The 1950s and 1960s saw a transformation in the international order as a world formerly dominated by European colonial empires gave way to one populated by numerous new nation-states and supranational organizations. Aid became a key feature of relations between these new states, ex-colonial powers, and the new organizations. Critics, notably Kwame Nkrumah, first president of Ghana, were quick to allege that it constituted a form of neocolonialism: a “revolving credit, paid by the neo-colonial master, passing through the neo-colonial State and returning to the neo-colonial master in the form of increased profits.” In Nkrumah's view, multilateral aid was no exception: it was a site of rivalry between states pursuing their own imperial ambitions.Footnote 1 Nkrumah reserved some of his sternest criticisms for the new European Economic Community (EEC), a “European scheme designed to attach African countries to European imperialism.”Footnote 2 Through a discussion of Britain and the EEC over a ten-year period from the moment of Britain's accession to the EEC in 1973 through to 1983, we indeed show that successive British governments viewed this post-colonial multilateral aid system as commercial opportunity. We analyze their endeavors to change EEC procedures to make sure EEC aid paid by benefitting British firms.

The EEC from the outset became a significant source of development aid. As early as 1957, the EEC entered into association with overseas countries and territories, mostly French and Belgian colonies in sub-Saharan Africa. The association agreement, which subsequently came to complement the EEC member states’ bilateral aid, combined reciprocal trade preferences with financial aid. A European Development Fund for Overseas Territories (later called European Development Fund [EDF]) was established, which offered aid mainly in the form of grants. It was funded by contributions from the member states, with France and Germany initially the main contributors. The European Commission, the supranational body of the EEC, was entrusted with its management through a specific service called Directorate General 8 (DG8). In 1963, after most associated countries had become independent, the EEC updated its relationship with former colonies in the Yaoundé Convention, which was signed for five years with the Associated African and Malagasy States and which established EDF II. The fund was thereafter renegotiated every five years (hence reference to EDF I, II, III, etc.) along with the renewal of the convention. EDF grants could be spent by the recipient over an undetermined length of time.Footnote 3 In 1969, the Yaoundé II Convention launched EDF III. When the UK joined the EEC, it agreed to contribute to the next iteration of EDF (i.e., EDF IV). The latter was established when, after lengthy discussions, independent Commonwealth (CW) states in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific (ACP) eventually opted to become associates under what was renamed in 1975 the Lomé Convention.

In this article we explore how Britain tried to instrumentalize EEC development aid for its own benefit. The argument itself is not new. Much ink has been spilled debating whether multilateral aid really served the ethical aims of stimulating economic growth in developing countries or the national interests of donor countries, not least by yielding opportunities for their industries and firms, or both.Footnote 4 Two critics of the World Bank, Cheryl Payer and Catherine Caufield, each suggest that a significant proportion of the Bank's lending returned directly to Western (American or European) transnational corporations’ pockets, while development economists have shown that multilateral aid brought dividends for donor countries, including Britain.Footnote 5 The political economist Sarah Bracking argues that the available evidence shows that donor countries “tend to place their multinational lending in agencies where they expect their companies to receive the most derivative contracts.”Footnote 6 However, while British and French interests might be among the beneficiaries of these contracts, this new era of global aid governance could potentially disturb the power relations and established economic ties between ex-colonial powers and their former colonies.Footnote 7 Certainly, it contributed to the opening of formerly protected colonial markets to new competitors: US or German firms, for instance, which might benefit from investments and projects run by multilateral aid agencies.

Yet, regardless of this evidence and these debates, few archivally based studies have been undertaken to assess the strategies employed either by corporations or member states of international organizations to make multilateral aid pay, a question highly relevant both to the scholarship on global aid governance and to business history. With a few notable exceptions, the “business of development” in the post-colonial age has been neglected.Footnote 8 In our recent co-edited book, we sought to build on the few existing works, opening up historical discussion of the ways in which the advent of post-colonial aid regimes, bilateral as well as multilateral, potentially offered businesses new opportunities to advance their interests.Footnote 9 This article offers a further exploration of this theme specifically as it relates to multilateral aid. It is based on a reading of the records of the EEC, business associations, and the French and British states. The last are especially important not only for exploring the means the UK adopted to advance its commercial ambitions when confronted by competition from other member states but also for capturing the range and pattern of business-state lobbying in ways impossible through research in the archives of individual firms or business associations. Throughout, our focus is primarily on the British government and its interaction with, respectively, British business and the European Commission. The politics and management of aid in recipient countries lie beyond our scope. Adopting a ten-year time frame enables us to explore both how, on entry to Europe, the British government sought to ensure that participation in European aid would work to Britain's benefit and the strategies it pursued once it became clear that participation had not produced the anticipated dividends for British firms.

This argument yields several points of wider interest in relation to business history, supranational governance, and British overseas aid.

First, our argument shines a light on the interaction between the EEC/EU, member states, and business. Some scholars working on the European integration process postulate that the delegation of sovereignty and power from the member states to the EU reduced private actors’ control, notably over trade policies, and that “politicians consciously designed the EU's institutional framework to minimize the influence of societal interests.”Footnote 10 Others, by contrast, insist on the capacity of business to form associations, sectoral and/or transnational associations, and to adapt their lobbying practices to the EEC/EU institutions efficiently.Footnote 11 As far as EEC development aid is concerned, there were three actors that might be the object of lobbying by firms seeking to change the EDF rules or to get more contracts than their competitors: ACP states, which devised and proposed the projects to be funded, as well as implemented them; the European Commission, which appraised these projects and oversaw their implementation; and the member states, who were represented on an EDF committee that voted on which projects should be approved.Footnote 12 In practice, however, it was difficult for individual firms to lobby the Commission because, under the Treaty of Rome, it had to ensure that calls for tenders by ACP authorities were open on equal terms to firms in all member states and ACP countries. Lobbying ACP states directly to get them to propose projects likely to advantage one specific firm was easier, especially as the ACP states needed help to devise their projects. This kind of lobbying was most likely to favor firms of former colonial powers that might have established ties to local elites. Lobbying member states for each to defend specific projects within the EDF Committee or to change the EDF rules was also possible but depended on the balance of power and coalition among them, as the voting system was by qualified majority.

