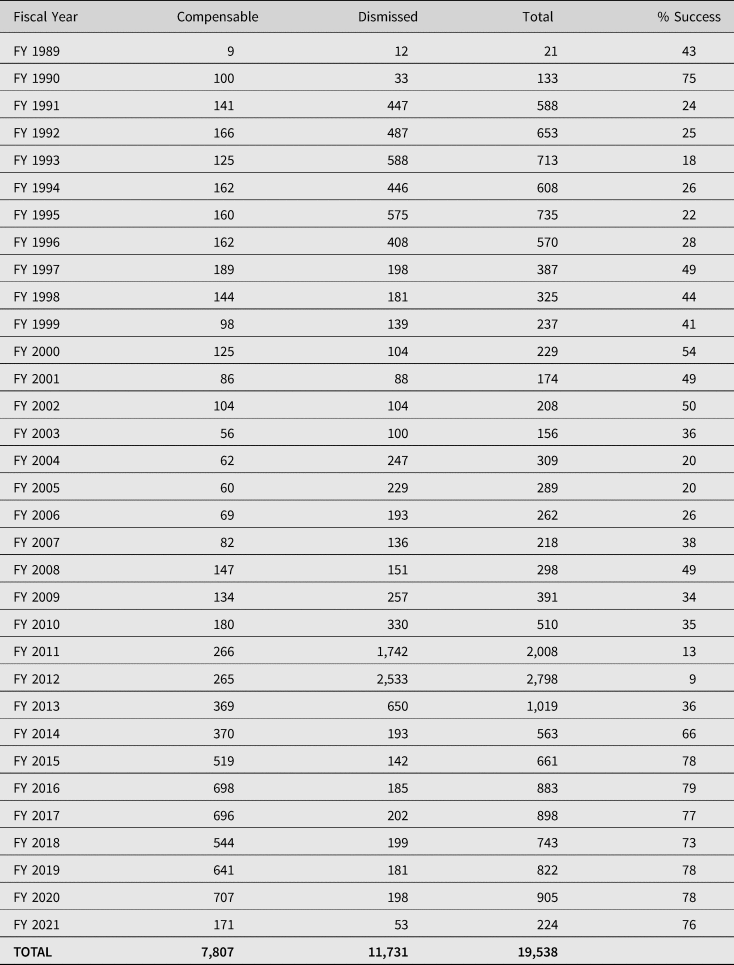

Stakeholders have reported the perception of an adversarial environment, due to the onus on petitioners to show that a covered vaccine caused the injury when there are no associated injuries on the Table.Footnote 36 In addition, there has been widespread criticism of the failure to expedite adjudications. Between 1999 and 2014, VICP claims filed have taken on average five and a half years to adjudicate.Footnote 37 However, for the more than 1,400 claims filed since 2009, the average time to adjudicate a claim reduced to 1.6 years. It is thought that one of the reasons for this was that the majority of autism claims were filed prior to 2009 and that these claims may have taken longer as they were part of the Omnibus Autism Proceeding (OAP) (2002–2010), denying claims that autism was a vaccine injury.Footnote 38 In its most recent statistics report published on the VICP (January 2021), the Division of Injury Compensation Programs (DICP) noted that on average it now takes 2 to 3 years to adjudicate a petition after it is filed.Footnote 39 Further, since its inception in 1988, 19,538 petitions have been adjudicated, with 7,807 determined to be compensable and the other 11,731 dismissed. The total compensation paid over the life of the programme is approximately $4.5 billion.Footnote 40 Significantly, by far the majority (about 60%) of all compensation awarded by the VICP results from negotiated settlements between the parties for which the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) review of the evidence has not concluded that the vaccine(s) caused the alleged injury.Footnote 41 With over 3.7 billion doses of vaccine distributed in the US from 2006 to 2018, approximately one individual for every one million doses was compensated.Footnote 42 Of the 3.7 billion doses since 2006, 1.67 were influenza doses (over 45%).Footnote 43 By far the majority of all pending claims (67%) involve influenza vaccines.Footnote 44 Table 1 provides a detailed account of the cases adjudicated since the inception of the VICP. Of the 19,538 cases adjudicated, 7,807 (40%) have been deemed compensable. However, the success rate of the programme has risen considerably over the last seven years, with the special masters deeming approximately 77% of the cases adjudicated to be compensable.

Table 1. Claims adjudicated since the inception of VICP

Source: Department of Health and Human Services HRSA: Data & Statistics

(iv) Table claims, off-table claims and causation

The person who suffered such a vaccine-related injury or died must have been administered a vaccine listed in a vaccine injury table and have suffered an injury covered by the Act and occurring within a specified time listed in the table (the so-called ‘Table claim’).Footnote 45 If a petitioner demonstrates a compensable injury within this time, causation is presumed.Footnote 46 Alternatively, petitioners may claim that they have suffered injuries not of the type covered in the Table, but that they can show by a preponderance of evidence that their injuries were ‘caused-in-fact’ by the vaccination in question (the so-called ‘off-Table claim’).Footnote 47 Since 2009, more than 98% of new claims filed alleged off-Table injuries, which required the petitioner to prove their injury was caused by the vaccine they received.Footnote 48

