4.1 ‘Unknowne to us’

Even as they work to perfect medieval manuscripts, early modern acts of correcting, glossing, repairing, completing, and supplementing all recognise a value that is intrinsic to these old books. Behind the choice of readers to improve outdated copies of Chaucer, in other words, is an appreciation of a special cultural status ascribed to them. From their attention to minute linguistic and orthographic details, to lacunae in the manuscripts, and to the completeness of the Chaucerian canon, the transformations made by readers to these volumes intersect, in one way or another, with broader matters of textual, literary, and bibliographical authority. For all Chaucer’s apparent ambivalence to the idea of poetic auctoritas, his posthumous fate would be to become the pre-eminent English author, and his books were increasingly framed by the signs of this authority. To grant a book or a text such authority might take many forms. It is a quality that could be inscribed not only by virtue of the individual who wrote a literary work, but also by means of other characteristics associated with them: their place in historical memory, their larger body of work, their social or intellectual standing, or the authorities which they invoke in turn.Footnote 1

‘The Reader to Geffrey Chaucer’, a dialogic poem attributed to ‘H.B.’ in Speght’s editions, locates the ultimate seat of literary authority in the person of the author: ‘Where hast thou dwelt, good Geffrey all this while, / Unknowne to us, save only by thy bookes?’Footnote 2 This fictive Renaissance reader imagines a Chaucer who is absent, ‘save only’ for the ‘bookes’ in which his works have been presented since his death. Chaucer’s corpus has been neglected ‘all this while’, the reader complains, while the poem’s second speaker, a ventriloquised ‘Geffrey’, responds that this was true, ‘Till one which saw me there, and knew my friends, / Did bring me forth’. Given its placement within the preliminaries of Speght’s new edition, the poem serves as a paean to the editor, ‘who hath no labor spar’d / To helpe what time, and writers had defaced’. The poem thus traces a narrative that begins with Chaucer’s temporal exile and concludes with his return in the newly updated and accessible edition the reader holds in their hands. In staging an encounter between a revenant Chaucer and a grateful reader, the edition declares itself to be a new and different kind of book: one that Speght has ‘repair’d / And added moe’ and one that enables the enlivened Geffrey himself to emerge from its pages before the reader. The desire for the vernacular author to be expressly ‘knowne’ to readers was still unusual in Elizabethan England. More remarkable still is this interest in the author-figure which is related to but ultimately distinct from an interest in his ‘bookes’. Yet this is precisely the dialogue’s central premise: Speght’s edition repairs not just Chaucer’s neglected volumes, but as good as revives the man himself. It is a sentiment expressed in the volume’s prefatory epistle, addressed to Speght by Francis Beaumont: ‘in the paines and diligence you [Speght] haue vsed in collecting his life, mee thinkes you haue bestowed vpon him more fauorable graces then Medea did vpon Pelias: for you haue restored vs Chaucer both aliue again and yong again’.Footnote 3 As Lucy Munro has noticed, Beaumont’s reference is to Medea’s empty promise that the youth of the ageing Pelias would be restored if he were killed, cut up, and his body parts boiled.Footnote 4 At first glance, Beaumont’s macabre allusion to this murderous ruse from Greek mythology is tonally peculiar in the context of praise for Speght’s new edition. Its message, however, is clear: in contrast to the dead and dismembered Pelias, Chaucer has been reconstituted by the new biography (or ‘Life’) published under Speght’s name. The effectiveness of the conceit relies upon the imagined contiguity of bibliographical and bodily completeness, and adds to them a biographical element. This new book of Chaucer, Beaumont suggests, has gathered up and recomposed both his works and his Life, such that they enable a virtual reanimation and rejuvenation of the poet himself. Beaumont’s rhetorical play between ‘life’ and ‘aliue’ points to the perceived role of Speght’s apparatus in resurrecting Chaucer’s reputation, his biography, and his works.Footnote 5 Both the reader’s dialogue with ‘Geffrey’ and Beaumont’s letter work rhetorically to persuade readers of the edition’s merits, and their hyperbole is bolstered by the fact that Speght’s paratextual additions broke genuinely new ground in the history of editing Chaucer. The edition gave Chaucer an English-language Life and a glossary for the first time, while its specially commissioned genealogical portrait was a technological novelty and one of the first engraved portraits of an English author. Arguments, lists of authors cited, a Latin stemma of his noble descendants, and glosses on the poet’s foreign borrowings are all further additions covered by H.B.’s claim that Speght had ‘added moe’ to Chaucer’s old books. As Speght and Beaumont tell it, such innovations make all the difference between an ‘unknowne’ Chaucer and a famous one, the one dead and the other ‘aliue and yong again’.

This enhanced paratextual presentation has been recognised as pivotal to the ‘invention of Chaucer’s preeminent, mythic status’ in early modern print.Footnote 6 As Machan puts it, ‘Throughout the Renaissance period, no other Middle English writer is presented with this kind of critical apparatus or the status it imputes’, and such a treatment was exceptional for any English author in the sixteenth century.Footnote 7 The innovative nature of these editions has long been known, but much less attention has been afforded to the engagement of readers with this apparatus and with the ideas of English authorship that it promotes. Recent work by Megan Cook and Hope Johnston represents an exception in this regard. Johnston’s 2015 essay on readers’ memorials and commemorations of Chaucer in early editions concludes that ‘The ways in which owners of early editions of Chaucer altered their books represent forms of reception that have yet to be considered fully’.Footnote 8 This book has been arguing that medieval manuscripts, too, preserve vital evidence of Chaucer’s early modern reception, and that they merit consideration alongside the printed editions against whose backdrop they were often read in the early modern period. Accordingly, this chapter looks to medieval manuscripts which passed through the hands of early modern readers and finds evidence that reveals what readers made of the new conventions for presenting Chaucer. It draws attention to readers’ striking embellishment of manuscripts with authorising paratexts in the same period that parallel conventions commemorated Chaucer in contemporary prints, and determines that this new presentation of Chaucer the man and of his works in print gave rise to an attributional and biographical interest on the part of his early modern readers. Inscriptions of the author’s name, lists of contents, standardised titles, comments on the canon, snippets of biography, and even imitations of his printed portrait were added to older manuscripts (and sometimes prints) by early modern and eighteenth-century readers who sought to perfect those volumes according to the new standards of literary authority codified in print. Their concerns about Chaucer’s name, canon, life, and image reflect a new investment in paratextual expressions of literary authority and furnish direct evidence for print’s role in crafting a preoccupation with the author in the early modern book.

4.2 Canonicity and ‘Chaucer’s goodly name’

Chaucer knew well the value of the author’s name and its relation to poetic glory, however illusive such fame might be. Memorably, the House of Fame’s Chaucerian dreamer denies that he seeks fame and declines to name himself when asked: ‘For no such cause, by my hed! / Sufficeth me, as I were ded, / That no wight have my name in honde’.Footnote 9 Ever in pursuit of fame on his own terms, Chaucer nonetheless took care to embed his name into his works.Footnote 10 Fifteenth-century manuscripts also reveal a scribal interest in conveying the author’s name – not only on the part of well-known figures like John Shirley, who famously added titular rubrics naming Chaucer to his manuscripts, but also by the scribe of the celebrated Ellesmere manuscript, who wrote a colophon identifying the work as compiled by Chaucer, as well as the many others who routinely labelled Melibee as The Tale of Chaucer in the running titles, incipits, and explicits of surviving manuscripts.Footnote 11 These written traces reinforce a point illustrated in studies by Alistair Minnis and Alexandra Gillespie: that the cultural worth of the vernacular author’s name and canon was already well recognised by those who copied and commissioned manuscript books in the era before print.Footnote 12

In the early modern period too, the claim of his poetic greatness was ‘very firmly attached to Chaucer’s name’.Footnote 13 As Gillespie has shown in relation to Chaucer, medieval authorising traditions were successfully adapted and multiplied in print. Chaucer, whose name had been associated with poetic and rhetorical excellence since the early fifteenth century, was the first English poet to be granted a single-volume collection of Workes when Thynne produced his first edition in 1532. Print thus afforded the author more widespread visibility and cultural prominence.Footnote 14 On the printed title pages of lyric poetry collections and of professional playbooks as well as in poetic miscellanies compiled in manuscript, the English author’s name acquired greater literary weight in the second half of the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth.Footnote 15 This growing emphasis on identifying named authors is exemplified by Robert Crowley’s address ‘The Printer to the Reader’ in the first edition of Piers Plowman (1550), which opens with the proclamation that the publisher was ‘desyerous to knowe the name of the Autoure of this most worthy worke’.Footnote 16 Scribes and early readers of Piers had long puzzled over the question of the author’s name (prompted, in part, by the elusiveness of the poem’s authorial voice), but the publication of new books by John Bale and by Crowley in the mid-sixteenth century has been identified as a turning point at which ‘[a]fter nearly two centuries of anonymity, Langland comes to have a name and a public identity’.Footnote 17 This is not, however, a tale of obscurity in manuscript yielding to a new awareness of named authors in print; both the writerly self-awareness that characterises the work of Chaucer and Langland (and their fifteenth-century successors) and the persistence of anonymous writing conventions in the early modern period warn against such a reading. It is more instructive to adopt North’s characterisation of the relationship between medieval and early modern conceptions of authorship as a ‘recurring echo rather than an evolution’,Footnote 18 and, where Chaucer is concerned, to observe print’s role in amplifying, rather than inaugurating, the cultural emphasis on authorship in the early modern period.

