Introduction

Ever since Peter Hall’s (Reference Hall1993) application of the paradigm concept to economic policy in the United Kingdom (UK), it has become a widely used, but at the same time extensively debated concept in the study of public policy. It has proved to be an effective approach to bring the role of ideas into policy research with policy paradigms providing the underlying ideas that guide the problem definition as well as the discussion and selection of policy alternatives during policy formulation and implementation (Kay Reference Kay2011). Existing research has shown how the paradigm concept can be used to explain both policy stability and policy change. When there is paradigmatic consensus – a single paradigm clearly being dominant in a specific policy domain – it shapes and constrains the policy debate, contributing to policy stability. The advent of rival paradigms (e.g. in periods of crisis), however, gives rise to paradigmatic contestation that can eventually result in what Hall labelled “paradigmatic” change. However, what happens if a policy domain is characterised by ongoing paradigmatic contestation that is not settled with the emergence of a single dominant paradigm? More specifically, the central question this article seeks to answer is to what extent and how paradigmatic contestation and paradigm mixes allow policy-makers room for manoeuvre when developing and legitimating policy proposals.

Hall (Reference Hall1993, 280) expected paradigmatic contestation to result in major disagreement among policy actors and inherently unstable policy, but he did not reflect on the consequences of paradigmatic contestation for policy-makers’ room for manoeuvre. Recent research in the domain of trade policy calls Hall’s expectation of policy instability into question. Daugbjerg et al. (Reference Daugbjerg, Farsund and Langhelle2017) have convincingly shown that while paradigmatic contestation between a market-oriented and an interventionist paradigm remains ongoing in the trade domain, and policy instruments consonant with either of the paradigms can be found in the policy regime, policy can nonetheless be stable and resilient. Focussing on policy stability and robustness as the policy outcome to be explained – rather than on the extent of the policy options and (discursive) strategies available in the decision-making process – these authors argue that a paradigm mix allows for containing ideational controversies and flexibly introducing policy solutions within the existing paradigm mix, which contributes to stable and resilient policies.

Taking these insights as a point of departure, this article shifts the focus from explaining policy stability and resilience to showing how situations of paradigmatic contestation and mixed paradigms – as opposed to situations of paradigmatic dominance or hegemony – affect decision-makers’ available strategies in the policy process through which policy stability (or change) is attained. It therefore primarily seeks to advance our knowledge of the public policy process rather than its outcomes. In doing so, this article makes a conceptual and an empirical contribution to the existing debate. Conceptually, a distinction is made between situations of a single dominant or hegemonic paradigm, paradigmatic contestation (different policy actors championing different paradigms without one being clearly dominant), and paradigm mixes (single policy actors appealing to different paradigms and diverse parts of the policy being based on different paradigms). I subsequently develop an argument of the type of strategies that policy actors have at their disposal in the three different situations. Apart from building on and synthesising insights from the existing paradigm literature, this argument also establishes a link between the different strategies and the concept of paradigmatic (in)commensurability. Departing from the two facets of the assumed incommensurability between competing paradigms – paradigms being internally consistent and mutually exclusive (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015, 298), I explain how relaxing the two different aspects of this assumption results in different strategies policymakers have at their disposal when legitimating their preferred policies. While empirical research has repeatedly claimed that in empirical reality paradigms are often neither completely internally consistent nor externally mutually exclusive (Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015; Princen and van Esch Reference Princen and van Esch2016), systematic theorising on how this affects policy actors’ room for manoeuvre, in terms of policy options and the repertoire of (discursive) strategies available to legitimate policy preferences in the decision-making process, remains limited. This article’s conceptual contribution to the paradigm debate thus also presents relevant insights for the literature on policy change more broadly conceived, by providing a better understanding of the process of policy change.

Empirically, the article shows first how a shift in the context of the European Union’s (EU) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) from a situation of paradigmatic dominance to one of paradigmatic contestation, aided the European Commission (Commission) in successfully instigating a shift in support focus from price intervention (product support) to direct producer support. Second, it shows how the Commission subsequently managed to safeguard the direct income payments instrument in later reforms, introducing incremental changes while leaving the core of the policy instrument untouched. In this process, increasing paradigmatic contestation and the emergence of paradigm mixes provided the Commission with a broader range of discursive strategies to address increasing demands and critique of the policy instrument. While the focus in this article is only on the CAP – a policy known for its paradigmatic contestation (Daugbjerg and Swinbank Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2009; Feindt Reference Feindt2010, Reference Feindt2017) – the contribution of the in-depth empirical analysis has importance beyond this single domain, as contestation already exists in more domains and is likely to develop in others. Apart from the agricultural policy domain, trade policy, environmental policy and monetary policy are other prime examples where paradigmatic contestation can be found (Nilsson Reference Nilsson2005; Skogstad Reference Skogstad2008; Feindt Reference Feindt2010; Alons and Zwaan Reference Alons and Zwaan2016; Princen and van Esch Reference Princen and van Esch2016; Daugbjerg et al. Reference Daugbjerg, Farsund and Langhelle2017). Furthermore, with increasing policy openness, policy consultations and shared policy jurisdictions, particularly within the EU, paradigmatic contestation and paradigm mixes instead of single dominant or even hegemonic paradigms are likely to become a phenomenon of increasing importance. These empirical developments reinforce the importance of this article’s conceptual contribution linking paradigmatic contestation with policy-makers’ strategies and ultimately policy stability and change.

