Introduction

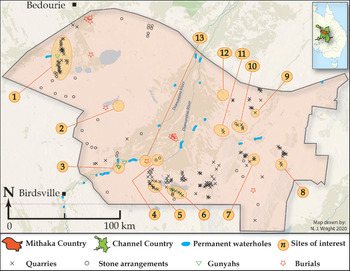

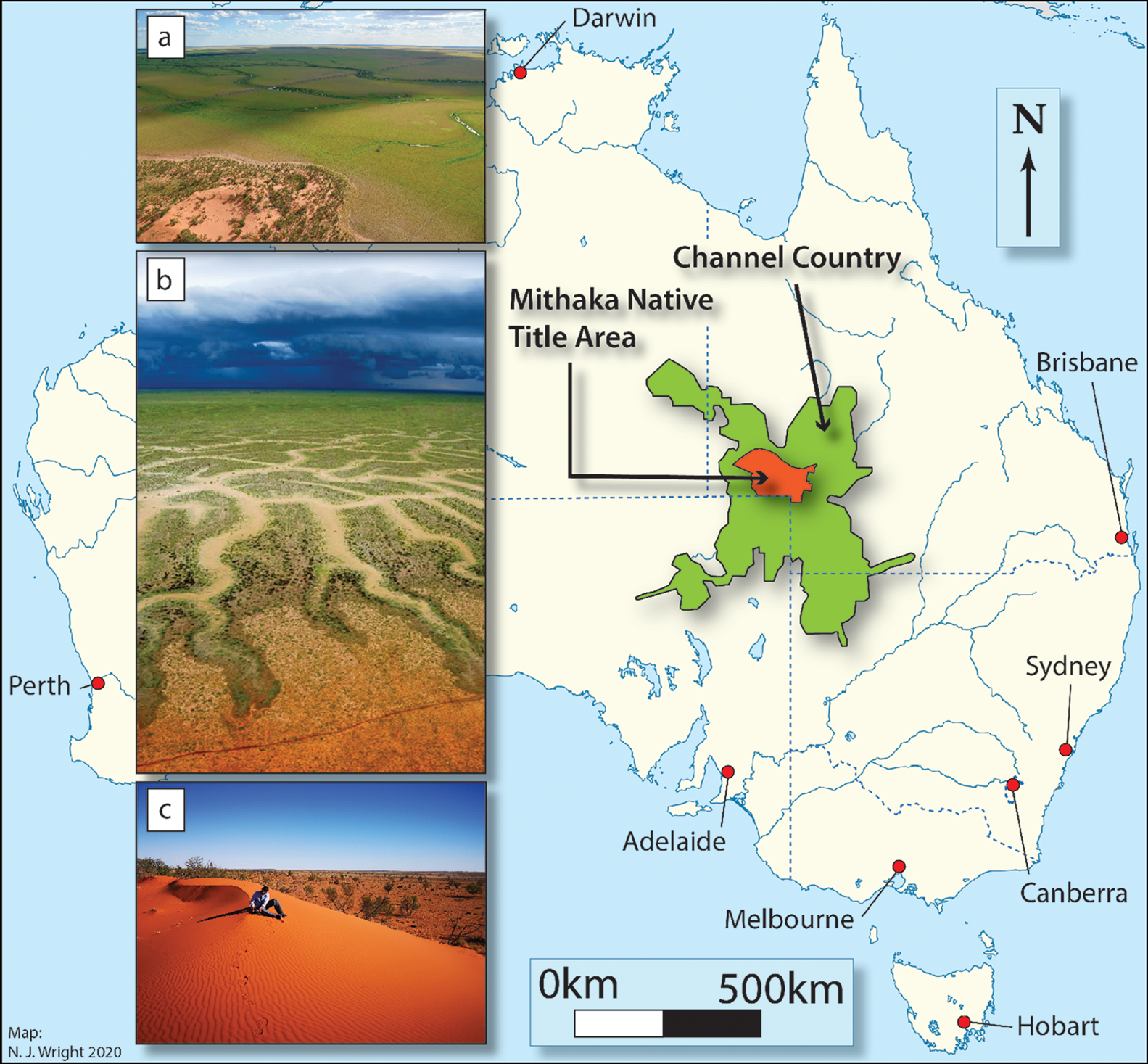

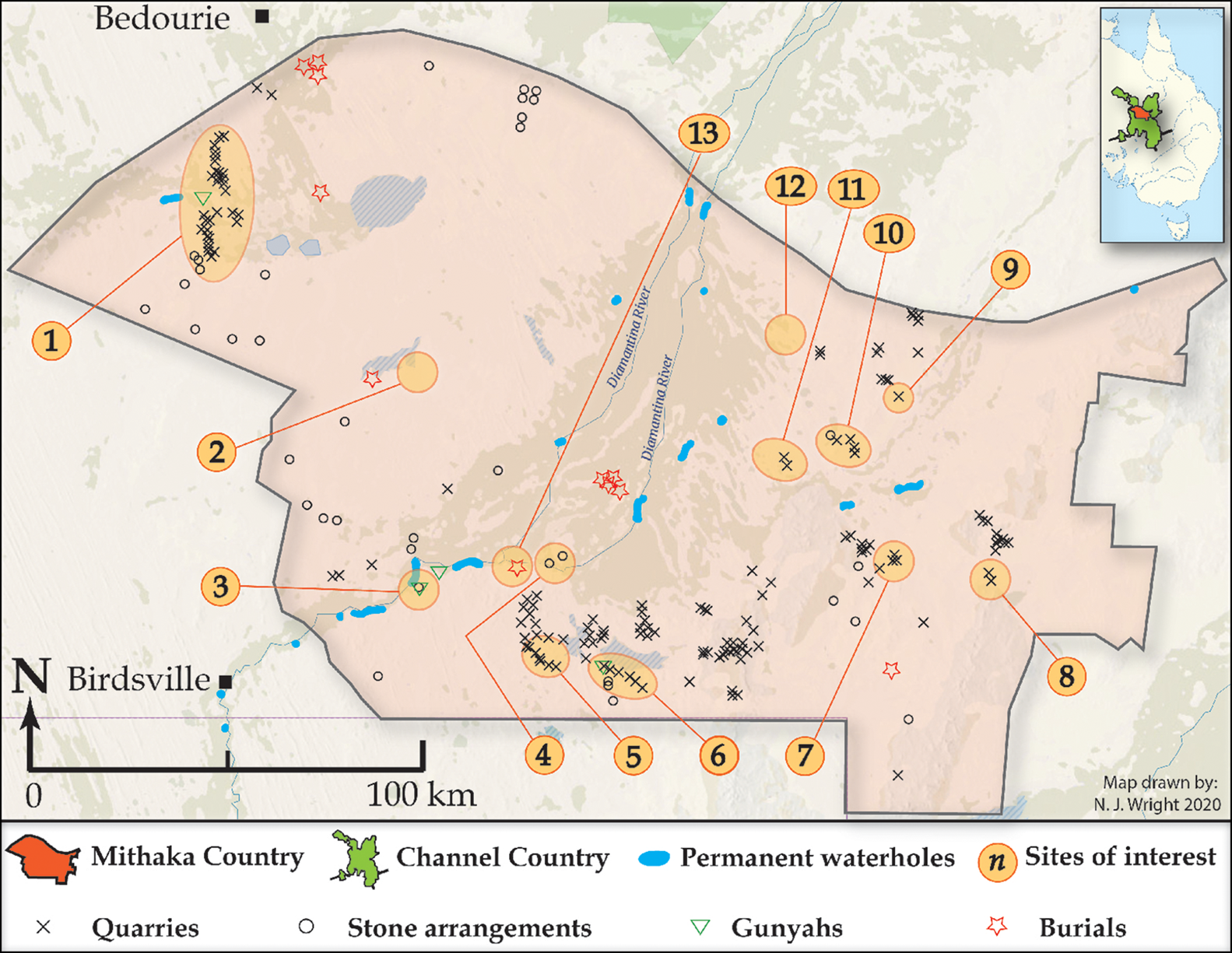

In this article, we report the first results of an ongoing archaeological project in the traditional territory of the Mithaka people, in Australia's Channel Country (Figure 1). Located predominantly in Queensland, Channel Country encompasses an area of approximately 280 000km2 characterised by a ‘boom-and-bust’ ecological system, with massive semi-annual floods of the desert. The floods derive from monsoonal rainfall in the north that fills the thousands of braided channels after which the region is named, resulting in lush vegetation that contrasts starkly with the bordering stony plains and longitudinal desert dunes. Despite the importance of its natural heritage, Channel Country has experienced limited archaeological investigation.

Figure 1. Location of Mithaka Country and illustrations of the channels in flood (a–b) and linear dune systems (c) (map by N.J. Wright; a–b provided by Helen Kidd, with permission from Barcoo Shire Council).

The current project was initiated in part by the Mithaka Aboriginal group, who see archaeology as a means of deepening their connections with the traditional cultural landscape. In the early twentieth century many Mithaka reluctantly moved away from their long-established way of life to work instead on pastoral stations, fearing the removal of their children through the policies of forced assimilation implemented by Australian governments at that time. The importance that the Mithaka place on archaeological research is reflected in their research framework, ‘Ngali Wanthi’ (‘we search together’) (see https://mithaka.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/mithaka-aboriginal-corporation_research-framework_web-version-72dpi1.pdf).

Numerous ethnohistoric accounts of the Channel Country document the existence of Aboriginal villages and food-production practices; indeed, this region was identified as a key place for research into the controversial notion that Aboriginal groups practised something akin to ‘agriculture’ (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2008). Australia has often been referred to as a continent of hunter-gatherers (Lourandos Reference Lourandos1997). Thus, the suggestion that groups such as the Mithaka may have developed a different socio-economic system has been the subject of criticism, as redefining the nature of Aboriginal food-production systems has important implications for how we understand traditional Aboriginal society. Moreover, the Australian experience is often influential on the interpretation of hunter-gatherer societies elsewhere. Evidencing a different mode of food production in Mithaka Country could have global implications for how we define and interpret food procurement.

