Introduction

One of the key challenges feminism has set for archaeology is to create accounts of the past which capture its full complexity and diversity, and in doing so challenge monolithic and essentialist narratives that do little more than justify political structures in the present. The twin aims of feminist archaeology from the 1980s and 1990s, to challenge modern gender hierarchies being unthinkingly found in the past and to promote parity in employment (Conkey Reference Conkey2003), have by no means been met. Despite women under 40 dominating the discipline in terms of numbers (both as students and in employment), senior positions tend to remain the preserve of men— and most often white men from privileged backgrounds—while indigenous communities and BAME archaeologists are drastically under-represented (Aitchison & Edwards Reference Aitchison and Edwards2008). Reflections on the ‘leaky pipe-line’ and sexual harassment under the banner of the #MeToo movement (e.g. Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020) may yet speed up change, but there is much work to be done (Rosenzweig Reference Rosenzweig2020). The issues are structural, rather than tied to individual histories, and made out of the fabric of the world we live in and with very real consequences of violence, economic access and prestige. Simply trying to challenge existing gendered hierarchies is not enough; we need to consider how we can bring about deeper changes, which involves refiguring how pasts and histories are captured, so we no longer support essentialist categories in the present.

One route we have found productive in our own work is provided by post-humanist feminists such as Braidotti (Reference Braidotti2011; Reference Braidotti2013) and Barad (Reference Barad2007) and their emphasis on rethinking concepts of difference (e.g. Bickle Reference Bickle2020). Feminist archaeology has historically drawn on second-wave feminists such as de Beauvoir (Geller Reference Geller2009, 67), focusing on the systems and structures which maintain oppressive conditions for women (Handley Reference Handley2000, 17; Voss Reference Voss2000, 182). We contend here that this has led to a heavy focus on these ‘big questions’, at the expense of an investigation of lived experience. More recently, feminist archaeology has drawn on ideas of identity politics to situate itself, focusing on individual identity, the nature of the expression of gender, and whether gender can be considered to be embodied. This draws heavily on ideas about intersectionality and theorists such as Butler (Reference Butler1990; Reference Butler1993). However, this can lead to an almost isolationist view, perceiving women in history set apart from everything else. Both of these approaches have issues in the way womanhood is defined, in particular because the salient characteristic of being ‘woman’ is not being a man (Butler Reference Butler1993)—a definition which is not only static, but works to reify current understandings of difference as ‘defined-by-lack’ (Deleuze & Guattari [1983] Reference Deleuze and Guattari2013). In place of the concept of difference ‘defined-by-lack’ (categorizing different identities as groups of similar characteristics which can only overlap in a minor way with other identity classes), Deleuze and Guattari ([1983] Reference Deleuze and Guattari2013) recommend searching to find ‘difference defined-within-itself’, that is, exploring how assemblages open up multiples of differences rather than reducing everything to central norms. This has been adopted in different ways by New Materialist feminists, but key for us here is how they seek to find new ways of casting communities and identities that refute the ‘norm’ and ‘other’ divide. Thus, they propose we can research differences to challenge methods that reinforce biological essentialism, and in our specific case here, rejecting the idea that there is a ‘correct way’ to be a woman or, indeed, a man. Here, through contrasting case studies from the nineteenth century ce and the second half of the sixth millennium bce, we wish to show how, following posthumanism, we can capture something of how difference can be an ‘imminent, positive and dynamic category’ (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2019, 12), thus aiding us in writing pasts into being that are accountable to the present.

Relationality and emotionality in relation to posthumanism

Posthumanist feminists seek to challenge the enlightenment approach to the world, which seeks its division into bounded categories in order to make sense of and support existing hierarchies of value and significance (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2019). By refiguring the world as consisting of ‘heterogenous assemblages’, posthumanists seek to explore how different and ongoing meetings of things, people, ideas, non-human agents and so on bump up against, meld into and change each other, at multiple scales (Crellin Reference Crellin2017; Harris Reference Harris2017). In doing so, feminist philosophers, such as Braidotti (Reference Braidotti2013; Reference Braidotti2019), follow posthumanist modes of thought to allow different non-hierarchical views of the world to emerge. In this sense, posthuman philosophies, as adopted in archaeology, seek to explore how things, people, concepts emerge through relations, without placing human action as top of a hierarchy of importance in knowing the past (Crellin Reference Crellin2017). This change in approach, sometimes referred to as a ‘flat ontology’ (Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021), is critiqued as missing an important political dimension, or at worst overlooking the ethical imperative of acknowledging agency in the human past. Here, rather, we argue that embedding human politics fully within the assemblage of the material world from which it emerged helps us to think beyond the categorizations that frame our own experiences of the world as researchers of archaeology in the early twenty-first century ce.

An assemblage can be a deliberate act of bringing together or gradual enmeshing of different materials in the world, where there is an implication of a relationship between parts and the whole (Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017, 80). Archaeological practice is thus also an assemblage, which includes the archaeologist interpretant (Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017, 81). Hamilakis and Jones (Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017, 83), however, critique the assumption that the relationality embodied in assemblages is unidirectional or ‘dependent’, that there is an object and a subject, as well as the idea that assemblages are fixed and singular. Rather, assemblages are dynamic and ever-changing, and the relationships between the agents within assemblages are similarly dynamic (Crellin Reference Crellin2017; Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017). Agents can be part of multiple assemblages, and the specific configuration of those assemblages defines the relationships between their constituent parts in different ways (Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017, 79). In this way, assemblages are immanent, continually ‘becoming’ through the relationships embodied within them. Focusing on relationality in these terms means recognizing that relationships within assemblages ‘make a difference’, in that bodies, communities, objects, concepts, emerge in the relationship (Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021, 23). Thus, not all relationships within assemblages are alike, and have their own histories, creating, maintaining and dissolving assemblages (Harris Reference Harris, Crellin, Cipolla, Montgomery, Harris and Moore2021, 27). Assemblages, fundamentally, are an articulation of these differing relationships; of the material, conceptual and emotional (Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017, 82). For us, the salient point for human agents within assemblages is that they are emotionally affected by their relationships within the assemblage, by other humans, by objects, by place and by ideas. In this way, we draw a comparison between the concept of relational assemblages (as defined by Crellin Reference Crellin2017; Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017; Harris Reference Harris2017), and the call of Supernant et al. (Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020), in their Archaeologies of the Heart, for more focus on interpersonal relationality, and emotionality as a means of rejecting enlightenment rigid categorization of the world.

