A. Introduction

“The centre or pivot, for enabling [the monetary and credit] machine to perform.” Footnote 2

Francis Baring, founder of the English banking dynasty, on the Bank of England, 1796“Should there be a truly ‘independent’ monetary authority? A fourth branch of the constitutional structure coordinate with the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary?” Footnote 3

Milton Friedman, striking a deeply skeptical note, Testimony to US House of Representatives’ Banking Committee, 1964“Institutions [can] do the work of rules, and monetary rules should be avoided; instead, institutions should be drafted to solve time-inconsistency problems.” Footnote 4

Larry Summers, 1991“A press conference is not enough to call it ‘democracy’. I do not expect this illegitimate institution to hear my voice”

Josephine Witt, protesting at the European Central Bank’s 15 April 2015 press conferenceThose four quotations more or less sum up the debate on independent central banks over the past two centuries, and still today. Somehow, the institution of central banking is simultaneously elemental, objectionable, better than the alternatives, and profoundly alienating. For some on the political left, independent monetary authorities create a “democratic deficit.” For parts of the right, their exercise of discretionary power violates the values of the “rule of law.”Footnote 5

Meanwhile, central bankers themselves—and likewise most of their academic-economist outriders—are either largely oblivious or even indifferent to those complaints. Citing classic papers in economics by Kydland & Prescott, Barro & Gordon and others, they deem it sufficient to explain that independent monetary authorities help societies solve a serious commitment problem in macroeconomic policy and, by doing so, enhance aggregate welfare.Footnote 6

There are various problems with that myopic stance. First, even on its own terms, it fails to explain how it could be that, as Larry Summers argued thirty years ago, institutions can do the work of rules. Why isn’t the underlying time-inconsistency problem, as economists call it, simply relocated? Indeed, why do economists assume that rules themselves would be obeyed rather than broken or ignored? This is the realm of political scientists.

Second, and more prosaically, it would be naïve for supporters of monetary independence to ignore the battery of concerns when, as now, they crop up across the political spectrum and in multiple jurisdictions. If, overcoming factional rivalry, the various complainants found common cause in their distaste for discretionary technocracy, the upshot could be substantive legislative reform or, alternatively, less visible actions that diluted the political insulation of today’s central banks. This is the realm of legislators and lobbyists.

Third, and at a higher level, it is hardly for unelected central bankers to self-legitimate by esoteric declaration. These are issues in constitutionalism. They are neither confined to the mysteries of central banking, nor beyond the ken of citizens. Indeed, the big issue is whether governmental commitment devices can be squared with the values of representative democracy. That is the realm of constitutional theorists and jurists, and it is the subject of this Article.

Plan of the Article

The Article has six parts. By way of background, Section B opens with an account of why people across the world are becoming uneasy about independent monetary authorities. This partly reflects the extraordinary reach—in domain, and purpose—of their balance-sheet policies. But their power goes beyond even an expansive interpretation of monetary policy, extending to banking regulation, which involves making and applying legally binding norms. In consequence, debates about central banking cannot be divorced from wider concerns about the democratic legitimacy of the regulatory state as a whole.

That sets the scene for the core of the Article’s constitutionalist analysis in Sections C–E, which proceed by steps towards a set of Principles for Delegation to independent agencies insulated from day-to-day politics. Starting with a stripped-down benchmark model of constitutional government in which legislatures produce laws that are interpreted and applied by independent courts, Section C explains why the elected executive emerges as a policy-making arm of government rather than acting as a mere cipher for a detailed legislative code.Footnote 7 But elected politicians exercising discretion in developing and applying policy opens a problem of credible commitment, impairing welfare. That can be mitigated by delegation to politically insulated agencies, but only at the cost of a different set of problems: Handing policy to unelected officials jars with our democratic values. Section D seeks to reconcile institutionalized commitment devices with constitutional democracy. Given the availability of a menu of choices for promoting credibility with differing degrees of formal entrenchment, there is a spectrum of commitment technologies that can be accommodated within constitutional government, with each type needing to be designed carefully in order to comport with our deep political values. Section E addresses how to do that for the particular case of independent agencies, summarizing the Principles for Delegation that, in healthy democracies, should frame delegation to agencies insulated from both elected branches.

The ground clearing complete, Sections F and G apply our constitutionalist values and the Principles to modern central banking, revisiting the quotations at the head of the Article from Baring, Friedman, Summers, and citizen Witt in the course of doing so. Section F reveals that, compared with most other independent agencies, there is something distinct about the constitutional position of an economy’s monetary authority given the higher-level separation of powers. After underlining the inalienable linkages between price stability and banking system stability, it outlines the components of a modern Money-Credit Constitution that would constrain both central and private banking. Section G concludes with where all this leaves the European Central Bank (ECB), given its new prudential powers and the incompleteness of the EU’s economic constitution—which does not provide instruments for sustaining its own existence.

B. Central Bankers as the Only Game in Town

If asked what a central bank is, many people would answer that it is the body that controls the money supply. Of course, that is correct in so far as a central bank can either directly set the supply of its own monetary liabilities or, alternatively, indirectly steer demand for money via an interest rate that it establishes by acting as the marginal lender and/or borrower of overnight money. But technical descriptions of that kind can all too easily obscure the extraordinary powers of central banks.

I. Quasi-Fiscal Capabilities

I will give just three generic examples of those capabilities.

First, by supplying more money than either demanded or expected, the monetary authority can generate surprise inflation, which redistributes resources from lenders to borrowers: In other words, like a tax. Second, by providing the economy’s final settlement asset, the monetary authority becomes banker to the banks, meaning it is the liquidity re-insurer for both the banking system and the economy as a whole, with powers over commercial life or death. And, third, by conducting financial operations of various kinds, the monetary authority changes the structure and, sometimes, the size of the state’s consolidated balance sheet.

That third capability needs a little elaboration. If a central bank buys—or lends against—only government paper, its operations alter the structure of the state’s consolidated liabilities but not their size, with monetary liabilities substituted for longer-term debt obligations. If it purchases—or lends against—private-sector paper, the state’s consolidated balance sheet is enlarged, its asset portfolio changed, and its risk exposures affected. In either case, any net profits or losses flow to the central treasury. Where losses are incurred, the result is either higher taxes or lower spending in the longer run—and conversely for net profits.

We are, let’s be clear, talking about bodies with quasi-fiscal powers.

II. Central Bank Independence

It is hardly surprising, then, that the history of central banking is not just a story in monetary economics but also one in the design of modern government.

The 19th century resolved this by formalizing a particular version of what I shall call a money-credit constitution. It was based on the gold standard, a device employed by property-based political systems to ensure that their currencies maintained external convertibility and stability. As full-franchise democracy became the norm in the early-20th century, however, the volatility entailed in domestic output and employment was no longer politically sustainable. Instead, the public wanted price stability to come in harness with measures to smooth the business cycle.Footnote 8

After World War II, for a while this was attempted via the hybrid international monetary system known as Bretton Woods, under which European currencies were effectively pegged to the US dollar, and the dollar was pegged to gold. But when, under the weight of US fiscal profligacy and monetary incontinence that took hold during the 1960s, that regime first buckled and then broke in the early-1970s, forcing the world’s major economies onto fiat money systems—for the first time in modern history outside major wars. Precisely because this restored domestic monetary sovereignty, it presented the problem of how politicians could be deterred from abusing the monetary power.

