1. Introduction

The rise of Asia has galvanized pivotal changes to the international economic order in the post-World War II era. Amid ascending trade protectionism and the COVID-19 pandemic, Asian countries have become the engines of global regionalism and have propelled the shift of the commercial centre of gravity to the region. By 2050, more than half of global gross domestic product (GDP) will arise from Asia, enabling it to gain the dominant economic status that it possessed before the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 1

Tellingly, China is expected to replace the United States as the world's largest economy in the next decade.Footnote 2 As a ten-country bloc, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will ascend to the equivalent of the fourth largest economy.Footnote 3 The six ‘ASEAN Plus One’ free trade agreements (FTAs) with Asia-Pacific economies have underpinned the legal regimes of new Asian regionalism.Footnote 4 The ASEAN-centred framework further led to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is now the world's largest FTA by economic scale and includes 15 partners such as China, Korea, and Japan. This mega-regional trade agreement accounts for 30% of global GDP and 26.2% of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows.Footnote 5 Facing a substantial decline of trade and investment due to the pandemic, the RCEP manifests Asia's normative response to economic recovery and future development.Footnote 6

Like trade law, investment law forms an integral part of international economic law and is critical to the sustainable growth of developing countries. The lack of consensus among World Trade Organization (WTO) members removed investment from the WTO Doha agenda.Footnote 7 The scope of current WTO negotiations on ‘investment facilitation for development’ is limited and excludes core issues of investment liberalization and protection.Footnote 8 As investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) has encountered massive backlash, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) entrusted Working Group III to discuss procedural reforms for ISDS under investment treaties.Footnote 9 At these multilateral forums, Asia has yet to form a unified group to advance common positions.Footnote 10 It is therefore vital to explore Asian states' agendas on investment law at the regional and national levels to understand the Asian approaches to investment reforms.

The article reinforces the theme of this special issue and fills a gap in the existing literature by providing the most up-to-date and comprehensive account of Asia's investment rulemaking approach in light of domestic legislative changes and regional trade strategies. It argues that normative developments of ASEAN and the RCEP represent the Asian way of pragmatic incrementalism in reforming investment law. The practice of these member states has energized the new trend of ‘domesticating’ international economic law. The cross-fertilization between regional and national investment regimes also ensures the parallel development of the two regimes.Footnote 11

The neoliberal assumption that prioritizes internationalism based on multilateral efforts no longer dominates national economic policies. ASEAN and RCEP countries demonstrate the changing priority of regional and national approaches. In practice, modern provisions of regional agreements have often been incorporated into domestic investment and dispute settlement laws, which in turn shape prospective bilateral and regional investment pacts. Asian states' experiences therefore provide valuable lessons and the impetus for the Global South to consider alternative models to the Washington Consensus.Footnote 12

Following the introduction, Section 2 examines the economic and geopolitical context of investment rulemaking in new Asian regionalism that has developed in the third wave of global regionalism. It sheds light on paradigm changes to contemporary Asia-Pacific FTAs and bilateral investment treaties (BITs), as well as domestic investment laws in selected countries. Section 3 analyses the legal framework of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) with a focus on the bloc's new investment rules, as well as the successive package structure for services commitments on foreign equity restrictions pertinent to Mode 3-related FDI. It also discusses ISDS mechanisms under ASEAN's internal and external agreements.

Section 4 assesses the RCEP's evolution, as well as its core investment and services rules that reflect the new consensus of Asia-Pacific countries. Furthermore, it provides insight into legal options which emerged as a result of the RCEP's omission of ISDS and potential treaty-shopping problems under overlapping agreements. Asian countries' ISDS reform proposals for UNCITRAL Working Group III will also be examined. Section 5 highlights investment and dispute settlement reforms by explaining new designs of international investment agreements (IIAs) and domestic arbitration and court rules that complement the liberal international order. Section 6 outlines investment reforms in new Asian regionalism and the implications for the Global South.

2. New Asian Regionalism and the Liberal International Order

It is imperative to contextualize Asia's changing regulatory frameworks for investment. There have been three waves of global regionalism since World War II. After the first wave occurred in the 1950s and 1960s, the second wave dominated economic integration in the 1980s and the 1990s. The world is now confronting the third wave that has evolved since 2000. New Asian regionalism in the latest wave of global regionalism has had a profound impact on the international investment regime. After World War II, the ‘US-led liberal hegemonic order’ became the dominant force that led to the Bretton Woods system.Footnote 13 To follow ‘embedded liberalism’, Asian countries have been rule-takers rather than rule-makers.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, the 1997 Asian financial crisis prompted paradigm shifts.

New Asian regionalism that developed in the latest wave of global regionalism has propelled the evolution of regional investment rules in tandem with the domestication of such rules. Do these developments challenge the liberal international order? From the geopolitical perspective, the challenge arguably lies in the transformation of rulemaking power from the trans-Atlantic alliance to trade blocs in Asia. From the normative aspect, intertwined regional and national investment reforms have enriched rather than undermined the liberal international order and allowed states to regain additional power to enforce regulatory changes.

