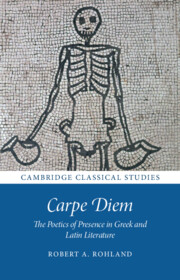

This chapter begins where the previous one left off. Horace’s choice of words emerged as something noteworthy where his treatment of wine is concerned: old wines frequently bring the taste of old words to the banquet. In the present chapter, I consider how words can evoke the present rather than the past. Horace’s carpe diem poems thematise present moments, and I will show that within the underlying architecture of a poem even the smallest elements and mosaic pieces, that is, the individual words, contribute to creating a poetry of the present. I am, of course, alluding to Nietzsche’s well-known saying, according to which Horace’s poems are a ‘mosaic of words, in which every unit spreads its power to the left and to the right over the whole, by its sound, by its place in the sentence, and by its meaning’.Footnote 1 My interest in this chapter lies in such mosaic pieces and what they can tell us about the mosaic as a whole.

Horace’s choice of words was already much-admired in antiquity: Petronius spoke of Horatii curiosa felicitas (‘Horace’s painstaking felicity’, Petron. 118.5) and Quintilian characterised him as uerbis felicissime audax (‘fortuitously bold with his words’, Inst. 10.96). Horace’s phrasing seems strikingly felicitous to ancients and moderns alike (and in turn the phrases of Nietzsche, Petronius, and Quintilian are at least felicitous enough that they will be quoted in any discussion of Horace’s choice of words). In this chapter, I will argue that Horace’s words are not felicitous for their own sake but underline the message of carpe diem poems by producing effects of presence. ‘Producing effects of presence’ may look like an ironically anachronistic term in a discussion about ancient choice of words. Yet, I will show that there exists a good Horatian model for this expression. What I mean by ‘producing presence’ is that certain words in Horace’s odes evoke the momentary present in which they are set.Footnote 2 I will analyse Horace’s thoughts about choice of words in his literary epistles as well as his actual choice of words in some carpe diem poems.

The chapter has three sections. In the first section, I will look at a well-known passage from Horace’s Ars Poetica which compares words to leaves, in that they become extinct and return again. I will show that Horace’s choice of words as well as his treatment of the carpe diem motif obeys a principle of cyclical change. In the second part, I will look at Horace’s treatment of choice of words in the Ars beyond the leaves simile; while his thoughts engage with the linguistic theories of contemporaneous thinkers, his emphasis on cyclicality is unique to him. In the third part, I will show how Horace puts his theory into practice: in several carpe diem poems, certain words evoke the present time.

3.1 Words That Are Green Turn to Brown: Words and Leaves in the Ars Poetica

In the Ars Poetica, Horace discusses, among other things, a poet’s choice of words and also how the vocabulary of a language changes over time. The passage in which he does this is generally admired. Brink called it ‘perhaps the most remarkable piece of the Ars’,Footnote 3 and it is arguably the passage that best defies Scaliger’s damning verdict on the work, ‘de arte sine arte tradita’.Footnote 4 In this passage, Horace compares a language’s linguistic development to leaves falling from a tree. While some words disappear from usage, old ones return (Ars 60–72):Footnote 5

60 pronos] priuos Bentley fortasse recte61 lac. ind. Ribbeck prima cadunt] priuanturque Delz : particulatim Nisbet68 facta] cuncta ϛ : saecla Peerlkamp69 nedum sermonum] sermonum haud Aldus

As trees with their leaves change their appearance as the years slide on, the first leaves fall * * * * * * * * * * * * *, so the old generation of words dies and words that were just born bloom and flourish like young men. We and what is ours are owed to death; whether Neptune’s water is made a basin and protects fleets from the North Wind – an achievement worthy of a king – or a swamp, which had long been barren and usable only for boats, now feels the heavy plough and nourishes neighbouring towns, or a river that had harmed the crops learns better ways and changes its course – still, all mortal works will perish, and still less is it true that the prestige and charm of speech could stay alive. Many words that have already fallen out of usage will be reborn, and many words which now have prestige will fall out of usage if convention wants it. Because in the hands of convention lie judgement, authority, and rule of speech.

Horace describes with gentle melancholy the lexical development of language as he likens words to leaves on a tree. Language, humans, and all their possessions are subject to an eternal cycle of death and rebirth. Commentators have noted the unusual tone of the passage. Thus, Brink discerns the ‘lyric intensity of the Odes (say, C. I. 4 or IV. 7)’, and Rudd speaks of ‘sombre lyrical resonances’.Footnote 6 In the pages that follow, I wish to show that this similarity is not merely superficial; rather, the same concept of time that informs the content of Horace’s lyric poetry also informs his thoughts on lexical change.Footnote 7

The simile of the leaves goes back, of course, to Homer’s Iliad, where Glaucus meets Diomedes on the battlefield before Troy and compares generations of men to generations of leaves (6.145–9):Footnote 8

Great-hearted son of Tydeus, why are you asking about my ancestry? Just as there are generations of leaves, so there are also generations of men. The wind sheds some leaves to the ground, but the flourishing forest brings forth others when the season of spring is there. So it is also with the generations of men; one generation sprouts, but another passes away.

