On June 20, 1970, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi issued a farmān (royal decree) to establish through an endowment (waqf) a museum in his former residence, the Marble Palace (Kākh-e Marmar) in Tehran.Footnote 1 In a special ceremony, the deed for endowment (waqfnāmeh) was signed by the shah's minister of court, Asadollāh ʿAlam, and was given to the mayor of Tehran, Gholāmrezā Nikpey, along with the key to the palace.Footnote 2 Six years later, on October 30, 1976, the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum (Muzeh-ye Selseleh-ye Pahlavi) was inaugurated by the shah and Empress Farah, allowing Iranians to observe the purported achievements of the Pahlavi dynasty in the perfect setting; a palace in which both Pahlavi shahs had lived. Indeed, as the press happily reported, on this day “the shah's house became the people's house” (khāneh-ye shāh, khāneh-ye mardom shod).Footnote 3

From the very beginning of Pahlavi rule, state ideologues sought to legitimize the Pahlavi monarchy by connecting it to a glorious historical past. This was seen in the architecture of the era, for example, which saw the construction of numerous neo-Achaemenid buildings in Tehran, and through the coronation of Reza Shah in April 1926, when in a grandiloquent speech Mohammad ʿAli Forughi evoked the legendary kings of the Shāhnāmeh.Footnote 4 Whereas Forughi's speech connected the shah to a mythical past, the coronation paraphernalia, which included the sword of Nader Shah and the armor of Shah Ismail, connected him tangibly to a real and comparatively recent monarchical tradition.Footnote 5 One key strategy employed by the Pahlavi state in its efforts to establish a homogenized national ethos centered around the rich cultural heritage of Iran was the initiation of sites of collective remembrance, or lieux de mémoire. As Pierre Nora explains, lieu de mémoire refers to any considerable entity “which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community.”Footnote 6 The Society for the National Heritage of Iran (Anjoman-e Āsār-e Melli-ye Irān), founded in 1922, was active throughout this period, consecrating lieux de mémoire across the country, to honor men who had become national heroes in the state's historical narrative. These locations included the mausoleums of Ferdowsi, Hafez, Saʿdi, Nader Shah, and Omar Khayyam, among many others.Footnote 7 Through this work, in the words of Ali Mozaffari, the society became “a major driving force in the formation of the modern discourse of heritage in Iran.”Footnote 8

As Hobsbawm has argued, the historical narratives put forward by state ideologues do not represent “what has actually been preserved in popular memory, but what has been selected, written, pictured, popularised and institutionalised by those whose function it is to do so.”Footnote 9 The purpose of this “invention of tradition” is, as Mozaffari and Westbrook argue, to “confer legitimacy to authority structures, and to reinforce a sense of social cohesion and community membership.”Footnote 10 Museums are particularly important institutions through which to explore this aspect of the invention of traditions and the formulation of historical narratives because they often represent, in the words of Patricia Davison, “authorised versions of the past.”Footnote 11 In this sense, they have the power to shape public memory, by deciding what should be represented and what should not—what should be remembered, and what should be forgotten.

In the final two decades of Pahlavi rule, the state increased its use of museums to disseminate its ideology as it evolved, as well as official versions of Iranian history. An important preoccupation of the Pahlavi state throughout the 1970s was its striving for cultural authenticity and political legitimacy. However, as several scholars have pointed out, there were disagreements among the Pahlavi political elite and intellectuals linked to the Imperial Court as to how the state should project itself during this period, as the middle class became more disillusioned with the Pahlavi autocracy and society at large with its cultural politics. Ali Mirsepassi and Mehdi Faraji, for instance, have shown how the journal Bonyad Monthly, sponsored by Princess Ashraf, sought to depoliticize gharbzadegi “to construct a ‘culturally authentic’ narrative for the rule of the Pahlavi monarchy.”Footnote 12

This article builds on an important body of literature that has examined the formation and articulation of Pahlavi state ideology and official historical narratives, including through texts authored by the shah and scholars linked to the Pahlavi regime, celebrations and commemorations, cultural and educational organizations, and architecture.Footnote 13 There have also been several important studies of museums in the Pahlavi period, particularly studies that stress their function as representations of modernity and identity.Footnote 14 However, there have been comparatively few studies on the role of the museum as a space in which the Pahlavi state communicated its official version of history to a wide population. The Pahlavi Dynasty Museum is a compelling case study for several reasons. First, it was the only museum dedicated to the whole Pahlavi period; second, it was the only example of a Pahlavi palace converted into a museum; and third, the shah took a keen interest in the museum at all stages of its development, and significant funds were spent on producing a museum that matched his vision.

Since the literature on the Pahlavi Museum is so limited, this article draws on a wide range of Persian-language primary source material from the National Library and Archives of Iran, including letters, contracts, and official reports, as well as newspapers, magazines, and catalogs, to explore the extent to which different concepts of monarchical rule were evident in the planning and construction of the Pahlavi Museum. How did the museum reconcile the apparent tensions to which other scholars have referred, and attempt to bring together the various components of the Pahlavi national narrative to strengthen and legitimize the shah's rule in this fraught period? Conversely, given the central input of the shah in this initiative, and the fact that it was built for general consumption, could we argue that it was a more authentic representation of what might be termed “Pahlavi ideology”?

Museums and Pahlavi Cultural Policy

During the reign of Reza Shah (1925–41), the state dedicated considerable resources to strengthening its bases of legitimacy and shaping national identity through cultural activity. New buildings were constructed incorporating ancient styles, books were published to reflect the Pahlavi official historical narrative, laws were passed to safeguard Iran's cultural heritage, mausoleums constructed and celebrations held to commemorate heroes of Iran's past, most notably the Ferdowsi millennial celebration in 1935, and museums constructed, most significantly the National Museum in Tehran.Footnote 15 The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in August 1941, the subsequent abdication of Reza Shah and the accession of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, resulted in a period of relative social and political freedom. Political parties and newspapers were founded, and a clash ensued between the royal house, which sought to preserve the powers Reza Shah had gained, and liberal and religious groups who argued that the shah should be bound by the 1906 constitution, and therefore reign and not rule.Footnote 16 It was only after the resolution of this battle in favor of the shah in the years following the ousting of Mohammad Mosaddeq in 1953 that the Pahlavis were able again to continue to work toward the homogenization of Iranian culture and history that had begun under Reza Shah.

