When compared with the other case studies analysed in this book, the role played by private health insurance in Switzerland may seem peculiar and perhaps corresponds only with the Netherlands post-2006 (see Chapter 11). The crux of the Swiss health sector is a system of federally established universal health insurance coverage with atypical characteristics lying somewhere between private and social insurance (OECD 2006; Leu et al., Reference Leu2007).

Swiss statutory health insurance is run by competing private institutions called sickness funds. It is strongly reliant on consumer choice and mainly financed through non-income-related premiums. Consumers (not employers or the government) buy health insurance plans, pay the bulk of health care costs through insurance premiums, co-payments and out-of-pocket payments, and choose the size of the deductible and other characteristics of the plan according to their own needs and preferences. Health insurers, whose business providing basic coverage is framed by social law, are also entitled to make profits by selling voluntary supplementary and complementary coverage governed by private law.Footnote 2 From this perspective, health insurance in Switzerland conceptually belongs within the scope of private insurance.

However, many features distinguish the Swiss case from classic private health insurance: since 1996 Swiss citizens have been mandated to purchase a comprehensive package of health care benefits; insurer activity in the domain of mandatory health insurance is managed in accordance with non-profit regulations; risks are adjusted between sickness funds by means of a risk equalization mechanism; premiums and enrolment are highly regulated by the state; and earmarked subsidies are designed to help people with a low income to pay their health insurance premiums. From this perspective the characteristics of the sector are similar to those of social insurance (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson2013).

The ambiguity of the Swiss health insurance system was highlighted in two articles published in the same issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association (Reference Herzlinger and Parsa-ParsiHerzlinger & Parsa-Parsi, 2004; Reference ReinhardtReinhardt, 2004). Although considering the same set of facts, the two articles proposed radically different hypotheses and explanations of the (alleged) superior performance achieved by the health care sector in Switzerland when compared with the United States. According to Herzlinger and Parsa-Parsi, Switzerland’s good performance is supposedly rooted in the significant role consumers play in paying for health care and the resulting high cost transparency, which leads to effective cost control and enables citizens to obtain what they consider to be good value for money. The interpretation offered by Reinhardt is diametrically opposite: he argues that the performance of the Swiss health care system must be ascribed to pervasive government regulation. Both articles, however, underestimate the importance of the particular political and social context in which the health sector in Switzerland is embedded.

This chapter aims to illustrate how the institutional peculiarities of the Swiss political system, combined with the hybrid health insurance model, result in a weakened role for both health insurance competition and state regulation. The organization of the Swiss health sector reflects at least three fundamental factors (Reference Achtermann and BersetAchtermann & Berset, 2006: 20): (i) a strongly decentralized political system, based on federalism, subsidiarity and the institutions of direct democracy; (ii) a liberal economic culture, which emphasizes freedom of choice and consumer-driven economic decisions; and (iii) a unique historical path for social security, in which non-profit institutionsFootnote 3 led to the creation of a voluntary insurance sector and continue to influence the current system of universal coverage.

The Swiss health insurance sector relies on the principles of regulated competition, which plays out within a national regulatory framework, but mostly at the cantonal (decentralized) level.

To better understand this puzzle, the chapter is organized as follows: the second section presents some discussion of the history of the Swiss health insurance system; the third section describes the principal changes introduced by the 1996 Federal Health Insurance Act [Krankenversicherungsgesetz (KVG)]. The fourth section assesses the performance of the present system, focusing on market structure, premium growth, financial sustainability, risk pooling, switching behaviour, risk selection and innovation. The chapter ends with analysis of the role played by direct democracy in defining the particular dynamics of reform pursued by the health insurance sector in Switzerland and outlines future scenarios.

Historical development of statutory health insurance in Switzerland

In order to understand why the Swiss model of health insurance is so different from the global pattern it is necessary to consider the particular role played by Swiss social culture and political institutions since the 19th century. In this context the relevance of federalismFootnote 4 and the significance of the institutions of direct democracyFootnote 5 and a solid tradition of mutual benefit organizations in civil society must be borne in mind. From the beginning of the 19th century various examples of mutuality and cooperation among citizens sprang up, leading to the spontaneous formation of numerous mutual support groups. The assessment of these initiatives by social scientists is not conclusive. In similar initiatives all over the world many authors see the principles of reciprocity and solidarity of the cooperative movement and civil economy at work (Reference Bruni and ZamagniBruni & Zamagni, 2007), with citizens organizing themselves from the bottom up to face emerging problems of unemployment, disability and sickness collectively. However, other authors interpret these initiatives as the adulteration of what began as an instrument of political and trade union struggle into a powerful means of promoting “a pedagogy of providence able to guarantee the integrity of an economically liberal social order” (Reference MuheimMuheim, 2003: p.22). What is not contested is that the existence of these mutual support groups strongly conditioned the fundamental choices of the Swiss welfare system, which was coming into being (Gilliand, Reference Gilliand1986: pp.247–60).

At the beginning of the 20th century four kinds of mutual support groups could be clearly distinguished in Switzerland, and their origins are still recognizable in the names of some of today’s sickness funds:

professional funds, linked to the trade union world and therefore limited to trade union members;

company funds (Betriebskrankenkassen), realized by the initiatives of philanthropic capitalists, intended for the employees of a given firm;

confessional funds, promoted within Catholic confraternities and inspired by the social doctrine of the Church;

public funds (the öffentliche Krankenkasse), created by a canton, a regional district or a municipality (Dorfkrankenkassen, Bezirkskrankenkassen).

While membership of the first three types of funds was restricted to people belonging to a particular category, in public funds affiliation was theoretically open and linked only to place of residence. However, even in the public funds, membership was often subordinated to the moral integrity of the person and to his/her favourable personal situation (good health status, not too old).

A census held in 1903 counted 2006 mutual support groups, to which 14% of the population were affiliated (about 500 000 people).Footnote 6 Half of the groups had fewer than 100 members and grouped together the inhabitants of one municipality. The risks they attempted to guard against were not limited to sickness (nine mutual groups out of ten offered cover against health risk, usually in the form of a daily cash benefit),Footnote 7 but also included death (assistance to widows and orphans) and long-term unemployment. Years earlier, in 1899, the federal assembly had approved a draft bill (Lex Forrer) which envisaged setting up a decentralized system of public funds, jointly financed by the insured and employers and organized on a territorial basis starting from a minimum number of 1500 insured (Reference Knüsel and ZuritaKnüsel & Zurita, 1979; Gilliand, Reference Gilliand1990). Undoubtedly it was a more modern and rational system of health insurance, following the Bismarck model. However, a referendum was launched against it and it was clearly rejected in a popular ballot in May 1900.

From the ashes of that ballot, the first federal Law on Sickness and Accident Insurance (Kranken- und Unfallversicherungsgesetz (KUVG)) developed a decade later. It was accepted by parliament in 1911 and approved by the people in 1912. The legislature realized that to overcome the obstacle of direct democracy and introduce a federal law on the subject of health insurance it was necessary to leave the management of the sector in the hands of private institutions and respect the cantonal autonomy that is particular to federalism. This lesson, as we will see below, lasted throughout the entire 20th century and still casts its shadow on present-day political choices.

Unlike the model set up by Bismarck in Germany, with the KUVG the Swiss legislature relinquished the idea of making health insurance compulsory on a national scale, leaving the cantons to decide whether to make it compulsory at cantonal level.Footnote 8 Instead, they opted for voluntary individual affiliation by citizens and flat-rate premiums not related to income, whose values were established by each sickness fund and adjusted for age and gender. To reduce the financial fragility of the sickness funds and to stimulate voluntary affiliation the state decided to participate in the financing of premiums with public money, by transferring a lump-sum per person subsidy to the sickness funds.Footnote 9 In order to qualify for subsidies, sickness funds had to: accept any national below a certain age limit (usually 55 years), regardless of health status and sex; allow a change of sickness fund if justified (for example, by marriage or change of domicile); and limit the premium surcharge for female members (compared with males of the same age) to 25%Footnote 10 (Zweifel, Reference Zweifel and Scheffler1990: p.80). Finally, to encourage the early enrolment of the young, the KUVG obliged sickness funds to rate premiums on the basis of member age at the time of enrolment. Those who joined the fund at the age of 25, and thus contributed to the insurance fund from an early age, would continue to pay the premiums reserved for this age class for the rest of their lives provided they did not switch funds. The earliest statistics available show that about half the population was insured in 1945, while nearly universal coverage was achieved between 1985 and 1990. By this time premiums had lost any reference whatsoever to the actual age and risk profile of the insured, making switching to another insurer somewhat expensive for older people who had joined the sickness fund when young.Footnote 11

The strong corporative organization of sickness fundsFootnote 12 led to the adoption of important restrictions to market competition in the health insurance sector (Swiss Antitrust Reference CommissionCommission, 1993: pp.77–85). Explicit comparisons of benefits and premiums among insurers, as well as poaching customers from other members of the Sickness Funds Association, were forbidden. Moreover, provider fees were established by collective contracting as a result of bargaining at cantonal level between the medical association and the federation of sickness funds. As sickness funds could not differ in the set of contracted doctors and hospitals nor in the level of fees, there were limited opportunities for a single sickness fund to widen its own market. Just one strategy was left open to them: to compete on the basis of the size of the benefit package. Because the benefit package was not defined in the form of a positive list, insurers started to enlarge the range of covered services beyond the minimum standard established by the 1964 revision of the law (Reference SommerSommer, 1987: pp.51–3; Reference Alber and Bernardi-SchenkluhnAlber & Bernardi-Schenkluhn, 1992: pp.213–17). Another form of competition was the promotion of collective insurance contracts for members of specific organizations, particularly companies employing low-risk workers.Footnote 13

Competition among insurers became particularly pernicious at the beginning of the 1990s, when some new companies began to attract younger cohorts by exploiting the premium-setting regulations. Seventy-five years after the introduction of the KUVG a large portion of the clientele of the old sickness funds consisted of people who had been paying contributions for decades (Reference SommerSommer, 1987: pp.54–7). New companies began to cream-skim through full-scale promotion of their own products at particularly convenient youth-oriented premiums.Footnote 14 Not all younger citizens could resist the temptation of fleeing the burdensome solidarity required by the old sickness funds, in which they were required to subsidize the health care cost of older people. Following this exodus of the young, the average risk profile in the historical funds worsened, forcing administrators to increase premiums generally, so pushing more and more low-risk individuals out of these funds (Reference SommerSommer, 1987: pp.55–9; Beck & Reference ZweifelZweifel, 1998). In 1993, acting with the right of emergency powers, the federal government took remedial action to prevent an insurance death spiral, which would have completely segregated the high-risk insured. These new regulations mandated the sickness funds’ participation in a risk-adjustment mechanism based on age, gender and canton of residence (Reference BeckBeck, 2000; Beck et al., Reference Beck2003), thus halting the segmentation of risks.Footnote 15

The Federal Health Insurance Act (KVG) was approved following a referendum in 1994Footnote 16 and came into force in January 1996. The next section describes this new legal framework.

