[Illegal immigrants] don’t want to use guns because it’s too fast and it’s not painful enough. So they’ll take a young, beautiful girl, 16, 15, and others, and they slice them and dice them with a knife because they want them to go through excruciating pain before they die. And these are the animals that we’ve been protecting for so long. Well, they’re not being protected any longer, folks.

—President Donald Trump, June 2017Footnote 1

In 2015, Kate Steinle was shot and killed while walking on a San Francisco pier, arm in arm with her father. The crime was allegedly committed by an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, Jose Ines Garcia Zarate, who was acquitted of the murder charge in 2017.Footnote 2 President Donald Trump and other conservative politicians were quick to use the case to bolster their anti-immigration agenda. Calling her “beautiful Kate,” Trump used Steinle’s death to advocate for building a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border and ending sanctuary city policies. In this use of rhetoric, Trump was far from unique; the trope of White women being victimized by Latino men is common in immigration discourse. While scholars of political behavior know that images of racialized criminality prime racism among White Americans (Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1997; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Peffley, Shields, and Williams Reference Peffley, Shields and Williams1996), much less is known about the effects of the victim’s racial and gender identity. In this article, I demonstrate that portraying the victim as a White woman connects benevolent sexism with White Americans’ immigration attitudes.

Many scholars have documented that immigrants who commit crimes are commonly depicted as Latino (Mohamed and Farris Reference Mohamed and Farris2019; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013) and men (Farris and Mohamed Reference Farris and Mohamed2018; Famulari Reference Famulari2020; Gonzalez O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Benjamin, Reedy and Collingwood2019) and victims as White women (Baick Reference Baick2020; Brown Reference Brown2016; Cacho Reference Cacho2000; Stoler Reference Stoler2001). Moreover, this combination of a Latino immigrant and a White woman increases the newsworthiness and political weight of a crime incident, as in the deaths of Steinle in 2015 and Mollie Tibbets in 2018 (Gonzalez O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Benjamin, Reedy and Collingwood2019).Footnote 3

Political scientists have shown that presenting immigrants as Latino men connects immigration opinion to racist attitudes (Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Valentino, Brader, and Jardina Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013).Footnote 4 Less attention, though, has been paid to the impact of the race and gender of crime victims on immigration opinion. This means that scholars may have overlooked the ways these frames engage White Americans’ racism as well as paternalistic forms of sexism.

This article investigates how myths of Latino immigrant criminality not only evoke racial/ethnic predispositions but also engage ideas about gender: specifically, the paternalistic protection of White women. I argue that this framing of immigration activates racialized ideas about protecting femininity. To begin, I examine how conservative rhetoric imbues immigration discourse with the idea of gendered White injury, mapping long-standing narratives of racialized gendered and sexual threats onto Latino immigrants. I discuss, in turn, the “victims” of immigration, the historical use of similar rhetoric in the United States, and the role of benevolent sexism in American public opinion—including how benevolent sexism is linked to ideas about race.

Next, I test this theory using an original survey experiment and nationally representative survey data. First, the experiment demonstrates the causal role of the crime victim’s race and gender in linking benevolent sexism and immigration attitudes. When a White woman is presented as the victim of a crime committed by a Latino immigrant, benevolent sexism—protective feelings toward women who embody traditional ideas about femininity—shapes White Americans’ immigration opinions. The experimental effects are most notable among White independents; the immigration attitudes of partisans appear to be less susceptible to priming. Second, nationally representative data from 2016 shows that White Americans high in benevolent sexism favor the protectionist policy of increasing patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border. Taken together, these findings illustrate that this protectionary form of sexism mobilizes support for restrictive immigration policies.

“Victims” of Immigration

Recent conservative immigration rhetoric pairs overstatements of immigrant (particularly Latino immigrant) crime with long-standing ideas of protecting White femininity. Immigration is a polarized issue among White Americans, with those who are generally opposed to immigration more likely than others to identify as Republicans and support Republican candidates (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015).

Crime has increasingly been connected to national immigration news since 2000, with a 15% increase since the much-discussed killing of Kate Steinle in 2015 (Gonzalez O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Benjamin, Reedy and Collingwood2019)—despite evidence that immigration does not increase crime and might even reduce it (Ousey and Kubrin Reference Ousey and Kubrin2018).Footnote 5 Messages about “angel moms” and sanctuary cities link race and gender with perceptions of criminality and victimhood. The term “angel moms” refers to mothers whose children died in crimes involving immigrants, though the vast majority of cases involve car accidents rather than grisly murders (Baick Reference Baick2020). Donald Trump often invoked “angel moms” in speeches, even inviting the women onstage at his rallies.Footnote 6 In this formulation, “a dead child is an angel, and the ‘angel mom’ must be remembered. It is a theology of vengeance. It is also an image of women as being lost, with only men capable of restoring the natural order” (Baick Reference Baick2020, 355).