As a Middle English writer who was successfully ushered onto the print marketplace of the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, Chaucer’s case affords a unique vantage point on the changing understanding of literary authorship and its relation to anonymity, naming, and publication in the period. With the editions of his works produced in the sixteenth century, Chaucer’s literary authority was increasingly seen to reside in his name, his works, and eventually his person. While the poet and courtier Stephen Hawes affirmed near the beginning of the century that Chaucer’s ‘goodly name / In prynted bookes, doth remayne in fame’, this had not always been the case. Only with Wynkyn de Worde’s edition of 1498 did the Canterbury Tales receive its first title page, a feature absent from medieval English manuscripts. Where most fifteenth-century manuscripts and the first printed edition of the Tales had not mentioned Chaucer in their opening paratexts, de Worde’s 1498 title page proudly declares both author and title: ‘The boke of Chaucer named Caunterbury tales’.Footnote 19 By the late seventeenth century, Chaucer’s name and his works were common cultural currency in England, accessible not just in the most recent 1687 reprint of Speght’s editions or in those that had come before, but also in myriad imitations and adaptations. One of these, a Chaucer-inspired jestbook also published in 1687, was titled Canterbury Tales: composed for the Entertainment of All Ingenuous young Men and Maids and professed on its title page to be ‘By Chaucer Junior’.Footnote 20 Chaucer’s name, then, had come to be well known in early modern England and it was closely associated with his body of work, in particular with the Canterbury Tales, which had been given pride of place as the first text in every volume of his works since Thynne. As Machan puts it, the critical apparatus introduced by Speght, in particular, ‘solidifies the identification of the Works with a specific historical personage and thereby supports both the ideology of a canon and the mediation of literary history through exalted individual writers’.Footnote 21

The association between the name of an individuated author and a printed oeuvre belied a more complex textual reality, and one of which the early modern editors were keenly aware. Chaucer’s name may have become virtually inseparable from the marketing of his printed works but the oldest and most authoritative witnesses often lacked this ultimate sign of authority. Manuscripts of Chaucer’s works were usually produced for and by people who already knew the author’s identity, or to whom it did not matter; as Gillespie notes, in the context of medieval manuscript production ‘traditions of anonymity are evidence of things which did not need to be said’.Footnote 22 The immediate interests of patrons, compilers, and scribes of manuscript works typically trumped investment in the author’s name, and most of the earliest scribal copies of Chaucer’s works do not prominently declare their author. As Chaucer became a dominant cultural figurehead, these volumes without a named author posed new challenges for readers and editors alike. A comment made by Speght following his list of Chaucer’s ‘Bookes’ in 1598 underlines the difficulty presented by old copies: ‘Others I haue seene without any Authours name, which for the inuention I would verily iudge to be Chaucers, were it not that wordes and phrases carry not euery where Chaucers antiquitie’.Footnote 23 Lacking an authorial ascription, books had to be assessed for inclusion in the collected Workes according to other criteria – in this case, a sense of Chaucer’s style and the antiquity of his language. As Speght’s vacillation demonstrates, however, this was not always a straightforward matter for an editor, and a text ‘without any Authours name’ could be a source of doubt and confusion.

One of the foremost Chaucerians of the sixteenth century, John Stow, took some of this work of attribution upon himself. Surviving medieval manuscripts that passed through Stow’s hands reveal traces of the shift towards Chaucer’s increasing prominence in the period, and Stow’s own contribution to that shift. It is difficult to overstate Stow’s role in promoting the study of medieval England and its literature. Gillespie pegs him as ‘easily the most prolific writer of history of the Tudor age and … the most widely read’, while William Ringler long ago voiced the necessity for a checklist of Stow’s literary manuscripts, along with an analysis of his marginalia and commentary on poetry and poets.Footnote 24 Stow was an avid scholar and bibliophile with sustained interests in medieval literature and history; his work unearthing, collecting, copying, preserving, and interpreting antiquities has in recent decades brought him to greater scholarly attention and seen him credited with no less an achievement than the ‘making of the English past’.Footnote 25 Despite his undeniable place at the centre of medieval manuscript study in the period, Stow’s readerly engagement with his books has been construed as something of an intractable problem. Edwards has characterised Stow’s marginalia as ‘seemingly cryptic’ and has confessed that it is ‘not at all easy to determine what features of a work he felt to be significant’, while the editor of the Fairfax manuscript containing Stow’s annotations (to be discussed) concludes that ‘From the disconnectedness of [Stow’s] entries it is not possible to say how he used the manuscript’, beyond a general interest in certain texts over others.Footnote 26 But more particular questions about Stow’s taste in medieval literature remain unanswered, in part because his interests skewed more heavily towards the historiographical and the local than towards concerns that might today be considered aesthetic or literary.

Stow’s commentary on medieval texts might also seem inscrutable because it is often preoccupied not with the ‘features of a work’ (as Edwards has it) but with the features surrounding a work. It is these features that I now wish to consider more closely. His notes show that he paid careful attention to paratextual devices such as names, titles, lists of contents, and other framing devices that lend context and authority to a given text. Edwards has observed the ‘largely attributional’ nature of Stow’s annotations in the Fairfax manuscript and in a similar vein, Gillespie has noted that ‘characteristic of his literary work is a prevailing concern with questions of authorship and canonicity’.Footnote 27 The present discussion assesses Stow’s annotations in medieval manuscripts through the lens of his editorial work. The attributional impulse on display in Stow’s notes in medieval manuscripts mirrors the emergent interest in early English authors found in contemporary printed books – and for some of which he was directly responsible. The fact of Stow’s involvement in the book trade as an editor and contributor to printed books as well as a ‘searcher’ and reader of manuscripts makes his engagement with Chaucer two-pronged.Footnote 28 In some of the cases outlined in what follows, it is impossible to determine whether Stow wholly conforms to the print-to-manuscript model of readerly perfecting, whether his interventions in the manuscripts originate in the results of his archival research into England’s medieval past, or whether both of those things are true and his notes in fact reflect his own discoveries as mediated through Speght. Whatever their origins, his surviving notes in medieval manuscripts constitute a record of Stow’s longstanding preoccupation with authors and their canons. Even if the relationship between their appearance in print and their parallel introduction into the manuscripts by Stow is not a causal one, his annotations express his desire to perfect fifteenth-century manuscripts according to some of the hallmarks of literary authority.

