In a previous article, I argued for the authenticity of the *Cang Jie pian 蒼頡篇 bamboo-strip manuscript held by Peking University.Footnote 1 This assessment was based on the identification of irregular features in the manuscript unattested previously and unanticipated by the state of the field at the time, but then confirmed by archaeologically excavated data first available or fully appreciated only after the Peking University Cang Jie pian was secured. Two such novel features were raised in defense of the Peking University Cang Jie pian: (1) the presence of lines applied extensively across the verso of the manuscript, and (2) textual parallels with content found primarily on the Shuiquanzi 水泉子 *Cang Jie pian manuscript. An analysis of these phenomena indicated with a high degree of confidence that the Peking University Cang Jie pian is indeed a genuine artifact.

Over the past few years, study of the Cang Jie pian has benefited from new discoveries and the release of more data. Additional information is now available that supplements my prior authentication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian. In the following, I survey fresh evidence that bolsters this authentication. The evidence includes confirmation of spiraling lines and other unusual features of the verso marks, which were known only from unprovenanced manuscripts before, but are now seen among the archaeologically excavated Shuihudi 睡虎地 Han bamboo strips. Further cases of textual parallels between the Peking University Cang Jie pian and previously unknown Cang Jie pian content are also raised. Examples are drawn from a strip collected at Niya 尼雅 during Aurel Stein's fourth expedition, and from the full publication of the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian manuscript.

In light of recent developments, we are also afforded an opportunity to examine in greater detail the methodological assumptions underpinning this assessment. When is a feature both unattested and unanticipated by the state of the field? How do we determine when archaeological data that confirms said features are first known or fully appreciated? What happens if novel features on a unprovenanced manuscript are instead later found to be in conflict with archaeologically excavated artifacts? In order to explicate these points, I examine a conflict between the Peking University Cang Jie pian and recently released content from the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian, discussing various possible explanations for the discrepancy. Even more significant, however, has been the announcement that there exists yet another unprovenanced *Cang Jie pian manuscript, held in a private collection and previously unknown to the public. I briefly describe this so-called “Han board” witness and offer initial thoughts on how the existence of this manuscript impacts authentication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian.

Spiraling Lines and Other Verso Features on the Shuihudi Han Strips

The existence of verso lines in and of themselves helps to prove the authenticity not only of the Peking University Han manuscripts, with the Cang Jie pian among them, but also that of other collections of unprovenanced manuscripts, including those held by the Shanghai Museum, Tsinghua University, and Yuelu Academy.Footnote 2 Before elaborating, however, please note that I am no longer referring to these collections as “purchased manuscripts.” The reason for calling them such in my prior article was to avoid assumptions about the manuscripts’ origins and authenticity, as is the case when using the term “looted manuscripts.”Footnote 3 I am grateful for the critique of this practice by one of the anonymous reviewers, who rightfully points out that using “purchased manuscripts” risks treating these objects foremost as economic commodities and thereby unduly emphasizes their financial value. This in turn may appear to legitimate trade in illicit antiquities, while also downplaying the manuscripts’ complex histories and ethical entanglements. This is not my intent, and to avoid this I now adopt the term “unprovenanced manuscripts,” following other recent articles that discuss artifacts of this nature.Footnote 4

To summarize the prior discussion of the verso lines: Explicit mention is made of verso lines in the 1991 report on the Baoshan 包山 Chu strips, and photographs of various strips’ versos with these marks were published infrequently before Peking University's acquisition of the Han strips in January 2009.Footnote 5 Yet the extensive presence of verso lines was only fully appreciated late in 2010, following the publication of complete verso photographs for a number of Tsinghua University and Yuelu Academy manuscripts, and the research conducted by Sun Peiyang 孫沛陽 and others on both unprovenanced and archaeologically excavated manuscripts alike.Footnote 6 The verso lines therefore may be taken as a novel feature for the Peking University Han strips and for collections acquired before 2010.Footnote 7 That verso lines now are widely documented on archaeologically excavated manuscripts, whether newly identified on old caches or newly unveiled on the latest finds, likewise supports the authenticity of the Peking University Han strips and these other unprovenanced collections.Footnote 8

This argument hinges in large part on the claim that verso lines were only “fully appreciated” late in 2010. It is an assertion that speaks to both the novelty of the feature for the Peking University Han strips, and also to the viability of raising older caches of archaeologically excavated manuscripts as evidence for authentication. The question ultimately becomes, “who knew what, when?” And the answer to this question must take into account both the accessibility of information and its understanding. While a threshold of 2010 is, in my opinion, uncontroversial—and indeed substantiated once again by the editing of the Shuihudi Han strips, as will be shown below—the fact that limited mention of the phenomenon and partial data had been published earlier may invite skepticism. The verso marks are a challenging case, in that the raw data under discussion has been present on manuscripts unearthed long before the Peking University acquisition (a matter of accessibility to information), but largely neglected until only recently (a matter of its understanding).

It was noted before that the Peking University Han strips and other unprovenanced manuscripts, primarily those among the Tsinghua University and Yuelu Academy collections, bear unusual characteristics to their verso marks.Footnote 9 One such characteristic is that verso marks can form “sets,” likely fashioned from the same bamboo culm, where the carved line spirals, connecting from the last strips of the set back to the initial strips in the same set.Footnote 10 Another characteristic is the occasional rearrangement of strip order between when the verso marks were produced and the manuscript was finalized for writing. This results in abnormalities to otherwise continuous verso lines, including gaps, buffer strips, the displacement of line sections, or the “reversed-angled steps” phenomenon.Footnote 11 Similarly, reorientation of bamboo strips after production of verso marks appears to have occurred as well, for example with strips rotated 180° before writing, vertically “flipping” the presentation of verso marks.Footnote 12

None of these phenomena—like the verso lines themselves—were fully appreciated when Peking University first acquired their Han strips. Yet, unlike the mere existence of verso marks, most of these additional characteristics could only be distinguished upon examination of the complete versos of bamboo-strip manuscripts bearing extensive line carvings or drawings. Neither the statement in the Baoshan report, nor prior photographs of strips’ versos, reveal enough information to anticipate the presence of verso mark “sets” with spiraling lines or many of the other anomalies listed above.Footnote 13 It is possible that the rotation of strips (whether vertically or horizontally) during some stage of a manuscript's chaîne opératoire may be inferred from archaeological specimens, where notches for securing the binding cord were duplicated on both sides of a strip, or carved into otherwise incongruous locations, suggesting differing orientations for the strip in the course of the manuscript's production.Footnote 14 Even this, however, is a very tenuous inference, and must further relate the carving of notches relative to that of the verso lines in the manuscript's chaîne opératoire.

The requisite data for appreciating these features was not publicly disseminated before the Peking University acquisition, limiting the accessibility of this information. Here a distinction needs to be drawn between public and potential private dissemination. We cannot rule out that caretakers of excavated manuscripts accessed this sort of data, or privately shared it with other individuals. There is, however, indirect evidence that even the editors of many of these manuscript caches remained unaware of the verso marks and their importance until the 2010 threshold. This is demonstrated clearly in the editing of the Shuihudi Han strips, presented below. Consider, as well, the statement by Chen Songchang 陳松長 that

when we were first editing the [Yuelu Academy] Wei li [zhi guan ji qianshou 為吏治官及黔首 manuscript], we had only a rudimentary understanding of the features present on the strips’ versos. Although we later took photographs of the strips’ versos with an infrared scanner … at that time we still had a limited appreciation of the verso lines and similar data, with our attention falling solely on any writing present on the back of the strips.Footnote 15

Owing to the general inaccessibility of data, and the lack of its appreciation by the limited number of caretakers who might have had access, confirming characteristics like the verso sets with spiraling lines on archaeologically excavated artifacts provides even greater confidence in the authenticity of the Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Yuelu Academy manuscripts.Footnote 16

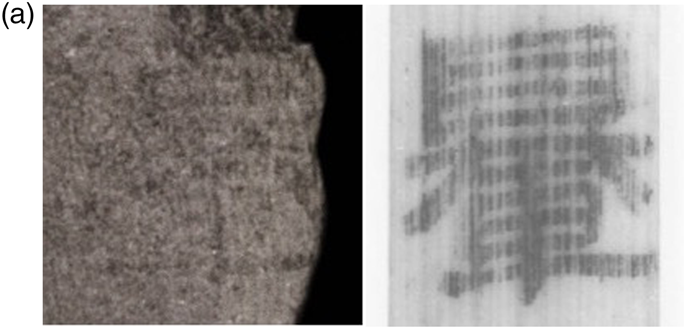

The Liu nian zhiri 六年質日 manuscript unearthed from Shuihudi Han tomb M77 offers the first published photographs of an archaeologically excavated artifact exhibiting a variety of the above verso mark characteristics. In November of 2006, during construction work on the Han–Dan railway line, a hole was accidently drilled into a grave, now labelled M77, within the Shuihudi cemetery, in Yunmeng 雲夢 County, Hubei.Footnote 17 Inside this grave was a bamboo basket containing at least 2,137 bamboo strips and tablets.Footnote 18 Remarkably, the majority of these strips were not significantly displaced from the positions in which they were deposited originally, when bound as scrolls and stacked together. This has aided immensely reconstruction of individual manuscripts.Footnote 19 Only those on the east side of the basket suffered damage from the drilling, breaking a small number of strips and dispersing the pieces. Contents of the cache include event calendars, legal statutes, daybook materials, a mathematical treatise, anecdotal narratives featuring various famous historical figures, and accounting records.Footnote 20 A comparison of the tomb structure and its contents to other previously excavated graves suggests that the burial is from the early Western Han period, which is confirmed by the dates on the event calendars and accounting records. The burial must have taken place shortly after the tomb occupant, Yue Ren 越人, passed away in 157 b.c.e.Footnote 21

