I Introduction

This chapter presents analyses using information from a variety of sources in order to identify areas where in-depth research can identify institutional challenges that are most critical to Bangladesh’s economic development. Two approaches are employed. The first approach uses a variety of institutional measures available in international databases to examine how a country, in this case Bangladesh, differs from a set of comparators. A questionnaire survey of various types of decision makers and academics is used in the second approach, as well as a set of open-ended interviews with senior policymakers and decision makers.

II Bangladesh’s Position in the Global Ranking of Institutional Indices

Since the pioneering work of North (Reference North1990), there has been widespread agreement that institutions matter for development. Narratives have described some features of the relationship between institutions and development and theoretical models of that relationship have been proposed that fit some stylised facts, often drawn from history. Numerous authors could be cited, but Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012), Khan (Reference Khan, Noman, Botchwey, Stein and Stiglitz2012a, Reference Khan2018), or more recently Pritchett et al. (Reference Pritchett, Sen, Werker, Pritchett, Sen and Werker2018) are prominent examples of the first approach, while Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2008) are a good example of the second. Going beyond this approach and getting into more detail on the nature and the quality of institutions requires the availability of qualitative or quantitative indicators describing them. Such country-level indicators and indices have been developed over the last two or three decades, which has given rise to an empirical cross-country literature exploring the relationship between institutions (as described by some of these indicators) and particular characteristic of economic development (primarily the level and growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP)). Knack and Keefer (Reference Knack and Keefer1995), Acemoglu et al. (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001), and Rodrik et al. (Reference Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi2004) were the first notable attempts in this direction.

While relying on the same type of data, that is the existing databases of institution-oriented indicators, the objective of this exercise is somewhat different. Focusing on a single country, Bangladesh, its main objective is to characterise its institutional profile as reflected in available indicators and to see what its absolute and relative strengths and weaknesses are. This will be done in three ways. First, relying on the most complete repository of indicators, the University of Gothenburg’s Quality of Government database (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Holmberg, Rothstein, Alvarado Pachon and Axelsson2020), six aggregate indicators will be defined, and countries, both advanced and developing, will be ranked according to each of them. The quality of Bangladeshi institutions will then be analysed according to each aggregate indicator taking into account each of the individual indicators that make up that aggregate indicator. Because all of these indicators are closely related to economic development, as measured for instance by GDP per capita, the second question that will be asked is how far away Bangladesh is from what could be considered an international norm: that is, the level of each aggregate indicator that corresponds to Bangladesh’s level of GDP per capita. To some extent, this is equivalent to comparing Bangladesh to countries with more or less the same level of income. The same comparison will be made with geographical neighbours or countries that have outperformed Bangladesh over the last two or three decades, despite being initially at the same level of development. Finally, the time evolution of the institutional quality of Bangladesh will be analysed by relying on a database that makes it possible to cover the last three decades.

Analysing the various findings, Bangladesh’s institutional profile as indicated by institutional indicators will be summarised in Section IV. The general diagnostic is that Bangladesh ranks uniformly rather badly in many institutional dimensions. Given its high-growth performance, the so-called ‘Bangladesh paradox’ or ‘Bangladesh surprise’ of this combination of under-performing institutions and over-performing economy underlined by several observers (World Bank, 2007b, 2007c, 2010; Mahmud et al., Reference Mahmud, Ahmed and Mahajan2008; Asadullah et al., Reference Asadullah, Savoia and Mahmud2014) is worth serious investigation. It should be kept in mind, however, that the institutional part of this paradox relies on indicators that are essentially imprecise and that can only give a rough description of the nature of institutions in a given country.

A Constructing Synthetic Institutional Indices

There now are many databases with sets of indicators that seek to describe the quality of various aspects of a country’s political, sociological, and economic institutions. Well-known databases of this type include the Worldwide Governance Indicators, the Logistics Performance Index, Doing Business, the Global Competitiveness Index, and the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), or Polity IV. Several single indicators have also become a key reference, for instance the Transparency International corruption index. The Quality of Government is a repository of institutional indicators present in all these databases. As such, it comprises more than 2,000 indicators over a period that extends from 1949 to 2018 for some indicators and some countries. However, it would not make sense to use every indicator to study the profile of one specific country in comparison to others. Moreover, there are many missing observations. Instead, the technique used here has been to develop a small number of synthetic institutional indices that aggregate individual indicators in the database with similar distributions across countries at a given point of time – the year 2016. A method of clustering a subset of indicators simultaneously available for the largest number of countries into a pre-determined number of groups – that is clusters – was used. The data selection procedure ended up with a set 97 indicators available in 105 countries – both developed and developing. The clustering method is based on the correlation across indicators in the cluster using the country values of indicators as observations. It thus consists of minimising the variance across indicators within clusters and maximising the variance between clusters. A synthetic index is then associated with the cluster by using a linear combination of all indicators in the cluster. The coefficients of the first axis in a principal component analysis (PCA) of all indicators in the cluster were used. They thus maximise the cross-country variance explained by the synthetic index.

The main parameter in the hands of someone using clustering methods is the number of clusters. In the present case, it was decided to stay with six clusters, and thus six synthetic indices, for both practical reasons and to ensure consistency. The practicality requirement refers to the need to be able to visualise and compare observations across a multidimensional space, which requires minimising the number of clusters. Consistency requires differentiating as much as possible the synthetic indices, while making it possible to give some clear indication of their meaning. Indeed, each cluster may include very different indicators, without an obvious common link between them, although the fact that they are correlated suggests that such a link must exist. However, it turns out that if the number of clusters is increased, it makes it increasingly difficult to identify such a link. In the present case, it also turned out that the six synthetic indices were in rough agreement with the main themes of the institutional diagnostic survey undertaken in this research project, the results of which are analysed in the next section.

The six clusters or groups of indicators that are selected by the procedure just described are Democracy, Rule of law, Business environment, Bureaucracy, Land, and Human rights. Number of indicators used by the synthetic indices of Democracy, Rule of law, Business environment, Bureaucracy, Land, and Human rights are 22, 14, 23, 9, 8, and 11, respectively. Furthermore, the variance captured by the first principal component within the group of each synthetic index of Democracy, Rule of law, Business environment, Bureaucracy, Land, and Human rights are 57.21%, 73.46%, 68.47%, 79.30%, 38.72%, and 54.84%, respectively.

Under the heading democracy are found indicators describing the political regime, its effectiveness, pluralism, stability, or transparency. The rule of law heading comprises indicators describing the effectiveness of the legal framework, the judiciary system, the control of corruption, and the quality of economic regulation. Business environment, not surprisingly, includes the quality of business infrastructure and the market context in which firms operate. Bureaucracy describes the quality of the administration and some public services. Land does not cover many indicators because it turns out to be more focused than other synthetic indices. Finally, human rights comprise indicators of a more social nature, that is education, healthcare, and civil liberties, including freedom of expression.