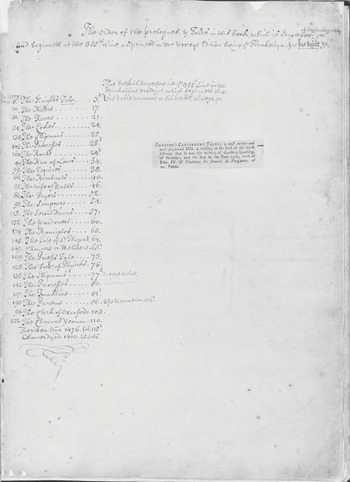

Bodl. MS Fairfax 16 is a miscellany including a large number of Chaucer’s lyrics, as well as works by Clanvowe, Lydgate, and Hoccleve, amongst others. Given his interests in Middle English and especially in the works of Chaucer and Lydgate, Stow’s interest in Fairfax is unsurprising and his engagement with the book is well documented.Footnote 29 However, his annotations have not been fully considered in the context of parallel advancements in the conception of authorship in the sixteenth century and the growing body of accepted knowledge about medieval poets and their oeuvres, in whose compilation Stow had a hand. At several places within Fairfax, Stow added marginal notes pairing authors’ names with works initially copied without attribution by the manuscript’s medieval copyist. In the list of contents, for example, Stow glossed several works with succinct notes about their matter and titles, and identified the respective authors of three works as Chaucer, Hoccleve, and Lydgate (see Figure 4.1).Footnote 30 In one sense, these belated additions bring the titles in line with others in the list of contents copied by the fifteenth-century Fairfax scribe, who had declared the Chaucerian origins of certain texts: ‘The goode councell of Chawcer’, ‘The sendyng of Chawcer to Scogan’, or ‘The complaynt of Chawcer to his purse’. In another respect, however, the alternative titles, authors’ names, and seeming trivia added into Fairfax reveal Stow’s abiding preoccupation with the most prominent figures of Middle English literary history. The most substantial and consequential addition of this type appears on fol. 130r, where the poem titled by its fifteenth-century scribe as ‘The booke of the Duchesse’ has been glossed with further information in a hand that is now generally regarded as Stow’s: ‘made by Geffrey Chawcyer at ye request of ye duck of lancastar: pitiously complaynynge the deathe of ye sayd dutchesse / blanche/’.Footnote 31 As if to validate this claim, the marginal gloss ‘blanche’ is also added in Stow’s hand at three points within the poem where the whiteness of the lover’s dead lady is recalled (ll. 905, 942, 948).Footnote 32 This trio of terse notes, in their provision of a layer of historical, biographical, and attributional context, is typical of Stow’s marginalia. The antiquary’s particular interest in the circumstances around the composition of the Book of the Duchess is confirmed elsewhere, in a copy of Stow’s 1561 Workes which Dane and Gillespie posit once belonged to the editor himself. Inside this copy, Stow’s hand has supplied a note which again shows a concern with the occasion of the poem’s composition: ‘This booke was made of ye death of Blanch Duches of Lancaster’.Footnote 33 This persistent pattern affirms Stow’s interest in detailing the origins and patronage of the Book of the Duchess within an aristocratic circle frequented by Chaucer.

Figure 4.1 Table of contents and accompanying notes by John Stow.

In book historical terms, these additions made by Stow indicate that he saw both the older 1561 edition and the manuscript as deserving further explication of the poem’s patronage and, specifically, Chaucer’s connection to the House of Lancaster.Footnote 34 For Stow, these were facts that merited publication alongside the text. The widely accepted modern view that Chaucer wrote the Book of the Duchess ‘at ye request of ye duck of lancastar’ has its genesis in Stow’s note to that effect in Fairfax, and in the corresponding argument on the allegory in Speght’s 1598 edition: ‘By the person of a mourning knight sitting vnder an Oke, is ment Iohn of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, greatly lamenting the death of Blaunch the Duchesse, who was his first wife’.Footnote 35 In all likelihood, this identification may be based on material supplied to Speght by Stow himself, who characterised that edition as ‘beautified with noates, by me collected out of diuers Recordes and Monumentes, which I deliuered to my louing friende Thomas Speight’.Footnote 36 Stow’s handwritten notes on the Book of the Duchess have been identified as ‘the sole authority’ for the poem’s Lancastrian connections,Footnote 37 but the exact date at which Stow encountered Fairfax is uncertain, and there are several suggestions that he came across it around the year 1600,Footnote 38 towards the end of his long life, and at a time when he was still clearly occupied with questions pertaining to Chaucer’s life and works. If Fairfax came into Stow’s hands around 1600, as seems most likely, then his comments post-date Speght’s argument to the poem in 1598, and that edition’s assertion about the identity of the ‘mourning knight sitting vnder an Oke’ assumes priority. This sequence of events would recontextualise Stow’s marginalia in Fairfax as having been influenced by Speght (or even by research he undertook on behalf of Speght, who went on to publish it). Whatever the order of this chain of events, it attests to the early modern circulation of certain details of Chaucerian biography in a variety of media – not only in printed books and older literary manuscripts, but also in the historical ‘Recordes and Monuments’ examined by Stow and in the ‘noates’ based on them which he delivered to Speght.

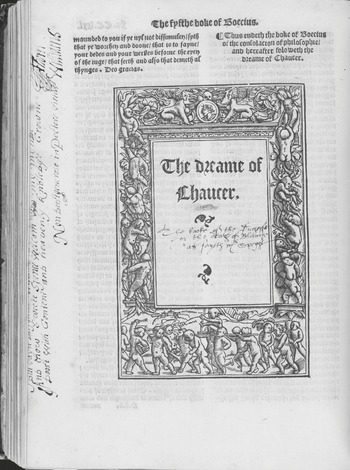

Stow’s notes on the Book of the Duchess in Fairfax thus echo, or at the very least mirror, concurrent and consequential claims about the text which were being made in print, and for whose discovery he may have been responsible. The simultaneous attachment of this information about Blanche to printed and manuscript versions of the text speaks to a broader contemporary interest in the details of Chaucer’s life and career. That desire to know the author was one which was fuelled and, in large part, even ignited by Speght’s elaborately annotated edition. Stow’s annotations in Fairfax and in his own 1561 copy of the Workes convey the extent to which the editions published under Speght’s name advanced a new model for literary authority in print and transformed the idea of the Chaucerian book. More so than any prior edition, these prints presented Chaucer’s texts inside a dense paratextual frame which intertwined biographical, literary, and historical forms of authority. After Speght’s edition supplied new knowledge about Chaucer’s life and his canon, old books of the poet’s works might, by comparison, be viewed as lacking this crucial layer of authority. The extent to which Speght’s editions shaped readerly expectations and knowledge about Chaucer and his works is demonstrated by another piece of marginalia in a copy of Thynne’s 1532 edition now held in Glasgow. Inside the woodcut frame used as an inset title page for ‘The dreame of Chaucer’ – that is, the Book of the Duchess – a contemporary hand has added the poem’s alternative titles: ‘Or The booke of Duchesse or the death of Blanche as sayeth Mr Speght’ (see Figure 4.2).Footnote 39 Here is a later reader who, in light of reading Speght, noticed the older book’s lack of up-to-date information about the poem’s title and occasion and decided to supply them. In that effort to note Chaucer’s aristocratic subject matter and the exalted patron who stood behind the work, this annotator meshes the personal with the public and the poetic. Like the contextualising headnotes about Chaucer inscribed by John Shirley into fifteenth-century manuscripts, this biographical snippet supplied by Speght and transcribed by an early modern reader seeks ‘to personalize and historicize the act of writing and reveal the living maker behind the poet’.Footnote 40 Much had been made of Chaucer’s relation by marriage to John of Gaunt in the genealogical portrait and Life of Speght’s edition.Footnote 41 In all likelihood, that information gleaned from Speght about Chaucer’s powerful patron and eventual brother-in-law was also at the forefront of the annotator’s mind when they noted the poem’s connection to the Duchess.Footnote 42 In this sense, it is as much a note about the life of Chaucer as it is about ‘the death of Blanche’. It is striking that both Stow and the Glasgow annotator updated older books according to newly available knowledge about the Book of the Duchess and the circumstances of its composition. Their annotations demonstrate the crucial and highly valued context for reading Chaucer’s works supplied by Speght’s new edition. They enable us, moreover, to pinpoint those facets of Chaucer’s biography which early modern readers deemed most pertinent.

Stow is best known as a collector of manuscripts but he also collected printed books, and much of his scholarly energy was spent producing work for the press.Footnote 43 Just as his lifetime bridges the periods traditionally designated in English history as ‘medieval’ and ‘early modern’, so too his work ranged across the parallel worlds of manuscript and print.Footnote 44 Stow thus emerges as a figure invested in print as a vehicle for promoting medieval literature, and via whom the stream of information from older, handwritten books, into updated transcriptions, and even into print may occasionally be traced.Footnote 45 In many of these efforts, too, Stow’s organisational principle was the figure of the author.