The brief report for Shuihudi M77 does not mention verso marks appearing on any of the strips.Footnote 22 In 2010, Xiong Beisheng 熊北生 published an article on the methodology employed by the editors to arrange the manuscripts in this cache.Footnote 23 Xiong emphasizes how they relied heavily on the strips’ in situ placement, checked against the content of the texts. Once again, no mention is made of the verso marks, or of how they could be used to establish strip order. This, in particular, suggests to me that the editors of the Shuihudi Han strips still were not aware of the verso marks when preparing the article. The timeframe is consistent with a late 2010 threshold for the full appreciation of this feature by the field, on unprovenanced and archaeologically excavated bamboo-strip manuscripts alike.Footnote 24 In 2018, Cai Dan 蔡丹 published an article examining the verso lines present on Liu nian zhiri 六年質日 manuscript, one of the event calendars. It is both the first mention of verso marks on the Shuihudi Han strips, and the first time material features of a complete verso (sans writing) of an archaeologically excavated manuscript, retrieved through controlled conditions, has been subjected to a thorough analysis.Footnote 25

The Liu nian zhiri manuscript is an event calendar for the sixth year following Emperor Wen's 漢文帝 “second inaugural year 後元,” which corresponds to 159–158 b.c.e. It joins a series of other event calendars entombed in M77, the entire series amounting to 719 strips and over a thousand smaller fragmented pieces altogether.Footnote 26 Each calendar lists the months for the given year, separated into those that are even-numbered first, then those that are odd-numbered. Whether a month is da 大 “large” (30-day) or xiao 小 “small” (29-day) is noted. Sexagenary ganzhi 干支 day counts are enumerated for every month. Important events are recorded next to the day on which they occurred, and include seasonal activities (e.g., the La 臘 and Setting-Out-Seeds 出種 festivals), official business (e.g., when Yue Ren “attends to matters” or shishi 視事), and private affairs (e.g., the death of a parent, or travel conducted by a daughter).Footnote 27

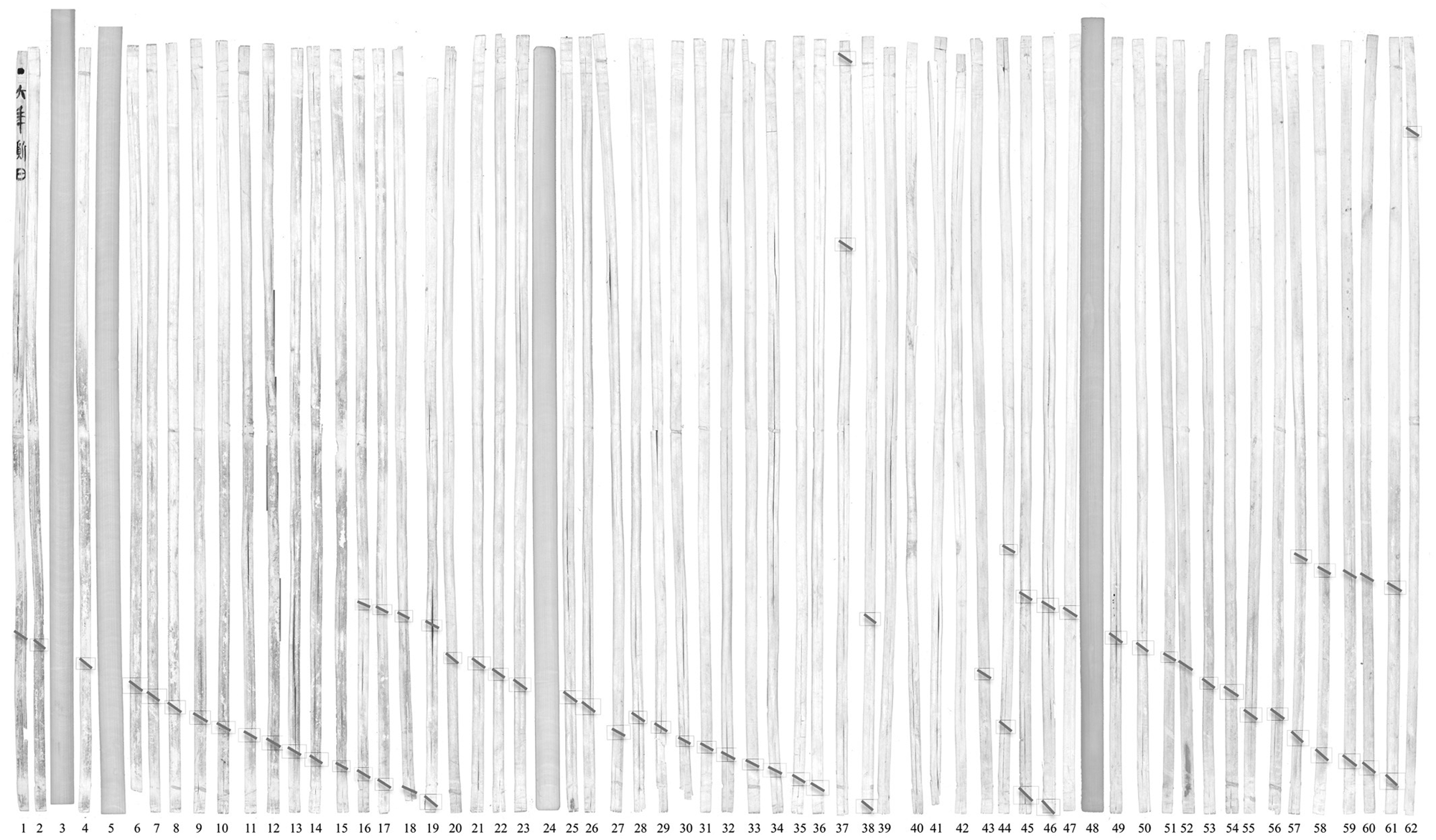

The Liu nian zhiri is written over sixty-two bamboo strips. This strip number is consistent across the Shuihudi Han event calendars. On each calendar, a single strip is used to list the even-numbered months, followed by thirty strips, one for each sexagenary day count, accommodating for “large” months; another single strip is then used to list the odd-numbered months, again followed by thirty more strips for the sexagenary day counts. Should there be a runyue 閏月 “intercalary month,” six more strips are appended (for sixty-eight total), in order to label the month and give its day counts. The Liu nian zhiri strips measure between 26 and 31 cm in length, and were bound by three cords.Footnote 28 Faint horizontal lines are carved across the recto, which together with the binding cords, form six rows, where the scribe isolated day counts to their corresponding months. We may be assured that the strip order presented for the Liu nian zhiri is correct, owing both to the fact that the strips were found relatively undisturbed in situ, and to the formulaic structure of its contents—an event calendar with sequential dates. This is a great boon for the study of the Liu nian zhiri verso lines. With the strip order thus secure, we may now investigate the verso marks for a (relatively) complete manuscript in its final form (see Figure 1).Footnote 29

Figure 1 Liu nian zhiri manuscript verso. Figures 1–3 after Cai, “Shuihudi Han jian zhiri jiance jianbei huaxian chutan,” 126, figure 1; high-resolution image supplied by Cai via personal communication, July 4, 2020.