In the case of Britain, however, it seems that none of these scenarios captures what happened, even though some firms did lobby the UK government. Rather, it was primarily the British state that lobbied the private sector, encouraging it to take advantage of the EDF. Such an observation bears out Laurence Badel's warning about studying private actors and their actions at the global level without taking into account their links with their national governments.Footnote 13 Our findings cannot provide an answer as to where the balance of power lies between private actors and political ones, or between the British government and EEC institutions.Footnote 14 However, they certainly validate former studies about the tendency of national EEC governments to defend their firms when confronted with EEC regulations enforcing competition, and they contribute to business history in showing that power relations between international organizations, states, and firms are more complex than meets the eye.Footnote 15

Second, in advancing this argument about the British state's determination to ensure that British business benefitted from EEC aid, we offer a fresh perspective on the history of British overseas aid. Greater commercialization in British aid is generally traced to the late 1970s, and more particularly the 1980s under the Conservative governments of Margaret Thatcher (1979–1992).Footnote 16 This article, however, identifies a “commercial turn” in British policy in the early 1970s.Footnote 17 Our argument here is that this was not principally a consequence of business lobbying but a strategy adopted by the Conservative government of Edward Heath (1970–1974) to ensure that aid aligned with wider economic policy. In addition, our discussion of Thatcher's first government adds to the existing literature on the commercialization of aid in the 1980s, highlighting how different dynamics applied in relation to EEC aid than to other bilateral or multilateral aid. In identifying the self-interested objectives that shaped British policy, our account of Britain and the EDF also differs from that advanced by Ireton in his history of British overseas development, in which he describes Britain's efforts to introduce changes to EDF procedures as designed to improve the practice of European aid and to ensure that it reached those most in need.Footnote 18

Third, this article means to highlight a neglected aspect of the Lomé Convention. The positions of the member states during the negotiations of this convention have been well documented, as has the capacity of the African states (whether the former associated states or the Commonwealth newcomers) to unite around a common position.Footnote 19 Scholars of international relations have interpreted Lomé I in terms of dynamic interdependence, a kind of “collective clientelism” between the EEC and developing countries.Footnote 20 Some believe that the ACP states, acting as a united group, were able to exploit the ties that linked them to a more powerful group of states and impose a more or less equal relationship. This enabled them to mitigate those features of the original association agreements that had informed Nkrumah's characterization of the EEC as neo-imperial.Footnote 21 Others, however, suggest that Lomé I was similar to its predecessors. They analyze it as a new instrument of economic exploitation and control, or as a way for former colonial powers like France and Britain to maintain their zones of influence in Africa.Footnote 22 Our article corresponds to the latter interpretation in so far as we argue Britain sought to adapt EDF procedures to serve its own interests.

Our arguments here also bear on wider discussions about supra-nationality and international organizations. EU specialists like Anand Menon argue that the issue at stake in the delegation of power from the member states to the EEC/EU institutions is not so much some abstract consideration concerning the transfer of sovereignty as it is the concern for each member state to secure greater distributional benefits for its own constituency through its control of EEC institutions.Footnote 23 Scholars working on EEC policies relating to competition, or other international institutions like the League of Nations, and international cooperation agreements in specific fields like multi governmental organizations, emphasize the tendency for member states to defend their own national interests and/or firms at the expense of supranational regulation and global governance.Footnote 24 Our conclusions confirm this.

In what follows, we first show how Britain's entry to the EEC coincided with a commercial turn in British aid policy and highlight the degree to which the UK regarded participation in European aid as a commercial opportunity. The second section demonstrates how—in line with these ambitions to ensure the EDF served British interests—the UK sought during the negotiations preceding the Lomé Convention to redirect EEC aid geographically toward places where British firms had the most to gain and to revise EDF procedures. In a third section, we show that, in the first five years of funding under Lomé I, European aid proved less profitable for Britain than the British government had anticipated. In the fourth and fifth parts, we analyze the strategies the government then pursued to try and change this. We conclude by briefly noting that (within distinct limits) these strategies paid off, because the returns for British business improved somewhat thereafter.

Commercializing UK Overseas Development Policy in the Early 1970s

It is well known that Edward Heath, who became British prime minister following the Conservative Party's success in the British general election in June 1970, was firmly committed to Britain's entry to the EEC. Rather less well-known is his government's approach to overseas aid.

Heath's accession to office coincided with the inauguration in 1970 of the UN Second Development Decade, forcing the issue of overseas aid up the new government's agenda. UN member states were asked to ensure that by 1980 their official development assistance reached 0.7 percent of their gross national product (GNP), and by 1975, 1 percent of all financial flows (including private investment) to developing countries. In October 1970, Heath pledged Britain's “best endeavours” to reach the 1 percent target.Footnote 25 Making this commitment was seen as vital to Britain's international standing and prestige.Footnote 26 But, in other respects, it did not correspond to either the priorities or the interests of a government confronted by rising unemployment and ongoing economic difficulties.

Reconciling Heath's domestic priorities and these commitments pointed to a more hard-headed aid policy. Hitherto, British aid had been less commercialized than that of some other donor countries, reflecting the aid philosophy of the Labour government as well as of civil servants in the new Ministry of Overseas Development (ODM), which Labour had created after its election to office in 1964.Footnote 27 By the late 1960s, financial difficulties arising especially from sterling devaluation in 1967 had begun to prompt a reassessment of the UK's approach; by 1970, about half of all British Commonwealth bilateral aid was tied.Footnote 28 Now Heath's government was determined to make overseas development aid align yet more closely with British economic needs.

One of Heath's first moves was to demote the ODM from a separate ministry to a department, the Overseas Development Administration (ODA), in the FCO. In line with the UN 1 percent target, the government also established a working party to examine measures to stimulate the flow of private investment to developing countries.Footnote 29 The working party's report, published in April 1971, led to the creation that year of a Private Investment and Consultancies Department in the ODA, with responsibility for advising on and arranging feasibility studies, pre-investment surveys, and project-management consultancies. The government also pledged to follow other industrialized countries in the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) by introducing an investment insurance scheme, and where possible by concluding bilateral investment protection agreements for the protection of new and existing investments.Footnote 30 From the mid-1970s, the British government duly entered into agreements of this kind, which became important devices for promoting the activities of multinational firms in developing countries.Footnote 31 In 1972, in another move, Heath's government established the British Overseas Trade Board (BOTB) to advise on overseas trade and the promotion of UK exports. Since this fed directly into government policy and included representatives of large companies as well as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) among its members, it became a channel by which private-sector interests secured access to policymaking.Footnote 32