His first certain publication, the 1561 edition of Chaucer, was the expanded sequel to Thynne’s folio Workes, a book which in 1532 had rewritten the rules of the literary prestige normally accorded to English authors. He was probably also responsible for editing a reprint of the prose Serpent of Division (1559), which appears in a manuscript he once owned and which he believed to be by Lydgate.Footnote 46 In a revised dedication to his Summary (1567), Stow asks for patron Robert Dudley’s support so that ‘I shall be encouraged to perfecte that labour that I haue begon, and such worthye workes of auncyent Aucthours that I haue wyth greate peynes gathered together, and, partly yet performed in M. Chaucer & other I shal be much incensed by your gentlenes to publyshe, to the commodity of all the Quenes maiesties louynge Subiectes’.Footnote 47 As Stow relates it, his Chaucer folio was only the beginning. His stated intention to continue to ‘publyshe’ the ‘worthye workes of auncyent Aucthours’ affirms that his scholarship was undertaken for the purpose of public dissemination, and that the promotion of medieval authors was a driving motivation for him. Stow would go on to publish an edition of Skelton’s Pithy Pleasaunt and Profitable Workes (1568) and, as was noted, contributed materials on Chaucer and Lydgate to Speght’s Chaucer (1598). These supplements include an extensive list which follows the Siege of Thebes in Speght and is titled the ‘Catalogue of translations and Poeticall deuises, in English mitre or verse, done by John Lidgate Monke of Bury, whereof some are extant in Print, the residue in the custodie of him that first caused this Siege of Thebes to be added to these works of G. Chaucer’ – that is, Stow himself.Footnote 48

The sixteenth century in England saw an unprecedented awareness of vernacular authorship, one promoted by Stow’s editions of Lydgate, Chaucer, and Skelton. Seen in this context, Stow’s attributional annotations, with their imposition of authorial names and titles, reflect the work in progress of an editorially-minded reader, and they offer a glimpse into the antiquary’s motivation as he studied and compiled the materials that would make up future printed volumes of ‘worthye workes of auncyent Aucthours’.Footnote 49 Stow’s discreet attributional annotations in books like Fairfax show him relying on manuscripts for his research, even as he reckoned with their limitations and tellingly, as he updated them by superimposing authors’ names and titles of their works. His annotations provide a small but perceptible trace of the shift as it happened – a change whereby manuscript books from the previous century could be retrofitted with paratextual markers such as attributions, titles, and biographical snatches, all hallmarks of the growing recognition accorded to the author in the English book trade.

I have already suggested that Stow’s Book of the Duchess annotations appear synchronised with the printed editions of Speght in circulation at the time. Another instance of likely influence from print to manuscript, in which Stow’s addition to the Fairfax manuscript runs in parallel with his editorial choice in print, is his addition of a gloss ‘the blacke knight’ to the Lydgate poem listed as ‘The complaynt of a lovers lyve’ (IMEV 1507) on the manuscript’s contents page. The poem likewise appears in the editions of Speght and Stow himself as ‘The complainte of the blacke knight, otherwise called the complaint of a louers life’.Footnote 50 No surviving manuscript of this poem contains both titles paired as Stow presents them in his edition and in Fairfax. Here too, Stow’s scrupulous attention to the makeup of a medieval author’s canon, and the way that his gloss echoes a print authority, is emblematic of an emerging cultural interest in the authenticity and canonicity of particular works.Footnote 51 Similarly, the emphasis on authorship in the printed editions is echoed by Stow’s marginal addition to the Fairfax poem which is titled ‘A devoute balette to oure lady’ in the manuscript, and which he glossed as ‘A.B.C. per Chaucer’ (fol. 2r) and elsewhere as ‘Chawcers A.b.c.’ (fol. 188v), a new title that may likewise have been influenced by Speght’s printed edition, in which the work is named ‘Chaucers A.B.C., called La Priere de Nostre Dame’.Footnote 52 Stow’s habit of titular correction is evident elsewhere in Fairfax too – for example, in his correcting of the title ‘the temple of Bras’ to ‘glas’ at the beginning and end of Lydgate’s poem (fols. 63r, 82v), or in his addition of a title to Chaucer’s Compleynt unto Pite (IMEV 2756), where its original scribe had titled it simply ‘Balade’.Footnote 53 Stow’s annotations in Fairfax are scattered and generally sparse, rather than methodical, but his interest in correctly attributing and titling works in medieval manuscripts is sustained across numerous volumes.

In a predominantly Lydgatean manuscript miscellany which dates from the late fifteenth century (BL, Additional MS 34360), for instance, Stow made a note correctly assigning to Chaucer the poem now known as Complaint to his Purse (IMEV 3787), an attribution supported in some manuscripts (including Fairfax) as well as the folio editions of the Workes before 1602, where the poet is named in the title as the speaker.Footnote 54 Elsewhere in the Additional manuscript, Stow assigned to ‘Chauser’ the apocryphal poem that he called ‘La semble des dames’ (fol. 37r, IMEV 1528), perhaps following the poem’s French title in TCC, MS R.3.19.Footnote 55 In the same manuscript, Stow also added the attribution ‘The horse the shepe and the Gose, by John Lydgate’ to that work (IMEV 658, fol. 27r), and supplied a title to the work he there called ‘The crafte of love’ (IMEV 3761, fol. 73v). It received a more elaborate description in his 1561 edition, where it appeared under a heading ‘This werke folowinge was compiled by Chaucer and is caled the craft of louers’. In TCC, MS R.3.19, which Stow is known to have used as a source for much of the new material he appended to his Chaucer edition, he likewise added a note ‘The Crafte of lovers Chaucer’ at the poem’s head (fol. 154v).Footnote 56 At the conclusion of this text he also added a biographical note about Chaucer, ‘Chaucer died 1400’,Footnote 57 a response in the margins to the narrator’s assertion that he heard this dialogue ‘In the yere of oure lord a Ml. by rekenyng / CCCC xl. &. viii’. Stow, taking issue with an internal date that post-dated Chaucer’s lifetime, emended this to ‘1348’ in his 1561 edition.Footnote 58

Both Stow’s surviving medieval manuscripts and the annotations in these volumes thus demonstrate his abiding interest in historiography and in the literature of late medieval England. Studied in isolation, his marginal notes may seem trifling or reactive. However, they are collectively underwritten by an attributional and biographical impulse directed towards Chaucer and Lydgate, Hoccleve and Gower, as well as towards figures such as Blanche of Lancaster, Gildas, William de la Pole, and other historical personages.Footnote 59 His literary attributions witness a highly developed awareness of the canon and authors of Middle English literature – a canon which he aspired to shape.Footnote 60 Such an observation is not new, but the degree to which Stow’s notes anticipate, echo, or otherwise correspond to print has not been fully appreciated. The nature of his annotations on The Book of the Duchess, The Complaint of the Black Knight, Chaucer’s ABC, and The Craft of Lovers in fifteenth-century manuscripts all match framings of these texts in his or other printed versions, and they provide direct evidence for the increasing prominence afforded to authorial figures and their canons in late Elizabethan England.

Stow’s manuscript annotations reflect editorial habits of identification, comparison, and correction which persisted far beyond his editing of Chaucer for the press in 1561. They show that he maintained an editorial and readerly sensibility which sought to ascribe authorial agency and to circumscribe literary canons. In his reassigning of the names attached to particular texts in manuscript, Stow attempted to impose new order onto these old books, to map the terrain of Chaucer’s oeuvre and, in so doing, to shed new light on the author’s life. As Gillespie has shown, preoccupations with the figure of the medieval author may be gleaned from the ways manuscripts and printed books were organised, produced, and received by their makers and early readers; in the case of Stow and his fellow antiquaries, ‘the medieval author had become a stable place for the remnants – whether old manuscripts or the learned texts in them – of a vanishing medieval past’.Footnote 61 But it was not enough to search and collect old manuscript books. Stow also needed to make sense of them by updating, annotating, and situating their texts historically – for example, by correcting a faulty date, setting the record straight about their proper titles, or providing vital context about their composition. Stow was a reader of old books and a maker of new ones, and his marginalia in Fairfax and other medieval manuscripts record the evolution of a suite of ideas about Middle English authorship. Whether updating manuscript texts to bring them into line with information conveyed in print, or to classify and perfect them with an eye to print publication, Stow’s marginalia in medieval books expose some of their perceived limitations in the face of emerging standards of bibliographic authority. The frequent lack of authorial attribution, uniform titles, or relevant historical detail in medieval manuscripts were all shortcomings which Stow sought to redress through the research and editorial work that would ultimately define an early modern canon for Chaucer (and equally for Lydgate).

Stow was extraordinary in his diligent scouring of ancient volumes, but he was not unique in his aim to impose a new order onto old manuscript books. Other readers, too, compared fifteenth-century manuscript volumes with the more recent printed collections, and left notes to suggest that they, like Stow, appraised the older books according to new standards of authority and canonicity as they read.Footnote 62 In BL, Additional MS 34360 an early modern hand which may be that of the poet William Browne of Tavistock has furnished a table of contents listing ‘A Catalogue of the Poems in this Volume’ (fol. 3r).Footnote 63 The second item in the list, Chaucer’s Complaint to his Purse, receives an extended entry:

Browne also noted the discrepancy in attribution beside the scribally copied text itself (fol. 19r).Footnote 64 The later poet’s interest in Hoccleve’s purported authorship of Purse (a curious assignation made in Speght’s second edition) manifests his particular preoccupation with collecting and elevating the works of the Privy Seal clerk.Footnote 65 That Browne twice took pains to cross-reference the older book with the more recent Hoccleve ascription found in the newer print reflects his attempts to weigh up and reconcile the competing author attributions he observed across the two volumes. For Browne, a would-be editor of Hoccleve, Speght’s choice in assigning the poem would have furnished compelling proof of the clerk’s historical importance.

