Introduction

Temperance was the first national social movement in US history (Young Reference Young2002, Reference Young2006). The movement exploded on the national scene in the late 1820s and within half a decade advocates were organizing mass support for the cause in every state. Abolitionism soon followed, challenging and eventually uprooting the very foundation of antebellum America. The support for each movement was not only extensive but also enduring. The organizations and conflicts triggered by temperance and abolitionism left deep marks on American history, affecting nearly every political, economic, civic, and religious institution in the country (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Morone Reference Morone2004; Rorabaugh Reference Rorabaugh1979; Young Reference Young2006).

For a century, temperance was implicated in the nation’s most significant public battles: abolitionism, women’s suffrage, prohibition, and partisan contention and alignments. The antislavery movement that followed in temperance’s wake was instrumental in the young nation’s turbulent march to civil war. Due in large part to their important roles in shaping American history, these social movements’ origins have been hotly contested. From the earliest years of the movements, scholars have attempted to explain mobilizations against the hard-drinking ways of antebellum Americans and against the American institution of slavery (Krout Reference Krout1925; Martineau Reference Martineau1961; Tocqueville Reference Tocqueville1994). Varied and competing accounts have featured the mainstays of sociological explanation, including status struggle, class conflict, state building, and contentious politics (Blocker Reference Blocker1989; Gusfield Reference Gusfield1986; Levine Reference Levine1984; Rumbarger Reference Rumbarger1989; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997, Reference Skocpol2013; Tarrow Reference Tarrow, Costain and McFarland1998; Tyrell Reference Tyrell1979). As a whole, these explanations betray a social-scientific incredulity that early temperance advocates and abolition activists were motivated by the religious convictions they publicly avowed. To be sure, no serious account of US temperance or abolitionism ignores religion altogether, but most of them perceive more powerful forces operating behind the movements’ religious faces.

We contend that the origins of the American temperance and antislavery movements were deeply religious and that their expansions were fueled by religiously motivated actors. The mass appeal and national spread of both temperance and abolitionism cannot be disassociated from the “Second Great Awakening” driving missions, revivals, and religiously motivated moral actions during early-nineteenth-century America. Before temperance became more closely associated with class conflicts over industrialization (Gusfield Reference Gusfield1986), nativist struggles against Catholic immigrants (Higham Reference Higham2002), or state building and contentious party politics (Freeman Reference Freeman2002; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997), it was a religious struggle against perceived sins. It was a confessional movement aimed at transforming the moral lives of Americans (Young Reference Young2002, Reference Young2006). As early as 1830, temperance was a national form of “life politics” (Calhoun Reference Calhoun1993, Reference Calhoun2012; Giddens Reference Giddens1991). We also argue that this form of life politics and religious activism similarly and directly influenced the formation and spread of American abolitionism as a social movement.

In terms of these two movements’ central issues, slavery and drinking, at face value these topics seem very different. But, in both cases, the issue was deemed a sin that imperiled the nation’s fate. The two movements also shared a strikingly similar form of collective action, bearing witness against a particular sin and confessional protest. Both movements judiciously avoided party politics and did not directly challenge the state, choosing instead to exert influence on civil and religious institutions. And in these campaigns of moral suasion through confessional protest, both movements relied heavily on the support of women. In spite of these similarities, salient differences, not unrelated to the issue focus of their respective causes, distinguished the course of temperance from antislavery. Temperance was much more popular as a movement, and it gained some support even in the South. In contrast, abolitionists’ attempts to organize in the South were swiftly met with legal and violent repressions. And even in the North, antislavery positions proved very controversial, with antislavery meetings dogged by antiabolitionist mobs. Temperance advocates faced down the occasional mob, but never attracted anything like the same level of violent countermobilizations as abolitionists.

The emergence of American temperance and abolitionism as mass movements across the 1820s and 1830s is highly amenable to empirical investigation. In these early phases of the movements, single prominent organizations represented each cause: the American Temperance Society (ATS) and the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), respectively. Because of their sole representation of American temperance and abolitionism, these voluntary associations’ accountings of their first auxiliary societies provide excellent measures of the timing and diffusion of the movements’ growth. Events in New York State were decisive to both movements’ national development. The popular spread of temperance across New York in the early 1830s demonstrated that the issue was not a New England peculiarity but was indeed an emerging national phenomenon. And in 1833, William Lloyd Garrison, backed by the considerable reputation and resources of Arthur and Lewis Tappan, officially established the Anti-Slavery Association in New York City. Within five years the movement rapidly grew and expanded its reach, establishing an estimated 1,350 local chapters sustained by almost 250,000 members (American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) 1835–1838; Young Reference Young2006). The actions and institutions of New Yorkers during this period were recorded in surprising detail. In this study, we compile county-level data on economy, politics, civil society, and religious institutions and activism in New York State during the 1820s and 1830s to analyze the temperance and antislavery movements’ early growth patterns.

Overall, we make three significant contributions to the literature on US social movements. First, we introduce new historical data to analyze the emergence of the US temperance and antislavery movements in New York State between 1828 and 1834, and 1835 and 1838, respectively. These county-level data reveal substantial variation in the support for these movements across New York State. Second, we examine the associations between these social movements and the economic, political, and religious characteristics of New York counties during each movement’s critical takeoff period. Results suggest that evangelism associated with the Second Great Awakening was influencing both the establishment and growth of temperance and antislavery societies in New York State. And third, we pay close attention to different dimensions of religion to delineate its influence on the spread of both temperance and abolitionism in New York State. Specifically, we differentiate the institutional and organizational capacities of established clergy from the more evanescent cultural dynamics or life politics of the Second Great Awakening. Together, we provide strong empirical evidence to suggest that the emergence and growth of the US temperance movement and US antislavery movement in New York State were substantively associated with the cultural and mobilizing forces of the Second Great Awakening.

Background

Local voluntary associations supporting temperance in the United States are documented to have existed as early as 1789, but these associations’ activities did not coalesce into an organized and interregional movement until the late 1820s (Kett Reference Kett1981; Rorabaugh Reference Rorabaugh1979; Tyrell Reference Tyrell1979). Once begun, the national growth of temperance was not gradual but explosive. The ATS, established in Boston in 1826, led and coordinated the national growth of the movement. Within five years of the organization’s founding, auxiliary ATS societies could be found in every state of the Union (see figure 1). By the mid-1830s, the organization claimed to have more than 8,000 auxiliary societies and 1.5 million members, suggesting that upward of 10 percent of the US population was involved in the movement (American Temperance Society 1834; Morone Reference Morone2004).

Figure 1. National growth of American temperance society auxiliary societies, 1827–30.

Source: Journal of Humanity, 1831.

Note: Each dot represents an auxiliary society formed that year.

The ATS was the first national social movement organization in US history, and for roughly a decade it was the organizational representative of the first US social movement to mobilize and sustain mass support across the nation. The AASS was established in New York City in 1833 and quickly amassed strong following represented by about 1,350 local chapters. Unlike the national reach of the ATS, auxiliary societies of the AASS were established only in northern states. The national-level organization of the AASS split in 1839 over disagreements regarding tactics, aims, and its ties to established religion. While the organizational capacity of the movement was fractured after that point, the AASS did not formally disband until after the Civil War in 1870.