Alongside these measures, other efforts focused on making British official aid work more effectively in support of British business. When an interdepartmental working party on aid policy appointed in December 1971 recommended that more emphasis be placed on both the direction and forms of aid “which provided good prospects for our exports and investments and political interests,” a major review of all British aid programs was commissioned.Footnote 33 This “programme analysis and review” (PAR) was charged with ensuring that there was a “reasonable relationship” between these “interests”and the “sums we are investing.”Footnote 34 The most significant immediate outcome from the PAR was the creation of a new joint FCO/ODA Aid Policy Committee to consider the British aid program in relation to broader concerns of British foreign policy. Although the review did not result in the introduction of any high-profile initiative (perhaps one reason why the Heath commercialization of policy has remained below the scholarly radar), the FCO had suggested in early 1971 that “a new aid philosophy” was already “de facto in operation.”Footnote 35 Now staff within the FCO's Economic Planning department argued that more aid should be used to generate business for industries currently struggling to attract orders.Footnote 36 British exporters concurred, lamenting that other donor aid programs, like the French, through the use of “credit mixte” or Canadian-style double tying, did more to advantage their national interests.Footnote 37

At this pivotal moment in British aid policy, accession to the EEC and participation in the EDF brought the prospect of significant changes to the profile of British overseas development spending, possibly soaking up to 20 percent of Britain's total aid program.Footnote 38 Hitherto, multilateral aid had constituted only around 10 percent of British official aid expenditure.Footnote 39 This was a smaller percentage than for any other member of the OECD's Development Assistance Committee, except Australia and Portugal, reflecting Britain's focus on bilateral aid to former and remaining dependencies as well as its previous exclusion from the EEC.Footnote 40 It was this concentration on bilateral aid that had enabled Britain to tie a growing percentage of aid to the purchase of British supplies (even though, as discussed above, British aid was less commercialized than that of some other countries), and, increasingly, to target it more strategically.

Yet, from the outset, Heath's government regarded participation in European aid as a commercial opportunity. EDF contracts were financially secure and provided in effect a “captive market” for firms.Footnote 41 Moreover, civil servants hoped that participation in the EDF could lead to opportunities for Britain in francophone states.Footnote 42 It is likely no coincidence that at the time of British accession, the London Chamber of Commerce explored opportunities in non-CW associated states, organizing commercial missions to the Ivory Coast and Zaire in 1973 and 1975, respectively.Footnote 43 Equally, while they recognized that Britain might now face competition from firms of other EEC member states in traditional British markets, British civil servants were optimistic that, on balance, EDF aid to EEC CW associates would probably be spent in Britain.Footnote 44

There were good reasons for this optimism. The PAR had recently demonstrated that British business generally benefitted disproportionately from multilateral aid. Civil servants calculated that the total British dispersal of aid in 1971 amounted to £277 million, generating exports estimated at £110 million. But, whereas bilateral aid directly supported 4.5 percent of British exports to developing countries, this figure rose to around 10 percent of all exports to developing countries when multilateral aid was also factored in.Footnote 45 Indeed between 1965 and the first half of 1972, the British contribution to the World Bank was heavily outweighed in value by business produced for the UK through World Bank-donated funds. In total in this period, Britain had received an estimated US$1,200 million in orders from procurement funded by World Bank aid. The work of the International Development Association (IDA), established in 1960 to assist developing countries through the provision of loans on preferential terms, had proven a little less lucrative for Britain; nevertheless, Britain's contribution to the IDA also more than paid for itself. Up to January 1, 1972, Britain had paid US$284 million and received US$371.7 million in procurement. The picture was not all rosy, as the British share of World Bank contracts had declined over the period from 18.7 percent to 11.0 percent, while the American share had risen from 21.4 percent to 22.9 percent.Footnote 46 However, the evidence to date was sufficiently positive that the 1972 PAR observed that the commercial benefits of multilateral aid “outweigh those of tied bilateral aid” (since the returns on the latter could never be greater than the sums Britain had donated).Footnote 47

The positive commercial dividends of multilateral aid partly reflected a favorable British balance of trade with the developing world.Footnote 48 In turn, this related to the established presence of British interests in former colonies. Tellingly, the British share of procurement arising from the World Bank and IDA spending was greatest in South Asia and Commonwealth Africa. Conversely, British civil servants believed that the declining share was accounted for by the increasing proportion of World Bank money going to Southeast Asia or Latin America, as well as to the growing strength of Japanese business in Pakistan.Footnote 49 As studies of British aid in a later period would confirm, strong British connections were crucial to Britain's position as a beneficiary of multilateral aid.Footnote 50 A diaspora of British technical assistance personnel, consultants, and the Crown Agents, established in the colonial era to provide a range of services to the colonies, including procurement, helped reinforce historic connections and were perceived as important for supporting British business.Footnote 51

In sum, British ministers and civil servants considered that Britain stood to gain more from EDF spending than Britain itself would contribute to the EDF, so long as all ACP CW countries gained associate status. Indeed, the EDF “could well provide a balance of payments gain for the UK compared with tied bilateral aid.”Footnote 52 The UK therefore had an interest in securing an increase in the EDF sufficiently large as to accommodate CW states; and, in common with France, in maximizing the flow of aid from Germany and other EEC members to former colonies.Footnote 53

Britain's Entry to the EEC and Participation in the EDF

Realizing the commercial potential of participation in the EDF required careful negotiation to ensure that, as bluntly stated in one Cabinet paper, “the Commonwealth gets as much EDF aid as possible.”Footnote 54 As the FCO concluded in summer 1973, the key question was how to limit the increased financial commitment the EDF entailed for the UK, without jeopardizing the Commonwealth associates’ access to the fund, “and our chances of increased procurement.”Footnote 55 Three years later, the goal remained the same. Following the inclusion of the CW African Caribbean and Pacific countries in the Lomé Convention, British civil servants met to discuss a paper whose title proclaimed their ambitions: “Ways and Means of Getting EDF Aid flowing in the Right Way into the Countries in which we are interested.” The British share of the EDF under Lomé (EDF IV) was fixed initially at £360 million, or around 18.7 percent of the total EDF budget. As the British noted, “We cannot fail to interest ourselves in the expenditure of £360m of British taxpayers’ money.”Footnote 56

To ensure the EDF worked for Britain, the British government hoped, before the Lomé Convention was signed, to broaden its geographical scope to include the Mediterranean and Asia.Footnote 57 The British government justified their call for an expansion on the grounds that the Asian states were those “in greatest need.”Footnote 58 But while there were those within the British aid community who were genuinely concerned with the development needs of CW Asian states, in other quarters anxieties focused closer to home: namely, on the possible repercussions for British trade, especially in India, which, the FCO had recently calculated, bought more British exports than almost any other developing country.Footnote 59