Durham University Library, Cosin MS V.11.14 is a fifteenth-century manuscript containing Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes alongside shorter Middle English works including Benedict Burgh’s Magnus Cato and Parvus Cato, and the anonymous Life of St Alexius.Footnote 66 Notes written in this book by the clergyman and collector George Davenport (d. 1677) similarly show him wondering where Chaucer’s oeuvre ended and that of his followers began.Footnote 67 Like Browne, Davenport attempted to establish these boundaries using information gathered from printed editions. On fol. iiir, Davenport wrote a heading under which he assigned not only the Siege, but all the manuscript’s major works, to Lydgate: ‘In this volume are contained these books of Lidgate’. Davenport’s table of contents fulfilled the practical aim of identifying the volume’s matter and aiding navigation. It also erroneously named ‘Lidgate’ as the author of all the titles in the list, while another hand later cross-referenced the table against ‘Stow’s list’ of Lydgate’s works in Speght’s edition.Footnote 68 On the verso of the same leaf, Davenport supplied three lines of Lydgate biography collected from John Pits’s 1619 Latin life of the poet.Footnote 69 Underneath it he added a further note referring specifically to the Siege of Thebes: ‘This book is printed at the end of Chaucers works’.Footnote 70 Such notes reveal the print contexts that ineluctably shaped the experience of reading Chaucer and Lydgate in early modern England, and make explicit the constant reckoning which readers like Davenport and Browne performed when they opened their medieval manuscripts. In imagining his volume as a collection of several ‘books of Lidgate’, Davenport superimposed a new (albeit misjudged) author-centric order upon the miscellaneous manuscript. Attribution thus proved to be a thorny matter in print as well as in manuscript. The assurance of authorial stability which Davenport constructed around ‘Lidgate’ in the Durham manuscript quickly crumbles with the realisation that several of these texts are not Lydgatean. In Additional, Browne likewise embraced the reassigning of Complaint to his Purse to Hoccleve in ‘Chaucers printed workes’. But many early attributions, whether implied or explicit, stood on precarious foundations within the manuscript record. Speght had hinted at the issue when he invoked the problem of manuscript books ‘without any Authours name’ (which he singled out from ‘those bookes of his which wee haue in print’); that is, he too worried about the authorship of anonymous manuscript works which bore no attribution.Footnote 71 Working out genuine Chaucerian works from those that might only resemble them was not straightforward, but a matter Speght realised one must ‘iudge’. Both Browne’s and Davenport’s comments, as well as Speght’s quibble about those texts ‘without any Authours name’, signal the emergence of a readership concerned with accuracy of attribution, and who looked to print to supply it.Footnote 72 The promotion of a literary corpus went hand in hand with celebration of the author responsible for its creation. What had been true in Chaucer’s and Lydgate’s own time still held in the era of their print prominence; in Gillespie’s words, ‘Works must be listed and their authorship declared if writers are to hold onto their place in literary history’.Footnote 73 In their promotion of the individuated author and the circumscribed canon, the volumes produced by the early modern book trade engendered a powerful readerly desire to reproduce these paratextual trappings in order to authorise older books which lacked them.

The weighty influence of print on early modern conceptions of Chaucer and his canon may also be gleaned from Bodl. MS Tanner 346, a manuscript anthology copied on parchment and dated to the second quarter of the fifteenth century.Footnote 74 The Tanner manuscript contains works by Hoccleve, Lydgate, and Clanvowe, and also reflects an early attempt to collect Chaucer’s minor poems. In the late seventeenth century, Tanner was owned by the collector and Archbishop of Canterbury William Sancroft (d. 1693), who amassed a personal library of at least 7,000 volumes, most of which were printed books which he bequeathed to Emmanuel College, Cambridge. The majority of his manuscript collection, however, was sold to Thomas Tanner and subsequently entered the Bodleian Library.Footnote 75 Tanner 346 was amongst these volumes, and still bears evidence of Sancroft’s engagement with the poet and his works. The date at which the Archbishop acquired the manuscript is not known, but he marked his ownership by inscribing his name, ‘W: Sancroft’, on the recto of its first leaf (fol. 1r), at the beginning of the Legend of Good Women. When Sancroft owned this manuscript, it was around two hundred years old and carried the signs of its long life. Most noticeable, perhaps, were the badly faded words and letterforms on fol. 1r, which either Sancroft or a reader contemporary to him traced over with black ink and in a cursive secretary hand.Footnote 76 Despite these markers of the book’s age, the fifteenth-century hands of the Tanner scribes, who wrote in a distinctive ‘amalgam of Anglicana Formata and Secretary’ and in a secretary hand typical for the date, appear to have been sufficiently legible to the Archbishop.Footnote 77

Although there is no direct evidence that Sancroft read the text closely, it is clear that he paid sustained attention to the nature and arrangement of the book’s contents. He added to the Tanner manuscript a paper leaf with the heading ‘Some of Chaucer’s Works’, on which he listed all of the volume’s texts by title and keyed them to page numbers in the manuscript (see Figure 4.3).Footnote 78 The ambiguous heading chosen by Sancroft for his table of contents is worth pausing over. It may indicate that Sancroft believed all of the manuscript’s contents to be Chaucer’s, or alternatively (if more improbably), that just ‘some’ of those listed were his. It has been observed by Robinson and others that the titles Sancroft assigned to the Tanner texts match those in Thynne’s edition.Footnote 79 If (as seems likely) Sancroft turned to Thynne or a later sixteenth- or seventeenth-century Chaucer folio to identify the contents of his manuscript, he would have found works such as The Letter of Cupid (IMEV 828), The Complaint of the Black Knight (IMEV 1507), The Temple of Glass (IMEV 851), and The Cuckoo and the Nightingale (IMEV 3361) assigned not to Hoccleve, Lydgate, or Clanvowe as they generally are today, but clustered without attribution alongside Chaucer’s most famous works. As Forni has argued, the version of Chaucer readers encountered in the editions of Thynne and his successors was ‘fundamentally different from the earlier manifestations of Chaucer’s canon by virtue of the technology of print’. Print, she contends, aimed to present a ‘fixed, identifiable, and duplicable body of works’ for the poet.Footnote 80 Annotations like those of Sancroft show what early modern readers made of those ‘fundamentally different’ manuscripts in the face of the definitiveness promised by print.

Sancroft’s consultation of Thynne (or a later edition) in parallel with Tanner accounts for his conviction that nearly all the works in the manuscript were ‘Chaucer’s Works’ (emphasis added). Sancroft’s conception of the ‘Works’ is itself indebted to a presentation of Chaucer which was particular to print, for it was in Thynne’s 1532 edition that this distinction – to be the author of ‘works’ alongside Virgil or Homer – was first awarded to anyone who wrote in English.Footnote 81 While this was not a term used by the compilers of this or any other Chaucerian manuscript, it was one which Sancroft thought appropriate for such a manuscript by the late seventeenth century. Simultaneously, his use of ‘some’ conveys a perception of the manuscript’s incompleteness in relation to the more expansive Chaucer canon which he had encountered in a printed volume. Both halves of Sancroft’s formulation ‘Some of Chaucer’s Works’ therefore owe something to a version of the canon which circulated widely in print.

Sancroft’s method of improving this manuscript by superimposing a new order in the form of titles adopted from print may be usefully contextualised by his dealings with other medieval books and by the makeup of Tanner itself. During his archiepiscopal tenure, he is known to have overseen the colossal task of disbinding, combining, and reordering the medieval manuscripts in the library at Lambeth Palace.Footnote 82 Ker surmises that one of Sancroft’s aims in this work was organisational: ‘to eliminate the thinner volumes by binding them up with one another, and to make homogeneous volumes by moving pieces from one volume to another, so that like came to be with like’.Footnote 83 The newly reconfigured volumes were listed in a catalogue prepared by Sancroft himself, and he recorded the contents of these manuscripts on their flyleaves.Footnote 84 The same urge towards ordering the book is evident in the creation of the Tanner contents list. In this case, Sancroft recognised the volume’s Chaucerian content and went so far as to redefine it in terms of ‘Chaucer’s Works’. At the same time, Sancroft’s annotations register his response to Tanner’s particularities. As Robinson has noted, the palaeographical and codicological evidence in Tanner suggests a ‘lack of coordination among the scribes’, ‘that each was working independently of the others’, but ‘no evidence that anyone assumed over-all responsibility for the volume’.Footnote 85 She singles out the patchy provision of headings in the manuscript as symptomatic of this lack of overall coherence; only three of the book’s fourteen items were assigned headings by the scribes.Footnote 86 Given this inconsistency in the manuscript’s ordinatio, Sancroft’s provision of a table of contents and individual titles in Tanner may reflect his intention to lend order to books in which he believed organisation was lacking.