The early US temperance movement and early US antislavery movement shared many characteristics with the first national social movements documented to occur in Great Britain and France in the early nineteenth century (Tilly Reference Tilly1986, Reference Tilly1993). As in these European cases, US temperance advocates and abolitionists organized modular forms of association to spread their special-purpose campaigns across multiple regions of the country (Hanagan et al. Reference Hanagan, Moch and Brake1998; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994; Tilly Reference Tilly1993). The national spread of temperance and abolitionism in no small part followed the organizational spread of auxiliary societies to the ATS and AASS, respectively. In communities across the expanding nation, Americans came together to formally support the national organizations and their respective causes. For instance, the early supporters of the national temperance movement all signed the same pledge to abstain from consuming alcohol and adhered to the same core principles defined by the ATS (Young Reference Young2006).

Certain features of each movement, however, clearly distinguish temperance and abolitionism from the state-centered and labor protests of Western Europe (Tilly Reference Tilly1986, Reference Tilly1993). First, the early temperance movement emphasized personal and lifestyle changes over material and political ends (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Young Reference Young2001, Reference Young2002, Reference Young2006). The temperance pledge that united millions of Americans in a national cause was a voluntary commitment by individuals to reform their own drinking habits and to lead national change by personal example. Second, in advancing their cause, the early advocates publicly rejected direct involvement with state institutions and political parties (Calhoun Reference Calhoun1993; Mathews Reference Mathews1969; Young Reference Young2002). The supporters of temperance aptly described their movement as one of “moral suasion,” distinguishing it from the coercive actions of the state and the “corrupt” motives of party politics (American Temperance Union 1852). Tocqueville (Reference Tocqueville1994: 250) commented that temperance actors “regard[ed] drunkenness as the principal cause of the evils of the state, and solemnly bound themselves to give an example of temperance” (emphasis added).

These distinct features of temperance pose difficulties for the contentious politics perspective, the leading comprehensive sociological theory for the emergence of national social movements in the nineteenth century (Hanagan et al. Reference Hanagan, Moch and Brake1998; McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly1996; Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994; Tilly Reference Tilly1993). From this perspective, the centralization of state power presented citizens with the political opportunities to organize “mass action that was more consciously public, formal, national, and autonomous” than the particularized, localized, and patronized forms of earlier collective actions (Hanagan et al. Reference Hanagan, Moch and Brake1998: 17). According to Tilly (Reference Tilly1986, Reference Tilly1993) and Tarrow (Reference Tarrow1993, Reference Tarrow1994), strategic interaction with centralizing state institutions provided a key mechanism to lift actors out of their particular and parochial routines of protest, focusing instead on new and extensive lines of collective action by articulating novel claims pitched at a national entity. As state building expanded and centralized authority, it penetrated local communities, which, in turn, provided a target for protests and causes that superseded local concerns. As challengers targeted centralized state agencies they necessarily altered their forms of collective action. Protests became modular, the objects of their claims turned national and specialized, and the modern social movement was born.

This theory fails to capture the distinct features of the early US temperance movement, as its actors were not motivated by institutional-political ends, nor were their activities directed at the state. These points aside, political and state institutions may still have played a decisive role in the rise of the temperance and antislavery movements. In her historical analysis of American voluntary associations, Skocpol perceives social movements to be state centered and calls attention to the changing dimensions of American political institutions during the early nineteenth century (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997, Reference Skocpol2013; Skocpol and Fiorina Reference Skocpol and Fiorina2004; Skocpol et al. Reference Skocpol, Ganz and Munson2000). In the interregional character of temperance, Skocpol sees the stamp of the state and party politics. She observes that the national temperance organization and similar special-purpose associations like the AASS emerged at a critical juncture of mass party politics and state expansion. The American state, Skocpol argues, facilitated “associationalism” through a far-reaching and efficient postal system and an expanding transport infrastructure of canals and turnpikes (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997). More directly, she argues that the activists behind these national voluntary associations learned how to mobilize a mass and interregional constituency from their experiences in the unfolding political revolution of the rise of mass political parties (Skocpol and Fiorina Reference Skocpol and Fiorina2004; Skocpol et al. Reference Skocpol, Ganz and Munson2000).

An alternative to these political institutionalist views is to see the early US temperance movement and US antislavery movement as essentially religious struggles unfolding at considerable distance from politics and state institutions. Although political forces were undeniably influential in abolitionists’ organizing strategies, the religious struggle for temperance operated outside of formal political circles. In a young but increasingly evangelical nation, intemperance appeared as a dangerous violation of a divinely sanctioned culture of industrious self-control (Morone Reference Morone2004; Rorabaugh Reference Rorabaugh1979). As such, the temperance movement organized to evangelize against this perceived sin. Self-discipline, public confession, personal reformation, and denouncing the sin of intemperance were the primary foci of the early US temperance movement. These individual and religious ends were pursued not through contention within or against institutional politics, but rather through moral challenges within civil society. Indeed, politicizing temperance and pressuring the state for changes in drinking laws were not central features of the movement until the mid- and late nineteenth century (Kett Reference Kett1981; Young Reference Young2006). For the first decade of the movement, the favored pressure tactics of temperance actors involved delivering sermons and lectures, publishing articles and religious tracts, and, above all, directly calling on Americans to bear witness to their sins in very public ways. These tactics were deployed in America’s churches, public halls, parlors, town squares, newspapers, and magazines (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012). As such, contemporary theories of “life politics” better explain the emergence and early support for American temperance (Calhoun Reference Calhoun1993, Reference Calhoun2012; Cohen and Arato Reference Cohen, Arato, Honneth, McCarthy, Offe and Wellmer1992; Diani Reference Diani1992; Giddens Reference Giddens1991; Taylor and Whittier Reference Taylor, Whittier, Freeman and Johnson1999; Young Reference Young2002). Temperance fed on the practices of the nation’s religious revivalists, home missionaries, and other religious actors in benevolent societies advancing evangelical Christianity (Young Reference Young2002, Reference Young2006). From a life politics perspective, temperance advocates did not so much learn from party politics or depend upon the state infrastructure as they modeled the evangelizing practices of the Second Great Awakening (Abzug Reference Abzug1994; Hankins Reference Hankins2009; Mathews Reference Mathews1969; Walters and Foner Reference Walters and Foner1997). As Morone (Reference Morone2004: 123) notes, “by 1830 the [Second Great] Awakeners had organized a network of institutions designed to rival political parties, save the nation, and redeem the world.” Calhoun (Reference Calhoun2012: 35) echoes this point, suggesting that early-nineteenth-century America “proved fertile ground for an even more diverse range of social movements than any European country … and all had roots in the Second Great Awakening, a religious revitalization that amounted to a social movement—or cluster of social movements—in itself.”

This religiously informed perspective of life politics is not new. Historians have long recognized associations between the dramatic rise of support in evangelical Christianity known as the Second Great Awakening and the national movement to stop alcohol consumption and the subsequent push for the abolition of American slavery. The ATS was modeled after the missionary organizations of Congregationalists and Presbyterians and tapped these resources as it launched its national crusade (Griffin Reference Griffin1957). Further, popular temperance lecturers learned their craft of persuasion from religious revivalists of the time, and early temperance meetings modeled the template of public confession (Johnson Reference Johnson1978). In most historians’ accounts, however, the associations between the Second Great Awakening and American temperance and abolitionism rarely stand as evidence for religious mechanisms driving the movements’ growth. Even the most insightful analyses of the relationship between religious revivals and temperance are blunted by the assumption that market forces were prompting these evangelical forces to react to changing economic conditions (Gusfield Reference Gusfield1986; Rorabaugh Reference Rorabaugh1979; Ryan Reference Ryan1992). As such, a market revolution, as opposed to a religious revolution, is ultimately to credit or blame for the US temperance movement.