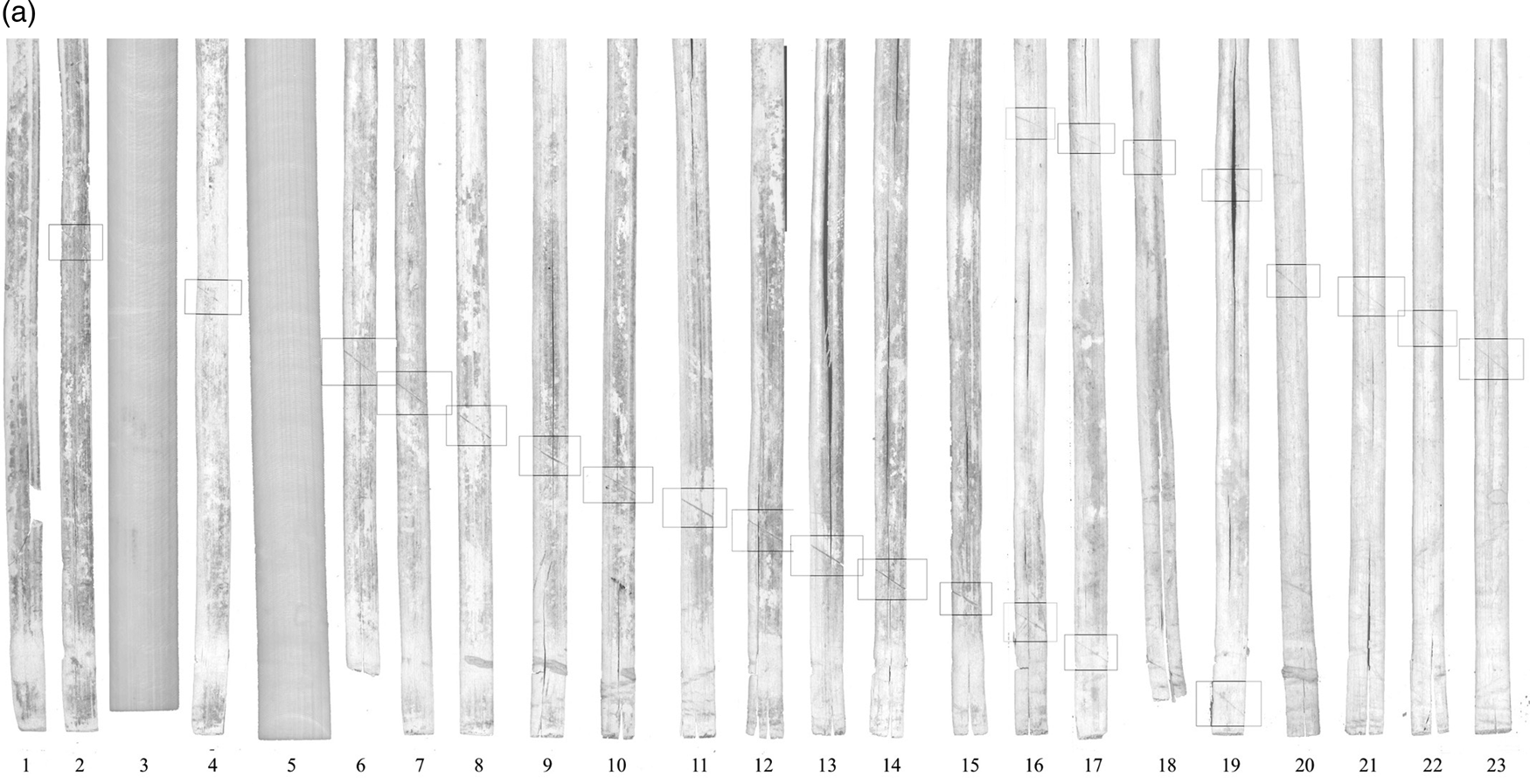

Figure 2a Set 1 and part of set 2, spanning strips 1–23.

Figure 2b Details of verso marks on strips 1–2. Boxes with dotted outline have been added by author to highlight the undocumented marks.

Figure 2c Details of verso marks on strips 17–19. Box with dotted outline has been added by author to highlight the undocumented marks.

Figure 2d Details of the upper row of verso marks on strips 58–61. Boxes with dotted outline have been added by author to highlight the undocumented marks.

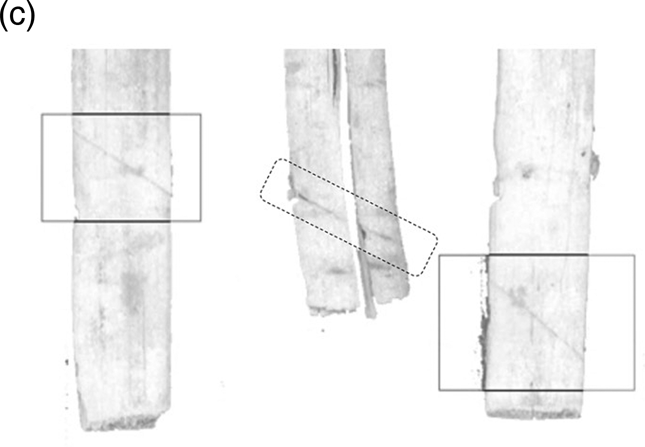

There are obvious discontinuities to the verso lines on the Liu nian zhiri. For example, there is a shift in height and gradient to the verso marks when compared between strips 19 and 20. To explain this shift, Cai argues that this is actually a divide between two separate sets of verso lines, with the line on strip 19 “spiraling back” to connect with the marks at the beginning of the manuscript, instead of continuing onto strip 20 (see Figures 2a and 2b). Indeed, should we place strips 16–19 before strip 1, the verso line is aligned nearly perfectly. I say “nearly” because Cai posits a missing strip before 1, but I do not believe this is necessary. Formal measurements will help clarify this point, though an analysis of the photograph (using pixels to estimate relative distances) suggests that there need not be a missing strip. For the sake of completeness, note also that Cai describes strips 14 and 15 as having two verso marks, upper and lower. These are not boxed in the published image, and their existence is difficult to ascertain with any certainty from the photograph alone.Footnote 30

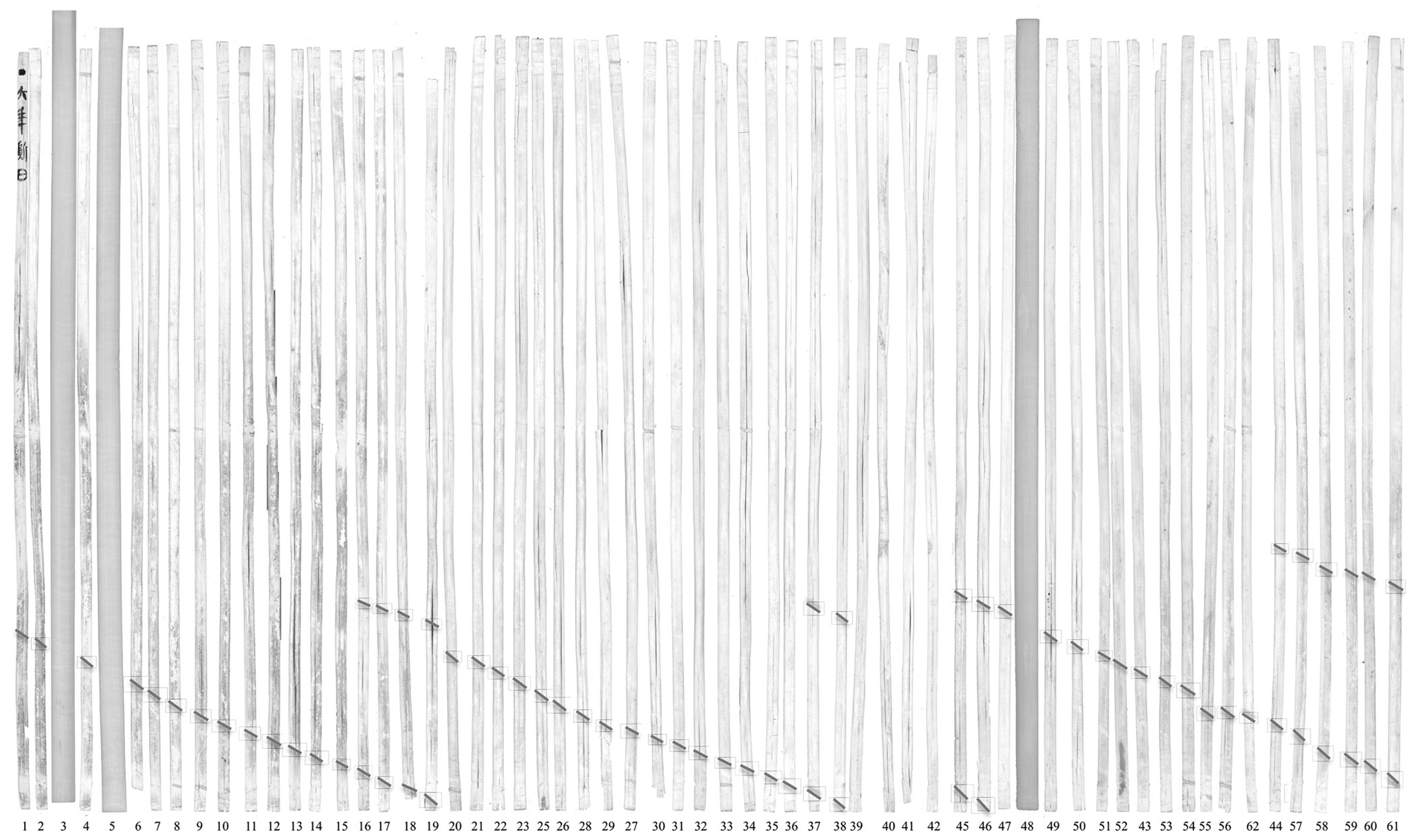

Based on similar observations, Cai divides the manuscript into four sets of strips: set 1 spans strips 1–19; set 2 spans strips 20–38; set 3 spans strips 39–42; and set 4 spans strips 43–62. Of these, set 3 contains four strips without discernable verso marks. The other three sets, Cai believes, originally consisted of around twenty strips, bearing engraved lines that spiraled around the culm tube. Cai offers a reconstruction for the other sets (1, 2, and 4), showing that at certain points after the engraving of the verso line for a given set, but before finalization of the manuscript, strips were either displaced or rotated 180° vertically.Footnote 31 An obvious example of the latter is provided by strip 37, which when rotated back 180° vertically, has verso marks that connect smoothly with both the upper and lower lines in its set. For the manuscript's verso according to Cai's reconstructions, see Figure 3.Footnote 32

Figure 3 Reconstruction of the Liu nian zhiri verso, after Cai, “Shuihudi Han jian zhiri jiance jianbei huaxian chutan.” Speculated missing strips not added.