Baxter (Reference Baxter, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020) draws on Rosenwein (Reference Rosenwein2015) and Fleisher and Norman (Reference Fleisher and Norman2016) to define the term ‘emotional communities’ as part of a methodology for accessing these interpersonal groups. Baxter (Reference Baxter, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020) defines ‘emotional communities’ as small, relational groups, which share particular attitudes to emotion and emotional expression in response to specific circumstances. Membership of these groups is non-exclusive. People belong to multiple emotional communities simultaneously and can move seamlessly between them, altering their behaviour accordingly, in the same way that agents can be part of multiple assemblages and relate differently within them. These communities are made up of the interpersonal relationships of the people within them, centred around ideas of place (e.g. ‘evocative spaces’) or things (e.g. ‘affective objects’). Such communities, not representative of entire cultural groups, are curated through shared experiences of emotionality, and by their interconnected relationships with these places and objects (Baxter Reference Baxter, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020, 128). Emotionality in this sense does not mean shared experiences of emotion (e.g. everyone feels happy together, or sad together): rather, that as such relationships are built, they become powerful in pulling people into relation with each other, places and objects. Similarly, if unmade by political suppression that cannot be resisted, or changing fashions, such relations can unravel and dissolve. We therefore suggest that ‘emotional communities’ could be considered an assemblage from a methodological perspective, or, perhaps more interestingly, that considering assemblages from the perspective of the emotional communities they contain may help us to move beyond rigid and all-encompassing identity classifications, that despite strong critique continue to persist in archaeological accounts of the past.

A focus on ‘emotional community’ as a specific relationship found within assemblages focuses explicitly on how people construct their interpersonal relationships around non-human agents such as objects and space, and the way these non-human agents influence interpersonal relationships. In this way, the interpersonal relationships between people, and between people and things, become the focus of study, with object and place as archaeological entry points into the construction of these relationships. We find much coherence between this approach and the call of post-humanist feminists to abandon the category of ‘human’ as defined by the Enlightenment through binaries and opposites in favour of relational identities. Particularly, both require an intellectual rigour in maintaining that sense that ongoing becoming, challenging fixed categories, and, as Lyons and Supernant (Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020, 5–6) emphasize, keeping alert to the ‘rhizomes’, constantly searching out interconnections within and between assemblages. Here, adopting a Deleuzian approach to ‘difference defined-within-itself’ (Deleuze & Guattari [1983] Reference Deleuze and Guattari2013) proves useful. It helps us not only to recognize that these communities are not classificatory groups, made up of people adhering to a ‘norm’ (though group membership can be policed at times, this rather proves the point that difference occurs in at times unmanageable ways), but to examine how difference is a productive and dynamic force (Bickle Reference Bickle2020; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021); crucially, that these ‘emotional communities’ (e.g. women) are not defined by the absence of those who belong to different ‘emotional communities’ (e.g. men), but by participation in the assemblages of different people, spaces and objects within them (e.g. colleagues who participate in similar tasks, share varied physical, cultural, and economic affordances and restrictions, which elicit a range of emotional responses and create social connections). Crucially, this concept moves our attention away from classification, which directs attention to the borders between identity categories (of what were demonstrably not closed groups), and towards the fluid connections built within them. We thus use the concept of ‘emotional communities’ here as a framework to consider and enliven differences found in what we broadly identify as a posthumanist feminist account of gender in the nineteenth century ce and second half of the sixth millennium bce.

Our chosen case studies come from our respective periods of expertise and interest, but also share many similarities in current archaeological approach. For the nineteenth century ce and the second half of the sixth millennium bce, gender has often been taken for granted, though in different ways. The modern cultural category of ‘women’ owes much to the gendered constructions of the nineteenth century, and as such the historical study of women in the nineteenth century has been part of a reflexive, self-sustaining cycle. When oppressive masculine narratives are regarded as evidence of women's lack of influence, then women's lack of agency and voicelessness is both taken for granted and perpetuated. For the Neolithic in central Europe, while there have been some recent explorations of gender (cf. Bickle Reference Bickle2020; Robb & Harris Reference Robb and Harris2018), for the most part the categories of men and women have largely been an implicit backdrop to the discussion of social changes, again taken for granted as categories which pre-exist any creation of specific and unique ‘Neolithic’ perception of the world. In both cases, the category of women is usually downplayed and viewed as having an insignificant role in our understanding of these periods in archaeological texts. We explicitly and unapologetically set ourselves the challenge of starting with the female as an archaeological interpretative category and exploring the threads of assemblages within the framework of emotional communities to investigate how new accounts of these pasts emerge. For emphasis, while ‘female’ is the place we begin, we take it up in discussion as a space in which differences open up. It is thus not an essential, or essentializing, category, but a point of contrast from which we can explore how the concept of female differs and changes through time.

Nineteenth century ce: bereavement and divergence from the ‘standard lifeway’

Narratives of the nineteenth century in the UK, particularly narratives about gender, are heavily influenced by the idea of ‘separate spheres’, the separation of public and private, of masculine and feminine. This draws heavily on the perceived Victorian ideal of domesticity, of men as breadwinners and women as wives and mothers, and discussions of masculinity and femininity are often built around a kernel of domesticity (e.g. Davidoff & Hall Reference Davidoff and Hall2018; Gordon & Nair Reference Gordon and Nair2006; Langland Reference Langland1995; Shoemaker Reference Shoemaker1998). However, though the ‘conjugal family’ has been considered the dominant domestic model in the UK for the past few hundred years (Holmes Reference Holmes2014, 315), this view of domesticity does not appear to reflect the living situation of many people in the period. It does not account for those who never married, who lived with siblings and cousins, who lodged for years in boarding houses, or who lived within the household of their employer. In York in 1861, 20.5 per cent of households were female headed, and 51.8 per cent of adult women were listed as having an occupation. Only 37.3 per cent of adult women were married and living in households in which their husbands were the head, and many of those women were also living with extended family, lodgers, or employees. This pattern of non-nuclear domestic arrangements appears to have been repeated across the country (see Cooper & Donald Reference Cooper and Donald1995; Holmes Reference Holmes2014). It is clear that this model of domesticity, and the ‘standard’ lifeway, cannot be assumed to be representative of the multiplicity of the experiences of nineteenth-century women. Widowhood, and in particular, widowhood at a young age, represents a particular life experience which diverges from the ‘standard’ lifeway; through the examination of the material culture of mourning, it is possible to begin to investigate how the shared experience of grief may have created emotional communities.