Independent central banks emerged as the solution: First in Germany and Switzerland, then in the US through the heroic restorative role of Paul Volcker in the 1980s, and then gradually elsewhere in Europe. The initial effort at redesign remained incomplete, however, until after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008/09—and perhaps still does.

Two generations ago, in many countries—perhaps notably Britain and France, but even in the US—the central bank was viewed as an operational appendage of the finance ministry, albeit inhabiting a distinct sphere of expertise. Its functions were determined by technocratic comparative advantage rooted, as Francis Baring observed two hundred years ago, in its being the pivot of the payments system, imbuing it with a degree of pragmatic authority among the banking community. By that, I mean the authority of a body recognized as capable of providing solutions to collective-action problems, notably by acting as the lender of last resort when basically sound banks will not lend to each other for fear that their peers are unsound.

Today, by contrast, most advanced-economy central banks would probably be viewed as independent government authorities that are formally delegated specific responsibilities and insulated from day-to-day politics, which I call delegation-with-insulation. In terms of Max Weber’s categorization of legitimation principles, this marked a shift from authority grounded in tradition to rational-legal modernity.Footnote 9

In that reconfigured existence, contemporary central banks are supposedly set up to do only those things that have been formally delegated to them. That leads to normative debates about where the boundaries should be drawn, and to positivist debates about where they are as a matter of law. One example of the former is whether they should be involved in banking supervision; in the UK, the Bank of England’s historical responsibility for banking soundness was transferred elsewhere when, in 1997, it was finally granted monetary policy independence, only to be returned after the financial system collapsed in 2008. Another, topical normative issue is whether, faced with climate change, central banks should substitute for inactive governments in taxing businesses that pollute the atmosphere. To date, the most noteworthy example of vires challenges has been the series of court cases concerning the legality of some ECB market operations and facilities.

As the GFC revealed, however, underlying tensions between these two modes of existence —customary authority versus legislated delegations—remain latent when the zone of naturally endowed authority and technical capability is broader than the mandated zone of formal legitimacy. The longstanding debate about whether central banks can be or should be bank supervisors —a struggle that worked its way through the EU’s courts —should be seen in that light. So should the question of whether the gigantic purchases of government bonds by central banks (notably the Federal Reserve and Bank of England) in March 2020 are properly viewed as regular monetary policy (stimulating aggregate spending), unscripted market maker of last resort operations, or emergency financing for governments trying to cope with Covid-19.Footnote 10 In both cases, the roots lie in questions of power and durable constitutional design, not only in what institutional structure will deliver the best results for citizens’ welfare.

III. From Impotence to the Only Game in Town

So where do we find ourselves today?

Compared with the aftermath of the banking crisis, monetary disorder and economic slump of the 1920-30s, when central banks were stripped of authority, standing and power, things could hardly be more different. Central bankers generally emerged from the global financial crisis with more responsibilities and powers. Internationally, macroeconomic recovery seemed to depend on them. They became, in a popular but deeply troubling phrase, the only game in town.

Since financial markets broke down in the summer of 2007, central banks have used their balance sheets to intervene in almost every part of the bond and loan markets, initially in 2007/08 in order to contain market disorder, later to stimulate economic recovery, and during 2020 for myriad purposes ranging from propping up finance to funding government. Even before Covid-19, discomfort became evident on many fronts: In legal challenges against the ECB in Europe’s constitutional courts, in US litigation around the US bailout of the insurance conglomerate AIG, and in political steps in the US Congress, from both sides of the aisle, to reform the Federal Reserve.

But that was not all. After the 2008 crisis, as well as exercising their latent balance-sheet powers in novel ways, the central banks accumulated more formal powers. Banking supervision was granted to the ECB, and returned to the Bank of England, giving each some rule-writing powers and a more potent seat at the regulatory table—the EU’s European Banking Authority. In the US, the Federal Reserve now supervises and can issue rules binding those non-bank financial groups judged to be systemically significant. Additionally, central banks in many jurisdictions, including the Euro area and the UK, were granted what are known as “macro-prudential” powers to mitigate threats to stability from credit booms, such as temporarily raising equity-capital requirements.

In terms of the distribution of administrative power, the practical upshot of this reversion to and elaboration of past orthodoxy is that central banks no longer inhabit the rarefied zone allotted to them by 1990s orthodoxy, in which monetary-policy specialists were to smooth macroeconomic fluctuations without taking much interest in the financial system. In a massive development for modern governance, their newly fortified powers to oversee and set the terms of trade for banking and other parts of finance unambiguously make them part of the “regulatory state”—a distinctive part of the modern state apparatus that developed during the 20th century, first in the US and later in Europe, leaving public law playing catch-up.

For some of the most fervent advocates of monetary independence, including in Germany, this risks taking central banks into more overtly political waters, jeopardizing the hard-won achievements of the 1980s and 1990s. For those always uncomfortable with the independence of central banks, it adds to their unease about a “democratic deficit.” Concretely, if central banks are to be independent, it must now be on two fronts: not only from quotidian politics but also from the City of London, Wall Street and the Frankfurt bankers and asset managers. And, partly to warrant that insulation, they must, somehow, be transparent and accountable across the whole gamut of their powers and roles.

More profoundly, under the post-crisis dispensation, deliberations on the legitimacy of central bank independence can no longer be bracketed away from what previously were largely orthogonal concerns about a regulatory state empowered to write and issue rules that are legally binding on citizens and businesses.Footnote 11

IV. The Regulatory State’s Democratic Legitimacy Problem

That means confronting deeper, higher-level questions about the legitimacy of delegating power to unelected officials. In our representative democracies, this places power two steps away from the people, whose elected representatives have voluntarily surrendered much of the day-to-day control they traditionally exercised over the bureaucracy, but who do not get a chance to vote themselves on the technocratic elite now governing much of their lives. Have no doubt, today, most obviously in the United States but also in Europe, the marginal law-maker is often an unelected technocrat or judge.

Grappling with these difficult issues is necessary to answer the following questions:

-

Should central bankers be allowed, as regulators, to issue legally binding rules and regulations?

-

Should they have statutory powers to authorize and close banks?

-

Could any such powers decently extend to other parts of the financial system?

-

Should they be free to decide when to provide liquidity assistance to distressed firms?

-

Should they be free to use any such powers to steer the supply of private and public credit to combat climate change, inequality, and other existential or social ills?

-

Should monetary policy and other central banking functions be subject to different standards of judicial review?

The answers—and I will provide only some of them here—cannot turn purely on what central bankers might be good at, or on whether elected politicians would like to hide behind them. If, for example, our political values were to dictate that only elected legislators should set legally binding rules or taxes, then those powers could not be conferred upon central banks—so long as they remained independent. Similarly, if only judges should make adjudicatory decisions, then central banks should not make supervisory decisions, instead being restricted to making formal recommendations to the courts. And if, as some argue, combining the writing of regulations with adjudicatory powers violates the “separation of powers” at the heart of constitutional government, how much worse when combined with the quasi-fiscal capabilities of central banks.Footnote 12

C. Executive Branch Policy-Making and Commitment Devices

If that is the problem, we now proceed by steps towards a principled account of the place of independent agencies in the government of constitutional democracies. It is the central proposition of this Article that an account—or theory—of this kind is necessary if the judiciary and parliaments are to find a tolerable and sustainable way through the thicket of challenges to delegation-with-insulation.Footnote 13

I. Courts Versus Administration: Rule-of Law and Democratic Values

Stepping back, the benchmark case of modern administration is a detailed code which is passed by an elected legislature and applied, case by case, via the courts. Where technical expertise is needed, the adjudicators can be specialist judges, subject to judicial review by generalist courts. Departures from that benchmark need to be justified.