Caution is merited in treating the Shuihudi Han Liu nian zhiri as archaeologically obtained evidence of verso features only known previously on unprovenanced manuscripts. Take for example the spiraling lines. In set 1, the alignment of the marks on strips 19 and 1 is very close. Though perhaps unnecessary, Cai does suggest that one strip is missing between them. For set 2, however, the connection is much more tenuous, with at least three strips now required to link the upper mark on strip 38 back to that of strip 20. In set 4, we have perfect alignment between the marks on strips 61 and 45, but Cai's reconstruction requires various manipulations to arrive at this point, moving multiple strips around to different positions. If allowed to speculate over missing strips or manipulate known pieces at will, without reasoned justifications, then we risk simply inventing whatever imagined scenario we desire to see in the data.

While acknowledging these issues, I agree with Cai that the Shuihudi Liu nian zhiri manuscript provides the first confirmation of sets of spiraling verso lines and these other features on archaeologically excavated artifacts. Although the Shuihudi Han strips were unearthed just over a year before the acquisition of the Yuelu Academy Qin strips, and around two years before the Tsinghua and Peking University acquisitions, the Shuihudi verso data was not published until quite recently. It is therefore stronger evidence for the authenticity of unprovenanced manuscripts from these caches bearing similar verso features (e.g., the spiraling lines), than the presence of verso marks alone. Unfortunately, while this raises our confidence in the Peking University Han strips as a whole, it is unclear if the Cang Jie pian manuscript in specific bears spiraling verso lines, nor does it bear vertically rotated verso marks.Footnote 33 Other evidence must be raised for the evaluation of this specific manuscript then, primarily newly identified textual parallels, to which we now will turn.

Textual Parallels: A Strip from Niya Collected During Aurel Stein's Fourth Expedition

In January 1931, Sir Aurel Stein visited the site of Niya for a final time, concluding fieldwork for his ill-fated fourth expedition to Central Asia.Footnote 34 Local authorities would not let Stein conduct formal excavations, so he instead surreptitiously dispatched workers during the night, who brought back to him twenty-six wooden strips bearing Chinese text.Footnote 35 One important piece (N.II.2) mentions a “Han Jingjue king” 漢精絕王, helping to confirm the Niya site as the Jingjue Kingdom.Footnote 36 Stein was not permitted to take the artifacts he collected out of China, so he deposited them in the British consulate in Kashgar. The strips he collected were later presented to local authorities, then unfortunately lost. Before leaving, however, Stein took photographs of the strips (with the aid of the British Consul George Sherriff), with the negatives and prints deposited in various institutions; soon these too were forgotten by scholarship. Through the efforts of Wang Jiqing 王冀青, sets of Stein's fourth expedition photographs have been rediscovered in the British Library, and currently stand as our only evidence for an important, if small, collection of Han period manuscripts.

Unable to consult the actual artifacts, we must depend upon the photographs that remain. The clarity of the photographs is remarkable, in light of the circumstances under which they were produced, yet they are far from ideal. Stein himself, in fact, felt dissatisfied with the images, and hired Thomason College of Civil Engineering at Roorkee, India, to make “improved” versions of the glass negatives. As Wang Jiqing has discussed, this improvement entailed someone, likely ignorant of Chinese, mechanically retouching the characters’ strokes, and ultimately such efforts proved to be more of a hindrance than an aid to the strips’ decipherment. The British Library appears to hold not only the “improved” glass negatives, but also a complete duplicate set of negatives (made via exposure on direct duplicating film) and gelatin silver prints that were based on both the nitrate originals and glass negatives. The strip that concerns us here is N.XIV.20, but the precise source of the published photographs of N.XIV.20 awaits confirmation.Footnote 37

It is no surprise, therefore, that scholars have disagreed over the transcriptions of these manuscripts. Furthermore, N.XIV.20 is damaged, with most characters missing portions of their right components, which uniquely frustrates transcription of its text. In his initial study of Stein's fourth expedition Han strips, Wang transcribes strip N.XIV.20 as:  遷難解頓□□頓

遷難解頓□□頓 .Footnote 38 Hu Pingsheng 胡平生 and Wang Tao 王濤 update the transcription to:

.Footnote 38 Hu Pingsheng 胡平生 and Wang Tao 王濤 update the transcription to:  轝

轝

奴(?)婢(?)

奴(?)婢(?) .Footnote 39 I now believe, however, that N.XIV.20 bears content from the Cang Jie pian 蒼頡篇. This identification is made clear upon comparison to the Peking University Cang Jie pian. Zhu Fenghan 朱鳳瀚 transcribes the final seven characters on PKU 40 as: 䡞䡩解姎婞點媿. Figure 4a–f are character-by-character comparisons of N.XIV.20 (with Hu and Wang's transcriptions) and PKU 40 (with Zhu's transcriptions), on the left and right respectively.Footnote 40

.Footnote 39 I now believe, however, that N.XIV.20 bears content from the Cang Jie pian 蒼頡篇. This identification is made clear upon comparison to the Peking University Cang Jie pian. Zhu Fenghan 朱鳳瀚 transcribes the final seven characters on PKU 40 as: 䡞䡩解姎婞點媿. Figure 4a–f are character-by-character comparisons of N.XIV.20 (with Hu and Wang's transcriptions) and PKU 40 (with Zhu's transcriptions), on the left and right respectively.Footnote 40

Figure 4a Character 1: 轝 vs 䡞

Figure 4b Character 2:  vs 䡩

vs 䡩

Figure 4c Character 3: 解 vs 解

Figure 4d Character 4:  vs 姎

vs 姎

Figure 4e Character 5:  vs 婞

vs 婞

Figure 4f Character 6: 奴(?) vs 點

Figure 4g Character 7: 婢(?) vs 媿

Despite the damage to the right side of N.XIV.20, partial strokes often remain, hinting at the orthography of the missing right components. Characters 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 on N.XIV.20 all match up well with the components found on PKU 40 for the corresponding characters. Character 4 on N.XIV.20 may bear an additional horizontal stroke at its top, and the clarity of 5 is less than ideal, but the parallels for both are discernable. In the case of character 1 on N.XIV.20, the upper portion of the character is indistinct, yet the two angled strokes, running in opposite directions, are suggestive of the top component to ju 䡞 on PKU 40. For 6 on N.XIV.20, it is the left side that is blurry, but the right component matches dian 點 on PKU 40. This string of text is non-grammatical, yet it fits the typical format we see for Cang Jie pian text. It is not found in any received or excavated works other than the Peking University Cang Jie pian.Footnote 41 Furthermore, there is precedent for the existence of Cang Jie pian materials at Niya, as one other Cang Jie pian strip was identified at this site previously, during a different survey.Footnote 42 For all these reasons, I find the identification of N.XIV.20 as Cang Jie pian text to be definitive.

This identification further supports the authenticity of the Peking University Cang Jie pian. Although Stein collected this piece close to a century ago, the artifacts have since disappeared, with the photographs likewise long neglected in foreign institutions. Wang Jiqing first published these photographs in 1998, but the initial transcriptions of N.XIV.20 have been misleading; for this reason, no scholar has since raised the possibility that this is Cang Jie pian content.Footnote 43 We may thus treat the text here as an unattested and unanticipated feature of the Peking University Cang Jie pian now confirmed on an archaeological specimen, only fully appreciated after the Peking University cache was secured.Footnote 44 The strength of this evidence is similar to that of the presence of verso marks: we have public dissemination of partial data before acquisition of the Peking University Han strips, yet this information was not yet understood by the specialist discipline.Footnote 45

The discovery that N.XIV.20 belongs to the Cang Jie pian has broader significance beyond just the authentication of the Peking University manuscript as well. Studied together with the one other Cang Jie pian strip previously recovered from Niya, it is now possible not only to confirm details about these strips’ prior deposition on site, but also show that multiple chapters of the Cang Jie pian circulated at Niya. The presence of extensive content from an important scribal primer in the ostensibly foreign kingdom of Jingjue 精絕 bears witness to Han diplomacy and warrants closer investigation.Footnote 46 When studying unprovenanced manuscripts, it is important to acknowledge the destructive impact of looting, and to highlight the consequential loss of archaeological context. N.XIV.20 offers a particularly clear example in this regard: although the strip is interesting enough as Cang Jie pian content in isolation, it becomes vastly more significant when placed within its archaeological context of Han period Niya.