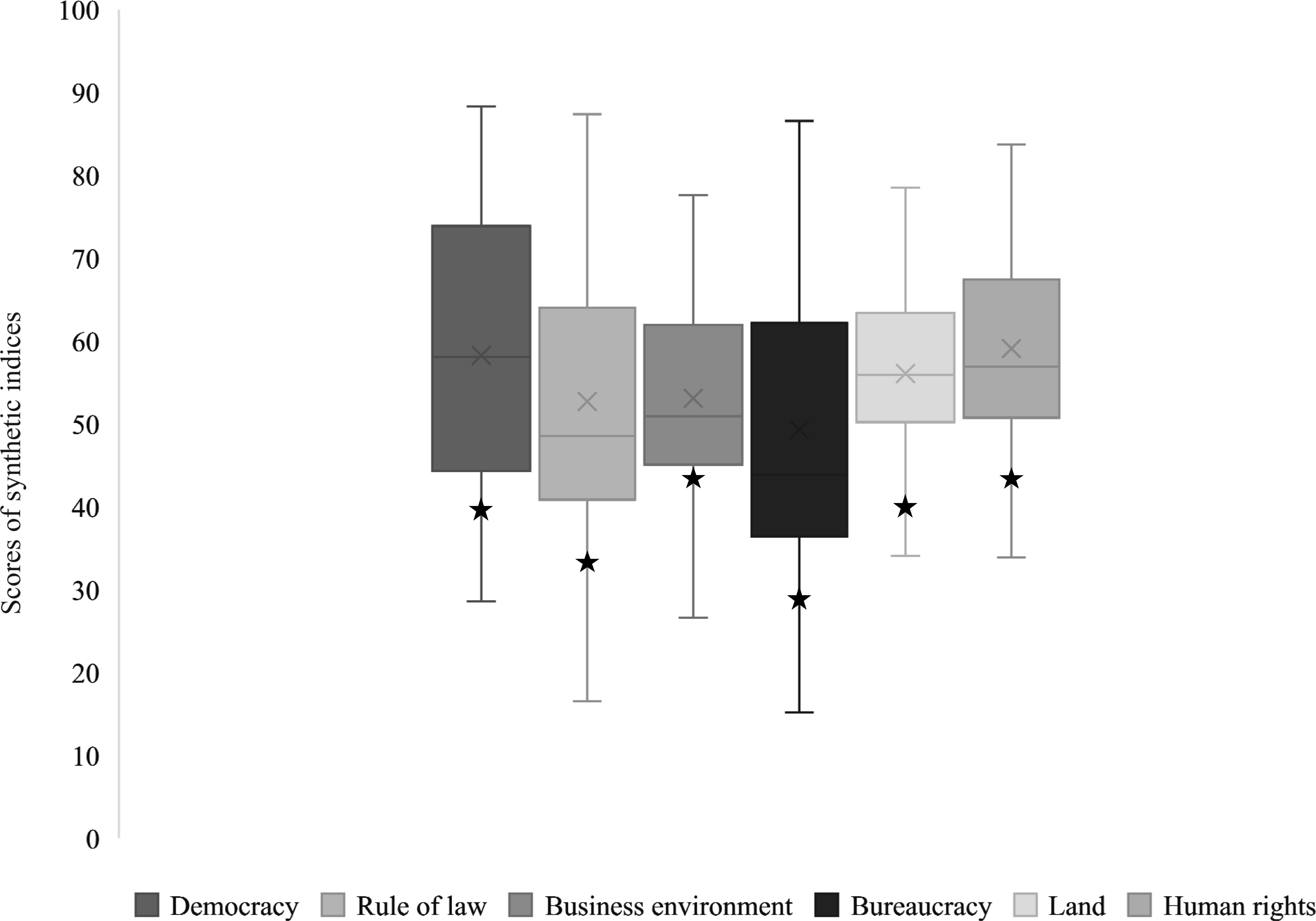

Each individual indicator was linearly normalised for its value to range between 0 and 100, but of course their distribution across countries, including their mean and median, is not the same. It appears that the mean and median of the democracy, land, and human right indices are above those of rule of law, bureaucratic quality, and business environment. To the extent that the value of individual indicators is not necessarily comparable among themselves, this result is not of major importance for our purposes. Instead, we now focus on the relative position of Bangladesh across the six-dimensional space of the synthetic indices.

B How Does Bangladesh Compare to Other Countries According to the Synthetic Institutional Indices?

This section summarises Bangladesh’s relative position in the synthetic institutional indices compared to the top and bottom performing countries of the world. According to Figure 3.1, Bangladesh’s relative performance in the global ranking, established on the basis of the synthetic institutional indices, is rather uniformly mediocre, as it systematically ranges in the lowest quartile – as a matter of fact, even in the lowest quintile of the global ranking. The situation is even worse for the rule of law, bureaucratic quality, and land synthetic indices, where Bangladesh ranks in the bottom 5% or close to it. Its position on human rights is only slightly less disastrous, as it still lies at the upper limit of the bottom 10%. In short, it is only on democracy and business environment that Bangladesh gets somewhat away from the very bottom of the global ranking. This is an interesting finding since it allows us to differentiate the relative quality of Bangladeshi institutions with respect the nature of these institutions. It will be shown later that this conclusion resonates rather well with other evidence or judgements about Bangladeshi institutions.

Figure 3.1 Distribution of the synthetic indices.

Note: The star indicates Bangladesh’s position. For each synthetic index, the figure shows the limits of the four quartiles of its distribution among countries, the bottom and top whiskers corresponding to the bottom and top quartiles, and the horizontal segment within the central box, the median, separating the second and third quartiles.

Table 3.1 shows the countries that are ranked close to Bangladesh in the various synthetic indices, the idea being to see whether they share some common features besides their institutional ranking. Diversity is clearly the dominant factor here. There is little regional alignment, except the presence of Pakistan in democracy and land, something that can be linked to the common past with Bangladesh, first as British colonies and then as two parts of the same political entity. Several Middle Eastern and North African countries appear in the list, with no obvious geographical, historical, or political similarity with Bangladesh. Finally, many low-income sub-Saharan countries are present, but this may perhaps reflect more the relatively large number of countries in that region of the world, their low income, and their absence of efficient institutions.

Table 3.1 Ranking of the countries around Bangladesh for each summary index in 2016

| Democracy | Rule of law | Business environment | Bureaucracy | Land | Human rights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 84 | Kuwait | 98 | Zimbabwe | 82 | Zambia | 94 | Argentina | 99 | Haiti | 93 | Zimbabwe |

| 85 | Jordan | 99 | Ukraine | 83 | Senegal | 95 | Lebanon | 100 | Algeria | 94 | Liberia |

| 86 | Nigeria | 100 | Madagascar | 84 | Jamaica | 96 | Dominican Republic | 101 | Madagascar | 95 | Tanzania |

| 87 | Bangladesh | 101 | Bangladesh | 85 | Bangladesh | 97 | Bangladesh | 102 | Bangladesh | 96 | Bangladesh |

| 88 | Pakistan | 102 | Myanmar | 86 | Guyana | 98 | Zimbabwe | 103 | Guinea | 97 | Algeria |

| 89 | Lebanon | 103 | Haiti | 87 | Iran | 99 | Madagascar | 104 | Nigeria | 98 | Egypt |

| 90 | Algeria | 104 | Guinea | 89 | Paraguay | 100 | Guinea | 105 | Pakistan | 99 | Venezuela |

Note: This ranking is performed for 105 countries.

The most striking feature of Table 3.1 is the absence of countries with a growth record as strong as Bangladesh’s over the last few decades: on the contrary, several countries show rather inferior performance. Likewise, only one country (i.e. Thailand) would qualify as a manufacturing exporter (like Bangladesh). All other countries are typical commodity exporters, except Jordan and Lebanon, and four of them are major oil exporters – Algeria, Nigeria, Kuwait, and Iran. These observations reinforce the idea that there is a ‘Bangladesh paradox’: a fast-growing manufacturing exporter with institutional quality comparable with slow-growing commodity exporters, including oil exporters. It will be seen later in this study that the latter analogy echoes the fact that ready-made goods (RMG) manufacturing exports in Bangladesh may indeed play a role in the economy and the society similar to that played by raw commodity exports in other developing countries.

