According to Denman (Reference Denman2011), psychiatrists have long forgotten about the ‘psyche’ in treatment of their patients, and some perceive psychotherapy as something practised by psychologists and other practitioners rather than psychiatrists. Psychiatrists are promoted as practitioners of psychopharmacology and as managers of risk, rather than as considering psychologically minded ways of conceptualising their individual and systemic relationships with their patients. Since Denman's claims, further attempts have been made to address this in the training of psychiatrists in psychotherapeutic psychiatry and in the promotion of reflective practice across the life cycle of a career in psychiatry (Johnston Reference Johnston2017).

To add to the challenge of providing this psychotherapeutic education, the past 50 years have seen a burgeoning of distinct psychotherapeutic interventions; estimates put the number at 450 and growing (Clarkson Reference Clarkson1998; Norcross Reference Norcross2011).

Psychotherapeutic evolution

The equivalence paradox: common factor perspective

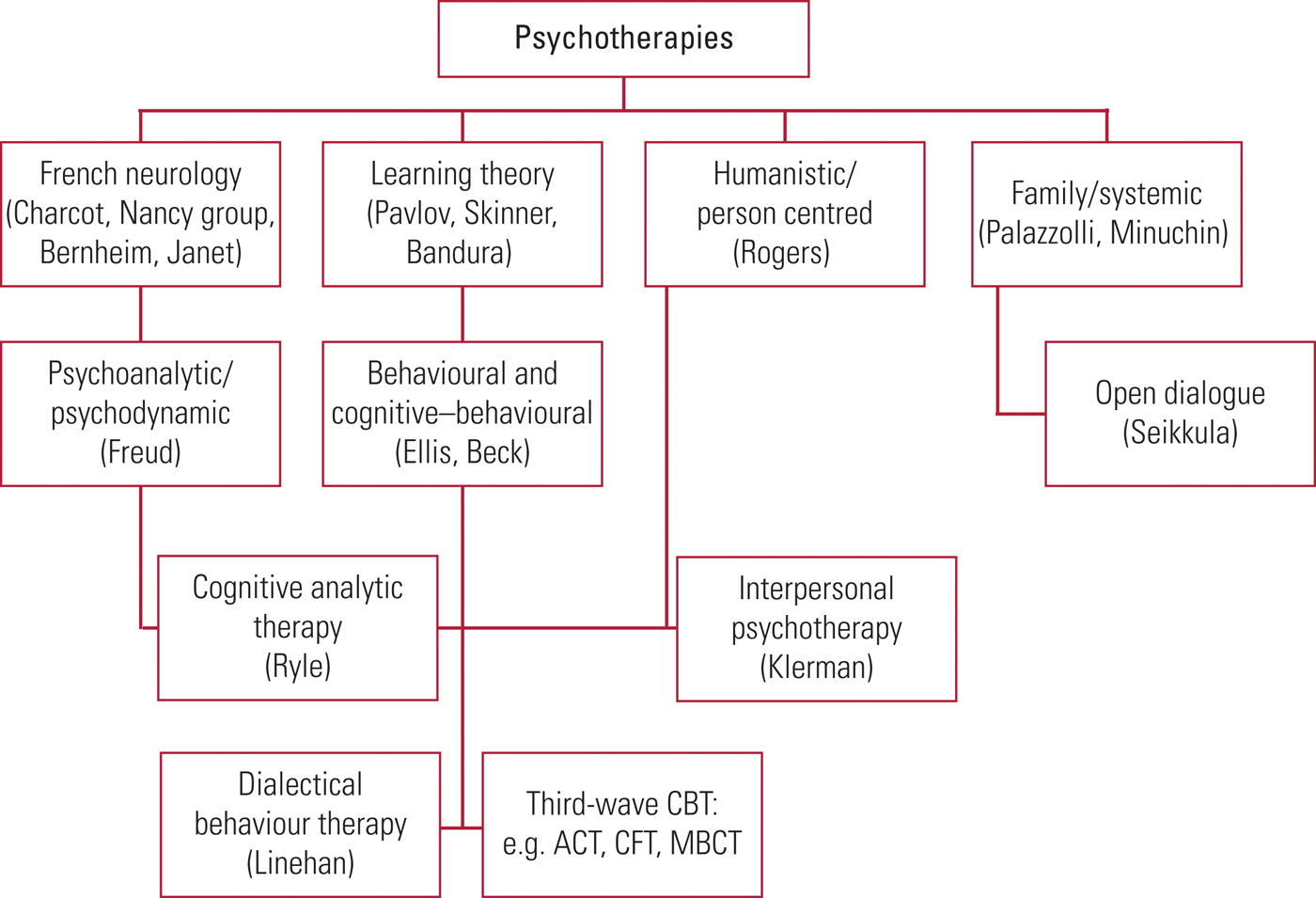

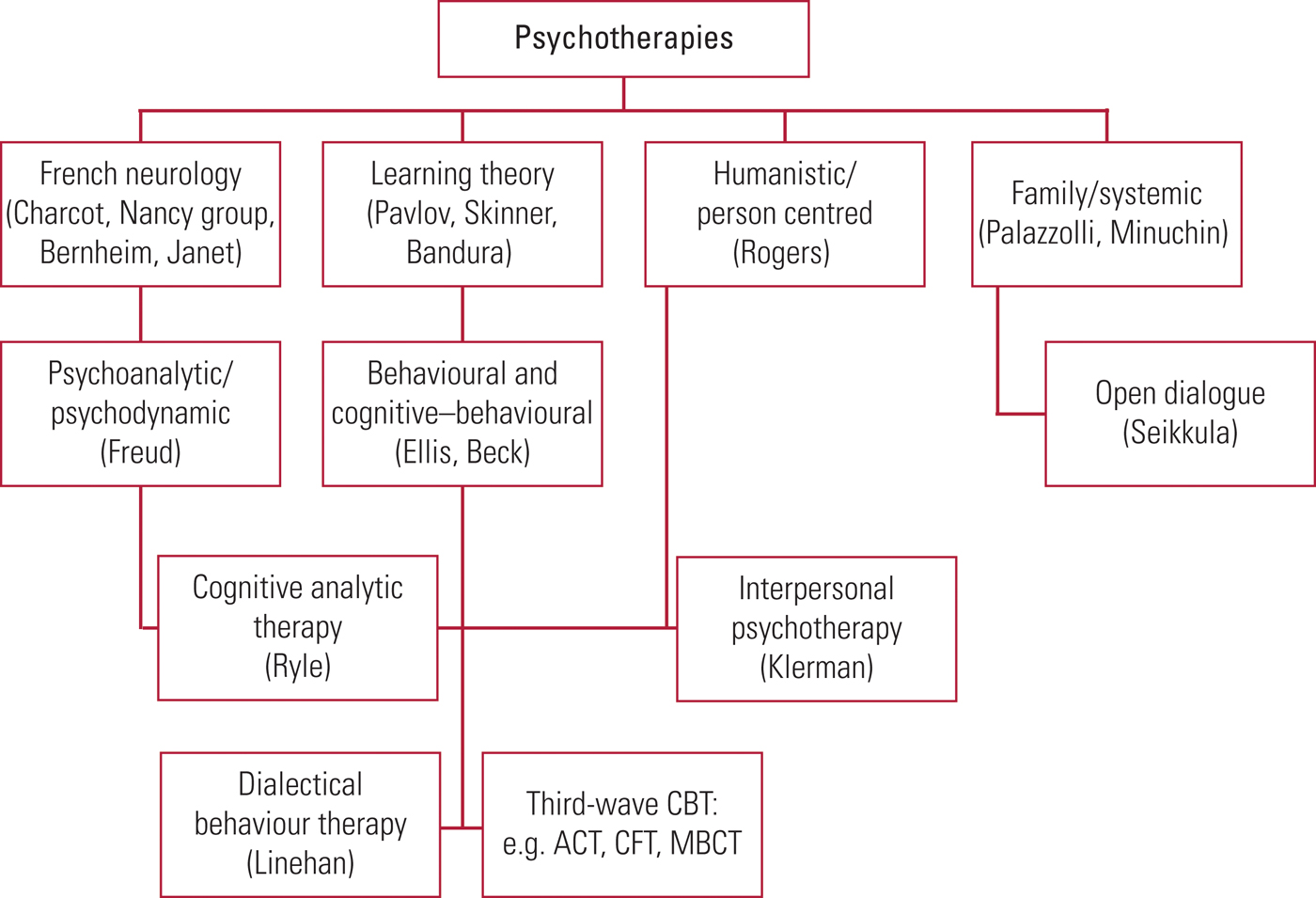

Psychotherapy has undergone an evolutionary process, with different modalities developing as offshoots from existing approaches: a psychotherapeutic phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). These divergent ‘waves’ of development have occurred in response to theorising, research evidence and attempts to understand individual vulnerabilities, psychopathology and psychiatric disorder (Luyten Reference Luyten, Mayes and Fonagy2015)

FIG 1 Generational family tree of the major psychotherapeutic modalities and their connections. ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CFT, cognitive functional therapy; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Laska et al (Reference Laska, Gurman and Wampold2014: p. 4689) state that ‘Each empirically supported treatment (EST) posits a specific mechanism for change based on a given scientific theory’. However, psychotherapy research illustrates the ‘Dodo bird hypothesis’, i.e. the equivalence of different therapies where no specific therapy is shown to have greater efficacy than any otherFootnote a (Luborsky Reference Luborsky, Singer and Luborsky1975).

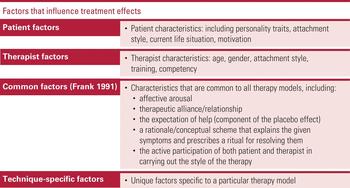

Each empirically supported treatment has a variety of common factors (Barlow Reference Barlow2004) and the equivalence paradox suggests that these, integrated with the treatment's specific factors, are mediators of therapeutic change. Common factor theory represents a growing area of psychotherapy research, and Imel & Wampold (Reference Imel and Wampold2008) in their review of common factors in psychotherapy, suggest that common factors account for 30–70% of the variance in outcomes (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Estimates of relative effects of factors contributing to psychotherapy outcomes

Other research highlights that the most important aspects of conducting all therapies are the therapeutic alliance, the therapist's skills and competencies and the patient's motivation, which combined synergistically constitute a working and efficacious therapeutic endeavour (Norcross Reference Norcross2011) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 Factors that influence the effect of psychotherapy.

We review here developments in the major modalities. Some of these are in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance, but others are yet to reach the randomised controlled trial (RCT) gold standard evidence necessary in order to be included.Footnote b

Psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic/psychodynamic psychotherapies

The development of psychoanalytic theory in brief