Economic explanations usually take one of two forms. The most popular sees temperance as buffeted by an ascendant middle class that came to understand and justify its privileged place in the American marketplace as a result of pious self-control. Accordingly, while evangelical Christianity justified the crusade against alcohol and provided the collective ritual of bearing witness against sin, the spread and success of temperance ultimately had more to do with capitalist imperatives of disciplined labor and individual responsibility. Moreover, this perspective often emphasizes the cultural and material expectations of an emerging class shaped by perceived fears and aspirations of women and mothers (Ginzberg Reference Ginzberg1990; Johnson Reference Johnson1978; Ryan Reference Ryan1975, Reference Ryan1992; Tyrell Reference Tyrell1979; Young Reference Young2002). A second perspective sees temperance advocates as victims, not agents, of the market revolution. It views the rise of the temperance movement as a status struggle of an agrarian elite losing its hold on economic and political power with the advance of capitalist markets. The agrarian elite used its considerable control over churches to try to stem the tide of market forces and the growing influence of an urban-based commercial culture (Gusfield Reference Gusfield1986). A common reductive tendency in these economic and class accounts is to treat religion as an organizational tool enlisted for profane purposes. Like resource mobilization accounts in the social movement literature, the power of religion is appreciated mainly through its capacity to organize actors using church leaders and/or institutional spaces.

But explanations that look only to the organizational role of churches and clergy fail to consider the critical shifts in American religious practices animated by the Second Great Awakening. Revivals expressed religious fervor and conflict that challenged the authority of local churches and clergy (Abzug Reference Abzug1994; Morone Reference Morone2004). Further, benevolent organizations such as the American Bible Society (established 1816), the American Tract Society (established 1825), and the American Home Missionary Society (established 1826) were deployed to reorganize frontier American morals beyond the reach—and sometimes in direct conflict with—organized churches. Thus, these religious efforts acted largely outside the purview of the governing structures of churches and instigated inter- and intradenominational fractures.

We do not doubt that religious forces interacted with both market and economic forces in driving the rise and spread of early US temperance, as well as in the subsequent growth of the first American antislavery societies. We also think that the religious forces associated with temperance and abolitionism were interacting with political processes insofar as they were rejecting the electioneering practices of political parties. As Morone (Reference Morone2004: 123) notes, it was the “people who were barred from party politics” who “flung themselves into the business of salvation.” We caution, however, that links between religion and macro- and meso-level political and economic forces should not distract from the evangelical sources of the temperance and antislavery movements that were operating at lower levels of social life. Explaining temperance as an evangelical campaign against perceived sin is in no way less sufficient than seeing it as the contentious politics of shopkeepers trying to control wage laborers or a status struggle by a declining agrarian-based elite. We aim to revive the central argument that the emergence and spread of US temperance and abolitionism were strongly driven by culturally based religious forces, which were tied directly to the activist elements of the Second Great Awakening. Religious forces beyond the institutional arms of economy, politics, and even churches, fueled the nation’s first social movement, temperance, and the nation’s most disruptive social movement, abolition. The crusading power of benevolent societies and religious revivals called on Americans to bear witness against the threatening sins of intemperance and human slavery. Indeed, these forces were instrumental in the formation and spread of both the US temperance movement and the subsequent antislavery movement. Both movements borrowed directly from the fervor, schema, and organizational strategies of revivalists and crusaders of benevolent societies.

Current Aim

We analyze the onset and growth of US temperance and abolitionism using historical data composed of New York counties between 1828 and 1838, a period that captures the national takeoff of each movement. We examine the spatial and temporal patterns of the American temperance and antislavery movements in New York State by modeling the movements’ early diffusion with changes in counties’ demographic, political, economic, and religious characteristics of the time. Our specific interest is in examining if and how religious forces were shaping the movements’ early growth in New York State. We measure separately the institutional infrastructure of religion provided by churches and clergymen, the emergence of an innovative national missionary movement, and the spread of public confessions through revivals across New York in the 1820s and 1830s. Such measures allow us to separately explore how the organizational capacity of religion and the religious-cultural practices of public confession were each associated with the emergence and spread of the US temperance and antislavery movements in New York State.

Several characteristics of New York make it an excellent case for studying the early growth of American temperance and abolitionism. First, the spread of temperance throughout New York State helped to demonstrate that temperance was not a parochial New England reform issue, but an emerging national movement. By the early 1830s, temperance societies had been established in 28 states, and New York contained more auxiliaries to the ATS than any other state in the union (see figure 1). Moreover, perceived successes in New York State were catalysts for temperance actors in other states, who also emulated the tactics of New York temperance advocates (Massachusetts Council on Temperance 1836). Regarding abolitionism, the AASS’s headquarters were in New York City and the actions of New Yorkers were instrumental in the movement’s early growth. Second, New York was culturally, demographically, and economically diverse for the time. Americans from New England and the mid-Atlantic came together in mass migrations, pushing the state’s westward expansion. In the 1820s and 1830s, New York State not only underwent rapid demographic change but also economic, political, and religious transformations. During these decades, agricultural and industrial capitalism flourished, fueled in part by the opening of the Erie (1825), Chemung (1833), and Chenango (1837) canals and other networks of transportation and commerce. Third, political institutions in the state rapidly democratized, and with the rise of the Bucktails (1818–26)Footnote 1 , New York took a national lead in revolutionizing electoral politics (Wallace Reference Wallace1968). Fourth, New York was at the heart of the religious ferment of the Second Great Awakening. During the 1820s, Charles Finney’s traveling revivals stirred religious sentiments throughout the state (Finney Reference Finney1876; Johnson Reference Johnson1995; Young Reference Young2006), and nearly saturated certain regions (e.g., see the “Burned-Over District” [Cross Reference Cross1950]). Also, home missionary societies seeking to evangelize the young expanding nation took particular aim at New York State as a gateway to the West (American Home Missionary Society 1827–34; Schermerhorn and Mills Reference Schermerhorn and Mills1814). Taken together, the demographic, political, economic, and religious dynamics of early-nineteenth-century New York State make it an ideal case to analyze the associations between early US temperance and antislavery activity and various religious, socioeconomic, and political forces of the time.

We hypothesize first, that religious revivals and home missionary societies were both significantly and substantively associated with the onset and growth of temperance and antislavery in New York State. Second, we hypothesize that beyond their association with revivals and home missionary societies, churches, and clergy were not associated with the onset and growth of temperance and antislavery societies. Third, we also hypothesize that the growth of temperance societies was positively associated with the subsequent growth of antislavery societies. Together, we contend that the US temperance movement had more than just a religious face. Churches in and of themselves did not stoke the moral fervor that fueled temperance and abolitionist activism. Nor did the teachings, sermons, or leadership of the clergy. Rather, it was the transformational religious passion stemming from the Second Great Awakening that drove temperance advocates to organize and sustain the nation’s first social movement. And both the religious advocacy driving temperance and the organizational tactics employed by ATS members influenced the subsequent formation and spread of the antislavery movement in New York State.

Our hypotheses are predicated on the following points. First, for more than three decades in the early nineteenth century, evangelical fervor fueled religious activism in the United States, peaking in the mid-1830s. Throwing aside the Calvinist orthodoxy of Congregationalism and Presbyterianism, this Second Great Awakening liberated the individual from dogma by promising salvation to anyone committed to repentance. At the same time, religious missions pushed for the expansion of a “benevolent empire,” stressing that sin was collective as well as personal, and fulfillment of prophecy necessitated the democratization of salvation (Calhoun Reference Calhoun2012; Young Reference Young2006). As Morone (Reference Morone2004: 130) recounts, “on the one hand, the revival fostered individualism, egalitarianism, and a faith in historical progress. It seized moral authority from the pulpit and invested it in ordinary men and women…. On the other hand, the revival kindled that hoary—nonliberal, non-Jacksonian—American passion for uplifting the neighbors.” The combined effect of individual salvation coupled with the collective push to establish a “benevolent empire” led to a host of evangelizing societies determined to transform the moral landscape of Antebellum America through public confession. The culmination of this religious struggle helped shape the cultural and political landscape of nineteenth century America.

