Introduction

Employment rates of therapeutic radiographers decreased from 2013 to 2016, with almost 60% employed from partner Higher Education Institutions in 2013/2014 compared with less than 40% by 2015/2016. 1 A report prepared for Cancer Research UK by the Tavistock InstituteReference Cullen, Drabble, Castellanos and Brissett 2 cautioned that a shortage of radiographers was diminishing the quality of radiotherapy treatment in England, and that poor retention among trainee radiographers was a key contributor to this shortage. Health Education England reported that the average attrition rates for therapeutic radiography students across 2013–2015 was 33%, and stated that the number of therapeutic radiographers will need to increase by 18% by 2021 to deliver the National Cancer Workforce plan. 1

A 2014 survey conducted by the Society of Radiographers discovered that dissatisfaction with clinical placements was rated the most frequent reason for leaving radiotherapy programmes. 3 There are a wide range of issues that may contribute to a student’s clinical placement experience. For example, a study exploring the clinical learning environment of nursing students reported two major challenges: the context within which their learning experiences occurred and relationships with others.Reference O’Mara, McDonald, Gillespie, Brown and Miles 4 The relationship between students and their clinical supervisors may be of particular note.

The College of Radiographers’ Clinical Supervision Framework 5 states that clinical supervision is a formal relationship involving oversight by a more experienced practitioner, aiming to develop skills, offer advice and advance patient care. The SCoR model of clinical supervision is based on formative, normative and restorative, which reflect the educational, supportive and professional monitoring roles of the clinical supervisor. 5 Staff providing clinical supervision at City, University of London and the University of the West of England support undergraduate students learning on placement by helping the learner link theory to practice, develop skills and giving appropriate feedback at regular intervals to support ongoing development. Supervisors have the responsibility to be open, honest and reflective in their approach with the willingness to nurture and develop the knowledge of the students within their department, tailoring their supervision to the stage of training and progress of the individual student in a calm, enthusiastic way. The role requires the supervisor to establish students’ prior knowledge at the same time as explaining underlying rationale, providing direction and with a willingness to provide a supportive and facilitative relationship.

While clinical supervisors of radiotherapy students are usually responsible for monitoring students’ progress in relation to learning outcomes, providing feedback to the student and educational institution, and completing clinical documentation, they may not always be responsible for providing pastoral support to students.Reference England, Geers-van Gemeren and Henner 6 Indeed, a study by Forte and FowlerReference Forte and Fowler 7 included a focus group comprising physiotherapy, occupational therapy and radiography staff, and participants acknowledged that ‘Radiographers find it quite difficult to engage in things which we call “touchy feely” subjects, like communication’ (p. 62).

In addition to issues relating directly to their clinical placement, students have also reported other reasons for leaving radiotherapy programmes, including finances, stress, lack of support, and mental health issues. 1 Therefore, while a main purpose of clinical supervisors is to support and facilitate the learning of others, 8 it would also be prudent for them to recognise individual’s needs and adapt supervisory practice accordingly. While several studies have examined the relationship between nursing students and clinical supervisors,Reference Lee, Cholowski and Williams 9 , Reference Sweet and Broadbent 10 less is known about radiotherapy students’ perceptions of their clinical supervision. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the experiences of radiotherapy students on clinical placement, with a particular focus on the extent to which well-being needs are acknowledged and supported.

Method

Forty-two second-year radiotherapy students were invited to take part in the study, and 25 participated: 17 (out of a possible 20) from City, University of London and eight (out of a possible 22) from University of the West of England (UWE), Bristol. Second-year students were selected as participants as they had completed a cycle of clinical placement, whereas first-year students had not yet been on placement, and third-year students were currently on placement. Students’ responses were collected anonymously so no further demographic information is available. Students were provided with a link to a Qualtrics survey, which they could complete within a dedicated study session, or at home in their own time.

The survey included a mixture of Likert scales and open-ended questions to explore the experiences of students on clinical placement. The questions were developed in a workshop session involving the lead researcher, radiography lecturers and a clinical supervisor.

Following advice from UWE’s research ethics committee, ethical approval was not sought for the study as it took place as a part of the regular module evaluations conducted for the programme. However, the following statement was included at the start of the survey ‘We may use this data for research purposes. If you are happy for your anonymous data to be used in this way, please check the box below’:

‘I consent to my anonymous data being used for research purposes’.