‘Psychoanalytic’ and ‘psychodynamic’ originate in the method Sigmund Freud developed at the end of the 19th century, and are often used interchangeably. Freud and Josef Breuer agreed that ‘the hysteric suffers mainly from reminiscences’ (Gay Reference Gay2006), i.e. alterations of remembering, and that hysterical symptoms made sense with the discovery of these memories’ hidden meanings. Symptoms were the logical expression of a psychic trauma and this trauma connected with memories and desires that had been thwarted and repressed. Freud suggested that ‘dynamic’ mental processes were at work to render these ‘unconscious’ to the sufferer; hence the word ‘psychodynamic’. The symptom is a compromise formation, containing both the original wish and the defence against that wish, so the wish is present in the symptom in a disguised and modified form. A cure, of a cathartic nature (abreaction), depended on the remembrance and expression of the trauma in a narrative form, within the context of a therapeutic relationship; hence ‘the talking cure’. This led to the discovery of transference to the treating physician. For various reasons Freud abandoned hypnotic cathartic abreaction in favour of the technique of free association, in which the patient says whatever comes to mind. This remains a fundamental technique to this day.

Freud's original conceptualisation (1905) was a ‘drive’ theory, with psychopathology understood as arising in response to the child's ability to negotiate phases of psychosexual development (oral, anal, oedipal, latency, etc.), with ‘fixation’ at phases where there had been a failure to do so. These fixation points are then regressed to at times of environmental and intrapsychic adversity.

With the development of Heinz Hartmann's ego psychology (1939) as well as Anna Freud's developmental lines (1965, 1974) and Erik Erikson's epigenetic principle (1950s), the focus of psychoanalytic understanding shifted onto the innate adaptive capacities of the ego in response to external and internal demands. The limitations of drive theory/ego psychology conflict models in working with psychotic and borderline mental states helped impel the development of object relations theory (Luyten Reference Luyten, Mayes and Fonagy2015), representing a move from an intrapsychic understanding to one based on an interpersonal relational understanding of psychic development, originating with work of Melanie Klein, and developed by Wilfred Bion (1962). Ronald Fairbairn (1952) went further, proposing that drives are object-seeking, rather than pleasure-seeking as proposed in drive theory. Object relations theory conceptualises the psyche as built up by the internalisation, in the early years of life, of relationships – representations of the self and the ‘object’ – and an affect that links the two, i.e. self–object–affect representations. Donald Winnicott (1960) creatively integrated drive theory and object relations theory, seeing our developing sense of self as embedded in the matrix of the mother–infant relationship. In the USA, Heinz Kohut (1971) developed self psychology, with an emphasis on empathic caregiving as necessary for healthy infant development, conceptualising deficits in care as leading to disorders of the self: depressive, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders.

John Bowlby's attachment theory may be seen as a natural progression of object relations, bringing an ethological research perspective; in order to survive in times of distress, the infant is not object-seeking but in search of close proximity to an identified caregiver – a secure base. This experience of security enables regulation of emotional distress (Stroufe Reference Stroufe1996). Identified patterns are found between categories of infant attachment relationship and adult attachment styles, and parental mental models of attachment are the predicates of subsequent patterns of attachment between mother and infant (Fonagy Reference Fonagy2001).

Psychoanalytic theories therefore share basic assumptions of understanding psychopathology that can be traced along its development. They take a developmental perspective, emphasising the influence of early developmental experience on shaping the psyche; they focus on unconscious motivation, intentionality, and the inner world and psychological causality; they recognise the ubiquity of the transference, i.e. all relationships are shaped by past relationships, especially with caregivers; they consider the whole person, not just one aspect; they recognise complexity of interrelated aspects of psychological functioning; and they take a dimensional approach to psychopathology, with a continuity between normal and disrupted personality development (Luyten Reference Luyten, Mayes and Fonagy2015).

