Renovatio urbis

Urban renewal is an ancient concept. Writing in the late AD 70s and 80s, the Roman poet Martial proclaimed that the building programmes of the emperors Vespasian (AD 69–79) and Titus (AD 79–81) had ‘returned (reddita) Rome to herself’, and that the rebuilding efforts of the emperor Domitian (AD 81–96) ‘renewed’ (renovant) the city with its temples ‘reborn’ (renata), having risen again like a Phoenix.Footnote 1 It was around this time that other authors first used the verb resurgere, ‘to rise again’, in reference to the urban fabric of the capital,Footnote 2 and on Vespasianic coins of the AD 70s the legend ROMA RESVRGES accompanies a depiction of the emperor raising Roma personified to her feet (Figure 1).Footnote 3

Figure 1. Vespasianic sestertius, AD 71. RIC II1 Second edition, Vespasian 195. Courtesy of The American Numismatic Society 1944.100.41561 (http://numismatics.org/collection/1944.100.41561), CC BY-NC 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0).

The prevalence of this type of language and imagery during these years is not coincidental. Rome was undergoing a dramatic reconstruction: large parts of the city (perhaps over two-thirds) had been devastated by major fires in AD 64, 69 and 80. This came at a time of what scholars have labelled an ‘architectural revolution’ marked by innovative developments in building design.Footnote 4 Consequently, the rebuilding efforts necessitated by the fires helped transform the appearance of the cityscape. So dramatic was the cycle of destruction and restoration that Martial and his near-contemporary, the historian Tacitus, felt able to label the arisen city ‘new Rome’.Footnote 5

The Roman concept of ‘restoration’ extended beyond just the reconstruction of buildings, since emperors’ programmes of structural renewal were symbolic of religious, moral, societal and political restoration.Footnote 6 Indeed, a theme that emerged in the time of Rome's first emperor Augustus (27 BC–AD 14) was that the appearance of the city reflected the health of the state and empire overall.Footnote 7

This positive image of urban renewal largely goes unquestioned. Ancient authors, even those who are critical of particular emperors for other reasons, predominantly followed the line that the city, as rebuilt, became better than it was before.Footnote 8 Similarly, modern scholarship on architecture and urbanism in antiquity has focused on building activity and investment in the fabric of cities as positive processes, typically starting from the assumption that such developments were welcomed by inhabitants – but were they?

This article examines objections to the construction of monumental public building in the Roman world. Urban renewal requires change, and this creates winners and leaves losers. While investment in the buildings, amenities and infrastructure of a city might be welcomed by many, likely there are others who are adversely affected by, and object to, these developments. Such situations are very familiar to those who study contemporary urbanism as well as other periods of history, yet it is rarely considered with respect to the Classical world.Footnote 9 The last three decades have produced a wealth of research on Roman cities and the experiences of the people who lived there; expanding this to take into account the potentially negative sides of urban development adds, I would argue, an important new or alternative dimension to our understanding of them. Moreover, ancient cities remain extremely useful models for thinking about trends in urbanism more widely, providing a longer historical perspective.Footnote 10

Specifically, this article looks at an episode from the same period as the authors cited above – the late first/early second century AD – but located outside of the capital Rome. It focuses on the city of Prusa in the province of Bithynia and the controversy surrounding the renovation of its civic centre by a local politician, Dio Chrysostom. Using speeches and letters written at the time, we are able to reconstruct the terms of the debate and the arguments presented in favour of and against the project. I argue that the opposition to Dio's scheme, rather than being motivated by the machinations in local politics – which is how scholars have commonly interpreted the affair – actually reveals a deeper concern among the people of Prusa on historic and religious grounds for the way that their urban fabric was being altered. We can see a conflict between the professed benefits of investment and the construction of an impressive public building, set against concerns for the loss of what is destroyed to make space for it. This article presents a new interpretation of this specific episode and brings to the fore the rarely articulated and yet highly controversial nature of building projects that are traditionally thought of as being beneficial. In the conclusion, we also see how this example contributes to research on the issue of built heritage as a pre-modern phenomenon.