The Homeric passage can shed some light on a textual issue in Horace’s Ars. Horace’s version includes the first part of the Homeric simile (φύλλα τὰ μέν τ’ ἄνεμος χαμάδις χέει ∼ prima cadunt), but lacks the second part of the simile (ἄλλα δέ […]). If we assume that Horace modelled the passage on Homer, this lends further support to Ribbeck’s diagnosis of a lacuna in line 61. For Ribbeck had noted that the paradosis of Horace’s simile illogically compares one thing in the source domain with two things in the target domain: as leaves fall, so do words fall out of usage and new ones come about.Footnote 9

Horace was neither the first nor the last to pluck Homer’s leaves. Indeed, even in Homer the simile of the leaves has the appearance of a set piece, as ancients and moderns alike have noted. Thus, ancients claimed that Homer took these lines from Musaeus (fr. 5 DK), while some modern scholars also thought that Homer’s simile was not well integrated.Footnote 10 Be that as it may, already in Homer the leaves grow again elsewhere, when Apollo describes the generations of men with the same simile (Il. 21.461–7). The self-reference in Homer anticipates the many later adoptions of these lines. Lyric poets in particular were fond of quoting them or alluding to them. What arguably facilitated this lyric appropriation is that the lines already had the appearance of lyric poetry in Homer. Hayden Pelliccia has argued in detail that the leaves simile constitutes a rhetorical device, which the ancients called εἰκάζειν: a rhetorical tool of caricaturing someone by using a comparison, which was a popular game at symposia.Footnote 11 Pelliccia says that through the usage of the εἰκάζειν Glaucus ‘is identifying himself as a member of symposiastic society, and indeed as an adept of the art of conversational “warfare”’.Footnote 12 I doubt that we can go that far. There may have been (proto)symposiasts before Homer, but they lie unknown, overwhelmed by perpetual night, since they lack a sacred bard.Footnote 13 In other words, Pelliccia’s characterisation of Glaucus as a symposiast is arguably anachronistic. But Greek lyric poets might have looked at the passage in the same manner; to them, too, Glaucus seemed to engage in sympotic banter, and they appropriated the passage accordingly. The leaves of Omero lirico would find their appropriate(d) generic place in the lyric carpe diem poems of Mimnermus and Simonides in particular, and this Nachleben of the Homeric passage is most crucial for the simile’s function in Horace:Footnote 14 Horace underlines his principle of word-change with a simile that itself has been reborn again and again and acquired new meaning along the way.

In Horace’s Ars, the leaves simile is directly followed by a gnome, which alleges that everything is owed to death (63): debemur morti nos nostraque. It has long been recognised that this is a translation of a ‘Simonidean’ epigram, and that the reference to Simonides here suggests that Horace plucked Homer’s leaves from Simonides’ tree.Footnote 15 For Simonides quotes and explains the Homeric image in a carpe diem poem (frr. 19 + 20):Footnote 16

fr. 19 (Stob. 4.34.28)

fr. 20 (P.Oxy. 3965 fr. 26 with Stob. 4.34.28 for lines 5–12)

One of the sayings of the man from Chios is the best: ‘Just as there are generations of leaves, so there are also generations of men.’ Few of the mortals who have heard this take it to heart. For all men have expectations which in their youth sprout in their hearts.

[…] for a short time […] remain […] As long as a mortal enjoys the lovely bloom of youth he is light-hearted and devises many things that are impossible to accomplish. For he does not expect to grow old nor to die, and he doesn’t think of illnesses when he is healthy. People are fools who think like this and don’t know that mortals have a short time of youth and life. But now that you have learned this at the end of your life, endure and pamper your soul with good things. […] Consider [the account of the man] of old. Homer escaped [the oblivion] of his words. […] false […] in feasts […] well-plaited […] here and […].

Horace’s application of the leaves simile to words is daring. But David Sider has shown that Horace may develop a thought of Simonides, who already included poetry in his thoughts on mortality and leaves. For Simonides seems to say that Homer’s language escaped oblivion (20.14).Footnote 17 There is another aspect of Simonides’ poem which makes it particularly apt for Horace’s purpose in the Ars. Richard Rawles recently noted that Simonides uses a high number of archaisms in his poem, that is, he uses a number of expressions which were common in the early Greek hexameter poetry of Homer, Hesiod, and the Homeric Hymns, or in the early elegy of Mimnermus, Theognis, and others, but which were no longer common at the time Simonides was writing, in the fifth century bc.Footnote 18 Of course, these expressions naturally come with the Homeric quotation: once Homer’s seeds are planted, their leaves sprout throughout the poem. Simonides thus describes youth metaphorically as a ‘flower’ (20.5: ἄνθος), originally a Homeric expression he had plucked from early poetry, perhaps from Mimnermus’ poem on the leaves (fr. 2.3).Footnote 19 Homer’s language, his γλώσση (20.14), thus does not die: bits, many bits of Homer dodged all funeral. Simonides preserves certain Homeric expressions as well as a whole hexameter. But Homer’s words have acquired a new context: they are reborn like leaves and now grow on a lyric tree.

It is suggestive that Simonides already made ample use of archaisms in his adaption of Homer’s leaves, before Horace in turn would make this simile all about old words that become new again. It is, of course, not certain how many of Simonides’ archaisms would have been readily identifiable as such in first-century-bc Rome, but the cumulative force of the evidence surely matters: on the grounds of its content as well as of its expressions, Simonides’ poem has the appearance of early poetry.

In Simonides, the archaic words underline the poem’s message, which tells its listeners to enjoy the present. Homer’s old words survived for centuries and escaped oblivion (or whatever else the supplement in 20.14 might be), while human beings live only for a short time and should enjoy the present. Horace seems to go a step further. In his account, words are anything but permanent. Words have their seasons. In the Ars, language is a consequence of the cyclical change of time and the poet is subject to this change: he chooses his words from a set of current vocabulary, just as he chooses the present moment as a time of merriment. Yet, he also knows that both the present moment and language will change. Horace’s carpe diem poems are thus works of cyclical time, both in their subject matter and in their theoretical linguistic framework: the cyclical time that is their theme in the description of the seasons is reflected in their vocabulary.