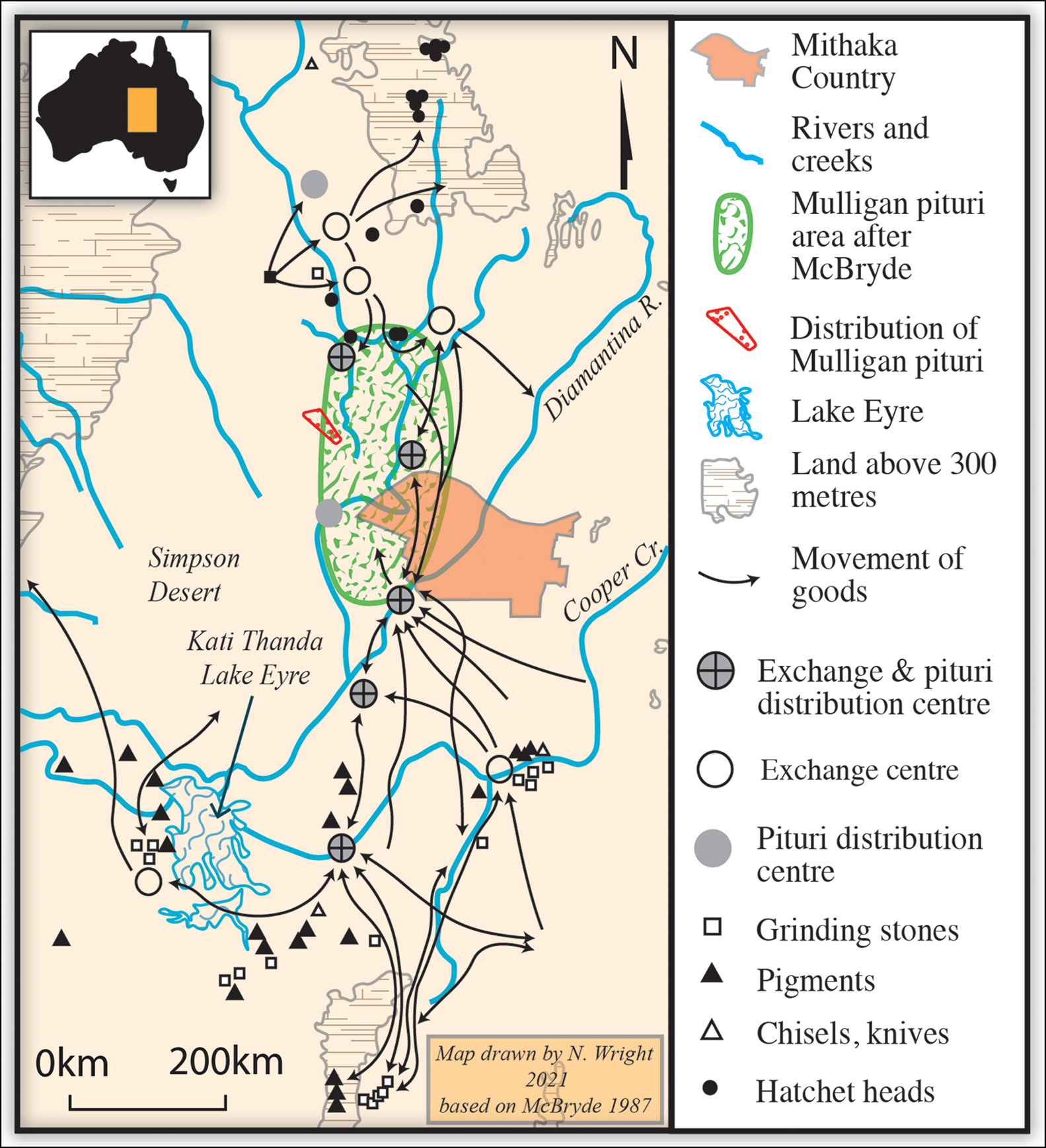

A further long-term objective of the project is to investigate the Mithaka's involvement in the extensive production, trade and ceremonial network that focused on the narcotic pituri, made from the plant Duboisia hopwoodii (Roth Reference Roth1897, Reference Roth1904; Smith Reference Smith2013). Spanning some 500 000km2 (Letnic & Keogh Reference Letnic, Keogh, Robin, Dickman and Martin2010), this network has been described as “oil[ing] the interaction of different societies in a huge section of Australia” (Davidson et al. Reference Davidson, Tarrago, Sullivan, Donovan and Wall2004: 15). Mithaka Country is close to the centre of the pituri network, and therefore archaeological documentation of this region may illuminate the wider network's origin and evolution. The rich cultural landscape of the Mithaka, which has been largely protected thanks to its remote location, therefore offers the opportunity to examine questions of broad as well as local signficance.

Channel Country environment

The Channel Country is atypical of Australian arid environments, being distinguished by an extensive endorheic (internally draining) river system. One of the largest examples in the world, this system is formed by the Georgina River, Diamantina River, Cooper Creek and Farrars Creek. Collectively, these watercourses supply the majority of the water flowing into Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre, the largest lake in Australia (McMahon et al. Reference McMahon, Murphy, Peel, Costelloe and Chiew2008).

Rainfall in the region is low (120–400mm per year), and rivers rely almost entirely on monsoonal rain falling on the upper catchments, mostly in summer (December to March). Influenced by the El Niño Southern Oscillation, drainage is characterised by extreme flow variability (Puckridge et al. Reference Puckridge, Walker and Costelloe2000). Some flow occurs in most years, but periods of three to five years without surface water are also common (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Bunn, Thoms and Marshall2005). Every few years, cyclonic activity to the north inundates the area with floodwater, filling dry river channels and transforming floodplains into vast ‘inland seas’. Consequently, the area's ecology is dominated by ‘boom-and-bust’ cycles: each flood replenishes soil nutrients by depositing new alluvium and, as the floods recede, vegetation grows rapidly in a pulse of productivity. Flood recession creates a wide network of waterholes in the channels, where fish and crustaceans can be found. Away from rivers, Channel Country contains a mixture of Mitchell grass downs, stony plains, open shrublands, ephemeral forblands (land covered in herbaceous, flowering plants) and, in higher-rainfall areas, woodland communities. Prior to European incursion and the arrival of feral predators (e.g. cats and foxes), the vertebrates of the Channel Country were considerably more diverse and numerous (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1961; Van Dyck & Strahan Reference Van Dyck and Strahan2008) (see Table S1 in the online supplementary material (OSM)). In the past, the greater biomass concentrated within this rich channel system—compared with the adjacent deserts—provided a rich economic resource for the Mithaka.

Key ethnohistoric observations

A heavy reliance on ethnohistoric accounts in the reconstruction of Australia's prehistory has come under criticism in the past (Hiscock Reference Hiscock2007), but such data remain important for generating hypotheses to test against archaeological evidence (for relevant ethnographic observations, see Table S2 in the OSM).

Captain Charles Sturt provided the first European observations of Aboriginal people in Channel Country in 1845 (Davis Reference Davis2002). Sturt noted large populations living in villages, grinding seed to produce ‘cake’ and storing up to 45kg of grass seed in kangaroo skins (Davis Reference Davis2002). By the 1870s newspapers were reporting that the “civilised aborigines” of the Channel Country maintained themselves by “cultivation and fishing” (Evening News 1876). Seeds (nardoo, pigweed, nut grass and native millet) were described as being managed and stored in very large quantities (Goulburn Herald and Chronicle 1873).