Dio Chrysostom and the stoa in Prusa

In antiquity, Greek cities existed across the Mediterranean world. Outside of the mainland and its surrounding islands, Greek settlements could be found in Asia Minor, North Africa, Sicily, Italy and the south of France. By the second century AD, much of this territory had been part of the Roman Empire for at least two centuries. Yet the local identities of cities as well as the idea of a wider distinct Hellenic (Greek) culture remained important.Footnote 11 Indeed, from the late first century AD onward, there was a significant increase in interest in the question of what being ‘Greek’ meant. Validation and self-definition were sought in the achievements of the past, as Greeks living under Roman rule looked to the culture of their Classical ancestors of five centuries earlier. Scholarship on this ‘movement’ – usually, if problematically, labelled the ‘Second Sophistic’ – has tended to focus on its literary outputs, examining how Greek philosophy and rhetoric of the time were consciously and conspicuously drawing on their distant antecedents.Footnote 12 It is also apparent that historicizing ideas were present in other cultural media, including art and architecture.Footnote 13 We will return to this subject later, but for now, it is enough to note that this was a period when conceptions of the past and the material inheritance of earlier generations played an important role in forming notions of identity in the present.

Dio Cocceianus, also known as Chrysostom (‘golden mouthed’) came from the Greek city of Prusa in present-day Turkey. Prusa was founded at the beginning of the second century BC by the ruler of the Hellenistic kingdom of Bithynia, Prusias I, but was annexed as part of the Roman Empire in the first century BC (Figure 2).Footnote 14 Born in the AD 40s, Dio moved to Rome during the reign of the emperor Vespasian in the AD 70s. A decade later, Dio was banished from both the capital of the empire as well as his native Prusa by Vespasian's second son, Domitian, on the grounds of association with a conspirator against the emperor. Following Domitian's assassination in AD 96, the emperor Nerva annulled Dio's exile, allowing Dio to return to his home city, where he took on an active role in civic matters. Under Nerva's successor, Trajan (AD 98–117), Dio enjoyed favour and fame as an orator, philosopher, literary critic, ambassador and local politician; we hear nothing of him after c. AD 112.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Map of Asia Minor in the second century AD with Prusa highlighted. From F. Yegül and D. Favro, Roman Architecture and Urbanism: From the Origins to Late Antiquity (Cambridge, 2019), xv. Reproduced with the kind permission of the authors.

Approximately 80 public speeches attributed to Dio and delivered between the latter decades of the first century and early second century AD have come down to us. Their subject matter ranges from the nature of kingship to the pursuit of happiness, from arguing that it was actually the Trojans not the Hellenes who won their famous, eponymous war, to current political events at Prusa. Of interest to our purpose is a series of speeches about a building programme that Dio was sponsoring in the city in the first decade of the second century AD.Footnote 16 These were delivered to the civic assembly (ecclesia) of the populace of Prusa, one of the governing bodies of the city, the other being the elite-run council (boule).Footnote 17

Our knowledge about Dio's building projects in the city comes primarily from his own speeches, although some valuable supplementary information is preserved in the correspondence between the emperor Trajan and Pliny the Younger, the Roman governor of Bithynia (c. AD 110–112).Footnote 18 Dio himself speaks of plans to equip Prusa with fortifications, harbours and shipyards, as part of his ambition to establish it as the head of a federation of neighbouring cities – although these schemes remained unrealized pipe dreams.Footnote 19 From Pliny, we learn that Dio certainly constructed or renovated a structure for public use, which contained a library as well as a colonnaded court, in the centre of which was a funerary monument to his wife and son.Footnote 20 The project that we hear most about, reoccurring in four (possibly five) speeches, concerns the construction of a stoa.Footnote 21

Although remains of this stoa have not been discovered (the archaeology of ancient Prusa lies under the modern city of Bursa, see Figure 3), comparative examples both from the time and earlier periods can provide us with some idea of its likely appearance. Stoas were typically long, aisled halls, with a colonnaded porch which opened onto a public square, similar to a Roman basilica. Often rectangular and narrow in form, they could also have an L or Pi shape plan.Footnote 22 Stoas might contain spaces for commercial and administrative activity, with the added benefit of providing shade from the Mediterranean sun. By the second century AD, the term stoa was also applied to structures more akin to colonnaded walkways or porticos flanking streets (see Figures 4 and 5).Footnote 23 Although it is not possible to determine the size of Dio's building, which was accompanied by fountains and shops, we can assume that it was no small undertaking and represented a notable private investment and a concerted effort to monumentalize the city centre.Footnote 24

Figure 3. View of the city, Bursa, Turkey, between 1890 and 1905. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs, [LC-DIG-ppmsc-06054] (http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsc.06054).