Symbolic emphasis on victims of immigration, though, is no new phenomenon. Cacho (Reference Cacho2000) argues that the rhetoric opposing California Proposition 187 in the early 1990s framed White Californians as the victims of increased immigration, conflating economic and racial anxieties. Indeed, the text of the proposition linked immigration and crime: “The People of California … are suffering personal injury and damage by the criminal conduct of illegal aliens in this state” (Cacho Reference Cacho2000, 393). Thus, “illegal aliens” and “the People of California” are defined in opposition to one another, rather than as overlapping categories. The term “angel moms” and its use highlight (generally White) mothers, leading Longazel (Reference Longazel2021) to argue that this rhetoric reflects and promotes a similar framing of White injury.

In crime news generally, White women are commonly overrepresented as victims—a concept known as “missing White woman syndrome.” Indeed, quantitative evidence shows that White women victims of abduction or kidnapping receive a disproportionate amount of media coverage relative to their actual victimhood rate (Sommers Reference Sommers2016)—by contrast, Black women crime victims receive little news attention (Lindsey Reference Lindsey2022; Wanzo Reference Wanzo2009).

Historical Context

Racialized sexual violence threats have a long history in American politics, emerging after the Civil War as the primary (though false) justification for the rape-lynch system (Bederman Reference Bederman1996; Hall Reference Hall1974; Wells Reference Wells and Gates1892). These racialized sexual threats, or peril narratives, are cultural scripts in which a dominant-group woman faces imminent harm by a man outside the dominant group (Stoler Reference Stoler2001). Undue emphasis on these particular threats elides the harms that dominant-group men commit against women (Davis Reference Davis1983). In the context of immigration, the peril narrative positions immigrants as masculine, threatening, and racially other, while positioning victims as feminine, vulnerable, and powerless to defend themselves.

Similar messages have been used repeatedly in American politics and media throughout the twentieth century. For instance, in the battle over school desegregation, White segregationists specifically fought to keep White girls and Black boys apart: they viewed school integration through the lens of eventual miscegenation. As President Dwight D. Eisenhower said of White southerners, “All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big black bucks” (Driver Reference Driver, Hasan, Huq and Nussbaum2018, 42). A more recent example is the “Central Park Five” case, in which five Black and Latino teenage boys were arrested for the rape of a White woman—all were later exonerated (Duru Reference Duru2003).

In the U.S. context, uses of the peril narrative typically involve Black men, but the same narrative structure is easily mapped onto other men of color—in the case of immigration, Latino men. Beltrán (Reference Beltrán2020) connects Trump’s immigration rhetoric to nineteenth-century newspaper justifications of the rape-lynch system. She argues that his rally speeches “conjure images of ‘deadly sanctuary cities’ where ‘dangerous, violent, criminal aliens’ are continually ‘hacking and raping and bludgeoning’ American citizens” (Beltrán Reference Beltrán2020, 105–6).

The Subtler Face of Sexism

Sexism is typically understood as outright hostility or animosity toward women. While this understanding of sexism as misogyny is the dominant understanding, sexism also has a positively valanced side. Benevolent sexism invokes warm, protective feelings toward women who embody traditional feminine virtues of morality, purity, and chastity (Winter Reference Winter2023). Benevolent sexists believe that men should protect women, women should be in heterosexual relationships, and women are different from men in subjectively positive ways. Benevolent sexism does not fit “standard notions of prejudice” but nonetheless narrowly defines women as weaker and inferior to men (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996, 492). There is increasing evidence that benevolent sexism, with its emphasis on paternalistic protection, shapes public opinion and voting (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019; Gervais and Hillard Reference Gervais and Hillard2011; Winter Reference Winter2023).

Benevolent sexism can help us understand which so-called victims of immigration cue restrictive immigration attitudes.Footnote 7 On its face, the benevolent sexism measure captures attitudes about gender and sexuality, but it also relates to ideas about race. The model of femininity implicit in benevolent sexism—specifically, protective paternalism—is most strongly associated with dominant-group women. Protective paternalism encompasses the beliefs that women should be put on a pedestal, women should be cherished and protected by men, men should sacrifice to provide for women, and women should be rescued first in a disaster (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996, 500).

Indeed, there is mounting evidence that benevolent sexism engages not only ideas about gender, but also implicit ideas about race. In an experiment by McMahon and Kahn (Reference McMahon and Kahn2016), when respondents were only given information on a woman’s race, they expressed higher levels of benevolent sexism for White women than for Black women. Relatedly, Cassese, Barnes, and Branton (Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015) show that modern sexism and racial resentment shape attitudes on the same policy issues.