Although undertaken throughout society, the exaggerated performative dress which characterized mourning wear in the latter half of the nineteenth century is almost universally associated with women. Mourning wear can therefore be considered an explicitly feminine expression of grief, or at least, an acceptable expression of women's grief. Mourning wear can be characterized, archaeologically and socially, through its materiality and its colour. Largely black in the instance of deep (or first) mourning, and expanding to include sombre colours such as white, grey and pale purple as mourning progressed, mourning wear was heavily associated with materials such as crape and bombazine, jet and seed pearls (Taylor Reference Taylor2009, 202–4, 229, 234). Such elaborate performative mourning has often been associated with social climbing, with women used as showpieces by their families to demonstrate the family's virtue, respectability, and, most importantly, means (Taylor Reference Taylor2009, 136). The spread of mourning dress, along with the elaborate funeral procession and other accoutrements, throughout Victorian society has been characterized as an effort at class emulation (Cannon Reference Cannon1989, 438–9), an argument which was commonly used in the period to dissuade expenditure on such lavish funerals (e.g. Chadwick Reference Chadwick1843). Performative mourning, it has been argued (Curl Reference Curl2000; Ruberg Reference Ruberg2008; Taylor Reference Taylor2009), was largely indicative of status, control and the effects of peer pressure, rather than an expression of true grief. However, narratives based around status aspects of performative mourning are arguably based on conventional narratives constructed around class, which have their origins in the nineteenth century and continue to be enacted today, and uncritically interpreting evidence from the past in those terms can only reinforce them. By rejecting assumptions based around opposition and competition, and instead seeking to find connections and relationships in the past,we can begin to move away from interpretations rooted in conflict and the binary.

Research into the emotional aspects of nineteenth-century mourning jewellery, and its status as objects of embodied memory and grief (e.g. Hind Reference Hind2020; Holm Reference Holm2004; Lutz Reference Lutz2011; Sheumaker Reference Sheumaker1997), has begun to question the idea that such objects were purely performative. Lutz (Reference Lutz2015) examines the materiality of these ‘secular relics’, which often contained locks of hair, photographs and miniatures, through their depictions in literature, as tactile objects of remembering. Such depictions show the highly private nature of people's interactions with mourning objects. They were objects to be handled, often kept close and hidden beneath clothes, and which maintained a tangible physical connection between the living and the dead (Lutz Reference Lutz2015, 1–3). Examination of these objects as private objects of grief not only questions the narrative that the nineteenth-century mourning boom was primarily driven by peer pressures and social climbing, but also highlights that emotionality often forms an integral part of the way people interact with material culture. Mourning jewellery both reflects the desire to maintain a continued relationship to the dead, as well as the centrality of material culture to the building and maintaining of such relationships. Emotionality and relationality are at the heart of people's interactions with mourning objects; narratives which reject these aspects cannot provide a complete understanding of their use. It may also be necessary, therefore, to apply this relationship-led focus not only to objects of private mourning, but also to performative mourning wear, and to consider mourning wear as a method of reconstructing relationships following bereavement. It is possible to start to investigate more about the way bereaved women interacted with each other by dismantling the assumption that mourning culture is something oppressive, forced upon women to control their mode of dress and social lives (Taylor Reference Taylor2009, 136). The sheer amount of clothing on offer, as well as its marketing by retailers, is more indicative of the amount of choice available. Newspaper advertisements in the 1850s are often specifically addressed to ‘ladies of the city’ (e.g. George Bland, Mrs Cooke, T. Cooke & Co.). The advertisement offering the latest styles for the season, in a range of fabrics and cuts, with ‘mourning orders executed with utmost despatch’ (Quarton and Brown in Yorkshire Gazette 17 January 1880), does not suggest an oppressive control over women's dress, but rather offers insight into the economic agency of the female consumer.

A second assumption, drawn from popular culture tropes from the time, was that mourning dress was worn by women trying to capture a new husband. This, however, does not take into account the long mourning periods recommended for all manner of relatives. At two years for parents and mothers-in-law, a year for children, and six months for brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and grandparents (Taylor Reference Taylor2009, 303), a woman who strictly observed mourning could be in black for upwards of 10 years over the course of her life, with few reliable ways for onlookers to determine if she had been widowed. If mourning served a social function of letting eligible men know that a woman was becoming available, then it seems reasonable that mourning for widows would be in some way exceptional, but this does not appear to be the case.

This stereotype relates directly to humour tropes and literature from the time, which portrayed widows as manipulative, dangerous because of their maturity and sexual experience, which would allow them to ensnare and seduce men (Muller Reference Muller2020). Muller (Reference Muller2020, 929) argues that this humour comes from a lack of comfort with sexually and romantically experienced women, as well as the fear that the exaggerated mourning costume favoured by women in the second half of the nineteenth century was concealing a lack of grief (Muller Reference Muller2020, 934). The disentangling of assumptions in research from these contemporary stereotypes and tropes is particularly important in this period, due to the association of these ideas in the construction of modern narratives about gender, race and class. These narratives exist in the present because they were constructed in this period, so by uncritically drawing on them in our research, we tacitly reinforce them in the modern world.

Remarriages were, in reality, rare (Muller Reference Muller2020, 928). Farr (1885, 78–80, cited by Muller Reference Muller2020, 928) reported that while a fifth of widows aged between 20 and 24 were likely to remarry, this dropped to only 4 per cent of widows aged 40 to 44. This is supported by parish records from the period. Between 1861 and 1874, in York, of 436 individuals married, only 10 per cent were wedding their second spouse, though bereaved spouses made up 20 per cent of all marriageable people. There were an equal number of men and women, despite widows outnumbering widowers in every age bracket. Women were also likely to remarry younger, with 78 per cent of widows remarrying aged under 46, compared with 56 per cent of widowers. This means that despite making up 82 per cent of widowed women, those aged over 45 were very unlikely to remarry at all.