Analytical Strategy

Data

We use original data that provide a detailed view of the early stages of the US temperance movement and the US antislavery movement in New York State. Five waves of data spanning seven years of time allow us to measure the onset and growth of temperance societies in New York as outcomes of time-specific county-level factors between 1828 and 1834. Four waves of data spanning 1835 through 1838 are used to analyze the onset and growth of antislavery societies in New York.

All measures were collected from the 1825 and 1835 New York State censuses, the 1820, 1830, and 1840 US Federal censuses, Annual Registers of New York State for years 1830–37, two datasets from the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), and the New York State Archives. The New York State Census data were obtained from the New York State Archives in Albany, New York; the ICPSR data sets were obtained from the consortium’s website; and the data from the Annual Registers of New York were obtained from the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin as well as the New York Public Library using the Hath Trust Digital Library (https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002132012).

Outcomes

We analyze both the onset and growth of temperance and antislavery societies, and therefore have four outcome variables. Our first interest is the time by which New York counties had established their first temperance society and the time by which counties had established their first antislavery society. The outcomes for these analyses are binary (1/0), with a value of one indicating that at least one temperance society, or at least one antislavery society, was established in county i during year j, and a value of zero indicating that no societies had been established in county i during year j. Our second set of analyses looks at the growth of temperance societies in New York counties between 1828 and 1834, and the growth of antislavery societies between 1835 and 1838. The outcome for these analyses is the count of societies in county i per 10,000 population during year j.

Three sources provided counts of New York State temperance societies between 1828 and 1834. The first set of counts for the time 1828 to 1831 was obtained from both the Journal of Humanity, 2 (48) 1831, and the 1829 Annual Report of the ATS. In the spring of 1831, the Journal of Humanity, an official publication of the ATS, published the location of every auxiliary society in the country. The founding date was reported for the majority of societies, but these records varied by year. Founding year is known and recorded in publications for years 1829 and 1828, but less is known for 1830 and 1831. Counts in the Annual Report of the ATS published in January of 1829 corroborate the Journal’s account of societies formed by 1828. Although the counts of societies from the two sources strongly correspond with each other, there are some minor discrepancies, so we pooled the counts. To assure consistency between the sources, we verified that the pooled count for societies formed by 1829 matched nearly identically the aggregate count reported in the 1830 Annual Report for New York State. The 1831 count, which reflects all the societies reported in the Journal plus those in the 1829 Annual Report, is also nearly identical to the aggregate count reported in the 1831 Annual Report. The second set of counts for 1833 and 1834 was obtained from the Annual Reports of the New York State Society for the Promotion of Temperance, the state auxiliary to the national temperance society (NYSPT 1833–34). These two reports published the total number of societies registered in each county in each year. Although measurement validity among the three sources is a concern, the merged figures for 1829 and 1831 are highly consistent with fitted polynomial trend lines for counts in 1828, 1833, and 1834. The outcome variables of the county-level datasets are therefore the existence (1/0) and counts of temperance societies per New York county in 1828, 1829, 1831, 1833, and 1834. Yearly counts of antislavery societies in New York counties between 1835 and 1838 were obtained from 1835–38 AASS Executive Committee’s Annual Reports. These were obtained from the New York State Archives in Albany, New York. To ensure stationary units over time, 1825 county borders were used to mark the geographical territories for all years of analyses. Because borders did in fact change between 1825 and 1838, mergers of county data after 1825 were necessary for a handful of counties.Footnote 2

The separate county-level datasets, each containing 55 counties, were merged and transformed into county-period data, resulting in a final county-period dataset with a sample size of 275 county-years spanning 1828 through 1834 for analyses of temperance societies. For analyses of temperance onset, we right-censor all county-years after a temperance society had been established. The dataset used to analyze the onset of temperance is composed of 92 right-censored county-years and ends in 1833, when every New York county had established at least one temperance society. For analyses of antislavery societies in New York State, the 55 counties compose 220 county-years spanning years 1835 through 1838. For analyses of antislavery onset, we right-censor all county-years after an antislavery society had been established resulting in 123 county-years between 1835 and 1838.

Second Great Awakening and Religious Institutionalism

To capture religious activities associated with the Second Great Awakening, we use time-varying measures of counts of religious revivals and counts of home missionary societies in each New York county. We measured county-level religious institutionalism by the time-varying number of Presbyterian and Congregationalist clergy in each county. All three variables were standardized by 10,000 population and due to skewed distributions were transformed to the natural log scale and centered on their respective mean values. Population reports from the 1825 and 1835 New York State censuses and the 1830 and 1840 US Federal censuses were used to compute mean annualized population growth rates for the five-year intervals between 1825 and 1830, 1830 and 1835, and 1835 and 1840. These growth rates were then used to estimate county populations in 1828, 1829, 1831, 1833, and 1834; and again, for county populations in 1835, 1836, 1837, and 1838 (Preston et al. Reference Preston, Heuveline and Guillot2000).

The time-varying measure of Presbyterian and Congregationalist clergy per 10,000 population, 1830–37, was used as an interval-level proxy of counties’ “orthodox” religious infrastructure between 1828 and 1834 and between 1835 and 1838. These data were obtained from Annual Registers of New York State, 1830–37. A second time-invariant count of the number of Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches in 1830 was recorded from the Minutes of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church.Footnote 3 Time-varying cumulative ratios of revivals per 10,000 population between 1828 and 1834 were calculated using revival counts in New York State counties as reported by John L. Hammond (Reference Hammond2007) in ICPSR-7754. These represent the number of revivals that had taken place in a county since 1825, per 10,000 population. Temperance leaders reportedly drew heavily from the language, style, and crusading nature of the revivalists of the time (Rorabaugh Reference Rorabaugh1979). As such, this cultural phenomenon is believed to have been highly associated with both the onset and growth of American temperance. A time-invariant indicator of the total number of revivals that occurred prior to 1835 was used to estimate the association between revival activity and onset and growth of antislavery societies, 1835–38.

The number of home missionary societies per 10,000 population in 1828, 1831, and 1834 were obtained from the Annual Reports of the American Home Missionary Society (1827–34). Home missionary societies were formed by an interdenominational and nationally coordinated effort to evangelize the newly settled regions of the expanding US nation. Missionary societies sponsored young ministers or seminary students who committed themselves to the cause of evangelizing in the expanding US frontier. These voluntary associations attracted evangelicals from orthodox roots committed to a dynamic evangelism that was often resisted by conservative churches. Supporters of the American Home Missionary Society experimented with new ways of proselytizing that moved beyond the customs of traditional clergy. These home missionary societies represented the cutting edge of a religious evangelism within orthodoxy that is argued to have provided a direct model for temperance and antislavery activism (Young Reference Young2006). We use a time-varying indicator of the number of home missionary societies per 10,000 population between 1828 and 1834 to estimate their association with temperance activity. Because the measure ends in 1834, we use a time-invariant binary indicator of a county having had relatively “high” levels of home missionary activity between 1828 and 1834 to estimate their association with antislavery activity between 1835 and 1838.