Figure 4. The rebuilt second century BC Stoa of Attalos in the Athenian Agora, 1956. Courtesy of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens: Agora Excavations. 2012.01.0056 (80-414).

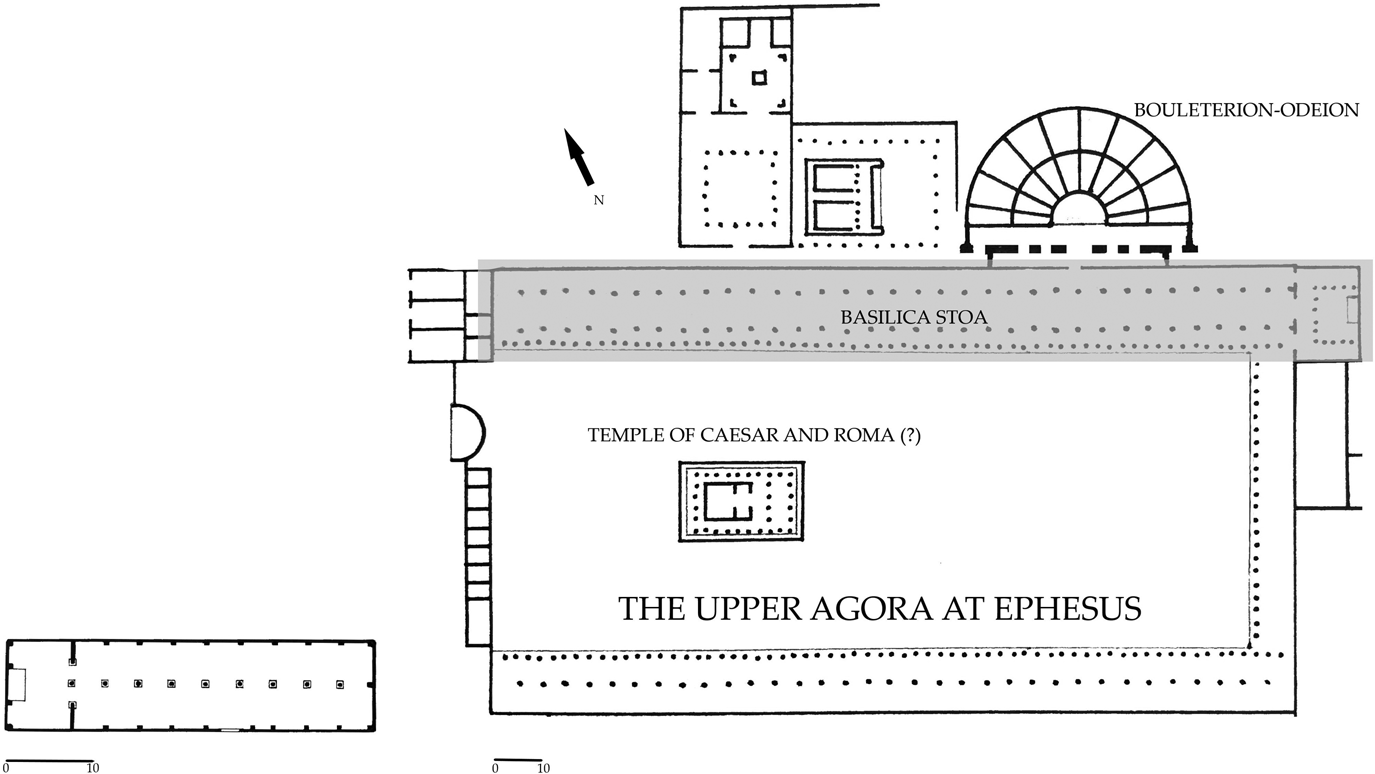

Figure 5. Plans of the stoas at Thera (rebuilt AD 149–161) and Ephesus (early first century AD). Drawn by the author, the latter after F. Yegül and D. Favro, Roman Architecture and Urbanism: From the Origins to Late Antiquity (Cambridge, 2019), figure 10.75.

Euergetism and building activity in Bithynia

Dio's move to enhance the urban fabric of Prusa corresponds to a trend of extensive building activity by local elites, sometimes also supported by financial backing from the emperor, across cities in Bithynia and Asia Minor in this period.Footnote 25 These acts of euergetism – the practice of individuals distributing part of their wealth to the wider community by means of gifts – were likely anticipated to bring advantages to the benefactor, particularly with regard to status, influence, political office and legacy (the nominal point of a monument is to memorialize).Footnote 26 Clearly intended to benefit the inhabitants of the cities, many projects were of a utilitarian nature and included aqueducts, sewers, baths, theatres and stoas.