Organization of health insurance in the 1996 Federal Health Insurance Act

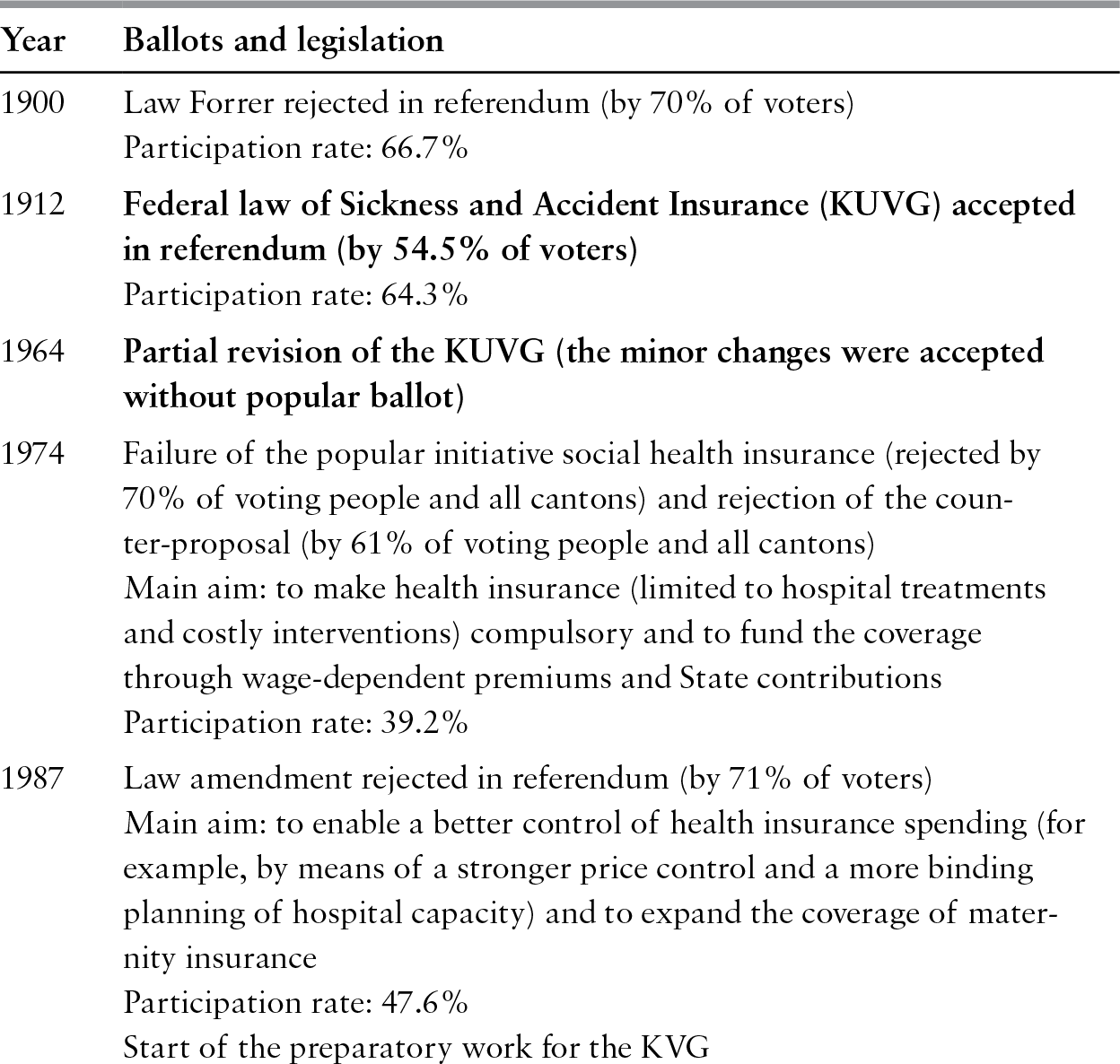

The introduction of the KVG in 1996 marked a turning point for the Swiss health care system; not only was this the first radical reform at federal level after more than 80 years of immobilization (Table 14.1), but the Act also had enormous implications in terms of both intergovernmental task-allocation and the role of competition in the Swiss health insurance sector. The reform objectives, laid out in the Federal Council’s bill of 8 November 1991, could be grouped into four broad categories: (i) strengthening solidarity (in relation to the previous legal framework); (ii) enhancing healthy competition among sickness funds; (iii) filling existing gaps in the benefit package by guaranteeing high-quality services; and (iv) containing health spending.Footnote 17 These objectives were pursued with a mixed strategy, strengthening the role of competition and giving major recourse to planning and regulatory interventions by virtue of a bill that underwent several adjustments to overcome the obstacle of a referendum.Footnote 18

Table 14.1 History of popular ballots and legislative reforms in the field of federal health insurance in Switzerland, 1900–2014

Source: Author.

Note: Initiatives and referendums passed are in bold.

Strengthening competition among health insurers

With the aim of strengthening competition, the Swiss legislature drew inspiration from the model of managed competition.Footnote 19 To enforce such a system, the role of the exit reaction mechanismFootnote 20 This terminology stems from Reference HirschmanHirschman (1970). › was reinforced by making the switch from one health insurer to another even easier than it has been in the past. One of the major changes introduced in 1996 was the establishment of a uniform statutory health insurance contract at national level. The contract obliged each health insurer to:

guarantee the same benefit package (quite comprehensive in comparison to other OECD countries)Footnote 21 See Reference Polikowski and Santos-EggimannPolikowski & Santos-Eggimann (2002).› to all people living in Switzerland;Footnote 22

openly enrol anyone unconditionally and define premiums based on community rating at the regional level (all people aged more than 25, living in a given region and insured by a given sickness fund would pay the same premium);

establish the same minimum amount of financial risk to be borne by the insured; since 2004 there has been a minimum annual deductible of 300 Swiss francs (Sw.fr.) (around €275)Footnote 23 and, for yearly health expenditure exceeding the deductible there is coinsurance of 10% up to a maximum amount of Sw.fr.700 (around €640) per year;Footnote 24

offer homogeneous quality of health care services because the law (as in the previous legislation) forces each health insurer to contract with all hospitals and physicians operating in the market (compulsory contracting).Footnote 25

As a result of contract standardization, basic health insurance offered by each sickness fund can be assumed to be completely homogeneous, such that competition between health insurers should play out at the level of the quality of administrative services provided (time taken to reimburse bills, client support, etc.) and based on the price of the policy (the flat-rate premium established by each insurer in a particular canton). In order to facilitate switching between sickness funds, the insured have the opportunity to change insurer twice a year (on 1 January and 1 July).Footnote 26

Beside this form of radical exit (that is, switching between sickness funds), the federal law also facilitates two methods of partial exit (Reference GerlingerGerlinger, 2003; Reference Crivelli, Bolgiani, Okma and CrivelliCrivelli & Bolgiani, 2009). First, the insured can choose to bear a higher amount of risk, by selecting a higher deductible, in exchange for a premium discount. Choice of deductible is considered to be an instrument to limit moral hazard and increase individual responsibility. To reduce risk selection, the Swiss law establishes a maximum annual deductible of Sw.fr.2500 (about €2288) and maximum premium discounts associated with different deductible levels. Second, insurers can complement the ordinary policy by designing alternative managed-care-style insurance contracts, which limit choice of provider: Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO), Preferred-Provider Organizations (PPO) and Independent Practice Associations (IPA), which are networks of family doctors.Footnote 27 In exchange for a discount on the flat-rate premium, insured people can exit from the classic contract and select a managed-care insurance contract. In theory these alternative forms of insurance, while reimbursing the same range of services, should contribute to bringing health care costs under control through instruments such as selective contracting, gatekeeping, the use of guidelines, the introduction of bonus–malus systems,Footnote 28 and disease and case management programmes. The 1996 reform was based on the assumption that over time the insured would become more sensitive to differences in premiums and, therefore, more mobile. It also expected that greater use of the exit mechanism would encourage insurers to invest more in controlling moral hazard by developing and advertising these new insurance products.

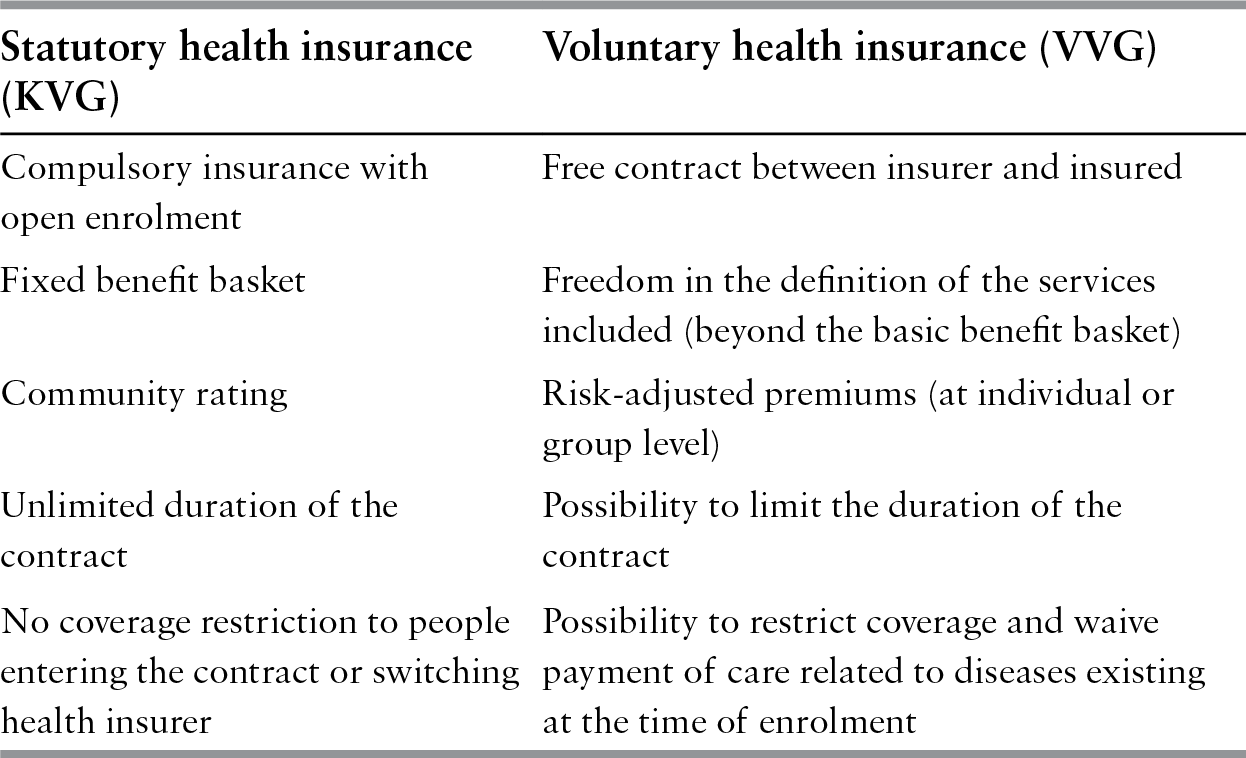

Separation of two realms of activity: social (statutory) versus private (voluntary) insurance