This is therefore likely to represent a difference of experience of widowhood. The majority of women could reasonably expect to marry once, and to remain married well into middle age. To be widowed young, while not uncommon, could be considered unlucky. Only 4 per cent of women under 46 were living as widows. If, as Jalland (Reference Jalland1996, 234) states, ‘most widows felt dislocated, disorientated and unutterably alone’, then to be a young widow, living a very different lifeway to many of your peers, must have felt very isolating. Over half of these women had children under 16 at home, and more than three-quarters were listed as having some form of employment. It is therefore not reasonable to conclude that these women sequestered themselves for a year of full mourning (Taylor Reference Taylor2009, 303). Although a life has come to an end, life itself has not halted.

While there is no universal experience of grief, bereavement is a defining experience for many, which drastically affects the lifeway. Drawing on research into psychology and sociology, it is possible to consider some of the ways the emotionality of grief affects behaviour, and the behaviour of those around the bereaved. Toth (Reference Toth1997, 86–7) identified the period from 2 to 12 months following a death as particularly hard, because the intense support that is present at the beginning from friends and family begins to wane. It can be an isolating experience, as past friends and family become difficult to relate to (Toth Reference Toth1997, 84). Many studies show bereaved people seek out those who have had similar experiences, such as through support groups, to reduce feelings of isolation (Elder & Burke Reference Elder and Burke2015, 181; Toth Reference Toth1997, 90). Those who do consistently report better mental health and recovery following bereavement (Elder & Burke Reference Elder and Burke2015, 185). Through applying this to the nineteenth century, it is not unreasonable to assume that widows, particularly young widows whose life experience may be ‘out of step’ with their peers, might seek out connections with women in a similar situation.

The socially acceptable places for women to socialize and be seen, unaccompanied by a husband or other male relative, were limited, certainly for middle-class or aspiring women (Brück Reference Brück2013, 212). Shopping, and the retail sector, was, and is, considered to be the domain of women (see Abelson Reference Abelson1989; Rappaport Reference Rappaport1996; Stobart Reference Stobart2017), while parks and the new cemetery gardens were a place to promenade with the family (Brück Reference Brück2013, 212). Women might also entertain each other at home, over tea (Gray Reference Gray2009, 48–50; Harvey Reference Harvey2008, 206), and condolence visits to the bereaved's home was encouraged for close friends (Beeton Reference Beeton1888, 10). A major issue in this period is the ability to access the reality of life experience, uncoloured by the overarching documentary evidence, while still making reference to it as contextual information. In other words, just because etiquette manuals and writers of the period considered that ‘respectable’ women would never be seen in music halls or unaccompanied in the street does not mean that women abided by that. Nor does it imply that the working-class women who frequently went dancing (Parratt Reference Parratt2001, 120–22) considered themselves unrespectable. Because of our socialization as gendered and encultured individuals, it can be difficult to untangle ourselves from ‘what goes without saying’ (Bloch Reference Bloch1998). It is therefore necessary to interrogate our assumptions. However, it is perhaps not unreasonable to begin with the assumption that, in a society in which ‘appropriate’ behaviour between the sexes appears to have been heavily socially policed, women were perhaps likely to seek out other women to socialize with.

Young widows, who may have been more at risk of social scrutiny, in part due to the cultural depiction of them as manufacturing their grief to increase their social standing (Muller Reference Muller2020), and who may have had experience of a lifeway which has diverged from many of their peers, may also have experienced a feeling of isolation from their social group. In this case, it may be possible to begin to consider a duality in women's use of increasingly elaborate and fashionable mourning wear, not as purely indicative of a social stigma, meant to mark them out from the rest of society, but also as a way to find a connection to other bereaved women. It is possible perhaps to characterize this shared, or similar lifeway, as creating an interconnected emotional community (Baxter Reference Baxter, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020, 136).

Accessing these emotional communities archaeologically is not without difficulties, and the possibility and desirability of accessing emotionality through archaeological evidence has been long debated (e.g. Harris & Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2015; Swenson Reference Swenson2010; Tarlow Reference Tarlow2000; Reference Tarlow2012). However, Lyons and Supernant (Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020, 10) argue that, rather than an emotional archaeology which seeks to locate specific, isolated emotion in the past, emotional archaeology should be focused on understanding the ‘web of relationships that make up communities’. When creating interpretations of the past, we should not seek simply to ‘prove’ the existence of feeling, but to work under the assumption that emotion plays a vital role in the way people conceive of themselves and their relationships (Lyons & Supernant Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020, 11). Baxter (Reference Baxter, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020) begins to create a model for how this can be done in the post-medieval period through the analysis of childrens’ graves as evocative objects, which invoke emotion in people, and create spaces in which people can share feeling.