Previous experience showed a correlation between the level of aid to India and Pakistan and Britain's share in their trade. Between 1960 and 1963, the proportion of aid the two countries derived from Britain had fallen by 8 percent, while they were also receiving growing sums of tied aid from America. Concurrently, Britain's share in their imports declined from 19 percent to 15 percent.Footnote 60 In February 1963, the director of the Federation of British Industries (FBI) had lobbied the government to use aid to buttress British trade with India.Footnote 61 More assistance was subsequently directed at India. By 1972, CW Asian countries received approximately 40 percent of all UK bilateral aid. Now faced with the prospect that Britain's accession to the EEC would reverse this trend and force a decline in British aid to India, the FBI's successor organization, the CBI, feared the consequences in relation to nations “near the point of economic take-off,” which constituted promising markets for British industry.Footnote 62

It was quickly apparent, however, that there was little prospect of getting CW Asian states designated as associates in the Lomé Convention. A “declaration of intent” in the accession treaty signaled the EEC's intention to “extend and strengthen” trade relations with CW Asian countries, but this declaration fell far short of a full commitment. This worried the UK parliamentary Select Committee on Overseas Development, which judged that, by agreeing to participate in the EDF before the status of Commonwealth countries had been established, Heath's government had left Britain in a less-than-optimal position. It expressed “reservations” about the commitments the government had (rashly, it implied) made as the price of EEC membership.Footnote 63

The British were more optimistic that they could persuade the EEC to extend the EDF's sphere of operation to include the donation of aid to non-associated states, including not only Asian but also Central and South American countries, other regions they identified as important to their interests. Naturally, therefore, the UK government endorsed India's efforts to secure a commercial agreement with the EEC that would also give India access to some EEC financial and technical cooperation. Even though the EDF sphere of operation was not extended outside the ACP countries, the UK continued thereafter to urge the EEC to accept the principle of giving aid to non-associated states, and to steer an enlarged EEC away from its regional emphasis in development toward a more global approach.Footnote 64

Most fundamentally, the British needed to ensure that ACP CW states were accorded the same status and privileges as existing EEC associates. As they set about realizing this ambition, old rivalries were, as Dimier argues elsewhere, resurrected within the framework of the European aid regime.Footnote 65 Under the provisions of Protocol 22 of the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Ireland Accession Treaty signed in 1972, all UK dependencies in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific were offered associate status, and more precisely three options: participation in Yaoundé II's successor; a less advantageous kind of association through art. 238 of the Treaty of Rome; or mere trade agreements. In the early 1970s, the British embarked on a campaign to persuade CW African states, suspicious of the EEC, of the advantages of the Yaoundé-style association, the only one that gave access to aid as well as preferential trading arrangements. For their part, the French government (in coalition with the old associates) unsuccessfully fought a rearguard action to convince them of the benefits of other possible options. For sure, the enlargement of the Yaoundé Convention to newcomers was not in the French interest; as Jean-Marie Palayret noted, in 1966, 61 percent of the associated states’ imports came from the EEC, of which 34.4 percent were from France.Footnote 66 The French Ministry of Industry and Science was well aware that “traditional ties between France and the first Yaoundé associates” had enabled the French economy to benefit “a lot, at least for ten years, from the EDF funding.” It feared that a flow of EEC aid to anglophone states would favor British firms, “which obviously have strong positions in these countries.” It concluded that the extension of the Yaoundé model of association to Commonwealth countries would offer “few advantages for our industry” and would not compensate for the “effect of the UK competition on the markets of the first Associated African and Malagasy Associates.”Footnote 67

In the end, however, the old francophone associates and the CW newcomers succeeded in establishing a shared understanding that enabled all the ACP CW countries to choose the Yaoundé route.Footnote 68 In 1975, the Lomé Convention consequently extended full associate status to these countries. As the British and the CW associates wished, the Yaoundé Convention system of “reverse preference” endorsed by the French was replaced by the non-reciprocity principle, in conformity with the generalized system of trade preference endorsed by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.Footnote 69 The ACP sugar and banana producers were given preferential access to the EEC's market.Footnote 70 In addition, the British successfully engineered a significant change in the way funding was awarded. Henceforth, aid would be awarded not as previously to individual projects proposed by each associate but on a program basis in which an envelope of funding was granted to each associate according to its level of poverty. This was considered the best way to ensure a fair division of EDF funds between former French and British colonies.Footnote 71

Britain's Share of EDF-Funded Contracts under Lomé I

Despite these arrangements, it was soon evident that Britain's accession to the EEC did not immediately bring Britain commercial benefits on the scale anticipated. Lomé was signed in 1975 but EDF IV did not become fully operational before the end of 1977. While in the first five years of funding under Lomé I (to 1982) Britain's contribution to the fund was initially set at 18.7 percent, Table 1 shows British firms’ share of the value of contracts awarded to European business was only just over 13 percent.Footnote 72 Commercial returns for Britain from the EDF were hence significantly poorer than those from other multilateral agencies, notably the World Bank.Footnote 73 In contrast, France, Belgium, and Italy were winning shares significantly larger than their contributions.

Table 1 National Aggregate Values of EDF IV Contracts (by Contract Type) on 30 September 1982 at the End of the First 5 Years of Funding under Lomé (in ECU).

Source: TAAG Report (1983), Table 3, FCO 98/1649, UKNA; member state contributions to EDF IV from the EEC Court of Auditors’ annual report concerning the financial year 1981, Official Journal of the European Communities, 35, 31 Dec. 1982, C. 344, p. 169. Note: *The European Currency Unit (ECU) was used by the EEC as a unit of account from March 1979 until the introduction of the euro in January 1999. It was based on a basket of member countries’ currencies.

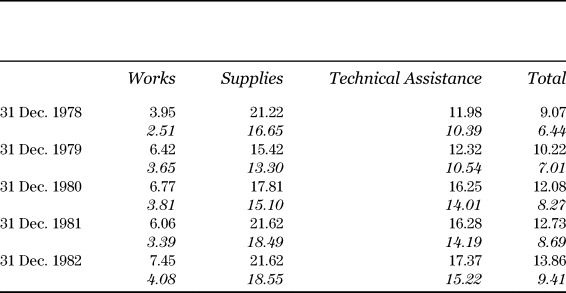

The overall figures disguise some distinct variations in British performance across sectors. Under EDF arrangements, tenders were divided into three categories: work contracts (construction work); supply (of materials); and technical assistance (with the preparation of project proposals or bids). As Table 2 shows, British companies fared particularly badly in securing contracts for construction work, which attracted the lion's share—some 60 percent—of the entire EDF spend on development.Footnote 74 While these figures may underreport British success (since it was possible that some firms listed as “local” were UK firms in disguise, and the figures also did not take into account British companies’ supply of materials to other EEC firms involved in the EDF bids), the overall picture was poor. In 1981 just one British construction firm, Marples Ridgway, succeeded in securing a works contract (to build the Mafeteng-Tsoloane Road in Lesotho).Footnote 75 Moreover, by 1982, within the crucial categories of “works,” there appeared to be no evidence of improvement in Britain's share of contracts: indeed, quite the reverse; as can be seen from Table 2, in 1981 the British share of works contracts awarded to European firms declined from 6.77 percent to 6.06 percent.

