The Global Nutrition Report is an annual report that assesses progress in improving nutrition outcomes and identifies actions to accelerate progress and strengthen accountability in nutrition. It was called for at the Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit, held one year after the London Olympics in 2012 hosted by the Governments of Brazil and the UK. The call came on the basis that strong accountability gives all stakeholders more confidence that their actions will have an impact, that bottlenecks to progress will be identified and overcome, and that successes will spread inspiration. The Global Nutrition Report series is thus designed to be an intervention in the ongoing discourses in and governance of global nutrition.

The Global Nutrition Report 2015 ( 1 ) was published in September. It tracks progress towards two sets of global targets, both ratified by the world’s health ministers through the WHO. The first set – established in the WHO Comprehensive Implementation Plan on Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition (2012) – comprise global nutrition targets on six aspects of malnutrition among women, infants and young children. The second are a subset of the targets on non-communicable diseases (NCD) set in the WHO Global Monitoring Framework for the Prevention and Control of NCDs (2013).

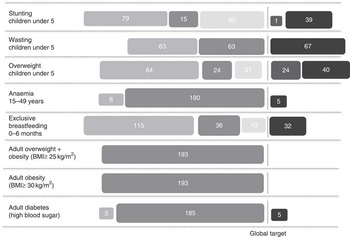

The Global Nutrition Report 2015 tracked eight indicators of progress towards these targets (Fig. 1). The good news is that there has been progress in reducing malnutrition in all its forms. Data on under-5 growth – stunting, wasting and overweight – reminds us of what can be achieved with the right focus, the right interventions and policies, and sustained commitment. Stunting shows particular progress: thirty-nine countries are now on course to meet the global target, up from twenty-four last year.

Fig. 1 Global dashboard on eight global nutrition targets: number of countries at various stages of progress against global targets on nutrition (![]() , missing data;

, missing data; ![]() , off course, little/no progress;

, off course, little/no progress; ![]() , off course, some progress;

, off course, some progress; ![]() , on course, at risk;

, on course, at risk; ![]() , on course)

, on course)

The bad news is that progress remains too slow and uneven. Progress in addressing anaemia among women is practically non-existent. The world is completely failing to meet the global target of halting the rise in the rates of adult obesity and diabetes. And while we want all countries to be on course to meet targets, at the moment there are far too many off course, with little or no progress – as well as far too much missing data.

Actions needed to accelerate progress

What do we need to do to build on and accelerate progress? Here are five areas of action identified by the Report.

1. Build the enabling political environment for malnutrition reduction

The evidence is clear that countries that have accelerated malnutrition quickly have done so within a strongly supportive political environment. For example, in Maharashtra, a large state in India, a State-wide Nutrition Mission was found to be an important contributor to that state’s dramatic declines in stunting between 2006 and 2012. In Peru, Presidential candidates were led to make public pledges for malnutrition reduction by a strong coalition of civil society. In Brazil, reductions in stunting are associated with the strong leadership and policies of the Lula government. But commitment is not enough. For a truly enabling environment, commitment has to be associated with a strong demand and pressure for action, investments in capacity to implement action and engagement across sectors to develop new action. We show in the Global Nutrition Report 2015 that measurement of such environments, while still in its infancy, is advancing rapidly with a suite of indicators such as the WHO Nutrition Landscape Information System, the Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index, Food Epi, the Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action and the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement.

At a global level, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) framework should be a key element of an enabling framework for nutrition. Despite evidence showing that improved nutrition is a driver of sustainable development, nutrition remains under-represented in the SDG. All of us need to advocate strongly for the set of SDG Nutrition Indicators proposed by the UN Standing Committee on Nutrition to be included in the indicator set put forward to the UN Statistical Commission by the end of 2015( 2 ).

2. Implement nutrition interventions and policies that reach the people who need them

The Global Nutrition Report 2015 tracks the (inadequate) data on implementation of a set of specific nutrition interventions( Reference Bhutta, Das and Rizvi 3 ). The extent of data (and presumably its quality) on whether these interventions are reaching people who need them varies widely – between interventions as well as between and within countries. We also show that while countries have made progress in implementing policies to encourage healthier eating, the vast majority are in high-income countries despite the growth of the burden of obesity and diabetes everywhere. This failure of implementation must change if we are to make progress. In particular, the identification of interventions and policies that can serve a ‘double duty’ in addressing undernutrition as well as overweight, obesity and nutrition-related NCD is urgent.