C Major Institutional Weaknesses of Bangladesh in the Synthetic Institutional Indices

Box 3.1 shows those individual indicators in each synthetic cluster on which Bangladesh performs substantially less well compared to the others, that is the mean of the cluster. For instance, in democracy it performs particularly poorly on the following indicators: the presence of ‘fractionalised elites’, the lack of ‘public trust in politicians’, and the strength of the ‘political competition’. Likewise, in the rule of the law, it can be seen that the ‘corruption perception index’ plays an important role in bringing Bangladesh’s overall score down, the same being true of the overall evaluation of the ‘judicial independence’ and the ‘inefficiency of the legal framework’.

Box 3.1 Major areas of weaknesses in each synthetic institutional index

1. Democracy: Political stability; Government effectiveness; Public trust in politicians; Transparency of government policymaking; Factionalised elites; State fragility; Political pressures and controls on media content; Political competition

2. Rule of law: Efficiency of legal framework in challenging regulations; Efficiency of legal framework in settling disputes; Judicial independence; Strength of auditing and reporting standards; Corruption perception

3. Business environment: The efficiency of the clearance process by border control agencies, including customs; Quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure; Competence and quality of logistics services; Ability to track and trace consignments; Taxation on investment; Financial market development; Labour market efficiency; Production process sophistication; University–industry collaboration in R&D; Capacity for innovation; Company spending on R&D; Venture capital availability; Intellectual property protection

4. Bureaucracy: Public services; Favouritism in decisions of government officials; Irregular payments and bribes; Wastefulness of government spending

5. Land: Land administration and management; Registering property

6. Human rights: Voice and accountability; Freedom of expression; Protection of minority investors’ rights; Ethical behaviour of firms

Given the clustering procedure that was applied in defining the synthetic institution indices, it may be the case that some individual indicators do not fit the label attributed to the cluster very well. For instance, in business environment, some indicators refer more to the behaviour of firms, like ‘spending on research and development (R&D)’ or ‘production sophistication’ than their environment, although particularly negative indicators there include ‘customs’, ‘infrastructure’, and ‘lack of competition’. In the same way, it might be considered that ‘irregular payments and bribes’ would belong more to the rule of the law than bureaucratic quality – but the fact that it appears in the latter cluster clearly shows that this infringement of the rule of the law is closely linked to unsatisfactory ‘public services’ and ‘favouritism by government officials’, and therefore to an under-performing bureaucracy.

Box 3.1 could also have shown the individual indicators with scores above the mean of the synthetic indicator. It is worth stressing that, the low government militarisation index and the ‘autonomy’ of the government do not do as badly as other indicators. However, they do not necessarily do well either. Transparency or press freedom may be above the mean score of ‘democracy’, but that score is low, and those indicators are simply less low in the global ranking. Yet it may be worth keeping this kind of nuance in mind.

Another interesting point is the relative lack of consistency of various sources on the same topic. For instance, ‘rule of law’ as evaluated by Freedom HouseFootnote 1 is above the mean in the synthetic rule of law index, whereas ‘rule of law’ as evaluated by the Quality of GovernmentFootnote 2 falls below the mean. Clearly, this kind of discrepancy shows the unavoidable imprecision of these individual estimators – sometimes themselves based on several sources – and underlines the need to be cautious in interpreting these results.

Is Bangladesh an outlier in the institution–development nexus? The preceding comparisons of Bangladesh with other countries were based on ad hoc criteria, whereas the analysis of its global ranking is biased because of the presence of so many countries at higher level of development. A relevant comparison may be to match Bangladesh with countries at similar levels of development and to see whether it does so badly, and in what dimension of the synthetic institutional indices. To do this, a simple approach consists of running a regression of the various institutional indices on a development index of the countries and to test whether Bangladesh is an outlier on the negative side, that is exhibiting a negative gap greater than 2 standard deviations, as usually defined in econometric work. Two definitions of the level of development have been used: GDP per capita – measures in international 2011 dollars – and the Human Development Index (HDI), used by the United Nations, which comprises not only GDP per capita after normalisation but also measures of education and health. To avoid this procedure having to depend too much on the relationship between institutions among advanced countries, or on the difference between developing and advanced countries, the estimation is performed on developing countries only.

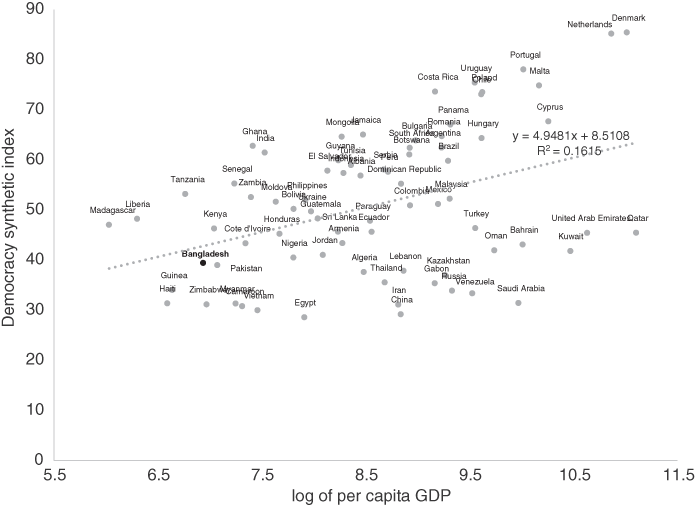

Figure 3.2 shows the scatter plot of the democracy synthetic index against the log of GDP per capita for developing and emerging countries, with a trend line that represents the predicted value of the democracy synthetic index on the basis of GDP per capita. It can be seen that Bangladesh lies below the line, which means that, conditionally on its level of GDP per capita, Bangladesh underperforms on that index. Yet the gap with respect to the trend line is not sizeable, which means that Bangladesh cannot be considered an outlier in comparison with other observations. In other words, there is nothing exceptional in such a deviation from the trend line. This would not be true, however, of China, Iran, or Egypt, because their gap with respect to the trend line is larger than twice the standard deviation of that gap among all observations.

Figure 3.2 Scatter plot of the democracy synthetic index against (log) GDP per capita.

Note: Democracy synthetic index as a function of (log) GDP per capita (2011 US$).

Table 3.2 summarises the results obtained for the six synthetic indices using GDP per capita or the HDI as normalising device. Because the deviation of Bangladesh from the norm never exceeds 2 standard deviations, it cannot be said that Bangladesh is an outlier in any institutional dimension. What is striking, however, is that, conditionally on its level of development, Bangladesh always underperforms. In other words, it cannot be said that Bangladesh’s bad position in the global institutional ranking shown in Table 3.1 is due to its level of development, as measured by GDP per capita or the HDI. Even controlling for this – that is, even comparing it with countries at a comparable level of development – Bangladesh is under-performing. This is true for all institutional indices except one, business environment, for which Bangladesh is slightly above the norm. Indeed, it was on this index that it reached the highest position in the global ranking discussed earlier.

Table 3.2 Normalised deviation of Bangladesh from predicted synthetic indices based on GDP per capita and Human Development Index

| Democracy | Rule of law | Business environment | Bureaucracy | Land | Human rights | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deviation from GDP norm | –0.44 | –0.82 | 0.24 | –0.72 | –1.19 | –0.74 |

| Deviation from HDI norm | –0.53 | –0.93 | 0.04 | –0.84 | –1.43 | –0.91 |

Note: GDP (HDI) norm = predicted value of the regression of synthetic indices on log GDP per capita (HDI).

Deviations are standardised by standard deviation of residuals.

D What Have We Learnt from the Cross-Country Comparison?

Bangladesh has gone through several phases of crisis in the past. Despite numerous challenges, most indicators describing the institutional environment and the political and socio-economic conditions have significantly improved over the last three decades, very much in line with the stabilisation of the political scene since the mid-2000s. The overall socio-economic condition has improved. Even an indicator like control of corruption is still gradually improving today.