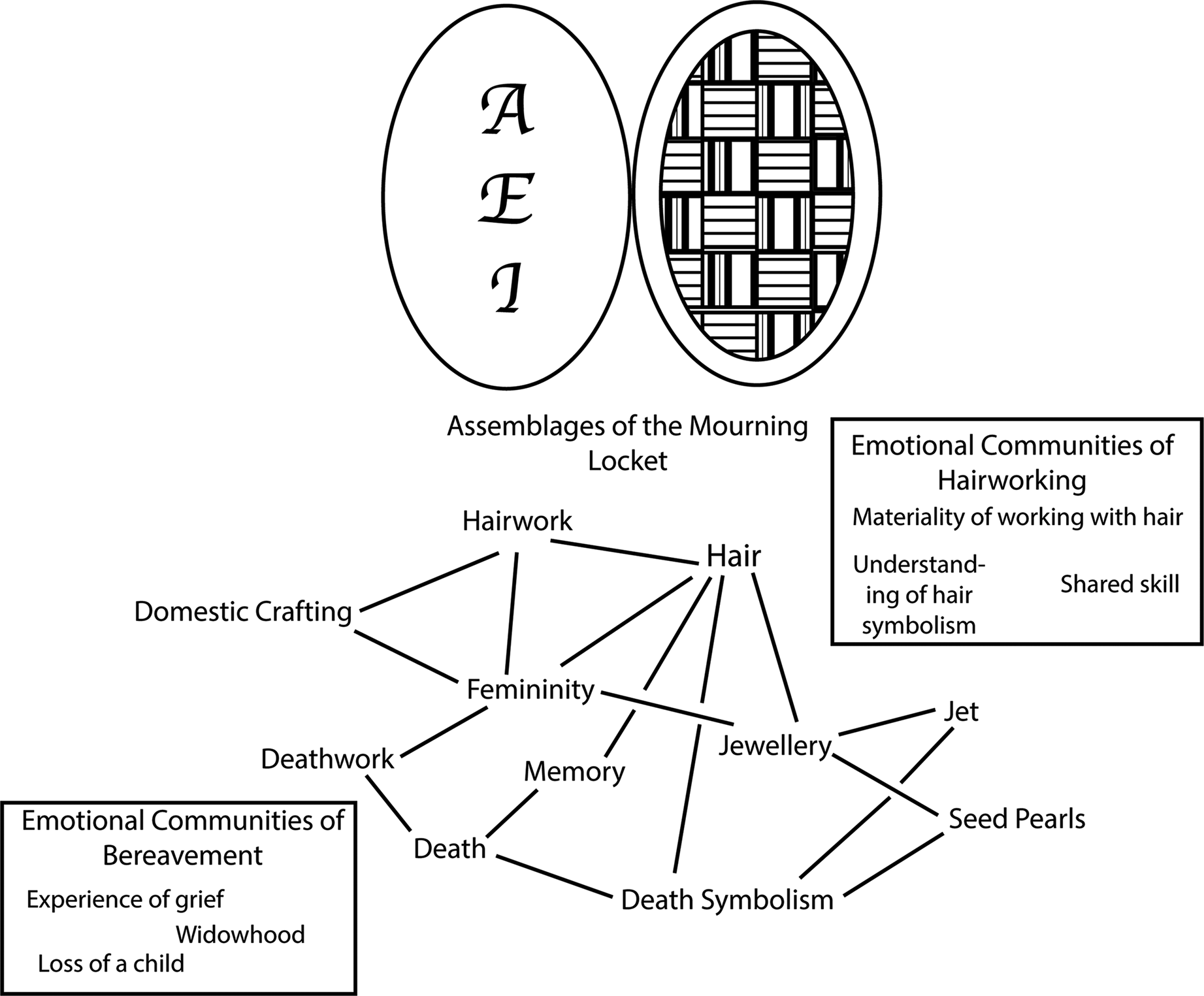

The challenge for archaeologists, therefore, is to access these evocative objects and spaces. In this period, this can be applied by analysing mourning wear not through the lens of status objects, meant to elevate, but as objects of emotion: objects worn to identify the wearer as a member, however temporarily, of an emotional community which can support them (see Figure 1). It may be possible also to analyse the evocative spaces used by this community spatially, such as through analysis of the experience of mourning retailers, and how their layout was designed either to separate or to bring shoppers together.

Figure 1. The differing emotional communities expressed through nineteenth-century mourning lockets.

This has shown that it may be possible to begin to uncover something of the diversity of lifeways in the nineteenth century, by focusing on a small specific group, young widows. However, it is necessary to expand this to include more diverse narratives around class, queerness and race. Archaeological analysis into this has been limited, as indeed has the analysis of urban social life in this period in general; however, an archaeological analysis focused on the emotionality, relationality and lived experience of women in this period can begin to dismantle the overwhelmingly male, middle-class narratives which characterize our understanding of the nineteenth century.

Sixth millennium bce: tasks that shape bodies, identities and gendered communities

In contrast to the ‘separate spheres’ of the nineteenth century, the sixth millennium bce in central Europe, with the transition to farming, tends to downplay gender as an issue of significance for the large-scale changes that occurred alongside population movements, choosing instead to reserve gender for more small-scale assessments, mostly in concert with the burial evidence. The impact of this is that the ‘big’ changes of the Neolithic, with presumed greater relevance to the overarching story of humankind, are largely placed in the hands of neutral dis-embodied agents or populations. We know by now, of course, that they are not neutral—wherever gender remains uncharacterized, those agents that are empowered to be dynamic and able to create change through history, are thus implicitly gendered as male. Some attempts have been made to explore Neolithic gender over larger scales (Robb & Harris Reference Robb and Harris2018, 140), which have suggested that gender was situational to particular settings, perhaps operating as a cosmological category only loosely tied to the biological sex of bodies. This contrasts sharply with many accounts that envisage Neolithic gender as fixed, static across the lifecourse and the basis for other forms of inequality (e.g. Jeunesse Reference Jeunesse1997; Moddermann Reference Modderman1988; Nieszery Reference Nieszery1995; Pavúk Reference Pavúk1972; Röder Reference Röder, Auffermann and Weniger1998; van de Velde Reference van de Velde1979; Veit Reference Veit1993; Reference Veit1996). Thus, what is classed as ‘women's work’ is often devalued in our narratives of the Neolithic; lithic networks are active exchange systems which represent channels of communication through which the Neolithic may have spread; pottery styles, though they change frequently through time, are stable, reliable and somewhat passive reflections of identity (see discussion in Bickle Reference Bickle2020). In contrast, here, we wish to explore what could be broadly classified as the tasks that shaped divergent lifeways, but are mostly thought of as associated with the female sex in the early Neolithic culture of the Linearbandkeramik (LBK: 5500–5000 cal. bc), specifically grinding cereals and working hide. Drawing on the concept of emotional communities, the scale and form of relationships built through these tasks are examined, in order to expose the diversity of possible identities experienced.