Whereas the 1950s might be characterized as a decade of political struggle, the 1960s were a decade of consolidation. The launching of the White Revolution in 1963, the granting of the title Āryāmehr to the shah in 1965, and the coronation of 1967 represented attempts by the shah to strengthen political authority around the throne. In 1964, during the premiership of Hasan ʿAli Mansur, eight new ministries were established, including a Ministry of Culture and Arts. Mehrdād Pahlbod, the shah's brother-in-law through his sister Princess Shams, was appointed the minister of culture and arts, a position he held until 1978.Footnote 17 From this period, it could be said that responsibility for the implementation of cultural policy was primarily divided between the Ministry of Culture and Arts and the Imperial Court. The Imperial Court's cultural section, under the supervision of Shojāʿeddin Shafā, was essentially in charge of academic conferences, libraries and books, or, as Richard Frye put it, “anything to do with universities, anything to do with learned societies, with professors or the like,” and the Ministry of Culture and Arts was in charge of music, film, art, and theater.Footnote 18 Later, in the late 1960s and into the 1970s, Empress Farah, along with her private secretariat, became an important driver of cultural activity, by renovating buildings, establishing museums, building art collections, organizing conferences on architecture, and arranging exhibitions and festivals.Footnote 19

The inauguration of museums became an important part of cultural policy during the late Pahlavi period in particular. On the eve of the Iranian revolution, as Talinn Grigor has observed, “the list of museums was impressive,” and included newly founded museums in Tehran such as the Shahyād Āryāmehr Museum (1971), the Museum of Contemporary Art (1977), the Reza Abbasi Museum (1977), the Carpet Museum (1978) and the Sixth Bahman Museum (1977) in Tehran, and various museums in other cities, for example the Ibn Sina Museum in Hamedan (1954), the Shush Museum (1966), and the National Museum of Kashan (1970).Footnote 20 Historical buildings, including palaces, also were repurposed as museums and opened to the public for the first time. These included the Isfahan Museum located in the hall of the Safavid Chehel Sotun Palace (1958) and the Qajar Golestān Palace in Tehran (1967).Footnote 21

As more and more museums were established during the late Pahlavi period, the organizational structure to manage museums underwent considerable transformation. Beginning in 1956, museums had been directed by the Department of Museums and Popular Culture (Edāreh-ye Muzeh-hā va Farhang-e ʿĀmmeh), which was a department within the Administration of Fine Arts (Edāreh-ye Koll-e Honar-hā-ye Zibā). The popular culture section was separated from that department after the establishment of the Ministry of Culture and Arts in 1964, and the historic buildings section of the Directorate of Archaeology joined it. As a result, the Department of Museums and Popular Culture became the Administration of Museums and Preservation of Historic Buildings (Edāreh-ye Koll-e Muzeh-hā va Hefz-e Banā-hā-ye Tārikhi), under the supervision of the cultural deputy.Footnote 22 In 1973, because of the vast increase in cultural activity, the Administration of Museums (Edāreh-ye Koll-e Muzeh-hā) was separated from the Preservation of Historical Buildings (Hefz-e Banā-hā-ye Tārikhi) to continue independently as a part of the Department of Research and Preservation of Cultural Heritage (Moʿāven-e Pazhuhesh va Hefz-e Mirās-e Farhangi). It also became a member of the International Council of Museums.Footnote 23 These administrative and bureaucratic changes reflected the state's recognition of museums as a distinct and increasingly important part of Pahlavi cultural policy.

Celebrating the Fiftieth Anniversary of Pahlavi Rule

During the late Pahlavi period, several large-scale commemorative events took place, intended to extol the role of the monarchy in the long history of Iran and place the Pahlavi regime within this glorious tradition. These events included the coronation of 1967 and the imperial celebrations of 1971. During these events, the Pahlavi period was presented as the culmination, and perhaps even the height, of Persian grandeur. The narrative was that after centuries of decay the lofty heights of Persian preeminence had again been reached by the Pahlavis, and the shah was a modern-day Cyrus the Great. Whereas these events in particular sought to connect the Pahlavis to past glories, other events in the 1970s focused specifically on celebrating the Pahlavis within a specific modern historical context. Among these events was the tenth anniversary of the Iranian revolution (sāl bozorgdāsht-e daheh-ye enqelāb-e Irān), held in 1973 to mark ten years since the launch of the shah's White Revolution reforms.Footnote 24 As part of this commemoration, a 5000-member national congress was held in the hall of the Ancient Iran Museum in Tehran from January 21 to 24 to evaluate the success of the revolution, and in between sessions sports demonstrations and tribal dances were performed.Footnote 25 Books also were published, informing readers about the success of the shah's revolution and the resurgence that had occurred under his rule.Footnote 26 Whereas this commemoration focused specifically on the impact of the White Revolution reforms on Iranian society, economy, and development from 1963 to 1973, the next national celebration, held just three years later, covered the whole period of Pahlavi rule (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Poster for the tenth anniversary of the Iranian revolution. Behind the shah are symbols depicting the twelve points of the White Revolution. “The Tenth Anniversary of the Iranian Revolution,” 1.

The fiftieth anniversary of Pahlavi rule was marked throughout the Persian year 1355 (1976–77), to coincide not with the anniversary of the act of parliament that established the dynasty but with that of the coronation of Reza Shah in April 1926. It was celebrated nationwide and, like the previously mentioned commemorations, featured a comprehensive program of events and publications. It was more similar to the imperial celebrations of 1971 than the 1967 coronation or the 1973 ten-year anniversary of the White Revolution, in the sense that it was a yearlong celebration, with commemorative activities held throughout. The logo for the occasion was also strikingly similar to that of the 1971 celebrations, featuring this time the crown rather than the Cyrus cylinder, encircled by twenty-five large disks and twenty-five small ones. The main event was held on the first day of the Persian new year, 1 Farvardin (21 March 1976) and included a ceremony at the tomb of Reza Shah in Tehran. Present at the event were high-level government and military officials, in addition to some twelve thousand Iranian citizens, representing the many different classes in Iranian society. The shah delivered a speech at the tomb, in which he said, with typical aggrandizement:

In the presence of the history of Iran, I make this announcement, that we, the Pahlavi dynasty, have no kindness, but for Iran, no love, but for the glory of Iranians, and we know no duty for ourselves but for our country and nation. We have risen from the nation of Iran, we were born from the blessed soil of Iran, and back to the soil we will [one day] return.Footnote 27

The closing ceremony was also held at the tomb of Reza Shah, on his birthday (24 Esfand 1355/March 15, 1977), during the last month of the Persian calendar, also in the presence of the government and senior officials.Footnote 28

On each day of the year 1355, Rastākhiz newspaper published a special section dedicated to the fifty years of Pahlavi rule, Ruzshomār-e Tārikh-e 50 Sāleh, in which it ran stories about significant events that had taken place on that particular day. Although many of the events highlighted stemmed from the formative years of Pahlavi rule under Reza Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi also was heavily featured. In an article on the coronation of Reza Shah, for example, the main subheading read: “The dignity and grace of the 6-year-old crown prince had attracted everyone's attention at the coronation.”Footnote 29 Many of the events held during this year corresponded to important events in the fifty-year history of the Pahlavis. For example, events were held on April 24 to commemorate the coronation of Reza Shah in 1926 and the end of capitulations in 1928, and other events commemorated the forty-third anniversary of the founding of the University of Tehran on September 23; the granting of social rights for women on January 7; and the founding of the Iranian Civil Defense Organization (Sāzmān-e Defāʿ-e Gheyr-e Nezāmi-ye Keshvar) on February 14.Footnote 30

This idea of observing a series of commemorations of events on the day of their anniversary was reflected in one of the most ambitious publications of the anniversary, the Gāhnāmeh-ye Panjāh Sāleh-ye Shāhanshāhi-ye Pahlavi. This chronological daily record of events in the fifty-year history of Pahlavi rule was the result of two years of study undertaken by a group of researchers at the Pahlavi Library, who consulted state and media archives and libraries in Iran and in Asia, Europe, and America.Footnote 31 The book begins on 3 Esfand 1299/February 22, 1921 and ends on 26 Esfand 1355/March 17, 1977. Although it is a chronological history of the whole Pahlavi period, considerably more attention is paid to the exploits of the latter monarch.Footnote 32 This demonstrates that despite the fact that Reza Shah “the Great” was the founder of the dynasty, the court ensured that the current king was a main focus of attention. An almost identical narrative also would be expressed through the layout and displays of the Pahlavi Museum.