Benevolent sexism encompasses racialized conceptions of gender. Sexism and racism are intersectional and should be considered simultaneously (Collins Reference Collins1991; Combahee River Collective 1977; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Research building on this concept has found that the race and gender of policy beneficiaries impacts political attitudes. Intersectional race-gender stereotypes shape White American’s attitudes on public policy (McConnaughy and White Reference McConnaughy and White2015) and political protest, including the Black Lives Matter movement (McConnaughy Reference McConnaughy2017).Footnote 8

Focusing on ideas of protection, McMahon and Kahn (Reference McMahon and Kahn2018) find that protective paternalism is cross-sectionally correlated with anti-Black bias.Footnote 9 Within White nationalist ideologies, White women are prized for their reproductive potential in perpetuating the race (Mostov Reference Mostov and Mayer2012). Comparing narratives of racialized sexual violence to racialized narratives of physical but nonsexual crimes, Smilan-Goldstein (Reference Smilan-Goldstein2023) finds that benevolent sexism is only activated in cases of sex offenses. I expect that benevolent sexism will shape immigration opposition when White Americans are exposed to a White woman victim of immigrant crime. The structure of the peril narrative, when applied to the case of immigration, suggests that White women victims will uniquely evoke paternalistic responses.

Hypotheses

I expect that narratives of Latino immigrant men victimizing White American women will make benevolent sexism—as well as racial/ethnic animus—salient in White Americans’ immigration attitudes. The experiment allows me to explore and confirm how benevolent sexism is associated with protective immigration policies. I hypothesize that depicting a Latino immigrant man’s crime against a White woman—compared to a Black or Latina woman or a man—will forge a stronger association between benevolent sexism and anti-immigration attitudes. When the crime victim is not a White woman, I expect the role of benevolent sexism to diminish, because men and non-White victims do not fit the structure of the peril narrative and White injury. I expect threats against White women to elicit support for policies of surveillance, removal, and separation from American society.

Given the framing of immigration in the particular racialized, gendered terms outlined earlier, I expect that observational data will show that more benevolently sexist White Americans will favor certain restrictive immigration policies. More specifically, I expect that the more benevolently sexist White Americans are, the more they will favor protectionist immigration policies, such as increasing patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border. I expect these findings to hold even accounting for the effects of racial/ethnic animus. Meanwhile, benevolent sexism should have smaller or no effects on immigration policies that are not related to ideas of physically protecting the American public, such as granting undocumented immigrants legal status. Finally, as Republican politicians most regularly draw on images of Latino immigrant criminality and White women’s victimhood, I expect White Republicans, and perhaps independents, to be most susceptible to this messaging.

If these hypotheses are incorrect, there will be no difference in how sexism and racism shape immigration attitudes depending on victim race and gender. Additionally, if immigration attitudes are not connected to gender attitudes, the two will not be associated in either the experimental or observational analyses.

Research Design

I conduct two analyses to test these hypotheses. First, I turn to an original survey experiment using a convenience sample. The experiment allows me to manipulate the race/ethnicity and gender of a victim of a crime perpetrated by a Latino immigrant man while holding all other features of the framing constant. The treatment works to link gender and racial/ethnic attitudes with views on immigration. I find that the presence of a White woman victim primes the strongest relationship between benevolent sexism and restrictive immigration attitudes compared with victims who are non-White women or men of any race or ethnicity. Second, I establish the external validity of these findings, using data from the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). I show that benevolent sexism is especially associated with greater support for the protectionist policy of increasing patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border—even absent the framing provided in the experiment.

Survey Experiment

To test the effects of types of victims on immigration attitudes, I conducted a survey experiment using a Mechanical Turk (MTurk) sample (N = 1,005) on August 18, 2019. The study was restricted to U.S. participants, and these participants were paid $0.84 for their time.Footnote 10 MTurk convenience samples have been criticized for their deviations from nationally representative samples, but scholars are reaching a consensus that MTurk samples are imperfect but adequate for use in experimental research (Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Coppock Reference Coppock2019; Mullinix et al. Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015). Though not representative, my sample is broadly similar to the U.S. public on important demographic dimensions. Relative to the 2016 CCES nationally representative sample (using the UVa team survey weight), the unweighted MTurk sample overrepresents men by about 3 percentage points, non-Hispanic Whites by about 7 percentage points, and Democrats by about 10 percentage points; the sample underrepresents those making more than $70,000 a year by 3.5 percentage points. The sample overrepresents individuals with a bachelor’s degree by about 20 percentage points.Footnote 11

Participants were asked to read a news article that describes a Latino immigrant man’s crime against a randomly assigned young person. I randomly assigned the victim to be either a young woman or man and (independently) to be White, Black, or Latino/a. Each article described a sympathetic high school student who was murdered by a man identified as an illegal immigrant from Mexico. Although the article was artificially constructed for this study, it was modeled on actual news coverage of immigrant crime.

