In December 1894, during the middle of the First Sino-Japanese War, Tokutomi Sōhō published a collection of his political essays under the title On the Expansion of the Great Japan (Dai Nihon Bōchō Ron), predicting that Japan’s defeat of the Qing would become a starting point of the empire’s destined global expansion in the decades to come.Footnote 1 The Japanese population, he asserted, had grown rapidly and soon would exceed the amount that its existing territory could accommodate. Meanwhile, since population size was a crucial indicator of national strength, as demonstrated by the success of the British global expansion in the recent past, Japan had to maintain its overall population growth. Like “surging water would flow over the riverbank,” he concluded, Japan had to take on the mission of expansion by exporting its subjects overseas.Footnote 2

Tokutomi urged the entire nation to unite and fight to hand the Qing Empire a total defeat rather than accepting a quick armistice that would grant Japan the control of Korean politics or an attractive amount of reparation. The Qing Empire was not simply a political threat to Japan’s territorial ambitions in Asia, but as the Japanese were destined to expand overseas and “establish new homes around the world,” the Chinese presented a key barrier to this global expansion because they were competing with Japanese emigrants in different parts of the world such as Hawaiʻi, San Francisco, Australia, and Vladivostok.Footnote 3 Tokutomi wanted his readers to understand the war as not only a clash of two geopolitical powers but also part of the inevitable rivalry of global expansion between the Chinese and the Japanese.Footnote 4 What to gain from winning the war, accordingly, was the opening of new routes and the removal of barriers to Japan’s global expansion. Defeating the Qing, Tokutomi argued, would win Japan recognition in the world as an expansionist nation and allow it to join the competition of colonial expansion on equal footing with the Western powers.Footnote 5

On the Expansion of the Great Japan demonstrates that the discourse of Malthusian expansionism, which celebrated rapid population growth on the one hand and lamented the land’s limited ability to accommodate it on the other, continued to serve as a central justification for overseas expansionism in the 1890s. However, the First Sino-Japanese War marked a turning point in the history of Japan’s migration-driven expansion. The generation of shizoku who experienced the vicissitudes of the Tokugawa-Meiji transition was disappearing from public view, and shizoku-based expansionism was phased out along with it. In its stead rose a new discourse of expansion, one that was based on the pursuit of success for the common youth. Generally called “commoners” (heimin), they were born after the Tokugawa-Meiji transition with no inherited privileges, and theirs was a generation that was fundamentally different from the generation of shizoku before them.

Compared to the shizoku, the heimin class was much larger and more diverse in social backgrounds. Its ranks included both the well-off and the poor, both urban dwellers and rural farmers. Some came from the families of either shizoku or wealthy merchants and thus enjoyed certain types of upward mobility. Others were born to impoverished homes and become members of the first generation of the working class in Japan’s fledgling capitalist economy. Despite such differences, they were collectively the first products of Japan’s modern education system. They shared the painful struggles of reconciling the ideal of egalitarianism with the reality of social inequality, the exalted principle of rugged individualism with unaffordable cost of education and fierce competition for very limited professional opportunities, the conscious pursuit of personal freedom with Japanese society’s numerous economic, cultural, and political barriers. How to make sense of these commoners as a rising sociopolitical force and what role they should play in the course of Japan’s nation/empire building became two central questions for Japan’s intellectuals, politicians, and social leaders at the time.

During the decade in between the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, the heimin class’s emergent political consciousness – and the debates about it – was accompanied by the ascent of a new expansionist discourse. The newly proposed heimin overseas migration was aimed at providing the commoners with an opportunity to simultaneously achieve personal success and serve the expanding empire. The promoters of heimin expansion came from a variety of personal backgrounds and ideological persuasions, but the vanguards of this movement were Japan’s earliest socialists who were introduced to the ideals of socialism together with Protestant Christianity. They attributed Japan’s growing social gap to class-based exploitation, but they looked for a solution to poverty not through violent revolution but through religious philanthropy and peaceful mediation between the classes. Adherents to social Darwinism and historical progress, they associated the economic and political rights of the working-class youth with the Japanese empire’s rights to colonial expansion. Among possible migration destinations, the United States was singled out as the most ideal location because it was imagined as a land of abundant job opportunities and a beacon of civilization to the rest of the world. From the Christian Socialists’ point of view, migration to the United States would allow the common Japanese youth to escape bourgeois exploitation and other forms of oppression at home; moreover, it would mold them into truly free subjects at the very center of civilization, where freedom, equality, and the value of labor were fully respected. Thus, materially enriched and mentally transformed, these youth would then lead the Japanese empire in its destined march toward global expansion.

This chapter examines the changes and continuities of Japan’s migration-driven expansionism between the eve of the First Sino-Japanese War and the first decade of the twentieth century. While the discourse of population growth and the idea of making model subjects through migration continued to legitimize overseas expansion, the ideal candidates for migration were no longer a countable number of shizoku but hundreds of thousands of ordinary youth. Migration was still an essential component of national expansion, but on an individual level it was no longer framed as restoring the honor of declassed men. Instead, it now aimed to provide lower class people with access to economic success and political power. The US mainland once again became the main destination of migration.

The chapter begins with an analysis of the rise of heimin as a major sociopolitical force in the last two decades of the nineteenth century and discusses its convergence with the early labor movement after the First Sino-Japanese War. It then examines the new discourse of migration-driven expansion that emerged from this context and explains why migration to America returned to the forefront of Japanese overseas expansionism. This analysis is centered on the ideas and practices of the Japanese Christian Socialists in their promotion of migration to the United States until the Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1908. The chapter concludes with a look at the decline of the heimin-centered discourse of America-bound migration after the Gentlemen’s Agreement went into effect.

The Rise of Heimin

Starting in the late 1880s, domestic political tensions surrounding the shizoku issue became diluted by the fever of overseas expansion and the materialization of promised political reforms such as the formation of the Imperial Diet and the enact of the Meiji Constitution. The decline of the former samurai class as a political force was accompanied by the rise of the commoners (heimin) as a voice in the political debate. The term heimin, as a political concept, carries different meanings and connotations in different contexts, but here it is used to specifically indicate the class of common youth who belonged to the generations born after the Tokugawa-Meiji transition. Most members of the heimin class had no inherited power or honor like the shizoku and possessed a distinct political consciousness.

