Introduction

In the last three decades, the African continent experienced over 2,000 disasters, a trend that is likely to continue given the rapid and unplanned urban growth and the escalating impact of climate change. 1 Sierra Leone, one of the least developed low-income countries, ranks among the ten African countries reporting the highest disaster death toll in the past 20 years as a consequence of a number of disastrous events, including the regional epidemic of Ebola Virus Disease in 2014 and a series of mass-casualty incidents (MCIs) resulting from torrential rains, floods, and landslides. 2 In 2015, the government of Sierra Leone issued a post-Ebola recovery plan with the ultimate goal of building a resilient national system, enabling the health sector to provide essential health services, and to develop an integrated disaster risk management system. 3 As part of the essential health services package, the plan envisaged to improve the national prehospital referral transport system, a goal that was achieved in 2018 with the official launch of the first National Emergency Medical Service (NEMS). Reference Ragazzoni, Caviglia and Rosi4,Reference Caviglia, Dell’Aringa and Putoto5 The NEMS is a coordinated prehospital referral system that entails a fleet of 84 ambulances, 441 paramedics, and 441 prehospital care drivers working to provide timely prehospital care and transportation of patients to the nearest referral hospital under the supervision of 16 district ambulance supervisors and with the support of 36 operation center (OC) operators. Before taking service, NEMS personnel underwent a series of ad-hoc basic training courses developed by the Center for Research and Training in Disaster Medicine, Humanitarian Aid, and Global Health (CRIMEDIM; Università del Piemonte Orientale; Novara, Italy) and delivered with the support of the Italian NGO Doctors with Africa (CUAMM; Padova, Italy) under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS; Freetown, Western Area, Sierra Leone). Reference Ragazzoni, Caviglia and Rosi4 The courses embraced different topics, including the management of medical, trauma, obstetrics, gynecology, and pediatric emergencies and Basic Life Support and resuscitation maneuvers without the support of automated external defibrillator. Reference Ragazzoni, Caviglia and Rosi4 In addition, a series of refresh courses have been delivered to all NEMS personnel to improve their technical and attitudinal performances, with specific focus in those areas where gaps in knowledge, attitude, and practice were highlighted.

In its first three years of service, the NEMS has been challenged by a series of events that tested its resilience, including the 2019 Lassa Fever outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic, the latter requiring a number of structural adaptation to ensure both the delivery of routine services and the proper management of COVID-19 patients. Reference Caviglia, Buson and Pini6 A COVID-19 Special Training has also been provided to the prehospital health care teams and to the operators working at the NEMS OC focusing on the correct use of personal protective equipment; infection, prevention, and control procedures; case definition; triage; and dispatch procedures. Reference Caviglia, Buson and Pini6 In line with the national recovery plan 3 and according to the governmental willingness to reinforce disaster risk management institutions and capacities in the country, 7 in 2021, CRIMEDIM and CUAMM with the support of the MoHS developed a training package with the goal of strengthening the capacity of the NEMS to manage MCIs and respond to outbreaks. The aim of this paper is to describe the prehospital Disaster Training Package (DTP) implemented for the NEMS in Sierra Leone.

Report

Training Needs and Learning Methodology

The DTP was designed following the six-step approach to curriculum and training development Reference Kern, Thomas and Hughes8 with the ultimate goal of creating a workforce comprising qualified emergency responders with specific professional competencies to respond to outbreaks and MCIs. Since NEMS represents the first structured prehospital Emergency Medical Service of Sierra Leone, there was no previous experience in disaster and MCI training and education for prehospital providers in the country. In fact, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no similar training existed in the African continent at the time of writing of this manuscript, a gap that the World Health Organization (Geneva, Switzerland) Emergency Medical Teams initiative has started addressing in 2021 with the first Mass-Casualty Management course held in Ethiopia which, however, focused mainly on hospital response. 9 Therefore, to set the targeted learning objectives of the DTP, existing Disaster Medicine curricula designed by CRIMEDIM and other existing courses Reference Della Corte, Hubloue, Ripoll Gallardo, Ragazzoni, Ingrassia and Debacker10,11 were reviewed and adapted to produce a training package tailored to the local needs and based on local resources and capabilities. As such, the development process had to consider: (1) the country institutional architecture and national mechanism of response to disasters and MCIs; (2) the NEMS organizational structure; (3) the high burden represented by outbreaks and epidemics; (4) the medical resources present on the ambulances and current medical competences of the NEMS paramedics; and (5) the need to train all NEMS prehospital personnel, thus including approximately 1,000 providers, within a one-year timeframe. To guarantee the capillarity of the DTP throughout the 16 districts of the country and to enable its sustainability over time, the presence of the NEMS national trainers was leveraged, a pool of seven qualified trainers with health backgrounds, specifically as registered nurses or community health officers, responsible for all the NEMS educational activities. Therefore, the first task of the DTP was to develop a one-week training-of-trainers (ToT) course to equip national trainers with both basic knowledge in Disaster Medicine and the necessary skills to transfer this knowledge to all NEMS personnel through a peer-assisted learning (PAL) approach. Reference Topping12 The ToT courses aimed to prepare national trainers to critically replicate and lead the same types of exercises, promoting learners’ engagement, reflective practice, critical thinking, and skill acquisition. The second task was to develop a one-week cascade training to be delivered by national trainers to district ambulance supervisors, prehospital teams, and OC operators in the 16 districts of the country. The utmost goal of the cascade training activities was to help prehospital teams and OC operators familiarize with disaster concepts, but also to improve their attitudinal, behavioral, and technical performance, strengthening their existing professional skills and developing context-specific capacities to achieve an effective team performance. The educational strategy adopted included a blended methodology based on adult learning principles, combining traditional classroom teaching methodologies with practical exercises, group discussions, table-top simulations, and drills using mannequins and role players. The curriculum has then been presented to the MoHS representatives at NEMS to obtain support and financing and to identify and address potential barriers to its implementation. Lastly, an evaluation tool was designed to assess the individual performance of learners in a summative way, thus evaluating knowledge retention, and to assess their participation and awareness during the practical sessions.