Results

Quantitative results

The survey involved four 4-point Likert scales asking students about their experiences of integrating into the radiotherapy team, and the awareness of staff about the students’ well-being needs.

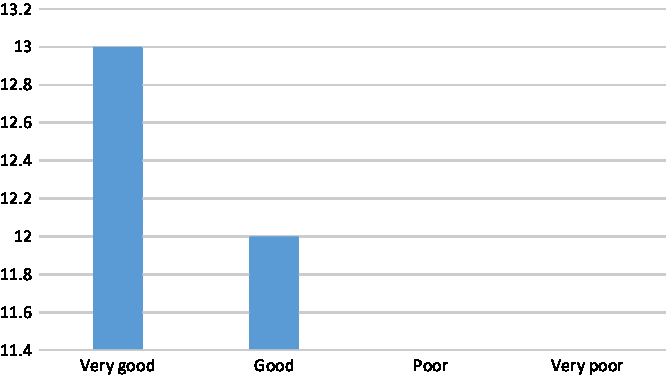

All of the students felt that the radiographers’ approach to making them feel part of the team was ‘very good’ or ‘good’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1. How would you rate the radiographers’ approach to making you feel part of the team throughout your whole placement?

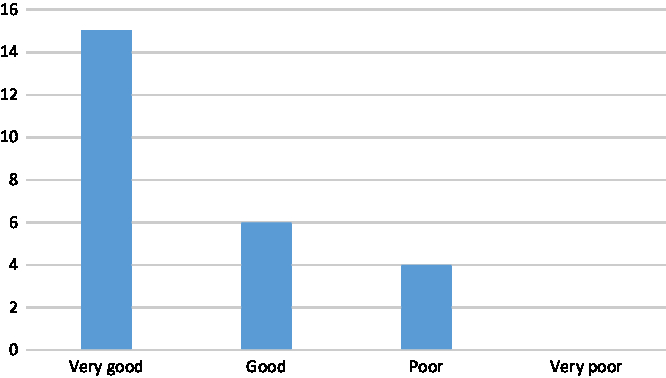

Sixty per cent of students felt that their clinical supervisors’ behaviour to promote a positive student experience was ‘very good’; however, 16% felt that clinical supervisors’ behaviour was ‘poor’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2. How do you rate your clinical supervisors’ behaviour to promote a positive student experience in the clinical department?

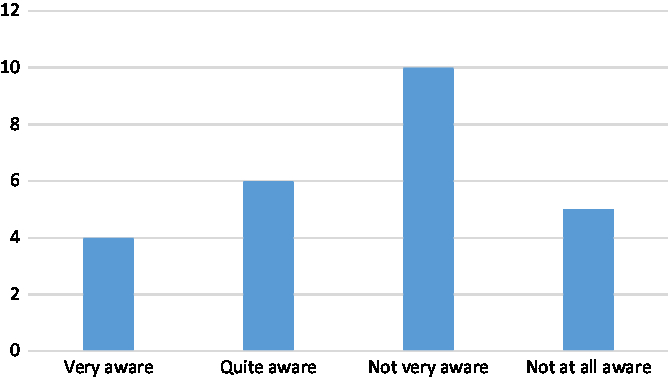

Sixty per cent of students did not feel that individual staff were very aware about how the pressures of life outside their control impacted on their studies (Figure 3).

Figure 3. How aware are individual staff about how the pressures of life outside your control impact upon your studies (e.g., finance, travel, health)?

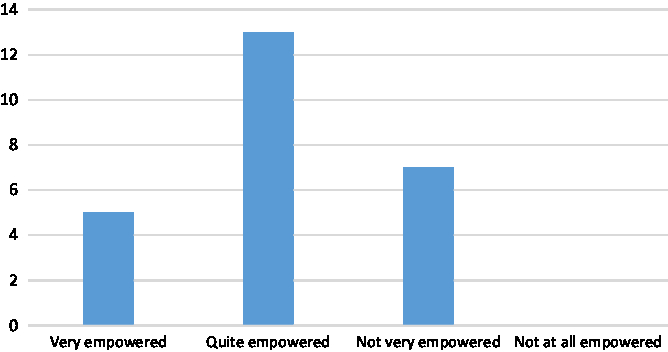

Fifty-two per cent students felt ‘quite empowered’ to inform staff about their well-being needs, while 20% felt ‘very empowered’ and 28% felt ‘not very empowered’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4. How empowered do you feel about informing staff of any well-being support needs you may require?