2.1 Earlier Waves of Global Regionalism

Jagdish Bhagwati coined the term ‘First Regionalism’, which denotes proliferating FTAs in the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 15 During this era, political considerations dominated the process of regionalism. On the one hand, the United States was reluctant to pursue trade pacts under Article XXIV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) because leaders ‘remained wedded to multilateralism and nondiscrimination in trade liberalization through the Kennedy Round’.Footnote 16 On the other hand, Washington eagerly supported the founding of the European Economic Community, as it could prevent another French–German war and counterbalance Soviet influences.Footnote 17 In Asia, the creation of ASEAN in 1967 marked the prelude to Asian regionalism.Footnote 18 ASEAN was predominantly politically oriented. The initial goal of Southeast Asian states was to forge a loose security alliance against communist expansion.Footnote 19 Akin to Bhagwati's observation that most economic initiatives in the era failed due to political interventions, ASEAN's trade-creation effect was marginal.Footnote 20

The First Regionalism transformed investment agreements from the infant to mature stages and exposed Asian states to the normative demands of the West.Footnote 21 At the outset, US Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation (FCN) Treaties incorporated investment issues.Footnote 22 The 1946 US–Republic of China FCN Treaty is illustrative.Footnote 23 The Treaty covered investment provisions on ‘the full protection and security required by international law’ and ‘prompt payment of just and effective compensation’ following expropriation.Footnote 24 The key difference between FCN Treaties and modern IIAs is the former's lack of detailed enforcement procedures for state-to-state disputes and the absence of ISDS provisions.Footnote 25 As the first investment agreement with ISDS, the 1968 Netherlands–Indonesia BIT enabled investors to sue the host state.Footnote 26 Claims could be brought to the Center created under the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID Convention).Footnote 27

Even before the birth of ASEAN, the Asian regionalism idea emerged at the 1955 Indonesia-hosted Bandung Conference, in which anticolonial nationalism of Asian–African states elevated the Non-Aligned Movement.Footnote 28 These countries' economic objective was confined to the nationalistic notion of self-help, which sought to minimize reliance on the Global North.Footnote 29 In the 1970s, Non-Aligned Movement members joined the Group of 77 in passing the United Nations resolutions for establishing ‘a New International Economic Order (NIEO)’.Footnote 30

The NIEO principles championed absolute sovereignty over economic activities and natural resources independent of foreign control. They stressed that states are entitled ‘[t]o nationalize, expropriate or transfer ownership of foreign property’ with ‘appropriate compensation’ and that disputes should be settled under domestic laws and courts.Footnote 31 The NIEO compensation standard departed from the Hull formula, which was adopted in the United States, of according ‘prompt, adequate and effective’ compensation and deprived investors' remedies before international tribunals.Footnote 32 Capital-exporting countries rejected these demands. The NIEO movement waned quickly. The Bretton Woods institutions and new BITs reinforced the Washington Consensus and compelled the Global South to engage in free trade and investment defined by the trans-Atlantic alliance.Footnote 33

In the 1980s and 1990s, the second wave of global regionalism surfaced during the Uruguay Round. Bhagwati highlighted that the European Union (EU) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the precursor to the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), marked the success of the ‘Second Regionalism’.Footnote 34 Richard Baldwin explained the ‘domino theory’, which posits that the driving force for regionalism is non-FTA members' motivation to pursue trade agreements to maintain export advantages.Footnote 35

Asia's most noteworthy trade initiatives were ASEAN and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). As the domino theory predicted, the EU and NAFTA energized ASEAN to build the ASEAN Free Trade Area to accelerate internal integration.Footnote 36 Unlike ASEAN, APEC is a dialogue forum that operates on n–on-binding rules and decisions. The APEC Non-Binding Investment Principles demonstrate 21 members' desire to construct common investment standards, albeit on a soft-law basis.Footnote 37 Given different rules for expropriation and compensation under constitutional and national laws, the APEC Principles guide regional and international standards.

In the ‘Second Regionalism’, Asia was in line with global trends where IIAs and ISDS cases radically proliferated.Footnote 38 Also, Asian countries' frustration with US-led monetary institutions' responses to the Asian financial crisis prompted the signing of the ‘ASEAN Plus Three’-based Chiang Mai Initiative.Footnote 39 This framework subsequently extended to trade and investment arenas and enlarged to ‘ASEAN Plus Six’ members, including Australia, India, and New Zealand as additional members. This 16-party framework has revolutionized Asia's approach to investment rulemaking.

2.2 Third Regionalism

Building on Bhagwati's observations, I refer to the most recent wave of global regionalism as the ‘Third Regionalism’, which has evolved in tandem with the Doha Round since the 2000s. New Asian regionalism and the Third Regionalism are cross-fertilizing. As an integral part of the Third Regionalism, new Asian regionalism provides the economic and geopolitical context for trade pacts in Asia. As de-globalization resulted in backlash against Bretton Woods institutions, the current era is witnessing the trend toward ‘domesticating’ international economic law. As the introductory article and the special issue aver, developments in new Asian regionalism demonstrate that the domestication of investment rules by no means abandons normative values of international economic law. This process instead creates an alternative impetus for reinforcing the neoliberal order by accelerating the cross-fertilization between regional and national investment laws. Markedly, there are three unique characteristics of current FTAs and BITs that distinguish them from their counterparts in the earlier two waves of global regionalism.