The effects of such works in enhancing the appearance and status of cities were also very much a consideration. When Pliny, as governor of Bithynia, attempts to persuade the emperor Trajan to support the construction of an aqueduct for the city of Nicomedia, he emphasizes that the finished structure will combine utility (utilitas) with beauty (pulchritudo).Footnote 27 Dio, too, highlights both the usefulness of his stoa in providing shade in summer and shelter in winter,Footnote 28 as well as how it can serve to beautify Prusa.Footnote 29 He also explains that it boosts the dignity of Prusa, as it is becoming of great cities to have great buildings, while those without will always remain stunted.Footnote 30 This outlook relates to the idea, mentioned above, that the prominence of a community should be reflected in the physical appearance of its city; it also speaks to the intense rivalry that existed between the cities of imperial-era Asia Minor and which was sometimes played out in the urban fabric.Footnote 31

Prusa's standing in relation to other cities is a recurrent consideration in Dio's justification of his scheme to the assembly. He expresses the ‘desire to make our city the head of a federation of cities and to bring together in it as great a multitude of inhabitants as I can’,Footnote 32 but bemoans that, when it comes to beautification, ‘we are behind our neighbours’.Footnote 33 Indeed, he frames his building plans against the ambitions of not only notable nearby cities in Bithynia – Nicomedia, Nicaea and Caesarea – but also the more distant, great cities in the provinces of Asia, Syria and Cilicia.Footnote 34 Answering critics who appear to suggest that his projects for the city are too grand, Dio points out that:

One must never curtail a city or reduce it to one's own dimensions or measure it with regard to one's own spirit, if one happens to have a small and servile spirit, particularly in light of existing precedents – I mean the activities of the men of Smyrna, of the men of Ephesus, of those men of Tarsus, and of the men of Antioch.Footnote 35

Grandiose building projects, fuelled by the spirit of competition, might lead to civic improvements, but they could also result in spiralling costs and financial ruin. Indeed, when Pliny was dispatched by the emperor Trajan to take up governorship of Bithynia, it appears to have been partly with a specific remit to sort out the economic mess in the province.Footnote 36 The correspondence between both men provides notable insights into the nature, ambition and potential for mismanagement that surrounded monumental undertakings in various cities.

For instance, Pliny arrives to find that the citizens (or civic authorities) of Nicomedia had spent an enormous 3,318,000 sesterces on constructing an aqueduct before abandoning and demolishing it, only to then spend a further 200,000 on a new one, which was similarly abandoned before completion.Footnote 37 At the city of Nicaea, he found a half-built theatre which had cost 10,000,000 sesterces already and yet now possibly needed to be pulled down due to either the unsuitable terrain on which it was built or the poor quality of the stone that was used.Footnote 38

Emperor Trajan's responses to these and other similar instances indicate that, while there was considerable concern over excessive spending, as well as a wish to hold to account those responsible, it was still desirable for such projects to go ahead if properly managed.Footnote 39 Far from curbing the trend, Pliny as governor encourages Trajan to support further undertakings on the promise that, through their combination of beauty and utility, they will be worthy of his reign and beneficial to the cities in question.Footnote 40

It is therefore in this context of widespread and energetic building activity in neighbouring cities that Dio patronized Prusa with the new stoa. From Pliny's letters, aside from financial concerns and the occasional question over whether the disturbance of religious structures was a sacrilegious violation, there is little indication that such projects might prove controversial. Yet, what Dio's speeches reveal is that urban renewal could indeed be contentious and that his gift of the stoa was not in fact welcomed by all of Prusa's residents.

The terms of the debate: ‘disgraceful, ridiculous ruins’

Dio's addresses to the assembly and people of Prusa were not to promote his project, but to defend it. Indeed, the parts of the speeches which deal with the stoa are composed as a response to various criticisms that had been levelled against him and his building works by others in the city. But, on this matter, we only have Dio's words (along with one letter by Pliny) and so only his side of the debate. Furthermore, the texts were revised before publication and, therefore, Dio is only letting his reading audience know what he wants them to know – in other words, we should not assume they are a verbatim transcription of what was said at the moment of delivery. Nevertheless, from noting the charges that he is attempting to rebut and from reading between the lines of his defence, a picture emerges of his opponents’ concerns and accusations.