Textual Parallels: Newly Published Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian Content

Although the identification of parallel content between N.XIV.20 and PKU 40 strengthens the authentication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian, it is burdened by the public dissemination of data prior to the Peking University manuscript's acquisition. The Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian, on the other hand, constitutes archaeologically excavated data that was not available to a potential forger before the Peking University acquisition, as it was unearthed just before Peking University secured its Han strips, and was published—still partially—long afterward.Footnote 47 For this reason, the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian remains our strongest body of evidence against which we may compare the content of the Peking University Cang Jie pian, at least until new manuscripts are unearthed.Footnote 48

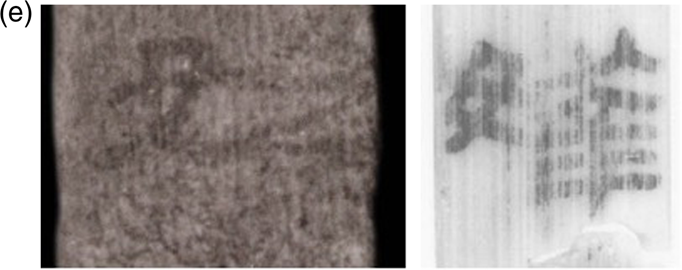

In 2015, Zhang Cunliang 張存良—the editor of the Shuiquanzi cache—completed his dissertation at Lanzhou University, in which he provides transcriptions for the entire Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian and a few new photographs. Unable to consult it for my prior survey, I can now raise additional unique parallels between the Shuiquanzi and Peking University Cang Jie pian witnesses.Footnote 49 For example see Figures 5–6.Footnote 50

Figure 5 PKU 56 vs. SQZ C093 & C062Footnote 51

Figure 6 PKU 59 & 60 vs. SQZ C028, C029, C030, & C031Footnote 52

Other unique parallels may be found between PKU 46 and 47 vs SQZ C024; PKU 52 vs SQZ C066; PKU 63 vs SQZ C082;Footnote 53 and PKU 64 vs SQZ C108.Footnote 54

To reiterate, the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian was recovered during fieldwork that took place from August to October 2008. According to Zhang Cunliang, they completed an initial set of transcriptions for the Shuiquanzi strips on the eve of the National Day 國慶節 holiday that fall.Footnote 55 The Peking University Cang Jie pian arrived on campus on January 11, 2009, but was likely known to representatives from Peking University by the end of 2008. It may have been available for sale on the market even earlier. The Peking University Cang Jie pian's acquisition came prior to any public dissemination of the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian data, as the preliminary report for the Shuiquanzi cache was published at the end of 2009. Private dissemination of this data was possible, but only for a very limited window of time (October 2008 to January 2009), in which representatives of Peking University probably had some knowledge of the Han strips for sale. For these reasons, confirmation that novel content in the Peking University Cang Jie pian is also found on the archaeologically excavated Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian serves as strong proof of the former's authenticity.

Complications to the PKU 65 and SQZ C058 Parallel and their Methodological Significance

In my first survey of the Peking University and Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian witnesses, I raised an overlap between PKU 65 and SQZ C058 as one example of parallel novel content.Footnote 56 There are two complications with this parallel that belatedly have come to my attention. Addressing these issues can help clarify the limitations of my approach, and provides an opportunity to discuss the methodological assumptions underpinning it. The text of PKU 65 and SQZ C058 is compared in Figure 7.

Figure 7 PKU 65 and SQZ C058

Certain conditions must be met in order for this parallel to serve as evidence for the authenticity of the Peking University Cang Jie pian. To raise the Shuiquanzi manuscript as archaeological confirmation of the content, a timeline must be established showing that this data was accessible only after the Peking University acquisition, as outlined above. For the Peking University data, it is necessary to show that the content is unattested previously and unanticipated by the state of the field before the manuscript was secured. In this instance, that novel feature is the content found on PKU 65, and the final characters in particular: 堯舜禹湯顡卬[趮][蟨] ![]() (which reads “Yao, Shun, Yu, Tang, resolute, look towards, [restless], [hurried]”).Footnote 58 The first complication concerns the novelty of this content.

(which reads “Yao, Shun, Yu, Tang, resolute, look towards, [restless], [hurried]”).Footnote 58 The first complication concerns the novelty of this content.

How can we demonstrate that this feature is both unattested and unanticipated? Demonstrating novelty (in both regards) demands, in a certain sense, the notoriously problematic task of proving an absence.Footnote 59 For the present case study, my approach was (1) to survey all published wood and bamboo-strip manuscripts unearthed prior to the Peking University acquisition for potential parallel content; (2) to check my findings against other scholarly compilations of Cang Jie pian manuscripts; and finally (3) to review scholarship in the field more broadly for discussions that may be relevant to the parallel in question.Footnote 60 The massive quantity of materials to survey, both among primary sources and secondary scholarship, together with the possibility of unpublished data or data otherwise difficult to access, raises the probability of overlooking evidence.

Such was the case in my evaluation of the PKU 65 and SQZ C058 parallel. Among the richest caches of manuscripts with Cang Jie pian content are the hundreds of shavings collected by Aurel Stein during his second expedition to China, now held in the British Library (strip labels: YT).Footnote 61 As noted before, when Édouard Chavannes first organized the Han strips collected by Stein, he prioritized publishing only the most legible specimens in his Les Documents Chinois, leaving out these shavings. This omission was rectified by the Yingguo guojia tushuguan cang Sitanyin suohuo weikan Han wen jiandu 英國國家圖書館藏斯坦因所獲未刊漢文簡牘 (aka Yingtu) volume published in 2007, but only in part.Footnote 62

It turns out that, once again, over a hundred shavings inadvertently were left out of the Yingtu volume as well. The International Dunhuang Project website included photographs for the missing shavings in its database, but more formal dissemination of the data only occurred with articles released during the summer of 2016.Footnote 63 Among them is an important piece, YT 1852, with parallel content related to PKU 65 and SQZ C058, not mentioned in my prior discussion:  禹湯㥟卬廣厥賓分笵□

禹湯㥟卬廣厥賓分笵□ .Footnote 64 My previous neglect of this strip highlights a limitation in my approach: since demonstrating novelty demands proving an absence, all data must be accounted for and ruled out, which is unrealistic or often impossible. As a result, our evaluations must be constantly revisited and refined.Footnote 65

.Footnote 64 My previous neglect of this strip highlights a limitation in my approach: since demonstrating novelty demands proving an absence, all data must be accounted for and ruled out, which is unrealistic or often impossible. As a result, our evaluations must be constantly revisited and refined.Footnote 65

Before elaborating upon the significance of YT 1852, let me note that this limitation to demonstrating novelty applies to both the attestation and anticipation of the feature in question, though in slightly different ways. While the example above pertains mostly to prior documentation of the actual feature (i.e., finding the same content written on other Cang Jie pian manuscripts already unearthed), it is also important to ensure that a forger could not have reasonably anticipated the feature's existence (on genuine artifacts, perhaps yet to be found) based on the state of knowledge in the field at that time. For example, imagine that the line on PKU 65 instead read: 堯舜禹湯文武成康 (listing out the proper names “Yao, Shun, Yu, Tang, Wen, Wu, Cheng and Kang”). Even if archaeologists discovered Cang Jie pian manuscripts with this same content in the future, it offers only weak evidence for the authenticity of our re-imagined Peking University manuscript. This is because a forger may anticipate pairing the sages Yao, Shun, Yu and Tang, with the names of the first Zhou kings, Wen, Wu, Cheng and Kang. Indeed, other early received texts such as the Mozi 墨子, often list Wen and Wu after Yao, Shun, Yu and Tang; similarly, other works, like the Shang shu 尚書 and Zuo zhuan 左傳, discuss Wen, Wu, Cheng and Kang together as a unit.Footnote 66

The reason that YT 1852 is noteworthy for the PKU 65 and SQZ C058 overlap, however, is not because it greatly impacts our evaluation of the content's novelty. While the SQZ corpus is the best archaeological check for authenticating the Peking University Cang Jie pian to date, certain content among the British Library corpus was not fully appreciated before Peking University acquired their Han strips. This was my argument for the YT 3559 and PKU 3 overlap in the prior article, echoing my analysis of the Niya strip above, and it equally applies to YT 1852 here.Footnote 67 Rather, YT 1852 is noteworthy because it highlights a second complication: that the Peking University Cang Jie pian conflicts in various ways with newly excavated or appreciated archaeological data for these lines.

Our three witnesses read as shown in Figure 8 (removing the [] from the PKU 65 transcription for 趮蟨).

Figure 8 Comparison of PKU 65 and SQZ C058 with YT 1852.