In the Ars, Horace’s poetry shows some self-awareness of the fleeting, momentary and present nature of its words. Horace’s poetry presents a combination of words that can only be fully enjoyed in the present moment, his lifetime, as some words will become extinct later, some will be reused again, and so on. What emerges, then, in Horace is a new poetry of the present moment. While Greek lyric poems were seemingly poems of the present moment by virtue of their occasional nature and their performance in the present, this quality of lyric is lost in Horace’s book poetry.Footnote 20 Yet, this is supplanted by a linguistic present. Indeed, elsewhere Horace seems to characterise his lyric by its bold and novel choice of words. In the Epistles, Horace proudly states his achievement that he was the first who popularised Alcaeus’ lyric song in the Latin tongue (Epist. 1.19.26–34); he brought ‘things untold before’ (inmemorata) to the Romans. Horace’s word-choice, inmemorata, neatly underlines the content: just like his lyric, the word itself had been untold before. It is Horace’s own coinage, though it is drawn from a Greek source.Footnote 21 Both Horace’s lyric and his words are strikingly new and yet a repetition of older material.

An ode of Horace becomes the linguistic equivalent to a winter evening at the foot of Mount Soracte: a moment in linguistic time, which is subjected to seasonal word change and therefore can only be fully appreciated in the present. In the future some words will fall out of use, others reappear, and their specific timely quality as neologisms or archaisms will no longer be naturally understood, until philologists gather again the fallen leaves.

3.2 A Linguistic Turn Around and Around: Horace on Semantic Change

Horace’s thoughts on lexical development are highly idiosyncratic; they seem to differ from any notable ancient or modern theory that deals with this matter. Neither Aristotle, nor Varro, nor Caesar, nor Cicero thought that lexical development happened in a cyclical fashion. Ancients were aware of linguistic change over time, but they regarded this as a linear development, and so do modern linguists.Footnote 22 Indeed, at first sight one may be tempted to dismiss Horace’s thoughts as too bizarre to be taken seriously, or one might argue that Horace’s prime interest lies in the beauty of the simile of the leaves rather than in linguistic reflections. Yet, I maintain that we should be attentive to Horace’s idiosyncratic thoughts in this passage. For if we are attentive, the passage can tell us a lot about Horace’s understanding of his own poetry. Even taken at face value, Horace’s theory is perhaps not quite as absurd as it may first seem. A significant number of Latin words, which are found in Plautus and Terence, do not then appear in classical Latin, but are present again in late Latin. Such words, Giuseppe Pezzini says, reappeared in Latin through ‘revival, recoinage, and reborrowing (normally from Greek)’.Footnote 23 This sounds strikingly similar to Horace’s ideas of words that are ‘revived’ (renascentur) or that should come ‘from a Greek source’ (Graeco fonte). And the metaphor of word-‘coinage’ seems to have been coined by Horace anyway (Ars 58–9). Of course, Horace could not have known of the linguistic phenomenon that Pezzini describes, but his linguistic reflections are at least not completely absurd. Perhaps more to the point, Aulus Gellius argues in the second century ᴀᴅ that archaisms and neologisms are essentially the same thing, since old, uncommon words have the appearance of neologisms when they appear in modern diction (11.7.2): noua autem uideri dico etiam ea quae sunt inusitata et desita, tametsi sunt uetusta (‘but I maintain that even these words can seem like new [∽neologisms] which have been out of use and have become obsolete, although they are in fact old words [∽archaisms]’). To be sure, Gellius does not sign up to a universal principle of cyclical lexical change, and he goes on to ridicule the habit of some parvenus who use odd archaisms. Nonetheless, it seems that antiquarians took Horace’s linguistic thoughts at least to some extent seriously.

Numerous ancient writers besides Horace have considered the subject of choice of words. Horace thus naturally shares some of his categories and terminologies with these other writers. Yet, this should not blind us to the originality and singularity of his thoughts. Though Aristotle discusses the different quality of words, though Cicero speaks of archaisms, neologisms, and metaphors in his discussion of choice of words, and though Varro even compares the appearance and extinction of words to the generations of men,Footnote 24 nonetheless, Horace’s key idea of lexical cyclicality does not appear in earlier writers. Thus, Varro strongly denies that old words can reappear (L. 5.5): quare illa [sc. uerba] quae iam maioribus nostris ademit obliuio, fugitiua secuta sedulitas Muci et Bruti retrahere nequit (‘therefore when words were already obsolete in the days of our ancestors, their meaning escapes even the diligence of Mucius and Brutus, who cannot capture their nuances though they pursue the matter’).Footnote 25

Horace’s linguistic thoughts may even still appear original when we compare them to the theory that is closest to them: Epicurean linguistic thought. Philip Hardie has analysed numerous allusions to the Epicurean poet Lucretius in Horace’s lines on choice of words.Footnote 26 Lucretius famously wrestled with the poverty of the Latin language (patrii sermonis egestas at Lucr. 1.832, 3.260; cf. 1.139) and coined numerous new words in his struggle. Allusions to Lucretius are thus highly appropriate when Horace faces similar issues in the Ars. The question remains, though, whether the affinity goes further and Horace actually signs up to an Epicurean understanding of linguistics. Some scholars think so, and argue that Horace as well as the Epicureans Philodemus and Lucretius consider letters to be ‘semi-animate entities with a strange faculty of forming realities of their own’ – just like atoms.Footnote 27 Such a theory would be an ingenious explanation for Horace’s claim that language is eternal, yet its components, words, are continuously changed. Cyclicality, however, has no place in Epicurean linguistics, but is crucial to Horace’s thoughts.Footnote 28 Thus, Horace could have justly said about his linguistic thoughts that in this realm, too, he was the first to plant his footsteps in the void.