Dwellings (‘gunyahs’) were often located near water, where waterfowl, fish and mussels were intensively exploited. This included the use of fish traps and storage pens, the latter used to retain fish for gatherings and produce ‘fish flour’, a product that was important in trade and exchange networks (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1952).

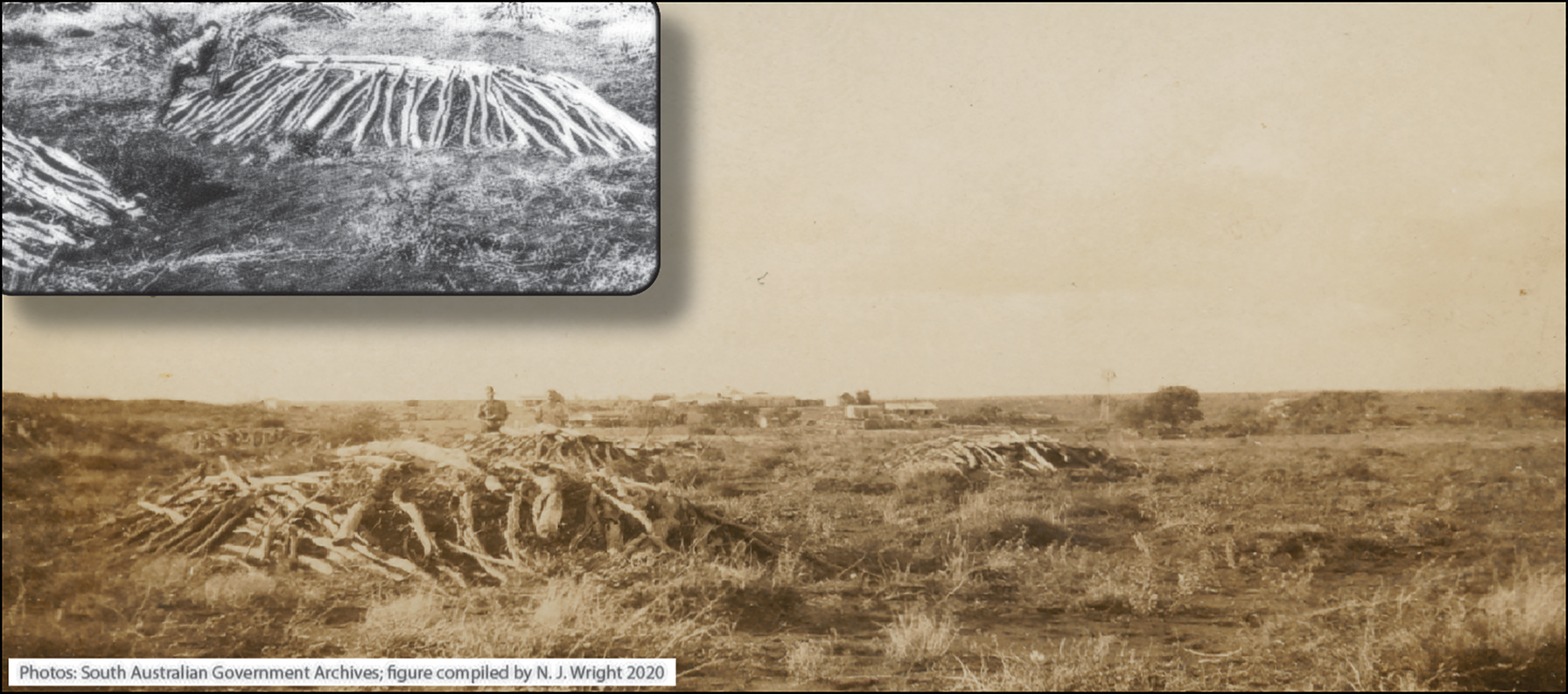

Historical photographs document several monumental graves at Arrabury Station on the southern boundary of Mithaka Country (Figure 2). These graves were large, oval earthen mounds covered with logs and branches (Figure 3). Given ethnohistoric accounts that the people of the Channel Country lived in villages, it is worth noting that Indigenous cemeteries elsewhere in Australia have been argued to be connected with sedentism and land ownership (Pardoe Reference Pardoe1988; cf. Littleton & Allen Reference Littleton and Allen2007).

Figure 2. Mithaka Country showing all newly recorded sites, with numbers highlighting significant sites (map by N.J. Wright).

Figure 3. Aboriginal cemetery at Arrabury Station in 1931 (figure compiled by N.J. Wright; photographs: Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2008, courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, PRG 1435/1/10).

As noted, the Mithaka economy partly relied on an extensive network of production and trade and ceremonial festivals that focused on pituri (Figure 4). Packets of up to 32kg of pituri were traded, often accompanied by the exchange of songs and dances, the manufacture, display and barter of ceremonial paraphernalia (e.g. down, fibre, ochre and resin), and the production and exchange of quality utensils (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1933). Smith (Reference Smith2013) suggests that this exchange network developed within the last 1000 years, but this estimate is based on limited data and requires further research.

Figure 4. The pituri trade-and-exchange network reconstructed primarily from ethnohistoric data. Ecological survey of the distribution of the Mulligan pituri groves (Silcock et al. Reference Silcock, Tischler and Smith2012) reveals a range much more restricted than ethnohistoric accounts have suggested, highlighting the importance of fieldwork to assess ethnohistoric evidence (map by N.J. Wright, based on McBryde Reference McBryde, Mulvaney and White1987).