Qualitative results

The above quantitative data demonstrated a variation in the experiences of students relating to well-being needs and integration into the team. The qualitative, open-ended questions explored these topics in more detail. Responses from these questions were then subjected to a thematic analysis following the six-stage process outlined by Braun and Clarke.Reference Braun and Clarke 11

After a thorough familiarisation with the data, which began with transcription, reading and re-reading (phase 1), the researcher coded features of the data that were considered interesting in the context of the research question (phase 2). Once the list of codes and data extracts had been finalised, the researcher began searching for themes within the data (phase 3). The relationships between codes and potential themes were considered and three themes were generated: (1) information giving; (2) support from staff and (3) lack of support. These themes were then reviewed in relation to both the coded extracts and the data set as a whole (phase 4), and clear definitions and names were generated for each theme (phase 5). Once the themes were verified by another member of the research team (CB), the themes were written up to produce the final report (phase 6).

Provision of information and advice

Students felt that practical arrangements, such as a tour of the department, being provided with access codes, a badge and an overview of equipment made them feel welcome at the start of their placement. Students were introduced to staff in the department and were informed who they would be working with, which reportedly helped them to start feeling integrated into the team. Receiving advice and recommendations from radiotherapy staff was seen as instrumental to a positive placement experience. Several students mentioned an inclusive and informative teaching style, where staff would explain to the students what they were doing, providing examples of their own experiences of a patient or disease to help students relate to the role.

I felt that the members of radiographers would make a concerted effort to involve me as much as possible without patronising me, which removed any awkward student-teacher type scenarios. Instead they would recommend things I could change or improve on much in the way they would with one another, instead of lecturing me.

However, some of the students felt like they needed additional information and signposting. This could relate to additional information about the department itself, the roles and responsibilities expected of the students, or guidance around clinic documentation. A number of students also reported that they needed more information about well-being and support, whether this involved maintaining good health and well-being in the department or knowing where to find counselling or financial advice services. In some cases, it was felt that staff were unaware of academic commitments outside of the placement and would benefit from more information about the pressures faced by students.

I did not know what to do and what to expect. It was not clear structure what has been expected from me (sic). I was very confused.

They would ask me what social activities I was going to do after work and I had to tell them that I didn’t have time to do any social activities because I had to do my logs and other uni work. They weren’t very aware that I had a lot to do outside of placement.

An open, inclusive and supportive working environment

An open, inclusive and supportive working environment was another factor that greatly contributed to fostering a positive placement experience for students. Despite the fact that a number of students initially found it difficult to integrate into the team, this often improved with time.

Several students also talked about the importance of being acknowledged and included by other members of the team. Radiotherapy staff introduced students in team meetings and tea rounds, and encouraged them to participate in discussions. Students also referred to the encouragement and reassurance that they received from some of the radiographers, who provided them with the opportunity to observe and ask questions. A number of students appreciated the chance to get involved in clinical tasks, as they were encouraged to take the lead wherever feasible.

They offered lots of support, advice and let the students take a lot of the lead. This made me feel like a real team member as I was involved in every aspect of the job.

As someone who doesn’t really like to ask questions it was very reassuring to be told that no question is a stupid question and that I should hit them with any queries I may have. This allowed me to feel included in discussions among the team.

The personal and professional demeanour of clinical staff was discussed by a large number of the students, and this appeared to be an important contributor to the student experience. For example, many students felt that staff considered their needs and provided them with flexibility when required, although in some cases even more flexibility would have been appreciated, particularly when well-being needs arose.

They tried to give us more time to get logs done during placement which I found very helpful especially at times where I was not able to do anything (peak times). I felt myself just standing around with no explanation of what was happening. It was much more useful to spend my time doing my logs to help ease the stress of having to do it later.

If we get sick we must be able to attend all our medical appointment and be able to make up hours when possible.