In doing so, we do well to remember that not all laws come through legislation. In adjudicating legal disputes amongst citizens, the judiciary articulates principles along the way. And in applying statutory law, the judiciary has to interpret and construe: It decides what legislation means and/or the boundaries of its reasonable application. In one sense, this reveals the obvious point that judges make law. Law-making is not a monopoly of the legislature.Footnote 14

The crucial point is that, in order to maintain consistency and generality, adjudication, whether in the hands of courts or specialist regulatory agencies, entails an accretion of principles. A series of adjudicatory decisions generates something like an implicit rule or general policy.

By the early 1960s, prominent US legal scholars and justices were making just that point. Judge Henry J. Friendly expressed concern that the regulatory standards applied via agencies’ adjudicatory decisions were not “sufficiently definite to permit decisions to be fairly predictable and the reasons for them understood,” and went on to prescribe that “the case-by case method should … be supplemented by greater use of … policy statements and rulemaking.”Footnote 15

Those arguments are rooted in some of the values of the rule of law. Our democratic values take us in the same direction but throw up a serious constraint.

There are some fields where, it seems, we want regulation to proceed via the open promulgation and debate of systematic policy rules rather than the accretion of adjudicatory precedent. While the elected executive branch and agencies of all kinds, independent or not, can act like elected legislators by consulting on planned policies, courts do not, and cannot, consult the public on their principles and precedents. Judicial law-making—very obviously in the common-law tradition but also via the role of non-binding precedent in civil-law jurisdictions—is in its essence incrementalist, developing and refining principles through a stream of individual cases, each with their own specific circumstances but linked by common threads that gradually emerge and which judges discern and enunciate.

Moreover, in some fields we want our regulatory policymakers to explain and defend their policies publicly and to the legislature, whereas we do not want our judges to be compelled to explain themselves to legislators.

In summary, given our democratic values of participation and accountability, regulatory policy-making by the executive branch is preferable where society desires consultation on the evolution of a systematic public policy, and wants to keep both the regime and the exercise of delegated power under public review.Footnote 16

II. Politicized Executive-Branch Regulatory Policy-Making

But that argument does not make a case for regulatory rule-making occurring beyond the day-to-day control of the elected executive branch. In fact, the writing of legally binding rules is typically regarded as a function that, in a democracy, requires not independence from elected representatives but, rather, their active involvement—or at least their oversight.Footnote 17

In consequence, the notion of regulatory law-making does not obviously threaten our political values where the regulator is under the day-to-day control of elected politicians. And, arguably, it is not a great problem where, even if not exercising hands-on day-to-day control, elected politicians at least retain levers that give them real influence over the development of regulatory policy. Such agencies fit with the standard analysis of principal/agent relationships. The agent must, when making decisions, either consult their principal or ruminate on what their principal wants—or would want if in possession of the same information and expertise.

By contrast, what we call independent agencies are largely insulated from the day-to-day politics of both the executive branch and the legislature, because their policymakers have job security, control over their policy instruments, and some autonomy in determining the organization’s budget.Footnote 18 That is a reasonable description of many modern central banks, and of some regulatory bodies. They can be thought of as trustees: free to set and deploy their delegated powers, including in unpopular ways, so long as they are true to their legislated mandate and stay within their legal constraints.

III. The Centrality of Credible Commitment to the Warrant for Independent Agencies

The warrant for such delegation-with-insulation is, I want to argue, the welfare benefits that can be obtained by enhancing the credibility of the delegated policy goal—credible commitment.Footnote 19

This problem—of making promises that will be believed—crops up across much of government. It arises wherever the effectiveness of a policy choice today depends on others’ actions and, in particular, their expectations of future policy. If people act on an expectation that a promise could be broken, it can prove too costly for government to stick to its promise. For example, by living in the floodplain households might force government to break a pledge not to build expensive infrastructure preventing floods. Symmetrically, if a monetary authority is liable to exploit price stability to generate more economic activity in the short run, households and firms will factor that into wage and price-setting, leading to permanently higher inflation. The expectation of a broken promise becomes self-fulfilling.

This poses two questions about delegation to politically insulated agencies: under what conditions might it work, and does it violate our democratic values?

The first is implicit in Larry Summers’ statement, quoted at the head of the Article, that institutions can do the work of rules. That will be so only if (a) legislators incur some costs from repealing the delegating legislation, and (b) unelected agency heads reap personal returns from delivering a clearly specified mandate, such as professional and public esteem—which, intriguingly, connects an avowedly Welfarist analysis with a modern-day version of the old republican idea of honor.Footnote 20

If, however, the delegated objective is vague or cannot be monitored for some other reason, the unelected policy maker is not constrained. Similarly, if the agency’s policy makers do not care about their reputation or the society is not capable of bestowing esteem, a well-specified mission will not act as the intended constraint. But where the necessary conditions are satisfied, independent agency heads are more likely to stick to a well-specified mandate than politicians seeking re-election. This is all about what political scientists call audience costs—and benefits—and is motivated entirely by the pursuit of aggregate welfare.

But if institutional devices such as delegation-with-insulation could, in principle, overcome commitment problems, the question at the heart of this Article is how they can possibly be squared with democracy.

D. Reconciling Commitment Devices with Democracy

The idea of commitment devices is hardly foreign to our constitutional history. As far back as the 16th century, French political theorist Jean Bodin, famous for his advocacy of a strong sovereign, held that a wise sovereign would buttress and enhance his/her powers by tying their hands in various ways, such as ruling within the law and in line with established custom.Footnote 21 But the monarch’s motives are almost as self-regarding as those of Odysseus when he orders his crew to tie him to the mast but plug their own ears so that he alone can hear the music of the sirens.Footnote 22

Surely, the advent of democracy alters the normative calculus. The benefits of commitment can no longer accrue solely to a ruler or ruling elite, but must be held in common by citizens. Indeed, the “democratic deficit” that some argue contaminates delegation to independent agencies, and therefore their authority, is typically seen as arising because policy making is removed from the people’s accountable elected representatives. If democracy gives the people the right to change their minds about what they want (ends) and about how to go about obtaining what they want (means), commitment devices seem to be out of order. They are anti-democratic or, as Americans might put it, counter-majoritarian—a term coined half a century ago by legal theorist Alexander Bickel to characterize the challenge presented by a supreme constitutional court that can strike out acts of the elected legislature.Footnote 23

There appears to be a paradox here. On the one hand, delegation is designed to help the democratic state deliver better results by sticking to the people’s purposes: In that sense credible commitment is enabling of democratically generated purposes. On the other hand, the people have to remain free to change their purposes. The resolution has to be either that there are some commitment problems where democracy, as ordinarily understood, should be suspended or, alternatively, that institutional technology designed to enable credible commitment cannot be absolute.

I. The Independent Judiciary as a Commitment Device

We can find some illumination from the independent judiciary’s role as both impartial adjudicators and unelected law-makers.