The shift from shizoku to heimin as the center of Japanese political discourse mirrored the transition of Japanese social identity from one based on inheritance into one shaped by social and economic status. These changes reflected the horizontalization of Japanese society pushed by the forces of modernity. Although shizoku identity continued to be memorized as a symbol of honor and many continued to use their shizoku backgrounds for self-promotion, the title of shizoku no longer possessed the same political power as before. Some central heimin activists, though holding shizoku backgrounds themselves, embraced the idea of heimin as the idealized democratic subject position.Footnote 6

The early heimin activists believed that Japan’s existing political and social structures, still monopolized by inherited privilege and traditional value, had betrayed the spirits of egalitarianism and progress promised by the modern society. They argued that the nation should move forward by giving political and economic opportunities to individuals born without privilege. Tokutomi Sōhō, a prominent spokesperson for heimin, had grown up in a family of gōshi, wealthy peasants who obtained certain shizoku privileges by serving the Tokugawa Bakufu. Tokutomi strongly resented the full-fledged samurai who had looked down upon him since childhood because of his inferior social background.Footnote 7

In 1886, Tokutomi published his heimin-centered blueprint for Japan’s nation-building, The Future Japan (Shōrai no Nihon). He observed that the nineteenth-century world was an arena of international competition where only the fittest could survive.Footnote 8 Hidden behind the wars and arms race was the true rivalry of national wealth. In other words, nations ultimately competed with each other in terms of economic productivity and trade.Footnote 9 In the past the samurai had enjoyed political and economic privileges due to their status as military aristocrats without engaging in any form of economic production. But, argued Tokutomi, the samurai could no longer lead such a parasitic life in the new society now. The heimin, as the main body of economic production, were now replacing aristocracy and emerging at the center of national and global politics – a trend that was proven by both the French Revolution and the American Revolution.Footnote 10 In order to survive and gain the upper hand in international competition, Japan had to follow this global trend by allowing its common people to take up the mantle of leadership.Footnote 11

In the next year, Tokutomi established the Association of the People’s Friend (Minyū Sha) to disseminate ideas of commonerism (heiminshugi), calling to form a nation and empire led by commoners. The association’s official journal, Friend of the Nation (Kokumin no Tomo), began its circulation the same year. Tokutomi’s promotion of heimin-centered nationalism and the increasing popularity of his works among the general reading public revealed the society’s lack of upward mobility. This predicament of common youth was well captured by two contemporary works of fiction. Mori Ōgai’s The Dancing Girl (Maihime), first serialized on Friend of the Nation upon Tokutomi’s request, described a tragic romance between an ambitious but unprivileged Japanese man and a German dancing girl. Under a plethora of social pressures, the protagonist eventually had to discard his true love in order to gain his dream job—an elite position within the government bureaucracy. Futabatei Shimei’s The Drifting Cloud (Ukigumo), on the other hand, told the story of a well-educated and hardworking young man from an aristocratic family in the Tokugawa era who failed in both his career and love because he refused to be a sycophantic social climber in Meiji society.Footnote 12 The protagonists in both stories were young men of promise who either graduated from a hyperselective university or were born into an established family. Most common Japanese youth had no access to the privileges enjoyed by either of them. Nevertheless, the protagonists’ struggles against the social barriers that belied the premise of modernization were shared by all the commoners in Meiji Japan. Even those who were wealthy enough to study at the bourgeoning private colleges faced serious discriminations compared with their counterparts from imperial universities on an already oversaturated job market. A journal, The Youth of Japan (Nihon no Shōnen), claimed in 1891 that private college graduates in the fields of politics and economics had only a 50 percent employment rate.Footnote 13 These jobless graduates were joined by a much larger number of rural and urban youth who could not afford higher education but still held high expectations for their own future inspired by the spirit of egalitarianism.

Tokutomi blamed this lack of opportunities for the commoners on the aristocrats who would not let go of their stranglehold on the country’s politics and economy. In his essay “Youth of the New Japan” (“Shin Nihon no Seinen”), Tokutomi called those with inherited privileges “old men of Tenpō” who clung to traditional values and made no contribution to the nation’s advancement.Footnote 14 In his view, these aristocrats should yield to the flow of history and make way for the commoners, who were the young and progressive harbingers of the future.

How, then, did Tokutomi envisage a society of commoners? It was not only an egalitarian society that gave political rights to the common people through electoral democracy, but also one that provided a fair platform where ordinary men could achieve economic success by their own efforts. In order to realize this goal, he argued, society needed to operate according to the principles of self-independence and self-responsibility. Unlike the old shizoku and kazoku aristocracies who lived as social parasites, everyone in the nation of heimin should earn their own living. “Their brows are wet with honest sweat … and they do not owe to any man.”Footnote 15 Tokutomi deemed the desire for a career (shokugyō no kannen) so important in the formation of independent subjects of the nation that he went as far as calling it the “new religion of Japan.”Footnote 16

The ideal image of the heimin, therefore, was the working class that emerged from Japan’s fledgling capitalist society in the late nineteenth century. Friend of the Nation described them as “workers” (rōdōsha). Accordingly, the publication was sensitive to class-based exploitation and sympathetic to the working class’s poverty. An 1891 article, for example, argued that the working class was of a noble character and should receive fair payments for their labor. In order to transform itself into a nation of heimin, Japan should emulate the model of the Western countries where, according to the article, the workers were treated well and allowed to have a share of the profits.Footnote 17

Tokutomi’s promotion of the rights of the commoners was closely associated with his vision for Japan’s empire building. The economic independence of the commoners and their rise to power as a sociopolitical force in domestic Japan mirrored the Japanese empire’s claim of its own rights of expansion on a global stage that was previously dominated by the Western imperial powers. The development of a heimin nation, Tokutomi argued, would better prepare Japan to survive and prosper in a social Darwinist world. In the book On the Expansion of the Great Japan, he reasoned that the expansion of an empire was dependent upon the expansion of its individual subjects. He encouraged Japan’s commoners to follow the examples of the British, the Chinese, and the Russians to migrate to every corner of the world as the pioneers of Japanese expansion.

The First Sino-Japanese War and the Heimin Expansion

Prior to the First Sino-Japanese War, support for the heimin discourse was limited to Minyū Sha members and their intellectual followers who had few interactions with the working class. After Japan’s victory over Qing China, however, the heimin discourse became closely associated with Japan’s burgeoning labor movement. This movement arose amid the boom of Japanese industrial development triggered by the Sino-Japanese War. Tokutomi Sōhō’s proto-socialist ideas of nation building were picked up, though in revised forms, by the socialist thinkers and activists in their campaigns calling for political and economic rights of the workers. The heimin-centered discourse of Japanese expansion was eventually materialized in the Christian Socialists’ campaigns for moving working-class youth to the United States.

A year after the end of the First Sino-Japanese War, Tokutomi lamented the loss of Japan’s “national energy”: the Japanese policymakers ended the war without capturing the Qing Empire’s capital of Peking (now Beijing), a decision that destroyed the Japanese populace’s wartime passion for expansion and progress. Deluded by the illusion of peace, he observed, young people gave up their noble goals of studying politics, religion, science, and philosophy and turned to moneymaking.Footnote 18 In fact, Japanese nationalism and expansionism did not come to an end after the conclusion of the First Sino-Japanese War – it simply manifested itself in a different form. However, Tokutomi was correct to notice that the heimin discourse had taken a decidedly materialistic turn.