The situation looks less positive when comparisons are made between the current institutional context in Bangladesh and that in other countries, even when the comparison is restricted to developing countries. The synthetic institutional indices, based on a large number of individual indicators available in databases on governance and the quality of institutions, paint a broad picture of Bangladesh’s institutional context that is not positive. Bangladesh is found to be in the bottom 20% of global rankings based on these indices and, in some institutional dimensions, even in the bottom 10%. As a matter of fact, despite its development achievement over the last two decades, Bangladesh is even outperformed on all institutional dimensions by several developing countries, including poorer countries.

This outperforming is not uniform, and much can be learned for an institutional diagnostic from disparities across the various institutional indices. Bangladesh appears as particularly weak in areas like bureaucratic quality, rule of law, land issues, and, to a lesser extent, human rights. However, the situation is noticeably better, though still far from outstanding, when considering the democratic functioning of the country and the business environment it offers. It is interesting that these relative institutional strengths relate to two key features of Bangladesh’s development over the last 20 years or so: the relatively stabilisation and pacification of the political game and the surge of manufacturing exports in the RMG sector.

This kind of ranking must nevertheless be treated with caution. On the one hand, Bangladesh does not appear as an outlier when the ranking is made conditional on the level of development of a country. It is still the case that it often underperforms other countries in several areas, though mostly by a narrow margin. It does better with respect to the business environment. On the other hand, it must be kept in mind that individual indicators of governance and institutional quality are necessarily rough and may miss important details that might change the overall judgement to which they lead. Relying only on them to establish a diagnostic would thus be extremely restrictive. Hence the alternative approach of surveying different types of decision makers on their perceptions of the institutional strengths and weaknesses in the context in which they operate, as is discussed in Section III.

III The Country Institutional Survey (CIS) in Bangladesh

Although many thinkers throughout history have thought of societies as organisms with some similarity to the human body, simple diagnostic tools of the kind that are available to detect human diseases do not exist for societies and the institutions that govern them, even when the investigation is restricted to what may weaken their economic development. Economic development per se, and its relationship with institutions, are such complex topics that only in-depth analyses can possibly shed some light on them. Even the ‘growth diagnostic’ tool proposed by Hausmann et al. (Reference Hausmann, Rodrik, Velasco, Serra and Stiglitz2008) identifies ‘binding constraints’ on growth that are contingent upon the ‘economic and institutional environment’ of a country and does not say much about the institutional roots of these constraints. This was very much the approach followed in Chapter 2. Yet the complexity of the relationship between institutions and development should not prevent an analysis from relying on simple diagnostic tools, provided that the limitations of these tools is kept well in mind when trying to go deeper in an institutional diagnostic exercise. Simple tools can help us find the way to search for the bigger picture. This was done in the preceding section by trying to extract information from existing cross-country indicators of the quality of governance and institutions. Another simple tool is reported on in the present section: the survey responses of decision makers of various types who were asked about the institutional features that hinder Bangladesh’s development.

Two approaches were followed in this survey. The first was a questionnaire survey that was administered among a selected sample of people who regularly confront Bangladesh’s institutional context in their activities. This survey was copied from the CIS, which has been used in other countriesFootnote 3. The second approach consisted of conducting open-ended interviews with a few key informants in political, business, social, and academic circles.

A The Survey: Background and Design of the Questionnaire

The CIS is a sample survey tool developed as part of the institutional diagnostic activity of the Economic Development and Institutions (EDI) programme. Its aim is to identify institutional challenges as they are perceived by the people in a country who are most likely to confront them on a regular basis. These challenges are then made the subject of deeper scholarly analysis. Being based on a broad sample of respondents, the CIS intends to yield a more diverse view of the country than the numerous institutional indicators that rely most often on the opinion of a few experts.

At the beginning, a pilot for the CIS in Bangladesh was held in late 2018. Those who took part in the pilot occupied top decision-making positions at this time. The reason for choosing respondents from top decision-making positions was to get a lucid idea of the institutions in Bangladesh, since such respondents either interact with the institutions on a regular basis or they work as an active part of the institutions. As decision makers, they have in-depth knowledge of institutions and their weaknesses. Of course, these opinions are quite different than the opinions of the general mass of the people, as they are based on direct experiences with the institutions and/or rigorous analysis of the institutions from their vantage point. The insights gathered from the pilot helped conducting the Bangladesh CIS between December 2018 and February 2019. The remainder of this section will discuss the design of the questionnaire and the execution of the survey, respectively.

The questionnaire had three primary components: a section on the personal characteristics of the respondent; another on the institutional areas seen as most constraining by the respondent; and the last one, a long section on the respondent’s perceptions of the institutions and the functioning of institutions in Bangladesh.

The first section was split into two parts. The first part initiated the discussion and asked general questions such as the respondent’s name, gender, and sector of affiliation, including political affinity and sub-sectors that the respondent was associated with. The other part compiled more sensitive information on the past and present occupation of the respondent, the location of their work, their family size, and their religion.

The second section of the questionnaire was composed in such a way as to gather information about the most constraining institutional areas in Bangladesh. In this part of the questionnaire, the respondents were provided with the details of institutional areas that we had focused on for the survey. This comprised seven broad institutional areas: ‘Political institutions – executive’; ‘Political institutions – system’; ‘Justice and regulations’; ‘Business environment’; ‘Civil service’; ‘Land’; and ‘People’ (Box 3.2). Respondents then had to select two institutional areas that, according to them, most constrain development in Bangladesh. The chosen areas were not only important for the analysis but were also important for the subsequent part of the survey since they determined the set of questions presented to the respondent in the third section of the survey.

Box 3.2 Institutional areas and description

1. Political institutions – executive: Effective concentration and use of power; type of governance; relationship with parliament, judiciary, local governments, media, and civil society

2. Political institutions – system: Functioning of elections; voice of opposition parties, civil society, and media; checks and balances on the executive

3. Justice and regulations: Fairness, independence, and effectiveness of the judicial system; regulation of public and private monopolies

4. Business environment: Relationship between the private sector and public administration; protection of property rights and labour contracts; business registration and licensing; taxation; availability of infrastructure

5. Civil service: Efficiency, fairness, effectiveness, and transparency in the management of social and economic policy, including customs, taxation, education, health, etc.

6. Land: Provision of ownership, protection of tenants and small holdings, promotion of commercial ventures

7. People: Sense of solidarity, discrimination practices, security, trade unions

The core section of the CIS comprised 415 unique questions on the perception of institutions in Bangladesh. The collection of information relied on a Likert scale, ranging from ‘not at all’ and ‘little’ to ‘moderately so’, ‘much’, and ‘very much’. Responses were then converted into discrete numbers, ranging from one to five, for the analysis. The CIS questionnaire was unique in several dimensions, mostly with the aim of making it as close as possible to the specific context of Bangladesh.

There are particular challenges that come with surveying top-tier executives, not only with access but also because their time may be limited. Our survey had a high volume of questions and sought to gather information on a broad spectrum of institutional issues. If we had asked every respondent every question, the survey would be far too long to be of practical use. Keeping these constraints in mind, the survey was conducted in a dynamic way. As mentioned earlier, in the second section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to identify the most constraining institutional areas according to them, from the list of seven broad institutional areas. Then they were first asked to answer both the primary and secondary questions related to the two institutional areas they had selected, as well as only primary questions related to the other five institutional areas that they did not choose. Notice also that, given the overlap between institutional areas, respondents had to answer about 70–80% of the full set of questions on average.