First, mega-regional and comprehensive trade agreements are the defining features of the Third Regionalism. As the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the RCEP exhibit, these pacts involve a significant number of countries with massive economies of scale. Based on their collective GDP, the RCEP, the USMCA, the post-Brexit EU, and the CPTPP are the world's top four trading blocs.Footnote 40 In particular, the RCEP strengthens ‘ASEAN centrality’ and shows developing countries' activism in advancing their own trade agendas in response to the US–China trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 41

Moreover, it has become the norm for mega-FTAs and other trade agreements to cover WTO-extra and plus commitments. Recent agreements no longer solely focus on tariff and services liberalization. The comprehensiveness of FTAs can be judged by their WTO plus and extra provisions.Footnote 42 The dichotomy between FTAs and BITs became blurred because the former often incorporates the investment chapters. As of 2021, the number of these IIAs that include FTAs and BITs that govern investment liberalization and protection has increased to 2,558.Footnote 43

Second, countries have increased the scope of investment liberalization under their investment laws or legislation on special economic zones (SEZs) and free trade zones (FTZs). The practice of ASEAN and RCEP members showed that domestic investment rules led to higher levels of investment liberalization than those of commitments under FTAs and BITs. These investor-friendly schemes, which have in turn influenced IIAs, evidence that countries' ‘unilateral acts’ fortify mutually reinforcing regional and domestic investment regimes.Footnote 44

To illustrate, Singapore attracts the most FDI inflows to ASEAN.Footnote 45 According to the typology developed in the introductory article, Singapore is a jurisdiction that does not have specific legislation on investment.Footnote 46 Laws of general application including contract and company laws govern foreign investment.Footnote 47 Yet, sectoral laws such as the Residential Property Act, the Newspaper and Printing Act, and the Banking Act include restrictions on foreign ownership and vigorous licensing regimes.Footnote 48 Moreover, Singapore's nine FTZs provide beneficial customs and tax treatment to firms that engage in ‘entrepot trade and transshipment activities’.Footnote 49 Going beyond economic incentives in its SEZs, China experienced the ‘pre-establishment national treatment’ model and deregulated market access procedures in the Shanghai Pilot FTZ and the Hainan Free Trade Port.Footnote 50 These reforms were incorporated into China's recent IIAs and 2019 Foreign Investment Law.Footnote 51

As core ASEAN and RCEP members, Vietnam and Indonesia have also become magnets for FDI. Similar to China, foreign investments are governed by separate rules in these two countries. Vietnam has yet to ratify its SEZ law due to protests against China's escalating influence for capital and investment in the region.Footnote 52 However, the 2020 Law of Foreign Investment signifies a milestone, as it was the first time for Vietnam to shift from the positive list to the negative list approach to market access.Footnote 53 Decree 31 clarifies the implementation of the new law by stipulating the negative lists, including the Prohibited List and the Market Entry List.Footnote 54 The sectors listed in the former are closed to foreign investment, whereas those listed in the latter permit foreign investment subject to conditions determined by ministries.Footnote 55 Foreign investments that fall outside the negative lists are thus accorded national treatment.Footnote 56 These domestic reforms have developed in tandem with Vietnam's commitments under the CPTPP and the EU–Vietnam FTA. The gap between FTA provisions and Vietnamese laws continues to exist in areas such as non-tariff barriers to investment in the renewable energy sector, financial and telecommunications services, and requirements pertaining to the entry and stay of foreigners.Footnote 57 These impediments should be further remedied in order to facilitate FDI.

Indonesia's 2007 Investment Law applies to both domestic and foreign investors, but the restrictions on foreign investment are consolidated in the negative-list Presidential Regulation.Footnote 58 Notwithstanding the government's termination of BITs, Indonesia follows the trend of investment liberalization in domestic laws. Enacted in 2021, the New Investment List amended the 2007 Investment Law and reduced the number of prohibited business fields for FDIs from 20 to 6 and removed the 67% foreign equity limitations on key sectors such as telecommunications and media.Footnote 59 Moreover, current foreign ownership restrictions do not apply to foreign investors entitled to more favorable treatment under applicable IIAs and businesses in Indonesia's SEZs.Footnote 60 These new-generation domestic investment rules mark the feature of the Third Regionalism, as they demonstrate developing countries' new investment rulemaking approaches.

Finally, while IIAs continue to grow, the number of new agreements has gradually declined since 2008 due to ongoing reforms associated with the ascending number of ISDS disputes.Footnote 61 Other than the multilateral forum of the UNCITRAL, states have resorted to national, bilateral, and regional strategies to implement their agendas.Footnote 62 Among Asian countries, India and Indonesia encountered the most ISDS claims, thus expediting those governments' ISDS reforms.Footnote 63 India lost the case of White Industries where an Australian company challenged delays in India's judicial system.Footnote 64 The Tribunal relied on the most-favoured-nation (MFN) clause of the Australia–India BIT and found that India violated the obligation under the India–Kuwait BIT to ensure an ‘effective means of asserting claims and enforcing rights’.Footnote 65 This decision was seen as an attack on judiciary sovereignty and led to India's new 2016 Model BIT that omits the MFN provision and vastly restricts access to ISDS.Footnote 66

Churchill Mining and Planet Mining also changed Indonesia's stance on ISDS. Churchill Mining, a United Kingdom (UK)-listed company, and Planet Mining, an Australian subsidiary, sought damages for more than US$1 billion after Indonesia's provincial government revoked their mining licenses for a coal project.Footnote 67 The two companies resorted to ICSID arbitration based on Indonesia's BITs with the UK and Australia. In the consolidated proceedings, the Tribunal rejected Indonesia's jurisdictional challenges by holding that Jakarta had ‘consented’ to ICSID arbitration under respective BITs.Footnote 68 Subsequently, Indonesia announced its intention to terminate all 67 BITs.Footnote 69 The government has terminated more than 30 BITs.Footnote 70