The common Japanese economic optimism and thirst for monetary gains, stimulated by war’s end, was demonstrated by the sudden popularity of business schools. While they had a hard time filling their seats before the war, these business schools began to enjoy full registration, and some were even able to admit students selectively right after the war.Footnote 19 The decade following the war also witnessed a boom in writings on personal economic success in print media. Business Japan (Jitsugyō no Nihon), a journal aimed at selling business courses to students without a formal education, was founded in 1897.Footnote 20 Magazines of different ideological stances and backgrounds, such as the Sun (Taiyō) and the Central Review (Chūō Kōron), introduced special columns that published rags-to-riches stories and tips on moneymaking ventures. The most widely circulated journal representative of this era was Seikō (Success), founded by Murakami Shūnzō in 1902. Its circulation reached fifteen thousand within three years.Footnote 21

The discourse of success embodied by Seikō and other magazines of the day was directly derived from the idea of commonerism promoted by Tokutomi Sōhō. Like Tokutomi, Murakami characterized the heimin as a young and progressive group that should replace the “conservative” old men and lead the nation to a better future.Footnote 22 Like the Hokkaido expansionists decades ago, Murakami was promoting a story of personal achievement. However, this time the protagonist was no longer the declassed shizoku who would regain their previous honor and dignity: now the common youth, who were born without any privileges, would lift themselves up through hard work.

The flood of literature on material success was in direct contrast to the stark economic reality. The First Sino-Japanese War did stimulate military and civil industry expansions, marked by a rapid increase in the numbers of factories and wage laborers. Yet it was soon followed by a severe depression that resulted in a far-reaching wave of bankruptcy and unemployment. Income declines and deteriorating working conditions led to the rise of the labor movement. The backbone of this movement, the young working class, was also the main audience of the discourse of materialistic success. As its celebration of moneymaking spoke to the wage laborers’ hope for financial advancement, its call for more employment opportunities for the common youth also matched the working class’s resentment of class exploitation and economic inequality.

While Tokutomi expressed sympathy toward the laborers, this materialistic version of commonerism was associated more closely with the working class and converged with Japanese socialist thoughts at the turn of the twentieth century. Unlike the later wave of socialist movements that directly challenged the existing political structure after the Russo-Japanese War, this early version of socialism, while critical about the political status quo, did not seek to upend it. Influenced by Protestant Christianity,Footnote 23 Japanese Socialists of the day considered self-help as the ultimate solution to working-class poverty. They sought to bridge the social gap through interclass reconciliation as well as religious and moral suasion on the poor. Leading socialists such as Katayama Sen and Sakai Toshihiko were key supporters of the idea of self-help and published articles in Seikō to promote materialistic success. Rōdō Sekai (Labor World) – the mouthpiece of the labor movement of the day – and Seikō also carried advertisements for each other.Footnote 24

In the heimin thinkers’ agenda of nation building at the turn of the twentieth century, the ideal subjects of the empire were no longer the shizoku but the common working-class youth epitomized by work-study students (kugakusei), poor boys who worked their own way through school.Footnote 25 Like the shizoku expansionists in earlier decades, some heimin ideologues also embraced overseas migration as the foundation of Japan’s nation making and empire building. The idea of Malthusian expansionism, lamenting the overcrowdedness of the archipelago on the one hand and emphasizing the importance of migration in producing desirable subjects on the other, continued to guide their various agendas for expansion. Attributing the lack of opportunities for common youth to the nation’s growing size of surplus population, heimin expansionists believed that overseas migration would allow ambitious young men to achieve economic independence. Convinced that the future of the Japanese empire lay in frontier conquest and territorial expansion, they expected that these common youths would rise to positions of leadership in the empire by building settler colonies abroad.

Resurgence of Japanese Migration to the United States

Japan’s victory over Qing China in the First Sino-Japanese War relieved Japan’s racial anxiety caused by the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States, which previously had led the shizoku expansionists to explore alternative migration destinations. The war, as Tokutomi observed, cemented the Japanese hierarchical superiority over the Chinese in the racial imaginations of Japanese expansionism.Footnote 26 Tokutomi emphasized that the war opened the doors for Japan’s further expansion not only in Asia but also globally.Footnote 27 In other words, the war was fought for Japan’s global expansion and for its confidence to do so.Footnote 28

Tokutomi’s intellectual friend Takekoshi Yosaburō penned an article in Friend of the Nation at the end of the war, inviting his countrymen to consider, without regional and racial bias, Japan’s position in the world.Footnote 29 A graduate from the Keiō School,Footnote 30 Takekoshi inherited the school founder Fukuzawa Yukichi’s faith in de-Asianization. He believed that the Japanese should abandon the labels of Asia and the yellow race and “stand at the top of the world” by absorbing the essence of both East and West.Footnote 31 In 1896, a year after the war’s end, Takekoshi founded the journal Japan of the World (Sekai no Nihon), repositioning Japan in the hierarchy of world politics as a force on equal footing with the Western powers. For this venture he received financial support from two politicians who were involved in Japan’s diplomatic mission to revise its unequal treaties with the Western powers, Saionji Kinmochi and Mutsu Munemitsu.Footnote 32

This reembrace of the West was accompanied by a fundamental challenge to the Seikyō Sha thinkers’ discourse of racial conflict. While Seikyō Sha intellectuals believed in a destined rivalry between the yellow races and the white races, between East (Asia) and West. Takekoshi, on the other hand, criticized the definition of Asia as a culturally or biologically homogenous racial entity:

The races in Asia are different from each other, just like the Japanese race is different from the European races. There are different races such as the Caucasians, the Mongolians, the Malays, the Dravidians, the Negritos, and the Hyperboreans. … These are only general terms. After conducting a closer analysis of the Chinese, who share the same language and racial origin with us, we can see that not all the Chinese share the customs and traditions of the Mongolian races. …

If we only collaborate with those of our own race and exclude all others, we would end up not only excluding the Europeans but also the Asians as foreign races. … Asia is not a unified racial, cultural, or political entity. It is simply a geographical term, without any real meaning. Footnote 33

Takekoshi’s deconstruction of Asia’s racial homogeneity went hand in hand with his emphasis of the uniqueness of the Japanese race in relation to the rest of Asia. “Japan,” he explained, “is geographically separated from the Asian continent and is close to the heart of the Pacific Ocean. Its civilization is not that of the Mongolians but an independent one synthesizing the essence of different cultures in the world.”