The remainder of this article will first elaborate on the current debate on the paradigm concept in public policy studies. It subsequently introduces the conceptual distinction between paradigmatic dominance, paradigmatic contestation and paradigm mixes, explaining how relaxing the commensurability assumption – both in terms of internal consistency and external mutual exclusivity – broadens the array of strategies that policymakers have at their disposal to underpin and legitimate their policy preferences. The methods section will introduce and provide indicators for the three paradigms distinguished in the agricultural domain, and present the method of data selection and analysis. In the empirical part of the article, the effect of paradigmatic contestation on the Commission’s discursive strategies will be illustrated in the case of the introduction and development of direct income payments in the EU’s CAP between 1992 and 2013. The conclusion will reflect on what the findings mean for other political and institutional settings.

Policy paradigms in public policy studies

Hall defines a paradigm as an interpretive framework “of ideas and standards that specifies not only the goals of policy and the kind of instruments that can be used to attain them, but also the very nature of the problems they are meant to address” (Reference Hall1993, 279). Policy paradigms condition policy choices by affecting what policymakers consider “thinkable, possible or acceptable” (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Burns and Calvo2009, 16), as paradigms contain normative ideas affecting what policy options are considered acceptable and legitimate, and cognitive ideas about how the world works, affecting what policy alternatives are considered useful means to obtain policy objectives (Campbell Reference Campbell2002, 23, 32; Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015, 15). Distinguishing between policy goals, policy instruments and instrument settings, Hall subsequently makes a distinction between first and second order policy changes– where only instruments and settings change – and third order or “paradigmatic” change, referring to a more radical change including policy goals.

Empirical applications of Hall’s conceptualisation of policy paradigms and orders of policy change, however, have raised questions about whether the paradigm concept fits the empirical reality encountered in public policy research. An important element of critique involves his structuralist point of departure, focussing on punctuated equilibrium dynamics underlying “paradigmatic” change. This neglects the common empirical reality in public policy of incremental and gradual change (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2011; Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015; Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015) as well as the possibility of a number of incremental policy changes together resulting in a paradigm shift over time (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Pierre and King2005; Kay Reference Kay2011; Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015; Princen and van Esch Reference Princen and van Esch2016). The historical institutionalist approach Hall applies thus overstates the role of path dependency and the ensuing policy stability, neglecting conflicts over ideas and policy assumptions below the surface that can function as forces of more incremental change (Peters et al. Reference Peters, Pierre and King2005).

Furthermore, the ongoing paradigmatic contestation and existence of paradigm mixes in different public policy domains have caused scholars to question the incommensurability assumption that Hall – following Kuhn’s (Reference Kuhn1962) conceptualisation of paradigms – adheres to. Two implications of the incommensurability thesis can be distinguished. The first involves the “internal coherence” or “internal consistency” assumption, which implies that a paradigm is considered pure and coherent, “composed of logically connected elements” (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015, 298). A policy based on one paradigm should therefore not show inconsistent goals or policy instruments working at cross-purposes. The second implication emphasises that paradigms are “mutually exclusive” (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015, 298), proposing “fundamentally different, incommensurable ways of seeing the world, and of identifying and ordering core principles upon which policy is formulated and decided” (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Burns and Calvo2009, 389). Both aspects of incommensurability are put into question on the basis of empirical research showing that paradigms may be partly overlapping and commensurable (Skogstad Reference Skogstad2011; Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015; Princen and van Esch Reference Princen and van Esch2016), which is also the case in the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009, Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2015; Feindt Reference Feindt2010; Alons and Zwaan Reference Alons and Zwaan2016).

A way in which we can deal with the theoretical assumption of incommensurability and the apparent existence of (arguably commensurable) paradigm mixes in empirical reality is by making a conceptual distinction between paradigms on an epistemological and a political level (cf. Campbell Reference Campbell2002). On an epistemological level, paradigmatic ideas can be considered abstract ideal types or “blueprints” (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Burns and Calvo2009, 379), while at the political level they serve as “actionable ideas of agents engaged in the practice of policymaking” (Wilder Reference Wilder2015, 1005). In this political process the paradigmatic purity and incommensurability of policy ideas are often eroded due to the deliberation and compromises policymakers engage in (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Burns and Calvo2009, 399; Wilder Reference Wilder2015). This distinction allows for maintaining the assumption of incommensurability at the epistemological level, while relaxing this assumption and allowing for paradigm mixes – which policymakers can frame as being commensurable – at the political level. The focus in this article will be on this political level. In the analysis, the paradigm concept will be treated as a social construct or “relative” concept (Wilder Reference Wilder2015, 1009) rather than an objectively observable fact, because “what makes a policy paradigm coherent is policy actors conceiving them as coherent”, while “the perception of incommensurability is subject to change through deliberation and strategic framing on the part of policy actors” (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015, 300). This emphasises the interpretive character of policy paradigms and the politics involved, pointing at the significance of agency, with policymakers applying strategic framing in the policy process to convince others and obtain their preferred policies.

Paradigmatic contestation, paradigm mixes and policy-makers’ strategies

This article works from the assumption that policymakers operate in a political context in which they are confronted with a multitude of demands from interest groups, civil society and international actors, and need to reconcile these diverging interests when proposing a policy. Whatever the main causes behind policy-makers’ preferences for a certain policy instrument – be it based on material interests as rationalist and public choice approaches assume or rather shaped by ideational variables as constructivists claim – they apply legitimating discourses in their discursive interactions to further their interest. In this process ideas expressed in discourse can be used as “strategic devices” (Kurzer Reference Kurzer2013, 286) or weapons “with which agents contest and replace existing institutions” (Blyth Reference Blyth2002, 30) and can be geared towards “preparing the public for the implementation of acts and other measures or advocating and rationalising the existing ones” (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009, 219). Policymakers thus act strategically and the argument developed below is that the strategies they have at their disposal vary with the paradigm situation.