Quarrying was integral to the operation of the exchange network, providing many of the materials that were traded. One of these was mineral pigments, essential for ceremonies, decoration of objects and personal adornment (Howitt Reference Howitt1904). Duncan-Kemp (Reference Duncan-Kemp1933: 209) records that “a flax-wrapped packet of ochre, sorted into many grades and colourings […] was worth many spears, boomerangs or other goods”. Stone hatchets, an important commodity, were quarried and manufactured in the Mount Isa area to the north of Channel Country (Roth Reference Roth1897, Reference Roth1904; Tibbett Reference Tibbett2002; Hiscock Reference Hiscock, Macfarlane, Mountain and Paton2005), and tula adzes—predominantly of chalcedony—were also exchanged (Hiscock Reference Hiscock1988). Ethnographic accounts record centres of grindstone production for the Channel Country exchange system in the area south of Mithaka Country, in the Flinders Ranges, and near Anna Creek and Innaminka (McBryde Reference McBryde, Mulvaney and White1987, Reference McBryde1997; Smith et al. Reference Smith, McBryde and Ross2010).

Fieldwork results

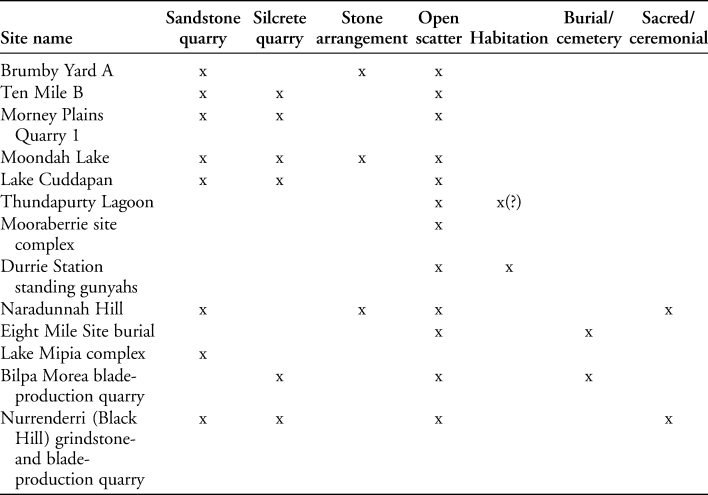

In 2017, Mithaka Elder George Gorringe led us to several sites, including substantial sandstone quarries where grindstones had been produced. Following these visits, we suspected that those sites were sufficiently large to be visible on satellite imagery. We conducted searches using Google Earth, Zoom.Earth and Queensland Globe, focusing on areas with outcropping rock. We identified 179 potential quarry sites over an area of 33 800km2. We subsequently visited 45 of these sites, and all 45 demonstrated evidence for anthropogenic activity. Here we provide summary descriptions of the main types of site that we documented. Table 1 lists the key sites visited, along with their general characteristics.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the key sites visited.

As we had found no mention of sandstone procurement in the detailed ethnohistoric accounts pertaining to Mithaka Country, the identification of 179 such sites was unexpected, particularly as some were very large. Currently, the total extent of quarried surface areas recorded is approximately 260ha. The quarries exhibit distinct areas of deep, circular to ovoid conjoining pits separated by substantial rubble walls, which rise to between approximately 0.5 and 5m above the pit base. In places the quarry areas are flanked by features constructed with low stone rubble walls and sandy flat interiors.

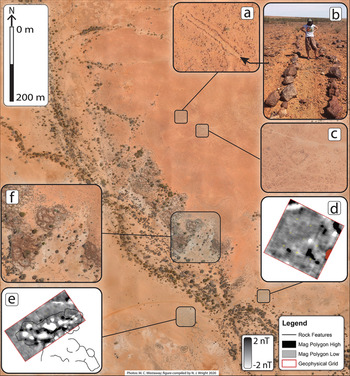

Some of the sandstone quarries are associated with other types of features (Table 1). While the latter are predominantly silcrete quarries, they also include stone arrangements and open camp sites. The Brumby Yard A site—a mid-sized quarry by Mithaka Country standards (approximately 59 750m2)—yielded numerous grindstone blanks, with evidence for several stages of grindstone production. In addition, the site includes a multi-component stone arrangement on a nearby ridge (Figure 5a–c). This arrangement comprises an elongated bounded area and a series of heavily worn paths, one of which is lined with stone.

Figure 5. The Brumby Yard A site includes a ceremonial complex incorporating a stone-lined pathway (a–b) and several stone arrangements (c). Geophysical survey identified an area to the south of the main complex where hearths may be located (d), along with possible infilled quarries (e). Numerous deep quarry pits for extracting grinding-stone slabs are located across the site (f) (figure compiled by N.J. Wright; photographs by M.C Westaway).

Magnetic gradiometry survey measures alterations in the local magnetic field and is used to detect material rich in iron or with thermoremanent magnetisation (Lowe Reference Lowe2012), the latter often associated with hearths. We undertook a magnetic gradiometry survey of the Brumby Yard A site to explore the possibility that fire was used to fracture the bedrock as observed at other quarry sites in Australia (e.g. Roth Reference Roth1904). Our survey identified several positive magnetic values (Figure 5d–e), which suggest that fire may have been used in the quarrying process.

As ethnohistoric sources have recorded villages, and there is some evidence for the stone foundations of gunyahs in northern Channel Country (Wallis et al. Reference Wallis, Davidson, Burke, Mitchell, Barker, Hatte, Cole and Lowe2017), we initially intepreted a series of stone-lined structures at the Ten Mile B site (Figure 6) as hut foundations. Excavation, however, revealed that the structures were quarry pits infilled by aeolian (windblown) deposits.

Figure 6. The Ten Mile B site. Excavation revealed that the suspected hut foundations are probably infilled quarry pits. An initial OSL age estimate of 2130±820 years (GU65.2) was obtained for the aeolian infill of the quarry pit, providing a terminus ante quem for the quarrying of sandstone at the site (figure by N.J. Wright).