As citizens, we want to be assured that the law will be applied consistently to different cases in the interests of fairness. This too is a question of commitment: To cross-sectional consistency rather than the dynamic consistency intrinsic to the monetary-policy problem.Footnote 24 It does not turn on the regime itself delivering substantive justice in everyone’s eyes, but rather on everyone being confident that, within the terms of the law, they—groups as well as individuals—will be treated in the same way: According to the same criteria, with their particular circumstances having a systematic effect rather than an arbitrary effect on policy choices. It provides a normative justification for delegating the adjudication of legal disputes to an independent judiciary.

Imagine a world without that separation of functions. If someone said, “I promise not to take my interests and personal goals as a legislator into account when adjudicating specific cases,” we would doubt either their sincerity or their capacity to keep their promise. It would not be a credible commitment.

An independent judiciary helps to solve the commitment problem because their standing—even their sense of identity—rests, in significant degree, on maintaining a reputation for impartiality among their professional group and the wider public. In the jargon, they face “audience costs” if they are not seen to exercise their judicial powers impartially.

II. Law Itself is a Commitment Device

In fact, law itself can, and I believe should, be thought of as a commitment device. Otherwise, government officials could turn up for work each morning and shift policy about, this way or that, however they chose. Some of the more formalist values of the rule law—generality, transparency, predictability, avoiding capricious change, and the promulgated law actually being the law enforced, and so onFootnote 25—are attributes we should associate with seeking to make credible a commitment to maintain a stable policy generated through stable processes.

Thus, legislated law is open to change only via formal amendment or repeal, and politicians are exposed to audience costs if those procedures are set aside. Up to a point, the same can be said of judge-made law, because the demands of precedent and giving reasons create audience costs for rogue judges amongst the community of lawyers.

III. Commitment and Democracy’s Rules of the Game

Those, however, are both liberal institutions and ideas: Law adjudicated and applied by an independent judiciary. They show that, intrinsically, institutionalized commitment devices are not deeply alien to constitutional democracy. But what about the democratic part of liberal democracy?

Compared with Bodin’s world, modern constitutionalism delivers a degree of symmetry. Politicians and party functionaries—the political system’s elites—continue to embrace arrangements that tie the hands of government somewhat. Meanwhile, the people allow themselves to be bound by acquiescing in general elections being held only infrequently, reducing their popular power.

Left intact across that leap of time is a distinction between the ‘rules of the game’ for politics—constitutional norms and conventions—and public policies determined by or within politics— or, more accurately, quotidian politics.Footnote 26 The former cannot be subject to continuous or capricious change without the consequent uncertainty undermining the practice of politics as a means of addressing the problems and challenges of living together in political communities. A degree of collective-self-binding around the modalities of government is necessary for democracy to have any meaning, including preserving it for tomorrow. This was a point powerfully made by James Madison in response to Thomas Jefferson’s hankering after a new US constitutional convention every 20 years or so, one for each new generation.Footnote 27

Even within those meta rules of political procedure and conduct, there is an important distinction between mechanical rules and rules requiring interpretation. While there are certainly examples of the former, such as the US Constitution’s provisions that a presidential term lasts four years and that no person may serve more than two terms, many rules of democratic and legislative procedure involve interpretation or judgment in their application, requiring a second-order rule determining, mechanically, who has the final say. The overriding goal and norm is that those interpretations-cum-applications remain highly stable, while not necessarily being immutable.

The arguments for stability are different when we turn to what is decided within politics, such as, for example, some substantive legal rights and the outputs of the security, services, fiscal and regulatory arms of the state. If one purpose of democratic politics is to allow for collective choice, that includes making choices on what, if anything, to put beyond simple majoritarian processes and what to leave as part of ordinary politics.Footnote 28

On that line of thought, we might see the following hierarchy of candidates for binding commitment:

1) Mechanical rules on the structure/procedures of politics

2) Institutions for applying interpretative rules on the structure/procedures of democratic politics and government

3) Institutions for applying interpretative rules to any “fundamental” or “basic” rights beyond democratic political rights

4) Institutions for adjudicating legal cases under—and with the final word on the meaning of—the ordinary law

5) Public-policy commitments.

Together, the first four categories show that embedding institutions as a commitment device is not alien to democracy, per se. Political communities seek stability in (1) and (2) because they structure politics itself, including a democratic polity being committed to remaining democratic; in (3) as a commitment to certain liberal values; and in (4) as part of a commitment to fair adjudication in the application of the law. All four categories might seem fundamentally different in kind from (5), concerning, as they do, the institutionalization of constraints on democratic power according to the values of the rule of law, liberalism, and constitutionalism.

IV. Commitment and Democratic Public Policy

It would seem odd, however, to hold that even where the elected assembly stays within those constraints, it should not be free to put obstacles in its own way so long as those obstacles are not insuperable and do not violate a constitutional democracy’s deepest political values.

Yet, that is the argument advanced by some US legal scholars: That Congress should not be permitted to create independent agencies or delegate rule-making powers.Footnote 29 Never mind fringe US opinion, in Germany the Basic Law itself, which unusually among advanced—economy constitutions makes explicit provision for the administrative state, effectively stipulates that all domestic-law agencies must be, and so are, subordinate to the relevant minister.Footnote 30

But my question is not whether, as a matter of law, independent agencies are Constitutional in any particular jurisdiction, but whether they could be squared with the constitutionalist values that the major democracies share. More specifically, we need to ask whether the values of constitutional democracy are violated if one generation of elected legislators seeks to raise the costs to their successors—or, indeed, to their future selves—of departing from their preferred policy. The argument that there need not be a violation turns on what could seem to be a paradoxical tension within democracy itself. On the one hand, for some people the warrant of democracy lies in its capacity to produce better outcomes for public welfare. On the other hand, the very structure of representative democracy has inscribed into it a risk that elected politicians deliberately deliver poorer results than they had promised when standing for election.

For example, if we hate credit booms after they have burst, that is often forgotten when only a few years later easy credit and rising property prices once again lure us back into debt. It is a brave, and so rare, politician who puts their re-election prospects at risk by taking away the punch bowl while the party is swinging away. We, citizens, are unavoidably exposed to the risk of our representatives’ responsiveness to our apparently volatile preferences morphing into an endemic short-termism that depletes our aggregate welfare.

That being so, we need to escape from thinking that the hazards of our system of government are confined to (a) extra-legal measures that can be remedied via the courts and (b) policy failures that can be remedied via the ballot box. Neither of those checks and balances can suffice where all political parties competing to govern have incentives to renege on a substantive promise (for example, low inflation) and, further, the social costs of their doing so are liable to be long-lasting because they become embedded in people’s expectations and behavior. Those are serious misuses of power.

V. Commitment Technology Without Constitutional Entrenchment

Seen thus, the key question about public-policy regimes is not whether goods like price stability, financial stability, the protection of investors or environmental protection should be regarded as almost unqualified rights ranking with, for example, the right to vote in free and fair elections or any right to free speech. Nor is formal Constitutional codification the only way of embedding a policy regime. Other, lesser commitment devices are available.

In fact, representative democracy gives our politicians a menu of devices for making their breaking of promises more or less visible, and more or less costly to themselves. Elected legislators can seek to bind themselves by legislating in ways that create heightened audience costs if policy departs from what was promised. Legislating the objective helps. Delegating to an independent agency rather than to the civil service—or to an executive agency beholden to ministers—ratchets up the transparency of attempts to alter the course of policy for short-term electoral gain. While the institution of the civil service is itself a commitment device—to the integrity of the administration of policy—it is not, and is not meant to be, a device for committing to a stable policy.