From the beginning of health insurance in Switzerland statutory cover by the sickness funds was offered alongside private insurance policies. Sickness fund cover was governed by the Social Insurance Law, within the framework of the KUVG, and controlled by the Federal Social Insurance Office, while private insurance policies were sold by companies operating in the life or non-life insurance sectors, governed by private law and subject to less strict control by the Federal Office of Private Insurance.

Historically, two types of quite distinct institutions operated within the field of health insurance: one of a non-profit nature (with the benefit of direct public subsidies and tightly controlled) and the other of a for-profit nature with decidedly less rigid legal constraints. Under KUVG regulation the legal status of most of the sickness funds was that of an association, foundation or cooperative, or they were local public institutions.Footnote 29 The enactment of the KVG in 1996 brought about a profound change in this traditional distinction. Instead of distinguishing institutions on the basis of legal status (non-profit versus for-profit), the new system differentiates two realms of activity: social insurance and private insurance. Accordingly, since 1996 social insurance (which includes statutory health insurance and voluntary cash benefit insurance) can be provided by any institutional form. All institutions operating in the compulsory social insurance sector come under the tight control of the Federal Office of Public Health and are obliged to comply with the more restrictive regulations of the KVG.Footnote 30 Conversely, institutions offering voluntary insurance products are rooted in the private Law on Insurance Contracts (Versicherunsgvertragsgesetz) and supervised today by the Swiss Financial Markets Supervisory Authority.

As of 1996, therefore, sickness funds have been authorized to operate in the profit-oriented voluntary insurance sector as well. In the meantime, several mandatory health insurers created independent branches to operate with more leeway in the market for voluntary health insurance. In 2016, 30 mandatory health insurance companies (party directly, partly through independent branches) offered supplementary voluntary health insurance, whereas the number of insurance companies exclusively offering voluntary health insurance was 26. The possibility given to so-called social insurers to offer contracts under private law creates major problems in terms of patient mobility and risk selection, particularly for those who have or wish to buy voluntary insurance.Footnote 31 According to a comprehensive analysis of the sector (Reference Hefti and FreyHefti & Frey, 2008), in 2007 about 70% of the sickness funds (mainly small and operating at the regional level) had maintained their initial legal status. The remainder had become stock companies;Footnote 32 these are mostly active across the whole country and together cover two thirds of the population.Footnote 33 Table 14.2 summarizes the most important differences between compulsory social and voluntary private insurance contracts.

Table 14.2 Main differences between statutory health insurance and private voluntary insurance in Switzerland

| Statutory health insurance (KVG) | Voluntary health insurance (VVG) |

|---|---|

| Compulsory insurance with open enrolment | Free contract between insurer and insured |

| Fixed benefit basket | Freedom in the definition of the services included (beyond the basic benefit basket) |

| Community rating | Risk-adjusted premiums (at individual or group level) |

| Unlimited duration of the contract | Possibility to limit the duration of the contract |

| No coverage restriction to people entering the contract or switching health insurer | Possibility to restrict coverage and waive payment of care related to diseases existing at the time of enrolment |

The domain of voluntary insurance can be divided into three distinct product lines, each one accounting for about one third of premium revenues:

supplementary hospital insurance, which offers free choice of hospital across all cantons,Footnote 34 free choice of physician in public hospitals and higher standards of hotel comfort in private and semi-private wards

cover of services not included in the compulsory benefit package (for example, complementary medicine performed by (non-physician) therapists, dental care and home care beyond the standard covered by compulsory social insurance)

daily cash benefits insurance.

As far as supplementary hospital insurance is concerned, in 2014 12% of the population owned a policy sold by a sickness fund operating in the mandatory health insurance sector and covering access to private or semi-private wards.Footnote 35 The first two product lines are dominated by sickness funds, whereas private insurers have a significant market share in the more complex daily cash benefits and voluntary group insurance sectors (that is, employer-driven contracts).

Overall, two distinct trends can be seen in the voluntary health insurance market. First, voluntary health insurance revenues have grown more slowly than for mandatory health insurance. Between 2000 and 2014 premium revenues increased by Sw.fr.1.2 billion for the first two product lines and by Sw.fr.1 billion for cash benefits, whereas mandatory health insurance premiums grew by Sw.fr.12.4 billion. During the same period voluntary health insurance premiums declined as a proportion of total health insurance revenues, from 34% to 27%. Many companies today are not willing to offer voluntary cover to older people, while the young, who are faced with the heavy burden of mandatory insurance, increasingly choose not to take out voluntary cover for hospital care as long as they are in good health. The consequence of this trend is a worsening of risk pooling.

Second, the sickness funds’ share of the voluntary insurance sector has fallen. In 1997, 89% of those with voluntary cover for private or semi-private wards in hospital had a policy with a sickness fund. By 2006 this proportion had declined to 43%. The market shares of sickness funds in terms of voluntary health insurance premium revenues declined between 2000 and 2014 from 57% to 16% (own computation based on FOPH, 2016a: table 911b). These data conceal a very specific strategic choice: many sickness funds have decided to give up the voluntary insurance sector and have set up separate companies to which they have transferred their private portfolios. In this way, organizations that manage private insurance contracts can avoid being monitored by both agencies regulating health insurance, making themselves subject only to the less severe of the two.Footnote 36

Devolution of competences to the federal government

Historically, the organization of the health system has come under the control of the cantons. Over time, decentralization of competences, ample autonomy of the cantonal governments in public spending decisions and fiscal federalism have created significant differences among cantons with respect to per person health care spending, regulatory setting, the role of the private versus public sector and the level of production capacity (Reference Vatter and RüefliVatter & Rüefli, 2003; Reference Crivelli, Filippini and MoscaCrivelli, Filippini & Mosca, 2006). Instead of a single health care system, Switzerland is composed of 26 subsystems, connected to each other by the KVG. However, although each canton is formally responsible for ensuring access to good quality health services, the KVG has shifted the balance of power from the cantons to the Confederation. Health insurance is now compulsory at the federal level and the Confederation defines the benefit package guaranteed to each resident.Footnote 37 In effect, health insurance is a public service institutionalized at national level to which all citizens have universal access. The public service is financed by two instruments: compulsory insurance supplied by private sickness funds within the framework of the KVG and the public spending of the cantonal and municipal authorities. The latter is financed by general local government taxation and used to subsidize providers who offer services included in the compulsory benefit package (for example, hospitals of public interest, public nursing homes, public and non-profit home care institutions). Furthermore, both federal and cantonal contributions are used to subsidize health insurance premiums for households with modest incomes.

The KVG forced a reduction in cantonal autonomy on decisions regarding public spending, leading to several important changes in the distribution of tasks between the Confederation and cantons.Footnote 38 In 2013, the federal health minister issued, for the first time in Switzerland’s history, a strategic plan (called Gesundheit2020) that sets priorities for health policy action in four areas and defines 36 measures to be implemented in the coming 8 years.Footnote 39 The reactions of stakeholders and cantonal authorities to this initiative were mixed. Nevertheless, this initiative of the federal government demonstrates that even federal states with a longstanding tradition of decentralization need, at a certain point in their history, to overcome fragmentation and weak health policy leadership, and start to increasingly rely on central power interventions (Reference Crivelli, Salari, Levaggi and MontefioriCrivelli & Salari, 2014b). The essence of the problem lies at a different level: such a transfer of new tasks to the Confederation cannot take place without an amendment of the Federal Constitution (Schaffhauser, Locher & Poledna, Reference Schaffhauser, Locher and Poledna2006) and must be accompanied by a corresponding adjustment of the public spending share borne by the federal government (Reference 488Crivelli and FilippiniCrivelli & Filippini, 2003). The absence of these adjustments would result in a violation of the principle of “who decides, pays”, as the bulk of public spending on health is still financed by the cantons, even though the Confederation plays an increasingly important role in health policy decisions. Accordingly, it is not surprising that in the last 20 years cantons have been unwilling to accept radical reforms of the system aimed at transferring additional responsibilities and decision-making power to the central government and to health insurers without an equivalent transfer of financial responsibilities. Several times in the last two decades cantons have been the main opponents of the federal government’s roadmap of reform, and hence the search for consensus on fundamental changes continues to be slow and complex (Reference Bolgiani, Crivelli and DomenighettiBolgiani, Crivelli & Domenighetti, 2006).