Tables of contents were by no means particular to print.Footnote 87 However, they are generally rare in Middle English vernacular manuscripts, and there is evidence of both medieval and later book users having supplied them in order to enhance the navigability of such codices.Footnote 88 Sancroft, a seventeenth-century reader, belongs to this latter group but what makes him noteworthy in the present context is his use of a print authority to assign titles to works and to compose a table of contents for a medieval manuscript. A reader lacking a comparison copy might have generated titles from their own reading, but Sancroft’s reliance on titles found in Thynne suggests the appeal of print’s seeming standardisation to an early modern reader and its role in his appraisal of the manuscript’s quality. His replication in Tanner of the printed titles furnishes direct evidence of an edition’s influence on the early modern conception and framing of Chaucer’s works, and demonstrates the authority that readers attached to the paratextual presentation of his texts in print. For Sancroft, the printed table was the benchmark by which he organised his manuscript, and the printed book served as the definitive record of Chaucer’s authorship and canon by extension.

As we have seen, the secure attribution implied by their inclusion and arrangement in the Workes was, for texts such as Complaint to his Purse, a fiction. The stability of the titles attached to particular texts in those volumes was equally attractive, but just as illusory. Forni’s research into the dubious basis on which certain titles were assigned to items in the Workes in manuscript and early print has exposed the ‘shifting titles, attributions, and texts’ which are ‘often the product of oversight and carelessness but sometimes simply the result of confusion’.Footnote 89 In one instance, Sancroft’s practice of titling exemplifies the trail of confusion engendered by the vagaries of early editorial choices. In a meticulously documented essay, Forni shows that the poem now called The Isle of Ladies was once called Chaucer’s Dreame, which caused it to be conflated with the Book of the Duchess, which was titled The Dreame of Chaucer from Thynne onward. The muddling of these two works in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century print undoubtedly account for Sancroft having titled the Book of the Duchess as ‘Chaucer’s Dreame’ in Tanner.Footnote 90 Such shifts and discrepancies from one edition to the next shatter any assumption of print’s stability in relation to manuscript; on the contrary, they emphasise that the absence or inconsistency of titles and attributions in medieval manuscript witnesses had longstanding repercussions for the transmission of such works in print, and that the early editors introduced their share of perplexing variants into a canon with an already complicated textual history.

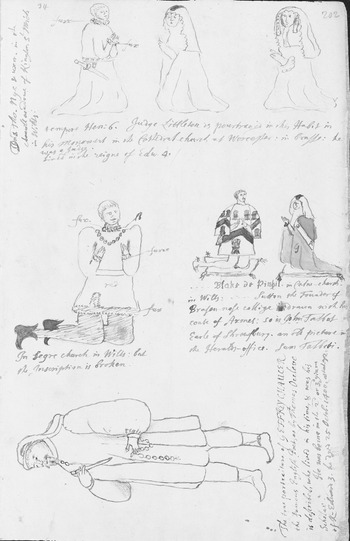

While readers such as Sancroft could be led astray by printed accounts of the makeup of Chaucer’s canon, the discernment of some readers in the face of competing and superseded print authorities should not be underestimated. The Glasgow manuscript of the Canterbury Tales (Gl, previously discussed in relation to its unusually large number of scribal gaps) was later owned by the Norfolk collector and antiquary Thomas Martin (1697–1771), who signed his name in the book and professed it was ‘Given me Mr John White of Ipswich Surgeon’.Footnote 91 Martin’s hand, which is markedly larger and more embellished than the annotator who filled in the gaps, features prominently not inside the book itself but on a supplementary paper flyleaf (see Figure 4.4). Here, Martin has drawn up a table headed ‘The order of the prologues, & Tales, in this book, (which is Imperfect,) at beginning only. / And beginneth at the 355th Line, as printed in Mr Urrey’s Edition being the Frankelyn &c his table &c’.Footnote 92 During this comparative exercise, Martin observed some of manuscript’s more eccentric features, such as the scribes’ splicing of two copytexts which, remarkably, caused two tales to be duplicated or ‘Enter’d twice’ in this copy, as Martin notes in his list of contents.Footnote 93 A committed scholar of Chaucer, Martin also owned copies of Thynne’s 1542 and Stow’s 1561 editions,Footnote 94 but it was Urry’s much disparaged 1721 edition that he trusted to make his collations with the manuscript.Footnote 95 Martin’s engagement with Chaucer thus involved both reading the printed text and evaluating the manuscript book itself. His attention to tale order in the manuscript, his identification of the copying error made by the Spirlengs, and his precise identification of the missing opening lines which made the manuscript ‘Imperfect’ all show the influence of his having read Chaucer in print. Despite his awareness of the manuscript’s textual shortcomings, his appreciation of its age is suggested by his notes beneath the contents list, which observe that the manuscript was ‘Written anno 1470’ and that ‘Chaucer dyed .1400. 25 October’. These facts anchor the manuscript within a sequence of historical time whose starting point is the end of the author’s lifetime. For Martin, assessing the book’s authority involved declaring its proximity to (or distance from) a time when Chaucer himself had lived.

The forms of paratextual authority supplied in medieval manuscripts by Martin, Sancroft, Davenport, and other readers – attributions, tables of contents, titles of works, and even biographical details – overlap in their fundamental focus on authorship and canonicity. The annotations described here witness not only a burgeoning early modern interest in the print-published medieval author, but also demonstrate readers’ use of print to situate medieval manuscripts and their texts within a larger, author-centric literary history. Just as printed editions attempted to furnish standardised titles, to create canons in the form of tables of contents, and to name their authors, Stow and other readers with similar interests in literary history were doing the same for the manuscripts that came into their hands. This phenomenon of inverted textual transmission from print to manuscript, and from new books to old ones, has been described in a comment by Forni: ‘commercial titles and attributions are later added to manuscripts and appear to establish authority for the print attributions from which they were derived’.Footnote 96 Such an assessment demonstrates some of the tenuous textual foundations on which Chaucer’s canon was first built. This evidence confirms the widespread role of early modern printed volumes in shaping the bibliographic expectations which readers brought to medieval manuscripts, and print’s contribution to the continued currency of the older books. This chapter has so far been concerned with the relatively small and discreet paratexts which readers often adapted from print and applied to manuscripts with the aim of lending them greater authority. But alongside these relatively inconspicuous signs of print’s influence were bolder, more striking additions made to old books by readers who shared the goal of authorising their Chaucers.

4.3 ‘True Portraiture’

Arguably, the most arresting feature of the early modern editions – and their most visible marker of authorial presence – was a genealogical portrait of Chaucer (see Figure 4.5). In order to understand the uses to which readers put the portrait, its role as an authorising paratext should first be established. To those who first laid eyes on it, the intricate intaglio engraving made by John Speed would have been striking in its novelty. Speed’s copperplate Chaucer portrait, made for Speght’s first edition of the poet’s Workes (1598), was advertised prominently on that book’s title page, at the head of a list of the new edition’s vendible features: ‘His Portraiture and Progenie shewed’.Footnote 97 While woodcut images had held a monopoly in England until around 1545, the latter part of the century saw the immigration of talented metal engravers from the Continent and the growth of a market for specialist prints.Footnote 98 Images printed from cut woodblocks would remain ubiquitous in sixteenth-century England, in bound volumes, and in broadsides, chapbooks, and decorations pasted onto domestic interiors.Footnote 99 However, the newly fashionable form of metal plate engraving was ideally suited to transmitting minute, individualised details, and was especially sought for prints of maps and portraits. By the final decade of the sixteenth century, John Harington could still write of the brass-cut engravings in his translation of Orlando Furioso (1591) that ‘I haue not seene anie made in England better, nor (in deede) anie of this kinde, in any booke, except it were in a treatise’.Footnote 100 At the turn of the century, engravings were a desirable print commodity to the book-buying public, as much for their beauty as for their curiosity.