By comparison with the relaxation of the burden of proving causation for injuries which are Table claims, the burden of proof on the petitioner in an off-Table claim is a heavy one.Footnote 49 As Engstrom has observed: causation questions are problematic in the context of vaccine injuries since they are ‘not traumatic or observable’, nor do they trigger ‘signature diseases’, so that adverse effects caused by vaccines may be caused by other mechanisms, and since vaccines are administered to young infants and children, many neurological disorders are ‘merely coincidental, temporal associations’.Footnote 50 Such facts have complicated the determination of causation under the VICP.Footnote 51 However, one should be cautious of using the existence of ‘elemental scientific uncertainty at the root of the causal inquiry’Footnote 52 as a stick to beat the VICP with. Indeed, it should not be forgotten that the ‘vaccine court was the sole institution in the world to conduct full and public hearings’Footnote 53 of the claims that autism was a vaccine injury, and that ‘[t]he OAP was a tremendous effort to bring closure to one of the most controversial causation questions of our day’.Footnote 54 The OAP test cases have reaffirmed the settled legal position that while there is no requirement on petitioners to produce supporting epidemiological evidence in a causation-in-fact claim,Footnote 55 in the instance in which general causation has been the subject of published epidemiological studies, such evidence should be given appropriate weight, along with the other evidence of the record.Footnote 56 This has reduced the dangers of elevating lower ranking hierarchical evidenceFootnote 57 of biologically plausible mechanisms to connect vaccines to adverse events over published contrary epidemiological studies (at the top of the hierarchy),Footnote 58 though criticism remains that the VICP ‘should more rigorously define the criteria’ to determine causation.Footnote 59 Others have argued that in view of the difficulties in proving causation-in fact cases, the preponderance of evidence standard should be modified to a more generous ‘benefit-of-the doubt standard’, resolving close cases in favour of the petitioner.Footnote 60 A radical approach to causation has been suggested, which is to shift the burden of proof to the government in vaccine injury proceedings to prove by a preponderance of evidence that the petitioner's injury was not caused by a vaccine.Footnote 61 Yet these more generous approaches to petitioners may result in undermining the need to be on the side of science in the resolution of cases and in so doing set an unhelpful precedent in increasing vaccine hesitancy. Asking the Secretary of HHS to prove a negative is an impossible burden to overcome, and one that upsets the balance between the interests of manufacturers, government and petitioners. ‘[S]cience can never demonstrate the absence of hazard’ and it ‘can only place an upper limit on risk’; confusion ‘will always remain …at the lower margins of risk’.Footnote 62 Moreover, as Chief Special Master Golkiewicz has noted, protecting the vaccine's integrity, ‘that is that vaccine[s] do [ ] not cause every injury that follows immunization’,Footnote 63 remains critical to public confidence in vaccines.

Overall, there is much to be said for the success of the VICP despite these controversies, especially in its promotion of ‘wide acceptance of vaccination as a public good that is also humane to those who perceive that they have been injured by this public good’.Footnote 64

(v) Additions to the Table and proposal to remove SIRVA and vasovagal syncope

The majority of claims in the first decade of National VICP (1988–1998) were those alleging injuries on the vaccine injury Table. However, in 2014, the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that the addition of six new vaccines, especially influenza vaccines, to the Table without covered injuries associated with these vaccines, had resulted in the majority of claims filed involving off-Table injuries. Subsequent to the 2014 GAO report, new injuries were added to the Table in March 2017.Footnote 65 These were: anaphylaxis within four hours of administration of hepatitis B vaccines, seasonal influenza vaccines, varicella vaccines, meningococcal vaccines and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, intussusception between 1 and 21 days of administration of rotovirus vaccines, GBS within 3 and 42 days of administration of seasonal influenza vaccines, disseminated varicella vaccine-strain viral disease within 7 to 42 days of administration of varicella vaccines (if the strain determination is not done or the laboratory test is inconclusive), shoulder injury related to vaccine administration (SIRVA) for all injectable vaccines within 48 hours,Footnote 66 and vasovagal syncope within one hour after the administration of several vaccines.Footnote 67

While this has helped counter some of the criticism of a migration away from the Table,Footnote 68 a recent controversial proposal by the Secretary for HHS has been to remove the additions of SIRVA and vasovagal syncope from it.Footnote 69 This has now become an important funding issue, as over 54% of petitions filed in the last two fiscal years are SIRVA claims,Footnote 70 and of these 99.2% were filed by adults.Footnote 71 The essence of the legal argument presented by the HHS is that since the Act defines the term ‘vaccine-related injury or death’ as ‘an illness, injury, condition, or death associated with one or more of the vaccines set forth in the Vaccine Injury table’,Footnote 72 the programme covers injuries ‘associated with the vaccine itself’. SIRVA is not a vaccine and is not an injury caused by a vaccine antigen, but one caused by negligent administration of the vaccine by a health provider. Neither SIRVA nor vasovagal syncope meet the ‘associated with the vaccine’ requirement, as neither set of injuries are associated with the vaccine itself, since if the vaccine is administered properly, these injuries will not occur. As the Table should include only ‘injuries caused by a vaccine or its components, not the manner in which the vaccine was administered’,Footnote 73 both SIRVA and vasovagal syncope should be removed from the Table.Footnote 74

However, the Advisory Commission on Childhood Vaccines (ACCV) unanimously opposed the implementation of the changes to the Table, with three of the four members concluding that, while rare, both SIRVA and vasovagal syncope are injuries that can be caused by vaccination and thus should be compensable under the VICP.Footnote 75 They also considered that removing SIRVA and vasovagal syncope would not provide liability protection to health care professionals who administer them, and thus could lead to potential exposure of vaccine administrators to civil law suits: this in turn could be a disincentive to administering vaccines, resulting in lower vaccination rates.Footnote 76 Notwithstanding the concerns of the ACCV, the rule amending the Table was made final on 21 January 2021.Footnote 77 However, subsequent to a review by the new Democratic administration, the final rule was rescinded by a further final rule on 21 April 2021 for both procedural and policy reasons.Footnote 78 As a policy matter, HHS concluded that the rule would have a negative impact on vaccine administrators, and would be at odds with the Federal Government's efforts to increase confidence in vaccinations in the US, especially the Covid-19 campaign, as well as other campaigns such as annual influenza vaccination efforts.Footnote 79 It was also noted that a further reason for rescission of the rule was to allow HHS sufficient time to consider the state of the science concerning SIRVA.Footnote 80 It is submitted that HHS's rescission was correct: a careful and methodical consideration of the science regarding the definition is essential to the success of the VICP. A coherent vaccine policy which includes compensation must be based on the latest and most accurate peer-reviewed evidence. While the creation and amendment of decision aids involving compensation are ‘politically charged’,Footnote 81 that must not be allowed to undermine the need for their review as science evolves, but this must be undertaken in a considered manner.