Each treatment article was identical except for the gender and race/ethnicity of the victim, which were both conveyed implicitly (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001). The victim’s racial identity was conveyed visually with an image and his or her name, as well as his or her mother’s name. The victim’s gender was expressed with the images, the use of gendered names and pronouns, references to him or her as a “cheerleader” or “football player” in the headline, and quotations calling for protection of “our daughters” in the female-victim treatments versus “our families” in the male-victim treatments. Though “sons” would provide a more direct comparison to “daughters” in the text of the article, politicians typically invoke “families” in discussing crime to avoid the implication that men cannot protect themselves from crime. It is possible that using the term “families” instead of “sons” may overestimate the effects of benevolent sexism as applied to the young men in the treatments. The victim in each image was high school aged, holding books or other school supplies.Footnote 12 It is worth noting that the public is generally more sympathetic toward children who are victims of crime than other age groups (Zelizer Reference Zelizer1994), which could heighten the effects of benevolent sexism in the experiment.

The articles stated that a high school student had been killed by an illegal immigrant, and included some details on the crime:

{NAME} was fatally shot while walking home from Springfield High School last week. Police have arrested Javier Lopez, who came here illegally from Mexico, on charges of first-degree murder.

I intentionally presented the immigrant as being in the country illegally and from Mexico, as these characteristics align with how Americans typically imagine immigrants (Dick Reference Dick2011; Ramakrishnan, Esterling, and Neblo Reference Ramakrishnan, Esterling and Neblo2014). The charge of first-degree murder indicates intentionality and is likely perceived as more threatening than a manslaughter charge.

My primary interest is in the contrast between White man and White woman victims and between White victim and non-White victims. I assigned respondents disproportionately to the White man and White woman conditions, which maximizes my statistical power to detect differences between those two treatments, and between the White and non-White (Black and Latino/a) treatments (see Table A2 in the online appendix). Immediately after exposure to one of the articles, I included a factual manipulation check (Kane and Barabas Reference Kane and Barabas2019) and excluded from the analysis 10 respondents who failed it.Footnote 13

I measure sexism using a condensed version of Glick and Fiske’s (Reference Glick and Fiske1996) benevolent and hostile sexism questions.Footnote 14 As benevolent and hostile sexism are correlated and capture related attitudes, I include hostile sexism as a control variable to isolate the effects of benevolent sexism.Footnote 15 I include three questions to measure hostile sexism and five questions to measure benevolent sexism. Of the benevolent sexism measures, two measure protective paternalist attitudes, one measures attitudes toward comparative gender differentiation, and one measures attitudes toward heterosexual intimacy. For example, a statement of protective paternalism is that “men should be willing to sacrifice their own well-being in order to provide financially for the women in their lives.” The hostile sexism and benevolent sexism measures have a slight positive correlation (ρ = 0.17) and are measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

To account for attitudes toward Latino/a or Hispanic individuals, I measure ratings of Hispanics using three 7-point stereotype scales ranging from hardworking to lazy, intelligent to unintelligent, and peaceful to violent. I then take the average of these three stereotype ratings (α = 0.88). I also measure racial resentment (an average of four questions on a 5-point Likert scale). Though racial resentment focuses on attitudes toward Black Americans, and animosities toward different racial groups have specific nuances, researchers have found racial resentment to be a valid and reliable measure of White Americans’ views on group-based inequality. It is known to influence immigration attitudes (Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Matos Reference Matos2020) and racially coded policy attitudes (Kam and Burge Reference Kam and Burge2019), and it is useful in understanding White Americans’ racial/ethnic prejudices beyond anti-Black racism alone (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015).

I asked a series of questions on gender identity, education level, and party identification to include as control variables in regressions. A question on the economic effect of immigration accounts for the alternative explanation that economic considerations alone shape immigration attitudes (Dancygier and Donnelly Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013; Hanson, Scheve, and Slaughter Reference Hanson, Scheve and Slaughter2007).

To avoid priming ideas about sexism, Hispanic stereotype ratings, and racial resentment before exposure to the treatment, I measured these independent variables after the dependent variables. Klar, Leeper, and Robison (Reference Klar, Leeper and Robison2019) argue that this approach is appropriate for avoiding pre-exposure priming in experimental studies of identity, and the same line of logic should apply to studies of identity-based animus (but see Montgomery, Nyhan, and Torres Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018). Others use the same approach when studying the priming of racism and sexism (Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001; Valentino, Hutchings, and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002; Winter Reference Winter2008). I find no statistically or substantively significant differences on these measures across conditions (see Figure A6 in the appendix).Footnote 16 Though it is possible the treatments primed racial/ethnic animus and sexism, it seems unlikely they would have uniformly primed these attitudes regardless of the featured victim. For instance, it is unlikely that hostile and benevolent sexism would have been primed equally by women and men featured as victims. I conclude, then, that the treatments had limited effects on respondents’ reported levels of racial resentment, Hispanic stereotype ratings, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism.