Curriculum and Training Structure

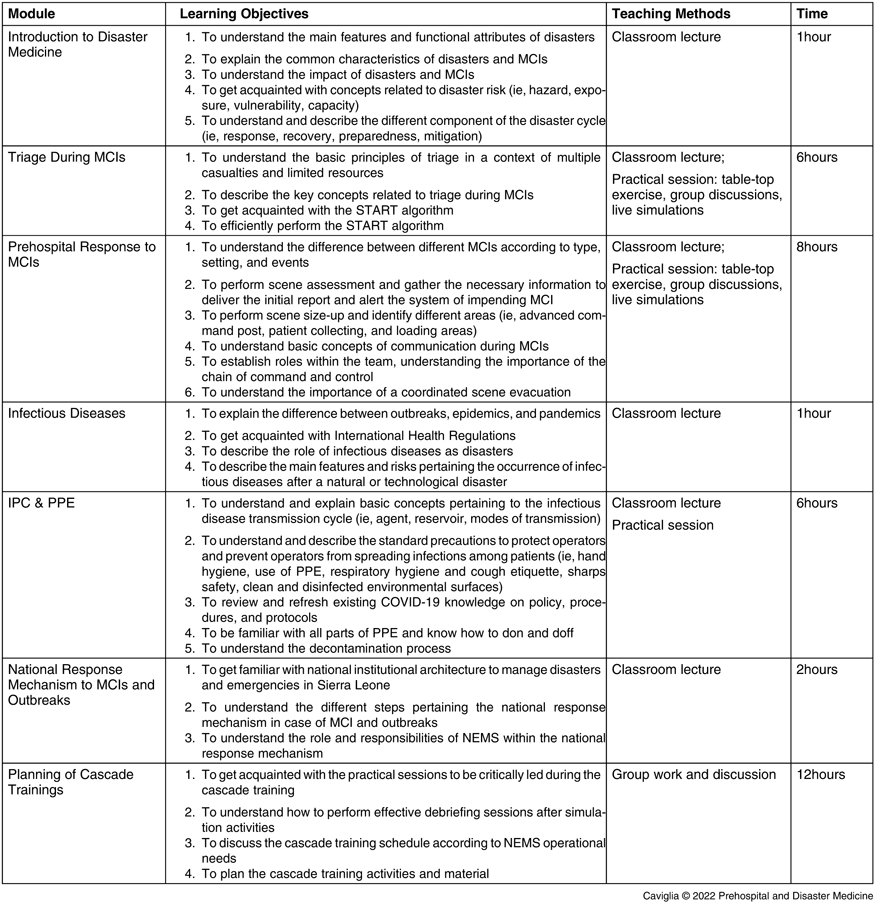

In Table 1, the ToT course curriculum is reported, including modules, learning objectives, teaching methods, and time allocated. Trainees were also exposed to a drill reproducing a mass-casualty scenario in which they were asked to perform specific tasks regarding scene assessment, proper communication and reporting to health authorities, primary triage using the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) algorithm, Reference Super, Groth and Hook13 and evacuation procedures. The objective of the drill was to exercise the newly acquired skills inside a realistic scenario, both as individuals and within the team, under the supervision of expert evaluators in charge of observing trainees’ performances and leading a post-drill debriefing session. The course was delivered by two qualified training managers with backgrounds in disaster and emergency medicine, supported by CRIMEDIM’s experts. The ToT course comprised a final examination that consisted of 24 multiple-choice questions to assess content knowledge, and test results were expressed as a score out of 100 with a minimum passing score of 60. Trainees’ participation and awareness during practical sessions were also evaluated using a one-to-five score. Participation was defined as “active engagement with course content, faculty, and fellow students” while trainees’ awareness encompassed a combination of social awareness (related to social connections within the group), task awareness (related to the steps needed to complete tasks), and concept awareness (related to the trainees existing knowledge in respect to the tasks). Reference Gutwin, Stark and Greenberg14 At the end of the course, the national trainers with the support of training managers, CRIMEDIM’s experts, and relevant stakeholders reviewed the cascade trainings to be delivered to NEMS paramedics, ambulance drivers, and OC operators. A group discussion was held to agree on the topics to be included, which comprised the same modules delivered in the ToT course in addition to a review session focusing on NEMS communication and handover procedures. A final examination consisting of 24 multiple-choice questions and a course evaluation questionnaire were also produced.