Controls and Measures for Alternative Explanations

Basic demographic controls such as a county’s population size, population growth rates, and number of towns in each county were included in our analyses. In addition to these population controls, the effect of time was included in all models. Because counts of temperance societies were recorded at different points in a calendar year, the time metric is a four-month period. A linear functional form of time best approximated the hazard rate of counties establishing both temperance and antislavery societies. A cubic functional form of time best fitted the growth of temperance societies and a quadratic functional form best fitted growth in antislavery. To further control for basic county demographics, we included a dummy variable indicating whether a county had a major urban center, and time-varying indicators of a county’s sex ratio, and the ratio of newspaper publications per 10,000 population. Newspapers were a vital resource to mobilizing early US voluntary associations (Hall Reference Hall2006; Nerone Reference Nerone2011), and print media were especially featured among antislavery advocates (King and Haverman Reference King and Haveman2008). We also included fixed effects indicators of the counties’ regions in the state.

To measure economic processes associated with a market revolution we include a time-varying measure of the presence of factories per county, cubic yards of domestically produced textiles per 100 population in 1825, and the percent reduction in domestically produced textiles between 1825 and 1835. We include similar measures for the antislavery analyses, including domestically produced textiles in 1835 and the percent reduction in these textiles between 1825 and 1835. The factory and domestic textile variables measure the presence and extent of textile market, and serve as proxies for the “changing parameters of a basically agricultural home economy” to “an era of burgeoning industry” (Ryan Reference Ryan1975: 102). These transitions were fundamental social changes that may have influenced the emergence of the US temperance and antislavery movements (Gusfield Reference Gusfield1986).

To test politically centered explanations of temperance and abolitionism, we included several county-level measures of political institutionalism, including measures of political participation and measures of institutional nation-state formation. Participation measures were obtained from the New York State censuses of 1825 and 1835, and from ICPSR-0001, “United States Historical Election Returns, 1824–1968.” The percent of the male population in 1825 eligible to vote, as well as the percent change in voting population between 1825 and 1835 were included to account for what Skocpol (Reference Skocpol1997) called a “moment of intense electoral participation and competition” when the “mobilization of eligible (white male) voters was at an all-time high during the most competitive phases” of the US party system (467). The 1831 and 1835 New York State Annual Registers were referenced to measure counts of post offices in each county, an important state institution of this time. Like newspapers, the postal service was a critical resource for mobilizing participants to the temperance and antislavery causes (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997; Skocpol et al. Reference Skocpol, Ganz and Munson2000). Indeed, it has been argued that the institutional channels of the postal service “furthered ever-intensifying communication among citizens, pulling more and more Americans into passionate involvements in regional and national moral crusades and electoral campaigns” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997: 463). We examined the effects of the US Postal Service on the early formation of New York temperance societies and abolitionist societies by including the number of post offices per 10,000 population in 1831 and 1835, respectively.

Methods

To test our hypotheses about the onset of temperance and antislavery in New York State we fitted four clog-log survival models using Stata 15’s cloglog module. First, we tested the association between the onset of temperance in New York between 1828 and 1833 and measures of economic and political change, accounting for demographic controls. Next, we tested whether counties’ Presbyterian and Congregational clergy were significantly associated with the onset of temperance beyond demographic, political, and economic factors. The measure of revivals was then added to the model to test how revival activity was associated with the onset of temperance beyond counties’ demographics, economic changes, and political and religious institutionalism. Finally, we included our second measure of the Second Great Awakening, home missionary societies, to test how they mediated revival effects on the onset of temperance activity. We fitted the same series of four nested models to analyze the time-specific hazard of New York counties establishing an antislavery society between 1835 and 1838.

To test our hypotheses about the growth in temperance and abolitionism, we fitted multilevel random slope Poisson rate models to analyze growth rates in temperance societies between 1828 and 1834, and we fitted Poisson rate models to analyze growth rates in antislavery societies between 1835 and 1838.Footnote 4 We included fixed effects indicators of state regions to control for unobserved region-level differences in all growth models.Footnote 5 As we did with the survival models, we fitted four nested models to test the associations between churches and growth rates in temperance and antislavery societies as well as the associations between religious revivals and home missionary societies and growth rates in temperance and antislavery societies. We then fitted a fifth model that tested the association between temperance societies and growth in antislavery societies. The association between home missionary societies and growth in temperance societies was found to change substantively across time. Thus, the Poisson rate model fitting growth of temperance societies included an interaction between home missionary societies and a linear term of time.Footnote 6

Results

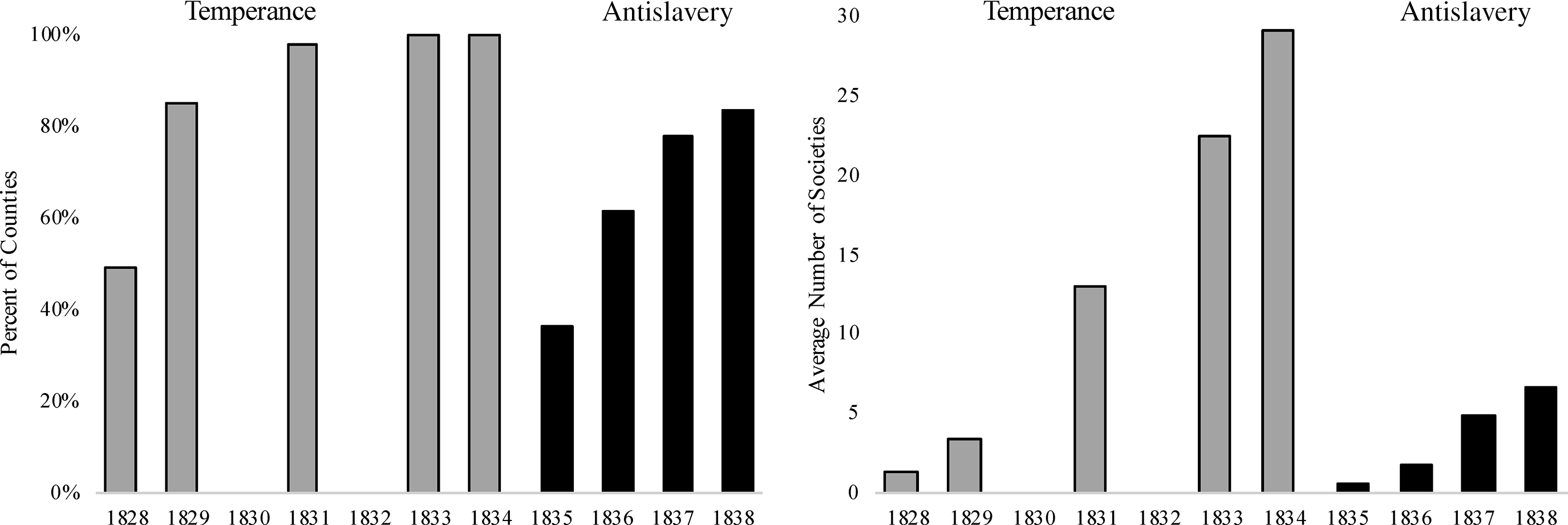

The left panel of figure 2 plots the percent of New York counties having established a temperance society between 1828 and 1834 and the percent having established an antislavery society between 1835 and 1838. We see that by 1833 every county in New York State had established at least one temperance society, with all but one county having established a society by 1831. By contrast, the establishment of early AASS auxiliaries in New York State was more gradual. The prevalence of AASS societies increased considerably between 1835 and 1838 (i.e., 36 percent to 84 percent), but by the study’s endpoint there were several New York counties that had not established an auxiliary society of the AASS. The right panel of figure 2 plots the average number of ATS auxiliaries and average number of AASS auxiliaries across the respective times. Here too we see that the growth of temperance in New York State was more rapid than the growth of abolitionism. The average number of temperance societies per county rose dramatically from about one in 1828 to about 30 in 1834. In contrast, the average number of antislavery societies rose steadily from about .6 in 1835 to nearly seven in 1838.