Changes in institutions are infrequent and most happen over the course of time rather than suddenly and abruptly. Even though there are a few examples of institutional changes which have happened overnight, most institutions persist. At the same time, human psychology works in such a way that people tend to react to the most recent events associated with a certain entity. For that reason, it is quite possible that the perceptions of the respondents were biased towards the present. However, the current de jure institutional authority in Bangladesh has not changed much over the last decade and so it was expected that perceptions about the overall context would be reflected in their responses. In addition, in-depth discussions with top decision makers on the institutional constraints shed light on the changes over time. Second, the enumeration took place right around the time when a general election was taking place in Bangladesh. The election thus had impacts at several levels, in terms of survey responses that commented specifically on recent institutional characteristics. Last but not least, very recent changes in institutions do not explain the past economic trajectory, so the questions about the more stable aspects of institutions were relevant.

The survey covered the views of people who were either affiliated with institutions or in close contact with them. The survey also aimed to capture the view from the top down, where decisions are made or where policies are generated. To do this, it was very important to select respondents from the first- or second-tier position of any institution. These decision makers had experienced the impacts of changes in certain institutions first-hand and were concerned about the functioning of the country’s institutions. As a consequence, a pure random sampling in the overall population was not an option. The selection of respondents had to be based on an arbitrary stratification of groups of expert respondents, to make sure various sectors, occupations, and individual profiles would be present in the sample. This implies a strong selection bias with respect to the Bangladesh population, but, of course, this was deliberate.

B Execution of the Survey

The Bangladesh CIS was conducted between December 2018 and February 2019 in a collaborative effort between EDI researchers, Oxford Policy Management (OPM), and South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM), a think-tank from Bangladesh. A total of 355 individuals were sampled in a purposively stratified sample. The selection process followed two steps. First, researchers listed strata in terms of occupation, position level, geographical constraints, and tentative gender balance. Samples were surveyed in major cities in the country, like Dhaka, Gazipur, Chattogram, Sylhet, Rajshahi, Bogra, Rangpur, Barisal, and Khulna.

SANEM, in cooperation with OPM, determined a list of target respondents who satisfied the occupational, geographical, and gender considerations. Next, these probable respondents were contacted, and if they gave their consent they were interviewed. The sample is divided into five sectors: politicians, bureaucrats, business executives, academics, and civil society members. The respondents included politicians from ruling party and opposition; current and ex bureaucrats; business executives from agriculture, fishing, livestock, manufacturing, construction, Information & communication, wholesale and retail, health, transport, bank; academics from teaching and research professions; and people from non-governmental organisation (NGO). Responses of a total of 48 politicians, 51 bureaucrats, 131 business executives, 76 academics, and 49 civil society members were collected.

Table 3.3 provides details regarding the characteristics of the survey respondents. It is most unfortunate that, though the initial target was for at least 31% of the sample to be female, the enumerators struggled to contact or arrange interviews with female respondents. This may be linked to the fact that in Bangladesh, only a few of the top-tier positions are held by women. This in fact was observed to be the case when conducting the survey and can be considered a finding of the study. Thus, only 14% of the respondents were female.

Table 3.3 Composition of the sample

| Respondent’s main characteristics | Occupation history (number of respondents) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of female respondents | 50 | Politician | 48 |

| Number of respondents: Married | 324 | Bureaucrat | 51 |

| Average family size | 4.15 | Business executive | 131 |

| Average age in years | 47 | Academic | 76 |

| Average education: university degree or above | 318 | Civil society | 49 |

| Average years of experience | 21 | Total number of respondents | 355 |

| Average years of experience at the current institution | 15 | ||

The main goal of the CIS in Bangladesh was to capture an amalgamation of viewpoints about the institutions in the country. As mentioned earlier, the survey targeted respondents from the top tier; thus, the mean level of education for these respondents was well above the national average. As we can see in Table 3.3, about 90% of the respondents had a university degree or above. The same argument regarding choosing respondents from the top tier applies to the age distribution of the respondents. Since it takes years of experience to reach a top-tier position, respondents tended to come from older age brackets. The average years of experience of the respondents explains the spectrum of their experiences with institutions in the country, and it also indicates the way in which the survey captures the respondents’ perceptions of institutions in a dynamic way: as most of them had worked under varied circumstances, each of them had a unique experience with the institutions in Bangladesh which the survey intends to capture.

It is also important to point out that 23 respondents declared a political affinity with the ruling party and 25 with the opposition, and the rest of the respondents declared no political affinity. This enables us to compare the responses of respondents with ruling party or opposition affiliation with respondents without any declared political affinity, to assess whether party affiliation had any bearing on the responses given. In terms of geographical diversity, most respondents lived in an urban area. It is in fact not surprising to see that most of the respondents resided in urban centres, as the survey targeted the elite in the country, who tend to live in or close to the cities. Since most head offices or main branches of public and private organisations in Bangladesh are located in Dhaka, the region around the capital is overrepresented.

C Results of the CIS in Bangladesh

1 Critical Institutional Areas for Bangladesh’s Development

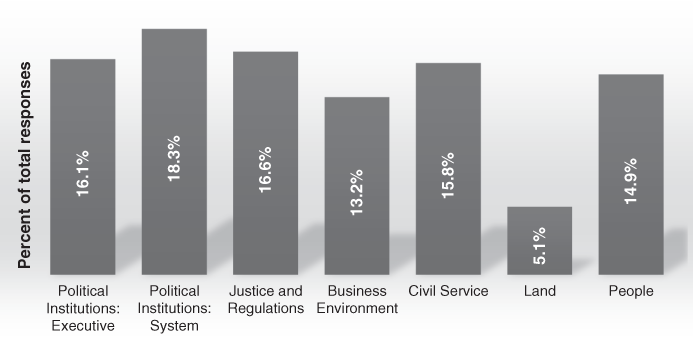

According to the respondents, the major constraining institutional areas for the development of Bangladesh are the political institutions and public administration. The ranking of these two areas depends on the measure chosen to aggregate individual opinions. However, it can be seen in Figure 3.3 that they are very close to each other in number of occurrences chosen by respondents. Notice also that, conditionally on being chosen, political institutions were selected by the respondents. Justice- and regulation-related institutions come in third position in the ranking of the most critical institutional areas for development in Bangladesh. On the other side of the spectrum, only 5.1% respondents chose land as one of the two most constraining institutional hurdles in Bangladesh’s development, possibly because the respondent assumed that this area needs specific knowledge of land administration. However, due to the design of the questionnaire, most of the respondents had to answer questions related to land, and it has one of the lowest average scores. This will be discussed later in detail.

Figure 3.3 Choice of institutional areas.

Note: For a description of the institutional areas, see Box 3.2.

The probability of framing bias must be considered, with the first areas in the list appearing more frequently than the other choices of respondents. It is possible that the respondents intentionally chose the areas with which they were affiliated as most constraining for Bangladesh’s development. However, since all respondents answered most of the questions (through primary and secondary questions), survey responses should be independent of biases and should have provided a robust idea about each of the constraints being discussed.

The choice of the top two constraints to development, according to respondents’ opinions, is a piece of information in itself, but it also determined the number of questions asked of each respondent. Given the explicit choices made during the selection of institutional field, the fact that respondents faced detailed questions about their top two choices, and not about other areas, raises a concern. Considering choices of institutional areas by sector of affiliation, it is possible that choices might be biased towards the sector of affiliation of the respondents. Additionally, it is quite possible that some less important areas are left out because there is no information about them. Alternatively, some institutional areas might be left out because of a perception that they were working well, or they could work poorly but be considered unimportant for economic development. For these two reasons, it was important to gather information about all areas. It was thus decided to ask all primary questions in relation to all areas. For this, even the less critical institutional fields were covered by all respondents.

Analysis of the survey results show that choices of institutional areas were somewhat different for male and female respondents. The top choice of male respondents was political institutions, whereas for female respondents, it was mainly public services. This is in line with general norms since women mostly experience discrimination at the public service level. The rest of the institutional areas received an almost equal degree of preference.