Delegating to independent agencies is, in short, a mechanism for elected representatives to safeguard those areas of policy where they wish to secure a public good but recognize that they cannot commit to doing so if they retain ongoing control. Instead, by appointing an unelected trustee with a monitorable mandate, parliamentarians can seek to generate a normative public expectation that the agency will stick to the mandate rather than seek to improve upon, or otherwise depart from it. The mechanism is not idealistic but relies upon harnessing the self-regard of technocratic policy makers. Whereas elected politicians will nearly always prioritize whatever short-term measures help get them re-elected, technocrats can be highly sensitive to their professional reputation and standing.

By using ordinary legislation to delegate a clear mission to an independent agency, elected legislators specify and retain ultimate control over a policy regime—because, formally, it can be amended or repealed—while putting obstacles in their own path: Exposing themselves to the political costs of over-riding or repealing a policy regime which they made a public fuss about insulating. This will work as a commitment device only where it is also normatively warranted, which includes retaining broad acceptance across the political community. Without that, the audience costs of the legislators reneging—by repealing or gutting the legislation—or of the agency’s policymakers going rogue, by pursuing a different objective, do not kick in. Under modern democracy, credibility and legitimacy come bundled together, and the key ingredient is transparency: Being able to observe both the legislators’ formal acts, and the agency’s exercise of its delegated powers.

VI. Independent Agencies as Rule-Writers: Legislative Self-Binding

We can now revisit the question of whether independent rule-writing regulators violate our democratic values. The grounds for credibly committing to impartial adjudication of disputes via the institution of an independent judiciary are provided by the fundamental value of avoiding abuses of power. I have argued that, in democracies, we might also sometimes want to guard against misuses of power, meaning the deployment of power in ways that are not illegal but profoundly let down the public, leaving them less well-off and exposed to avoidable risks.

While, for economists, the classic examples of time-inconsistency problems might concern price stability and utility regulation, the underlying problem of making credible commitments can infect the legislative process itself.

Imagine, as if we need to, that there has been a major financial crisis and, further, that there is very broad support for a major overhaul of the regulatory regime. Imagine too that this is going to take some years to develop: Not because legislators have other current priorities but rather because, even though the broad direction of and standard for policy has been determined, a huge amount of thinking is needed on the detail. The expected length of the process is not driven by legislators’ incentives or their lack of technical expertise but by the underlying substance. It would take anybody years—as, indeed, it has. Because it will take years, legislators worry about whether their resolve, and that of their factional backers or the public at large, will hold as memories of crisis fade and the short-term allure of easy credit and asset-price inflation reasserts itself. Conscious of that risk—that their preferences will buckle and bendFootnote 31—the legislators decide to bind themselves to the mast by delegating to an independent agency the job of filling in the detail of the reformed regime.

Compared with standard explanations offered by political scientists, this is not a case of legislators seeking to shift blame, being inexpert, lazy or time constrained—true though all that might be. It is a case of legislators employing delegation as part of an effort to commit to their own high policy.

Crucially, they have not tightly bound their successors—or their future selves—because they cannot. But they have established a structure that makes any such backtracking more visible—to commentators, the public, and the world. Under the delegated structure, future legislators must pass legislation to override the independent agency’s rules, amend its mandate or abolish it altogether. Each requires only ordinary legislation, and is well within their constitutional rights, but each is highly visible and so can increase the political costs of bending to special interests or yielding to transient temptations.

What, though, are the pre-conditions for delegating to independent agencies other than the desire to employ a commitment device? We need to answer that question before returning to central banking, where my eventual purpose is to show, in Section F, that democratically warranted pre-conditions for bestowing great power on independent agencies are not completely satisfied by the ECB.

E. Delegation Principles for Independent Agencies

The key output of “Unelected Power” is a set of concrete precepts, proposed as political or constitutional norms for healthy constitutional democracies, constraining the delegation of discretionary power to central banks and other formally independent agencies. They were arrived at through an attempt to take seriously the values of the rule of law, constitutionalism, and democracy.

I. A Legitimacy Robustness Test

Values are part of the fabric of a political community. While it is prudent to think about the performance of office-holding individuals as being shaped by incentives, it would be reckless to think about institutional design without bringing in values, because societies tend to evaluate institutions partly through their values. To live by a norm that people should not passively resist or actively seek to undermine the system of government, and for that norm to endure in the face of shocks and disappointments, the institutions of government need to square with a political community’s deep values.Footnote 32

As the late Bernard Williams put it, it is legitimacy for us “now and around here” given our particular convictions about, commitments to, and ways of living with democratic governance. In other words, legitimacy given our history.Footnote 33 This is subtly but importantly different from Weber’s account of legitimacy in terms of belief pure and simple. As the British social scientist David Beetham put it a quarter of a century ago:Footnote 34

A given power relationship is not legitimate because people believe in its legitimacy, but because it can be justified in terms of their beliefs. This may seem a fine distinction, but it is a fundamental one.

Not only might the conditions for legitimacy vary across time and place, but there might also be variations, at least of emphases, within a political community. As such, a system of government can be legitimized without each and every person’s allegiance being explicable in identical terms.

Accordingly, any set of Principles for Delegation to independent central banks and other independent agencies must satisfy the following test: Are they robust to the different reasons people have for going along with the legitimacy of representative democracy, as reflected in public debate and discourse? In consequence, a set of delegation principles must not wilt when confronted by various real-world approximations of mainstream political theories: Elite-majoritarian democracy, interest-group liberalism, republican democracy, and deliberative democracy, and so on. Each generates its own set of requirements.

Perhaps most significantly, this means a policy regime delegated to an independent agency must live up not only to liberal values policed by the modern judiciary but also to our republican values. Thus, if the instrumental purpose of delegation to trustee-agencies is to help the democratic state deliver better results by sticking to the people’s settled purposes, then the people’s purposes had better be known, and determined by some process that has deep legitimacy. That is exactly the role of democracy’s procedures.Footnote 35

In a similar vein, we should avoid delegating power to an agency with a single policy maker, not just because open committee discussions among equals can produce better results, but also because concentrated power is alien to our traditions of government.

II. The Principles for Delegation

To summarize, then, just a few of the Principles for Delegation:Footnote 36

1) Such independent agencies should pursue a mission that enjoys broad public support.

2) Above all, they should have clear, monitorable objectives set by elected representatives of the people.

3) They should not be given mandates or powers that entail making big distributional choices or big value judgments on behalf of society.

4) They should make policy in committees, comprising members with long, staggered terms, which they are expected to serve; and operating via one person-one vote.

5) Their policy choices should not interfere with individual citizens more than warranted to achieve their statutory purpose— proportionality.

6) The provisions of such delegations should, in the usual course of things, be laid down in ordinary legislation, and only after wide public debate; and they need subsequently to become embedded through ongoing public familiarity and support— prescriptive legitimacy.

7) Governments and legislatures should articulate in advance, and preferably in law, how, if at all, an independent agency’s powers to intervene in an emergency could be extended, but any such extensions should not compromise the integrity and political insulation of its core mission.