(c) Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act of 2005 (PREP)

(i) Scope of immunity

As a result of concern emerging in 2006 about the spread of avian influenza (H5N1),Footnote 82 ‘targeted liability protection’,Footnote 83 known as the PREP Act, was offered to the manufacturers of drugs, vaccines and medical devices used in declared public health emergencies.Footnote 84 The Act provides immunity to any ‘covered person’, ie a manufacturer, distributor or administrator, with respect to ‘all claims for loss caused by, arising out of, relating to, or resulting from’ the ‘administration to’ or ‘use by’ an individual of a ‘covered countermeasure’, ie drugs, vaccines or medical devices, providing a declaration has been issued with respect to such a countermeasure.Footnote 85 The extent of the immunity is extremely broad. It applies to ‘any type of loss’, including: death, physical, mental, or emotional injury, fear of physical, mental or emotional injury, and loss of or damage to property,Footnote 86 where the loss ‘has a causal relationship with the administration to or use by an individual of a covered countermeasure’.Footnote 87 This includes ‘a causal relationship with the design… manufacture, labeling, … marketing, promotion, sale, purchase, … prescribing, administration, licensing, or use of such countermeasure’.Footnote 88 The sole exception to immunity from suit is for death or serious physical injury caused by wilful misconduct.Footnote 89

(ii) Compensation

While immunising vaccine manufacturers from liability, the PREP Act provides for compensation for covered injuries directly caused by the administration or use of a covered countermeasure from an emergency fund designated the ‘Covered Countermeasure Process Fund’.Footnote 90 The establishment of a compensation fund is contingent on the issuance of a declaration by HHS.Footnote 91 In implementation of the PREP Act, procedures have been established for the Countermeasures Injury Compensation Program (CICP) to provide medical and lost employment income benefits to those individuals who sustained a covered injury as the direct result of the administration or use of a covered countermeasure.Footnote 92 Only serious injuries or deaths are covered by the CICP.Footnote 93

As with the NCVIA, injuries are eligible for compensation in two ways. First, petitioners can meet the preponderance of the evidence standard that the specified countermeasure probably caused the injury, on the basis of ‘compelling, reliable, valid, medical and scientific evidence’.Footnote 94 Alternatively, if and when HHS establishes a table of injuries concerning the countermeasures, petitioners will be entitled to compensation if the injuries fall within the Covered Countermeasures Injury Table: these injuries are ‘presumed to be directly caused’ by the specified countermeasure, provided that the first symptom or manifestation of each onset of adverse effect occurs within a specified time period.Footnote 95 Stressing the need for the Table to be driven by scientific evidence of causation, the identification of covered injuries for inclusion in the Table must be based on ‘compelling, reliable, valid, medical and scientific evidence that administration or use of the [vaccine] directly caused [the] covered injury’.Footnote 96 As from 8 September 2015, HHS has adopted a pandemic influenza countermeasures injury table, containing presumptive injuries from pandemic influenza vaccines, including the pandemic influenza 2009 H1N1 vaccine.Footnote 97 The Table creates presumption of causation in the event of anaphylaxis within four hours of the administration of pandemic influenza vaccines, and GBS within 3–42 days of the administration of the pandemic influenza 2009 H1N1 vaccine.Footnote 98 Again, as in the case of the NCVIA, if an injury does not fall within the Table, the claimant must prove ‘that the injury occurred as the direct result of the administration or use of a covered countermeasure’ by ‘compelling, reliable, valid, medical and scientific evidence’.Footnote 99 Mere demonstration of temporal association between receipt of the countermeasure and onset of the injury is insufficient by itself to prove causation.Footnote 100

The CICP provides expenses necessary ‘to diagnose or treat a covered injury’, and payments or reimbursements for the provision or future provision of ‘reasonable and necessary medical services and items’.Footnote 101 There are no caps on these medical expense benefits.Footnote 102 The CICP also covers benefits for lost employment income,Footnote 103 and survivor death benefits are potentially compensable.Footnote 104 However, the CICP is significantly less generous than the NCVIA in that there are no damages awarded for pain and suffering.Footnote 105 In addition, no court may review any action of the Secretary for HHS taken under the PREP Act,Footnote 106 and no covered individual eligible for compensation may bring a civil action unless they have exhausted their remedies under the provisions.Footnote 107 Importantly, in contrast to the VICP,Footnote 108 the CICP does not authorise payment of reasonable attorney fees and other costs incurred in any proceeding.Footnote 109 This is likely to prove a major disincentive to claimants who will require the assistance of counsel and expert testimony to determine whether the vaccine caused the injury in off-Table claims.Footnote 110 Further, the limitation period for filing a claim under the CICP is one year from the date of the administration or use of the vaccine that is alleged to have caused the injury,Footnote 111 as opposed to three years after the date of the occurrence of a vaccine-related injury.Footnote 112 As of 1 July 2021, 1,657 claims have been filed under the CICP, of which 29 have been compensated.Footnote 113 All but one of the 29 concerned the H1N1 vaccine, the alleged injury in the overwhelming majority of cases being GBS.Footnote 114 It thus appears that with such broad immunity and limitations on compensation, recourse for victims is extremely limited.Footnote 115