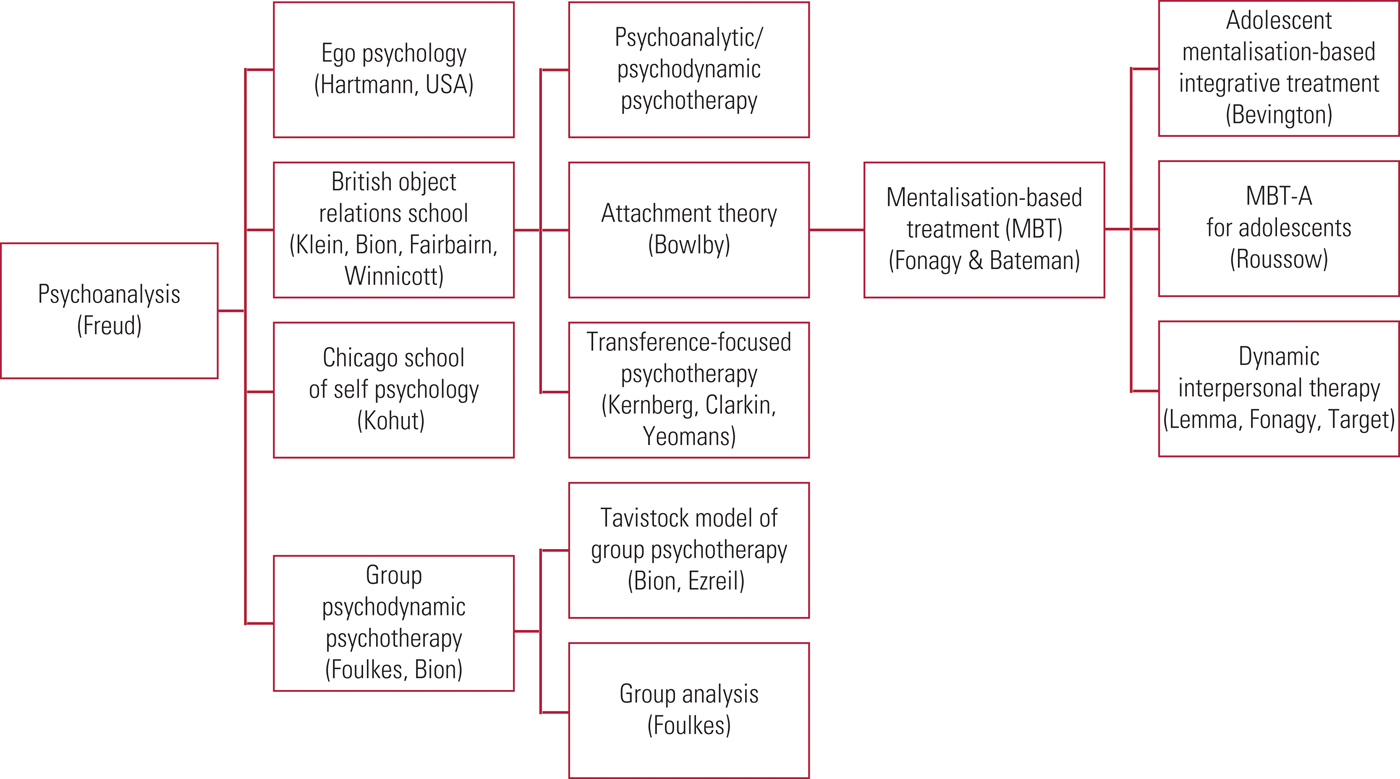

The development of psychoanalytic theory and approaches is outlined in Fig. 3.

FIG 3 The development of psychoanalytic theory and approaches.

Psychodynamic psychotherapy: treatment principles

The general principle is of creating a safe consistent setting – of which the therapist is a principal component – in which the patient can begin to articulate their problems, talking as freely as they are able. This can be technically very challenging. Anxiety needs to be addressed, or an absence of anxiety noted, and resistance to exploration is to be understood, especially in relation to the therapist: the transference and – informed by the therapist's experience – the countertransference.

Problems in external relationships, shaped by early developmental relationships, will be repeated in the context of the therapeutic relationship. The patient and the psychotherapist both play their part in this repetition, and by recognising and exploring these sometimes subtle manoeuvres, the patient's difficulties may be better understood and gradually worked through: ‘What cannot be remembered is destined to be repeated’ (Freud Reference Freud1914).

Psychotherapists will dynamically gauge whether the patient can use an expressive, exploratory therapy or will need a more supportive approach: the ‘expressive–supportive continuum’. This will depend on both individual patient variables (both internal and external resources) and the setting, i.e. frequency/intensity/community/in-patient, etc.

Blagys & Hilsenroth (Reference Blagys and Hilsenroth2000) reviewed the comparative psychotherapy process literature to delineate seven reliably distinguishing features of psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy, and in Table 2 we compare these with features of classic psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

TABLE 2 Distinguishing/unique features of psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy

a Features identified by Blagys & Hilsenroth (Reference Blagys and Hilsenroth2000).

Group psychodynamic psychotherapy

In group psychodynamic psychotherapy, group cohesion is often regarded as the equivalent to the concept of therapeutic alliance in individual psychotherapy. Group cohesion generally refers to the emotional bonds among members for each other and for a shared commitment to the group and its primary task. It is the group process variable that is generally linked to positive therapeutic outcome (Burlingame Reference Burlingame, McClendon and Alonso2011).