8) There should be sufficient transparency to enable the stewardship of delegated policymaker and, separately, the design of the regime itself to be monitored and debated by elected representatives. In particular,

○ The agency should publish principles for how it plans to exercise discretionary powers within their legal boundaries

○ It should publish data that enables ex post evaluation of its performance, and research on the regime.

9) An independent agency should be given multiple missions only if:

○ they are intrinsically connected, each faces a problem of credible commitment, and combining them under one roof will deliver materially better results.

○ each mission has its own monitorable objectives and constraints.

○ each mission is the responsibility of a distinct policy body within the agency, with a majority of members of each body serving on only that body and a minority serving on all of them

○ each exercise of powers can be transparently allocated to a particular purpose or mission.

10) The legislature should have the capacity, through its committee system, properly to oversee each independent agency’s stewardship and, separately, whether the regime is working adequately.

11) The agency should be independent of any industry it regulates. And beyond the parameters of the formal regime, an ethic of self-restraint should be encouraged and fostered.

Of these, (3), barring big value judgments, and (9), on combining multiple missions, will be especially important for our discussion of central banks in Section F, and so to where we end up on the ECB and the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) in Section G. But, first, some more general points need to be made about the role of the courts in invigilating this area of public law, and about the proper place of independent agencies in emergencies.

III. Statutory Interpretation

Because such trustee-type independent agencies exist as a means to commit to a well-articulated public policy purpose and objective, their statutory powers should be interpreted, by the courts, and so by the independent agencies themselves, purposively; and where an ostensibly clear objective leaves ambiguity, with the overall grain of the statutory scheme. That is because the legitimacy of the delegation depends on the intention of credibly committing to a legislated purpose and on constraints that, accordingly, bind the agency to that purpose.

This norm of statutory interpretation would mean that an agency should desist if a proposed measure might at a stretch be within the law on a textualist analysis of the statute but could not reasonably be viewed as aimed at pursuing the agency’s statutory purpose.Footnote 37

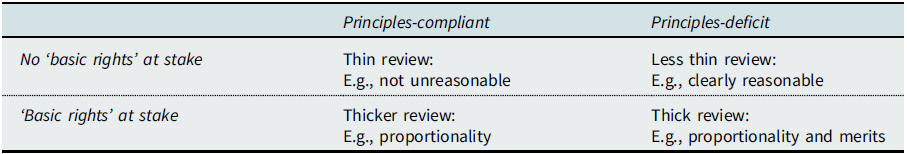

IV. Standards of Judicial Review

Staying with the judiciary, I want to argue that compliance with the Principles, or something like them, should influence the intensity of judicial review of independent agency decisions and actions. Specifically, the intensity—or standard—should increase with the extent to which a policy regime delegated to an independent agency falls short of the Principles, entailing a democratic deficit, and also with how far the challenged actions cut across basic liberal freedoms. Thus:

Table 1. Standards of Judicial Review

A Principles-compliant independent agency with multiple instruments would (a) be constrained by the law to choose the instrument least invasive of individuals’ freedom—taking into account any legal rights furthered by the action—but would (b) face a lower test—unreasonableness or irrationality—in determining whether that action was needed to achieve its statutory objective and in calibrating the instrument employed. While the former amounts to a ‘check’—and could give courts an incentive to unearth new “rights”—the latter reflects the value of institutional ‘balance’, with the courts respecting the fact the mandate was given to the independent agency— not to the judges—by democratically elected legislators.Footnote 38

Meanwhile, for a non-compliant independent agency enjoying insulation from politics without appropriate constraints coded into the delegated regime, more intense judicial review would give them, and conceivably legislators, incentives to remedy the regime’s flaws assessed against our democratic values.

So, unlike some others, I am not distinguishing between different types of policy activity per se—for example, between the monetary policy decisions and prudential stability decisions of a multiple-mission central bank.Footnote 39 Instead, the stress is on democratic pedigree, and types of effect. Thus, faced with a potentially destabilizing credit boom, a multiple-mission central bank (operating a Principles-compliant regime) would not be incentivized to turn immediately to monetary-policy measures simply because more intense judicial scrutiny would apply to regulatory interventions, because each type of measure would, instead, face the same broad standard of not being unreasonable or irrational.

V. Emergencies

That, by and large, concerns normal circumstances. What, though, of emergencies? It is useful, under almost any form of constitutional government, to think of a ‘crisis’ as being highly adverse circumstances for which the machinery of the state is not formally prepared, lacking the powers or capabilities to cope. Government is forced to innovate and improvise: Taking new powers, using existing powers imaginatively, or declaring an emergency in order to activate some latent powers. In a constitutional democracy, the question is who may do so—legally, and without violating our values.

The Principles for Delegation side step the deep and vexed question of how far, if at all, the elected executive might go in acting beyond its legal powers, but are clear that independent agencies should not do so. Further, I suggest that independent-agency policy makers should ensure that they have some kind of informal political acceptance where, faced with an emergency, they plan to act within their legal powers, properly understood, but in ways that have never remotely been contemplated by legislators or the general public.Footnote 40

All this underlines the vital importance of mandating extensive within-regime contingency planning and, most of all, the imperative of planning for elected policymakers to be involved in any resetting of policy goals or powers during a crisis. How this plays out in practice will be highly sensitive to local constitutional structures and political conventions, but the basic principle of unelected agencies not remaking themselves should be clear. This has important implications for central banks and, perhaps especially, the ECB analyzed in Section G.

VI. The Principles for Delegation as Constitutionalist Social Norms

That summary makes clear that the Principles for Delegation are putative norms guiding the structure and operation of part of the administrative state, and so are an example of constitutionalism conceived as establishing “rules that determine how a practice or institution is organized and run.”Footnote 41 The Principles seek to regulate the distribution of day-to-day power between elected politicians and unelected state technocrats, and would help to “condition the legal relationship between citizen and state in a general, overarching manner.”Footnote 42 As such, they provide a standard against which legislators delegating powers-with-insulation could be assessed and held accountable.

This does not mean that, to gain traction, the Principles must always and everywhere be incorporated into a legal constitution, whether codified or not, so that they are justiciable. They might amount to a convention, living in the space between law and quotidian politics, at first underpinned by political and social sanctions rather than the courts—but possibly later partly respected by legal doctrine.Footnote 43 In other words, to make a difference they would at least need to amount to a “political norm,” accepted by and, hence, commanding allegiance amongst the core officers of the main branches of the state, and supported and informally enforced by a critical mass of outside commentators.Footnote 44

Where a polity’s constitutional provisions are codified, it also has the option of specifying that some specific public-policy commitment devices may or must exist, and of entrenching some of the constraints on them, such as their purposes, powers, limits, and the like. Here we have another way in which constitutionalism could embrace different degrees of entrenchment for institutionalized commitment technology. In terms of our democratic values, however, the more that is formally entrenched, the more important it is that there exist workable processes for the constitution to be formally amended rather than reconfiguration relying, in practice, upon shifting judicial interpretations.

That leads to an important conclusion on the legitimate mandate of independent agencies. Namely, the mandate of an independent agency should be narrower, the more deeply the institution is entrenched and the harder it is to amend the constitution.Footnote 45 This will prove significant, in Section G, for how we should think about the ECB given Section F’s discussion of central banks in general.