(iii) Covid-19 vaccines and immunity under the PREP Act

On 10 March 2020, the Secretary of HHS issued a Declaration under the PREP Act, effective from 4 February 2020, for certain medical products (covered countermeasures) to be used against Covid-19.Footnote 116 It comes as little surprise that such products include vaccines. Under the Declaration, covered countermeasures are: ‘any antiviral, any other drug, any biologic, any diagnostic, any other device, or any vaccine, used to treat, diagnose, cure, prevent, or mitigate Covid-19, or the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 or a virus mutating therefrom, or any device used in the administration of any such product, and all components and constituent materials of any such product’.Footnote 117 A covered countermeasure must be a ‘qualified pandemic or epidemic product’, which is ‘a drug … biological product … or device [as] defined … [in] the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act … that is … manufactured [or] used … to diagnose, mitigate, prevent, treat or cure a pandemic or epidemic; or … limit the harm such a pandemic or epidemic might otherwise cause’ that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved, cleared or authorised for emergency use.Footnote 118 The issuing of the Covid-19 Declaration triggers the broad immunity provisions of the PREP Act.

As previously noted, the Act provides broad immunity to any ‘covered person’, ie a manufacturer, distributor or administrator, with respect to ‘all claims for loss caused by, arising out of, relating to, or resulting from' the ‘administration to’ or ‘use by’ an individual of a ‘covered countermeasure’, providing a declaration has been issued with respect to such a countermeasure.Footnote 119 Thus the broad immunity would preclude liability claims in negligence by a manufacturer in creating a vaccine, or negligence by a health care provider in prescribing the wrong dose.Footnote 120 An HHS Advisory Opinion has reaffirmed the broad scope of this immunity during the Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote 121 The Covid-19 Declaration provides that the CICP and ‘Covered Countermeasure Process Fund’ will cover serious injuries or death as a direct result of Covid-19 vaccines.Footnote 122 Since no table of injuries concerning Covid-19 countermeasures has been established, petitioners must meet the preponderance of the evidence standard that the Covid-19 vaccine probably caused the injury, on the basis of ‘compelling, reliable, valid, medical and scientific evidence’.Footnote 123 As of 1 July 2021, there have been 1,165 Covid-19 countermeasure claims, 436 of which allege injuries/deaths from Covid-19 vaccines.Footnote 124 Two Covid-19 countermeasures (one of which concerned a Covid-19 vaccine), have been denied compensation since the standard of proof of causation was not met and/or covered injury was not sustained.Footnote 125 It has been predicted that in view of the limitations on compensation of the CICP, those who receive Covid-19 vaccinations during the life of the Declaration would be less likely to receive compensation than they would under the VICP, and that the process for pursuing compensation will be lengthier, more difficult and expensive in the absence of reimbursement of reasonable attorney fees.Footnote 126 In a highly critical assessment of the decision to place Covid-19 vaccine claims for compensation within the CICP,Footnote 127 describing it as ‘an extremely restricted compensation scheme’,Footnote 128 and one where decisions to grant or deny compensation are unpublished,Footnote 129 it has been submitted that a fairer compensation programme is needed, based on the best features of the VICP and the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund.Footnote 130 On the other hand, manufacturers have argued that such broad protection is justifiable, given the expectation of government and the public that they develop and manufacture such vaccines as quickly as possible.Footnote 131 The difficulty remains that, viewed as a less generous scheme than the VICP with broad immunity and less accountability in the absence of judicial review of HHS decisions, the CICP may be seen as reducing the risk of vaccine manufactures at the expense of populist distrust about government, public health decision-makers and the safety of vaccines.Footnote 132 As Covid-19 vaccinations continue to be recommended by the CDC,Footnote 133 the pressure to mandate coronavirus vaccines continues to rise,Footnote 134 and society benefits through individual vaccination, the arguments in favour of inclusion of such vaccines in the VICP seem strong.

2. The UK's vaccine damage payments scheme

(a) Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979

(i) Background

While the UK government initially resisted pressure generated by the Association of Parents of Vaccine Damaged Children for compensation, their hand was forced by several factors. The first was a rise in vaccine hesitancy in the early 1970s concerning the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine. Vaccination rates had dramatically declined between 1971 and 1975 and by the summer of 1977 the national vaccine programme was in crisis.Footnote 135 Secondly, in its wide-ranging investigation of the question of compensation for vaccine damage,Footnote 136 the Pearson Commission concluded that since vaccination is recommended by the government, the government should be strictly liable in tort for serious and lasting damage suffered by anyone, whether adult or child, as a result of vaccination recommended in the community's interest.Footnote 137 While such a recommendation may seem entirely justifiable over 40 years later, this preferential treatment of vaccine damaged persons over other disabled children was questioned by commentators at the time and continues to be regarded by some as controversial.Footnote 138 It also sits uneasily with the report’s statement that the compensation and care of severely handicapped children was based on the principle that they were to be treated alike, without regard to the cause of their condition,Footnote 139 an ‘anomaly’ said to have been agreed ‘on the basis of the specific public health issues involved’.Footnote 140 Strict liability was to be subject to matters of cause and fact and without defences. Proof of causation was acknowledged as a longstanding difficult issue for the resolution of the courts since convulsions which may be symptomatic of whooping cough vaccine could also occur naturallyFootnote 141 and the Commission was aware of ‘no clinical tests which could distinguish the one from the other’.Footnote 142