Paradigmatic dominance and paradigm stretching

In situations of paradigmatic hegemony or dominance, all important policy actors share adherence to a single paradigm, and no competing paradigms appear to be on the horizon. Agricultural policies in many Western countries after World War II may serve as an example here. The prominence of a food security goal and the idea of exceptionality of the agricultural sector compared to other economic sectors united policy actors in developing interventionist support policies based on a “dependent agriculture” paradigm (Garzon Reference Garzon2006). While policies are likely to be relatively stable in this situation as Hall (Reference Hall1993) observed, political battles may still arise over policy instruments, policies may prove ineffective, and in international interactions (e.g. trade relations) policymakers may be confronted with alternative demands and ideas.

Such challenges can to an extent be dealt with within the existing dominant paradigm, due to a paradigm’s “malleability” (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2015, 20), indicating a degree of ideational space that policy actors can use to defend diverse policy preferences. Schmidt and Thatcher (Reference Schmidt and Thatcher2013), for example, show that the meaning of “market paradigm” can be stretched to legitimate a variety of policy solutions and convince different audiences. This resembles what Hall considers covering anomalies by “stretching the terms of the paradigm” which he claims “gradually undermines the intellectual coherence and precision of the original paradigm” (1993, 280). Paradigm stretching thus goes hand in hand with relaxing the internal consistency aspect of the incommensurability assumption. Taking a relative view on incommensurability, it should be noted, however, that it actually does not even matter whether the diverse solutions are objectively commensurable with the paradigm or not. The paradigm stretching strategy eventually relies on the strength of the argument with which policymakers frame new instruments or goals as fitting within the existing paradigm.

Paradigmatic contestation and banking on paradigmatic inconsistencies

Vivien Schmidt argues “there is rarely one predominant paradigm; others are waiting in the wings” (Reference Schmidt2011, 40–41), indicating situations of paradigmatic contestation are more likely in empirical reality. I define paradigmatic contestation as situations in which different policy actors adhere to different paradigms, and while consecutive policy outcomes may show shifts in apparent paradigmatic dominance, powerful paradigmatic alternatives always remain in the background. Policymakers can use this situation acting as “bricoleurs” rather than “paradigm men” (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2011, 148, 156) by applying strategic framing, using different discourses based on different paradigms to: (a) address different audiences emphasising the discourse this audience already articulates in a bid to gain their support (Fouilleux Reference Fouilleux2004; Alons and Zwaan Reference Alons and Zwaan2016), and (b) legitimate different policy instruments. This results in a “hybrid discourse” (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009; Feindt Reference Feindt2017). As we will see in the case of the CAP, the Commission, for example, used a dependent agriculture discourse to legitimate income support, while it appealed to the multifunctional discourse to introduce environmental conditionality. I label this a “banking on inconsistencies” strategy, as it capitalises on the differences and inconsistencies between competing paradigms.

Paradigm mixes and the commensurability strategy

Paradigm mixes develop when diverse parts of a policy are being based on different paradigms and single policy actors appeal to different paradigms to further their policy preference. Such mixes may thus well be the (unintended) consequences of strategic behaviour aimed at reconciling diverging interests in society in situations of paradigmatic contestation. In this sense, paradigm mixes always involve paradigmatic contestation, while paradigmatic contestation does not necessarily imply the presence of paradigm mixes. Paradigm mixes are particularly likely to develop when many veto players – “actors whose agreement […] is required for a change of the status quo” (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis1995, 289) – are involved. This often leads to policy compromises with policy elements that are based on a paradigm mix (cf. Carstensen Reference Carstensen2011; Princen and van Esch Reference Princen and van Esch2016). Once a policy has entered this stage, the ideational basis of the policy has broadened due to the ideational differences and inconsistencies between the paradigms of which the mix is constituted. This allows for a wide array of fundamental and operational ideas – as well as the policy solutions they inspire – to be combined in one policy. Policy problems can thus more easily be solved within the existing paradigm mix (Daugbjerg et al. Reference Daugbjerg, Farsund and Langhelle2017, 1703). This argument is based on the differences and inconsistencies between paradigms and translates into the “banking on inconsistencies” strategies discussed above. While these strategies help policymakers obtain their preferences, they may also come at a cost, however, creating policy inconsistencies that are likely to hamper policy effectiveness and engender demand for reforms in the future. In this vein, the case of the CAP will show that the way income support (based on the dependent agriculture paradigm) was arranged, worked at cross-purposes with the policy’s instruments aimed at environmental preservation (based on the multifunctional paradigm) and engendered reform demands.