Following these disputes, the case of Philip Morris fundamentally changed investment rulemaking in Asia. In this case, the US company, Philip Morris, challenged Australia's plain cigarette packaging legislation intended to reduce smoking.Footnote 71 The company was unable to resort to the Australia–US FTA that lacks ISDS provisions. Nonetheless, corporate restructuring followed by treaty shopping enabled the company's Hong Kong subsidiary to resort to the Australia–Hong Kong BIT.Footnote 72 According to the Tribunal, ‘this arbitration constitutes an abuse of rights’ because the dispute was foreseeable to Phillip Morris at the time of the restructuring.Footnote 73 Notwithstanding the Tribunal's decision in favour of Canberra, ISDS became widely criticized for resulting in skyrocketing legal costs and creating a ‘regulatory chill’ that makes public policy measures vulnerable to foreign investors' legal challenges.Footnote 74 The case of Philip Morris resulted in the tobacco carve-out clause of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Australia–Singapore FTA.Footnote 75 The CPTPP takes a further step to confine the ISDS application.Footnote 76

These ISDS reforms are critical to investment rulemaking in the Third Regionalism and propel Asian countries to resort to regional and domestic schemes for potential disputes. As the introductory article suggests, the domestication of international investment law also incorporates a new trend for domesticating international dispute settlement. For instance, Indonesia's termination of BITs enabled ASEAN's internal and external agreements to function as the primary avenues by which foreign investors bring ISDS claims against the country. With financial resources and sophisticated jurists, Singapore has revamped its courts and arbitral institutions to allow ISDS cases arising from BITs or ASEAN agreements to be handled by domestic mechanisms.

3. Investment Regime of the ASEAN Economic Community

The creation of the AEC in 2015 marked a milestone after the ASEAN Charter conferred legal personality on the association ‘as an inter-governmental’ organization.Footnote 77 In response to the unsatisfactory ASEAN Free Trade Area and the Asian financial crisis, the AEC forms one of the three pillars of an ASEAN Community.Footnote 78 The new AEC Blueprint 2025, which succeeded the AEC Blueprint 2015, is an integral part of the guiding document of ‘ASEAN 2025: Forging Ahead Together’.Footnote 79 The first and foremost characteristic of the AEC Blueprint 2025 is ‘A Highly Integrated and Cohesive Economy.’Footnote 80 Its key target is to ‘establish a more unified market’ by facilitating ‘the seamless movement of goods, services, investment, capital and, and skilled labour’.Footnote 81

3.1 Changing ASEAN Way

The AEC and ASEAN Plus One FTAs reinforced the concept of ASEAN law and restructured the so-called ASEAN way. Based on the Indonesian concepts of musyawarah and mufakat (consultations and consensus), the ASEAN way refers to the collective principles of sovereignty, non-interference and consensus in decision-making.Footnote 82 In practice, it has functioned as the code of conduct in inter-state interactions and the decision-making process for reaching consensus by consultations.Footnote 83 The ASEAN way contributed to the founding of ASEAN and elevated the bloc to the centre of new Asian regionalism under the legal approach of pragmatic incrementalism. I contend that the legalization of the AEC has galvanized the ASEAN way to be a hybrid political and legal notion. It is no longer accurate to deem the ASEAN way as a non-binding soft law approach to regionalism. Instead, the new ASEAN way has signified its hard-law obligations with structured flexibility.Footnote 84

The ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA) is the key instrument for investment liberalization and protection under the AEC Blueprint 2025. During the Third Regionalism, ASEAN's FDI inflows have soared more than six-fold and the value of FDIs constitute 21% of FDI stock in developing countries.Footnote 85 ASEAN also overtook China in attracting FDI.Footnote 86 Signed in 2009, the ACIA merges the 1987 Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments and the 1998 Framework Agreement on the ASEAN Investment Area. These pre-ACIA agreements and their amending protocols failed to generate the expected impact. The 1987 Agreement was comparable to conventional BITs that lack investment liberalization.Footnote 87 Given its exclusion lists, the 1998 Framework Agreement was unable to enable ASEAN to recover from the Asian financial crisis. Hence, the ACIA aims at ‘progressive liberalization’ of existing restrictions and strengthens investment protection and transparency of investment rules.Footnote 88

Notwithstanding the absence of EU law-like direct effect, the ACIA facilitates the harmonization process of domestic investments laws in the ten ASEAN countries and provides best practices for investment reforms. While de-globalization may have undermined the effectiveness of multilateral institutions, the domestication of international economic law has reinforced the mutual relationship between regional and national investment regimes. In particular, new investment laws in Laos and Myanmar evidence the ACIA's normative impact.Footnote 89 Laos' 2009 Law on Investment Promotion and its 2016 amendments apply to both domestic and foreign investments and brought national standards much closer to ACIA requirements.Footnote 90 However, as the investment law merely addresses non-discrimination without clear-cut national treatment and MFN provisions, the ACIA and Laos’ IIAs remain ‘safe choices’ for foreign investors.Footnote 91 Myanmar's 2016 Investment Law and 2017 Investment Rules represent the country's latest efforts to modernize the domestic investment regime.Footnote 92 New provisions incorporate key features of the ACIA including the single reservation list, as well as national treatment and MFN clauses.Footnote 93 Even after the coup, the military government has continued the operation of the Myanmar Investment Commission and has yet to change the investment legal framework.Footnote 94

The ACIA applies to ASEAN investors and investments and demonstrates Asia's evolving rulemaking in investment law. While investors denote natural and juridical persons, a non-ASEAN enterprise can be entitled to the ACIA's benefits and protection if the company is incorporated and maintains ‘substantive business operations’ in an ASEAN country.Footnote 95 Influenced by the US Model BIT, the ACIA adopted a broad, non-exhaustive and asset-based definition of investments that encompasses ‘every kind of asset’.Footnote 96 To prevent proliferating claims, the ACIA excludes assets that lack ‘the characteristics of an investment’.Footnote 97

3.2 Investment/Services Liberalization and ISDS Issues

Paramount to investors, investment liberalization under the ACIA governs five main sectors (agriculture, fishery, forestry, manufacturing and mining and quarrying) and service sectors incidental to these main sectors.Footnote 98 The original ACIA included a single, negative-list annex that covers states' existing and future non-conforming measures in the liberalized sectors.Footnote 99 The Fourth Protocol broadened the liberalization scope by changing a single annex to two-annex negative lists.Footnote 100 ASEAN members are obliged to indicate their current non-conforming measures in the first index and schedule reservations for future measures in the second index.Footnote 101 This new modality increases transparency for investors.