Figure 2. Percent of New York counties with a temperance society and an antislavery Society (left) and the average counts of temperance and antislavery societies in New York counties (right), 1828–38.

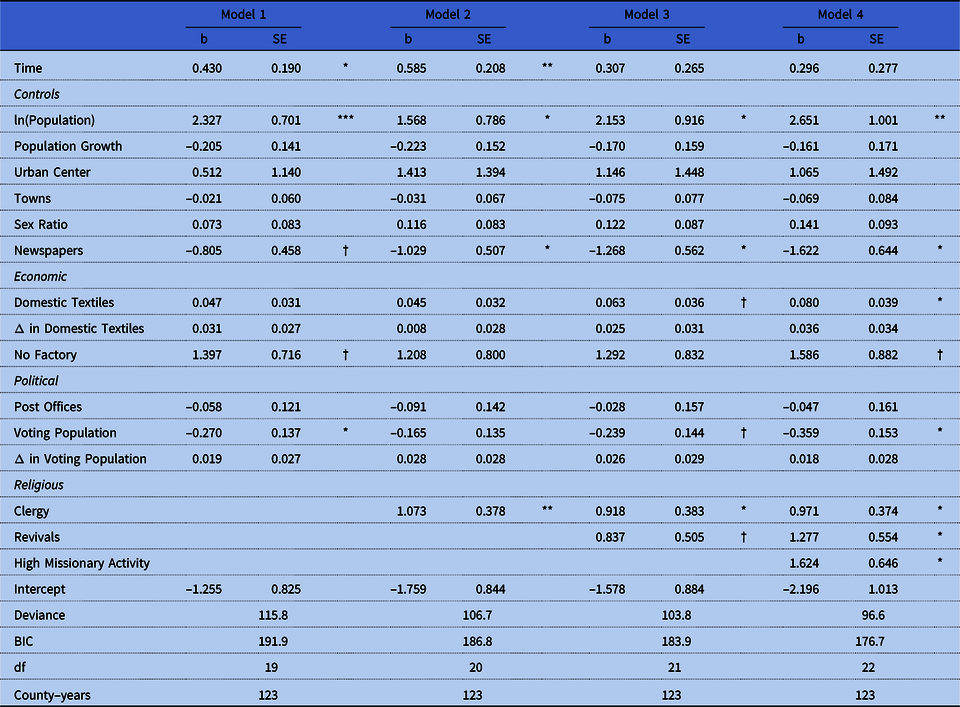

Estimated coefficients associated with clog-log hazards for New York counties establishing a temperance society between 1828 and 1833 are presented in table 1, and estimated clog-log hazards for establishing an antislavery society between 1835 and 1838 are presented in table 2. From Model 1, we see that none of the economic or political measures are estimated to have been significantly associated with establishing a temperance society. Counties without a factory were estimated to have had a higher hazard of establishing an antislavery society, while the size of the eligible voting population is estimated to have been negatively associated antislavery onset. From Model 2, we find that Presbyterian clergy were significantly and positively associated with the onset of both temperance and antislavery societies. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in clergy is estimated to have elevated the risk of temperance onset by 6.7 percent (i.e., exp(.681*ln(1.1))) and to have increased the risk of antislavery onset by 10.8 percent. Model 3 estimates significant and substantively strong positive associations between revival activity and both the risk of establishing a temperance society and the risk of establishing an antislavery society. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in revival activity is estimated to have elevated the risk of establishing a temperance society by 12.9 percent and to have elevated the risk of establishing an antislavery society by 8.3 percent. The results also indicate that revival activity explains part of the associations between Presbyterian clergy and the risks of establishing a temperance and antislavery society (i.e., the 6.7 percent effect on temperance onset estimated in Model 2 is down to 5.1 percent in Model 3, and the 10.8 percent effect on antislavery onset is down to 9.1 percent). The findings from Model 4 also suggest a strong link between home missionary societies and the onset of both temperance and antislavery societies. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in home missionary activity is estimated to have significantly elevated the risk of establishing a temperance society by about 20 percent and to have significantly elevated the risk of establishing an antislavery society by 16.7 percent. Results from Model 4 also indicate that the positive association between Presbyterian clergy and the onset of temperance has been further reduced by accounting for mission activity (i.e., the 6.7 percent effect on temperance onset estimated in Model 2 is reduced to 2.6 percent and no longer statistically significant in Model 4).

Table 1. Clog-log estimates of New York counties establishing a temperance society, 1828–34

Note: All models include region fixed effects.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; † p < .1.

Table 2. Clog-log estimates of New York counties establishing an antislavery society, 1835–38

Note: All models include region fixed effects.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; † p < .1.

Overall, results from the survival analyses provide strong evidence in support of our first and second hypotheses. Regarding hypothesis one, New York counties’ revival and home missionary activities were each found to have significantly elevated counties’ likelihoods of establishing temperance and antislavery societies. Regarding hypothesis two, the estimated positive associations between Presbyterian clergy and the onset of temperance and antislavery societies are both largely explained by revival activity and home missionary societies. The combined influence of revivals and home missionary societies on the onset of temperance and antislavery societies in New York State is illustrated in figure 3, which plots the estimated likelihoods of establishing a temperance society (left) and antislavery society (right) by low and high levels of Second Great Awakening evangelism. Specifically, figure 3 plots the predicted year-specific probabilities for New York counties establishing temperance societies at one standard deviation below average revival and home missionary activity, and at one standard deviation above the average revival and home missionary activity. The probabilities are predicted at mean values for all other covariates and for the observed yearly time values. Likewise, the year-specific probabilities for establishing antislavery societies are predicted at one standard deviation above revival activity and for counties having had “high” missionary activity and at one standard deviation below revival activity.

Figure 3. Estimated likelihoods of New York counties establishing temperance societies, 1828–34, (left) and antislavery societies, 1835–38, (right) by level of evangelizing activity.

Note: Likelihoods are estimated from model 4.

The differences in the probabilities by religious activity are striking. Counties with high evangelism are predicted to have had a .84 probability for establishing a temperance society in 1828 whereas counties with low evangelism are predicted to have had only a .07 probability. And in 1829, the probability for counties with high evangelism was predicted to be 1.0 versus only .53 for counties with low evangelist activities. By 1831, nearly all New York counties established a temperance society and the probabilities reach parity. For antislavery societies, the differences in the probabilities by evangelist activities are striking as well. Among those counties with low evangelism, the year-specific probabilities range from only .05 in 1835 to .12 in 1838. In contrast, the predicted probabilities for counties with high levels of evangelism range from .74 in 1835 to .96 in 1838.