Many of the radiographers were seen as making time, or going the extra mile, for students. Sometimes this involved staff taking the time to guide students through clinical tasks, but it most often related to well-being and support. Many of the students referred to a variety of staff, including clinical supervisors, personal tutors or simply other members of the department, making time to provide pastoral care and support.

I don’t think I could have possibly had a better clinical supervisor… Each appointment was as long we needed it to be and they never felt rushed.

A lack of communication, understanding, and consistency

Although a large number of students reported positive experiences from their clinical placements, a lack of communication, understanding and consistency had a detrimental effect for others. Several students did not feel as though they were made to feel like part of the team. However, there was found to be a large variation between different members of staff. While most members of staff were found to be friendly and helpful by students, others were viewed less positively. Some students also felt that high expectations and a lack of communication from staff had a negative effect on their placement.

Initially I felt like a bit of an outsider but once people started explaining things to me and including me in their conversations, I started to feel more apart (sic) of the team. This was until someone told me that I was here to lean (sic) and not be friends with the team and to stop engaging them in any conversation that wasn’t Radiotherapy related.

I did not see my initial supervisor for several weeks at a time and there was no real communication at all. I had others supervisors who I was able to ask for help instead.

In addition to academic and mental health issues, students also referred to other well-being issues such as physical health and financial concerns. Some felt that there was no support available from the clinical team and that they were expected to solve their own problems.

I became very tired towards the middle and then right at the end of placement. I found it very hard to keep going and doing my logs at the same time. I would recommend that we have a week break in the middle of the 14 weeks to regain our mental strength since by week 12 I was so tired and prone to being sad due to exhaustion.

Furthermore, students did not always feel comfortable raising well-being issues with radiotherapy staff, particularly with members of staff who were responsible for their academic assessment.

It’s hard to do as may impact their opinion of you as a student radiographer.

It was suggested that having an allocated time and/or person with whom to discuss well-being needs could be beneficial, particularly if this person was seen as being impartial to the students’ academic assessments. Around one-third of respondents sought well-being support while on placement, primarily from their clinical supervisor or from senior staff in the team.

Maybe they should take it upon them to give slight more attention to this one student. This way we have that one person to go to when in need and do not need to feel hesitant about approaching anybody else.

Discussion

Students reported a great deal of variation within their clinical radiotherapy placements, which appears to relate, at least to some extent, to the different experiences they have had with members of staff. While on the whole students rated the radiographers’ approach to making them feel part of the team as ‘very good’ or ‘good’, some discrepancies emerged within the qualitative data to suggest that certain members of staff had been less welcoming and inclusive than others. Information provision and advice helped the students to feel better integrated into the team; however, there was a sense that more information from staff would be appreciated. Furthermore, it was not always clear if staff fully understood students’ academic commitments, indicating that staff may also benefit from additional information about the nature of radiotherapy programmes.

Many students found that they were included and supported by the radiotherapy team, and specifically mentioned the opportunity to observe, ask questions and get involved in clinical duties as beneficial to their learning experience. They appreciated the reassurance and encouragement that they received from a number of staff, especially those who they felt went above and beyond to foster a positive and supportive placement experience. This is in keeping with previous research which has indicated that positive clinical placement experiences for students often depend on the extent to which they feel valued and supported.Reference Hartigan-Rogers, Cobbett, Amirault and Muise-Davis 12

However, there was also a sense that staff were not always aware of students’ well-being needs, admittedly sometimes due to the omission of this information by the students themselves. Students did not always feel that they could raise these concerns within the radiotherapy team, worrying about the impact this could have on their placement. Several students felt that staff were not sufficiently able to signpost students to appropriate support services, and it is unclear whether the clinical supervisors in this study had received any specific well-being training prior to assuming their roles. The College of Radiographers’ Framework suggests that training and supervision for supervisors are essential for clinical supervision to succeed, 5 and further research could examine this in more detail. For example, an exploratory study of clinical supervisors’ experiences could understand how much support was provided to prepare them for the role, and determine whether supervisors have any specific training needs.

Some students also reported that a small number of staff had a negative impact on their placement, due to their workplace conduct. The behaviour of these staff as reported by students may be considered workplace incivility, which is defined as ‘low intensity deviant behaviour with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect’ (p. 457), such as excluding colleagues from social events, making derogatory or dismissive comments, or dismissing other people’s ideas.Reference Andersson and Pearson 13 Reported behaviours in this study included staff ‘talking down’ to students, instructing them not to socialise with other members of the team and that they may only engage in conversation related to the workplace and gossiping about other radiographers.