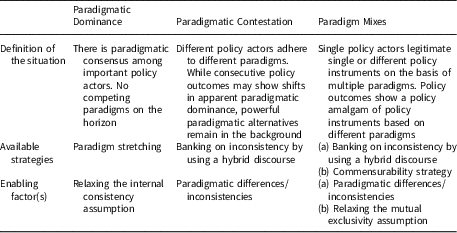

To prevent this, policymakers may use what I label a “commensurability” strategy. Relaxing the external exclusivity aspect connected to the incommensurability assumption, policymakers have two additional ways of strategic framing at their disposal, focussing on establishing commensurability. First of all, they can strategically frame an amalgam of instruments based on competing paradigms as being commensurable and consistent. Second, they can legitimate a single policy instrument on the basis of a mix of paradigms, indicating how the single instrument fits with the different paradigms – in effect presenting the paradigms as nonmutually exclusive – and furthers the associated policy goals. The commensurability strategy implies making explicit connections between competing paradigms, which requires skills and has its limits, as “ideas cannot be combined in infinite ways” (Wilder Reference Wilder2015, 1009). This also implies the strategic importance of policy instrument-selection, as some instruments are easier than others to legitimate on the basis of different paradigms simultaneously, thus allowing a hybrid discourse to convince a variety of audiences.Footnote 1 The commensurability strategy should be a policy-maker’s preferred strategy as it is likely to be considered a congruent and convincing argument in the policy process, contributing to longer-term policy stability. Table 1 summarises the three different situations and the associated discursive strategies. While the different strategies are not mutually exclusive and may be applied simultaneously, the “banking on inconsistencies” strategy presupposes paradigmatic contestation, while the “commensurability strategy” additionally requires the existence of a paradigm mix. Whether one paradigm situation should be considered better than another or not, is essentially a matter of perspective: paradigm mixes can be very convenient for policymakers in the short term, but in the longer term they may give rise to policy inconsistencies that hamper policy effectiveness.

Table 1 Paradigm situations and available discursive strategies

Methodology

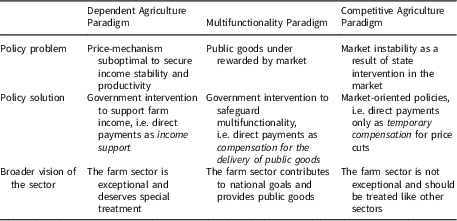

In studies on agricultural policy, the paradigm concept is often applied to qualify substantial policy outcomes in terms of different paradigms (Skogstad Reference Skogstad1998; Garzon Reference Garzon2006; Daugbjerg and Swinbank Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2009, Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2016) or to identify paradigms in the legitimating discourses used to underpin policies (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009, Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2015; Alons and Zwaan Reference Alons and Zwaan2016). This literature shows that agricultural policy is an issue area par excellence where new paradigms have surfaced over time and coexist. Three competing policy paradigms are distinguished in this literature. First of all, the dependent agriculture paradigm represents the farm sector as an exceptional sector different from other economic sectors (Daugbjerg and Swinbank Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2009), due to the unstable natural conditions farmers are confronted with and the relatively limited price elasticity of agricultural goods. As a result, the price mechanism is considered a suboptimal means of achieving an efficient and productive agricultural sector, and government intervention in the market is required to support sufficient farm income and sufficient production (Coleman Reference Coleman1998; Skogstad Reference Skogstad1998). This paradigm thus legitimates an interventionist agricultural policy. Second, the competitive agriculture or liberal market paradigm takes issue with the assumed “specialness” of the agricultural sector, arguing that it should be treated like any other economic sector. Market forces should take precedence over state intervention and be the prime determinant of income and production, while state intervention should be limited to providing a safety net and be of a temporary nature (Coleman Reference Coleman1998; Skogstad Reference Skogstad1998; Daugbjerg and Swinbank Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2009). Finally, the multifunctionality paradigm emphasises the multiple environmental and social functions of farming for which farmers are not rewarded by the market, justifying the granting of public money to farmers to safeguard the multiple functions or public goods that the agricultural sector supplies (Coleman Reference Coleman1998; Moyer and Josling Reference Moyer and Josling2002). Like the dependent agriculture paradigm, this paradigm legitimates more extensive state intervention in the agricultural sector, albeit on different grounds. Table 2 provides a summarising overview of the three paradigms. The differences in policy problems, policy solutions and broader vision of the sector associated with the various paradigms will serve as indicators on the basis of which policy actors’ legitimating arguments and discourses will be connected to the different paradigms in the empirical analysis.

Table 2 Policy paradigms in European agriculture

The EU’s shift from a focus on price support to income support to stabilise farm income, instigated with the 1992 MacSharry CAP reform and extended in subsequent reforms in 1999, 2003 and 2013, provides an appropriate case to illustrate the strategies that can be applied in different paradigm situations. As the case analysis will show, the CAP shifted from a situation of paradigmatic dominance to paradigmatic contestation and paradigm mixes in this period. For each of the reforms, the empirical part of this article will investigate the decision-making process with an emphasis on tracing the Commission’s discursive strategies. The main focus is on the Commission, because of its power of initiative, as a result of which it is the Commission developing CAP reform proposals and trying to guide these through the Council and the Parliament. The Commission is thus “located at the centre of the policy community, while superior authorities (heads of state and government) tend to intervene on behalf of the status quo” (Feindt Reference Feindt2010, 311). Although the member states and European Parliament (EP) eventually decide on the policy, the Commission specifies “and at times reconceptualiz[es] the alternatives among which Member States will ultimately choose” (Smyrl Reference Smyrl1998, 96). That said, the Commission is interested in reaching a policy outcome that is effective and politically sustainable. Confronted by varying demands from member states, interest groups (producers) and civil society as well as international actors, it will seek to balance opposing interests and defend policy solutions it deems politically feasible and acceptable. It will thus anticipate on or react to positions defended by other policy actors. Therefore, while a complete analysis of the interests and discourses of all these actors is unfeasible within the limit of a single article, their positions will be included in the analysis where relevant to specify the political context and associated interest-configurations in which the Commission developed its proposals and legitimating discourse.