3. Allocate more funding to nutrition

New estimates from fourteen countries show that on average 1·32 % of total government budgets are allocated to nutrition. While donor disbursements on nutrition-specific interventions nearly doubled between 2012 and 2013 – from $US 0·56 billion to $US 0·94 billion – only sixteen of the twenty-nine members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported nutrition-specific spending greater than $US 1 million in 2013. New analysis highlighted in the Report concludes that governments should – at a minimum – double the share of their budgets allocated to improving nutrition. Donor spending on nutrition will also need to more than double.

4. Engage new partners in the fight against malnutrition in all its forms

To speed up improvements in nutrition, we need to widen the number of sectors that recognize their stake in reducing malnutrition and then act on this realization. In the Global Nutrition Report 2015 we highlight two areas that have not received as much attention as they should: climate change and food systems. We show the synergies between addressing climate change and improving nutrition; we show that countries can develop indicators to track how nutrition-friendly their food systems are. To help leverage these synergies we call on the climate change and nutrition communities to form alliances to meet common goals, and for the emerging number of global food systems initiatives to develop clear indicators of the impact of food systems on nutrition and health outcomes.

5. Strengthen accountability in nutrition

In the Global Nutrition Report 2015 we track the commitments made by the international UN agencies, governments and business at the N4G Summit in 2013. We found that 44 % of N4G commitments are ‘on course’ in 2015, compared with 42 % in 2014. Yet we could not assess 46 % of commitments because they were vague or we received vague responses. This is a clear indicator that for stronger accountability we need SMART-er (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic and time-bound) commitments to nutrition.

Businesses also have to become more accountable for nutrition. Like other actors, businesses make choices that may lead to both positive and negative outcomes for nutrition. Greater accountability would help increase the former and minimize the latter. In the Global Nutrition Report 2015 we discuss how that can happen: stronger leadership to bring all parties to the table to discuss roles and responsibilities; greater transparency of actions by businesses; a dedicated research programme to provide a more robust evidence base about the influence of businesses on nutrition; and stronger government frameworks for regulating businesses. At the global level we call on the four large UN agencies most concerned with nutrition – FAO, UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP) and WHO – together with other relevant international bodies, to establish an inclusive, time-bound commission to clarify the roles and responsibilities of business in nutrition.

Finally, data. Data are the currency of accountability. While some data areas – such as data on nutrition budget allocations – have strengthened considerably since 2014, the data gaps in nutrition remain large. Only seventy-four of 193 countries have sufficient data to be able to assess their progress on five global maternal and child nutrition targets (listed in the first five rows of Fig. 1). It is thus essential for countries, donors and agencies to work with the technical nutrition community (including the readership of this journal) to identify and prioritize the data gaps that are holding back action and then invest in the capacity to fill the gaps.

Significant reductions in malnutrition – in all its forms – are possible by 2030

Countries that are determined to make rapid advances in malnutrition reduction can do so. The Global Nutrition Report 2015 provides the detail on signposts to the many policy, programme and investment opportunities available to make these rapid advances, as well as numerous examples of countries that have surprised the world with the progress they have made.

It also makes it clear that the public health nutrition research community has an important role to play. Public Health Nutrition has proved forward-looking in its focus on all forms of malnutrition; readers of this journal are exposed to analysis of stunting, anaemia, obesity, etc. on a regular basis. But this inclusive approach is quite rare: the undernutrition and obesity/overweight and NCD community remain pretty siloed. A key contribution that public health nutrition research can make is to talk more and collaborate more – and for journals to publish the results. One key area the Global Nutrition Report 2015 identifies is for researchers from the different communities to come together to assess the evidence of what kinds of ‘double duty’ actions can help address different forms of malnutrition at once. We also need more joint research on the political and institutional environment that can help advance nutrition; our analysis of research on this conducted by the undernutrition and obesity communities separately reveals real similarities( Reference Gillespie, Haddad and Mannar 4 , Reference Huang, Cawley and Ashe 5 ). Researchers have real potential to learn from each other: more engagement would make a real difference to our ability to address these complex and multiple faces of nutrition in a more efficient and effective way.

An enormous amount has been accomplished since the London N4G Summit in 2013. We should be proud of these accomplishments. But they are not enough. At the follow-up N4G Summit – in Rio de Janeiro in August 2016 – governments, businesses, civil society groups, foundations, multilateral agencies and concerned citizens need to announce new commitments. These commitments must be SMART and breathtakingly ambitious; those experiencing malnutrition do not need fuzzy or timid commitments. Almost one in three of us who share this planet today are experiencing malnutrition. The pledges should be for nothing less than to achieve what is called for in the new SDG: to end malnutrition in all its forms.