Investment liberalization under the ACIA closely links to services-related rules of the ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement (ATISA), which consolidates successive packages of services commitments under the 1995 Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS).Footnote 102 Schedules of services commitments completed under various rounds of negotiations cumulatively ‘form an integral part of’ the AFAS.Footnote 103 Due to the AFAS's non-self-executing nature, each package of commitments will take effect after domestic ratification procedures. The unique package structure illustrates ASEAN's pragmatic incrementalism, as ASEAN states could facilitate gradual domestic legal reforms under AFAS packages that eventually led to higher-level ATISA commitments.

Comparable to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), AFAS commitments encompass four modes of services.Footnote 104 Mode 3 (commercial presence) directly relates to FDIs because countries’ commitments liberalize foreign equity restrictions in services sectors. For instance, seven ASEAN states committed to allowing for 100% foreign ownership in the hospital services sector, but Indonesia, Myanmar and Thailand kept the 70% benchmark.Footnote 105 The ATISA will shift the AFAS' positive-list modality to the more progressive negative list approach that obliges all services sectors to be liberalized unless otherwise specified in the schedules.

As three ASEAN members – Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam – are yet to join the ICSID Convention, the ACIA including ISDS plays a key role in investor–state disputes. Akin to the US Model BIT and the NAFTA, the ACIA goes beyond traditional BITs by incorporating more detailed arbitration procedures than those of the ICSID Convention.Footnote 106 As a key issue of investment reforms, the interpretation of fair and equitable treatment (FET) has resulted in long-standing controversies in ISDS cases. Myanmar is the only ASEAN country that includes FET in domestic investment law, but its scope of FET is narrower than that of most IIAs.Footnote 107 Case law suggests that FET ‘has turned into an all-encompassing provision’, which permits investors to utilize IIAs to challenge government actions they consider ‘unfair’.Footnote 108

The ACIA strikes a balance between domestic law and conventional BITs. It provides ‘greater certainty’ of FET, by preventing the host country's denial of justice and according to the investors due process ‘in legal and administrative proceedings’.Footnote 109 To safeguard regulatory sovereignty, the MFN clause of the ACIA also excludes ISDS proceedings.Footnote 110 Arguably, based on the best practices of domestic laws, the ACIA's denial of benefits provisions that exclude certain investors from the agreement further diminish treaty shopping.Footnote 111 Comparable provisions are incorporated into ASEAN Plus One FTAs.Footnote 112

4. RCEP: Forging Asia's New Consensus in Investment Law

While being the world's largest FTA by economic scale, the RCEP has been inaccurately portrayed as a China-led trade pact.Footnote 113 In reality, RCEP negotiations were initiated and led by ASEAN. RCEP parties including China recognize the RCEP's role in reinforcing the ‘ASEAN centrality in regional frameworks’.Footnote 114 Complementing the AEC, the RCEP consolidates ASEAN Plus One FTAs and ushers the ASEAN way into hard-law rules with structured flexibility. The RCEP's revolution reinforces my AEC analysis because their approaches reflect Asia's legal approach of pragmatic incrementalism, which diverges from the neoliberal model of the Global North.