Assessing the performance of health insurance

The contribution of statutory health insurance to health care finance

Switzerland is distinct, among high-income countries, in its highly regressive health care financing system (Reference Wagstaff and van DoorslaerWagstaff & van Doorslaer, 1992;

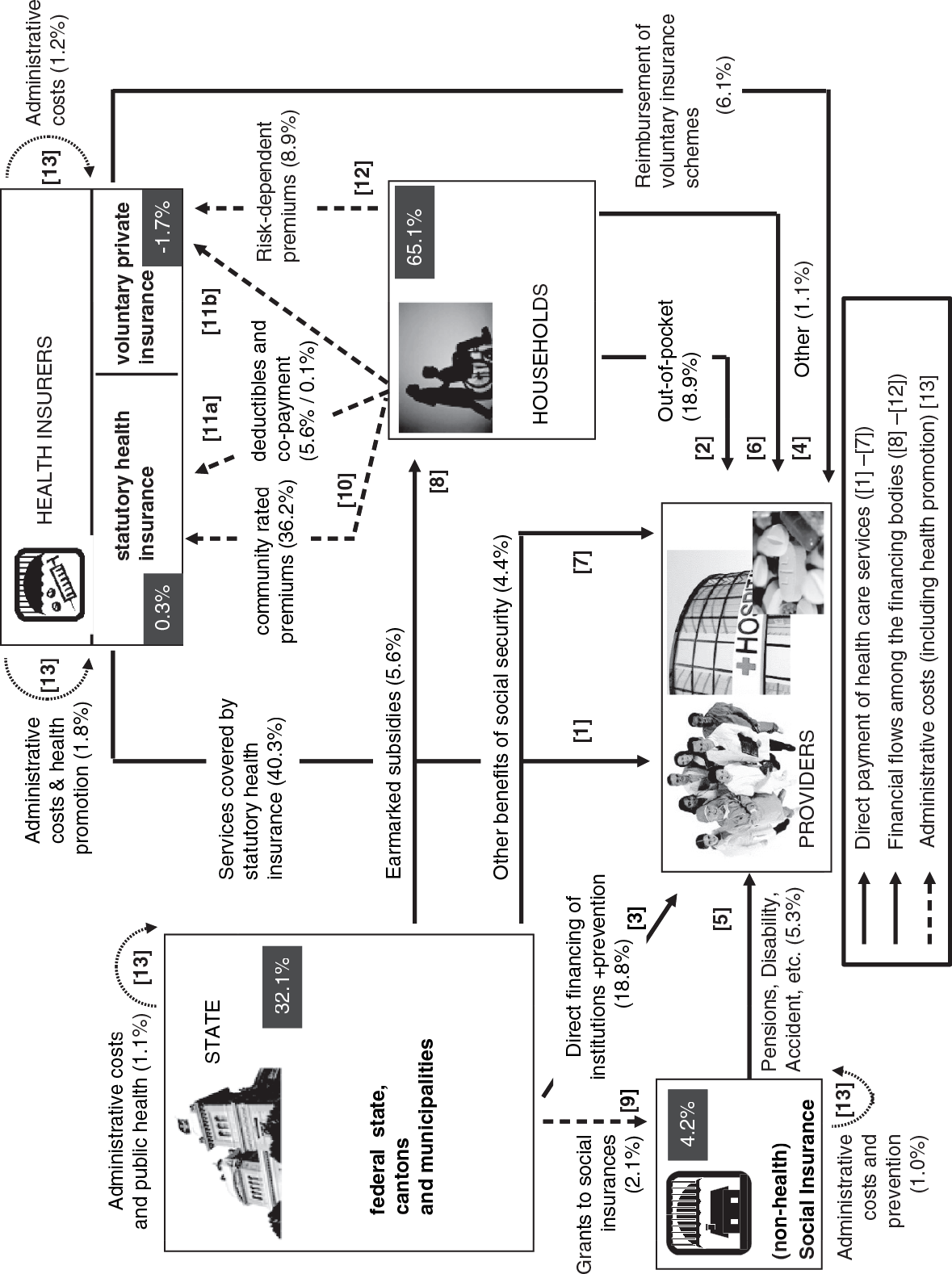

Note: In 2014 total health care financing amounted to Sw.fr.71.3 billion.

Wagstaff et al., Reference Wagstaff1999; Reference BilgerBilger, 2008; Iten et al., Reference Iten2009; Ecoplan, 2013; Reference Crivelli and SalariCrivelli & Salari, 2014a). This is due to two factors: first, compulsory health insurance premiums are established independently of citizens’ ability to pay; and, second, citizens are called on to pay a considerable share of the health care costs (approximately 31%) out of pocket or through voluntary insurance. This share is high compared with other OECD countries, illustrating how a combination of fiscal federalism, direct democracyFootnote 40 and a private insurance system can lead to low achievement with respect to the objectives of redistribution and vertical equity (Reference Banting and CorbettBanting & Corbett, 2002).

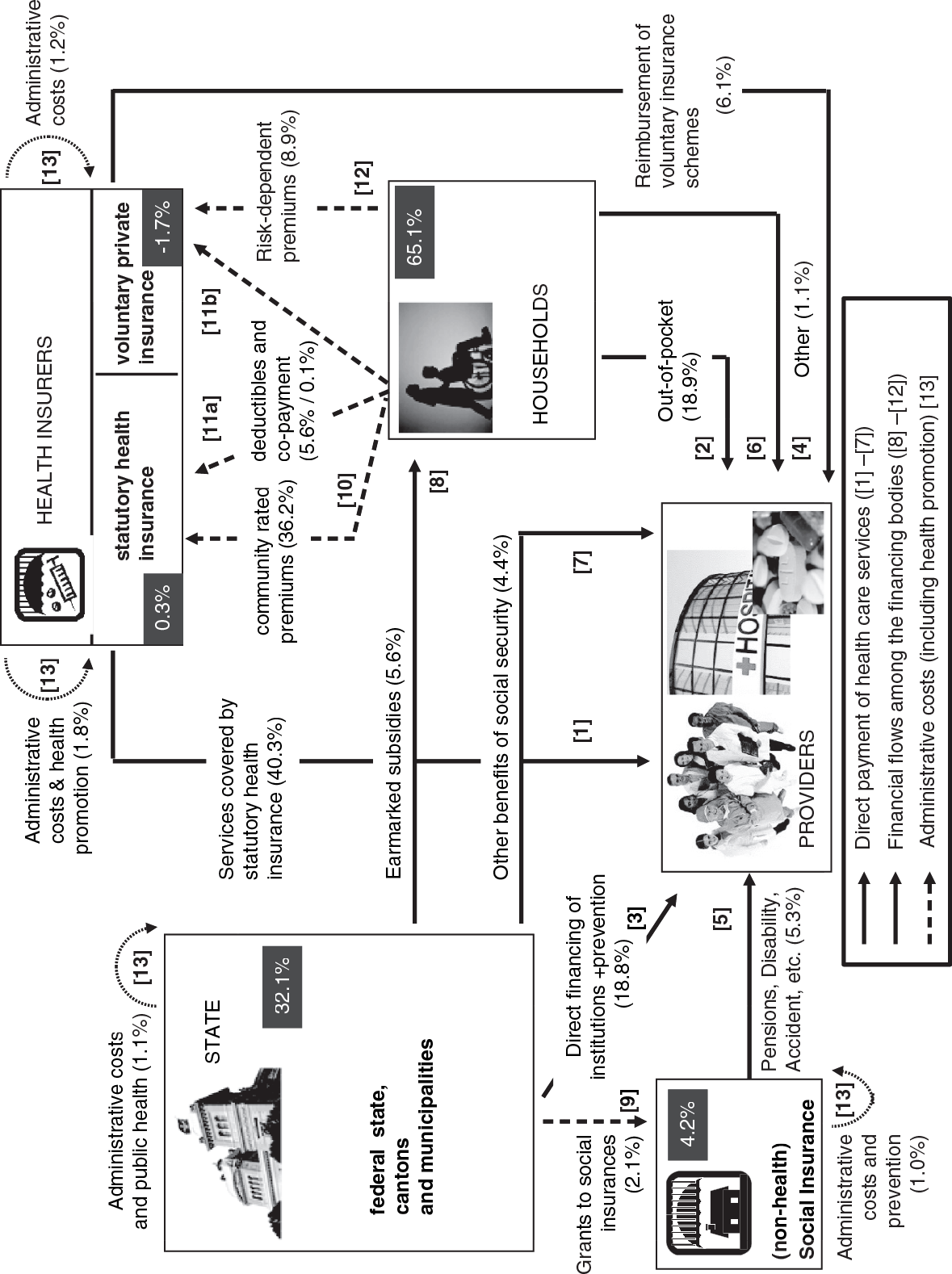

The Swiss health care system is also characterized by a multiplicity of actors who finance health services: the three levels of government (federal, cantonal and municipal); approximately 60 sickness funds; private insurers and other social insurance bodies; and, finally, every Swiss household. Direct payments for health services are indicated in Fig. 14.1 by the solid arrows with the numbers [1] to [7]; in addition to which several financial transfers take place between the financing bodies, shown by the dashed arrows from [8] to [12]. Finally, the dotted lines [13] indicate administrative costs (which include spending on prevention and health promotion).

Total spending on health care is therefore distributed in the following manner:

The share borne by the state (Confederation, cantons and municipalities) is about 32%, financed by Swiss residents in a generally progressive way by means of taxation. The bulk of the state share comes from cantons and is used to finance hospitals. A significant but smaller portion of this share is used to subsidize premiums (56% from federal government, 44% from the cantons in 2014).

The net share borne by non-health social insurance funds (accident, invalidity and pensions) is about 4.2%.Footnote 41 This share comes from contributions proportional to income and is jointly financed by employers and employees.

The share of expenditure borne by households accounts for 65.1%.Footnote 42 This spending, whose main feature is the absence of any relation to citizens’ ability to pay, comes in four distinct forms, with different redistributive effects:

- net community-rated premiums for mandatory health insurance,Footnote 43 which amount to 30.6% of total spending (36.2% less 5.6% of premium subsidies) and reflect solidarity between the healthy and the sick, and between generations

- voluntary private insurance premiums, which are risk-rated but still defined ex ante and therefore represent a way of financing health care based on mutuality (8.9% of total spending)

- contributions depending ex post on each individual’s health care consumption, net of the public contributions in various regimens of social protection such as social aid, allowance, etc. (24.5%); this category includes direct out-of-pocket payments as well as coinsurance and deductibles for services covered by mandatory health insurance

- private donations to non-profit institutions represent 1.1% of health spending.

In a nutshell, approximately one third of Swiss health care financing is linked to citizens’ income and ability to pay (federal, cantonal and municipal tax financing, with the exception of value added tax, non-health social insurance contributions). The second third reflects each citizen’s risk profile and individual health care consumption (voluntary private insurance and out-of-pocket payments). The last third allows for a high degree of solidarity between the sick and the healthy (the community-rated premiums). As a result, the middle class bear a disproportionately heavy share of the financial burden in the interests of solidarity.