(ii) Scope of the 1979 Act

On the recommendations of the Pearson Commission, and to restore the public's confidence in the vaccination programme,Footnote 143 the Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979 was enacted ‘to provide a single tax-free payment’Footnote 144 for vaccine-damaged persons for death or severe disablementFootnote 145 proved on a balance of probabilities to have been causedFootnote 146 by vaccination against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, poliomyelitis, measles, rubella, tuberculosis, smallpox, and any other disease specified by the Secretary of State by statutory instrument.Footnote 147 This became known as the Vaccine Damage Payments Scheme (VDPS). Over the years, several additional diseases have been specified, viz mumps, the haemophilus influenza type b infection (Hib), meningococcal Group C (meningitis C), pneumococcal infection and the human papillomavirus (HPV), pandemic influenza A (H1N1) to 31 August 2010,Footnote 148 rotavirus, influenza,Footnote 149 meningitis W and meningitis B.Footnote 150 The latest additional disease specified is Covid-19Footnote 151 and, as with H1N1, the conditions of entitlement have been modified to extend the 1979 Act to those vaccinated against the Covid-19 virus at a time when they were 18 years or older.Footnote 152 The Secretary of State must be satisfied that a person was severely disabled as a result of vaccine damage, determined on the balance of probability.Footnote 153 If a causal link is established and disablement suffered is 60% (previously 80%) or more,Footnote 154 a lump sum of £120,000 is awarded.Footnote 155 In assessing whether the threshold is crossed for 60% disablement, it has been held in a significant breakthrough for applicants under the VDPS that a Tribunal should take into account an applicant's future prognosis on the balance of probabilities.Footnote 156 In G (A Minor) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions,Footnote 157 which concerned the H1N1 swine flu vaccine, the Court of Appeal upheld the decision of the First-tier Tribunal that, notwithstanding the applicant did not cross the 60% disablement threshold as assessed solely at the date of the DWP decision refusing to accept severe disablement, further continuing disablement in the future was likely and should be taken into account: accordingly, the applicant was entitled to payment under the scheme.Footnote 158

(iii) Claims experience

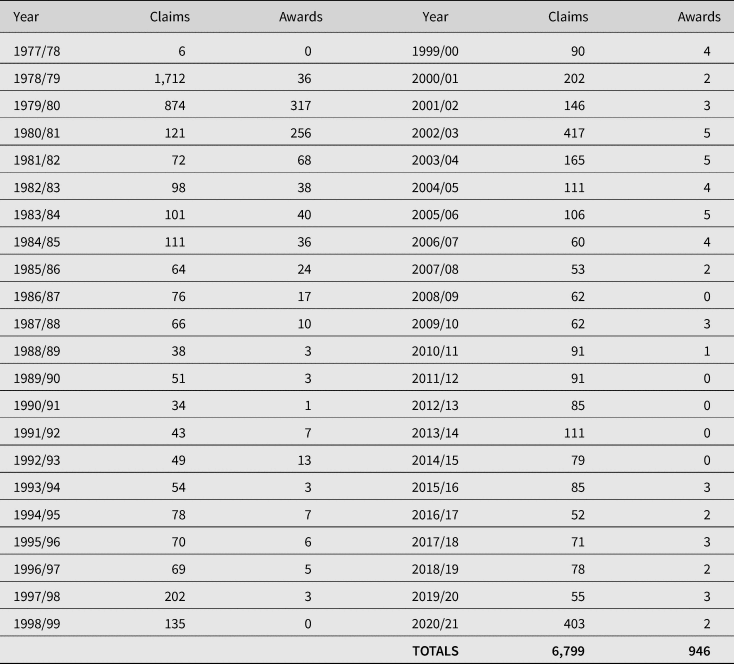

In contrast to the US VICP, success rates are extremely low: since the inception of the VDPS, there have been 6,799 claims, 946 of which have resulted in awards: a success rate of 13.9% (see Table 2). The number of accepted claims reached its height between 1979 and 1983 and has reduced to an average of 1.6 claims a year between 2010 and 26 August 2021.

Table 2. Total number of VDPS claims and awards between 1977 and 26 August 2021

Source: Department of Work and Pensions, FOI2020/76078, 11 December 2020; FOI2021/03388, 1 February 2021; FOI2021/61679 27 August 2021.

By far the majority of claims to the VDPS that have been disallowed were on the basis that the vaccination did not cause the disability (a total of 4,349 claims, amounting to 79%). The other main reason for rejection was that claims were received outside the statutory time limit for making a claim,Footnote 159 with 629 rejected for that reason. Table 3 shows a breakdown of the claims that have been disallowed and the reason for the disallowance.

Table 3. Total numbers of VDPS claims disallowed and reasons for disallowance up to 26 August 2021

Source: Department of Work and Pensions: FOI2020/76078, 11 December 2020; FOI2021/03388, 1 February 2021; FOI2021/61679 27 August 2021.

The scheme is without prejudice to the ability to pursue the alternative course of claiming compensation against the manufacturer of the vaccine in any civil proceedings in respect of disablement suffered, but in such proceedings any payment madeFootnote 160 is to be treated as being paid on account of any damages which the court may award for a disablement.Footnote 161 However, litigation remains a course attended by considerable difficulty.Footnote 162

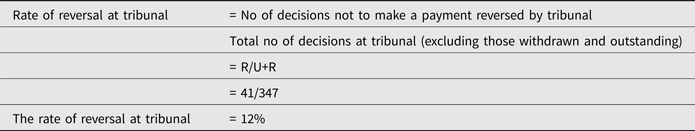

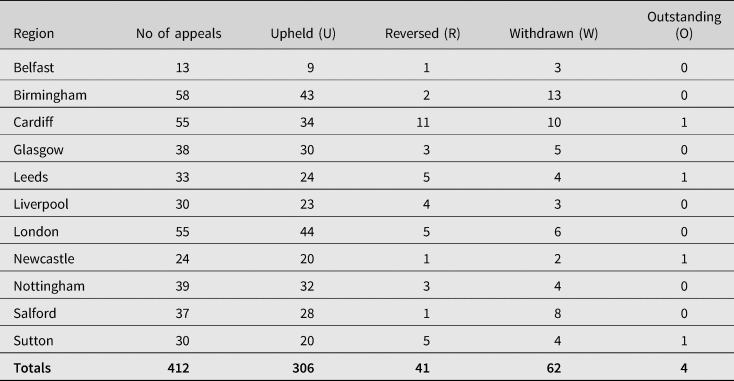

(iv) Tribunal appeals

Section 4(1) of the 1979 Act provides for appeal against any decision as to whether a person was severely disabled as a result of vaccination by reference to a First-tier Tribunal. In deciding an appeal, the Tribunal shall consider all the circumstances of the case (including any that did not obtain at the time when the decision appealed against was made).Footnote 163 The failure rates continue to be high. Since the inception of the VDPS, 2111 requests have been made for an appeal. Of those, 1402 were upheld, 502 were reversed, 203 were withdrawn and 4 remain outstanding.Footnote 164 Table 4 provides an analysis of the most recent decisions of the Vaccine Damage Payments Tribunals in the years 1993–2021.Footnote 165 On the basis that:

Table 4. Decisions of Vaccine Damage Payments Tribunal appeals by region, 1993–2021

Source: Department of Work and Pensions: FOI2021/03388, 1 February 2021. FOI2021/61679 27 August 2021

The determination of causation continues to be a major source of difficulty in Tribunal appeals. The matter is not helped by the fact that, unlike decisions of the VICP, where all decisions issued by the special masters are published (with appropriate redactions to protect private medical information concerning the petitioners),Footnote 166 the UK Vaccine Damage Payments Tribunal decisions remain unpublished.Footnote 167 In response to a request made by the author to obtain copies of the decisions, the author was informed that the DWP were unable to provide them.Footnote 168 It is, therefore, impossible for the public and commentators to discern the reasoning behind the decisions made. Moreover, this does not help to generate any consistency in decision making, and the lack of transparency is unhelpful in the face of increasing vaccine hesitancy.

(v) Concerns over causation: use of biologically plausible theories unsupported by scientific evidence

A recent decision made by the Vaccine Damage Payments Tribunal raises concerns about determining the causation issue in favour of applicants, despite the absence of independent evidence supporting a causal association. This redacted First-tier Tribunal decision found that on a balance of probabilities vaccination with Fluenz Tetra (a seasonal flu vaccination) caused the daughter of the appellant to suffer narcolepsy between three and four months later, on the basis of a biologically plausible theory that was unsupported by scientific evidence.Footnote 169 While there is compelling epidemiological evidence of an increased risk of narcolepsy following vaccination with the H1N1 pandemic vaccine Pandemrix, especially in children, Footnote 170 and the Vaccine Damage Unit and the Secretary of State have previously accepted a causal link between the development of narcolepsy and Pandemrix,Footnote 171 there is an absence of any epidemiological study supporting an increased risk of narcolepsy following vaccination with Fluenz Tetra. The Secretary of State's four assessors relied on the absence of any such study to advise that the narcolepsy was not caused by the vaccine.Footnote 172 The Tribunal Judge ruled that the absence of an epidemiological study showing any causal link between the Fluenz tetra vaccine and narcolepsy did not render proof of causation fatal: in the Tribunal's view this was ‘evidentially neutral’.Footnote 173 As we have previously noted from the decisions on the VICP, the absence of epidemiological evidence in itself is not fatal.Footnote 174 However, the Tribunal relied on the appellant's expert report which invoked an argument of molecular mimicry extrapolated from Pandemrix to Fluenz Tetra, in support of a biologically plausible mechanism in favour of establishing narcolepsy on a balance of probabilities.Footnote 175 Again, the invocation of such an argument is not unreasonable, provided it is supported by scientific evidence. In this case, however, the appellant's claim about molecular mimicry was not supported by any biological or epidemiological evidence. In the case of the proven increased risk of narcolepsy after Pandemrix, there is some evidence in support of molecular mimicry as a potential causal pathway.Footnote 176 Nevertheless, the molecular mimicry argument collapses when extrapolating it to Fluenz Tetra as the increased risk of narcolepsy was shown to be specific to Pandemrix and was not observed after vaccination with other pandemic vaccines containing the same H1N1 influenza antigen that was in Pandemrix (as well as in Fluenza Tetra). An association with other pandemic vaccines was looked for in epidemiological studies but was not found. Accordingly, while there is some evidence for the molecular mimicry argument, this appears to be specific to Pandemrix and possibly is related to the way the antigen was prepared for that particular vaccine or its co-administration with a powerful adjuvant that stimulates the immune system.Footnote 177 The Tribunal's ruling is flawed on several levels, all of which indicate it was not scientifically sound. General causation was not satisfied: there is no evidence that Fluenz Tetra can cause narcolepsy. The molecular mimicry argument is unsound as it is specific to Pandemrix. Secondly, on the specific causation issue, the Tribunal held that proof on a balance of probabilities was established by reference to the existence of a temporal sequence (ie vaccination then onset of narcolepsy within 3–4 months) and the absence of another ‘trigger’,Footnote 178 yet this has no probative value. At least one new case of narcolepsy occurs each year in every 100,000 children, and most have no obvious trigger.Footnote 179

Since Fluenz Tetra is offered to all schoolchildren (under 13 years of age)Footnote 180 other temporally associated cases may arise in the future and this decision may well set an unhelpful precedent in increasing vaccine hesitancy.