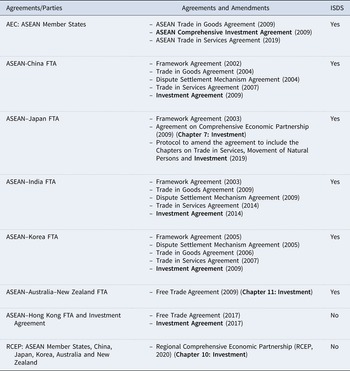

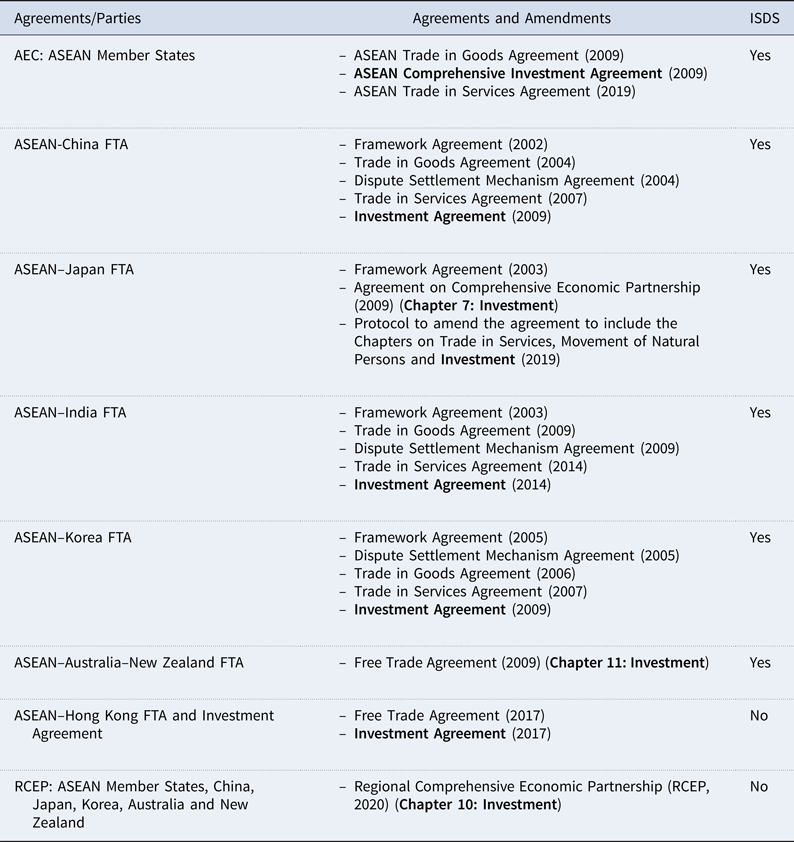

The RCEP demonstrates Asian countries' efforts to regionalize their domestic investment reforms that the ACIA and other IIAs have influenced. The RCEP's omission of the ISDS scheme also propels the domestication of international dispute settlement mechanisms. As Table 1 below demonstrates, the RCEP reflects Asia's new consensus of investment reforms incrementally forged under ASEAN's internal and external agreements.Footnote 115 Their shared characteristics crystallize the normative development of investment rulemaking in new Asian regionalism.Footnote 116 Hence, these characteristics support and shed new light on the observation of the introductory article concerning the changing relationship between domestic and international economic laws. They exhibit Asian countries' collective response to de-globalization by preserving normative value of international economic law in regional pacts, thus mutually reinforcing investment regimes at regional and national levels.

Table 1. ASEAN-Based Agreements Including Investment Rules

Source: Elaborated by the author from public sources.

4.1 Core Investment Rules and Commitments

Since the inception of the Third Regionalism, Beijing and Tokyo proffered different proposals for Asian regionalism.Footnote 117 APEC's proposal for the 21-member Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) and the Obama Administration's accession to TPP negotiations further complicated roadmaps to Asian integration.Footnote 118 In 2011, ASEAN ‘ended the debate by proposing its own model’, known as the RCEP, which would be a pathway to the FTAAP alternative to the TPP.Footnote 119

Parties to the ASEAN Framework for the RCEP acknowledged the RCEP as ‘an ASEAN-led process’.Footnote 120 According to the Guiding Principles and Objectives for the RCEP, ASEAN Plus Six leaders agreed to merge prior Chinese and Japanese proposals.Footnote 121 Trump's decision to withdraw the United States from the TPP, US–China trade tensions and the COVID-19 pandemic expedited RCEP negotiations. Despite India's decision to opt out of RCEP talks in 2019, the remaining 15 RCEP parties signed this mega-FTA in 2020.Footnote 122

The CPTPP, which was concluded under Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's leadership in 2018, and the RCEP are now the most noteworthy mega-FTAs. The formal applications of the UK and China in 2021 to join the CPTPP and the intentions of Hong Kong and Bangladesh to accede to the RCEP indicate the potential expansion of these two pacts and their global impact.Footnote 123 By restructuring regional value chains in the Asia-Pacific, the RCEP will advance the ‘Global ASEAN’ agenda under the AEC Blueprint 2025 and China's FTA strategy based on its Belt and Road Initiative.Footnote 124

While the COVID-19 pandemic caused the contraction of global FDI by 35%, China played a major role in contributing to Asia's 4% FDI growth.Footnote 125 Transforming into a capital-exporting economy has influenced the normative shaping of third and fourth-phase Chinese BITs and the RCEP.Footnote 126 Beijing's earlier BITs echo its 1993 reservation to the ICSID Convention that confines an arbitral tribunal's jurisdiction to ‘compensation resulting from expropriation and nationalization.’Footnote 127 The 2015 Australia–China FTA's notable expansion of the ISDS application to cover breaches in national treatment obligations evidence China's investment rule-making in tandem with the global trend to widen the ISDS application.Footnote 128

The RCEP represents the new breakthrough to China's economic reform. Thirty-seven areas of China's investment liberalization under the RCEP exceed its WTO commitments.Footnote 129 More importantly, the RCEP marks Beijing's first application of the ratchet mechanism that disallows parties to change back to more restrictive forms.Footnote 130 China also agreed to extend national treatment to pre-establishment investment, which was rarely included in recent BITs and was primarily implemented in free trade zones or ports.Footnote 131 Although Beijing did not assert a leadership role in forging the RCEP's investment rules, these changes make the position of China more in line with that of developed Asian partners such as Japan and Korea.

The RCEP and the ACIA include common core pillars of investment protection, liberalization, promotion, and facilitation. However, qualifying provisions indicate the RCEP's more cautious approach and reflect its pro-development focus.Footnote 132 The RCEP adopted the ACIA-like asset-based definition of investment but incorporated country-specific restrictions. For Cambodia, Indonesia and Vietnam, the provisions that require covered investment to be ‘admitted’ denotes that it ‘has been specifically registered or approved in writing, as the case may be’.Footnote 133 The requirement thus buttresses the relationship between regional and domestic investment rules, given that the application of RCEP provisions will be conditional on national registration and approval procedures. In addition, an investor can be a juridical person, but its branch is excluded from having ‘any right to make any claim against any’ RCEP party.Footnote 134 In light of investment reforms, the RCEP mandates that FET and full protection and security be interpreted according to the ‘minimum standard of treatment of aliens’ under customary international law.Footnote 135 Akin to the ACIA, the RCEP and its annex also detail conditions and compensation for direct and indirect expropriation.Footnote 136 These reform elements of the RCEP will harmonize Asian countries' investment rulemaking approaches.