It is a mixed bag of charges levelled at Dio: financial irregularities, treason, irreverently destroying parts of the city, sacrilege and overemphasizing the appropriate status of Prusa. We learn about the issue of financial misconduct from Pliny's correspondence with Trajan: shortly after arriving in Bithynia, Pliny reports that, upon investigating the expenditure and revenues of Prusa, he believes that ‘substantial sums of money could be recovered from contractors of public works’ – presumably because of their mismanagement, deliberate or otherwise.Footnote 41 Although there is no definite reason to think that Pliny is here referring to Dio's scheme, Pliny later details how two statesmen of Prusa – Claudius Eumolpus and Flavius Archippus – have requested on behalf of the city that Dio produce the accounts for his buildings works on suspicion of dishonest conduct (it is unclear if the buildings here referred to are part of Dio's stoa project or a different undertaking).Footnote 42 While we do not hear about the outcome of the investigation, it appears that Dio was willing to produce his accounts and attend the hearing, while the accusers attempted to delay proceedings.

Eumolpus and Archippus also claimed that a statue of the emperor Trajan had been placed in the part of the building where Dio had buried his wife and son – technically a treasonable offence.Footnote 43 Yet Pliny reports that, having inspected the building, this was not the case and that the statue was actually located in a library adjoining the space where Dio's relatives were supposedly buried. Based on the evidence in Pliny's letter, which does not present Eumolpus and Archippus in a favourable light, scholars have generally taken the allegations against Dio to be motivated by a local political quarrel.Footnote 44 Likewise, with regard to the stoa project, Jones characterizes the building work as becoming ‘entangled in petty politics’ and Sheppard presents the opposition to it as stemming from the ‘jealousy’ of Dio's enemies – a view frequently followed by others.Footnote 45 Yet, even if that were the case with respect to the claim brought by Eumolpus and Archippus, it does not automatically follow that all criticism of Dio's building activity was disingenuous or a foil, as emerges from his defence of the construction of the stoa.

To an extent, the principal objection seems not to be about what Dio built, but about what he destroyed in order to build. Repeatedly, Dio is forced to justify the tearing down of existing structures so that his new buildings can rise: ‘there was a lot of talk – though not on the part of many persons – and very unpleasant talk too, to the effect that I am dismantling the city; that I have laid it waste, virtually banishing the inhabitants; that everything has been destroyed, obliterated, nothing left’.Footnote 46 The destruction of certain workshops on the site appears to have been the source of particular animosity. This might be because of the resultant changing nature of the district, with commerce and light industry being pushed out as the area was monumentalized. But it is apparent from Dio's complaint that it was also because the buildings were considered by some in Prusa to be historically significant: ‘there were some who were violent in their lamentations over the [removal of] the smithy (χαλκεῖον) of So-and-so, feeling bitter that these memorials of the good old days were not to be preserved’.Footnote 47 Dio's sarcasm is palpable, but it suggests that some people did regret the loss of these structures and did regard them as ‘memorials of the good old days’. Dio justifies his actions by comparing the benefits of the stoa to the appearance of the former buildings on the site: ‘There is advantage when a city becomes good-looking, when it gets more air, open space, shade in summer and in winter sunshine beneath the shelter of a roof, and when, in place of cheap, squat wrecks of houses, it gains stately edifices that are worthy of a great city.’Footnote 48 Dio is relentless in his scathing put-downs of what he deems to be valueless structures and the hyperbolic reaction to their removal:

One might have supposed that the Propylaea at Athens were being tampered with, or the Parthenon, or that we were wrecking the Heraeum of the Samians, or the Didymeium of the Milesians, or the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, instead of disgraceful, ridiculous ruins, much more lowly than the sheds under which the flocks take shelter, but which no shepherd could enter nor any of the nobler breeds of dogs, structures that used to make you blush, indeed, be utterly confounded when the proconsuls tried to enter, while men who bore you malice would gloat over you and laugh at your discomfiture – hovels where even the blacksmiths were scarcely able to stand erect but worked with bowed head; shanties, moreover, in tumbledown condition, held up by props, so that at the stroke of the hammer they quivered and threatened to fall apart. And yet there were some who were distressed to see the signs of their former poverty and ill-repute disappearing, who, far from being interested in the columns which were rising or in the eaves of the roof, or in the shops under construction in a different quarter, were interested only in preventing your ever feeling superior to them.Footnote 49