(b) Covid-19 vaccines and the 1979 Act

The decision to extend the 1979 Act to those vaccinated against the Covid-19 virus is clearly correct. To have not done so could have had an effect on vaccine confidence by a failure to treat Covid-19 vaccines in the same way as other national vaccine programmes.Footnote 181 It is arguable that this has come at the expense of any attempt to address the need for changes to the scheme, particularly in the way the VDPS determines causation, which appears by no means clear or consistent,Footnote 182 and the Act's requirement of serious disability is a high hurdle to overcome. However, broader changes to the scheme would take time to agree and implement and there has been no appetite for such change from successive governments.Footnote 183 Nonetheless, the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines has now refocused attention on this scheme, access to which will be important given the difficulties in establishing strict liability under the Consumer Protection Act 1987.Footnote 184 An impact assessment of the effect of adding Covid-19 to the list of specified diseases covered by the VDPS on the costs of business, the voluntary sector and the public sector estimated that total payments to the public could range from £0 in the scenario where there are no successful VDPS claims, between £3.2 million to £13.2 million in scenarios where there are successful claims from one round of vaccination and £63.2m in the scenario with future rounds of vaccination.Footnote 185 Given that VDPS is managing about 76 claims a year, claims are likely to increase to an estimated 230–670 per year, ie a three- to nine-fold increase in claims, even if ultimately none is successful.Footnote 186 As of 26 August 2021, 260 claims had been been received by the Vaccine Damage Payments Unit in respect of vaccination against Covid-19.Footnote 187 This will result in an increasing workload for the Vaccine Damage Payments Unit and will probably lead to large increases in administrative costs. In addition, increasing number of claims is likely to result in a corresponding increase in the number of appeals.Footnote 188

Whilst it has been argued that a bespoke Covid-19 vaccines compensation system should be introduced in the UK,Footnote 189 it is submitted that there are no justifiable reasons for treating Covid-19 vaccines differently from any others. First, while there has been use of a rapid approval process resulting in temporary authorisations for the Covid-19 vaccines as opposed to the usual granting of a product licence for a vaccine, that has not compromised the safety of any of the vaccines to merit a distinction in treatment. As a result of a ‘rolling review’ of data, the Medicines and Health Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) concluded, on the advice of the Commission on Human Medicines, that all three Covid-19 vaccines in use in the UK had sufficiently strong evidence of safety, quality and effectiveness from clinical trials to authorise their supply. Notwithstanding these approvals being rapid, the MHRA Chief Executive has confirmed that ‘no corners have been cut’:Footnote 190 temporary authorisations were only granted in the light of a ‘rigorous scientific assessment of all the available evidence of quality, safety and effectiveness’.Footnote 191 Data now published from the MHRA have confirmed that the approved vaccines meet strict regulatory standards for safety.Footnote 192

Secondly, the provision of an ad hoc preferential bespoke compensation scheme for Covid-19 vaccines, while other vaccines remain within the ambit of the VDPS, would create a hierarchy in the importance of vaccines, which would undermine the effectiveness of the UK vaccination programme and, in so doing, generate vaccine hesitancy. Whilst the global size of the pandemic is unprecedented in modern times, Covid-19 will become a vaccine-preventable disease in the same way as the other 28 diseases for which vaccines are available.Footnote 193 From a fairness perspective, compensation for Covid-19 vaccines should be no different from compensation for measles or any other disease prescribed by the Secretary of State. The previously discussed US experience of the Swine Flu Act of 1976, which led to increasing governmental reluctance to assume financial risks with vaccination programs in the absence of scientific evidence of causation, is a salutary reminder of the dangers of an ad hoc overly preferential system directed to one set of vaccines. A much fairer proposal is for countries like the UK with existing no-fault schemes to incorporate Covid-19 into their programmes,Footnote 194 with any legislative improvements in these schemes applying to all covered vaccines. However, with its consistently low success rates, and the impact of the extension of the 1979 Act to those vaccinated against the Covid-19 virus still to emerge, especially in the case of children and young people aged 12–15,Footnote 195 the UK VDPS is clearly not fit for purpose and needs radical reform.

3. Reform: towards a revised national vaccine policy in the light of Covid-19

This paper favours the re-examination of the distribution of liability for vaccine-related injuries in both the US and UK within the context of a revised national vaccine policy in both countries.Footnote 196 The revised national vaccine policies must take into consideration their respective current and long-term national vaccine strategies to prepare for future pandemics. Improvements to both the US and UK schemes must be consistent with the following principles.Footnote 197 First, they must promote public health by incentivising innovation into the design of new vaccines. Secondly, a fair scheme of protection must be provided for those who suffer vaccine-related injuries, whilst also encouraging public confidence in vaccines through transparent decision-making, which is soundly based on scientific evidence.

(a) Reforms to VICP

In the US, as far as reforms to the VICP are concerned, it is submitted that any changes must be viewed in the light of the Biden Administration's Covid-19 vaccination strategy of January 2021. This strategy aims to ensure the availability of safe and effective coronavirus vaccines for the American public, as well to build public trust through a vaccination public health education campaign.Footnote 198 Reforms must also take into consideration the long-term national vaccine strategy of the US to prepare for future pandemics. A national vaccine policy that adopts the overriding recommendation of Van Tassel et al that Congress should amend the PREP Act by requiring all vaccines recommended by the CDC to ameliorate a public health emergency to be immediately added to the VICP, regardless of whether they are recommended for pregnant women or children, is prima facie compelling.Footnote 199 However, this is likely to run up against powerful Congressional opposition, given the arguments of manufacturers in favour of the broad protection given by the PREP Act. As Kirkland has observed, the difficulty of getting anything though Congress, ‘let alone small a relatively set of reforms’Footnote 200 to the vaccine court, remains a considerable obstacle. Inclusion of all such vaccines into the VICP might only be accepted by Congress with a further quid pro quo in favour of scientific rigour in determining causation. A concession that the programme should now define fair but rigorous criteria used to determine causation on a balance of probabilities to ensure public confidence in the science behind vaccination seems a necessary counterweight to the expansion of the VICP to cover pandemic vaccines.