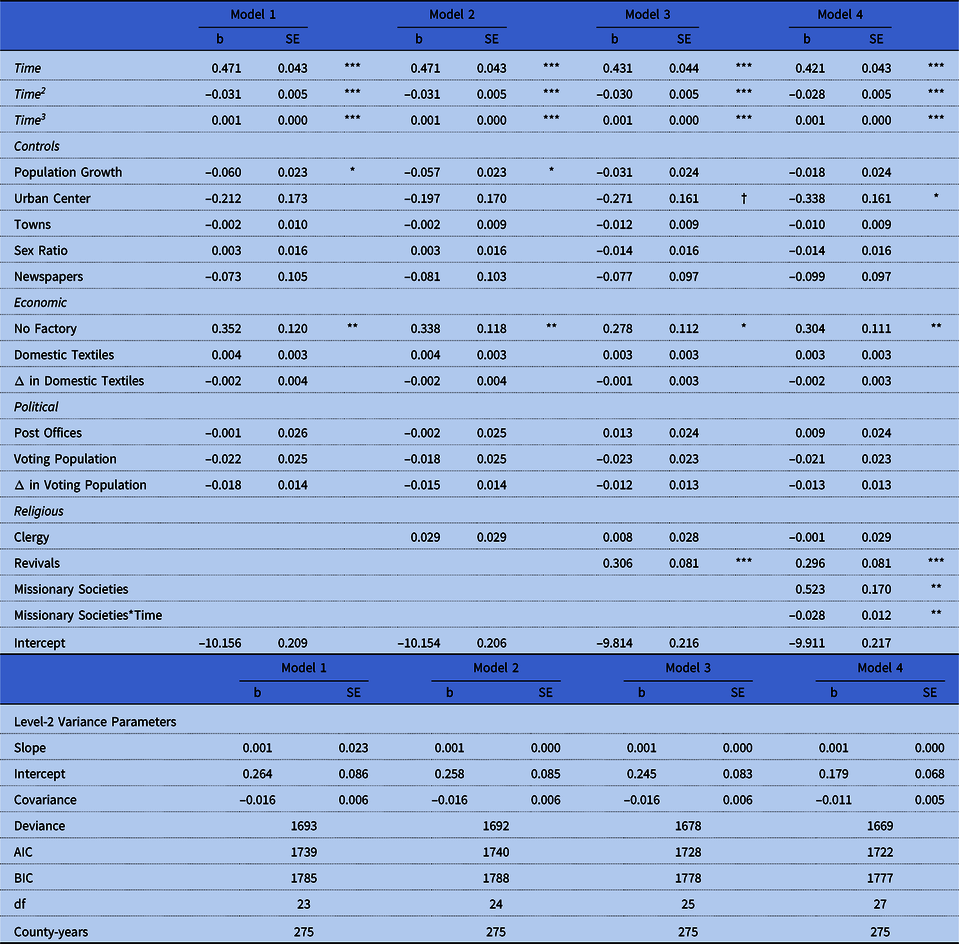

Estimated coefficients for growth rates of New York temperance societies are presented in table 3, and estimated coefficients for growth rates of New York antislavery societies are presented in table 4. Results from Model 1 indicate that growth in New York temperance societies was rapid across time and negatively associated with county population growth. Among the political and economic factors, the presence of a factory is the only indicator significantly associated with temperance growth (i.e., counts of temperance societies were about 40 percent higher in counties without a factory than in counties with a factory). Results from Model 1 in table 4 suggest that growth in New York antislavery societies was also rapid across time and was also negatively associated with population growth. We also find evidence suggesting that growth in antislavery societies was more than two times higher in counties without a factory, and also was significantly associated with change in domestic production of textiles—although the association is quite weak (i.e., an estimated .17 percent increase in antislavery societies for a 10 percent reduction in domestically produced textiles). Further, all political indicators are estimated to have been significantly associated with growth in antislavery societies, yet the findings are inconsistent with theories about political institutionalism and US associationalism (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997). Specifically, post offices and the size of the voting population are each estimated to have been negatively associated with antislavery growth, whereas the expansion of the voting population is estimated to have been positively associated with growth. Model 2 finds no evidence linking Presbyterian clergy with growth in New York temperance societies, but findings indicate that clergy was significantly associated with growth in New York antislavery societies (i.e., 4.2 percent growth per 10 percent increase in clergy). Results in Model 3 indicate that revival activity was significantly and positively associated with growth in both temperance societies and antislavery societies. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in revival activity is estimated to have increased counts of temperance societies by 3.0 percent and to have increased counts of antislavery societies by 3.2 percent. Model 4 provides evidence indicating similar effects for home missionary societies on the growth of both temperance and antislavery societies in New York State. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in missions elevated counts of temperance societies by 5.1 percent in 1828, 3.2 percent in 1831, and 1.0 percent in 1834. Also, counties that had had “high” missionary activity between 1828 and 1834 are estimated to have had 49.8 percent more antislavery societies than counties that did not have “high” missionary activity. Further, the positive association between Presbyterian clergy and growth in antislavery societies estimated in Model 2 is reduced substantially after controlling for revival and home missionary activities in Model 4 (i.e., 2.3 percent growth per 10 percent increase in clergy).

Table 3. Estimates from multilevel Poisson rate models of temperance growth in New York counties, 1828–34

Note: All models include region fixed effects.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; † p < .1.

Table 4. Estimates from Poisson rate models of antislavery growth in New York counties, 1835–38

Note: All models include region fixed effects.

*** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; † p < .1.

Results from these analyses provide strong evidence in support of our first and second hypotheses. Regarding hypothesis one, counties’ revival and home missionary activities were each found to have significantly accelerated growth of both temperance and antislavery societies in New York counties. Regarding hypothesis two, the positive association observed between Presbyterian clergy and growth in antislavery societies is explained almost entirely by revival activity and home missionary societies. Finally, Model 5 provides strong evidence suggesting that New York counties’ temperance activity also significantly influenced subsequent antislavery activity. Specifically, a 10 percent increase in temperance societies was estimated to elevate counts of antislavery societies by 2.2 percent. This finding provides strong evidence in support of our third hypothesis, in that temperance activity in New York counties strongly and positively predicted subsequent antislavery activity.