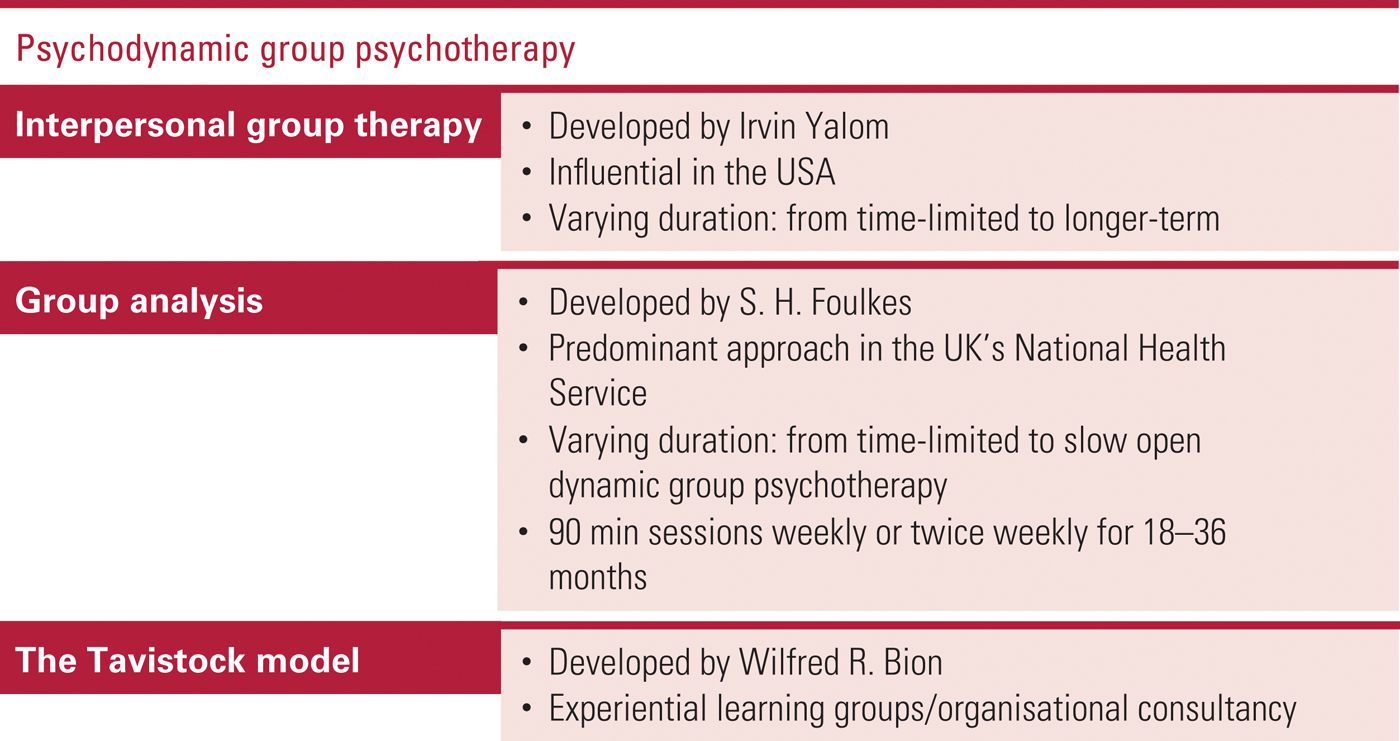

Group psychotherapeutic approaches are widely used in the NHS, and we outline the main strands in Fig. 4. Montgomery (Reference Montgomery2002) gives a good exposition of the application of group approaches in psychiatry, which is beyond the scope of this article.

FIG 4 The main strands/models of psychodynamic group psychotherapy.

New clinical approaches

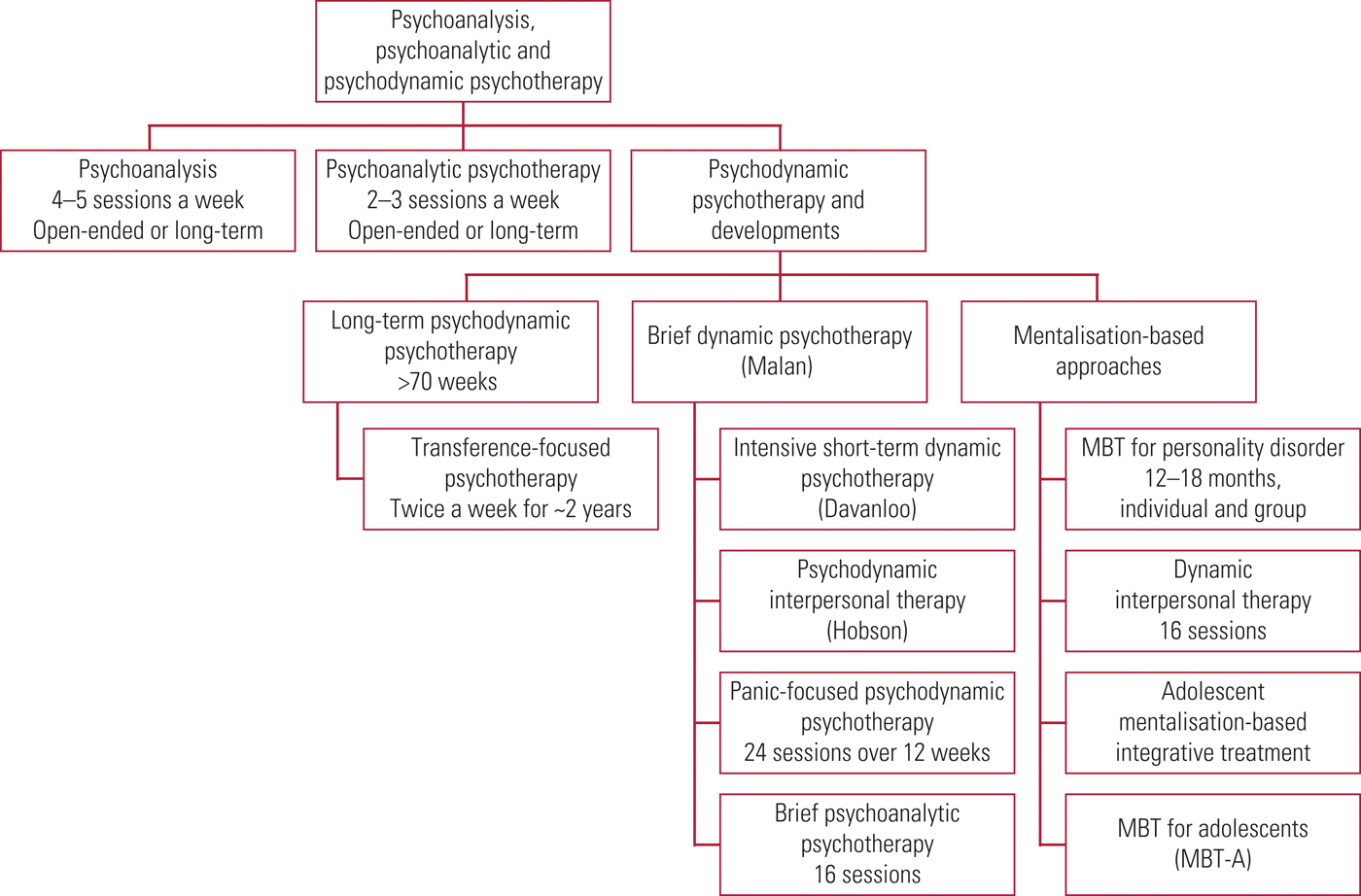

The theoretical shift to an interpersonal-relational understanding of development, informed by attachment theory, neuroscience, genetics and social cognition, has led to many new clinical approaches, as illustrated in Fig. 5. However, the scope of this article limits our focus to two main strands, which place the therapeutic relationship in the ‘here and now’ of the encounter as the central clinical focus; these can be roughly categorised as those with a transference focus and those associated with a mentalisation-based approach.

FIG 5 Family tree of psychodynamic psychotherapies. MBT, mentalisation-based treatment.

Therapies with a transference focus

These include transference-focused psychotherapy itself, and briefer approaches such as panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy and brief psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

Transference-focused psychotherapy

was developed by Otto Kernberg in the USA (for an overview see Kernberg Reference Kernberg, Yeomans and Clarkin2008). It is an operationalised evidence-based psychoanalytic psychotherapy for patients with borderline personality disorder. Its aim is to reactivate in the psychotherapy the patient's split-off internalised object relations, positive and negative, as they come to life in the here and now of the session and are interpreted in the transference.

A treatment contract is established to manage potential acting out and create a therapeutic setting to facilitate reactivation of split-off object relations. It is a longer-term psychotherapy conducted twice a week over a period of 2 years. In an RCT, has been shown to be more efficacious than treatment by experienced community psychotherapists (Doering Reference Doering, Hörz and Rentrop2010).

Panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy

was developed by a group led by Fredric N. Busch and Barbara Milrod (Milrod Reference Milrod, Busch and Cooper1997), again in the USA. It conceptualises anxiety and panic disorder within a psychoanalytic framework of understanding, including a constellation of defences, insecure attachments and fearful dependency. It is a manualised approach, focusing on core conflicts relating to recognition of anger, ambivalent feelings about autonomy, and fears of loss or abandonment. A focus on the transference, using clarification, confrontation and interpretation, allows elucidation of this dynamic, and particular attention is paid to the negative transference. Therapy is delivered in 24 sessions over 12 weeks. It has proven effectiveness in a small RCT (Milrod Reference Milrod, Leon and Busch2007).