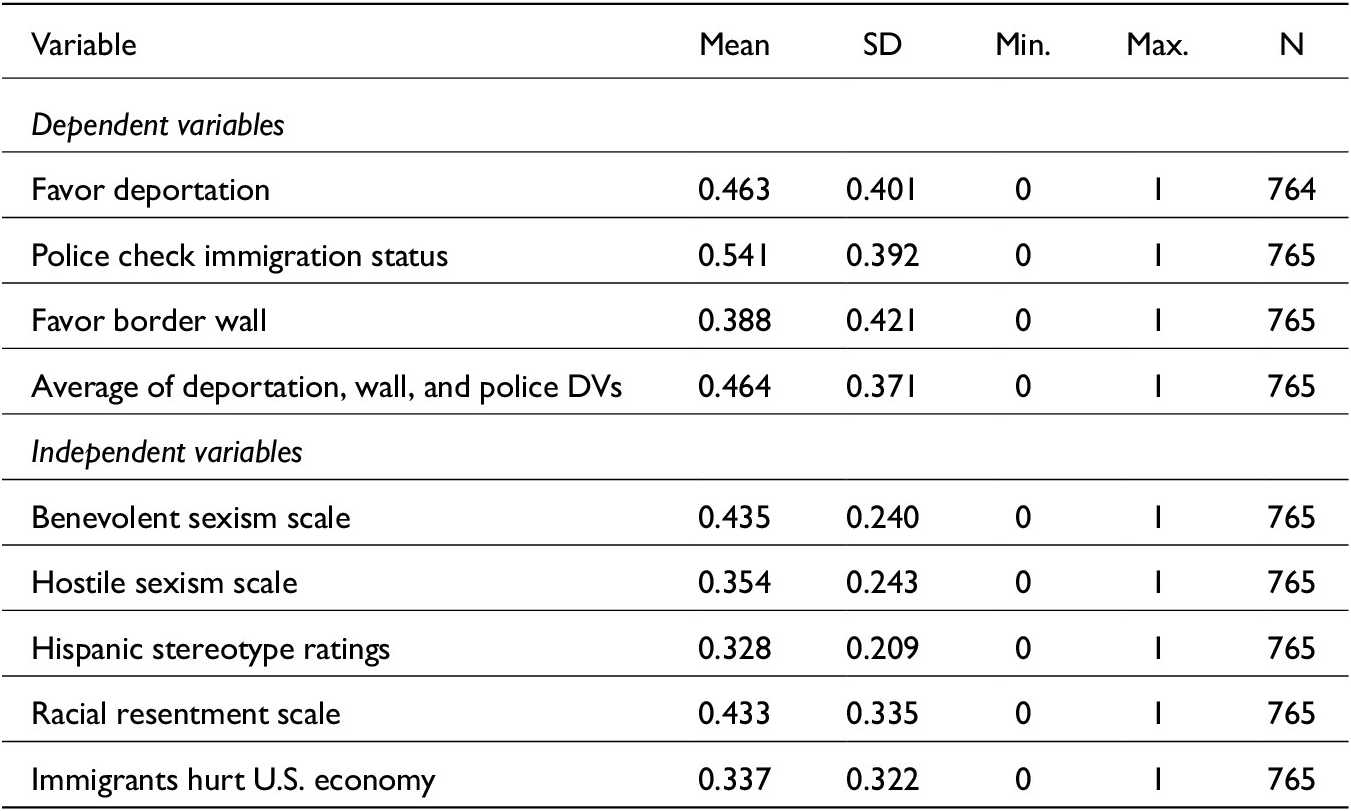

My primary dependent variable is a composite measure of punitive immigration policy opinion, calculated as the average of three ordinal variables: (1) whether all immigrants living in the United States illegally should be deported; (2) whether the United States should build a wall on the southern border; and (3) whether the police should check people’s immigration status if they suspect they are in the country illegally.Footnote 17 These variables focus on attitudes toward physically removing immigrants, restricting immigrants’ movement, and surveilling and racially profiling immigrants, respectively (see Table 1 for summary statistics of the dependent and independent variables). The study at hand focuses on undocumented immigrants: where immigrants are mentioned in these survey questions, they are identified as being in the country illegally or potentially being in the country illegally.Footnote 21

Table 1. Dependent and independent variables, summary statistics

Note: Unweighted data from MTurk experiment in August 2019. Run among White respondents who passed a manipulation check.