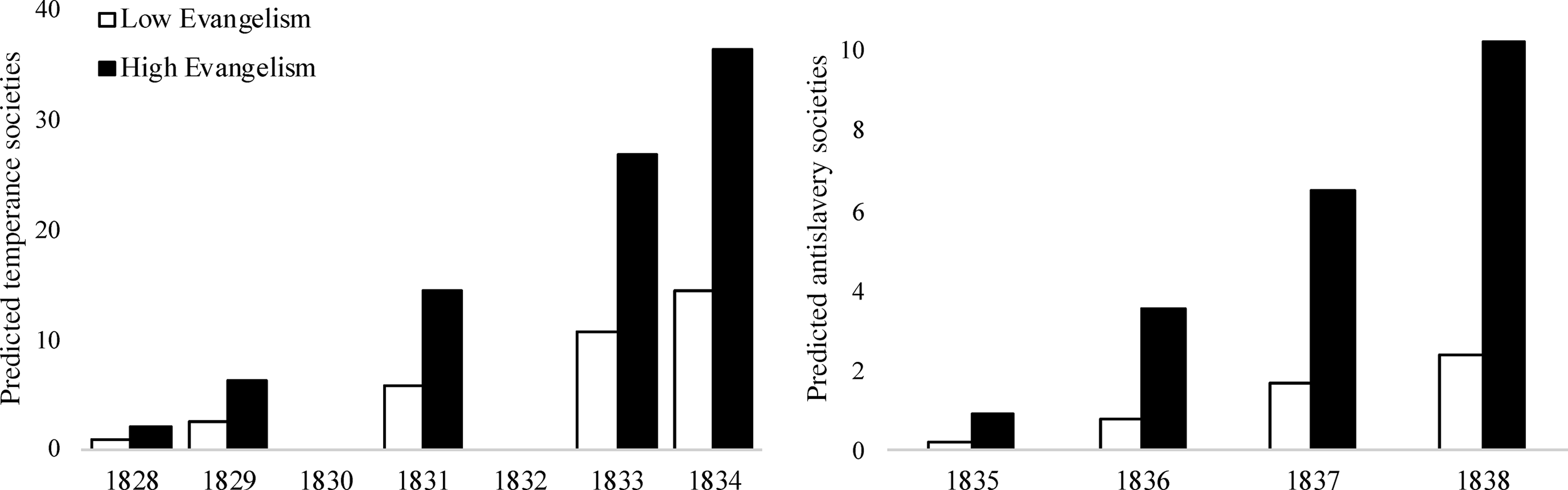

In figure 4 we plot predicted counts of temperance societies by level of evangelism (left) as well as predicted counts of antislavery societies by level of evangelism (right). The left panel of figure 4 shows the predicted year-specific counts of temperance societies for New York counties one standard deviation below average revival and home missionary activity, and for New York counties one standard deviation above the average revival and home missionary activity. The counts are predicted at mean values for all other covariates. Across all years, the predicted number of temperance societies in counties with high evangelizing activity are estimated to be more than 2.5 times greater than the number of temperance societies predicted in counties with low evangelizing activity. The right panel of figure 4 shows the predicted year-specific counts of antislavery societies for New York counties one standard deviation below average levels of revival and temperance activity, and for New York counties one standard deviation above the average levels and with “high” missionary activity. The counts are predicted at mean values for all other covariates. Across all years, the predicted number of antislavery societies in counties with high evangelism are estimated to be about four times greater than the predicted number of antislavery societies in counties with low evangelizing activity.

Figure 4. Estimated average count of temperance societies (left) and antislavery societies (right) in New York counties, 1828–38, by level of evangelizing activity.

Note: Estimates are predicted temperance counts from model 4 and predicted antislavery counts from model 5.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the associations between evangelical forces of the Second Great Awakening and the emergence and spread of the US temperance and antislavery movements in New York State. We first examined how religious activities in New York State were related to counties’ likelihoods of establishing temperance and antislavery societies during the early stages of the movements. We then examined how religious activities in New York State were related to the overall growth of temperance and antislavery societies during this time. Our examinations were guided by three hypotheses: (1) that revival and home missionary activities were each strongly and positively associated with both the onset and growth of temperance and abolitionism, (2) that churches and clergy were not associated with temperance and abolitionism except through their associations with revivalism and home missionary activities, and (3) that temperance activity in counties was strongly and positively associated with subsequent antislavery activity. Results from all analyses provide strong support for all three hypotheses. Importantly, we found strong empirical evidence suggesting that cultural mechanisms of religion (i.e., revivals and home missionary societies), but not institutional mechanisms of religion (i.e., clergy and churches), were associated with the emergence and growth of both temperance and abolitionism in New York State. To conclude, we offer three points of consideration.

First, we constructed a rich, county-level dataset that empirically documents early social movement activity in the United States. This is important in its own right because existing investigations of early US social movements have primarily relied upon national-level data. Analyzing county-level data across several waves of time permits finer investigations into the processes that significantly influenced the establishment and growth of temperance societies and antislavery societies during the initial stages of the movements. Further, we were able to quantify cultural-religious mechanisms associated with the Second Great Awakening—revival activity and home missionary societies—and demonstrated that these forces’ associations with temperance and abolitionism were distinct from the institutional-religious forces of the time such as Presbyterian and Congregationalist churches and their respective clergy.

Second, at the county level, political and economic structural measures fail to fully account for either the onset or the growth of the temperance movement and the antislavery movement in New York State. This finding alone is quite significant. New York State was at the forefront of the nation’s effort to mobilize people to refrain from drinking spirits, and more temperance societies were founded in New York between 1828 and 1834 than any other state in the nation. Moreover, the AASS operated out of New York City in the early stages of the movement. Most existing theories of temperance and antislavery are politically and/or economically structural in nature, explaining these mobilizations as products of party-politics, political institutionalism, and/or market expansion. Our results find weak support (in the case of economic explanations), no support (in the case of market expansion), or opposite and conflicting support (in the case of political institutionalism) for such explanations. Although changes in economic and political structures may have generated the necessary conditions for sustaining national-level movements in nineteenth-century America (e.g., the postal system and proliferation of print media aided interstate communications) (King and Haveman Reference King and Haveman2008; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1997, Reference Skocpol2013), these structural changes are insufficient at explaining county differences in the onset and growth of these movements within New York State.

Third, the associations between temperance and abolitionism and our measures of Second Great Awakening activities support the theory that the temperance movement in New York State and the subsequent antislavery movement were by and large cultural-religious phenomena. In support of our first hypothesis, we found strong evidence suggesting that the onset and growth of both temperance societies and antislavery societies in New York State between 1828 and 1838 were associated with religious revivals and home missionary societies. First, revivals were found to have been significantly and substantively associated with both the onset and growth of New York State temperance societies. Revivals were also significantly and substantively associated with the onset and growth of New York State antislavery societies. Second, home missionary societies were also found to have been significantly and substantively associated with both the establishment and growth of temperance societies and antislavery societies in New York. Moreover, when both of these cultural-religious factors were accounted for, the apparent positive associations between Presbyterian clergy and both temperance and abolitionism were substantively reduced and statistically nonsignificant. These important findings strongly support our second hypothesis. Finally, in support of our third hypothesis, counties’ temperance societies between 1828 and 1834 were found to be strong predictors of counties’ growth in antislavery societies between 1834 and 1838.

Together, our findings indicate a strong relationship between the Second Great Awakening and the American temperance and abolitionism movements in New York State. Temperance, the first national social movement in US history, was deeply religious in its motivation and organizing source. Yet sources, no matter how powerful, do not determine the full course of a social movement, particularly one as long and as powerful temperance was in America. Not long after this religious beginning, some temperance advocates lost patience with the slow pace of moral suasion and moved forcefully into legislative battles for prohibition, party politics, and class and ethnic conflicts. From the mid-nineteenth century, with the first state prohibition law in Maine in 1851 to national Prohibition in 1919, economic, political, and status interests—in a phrase, less spiritual forces—redirected the course of American temperance. The antislavery movement fractured in the late-1830s, in no small part over disagreements about the efficacy of a strategy that avoided institutional politics. Some abolitionists maintained their distance from politics, largely on religious grounds, and stayed the course of confessional protests and moral suasion. Still others ran headlong into party politics with the formation of the Liberty Party and later alliances with the Free Soil Party. While the movement fractured, it nonetheless escalated and helped drive the young republic on an irreconcilable path to civil war.

In their beginnings, however, American temperance and abolitionism were very much religious awakenings. The early phase of these movements should not for this reason be understood as apolitical or “merely cultural” (Butler Reference Butler1997). From their onset, these movements forcefully challenged and changed American attitudes, behavior, and institutions. While they eschewed institutional and party politics at their start, and according to our findings received little or no support from them, they made claims on the private and public lives of Americans, which were met with immediate and heated resistance.

Temperance and abolitionism first won mass appeal as what today we would term life politics or “new social movements” (Buechler Reference Buechler1995; Calhoun Reference Calhoun1993; Melucci Reference Melucci1980). The calls from temperance and abolitionism demanded that Americans confess for their drinking and sins and pledge to reform themselves and their institutions. These movements advocated a contentious fusing of self-transformation and social change. For sociologists of social movements, it is important to recognize that activism of this kind has been around in the United States for centuries and that its origins were largely shaped by religious forces. For sociologists of religion, it is important to realize how adeptly religious actors fought for civil influence through a form of life politics immediately after the institutional separation of church and state in the United States.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2022.6