There are certain character variants present on YT 1852. Most significantly, on PKU 65 the final two characters, while fragmentary, clearly have 目 as a left component. But on YT 1852, the characters in the parallel positions instead read bin fen 賓分, neither of which being written from 目 or a graphically similar left component. There are, moreover, other pieces among the British Library cache that write out bin fen fan 賓分笵, such as the gu prism YT 1791, suggesting that this is not simply an isolated occurrence on YT 1852.Footnote 68

A less obvious but perhaps more troublesome conflict involves the structure of the Cang Jie pian text and, specifically, where the Peking University and SQZ manuscripts suggest line divisions. Although PKU 65 is fragmentary, ample blank space remains on the strip below ⿰目□⿰目□, while the bottom end of the piece is also level. A notch is also recorded at the top of the fragment, with partial writing remaining just above it as well, which means it is most likely the middle notch.Footnote 69 This indicates that the fragment was once the bottom of a strip, with ⿰目□⿰目□ concluding the text on this specific writing support. The Peking University Cang Jie pian is strictly formatted: every strip bears twenty characters of base text, amounting to five complete lines from the Cang Jie pian. In other words, the structural logic of the manuscript necessitates that the final characters on every strip must also conclude a line of Cang Jie pian base text.Footnote 70 Following this logic, PKU 65 should read: … 堯舜,禹湯顡卬,[趮][蟨] [趮][蟨]⿰目□⿰目□, … (rendered with some poetic license as “… Yao and Shun // And to Yu and Tang, resolutely cast your gaze // [Restless and hurried,] …). It is perhaps for this reason that Zhu Fenghan does not group Yao and Shun together with Yu and Tang as a single line in his annotations, despite the fact we might reasonably suspect this as a coherent unit, being a common list of cultural heroes seen in other works.Footnote 71

On SQZ C058, however, the line division must be different. This again is signaled by the structural logic of the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian, which adds three-character “extensions of meaning” (I will refer to this as commentary for convenience) to the four-character base lines. Through comparison against PKU 65 and YT 1852, the distinction between base text and commentary on the Shuiquanzi witness is clear: … 禹湯 + 稱不絕 // 䫉迎趮厥 + 怒佛甘 (which then translates as “… Yu and Tang; praised eternally // Pulchritudinous, arresting, restless, hurried; enmity is unsavory.”Footnote 72 Because of the commentary's placement, we are assured that the line break for the base text must follow “Yu and Tang” on the Shuiquanzi manuscript.

Note that this appears to be the case for the British Library edition of the Cang Jie pian as well, since bin fen 賓分 begins one side of the YT 1791 gu prism. On other gu prisms with primer content, an individual chapter is written in its entirety on a single piece, with each side of the prism bearing the same number of characters (for the Cang Jie pian, this would be twenty characters per side, for a sixty-character chapter).Footnote 73 Following this formatting, the first characters on the top of the prism begin their own lines. The triangular punctuation mark on YT 1791A secures this fragment as the top of the gu prism, and therefore indirectly establishes that bin fen 賓分 starts a new line.Footnote 74

Novel features on unprovenanced manuscripts offer a unique opportunity to test against newly excavated or appreciated archaeological finds for a positive authentication. But what if the data from new archaeological finds present conflicts instead, as with the PKU 65, SQZ C058, and YT 1852 parallel? Does this then implicate the unprovenanced manuscript, here the Peking University Cang Jie pian, marking it as a forgery? While confirming that even a single novel feature on a unprovenanced manuscript exists among newly excavated archaeological finds would, theoretically, prove the authenticity of the artifact in question, the opposite does not hold true. Later conflicts with the archaeological data might raise suspicions about the unprovenanced manuscript, especially should they consistently appear in an ever more robust corpus of new finds. Yet it remains possible that the unprovenanced manuscript is both authentic and also exceptionally unique. This reveals another limitation to my approach: that it is designed to enable positive authentication, but does not provide similar accommodation for negative appraisals.

The differences between PKU 65 and both SQZ C058 and YT 1852 highlight this point. Previous scholarship has focused on resolving why PKU 65 writes ![]() where YT 1852 has bin fen 賓分. Shortly after publication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian, Zhou Fei 周飛 argued that the two characters with the left component of 目 on PKU 65 should be read lin pan 瞵盼, relying primarily on partial strokes to the right components still remaining on the fragment.Footnote 75 Wang Ning 王寧 explicitly compares PKU 65 to YT 1852, and believes that the former once wrote pin pan 矉盼 instead.Footnote 76 Both of these proposals offer graphically and phonetically close variants to the characters on YT 1852, with the only exception being that 目 is their left component. Variation in which a component is dropped or added, especially the semantic determinative, is common however.Footnote 77 In short, despite the apparent variation between PKU 65 and YT 1852, there is a feasible relationship between their content; and it remains possible that, in the future, other manuscripts will be unearthed which prove this relationship.Footnote 78

where YT 1852 has bin fen 賓分. Shortly after publication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian, Zhou Fei 周飛 argued that the two characters with the left component of 目 on PKU 65 should be read lin pan 瞵盼, relying primarily on partial strokes to the right components still remaining on the fragment.Footnote 75 Wang Ning 王寧 explicitly compares PKU 65 to YT 1852, and believes that the former once wrote pin pan 矉盼 instead.Footnote 76 Both of these proposals offer graphically and phonetically close variants to the characters on YT 1852, with the only exception being that 目 is their left component. Variation in which a component is dropped or added, especially the semantic determinative, is common however.Footnote 77 In short, despite the apparent variation between PKU 65 and YT 1852, there is a feasible relationship between their content; and it remains possible that, in the future, other manuscripts will be unearthed which prove this relationship.Footnote 78

Less attention has been paid to the conflict in line divisions between PKU 65, SQZ C058, and, potentially, YT 1791. Qin Hualin 秦樺林 early on noted that the Shuiquanzi manuscript appends commentary after “Yu and Tang” (禹湯), which necessitates a different line break, and argues that grouping “Yu and Tang” together with “Yao and Shun” (堯舜) makes more sense thematically.Footnote 79 Most scholars now apply this line division to the Peking University manuscript without further comment, with only Hu Pingsheng 胡平生, to my knowledge, acknowledging the materiality of PKU 65 and the problematic placement of the partial characters ![]() .Footnote 80 Yet even Hu disregards the strict formatting of the Peking University manuscript, prioritizing the evidence given in the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian.

.Footnote 80 Yet even Hu disregards the strict formatting of the Peking University manuscript, prioritizing the evidence given in the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian.

In my opinion, there are three potential resolutions to this conflict. The fragmentary nature of PKU 65 invites debate over whether or not it was once the bottom of a strip. Damage might have erased or destroyed ink after ![]() , and the notch above yao 堯 could be an incidental tear. Examination of the physical artifact is necessary to evaluate this appropriately, but this explanation does not seem promising based on the photographs alone. Assuming then that PKU 65 is the bottom of the strip, we may follow Hu Pingsheng and suppose that the Peking University Cang Jie pian forgoes its otherwise strict formatting in this section of text (either purposefully or as a scribal error). There are no other examples elsewhere in the Peking University Cang Jie pian where it diverges from the established format, however, and I find it unlikely that this is a sole exception.Footnote 81 Both of these resolutions posit circumstances unique to the manuscript in question that, while feasible, cannot be tested against new archaeological finds.

, and the notch above yao 堯 could be an incidental tear. Examination of the physical artifact is necessary to evaluate this appropriately, but this explanation does not seem promising based on the photographs alone. Assuming then that PKU 65 is the bottom of the strip, we may follow Hu Pingsheng and suppose that the Peking University Cang Jie pian forgoes its otherwise strict formatting in this section of text (either purposefully or as a scribal error). There are no other examples elsewhere in the Peking University Cang Jie pian where it diverges from the established format, however, and I find it unlikely that this is a sole exception.Footnote 81 Both of these resolutions posit circumstances unique to the manuscript in question that, while feasible, cannot be tested against new archaeological finds.

Alternatively, the conflict could also be due to edition-level variation between the Peking University Cang Jie pian and that of the Shuiquanzi (and possibily British Library) Cang Jie pian, with content added or deleted. The Han shu 漢書 Yiwen zhi 藝文志 gives a detailed textual history for the Cang Jie pian, in which it posits that lüli shushi 閭里書師 or “village teachers” combined three prior texts (the Cang Jie 蒼頡, Yuanli 爰歷, and Boxue 博學) into a single work, with fifty-five chapters, each sixty characters in length. The Peking University Cang Jie pian chapters are all over a hundred characters and must be different from this Village Teachers edition; the Shuiquanzi and British Library Cang Jie pian witnesses, on the other hand, likely derive from the Village Teachers edition, with chapters sixty characters in length. Yet beyond the parsing of chapters, comparison of these manuscripts reveals very little manipulation in the content of their base texts, with most variants at the level of individual characters or words, making the edition-level variation intimated by PKU 65 vs SQZ C058 (and perhaps YT 1791) rather surprising.Footnote 82 Regardless, edition-level variation is both feasible and liable to archaeological confirmation.

To summarize the discussion above, there are limitations to my methodology for authenticating the Peking University Cang Jie pian, which are amply demonstrated by the PKU 65 and SQZ C058 parallel. On the one hand, ensuring novelty demands an analysis of all previous data. Because of the sheer amount of data to survey, and the possibility of unpublished or otherwise inaccessible data, claims for novelty must be constantly revisited and updated. In this case, YT 1852 was found to contain content related to the PKU 65 and SQZ C058, though this does not present a serious challenge to the novelty of PKU 65. On the other hand, this methodology is oriented towards positive authentication, but cannot prove a negative appraisal. Conflicts with newly excavated or appreciated archaeological finds might raise suspicions, especially if they consistently occur when compared against an ever more robust archaeological corpus, but do not theoretically prove forgery. PKU 65 differs with YT 1852 in its content (![]() vs bin fen 賓分, respectively), and conflicts in its implied line divisions compared to SQZ C058 and YT 1791 (breaking after shun 舜 vs after tang 湯, respectively). Yet feasible explanations can be offered to resolve these conflicts, with various hypotheses which both can and cannot be tested against new archaeological finds.

vs bin fen 賓分, respectively), and conflicts in its implied line divisions compared to SQZ C058 and YT 1791 (breaking after shun 舜 vs after tang 湯, respectively). Yet feasible explanations can be offered to resolve these conflicts, with various hypotheses which both can and cannot be tested against new archaeological finds.