The following section immediately precedes the simile of the leaves in the Ars and sets out Horace’s thoughts on choice of words in some more detail (45–59):Footnote 29

46 ante 45 transpos. ed. Britannici 1516 : post 45 codd.49 rerum B C K R : rerum et a Ψ V σχ59 producere nomen] procudere Aldus nummum Luisinus

When it comes to stringing words together delicately and carefully, the endeavouring poet should be choosy and embrace one word but ignore another. It is a sign of a distinguished stylist if an ingenious collocation (callida iunctura) makes a familiar word new. If it is necessary to explain obscurities with new signifiers, you will have the chance to invent new words which the kilted Cethegi of old had never heard – and you will be granted the right to do so if you make modest use of it. New words that have just been invented will earn trust if they derive from a Greek source (as long as the trickle is moderate). But why did Romans grant to Caecilius and Plautus the privilege that they deny to Vergil and Varius? Why do people begrudge me to acquire a few words where I can, while the language of Cato and Ennius has enriched our ancestors’ speech and brought forth new terms for things? It has been and always will be allowed to produce word coinages of present currency.

In this passage, together with the subsequent one on leaves, Horace names three mechanisms through which cyclical lexical change is achieved. The first category is archaisms, words that have fallen out of use and are revived (70–1);Footnote 30 the second category is neologisms, new words that are necessary to describe new phenomena (48–59); and the third category is callidae iuncturae, the usage of common words in a new context or different setting (47–8, cf. 240–3).Footnote 31 In practice, these three categories cannot always be clearly distinguished, and Horace himself, in fact, conflates them: neologisms are not truly new, as they should ideally derive from a Greek source. Further, though archaisms and callidae iuncturae are old words, they have the appearance of new ones. Horace is thus less interested in a careful definition of these three categories, which at any rate do not appear as neatly listed and defined in his work as they do in my discussion here;Footnote 32 rather, he stresses the cyclical nature of language change, which a number of interrelated mechanisms bring about.

In the same passage Horace puts this theory into practice. One example is pronos in the leaves simile (60): ut siluae foliis pronos mutantur in annos (‘as trees change in leaf from sliding year to year’).Footnote 33 Richard Bentley has noted that Romans do not use descriptive epithets for phrases such as in annos, in dies, or in horas, and he thus reads priuos instead. A. E. Housman says with characteristic wit: ‘I am told that “pronos” is very poetical: I reply, That question does not yet arise. Bentley has not denied that it is poetical; he has denied that it is Latin.’Footnote 34 Yet, the problem is, of course, that the word appears in a passage that is precisely about the unstable nature of the Latin language. In the immediately preceding line, Horace claimed for himself the right to innovate Latin. And as an innovation in Latin, a callida iunctura, the expression pronos in annos is effective: each year glides in a downward slope like heavenly bodies, perhaps reminiscent of the downward motion of falling leaves.Footnote 35 Some lines earlier, Horace had already said that new words should derive, literally ‘fall’ (53: cadent), from a Greek source. Later, he says that words will reappear that have fallen out of usage, and current words will fall out of usage (70): cecidere cadentque. The fall is a universal principle in these lines pertaining to leaves, words, humans, and perhaps also years.

Besides pronos or priuos, the passage includes a number of other notable expressions which underline its message. Thus, when Horace says that people begrudge him his inventiveness of words, he proves that inventiveness through the usage of a syntactical Grecism that is unparalleled in Latin: inuideor, ‘I am begrudged’. For the verb inuideo normally takes the dative in Latin and the passive construction here follows the Greek φθονοῦμαι.Footnote 36 Pointedly, this first-person verb is the only time in the Ars when Horace explicitly mentions his own poetry, as Carl Becker has noted.Footnote 37 We are thus justified in connecting Horace’s theoretical thoughts in these lines with his lyric work – the more so as inuidia is a mark of lyric achievement in the sphragis of Odes 2.Footnote 38 Further striking expressions include callida iunctura, which may itself be a callida iunctura, as the word iunctura was perhaps not used previously in a stylistic context.Footnote 39 In the same sentence, the ‘known word’, notum uerbum, is ironically not known at all: the usual word in this context is usitatum rather than notum.Footnote 40 Then, in line 50, when the Cethegi of old times are surprised about modern words, they would be most surprised about the adjective that qualifies themselves, cinctutis, ‘kilted’, which is a neologism.Footnote 41

It seems, though, that perhaps the most remarkable of Horace’s wordplays has gone unnoticed. This wordplay can be found at the crucial point at which Horace summarises his thoughts on choice of words in one sentence (68–9): mortalia facta peribunt, | nedum sermonum stet honos et gratia uiuax (‘still, all mortal works will perish, and still less is it true that the honour and grace of speech could stay alive’).Footnote 42 Horace’s choice of words here is programmatic and wittily underlines the sense. For neither have the word honos nor the word gratia always stood in honour and favour. The learned Aulus Gellius informs us that honos was not at all times an exclusively positive term in Latin, but used to belong to a category of so-called uocabula ancipitia (12.9; cf. 11.12). This describes words which can denote a positive as well as a negative quality. Gratia is an example for such a word, which Gellius indeed mentions. For bona gratia denotes favour, popularity, and esteem, whereas mala gratia denotes disfavour and unpopularity.Footnote 43 Gellius says that Quintus Metellus Numidicus in the late second century ʙᴄ spoke of peior honos, which supposedly denotes disrespect rather than respect. This meaning of the word was already lost in Horace’s day (if it ever existed outside of the inventive minds of antiquarians).Footnote 44 Yet, that is precisely the point of the passage: now in the present moment and the present context honos and gratia enjoy honour and grace, but this has not always been so, nor will it always be so.Footnote 45 This is also how Horace describes trees, which do not always have their leafage or honos.Footnote 46 And this is, of course, also exactly the message of Horace’s carpe diem. Thus, in one carpe diem poem, Maecenas is asked to enjoy the present moment as Fortune’s favours (honores) are fickle (C. 3.29.51–2). In another carpe diem poem, Horace tells a certain Quinctius to drink, as spring flowers do not always have the same honor (C. 2.11.9–10): non semper idem floribus est honor | uernis.