Macintosh et al. (Reference Macintosh, Pinhasi and Stock2017) found that overwhelmingly the upper limb loading of LBK female skeletons, represented in humeral rigidity, was higher than that expected of modern athletes and of Neolithic males. This was interpreted as arising in the shared manual tasks females were carrying out, particularly those related to the farming and processing of crops. Here, we propose that grinding cereals was one of the emotional communities in which those with mostly female bodies came to form a relational and contextual understanding of their identity, through the assemblage of bodies and querns. LBK grinding stones were carefully crafted from local sandstone, sought in the vicinity of the settlement, and were mostly loaf-shaped querns, which would have required a back-and-forth motion with two hands (Hamon Reference Hamon2008). Over the lifecourse, arms would have been slowly strengthened and hardened by the repeated motion of grinding, with aches and pains building up in certain parts of the body; a shared set of immanent experiences around which to structure notions and understandings of the body for those participating in this action. In turn, the quern's surface would begin to dip and the texture and feel would let any user understand its age. The different techniques of body position, speed, force and angle could have been learnt from copying or instruction, subtly displaying different household styles after a long apprenticeship that could have lasted several years (Hayden Reference Hayden1987). If muscles were built over a lifetime, this activity could have also formed shorter, daily constructions of time, with ethnographic examples illustrating a range of different approaches to scheduling this task, from 15 minutes at a time, at regular intervals, to grinding cereals accounting for up to five hours of work a day (Alonso Reference Alonso2019). Conversely, querns stones can have long lifetimes, outliving their first owner and bringing connection and belonging to subsequent owners. Grinding stones are sometimes given names such as ‘mother’ and ‘child’ in agricultural societies (Hamon Reference Hamon and Hofmann2020, 35); perhaps in the LBK context, grinding stones could similarly have flowed through close kin relationships.

Though grinding stones may have helped to shape notions of the body that carried out the task, and particularly senses of settlement time, this did not mean they fell entirely within a ‘female sphere’. Grinding stones are found in LBK grave assemblages in low numbers, in about 6 per cent of graves, but across the whole demographic population, from neonates and young children, as well as in the graves of males and females (Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Bentley, Bickle, Bickle and Whittle2013, 379). These long-lived objects therefore rarely found their way into grave good assemblages, but when they did, it was suitable to bury them alongside those we imagine to have a range of different identities, including small infants, who could have never used them. From this we can surmise that grinding stones were not simple symbols of their main user's identity, or deposited due to pollution on death. Rather, they may have evoked deep emotions associated with the care offered by parent to child, by a loving spouse, or a close-knit community. Similar acts of attention and care are seen in the composed deposits of grinding stones found in northern France during and after the LBK (a small number of such deposits are also found further east: Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Hofmann2020), where they do not appear in graves, but rather as seemingly staged deposits associated with the pits alongside houses (Hamon Reference Hamon and Hofmann2020). These deposits are found in settlement pits, neither at the base, nor in final fills, but during the time the pit was actively receiving material (Hamon Reference Hamon and Hofmann2020) and are therefore unlikely to be a foundation or closing deposit for the house. Hofmann (Reference Hofmann and Hofmann2020, 136) makes the interesting suggestion that these deposits could have worked akin to magic, referencing the practice of depositing bundles of objects by North American Plains groups. Although it would be wrong to draw a distinct line between large public rituals and these smaller-scale events, bundles tend to be groups of objects deposited in various different locales, and find their power through the intimate assemblage of objects and substances combined (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Hofmann2020, 135).

Evidence from elsewhere further supports this notion, such as the querns from Geleen-Janskamperveld (Netherlands), where their use was brought to an end by deliberate fragmentation, an event also marked by the deliberate smearing of ochre on the surface (no evidence for use-wear polish and striations from grinding ochre could be found: Verbaas & van Gijn Reference Verbaas and van Gijn2007, 197). Ochres, too, can take on gendered characteristics in many societies, coming from the ground, an active, transformative substance which can take on the qualities of blood, thus becoming a ‘life-force’ in its own right (e.g. Boivin Reference Boivin, Boivin and Owoc2004). Found in lumps or sprinkled on the body in graves, ochre suggests further parallels and associations entangling querns and bodies together in shared histories. For example, at the cemetery of Kleinhadersdorf (Austria), both grinding stones and ochre are found more frequently in graves than elsewhere (Bickle et al. Reference Bickle, Bentley, Blesl, Bickle and Whittle2013; Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Bentley, Bickle, Bickle and Whittle2013, 379). This has been interpreted as suggesting the grinding stones were used for grinding colour and therefore had a ritual significance (Neugebauer-Maresch & Lenneis Reference Neugebauer-Maresch and Lenneis2015). Here, we suggest that such divisions were not so clear cut, and the combination of quern and ochre was a powerful combination of active materials, expressing the relational and emotional community of the female body and the provision of food, acts of care bound up in sharing daily activities and consumption.

Verbaas and vin Gijn (Reference Verbaas and van Gijn2007) also found querns were regularly placed on a soft material, such as a hide, which left its own traces on the quern stones, polishing and rounding the base of querns. Following this assemblage of quern and hide offers further possibilities to explore emotional communities that may have shaped female lives in the LBK. Polished stone tools are usually regarded as the domain of men in the LBK, almost exclusively being found in male graves. However, a small number are found in female graves, and recent use-wear analysis has shown that these were almost exclusively used against soft, flexible materials, mostly likely in the course of hide working (Masclans Latorre et al. Reference Masclans Latorre, Bickle and Hamon2021). Hide working, much like grinding cereals, is often dismissed as an insignificant daily task, with women dependent on men to supply the raw materials of stone tools and animal skins (Spencer-Wood Reference Spencer-Wood, Frink and Weedman2005). The use-wear traces on stone tools suggest hide working in the LBK produced very high quality hide, and accounted for wear traces on up to 50 per cent of stone tools at the settlement site of Elsloo, illustrating the speed with which the end scrapers used for this task became worn (van Gijn & Mazzucco Reference van Gijn, Mazzucco, Hamon, Allard and Ilett2013). Hide working, and possibly leather working as well, was thus not an insignificant task carried out at settlements. In many ethnographic examples, however, hide working is a highly skilled task, with not everyone being able, or choosing, to learn the techniques (surveyed in Frink & Weedman Reference Frink and Weedman2005). Thus, for the Yup'ik women of the Arctic, hide working was one of a number of skills that was part of becoming ‘big women’, providing them with independence and influence, with emphasis falling on the enskillment of themselves and others, rather than on the economic advantages of producing hides (Frink Reference Frink, Frink and Weedman2005; Reference Frink2009, 22). Polished stone tools occur in about 5 per cent of female graves (Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Bentley, Bickle, Bickle and Whittle2013, 378), and here we suggest that such activities could similarly have allowed a small group of mainly female-sexed bodies to distinguish themselves.