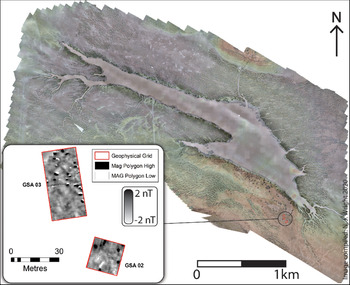

The excavation at Ten Mile B led us to consider ways of distinguishing the remains of Aboriginal dwellings from other anthropogenic features, such as infilled quarry pits. Accordingly, we investigated two locations with historical accounts of multiple gunyahs to determine if any evidence for village-style settlements remained. One of these locations, Thunderpurty Lagoon, was reported in 1871 to have had 103 hut structures (Gilmour Reference Gilmour1871). Our investigations identified no signs of structures at this location, but, in an elevated area bordering the lagoon, we found evidence consistent with extended occupation in the form of numerous fragments of grinding stone and a diverse range of lithic raw materials. A magnetic gradiometry survey revealed multiple anomalies similar in size and magnitude to those observed at the quarry sites (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Drone image of Thunderpurty Lagoon and location of the geophysical survey (left) and magnetic gradiometry results (figure by N.J. Wright).

Further efforts to identify the archaeological signature of a dwelling included the excavation of previously recorded standing gunyahs at Durrie Station. A magnetic gradiometry survey was undertaken at one of the gunyahs, identifying several anomalies consistent with combustion features (Figure 8). Wood samples were taken from the outer edge of a branch from two of the gunyahs and subjected to acid-base-acid-bleach pretreatment, prior to graphitisation and measurement on a Single Stage AMS (Fallon et al. Reference Fallon, Fifield and Chappell2010). Dates were calculated according to Stuiver and Polach (Reference Stuiver and Polach1977), using an AMS-derived δ13C value, and then calibrated with SHCal20 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020) and Bomb 13 SH 1–2 (Hua et al. Reference Hua, Barbetti and Rakowski2013) in OxCal v4.4 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009). The age estimates fall on a plateau in the calibration curve, resulting in wide date ranges. The sample from gunyah one returned a date of 1670–1955 AD (185±23 BP at 95.4% probability; S-ANU#58413), while the sample from gunyah two returned a date of 1654–1955 cal AD (168±20 BP at 95.4% probability; S-ANU#58414).

Figure 8. a) Photograph of gunyah two at Durrie Station taken in 1937 (courtesy of the National Libraries of Australia); b) magnetic gradiometry survey results with low and high values highlighted; c) excavation of anomalies within the gunyah (photograph by N.J. Wright; figure compiled by N.J. Wright).

Ceremonial sites are an important element of the Mithaka landscape. One such site is Naradunna Hill, which was a place of significant spiritual power, a living symbol of ancestral heroes who dwelt in the rock (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp2005). In a potential convergence of ethnographic and archaeological evidence, our ground survey recorded prominent stone arrangements on the hill's summit. Although such stone arrangements were not mentioned by Duncan-Kemp, we consider their presence to be consistent with the hill being a place of great ceremonial importance. The upper slopes of the east side of the hill had archaeological evidence of a more mundane nature in the form of grindstone quarries extending across an area of ~6600m2 and scatters of flaked silcrete artefacts, suggesting that at least some totemic landscape features also functioned as sites of economic activity. We recorded a similar occurrence at Nurrenderri (Black Hill)—‘The Teacher’—where a silcrete blade quarry and a 1650m2 grindstone quarry are located on the summit of this important ceremonial site (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1968: 300–301).