The vast majority of the words Horace uses in his poetry may seem unremarkable. These words simply represent the normal diction of Latin in Horace’s time.Footnote 47 Yet, the Ars asserts that these common words, too, are subject to change, as words in general are shaped by the changing ‘usage’ (usus) of society (Ars 71–2).Footnote 48 Thus, even seemingly simple, unadorned words in the Odes are an important part of Horace’s diction of the present. Certain words, however, evoke present time more emphatically. Such words – again, archaisms, neologisms, callidae iuncturae – enrich Horace’s diction at crucial points. For instance, when Horace says that archaisms can enrich language, the expression he uses for enrichment, ditauerit, is itself an archaism (Ars 57).Footnote 49 Horace’s attempt to enrich Latin responds to Lucretius’ well-known complaint on Latin’s paucity (sermonii patriis egestas). Horace’s solution for this paucity is striking; he is coining new words (58–9): licuit semperque licebit | signatum praesente nota producere nomen (‘It has been and always will be allowed to produce words bearing the mint-mark of the present’). Like coins, words can bear the mark of the time when they were minted.Footnote 50 Words thus produce effects of presence, according to Horace. Serendipitously, Horace’s expression ‘producing a word with a present mark’ is reborn in our day as literary theory gives new currency to the expression. As Jonathan Culler says, in lyric, uniquely, ‘effects of presence are produced’.Footnote 51 The expression may sound less natural in English than it does in Latin; Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, the scholar who coined the expression, stresses that he uses ‘production’ in the original Latin sense of producere.Footnote 52 Be that as it may, already Horace theorises about how poetry can produce presence. His answer refers to his choice of words. In the following section, I wish to look at a number of Horatian coinages in more detail and analyse how exactly they produce presence.

3.3 Bags Full of Leaves: Coinages in Horace’s Carpe Diem Poems (C. 4.7, 1.11, 1.36)

Among Horace’s books of Odes, Book 4 is the collection that is closest in publication date to the Ars (though the exact publication dates of both the Ars and Odes 4 are a matter of debate). Odes 4 is also Horace’s book of lyric in which scholars have found the highest number of unusual words.Footnote 53 One poem in particular, Odes 4.7, thematises cyclical time and thus invites comparison with the leaves passage from the Ars. I wish to show that the ode is shaped by Horace’s ideas about cyclical time with regard to its content as well as its choice of words. Contemplation of the cycle of the seasons leads to insight into human mortality in this carpe diem poem:

The snow has fled; now grass is returning to the fields, and leaves to the trees. The earth is going through changes, and rivers are subsiding and flowing between their usual banks. The Grace ventures to lead dances naked together with the nymphs and her twin sisters. Don’t hope for immortality; that’s the warning that the year gives you and the hour that snatches away the nourishing day. Cold weather is softened by the West Wind; then spring is crushed by summer, which in turn is bound to die as soon as apple-bearing autumn pours forth its fruits, and soon lifeless winter returns.

Yet, the moon quickly recovers its losses in the sky; but in our case, once we have come down where pious Aeneas went and rich Tullus and Ancus, we are dust and shades. Who knows whether the gods above are adding tomorrow’s tally to the total of today? All the things that you give to your dear soul will escape the greedy hands of your heir. Once you have died and splendidFootnote 54 Minos has made his judgment, Torquatus, not your lineage, nor your eloquence, nor your piety will bring you back. For not even Diana frees chaste Hippolytus from dark Hades, nor is Theseus strong enough to break the Lethean chains that hold his beloved Pirithous.

The poem urges present enjoyment within the revolving cycle of the seasons. Revolving and repetition work on multiple levels. The poem itself is unusually close to an earlier poem, Odes 1.4, and it is universally noted that themes as well as many expressions seem to be revived from this earlier poem.Footnote 55 The poem’s verbs, too, reflect the cyclical change of nature: redire (1), recurrere (12), reparare (13). Nature is all about revival and recurrence, whereas this is not possible for humans: non, Torquate, genus, non te facundia, non te restituet pietas (‘Torquatus, not your lineage, nor your eloquence, nor your piety will bring you back’).Footnote 56 The third stanza expresses this idea most clearly; it describes the cycle of the seasons with impressive economy.

The meditation on nature’s cycle and human mortality in the poem suggests the image of leaves. We all are falling, Horace says (C. 4.7.14): nos […] decidimus. This unusual verb for dying transfers the fall of leaves to humans.Footnote 57 Indeed, the first sentence of the poem has already introduced a connection between leaves and humans. While humans would later fall like leaves, the poem begins by describing leaves as human hairs in the description of their return to trees (1–2): Diffugere niues, redeunt iam gramina campis | arboribusque comae (‘The snow has fled; now grass is returning to the fields, and leaves [literally: hairs] to the trees’).Footnote 58 The generations of leaves and humans in a carpe diem poem – this naturally evokes Simonides. Indeed, scholars have shown the importance of Simonides for the whole ode, and they have identified certain expressions that seem to allude to Simonides directly.Footnote 59 What I wish to stress on the following pages is the significance of the choice of words: like the Ars, Odes 4.7, too, shows an interest in words that fall to the ground and grow again.