RCEP parties scheduled their services and investment commitments in Annexes II and III. As for the modality of these commitments, the positive list approach allows states to retain regulatory sovereignty because they liberalize only the sectors indicated in their schedules. As all sectors are to be liberalized unless otherwise indicated, the negative list approach is usually more aggressive and automatically covers newly developed areas. Distinct from the GATT, the AFAS, and ASEAN Plus One FTAs, the RCEP adopted the hybrid model for services commitments. Eight parties used positive list scheduling under Annex II and seven parties followed the negative list approach by including their reservations and non-conforming measures in Annex III.Footnote 137

The flexibility under the RCEP well illustrates pragmatic incrementalism. States that chose the positive list approach for services commitments will be required to transition to negative list scheduling in six years after the RCEP enters into force, but a 15-year transition period is accorded to three least developed ASEAN countries.Footnote 138 RCEP services commitments are also vital to foreign equity restrictions that involve Mode 3-related FDI in the Asia-Pacific. To illustrate, RCEP members committed to liberalizing foreign ownership limits for at least 65% of sectors such as telecommunications and financial services industries.Footnote 139

Unlike the hybrid approach for services commitments, RCEP members scheduled their negative-list market access commitments for investment in Annex III.Footnote 140 Similar to the ACIA Fourth Protocol, RCEP members specified their non-conforming measures that exclude or limit foreign investment in List A and their reservations for potential discriminatory measures in List B.Footnote 141 Significantly, the ratchet clause of the RCEP applies to both services and investment so that 15 members ‘commit to automatically extend the benefits of any future’ agreements to all other parties.Footnote 142 Hence, the clause propels the RCEP to stay as ‘the best deal’ for companies and governments.

4.2 Absence of the ISDS Mechanism and Legal Implications

ISDS has been the key focus in investment forums in new Asian regionalism. While the ACIA, the CPTPP and ASEAN Plus One FTAs follow US-style ISDS, an emerging trend is to replace ISDS with recourse to state courts and state-to-state proceedings.Footnote 143 Recent IIAs such as the ASEAN–Hong Kong Investment Agreement, the UK–Japan FTA, and the EU–China Comprehensive Investment Agreement contain no ISDS mechanism, and instead articulate that pertinent rules will be subject to subsequent negotiations.Footnote 144 The RCEP follows a similar approach. Article 10.18 mandates that parties commence negotiations for ISDS, as well as the application of expropriation rules to taxation measures, within two years after the RCEP becomes effective and that they conclude the talks in three years.Footnote 145

It is decisive to understand the rationale for RCEP parties' changing positions on the inclusion of the ISDS. At the inception, the RCEP's 2012 Guiding Principles and Objectives highlighted the significance of investment protection.Footnote 146 In 2015, RCEP parties agreed to encompass ISDS provisions.Footnote 147 Although Japan and Korea pushed for detailed ISDS rules during negotiations, other countries and the CPTPP development prompted the RCEP to discard ISDS.Footnote 148 Other than the CPTPP's suspended clauses that circumscribe the ISDS ambit of the original TPP, some countries' side letters exclude ISDS entirely.Footnote 149 Thus, the RCEP parties decided to discuss ISDS as part of the future work program so that ISDS issues will not hamper the signing of the mega-pact.

The specific exclusion of pre-establishment rights from dispute settlement under Article 17.11 also suggests RCEP parties' intention to fall back on state-to-state dispute procedures to deal with investment matters.Footnote 150 To curtail the recourse to other FTAs or BIAs that provide more favourable procedures, the RCEP excludes ‘any international dispute resolution procedures or mechanisms under other existing or future international agreements’.Footnote 151 Moreover, based on the model of ASEAN Plus One FTAs, the RCEP affirms ‘existing rights and obligations’ arising from other agreements.Footnote 152 This co-existence approach manifests that RCEP members are still entitled to investor–state and state–state arbitration under current IIAs such as ASEAN Plus One FTAs among the disputing parties.Footnote 153 Markedly, to protect Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, the RCEP stipulates that the parties bringing complaints against these states should ‘exercise due restraint’ and that the panel must identify how special and differential treatment is considered in procedures.Footnote 154

The RCEP's prospective ISDS mechanism will likely result in treaty shopping between applicable agreements. According to Article 30.3 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) on the application of successive treaties, ‘the earlier treaty applies only to the extent that its provisions are compatible with those of the later treaty’.Footnote 155 Nevertheless, this later-in-time rule cannot easily solve the problem. Arguably, Article 20.2 of the RCEP can be interpreted as a special law that overrides Article 30.3 of the VCLT as a general rule. Even assuming the VCLT prevails, various IIAs and RCEP will likely have distinct scopes and carve-outs, making the application of Article 30.3 legally unfeasible.

The normative development of the RCEP represents the Asian way of pragmatic incrementalism in reforming investment law. The future ISDS mechanism of the RCEP should be understood in line with key members' ISDS reform proposals for the UNCITRAL Working Group III. China, Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand stressed their preference for the prevention of disputes.Footnote 156 In particular, Indonesia proposed to condition investors' claims on the exhaustion of local remedies, the government's separate written consent' and mandatory mediation.Footnote 157 Thailand also indicated the importance of exploring the best practice for setting up the domestic mechanism of ISDS management to settle potential disputes.Footnote 158

RCEP members expressed concerns about developing countries' limited capacity in responding to ISDS cases. Thailand and Korea supported the establishments of an advisory centre for investment disputes modeled after the Advisory Centre on WTO Law.Footnote 159 Furthermore, RCEP countries including Japan wish to regulate third-party funding such as imposing disclosure requirements for transparency purposes.Footnote 160 Interestingly, China seems to be the sole RCEP member that indicated interest in setting up a permanent appellate mechanism for ISDS disputes.Footnote 161 As explained below, Singapore and Vietnam are the only two ASEAN states that included such a mechanism in their investment pacts with Brussels. These developments will not only shape the RCEP's ISDS direction, but also fill the gap in the literature that primarily focuses on the RCEP's general dispute settlement mechanism under Chapter 19.