The Gāhnāmeh was not published before the revolution, but there were many other works published to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary celebration.Footnote 33 The shah's court minister, Asadollāh ʿAlam, claimed that as many as ninety books were published in 1355 directly to support the anniversary.Footnote 34 These included texts on the successes of the Pahlavi period, such as one published by the Government Railway of Iran titled 50 Years of the Pahlavi Dynasty and 49 Years of the National Railway, and another titled Cultural Activities in the 50 Years of Pahlavi Rule: Shows, Music, Opera, Dance.Footnote 35 Others focused on science and technology, including subjects as diverse as statistical analyses of snowfall in Iran, opium, and multidirectional elevators. According to ʿAlam, one of the best-selling works was Reza Shah's Safarnāmeh-ye Māzandarān (Mazandaran Travel Diary).Footnote 36 The Imperial Organization for Social Services, under the supervision of Majid Rahnemā and the patronage of Princess Ashraf, set up the Pahlavi Commemorative Reprint Series “as a cultural homage to the memory of His Imperial Majesty Reza Shah the Great,” which comprised fifty volumes of books first published between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries that had long since been out of print.Footnote 37

Commemorative events in the late Pahlavi period also commonly featured the inauguration of cultural institutes. For example, Rudaki Hall was inaugurated during the coronation celebrations, and the Shahyād Tower was inaugurated during the imperial celebrations of 1971. Among the events held throughout the fiftieth anniversary celebration was the inauguration ceremony of the Pahlavi Museum, which in many respects embodied the philosophy behind the anniversary celebration, drawing attention to and glorifying the fifty years of Pahlavi rule and looking ahead to the future era of the Great Civilization. In this sense, the museum was fully consistent with state-sponsored initiatives to strengthen monarchical ideology and reinforce the idea of the shah as central to the past and future prosperity of Iran.

The Imperial Decree to Establish the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum

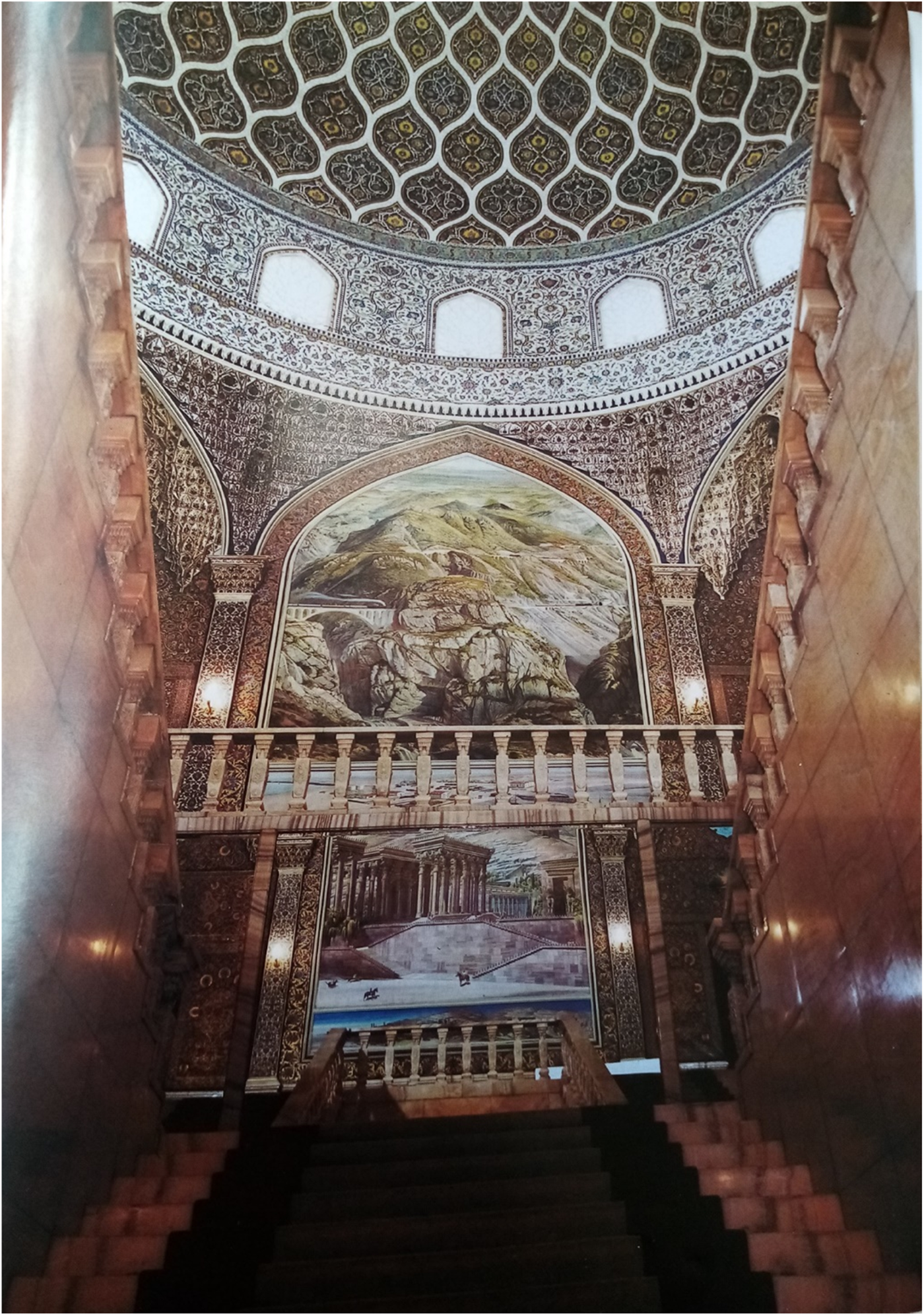

The Marble Palace had originally been built on the order of Reza Shah in 1937, on lands belonging to ʿAbdol-Hoseyn Farmān Farmā, one of the most prominent Qajar princes, whose son had previously built a mansion there.Footnote 38 It was called the Marble Palace because the exterior of the building was covered with marble.Footnote 39 The palace is a two-story building with a dome inspired by the Sheikh Lotfollāh Mosque in Isfahan. Its design combined this and other Iranian architectural features with European features, especially visible in its plan and arcs.Footnote 40 The first floor consists of four large halls called Tālār-e Āyneh (Mirror Hall), Tālār-e Nimeh-Āyneh (Half-Mirror Hall), Tālār-e Khātam (Inlay Hall), and Tālār-e Sofreh-Khāneh (Dining Hall), in which traditional arts were used, such as mirror work, inlaid work, and miniature painting. In addition, there were murals of railway lines and Persepolis on the north and south walls of the entrance hall, representing the modernization policies of the early Pahlavi government as well as its archaism (Figure 2).Footnote 41

Figure 2. The Marble Palace. The staircase to the first floor with the view of the dome and the paintings of Hoffman, the renowned German painter, including the Veresk railways on the south wall and the Apadana in Persepolis on the north wall, reflected in the mirror of the staircase. Javādi, Negāhi be ʿEmārat-e Tārikhi, 36.