Table 2 Cumulative UK % Share of Contracts under EDF IV by Sector in the First 5 Years of Funding under Lomé Convention

Source: Pat Jenkins [?] to John Coles (by this date private secretary to the PM), 16 May 1983, “UK Share of Business,” FCO 98/1647, UKNA. There are minor discrepancies between the figures for the UK in 1982 reported in the two different original sources used for Tables 1 and 2. Figures in Table 2 are the same as those in the Commission's report: Final report from Commission to Council on the results of invitations to tender (E.D.F.), 16 April 1983, Com 83/190, AHCE. Note: Italicized numbers take account of ACP and Third Countries.

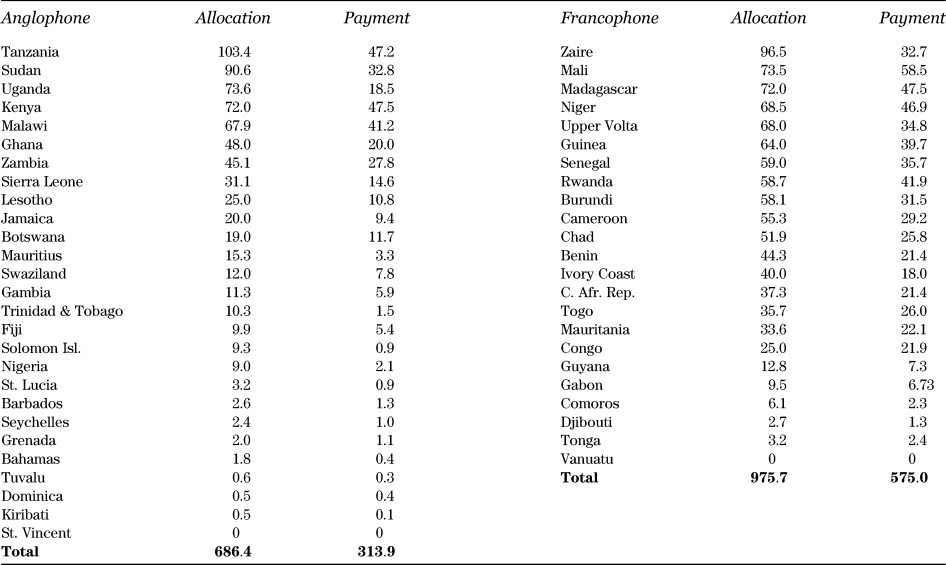

Britain's disappointing share of contracts reflected the geographical distribution of EDF funds. Of all contracts occurring in African states by the end of 1981, forty-six were in francophone countries and only twenty-eight in anglophone.Footnote 76 One of the reasons for this may have been that anglophone associates were allocated and receiving less EDF money than the francophone associates, as illustrated in Table 3. Although the new Lomé arrangements awarded each associate an envelope of funding supposedly according to its level of poverty, the British suspected that the criteria used for establishing poverty (each associate's GNP and population) were interpreted “flexibly” and the allocation of funds was inconsistent.Footnote 77 However, the geographical pattern of spending under EDF IV also reflected the fact that some former British colonies were slow to exploit the opportunities offered by their new status as EEC associates. Each associate could choose when to spend the money in its “envelope,” and most anglophone countries (like Tanzania or Kenya) only launched their first EDF tenders in 1978–1979.Footnote 78 Nigeria, where British business was particularly strongly represented, had insisted during the Lomé Convention that it should be a donor rather than a recipient. This being rejected, Nigeria particularly had been reluctant to propose projects for funding.Footnote 79 At the same time, francophone states might still have been spending funds awarded under EDF I, II, and III.Footnote 80 There were also more large-scale projects in francophone than in anglophone states.Footnote 81 As discussed below, British firms regarded bidding for these European-funded projects in francophone states as challenging.

Table 3 EDF IV: Allocation of Programmable Aid under EDF IV in 1975 and Actual Financial Implementation by 31 December 1981 (Value m. ECU)

Source: EEC Court of Auditors’ annual report concerning the financial year 1981, Official Journal of the European Communities, 35, 31 Dec. 1982, C 344, 170. Note: These figures only include British, French, and Belgian ex-colonies and overseas territories, and exclude aid awarded on a regional basis. Programmable aid refers to aid that was given for a specific purpose.

Making European Aid Work for Britain: The Thatcher Government's Efforts to Improve the Share of Contracts Won by British Firms

Britain's poor performance worried Thatcher's government, elected to office in 1979. Under Harold Wilson (1974–1976) and then James Callaghan (1976–1979), Labour had placed greater weight on using aid to alleviate poverty, even though it was Callaghan's government that in 1977 launched the Aid and Trade Provision (ATP) Scheme, an overtly commercial measure that introduced aid-related subsidies for British exports. Wilson's government had reversed the Heath decision to locate responsibility for development policy within the FCO, restoring the ODA to full independent ministry status. Now Thatcher again placed development within the FCO. Her government also deployed the ATP more aggressively, announcing in February 1980 that ATP, originally intended to be no more than 5 percent of bilateral aid, would become an integral part of a commercial aid policy.Footnote 82 A 1980 interdepartmental Aid Policy Review declared the new government's aim to give greater weight to political, industrial, and commercial considerations in allocating aid. In contrast to civil servants a decade before, the authors of the 1980 review were more skeptical about the commercial benefits of multilateral aid; while “in theory” multilateral aid might offer greater commercial opportunities, they suggested bilateral aid was more flexible and better geared for the pursuit of political objectives.Footnote 83 But Britain had little choice but to maintain its contribution to EEC aid, and discussion now ensued among British civil servants as to the reasons behind Britain's low share of EDF contracts and how to improve it. In 1980 a working party of the BOTB Tropical Africa Advisory Group (TAAG) was established to investigate; two years later it was reactivated to inquire into the ongoing failure of British firms to secure more public-works contracts.Footnote 84 The CBI's deputy director, senior figures from the Midland and National Westminster Banks, and Marples Ridgway and Wimpey Asphalt Ltd. (two companies among the handful of British firms that had been successful in securing contracts within the works sector) were drafted in to participate.Footnote 85

Some British business associations were also concerned. In late 1981, for example, the London Chamber of Commerce expressed its frustration that France was “recovering twice their [sic] contribution from the European Development Fund whilst Britain were [sic] only getting half of their contribution back.” It organized a conference on Lomé to publicize European aid. Perhaps to encourage more anglophone associates to utilize their envelopes of funding, the chamber secured EEC money to help pay for ACP CW delegates to attend.Footnote 86