A qualitative research design is applied for the empirical analysis. In line with existing studies focussing on policy paradigms, sources are selected that provide accounts of policy-makers’ ideas on policy problems, policy solutions and policy goals (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Burns and Calvo2009, 155; Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009, Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2015; Daigneault Reference Daigneault2015). The sources used to conduct the empirical analysis include: (1) official Commission communications, legislative proposals and regulation texts with respect to the four CAP reforms; (2) 10 speeches for each of the Commissioners of Agriculture involved; (3) official reports on Council (Working Party) meetings; (4) reports of the EP’s Committee of Agriculture and Rural Development; (5) opinion papers and letters from agricultural and environmental organisations; (6) media coverage; and (7) secondary literature. The official Commission, Council and EP documents allow for measuring policy positions, legitimating discourses and policy outcomes. The Commission speeches are selected to reflect variation in the audiences they address (EP, Council, interest groups), in order to uncover potential strategic discourses adapted to different audiences. Interest group positions are analysed based on their opinion papers and letters, while media coverage and secondary literature provide additional insights into both the positions of policy actors and the policy process. Table 3 gives an overview of the type of sources that were used to establish the positions and discourses of different policy actors. NVIVO, a qualitative content analysis software, was used to code the legitimating discourses in policy documents and speeches on the problem definitions, policy solutions (instruments) and policy objectives associated with the three paradigms.

Table 3 Overview of data and sources analysed

The CAP: introduction and development of direct income payments

The 1992 CAP reform: first step in the shift to income support

When the CAP was developed in the 1960s, the dependent agriculture paradigm was uncontested (Garzon Reference Garzon2006) and gave rise to a policy that focussed on price support to secure sufficient food supply and farm income. High guarantee prices were set for a large number of agricultural commodities in combination with variable import levies to establish “community preference”. This policy incentivised production and over time resulted in production surpluses that were partly dumped on the world market with the help of export subsidies. Both in terms of budgetary expenditure and trade relations with third countries, this policy came under increasing pressure in the 1980s, particularly from member states and trading partners in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade who favoured more liberal policies in line with a competitive agriculture paradigm (Moyer and Josling Reference Moyer and Josling2002; Garzon Reference Garzon2006) After different attempts to effectively constrain production in order to gain market balance had failed, Commissioner Ray MacSharry’s (Reference MacSharry1992b) CAP reform reduced guarantee prices by 30% and compensated farmers for their income losses by introducing direct payments. How did the EU arrive at this decision?

As early as the 1980s, the Commission realised that the focus on price support was not tenable, as it effectively achieved neither the goal of supporting farm income nor that of stabilising markets (Commission 1985, 1991a). In a paper titled “Perspectives on the CAP” it argued that reform should solve the policy problem (Commission 1985, 17):

A […] restrictive price policy, together with a number of well-directed accompanying measures could solve this problem at least in the medium term perspective. This would imply that the economic function (market orientation) of price policy is stressed at the expense of its social function of income support.

In line with these suggestions, the Commission’s reflection paper for the MacSharry reform in the early 1990s proposed a combination of price reductions accompanied by compensatory payments for all farmers. The Commission also proposed to differentiate between farmers on the basis of farm size and farm income to secure that the direct payments would particularly benefit those farmers who needed them the most (Commission 1991a, 12). This emphasises the policy’s farm income support objective, connected to the dependent agriculture paradigm. Critique of such differentiation from both member states and farmers, with the argument that this would entail discrimination against larger farms later instigated the Commission to drop the differentiation based on farm size and income (Agence Europe 1991; European Parliament 1991). However, the Commission did not give in to demands of farmers, the EP and several member states to withdraw the proposal for price cuts and direct payments altogether and intensify production controls instead (Agence Europe 1991).

Apart from addressing the farm income problem, the reform was also instigated to improve “market balance”, with the argument that “the new orientation of the CAP must lead to better market equilibrium and to a better competitive position for Community agriculture” (Commission 1992, 21). In his speeches, Commissioner MacSharry used a mix of arguments connected to both the dependent agriculture and the competitive agriculture paradigm. He argued that direct payments would provide a “more reliable basis for supporting farmers’ incomes” (MacSharry Reference MacSharry1992a) and also emphasised that price reductions would improve market balance and competitiveness, allowing farmers to increase their income from the market in the longer term (MacSharry Reference MacSharry1991b, Reference MacSharry1991c, Reference MacSharry1992a). While environmental arguments in accordance with the multifunctionality paradigm were not absent from the reform debate, MacSharry (Reference MacSharry1991a) argued for the recognition of a dual role of farmers as producers of food support and guardians of the countryside, for example, they were not applied to justify direct income payments. Instead, only agri-environment measures – which were not connected to direct payments – were explicitly presented as remuneration for services provided by farmers (Commission 1991b, 33). Isabelle Garzon (Reference Garzon2006) thus concludes that multifunctionality or public goods arguments were merely a side argument at this point.

By the late 1980s, the dependent agriculture paradigm (dominant in member states such as France and Germany as well as among farm organisations) was clearly challenged by the competitive agriculture paradigm (defended by more liberal member states such as the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands, as well as by trading partners), while the newly developing multifunctional paradigm provided an alternative justification for intervention in the agricultural sector. The Commission dealt with this paradigmatic contestation in two ways. First, it used the “banking on inconsistencies” strategy to legitimate different instruments of the CAP based on different paradigmatic discourses: a multifunctionalist discourse for the agri-environment measures and a competitive agriculture discourse for the price cuts, for example. Second, the commensurability strategy was applied to legitimate the instigated shift from price support to income support, constructing commensurability between the dependent and competitive agriculture paradigms by legitimating direct income payments both on the basis of a farm income and market balance. MacSharry’s emphasis on how the combination of price reduction and direct payments will eventually allow farmers to gain more income through the market is a clear example of how he frames that the objectives of both paradigms can be realised by shifting from price support to income support.