Brief psychoanalytic therapy

was developed by Peter Hobson at the Tavistock Clinic, London (Hobson Reference Hobson2010). It is a manualised 16-session psychotherapy that has at its focus the transference in the here and now, and ‘in-transference interpretations’, framed in a way to help patients re-integrate aspects of their emotional life.

Therapies with a mentalisation focus

The second main strand of new therapies take a mentalisation-based approach, and they include Bateman & Fonagy's mentalisation based treatment (MBT) (Bateman Reference Bateman and Fonagy2004). These are the most widely practised in their application to emergent and borderline personality disorder.

The capacity to mentalise is defined as the ability to understand the behaviours of the self and others in terms of underlying mental states and intentions. Mentalisation was first operationalised as ‘reflective functioning’, described by Fonagy & Target (Reference Fonagy and Target1997) as ‘the mental function which organises the experience of one's own and others’ behaviour in terms of mental state constructs’. Reflective function is formed in the presence of the caregiver/another – ‘to be known in another's mind’ – and thus derives from the caregiver's own capacity for reflective functioning. Good reflective functioning in the caregiver is associated with good outcomes and secure attachment. If early attachment is disrupted, perhaps as a result of unresponsiveness, neglect and/or hostility from caregivers, then when the attachment system is activated in relationships, problematic patterns of relating are repeated, characterised by anger, then aggression, and a closing down of the mind in relation to others (Fonagy Reference Fonagy, Steele and Moran1991). This lack of safety in turn triggers the attachment system so the child (adult) becomes proximity-seeking but mentally distant. This pattern, triggered by separation or potential loss, together with a fragile sense of self perceived as being threatened, is critical to understanding the presentation of patients with borderline personality disorder and the difficulties they can encounter in psychotherapy or when admitted to hospital, both of which activate the attachment system.

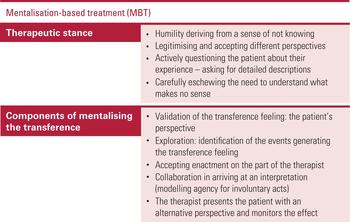

Mentalisation-based therapies therefore have at their therapeutic focus the capacity for mentalisation. The initial task is ‘stabilising emotional expression’, and then the therapist's interventions are aimed at reinstating and maintaining mentalising when it has been lost or may be lost. In addition to generic psychotherapeutic approaches, the technique also stresses the attachment relationship within therapy through focusing on the patient–therapist relationship, which Bateman & Fonagy (Reference Bateman and Fonagy2010) describe as ‘mentalising the transference’ (Fig. 6). They make this distinction to distinguish from the use of transference interpretation, a cornerstone of psychoanalytic technique described by Strachey (Reference Strachey1934), as this assumes a mentalising capacity that patients may not have. The focus is on the here and now of the therapeutic encounter rather than making ‘genetic’ links to the past, although the person is understood in the context of their developmental history. Recovery of mentalisation helps emotional regulation and builds up the capacity for self-regulation.

FIG 6 The therapeutic stance and components of mentalisation-based treatment (MBT) (after Bateman & Fonagy Reference Bateman and Fonagy2010).

A substantial evidence base underpins MBT, demonstrating that it produces more improvement in patients with borderline personality disorder than structured clinical care and that improvement is sustained over time (Bateman Reference Bateman and Fonagy2008, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009).

Brief dynamic interpersonal therapy (DIT)

was developed by Alessandra Lemma, Mary Target and Peter Fonagy for the treatment of depression and anxiety, and it is perhaps the most well-known development of MBT (Lemma Reference Lemma, Target and Fonagy2011). DIT grew out of the development of a competency framework for a range of psychological therapies, including psychodynamic psychotherapy (Lemma Reference Lemma, Roth and Pilling2008). It incorporates the core shared psychodynamic principles listed in Table 2, and is informed by Harry Stack Sullivan's interpersonal psychoanalysis, in which depression and anxiety are manifestations of difficulties in interpersonal relationships. DIT has a dual focus on interpersonal and affective problems, proposing that distortions of cognitions in depression and anxiety link to failures of mentalisation. An interpersonal affective focus (IPAF) is generated with the patient and this becomes the focus for the structured manualised therapy over 16 sessions. It is now incorporated into the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme and has a growing evidence base.

Adolescent mentalisation-based integrative treatment (AMBIT)

was developed by Dickon Bevington, Peter Fuggle and colleagues (Bevington Reference Bevington, Fuggle and Fonagy2013). AMBIT is an outreach model of working with young people with severe and multiple psychological and social needs who are avoidant of mainstream services. It has at its centre mentalisation as an integrating framework for its application. Mentalising is supported across a systemic network of relationships, including:

-

• a strong key working relationship with the young person

-

• the young person and their family

-

• the key worker and their colleagues

-

• the team and the wider multi-agency network.

A novel component is a wiki-based manual (https://spaces.xememex.com/ambit) to which teams can contribute good practice tips and share local solutions to problems. Over 80 teams around the UK have now been trained to deliver AMBIT, and initial evaluation is encouraging.

Mentalisation-based treatment for adolescents (MBT-A)

is another development of MBT, by Trudi Roussow (2012). Integrating individual MBT and family MBT sessions, it aims to help young people and their families to improve awareness of their own and others’ mental states through a mixture of experiential psychoeducational approaches and modelling of an inquisitive stance demonstrated by the psychotherapist. It was developed for young people with self-harm and shown to be more effective than treatment as usual (Roussow Reference Rossouw, Midgely and Vrouva2012).