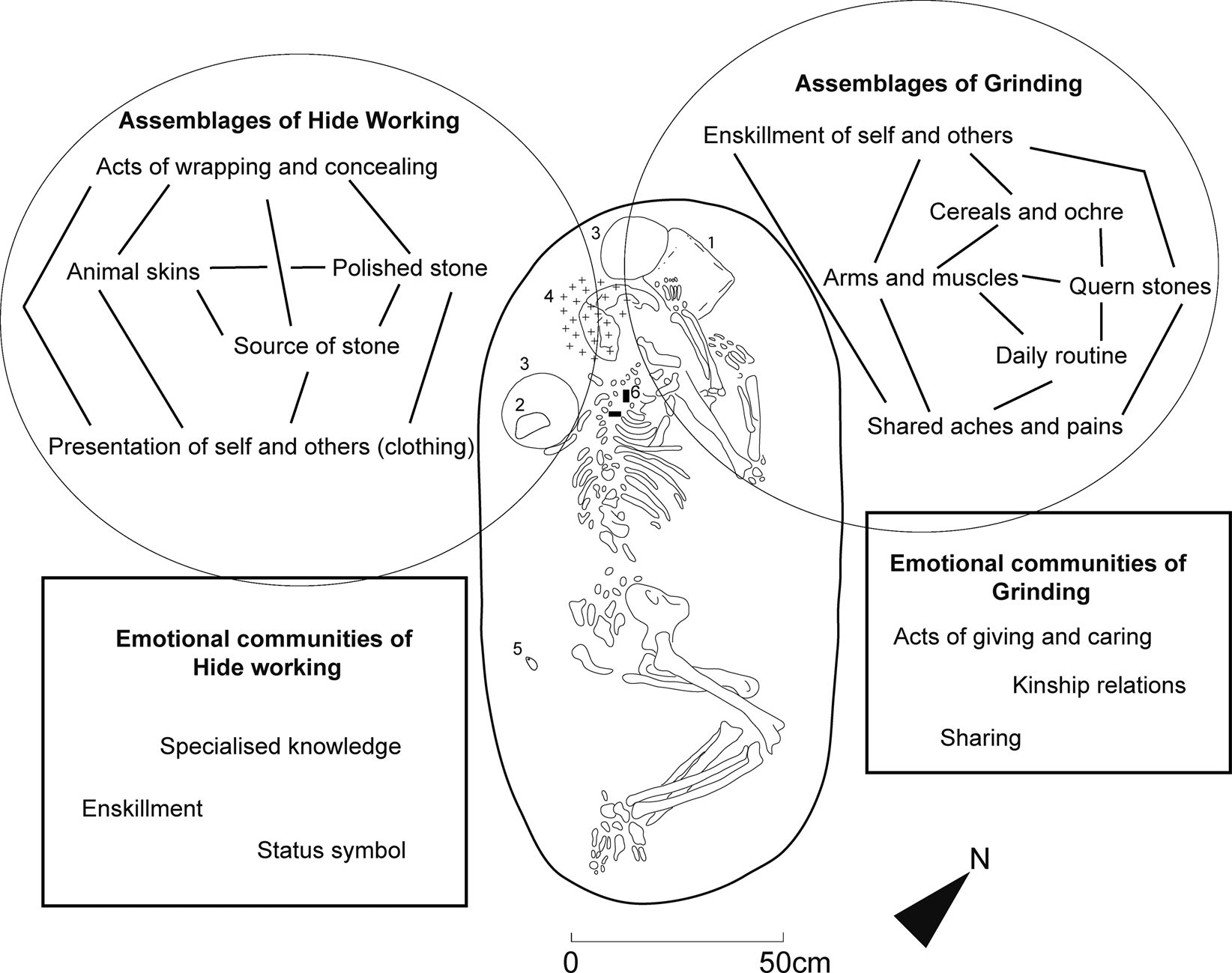

Hides have roles not only in clothing the community, but can also be significant in ritual activities; thus they can also be objects of transformation (Spencer-Wood Reference Spencer-Wood, Frink and Weedman2005), much in the same way that querns help transform cereals into breads for consumption. In this regard, it is interesting to explore the assemblage of grave goods placed with burial 36/76 as the cemetery of Vedrovice. Here an older adult female, estimated to be 45–50 years old at death, was buried with a grinding stone placed close to her head, with one hand resting on it; a polished stone tool, used for hide production, was placed at her shoulder inside a pot, and between these two deposits ochre had been sprinkled around the back of her skull (Figure 2; Podborský Reference Podborský and Podborský2002, 41). Here we see a community of objects drawing strongly on spheres of what is likely to be mostly female endeavour: the quern under her hand, forming a direct link between the body and the object which shaped it, and at her shoulder an object which had been intimately involved in clothing and protecting the body in life, perhaps wrapping it in death (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Garrow, Gibson and Giles2019. Together, envisaging grinding cereals and hide production as assemblages of bodies, materials and substances that formed emotional communities likely to have shaped female bodies, apprenticeships, lifeways and roles in the community, has revealed two probably deeply valued and symbolized taskways, largely overlooked as significant to Neolithic societies (cf. Hamon Reference Hamon and Hofmann2020). Following the approach of post-humanist philosophers, gendering these tasks does not result in them emerging as routine, insignificant, or devalued, but rather, they appear firmly embedded within broader value systems, expressed in deposition, in grave good assemblages and special deposits. However, an important dimension in both these emotional communities is the immanent potential for diversity to appear through the learning process as someone moved from apprentice to master, through differences in style between households, and in those who may have emerged as particularly renowned and celebrated for their craft. The next direction for this research is to explore the histories of hide working and of grinding through the Neolithic, considering how the assemblages they are part of converge and diverge through time.