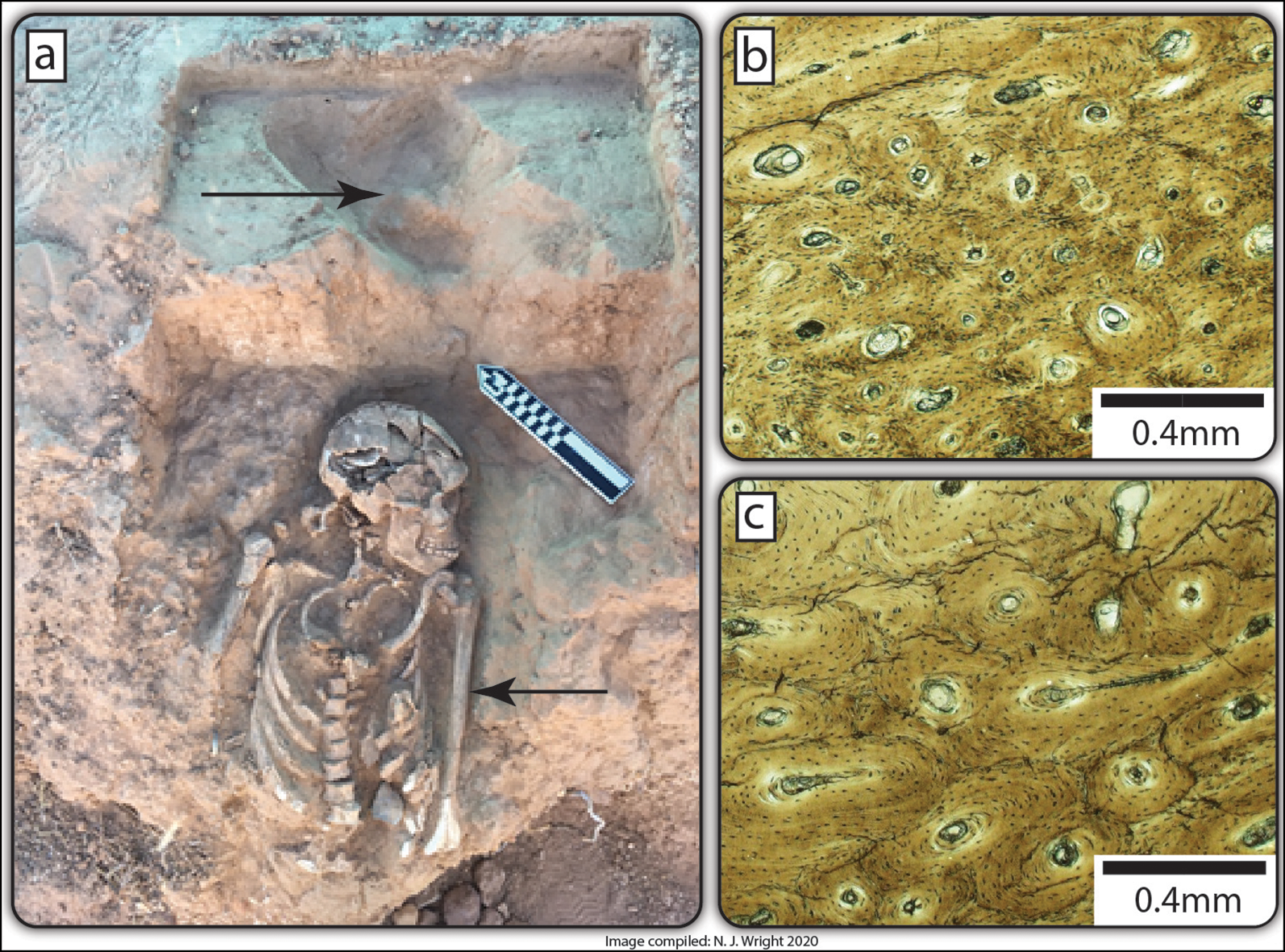

Lastly, at the request of the Mithaka Aboriginal Corporation, our team carried out a rescue excavation of the partial skeleton of a young Aboriginal woman at the Eight Mile site (Figure 9). While osteological analysis has yet to be concluded, histological analysis of a left midshaft humerus fragment provides evidence for the formation of dense Haversian bone (Figure 9), potentially indicating adaptation to heavy work (e.g. Lanyon et al. Reference Lanyon, Goodship, Pye and MacFie1982). Seed processing with grindstones is one obvious possibility for the types of labour she may have undertaken, as this is an ethnohistorically documented activity for women in Channel Country (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1933). We located two further, largely destroyed burials close to that of the young woman. In addition, the Mithaka know that a fourth burial was once present in the same area, although no trace of it remains. The occurrence of four burials in close proximity raises the possibility that the Eight Mile site may have been a mortuary complex similar to that documented at Arrabury (Figure 3).

Figure 9. Burial of a young Aboriginal woman at the Eight Mile site (a). An animal burrow cut across the burial (top arrow; photograph by M.C. Westaway). Two regions of interest from a histological section in the mid humerus (bottom arrow) illustrate the high vascularisation of the primary bone, punctuated with isolated secondary osteons (b) and regional Haversian remodelling evident from closely packed secondary osteons (c), possibly stimulated by biomechanical strain (figure compiled by N.J. Wright).

Future directions

While our project is in its early stages, it is clear that Mithaka Country has a remarkable and abundant archaeological record. Over the next few years, we are particularly interested in improving our understanding of three main issues:

1) The role played by the quarries in the economic and social life of the region.

2) The nature of food-production practices.

3) The structure of settlement systems and degree of sedentism.

Previous research has indicated that quarrying by hunter-gatherers in Australia could be an intensive, organised and culturally regulated activity with significant economic rewards (McBryde & Watchman Reference McBryde and Watchman1976; McBryde Reference McBryde, Mulvaney and White1987, Reference McBryde1997). Grindstone quarries can also be associated with a strong ceremonial component, as demonstrated at the site of Kurutiti in Central Australia (Mulvaney Reference Mulvaney2001). Our data corroborate these earlier findings, although the number of quarry pits we have identified indicates a scale of production beyond that hitherto documented (cf. McBryde Reference McBryde, Mulvaney and White1987; Mulvaney Reference Mulvaney1997; Smith et al. Reference Smith, McBryde and Ross2010). Currently, however, it is less clear whether the evidence attests to a lower rate of extraction undertaken over a long period of time or a rapid uptake and proliferation of a grinding tradition within a shorter timeframe. One major goal for the next phase of our project is to improve the dating of the quarries we have identified, as understanding their chronology will help establish the intensity of quarrying while hinting at possible changes in subsistence and exchange over time.

As noted above, Channel Country groups were witnessed creating and caching considerable quantities of high-quality sandstone grinders, tula adzes and knives for trade during the period of early contact and colonisation (1861–1910s). Nevertheless, very little archaeological research has focused on understanding lithic production in the region. Although Smith (Reference Smith2013) summarises the volume of objects created for trade in the southern part of the Lake Eyre Basin, the extent of grindstone movement within the network is unclear. The ethnohistoric accounts of grinding stones traded in Channel Country are silent on the contribution of Mithaka quarries within the trade network (Roth Reference Roth1904; McBryde Reference McBryde, Mulvaney and White1987). This is curious, given the potentially enormous scale of production evidenced by the quarries that we have recorded. To investigate these issues, we shall deploy thin-section analysis, portable X-ray diffraction and laser ablation to identify distinguishing features of the sandstone outcrops at the different quarries we have identified.

Recently there has been renewed interest in the possibility that Indigenous Australians engaged in agriculture before European colonisation (Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2008; Pascoe Reference Pascoe2014). In this context, there is evidence that the Mithaka constructed earthern weirs to retain water as part of a flood-driven irrigation system in order to increase the productivity of local plant species (Duncan-Kemp Reference Duncan-Kemp1968). This included cultivating small numbers of plants as part of increase ceremonies (religious ceremonies designed to maintain the productivity of resources). Duncan-Kemp (Reference Duncan-Kemp1933: 146–47), for example, notes that “ [women] sprinkled seed food over the ground […] Katoora or barley-grass seed lay in little hillocks, already swelling and creeping to repeated applications of water […] poured on them to make wunjee all the same walkabout [grass to grow]”. Targeted archaeological research is required to assess whether the ancient Mithaka engaged in these and other cultivation practices. We plan to examine pollen from cores taken from lakes and wetlands located close to settlement sites to investigate whether ethnographically identified cultivars exist in the natural biota; we will also assess whether they are present in deposits at archaeological sites. Lastly, we will combine ethnobotanical and genomic techniques to identify evidence for the movement of plant species beyond their normal biogeographic range, as per Rossetto et al. (Reference Rossetto, Ens, Honings, Wilson, Yap, Costello and Bowern2017).