Survey Experiment Results

I use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to model the effects of benevolent sexism, hostile sexism, and racism, along with the other control variables, on immigration attitudes.Footnote 18 The composite anti-immigration variable serves as my dependent variable. Models are estimated in Stata 16, and all variables used in my analysis have been rescaled to run between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating anti-immigration attitudes and 0 indicating pro-immigration attitudes. The models are estimated among White respondents who passed the manipulation check.

First, I examine the effect of priming the peril narrative and logic of White injury on immigration attitudes. Benevolent sexism only affects the expression of restrictive immigration attitudes when the victim of immigrant crime is a White woman.Footnote 19 In a model that interacts condition and benevolent sexism, a 1-point increase in benevolent sexism is associated with a one-fifth increase (p < .05) in holding restrictive immigration attitudes among White respondents who read about a White woman victim, holding hostile sexism, racial resentment, Hispanic stereotype ratings, perceptions that immigrants hurt the economy, and respondent partisanship, gender identity, and education level at their means (see Figure 1).Footnote 20 In all other conditions, benevolent sexism has virtually no effect on immigration attitudes. All marginal effects are substantively small (between –0.04 and 0.10), and none reaches conventional levels of statistical significance. This supports my hypothesis that benevolent sexism is primarily salient in shaping White Americans’ immigration attitudes when they are faced with a White woman victim.Footnote 21

Figure 1. Effect of benevolent sexism on anti-immigration attitudes.

Focusing on the case of the White woman victim, I disaggregate by respondent partisanship (see Figure 2). I find that the effect of benevolent sexism on restrictive immigration attitudes is driven by White independents. Among White independents assigned to the White woman victim, a 1-point increase in benevolent sexism is associated with a 0.37 increase (p < .05) in reporting restrictive immigration attitudes.Footnote 22 White independents assigned to the White woman condition who are in the bottom 10th percentile of benevolent sexism are at 0.39 on the anti-immigration attitude scale, compared with 0.76 for a White independent in the top 90th percentile of benevolent sexism. While the different intercepts of anti-immigration attitudes make evident that White Republicans have stronger anti-immigration attitudes than do White Democrats, the effect of benevolent sexism on immigration attitudes is not significant for either type of partisans when they are exposed to a White woman victim.

Figure 2. Effect of benevolent sexism on anti-immigration attitudes, White woman victim.

Overall, my analysis shows that when victim race/ethnicity and gender are primed in a crime story featuring a Latino immigrant, White women victims make benevolent sexism salient in immigration attitudes. Across experimental conditions, I find that racial resentment has a large, positive, and statistically significant effect (p < .05) on White Americans holding restrictive immigration attitudes, with the exception of the Black woman victim condition (see Table A5 in the appendix).

Regardless of treatment, an increase in belief that immigrants hurt the U.S. economy is associated with a statistically significant increase in White Americans reporting restrictive immigration attitudes. Hostile sexism has a positive and statistically significant relationship with restrictive immigration attitudes when respondents are presented with a White woman or Black man as the victim. Meanwhile, Hispanic stereotype ratings have little relationship with immigration attitudes, regardless of condition. Overall, the experimental findings support the hypothesis that benevolent sexism, in addition to racial attitudes, shapes White Americans’ immigration attitudes.

Observational Data

To assess the external validity of the relationships I find between benevolent sexism, racism, and immigration attitudes, I use the 2016 CCES common content and the University of Virginia’s (UVa) module (Hughes Reference Hughes2019). The survey used a national, representative sample of Americans who were recruited in the fall of 2016 by YouGov. Respondents were surveyed in two waves—before and after the 2016 presidential election—with 1,500 completing the survey before the election and 1,269 returning to complete the survey after the election.

The UVa module includes a four-item measure of benevolent sexism developed by Winter (Reference Winter2023) as a shorter version of Glick and Fiske’s (Reference Glick and Fiske1996) 22-item measure. The CCES common content includes a battery measuring racism, though these are distinct from the racial resentment and Hispanic stereotype rating questions that I use in the survey experiment.Footnote 23

To measure immigration opinion, with a focus on undocumented immigrants and immigration from Mexico, I rely on four items from the CCES common content: whether the United States should (1) identify and deport illegal immigrants; (2) grant legal status to people brought to the United States illegally as children but who have graduated from a U.S. high school; (3) grant legal status to all illegal immigrants who have held jobs and paid taxes for at least three years and have not been convicted of any felony crimes; and (4) increase the number of border patrols on the U.S.-Mexican border. Items 1–3 explicitly refer to immigrants who came to the United States illegally, and item 4 focuses on immigration across the southern border. Each of these items is binary, asking respondents to agree or disagree with the statement (see Table 2 for summary statistics of the dependent and independent variables).