There is a lot to consider in this excerpt and we shall come to the comments on buildings in other Greek cities. First, by presenting the near-derelict nature of the buildings, Dio is both amplifying their worthlessness as well as appealing to an ideological aversion to ruins that was prevalent at the time.Footnote 50 In Roman Italy, decrees of the first and second centuries AD relating to the pulling down of privately owned or public buildings in towns and cities contained the important clause that reconstruction must follow demolition, the partial purpose of which was to try to ensure a degree of protection for the appearance of the cityscape.Footnote 51 Hence, a law issued by the Senate in AD 46 warned that the pulling down of structures can create ‘an appearance (faciem) most incompatible with peace’.Footnote 52

We also know from Pliny of a separate but contemporary project in Prusa to rebuild a public bathhouse on a new site.Footnote 53 Pliny tells the emperor Trajan that the chosen site is currently occupied by the ‘unsightly ruins’ (deformis ruinis) of an old house now in public ownership, and that by constructing the new bath on this site ‘we could thus remove this eyesore and embellish the city without pulling down any existing structure; indeed, we should be restoring and improving what time has destroyed’.Footnote 54 Pliny claims there is municipal support for this scheme and it is interesting that he specifically notes that there are no existing or functioning buildings to be pulled down, only unoccupied ruins.

By contrast, Dio is said to be destroying actual buildings still in use, which accounts both for some of the objections to his scheme, and for his efforts to cast the existing structures as already in a ruinous condition. Yet, for all Dio's belittling of the structures that are being destroyed, his protestations in themselves make it apparent that people did care about, and even attached historical and culture value to, the buildings.

The terms of the debate: sacrilege

A further charge Dio defends himself on is that of sacrilege. Qualifying the effects of his scheme on the existing fabric of Prusa, Dio points out that the people of Antioch, Tarsus and Nicomedia must have destroyed or moved shrines and tombs when they carried out their own extensive programmes of urban renewal.Footnote 55 Turning to earlier developments in Prusa, he points out that a certain Macrinus, ‘whom you have recorded as a benefactor of the city, removed from the market-place the tomb of King Prusias, and his statue as well’.Footnote 56

That Dio feels compelled to document these precedents for the removal of inviolable structures (temples and tombs) suggests that his own clearance operations affected some sacred edifices and not just the ‘smithy of So-and-so’. Indeed, he goes on to claim that he is being accused of ‘tearing down the city and all its shrines’, sarcastically stating ‘for of course it was I who set fire to the temple of Zeus! Not that I saved the statues from the scrap pile, and placed them in the most conspicuous spot in the city.’Footnote 57 From this, we might deduce that a temple of Zeus had caught fire and had not been rebuilt, since the surviving statues were relocated. While there is no need to presume Dio did burn down the temple of Zeus – as he evidently appears to be accused of – the necessity of making this defence does hint at the possibility that his project was going up in place of where it once stood.

From Pliny, we learn of other instances of shrines being moved or removed as part of urban regeneration schemes in the province, and the seriousness with which this was taken. Writing to Trajan, he asks:

Before my arrival, sir, the citizens of Nicomedia had begun to build a new forum adjacent to their existing one. In one corner of the new area is an ancient temple of Magna Mater, which needs to be rebuilt or relocated to a new site, mainly because it is much lower than the buildings now going up. I made a personal inquiry whether the temple was protected by any specific condition, only to find that the form of consecration practised here [in Bithynia] is quite different from ours [in Rome]. Would you then consider, sir, whether you think that a temple thus unprotected can be moved without loss of sanctity? This would be the most convenient solution if there are no religious objections.Footnote 58

Likewise, concerning the bathhouse that Pliny was proposing to build in Prusa on the land where a ruined house stood, he reports to Trajan the will of the former owner that had stipulated that the house and land be donated to the city and that a shrine to the emperor Claudius be erected there.Footnote 59 In his response, Trajan approves replacing the ruined house with a new bath complex but expresses concern that any land occupied by the shrine should remain inviolate.Footnote 60

It is clear that shrines could be removed when civic improvements necessitated it, but that there were also processes for doing this, and that it could be a matter of such importance that the emperor (who was also the Pontifex Maximus – ‘High Priest’) would have to be consulted.Footnote 61 Therefore, even if we presume that Dio did not deliberately burn down the temple of Zeus, the objections to his scheme on religious grounds should be considered as serious.