While scholars define the 1992 reform outcome in different paradigmatic terms – Coleman (Reference Coleman1998) speaking of a shift towards market liberalism and Daugbjerg and Swinbank (Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2009) arguing the dependent agriculture paradigm remained dominant – it clearly left the CAP in a situation of paradigmatic contestation. Moreover, the Commission’s strategic discourse in search of a policy compromise that simultaneously solved farm income problems and market inefficiencies through the shift from price to producer support laid the foundation for a paradigm mix.

Reforms under Fischler: the direct income payments’ rationale under pressure

Commissioner MacSharry was succeeded by Franz Fischler, who guided the CAP through two reforms – in 1999 and in 2003 – maintaining direct payments despite increasing legitimacy concerns. The introduction of direct payments had made the support to farmers more transparent to taxpayers and civil society than price support had been and as such more susceptible to critique. Starting in the deliberations on the 1999 CAP reform, the Commission indeed showed awareness of the legitimacy concerns attached to the shift from price support to direct income support, arguing the shift in policy instruments “increased the need for it to be economically sound and socially acceptable” (Commission 1997, 29). Two issues needed to be addressed. The first concerned the distribution of direct payments, as the dependent agriculture rationale of direct income payments as an effective means of securing farm income stability was under pressure due to the unequal distribution of the payments to the advantage of larger farms (Commission 1998, 3; Fischler Reference Fischler1999). The second issue concerned the rationale of the direct payments: why did farmers deserve these payments? This issue was raised by consumer organisations in the run-up to the 1999 reform, claiming that “the taxes that are imposed on EU consumers to pay for the CAP are out of all proportion to the benefits they derive from it” (EIS European Report 1997). The Commission sought to address these concerns both in the 1999 and 2003 reform, albeit using different strategies.

In its proposals for the 1999 CAP reform, the Commission proposed to make individual direct payments degressive above 100,000 euros – thus tackling the distribution issue – and making direct payments conditional on the respect of environmental provisions, in an attempt to improve the image and acceptability of the CAP (Commission 1997, 31; Commission 1998, 3). Fischler’s (Reference Fischler1999) discourse towards farm audiences focussed relatively more on the farm income problem and necessity of direct aid, but did not fail to explain that the proposed reforms were indispensible to legitimate the CAP. It should be noted that, at this point, the Commission particularly legitimated environmental conditionality – which they termed “cross-compliance” – as a way of satisfying societal demands and a general means through which to integrate environmental concerns in the CAP (Fischler Reference Fischler1997, Reference Fischler1999; Commission 1998, 3, 19). It was only the EP that very explicitly embraced a multifunctional rationale for direct payments, welcoming the instrument of cross-compliance as a step to gradually converting the compensatory payments into “remuneration by society for services rendered with a view to preserving the agricultural environment” (European Parliament 1998, 5). Farmers did not yet embrace a multifunctionalist discourse, but instead deplored the enhanced focus on direct payments, claiming that farm income should not come from the EU budget but from the market through guaranteed prices (Agence Europe 1997), in line with the dependent agriculture paradigm. Neither of the proposals eventually made it in the final reform due to member state opposition. They rallied against degressive payments as discrimination against larger farms (Agra Europe 1997) and objected to mandatory environmental conditionality, as a result of which the former was dropped altogether and the latter became a voluntary measure (Schwaag Serger Reference Schwaag Serger2001).

In terms of discursive strategies to safeguard direct payments, the Commission used a hybrid discourse, banking on inconsistencies between paradigms. It appealed to and sought to reestablish the existing “income” rationale based on the dependent paradigm by proposing degressive payments, while it referred to societal demand for a more multifunctionalist agriculture to support the environmental conditionality proposals. In the deliberations on the 2003 reform, the Commission would take a different approach.

At this point, the support prices had approached world-market levels and the continuation of direct income payments could no longer be legitimated as “compensation” for further price reductions. The justificatory discourse combining an income support and a market-orientation rationale, framing the dependent agriculture and competitive paradigms as commensurable, would therefore not work anymore. The Commission addressed this problem as well as the direct payment “rationale” issue that had not been solved in the 1999 reform with two initiatives. First of all, it developed the option of “decoupling” direct payments to maintain commensurability between the dependent and competitive paradigms. Second, in order to (re)legitimate direct payments, it presented these as in part a reward for the services farming provided for society, framing the dependent and multifunctionality paradigms as being commensurable. Both strategies will now be elaborated.

During the debate on the 2003 Fischler reform, the Commission considered that a problem of the CAP was that it was not yet sufficiently market-oriented, because the direct payments were still partly linked to production (Commission 2002, 6). Furthermore, it was argued that, over time, the direct payments “have lost their compensatory character […] and have become income payments, raising the question of whether the distribution of direct support is optimal” (Commission 2002, 8). The first solution – “decoupling” by introducing a Single Farm Payment in which the link between production and payments was largely removed – allowed for increased market-orientation while maintaining direct support. The Commission presented decoupling as “the natural conclusion of the shift of support from product to producer”, thus making the CAP more market-oriented (Commission 2002, 2, 18). Of course, decoupling support simultaneously exacerbated the rationale issue of what the payments were then for, if production could no longer be considered the service in return on the part of the farmer (Daugbjerg and Swinbank Reference Daugbjerg and Swinbank2016, 273). Such concerns were met by the depiction of direct payments as being in part remuneration for the environmental and social services farmers provide for society. In the words of Fischler: “Farmers are […] right to demand due reward for the quality products they supply, the environmental services they perform and their role in the upkeep of the countryside – in other words, for all the products and services that they provide for society. Direct payments remain essential in this context, since market prices alone are not enough” (Fischler Reference Fischler2002; see also Fischler Reference Fischler2001). The introduction of mandatory cross-compliance in the same reform gave credence to the argument that direct payments could at least also be connected to environmental services.