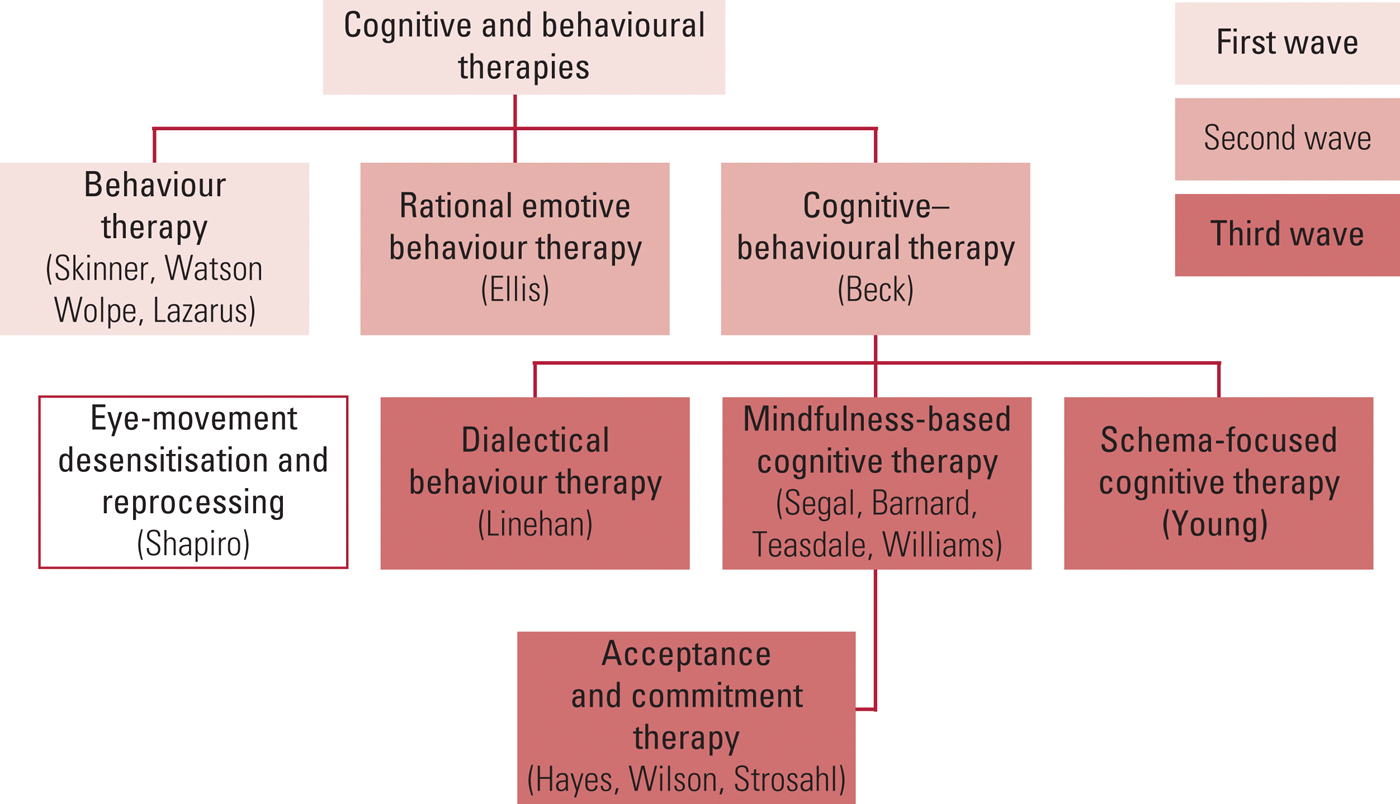

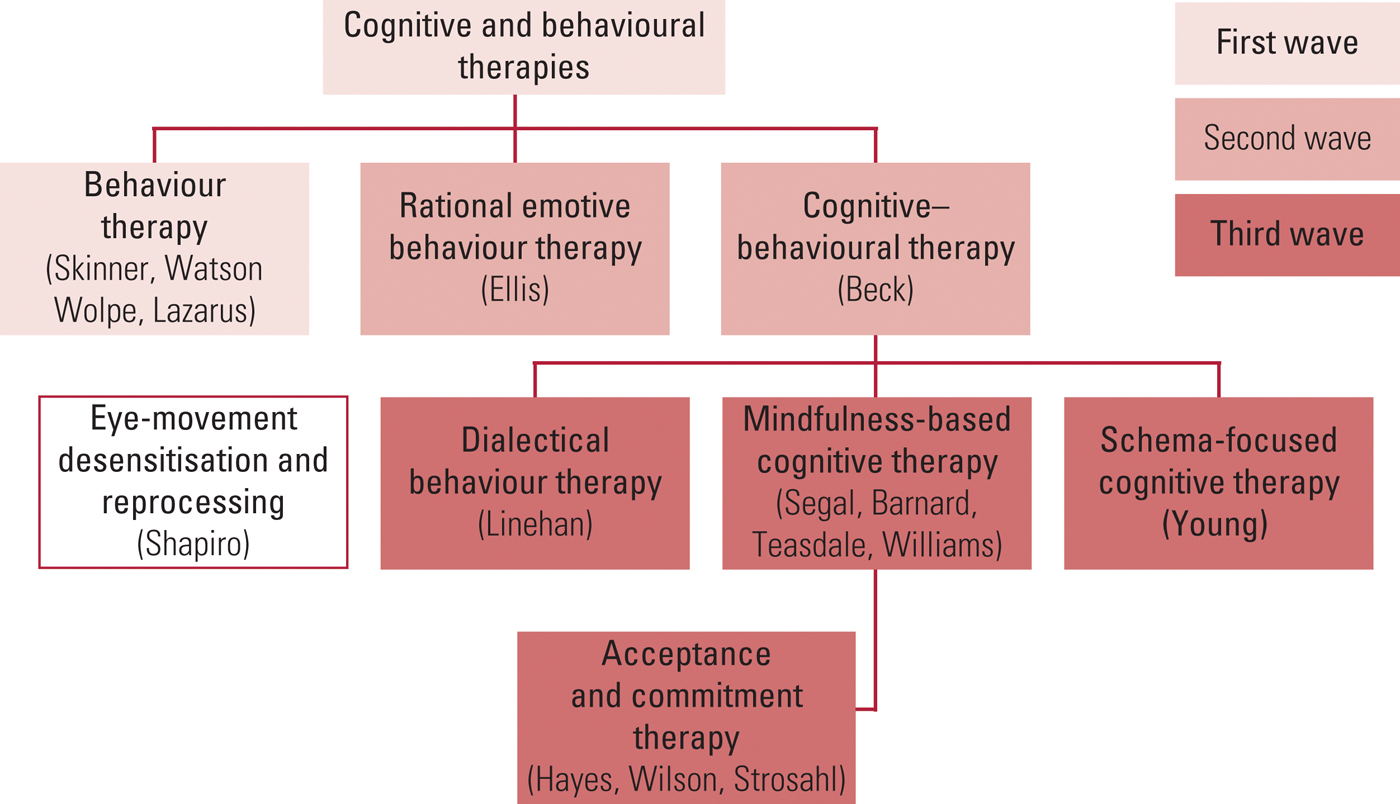

The origins of cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is the other major psychotherapeutic approach (Fig. 7). Aaron T. Beck, the most influential figure in CBT, described ‘automatic thoughts’ (Beck Reference Beck2011) and is a CBT ‘spokesman’, but Albert Ellis could be considered the true father of the approach. It is interesting to note that both Ellis and Beck started out as practising psychoanalysts before going on to develop rational therapy and cognitive therapy respectively.

FIG 7 The family tree of cognitive and behavioural therapies.

To foster understanding of the CBT approach we focus on the two elements used in its construction: cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy.

Cognitive therapy

Beck and colleagues (Reference Beck, Rush and Shaw1979) describe cognitive therapy as an active, time-limited, structured and directive approach to the treatment of various psychological disorders. According to cognitive therapy's theoretical rationale, human behaviour and affect are regulated by the ways in which we structure the world. Our cognitions are built upon schemas (assumptions or attitudes), our underlying ways of processing information about the self, world and future, which have their basis in our past experiences (Beck Reference Beck, Rush and Shaw1979). Cognitive therapy is therefore focused on the patient's interpretations and thoughts regarding situations, and it is useful for those able to monitor and articulate their affect and thoughts (Beck Reference Beck, Rush and Shaw1979, Reference Beck, Freeman and Davis2004). Over time, cognitive therapy has served as an effective intervention in the treatment of depression, and its model has been developed for the treatment of anxiety, phobias, eating disorders, substance misuse and personality disorders (Beck Reference Beck, Freeman and Davis2004).

Behaviour therapy is based on animal learning models researched by Pavlov and Thorndike. It is predicated on the assumption that learning is at the core of all human behaviour (Meyer Reference Meyer and Chesser1970) and it focuses on the patient's avoidant, self-destructive or disruptive behaviours. Patients are taught problem-solving skills and are introduced to completely new sets of behavioural skills, which in turn affect their mood and thinking (Meyer Reference Meyer and Chesser1970; McLeod Reference McLeod2013). According to Gilbert (Reference Gilbert2008) there are two components of behaviour therapy:

-

1 the patient is exposed to the process of desensitisation and has to face the feared and avoided situation

-

2 the patient is either rewarded or punished for their actions (operant conditioning).