Unsustainable health insurance premiums for the middle class

Overall, Swiss health care is characterized by good equity of accessFootnote 44 and substantial and widespread public approval – in spite of high levels of out-of-pocket expenditure – by virtue of the high degree of responsiveness to patients’ desires, the large benefit package and ample freedom of choice. However, beyond these positive performance scores, emphasized in several international analyses (WHO, 2000; OECD, 2006; van Doorslaer, Kollman & Puffer, 2002; Reference van Doorslaer, Masseria and Koolmanvan Doorslaer, Masseria & Koolman, 2006; Schoen et al., Reference Schoen2010), there is little pressure to enhance efficiency in the Swiss health care system.

Retrospective (fee-for-service) provider payment for outpatient care, collective negotiations at the association level and ineffective risk adjustment by health insurers are not the best way to prevent monopoly rents in income distribution (Reference ZweifelZweifel, 2004). The explosion of health care costs experienced in Switzerland is reflected in constant increases in health insurance premiums over the last 10 years. Between 1996 and 2016 the average national annual premium for adults has grown by 147% from Sw.fr.2077 (about €1900) to Sw.fr.5138 (about €4700).Footnote 45 The increase may have been more pronounced without the concurrent transfer of risk from the health insurers to the insured; from 1996 to 2005 the minimum deductible doubled from Sw.fr.150 to Sw.fr.300. The ongoing reduction in statutory reserve standards since 1998 has also contributed to containing the size of actual premium inflation.Footnote 46

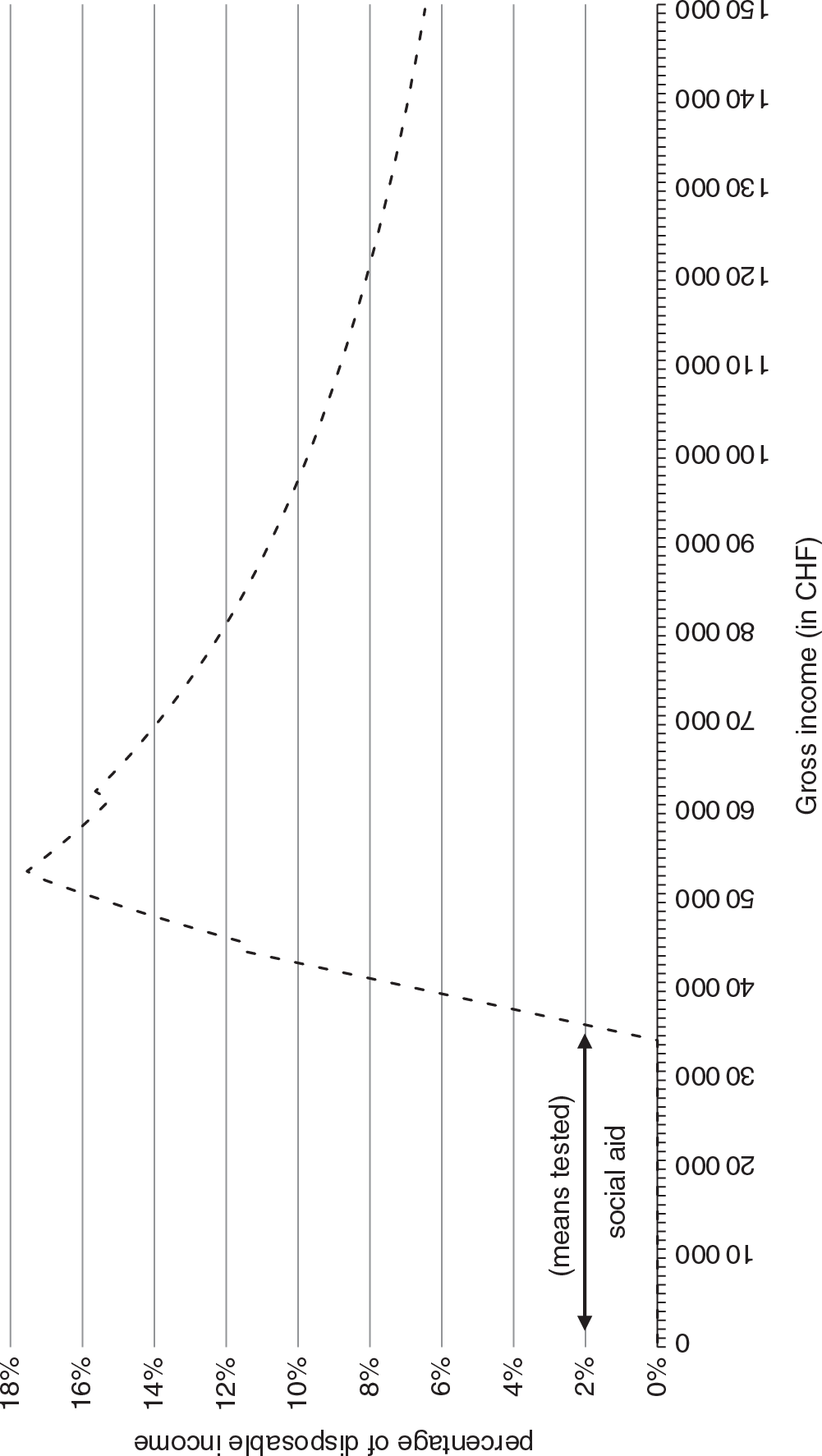

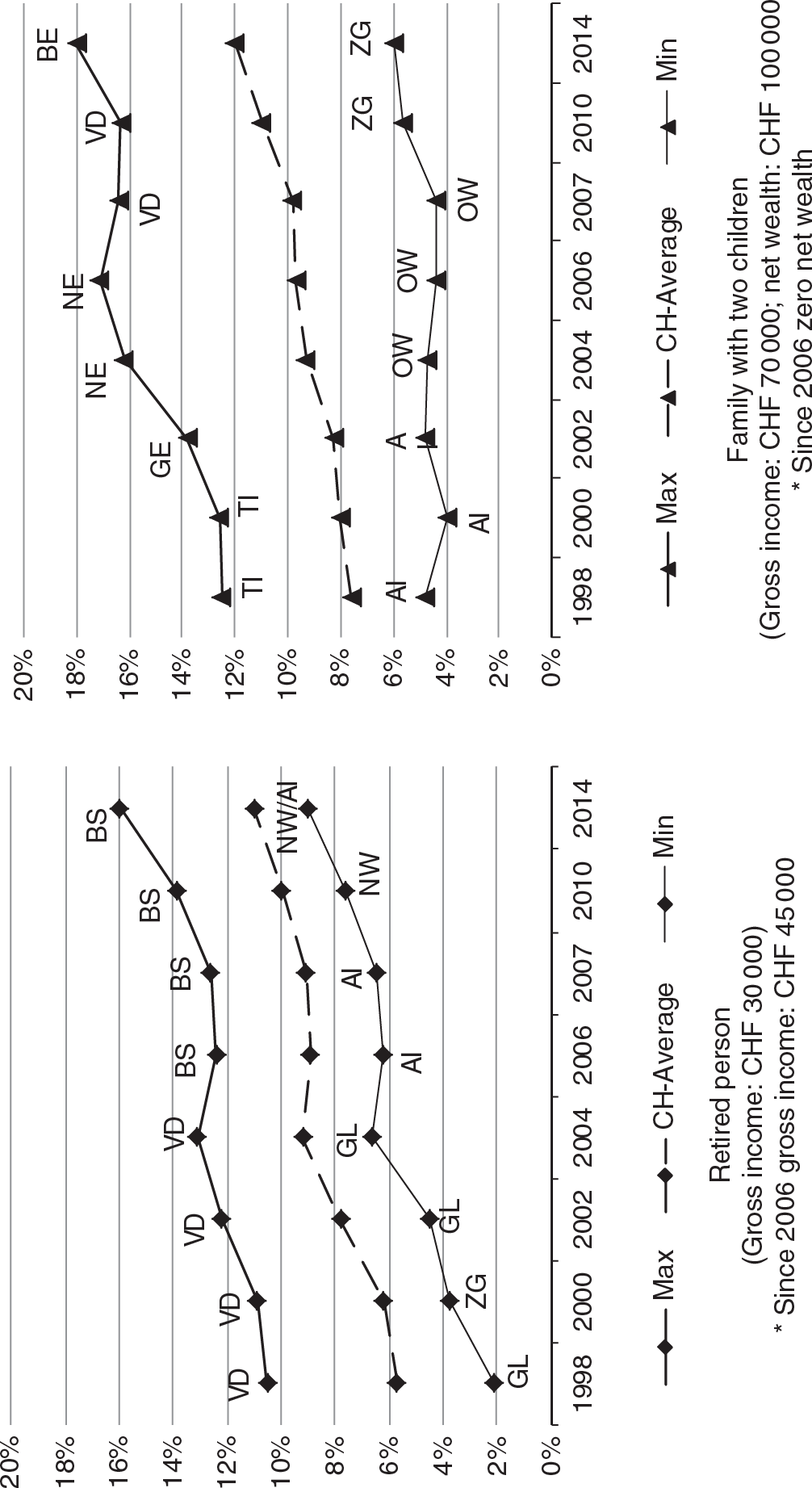

As a result of cost and premium inflation, combined with increased cost shifting to consumers, the economic burden of health insurance has become unsustainable for a large number of citizens (Reference KilchenmannKilchenmann, 2014; Reference Frey and NeumannFrey & Neumann, 2015).Footnote 47 Although premium subsidies for households with modest incomes (provided jointly by the Confederation and cantons) have increased by 64% between 1998 and 2014, the impact of the net premium on disposable income for many households has also increased greatly, in many cases exceeding the 8% threshold to which the Federal Council committed itself when presenting the KVG draft bill in 1991 (Kägi et al., Reference Kägi2012; Reference Frey and NeumannFrey & Neumann, 2015). Fig. 14.2(a) shows the evolution of net premium incidence (as a percentage of disposable income) for two typical households (a family of four and a retired single person) from 1998 to 2014. The graph highlights the Swiss average as well as the situation in the cantons with the lowest and highest incidence. Fig. 14.2(a) illustrates two facts. First, a general growth in incidence over time; the almost flat development for the retired person between 2004 and 2007 is due to a change in the economic situation of the underlying reference household,Footnote 48 which masks the real development of the situation. Second, the strong horizontal inequity of financing across the cantons; the distance between the lowest and the highest canton remains constant over time for the retired person, but it increases for the family. This variation can be explained by the different levels of cantonal spending on health as well as the cantons’ diverging strategies in earmarking subsidies for low-income households; some cantons distribute small allowances to a large share of the population, whereas others prefer to target smaller groups of citizens and give them larger amounts of money (Reference Preuck and BandiPreuck & Bandi, 2008).Footnote 49 Moreover, the large reform of the fiscal equalization scheme in 2008 provided cantons with more leeway to react to budgetary pressures by cutting their spending for earmarked premium subsidies (Reference Gerritzen, Martinez and RamsdenGerritzen, Martinez & Ramsden, 2016). As a result, heterogeneity of incidence across cantons could even further increase in the coming years.