This revision of Japan’s racial identity, made possible by victory over Qing China, served to conceptually delink Japan from Asia in general and China in particular. It allowed Japanese expansionists to draw a distinction between Japanese migration to the United States and the tragedy of Chinese exclusion therefrom. They believed that the Japanese were people of a master race like Westerners; as such, they would be welcomed by the white Americans in the United States, just as Japan would be accepted as an equal member in the club of civilized empires.Footnote 34 Fukuzawa Yukichi, for example, resumed his promotion of overseas migration in 1896. In an article urging his countrymen to build “new homes overseas,” he confirmed that the war had altered Japan’s racial identity: “The single fact that Japan has defeated the ancient and great country of China has changed the minds of the conservative, diffident Japanese people.” Fukuzawa further proudly announced that “in capability and in vigor, [the Japanese] are not inferior to any race in the world.”Footnote 35

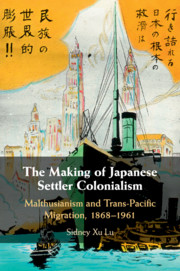

Figure 3.1 This is the cover of an issue of a popular magazine, Shōnen Sekai (The World of the Youth), published in 1895. The cover celebrates Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War. With the world map at the center, this picture also illustrates how this victory ushered in passion among Japanese intellectuals for the empire’s global expansion.

Thus, the rise of heimin as a sociopolitical force and the reimagining of the Japanese racial identity after the First Sino-Japanese War made the United States once more a favorable migration destination. Japan’s imperial-minded socialists connected their domestic sociopolitical campaigns to the mission of empire building. They believed that relocating the common youth to the United States would bridge the domestic social gap while contributing to their agenda of building Japan as a heimin-led egalitarian empire. The rest of this chapter analyzes three most representative and influential migration promoters of the day: Katayama Sen, Abe Isoo, and Shimanuki Hyōdayū. By examining the convergence and divergence of their migration-related ideas and activities, the following pages shed light on the different ways in which this wave of American migration was connected with the process of Japanese nation building and imperial expansion in Asia.

Divergence and Convergence in the Discourses of Heimin Expansion to the United States

The mid-1890s witnessed a proliferation of private migration companies in Japan. The increase in the number of trans-Pacific sea routes after the Sino-Japanese War allowed many of these companies to include the United States on their commercial maps.Footnote 36 These for-profit companies targeted the rural masses, individuals who usually had to take a huge risk by selling their properties in order to pay for their passage. Equally profit-minded, these rural migrants simply hoped to find temporary work as laborers abroad in order to lift themselves – as well as their families back in Japan – out of destitution.Footnote 37

In response to a series of anti-Japanese campaigns on the American West Coast targeting the migrant laborers since the early 1890s, the Japanese government enacted the Emigrant Protection Law in 1896. It was aimed at preventing “undesirable” migrants from entering the United States so that they would not bring “shame” upon the empire. It imposed financial requirements on both migration companies and the migrants themselves, hoping this would remove the uneducated and purely money-seeking laborers from the migrant pool. Within a few years, however, the imperial government realized that this law was all too easily circumvented, thus in 1900 it began to limit the number of passports issued for those who wished to travel to the United States.Footnote 38

The discourse of commoner migration to the United States emerged at this moment. The heimin expansionists were critical of the government’s restriction on overseas migration, considering it to be a shortsighted policy that dampened the common youth’s expansionist spirit or, worse, a malicious strategy of the bourgeois state designed to confine the working class to perpetual domestic exploitation. However, they shared the government’s view that the most desirable migrants were not the rural masses living in absolute poverty. While encouraging the migrants to accept laborer jobs, they believed that migration to the United States should not be solely for economic survival. These migrants should have long-term goals of self-improvement such as seeking higher education or business success; furthermore, they needed to connect their lives with the well-being of Japan. They also agreed with the government in that the for-profit migration companies should be blamed for indiscriminately sending “undesirable” subjects abroad, thereby stirring up anti-Japanese sentiments on the other side of the Pacific. Their own heimin migration campaigns, in contrast, would help the truly promising youth in Japan to circumvent government restriction and rescue them from the exploitative migration companies.

The thinkers and promoters of heimin migration were nearly unanimous in their Malthusian interpretation of Japan’s demographic trends. Like the shizoku expansionists in the previous decades, they appreciated Japan’s rapid population growth as a sign of swelling national strength. At the same time, the archipelago’s incapacity to accommodate this growing population made overseas migration both necessary and unavoidable. The heimin expansionists also integrated the logic of Malthusian expansionism into specific criticisms against Japan’s existing political and social order. Either sympathizers of the labor movement or outright socialists, they were also influenced by Protestant Christianity. They did not seek to fundamentally alter the structural foundations of the nation but strove for reconciliation and reformation, avoiding serious conflict rather than promoting it. Migration to the United States became a key component in their respective blueprints for transforming Japan into a commoner-centered nation and empire.

Different agendas of nation/empire building and different practical approaches shaped the heimin promoters’ interpretation of Japanese demography and the meaning of migration to America in divergent ways. The following paragraphs offer an analysis of the thoughts of three leading promoters – Katayama Sen, Abe Isoo, and Shimanuki Hyōdayū. During this wave of migration movement, each of them championed a specific vision about how migration would transform Japan into a heimin nation and empire.

Katayama Sen, a renowned leader of Japan’s socialist movement in the early twentieth century, followed the classic path of a struggling student in his own youth. He migrated to the United States in 1884 and worked to pay for his education. Having joined the socialist cause while in America, he returned to Japan right after the First Sino-Japanese War. He was a vanguard of the fledgling labor movement, working to organize labor unions and demanding improved working conditions and better pay for workers. From 1901 to 1907, he published a number of books and numerous articles in the mouthpiece of labor movement in Japan, Labor World (Rōdō Sekai), and beyond. In these writings he urged the common youth to migrate to the United States, offering them guidance through every step of the migration process, from how to circumvent governmental restriction to exploring job options and educational opportunities in America. To put his ideas into practice, he also established the Association for Migration to the United States (Tobei Kyōkai) and provided firsthand assistance to the migrants.

The existing scholarship has generally treated Katayama Sen’s promotion of migration and his socialist career as separate from each other, but his initiative in American migration was crucial to understanding his approach to the socialist movement in Japan at the turn of the twentieth century. Katayama believed that overpopulation within the archipelago had partially enabled class-based exploitation. The rapid growth of population caused domestic inflation, an increase in landless peasants, and rising unemployment.Footnote 39 The shortage of food and jobs forced the struggling working class to accept jobs with extremely low payment. Katayama argued that the government’s restriction on migration served only the interests of the rich: it was aimed to confine the working-class young men within the country, where opportunities for education and employment were scarce, so that the rich could better take advantage of this condition to exploit them.Footnote 40

Katayama had little trust in the state, and his eventual goal for the labor movement was not to build a socialist society centered around the governmental power.Footnote 41 However, he did share his contemporary Japanese socialists’ conservative stance, seeking to bridge the social gap not through revolution but by promoting ways for the working class to help themselves. While the formation of labor unions would strengthen the working class in general and put laborers in a better position vis-à-vis their employers, migrating to the United States, Katayama believed, would help them to escape capitalist exploitation in Japan altogether.