Contrary to the outcome in 1999, the Commission now succeeded in getting their proposals adopted, despite initial opposition from farmers and member states. A number of developments in the political context contributed to this outcome. First of all, decoupling direct payments would secure their position in the “green box” of support that was not subject to reduction in the World Trade Organisation. Second, the agricultural policy network had become increasingly open to the access of a broader range of interest groups, including environmental and consumer groups, increasing the pressure for environmental measures (Garzon Reference Garzon2006; Feindt Reference Feindt2010). Finally, at least in part due to these two developments, important policy actors had shifted their positions. The European farm organisation COPA-COGECA (2002) now also sought to safeguard direct payments as payments for services not remunerated through the market, thus applying a multifunctionalist rationale. Moreover, the Council now accepted the principle of cross-compliance, even though it still sought to and succeeded in limiting the number of requirements included in the measure. While the Council initially opposed decoupling – with the productivist arguments that severing the link between support and production would make it more difficult to legitimate and would imply losing an important means of market management – it eventually gave in and accepted 75% (instead of full) decoupling (Agra Europe 2003; Council 2003).

In terms of discursive strategies, the Commission applied commensurability strategies to legitimate decoupling and cross-compliance. Where decoupling helped to maintain commensurability between the competitive agriculture and dependent agriculture rationales for direct payments, the mandatory cross-compliance helped to underscore an additional environmental purpose for the policy instrument of direct payments, framing the dependent agriculture and multifunctionality paradigms as being commensurable.Footnote 2 Direct payments were thus transformed from compensatory payments, to income payments and remuneration for the provision of public goods. In the process, a genuine paradigm mix evolved in the CAP, with each paradigm institutionalised in different CAP instruments (Feindt Reference Feindt2017). While discursive studies particularly emphasise a shift towards the multifunctionalist paradigm by 2003 (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2009, Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2015), paradigmatic contestation continued, with a variety of actors defending different policy instruments based on different policy paradigms. It thus seems more accurate to speak of a rebalancing of the “paradigm blend” (Daugbjerg et al. Reference Daugbjerg, Farsund and Langhelle2017, 1698) than of a paradigm shift.

The 2013 CAP reform: the rationality of all rationales in question?

At the time of the 2013 CAP reform, the Commission was aware that both the dependent agriculture and multifunctionality rationales for direct payments were under pressure. First of all, because it was questioned whether the payments effectively established income stability and a fair distribution of income. Second, because the CAP policies, including the direct payments, were argued to still contribute to environmentally unfriendly farming practices. The Commission acknowledged the problems with the distribution of direct income support and aimed for redistribution, redesign and better targeting of the payments in the new reform (Commission 2010, 8; 2011, 15).

In order to support a more equitable distribution of direct payments it proposed to cap payments above a certain level and change the basis for the calculation of direct payments to obtain convergence both within and between member states. In relation to the capping proposal, Commissioner Cioloş argued that “[b]y redefining most of the direct payments as direct income support […] there comes a moment when we can no longer justify the level of support payable” (Reference Cioloş2011c, emphasis added) and “[a]bove a certain amount, is it still acceptable to talk of basic income aid?” (Reference Cioloş2011b). Capping was further legitimated by the argument that “due to economies of size, larger beneficiaries do not require the same level of unitary support for the objective of income support to be efficiently achieved” (Commission 2011, 13).

Member states such as Germany and the UK, as well as the farm lobby, argued, however, that if direct income payments are rewards for the provision of public goods, then large farms provide them just like small farms do and it would therefore not be justifiable to cap their payments (COPA-COGECA 2010; Council 2011). The eventual outcome of the reform only contained limited and voluntary capping, making the Commission’s attempt at reinforcing the rationale for direct payments based on the dependent agriculture paradigm only partially successful. It is interesting to see that both member states and farm lobby used the Commission’s own multifunctional rationale for direct payments against this reform effort. Previous Commission appeals to arguments based on the commensurability between the different paradigms in order to maintain direct payments in this case inhibited later reforms of these payments.

The Commission sought to address the environmental critique on the CAP by proposing increased environmental conditionality through the introduction of three “greening” requirements – crop rotation, ecological focus area and permanent pasture – that had to be met in order to receive 30% of the direct payments. Greening would ensure that “[a]ll EU farmers in receipt of support go beyond the requirements of cross-compliance and deliver environmental and climate benefits as part of their everyday activities” (Commission 2011, 3). It was aimed at improving the environmental image of the CAP and providing a clearer link between direct income payments and the services or public goods farmers provide to society (Commission 2010, 2011; Cioloş Reference Cioloş2010, Reference Cioloş2011a). In terms of discursive strategy, the Commission tried to strengthen the multifunctionality rationale for direct payments, gearing them more effectively towards the delivery of environmental services.

The greening requirements were particularly supported by environmental organisations, which had lobbied the Commission to include them in the CAP proposal (Alons Reference Alons2017). While Council and EP (European Parliament 2010) were quick to welcome the principle of greening, their approach towards the instrument seemed to be to have it serve as a justification for continued farm support through direct payments without significantly increasing the burdens on farmers. Moreover, their rationales for farm support increasingly included a productivist discourse connected to the dependent agriculture paradigm, emphasising the importance of farmers as food producers (Erjavec and Erjavec Reference Erjavec and Erjavec2015). This discourse was well received after price hikes in agricultural markets and subsequent concerns for food security. Considering this political context, it should not come as a surprise that the greening requirements were also significantly watered down by the Council of Ministers and Parliament and subsequently implemented in such a way that many farmers will not or will hardly have to change their production processes to meet the demands (Bureau and Mahé Reference Bureau and Mahé2015, 107–108).