As would be expected from the system’s design, those bearing the greatest share of the financing burden belong to the middle class, the group that no longer benefits from premium subsidies or receives only a marginal contribution from the state. Fig. 14.2(b) illustrates a typical ratio of net insurance premium incidence on household disposable income in Switzerland, computed for a couple living in Ticino canton in 2011.Footnote 50 The highest level of incidence, in this particular case 17.5% of disposable income, corresponds to the middle class (an income of Sw.fr.53 000 for a couple). Moreover, for many insured people whose income is slightly above the poverty line, small increases in income are to a large extent eroded by the immediate stopping of means-tested social aid and by the quick reduction in the subsidies provided, resulting in significant threshold effects (the almost vertical line between Sw.fr.44 000 and Sw.fr.53 000 in Fig. 14.2b).

Figure 14.2(a) Change in net premiums as a percentage of disposable income (Swiss average and cantons with lowest and highest incidence), 1998–2014

Figure 14.2(b) Shape of the 2011 net insurance premium incidence for a couple living in Ticino

Victor Fuchs foresaw this problem in his presidential address to the American Economics Association in 1996, although Fuchs himself may have been unaware that only a few days earlier Switzerland had adopted this system. He noted that:

“There are only two ways to achieve systematic universal coverage: a broad-based general tax with implicit subsidies for the poor and the sick, or a system of mandates with explicit subsidies based on income. I prefer the former because the latter are extremely expensive to administer and seriously distort incentives; they result in the near-poor facing marginal tax rates that would be regarded as confiscatory if levied on the affluent.” (Reference 490FuchsFuchs, 1996: p.17).

Evolution of health insurance market structure

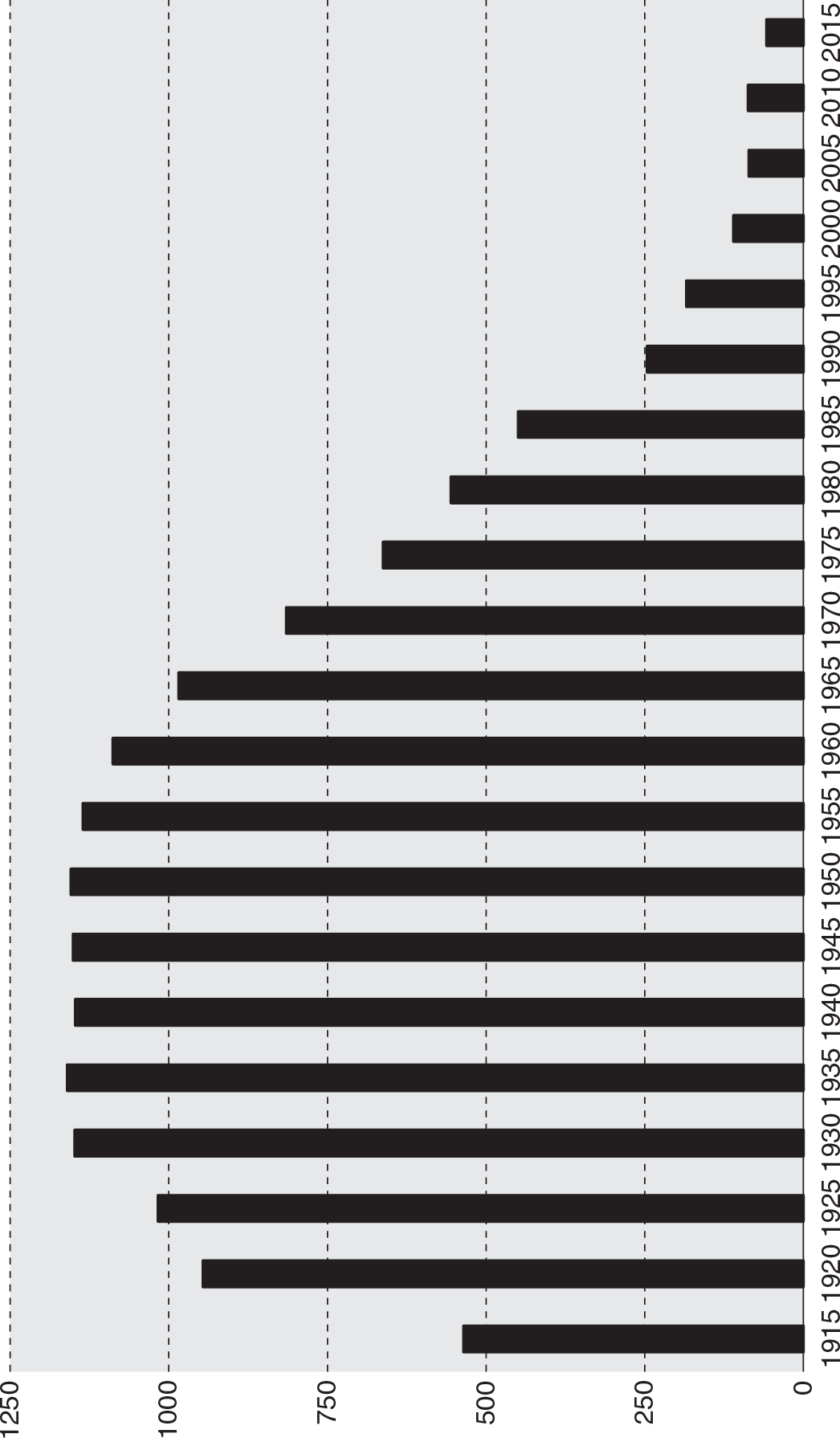

Throughout the first half of the 20th century (Fig. 14.3a) the number of sickness funds doubled from about 500 in 1915 to over 1100 in 1950. This was followed by a phase of progressive concentration in the market, largely through mergers and acquisitions (Reference Frei, Kocher and OggierFrei, 2007),Footnote 51 marked by a dramatic fall in the number of sickness funds (from 984 in 1965 to 58 in 2015) and an increasing degree of professionalism and range of operation.Footnote 52 Nevertheless, the administrative costs of mandatory health insurance remain moderate (compared with United States standards), amounting to 4.9% of total operating costs in 2014.