F. Independent Central Banks are a Special Case

Equipped with that general framework for independent agencies, we can return to central banking. On the one hand, everything said so far applies to them. Analytically, the missing ingredient in monetary economists’ time-inconsistency theories was the necessity of institutional mechanisms that generate audience costs for legislators who reverse their delegations and that harness the self-regard of central bank policy makers.Footnote 46 Normatively, in constitutional democracies, the Principles for Delegation should govern such regimes, meaning all of the functions of independent central banks.

On the other hand, however, it turns out that, given our constitutionalist values, monetary authorities are also somewhat special, setting them slightly apart from most other independent agencies.

I. Monetary Independence as a Corollary of the High-Level Separation of Powers

One of the decisive steps towards our modern system of democratic governance was insistence that representative assemblies formally approve a prince’s desire to levy extra taxes. Today’s separation of powers would be undermined if the executive government could use a power to print money as a substitute for legalized taxation. If the executive branch controlled the money-creation power, it would at very least be able to defer its need to go to the legislature for extra “supply,” and at worst could inflate away the real burden of its debts to reduce the amount of taxation requiring Parliamentary or Congressional sanction. In other words, it could usurp the legislature’s prerogatives.

If, as we argued earlier, something like the old gold standard is not viable under full-franchise democracy, the solution is to delegate the management of the currency’s value to an agency designed to be immune from the exigencies and temptations of short-term popularity.

Seen thus, an independent monetary authority is a means to underpinning the separation of powers once the step to adopt fiat money has been taken. The regime’s insulation is derivative of the higher-level constitutional structure and the values behind it.

II. The Fiscal Shield: Barring Monetary Financing of Government

This view provides a double-headed constitutional basis for a rule that the central bank should not provide “monetary financing” to government. On the one hand, if the executive government could demand central bank financing, it would have access to the inflation tax by the back door, and the commitment to price stability would lack credibility. A bar on such demands can be thought of as a central bank’s Fiscal Shield. On the other hand, if the central bank could lend directly to government on its own discretion, unconstrained by its stability objective, it would be able to choose whether a financially stretched government survived, making it a master rather than a trustee. Both elements of a “no monetary financing” constraint draw on the republican value of non-domination.

III. The Fiscal Carve Out

Because central banks take risk and their actions can have distributive and allocative effects, the Shield needs to be combined with a Fiscal Carve-Out that constrains their discretion in managing their balance sheets.Footnote 47 The details might differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but each would need to cover: The kind of assets the central bank can lend against; the kind of assets it can buy, in what circumstances, for which of its purposes, and whether those operations are ever subject to consultation with the executive government or legislature; the need for clarity on which legislated purpose is served by particular operations; how losses will be covered by the fiscal authority, and how they will be communicated to government and legislature.Footnote 48

As a general matter, this does not mean that either the legislature or executive government must list or approve every security that the central bank may lend against or buy outright. A Fiscal Carve-Out might reasonably be cast in terms of general criteria (or standards), leaving the detailed fleshing-out of the regime to the technical expertise of the central bank.

But a polity’s Carve-Out would lay down detailed terms, proscriptive and prescriptive, governing the use of its central bank’s balance sheet to tackle, say, climate change or inequality (in its manifest varieties) because otherwise unelected technocrats would be making big value judgments about who and what needed how much help or hindrance from the state.

IV. Monetary Authorities in the Regulatory State

The constitutional argument for central bank independence applies only to monetary policy, with its latent power of taxation. It does not apply to the other responsibilities a central bank may have, notably regulatory policy and prudential supervision.

What’s more, a central bank with both monetary powers and regulatory powers risks being an over-mighty citizen. And, yet, as Paul Volcker so rightly said, with tragic foresight:Footnote 49

“I insist that neither monetary policy nor the financial system will be well served if a central bank loses interest in, or influence over, the financial system.”

Since, in the years running up to the GFC, the Greenspan Fed lost interest in finance and the Bank of England lost formal levers over it, this plainly matters. Why should that be so? The reason is elemental. The central bank must accommodate sudden jumps in demand for its money—the economy’s ultimate liquid, safe asset—if it is to avoid inadvertent deflationary restraint on economic activity. The most dramatic jumps in demand come in the form of runs on banks. When the central bank acts as the lender of last resort (LOLR), it is therefore both stabilizing the private part of the monetary system—banking—and ensuring that the liquidity crunch does not interfere with the course of monetary policy. It should not be surprising that these two ends are conterminous: Our societies have accepted monetary arrangements that truly comprise a system. One in which most of the money used in the economy is privately issued but accepted as such only because it can be exchanged for central bank money.

This is the significance of the “pivot” metaphor used by Francis Baring over two centuries ago, quoted at the Article’s head. Being a monetary-economy’s liquidity reinsurer has dramatic effects on where and when the central bank crops up in a country’s economic life. As LOLR, it is pretty well certain to find itself at the scene of a financial disaster. That being so, central banks have an interest in being able to influence the system’s regulation and supervision. At the most basic level, when they lend, they want to get their money back! They need to be able to judge which banks—and, possibly, near-banks whose liabilities are treated as safe—should get access to liquidity, and on what terms.

Even opponents of ‘broad central banking’ generally accept that, as the lender of last resort, the central bank cannot avoid inspecting banks which want to borrow. Events in the UK in 2007 demonstrated that doing so from a standing-start is hazardous for society.Footnote 50 A central bank must be able to track the health of individual banks during peacetime if it is to be equipped to act as the liquidity cavalry; and if it is to be able to judge how its monetary decisions will be transmitted, via the financial system, into the economy.

In some jurisdictions, for example Germany and Japan, this is reflected in a set-up where the central bank conducts inspections of banks but does not take formal regulatory decisions. There might be cultural specificities here. Sitting next to former Bundesbank President Helmut Schlesinger at dinner, I once asked why he publicly maintained that central banks should not be the bank supervisor when, as a matter of fact, many—perhaps most—of the German central bank’s staff were engaged on bank supervision. The response was that the central bank was not formally responsible or accountable, so banking problems would not infect the Bundesbank’s reputation and standing as a monetary authority. This is problematic held against the light of modern democratic constitutionalism. We should not try to hide the reality of power’s residence.Footnote 51

In summary, then, we should think of monetary system stability as having two components:

-

stability in the value of central bank money in terms of goods and services; and

-

stability of private-banking system deposit money in terms of central bank money.Footnote 52

For the reasons rehearsed, central banks cannot sensibly be excluded—or exclude themselves—from the second leg. But if they are involved materially in supervision and regulation, whether alongside other agencies or alone, our political values demand that their role should be formalized, through a legislated mandate, objective, and powers.

In line with the Principles for Delegation, their remit should be to deliver a monitorable objective, which elsewhere I have argued should be framed as a “standard for resilience.”Footnote 53 As with the deployment of balance-sheet powers, any use of regulatory powers for purposes other than system resilience would need to be scripted, in law, by elected policymakers.

V. A Modern Money-Credit Constitution

Back in Section B, we summarized the 19th century’s gold-standard-based Money-Credit Constitution. That package was deficient in so far as it did not cater explicitly for solvency-crises as opposed to liquidity-crises. Worse, as our economies moved to embrace fiat money during the 20th century, policymakers relaxed the connection between the nominal anchor and the binding constraint on bank balance sheets so comprehensively that it became non-existent.