In the fifth stanza, Horace tells his addressee, Torquatus, to enjoy the present (17–20):

Who knows whether the gods above are adding tomorrow’s tally to the total of today? All the things that you give to your dear soul will escape the greedy hands of your heir.

Some scholars reject the whole stanza as un-Horatian.Footnote 60 One of its problems is an expression that is unparalleled in Latin: amico animo must equal animo tuo, but such a usage of amicus is not known elsewhere in Latin. It has long been suggested that Horace is here calquing on the Greek, where expressions such as φίλῳ θυμῷ are natural.Footnote 61 Indeed, Kießling and Heinze have wonderfully explained the whole sentence in their commentary; according to them, the expression dare animo already introduces a Grecism (~τῇ ψυχῇ δοῦναι) where Latin would prefer animo obsequi. As Horace follows Greek texts which urge present enjoyment with the expression ‘giving to one’s soul’, he further heightens the Greek sense of the line through his use of amicus.Footnote 62 Kießling and Heinze also adduce some Greek passages which might have influenced the Horatian expression. Chief among them is this line from Simonides’ leaves elegy (fr. 20.12): ψυχῇ τῶν ἀγαθῶν τλῆθι χαριζόμενος (‘endure and pamper your soul with good things’). Horace’s Grecism draws attention to his phrase as a translation from the Greek, something made new. Horace’s expression does not mirror Simonides’ original very precisely, though. Simonides’ model can account neither for dare nor amicus in Horace. It might be better to say that Horace looks through Simonides at a whole Greek tradition in which the idiom of ‘indulging one’s soul’ is common in a carpe diem context. Even a toper could voice this sentiment on his tombstone (GV 1368 apud Ath. 8.336d, discussed on pages 59–61 of Chapter 1): πιέν, φαγὲν καὶ πάντα τᾷ ψυχᾷ δόμεν (‘drink, eat, and give everything to your soul’).Footnote 63

The Grecism appears at a crucial moment in Horace’s poem: the exhortation to enjoy oneself in the moment, as no one can know if the gods add tomorrow’s tally to the total of today (17–18).Footnote 64 In Simonides, the exhortation to gratify one’s soul would have been delivered at the symposium. Listeners could have followed the exhortation among music and cups. Simonides’ addressee, who is described as old, would have had particularly good reason for urgent enjoyment ‘at the end of [his] life’. In reperformances, the implied addressee of the poem would have provided an occasion for urgent enjoyment, even though later audiences might be of various ages. Already in Simonides, addressee and occasion thus go some way towards producing presence rather than simply being present.Footnote 65 Horace’s exhortation in turn conveys a different type of presence.Footnote 66 He uses a strikingly new Latin expression when he exhorts Torquatus to enjoy the present. The words are stamped with the present mark.

The word that is perhaps the most remarkable in the ode is pomifer, ‘apple-bearing’ (11). Horace usually avoids Greek-style compounds of this type.Footnote 67 By contrast, such words are common in Lucretius and Vergil. Indeed, Vergil arguably offers, besides Simonides, the strongest influence on Horace’s choice of words in this poem. An expression that would strike even the most superficial reader as Vergilian can be found in line 15: pius Aeneas. The less likely uaria lectio, which is pater Aeneas, is, of course, just as Vergilian. It is thus very much Vergil’s Aeneas who offers an example for the universality of death in Horace’s poem. Yet, the overt allusion to Vergil only highlights that Horace in fact diverges from Vergil and corrects him: the katabasis of Vergil’s Aeneas in Book 6 of the Aeneid was a round trip, whereas Horace emphasises that journeys to the underworld are always one-way trips. At the end of the poem, Horace also corrects Vergil’s account of the Hippolytus myth and makes his Hippolytus remain in the underworld, whereas Vergil’s Hippolytus would be freed.Footnote 68 Horace’s pomifer is another reference to Vergil, an oppositio in imitando:Footnote 69 Vergil uses malifer for the same idea, a hapax legomenon in the Aeneid and Latin literature as a whole (Verg. A. 7.740, just preceding the myth of Hippolytus). In the Ars, Horace noted that Vergil coins words, while some of his fellow Romans find fault with that (Ars 55). Horace’s pomifer seems to have been coined by himself; the word cannot be found before him.Footnote 70 The uncharacteristic word hints at Vergil, and offers a learned allusion to his friend’s diction: while Vergil uses twenty-four compound adjectives ending in -fer, the word pomifer is the only word of this type in Horace.Footnote 71

The word pomifer also wonderfully illustrates Horace’s principle of word change from the Ars. The word is old, calqued on Greek καρποφόρος or more likely μηλοφόρος, but is simultaneously reborn and made new.Footnote 72 Horace’s pomifer pointedly evokes the cycle of words in a stanza that is all about time and the cycle of the seasons. Summer is about to die once apple-bearing autumn pours forth its fruits (9–11): aestas, | interitura, simul | pomifer autumnus fruges effuderit. The new season is accompanied by a new word; change applies to nature and words. It is also fitting that linguistic change again applies to trees; the generations of apples come and go, each year some apples fall to the ground and new ones grow.

Perhaps the best known of all Horace’s iuncturae is the expression ‘carpe diem’ itself. The phrase appears in the poem to Leuconoe (C. 1.11):

Don’t ask Leuconoe what end the gods have decided for me and for you – it’s not right to know that. And don’t meddle with Babylonian horoscopes. How much better is it to accept whatever will be. Whether Jupiter has granted us other winters or this one is the last one, which is now wearing out the Etruscan Sea against rocks of pumice; either way, be wise, strain the wine, and cut down long-term hopes into a small space. While we are talking, begrudging time will have fled. Pluck the day and put minimal trust in tomorrow.