5. New IIAs and Alternative Mechanisms for Dispute Settlement

To understand ASEAN and RCEP strategies toward investment reforms in new Asian regionalism, it is vital to assess key members' changing approaches to IIAs, as well as recent domestic arbitration and court rules for investor–state disputes. Indonesia provides a valuable case study.Footnote 162 In addition to terminating BITs, Jakarta introduced new components into its new agreements, which may serve as models for the Global South. The 2018 Indonesia–Singapore BIT replaced their 2005 BIT, substantially lengthening the cooling-off period in which parties should try to settle disputes via consultations from six months to one year.Footnote 163 This new time frame, which is longer than the three-to-six-month cooling-off periods contained in contemporary BITs, arguably compels investors to treat consultation much more seriously.

Also, the 2019 Indonesia–Australia FTA makes the governments' joint interpretation of provisions at disputes binding on the arbitral tribunal.Footnote 164 This design shifted fundamentally from their 1992 BIT that allows the tribunal to reach its determination regardless of the joint interpretation.Footnote 165 ASEAN states' stances have also influenced ASEAN Plus One FTAs. In the 2019 amendments to the ASEAN–Japan FTA, Indonesia and the Philippines required ICSID arbitration to condition the governments' written consents.Footnote 166 Indonesia's approach may have been based on the ‘best practice’ of the Philippines' ACIA reservation to subject ICSID disputes to ‘a written agreement’.Footnote 167 Indonesia wished to ‘rectify’ the perceived unfairness that it encountered in the Churchill Mining and Planet Mining cases, in which the tribunal ruled against Jakarta's jurisdictional challenges irrespective of its argument for not consenting to arbitration. These developments will have an impact on prospective ISDS provisions of the RCEP.

Singapore and Vietnam have experienced different reforms in their investment pacts with the EU. Integral to its ISDS reforms agenda, Brussels has promoted the Investment Court System (ICS) including an appeals facility for investor–state disputes since 2014.Footnote 168 Akin to the CPTPP, the original text of the Singapore–EU FTA that was completed in 2014 merely indicated a possibility for including an appellate mechanism.Footnote 169 The ICS was incorporated into the EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement.Footnote 170 In response to Opinion 2/15 of the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), EU and Singapore negotiators split the original EU–Singapore FTA into the new FTA and the Investment Protection Agreement (IPA).Footnote 171

The amended EU–Singapore FTA can be understood as an ‘EU-only’ agreement and the IPA is a ‘mixed’ agreement.Footnote 172 Although the European Parliament gave consent to the new EU–Singapore FTA and IPA in 2019, the IPA will only enter into force after the 27 national parliaments of the EU ratify it.Footnote 173 The EU–Vietnam FTA followed the same model, dividing it into the FTA and IPA, which the European Parliament ratified in 2020.Footnote 174 The ICS mechanisms under the two IPAs may influence investment rulemaking in Asia in the future.

A new trend of facilitating domestic regimes to deal with ISDS cases is also in line with the domestication of investment law. This development enriches the liberal international order, as domestic mechanisms complement rather than exclude international counterparts. Markedly, the ACIA enables investors to resort to ICSID rules, regional arbitration centres, or domestic courts and administrative tribunals.Footnote 175 The fork-in-the-road provision excludes resorting to other mechanisms once the disputing party chooses the judicial process.Footnote 176 The RCEP's prospective ISDS rules are expected to follow new developments to accord a greater role to domestic courts and arbitral institutions.

Countries have adopted different strategies to ease concerns about proliferating ISDS claims. Indonesia's termination of BITs indicates its preference over the regional approach that makes the ACIA and ASEAN Plus One FTAs primary channels for disputes. Singapore has accelerated domestic reforms for handling ISDS cases. The Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC) Rules 2016 stipulate an investment treaty as a basis for the SIAC's jurisdiction.Footnote 177 The Singapore International Commercial Court (SICC), which is a general division of Singapore's High Court, was launched in 2015.Footnote 178 As a claim of ‘international’ and ‘commercial’ nature is widely interpreted, the SICC is capable of adjudicating investor–state disputes.Footnote 179 Recent proceedings that involved Sanum Investments and arose from disputes under the China–Laos BIT evidence the roles of the SIAC and the SICC in ISDS claims.Footnote 180 Hence, the Singapore case signifies a new trend of domestic dispute settlement that complements the liberal international order.

6. Conclusion

The economic rise of Asia prompted academic and professional interests in investment rulemaking in Asia. This article aims to fill a gap in the existing literature by deciphering Asia's legal approach of pragmatic incrementalism in the Third Regionalism. In particular, the article highlighted the new trend of domesticating international economic law by demonstrating the mutually reinforcing nature of domestic and regional investment laws.

As the cases of ASEAN and RCEP countries evidence, national investment and dispute settlements rules have not only incorporated but also propelled the best practice of regional agreements. These new developments enrich rather than undermine the liberal international order. Therefore, Asian countries' experiences not only energize investment rulemaking in the region, but also provide valuable lessons for the Global South as a whole.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the funding support by the Korea Foundation and research assistance by Lucas Wong and Chin Dan Ting.