At a schematic level, a Money-Credit Constitution for today would have five components:

-

a target for inflation (or some other nominal magnitude);

-

a requirement to hold reserves—or assets readily exchanged for reserves—that increases with a bank’s leverage/riskiness and with the social costs of their failure;Footnote 54

-

a liquidity-reinsurance regime for banks; and, under specified conditions, for shadow banks;

-

a resolution regime for bankrupt banks (and any other issuers of “safe assets”) in order to maintain order without taxpayer bailouts; and

-

constraints on how far the central bank is free to pursue its mandate and structure its balance sheet.

Those constraints are absolutely vital to locating a constitutionally safe place for independent central banks. Most important, they would include the already discussed bar on monetary financing of central government made famous by Europe’s Maastricht Treaty, part of the Fiscal Shield; and a parallel bar on lending to firms that they know, or reasonably should know, to be fundamentally broken, on the grounds that doing so effects a fiscal redistribution from longer-term to short-term creditors.Footnote 55 Beyond the elemental, there would also be constraints on how far the central bankers could use their balance-sheet and regulatory powers to pursue other social goals. For example, if society wishes to tax climate polluters, the elected government/legislature should either do so itself, or set detailed proscriptions and prescriptions on how the central bank must do so. Otherwise, the central bank would slip towards substituting for government as we know it.

VI. A Fourth Branch?

A Money-Credit Constitution bears a family resemblance to economic constitutionalism advocated by James Buchanan and the German ordo-liberal tradition.Footnote 56 But does that mean that an independent central bank must be entrenched at the highest constitutional level? No.

Indeed, my discussion of independent agencies in general and central banks in particular should bring some reassurance on the biggest complaint lodged by the opponents of monetary independence. Provided that central banks are established by and operate under legislated regimes that comply with the Principles for Delegation—or something like them— they are not, inherently or formally or in practice, a new fourth branch of government that ranks alongside the canonical three branches. That is because Principles-compliant central banks are subordinate, in different ways, to each of the higher-level branches of the state: Delegation of statutory powers (legislature); nomination or appointment of agency leadership (executive); adjudication of disputes about vires or due process under the law (courts).

In fact, the greater issue is whether there should be a formal constitutional bar on the legislature turning on the inflation tax by permanently monetizing the debt. Such a capability can live alongside an independent central bank provided people think it is very unlikely to be switched on—and so monetary independence switched off. Whether to leave it open, with its own hurdles and accountabilities, is properly a democratic constitutional choice.

Returning, then, to Milton Friedman’s complaint to the US Congress on the 50th anniversary of the Federal Reserve, quoted above. I want to underline the significance of one of the central tenets of Section D of this Article: namely, that when thinking about the parts of government insulated from day-to-day politics, we should not lump them all together. Instead, we should distinguish trustee-type agencies, even those demanded by the separation of powers, from those arms of the state whose purpose is to guard the rule of law and the democratic process. The high judiciary and, perhaps, some independent electoral commissions meet that description. But central banks are not Guardians of the high values, integrity, or existence of the democratic rule-of-law state.

VII. The Grand Dilemma of Central Banking: The Only Game in Town?!

That conclusion might well seem to sit uneasily with Section B’s lament that, since the 2008/09 crisis, central banks have been the only game in town. In ways and to a degree never expected, the world has bumped into a costly strategic tension between central banks and elected policymakers. The former have legal mandates that impose constraints and obligations, whereas the latter are subject to a few constraints but carry very few, if any, legal obligations to act. In consequence, when short-term politics raises problems—what political scientists call “political transaction costs”—for elected governments and legislators acting to contain a crisis or bring about economic recovery, they can sit on their hands safe in the knowledge that their central bank will be obliged by its mandate to try to do more, within the legal limits of its powers. The upshot can be a flawed mix of monetary, fiscal, and structural policies, creating avoidable risks in the world economy and international financial system.

This is the grand dilemma of central banking: imposing clear duties on the unelected central bankers, as legitimacy requires, leaves us overly dependent on them so long as the elected fiscal authorities are not subject to their own set of duties. We need to wake up to the fact that a cost of central bank independence has been under-investment in fiscal institutions.

In other words, a money-credit constitution is not enough: Advanced-economy democracies need a fiscal constitution that says more than merely that elected representatives decide fiscal policy. It needs, amongst other things, to cover the role of the fiscal authority in stabilizing an economy facing deep recession when monetary policy rates of interest are close to their effective lower bound; how government will track and address the distributional effects of central banks’ actions; the responsibility of elected officers for determining redistributive or reallocative taxes and subsidies; and, in the financial services sphere, whether a government has a capital-of-last resort policy for when all else has failed, together with how to make “no taxpayer bailouts” a credible policy.Footnote 57

These questions are not small. For example, at the macro level, if the automatic stabilizers of the tax and welfare system were to be reset in order to kick in more strongly in really bad economic circumstances, it might be necessary for governments to operate with lower stocks of outstanding debt during normal times. Issues of this kind have tended to get much less attention than debates about optimal monetary policy. And at the micro level, the distinction between taxes as a mechanism for funding spending and as means to adjust relative prices would need to loom larger in public debate.

What those examples have in common is the need for society to reject the notion that central banks are the Only Game in Town, whether to revive economic activity or cure social ills. This is not because they failed, but because it is not sustainable and violates our values. Even where central bankers themselves see this, as some surely do, they cannot do more than talk about it. As a matter of constitutional decency, they cannot play at being Plato’s Guardians.

But there is no reason on earth why central bankers should not speak about the downsides to their policies and about their limited role in healing the economy, or society’s faultlines. They badly need to get back to a previous generation’s mantra, repeated over and over again: Central banks can buy time for economic adjustment but cannot generate prosperity. They can help the economy to recover from disastrous recessions, but cannot improve underlying growth dynamics. They can help to bring spending forward, but cannot create more long-term wealth. To channel a former Bank of England Governor, the late Eddie George, stability is what central bankers exist to deliver, and stability is a necessary condition for the good things in life, but it is not remotely sufficient.

This requires central bankers to pull off a tough act of communication, explaining what they cannot deliver rather than what others should do. And it means admitting ignorance of the deep forces that might be reshaping real-economy prospects, while getting across that those transformations do not jeopardize their ability to deliver their core mission of monetary system stability.

G. The ECB’s Precarious Position in an Incomplete Constitutional Order

So, finally, we arrive at the ECB. Here, my general conceptualization and justification of the legitimacy of central banking stumbles. This is serious and needs some unpacking. I will only scratch the surface.

I. Not a Regular Central Bank

The most obvious difference between the ECB and its notional peers is that it is not established by ordinary legislation passed by Council and Parliament but, instead, through a treaty among the EU’s many member states, each with their own ratification process, some involving referenda. In practice, the ECB’s independence is a deeply entrenched as it possible to get. Following the arguments of Section E, this implies that its functions ought to be narrowly constrained—more so than for central banks granted independence by ordinary (and therefore amendable) legislation.

II. Deep Entrenchment Versus an Incomplete Economic Government

But the differences between the ECB and its peers—the Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, Bank of England, Swiss National Bank—are deeper than that, with profound implications. Unlike the central banks serving national or federal democracies, the Euro area’s central bank does not work alongside a counterpart fiscal authority elected by the people. Because, as described in Section B, a bank of issue has latent fiscal capabilities, establishing a common money in Europe entailed creating fiscal instrumentality in a confederal polity without the familiar—albeit substantively thin—fiscal constitution of nation states.