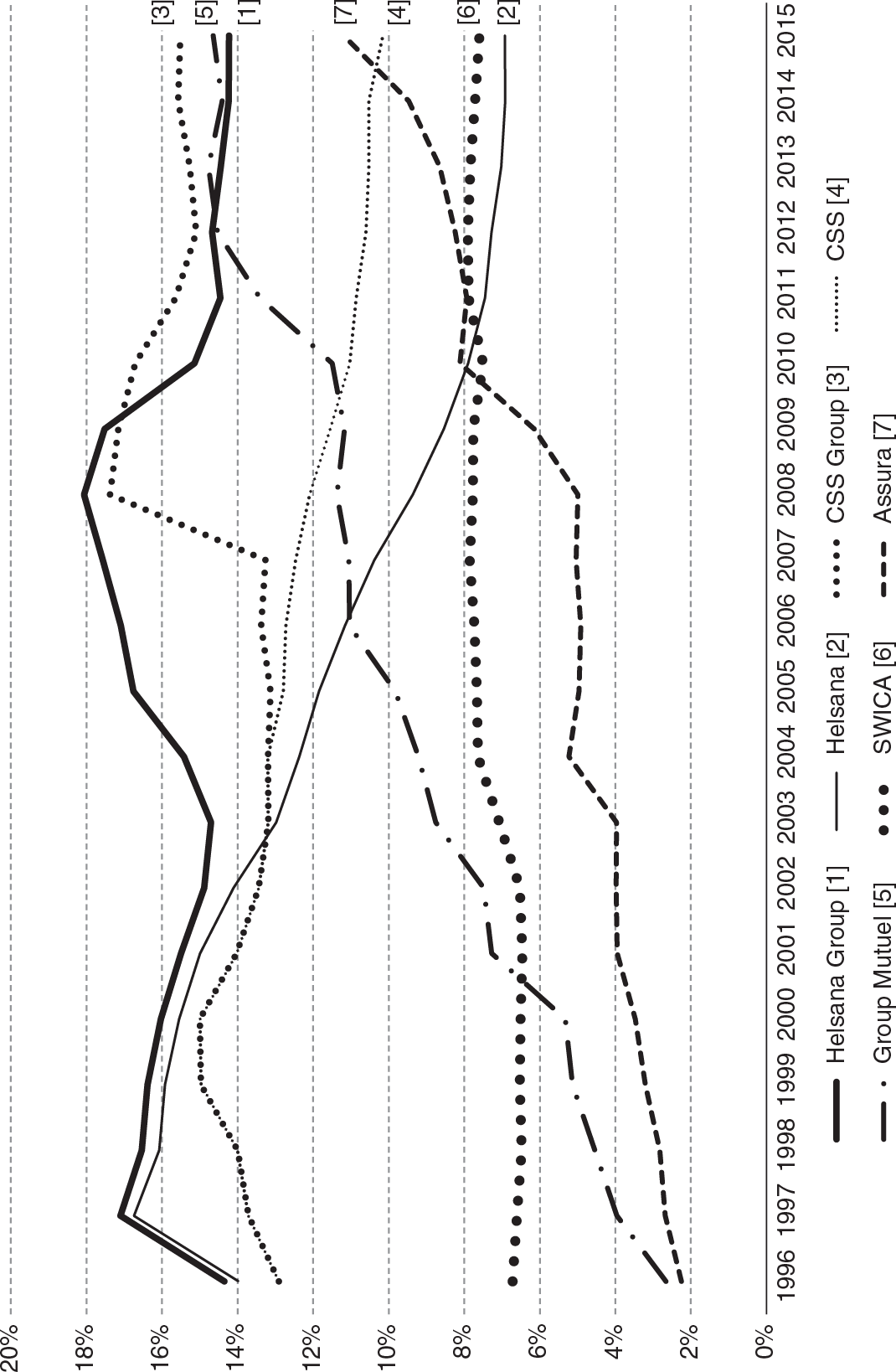

Over time the change in numbers of sickness funds has been accompanied by other profound changes. Once-local mutual support groups were transformed into modern insurance companies – global playersFootnote 53 – losing their local vocation and their link to particular population groups such as employees in a given firm, members of a trade union, special professional categories and inhabitants of a given area. The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) computed for each individual health insurer shows a weak reduction in market concentration (the HHI declined from about 0.0757 in 1996 to 0.0545 in 2015). In fact, the largest sickness funds (Helvetia/Helsana, CSS and Visana) have increasingly lost clients, to the benefit of average-sized companies investing in risk selection, in particular Assura and sickness funds belonging to the insurance holding Group Mutuel, which in 2003/2004 included 17 different companies and was very successful at segmenting its clientele into risk groups. Starting from 2003 even the largest sickness funds have tried to imitate this strategy, transforming themselves into holding companies and grouping sickness funds, which maintain their own company names (as well as their independent legal status) but are managed according to a common strategic orientation.Footnote 54 By acquiring small funds and creating new companies CSS and Helsana have managed to stop the loss of affiliated members observed since 1997 and reverse the trend (see Fig. 14.3b). Another successful sickness fund, that managed to maintain its market share without creating a holding structure, was Swica. The competitive advantage of Swica has been its strong investment from the very beginning in the development of HMOs. Hence, when considering the market share of the holding companies that exist today, instead of individual sickness funds, we observe a significant increase in market concentration between 1996 and 2015 (the HHI increases from 0.0763 to 0.1008). The regional markets are much more concentrated. In five cantons (Geneva, Jura, Obwalden, Basel City and Graubünden) the 2006 HHI was higher than 0.1800 (which corresponds to the usual threshold indicating a highly concentrated market) (Reference Hefti and FreyHefti & Frey, 2008: p.46). The improvement of the risk adjustment formula, which was implemented in 2012 with the aim of making cream-skimming strategies less attractive, had the expected positive effect. Already in 2011, Group Mutuel decided to slim down its structure by reducing the number of companies from 15 to four, significantly enhancing market transparency.

Figure 14.3(a) Number of sickness funds in Switzerland, 1915–2015

Figure 14.3(b) Market share of the largest insurers and holdings in Switzerland, 1996–2015

Risk pooling and switching behaviour

Reference HirschmanHirschman (1970) argues that in order to judge the functioning of the exit-reaction mechanism one must evaluate switching behaviour in relation to differences in price and quality. As explained previously, collective contracting for the compulsory benefit package removes differences in the quality of covered health services. Disparities exist, however, in the quality of administrative services and the price of community-rated premiums. The latter reflects the average profile of an insurer’s risks (and is therefore susceptible to cream-skimming strategies) and the insurer’s ability to control consumers’ invoices, limiting the consequences of moral hazard. Although there are tangible differences between insurers in terms of administrative service quality,Footnote 55 these are difficult to quantify. It is even more difficult to determine elasticity of demand with respect to administrative quality. What can be hypothesized is that these differences are more evident to those with frequent relations with their insurers – for example, people with chronic conditions who often require information or regularly submit invoices and can better assess speed of reimbursement.Footnote 56

Despite large differences in premiums (Leu at al., Reference Leu2007) and low switching costs, for many years only a small fraction of policy-holders (between 2% and 3%) switched insurer.Footnote 57 However, the situation has changed significantly in recent years, due to continuous premium growth, which makes health insurance more and more unaffordable for the middle class (households not eligible for subsidies). The percentage of people switching to a cheaper health insurer between 2009 and 2010 exceeded 15% and has since then remained consistently above 6.5%. According to Reference DiserensDiserens (2002), quoted in Reference 487BeckBeck (2004a), price elasticity for mandatory health insurance (estimated from aggregate market-share data) is approximately –0.5 in Switzerland, higher than is seen in the Netherlands, but much lower than in Germany (Reference Schut, Gress and WasemSchut, Gress & Wasem, 2003). However, using individual data Reference Beck and GelpeBeck & Gelpe (2002) obtained much higher estimates (average value –1.09) and elasticity estimates calculated by Reference RütschiRütschi (2006) are even higher. In other words,

Swiss consumers seem to be less responsive to changes in the price of premiums than German consumers, but recent data highlights a new trend leading to the expectation of higher switching rates in the future. Empirical evidence shows that those willing to change sickness fund frequently come under the category of good risks: young, healthy and higher educated enrollees (see Reference Strombom, Buchmueller and FeldsteinStrombom, Buchmueller & Feldstein, 2002; Beck et al., Reference Beck2003).

What emerges from this picture is that most insured people do not exit but stay with their sickness fund, even if their premiums are 40% higher than the least expensive on offer. There are many ways of interpreting this limited degree of switching. The insured may regard the transaction costs of switching to be very high, particularly if they are older or sicker and have voluntary insurance coverage.Footnote 58 Alternatively, low mobility could be explained by asymmetric information (people underestimate the potential gain of switching health insurer), the limited rationality of individuals and their status quo bias. Moreover, even though the premium is higher, many insured may be unwilling to switch out of loyalty to their own sickness fund. Finally, there are risk-averse individuals who prefer to remain faithful to a company whose faults and merits they know rather than face the uncertainty of a new insurer. Or perhaps, more simply, they hold on to the hope that in future their current insurer will offer the compulsory benefit package cover at a more competitive rate.

According to Reference Laske-AldershofLaske-Aldershof et al. (2004), the reasons for increased premium variation in Switzerland include a risk-adjustment formula with poor predictive power before 2011,Footnote 59 the low-risk profile of switchers, the success of risk-selection strategies adopted by the most aggressive sickness funds and the relative share of people choosing higher deductible levels in the population enrolled in the different sickness funds. As a result, risk-pooling has become less efficient over time. As shown by Reference Frank and LamiraudFrank & Lamiraud (2008), the broadening choice set facing the insured in most cantons (see footnote 255) brought about, ceteris paribus, a significant decrease in the frequency of switching.Footnote 60 All these data suggest that further liberalization of the health insurance market, if accompanied by an increase in insurers, could have negative outcomes such as lower efficacy in the exit decisions of the insured and, indirectly, increased risk of transferring so-called rent to insurers.

Risk selection versus moral hazard control

For people who do not switch insurer, the opportunity for partial exit remains an option through the choice of a higher optional deductible or a managed care contract. The number of adult insurees opting for an optional deductible rose between 1996 and 2014 from 32% to 56%.Footnote 61 The diffusion of higher deductibles may have both a positive and a negative impact. The positive consequence is an increase in individual responsibility and a reduction in the use of unnecessary health services. Some authors concur that high deductibles have significantly reduced moral hazard in Switzerland (see Reference WerblowWerblow, 2002; Reference Felder and WerblowFelder & Werblow, 2003; Reference Werblow and FelderWerblow & Felder, 2003), whereas other studies estimate the positive impact of high deductibles to be modest (Reference SchellhornSchellhorn, 2002). The negative effect is the process of self-selection that determines deductible choice. Reference Geoffard, Gardiol, Grandchamp and GollierGeoffard, Gardiol & Grandchamp (2006) have observed, from a representative sample of clients, that the mortality rate of the insured selecting the minimum deductible is 200% greater than that of those selecting a medium deductible. On the other hand, the insured choosing a high deductible had a 30% lower mortality rate than those choosing a medium deductible when the data were standardized by age and sex.

The exit of Swiss insurees towards managed care contracts has been less common than the choice of optional deductibles up to 2012. After an initial burst of enthusiasm,Footnote 62 a period of stagnation ensued. A possible explanation for the limited diffusion of managed care, which many experts believe is not yet capable of introducing competitive pressure on health care providers, is that discounts for these particular insurance forms are regulated to values far below the actual cost savings achieved and lower than the compensation generally necessary to overcome consumer resistance to managed care restrictions (Reference Zweifel, Telser and VaterlausZweifel, Telser & Vaterlaus, 2006). Since 2004 another upsurge in the popularity of managed care contracts has been observed. The 2008 market share of these alternative insurance forms was 24.3% of the adult population and rose in the last 6 years up to 62% in 2014. The new possibility to combine a managed care contract with an optional deductible (and to benefit from both discounts) certainly helped to increase the popularity of these contracts. Instead of switching health insurer, a growing number of policy-holders are opting for these alternative models in an attempt to avoid raising premiums in the classic form of cover. Reference ZweifelLehmann & Zweifel (2004) have attempted to evaluate risk-adjusted expenditure differentials for clients who are members of the three most widespread forms of managed care (HMO, PPO, IPA) compared with the expenditure of clients selecting the traditional contract form. Overall, observed costs are 62% below average in HMO contracts, 39% below with PPO and 34% below with IPA. Yet the maximum premium discount allowed by law is 20%. After controlling for the effects of risk selection, the true savings account for two thirds of the cost reductions recorded by HMOs, half of those by PPOs and one third of savings made by IPAs. A more recent study (see Reference Reich, Rapold and Flatscher-ThöniReich, Rapold & Flatscher-Thöni, 2012) estimates efficiency gains of 21.2% for HMO, of 15.5% for IPA and of 3.7% for the so-called Telmed contracts,Footnote 63 whereas the risk selection effects account for 8.5%, 5.6% and 22.5%, respectively. Given that only a part of the savings made can be retransferred to the client in the form of a premium discount, particularly in HMOs, it is quite probable that the people who have opted for these systems did so due to their inability to pay the ordinary premium and are therefore mainly people in good health but with a relatively low income.

The central role of direct democracy in past and future health insurance reforms

Direct democracy and federalism are at the origins of the very slow pace of radical reforms in the Swiss health insurance system. Referenda and popular initiatives allow Swiss citizens to intervene directly in the decision-making process, approving or rejecting each reform through a popular ballot. Because unbalanced and radical revisions have a high likelihood of rejection in popular ballots, bills are generally amended early on in a pre-parliamentary phase involving negotiation ex ante with opponents of reforms originating in government or parliament and incorporating the demands of the most powerful lobbies (Reference ChengCheng, 2010: p.1450).Footnote 64 In addition, federalism encourages the proliferation of organizational models and spending levels that vary across cantons (Reference Crivelli, Salari, Levaggi and MontefioriCrivelli & Salari, 2014b). Although these variations should reflect citizens’ preferences, they create inevitable tensions in maintaining a universal system. Between 1974 and 2014 the Swiss population was called to the ballot box no less than 14 timesFootnote 65 to deliberate on reforms in the health insurance sector (two urgent federal decrees, three reforms of the federal law proposed by parliament and put to referendum, seven popular initiatives and four counter-proposals). With the exception of the referendum on the KVG in 1994, of two referendums on counter-proposals and of those regarding the two urgent federal decrees accepted by the people, the remaining 11 popular ballots failed (see Table 14.1).