A sacker of cities: Dio as Nero

The content of Dio's defence also allows us to partially reconstruct the rhetoric of the other side. Dio states he has been labelled ‘a sacker of cities and citadels’ and that ‘some persons say I am acting the tyrant and tearing down the city and all its shrines’.Footnote 62 Dio is not simply presented as an unsympathetic developer – he is cast as an actual enemy of Prusa. This image is underlined by the accusation elsewhere that he is an ‘outsider’, which refers to his long absence from the city and contributes to the impression of his disregard for local sensibilities.Footnote 63

The apparent characterization of Dio by his opponents as a conquering oppressor who ‘laid the city waste, virtually banishing the inhabitants; so that everything has been destroyed, obliterated, nothing left’ is unduly hyperbolic. In fact, the language is reminiscent of urbs capta motifs, a type of imagery employed by ancient authors to convey the violence of a city being sacked.Footnote 64 The phraseology associated with urbs capta is typically used in reference to the events of wars, which therefore only adds to its potential potency when applied to a situation such as Dio's supposedly beneficial urban renovation project.

Interestingly, Dio's contemporaries in Rome drew upon the same technique to frame the emperor Nero's actions during the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, which he was widely accused of having started.Footnote 65 The historian Tacitus (writing in the 110s) presents the Neronian fire as a vivid disaster narrative in the manner that he uses elsewhere to describe the sack of towns by enemy action, thus casting Nero as a tyrannical foe of the city.Footnote 66 The biographer Suetonius (c. AD 70–c. 130) likewise alleges that Nero aided the destruction wrought by the fire upon the capital through employing siege engines to clear structures.Footnote 67 Indeed, in claims reminiscent of Dio's justification for clearing the ‘smithy of So-and-so’, Suetonius asserts that it was due to the ugliness of the old buildings that Nero destroyed Rome so that he could replace them with something better – including, of course, his vast palace, the Domus Aurea. Correspondingly, we recall that Dio appears to have been accused of deliberately burning the temple of Zeus, which then permitted the construction of his own building project. Indeed, at one point, Dio has to assert that what he plans for the city of Prusa is explicitly not something akin to Nero's Golden House.Footnote 68

Whether Nero deliberately set fire to Rome or not – and if he did, whether it was for the reasons stated above – is not immediately relevant to this discussion. What matters is how his actions were presented by contemporaries and subsequent generations. We do not need to imagine any direct literary interaction between Tacitus and Suetonius in Rome and Dio's critics in Prusa, but they are clearly drawing on the same imagery by characterizing urban renovation as urbs capta, which is suggestive of a broader shared idea that renewal and destruction were recognized as having the potential to be two sides of the same coin.

Conclusion: the destruction of heritage

The importance of this episode is that it shows us the alternative side to activity that is almost always thought of in positive terms in discussions about ancient cities. Through Dio's speeches we can reconstruct the details of a debate which reveals the contentiousness that might accompany urban renewal, giving voice to a side of the argument which is commonly lost from our records.Footnote 69 Because such opinions are not detectable in the archaeological record, there is a temptation to assume that investment in building projects – the erection of grander structures in place of materially poorer ones – would have been universally welcomed. What we can infer from the speeches of Dio is that this was not necessarily the case and it should encourage a reassessment of assumptions that the benefactions of public buildings in cities were unquestioningly beneficial to those who lived there.Footnote 70 Such situations are perhaps familiar to readers who study cities in other historical periods and the contemporary world, but this present discussion helps provide a longer historical perspective on this issue.

There is also scope for developing the subject further in the study of Roman architecture and urbanism, exploring new lines of research that look beyond patrons and builders to consider the reception of monuments in society more widely.Footnote 71 For, although it is unknown who exactly these people were (except for in the separate legal case brought by Eumolpus and Archippus), we can note that the opposition is raised by the popular assembly.Footnote 72 The assembly was not a democratic body in the modern sense (membership was limited to adult male citizens and also likely further restricted by a property qualification), but it was nevertheless more representative of the wider population of Prusa than the smaller, elite-dominated council.Footnote 73