CBT therefore derives from behavioural and psychological models of human behaviour and both cognitive and behavioural interventions. Grant et al (Reference Grant, Townend and Mills2011) describe CBT as exploring the personal meanings, behaviours and emotions associated with the individual's difficulties. The context of past experiences, and genetic and biological influences, as well as current environments, are also taken into account. In the course of therapy, practitioner and patient are both involved in the process of exploring what might be the cause of the patient's problems, the maintaining factors and the likely outcome of alleviating the problems (Freeman Reference Freeman, Pretzer and Fleming2004). This is achieved through the careful use of Socratic questioning and guided discovery, through which both the therapist and the patient try to understand the patient's subjective experiences and how these could be responsible for their current problems (Grant Reference Grant, Townend and Mills2011). The key principles of CBT are outlined in Fig. 8.

FIG 8 The key principles of the cognitive–behavioural approach (Greenberg Reference Greenberg and Padesky1995; Beck Reference Beck2011; Dryden Reference Dryden and Branch2012; Maguire Reference Maguire2012).

Dialectical behaviour therapy

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) was originally developed by Marsha Linehan as an intervention for self-harming behaviours and it evolved into an intervention for patients with borderline personality disorder (Gilbert Reference Gilbert2008; Panos Reference Panos, Jackson and Hasan2014). Incorporating cognitive, behavioural, mindfulness and acceptance strategies, DBT aims to help individuals dealing with emotional dysregulation, as in borderline personality disorder.

Linehan placed the therapeutic alliance at the core of DBT, promoting the therapist as an ally who adopts an attitude of Buddhist unconditional acceptance combined with intersubjective tough love. A number of studies have proved the effectiveness of DBT in disorders with similar characteristics (James Reference James2015). For individuals struggling with self-destructive impulsiveness, lacking self-regulation and distress tolerance skills, the approach is particularly focused on four behavioural targets:

-

• diminishing of life-endangering suicidal and parasuicidal acts

-

• diminishing of behaviours able to interfere with therapy (e.g. premature drop-out, extensive contact with therapist)

-

• change and reduction of behaviours that interfere with the quality of the individual's life

-

• development of behavioural skills such as mindfulness, self-management and emotion regulation (Panos Reference Panos, Jackson and Hasan2014).

Patients can benefit from DBT if they have not acquired the necessary skills to manage their emotions or to establish and/or maintain a relationship. This could be because of neglectful parenting or attachment disruption. Emotion dysregulation is a key problem, and the interventions often focus on anger management and anxiety regulation. Other key concepts of DBT include:

-

• the therapeutic relationship acts as a model of a healthy relationship, enabling the patient to build up less harmful behaviours

-

• techniques/exercises involving mindfulness skills enable the patient to be more aware of negative judgements they hold of themselves and make about others

-

• strategies are taught to help the individual with treatment adherence (Maguire Reference Maguire2012; Brodsky Reference Brodsky and Stanley2013).

The main assumptions of the intervention are that patients are:

-

• doing the best they can

-

• striving to improve

-

• trying to be more motivated, achieve more and try harder

-

• not the sole cause of their problems, but trying to solve them regardless

-

• in a position in which their lives are unbearable

-

• unable to fail therapy (Brodsky Reference Brodsky and Stanley2013).

It is important to understand that clinicians delivering DBT also need support (Brodsky Reference Brodsky and Stanley2013).

A meta-analysis of DBT found moderate effect sizes for patients with borderline personality disorder (Kliem Reference Kliem, Kröger and Kosfelder2010).

Schema-focused cognitive therapy

Conceived by Jeff Young, schema-focused cognitive therapy (SFCT) is based on the principles of both cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy (Montgomery-Graham Reference Montgomery-Graham2016). SFCT was developed for work with patients with borderline personality disorder and patients with other deep-seated interpersonal difficulties. According to Young, for serious psychiatric disorders to be treated effectively, cognitive therapy must incorporate elements of attachment and object relations theory, as well as techniques from emotion-focused and Gestalt therapies (Sempértegui Reference Sempértegui, Karreman and Arntz2013).

SFCT shares with cognitive therapy the concept of early maladaptive schemas (EMS), and these form the focus of therapy. Maladaptive schemas are best defined as negative perceptions of oneself, others and the world/environment. They are pervasive, give meaning to each experience and integrate cognitions, emotions and memories as well as bodily sensations. They do not include behaviour, which is conceptualised as a reaction to the schema (Sempértegui Reference Sempértegui, Karreman and Arntz2013; Montgomery-Graham Reference Montgomery-Graham2016).

SFCT deals directly with 18 early maladaptive schemas grouped into five domains, broad categories of unmet need. The patient's inner world is characterised by five schema modes – behavioural repertoire subsets – which individuals resort to when triggered by a current experience. Patients are thought to attempt to cope consecutively with their distress in three ways (Maguire Reference Maguire2012; Montgomery-Graham Reference Montgomery-Graham2016):

-

1 overcompensation

-

2 schema avoidance, and

-

3 surrender.

The therapeutic relationship plays a central role in SFCT through the process of ‘limited reparenting’. This addresses the unmet needs that resulted in early maladaptive schemas, acknowledging the patient's dependency needs while supporting their ‘healthy adult mode’. Techniques include the use of guided imagery and imagery rescripting, flash cards made collaboratively with the therapist that the patient refers to in between sessions, and diary keeping.

SFCT tends to be longer term, over a number of years, and twice weekly, and there is good evidence for its effectiveness (Giesen-Bloo Reference Giesen-Bloo, Van Dyck and Spinhoven2006; van Asselt Reference van Asselt, Dirksen and Arntz2008).

Acceptance and commitment therapy

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is being called a ‘contextual cognitive therapy’ and it has its origins in behavioural analysis and relational frame theory. It is a transdiagnostic model which perceives mental distress as a concept rooted within psychological inflexibility, leading to a narrowed behavioural repertoire and reduction of the patient's ability to lead a fulfilled life and to act according to their values. ACT endeavours to change the individual's relationship to their internal experiences (i.e. thoughts, sensations) rather than the experience itself (Brand Reference Brand and Palmer2015). ACT is a behavioural type of therapy, and is focused on two types of action (Harris Reference Harris2009):

-

• value-guided action: the patient is asked what they want to stand for in their life and what really matters for them; their core values are used to guide, inspire and motivate behavioural change;

-

• mindful action: action is taken consciously and with full awareness; the patient is asked to open up to their experience and become fully engaged in whatever they are doing.

ACT enables patients to accept life's inevitable pain and difficulties. Interventions ‘enable experiential “de-fusion” from the meaning of words and concepts’ (Maguire Reference Maguire2012: p. 669), as well as teaching mindfulness skills to deal with painful thoughts and feelings, thus helping patients to clarify their values and goals and to take actions to enrich their lives (Harris Reference Harris2009; Maguire Reference Maguire2012).