A recurring topic during these years of health insurance reform is the enhancement of equity in financing through more extensive use of general taxationFootnote 66 or by changing from community-rated to income-dependent health insurance premiums.Footnote 67 What can be considered a potentially radical change to the system was rejected five times with a sweeping majority of between 60% and 76% of the population, but each time with a participation rate of less than 50% of citizens (ranging from 39.7% in 1974 to 49.7% in 2003). The 2003 popular ballot is particularly illustrative. Two surveys conducted during the second half of 2002 showed a substantial majority of citizens (63%) declaring themselves willing to pay income-related health insurance premiums (Crivelli, Domenighetti & Filippini, 2007). However, 6 months later, in May 2003, 73% of the electorate rejected the popular initiative “Health at Accessible Prices”, which proposed a mixed financing system including income-related premiums alongside an increase in value added tax. Undoubtedly, there were substantial differences between the (generic) question asked of the sample interviewed in the 2002 surveys and the specific model proposed by the promoters of the initiative. The media campaign launched at the end of 2002 (see, for example, Credit Suisse, 2003) also persuaded many citizens that it was in their interest to maintain the status quo. There were similar results in the popular ballot held in March 2007 concerning the creation of a single sickness fund with income-related premiums. Two months after the clear No to the initiative (72% of the votes), a survey undertaken for the health insurers showed that 60% of the population favoured the change to income-related premiums. Finally, the impact of the ballot campaign in shifting opinions towards the status quo has been assessed also in the latest ballot of September 2014 (initiative “for a public health insurer”). In a poll carried out in June 2013, 65% of respondents declared themselves in favour of a single, public health insurer. The opponents’ campaign kicked off in 2013 and strengthened in June 2014. As a result, the percentage of those supporting the initiative fell constantly over time. This decline in supporters, observed in the polls, shows again how a majority in favour of the initiative (until June 2014) can be gradually transformed into a majority against it (Reference CrivelliDe Pietro & Crivelli, 2015), with 61.8% of voting people finally rejecting the initiative.

Yet there is another explanation which invokes Hirschman’s theory: the opportunity of exit (towards sickness funds with lower premiums, higher deductibles or managed care contracts) takes strength away from voice.Footnote 68 Many people (especially good risks and those with modest income) who, in the absence of this exit opportunity, would vote in favour of radical reforms of the system, either do not participate in popular ballots or vote in favour of the status quo. When it is a question of voting on reforms to the health system, natural tensions occur within each individual, as interests as patient and tax payerFootnote 69 diverge from preferences about being insured.Footnote 70

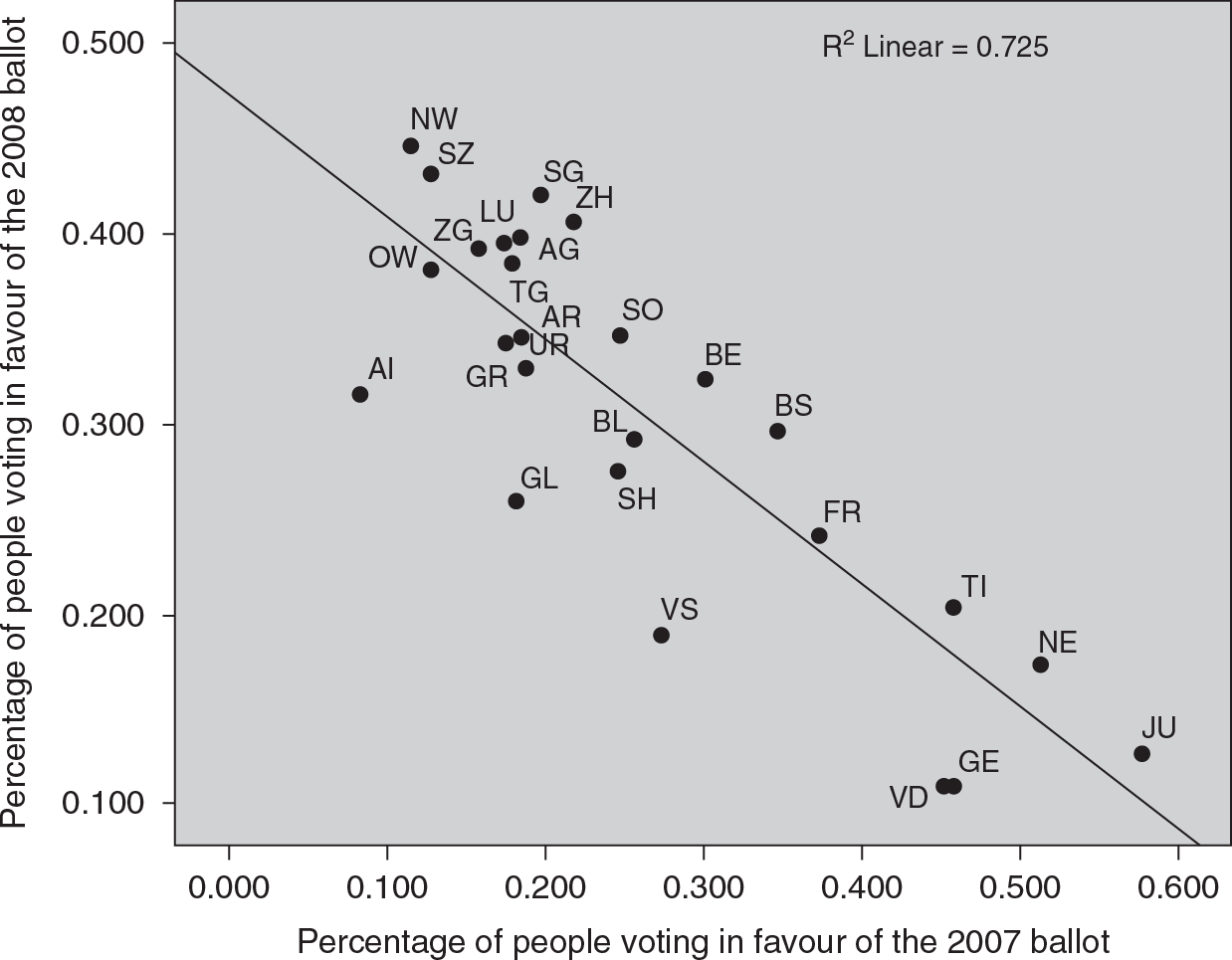

Following the rejection of the single sickness fund proposal in March 2007, which would have strengthened the role of voiceFootnote 71 in the governance of health insurance and suppressed the possibility of switching insurer, in June 2008 the Swiss people were called on again to make an important decision, which could have caused the fragile compromise between market and state regulation in the present legislation to break down. Right-wing groups blame the state-constrained Swiss health care system for preventing competition between sickness funds, and the existence of (in their view) an overly comprehensive benefit package for encouraging over-consumption and moral hazard on the part of many patients. The Swiss People’s Party therefore launched an initiative based on two fundamental pillars: the transfer of part of the health services presently included in the compulsory benefit package to voluntary private insuranceFootnote 72 and the strengthening of competition and market logic (by abolishing compulsory contracting, accepting liberalization of provider fees and granting the insurers the status of single purchasers of health services).Footnote 73 In particular, market mechanisms would be reinforced in the relations between insurers and the insured, and in the relations between insurers and providers.

Parliament drew up a counter-project to this initiative (called “For a More Effective and Better Quality Health Care System Thanks to Greater Competition”), with the aim of anchoring the most important principles of the initiative within the Federal Constitution and increasing the probability of acceptance.Footnote 74 The most significant amendment to the initiative’s text was to remove the shrinking of the compulsory benefit package from the proposal. In January 2008, the Swiss People’s Party withdrew their initiative in support of parliament’s counter-project. Two months previously, surveys undertaken by Swiss Television had outlined a fairly clear picture of the ballot’s potential outcome: 60% claimed to be in favour of the counter-project, 20% were against it and 20% undecided. In the following 2 months an extremely fierce campaign (cantonal authorities were strongly opposed to the counter-project, as were doctors’ and patients’ associations and the centre-left parties) succeeded in bringing about a sensational reversal in the outcome of the vote; in fact on 1 June 2008, 69.5% of voters rejected the counter-project, opting once again for the status quo.

As shown in Fig. 14.4, the results of these two consecutive popular ballots bear witness to a clear negative correlation between the preferences of the population of the 26 cantons. Both reform projects were far from obtaining the required dual majority (of the people and of the cantons), but they had the merit of pushing the debate on reforms towards a well-defined strategic choice. This in turn would have the advantage of clarifying not only the role given to market mechanisms and state regulation, but also whose stake (citizens, patients or insured people) would ensure governance of the Swiss health system. It is not easy to see how a compromise can be found between two antithetical reform strategies in a ballot system that requires a dual majority.

Figure 14.4 Correlation of cantonal results in the 2007 and 2008 popular ballots in Switzerland

What does seem certain is a slow but inexorable cultural change among citizens and the insured. The obligation to insure themselves combined with (radical and partial) exit options has modified citizens’ perceptions of what is acquired by paying the health insurance premium. As Ostrom (Reference Ostrom, Gintis, Boyd and Fehr2005) well emphasizes, some policies can crowd out reciprocity and collective action. The irrevocability of regressive premium payments has prompted many citizens to view health insurance as a socially unjust tax, and there is an alarming increase in the number of citizens who no longer pay their compulsory premiums regularly (with a prevalence that in some cantons reaches 5% – see Reference EgloffEgloff, 2016). At the same time, the possibility of frequently switching insurer makes the typical social insurance values of solidarity and mutuality less obvious. In recent years, a growing number of citizens seem driven to consider cover against the risk of ill health as a commodity; a premium is paid in exchange for health services (and not for the right to transfer financial risk to third parties in case illness strikes). The inflationary incentives inherent in the Swiss fee-for-service payment of ambulatory care (provided both in hospitals and private medical practices) with only weak referral systems (Schwenkglenks et al., Reference Schwenkglenks2006) encourage the use of inappropriate diagnostic and therapeutic services by people who are in fact in good health. Hence, the perception of a welfare state in which “abuses are the order of the day” infects the population and raises questions about the legitimacy of proposals intended to maintain and strengthen solidarity among the healthy and sick, young and old, rich and poor,Footnote 76 giving rise to the danger of undermining the foundation upon which the Swiss system of universal health insurance is based