Though the phrase carpe diem has become something of a cliché and is probably most commonly imagined as spoken by the actor Robin Williams, it is in fact a daring and unusual coinage of Horace, as David West pointed out: ‘We are brought up with carpe diem and cannot see what an astounding phrase it is. Nowhere else in Latin is it used of enjoying a period of time.’Footnote 73 Horace combines several expressions and models in this phrase: Pindar already spoke of ‘plucking youth’ (P. 6.48: ἥβαν δρέπων; cf. fr. 123.1–2 Maehler); Latin authors applied carpo to objects of time at least since Lucilius, though without any implication of enjoyment;Footnote 74 yet, plucking fruits is naturally linked to enjoyment (Epod. 2.19–20): ut gaudet insitiua decerpens pira | certantem et uuam purpurae (‘how he [i.e., the happy country-dweller] rejoices as he plucks the pears that he had grafted and the grapes that compete in hue with purple dye’). Horace combines all these connotations in the daring expression carpe diem. Each word on its own, carpe as well as diem, is unremarkable but their combination is a daring callida iunctura that gives them splendour and produces presence. Thus, Horace describes in the Ars how common words (de medio sumptis) can acquire honour or splendour (honor) through the usage of a iunctura (242–3). In Odes 1.11 the iunctura is striking: the day has to be plucked like a fruit in the momentarily fleeting season. The words that describe this also appear as new and gain new honour through a iunctura within the seasons of words.Footnote 75

If we understand carpe diem as a reference to plucking fruits, such as grapes, then this expression is not the only one in the poem that is taken from viticulture. West noted that earlier in the poem Horace already employed expressions from viticulture in his advice to Leuconoe (6–7): sapias, uina liques, et spatio breui | spem longam reseces (‘be wise, strain the wine, and cut down long-term hopes into a small space’). The tricolon of exhortations blends advice pertaining to Leuconoe’s attitude to life with advice pertaining to wine and viticulture. Being wise is a question of her attitude, straining wine is more practical advice, but the third exhortation combines the two spheres. The verb reseco describes the pruning of vines and thus belongs to the same imagery as uina liques, as West notes.Footnote 76 This metaphorical usage of reseco, pruning long-term hopes, in turn prepares for the expression carpe diem, plucking the day like a grape, according to West.Footnote 77 Yet, Horace is not only pruning long-term hopes into a small space (spatio breui | spem longam reseces); he is also pruning poetry – none of Horace’s odes consists of fewer lines, and the poem is wider than it is long.Footnote 78 The poem itself feels pruned to a short space. Its form thus mirrors its content, and its metre furthers this impression: the Greater Asclepiad in this poem confines several phrases in a short space.Footnote 79

Pruning poems as if they were vines is one of Horace’s recommendations in his literary letters. Thus, Horace tells the Pisones at Ars 291–4 that one should thoroughly ‘clip’ a poem (coercuit and praesectum).Footnote 80 Later, at Ars 445–50, he repeats the advice and says that a good critic, in the fashion of a vinegrower, would check useless growth (reprehendet inertes), find fault with too-hard wood (culpabit duros), mark untrimmed plants for winter pruning (incomptis allinet atrum | trauerso calamo signum), and, in order that the plant receive more light (parum lucem dare coget), ‘prune pretentious ornamentation’ (ambitiosa recidet | ornamenta).Footnote 81 The image is most developed in the Florus letter. There, Horace says that anyone who wishes to write a proper poem should also take up the spirit of a stern censor and rid his diction of words that are undeserving of honour (honore indigna). There follow some lines on choice of words, archaisms and neologisms, which are similar in nature to Horace’s later discussion of the issue in the Ars. The good poet will also need good pruning skills when it comes to his choice of words (Epist. 2.2.115–25):

He [i.e., someone who wishes to write a good poem] will do well to unearth words that have long been obscure to the people, and he will bring splendid terms to light, which people like Cato or Cethegus of old used to know, but which now lie buried under ugly neglect and desolate old age. And he will admit new words which need has fathered and brought forth. His flow of words will be powerful and clear, and just like the flow of an unpolluted river he will spread prosperity and enrich Latium with the wealth of his language. He will cut back excessive (otiose!) foliage verbiage, he will smoothen what is too rough with beneficial attention, and he will uproot those words that lack dignity. Although he torments himself, you would think that he moves between registers with playful ease like a dancer who becomes a satyr in one moment and a rustic cyclops in the next one.

There are quite a few different metaphors in play here. Neologisms can enrich the Latin language as a river enriches the countryside (120–1),Footnote 82 but old words are also similar to precious metals that are brought to the surface (115–16). Further, Horace compares the ideal poet’s effortless motions between different words and registers to a dancer who seamlessly changes from one style to the other as he represents different characters in a pantomime (124–5). Horace’s words, then, have the performative quality of momentary dance, as they evoke presence.Footnote 83 Other images from this passage would be echoed in the Ars. Thus, words are likened to human beings when they are oppressed by old age (118).Footnote 84 Finally, Horace again uses imagery taken from vegetation when he says that words need pruning (122–3). Odes 1.11 already anticipates in practice Horace’s theoretical thoughts.Footnote 85 The poem is cut back so that certain striking expressions can shine and are not overshadowed by pretentious ornamentation: carpe diem quam minimum credula postero (‘pluck the day, and put minimal trust in tomorrow’).