Table 1. Overview of the Training-of-Trainers Curriculum within the Prehospital Disaster Training Package Developed for the National Emergency Medical Service in Sierra Leone

Abbreviations: MCI, mass-casualty incidents; START, Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment; IPC, infection prevention and control; PPE, personal protective equipment; NEMS, National Emergency Medical Service.

Outcomes

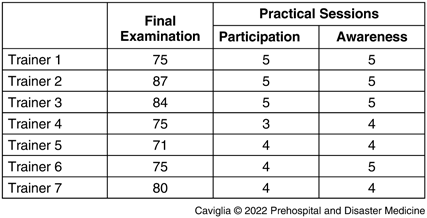

Starting on July 19, 2021, the ToT course was delivered to the seven national trainers. All trainers successfully passed the final examination and achieved high scores in the practical sessions, demonstrating active participation, commitment to the project, and good awareness (Table 2). The use of a hybrid learning approach featuring frontal lectures and practical sessions, a modality that has already been adopted during the delivery of NEMS basic training courses, Reference Ragazzoni, Caviglia and Rosi4 allowed to achieve excellent results concerning students’ engagement and knowledge retention. Following the ToT course, the series of cascade trainings started on August 2, 2021, delivered by the just-trained national trainers under the direct supervision of the two training managers. After three-month stop due to financial issues related to delays in external financing, the cascade trainings are currently on-going with the objective of reaching 1,000 NEMS prehospital providers by the end of the year.

Table 2. Evaluation of the NEMS Local Trainers Exposed to the Training-of-Trainers Course on Outbreaks and Mass-Casualty Incidents

Note: The final written examination included 24 multiple choice questions with a cut-off score for passing of 60 out of 100. Practical sessions were evaluated with a 1 to 5 score.

Abbreviation: NEMS, National Emergency Medical Service.

Discussion and Conclusions

The NEMS’ DTP is the very first Disaster Medicine training course delivered to prehospital health care providers in Sierra Leone. The curriculum development process followed a concrete educational framework, Reference Kern, Thomas and Hughes8 and the curriculum was tailored according to local needs. The adoption of a PAL approach, a modality that has been successfully implemented in several training programs for health professionals and also in the delivery of disaster medicine courses, Reference Santee and Garavalia15–Reference Ragazzoni, Conti, Dell’Aringa, Caviglia, Maccapani and Della Corte17 was beneficial both for NEMS national trainers and trainees. Indeed, the former had the chance to improve their individual competencies and skills, boosting their self-confidence and autonomy in the provision of training activities, while the latter had the possibility to learn in a “social and cognitive congruent” environment, where trainers and trainee sharing the same social role feel more encouraged to express informally and exchange ideas. Reference Lockspeiser, O’Sullivan, Teherani and Muller18,Reference Ten Cate and Durning19 The abovementioned considerations indicate that the provision of the DTP to all NEMS personnel has the potential to improve Disaster Medicine culture among health professionals in Sierra Leone. While education and training are the cornerstones of disaster preparedness and response, results in the literature clearly point out the lack of Disaster Medicine trainings in medical schools world-wide, Reference Ashcroft, Byrne, Brennan and Davies20 a deficiency that contributes to leaving health professionals unprepared when facing the consequence of disastrous events, which can rapidly overwhelm local resources and the ability to deliver comprehensive medical care. Few sporadic steps were made in the past years to provide Disaster Medicine education in African countries, 9 and in most cases, involved health professionals in South Africa, the most developed country of the continent. Reference Cowling, Swartzberg and Groenewald21,Reference Ivanov, Slavova, Vasileva, Alekova and Platikanova22

The authors strongly believe that the DTP delivered to NEMS personnel represents an important step towards the strengthening of disaster risk management efforts in the country, with the possibility to be extended to other emergency responders such as the police and fire department, as well as all the partners involved in the national response plan. Moreover, this experience has the potential to expand beyond its national borders and to foster the implementation of similar projects at the global level.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Marta Caviglia conceived the presented idea; participated in project administration, data curation, formal analysis, and investigation; drafted the article, designed figures and tables, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Josè Alberto da Silva-Moniz participated in project administration, investigation, and interpretation of results; critical revision of the article; and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Francesco Venturini provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, interpretation of results, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Amara Jambai provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Matthew Jusu Vandy provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Abdul Wurie provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Moi Tenga Sartie provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Giovanni Putoto provided study resources, participated in critical revision of the article, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.

Luca Ragazzoni participated in the study design, project administration, and supervision; participated in critical revision of the article, interpretation of results, and provided final approval of the version to be submitted.