The palace served as the shah's residence, primary workplace, and site of official receptions, as well as the main gathering place for government leaders, parliamentarians, ministers, and ambassadors of the Pahlavi regime for some three decades until 1965, when Mohammad Reza Shah moved to Niyāvarān Palace in the north of Tehran.Footnote 42 Five years after his departure, the shah donated “the entire (shesh dāng) private mansion known as the Marble Palace with all its lands, attachments and current belongings to the city of Tehran to be used as a museum of the Pahlavi dynasty.”Footnote 43 The Pahlavi Museum is reportedly the only museum in Iran that was founded in an endowed royal palace.

There were two benefits to establishing the museum through an endowment (waqf). First, employing traditional Islamic endowment law gave the Pahlavi Museum a degree of legitimacy and increased the chances of generating popular support. And second, giving the palace to the people provided an opportunity to strengthen the connections between the Pahlavi royal house and the nation. Indeed, one of the important narratives expressed through the museum's design and display was that of the deep connection between the dynasty and the people.Footnote 44 The representation of this relationship in the museum was also highlighted by members of the political elite, such as Sādeq Kiā, the artistic deputy of the Ministry of Culture and Arts, who stated that “the relationship between the shah and the nation should be taken into account everywhere [in the museum] and the Shāhanshāh should not be separated from the nation.”Footnote 45

Under religious law, endowment status is normally given to institutes that provide a benefit to the public, such as schools, mosques, hospitals, and charities. Therefore, creating an endowment in a cultural institute, such as a museum, particularly one that clearly served as state propaganda, was problematic. In a letter to the minister of court, Asadollāh ʿAlam, written immediately after the announcement of the farmān, a senior legal advisor, Habibollāh Āmuzegār, described the endowment of the Marble Palace as a “divine and benevolent” (khodāpasandāneh va bashardustāneh) act.Footnote 46 However, he also expressed concerns that because the museum did not have a charitable income, it was not a waqf and should instead be considered a gift (hebe). He wrote that:

According to Article 55 of the Civil Code, endowment (waqf) consists of entail (habs-e māl) and the spending of income on certain affairs. While the Marble Palace does not have any income to be used for charity . . . in accordance with Article 795 of the Civil Code, this great and benevolent act . . . is a gift (hebe).Footnote 47

Accentuating this point, he added: “In the official speech of Your Excellency (ʿAlam) and the mayor of Tehran, there are several references to endowment (waqf, mowqufeh) which is contrary to the legal form of the act.” He also suggested that this issue could discussed with “enlightened clerics and legal scholars” to come up with a solution.Footnote 48

The deputy minister of court, Mohammad Bāheri, proposed a solution to this problem, by stressing that value is not only monetary, but educational and cultural:

Benefit is not always about money or income; the mosque which is a place of worship, the Hosseiniyeh which is a place of mourning, the school which is a place of education and learning, the library which is a place to store and study books, are endowments and there is no problem regarding their endowment. The Marble Palace is the location of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum, and its special advantage is that certain [important] objects are displayed there.Footnote 49

In the end, it appears that the concerns of Āmuzegār were dismissed and the endowment went ahead. Some months later the Endowments Organization (Sāzmān-e Owqāf) asked the Imperial Court to provide them with the texts of the endowment deeds of places bequeathed by the shah, such as the Marble Palace.Footnote 50 These documents were supposed to be exhibited in Persian, English, Urdu, and Arabic in a pavilion dedicated to the shah's “divine acts” (eqdāmāt-e kheyrkhāhāneh va khodāpasandāneh), in a series of Quran exhibitions that were being organized in Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Jeddah.Footnote 51

In the text of the farmān, the shah declared that he chose the Marble Palace as the location for his dynastic museum because it was “a supreme example of the artistic taste of this great nation and an outstanding work; the result of our dynasty's art, the development and patronage of artists as well as one of the unique works of art of the first quarter of the current century.” In this museum, he adds, “works of art as well as evidence of the changes and developments of the country resulting from the patriotism of our noble father and ourselves” would be displayed.Footnote 52 The purpose of this museum, he stated, was to increase knowledge and awareness of the history of modern Iran. It also aimed to make the imperial history of Iran more accessible to domestic and foreign researchers by establishing a study center there, in which documents pertaining to the Pahlavi era would be made available for research.Footnote 53 The shah, therefore, intended that the Marble Palace should not merely serve as a museum to exhibit the glories of the Pahlavis, but also as a documentation center, in which the purported achievements of the Pahlavi era could be authenticated.

The shah handed over the trusteeship of the endowed property and the management of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum to the mayor of Tehran, and entrusted the supervision of the endowment, the management of the museum, and the protection of the property to a board of trustees (motawalli), comprising the prime minister, president of the Senate, head of the Majles, and the minister of the Imperial Court.Footnote 54 The fact that the museum was donated by the shah personally and that such eminent figures were charged with overseeing its operation demonstrates the significance the shah attached to this museum. Another sign of the museum's importance in the eyes of the shah was that, according to the organizational chart of the Ministry of Culture and Arts, the Pahlavi Museum was under the direct supervision of the Department of Research and Preservation of Cultural Heritage (Moʿāven-e Pazhuhesh va Hefz-e Mirās-e Farhangi), rather than the Administration of Museums.Footnote 55 The only other museums that had this status were the Museum of Ancient Iran and the Shahyād Āryāmehr Complex.

The First Design of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum, by the Albini-Helg Studio (1972–74)

In 1972, a contract was signed between the Municipality of Tehran and the Architecture Studio of Franco Albini and Franca Helg from Italy (Studio di Architettura Albini-Helg) for the design, execution, and supervision of the conversion of the Marble Palace into the Pahlavi Museum. The vast majority of the work of converting the palace into a museum was carried out by Italian firms; in addition to Albini-Helg, contracts were also signed with Plotini Allestimenti (Paolo Plotini) for the supply of furniture and Emilio Fioravanti for the design of the museum's logo and some models.Footnote 56 Although these firms were engaged in the design of the museum, the exhibits and narrative were entrusted to the municipality. Official letters were sent by the trustee, mayor of Tehran Gholāmrezā Nikpey, to various ministries, public offices, and organizations, asking them to prepare and send photos, slides, models, and so forth, documenting the most significant achievements of the Pahlavis over the last fifty years.Footnote 57

According to the trustee, efforts were made when designing the museum “not to damage the palace building, which has a special architectural style, while at the same time the novelties of the current era are to be taken into account in the representation of the documents and photographs.” The project, he claimed, “was the result of a joint work between the museum's trustee historically, and the Albini-Helg Studio artistically”:Footnote 58

The mayor personally took the responsibility of preparing the history of the Marble Palace and selecting the greatest incidents and most important events in the last fifty-year history of Iran, which would be compatible with the building features and the division of the halls. . . . The [Albini-Helg] Studio decorated the halls and represented the documents so that each hall reflected its relevant situation.Footnote 59

The transformation from palace to museum took around two years, with the Italian team completing their work in the winter of 1974.