The terms of the debate about Dio's stoa in Prusa are also significant. As seen above, scholars have tended to ascribe the cause of opposition to Dio's building projects to internal Prusian politics, marginalizing the concerns about the treatment of the historic built environment. For example, on this episode, it has been asserted recently ‘that sentimental attachments to landmarks such as the “smithy of So-and-so” as memorials should not be viewed as manifestations of genuine nostalgia, but instead should be understood as flimsy excuses for political or personal enmity. There was clearly no strong impulse for architectural preservation felt by patrons who sought to update the physical image of their cities.’Footnote 74

While political intrigues quite possibly had an influence on proceedings (particularly regarding the documented charges brought by Eumolpus and Archippus), they were not mutually exclusive and there is no obvious reason not to accept the protestations over the destruction of historical and religious heritage at face value. Even if certain patrons (in this case, Dio) were seemingly ambivalent about preservation, it does not mean that everyone was. Irrespective of whether there were deeper political motivations, the very fact that objections on these grounds could be made demonstrates that the issues were conceivable.

That such attitudes existed are apparent from other examples in the Hellenic world, where structures linked to the past were valued and preserved on historic grounds, even when in a ruined state. Approximately 50 years after Dio delivered his orations, the Greek author Pausanias wrote the Hellados Periegesis, a detailed, if selective, description of cities and places he had visited in mainland Greece. At Olympia, the site of the eponymous games, he describes the different features of the sanctuary, including the remains of the house of Oenomaus:

What the Eleans call the pillar of Oenomaus is in the direction of the sanctuary of Zeus as you go from the great altar. On the left are four pillars with a roof on them, constructed to protect a wooden pillar which has decayed through age, held together by bands. This pillar, so goes the tale, stood in the house of Oenomaus. Struck by lightning the rest of the house was destroyed by the fire; of all the building only this pillar was left. A bronze tablet in front of it has the following elegiac inscription:

‘Stranger, I am a remnant of a famous house,

I, who once was a pillar in the house of Oenomaus;

Now by Cronus' son [Zeus] I lie with these bands upon me,

A precious thing, and the baleful flame of fire consumed me not.’Footnote 75

Oenomaus, a son of the god Ares, is a figure of myth. Purportedly having lived in the thirteenth or twelfth century BC, it was claimed that he was the king of Pisa, the polis that once controlled Olympia; according to tradition, it was in his honour that the games were established. Given that Oenomaus was a fictional person, the pillar was evidently not an actual remnant of Oenomaus’ house; yet the relevant point is that Pausanias’ contemporaries at Olympia believed it to have been so and took active – and advertised – steps to preserve it because of this association.Footnote 76

Heritage is not a modern phenomenon, as is sometimes presumed. Scholars of heritage studies are primarily occupied with recent activity and tend to place the origins of the concept of heritage in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 77 Yet, as argued elsewhere, there is little in many recent definitions of the term to restrict its application to near-contemporary history.Footnote 78

The ancients consciously engaged with the material past for purposes in their present. Greeks in the second century AD were highly aware of the historic built environment in which they lived, and they discussed, conserved, restored, and rebuilt aspects of it accordingly.Footnote 79 This does not mean that their concept of heritage or attitude to restoration is analogous to more modern ideas and approaches, of course, but the example of Oenomaus’ house, for one, demonstrates that structures could be valued on historic grounds. It is perfectly plausible that people in Prusa, too, deemed structures in their city historically significant, with the unapologetic demolition of such by an ‘outsider’ provoking genuine outrage.

Indeed, what emerges from Dio's speeches is the tension between a vision of Prusa as a global city and the concerns of the inhabitants for things happening at a local level. Dio places his project in the context of competition with the building schemes occurring in other cities in Bithynia and Asia Minor. Moreover, in an earlier quotation, we saw Dio attempting to undermine the complaints against his stoa by contrasting the ‘disgraceful, ridiculous ruins’ that had been pulled down in Prusa, with the Propylaea (monumental gateway) and temple of Athena Parthenos at Athens, as well as temples of Hera at Samos, of Apollo at Didyma and Artemis at Ephesus.Footnote 80 These are among the most famous and, by the time of Dio, the most canonical Classical-era buildings of the Greek world. All date to the sixth and fifth centuries BC, and by the late first century AD they had all come to represent ideas of Greek history, prestige and identity.Footnote 81 In these ways, Dio is appealing in his orations to ideas of a wider Hellenic heritage – geographical and temporal – as justification for his actions in Prusa. This is at odds with the objections to the stoa, which are centred around local heritage – a contention which seems disconcertingly familiar and again underscores the relevance of antiquity in providing a longer historical perspective to other disciplines and contemporary issues.