Table 2. Dependent and independent variables, summary statistics

Note: Data from CCES 2016 using UVa team survey weight. Run among White respondents.

I also include data on respondents’ gender identities, party identifications, income levels, and education levels to use as control variables in my analysis. To account for the alternative explanation that economic considerations shape anti-immigrant attitudes, I include respondents’ belief that the national economy is worsening as a control variable. Only White respondents are included in my model, as my hypotheses are specific to this group.

Observational Results

I use OLS and logistic regression to model the effects of benevolent sexism, hostile sexism, and racism, along with the other control variables, on the policy opinion variables. Models are estimated in Stata 16, using the UVa team survey weight. All variables used in my analysis have been rescaled to run between 0 and 1 for ease of comparison, where 1 indicates anti-immigration attitudes and 0 indicates pro-immigration attitudes. Each of the models presented here controls for hostile sexism, FIRE (fear, institutionalized racism, and empathy) racism, perceptions that the national economy is worsening, party identification, gender, and education level.

Benevolent sexism is strongly associated with wanting to increase patrols of the U.S.-Mexico border (see Figure 3; see Table A6 in the appendix for full models). A 1-point increase in benevolent sexism is associated with a 39 percentage point increase (p < .05) in supporting an increase in border patrols among White respondents.Footnote 24 This relationship is driven by White women: among White women respondents, a 1-point increase in benevolent sexism is associated with at 56 percentage point increase in supporting more border patrols (p < .05), while the same association is smaller and not statistically significant among White men. Supporting the deportation of undocumented immigrants, opposing legal status for Dreamers, and opposing legal status for undocumented immigrants who meet requirements are not associated with benevolent sexism.

Figure 3. Association between benevolent sexism and immigration attitudes.

Consistent with prior literature on immigration attitudes, both racism and perceptions that the national economy is worsening are associated with a statistically significant increases in anti-immigration attitudes. One exception is that perceptions of the national economy do not have a statistically significant association with preferences for increasing border patrols, the policy that was most strongly associated with benevolent sexism.

Thus, benevolent sexism has a notable impact on White Americans’ support for increasing border patrols.Footnote 25 My analysis shows that connections between benevolent sexism and immigration attitudes generalize beyond the experimental context when it comes to defending national boundaries.

Discussion

These studies aimed to determine the degree to which White Americans’ opposition to immigration is related to the gender and race/ethnicity of purported victims of immigrant crime. More specifically, I sought to understand whether benevolent sexism underlies anti-immigration attitudes in particular ways when White women are represented as crime victims and Latino immigrant men are represented as criminals.

The experimental results suggest that benevolent sexism explains White Americans’ anti-immigration attitudes only when the victim in question is a White woman. This effect of benevolent sexism on immigration attitudes is driven by White independents. That White independents have more malleable immigration attitudes is consistent with the literature on immigration and partisanship among White Americans (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Matos Reference Matos2020). Meanwhile, a Latina or Black woman victim of immigrant crime does not activate benevolent sexism among White Americans of any party affiliation.

Turning to the 2016 CCES data, I find that more benevolently sexist White Americans are more supportive of protectionist immigration policy. Benevolent sexism has a substantively and statistically significant association with favoring an increase in surveillance and defense of the U.S.-Mexico border among White Americans. The idea of protecting national boundaries from external treats is congruent with the logic of benevolent sexism, which extends masculine protection to potentially vulnerable women.

These are new insights for understanding what forms of prejudice motivate immigration policy attitudes, more generally, as Americans’ immigration policy attitudes are typically considered only in terms of racial/ethnic animus in political science research. I conclude that benevolent sexism can be activated in messaging around immigration, yet the activation of benevolent sexism does not generate wholesale change in immigration policy preferences. With the exception of McMahon and Kahn’s work (Reference McMahon and Kahn2016, Reference McMahon and Kahn2018), scholars of public opinion have not probed the connection between benevolent sexism and immigration.

Across the observational and experimental studies, the effects of benevolent sexism on immigration attitudes are robust to different measures of racial/ethnic animus. Differences emerge in the individual effects of FIRE racism and racial resentment on anti-immigration attitudes, but all coefficients are positive.

More generally, past scholarship has documented the connections between racial/ethnic prejudice and immigration attitudes. Specifically, Brader, Valentino, and Suhay (Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008) provide evidence that White Americans’ attitudes toward immigration are far more negative when presented with a Latino male immigrant rather than a White male immigrant. Valentino, Brader, and Jardina (Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2013) build on this, showing that anti-Latino/a attitudes, rather than general ethnocentrism, best explain anti-immigration attitudes. Prior work on racial priming and immigration attitudes aids our understanding of how racial resentment is an important aspect of opinion formation on immigration. I shift the angle of analysis, demonstrating that benevolent sexism and narrative congruence provide distinct effects on White Americans’ immigration attitudes.