Figure 2. The differing assemblages and emotional communities expressed through the burial of 36/76 (adult female, 45–50 years at death) at Vedrovice, Moravia. (1) grinding stone; (2) polished stone tool; (3) pottery, (4) spread of ochre; (5) Spondylus pendant; (6) Spondylus beads. (Redrawn after Podborský Reference Podborský and Podborský2002, 41, fig. 36.)

Conclusion

In writing accounts of the past that are accountable to the present, we do not seek to romanticize the past, but rather to encounter past lives as they were lived, as ever in the process of becoming and relational to the material and social worlds in which people lived. However, this must be combined with an aim to dismantle the systemic narratives that there is a ‘normal’ lifeway, and importantly to recontextualize our characterization of variance as synonymous with ‘deviant’. The aim must be to seek difference without othering (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2011; Reference Braidotti2013; Reference Braidotti2019; Lyons & Supernant Reference Lyons, Supernant, Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020). This is where we identify the potential of posthuman archaeologies to challenge us to find new ways of thinking about diversity in the past. Such narratives will not by themselves overturn the structural issues we face, but they do the small and necessary work of opening up new avenues of thought (Braidotti Reference Braidotti2019).

Specifically, for the nineteenth century, we see the posthumanist call to rethink difference as positive as particularly important, because the link between the standard ‘lifeway’ as white and middle-class is reflexive. Literature and culture from the period was instrumental in building modern societal structures, and replicating them in our narratives of the past works to reinforce the bias which is present in written accounts. It is necessary to view the diversity of experience not as variations from the ‘norm’, but as valid lifeways in their own right. It is necessary to work to dismantle the idea that those who do not meet middle-class ideals have in some way ‘fallen short’, in the same way that it is necessary to dismantle the idea that women ‘fall short’ by not being men. The study of the material culture of mourning in the nineteenth century is largely unique, as a set of objects related not only to women, but explicitly linked to a specific life event. Often material culture and behaviours related to women have been considered frivolous and unworthy of consideration, both in society and in research, and the archaeology of clothing and fashion is no exception. However, by beginning to dismantle our assumptions, we can begin to dismantle the masculine, class-based narratives which have defined our understanding of the period, and which continue to shape modern society.

Although separated by seven millennia, we find echoes of these cultural norms also structuring archaeological accounts of the Neolithic, resulting in the devaluing of women's tasks as the mundane chores of domestic life. In their place, we have hoped to offer routes to recasting first the differences between those biologically sexed as male and female, not as exclusive communities determined at birth, arranged as opposites, but as ever-changing emotional communities over the life course, in turn offering diverse entry points into the relational material assemblages that shaped world views. By contrasting grinding cereals, in which almost all female sexed bodies participated, and hide working, which may have allowed scope for prestige to be gathered, we have shown that women's work in the Neolithic was not mundane, nor necessarily uniform, offering scope for difference to be recognized. Charting how emotions may have flowed through assemblages of different materials and into the context of burial suggests connections and shared understandings rather than distinct hierarchies of norm and other. By adding time to these assemblages, we can see how over the lifecourse things were never stable as individuals aged and learnt crafts.

It is not our intention to imply that ‘emotional communities’ or emotional relationships are the preserve of women. Indeed, it is our contention that the investigation of the emotional connections and social relationships people build within their communities is an important, and often overlooked, area of analysis. If histories are partially constructed through mutual transfer of ideas and the creation of group expression, then these emotional communities, created through choice and shared experience, are vital to the investigation of how change through time is understood. For this reason, we contend that ‘emotional communities’ could, and should, be used to consider all aspects of identity, including masculine and mixed groups, queer spaces and communities bound together through their experiences. In this way, the study of emotional communities serves to break down monolithic categories such as ‘woman’ or ‘man’ into ‘these people, at this time, and in this place’. In this way, our argument is not that women relate in a uniquely emotional way with each other, but that men's emotional communities are often framed in terms of an activity, be that a Mesolithic hunting party or a nineteenth-century gentleman's club. Reframing these activities as a way of emotionally connecting with other men may offer a new perspective on masculine group identities, as well as deconstructing the myth that ‘men do and women feel’.

In proposing a focus on emotional communities in feminist accounts of the past, we are keen to emphasize that this would work to deconstruct previous focus on women in the domestic and familial sphere. Too often, accounts of women in the past have focused on women as ‘mothers’ or ‘wives’, but a focus on the emotional communities women built for themselves, outside the home, places the emphasis back on women's agency and the way they relate to each other. In recentring the focus on explicitly female social networks, we are reframing women's activities not in the way they work for men, but in the way they work for women themselves. In this way, the wearing of mourning clothes does not make a woman a clothes horse, displaying the family's status, but allows her to connect with other women in order to find support. The production of hide is not the development of economic worth for the family or for male status, but an activity some women share and gain prestige from, allowing them to create relationships and spaces beyond the familial sphere. In short, the consideration of the ‘emotional communities’ women were a part of recontextualizes their activities beyond the way they function to serve men, and highlights women's agency in their own lifeways and thus their role in history.

We conclude that, while posthumanist feminism guides us to the kinds of attention that should be paid to differences when they arise, considering emotional communities as a form of assemblage can help us to challenge the status quo of past narratives on identity as a classificatory tool by writing about where different bodies, materials and spaces came to shape people's experiences of themselves, and in this case, particularly sex and gender. Writing in 1997, Conkey and Gero argued that

the feminist vision has no fixed endpoint to be achieved by a standard set of rules. Feminist destinations are perhaps less important than the everyday pragmatic work of moving the feminist vision along; the dignity achieved in struggling for something worthwhile may be more important than any predetermined endpoint of a feminist world. (Conkey and Gero Reference Conkey and Gero1997, 431)

We wholly concur with this statement as one explicitly detailing the approach of the assemblage; by adding the concept of emotional communities, let us now explore difference as a positive place to begin narratives of the past.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the editors of the special edition for the invitation to speak in the session on which this publication is based and the comments during the writing of the paper. We are very grateful to the anonymous reviews and the journal editor for their comments, which helped us to improve the text and develop ideas further. All mistakes remain our own.