For Katayama and other migration promoters of the day, everything in the United States stood in glaring contrast to the miserable sociopolitical conditions in Japan. What’s more, with what he described as the vast, empty, and unexplored land on its West Coast, the United States could easily accommodate hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Japan.Footnote 42 Katayama further idealized the United States as the model of a socialist nation, a place where the role of labor was highly respected and the laborers were well paid. American labor unions were strong and their interests were protected by politicians and intellectuals. As a result, the United States was a nation where common people could make their own way by honest labor and succeed with a spirit of self-help. Japanese mass media of the day also portrayed rich American businessmen as sympathetic figures – unlike the selfish and bloodsucking entrepreneurs in Japan, American businessmen treated their employees well. They celebrated rags-to-riches success stories of Andrew Carnegie and Cornelius Vanderbilt as examples of not only self-made men but also those of kind philanthropists.Footnote 43

While Katayama saw assisting heimin youth to migrate to the United States as a way to fight the state’s oppression of the working class, the prominent social reformer and politician Abe Isoo, on the other hand, believed that the Japanese government should take the lead in guiding migration to the United States. In contrast to Katayama, who distrusted the government, Abe believed that the welfare state was key to the formation of a socialist nation. Abe agreed with Katayama that overpopulation worsened class exploitation and exacerbated Japan’s social problems; however, he argued that the condition of overpopulation meant there was a pressing need for state-centered socialist reforms.Footnote 44 He urged the government to take up the responsibility to improve the livelihood of common people. Migration was an effective way to provide employment and educational opportunities to members in a society plagued by overpopulation and inflation, thus the government should lift its restriction on migration and encourage the commoners to migrate overseas by providing both guidance and subsidization.Footnote 45

While Katayama and Abe represented two divergent perspectives on the role of the Japanese government in their socialist visions of nation building, Shimanuki Hyōdayū emphasized the importance of Christianity in his blueprint for Japan’s future. A Protestant priest and an enthusiast supporter of the Salvation Army’s socialist approach to evangelicalism, Shimanuki saw social philanthropy and Christianity-based moral reform as two sides of the same coin.Footnote 46 While sharing other socialists’ concerns about social inequality and poverty in Japan, he sought to combine materialistic solution with spiritual salvation. He established the Tokyo Labor Society (Tokyo Rōdō Kai) in 1897, later renamed as the Japanese Striving Society (Nippon Rikkō Kai). This organization was aimed at providing both financial aid and moral suasion to struggling students, whom he saw as the future of the nation.Footnote 47

Returning from a trip to the United States in 1901, Shimanuki was convinced that migration abroad, especially to the United States, was an effective way to realize his goal of national salvation.Footnote 48 Describing Korea as a hopeless and dying country, he warned that Japan was on the verge of a similar crisis. Overpopulation in Japan not only had enlarged the social gap and caused poverty but also would lead to a decline of the national spirit. Japan would follow the way of Korea if its young men refused to seek solutions abroad.Footnote 49 The United States was a country with vast, empty lands as well as many job opportunities. What’s more, it was the center of both Western civilization and Christianity. A move to the United States would both lift the Japanese youth out of poverty and save their soul by converting them to Christianity. Shimanuki referred to this process as “spiritual and physical salvation” (reiniku kyūsai), a phrase that became the Striving Society’s enduring motto. This dual salvation of the common youth, he believed, would lead to the eventual salvation of the nation.Footnote 50

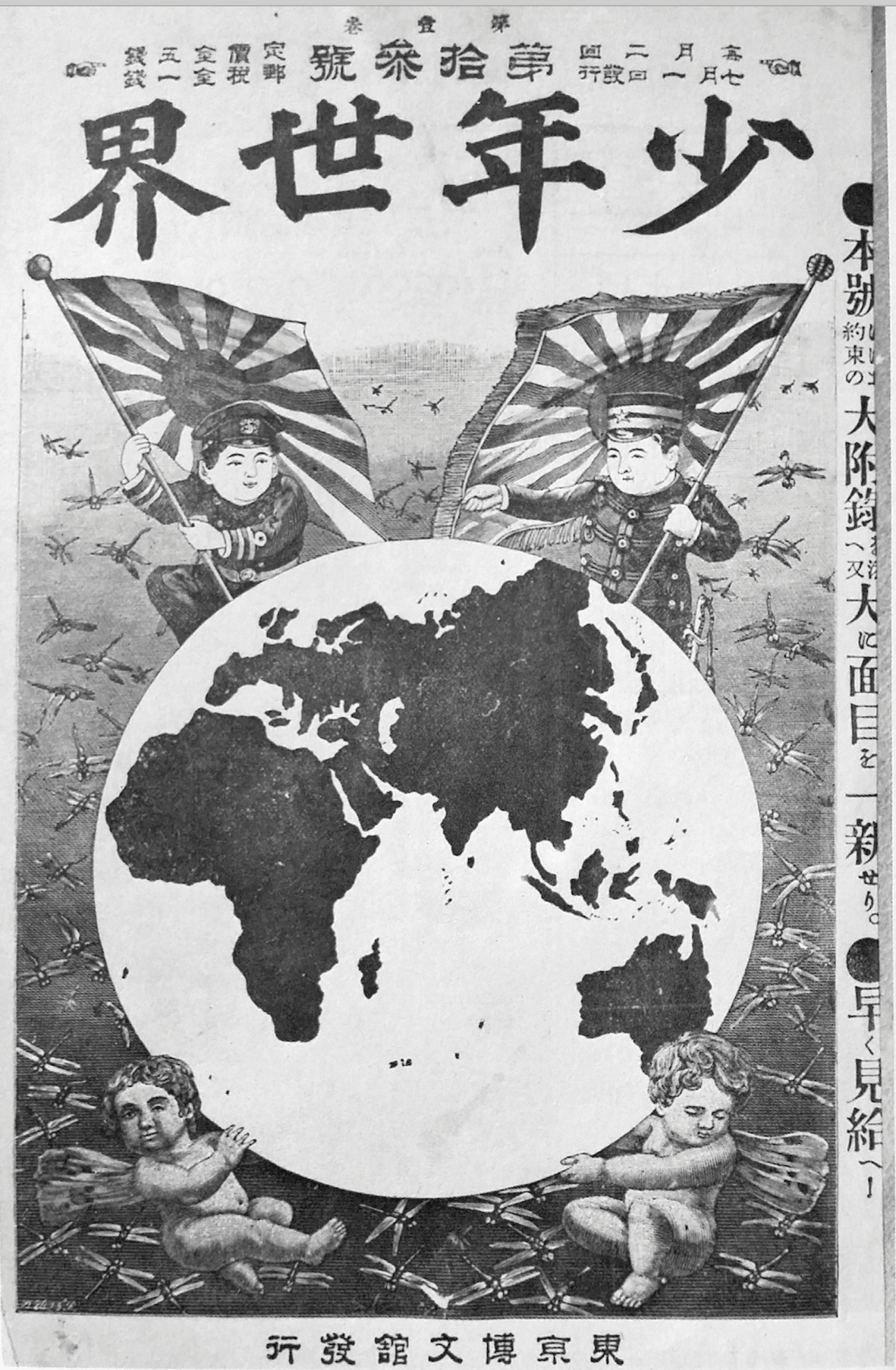

Figure 3.2 This is a symbol of the Striving Society that appeared in 1905. It connected the words of American migration (tobei), work-study (kugaku), success (seikō), and aspiration (risshi) together around the concept of striving (rikkō) at the center. Rikkō (Striving) 3, no. 1 (January 1, 1905): 1.