This study also contributes to work arguing that the activation of benevolent and hostile sexism influences preferences for political candidates and policy attitudes. Evidence from the 2016 presidential election demonstrates that misogynistic cues from then candidate Trump activated hostile sexism in support of Trump and activated benevolent sexism in support of Clinton (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2019). Similarly, sexism predicted presidential vote choice in 2016 even when controlling for partisanship, authoritarianism, and other predispositions (Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018), and hostile and benevolent sexism also affected candidate evaluations in down-ballot races (Winter Reference Winter2023). Less work has been devoted to understanding the effects of benevolent sexism on policy attitudes, though some research has shown that these attitudes affect how individuals think about gendered policies like abortion regulation (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Davies, Sibley and Osborne2016) and bathroom access for transgender people (Blumell, Huemmer, and Sternadori Reference Blumell, Huemmer and Sternadori2019).

Meanwhile, a body of empirical criminology research has examined differential sentencing and court decisions by perpetrator race and gender (Crew Reference Crew1991; Romain and Freiburger Reference Romain and Freiburger2016) and considered both victim and perpetrator race and gender (Franklin and Fearn Reference Franklin and Fearn2008). The effects of race and gender on sentencing are mixed. Possible interactions between benevolent sexism and racial resentment provide a promising avenue for understanding American public opinion on issues that are both gendered and racialized.

The findings of this study identify one pathway through which intersecting attitudes about race/ethnicity and gender shape immigration policy attitudes. White men and women protect White femininity under White supremacist patriarchy to perpetuate ideas of racial purity. Meanwhile, women of color do not typically experience benevolent sexism from White Americans, as protecting Black and Latina women from harm does not serve the linked agendas of patriarchy, White supremacy, and capitalism (Collins Reference Collins1991; Davis Reference Davis1983). Instead, racially marginalized women are exploited by multiple systems of domination.

Black feminist scholars have long argued that analysts must consider the overlapping nature of racism, sexism and other axes of oppression to fully understand how these ideologies work in tandem to produce uniquely harmful outcomes for those at their intersections (Collins Reference Collins1991; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Race/ethnicity and gender cannot always be easily separated from one another when researchers examine attitudes toward groups (Briggs Reference Briggs2000), as distinct stereotypes connect the two in American political culture. This idea has been taken up more recently in political science research (Cassese, Barnes, and Branton Reference Cassese, Barnes and Branton2015; Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Junn Reference Junn2017; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011; Strolovitch, Wong, and Proctor Reference Strolovitch, Wong and Proctor2017). Intersectional stereotypes are a tool for understanding the particular stereotypes associated with overlapping group categories, such as race and gender.

This study is consistent with past work finding that individuals rely on distinct stereotypes about groups defined by both race and gender, and explicit cues make these stereotypes relevant to political evaluations (Cassese Reference Cassese, Redlawsk and Oxley2019; Hayes, Fortunato, and Hibbing Reference Hayes, Fortunato and Hibbing2021 McConnaughy and White Reference McConnaughy and White2015). Relatedly, individuals’ positionality within multiple identity groups shapes out-group hostility, with individuals who belong to at least one marginalized group typically exhibiting more egalitarian attitudes than those who do not (Proctor Reference Proctor2021). Recent evidence also shows how racial cues are linked with gender cues, with racialization cues from association with President Barack Obama affecting Secretary Clinton more than President Joe Biden because of Clinton’s gender identity (Bell and Borelli Reference Bell and Borelli2023).

Conclusion

I find that White woman crime victims bring benevolent sexism to bear on immigration attitudes. Even when immigration is not discussed in the context of criminality or of specific race/ethnicity-gender groups, benevolent sexism predicts attitudes on patrolling the U.S.-Mexico border. Researchers should consider race/ethnicity and gender simultaneously to better understand public opinion on immigration.

This study presents several questions. First, the precise mechanism through which benevolent sexism affects immigration attitudes is unclear. It is possible that anger is a causal factor in this story, as those with high levels of benevolent sexism wish to protect White women as a resource. Fear could be an important emotional pathway for benevolent sexism as well. Second, though I do not expect the same model to work when the immigrant in question is a Latina woman, rather than man, this notion is not empirically tested. Further, this study helps explain only White American’s immigration attitudes. It is reasonable to expect that the immigration attitudes of Black and Latino/a Americans, for example, will not fit into this framework. As previously discussed, benevolent sexism is itself racialized. These concepts may not transfer neatly to Black, Latino/a, and other racial/ethnic minorities’ conceptions of gender politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000521.

Competing interest

The author(s) declare none.

Acknowledgments

I thank Nicholas Winter, Paul Freedman, and Justin Kirkland for their feedback on multiple versions of this manuscript. I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.