According to the Albini-Helg plan, visitors would begin their visit in the first hall on the west side of the entrance hall and would finish in the Mirror Hall, upstairs. In the first exhibition hall, the sociopolitical and economic situation in Iran in 1921 was represented to depict the condition of the country at the time of the coup, and then to show the developments that had been made over the following twenty years under Reza Shah. Then the next hall displayed the situation of Iran at the time of the Allied invasion in 1941 until 1963, the eve of the White Revolution. The implementation and impact of the White Revolution was the theme of the third hall, along with historical changes in the country until 1972. Displaying developments in Iran of the last fifty years, the proceeding halls compared the topics of education, health and social welfare, communications, agriculture and rural affairs, sports and youth, the Imperial Army, tourism, workers and social affairs, culture and arts, industries and mines, urban planning, water and electricity, and finally the oil, petrochemical, and gas industries at the time of the three different milestones: 1921, 1941, and 1972. There was another hall on the first floor dedicated to the representation of important documents of the Pahlavi period. The rest of the palace, including the Hall of Mirrors, the Inlay Hall, and the bedroom of Reza Shah, remained in its original form with few changes, displaying Reza Shah's clothes and other possessions (Figure 3).Footnote 60

Figure 3. Plans of the ground (left) and first (right) floors of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum designed by the Albini-Helg Studio. On the plans, the names of the halls and the route designed for visitors to the museum are set out. Nikpey, Panjāh Sāl dar Kākh-e Marmar, 11.

In this design, the history of the Pahlavi dynasty was divided into three distinct periods: 1921 to 1941, 1941 to 1963, and 1963 to 1972; the beginning of Reza Shah's rule, the beginning of Mohammad Reza Shah's rule, and the White Revolution were considered turning points. The goal of the design was to emphasize progress during the Pahlavi period. To this end, in the first room of the museum, where visitors began their journey, the state of the country was depicted as exaggeratedly dark before the arrival of Reza Pahlavi. The visitors then entered several rooms representing the developments and achievements during the Pahlavi era. In the final space, the Hall of Mirrors, the brightness of the lights started at the lowest level, “increasing gradually while simultaneously broadcasting a sentence of Mohammad Reza Shah's speech through a speaker, promising a bright future.”Footnote 61 This also implied that the rate of development had accelerated during Mohammad Reza Shah's rule, in comparison to his father's. The logo designed for the museum clearly emphasized this difference, as it depicted, in the words of Nikpey, “rapid progress which started from a small point and developed exponentially” (Figure 4).Footnote 62

Figure 4. The logo of the Pahlavi Museum symbolizes the rapid progress during the late Pahlavi period by starting from a small shape and enlarging exponentially.

This concept was repeated in other mediums as well. For example, in a book published in 1974 about the Pahlavi Museum and its history, written by Nikpey and entitled Fifty Years in the Marble Palace, just nineteen pages were dedicated to the Reza Shah era, whereas fifty-one covered the period of Mohammad Reza Shah's rule. This skewed historiography also was applied to the dynasty that preceded the Pahlavis. The highlighted events of the Pahlavi dynasty were, by and large, related to progress, growth, and development, whereas what little was displayed of the Qajar period primarily referred to regression, backwardness, and decay.Footnote 63

The Second Design of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum

In March 1974, the shah visited the Pahlavi Museum to review the progress made by the Albini-Helg Studio. Despite all the expenses and the roughly two years of planning, the shah was decidedly underwhelmed and ordered that a new design be put together.Footnote 64 His dissatisfaction with the design was expressed in a letter by the prime minister, Amir ʿAbbās Hoveydā, to the director of the shah's special bureau, Nosratollāh Moʿiniyān, in which he wrote:

The manner of the representation of the Museum, both in terms of content and its form, as well as its relationship to the monument of the Marble Palace itself, do not meet the high intentions of His Majesty . . . and the historical facts, as represented in the museum, are such that they do not adequately reflect the highlights and important points of the history of the Pahlavi dynasty. In addition, the design does not demonstrate the necessary synthesis of styles; the modern aspects are presented in a different way to the traditional and old aspects. . . . Nonetheless, the valuable images and documents that are interestingly displayed can be used in a new design.Footnote 65

Given his dissatisfaction with the Albini-Helg design, the shah decided to approach another designer who he trusted and had employed on previous projects, the Czech artist Jaroslav Frič.Footnote 66

Frič had a portfolio of international clients through his Science-Art-Sense working group, in Australia, Egypt, Japan, Canada and the United States, to whom he offered exhibition designs that incorporated modern audiovisual technology.Footnote 67 These projects utilized, in the words of Daniela Kramerová, “multi-projection systems combined with music and presentations of arts and crafts” to highlight “the beauty, history, and future outlook of the given country.”Footnote 68 The shah became aware of Frič during the 1967 World Exposition in Montreal, where he and Empress Farah had been impressed by the Czechoslovakian exhibition, which Frič had designed. In November 1968, when the president of Czechoslovakia, Ludvík Svoboda, visited Iran, the shah discussed his eagerness to employ Frič on projects in Iran. Shortly thereafter, Frič was hired to design the museum in the Shahyād Tower, which would open during the 1971 imperial celebrations.Footnote 69 He would later also be commissioned to design the Sixth Bahman Museum, which was built underneath the tower.

In a letter to the head of the Plan and Budget Organization, ʿAbdol-Majid Majidi, Frič outlined his criticisms of the previous design and the initial ideas for his future design.

The vitrines and their arrangement are in a most profound contrast to the interior of the Palace. The architecture of the Palace, its atmosphere and traditional aspects are completely negated by the exhibition. . . . So many facts are mixed into the exhibition that the whole loses its internal link and meaning. . . . In short, it is a dead exhibition which not only does not fulfil the intended function, but also destroys the very interior of the Palace.Footnote 70

Frič proposed to “dismount the installation of the exhibition” and start a new project, which could be completed in two years.Footnote 71

The shah gave the commission to Frič on the proviso that it must be ready for opening by the end of Esfand 1354 (March 1976), in time for the beginning of the fiftieth anniversary celebrations.Footnote 72 At this time, the governing body of the museum changed slightly. Ownership of the palace and contents of the museum were entrusted to the Ministry of Culture and Arts, as was the management of executive operations; this job was taken away from the mayor of Tehran, although the municipality remained the trustee of the museum. Handing the administration of the museum to the ministry was intended to add urgency and ensure that the museum was completed in a timely manner, with more resources and closer oversight, so that it would adhere to the standards expected by the shah.Footnote 73