While it was clear that the disappointing British performance was related in part to the geographical distribution of EDF funding, some of the other explanations offered by British civil servants and the UK private sector resemble those advanced by the German government and companies in the 1960s to explain their own failures; namely, that EDF procedures were shaped by French practice and difficult to negotiate for other European firms. Originally, documentation had been drafted by each associated state, but as many of them were in practice devised by French technical assistants and according to French procedures, and in French, the competition tended to be biased in favor of French firms. These complaints led in 1968 to the Commission establishing a common framework for contracts and technical specifications to be used by all associated states.Footnote 87 British accession necessitated further refinement of this framework to accommodate British and Commonwealth procedures and practice.Footnote 88 A particularly fundamental problem had arisen in the case of one British professional sector: quantity surveying, since on the continent there was no close parallel to the profession. In the late 1970s, the British Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors successfully urged the British government to ensure that EDF procedures incorporate reference to the profession.Footnote 89

Despite such modifications and the setting up of a new common framework for contract laws and technical specifications, unfamiliar procedures still proved an issue for some British firms, as one discovered when it tendered for a project in Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso). Its quotation for an order of around £4 million was some 28 percent lower than that of the other twelve companies that also submitted bids but was rejected on the grounds that it failed to meet precise tender specifications (even when the firm speedily remedied this deficiency).Footnote 90

Unsurprisingly, the British suspected that in practice their interests were still disadvantaged by EDF procedures. For example, both British firms and civil servants complained that project intelligence was not available to them early enough to permit adequate time for bidding, with delays experienced in receiving notice of projects from the Commission.Footnote 91 British representatives in Brussels were left too often trying to “prise advance information” out of officials in DG8, the commission service responsible for overseeing the implementation of projects by the ACP authorities, once financial agreements were signed between the EEC and the ACP states.Footnote 92 In fact, notices of EDF tenders were published regularly in the EEC official journal (which was translated into the several languages of the EEC). From 1976, reports from the Commission to the Council on the results of invitations to EDF tender were also included in this journal. John Coles, a senior British diplomat in Brussels acknowledged as much: “I do not think the explanation can lie in an inadequate flow of information or advice from Brussels . . . since the information has been abundantly publicized.”Footnote 93 Nevertheless, Coles did not doubt that “the whole system” had “a definite bias towards French systems and traditions.” Moreover, he suspected another reason for greater French success: the “deliberate though discreet favoring of French, Belgian firms, etc by their well-placed nationals in DG VIII.”Footnote 94

Coles's charge spoke to wider British perceptions that the French were all too willing to use every means available to manipulate the system to favor their own national interests. Charles Powell, the British counselor to the UK Permanent Representation to the European Commission (UKRep) in Brussels, and later private secretary to PM Thatcher, lamenting the poor British share of contracts, feared Britain could “hardly emulate the French in so tying up the administration of their former territories—a Frenchman behind the potted palms in every Minister's office—that contracts drop into their laps like ripe coconuts.” “Nor,” he said, should Britain “follow the Italian example of bribing key officials in ACP countries (for which the evidence is circumstantial but conclusive).”Footnote 95

While British civil servants kept criticizing the European Commission for being too “French minded,” this was not necessarily the case. French colonial officials had certainly dominated DG8 during the first fifteen years of its existence and the EDF had indeed originally been devised following French colonial procedures.Footnote 96 However, as noticed by scholars working on international bureaucracies, international civil servants tend to shift their loyalty from national to supranational bodies.Footnote 97 Indeed, in order to enhance their own legitimacy and authority French officials in DG8 may have had an interest in playing the role that the Commission expected them to play: of arbiter between member state's interests and guardian of the treaty, in the case of the EDF by ensuring a fair competition for tenders. This is evident in two innovations introduced despite French opposition in the 1960s by Jacques Ferrandi, the director of the EDF within DG8, himself a former French colonial official. The first was the introduction of contrôleurs-délégués (delegate inspectors) of the EDF (renamed delegates of the Commission after 1975) whose main role was to supervise the design and implementation of projects by the associated states (including the calls for tenders and technical assistance). The second was the creation of a shortlist of autonomous consultancy firms along with a quota system that aimed to maintain a balance between member states in rough proportion to their contribution to the EDF. This was supposed to counteract the capacity of some firms (most likely French) to lobby and suggest projects to the associated states through technical assistance, thereby creating for themselves a preferential position in the subsequent competition for supply and work contracts.Footnote 98

Moreover, the British themselves put pressure on the Commission to change rules that had been devised precisely to guarantee fair competition between the firms of the member and ACP states. This is clearly evident in relation to consultancy, which emerges as the British sector most active in lobbying over the EDF.Footnote 99 Initially, British consultants secured only a small share of technical assistance contracts, despite the institution of the national quota system noted above. In response the Commission began shortlisting only British firms in relation to some contracts in order to achieve the British quota. As the data in Tables 1 and 2 illustrates, this had the desired effect, and may have played a part in opening the service sector in ACP countries to British consultants.Footnote 100 However, at this juncture, the British Consultants Bureau (BCB), formed to support engineering and related consultancy exports, concluded that quotas in practice now limited their capacity to secure a still greater share. It began urging the British government to press for the abolition of the national quota system altogether, and accused British representatives of not pursuing the issue with sufficient energy in Brussels, a charge robustly rejected by Powell.Footnote 101 The British government subsequently got the Commission to agree that around 20 percent of consultancy business should be removed from the quota system and be open to competitive tendering.Footnote 102 Thereafter it continued to press for the untying of all contracts by the abolition of the entire quota system, pushed by ongoing lobbying from the BCB and a few individual firms, such as the civil engineering company Wallace Evans and Partners.Footnote 103 The British argued that discrimination on the grounds of contractor nationality was contrary to the terms of the Lomé Convention since no other aid under Lomé was tied: a somewhat ironic turn of events given that the quota system was established by the Commission to ensure fair competition.Footnote 104

Persuading British Firms to Tender for European Aid-Funded Projects

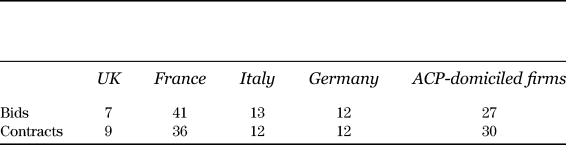

Yet, while UK government officials acknowledged that some British firms had experienced difficulties tendering for EDF contracts, they nevertheless identified a second reason for the disappointing British share of EDF-funded business: the failure of British firms to exploit the opportunities presented by European aid.Footnote 105 This perception was bolstered by analysis that showed that when British firms did tender for contracts, their success rate was better than that of any other member state, as the data for 1981 in Table 4 illustrates.