Workplace incivility within clinical practice has been linked with a number of undesirable outcomes, including poor mental health,Reference Laschinger, Wong, Regan, Young-Ritchie and Bushell 14 burnout,Reference Babenko-Mould and Laschinger 15 loss of self-esteemReference Kang, Jeong and Kong 16 and disengagement with learning.Reference Vuolo 17 Furthermore, it may have a detrimental outcome on patient outcomes.Reference Hutchinson and Jackson 18 It is not known whether these specific outcomes were experienced by the participants in this study and further research could explore the consequences of negative behaviours in more detail. However, the reported consequences in previous research indicates that reducing incivility behaviours could be of great benefit to radiotherapy departments. Nursing research has indicated that an educational intervention has raised awareness of incivility in the clinical environment.Reference Teresa Nikstaitis and Simko 19 Further research could therefore explore clinical supervisors’ perceptions of their professional conduct and determine whether an educational intervention could help to improve behaviour.

While this study provided an overview of various issues experienced by students on clinical placement, it is not without its limitations. The responses from the Likert scales may be hard to generalise due to the way in which the categories were interpreted by participants. For example, ‘very good’ and ‘good’ may represent different things to each individual and it is not clear on what criteria the participants were basing these ratings. Furthermore, although the survey included open-ended questions, it is not known whether participants fully reported their experiences using this format, which also did not allow for any follow-up questions to participants’ responses. Future research involving qualitative interviews or focus groups may therefore provide a more comprehensive account of students’ clinical placement experiences.

Conclusion

The overarching finding from this study is the disparity between the experiences of students on clinical placement, most specifically to their encounters with different members of staff. The provision of information and advice was seen by students as essential to helping them settle in their placements. While an open, inclusive and supportive working environment fostered a positive clinical placement for some students, a lack of communication, understanding, and consistency had a detrimental impact for others. Therefore, improving support and communication from clinical supervisors could help to improve clinical placements for students, and ensure a more consistent experience across placement sites. It is suggested that training sessions tailored towards supporting students on placement could help clinical supervisors to become more aware of their workplace conduct, and the effect this may have on students. Furthermore, such training could help raise clinical supervisors’ awareness of the well-being issues students may face within their placements, providing them with information on how to address any concerns and where to signpost for additional support. It is suggested that further research is needed, to explore clinical supervisors’ experience of supporting students on placement, to determine whether specific well-being training would be of benefit and the format that this should take.

Author ORCIDs

Laura Armstrong-James, 0000-0002-3887-9466

Acknowledgements

None

Financial support

This study was supported by the Strategic Interventions in Health Education Disciplines (SIHED) Challenge Fund (Project Code: 600).

Conflicts of interest

None

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Appendix 1 – student evaluation questionnaire

The Radiotherapy department – your general sense of belonging

(1) How are you made to feel part of the team/department when you arrive at your placement site? (please give examples)

(2) How would you rate the radiographers’ approach to making you feel part of the team throughout your whole placement?

Very good/Good/Poor/Very poor

Please provide details (optional)

(3) How do you rate your clinical supervisors’ behavior to promote a positive student experience in the clinical department?

Very good/Good/Poor/Very poor

Please provide details (optional)

Individual support and well-being/empowerment

(1) How aware are individual staff about how the pressures of life outside your control impact upon your studies (e.g., finance, travel, health)?

Very aware/Quite aware/Not very aware/Not at all aware

Please provide details (optional)

(2) How do clinical supervisors support you to manage any well-being needs you may have?

(3) How empowered do you feel about informing staff of any well-being support needs you may require?

Very empowered/Quite empowered/Not very empowered/Not at all empowered

Please provide details (optional)

(4) If you ask for well-being help on placement how do your clinical supervisors help you?

(5) Where/who did you go to for well-being support whilst on placement?

(6) What well-being support would you like to receive to ensure that your placement runs smoothly (either before placement or during placement)?

(7) What guidance do you feel clinical supervisors need to help facilitate you to manage your health and well-being in placement? (please give examples)

(8) Is there anything else you would like to tell us?