The ethnohistoric record reported above indicates that plant and animal resources may have been manipulated for food production. This raises questions in relation to the possible sedentary nature of the Mithaka population. If food production was part of the Mithaka economy, then the suggestion that villages were part of the ‘package’ (cf. Pascoe Reference Pascoe2014) requires consideration. Although a number of archaeological sites identified over the last 50 years may fit the ‘village’ designation (e.g. Kelly Reference Kelly1968; McDonald & Berry Reference McDonald and Berry2017; McNiven et al. Reference McNiven, Dunn and Crouch2017; Wallis et al. Reference Wallis, Davidson, Burke, Mitchell, Barker, Hatte, Cole and Lowe2017), there persists a hesitancy among Australian researchers to accept village sites as part of the Australian archaeological record (e.g. David & Weisler Reference David and Weisler2006). The dating of some of these sites (McNiven et al. Reference McNiven, Dunn and Crouch2017) further complicates the issue, as it indicates a post-contact date for some domestic structures, leading some scholars to argue they may represent a response to European settlement (Frankel Reference Frankel2017).

To test the hypothesis that Aboriginal people developed villages, our investigations in Mithaka Country will include examining standing gunyahs to establish whether they have distinct archaeobotanic, geochemical and parasitic signatures (see Fairbairn et al. Reference Fairbairn, Wright, Üstünkaya and Fenwick2017; Perri et al. Reference Perri, Power, Stuijts, Heinrich, Talamo, Hamilton-Dyer and Roberts2018; Rowley et al. Reference Rowley, French, Milner, Milner, Conneller and Taylor2018). Our initial surveys and excavation have identified the presence of anomalies within and around gunyah sites that are consistent with ethnohistoric observations relating to the use of fire in and around dwellings. If specific gunyah characteristics can be distinguished, we can attempt to relocate ethnohistorically recorded village locations (e.g. Thunderpurty Lagoon; Figure 8) through excavation (cf. Rowley et al. Reference Rowley, French, Milner, Milner, Conneller and Taylor2018). Such testing may deliver a viable method for the archaeological examination of potential village sites of the pre-contact period. The sedentism implied from the presence of villages can also be assessed through variations in strontium (Sr) isotope ratios in human dental enamel and dentine. With this in mind, we have started to construct an isomap for Mithaka Country. Results to date indicate a bioavailable 87Sr/86Sr range of 0.70586–0.71440, which suggests that it is possible to infer mobility patterns for the individuals so far excavated by our project at the Eight Mile site and at Glengyle Station.

Conclusions

Our overview of the archaeology of the Channel Country reveals a significant cultural landscape located at the heart of the pituri exchange network of Central Australia. Ethnohistoric accounts of Aboriginal groups in this area detail intensive economic practices associated with food production based around plant and fish resources. We have reported extensive archaeological evidence for stone quarrying, particularly for the production and trade of grindstones. The landscape reported here holds great potential to provide new insights into the nature of Aboriginal economic systems in the region and beyond. An initial age estimate on stone extraction activities of 2130±820 years (GU65.2) was obtained for the aeolian infill of a quarry pit at Ten Mile B and may tentatively be interpreted as evidence for the antiquity of large-scale quarrying in the region.

We have also considered the archaeological landscape in the context of ethnohistoric accounts of village settlements. Given that the investigation of such villages continues to be a contentious issue in Australian archaeology, we have developed a methodology that we aim to apply at several localities which have the potential to illuminate settlement structure. The remarkably intact nature of this diverse archaeological landscape requires expanded interdisciplinary investigation to understand not only the antiquity of the system, but also to address the dating of its component parts. The Mithaka cultural landscape provides an exciting and significant opportunity to obtain new insights into Aboriginal subsistence, trade and settlement. The results generated have exceeded our research expectations. It has not only provided important new information for the Mithaka relating to their ancestors, but we believe it also provides an extra dimension to debates relating to the conservation of Channel Country from the threat of new, unsustainable developments such as irrigation and gas extraction through hydraulic fracturing.

Acknowledgements

The members of the team are indebted to the Mithaka people for their ongoing support. The Duncan-Kemp family have also given strong support to the project, and the local landholders have provided access to sites and facilities during the research. Tim Blumfield (Griffith University) and Disaster Relief Australia kindly undertook drone survey of several key sites. We are grateful to Durrie and Morney Plains Stations for allowing us to base ourselves at their facilities over multiple seasons, and to the Betoota Pub for providing a base during the 2018 field season. Roland Fletcher and Peter Hiscock of the University of Sydney provided important feedback on drafts of this article. State Library of South Australia sourced the images in Figure 3 and we are grateful for their permission to use the images. Finally, we dedicate this article to Isabel McBryde, an inspiring teacher, the initiator of regional archaeological survey in Australia and collaborative archaeological research with Aboriginal people, and one of the first to dedicate serious research to Australia's unique Channel Country. Human Ethics Research Approval 2020000443 for the project ‘New bioarchaeological perspectives on pre-contact lifeways in Sahul’ was granted to the authors of this article.

Funding statement

Research was funded by a Griffith University seed grant, and funding from M.C. Westaway's Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT180100014 and ARC Linkage Grant LP170100789) covered the field expenses. We received funding from the Queensland State Government through three Looking After Country grants that supported Mithaka involvement in field research.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.31