In the Commission’s discursive strategy, the specific arguments for capping and greening were connected to a dependent agriculture and multifunctional agriculture rationale respectively, which resembles the “banking on inconsistency” strategy. However, the resulting new policy amalgam of “capped and greened direct payments” is framed in terms of commensurability between the dependent and multifunctional paradigms. The Commission thus connected two legitimate goals to a single policy instrument, stating that “[d]ecoupled direct payments provide today basic income support and support for basic public goods desired by European society” (Commission 2010, 4). While these discursive appeals may have been logically sound, the actual policy outcome still did not entirely solve the legitimacy issues that gave rise to the 2013 reform. The result has been renewed demands for reform as well as suspicions as to the Commission’s genuine motivations for reform being to maintain direct income payments rather than environmental policy integration. The environmental demands in the currently ongoing negotiations on a new CAP reform should be seen in this light.

Conclusion

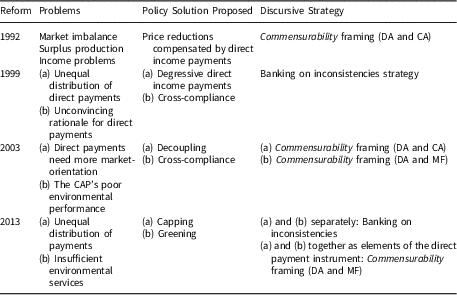

While much has been written about determinants of policy stability and policy change, this article shifted the focus from policy outcome to policy process, investigating how contestation about policy ideas in terms of policy paradigms affects decision-maker’s options and strategies in the policy-making process and eventually results in stability or (incremental) policy change. The core argument this article developed is that policy-makers’ repertoire of legitimating discourses, which they can strategically apply to legitimate their policy choices and influence the decision-making process amidst conflicting demands (see Table 4), is more extensive when a policy domain is characterised by a paradigm mix. A typology of three different paradigm situations (paradigm dominance, paradigm contestation and paradigm mixes) was introduced, and connected to these different situations a distinction was made between three discursive strategies: paradigm stretching, banking on inconsistencies and a commensurability strategy. The case analysis of the Commission’s legitimation of the introduction and development of direct income payments shows that between 1992 and 2013, the CAP has shifted from a situation of paradigmatic dominance of the dependent agriculture paradigm, to one of paradigmatic contestation and a paradigm mix, including all three paradigms. The discursive strategies the Commission applied to maintain the legitimacy of the direct payments instrument have evolved in line with the expectations, showing a trend towards banking on inconsistencies and commensurability framing (see Table 5). While the ideational development of the CAP towards a paradigm mix with continuing paradigmatic contestation has provided the Commission with a broad array of discursive strategies to legitimate its policy choices, the policy inconsistencies and gap between words and deeds this has resulted in – particularly with respect to the policy’s environmental objectives – are now posing a challenge for the Commission to develop a discourse that convinces a sufficient number of policy actors to continue supporting the CAP.

Table 4 Interests, positions and arguments of Council, European Parliament (EP) and interest groups

Note: CAP=Common Agricultural Policy.

Table 5 Commission’s discursive strategies in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reform debate

Note: DA=dependent agriculture; CA=competitive agriculture; MF=multifunctional agriculture.

The empirical analysis also shows that the Commission’s application of discursive strategies is not enough to ensure the adoption of its preferred policies, particularly in the event of powerful actors with opposing interests. Member state and farm organisations’ interests and demands thus repeatedly watered-down the Commission’s reform efforts. However, the Commission was nonetheless able to shape the reform debate and its outcome, parts of which were against member states’ preferences. Whether reflecting its genuine ideas or merely strategies to further its preferences, the Commission’s usage of commensurability framings helped shape the policy outcome by affecting interest perceptions and providing a mix or variety of rationales for the policy that member states could in turn apply towards domestic audiences (see, e.g. Alons and Zwaan Reference Alons and Zwaan2016, for member state strategies when selling the 2013 reform domestically).

To what extent are the advantages of paradigm mixes in terms of discursive strategies also applicable to other domains than agricultural policy and in other institutional settings than the EU? It is likely that in any domain with competing paradigms without a single dominant one or with varying dominance – be it environmental or monetary policies, for example – similar dynamics will be at play. How these dynamics will play out exactly, however, will be affected by the institutional context, which may not only vary from country to country, but also from policy domain to policy domain within a single country. In this respect, monetary policies are developed within a relatively insulated policy network in the EU, while the environmental policy network is open to the input of a broad range of actors, for example. Paradigm mixes are more likely to surface as a policy outcome in political institutions or countries where decision-making authority is more diffused and decentralised among multiple veto-actors in the policy process (such as in the EU) than in single-veto actor systems, such as the UK. When there are more veto-players, paradigmatic contestation will more easily lead to policy compromises with elements that are based on a paradigm mix (see also Princen and van Esch, Reference Princen and van Esch2016, 361, who claim single paradigms are less likely in such systems). But what if paradigm mixes are found in single-veto actor systems? While it would in theory create similar potential discursive opportunities, these are more likely to be used in deliberations within the executive or insulated policy network rather than in the discourse aimed at a wider group of political actors, as there are no political veto players that need convincing in order to obtain the policy outcome. How the effect of paradigm mixes on discursive strategies exactly plays out in single-veto actor systems as well as in other empirical domains thus remain important empirical questions for future research.

Data Availability Statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.

Funding

This project has received funding from the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 659838.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback on earlier versions of this article.