Indeed, hereafter the shah had a greater degree of input to the project and was kept up to date with developments. For example, after the suggestion for another structure to be constructed inside the palace, the shah ordered that “any plan prepared for this museum should be implemented exclusively in the current building, and the construction of another building for the museum in this palace is not at all necessary.”Footnote 74 Later, after Frič had completed the layout, models, and plans for the museum, Pahlbod wrote to the shah that the materials were ready to be presented to him, and that Frič would stay in Tehran to give an in-person explanation.Footnote 75 On another occasion, in January 1975, Pahlbod sent a letter to ʿAlam outlining the opinions of advisors Sādeq Kiā and Yahyā Zokā on the Frič plan, and requested that these comments be presented to the shah. ʿAlam approved this request, writing in pen on the side of the letter, “because the issue of founding the museum is important, it is better that . . . the shah be informed about the comments.”Footnote 76

According to the Frič design, eighteen halls made up the Pahlavi Museum. Visitors entered the museum through the entrance hall (Hall 1), and then the first five rooms set out the official Pahlavi narrative chronologically as follows:

1. The period before Reza Pahlavi's coup of February 1921 (Hall 2);

2. The Kingdom (Shāhanshāhi) of Reza Shah, 1299–1320/1921–1941 (Hall 3);

3. Iran during and after the Second World War, 1320–1341/1941–1962 (Hall 4);

4. The White Revolution, 1341–1354/1962–1975 (Hall 5);

5. Toward the Great Civilization, 1354/1975 onward (Hall 6).

Unlike the Albini-Helg design, which divided the museum into three periods, the Frič design was divided into five, to present clearly the four key pillars of the historical narrative that legitimized the Pahlavi dynasty. These were: first, the decline and backwardness of the Qajar period, which ended suddenly with the emergence of Reza Pahlavi and the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty; second, Iran's 2500-year-old tradition of monarchy that the Pahlavis represented; third, the White Revolution, which had become the crowning achievement of the Pahlavi period and a symbol of the rapid modernization that had occurred under the rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi; and finally, the Great Civilization, which promised a future for Iran under the Pahlavis as glorious as its past. These themes were found throughout the whole museum, in the account of the Pahlavis narrated in the first five halls and in subsequent rooms.

These four pillars, which formed the basis of the design of the museum, were displayed through different mediums including “graphic collages pasted to metal panels,” videos and slides, sculptures, and oil paintings, most of which were produced in workshops in Czechoslovakia and installed in the museum later.Footnote 77 The materials used to create the collages were carefully selected, and they changed according to the story narrated in the halls. In early halls, for example, zinc was extensively used, but in later halls, more expensive materials were used, such as bronze, steel, silver-plated, and finally gold-plated metal in Hall 6, representing the Great Civilization.Footnote 78

Qajar Decline and Pahlavi Ascent

In the Frič design, as in the Albini-Helg design, the Qajar dynasty was presented as the cause of the backwardness of Iran and the destruction of its glorious history and tradition. In Hall 2, which exhibited the background to Reza Shah's emergence, the helplessness, poverty, illiteracy, terror, and despair of the nation were depicted by the various images on display. These included images of shanty houses in Tehran, of impoverished city-dwellers making bread from muddy water and flour, and of an oppressed population being punished with the whip.Footnote 79 No mention was made of any of the defining moments of the period, most significantly the Constitutional Revolution. By relegating the Constitutional Revolution to a footnote, the contributions of some of its later champions, such as Mohammad Mosaddeq, could justifiably be removed from the narrative completely (Figure 5).Footnote 80

Figure 5. Collage showing the misery of Iran at the time of the 1921 coup. Muzeh-ye Selseleh-ye Pahlavi [brochure].

In contrast to the darkness of the Qajar period, the arrival of Reza Shah as “the man on horseback” was presented as destined to ignite a resurgence in Iran. This savior narrative can be dated essentially to the time of the coup in February 1921 and was immediately promoted by Reza Khan and his followers.Footnote 81 The exhibits in Hall 3 charted the modernization of Iran under Reza Shah, including images of the construction of the first railways, the development of industry, the shah's visits to cultural heritage sites, notably Persepolis, and his speeches and many visits to places such as schools, hospitals, and military institutions, as well as his visit to Turkey. A collage of historical photographs of Reza Shah's coronation accompanied by illustrations that normally evoke happiness and peace, such as flowers, children, birds, and the sun were provided to convey to visitors the atmosphere of harmony and comfort that had permeated the country since the beginning of Pahlavi rule, following the despair of the Qajar era. In this way, Reza Shah was presented as the man who gave Iran political unity and laid the foundation for its social, economic, and cultural reconstruction.Footnote 82

As in the previous design, the rooms that had been occupied by Reza Shah—the Dining Hall (Hall 11), the Audience Hall (Hall 12), and Reza Shah's study (Tālār-e Khātam, Hall 14)—remained largely intact. In the Audience Hall, where affairs of state would have been discussed, a recorded commentary narrated the visits of ministers, generals, and diplomats, who would have come to receive instructions from their sovereign.Footnote 83 The dominant element in this hall was a sculpture depicting the Pahlavi family tree, which was an abstract combination symbolizing the Pahlavi dynasty and its connection with the nation.Footnote 84 In the garden, an audio program of “whispering trees” was set up, in which, while walking among the trees, one could hear short stories about events in the lives of the two Pahlavi shahs, played through speakers which were hidden between trees. This installation was designed as a modern technological interpretation of the original style of Iranian storytelling (naqāli), and reflected the tradition-modernity discourse.Footnote 85

Iran's Ancient Monarchical Tradition

One of central features of the romantic nationalist discourse that the Pahlavis adopted was the idea that Iran had a 2500-year-old monarchical tradition, and that throughout its history it had prospered due to the strength of this institution and the preeminence of its kings. During the late Pahlavi period, in particular, the state introduced wide-ranging policies to inculcate this idea in the population, by encouraging archaeological investigations focusing on Iran's ancient history, sponsoring scholarly congresses on the history of ancient Iran, and publishing books. The most brazen example was the imperial celebrations of 1971, and the subsequent decision in 1976 to introduce an imperial calendar, counting from the accession of Cyrus the Great in 559 BC.Footnote 86 Efforts to link the Pahlavis to the Achaemenid dynasty were evident throughout the museum. For example, as soon as one entered the entrance hall, one was confronted with busts of the two Pahlavis atop marble columns.Footnote 87 On one side, there was a glass box in which a map of Iran was placed, executed in gold-plated brass, with decorative stones marking the capitals of the provinces. In addition, a metal screen in the center of the hall displayed several tablets describing significant events in Iranian history, including a proclamation of Darius the Great addressing future kings of Iran, the law decreeing the foundation of the Pahlavi dynasty, and the deed of the endowment of the palace.Footnote 88