Another interesting observation from the CIS results relates to the choices of institutional areas by political affinity. The choices of institutional area of respondents from both the ruling and opposition parties are skewed towards political institutions. Politicians from the ruling party did not consider the business environment as involving any institutional constraints. On the other hand, given the current context and circumstances, it is surprising to see that supporters of the ruling party considered public services as one of the constraints. The institutional choices of respondents with no political affinity are almost equally distributed across institutional areas.

The choices of institutional areas made by respondents from the business sector differed depending on the specific sector they were affiliated with. For respondents affiliated with agriculture and manufacturing, the top choice was ‘Business environment’. However, for those affiliated with the service sector, it was ‘Justice and regulations’. It is very interesting to see that the choice of ‘Land’ as an institutional area was more common for respondents from the service sector than for those from the other two sectors. Respondents affiliated with agriculture chose ‘Public services’ as a constraint more frequently than respondents affiliated with manufacturing or the service sector.

2 The Perceived Functioning of Institutions in Bangladesh

Within and across areas, the CIS aimed to identify, as precisely as possible, which specific institutions were perceived as constraining by respondents. The subsequent analysis evaluates questions by their mean response on a scale ranging from 1, ‘very negative’, to 5, ‘very positive’. For questions asked in a negative way, the Likert scale is inverted to make sure that a higher value always means a better perception. Questions are then divided into clusters and sub-clusters to closely identify the core problems of the institutions in Bangladesh. This section first discusses the state of Institutional areas captured by the CIS and what are the underlying state of each of the institutional areas. Then the underlying problems of the institutions in Bangladesh are discussed. Finally, the choice of institutional constraints is discussed from the perspective of respondents’ gender and political affiliation, to identify any differences correlated with respondents’ characteristics.

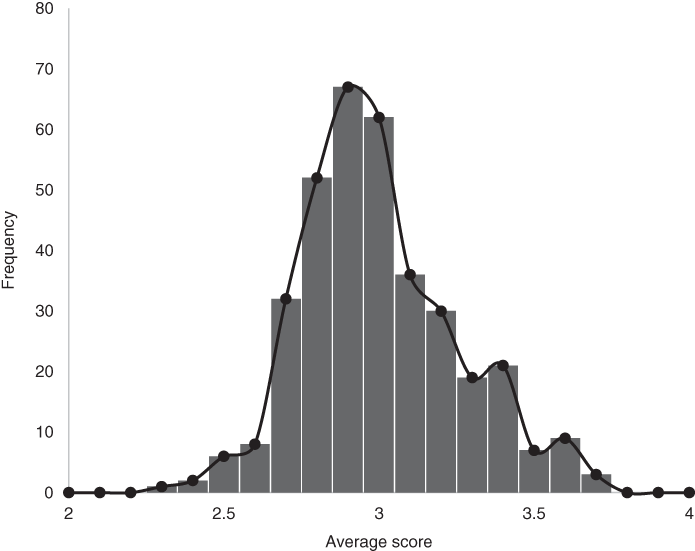

The negative perception of institutions in Bangladesh can be observed if we consider the distribution of the average scores of each of the questions. The mean score is 2.81, slightly below the mid-point of the Likert scale, lying at 3. This is not unusual in opinion surveys and may simply reflect the ways in which respondents answer questions. It is therefore more interesting to look at the tails of the distribution: namely, questions with clearly positive or negative answers. Figure 3.4 plots the distribution of questions by average score. It shows that the left tail (negative perception) is fatter than the right one (positive perception). A total of 131 questions has an average score below 2.5, while only 39 score above 3.5.

Figure 3.4 Distribution of questions by average score – all questions.

Note: Total number of questions: 415. Options in the Likert scale: 0 = no opinion; 1 = very negative; 2 = negative; 3 = neither negative nor positive; 4 = positive; 5 = very positive.

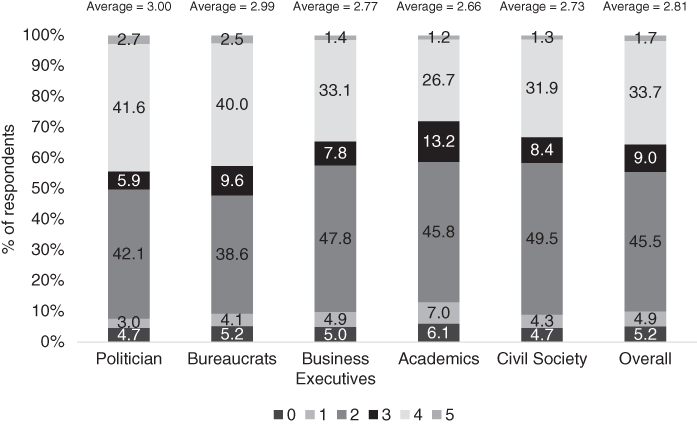

Looking at the perception of the institutions by sector of affiliation, we can see that the average score for each of the sector is either 3.00 or below (Figure 3.5) the threshold level. It is not very surprising to see that politicians and bureaucrats consider institutional quality to be slightly better than do academics and civil society members. Business executives on average gave a score of 2.77 for institutional quality in Bangladesh, a relatively low result. Figure 3.5 suggests that, in general, the no response rate was between 4.7% and 6.1%. While, on average, only 35.4% of respondents expressed positive views (4 and above) about the functioning of the institutions, leaving aside politicians and bureaucrats, all other three categories of respondents held much lower opinions. The dominance of ‘negative’ views (1 and 2 together) is the highest and is almost the same for business executives (52.7%) and academics (52.8%).

Figure 3.5 All questions – analysis by sector of affiliation.

Note: Options in the Likert scale: 0 = no opinion; 1 = very negative; 2 = negative; 3 = neither negative nor positive; 4 = positive; 5 = very positive.

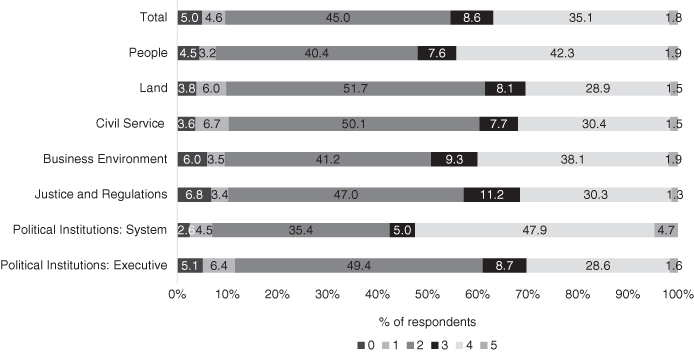

3 Distribution of Average Score by Cluster

Figure 3.6 depicts the percentage distribution of scores by each theme. As the figure shows, on average, the ‘no opinion’ view had a share of only 5%; the ‘very negative’ perception had a share of 4.6%; the ‘negative’ view had a share of 45%; the ‘indifferent’ view had a share of 8.6%; the ‘positive’ view had a share of 35.1%; and the ‘very positive’ view had a share of only 1.8%. The worst situation is observed in the case of the theme related to ‘Land’, where 57.7% of the responses were ‘negative’ (1 and 2), followed by ‘Civil service’ with 56.8%. The general picture drawn from these figures offers a pessimistic view of the institutions in Bangladesh. However, in the discussion of each institutional area by cluster and sub-cluster in the previous sub-sections, we identified specific problems associated with the institutions in Bangladesh. This is more useful than generalising perceptions of the institutions in Bangladesh based on these scores.

Figure 3.6 Percentage distribution of scores by theme.

Note: Options in the Likert scale: 0 = no opinion; 1 = very negative; 2 = negative; 3 = neither negative nor positive; 4 = positive; 5 = very positive.