Differing understanding of the predicament of the heimin class shaped the agendas of these three migration promoters in divergent ways. However, as all three were converts to Protestant Christianity and at times spoke together at public events in support of labor movement in Japan, their ideas had definite points of convergence. On their global map of Japanese expansion, the United States was no doubt the most desirable destination. In their minds, Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, and Manchuria, areas controlled by or under the influence of Japan’s expanding empire, were already densely occupied by their native peoples. The local labor costs were generally low; thus it only made sense for entrepreneurs to move to these territories. The United States, on the other hand, was the ideal destination for the common youth because its labor market was favorable to the Japanese.

Yet like their shizoku counterparts in earlier decades, these heimin migration advocates did not see migration merely as a form of poverty relief. They believed that their project would mold migrants into model imperial subjects and trailblazers of expansion.Footnote 51 It only made sense, then, that migration should be a selective process. Though these advocates professed to be speaking for the working class, they nevertheless opposed temporary labor migration (dekasegi). Japanese temporary laborers usually made their way to the United States through migration companies or labor contractors; as most of them came from an impoverished rural background, they aimed only to make some quick money within a short period before returning to Japan. In the eyes of heimin expansionists, these temporary laborers had a dangerous resemblance to the “uncivilized” Chinese immigrants because they lacked in everything from education and social manners to long-term commitment.Footnote 52 They blamed these temporary laborers for sabotaging Japan’s national image aboard and causing anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States, leading the Japanese race down an ignominious path that might end in racial exclusion as the Chinese had suffered.

Those who did qualify for the migration project were the common youth, endowed with a certain amount of financial resources and education and who had a strong will for personal success and ambition for national expansion. The expansionists urged working, as laboring would be only their first step to starting their life in the United States, one that would allow them to achieve financial independence. Their personal growth, moreover, would not end there: Katayama expected these youth to replicate his own experience by pursuing higher education,Footnote 53 Shimanuki wanted their materialistic achievement to lead them to Christianity,Footnote 54 and Abe believed that life in the United States would positively influence these Japanese subjects due to their physical proximity to Western civilization.Footnote 55

While temporary laborers were considered undesirable and were likened to the excluded Chinese immigrants, the desirable candidates were expected to be colonial migrants (shokumin) with a commitment to long-term settlement. Heimin expansionists wanted them to build permanent communities in the United States as a part of Japan’s global expansion in the mode of British settler colonialism. They hoped that Japanese immigrants would be able to establish themselves as equal members of American society, thereby gaining political rights and economic benefits.

In the heimin expansionists’ blueprint for Japanese community building in the United States, the role of women was as important as that of men. Since the end of the 1880s, Japanese prostitutes had begun to arrive on the American West Coast, driven by their own poverty at home and the demand for commercial sex by the predominately male Japanese immigrant population across the Pacific. The expansionists condemned these prostitutes for bringing shame to the Japanese empire just like the low-class temporary Japanese laborers.Footnote 56 Katayama believed that prostitution was a result of the lack of education. To represent the civilized image of the empire abroad, Katayama urged that instead of prostitutes, more well-educated Japanese women should migrate to the United States. For Katayama, the arrival of educated women was also crucial for Japanese American community building, because he believed that the immoral behaviors committed by Japanese men in the United States, such as gambling and frequenting brothels, were due to the lack of women. These women of good nature and culture would thus improve the ethics of Japanese American communities in general by regulating the mind and behavior of Japanese men.Footnote 57 From a similar perspective, Abe Isoo called for a governmental ban on the migration of prostitutes to the United States and the formation of special organizations to facilitate Japanese women’s trans-Pacific migration and their adjustment to the new life in the United States.Footnote 58

The migrants’ success in the United States, in the minds of the expansionists, would both increase Japan’s political influence and stimulate the Japanese economy by enhancing bilateral trade. In addition to bringing economic benefits to Japan, heimin migration to the United States also provided ideological justification for the empire’s expansion in Asia. Abe Isoo, for example, described Japan as “the broker of civilization,” buying it from the United States and then selling it to China and Korea; it was thus natural for the Japanese to hold a base at the Western end of the North American continent.Footnote 59 While the United States had a mission of bringing the blessing of civilization to Japan, Abe argued, Japan had a similar obligation to spread the same blessing to the Asian continent.Footnote 60 Shimanuki Hyōdayū also believed that the migrants would be made into better Japanese subjects once they moved to the United States and converted to Christianity; thus migration was the first step in the empire’s mission to transplant progress to East Asia.Footnote 61 To Shimanuki, who began his religious career as a missionary in Korea, the philanthropic assistance he provided to the struggling students was a way to achieve his ultimate goal of evangelizing Asia.Footnote 62 The prosperity of the Japanese communities in the United States, in terms of both economic success and spiritual salvation, was crucial in justifying Japan’s acceptance of the global hierarchy arranged according to the degree of Westernization and legitimizing the empire’s colonial expansion in Asia.

The Decline of Japanese Labor Migration to the United States

The heimin migration discourse peaked around the time of the Russo-Japanese War. In the minds of the Japanese expansionists, a victory over the Russians would give Japan yet another bargaining chip during its negotiation with the Western powers for global expansion. Foreseeing Japan’s victory, an article on Striving (Rikkō), one of the official journals of the Japanese Striving Society, predicted that the war would bring a great opportunity to boost Japanese migration to the United States. The author argued that Japan’s victory would end anti-Japanese discrimination in the United States because the Americans would finally recognize Japan as a strong power and treat the Japanese immigrants with respect.Footnote 63 A few days after the war ended, Abe published his most important work for the promotion of America-bound migration, urging Japan’s government and social leaders to work together in order to build a “new Japan in North America” (hokubei no shin nihon). He assured his readers that the US government, fearful of a powerful Japan’s reprisal, would not dare to exclude Japanese immigrants. Moreover, as Japan had now achieved effective hegemony in East Asia, the empire could claim its own version of the Monroe Doctrine and exclude the interests of the United States from Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula.Footnote 64 Such optimism led to a sharp increase in the number of Japanese migrants to the United States after the Russo-Japanese War: the numbers of Japanese who migrated to the US mainland from Japan and Hawaiʻi in 1906 and 1907 more than doubled from their prewar levels.Footnote 65