(b) Reforms to VDPS

Any reforms to the UK scheme should be included in a revised national vaccine policy as a part of the Department of Health and Social Care's ongoing 10-year vaccination strategy,Footnote 201 including the long-term vaccine strategy to prepare the UK for future pandemics, established by the UK Government's Vaccine Task Force (VTF).Footnote 202 A UK-wide national vaccine programme, similar to that in the US, should be administered by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care with the aim of optimal prevention of human infectious diseases through vaccination and immunisation and to achieve optimal prevention against adverse reactions to vaccines.Footnote 203 The director of the programme would be required to coordinate vaccine research and development, and coordinate direction for safety and efficacy testing of vaccines carried out through the MHRA.Footnote 204

The programme should introduce a statutory requirement for the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to review periodically, but least every three years, the current medical and scientific evidence on vaccines and vaccine adverse events by an expert advisory group of the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM).Footnote 205 The current VDPS should be reformulated as a Vaccine Damage Compensation Programme. A rigorous review of the current medical and scientific evidence on vaccines and vaccine adverse events by the CHM expert advisory groupFootnote 206 will be needed, in order to generate a vaccine damage claims Table akin to that in the US under NVIA. All claims must be assessed in accordance with this evidence. Claims should continue to be brought in the Vaccine Damage Tribunal, but with specialist docketed tribunal judges appointed to deal with vaccine cases.

Learning from previous controversies, the programme must define stringent criteria to determine causation on a balance of probabilities.Footnote 207 This will reflect the need to give sufficient weight to scientific evidence, utilising hierarchies of evidence for vaccine injury. The presence of specialist tribunal judges will reflect the need for increased judicial expertise and training used in scientific evidence with the assistance of tribunal appointed experts (if necessary). It is submitted that greater clarity in the use of scientific evidence in determining causation should help to restore the public's confidence in the uptake of vaccines.

To balance the need for rigorous criteria to determine causation with a fair scheme, the programme should adopt the US practice of allowing negotiated settlements between the parties, where the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care's review of the evidence has not concluded that the vaccine(s) caused the alleged injury but where there are close calls concerning causation.Footnote 208 Secondly, more generous levels of compensation awards should be available. In the light of the range of severity of disablement, the current single lump sum approach should be abandoned, and damages should be awarded in accordance with the Judicial College Guidelines for the Assessment of General Damages in Personal Injury Cases to reflect the severity of disablement in each case.Footnote 209 Loss of future earnings as well as the costs of future medical care should also be available to claimants. While a right to claim compensation in the civil courts should be permitted, every claim must commence in the tribunal and any payment made by the tribunal should continue to be treated as a payment on account and deducted from any future award.Footnote 210 To generate increased confidence and transparency, all decisions on whether to award compensation or not should be published with any necessary redactions, including the reasons for the award and demonstrate clear communication on any issues of scientific evidence.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to reappraise the vaccine compensation schemes currently available in the US and UK in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Despite controversies concerning the perception of an adversarial environment, due to the heavy onus on petitioners to show that a covered vaccine caused the injury when there are no associated injuries on the Table, there is much to be said for the success of the US VICP. In particular, the vaccine court has helped to uphold the ‘immunization social order’ through its gatekeeping mission of keeping lawsuits out of the tort system, its role as both an audience and an engine for scientific evidence, and its expression of society's ethical obligations to injured vaccinees.Footnote 211

This paper supports the view that giving epidemiological evidence appropriate weight, along with the other evidence of the record, has reduced the dangers of elevating lower ranking hierarchical evidence of biologically plausible mechanisms to connect vaccines to adverse events over published contrary epidemiological studies. For the continued effectiveness of the VICP, it must be seen to be part of a national vaccine policy that encourages public confidence in vaccines through transparent decision-making, while being soundly based on scientific evidence.

The controversial role of the PREP Act, offering ‘targeted liability protection’Footnote 212 to the manufacturers of drugs, vaccines and medical devices used in declared public health emergencies, was examined. The decision to place Covid-19 vaccine claims for compensation within the CICP has been highly criticised, given the broad immunity and limitations on compensation established by the PREP Act. Despite the legitimate argument of manufacturers in favour of broad protection, given the expectation of government and the public that manufacturers develop and manufacture such vaccines as quickly as possible, the arguments in favour of inclusion of coronavirus vaccines in the VICP (especially the societal benefits through individual vaccination) are strong.

The enacting of the Vaccine Damage Payments Act 1979 in the UK to restore the public's confidence in its vaccination programme has revealed a contrasting claims experience under the VDPS to that of the US VICP. Success rates are extremely low. By far the majority of claims to the VDPS have been disallowed on the basis that the vaccination did not cause the disability and determination of causation continues to be a major source of difficulty in Tribunal appeals. The decision to extend the 1979 Act to those vaccinated against the Covid-19 virus is clearly correct on vaccine confidence grounds. However, this has come at the expense of any attempt to address the need for changes to the scheme, particularly in the way the VDPS determines causation, which appears by no means clear or consistent.

It has been argued that any improvements to the UK VDPS should be included in a revised national vaccine policy as a part of the Department of Health and Social Care's ongoing 10-year vaccination strategy. Again, as with the US scheme, this policy must promote public health by incentivising innovation into the design of new vaccines, whilst encouraging public confidence in vaccines through transparent decision-making based soundly on scientific evidence. A UK-wide National Vaccine Injury Compensation Programme, similar to that which exists in the US, should be administered by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Learning from previous vaccine controversies over causation, the programme must define rigorous criteria to determine causation on a balance of probabilities. To balance the need for these rigorous criteria with the need for fairness, the programme should adopt the US practice of allowing negotiated settlements between the parties, where the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care's review of the evidence has not concluded that the vaccine(s) caused the alleged injury but where there are nonetheless close calls concerning causation.

Including these improvements to both the UK and US schemes within their revised national vaccine policies will help to create long-term vaccine strategies to prepare for future pandemics and other illnesses, from the research, development, manufacture and distribution of vaccines through to liability and compensation for those injured by them. In so doing, such changes should help to restore public confidence in the uptake of vaccines, which has been seen as a crucial tool in reducing the threat of vaccine hesitancy.