4 Identification of the Major Areas of Institutional Weaknesses

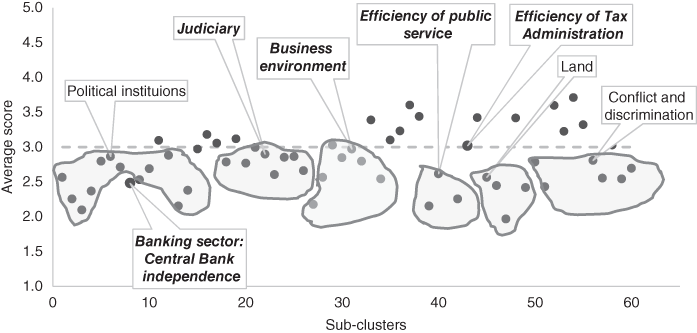

The previous section discussed the distribution of scores across institutional areas. We saw that, on average, the scores are well below 3. However, generalising these scores can be misleading. In this section, the scores for all the sub-clusters are plotted in Figure 3.7. Although we have previously discussed specific clusters and sub-clusters, a graph like this provides us with the broader viewpoint regarding the institutions in Bangladesh. This also gives us incentives to study further, and concentrate on, those thematic areas that we intend to study for the growth diagnostic for Bangladesh.

Figure 3.7 Major areas of institutional weaknesses.

Note: Options in the Likert scale: 0 = no opinion; 1 = very negative; 2 = negative; 3 = neither negative nor positive; 4 = positive; 5 = very positive.

It is clear from Figure 3.7 that institutional anomalies in Bangladesh are prevalent in relation to the judiciary, the business environment, the efficiency of public services, the efficiency of tax administration, and land. The discussion of each of these areas in the previous sub-sections illustrated that political institutions and conflict and discrimination are cross-cutting and are associated with these broader thematic areas, depending on the context of the discussion.

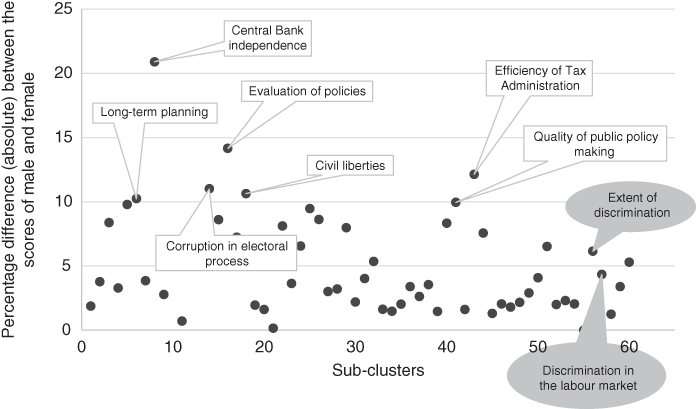

5 Perceptions of Institutions from a Gender Perspective

An interesting insight of the analysis is that the survey asked some questions related to discrimination based on gender. The majority of the respondents, regardless of gender, agreed that discrimination on the basis of gender is prevalent in Bangladesh. As the responses to these questions show the extent of discrimination spans both public authorities, society, and the workplace.

Figure 3.8 reports the responses where the largest percentage difference in responses (in absolute term), related to the sub-clusters, were found between male and female respondents. The figure shows that the largest difference in opinion between male and female respondents was in terms of long-term planning, central bank independence, evaluation of policies, corruption in electoral process, civil liberties, and quality of public policymaking. For these sub-clusters, the percentage difference in opinion was at least 10%. However, it is interesting to see that, though there were vast differences in opinion in the context of so many sub-clusters, both males and females agreed on the fact that discrimination exists in the society, especially in the labour market, as differences in responses were very low for these sub-clusters.

Figure 3.8 Percentage difference (absolute) in responses by gender.

6 Perceptions of Institutions Based on Political Affinity

The previous sub-sections have discussed in detail the institutional areas based on sector of affiliation. However, as the survey gathered information on the political affinity of the respondents, it is interesting to look at any differences in opinions based on such political affiliation.

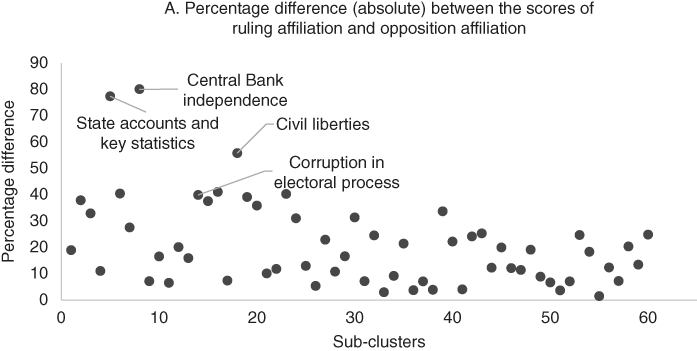

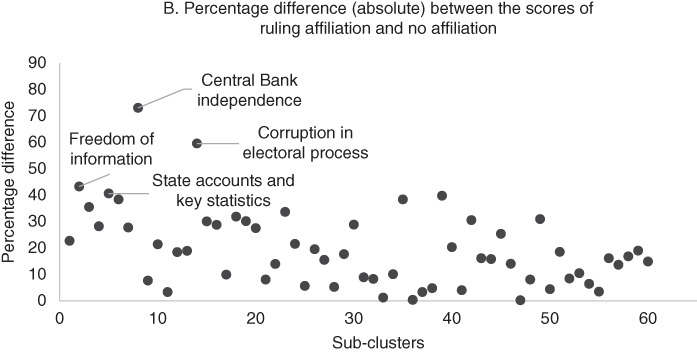

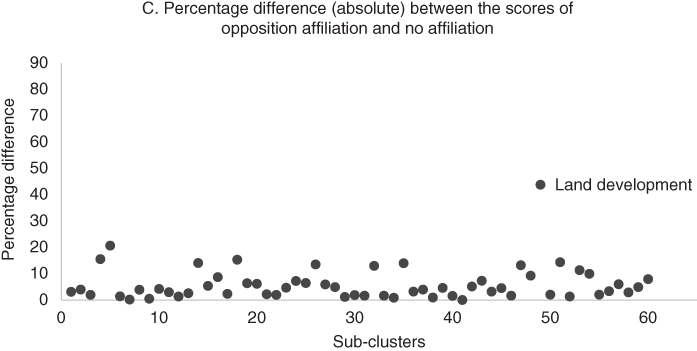

First, we plot the differences in opinions between the respondents who were affiliated with the ruling party and those affiliated with the opposition. This is depicted in Figure 3.9-A. The figure shows there was a vast difference of opinions between these two types of respondents. The average percentage of difference in responses lies around 20%.

A. Percentage difference (absolute) between the scores of ruling affiliation and opposition affiliation.

B. Percentage difference (absolute) between the scores of ruling affiliation and no affiliation.

C. Percentage difference (absolute) between the scores of opposition affiliation and no affiliation.

Figure 3.9 Percentage difference (absolute) in responses by political affinity.

Next, we plot the percentage difference between the scores of respondents with affiliation to the ruling party and respondents who did not express their affiliation to any political party (Figure 3.9-B). This is almost identical to the previous figure, with a low average percentage difference.

However, the most interesting point to note is that depicted in Figure 3.9-C, where we plot the differences in opinion between respondents with an affiliation to the opposition party and those without any political affiliation. This shows that the average percentage difference in opinions is very low – almost close to zero – showing the similarity between the opinions of affiliates of the opposition parties and the opinions of respondents with no revealed political bias, as regards the institutional areas. Those who stated they had ‘No affiliation’ are likely to often include opposition people who do not dare say so, or who do not want to be involved in politics.