The eventual fate of Japanese migration to the United States, however, did not bear out such optimism. Contrary to Japanese expectations, the Russo-Japanese War triggered an unprecedented wave of Japanese exclusion campaigns in the United States. Japan’s defeat of Russia ironically served as fresh ammo for the racial exclusionists who called for keeping the uncivilized and aggressive Japanese out of the white men’s world. The decision by the municipal government of San Francisco in 1906 to exclude Japanese children from public schools demonstrated that anti-Japanese sentiment had gained support from the policymakers in the Golden State. In September 1907, a long article appeared in the New York Times titled “Japan’s Invasion of the White Man’s World,” describing the Japanese as inassimilable intruders into American society. The Malthusian interpretation of Japanese demography, cited by the Japanese expansionists to justify their migration agendas, was used by the article as a reason to exclude the Japanese. It argued that having failed to export migrants to Hokkaido, Taiwan, Korea, and Manchuria, Japan was now sending its surplus population to America, the white men’s domain. The Russo-Japanese War, the article warned, showed that Japan was a dangerous threat. If given the opportunity, it might invade America by force. The Japanese immigrants who refused to assimilate into US society would serve as Japan’s vanguards in such an invasion.Footnote 66

This lengthy report showed that anti-Japanese sentiment had spread beyond the American West Coast and gained a nationwide audience. Its political influence resulted in the Gentlemen’s Agreement between Japan and the United States that came into effect in 1908, in accordance with which the Japanese government voluntarily stopped issuing new passports to those who planned to migrate to the United States as laborers. In exchange, the Roosevelt administration promised to not impose official restrictions on Japanese immigration and also managed to remove the ban on Japanese immigrant children from attending public schools in San Francisco through a negotiation with local officials.

Based on the Gentlemen’s Agreement, the Japanese government enacted a near-complete ban on migration from Japan to the US mainland.Footnote 67 There were only a few exceptions to this ban, including remigrants, family members of migrants already in the United States, as well as government-approved agricultural settlers. As a result, the main body of trans-Pacific migration became the so-called picture brides, young women who entered the United States as the wives of Japanese immigrants already in the United States. They were urged to project a civilized image of the empire and foster Japanese community building in American society. The male-centered commonerist discourse of previous years, however, had died out due to this drastic policy change.

The Gentlemen’s Agreement thus brought the decade-long wave of heimin migration to the United States to a sudden end. Hoping this unexpected roadblock would be quickly removed via diplomatic renegotiations, migration promoters continued to mobilize their countrymen with rosy images of the United States. However, the demises of Amerika (the successor of Tobei Zasshi) and Tobei Shinpō in 1909, respectively the mouthpieces of Katayama and Shimanuki’s migration campaigns,Footnote 68 marked the total collapse of such an illusion.

The end of labor migration to the United States mirrored the decline of heimin expansionism in the late 1900s. The Gentlemen’s Agreement forced Katayama and Abe to give up their plans of turning Japan into a heimin-centered nation and empire through migration. The powerful Hibiya Park rallies and riots between 1905 and 1908 also convinced them that making structural changes in domestic Japan was actually possible, though they disagreed completely as to how to bring these changes about – or indeed what these changes were.

Katayama began to follow a path similar to his radical comrade Kōtoku Shūsui. In 1909 he began to criticize the Christian churches in Japan for being dominated by the rich and thus lacking the initiative to solve the country’s social and economic issues.Footnote 69 He abandoned his Christian faith and turned to materialist Marxism as the ultimate solution, seeking a more radical method to achieve his goals. He was arrested for leading a labor strike in Tokyo in 1911, the same year that Kōtoku Shūsui was executed for a failed plot to assassinate the Meiji Emperor. After being released, Katayama went to the United States again and took part in the labor movement in Japanese American communities. Inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, he became a Leninist. He participated in the international communist movement and was eventually buried in the Kremlin.

Abe Isoo, on the other hand, continued to regard overpopulation as the central issue that blocked Japan’s path to a better future. With the doors to the United States now shut, he turned to promoting contraception and played a key role in Japan’s birth control and eugenic movement during the 1920s and 1930s. While the exclusionists in the United States taught the Japanese expansionists that migration to the white men’s domain was impossible, it was another American, Margaret Sanger, who provided the Japanese with the “correct” solution to their “problem” of overpopulation. While the idea of birth control was introduced to the Japanese much earlier, it never gained nationwide support until Sanger visited Japan in 1922. Celebrated as the “Black Ship of Taishō,”Footnote 70 Sanger’s speaking tour in Japan vested the advocates of birth control and eugenics in Japan with a degree of much-wanted legitimacy: progress and science.Footnote 71 In the year of Sanger’s visit, Abe published the book On Birth Control (Sanji Seigen Ron) in which he turned away from his earlier criticism of capitalism and class-based exploitation. He now argued that overpopulation was the fundamental cause of social issues such as labor disputes, rural poverty, and gender inequality in Japan as well as the world at large. Contraception, accordingly, was the ultimate solution.Footnote 72

However, Abe’s agenda of population control was not simply aimed at reducing the birth rate. Abe, who subscribed to Sanger’s idea of “more children from the fit, less from the unfit,”Footnote 73 had a clear eugenic teleology. He believed that the American exclusion of Japanese immigrants was caused by the migrants’ undesirability,Footnote 74 and he called for improving the quality of the Japanese race by preventing the reproduction of the “unfit” who either had genetic flaws or did not possess enough resources. It was not uncontrolled population growth but the selective reproduction, coupled with quality control, that would lead Japan to success on the world stage.Footnote 75

In the same year, Abe put his ideas into practice as the director of the Japanese Birth Control Study Society (Nihon Sanji Chōsetsu Kenkyūkai). Labor union leader Suzuki Bunji, whose moderate stance represented that of the labor movement in the 1920s and 1930s in general, became Abe’s loyal supporter. Under what was insightfully defined by Andrew Gordon as “imperial democracy,” Japan’s labor unions at the time did not wish to pose radical challenges to the status quo. The labor movement sought to strengthen its political power by forming alliances with bourgeois parties; it celebrated imperial wars and expansion.Footnote 76 These moderate socialists and labor activists were soon joined by leading feminists and prominent physicians. Though they disagreed with each other on a multitude of issues, all of them considered eugenic-oriented contraception as an effective way to realize their social agendas. Together they constituted the main force of the birth control movement in Japan between the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 77

Conclusion

“Fighting with the Qing was fighting with the world.”Footnote 78 Tokutomi’s contemporary observation insightfully captured the fundamental changes the First Sino-Japanese War brought to Japanese expansionism: it ushered in the resurgence of Japanese migration to the United States and the rise of heimin expansionist discourse. This chapter has argued that the emergence of heimin as a sociopolitical force in Japan, stimulated by the First Sino-Japanese War, shifted the focus of migration-driven expansion from the declassed shizoku to working-class youth. The outcome of this war also convinced the Japanese of their racial superiority over the Chinese, creating an illusion among the expansionists that the Japanese, members of a civilized empire and a master race in their own right, could be treated by the Westerners as their equals. Buoyed by such optimism, they once again turned their gaze to the United States as the ideal destination for Japanese migration.