The idea of the shah as a representative of an ancient kingdom was expressed through the sound and visual art exhibits of the museum. In a special cinema hall (Hall 9), three movies were chosen for screening throughout the day about various aspects of imperial rule. One was titled A Country with 2500 Years of Empire (Keshvari bā 2500 Sāl Shāhanshāhi) and depicted scenes of Persepolis, the beautiful and varied scenery of Iran and Iranian art, and historical events of the Pahlavi era, such as the coronations of two Pahlavi shahs, the White Revolution, and the imperial celebrations. The movie began with Cyrus the Great, as the founder of the Persian Empire, who had established Achaemenid rule over twenty-eight nations and whose successors had built and made Persepolis the center of Persian political culture and civilization. The Pahlavis were represented as the inheritors and ultimate successors of the Achaemenid kings, who worked tirelessly to rebuild the privileged position that the Achaemenids had enjoyed in the ancient world. As Iran commanded respect around the world, thanks to the Pahlavis, Iranians too, as long as the Pahlavis ruled and continued on the path toward the Great Civilization, would continue to live in “homes full of happiness and harmony.”Footnote 89 The museum garden also was set out to reflect the vastness and richness of a kingdom united under the throne, with separate sections for each province, each designed and maintained by the province to ensure that “each garden (bāghcheh) could grow according to its own traditions.”Footnote 90

The White Revolution

The White Revolution was widely presented in the museum exhibits as the defining moment in modern Iranian history, achieved due to the genius and magnanimity of the shah. This idea was exhibited most prominently in Hall 5 of the museum through a series of images, intended to demonstrate that “not even Cyrus the Great or Shah Abbas succeeded in giving the nation such a sense of faith and seriousness in building Iran and its future during their reigns.”Footnote 91 A collage reflected the declaration and leadership of the White Revolution by Mohammad Reza Shah, as well as scenes of the shah's activities, such as giving land ownership documents to farmers, opening industrial factories and dams, and speaking to large crowds, to depict him as the inspiration and leader of the revolution.Footnote 92 There also were images of women's parades, women in elections, and women gathering in the Marble Palace, as well as a nomadic girls’ school and female students on a field trip, to show the increasing gender equality that had been achieved as a result of the efforts of the shah.Footnote 93 Several images of the Literacy Corps (Sepāh-e Dānesh), Hygiene Corps (Sepāh-e Behdāsht), and the Reconstruction and Development Corps (Sepāh-e-Tarvij-va-Ābādāni) represented, according to the museum's brochure, the shah's motto: “Health for all, food for all, clothing for all, housing for all and education for all.”Footnote 94

A geometric sculpture was created, called “the Bench of Laws,” displayed prominently in the Hall of Laws (Hall 17). This sculpture had a circular base with a central cube that had three gold spheres attached, and was surrounded by several panels inscribed with the principles of the White Revolution.Footnote 95 In an article in Kāveh magazine, it was described as “a witness of the greatest gifts during the monarchy of the Pahlavi dynasty.”Footnote 96 Although the White Revolution existed as a set of laws, which all Iranians were expected to learn by heart, it did not exist as a tangible object. The “Bench of Laws” sculpture was an attempt to create a piece of art that Iranians could visit to show their appreciation for the shah's revolution (Figure 6). Moreover, in the museum's official brochure, it was said that the Marble Palace itself was a particularly important landmark in the context of the White Revolution, since it was here where “the idea of a bloodless revolution was conceived.”Footnote 97

Figure 6. Frič explaining the “Bench of Laws” to the shah on the day of the inauguration of the museum in 1355/1976. Bāzdid-e Mohammad Reza, NLAI 437584.

The Great Civilization

The shah first began to speak of the idea of a Great Civilization in 1971. The concepts behind it were not new, and attempts had been made throughout the 1960s to systemize a Pahlavi ideology.Footnote 98 The Great Civilization, for the shah, meant the dawn of a golden age for Iran, which would surpass even the age of the Achaemenids.

It means a civilization in which the best elements of human knowledge and vision shall have been employed in the interest of ensuring the highest standard of material and moral living for every individual; in which the novel acquisitions of science, industry and technology shall have been combined with high moral values and with the developed standards of social justice. It means a civilization which shall have been built on the foundation of creativity and humanity, and in which every human being shall, in addition to enjoying complete material welfare, benefit from the highest degrees of social security, and possess eminent spiritual and moral virtues.Footnote 99

These ideas were displayed in Hall 6 of the museum, through a collage of images and a map showing the industrialization of Iran, the sophisticated transport network, national wealth, the growth of cities, health services, universities, and schools, to demonstrate that Iran was, indeed, well on its way toward this great utopia envisioned by the shah.Footnote 100 Other illustrations, charts, and graphs reflected the state of an Iranian family in 1975, including average family income, figures related to social welfare, and so forth, to show that Iranians had benefited greatly from the state's efforts.Footnote 101

The final hall of the exhibition (Hall 18) was dedicated again to the Great Civilization. The room was designed in a special futurist style, to give the impression that one had taken a step forward in time. The ceiling and the walls were covered by huge reliefs in artificial stone, combined with light and mirrors, which multiplied the reliefs through reflections.Footnote 102 There also was a Great Civilization audiovisual program which was to change every two years to indicate the latest achievements of Iran on the path to the Great Civilization.Footnote 103 The exhibition had begun in Hall 2 with depictions of the squalor of life under the Qajars, and ended with the Great Civilization Hall (Hall 18), which included state-of-the-art techniques in its design. The purpose was to impress upon visitors how the fifty years of the Pahlavi rule had propelled the position of Iran from a backward country to one of the most advanced countries in the world, which had only just embarked on the path to a new golden age.

The Inauguration of the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum

The museum was inaugurated on October 30, 1976, in the presence of the shah and Empress Farah.Footnote 104 A poem was specially composed for the occasion by Mahmud Monshi and was recited to the imperial guests upon their arrival.Footnote 105 The poem begins with the couplet, “The Marble Palace narrates the tale of this country / Tells the stories of what it has in its chest.”Footnote 106 Although two out of the thirteen couplets were dedicated to Reza Shah, more than half focused on the life and successes of Mohammad Reza Shah, referring to his survival of the assassination attempt in the Marble Palace on April 10, 1965, the White Revolution, and the founding of the Party of Resurrection of the Iranian Nation (Hezb-e Rastākhiz-e Mellat-e Iran).Footnote 107

Despite the brief reference to the Rastākhiz Party in this poem, the exhibitions themselves contained very few references to the founding of the political party. Even in the shah's statements to the press after his visit, in which he spoke about both the Pahlavi Museum and the Rastākhiz Party congress, which had been held just two days before—interpreted by Grigor as underscoring “the importance of that institution and its links to his new Rastakhiz Party”—no connection was made between the two events.Footnote 108 The absence of the Rastakhiz Party in the exhibitions may have been partly a practical decision. Frič began working on the museum in 1974 with a strict deadline, and delivered the study plans, design reports, artistic plans, and models to the client around six months before the party was founded.Footnote 109 Still, the decision to ignore the Rastākhiz is surprising and suggests that the shah was striving for a more traditional version of Pahlavi nationalism here: closer to the Pahlavism of the late 1960s and early 1970s, rather than the anti-Westernism that was pursued by some ideologues linked to the Rastākhiz Party and its publications.Footnote 110 The figures involved in meetings about the museum were among the more conservative group of Pahlavi statesmen, including Prime Minister Hoveydā, Mehrdād Pahlbod, Shojāʿeddin Shafā, ʿAbdol-Majid Majidi, Gholāmrezā Nikpey, the minister of intelligence Hamid Rahnamā, and the head of the Iran Radio and Television Organization Rezā Qotbi, who were little interested in challenging the regime's long-held cultural policies.Footnote 111