In Odes 1.36, Horace celebrates the return of Numidia from Spain and describes a drinking party. This is a special day, and Horace says that the day should accordingly be marked with an auspicious white mark (nota) in the calendar (10): Cressa ne careat pulcra dies nota (‘don’t forget to mark this beautiful day with white chalk [literally: with a Cretan mark]’).Footnote 86 As we will see, Horace also marks the present day again with a word coinage that bears the mark (nota) of the present (Ars 59: signatum praesente nota producere nomen; ‘to produce words bearing the mint-mark of the present’).

The party will include ‘long-lived celery’ and ‘short-lived lily’, and this contrast in bloom brings the carpe diem motif into the poem (C. 1.36.16).Footnote 87 Earlier in the poem, Horace describes the revelry that should take place at the party and says that ‘Damalis, that drinker of much neat wine, must not be allowed to beat Bassus at downing the Thracian cup’ (C. 1.36.13–14): neu multi Damalis meri | Bassum Threicia uincat amystide.Footnote 88 The word amystis seems to appear here for the first and only time in Latin. The term ἄμυστις can describe both a long draught and a type of large cup that is well suited for heavy drinking.Footnote 89 It has long been recognised that this Grecism points to a well-known passage from Callimachus’ Aetia, in which the poet is present at a symposium and is delighted to see that another guest also dislikes heavy drinking (fr. 178.11–12 Harder):Footnote 90

For he [i.e., the other guest] also detested drinking neat wine with his mouth wide open in large draughts as the Thracians do; but he liked small cups.

Horace reverses the situation and positively encourages heavy drinking. It is clear that Horace’s Threicia amystide picks up Callimachus’ Θρηικίην ἄμυστιν, but Horace’s translation is even neater, as the similarities with Callimachus go further. The Grecism amystide drenches the whole sentence with Greekness and alerts the reader to further Grecisms. There is indeed another expression in the line which has a Greek feeling to it. The genitive of description, multi meri, is mannered, and Horace regularly uses such genitives of description when he renders Greek compounds in Latin.Footnote 91 In the present case, the compound ζωροπότης might be lurking behind Horace’s multi meri. Admittedly, potor meri would have been a closer translation of this Greek word than multi meri, and Nisbet and Hubbard rather think of πολύοινος as a Greek equivalent of multi meri.Footnote 92 Nonetheless, ζωροπότης seems the more likely model; πολύοινος is not used in poetry, and it is difficult to see how a random word from Thucydides and other historians would have influenced Horace’s diction here. Second, and more importantly, the Callimachean intertext is crucial for the passage; Horace translates Callimachus’ striking expression Θρηικίην […] χανδὸν ἄμυστιν ζωροποτεῖν: multi Damalis meri Threicia uincat amystide.

The word ζωροποτεῖν is an important word in the Aetia fragment and it would be odd if Horace did not pay attention to it in his allusion to the passage. For the word is modelled on the Homeric hapax legomenon ζωρός, which (presumably) means ‘neat’ and appears at Iliad 9.203. In the following chapter, I will look at this term and its usage in some more detail, as I discuss the importance of cups of neat wine and other objects for the poetics of carpe diem.Footnote 93 For now, I just wish to stress that ζωρός is an important term in carpe diem poems from Asclepiades in the third century ʙᴄ to Marcus Argentarius in the first century ᴀᴅ. Horace writes his carpe diem poetry into this tradition of drinking wine neat. Horace’s choice of words again fits the model of the Ars: the new word amystis produces presence and lets us imagine a moment at the party when this word is used. And yet, the word is, of course, also old, revived from Callimachus, and much the same is true of multi meri, which also points to a Greek source. The words evoke the present moment of Horace’s party, but they also evoke other older parties, such as Callimachus despising Thracian drinking rites, and even Achilles pouring wine for his guests in his tent. The words mark a Horatian now that exists always again.

Perhaps it is also possible to look at amystis from a slightly different angle by considering its register. Adam Gitner observed that many of Horace’s Greek terms for drinking vessels belong to an informal register; though such terms may evoke literary precedents, they are essentially colloquial, intimate words, used at drinking parties.Footnote 94 Gitner illustrates his case with a wonderful example from English poetry. In his example, Housman pointedly uses the informal word ‘can’ in the refrain of one of his poems in order to stress the intimate atmosphere: ‘Pass me the can, lad.’Footnote 95 The term amystis is not discussed by Gitner, but, as I noted, this term, too, can describe a drinking vessel as well as a manner of drinking. The unusual word amystis would then evoke the intimacy, revelry, and music of the drinking party where people would often simultaneously drink from a large Amystis cup and sing, as Athenaeus informs us in his discussion of cups (Ath. 11.783d–e, quoting the carpe diem poem PMG 913 apud Amipsias fr. 21, which mentions the Amystis cup).Footnote 96 This discussion of Horace’s Thracian cup of song gives some taste of the next chapter, where I will discuss cups in some more detail – yet, before this cup is downed in one draught here, it is perhaps time to finish the present chapter.

There are a few more leaves left to gather in Horace. A comprehensive treatment of Horatian style which pays careful attention to his choice of words is still a desideratum.Footnote 97 In this chapter, I have confined myself to a smaller task – instead of soaring over the whole Horatian forest of words, I have, like a bee, gathered some lovely thyme here and there: I hope to have shown how Horace produces effects of presence through his choice of words. Just as the motif of carpe diem is the overarching ethos of the Odes, although it is not, of course, included in all of them, so the choice of words in carpe diem odes has a particular significance, although similar techniques can also be observed in other odes; but it is in carpe diem poems where lyric and linguistic presence programmatically merge. Horace’s carpe diem poems as well as the individual words of which they consist evoke present moments that occur within the cycle of the seasons.