Figure 4.5 John Speed’s engraved Chaucer portrait in Speght’s first edition of the poet’s Workes (1598).

But it was not only its technological newness that made the printed Chaucer portrait remarkable in its own time. For all its novelty, Speed’s image is everywhere marked by iconographic and textual statements of Chaucer’s historical and cultural authority. The image is titled ‘The Progenie of Geffrey Chaucer’. That heading is a misleading one, however, for Chaucer is flanked here by a series of medallions which trace not only the names of his descendants, but also his links back to England’s noble and royal families via his marriage to Philippa Roet. It is her father, ‘Payne Roet Knight’, who appears atop the genealogy as its symbolic figurehead. The base of the image depicts the tomb of Thomas Chaucer and his wife, Maud Burghersh, in the parish church at Ewelme. Speed’s engraving of the tomb reproduces its twenty-four shields representing the family’s illustrious pedigree. In framing Chaucer, claimed here as the first and ‘famous’ national poet, this heraldic iconography celebrates incipient Englishness itself.

To this work, as to his magnum opus The History of Great Britaine under the Conquests of the Romans, Saxons, Danes, and Normans and its accompanying maps, The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine (1611–12), Speed brought the genealogist’s enthusiasm for order and the antiquary’s diligence.Footnote 101 His pains to endow the picture with credibility are evident on the printed page. The medallions that cluster authoritatively around the figure of Chaucer confer historicity, and visually sidestep the fact that all of the poet’s noble relations were acquired by marriage rather than by a distinguished lineage that was his own. The finely wrought depiction of the tomb is likewise presented as a faithful representation of the monument at St Mary’s Church in Ewelme, Oxfordshire. Elsewhere in the Workes, Speght writes of the portrait that ‘M. Spede … hath annexed thereto all such cotes of Armes, as any way concerne the Chaucers, as hee found them (travailing for that purpose) at Ewelme and at Wickham’.Footnote 102

Most telling, though, are Speght and Speed’s efforts to authorise the portrait by conveying the verisimilitude of Chaucer’s printed likeness itself. The central panel of Speed’s engraving features a full-length depiction of Chaucer, standing and holding a rosary.Footnote 103 An object that is perhaps a penner (pen-case) hangs from his neck, signifying his status as a man of letters, and connecting the text printed in Speght’s edition to its written manifestation as a product of Chaucer’s hand.Footnote 104 A panel of text positioned underneath the figure of Chaucer announces its provenance:

The caption is unambiguous in its staging of the image’s authenticity: this is a ‘true’ representation of Chaucer’s likeness, as reported by the poet and clerk Thomas Hoccleve, who knew him well. Speght confirms the image’s Hocclevean origins when he notes elsewhere in the edition that

Occleve for the love he bare to his maister, caused his picture to bee truly drawne in his booke De Regimine Principis, dedicated to Henry the fift: the which I have seene, and according to the which this in the beginning of this booke was done by M. Spede

The avowal that Speed used a Regement exemplar for his Chaucer engraving is unverified, and unverifiable based on the current evidence.Footnote 105 Despite this lack of direct material proof, I do not believe there is good reason to distrust the Hocclevean provenance claimed by Speght, who had the fastidious John Stow and, later, Francis Thynne looking over his shoulder as he produced the editions.Footnote 106

Most importantly, and whatever the model of the 1598 Chaucer engraving, it is clear that Speed and Speght had good reason to align their project with that of Hoccleve. In the Regement, a literary petition for the patronage of Prince Henry of Monmouth (and later Henry V) written in 1411, Hoccleve proves his close relationship with the now-dead Chaucer in pictorial form:

As David Carlson has suggested, Hoccleve supervised the production of presentation copies of the work and the success of his bid to Henry relied on the portrait’s ‘lyknesse’ to Chaucer.Footnote 108 Hoccleve’s desire is to make not simply an effigial mnemonic aid, but a realistic mimetic portrait of Chaucer’s ‘lyknesse’. There is novelty here since individualised faces were rarely employed in medieval portaiture when iconography or arms alone could identify a figure. Alongside a few continental examples, Chaucer is therefore regarded as one of the first European vernacular authors to have a portrait attested in copies of his works.Footnote 109 As a visual invocation of the poet’s near-forgotten likeness, the Harley image has been most frequently interpreted as an attempt to produce an authentic, individualised portrait of Chaucer.Footnote 110

In this context, Hoccleve’s manuscript image of Chaucer recollected ‘in sothfastnesse’ was the ideal exemplar for a new mode of depicting the poet’s ‘true portraiture’ in print. Where Hoccleve may have reasoned that close affiliation with and instruction under Chaucer would aid his plea for Henry’s patronage, Speed relies on the putative intimacy between Chaucer and the clerk to authorise his engraving. And the editor, too, assures the reader that the portrait appears in a book by ‘Chaucers Scoller’ Hoccleve, testifying to ‘hav[ing] seen’ it before. Speed and Speght thus vouch for the accuracy of their representation of the Chaucerian ‘cotes of Armes’ and portrait respectively; like that of Hoccleve, these claims are supported by eyewitness accounts that serve as authenticating credentials for the artefacts they describe. In its printed incarnation, the image echoes Hoccleve’s pledge of the portrait’s authenticity – and deftly manages to appropriate it. The antiquaries’ claim that the printed image is Chaucer’s ‘true portraiture’ is conveniently tethered to the authority of Hoccleve and his book, even as it ventures forth in the fashionable form of metal engraving. In its ability to pivot between exploiting its novelty and its antiquity, the image recalls the polychronicity theorised by Gil Harris as a feature of early modern matter. ‘English Renaissance writers’ (including Stow), he observes, ‘repeatedly recognize the polychronic dimensions of matter – the many shaping hands, artisanal and textual, that introduce into it multiple traces of different times, rendering the supposedly singular thing plural, both physically and temporally’.Footnote 111 The Chaucer portrait – simultaneously medieval and early modern, hand-drawn and graven, the work of both Hoccleve and Speed – is rendered doubly authoritative by this polychronicity.

As it appeared in 1598 (and in the later edition of 1602 and its 1687 reprint), Speed’s portrait of Chaucer was a printed surrogate of a manuscript original – a representation of another, older image that was itself ultimately a ‘remembraunce’ of Chaucer the man. With each new iteration of his likeness, the poet receded further from both historical view and living memory, but those who reproduced it took care to transfer its authenticating hallmarks and to emphasise their contribution to its continued transmission. This narrative is a familiar one in studies of Chaucer’s reception, and one that has already been treated in this book’s attention to early modern narratives around the comprehensibility and accuracy of his language and the completeness of his canon. As James Simpson has argued, Chaucer’s perceived absence provides the linchpin upon which turned the machinery of his early modern prominence, as the dead poet’s corpus was recast as a textual monument to be recovered through archaeological and philological work.Footnote 112 What was true for the early philological investigations into Chaucer’s works and his books also applied to his first engraved portrait, as the recuperation of his physical likeness became a worthwhile antiquarian mission akin to the unearthing and assembly of his Life.Footnote 113

The 1598 likeness of Chaucer is an early and influential example of the engraved author portrait in an English book.Footnote 114 In this period, published works of poetry and prose were unlikely to contain portraits of their authors.Footnote 115 The portraits of most contemporary poets living and writing at the time, including John Donne, Edmund Spenser, and Sir Philip Sidney, would reach print much later – and posthumously.Footnote 116 Before the 1630s, in fact, most poets would only receive a portrait in print if they were dead, a trend which Leah Marcus reads as motivated by an impulse to ‘preserve the illusion of human presence within a medium that was vastly expanding the physical distance between writers and prospective readers’.Footnote 117 For long-dead auctores like Chaucer and Homer, whose works predated print itself, that gulf was wider still. In such cases, the presence conjured by a portrait served to recall, rather than to bridge, the temporal chasm between author and reader and made way for the author’s philological recovery in print. Accordingly, some of the earliest English books to contain printed author portraits are translations: Harington’s Ariosto (1591), Florio’s Montaigne (1613), and Chapman’s Homer (1616).Footnote 118 These books bear portraits of their contemporary translators instead of (or in the case of Homer, in addition to) images of their original authors. The translator portrait is a reminder of reading as a mediated experience, and one made possible by the translator’s efforts. Although the Workes was not a translation, Speght is implicitly framed as an ‘interpretour’ akin to contemporary translators of classical poets and of du Bartas, Petrarch, and Ariosto, by virtue of the editor having ‘made old words, which were unknown of many, / So plaine, that now they may be known of any’.Footnote 119 The visual rhetoric of Speed’s Chaucer portrait, like that of contemporary translations, thereby reinscribes a sense of the work’s inaccessibility, save for the editor’s or translator’s intervention. The stylised portrait could confer a formality befitting its distant subject and foreground the labours of those responsible for its recovery – in this case, Hoccleve, Speed, and Speght. In these early years of the market for engraved portraits, Chaucer was the ideal subject and Speght’s edition was a suitable medium for its transmission.