The shah and Shahbanu began their tour of the museum with a film about Iran made by a Czech filmmaker, then walked around the five principal halls that narrated the history of the Pahlavi era. Following this, they visited the museum's library, which contained more than one thousand books pertaining to the history and culture of modern Iran, as well as newspapers, family albums, stamps, and magazines from the Pahlavi era. The library also had a device that contained 160 questions about the Pahlavi family, which a visitor would be able to try to answer by pressing a button.Footnote 112 The shah was clearly pleased with Frič's efforts. In an interview with the press, he declared: “This famous scholar [Frič] has studied the history of Iran well and has made the plan of this museum as an Iranian would have done. Visitors will see for themselves and will surely wonder how Professor Frič has managed to show the history of the time before us and that of our reign.”Footnote 113 After visiting Reza Shah's study and observing the many artifacts and photographs on display, the shah ordered that any objects he himself had used in this palace should be collected and returned there, presumably so that they might be displayed alongside those of his father.Footnote 114

According to official figures, the museum received a steady flow of visitors. During the first four months after opening, it received 23,840 visitors, 3,338 foreigners and the rest Iranian.Footnote 115 In the two last months of that same year, the museum attracted more visitors than the Ancient Iran Museum and the Golestān Palace Museum.Footnote 116 As a mark of its importance, shortly after opening, an image of the Pahlavi Museum was printed on the 100-rial banknote; it was the only museum of the Pahlavi era to have this honor (Figure 7). Several months before the revolution, in May 1978, the Pahlavi Museum building was registered as a national historic monument.Footnote 117

Figure 7. The Pahlavi Museum on a 100-rial banknote. Farahbakhsh, Rāhnamā-ye Eskenās-hā-ye Iran, 117.

Conclusion

The act of donating the shah's private palace for conversion to a public building was referred to as “the shah's great gift to the nation,” and it was said that “the shah's house became the people's house.”Footnote 118 This type of language was by this point common rhetoric. In 1971, for example, in a volume sponsored by the Iranian government, Ramesh Sanghvi wrote of the shah: “With missionary zeal he worked round the clock to fortify the bond of spirit and heart between himself and his people.”Footnote 119 The shah was particularly keen that the magnanimity of the act should be widely recognized. Indeed, in 1970, the shah complained to ʿAlam that his order to endow the property had not received sufficient attention in the press.Footnote 120 But however much the shah wished to be remembered for his generosity, the palace was still a state building and its content was carefully curated by figures connected to the regime. The museum that occupied the space of the former Marble Palace of the Pahlavis fit within a long tradition in the Pahlavi period of creating lieux de memoire, but it also was a very specific type of museum that empowered the Pahlavis, not merely by bolstering the ideological underpinnings of the regime but by glorifying and attempting to authenticate the achievements of the Pahlavis themselves.

This article has shown that the Pahlavi Museum sought to represent a highly selective history of modern Iran that reflected aspects the Pahlavis wanted to be remembered, and what they wanted to be forgotten. The idea of contrasting the chaos under the Qajars with the stability and development under the Pahlavis was, according to the shah “a very necessary comparison, to edify the people.”Footnote 121 And indeed, this was one of the main purposes of the museum; to educate the population, to guide them to appreciate the official version of Iranian history, and the value of having not just a shah, but a Pahlavi shah. This also was a stark warning of the state to which Iran might return should it ever find itself without a Pahlavi shah guiding the country. The Pahlavis had brought Iran political stability, security, economic development, industrialization, and respect on the global stage, and only with the guidance from the throne could Iran enter the promised era of the Great Civilization.

In contrast to other museums, the shah took a keen interest in the progress of the Pahlavi Museum, particularly in the later stages of its development. In 1972, for example, the mayor of Tehran received architectural plans for the project and asked whether they should be sent to the shah or Shahbanu for approval. The shah responded, “to me, of course.”Footnote 122 Later, when the shah was disappointed with the work of the Albini-Helg Studio, he ordered that a new designer be chosen. Jaroslav Frič was able to incorporate modern technologies into the museum's design, creating a more dramatic setting, converting the attractive but formal environment of a former palace into something interactive and high-tech. This change was made possible by the vast funding available to Frič. The oil price hike of 1973, which saw Iran's oil revenues quadruple from $5 billion in 1973–74 to $20 billion in 1975–76, meant that additional funds were available to all areas of government.Footnote 123 Although the first design had included contracts with the Albini-Helg Studio worth $39,000 (2.9 million rials), Plotini worth $500,000 (38.3 million rials) and Emilio Fioravanti worth $6,700 (500,000 rials), the contract with Frič was worth $2.85 million.Footnote 124 The Frič design therefore was able to more successfully encapsulate artistically the shah's utopic vision for Iran in the decades to come. Because of the shah's personal involvement as well as the huge sums of money spent on the museum, this was a major and unique development in the dissemination of official historical narratives and state ideology in the late Pahlavi period.

The intention was for the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum to be inaugurated in the early 1970s, and it was only by accident that it was ultimately opened as part of the fiftieth anniversary celebrations in 1976. However, it was most fitting that its opening coincided with this anniversary, as the same narratives that the anniversary celebrations sought to highlight were expressed in its exhibits. Although this museum was novel in many respects, it also reflected certain trends in museum-building in the late 1970s that sought to draw attention to the achievements of the Pahlavis. These museums included not only those in Iran, such as the Sixth Bahman Museum, which was inaugurated around three months after the Pahlavi Dynasty Museum, but also museums built abroad. For example, plans accelerated in 1978 to convert the house in which Reza Shah briefly lived during his Mauritian exile into a museum.Footnote 125 The creation of these types of sites of remembrance was not unique to the Pahlavis. In modern Tehran, the former Pahlavi palaces of Niyāvarān and Saʿdābād are open to the public, in an attempt to demonstrate the opulence and crassness of the Pahlavis. In contrast, the home of Khomeini at Jamārān Hosseinieh, which is also open to visitors, purports to show the modesty and piety of the founder of the Islamic Republic.

The Marble Palace itself, which closed to the public after the revolution, has undergone many transformations in the years since. During extensive renovations in the early 1990s, modifications were made according to the “cultural guidelines of the Islamic Revolution,” including the addition of religious motifs in the complex. The building was then given to the Expediency Discernment Council of the System (Majmaʿ-e Tashkhis-e Maslehat-e Nezām), which was chaired by the former president, Hāshemi Rafsanjāni, and its name was changed to the Qods Building. In 2018, the building was handed over to the Oppressed Foundation of the Islamic Revolution (Bonyād-e Mostazʿafān-e Enqelāb-e Eslāmi) to be turned into a museum called the Iran Art Museum (Muzeh-ye Honar-e Iran). In 2020, after a period of some forty-one years, the Marble Palace opened its doors to the public once more.