7 Open-Ended Interviews with Top Decision Makers and Policymakers

Parallel to the CIS we conducted several open-ended interviews with top decision makers and policymakers in Bangladesh. These decision makers naturally were not interviewed in the same way as the other respondents to the CIS. Nor were they selected based on a stratified sampling technique. These interviewees were chosen simply because they had been working with the institutions in Bangladesh and/or were closely affiliated to and associated with the functioning of the institutional areas under discussion. These stakeholders (politicians from the ruling and opposition parties, bureaucrats – current and retired, business executives from different sectors, academics – teaching and research, NGO members, and other activities) were carefully chosen to avoid any kind of bias. They were asked several questions about the institutions and institutional diagnostics for Bangladesh. In their responses, they pointed to several sectors it may be useful to concentrate on in order to come up with diagnostic tools for Bangladesh. The anomalies in these sectors were then discussed in detail with these stakeholders. The main aspects of the institutional areas mentioned by these stakeholders are discussed below.

The failure of institutions to diversify markets and exports is causing Bangladesh to lose a huge sum of revenue. The major problems relating to market diversification include: a lack of comparative advantage; the inefficient use of available resources; poor capacity to ensure product diversification; high trade costs; poor physical connectivity; political patronage and bias; and the size of the importing country’s economy, etc. In Bangladesh, there are still no proper studies that have been conducted to understand the institutional failures in relation to market diversification. To this end, it is important to understand the dynamics of the vast concentration exports around the RMG sector and the neglect of other potential industries.

The key feature of the fiscal sector is the public revenue and expenditure management, with the aim of reducing infrastructure gaps, promoting private investment, generating employment opportunities, and ensuring the efficient redistribution of wealth through a pro-poor and inclusive fiscal policy. Data show that tax revenue is the major source of income or revenue for the Government of Bangladesh. Low administrative capacity and strong lobbying by businesses can be seen as the prime institutional failures as regards revenue generation for the Government. The Government should bring the target group under the tax net and make it mandatory to submit income tax returns, whether an entity is taxable or not. However, another important challenge to progress is mismanagement in expenditure in a weak institutional environment. Delayed funds disbursement, delay in land acquisition, and the lack of skilled project directors are also identified by the Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) of the Ministry of Planning as important reasons behind mismanagement in expenditure.

With a continual wealth transfer from the general public to the corruption-ridden and seemingly incompetent state-owned banks (and ultimately to defaulters), the non-performing loan (NPL) situation has worsened. In Bangladesh, the main source of total NPL is state-owned banks. The experts interviewed identified a few factors behind this situation. Of course, they mentioned systemic corruption, but they also went further and mentioned the appointment of corrupt officials to important positions at the state-owned banks as a fundamental reason for this. A few of the symptoms of political patronage in the sector are: the Finance Ministry’s overreach in licensing private banks while exercising political considerations; injecting incentives without the recommendation of the Bangladesh Bank; not complying with the suggestions of the central bank; and influencing the decisions of the autonomous central bank. Though it is an independent regulatory authority, the central bank cannot completely monitor these private banks as they are owned by politically influential people. Historically, there have been many regulations in the banking sector, especially relating to the entry/exit mechanism of banks and their governing bodies. The Bank Company Act, 1991, has been amended six times since its formation. Recent laws have sought to bolster political hold over the governance of these banks. These new laws have brought in changes in directorship positions, triggering a state of panic among depositors and other stakeholders. At the current point in time, from the discussion, we can see that the independence of the central bank is not producing its intended benefits, due to the presence of political pressure. Thus, the institutional efficiency of the banking sector hinges upon diversification of the sector, to control the ongoing political pressure place upon it.

Land litigation procedures and land management in Bangladesh are convoluted. With land being the most valuable asset in the country, the institutions associated with land management are susceptible to bribes. The influence of political patronage has made the transfer of land and land availability for businesses a complex issue. For better and more sustainable economic growth, the availability of land is crucial. However, the current situation in Bangladesh suggests that the problems associated with land are much politicised. Weaknesses in the institutions associated with land are related to the prolonged time required to obtain approval for transfer of land, politicisation in allocating land, and bribery in the transfer or approval of land use. As stakeholders mentioned, the convoluted nature of the problem and the failure of the judicial system to ensure justice in cases related to land may have a long-term impact on Bangladesh’s economic system.

The judiciary in Bangladesh is faced with many problems: a low number of judges compared to the number of cases; an unregulated system and laws; and the questionable independence of the system. All of this calls for an elaborate study on the subject. Complex procedures, case backlogs, and a lack of effective case management are also key constraints to the court system in Bangladesh. An independent judiciary is the sine qua non of democracy and of good governance. However, though the Constitution requires the separation of the judiciary from the executive, no steps whatsoever have been taken by the legislative or executive branch of the government in this regard. The independence of the judiciary is a must for any democratic country but attempts to influence the judiciary and steer it for political benefit are prevalent in Bangladesh.

D What Have We Learnt from the CIS?

The CIS and the open-ended discussion with top decision makers and policymakers has provided some interesting insights about the institutional functioning and mechanisms in Bangladesh. Key findings regarding the institutional strengths and weaknesses, and the recommendations of the stakeholders in the open-ended discussions, are consistent, even though the latter were able to go into more detail than the CIS. The following paragraphs summarises the most salient points that have come out of this double exercise.

In the first place, it should be stressed that the CIS yielded a ranking of problematic institutional areas similar to the one derived from exploiting cross-country institutional indicator databases, as reported on in the preceding section. Namely, the two areas found to be the most favourable (or perhaps the least unfavourable) to Bangladesh’s development are the business environment and the political system – an area that roughly fits the ‘democracy’ synthetic index in the preceding section. This convergence between insiders, that is local decision makers, and the experts behind the cross-country indicators, reinforces the view that other institutional areas than the preceding ones are problematic.

Second, it turns out that the general appraisal of institutional areas most likely to hinder development is not very informative, except perhaps in regard to the low weight put on land issues, something that is surprising given the emphasis of key informants on this aspect of Bangladeshi institutions. By contrast, in the CIS, the detailed evaluations were much more informative. They clearly put the civil service and land issues at the top of the list of poorly functioning institutional areas, closely followed by the state of political and administrative management exercised by the executive.

The sub-cluster analysis, within each institutional area, yielded still more interesting, because more precise, information. Of particular importance are the following weaknesses it pointed to:

ubiquitous corruption (election, business, and recruitment in civil service);

executive control of legal bodies, media, judiciary, and the banking sector;

inadequate coverage of public services;

the number and intensity of land conflicts; and

gender discrimination.

A few institutional aspects were also found to be rather satisfactory, though not always without some contradiction as regards other judgements. These include the general development of a middle class, the national feeling, and the quality of public policymaking. Of very special importance for the subsequent analysis in this volume is also the relative satisfaction regarding informal arrangements with the administration and as a way to secure contracts, as an efficient way of avoiding the ineffective formal channels. This may seem a bit paradoxical when evaluating institutions, but this opinion is quite revealing of what may be an important trait of the institutional context in Bangladesh.

Finally, the opinions expressed by the key informants generally confirmed the views of the CIS respondents: as, for instance, when they emphasised the low administrative capacity of the Bangladeshi state, corruption, or the ineffectiveness of the judiciary. But they added to the survey by pointing to sectors of activity where those weaknesses may be more salient. Of special importance from that point of view is their emphasis on industrial policy and the lack of diversification away from the RMG sector, to which this lead, possibly because of the over-influence of the RMG entrepreneurial elite. Key informants’ insistence on the severe failings in the regulation of the banking sector, the corruption behind the huge and increasing NPLs, and the lack of regulatory power on the part of the central bank are also deeply revealing of the way several institutional weaknesses generate deep inefficiency in a key sector of the economy.