The “Han Board” Cang Jie pian: Insights and Complications from Yet Another Unprovenanced Manuscript

An important development in the study of the Cang Jie pian took place in the fall of 2019, when Zhonghua shuju 中華書局 announced the publication of Xinjian Han du Cang Jie pian Shi pian jiaoshi 新見漢牘蒼頡篇史篇校釋.Footnote 83 This volume includes photographs of purportedly Han-period wooden-board manuscripts in the possession of an anonymous collector, among which is the longest witness to the Cang Jie pian currently extant. Two other primers (called *Shi pian yi 史篇一 and *Shi pian er 史篇二) and a poem (*Fengyu shi 風雨詩) are in the collection as well. The editor, Liu Huan 劉桓, provides annotated transcriptions for each text and research essays on the Cang Jie pian and the two Shi pian primers. The existence of these so-called “Han board” manuscripts was unknown to the field previously.Footnote 84

As we did with the Peking University Han strips, we once again encounter a collection of manuscripts that potentially possess immense scholarly value, but whose promise is restricted by the illicit means in which it was obtained. Lacking proper provenance, the Han board manuscripts are either looted artifacts or forgeries. While this article focuses on matters of authentication, it must be emphasized, on the former possibility, that the Han board collection presents additional anxieties over professional ethics. In deciding how to responsibly handle these materials, I still believe we must “weigh between, on the one hand, the material and intellectual losses that may be suffered in the future by further incentivizing looting and, on the other hand, the material and intellectual losses we will suffer imminently by neglecting looted artifacts already on the market, as well as the future loss of neglecting those that may surface later.”Footnote 85

Yet unlike the Peking University strips, the Han board manuscripts are held by a private collector, not a public institution. With artifacts in private collections, our evaluation is impacted by extra concerns. Access to items in private collections is more restricted. This withdraws artifacts from the realm of shared cultural heritage. It also potentially biases research on them, including their authentication. Scholarship on these objects can lead to the direct enrichment of an individual collector, who stands to benefit from positive appraisals of their collection's worth. Government oversight of public institutions helps to ensure responsible stewardship, whereas no such oversight is in place for private collections, thereby threatening the preservation of the artifacts. These are among the serious concerns that need to be weighed when treating objects in private collections.Footnote 86

My interest in the Han board Cang Jie pian manuscript, in the context of the present article, is mainly theoretical in scope and limited to the impact that the existence of such an artifact may have on our authentication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian manuscript. To this end, I briefly describe the Han board collection based on the information provided in Xinjian Han du Cang Jie pian Shi pian jiaoshi, and I survey, with minor elaboration, arguments raised by other scholars on the Han board Cang Jie pian's authenticity, which have been disseminated publicly elsewhere. This is not intended as my own authentication of the Han board manuscripts, which requires both further research and greater dialogue about the concerns raised above.

The collection contains 119 wood-board pieces, of which fifty-seven belong to the Cang Jie pian, fifteen to Shi pian yi, forty-six to Shi pian er, and one to the Fengyu shi.Footnote 87 The intact boards are approximately 47 cm long, 5.4–6.1 cm wide, and 0.6–0.7 cm thick.Footnote 88 The top and bottom ends are level. At about 1.7 cm from the top of each board there is a hole, 0.5 cm in diameter, seemingly to accommodate a binding cord, allowing the boards to be strung together into a complete text. The top of each board is painted red, running ~2.8 cm down. The writing is in black ink, in a mature Han clerical script (approaching bafen 八分), which Liu dates to sometime after the mid-Western Han.Footnote 89 On the Cang Jie pian and Shi pian boards, there are numerical labels (e.g. di yi 第一 “first”) written above the holes. The main text, however, is written in the space underneath the red coloring, in three columns. The Cang Jie pian and Shi pian yi have twenty characters per column, for sixty characters total per board; Shi pian er and Fengyu shi squeeze an additional four characters into the end of third column on their boards, for sixty-four characters total per board.Footnote 90 Unfortunately, the writing is not always clear, often leaving readers dependent upon Liu's judgments.

The Han board Cang Jie pian fits expectations for the Village Teachers edition of the text. Pertinent points to keep in mind are: (1) It adopts a format of sixty-character chapters, as mentioned in the Han shu; (2) it has chapter divisions that match those previously reconstructed for the Village Teachers edition (e.g., as seen on the gu prism JY 9.1, with the placement of the Shuiquanzi character counts, or with the placement of triangular punctuation in the British Library shavings); (3) the labels on the Han boards with Cang Jie pian content, as read by Liu, do not exceed “fifty-five” (the chapter count for the Village Teachers edition); and (4) the opening lines of Shi pian yi, found together with the Han board Cang Jie pian, refer to “fifty-five chapters that copy out the Cang Jie” (蒼頡之寫五十五章, see HB SP1 1.a). Since the boards are numbered, we can begin to piece together chapter order.Footnote 91 The manuscript bears over 2,160 characters, which amounts to roughly two-thirds of the Village Teachers Cang Jie pian's text.Footnote 92 Known or suspected Cang Jie pian content seen previously among other manuscript finds appears on the Han board witness. This includes the “opening chapter” frequently encountered among the Dunhuang and Juyan strips, as well as most of the content found in the Fuyang, Shuiquanzi, and Peking University Cang Jie pian manuscripts, including some unique parallels.Footnote 93 There is also novel content.Footnote 94 Notably absent is any content found in the “proper names” chapters, seen among the British Library, Yumen huahai 玉門花海 and Majuanwan 馬圈灣 strips, whose affiliation to the Cang Jie pian has been debated.Footnote 95

Besides the Cang Jie pian, this collection contains two other primers, which Liu titles Shi pian yi 史篇一 and Shi pian er 史篇二. Like the Cang Jie pian, both Shi pian texts rhyme every other four-character line.Footnote 96 They read in a more narrative style, akin to the so-called opening chapter of the Cang Jie pian (“Cang Jie created writing, and taught it to later generations” 蒼頡作書以教後嗣). In fact, Zhang Chuanguan 張傳官 argues that Shi pian yi board 2 is misidentified by Liu and instead constitutes the second chapter of the Cang Jie pian Village Teachers edition, serving as a continuation of the Cang Jie pian's opening.Footnote 97 Regardless, Shi pian yi itself establishes a close relationship to the Cang Jie pian, when in its first lines it makes reference to the fifty-five chapters of the Village Teachers Cang Jie pian: “When endeavoring to study writing, the boards (suited) to instruct youths, are the fifty-five chapters transcribed by Cang Jie” (寧來學書告子之方蒼頡之寫五十五章, SP1 1.a).Footnote 98 The postface to the Shuowen jiezi 說文解字 bemoans how various scholars mistakenly believed that Qin clerical script had ancient origins, and that the Cang Jie pian likewise “was the creation of ancient emperors” (古帝之所作) with “phrasing that has a mystical art about it” (辭有神僊).Footnote 99 The opening lines of the Shi pian yi may reflect such a belief. Of course, it is possible to take the final two lines here as “the fifty-five chapters that copy out the Cang Jie” instead, giving a more explicit citation of the text title.Footnote 100 Frequent mention (and veneration) of “scribes” (shi 史) and of the importance of “writing” (shu 書) likewise demonstrate the pedagogical objectives of Shi pian yi.Footnote 101

Whereas Shi pian yi is relatively short (fifteen board pieces), Shi pian er bears more extensive content (forty-six board pieces).Footnote 102 Beyond an exhortation to study, which again opens the primer, Shi pian er surveys a broad variety of topics, ranging from the origins of the cosmos and natural cycles, to family relations and expected behaviors, important life events for men and women, and the duties of rulers and officials. Finally, one board among this collection writes out a poem, referred to by Liu as the Fengyu shi. This title is not Liu's invention, but rather that of Zhang Feng 張鳳, who adopted it for a nearly identical poem written on DHHJ 2253, a wood strip collected by Aurel Stein near Dunhuang during his third expedition (1913–15).Footnote 103 The poem describes a great storm, flooding, and other natural catastrophes that encumber a traveler between Mengshui 蒙水 to Tianmen 天門.Footnote 104

Before publication, Zhonghua shuju suggested that specialists be convened to authenticate the boards. Liu apparently approached Li Xueqin 李學勤 and Wang Hui 王輝 for their opinions:

I first asked Li Xueqin to look over this data. He recommended that the physical artifacts be appraised, saying moreover that if they are real, then this an important discovery. After viewing the relevant data, Wang Hui, of Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology, thought that the annotated transcriptions and research on the Han board Cang Jie pian and Shi pian manuscripts were immensely important.Footnote 105

我首先請李學勤先生對這些資料過目,他建議對實物進行鑒定,並說這些資料如果是真的,那就是一個很重要的發現。陝西考古研究院王輝先生看過有關資料後認為,對漢牘《蒼頡篇》《史篇》的校釋與研究,是有重大意義的.