In printed form, Speed’s Chaucer portrait vastly exceeded the reach initially anticipated by Hoccleve when he commissioned multiple manuscripts containing the poet’s likeness. With this wider distribution and the ability to achieve new levels of realism in portraiture, Speed’s engraved portrait could eventually unseat Hoccleve’s as the definitive representation of how Chaucer looked. In its claim of a Hocclevean provenance, the printed image also takes on the authority of the older manuscript tradition, and it summons the hallmarks of manuscript authenticity – what Siân Echard has called ‘the mark of the medieval’ – to do so.Footnote 120 As the following discussion illustrates, later generations responded enthusiastically to this printed image of Chaucer, which, alongside its technical novelty, could nonetheless claim to be ‘true’. With this dual layer of authority, the Speed Chaucer portrait enjoyed the status of a vendible and prized paratext not only in Speght’s editions, but in a wide and revealing range of Chaucerian books. The remainder of this chapter traces the extraordinary reception of Chaucer’s printed portrait and argues that Speght’s editions introduced new readers to a compellingly simple idea that would later spread through the seventeenth-century English book trade: that books needed pictures of their authors. These copies supply evidence of the transmission of an iconographic tradition from manuscript into print and back again. More broadly, they show the role of newer printed volumes of Chaucer in determining the conventions by which older books, both manuscripts and prints, would be measured and even perfected.

4.4 Chaucer’s Absence, Chaucer’s Presence

Speed’s plate furnished an archetypal image of Chaucer and successfully co-opted Hoccleve’s narrative in order to promulgate it in the printed editions of 1598, 1602, and 1687. However, the starting point for my work on the Chaucer portrait was the observation that several of the copies I have examined are missing their Progenie leaves.Footnote 121 Like the holes left in places where illuminated initials have been excised from manuscripts, the absence of the portrait in some copies of Speght could signal its high cultural value for enthusiasts and collectors who envisaged other uses for it. Even when intact within copies of Speght, the plate may survive in a range of positions. In copies I have seen, it is most frequently positioned facing the poetic dialogue ‘The Reader to Geffrey Chaucer’ by the anonymous ‘H.B.’. This placement is especially apt in the 1602 edition, where the portrait would directly precede the verses titled ‘Vpon the picture of Chaucer’, composed by Francis Thynne for the updated publication.Footnote 122 Inserted plates generally seem to have had a standard position within books and in his editions, Speght refers to Speed’s plate as being in the ‘beginning of this booke’.Footnote 123 But the plate often appears elsewhere within Speght, too, and even in copies with early bindings.Footnote 124

In this respect, the Speed plate exemplifies some of the characteristics of what Remmert has called the ‘itinerant frontispiece’, a term that demonstrates the material separateness of this paratext.Footnote 125 Far from being confined to their original bibliographical contexts, such plates travelled from book to book, and out of books and into new contexts. As we shall see, this travel radiates outward in several directions where Chaucer’s portrait is concerned: movement of the plate and imitations of it to different locations within individual copies of Speght’s works; back in time, into medieval manuscripts and prior editions like those of Caxton, Thynne, and Stow; and forward in time too, as they were rendered anew by later collectors in the medium of manuscript. Both within and beyond copies of Speght, such survivals of the portrait and its copies in varied positions prove it to have been a highly mobile artefact whose popularity as an authorising paratext is amply attested by its reception at the hands of early modern and later readers. The portrait’s appearance in new contexts therefore shows the success of Speght’s Workes in creating new visual standards for the authority of the Chaucerian book.

The antiquary and amateur herald Joseph Holland is the architect of perhaps the best-known appropriation of Speed’s Chaucer portrait. To CUL, MS Gg.4.27, the fifteenth-century manuscript containing many of Chaucer’s collected works which was repaired and supplemented by Holland around 1600, he also added a copy of Speed’s plate. The details of the whole page – including the background, individual medallions bearing the names of Chaucer’s relatives, the poet’s smock, and, importantly, the shields of those depicted in the genealogy and on the later Chaucers’ tomb – were enlivened with careful illumination, with the arms gilded and tinctured. The effect of the image is a memorialising one, for Holland paired it with several passages (on the facing page) about Hoccleve’s portrayal and remembrance of Chaucer, themselves derived from Speght’s Life, which quotes the Regement in turn.Footnote 126 This treatment of the poet is in keeping with other authorising paratexts that Holland added to his medieval copy of Chaucer’s works following Speght. These include a series of stirring panegyric addresses: from Lydgate’s praise of Chaucer to the praise of ‘divers lerned men’, such as Ascham, Spenser, Camden, and Sidney, who ‘of late tyme haue written in commendation of Chaucer’.Footnote 127 Holland also supplemented the manuscript book with a cluster of short texts in the poet’s voice: the Retraction, ‘Chaucer to his emptie purse’, and ‘Chaucers words to his Scrivener’. This triad of works performs the textual equivalent of what the freshly embellished and tinctured portrait does visually: they superimpose a unifying authorial frame onto a book which, to its early modern owner, appeared to need one.Footnote 128 In this way, Holland’s supplements collectively recognise and amplify the Chaucerian character of the manuscript, with the effect of signalling the importance of the author, the book, and even its heraldically learned owner.

As Johnston has documented, the plate intended for Speght’s edition was also added into other Chaucerian books, and survives in copies of John Stow’s 1561 Chaucer edition in at least three cases.Footnote 129 The portrait leaf also appears as a frontispiece to a seventeenth-century manuscript of Sir Francis Kynaston’s complete Latin translation of the five books of Troilus and Criseyde.Footnote 130 Like that used to embellish Gg, the copies of the plate added to no fewer than three copies of Stow’s edition reflect a retroactive attempt to imbue these older books of Chaucer’s works with an authorial presence. In Kynaston’s fair copy of the Latin Troilus, meanwhile, the inserted plate forges an iconographic link between the new translation and the medieval author who first penned it. In purely chronological and technological terms, the medieval manuscript Gg, Stow’s edition, and Kynaston’s contemporary manuscript might seem to occupy divergent poles within the history of the Chaucerian book, but these copies are united by the desire of readers to authorise them. In each case, Chaucer’s portrait, along with the authority and historicity that it represents, assumes a visible place within these new bibliographical contexts.

Just as the material paper leaf bearing Speed’s engraved portrait could be enlisted to authorise printed and written copies (as well as a manuscript translation) of Chaucer’s works, so too were manuscript representations of the same image. Skilled replicas of Chaucer’s portrait, strongly suggestive of Speed’s and made in the early modern period and beyond, appear as an authorising image in a number of Chaucerian volumes. A nearly perfect copy of Caxton’s first edition of the Canterbury Tales held at the British Library now has as its frontispiece an eighteenth-century painted portrait of Chaucer, in the same orientation and style as Speed’s, and surrounded by a coloured and gilded foliate border evocative of the illuminations found in fifteenth-century English manuscripts.Footnote 131 An edition of Thynne’s 1542 Workes now at Columbia University likewise has a later watercolour rendition of the portrait inserted as a frontispiece.Footnote 132 This version, however, also features Chaucer’s arms, which are borne on a shield resting on a rock in the image’s background. In Takamiya, MS 32, formerly known as the Delamere manuscript, appears another modern variant, this time with Chaucer’s arms displayed in the top left-hand corner of the leaf. A final example of a Speed-style manuscript portrait appearing in a printed copy of Chaucer’s Workes comes in an edition of Speght (1602) at Trinity College in Cambridge, where the Progenie leaf is missing but where a facsimile tracing has been inserted in its place, complete with the genealogy, heraldic shields, and familial tomb as originally rendered by Speed (see Figure 4.6).Footnote 133 In all but the lattermost case, it is impossible to prove that these manuscript portraits were based on Speed’s Progenie page rather than on another exemplar. What is indisputable is that all of these manuscript imitations cater to a desire to locate the author’s image in printed and manuscript copies of his works. As Hoccleve’s Regement makes clear, this is a phenomenon older than print, but I am arguing that in Chaucer’s case, Speght’s editions both popularised the portrait and facilitated its further spread.

Figure 4.6 A facsimile inserted in place of Speed’s engraved portrait in a copy of Speght (1602), Munby.a.2.