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)

Developed by Zindel V. Segal, its main purpose is to treat recurrent and severe depression and to reduce the risk of relapse (Segal Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2013). This can be achieved by the practice of mindfulness, combining a purposeful focus with non-judgemental awareness of experience and thoughts. This mindful awareness is effective in reducing the intensity and length of depressive episodes. According to theoretical findings, negative mood can exacerbate depression by increasing negative images and thoughts (Maguire Reference Maguire2012; Segal Reference Segal, Williams and Teasdale2013). The intervention places slightly less emphasis on bodily movement (as, for example, in its older cousin mindfulness-based stress reduction, the intervention developed by Jon Kabat Zinn) and it includes a 3-minute breathing space to rapidly restore a mindful attitude, bridging ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ mindfulness practices. Patients are given exercises to monitor and analyse their dysfunctional thinking and its connection to their mood (Mace Reference Mace2007).

Eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing

In the late 1980s, Francine Shapiro noticed that spontaneous saccadic eye movements reduced her anxiety in relation to disturbing thoughts that were preoccupying her (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001). This experience led her to develop eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) as a therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). EMDR incorporates cognitive and behavioural strategies, alongside getting the patient to focus on a moving object while recalling distressing memories, problems, feelings and associated bodily sensations.

EMDR views the psychopathology of PTSD as based on unprocessed memories of a traumatic event that are physiologically stored intact, which if subsequently triggered by a situation in the present, are automatically reactivated with the associated feeling, physical sensations and beliefs encoded at the time of the event.

The goal of EMDR is to teach the patient how to process these memories to reduce their impact and to help them develop coping mechanisms (Davidson Reference Davidson and Parker2001).

EMDR has been refined into an eight-phase treatment outlined in Fig. 9. The phases and the checks and balances contained within the structured approach help in determining whether a patient is ready to process trauma and whether time is needed to develop internal resources to help them manage ‘the intense negative arousal’ (Dworkin Reference Dworkin2005: p. xviii).

FIG 9 The eight phases of eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001).

There is good evidence for the effectiveness of EMDR in PTSD, although the definitive effects of the bilateral stimulation are still under investigation (Lee Reference Lee and Cuijpers2013).

Humanistic therapies: person-centred therapy

Humanistic approaches share three main principles (Du Plock Reference Du Plock, Woolfe, Strawbridge and Douglas2010):

-

1 a strong focus on the ‘here and now’

-

2 a holistic perspective and totality of the client

-

3 the recognition of the client's autonomy.

Person-centred therapy (PCT) was introduced by Carl Rogers in Reference Rogers and Koch1959, and it is still one of the core orientations of the humanistic field, as well as being one of the most widely used approaches in counselling and psychotherapy (McLeod Reference McLeod2013). Rogers developed this non-directive approach as a protest against prescriptive diagnostic perspectives (Dryden Reference Dryden and Branch2012). Therapists working within the person-centred framework use core conditions of congruence and unconditional positive regard to empathically understand their patient's (client's) frame of reference (Box 1) (Gillon Reference Gillon2007; Mearns Reference Mearns, Thorne and McLeod2013). In this understanding, the ‘person’ is regarded as an expert on their own life and problems. In a therapeutic relationship where proper conditions for growth are provided, the individual's self-actualisation is enabled.

According to Rogers, incongruence occurs when there is a conflict between self-concept and actual experience. One of the main goals of PCT is to reduce incongruence, which is believed to be responsible for all psychological distress and to be the main cause of mental disturbance (Rogers Reference Rogers and Koch1959; McLeod Reference McLeod2013). When incongruence is perceived as a threat to the self, anxiety develops (Gillon Reference Gillon2007; Sanders Reference Sanders2012).

Rogers believed that growth towards health, autonomy and differentiation are innate and are ongoing throughout a person's life (Rogers Reference Rogers and Koch1959; McLeod Reference McLeod2013).

Box 1 Carl Rogers's necessary conditions for constructive personality change

-

• The client and therapist are in psychological contact

-

• The client is in a state of incongruence, vulnerable or anxious

-

• The therapist is congruent and harmonised in the relationship

-

• The therapist experiences unconditional positive regard for the client

-

• The therapist empathically engages in the process of understanding the client's frame of reference and attempts to communicate this occurrence to the client

-

• The client perceives the therapist's unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding at least to a minimal degree

(After Rogers Reference Rogers1957)

Research shows that when a therapist demonstrates two out of three core conditions patients improve substantially (Rudolph Reference Rudolph, Langer and Taush1980). Kirschenbaum & Jourdan (Reference Kirschenbaum and Jourdan2005) highlight many studies on empathy and on congruence which indicate that certain types and amounts of self-disclosure by the therapist can be beneficial, but harmful if inappropriate or excessive. Kensit (Reference Kensit2000) claims that neither unconditional positive regard nor non-direction is effective for therapy, and that confrontation of the patient's primary and secondary defences assists self-actualisation.

On the whole, humanistic therapies in general and PCT in particular are minimally structured, non-directive (putting the person in the role of an expert on their own life) and time-limited. Change is achieved through enabling the person to explore their internal behaviours and experiences in an open way (Maguire Reference Maguire2012).

Conclusions

A good knowledge of the psychotherapies is essential for modern psychiatric practice. Understanding common factors is important. Laska et al (Reference Laska, Gurman and Wampold2014) suggest that the common factor approach is misunderstood as a shorthand for the therapeutic alliance, whereas that is only one of a number of common factors. However, for the purposes of this article, if psychotherapists and psychiatrists understand that the establishment and maintenance of a therapeutic alliance is an essential common factor, and address impingements, threats and ruptures to the alliance, their patients will have better outcomes.

As we have shown, notwithstanding the use of divergent technical language, different models of therapy have overlapping techniques as well as common factors. Some models remain intrapsychic in focus, seeking to change the patient's relationship to their thoughts, feelings or body, whereas others remain deeply relational and it is the patient's minds in relation to others that is the focus. Fonagy & Adshead (Reference Fonagy and Adshead2012) make a cogent case that all psychotherapies share the common mode of action of improving mentalisation and reflective function (not to be confused with self-reflection). Perhaps we can conceive of the capacity to be able to inhabit a ‘third space’ in relation to ourselves and others which allows for the potential for creative thought that can enable the resolution of psychic pain.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The therapist's involvement in the process of therapy in cognitive–behavioural therapy is:

-

a minimal

-

b totally non-directive

-

c free associative

-

d as important as the patient's and is collaborative

-

e none of the above.

-

-

2 Dialectical behaviour therapy assumes that patients are:

-

a fully responsible for their actions

-

b unable to fail

-

c helpless and require constant support

-

d the sole cause of their problems

-

e unable to decide for themselves.

-

-

3 Which therapeutic approach is understood in terms of object relations theory?

-

a person-centred therapy

-

b cognitive–behavioural therapy

-

c acceptance and commitment therapy

-

d transference-focused psychotherapy

-

e none of the above.

-

-

4 The therapeutic alliance/relationship is highly significant:

-

a for cognitive–behavioural therapy

-

b for psychodynamic approaches

-

c for dialectical behaviour therapy

-

d only for person-centred therapy

-

e for all psychotherapeutic modalities.

-

-

5 The Dodo bird hypothesis assumes that:

-

a there exists only one correct therapeutic modality

-

b all modalities are similar in terms of their effectiveness

-

c the therapeutic alliance is an essential factor for all therapies

-

d psychoanalysis should be considered an extinct therapeutic approach

-

e none of the above.

-

MCQ answers

1 d 2 b 3 d 4 e 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.