Table 4 Percentage of Bids Submitted by Firms and Percentage of Contracts won by Country in 1981

Source: Calculated from table in C. D. Powell to R.F. Coker, 18 March 1982, FCO 98/1385, UKNA, using supplementary information supplied by A. Auclert (EEC), briefing paper prepared for D. Hurd by B. L. Crowe on British share EDF contracts, FCO 98/1385, UKNA. Note: Figures rounded up or down to nearest whole number.

While one possible interpretation of these figures is that British firms were more selective than their European counterparts in determining which tenders to bid for, civil servants saw them as evidence that an increase in British bids would likely result in more contracts. They concluded that the “nub of the problem” was how to get British firms to tender for contracts arising from EDF projects.Footnote 106 Indeed, for all that the British government was subject to some lobbying in relation to European aid, notably by the consultancy sector, during the early 1980s it was the British state that drove efforts to make the EDF aid benefit British trade and industry.

One manifestation of this was that across Whitehall different UK government departments introduced a range of initiatives to publicize the EDF, including through a program of seminars and visits to individual firms. The BOTB published a Business Guide to the European Development Fund which provided advice on tendering for EDF contracts.Footnote 107 From 1980, the FCO and Department of Trade corresponded with British diplomatic posts in ACP countries, urging them to identify EDF-funded projects that might be of interest to British business.Footnote 108

However, the problem was not just that British firms were unaware of the opportunities presented by the EDF. Rather, although there were important exceptions, it seemed these opportunities did not appeal to them. In Brussels, Powell judged British firms “unadventurous.”Footnote 109 Tellingly, an expensive advert in the Financial Times for the London Chamber of Commerce's Lomé Conference had apparently generated only seven British bookings.Footnote 110

British firms were especially reluctant to bid for contracts in francophone African countries that had attracted the lion's share of funding under EDF IV. The second TAAG working party reported that British firms struggled to recruit onsite supervisory staff with the requisite language skills, a particular problem since tender documentation was generally prepared by the local governments in French. Such difficulties were particularly acute in the case of countries in the Sahelian and Central African regions, which had received nearly half of all contracts awarded to francophone African states; in these countries there were no permanent UK diplomatic posts or banks, and British firms had little prior presence. In general, the working party judged that the “French connection has been viewed as an awesome monolith, almost unassailable,” and the costs of setting up in francophone states too high to be worthwhile.Footnote 111 Conversely, although few French or Belgian companies won contracts in anglophone states, others, especially German and Italian, did, and British firms perceived anglophone associates as more accessible to the firms of other member states than francophone associates were to British.Footnote 112 Ex-British colonies were, they thought, more “heterogenous” than French, which remained more closely integrated into the French currency system.Footnote 113 Anglophone states also had more established local and foreign competition, perhaps because British colonies had attained independence long before the Lomé Convention was signed, and non-British firms consequently had time to set up in the anglophone countries and get acquainted with their way of working.Footnote 114

Within the Department of Trade, it was suggested that the costs faced by British firms in tendering for contracts in francophone states could be mitigated by working with local firms already established in these markets.Footnote 115 However, British firms objected that they struggled to identify local partners in francophone states; not only were there no reliable local trade directories, but local firms were often small, and already closely allied to French or Belgian companies.Footnote 116

The TAAG inquiry indeed found that much of the French success in West Africa could be traced to a small group of interconnected business interests.Footnote 117 One French company, S.A. de Travaux d'Outre Mer (SATOM), had won ten contracts, more than any other firm.Footnote 118 In 1981, for example, four of the eight work contracts won by French companies were effectively granted to SATOM.Footnote 119 Most of these contracts were secured as part of consortia built with other companies, either French, local or (in four cases) the German firm Wix and Liesenhoff that had also enjoyed considerable success in West Africa. SATOM was affiliated to three other French businesses that had also won contracts: Sainrapt & Brice, Bourdin & Chaussée, and the Société Générale d'Entrerprises. In turn, these four companies were all subsidiaries of one conglomerate, the Compagnie Générale d'Electricité, which not only had many subsidiaries throughout West Africa but also had consultancy firms within its group. Two other French companies that had done well, the Société Française d'Entreprises de Dragages et de Travaux Publics and the Société Nationale de Travaux Publics, which had won six and two contracts, respectively, were similarly both owned by a single parent company: the Compagnie Française d'Enterprises. The TAAG working party concluded that “in very considerable measure,” the large Franco-Belgian share of the total value of EDF works contracts was due to these two parent companies, and their organization and local presence.Footnote 120

Ironically, the formation of consortia had in fact been encouraged by the European Commission in its attempts to resolve what became known as the “discrimination issue”; that is, the disproportionate share of contracts that the French firms enjoyed in the 1960s in comparison to German firms.Footnote 121 Yet, although there was certainly evidence that the creation of consortia helped a small number of important French firms secure contracts, British analysis was not entirely accurate. In 1981, more than thirty other French firms had received EDF contracts, including twenty-eight in the supply sector.Footnote 122 Again, this was largely because the European Commission tended to issue multiple tenders for single projects, with the objective of increasing competition between firms of the member states.

British companies naturally fared better in ACP CW countries, especially the remaining British dependencies in the Caribbean (as well as in Somalia and Ethiopia or in regional projects involving several states).Footnote 123 Even so, British firms complained that EDF contracts awarded to anglophone states were typically too small and subject to cumbersome procedures to be attractive. Exchange control regulations delayed or impeded the import of materials and the repatriation of earnings, undermining business confidence and activity even when external payment was guaranteed by the EDF.Footnote 124 Tendering for European-funded projects even in ACP CW states may consequently have been less appealing than pursuing other opportunities arising from British bilateral aid, especially through the ATP. Morrissey has shown that in the 1980s, ATP generated more exports than all other forms of aid and that large firms in the works and supplies sectors were the principal beneficiaries: precisely those sectors which had appeared slowest to respond to the opportunities offered by the EDF. For these large British firms ATP had the additional advantage that about one third of ATP contracts were directed at India, China, and middle-income countries to which British firms had historic associations, but which were not included in Lomé.Footnote 125