In 1907, Kōtoku Shūsui, a leader of Japan’s socialist and anarchist movement, published the book Commonerism (Heiminshugi), outlining his political agenda for turning Japan into a nation of commoners. A pioneering critic of imperialism and a strong opponent of war and expansion, Kōtoku was on the very opposite end of the ideological spectrum from his contemporary Tokutomi Sōhō. Nevertheless, Kōtoku’s vision of a heimin nation resembled Tokutomi’s own in terms of calling for the heimin to have political rights, adopting a sympathetic approach to the issue of working-class poverty, and celebrating historical progress.

As this chapter has shown, the leaders of Japan’s socialist movement at the turn of the twentieth century became the loyal heirs of Tokutomi’s heimin-centered nationalism and expansionism. They connected the pursuit of political rights for commoners with improving the economic conditions of the working class. The majority of the socialist leaders of the day did not adopt Kōtoku’s revolutionary stance; they sought moderate ways to achieve their goals, ready to work with the political establishment and lending their support to imperial expansion.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, migration to the United States served as a way for socialists of different viewpoints to realize their particular blueprints of Japanese nation/empire building. As adherents of Malthusian expansionism, Katayama Sen, Abe Isoo, and Shimanuki Hyōdayū all blamed overpopulation for widening the social gap and causing poverty in Japan. Seeing the United States as a land of boundless wealth, a heaven of laborers, and the center of world civilization, they hoped migration to the United States would save Japan’s working class from exploitation and poverty. Moreover, they envisioned that these migrants would be turned into model subjects who could fulfill the Japanese empire’s own Manifest Destiny.

Racism on the other side of the Pacific led to the decline of Japanese labor migration to the United States at the end of the 1900s. While they subsequently followed divergent paths due to their different approaches to socialism, both Katayama Sen and Abe Isoo ceased their promotion of migration to the United States.Footnote 79 Shimanuki, however, continued to help young men to move to the United States via smuggling. Starting in the mid-1900s, reports on the Japanese Striving Society’s members’ expeditions to Korea, China, and Latin America began to appear in the society’s official journals such as Rikkō and Kyūsei. While maintaining that the United States was the most ideal destination, Shimanuki began to encourage his followers to explore other parts of the world for migration purposes.Footnote 80

The first decade of the twentieth century also witnessed a short-lived campaign of Japanese farmer migration in Texas. Like the labor migration to the US West Coast, the farmer migration was another campaign in the wave of heimin expansion. But different from the labor migration that was centered on the urban working class, the backbone of this campaign of migration was Japanese farmers, the nonprivileged but politically conscious rural commoners. This campaign was also a joint product of the anti-Japanese sentiment in the American West and the rise of the Japanese agrarianism at the turn of the twentieth century. Chapter 4 examines the Texas migration campaign and explains the significance of this short-lived campaign in the history of Japanese migration-driven expansion.

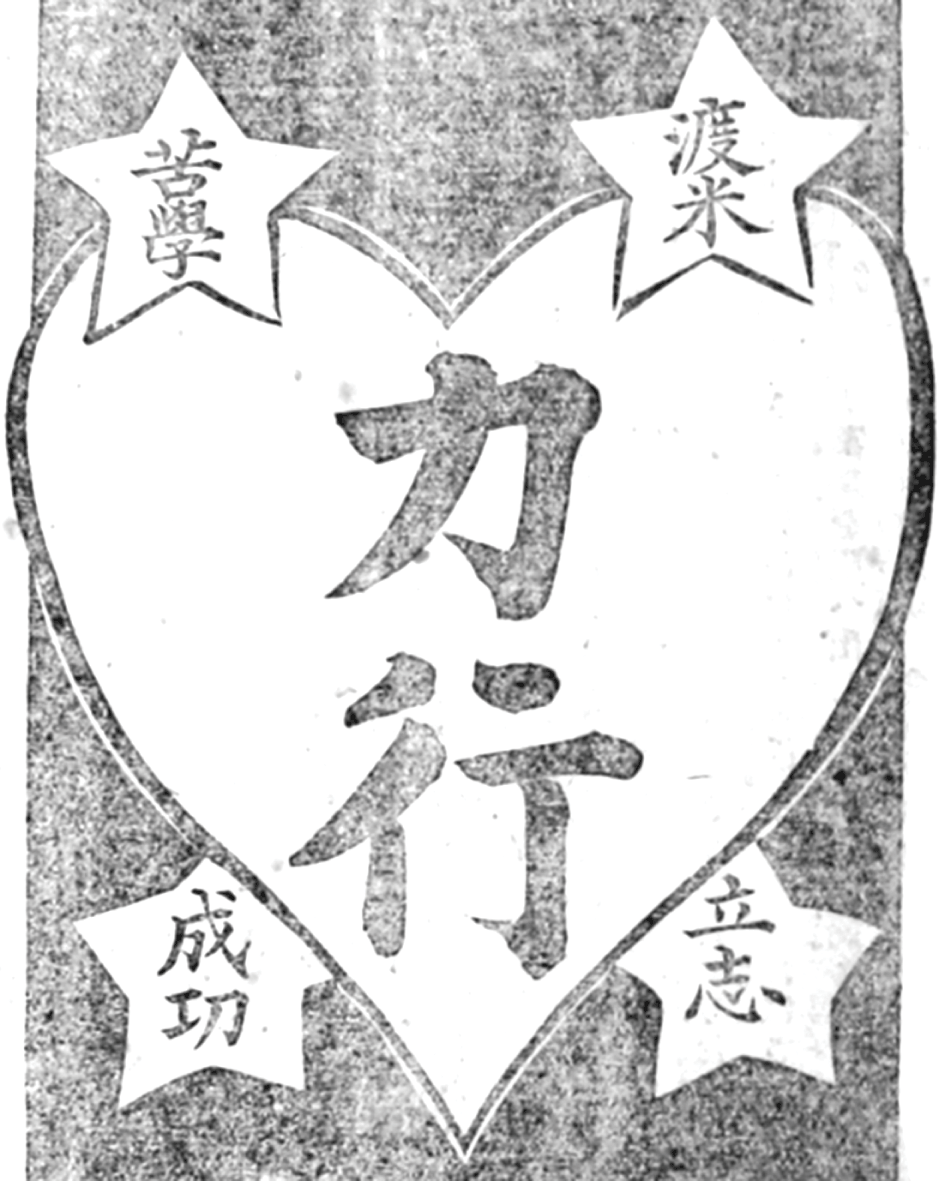

Figure 3.3 This is a symbol of the Striving Society that appeared in 1909. Compared to the one from 1905, “colonial migration” (shokumin) has replaced “American migration” (tobei). This demonstrates that after the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement the Striving Society no longer considered the United States as the only ideal destination for migration and began to explore the possibility of migration to other parts of the world. Kyūsei 5, no. 81 (November 1909): 1.