This is not the typical “authentication conference” seen with other institutional collections, such as Peking University, nor are the reported comments by Li or Wang affirmations of the boards’ authenticity, but to the contrary, rather striking in their measured avoidance of any such affirmation.Footnote 106 Following the announcement of Xinjian Han du Cang Jie pian Shi pian jiaoshi's publication and the initial release of data, skepticism arose over the authenticity of these manuscripts.Footnote 107 This skepticism was not only because the manuscripts lacked a secure provenance, or because they had yet to be subjected to scientific testing such as radiocarbon dating. Other conspicuous features on the manuscripts have invited doubt. Zhang Chuanguan mentions, for example, the peculiar writing support, as well as certain character forms, seeming “unusual” (不同尋常) and “out of the ordinary” (與眾不同) at first glance.Footnote 108

Despite these concerns, Zhang Chuanguan and other scholars recently have expressed confidence in the authenticity of the Han board Cang Jie pian. Zhang believes that: “It would have been extremely difficult to make the wood-board Cang Jie pian by stringing together previously known lines from the Cang Jie pian alone; no modern [forger] could have anticipated the new insights provided by its contents,” as these insights “surpass the present state of knowledge for research into Cang Jie pian” (筆者認爲新見木牘《蒼頡篇》是很難僅僅根據以往的《蒼頡篇》文句連綴而成的;其內容所提供的新知,絕非現代人所能臆測, and, prior to this, 這些新知恐怕已超出了現有的蒼頡篇研究水平).Footnote 109 An example would be Zhang's identification of HB SP1 2 as the previously missing second chapter of the Cang Jie pian, mentioned before, a novel feature among the Han board manuscripts that Zhang claims is verified by data not fully appreciated or anticipated before in the field (e.g., the identity of YT 1844, YT 2667, or YT 3222). Zhang's arguments are akin to those that I raise above concerning the Shuihudi verso sets and the Niya Cang Jie pian parallel in relation to the Peking University manuscript.

Irrespective of the Han board Cang Jie pian's authenticity, this manuscript does weave together known content from other Cang Jie pian finds in subtle ways, suggesting new interpretations for the older materials. This includes, for example, obviating “hidden” chapter divisions in the Village Teacher edition of the text, previously obscure (but knowable) from the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian, through changes in rhyming between SQZ C037, C038+C039, and C040 vs SQZ C114; as well as SQZ C044 vs SQZ C045.Footnote 110 Another curious implication of the Han board chapter order is that it suggests the Shuiquanzi manuscript only entails the first twenty chapters of the Village Teachers edition, with the phrase yuanli 爰歷 appearing at the end of the twentieth chapter. In intriguing ways, this information corresponds to and conflicts with the textual history given in the Hanshu Yiwenzhi, where Li Si's Cang Jie precedes the Yuanli; but the former is listed in seven chapters (zhang 章) and the entirety of Cang Jie, Yuanli, and Boxue are in twenty chapters.Footnote 111

This brief introduction aside, the concern of the present article is on whether or not the existence of the Han board Cang Jie pian impacts our evaluation of the Peking University Cang Jie pian manuscript's authenticity, and not on the authenticity of the Han board Cang Jie pian. Since the Han board Cang Jie pian does not constitute archaeologically excavated data, it cannot be used positively to confirm features once novel to the Peking University Cang Jie pian, unless and only until the Han board Cang Jie pian itself is first properly authenticated.Footnote 112 Even then the evidence would by necessity only be indirect and thus not ideal.Footnote 113 It is crucial, moreover, to establish a timeline for the acquisition, study and publication of the Han board cache, to understand how this data relates to the timing of that for the Peking University bamboo strips. Only then may we judge the relative novelty of features on these manuscripts and the potential for access to this information by theoretical forgers.

Public announcement and dissemination of Xinjian Han du began in the fall of 2019, which marks our most conservative terminus ante quem for the existence of the Han board data. The date of publication listed on the volume itself is June of 2019, and Zhonghua shuju inevitably required a period of time beforehand for editing and other preparations.Footnote 114 Whether or not the Han board data existed prior to this point, and if so for how long beforehand, is uncertain. Liu reports that: “In the autumn of 2009, I was fortunate enough to inspect a collection of wooden boards at a friend's residence in Beijing, and obtain photographs of these artifacts” (二〇〇九年秋,在北京一友人處,我有幸獲觀一批木牘並得到實物的圖片資料).Footnote 115 Liu does not discuss anything more about who the collector may be or the date of the boards’ acquisition by them. If this report is to be trusted, a fall 2009 terminus ante quem comes before the public release of substantial data on the Peking University Cang Jie pian manuscript. Without knowing how much time passed between when the Han board manuscripts appeared on the illicit antiquities market and their inspection by Liu, it is also possible that the Han board Cang Jie pian circulated before the appearance of the Peking University manuscripts.

Liu describes his work on the Han board collection in more detail within the postscript of Xinjian Han du, where he states that he completed an initial draft of his annotated transcriptions by the spring of 2013, and then briefly updated them following publication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian. The postscript itself is dated August 2018. We must take Liu at his word for this timeline, and certain internal evidence from the Xinjian Han du coincides well with these dates, including: (1) The latest works cited in the volume are from 2016;Footnote 116 (2) Liu does not make use of Zhang Cunliang's dissertation and the updated information available therein for the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian;Footnote 117 (3) Liu's introduction mentions “partial (data) for the Beida witness already published” (北大本已發表的部分), implying the Peking University manuscript was not yet fully published when this was drafted;Footnote 118 and potentially (4) how Liu has structured his annotations, especially the order in which he lists parallels between the Han board and other Cang Jie pian manuscripts, in the “Shuoming” 說明 sections.Footnote 119 I document these patterns here as potentially fruitful avenues into corroborating the textual history of Xinjian Han du itself.

While the timeline given above remains uncertain, if we take it at face value we must confront another problematic scenario: that a forger used the (in this case theoretically genuine) Han board manuscript to create the Peking University Cang Jie pian, at some point before either were attested (pre-2009). We may exclude this possibility since, despite the great overlap in content between these two manuscripts, there are novel features on the Peking University Cang Jie pian that are not seen on the Han board Cang Jie pian, confirmed by newly excavated or appreciated archaeological data. The textual parallel between PKU 64 and SQZ C088, C108 and C092 remains unique to the Peking University and Shuiquanzi manuscripts. This is true for part of the PKU 40 vs N.XIV.20 parallel as well. There is also content on the Peking University Cang Jie pian that is still unattested elsewhere, awaiting further discoveries for confirmation.

The surprising publication of the so-called Han board Cang Jie pian manuscript held in a private collection does, however, highlight how tenuous claims for novelty can be when used for authentication. A possibility we cannot exclude, for instance, is that there is a third manuscript—looted, but genuine—also in a private collection but unknown to the field, acquired prior to the Peking University Cang Jie pian, based on which a hypothetical forger could have drawn inspiration for replicating textual content, material features, or both. Although I find it infeasible, an even more troubling proposition is that such knowledge could then have been used to manipulate looted ancient bamboo strips, which were prepared or bound already, but left blank without any writing.Footnote 120 The reason I find this infeasible is that it presumes writing on waterlogged strips, kept in an orderly fashion, which preserves information such as the original verso line relationships.Footnote 121 Yet if we do allow for this, we may confront a situation where an act of modern forgery combines both physical materials and textual content of genuinely ancient origins. It is a scenario that might challenge our very understanding of “authenticity” itself.

Conclusion

Recent developments in the study of early Chinese manuscripts and the Cang Jie pian have brought to light new data and understandings which bolster the positive authentication of the Peking University Cang Jie pian. The archaeologically excavated Liu nian zhiri manuscript from the Shuihudi Han cache confirms the existence of verso “sets,” a novel feature found on several unprovenanced manuscripts from the Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Yuelu Academy collections, raising our confidence in these collections more generally. For the Peking University Cang Jie pian in particular, novel overlaps have been found between a newly identified strip from Niya (N.XIV.20) and recently released data on the Shuiquanzi Cang Jie pian. These observations provide additional evidence that the Peking University Cang Jie pian is indeed genuine.

Yet the conversation above is also cautionary. My methodology for appraising the Peking University Cang Jie pian is based on showing that novel features on the unprovenanced manuscript, unattested and unanticipated before its acquisition, are later confirmed through new archaeological discoveries. This approach is concerned with positive authentication, which limits its usefulness for negative appraisals. More importantly, it depends upon judgments about the “novelty” of features and archaeological controls. It is difficult, if not impossible, to establish novelty definitively. The belated recognition of YT 1852 as an additional witness to the overlap between PKU 65 and SQZ C058, and the consequent conflicts in wording and line divisions, demonstrate both of these points. The publication of the Han board Cang Jie pian, supposedly long in the possession of a private collector but unknown to the field at large, is an even starker example. No matter how confident our appraisal, assessments about authenticity must be continuously revisited and are liable to change as additional information comes to light.