Whatever the reasons for reluctance on the part of some British firms to tender for EDF contracts, for their part, civil servants remained committed to remedying a situation in which Britain was contributing more to the EDF than it received back in contracts and procurement. By this point, Britain had won some concessions and changes to Commission procedure. It had succeeded in getting the Commission to be more transparent, producing regular and more detailed statistics on the performance of member states’ companies under the EDF, and to improve information flows and the payment system.Footnote 126 Following the second TAAG inquiry, the British government also ramped up its own efforts to publicize the EDF. At the Department of Trade, recently merged with the Department of Industry, a World Aid Section now provided more systematic attention to the business opportunities arising from overseas aid and was busy spreading “the good news [about the EDF] to British industry.” As Powell, at this date still in Brussels, urged: “We cannot give up looking for ways to improve” Britain's share of EDF business.Footnote 127

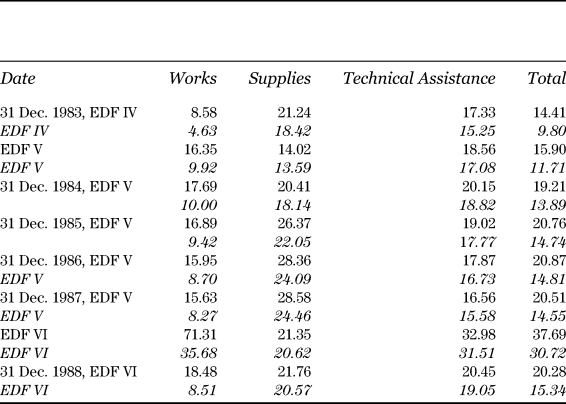

Perhaps because of these various efforts, by July 1983 the British share of contracts was finally increasing, reaching (under EDF IV) more than 14 percent, while that under EDF V grew to around 16 percent. The latter was boosted by the award of a major contract to Rush and Tomkins for the construction of a dam in Ethiopia: a contract won only after intense pressure by the UKRep in Brussels and the ambassador in Addis Ababa to “counter Ethiopian and Italian skulduggery” and (in a comment that speaks to UK government complaints about British business) the firm's own failure fully to “follow the proper procedures.”Footnote 128 Table 5 shows that in the second five years of Lomé's operation from 1983 to 1988 (when EDF IV [1975] was little by little superseded by EDF V [1979], and later on by EDF VI [1984]), Britain's share of contracts awarded to member states’ companies tended to oscillate between 10 percent and 20 percent, much like that of France. As new countries like Portugal entered the EEC, and their own African ex-colonies joined the Lomé Convention, France lost its predominance. In 1987, a transitional year (most of the contracts being still funded under EDF V while EDF VI became operational), British firms for the first time began to overtake French companies. By the end of 1988 the UK share of EDF VI contracts (excluding ACP and Third Countries) was 20.28 percent of all contracts, whereas France had 13.88 percent.Footnote 129 The exceptional British share of the contracts under EDF VI was in part due to one single contract of 11,203.511 European Currency Units allocated to a road construction in Malawi. The successful firm, Stirling Intr. Civil Engineering Ltd., beat twenty other companies including two from France.Footnote 130 French participation in a bid in anglophone Africa, as much as the British score in 1987, was here exceptional, however. More than ten years after Lomé was signed, few French companies ventured to propose an offer for an EDF tender launched in former British colonies and vice versa.

Table 5 Cumulative UK % Share of Contracts under EDF IV-VI by Sector, 1983–1988

Source: Reports from Commission to Council on the results of invitations to tender (E.D.F.), from 1984 to 1989, AHCE. Note: Italicized numbers take account of ACP and Third Countries.

Conclusion

The ten-year period from Britain's entry to the EEC through to the early 1980s represented a distinctive phase in Britain's experience of the EDF. It was bookended by the efforts of two Conservative governments to ensure overseas aid delivered commercial benefits for Britain. In advance of British accession, the Heath government was cautiously optimistic that participation in European aid would advantage Britain, and judged, more generally, that multilateral aid could be a more satisfactory instrument for the promotion of British trade and industry than bilateral aid. Ten years on and this optimism about the EDF had faded. As a late entrant to the EEC, Britain had had to adapt to procedures shaped by the interests and practice of existing member states. Amidst accumulating evidence that British firms were not securing many EDF contracts, and under pressure from the consultancy sector, the first Thatcher government lobbied the Commission to adapt its procedures to redress a perceived bias in favor of French interests. However British civil servants were convinced that the reasons for the poor return on the UK's contribution to EEC aid also reflected the failure of British firms in the works and supplies sectors to exploit EDF opportunities.

While some British firms and business associations were episodically active in lobbying the UK government to improve access to EDF money, our research in UK archives reveals that it was mainly the British government that tried to convince sometimes-reluctant British businesses to capitalize on the opportunities arising from Britain's participation in European aid and realize the returns on the British flow of money to the EDF to which the UK was committed as a price of EEC membership. Eventually during the 1980s, the government's efforts lobbying both the European Commission and British business did bring about an improvement in Britain's share of contracts.

Our findings thus provide evidence of one state's eagerness to use supranational agencies to its own advantage and of the strategies it employed to do so. But they also show that donor states could find their interests thwarted. In the case of the aid instruments of the EEC, this might not only be by other member states with the same ambitions (in Britain's case, France especially) but also by an active European Commission, which, as guardian of the EEC Treaty, was trying to ensure fair competition between member states’ firms in the field of development.Footnote 131 Post-colonial global aid governance could disturb old colonial connections, imposing new kinds of regulations and opening member states’ international chasse gardée (preserve) to competition. Even so, granular analysis of the distribution of EDF contracts shows this was not sufficient to displace established associations between Britain, France, and Belgium and their former colonies. Distinctive features of British and French colonialism respectively had resulted in different commercial, legal environments and currency regimes. This contributed to situations in francophone Africa that British firms, notably in the construction sector, did not consider attractive or deemed too impenetrable to be worth bothering with. Together with the subtle post-colonial influence each ex-colonial power exercised on their “own” ACP states, this ensured that the distribution of EDF contracts reproduced established commercial patterns from the colonial era. It was not just (as Nkrumah had argued) old imperial ambitions but also old geographies of empire that persisted deep into the post-colonial era.

Professor Dimier has published Le Gouvernement des Colonies, Regards Croisés Franco-Britanniques [The government of the colonies, Franco-British perspectives] (2004) and The Invention of a European Development Bureaucracy: Recycling Empire (2014), as well as the edited collection, The Business of Development in Post-Colonial Africa (2021), with Sarah Stockwell.

Professor Stockwell works on British decolonization. Her books include The Business of Decolonization: British Business Strategies in the Gold Coast, 1945–1957 (2000) and The British End of the British Empire (2018), and the edited collections The British Empire: Themes and Perspectives (2008); The Wind of Change: Harold Macmillan and British Decolonization (2013), with L. J. Butler; and The Business of Development in Post-Colonial Africa (2021), with Véronique Dimier.